User login

4.03 Healthcare Systems: Consultation and Co-management

Introduction

Pediatric hospitalists are often asked to offer clinical guidance, recommendations, or support to healthcare providers in managing children in a variety of contexts. These providers are usually adult providers or other pediatric subspecialists. There are two general models for this arrangement: consultation and co-management. Consultation generally refers to a paradigm in which the primary team requests input to manage a specific clinical problem or set of problems that would benefit from specific expertise. Co-management describes a model in which a patient requires ongoing care served via a partnership between the primary team and another specialty service. Consultation and co-management roles for pediatric hospitalists involve caring for medical and surgical patients. Many different models exist within these two broad categories. These models vary based on setting, local needs, or local pediatric expertise. Regardless of model, similar skills are required, especially involving communication and coordination of care. Pediatric hospitalists are in a unique position to improve care delivery and advocate for the needs of children within consultation and co-management roles.

Knowledge

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Describe consultation and co-management models, including characteristics of local models.

- Articulate the responsibilities typically defined by consultation and co-management models.

- Review the importance of clear communication, multidisciplinary team engagement, and roles of different care providers within a consulting and co-management model.

- Compare and contrast the value of verbal versus written agreements for consultation and co-management relationships and discuss their impact on patient safety.

- Discuss the intent and impact of mandatory consultation for hospitalized children based on certain criteria, such as age or underlying condition, especially regarding patient safety and the role of pediatric hospitalists.

- Recognize opportunities for pediatric consultation to offer recommendations for the whole child, attending to immunizations, dental care, and other preventative needs.

- State examples where a one-time consultation may be appropriate.

- Describe common failures in consultation and co-management, especially regarding handoffs, patient communication, documentation, billing, and others.

- Summarize basic surgical conditions, indications for common surgical procedures, and list common complications of surgical procedures.

- Describe the principles of preoperative and perioperative care, including roles for anesthesiologists, subspecialists, surgeons, and pediatric hospitalists.

- Describe common pain management modalities, including medication and non-medication interventions, attending to potential side effects of medications including narcotics.

- Compare and contrast billing procedures for consultation and co-management from billing as primary attending of record, with attention to the impact of billing by other providers.

Skills

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Provide a timely and comprehensive evaluation of pediatric patients and pediatric-specific recommendations.

- Demonstrate strong diagnostic and management skills in the care of hospitalized children, including those with medical complexity and common surgical conditions.

- Communicate recommendations clearly and efficiently to other subspecialists and healthcare providers.

- Diagnose complications of common surgical procedures, including features of clinical deterioration.

- Communicate effectively with the primary team regarding complications or other declines in status and triage to a higher level of care as appropriate.

- Identify and abate pediatric-specific patient risks due to age, underlying condition, local resources, or other factors.

- Coordinate care and communicate clearly and effectively with patients, the family/caregivers, and all team members.

- Demonstrate expertise in pain management, especially in the perioperative patient.

- Describe principles of perioperative fluid management in the pediatric surgical patient.

- Explain the pediatric hospitalist’s role in consultation and co-management with the patient and the family/caregivers.

- Maintain clear, timely communication and documentation of clinical recommendations.

- Place patient care orders when appropriate.

- Educate trainees, including pediatric and surgical trainees, about models of consultation and co-management.

- Create a comprehensive discharge plan in partnership with the primary team.

Attitudes

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Exemplify responsible and accountable care of hospitalized children within the scope of the consultation and co-management relationship across differing clinical specialties.

- Reflect on the importance of providing timely patient care, documentation of recommendations, and written orders as appropriate.

- Realize the importance of communicating effectively with patients, the family/caregivers, subspecialists, and other healthcare providers.

- Respect the contributions of all healthcare team members.

- Recognize that gaps in knowledge and skills may adversely impact patient care and role model behaviors that promote patient safety and quality care.

Systems Organization and Improvement

In order to improve efficiency and quality within their organizations, pediatric hospitalists should:

- Collaborate with other subspecialist leaders by providing input to improve consultation and co-management programs.

- Identify opportunities to lead, coordinate, or participate in activities to enhance teamwork between healthcare professionals.

- Lead, coordinate, or participate in identifying and managing aspects of consultation and co-management care that may be targets for quality improvement.

- Collaborate with administrators and colleagues to optimize hospitalist value provided and assure practice is appropriately within the scope of the hospital medicine.

- Lead, coordinate, or participate in the development of guidelines for consultation and co-management programs.

1. Rappaport DI, Rosenberg RE, Shaughnessy EE, et al. Pediatric hospitalist comanagement of surgical patients: Structural, quality, and financial considerations. J Hosp Med. 2014 Nov;9(11):737–742. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2266.

2. Society for Hospital Medicine. Resources for Effective Co-Management of Hospitalized Patients. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/co-management/. Accessed August 26, 2019.

