User login

New-onset hirsutism

A 74-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for follow-up 3 months after the surgical excision of a basal cell carcinoma on her left jawline. During this postop period, the patient developed new-onset hirsutism. She appeared to be in otherwise good health.

Family and personal medical history were unremarkable. Her medication regimen included aspirin 81 mg/d and a daily multivitamin. The patient was postmenopausal and had a body mass index of 28 and a history of acid reflux and osteoarthritis.

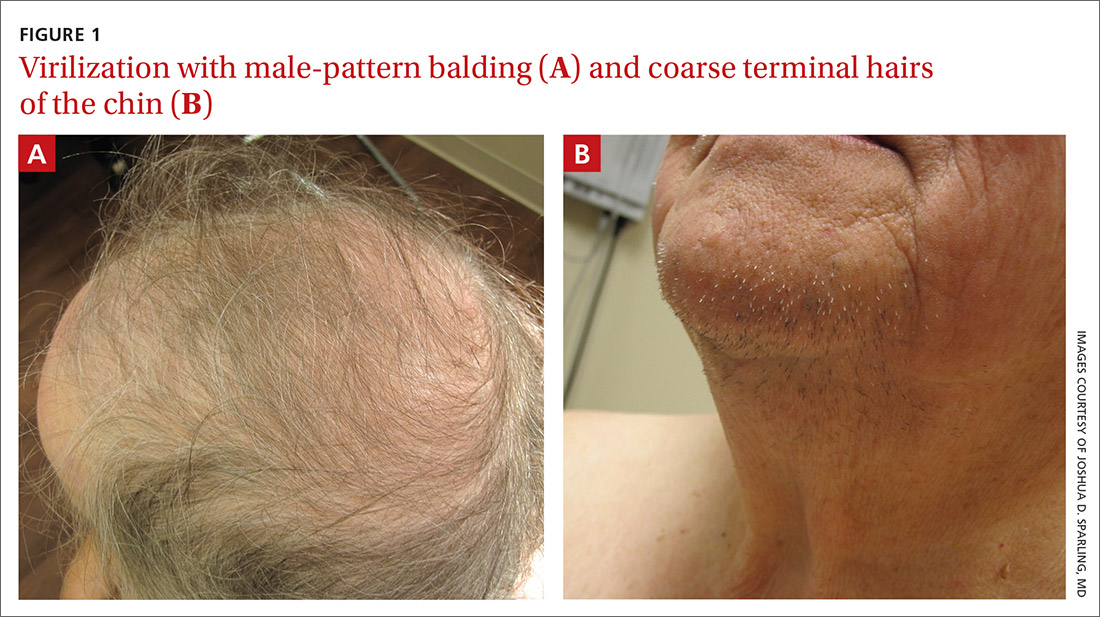

Physical examination of the patient’s scalp showed male-pattern alopecia (FIGURE 1A). She also had coarse terminal hairs on her forearms and back, as well as on her chin (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Androgen-secreting ovarian tumor

Based on the distribution of terminal hairs and marked change over 3 months, as well as the male-pattern alopecia, a diagnosis of androgen excess was suspected. Laboratory work-up, including thyroid-stimulating hormone, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, prolactin, complete blood count, and complete metabolic panel, was within normal limits. Pelvic ultrasound of the ovaries and abdominal computed tomography (CT) of the adrenal glands were also normal.

Further testing showed an elevated testosterone level of 464 ng/dL (reference range: 2-45 ng/dL) and an elevated free testosterone level of 66.8 ng/dL (reference range: 0.2-3.7 ng/dL). These levels pointed to an androgen-secreting ovarian tumor; the androgen excess was likely the cause of her hirsutism.

Hirsutism or hypertrichosis?

Hirsutism, a common disorder affecting up to 8% of women, is defined by excess terminal hairs that appear in a male pattern in women due to production of excess androgens.1 This should be distinguished from hypertrichosis, which is generalized excessive hair growth not caused by androgen excess.

Testosterone and DHEAS—produced in the ovaries and adrenal glands, respectively—contribute to the development of hirsutism.1 Hirsutism is more often associated with adrenal or ovarian tumors in postmenopausal patients.2 Generalized hypertrichosis can be associated with porphyria cutanea tarda, severe anorexia nervosa, and rarely, malignancies; it also can be secondary to certain agents, such as cyclosporin, phenytoin, and minoxidil.

While hirsutism is associated with hyperandrogenemia, its degree correlates poorly with serum levels. Notably, about half of women with hirsutism have been found to have normal levels of circulating androgens.1 Severe signs of hyperandrogenemia include rapid onset of symptoms, signs of virilization, and a palpable abdominal or pelvic mass.3

Continue to: Is the patient pre- or postmenopausal?

Is the patient pre- or postmenopausal? Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) accounts for up to three-fourths of premenopausal hirsutism.3 The likelihood of hirsutism is actually decreased in postmenopausal women because estrogen levels can drop abruptly after menopause. That said, conditions linked to hirsutism in postmenopausal women include adrenal hyperplasia, thyroid dysfunction, Cushing syndrome, and least frequently, androgen-secreting tumors (seen in this patient). (Hirsutism can also be idiopathic or iatrogenic [medications].)

Methods for detection

Research suggests that when a female patient is given a diagnosis of hirsutism, it’s important to explore possible underlying ovarian and/or adrenal tumors and adult-onset adrenal hyperplasia.1 The following tests and procedure can be helpful:

Serum testosterone and DHEAS. Levels of total testosterone > 200 ng/dL and/or DHEAS > 700 ng/dL are strongly indicative of androgen-secreting tumors.1

Imaging—including ultrasound, CT, or magnetic resonance imaging—can be used for evaluation of the adrenal glands and ovaries. However, imaging is often unable to identify these small tumors.4

Selective venous catheterization can be useful in the localization and lateralization of an androgen-secreting tumor, although a nondiagnostic result with this technique is not uncommon.4

Continue to: Dynamic hormonal testing

Dynamic hormonal testing may assist in determining the pathology of disease but not laterality.2 For example, testing for gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists can be helpful because the constant administration of such agonists can lead to ovarian suppression without affecting adrenal androgen secretion.5

Testing with oral dexamethasone may induce adrenal hormonal depression of androgens and subsequent estradiol through aromatase conversion, which can help rule out an ovarian source.6 Exogenous administration of follicle-stimulating hormone or luteinizing hormone can further differentiate the source from ovarian theca or granulosa cell production.4

Treatment varies

The specific etiology of a patient’s hirsutism dictates the most appropriate treatment. For example, medication-induced hirsutism often requires discontinuation of the offending agent, whereas PCOS would necessitate appropriate nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions.

For our patient, the elevated testosterone and free testosterone levels with normal DHEAS strongly suggested the presence of an androgen-secreting ovarian tumor. These findings led to a referral for bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The surgical gross appearance of the patient’s ovaries was unremarkable, but gross dissection and pathology of the ovaries (which were not postoperatively identified to determine laterality) showed one was larger (2.7 × 1.5 × 0.8 cm vs 3.2 × 1.4 × 1.2 cm).

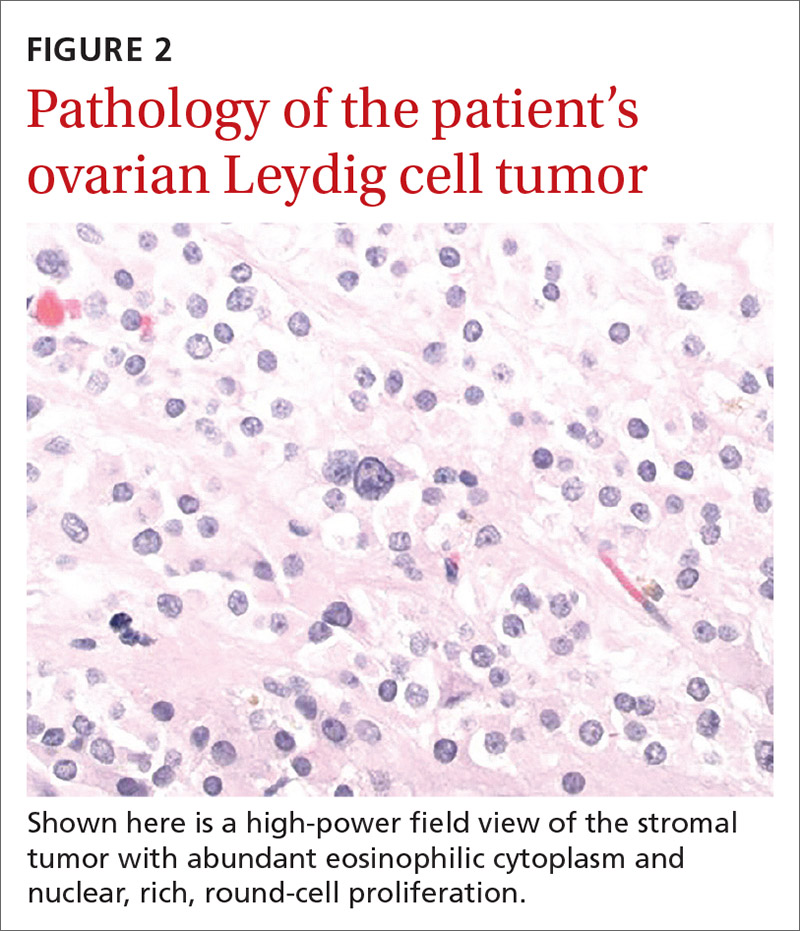

The larger ovary contained an area of brown induration measuring 2.3 × 1.1 × 1.1 cm. This area corresponded to abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with nuclear, rich, round-cell proliferation, consistent with the diagnosis of a benign ovarian Leydig cell tumor (FIGURE 2). Thus, the bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was both diagnostic and therapeutic.

Six weeks after the surgery, blood work showed normalization of testosterone and free testosterone levels. The patient’s hirsutism completely resolved over the course of the next several months.

1. Hunter M, Carek PJ. Evaluation and treatment of women with hirsutism. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:2565-2572.

2. Alpañés M, González-Casbas JM, Sánchez J, et al. Management of postmenopausal virilization. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2584-2588.

3. Bode D, Seehusen DA, Baird D. Hirsutism in women. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:373-380.

4. Cohen I, Nabriski D, Fishman A. Noninvasive test for the diagnosis of ovarian hormone-secreting-neopolasm in postmenopausal women. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2016;15:12-15.

5. Gandrapu B, Sundar P, Phillips B. Hyperandrogenism in a postmenaupsal woman secondary to testosterone secreting ovarian stromal tumor with acoustic schwannoma. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2018;2018:8154513.

6. Curran DR, Moore C, Huber T. What is the best approach to the evaluation of hirsutism? J Fam Pract. 2005;54:458-473.

A 74-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for follow-up 3 months after the surgical excision of a basal cell carcinoma on her left jawline. During this postop period, the patient developed new-onset hirsutism. She appeared to be in otherwise good health.

Family and personal medical history were unremarkable. Her medication regimen included aspirin 81 mg/d and a daily multivitamin. The patient was postmenopausal and had a body mass index of 28 and a history of acid reflux and osteoarthritis.