Introduction

Pediatric hospitalists are often asked to offer clinical guidance, recommendations, or support to healthcare providers in managing children in a variety of contexts. These providers are usually adult providers or other pediatric subspecialists. There are two general models for this arrangement: consultation and co-management. Consultation generally refers to a paradigm in which the primary team requests input to manage a specific clinical problem or set of problems that would benefit from specific expertise. Co-management describes a model in which a patient requires ongoing care served via a partnership between the primary team and another specialty service. Consultation and co-management roles for pediatric hospitalists involve caring for medical and surgical patients. Many different models exist within these two broad categories. These models vary based on setting, local needs, or local pediatric expertise. Regardless of model, similar skills are required, especially involving communication and coordination of care. Pediatric hospitalists are in a unique position to improve care delivery and advocate for the needs of children within consultation and co-management roles.

Knowledge

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Describe consultation and co-management models, including characteristics of local models.

- Articulate the responsibilities typically defined by consultation and co-management models.

- Review the importance of clear communication, multidisciplinary team engagement, and roles of different care providers within a consulting and co-management model.

- Compare and contrast the value of verbal versus written agreements for consultation and co-management relationships and discuss their impact on patient safety.

- Discuss the intent and impact of mandatory consultation for hospitalized children based on certain criteria, such as age or underlying condition, especially regarding patient safety and the role of pediatric hospitalists.

- Recognize opportunities for pediatric consultation to offer recommendations for the whole child, attending to immunizations, dental care, and other preventative needs.

- State examples where a one-time consultation may be appropriate.

- Describe common failures in consultation and co-management, especially regarding handoffs, patient communication, documentation, billing, and others.

- Summarize basic surgical conditions, indications for common surgical procedures, and list common complications of surgical procedures.

- Describe the principles of preoperative and perioperative care, including roles for anesthesiologists, subspecialists, surgeons, and pediatric hospitalists.

- Describe common pain management modalities, including medication and non-medication interventions, attending to potential side effects of medications including narcotics.

- Compare and contrast billing procedures for consultation and co-management from billing as primary attending of record, with attention to the impact of billing by other providers.

Skills

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Provide a timely and comprehensive evaluation of pediatric patients and pediatric-specific recommendations.

- Demonstrate strong diagnostic and management skills in the care of hospitalized children, including those with medical complexity and common surgical conditions.

- Communicate recommendations clearly and efficiently to other subspecialists and healthcare providers.

- Diagnose complications of common surgical procedures, including features of clinical deterioration.

- Communicate effectively with the primary team regarding complications or other declines in status and triage to a higher level of care as appropriate.

- Identify and abate pediatric-specific patient risks due to age, underlying condition, local resources, or other factors.

- Coordinate care and communicate clearly and effectively with patients, the family/caregivers, and all team members.

- Demonstrate expertise in pain management, especially in the perioperative patient.

- Describe principles of perioperative fluid management in the pediatric surgical patient.

- Explain the pediatric hospitalist’s role in consultation and co-management with the patient and the family/caregivers.

- Maintain clear, timely communication and documentation of clinical recommendations.

- Place patient care orders when appropriate.

- Educate trainees, including pediatric and surgical trainees, about models of consultation and co-management.

- Create a comprehensive discharge plan in partnership with the primary team.

Attitudes

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Exemplify responsible and accountable care of hospitalized children within the scope of the consultation and co-management relationship across differing clinical specialties.

- Reflect on the importance of providing timely patient care, documentation of recommendations, and written orders as appropriate.

- Realize the importance of communicating effectively with patients, the family/caregivers, subspecialists, and other healthcare providers.

- Respect the contributions of all healthcare team members.

- Recognize that gaps in knowledge and skills may adversely impact patient care and role model behaviors that promote patient safety and quality care.

Systems Organization and Improvement

In order to improve efficiency and quality within their organizations, pediatric hospitalists should:

- Collaborate with other subspecialist leaders by providing input to improve consultation and co-management programs.

- Identify opportunities to lead, coordinate, or participate in activities to enhance teamwork between healthcare professionals.

- Lead, coordinate, or participate in identifying and managing aspects of consultation and co-management care that may be targets for quality improvement.

- Collaborate with administrators and colleagues to optimize hospitalist value provided and assure practice is appropriately within the scope of the hospital medicine.

- Lead, coordinate, or participate in the development of guidelines for consultation and co-management programs.

Introduction

Pediatric hospitalists are often asked to offer clinical guidance, recommendations, or support to healthcare providers in managing children in a variety of contexts. These providers are usually adult providers or other pediatric subspecialists. There are two general models for this arrangement: consultation and co-management. Consultation generally refers to a paradigm in which the primary team requests input to manage a specific clinical problem or set of problems that would benefit from specific expertise. Co-management describes a model in which a patient requires ongoing care served via a partnership between the primary team and another specialty service. Consultation and co-management roles for pediatric hospitalists involve caring for medical