Physical examination of the patient’s scalp showed male-pattern alopecia (FIGURE 1A). She also had coarse terminal hairs on her forearms and back, as well as on her chin (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Androgen-secreting ovarian tumor

Based on the distribution of terminal hairs and marked change over 3 months, as well as the male-pattern alopecia, a diagnosis of androgen excess was suspected. Laboratory work-up, including thyroid-stimulating hormone, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, prolactin, complete blood count, and complete metabolic panel, was within normal limits. Pelvic ultrasound of the ovaries and abdominal computed tomography (CT) of the adrenal glands were also normal.

Further testing showed an elevated testosterone level of 464 ng/dL (reference range: 2-45 ng/dL) and an elevated free testosterone level of 66.8 ng/dL (reference range: 0.2-3.7 ng/dL). These levels pointed to an androgen-secreting ovarian tumor; the androgen excess was likely the cause of her hirsutism.

Hirsutism or hypertrichosis?

Hirsutism, a common disorder affecting up to 8% of women, is defined by excess terminal hairs that appear in a male pattern in women due to production of excess androgens.1 This should be distinguished from hypertrichosis, which is generalized excessive hair growth not caused by androgen excess.

Testosterone and DHEAS—produced in the ovaries and adrenal glands, respectively—contribute to the development of hirsutism.1 Hirsutism is more often associated with adrenal or ovarian tumors in postmenopausal patients.2 Generalized hypertrichosis can be associated with porphyria cutanea tarda, severe anorexia nervosa, and rarely, malignancies; it also can be secondary to certain agents, such as cyclosporin, phenytoin, and minoxidil.

While hirsutism is associated with hyperandrogenemia, its degree correlates poorly with serum levels. Notably, about half of women with hirsutism have been found to have normal levels of circulating androgens.1 Severe signs of hyperandrogenemia include rapid onset of symptoms, signs of virilization, and a palpable abdominal or pelvic mass.3

Continue to: Is the patient pre- or postmenopausal?

Is the patient pre- or postmenopausal? Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) accounts for up to three-fourths of premenopausal hirsutism.3 The likelihood of hirsutism is actually decreased in postmenopausal women because estrogen levels can drop abruptly after menopause. That said, conditions linked to hirsutism in postmenopausal women include adrenal hyperplasia, thyroid dysfunction, Cushing syndrome, and least frequently, androgen-secreting tumors (seen in this patient). (Hirsutism can also be idiopathic or iatrogenic [medications].)

Methods for detection

Research suggests that when a female patient is given a diagnosis of hirsutism, it’s important to explore possible underlying ovarian and/or adrenal tumors and adult-onset adrenal hyperplasia.1 The following tests and procedure can be helpful:

Serum testosterone and DHEAS. Levels of total testosterone > 200 ng/dL and/or DHEAS > 700 ng/dL are strongly indicative of androgen-secreting tumors.1

Imaging—including ultrasound, CT, or magnetic resonance imaging—can be used for evaluation of the adrenal glands and ovaries. However, imaging is often unable to identify these small tumors.4

Selective venous catheterization can be useful in the localization and lateralization of an androgen-secreting tumor, although a nondiagnostic result with this technique is not uncommon.4

Continue to: Dynamic hormonal testing

Dynamic hormonal testing may assist in determining the pathology of disease but not laterality.2 For example, testing for gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists can be helpful because the constant administration of such agonists can lead to ovarian suppression without affecting adrenal androgen secretion.5

Testing with oral dexamethasone may induce adrenal hormonal depression of androgens and subsequent estradiol through aromatase conversion, which can help rule out an ovarian source.6 Exogenous administration of follicle-stimulating hormone or luteinizing hormone can further differentiate the source from ovarian theca or granulosa cell production.4

Treatment varies

The specific etiology of a patient’s hirsutism dictates the most appropriate treatment. For example, medication-induced hirsutism often requires discontinuation of the offending agent, whereas PCOS would necessitate appropriate nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions.

For our patient, the elevated testosterone and free testosterone levels with normal DHEAS strongly suggested the presence of an androgen-secreting ovarian tumor. These findings led to a referral for bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The surgical gross appearance of the patient’s ovaries was unremarkable, but gross dissection and pathology of the ovaries (which were not postoperatively identified to determine laterality) showed one was larger (2.7 × 1.5 × 0.8 cm vs 3.2 × 1.4 × 1.2 cm).

The larger ovary contained an area of brown induration measuring 2.3 × 1.1 × 1.1 cm. This area corresponded to abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with nuclear, rich, round-cell proliferation, consistent with the diagnosis of a benign ovarian Leydig cell tumor (FIGURE 2). Thus, the bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was both diagnostic and therapeutic.

Six weeks after the surgery, blood work showed normalization of testosterone and free testosterone levels. The patient’s hirsutism completely resolved over the course of the next several months.

A 74-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for follow-up 3 months after the surgical excision of a basal cell carcinoma on her left jawline. During this postop period, the patient developed new-onset hirsutism. She appeared to be in otherwise good health.

Family and personal medical history were unremarkable. Her medication regimen included aspirin 81 mg/d and a daily multivitamin. The patient was postmenopausal and had a body mass index of 28 and a history of acid reflux and osteoarthritis.

Physical examination of the patient’s scalp showed male-pattern alopecia (FIGURE 1A). She also had coarse terminal hairs on her forearms and back, as well as on her chin (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Androgen-secreting ovarian tumor

Based on the distribution of terminal hairs and marked change over 3 months, as well as the male-pattern alopecia, a diagnosis of androgen excess was suspected. Laboratory work-up, including thyroid-stimulating hormone, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, prolactin, complete blood count, and complete metabolic panel, was within normal limits. Pelvic ultrasound of the ovaries and abdominal computed tomography (CT) of the adrenal glands were also normal.

Further testing showed an elevated testosterone level of 464 ng/dL (reference range: 2-45 ng/dL) and an elevated free testosterone level of 66.8 ng/dL (reference range: 0.2-3.7 ng/dL). These levels pointed to an androgen-secreting ovarian tumor; the androgen excess was likely the cause of her hirsutism.

Hirsutism or hypertrichosis?

Hirsutism, a common disorder affecting up to 8% of women, is defined by excess terminal hairs that appear in a male pattern in women due to production of excess androgens.1 This should be distinguished from hypertrichosis, which is generalized excessive hair growth not caused by androgen excess.

Testosterone and DHEAS—produced in the ovaries and adrenal glands, respectively—contribute to the development of hirsutism.1 Hirsutism is more often associated with adrenal or ovarian tumors in postmenopausal patients.2 Generalized hypertrichosis can be associated with porphyria cutanea tarda, severe anorexia nervosa, and rarely, malignancies; it also can be secondary to certain agents, such as cyclosporin, phenytoin, and minoxidil.

While hirsutism is associated with hyperandrogenemia, its degree correlates poorly with serum levels. Notably, about half of women with hirsutism have been found to have normal levels of circulating androgens.1 Severe signs of hyperandrogenemia include rapid onset of symptoms, signs of virilization, and a palpable abdominal or pelvic mass.3

Continue to: Is the patient pre- or postmenopausal?

Is the patient pre- or postmenopausal? Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) accounts for up to three-fourths of premenopausal hirsutism.3 The likelihood of hirsutism is actually decreased in postmenopausal women because estrogen levels can drop abruptly after menopause. That said, conditions linked to hirsutism in postmenopausal women include adrenal hyperplasia, thyroid dysfunction, Cushing syndrome, and least frequently, androgen-secreting tumors (seen in this patient). (Hirsutism can also be idiopathic or iatrogenic [medications].)

Methods for detection

Research suggests that when a female patient is given a diagnosis of hirsutism, it’s important to explore possible underlying ovarian and/or adrenal tumors and adult-onset adrenal hyperplasia.1 The following tests and procedure can be helpful:

Serum testosterone and DHEAS. Levels of total testosterone > 200 ng/dL and/or DHEAS > 700 ng/dL are strongly indicative of androgen-secreting tumors.1

Imaging—including ultrasound, CT, or magnetic resonance imaging—can be used for evaluation of the adrenal glands and ovaries. However, imaging is often unable to identify these small tumors.4

Selective venous catheterization can be useful in the localization and lateralization of an androgen-secreting tumor, although a nondiagnostic result with this technique is not uncommon.4

Continue to: Dynamic hormonal testing

Dynamic hormonal testing may assist in determining the pathology of disease but not laterality.2 For example, testing for gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists can be helpful because the constant administration of such agonists can lead to ovarian suppression without affecting adrenal androgen secretion.5

Testing with oral dexamethasone may induce adrenal hormonal depression of androgens and subsequent estradiol through aromatase conversion, which can help rule out an ovarian source.6 Exogenous administration of follicle-stimulating hormone or luteinizing hormone can further differentiate the source from ovarian theca or granulosa cell production.4

Treatment varies

The specific etiology of a patient’s hirsutism dictates the most appropriate treatment. For example, medication-induced hirsutism often requires discontinuation of the offending agent, whereas PCOS would necessitate appropriate nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions.

For our patient, the elevated testosterone and free testosterone levels with normal DHEAS strongly suggested the presence of an androgen-secreting ovarian tumor. These findings led to a referral for bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The surgical gross appearance of the patient’s ovaries was unremarkable, but gross dissection and pathology of the ovaries (which were not postoperatively identified to determine laterality) showed one was larger (2.7 × 1.5 × 0.8 cm vs 3.2 × 1.4 × 1.2 cm).

The larger ovary contained an area of brown induration measuring 2.3 × 1.1 × 1.1 cm. This area corresponded to abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with nuclear, rich, round-cell proliferation, consistent with the diagnosis of a benign ovarian Leydig cell tumor (FIGURE 2). Thus, the bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was both diagnostic and therapeutic.

Six weeks after the surgery, blood work showed normalization of testosterone and free testosterone levels. The patient’s hirsutism completely resolved over the course of the next several months.

1. Hunter M, Carek PJ. Evaluation and treatment of women with hirsutism. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:2565-2572.

2. Alpañés M, González-Casbas JM, Sánchez J, et al. Management of postmenopausal virilization. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2584-2588.

3. Bode D, Seehusen DA, Baird D. Hirsutism in women. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:373-380.

4. Cohen I, Nabriski D, Fishman A. Noninvasive test for the diagnosis of ovarian hormone-secreting-neopolasm in postmenopausal women. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2016;15:12-15.

5. Gandrapu B, Sundar P, Phillips B. Hyperandrogenism in a postmenaupsal woman secondary to testosterone secreting ovarian stromal tumor with acoustic schwannoma. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2018;2018:8154513.

6. Curran DR, Moore C, Huber T. What is the best approach to the evaluation of hirsutism? J Fam Pract. 2005;54:458-473.

1. Hunter M, Carek PJ. Evaluation and treatment of women with hirsutism. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:2565-2572.

2. Alpañés M, González-Casbas JM, Sánchez J, et al. Management of postmenopausal virilization. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2584-2588.

3. Bode D, Seehusen DA, Baird D. Hirsutism in women. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:373-380.

4. Cohen I, Nabriski D, Fishman A. Noninvasive test for the diagnosis of ovarian hormone-secreting-neopolasm in postmenopausal women. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2016;15:12-15.

5. Gandrapu B, Sundar P, Phillips B. Hyperandrogenism in a postmenaupsal woman secondary to testosterone secreting ovarian stromal tumor with acoustic schwannoma. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2018;2018:8154513.

6. Curran DR, Moore C, Huber T. What is the best approach to the evaluation of hirsutism? J Fam Pract. 2005;54:458-473.

Multiple hyperpigmented papules and plaques

A 2-year-old girl with Fitzpatrick skin type VI who had recently emigrated from Djibouti presented to our dermatology clinic for a rash that appeared when she was 2 months old. The lesions occasionally were pruritic after sun exposure or after crawling outside. There was no associated abdominal pain, diarrhea, flushing, or hypotension. Topical moisturizers were not helpful.

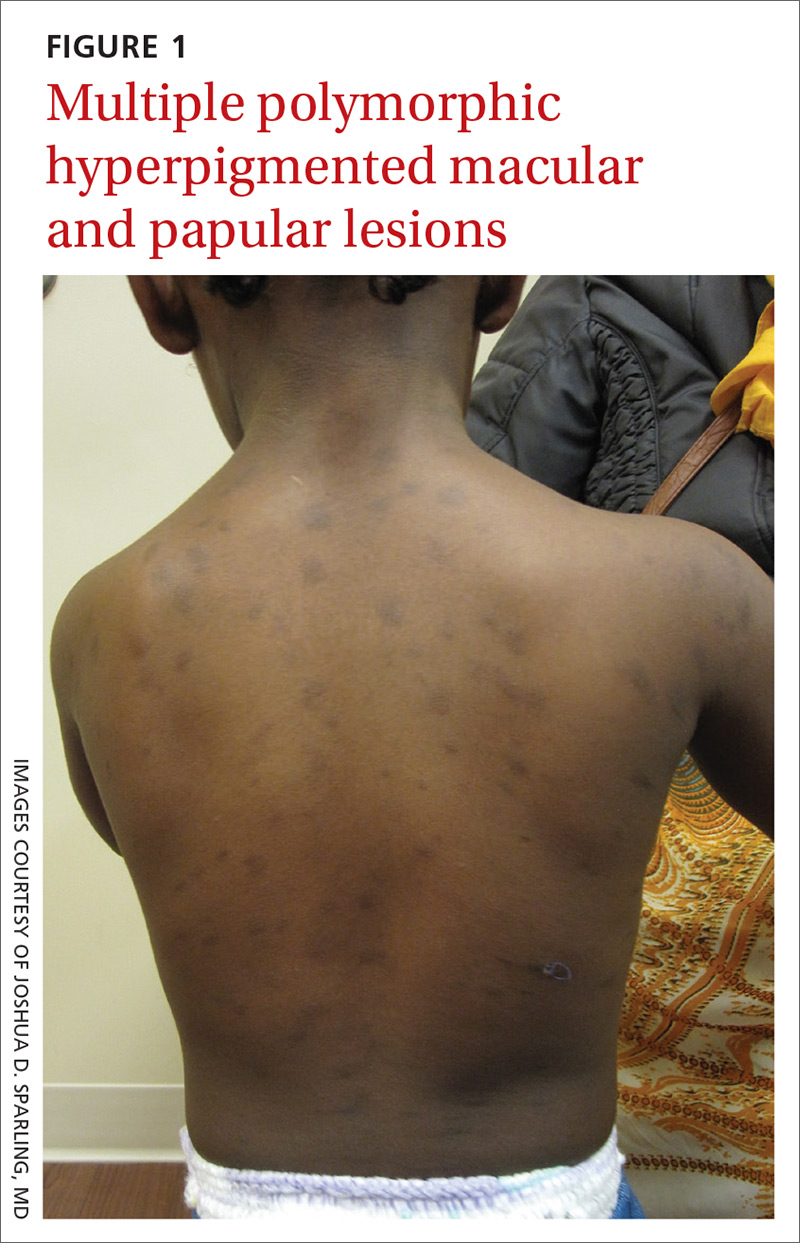

The patient had no known allergies or other notable medical history. Physical examination revealed multiple hyperpigmented, oval-shaped, slightly raised papules and plaques on her torso (FIGURE 1), neck, and arms, and fewer lesions on her face and legs. Darier sign was not appreciated on the initial consult. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the patient’s right middle back was performed at this visit.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Mastocytosis

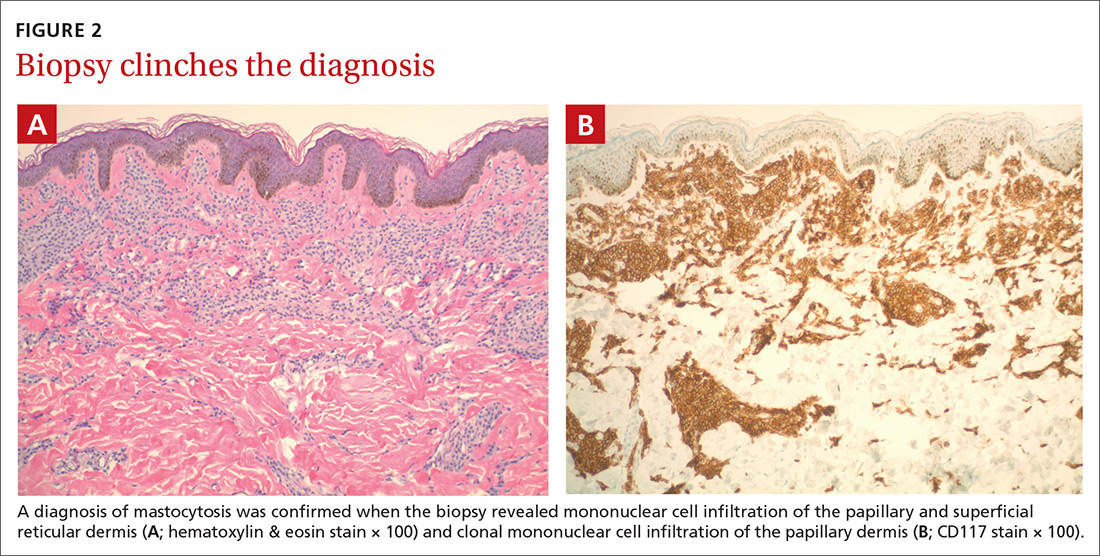

The presence of a hyperpigmented skin lesion that becomes pruritic, raised, and erythematous when rubbed (Darier sign) is the major criterion for the diagnosis of cutaneous mastocytosis.1 Minor criteria include a skin biopsy demonstrating a 4- to 8-fold increase in the number of mast cells within the papillary dermis and the presence of cKIT mutations.1 In this case, the patient’s punch biopsy results came back positive for clonal mast cell infiltration of the papillary dermis (FIGURES 2A and 2B), and her physician elicited a slightly positive Darier sign during a follow-up visit.

Mastocytosis is characterized by pathognomonic proliferation of clonal mast cells with either cutaneous or systemic involvement.1 Mast cell expansion most commonly is found in the skin and bone marrow; however, involvement of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes also has been documented.1 Nonhereditary somatic mutations of the cKIT gene have been observed in many studies and may be associated with increased proliferation of clonal mast cells.2

A review of the English-language literature on cutaneous mastocytosis reveals a paucity of reports in darker skin types. However, it is important for clinicians to be able to recognize this disease in all skin types.

Three subcategories. Cutaneous mastocytosis is divided into 3 subcategories: mastocytoma of the skin (1–3 solitary skin lesions), maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, also known as urticaria pigmentosa (as seen in our patient; usually ≥ 4 lesions); and diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis (confluent lesions; leathery appearance of skin).1,3,4 Maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, which our patient had, classically develops within the first 6 months of life and presents as hyperpigmented macules and papules.

Keep in mind that systemic involvement in cutaneous mastocytosis occasionally occurs and can be associated with anaphylaxis, flushing, headache, dyspnea, nausea, emesis, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and hepatosplenomegaly.2

Continue to: Narrowing down a broad differential diagnosis

Narrowing down a broad differential diagnosis

Our cas a ase was made somewhat challenging by the patient’s darkly pigmented skin color, which made any erythema and other cutaneous signs less visible. The differential was broad and included postinflammatory hyperpigmentation from eczema, multiple congenital nevi, sarcoidosis, leprosy, and cutaneous tuberculosis, all of which can be eliminated by performing a biopsy of the lesion.

Diagnostic criteria include biopsy and laboratory findings

In addition to a skin biopsy, initial assessment in cases of suspected cutaneous mastocytosis should include a complete blood cell count with differential, liver function tests (+/- liver ultrasound), a serum tryptase level, and a peripheral smear. Serum tryptase levels > 20 ng/mL have been shown to correlate with a higher probability of systemic mastocytosis. Higher tryptase levels also correlate with severity of disease in children.5

Treatment focuses on minimizing mast cell degranulation

Due to the relatively benign course of cutaneous mastocytosis, the mainstay of treatment is focused on minimizing mast cell degranulation to control subsequent symptoms. Avoiding precipitating factors such as temperature extremes, external stimulation of lesions, dry skin, infection, and certain medications (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, morphine, polymyxin B sulphate, anticholinergics, some systemic anesthetics) that can stimulate mast cell degranulation is encouraged.2 H1 and H2 antihistamines are the first-line treatment for mild to moderate symptoms. In refractory cases, leukotriene receptor antagonists or oral cromolyn sodium may be considered.2

Regular follow-up every 6 to 12 months should be established after diagnosis.1 If symptoms persist into adulthood or concern for disease progression is high, a bone marrow biopsy is recommended.1

Our patient

Our patient’s laboratory results revealed a normal serum tryptase level (3.4 ng/mL; reference range < 11.5 ng/mL) and complete blood cell count. A complete metabolic panel demonstrated elevated and high-normal liver function tests with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 111 u/L (reference range, 10–40 u/L) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 55 u/L (reference range, 7–56 u/L).

Continue to: As a precaution...

As a precaution and for consideration of further work-up, such as the need for a liver ultrasound, the patient was referred to Pediatric Gastroenterology. The specialist repeated the liver function tests, the results of which were lower (ALT, 42 u/L; AST, 24 u/L); a liver ultrasound was thought to be unnecessary.

Our patient’s otherwise negative review of systems led the specialist to feel confident that no systemic disease was present at the time. These results were discussed with the patient’s parents and counseling about trigger avoidance was provided. The patient was given pediatric-dosed oral and topical H1 antihistamines for symptom relief.

CORRESPONDENCE

Joshua D. Sparling, MD, 6 E Chestnut Street, Ste 340, Augusta, ME 04330; Joshua.Sparling@MaineGeneral.org

1. Hartmann K, Escribano L, Grattan C, et al . Cutaneous manifestations in patients with mastocytosis: consensus report of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis; the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:35-45.

2. Abid A, Malone MA, Curci K. Mastocytosis. Prim Care. 2016;43:505-518.

3. Forster A, Hartmann K, Horny HP, et al. Large maculopapular cutaneous lesions are associated with favourable outcome in childhood-onset mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:1581-1590.

4. Tharp MD, Sofen BD. Mastocytosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:2103-2104.

5. Carter MC, Clayton ST, Komarow MD, et al. Assessment of clinical findings, tryptase levels and bone marrow histopathology in the management of pediatric mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin

A 2-year-old girl with Fitzpatrick skin type VI who had recently emigrated from Djibouti presented to our dermatology clinic for a rash that appeared when she was 2 months old. The lesions occasionally were pruritic after sun exposure or after crawling outside. There was no associated abdominal pain, diarrhea, flushing, or hypotension. Topical moisturizers were not helpful.

The patient had no known allergies or other notable medical history. Physical examination revealed multiple hyperpigmented, oval-shaped, slightly raised papules and plaques on her torso (FIGURE 1), neck, and arms, and fewer lesions on her face and legs. Darier sign was not appreciated on the initial consult. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the patient’s right middle back was performed at this visit.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Mastocytosis

The presence of a hyperpigmented skin lesion that becomes pruritic, raised, and erythematous when rubbed (Darier sign) is the major criterion for the diagnosis of cutaneous mastocytosis.1 Minor criteria include a skin biopsy demonstrating a 4- to 8-fold increase in the number of mast cells within the papillary dermis and the presence of cKIT mutations.1 In this case, the patient’s punch biopsy results came back positive for clonal mast cell infiltration of the papillary dermis (FIGURES 2A and 2B), and her physician elicited a slightly positive Darier sign during a follow-up visit.

Mastocytosis is characterized by pathognomonic proliferation of clonal mast cells with either cutaneous or systemic involvement.1 Mast cell expansion most commonly is found in the skin and bone marrow; however, involvement of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes also has been documented.1 Nonhereditary somatic mutations of the cKIT gene have been observed in many studies and may be associated with increased proliferation of clonal mast cells.2

A review of the English-language literature on cutaneous mastocytosis reveals a paucity of reports in darker skin types. However, it is important for clinicians to be able to recognize this disease in all skin types.

Three subcategories. Cutaneous mastocytosis is divided into 3 subcategories: mastocytoma of the skin (1–3 solitary skin lesions), maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, also known as urticaria pigmentosa (as seen in our patient; usually ≥ 4 lesions); and diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis (confluent lesions; leathery appearance of skin).1,3,4 Maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, which our patient had, classically develops within the first 6 months of life and presents as hyperpigmented macules and papules.

Keep in mind that systemic involvement in cutaneous mastocytosis occasionally occurs and can be associated with anaphylaxis, flushing, headache, dyspnea, nausea, emesis, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and hepatosplenomegaly.2

Continue to: Narrowing down a broad differential diagnosis

Narrowing down a broad differential diagnosis

Our cas a ase was made somewhat challenging by the patient’s darkly pigmented skin color, which made any erythema and other cutaneous signs less visible. The differential was broad and included postinflammatory hyperpigmentation from eczema, multiple congenital nevi, sarcoidosis, leprosy, and cutaneous tuberculosis, all of which can be eliminated by performing a biopsy of the lesion.

Diagnostic criteria include biopsy and laboratory findings

In addition to a skin biopsy, initial assessment in cases of suspected cutaneous mastocytosis should include a complete blood cell count with differential, liver function tests (+/- liver ultrasound), a serum tryptase level, and a peripheral smear. Serum tryptase levels > 20 ng/mL have been shown to correlate with a higher probability of systemic mastocytosis. Higher tryptase levels also correlate with severity of disease in children.5

Treatment focuses on minimizing mast cell degranulation

Due to the relatively benign course of cutaneous mastocytosis, the mainstay of treatment is focused on minimizing mast cell degranulation to control subsequent symptoms. Avoiding precipitating factors such as temperature extremes, external stimulation of lesions, dry skin, infection, and certain medications (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, morphine, polymyxin B sulphate, anticholinergics, some systemic anesthetics) that can stimulate mast cell degranulation is encouraged.2 H1 and H2 antihistamines are the first-line treatment for mild to moderate symptoms. In refractory cases, leukotriene receptor antagonists or oral cromolyn sodium may be considered.2

Regular follow-up every 6 to 12 months should be established after diagnosis.1 If symptoms persist into adulthood or concern for disease progression is high, a bone marrow biopsy is recommended.1

Our patient

Our patient’s laboratory results revealed a normal serum tryptase level (3.4 ng/mL; reference range < 11.5 ng/mL) and complete blood cell count. A complete metabolic panel demonstrated elevated and high-normal liver function tests with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 111 u/L (reference range, 10–40 u/L) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 55 u/L (reference range, 7–56 u/L).

Continue to: As a precaution...

As a precaution and for consideration of further work-up, such as the need for a liver ultrasound, the patient was referred to Pediatric Gastroenterology. The specialist repeated the liver function tests, the results of which were lower (ALT, 42 u/L; AST, 24 u/L); a liver ultrasound was thought to be unnecessary.

Our patient’s otherwise negative review of systems led the specialist to feel confident that no systemic disease was present at the time. These results were discussed with the patient’s parents and counseling about trigger avoidance was provided. The patient was given pediatric-dosed oral and topical H1 antihistamines for symptom relief.

CORRESPONDENCE

Joshua D. Sparling, MD, 6 E Chestnut Street, Ste 340, Augusta, ME 04330; Joshua.Sparling@MaineGeneral.org

A 2-year-old girl with Fitzpatrick skin type VI who had recently emigrated from Djibouti presented to our dermatology clinic for a rash that appeared when she was 2 months old. The lesions occasionally were pruritic after sun exposure or after crawling outside. There was no associated abdominal pain, diarrhea, flushing, or hypotension. Topical moisturizers were not helpful.

The patient had no known allergies or other notable medical history. Physical examination revealed multiple hyperpigmented, oval-shaped, slightly raised papules and plaques on her torso (FIGURE 1), neck, and arms, and fewer lesions on her face and legs. Darier sign was not appreciated on the initial consult. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the patient’s right middle back was performed at this visit.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Mastocytosis

The presence of a hyperpigmented skin lesion that becomes pruritic, raised, and erythematous when rubbed (Darier sign) is the major criterion for the diagnosis of cutaneous mastocytosis.1 Minor criteria include a skin biopsy demonstrating a 4- to 8-fold increase in the number of mast cells within the papillary dermis and the presence of cKIT mutations.1 In this case, the patient’s punch biopsy results came back positive for clonal mast cell infiltration of the papillary dermis (FIGURES 2A and 2B), and her physician elicited a slightly positive Darier sign during a follow-up visit.

Mastocytosis is characterized by pathognomonic proliferation of clonal mast cells with either cutaneous or systemic involvement.1 Mast cell expansion most commonly is found in the skin and bone marrow; however, involvement of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes also has been documented.1 Nonhereditary somatic mutations of the cKIT gene have been observed in many studies and may be associated with increased proliferation of clonal mast cells.2

A review of the English-language literature on cutaneous mastocytosis reveals a paucity of reports in darker skin types. However, it is important for clinicians to be able to recognize this disease in all skin types.

Three subcategories. Cutaneous mastocytosis is divided into 3 subcategories: mastocytoma of the skin (1–3 solitary skin lesions), maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, also known as urticaria pigmentosa (as seen in our patient; usually ≥ 4 lesions); and diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis (confluent lesions; leathery appearance of skin).1,3,4 Maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, which our patient had, classically develops within the first 6 months of life and presents as hyperpigmented macules and papules.

Keep in mind that systemic involvement in cutaneous mastocytosis occasionally occurs and can be associated with anaphylaxis, flushing, headache, dyspnea, nausea, emesis, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and hepatosplenomegaly.2

Continue to: Narrowing down a broad differential diagnosis

Narrowing down a broad differential diagnosis

Our cas a ase was made somewhat challenging by the patient’s darkly pigmented skin color, which made any erythema and other cutaneous signs less visible. The differential was broad and included postinflammatory hyperpigmentation from eczema, multiple congenital nevi, sarcoidosis, leprosy, and cutaneous tuberculosis, all of which can be eliminated by performing a biopsy of the lesion.

Diagnostic criteria include biopsy and laboratory findings

In addition to a skin biopsy, initial assessment in cases of suspected cutaneous mastocytosis should include a complete blood cell count with differential, liver function tests (+/- liver ultrasound), a serum tryptase level, and a peripheral smear. Serum tryptase levels > 20 ng/mL have been shown to correlate with a higher probability of systemic mastocytosis. Higher tryptase levels also correlate with severity of disease in children.5

Treatment focuses on minimizing mast cell degranulation

Due to the relatively benign course of cutaneous mastocytosis, the mainstay of treatment is focused on minimizing mast cell degranulation to control subsequent symptoms. Avoiding precipitating factors such as temperature extremes, external stimulation of lesions, dry skin, infection, and certain medications (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, morphine, polymyxin B sulphate, anticholinergics, some systemic anesthetics) that can stimulate mast cell degranulation is encouraged.2 H1 and H2 antihistamines are the first-line treatment for mild to moderate symptoms. In refractory cases, leukotriene receptor antagonists or oral cromolyn sodium may be considered.2

Regular follow-up every 6 to 12 months should be established after diagnosis.1 If symptoms persist into adulthood or concern for disease progression is high, a bone marrow biopsy is recommended.1

Our patient

Our patient’s laboratory results revealed a normal serum tryptase level (3.4 ng/mL; reference range < 11.5 ng/mL) and complete blood cell count. A complete metabolic panel demonstrated elevated and high-normal liver function tests with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 111 u/L (reference range, 10–40 u/L) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 55 u/L (reference range, 7–56 u/L).

Continue to: As a precaution...

As a precaution and for consideration of further work-up, such as the need for a liver ultrasound, the patient was referred to Pediatric Gastroenterology. The specialist repeated the liver function tests, the results of which were lower (ALT, 42 u/L; AST, 24 u/L); a liver ultrasound was thought to be unnecessary.

Our patient’s otherwise negative review of systems led the specialist to feel confident that no systemic disease was present at the time. These results were discussed with the patient’s parents and counseling about trigger avoidance was provided. The patient was given pediatric-dosed oral and topical H1 antihistamines for symptom relief.

CORRESPONDENCE

Joshua D. Sparling, MD, 6 E Chestnut Street, Ste 340, Augusta, ME 04330; Joshua.Sparling@MaineGeneral.org

1. Hartmann K, Escribano L, Grattan C, et al . Cutaneous manifestations in patients with mastocytosis: consensus report of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis; the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:35-45.

2. Abid A, Malone MA, Curci K. Mastocytosis. Prim Care. 2016;43:505-518.

3. Forster A, Hartmann K, Horny HP, et al. Large maculopapular cutaneous lesions are associated with favourable outcome in childhood-onset mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:1581-1590.

4. Tharp MD, Sofen BD. Mastocytosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:2103-2104.

5. Carter MC, Clayton ST, Komarow MD, et al. Assessment of clinical findings, tryptase levels and bone marrow histopathology in the management of pediatric mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin

1. Hartmann K, Escribano L, Grattan C, et al . Cutaneous manifestations in patients with mastocytosis: consensus report of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis; the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:35-45.

2. Abid A, Malone MA, Curci K. Mastocytosis. Prim Care. 2016;43:505-518.

3. Forster A, Hartmann K, Horny HP, et al. Large maculopapular cutaneous lesions are associated with favourable outcome in childhood-onset mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:1581-1590.

4. Tharp MD, Sofen BD. Mastocytosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:2103-2104.

5. Carter MC, Clayton ST, Komarow MD, et al. Assessment of clinical findings, tryptase levels and bone marrow histopathology in the management of pediatric mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin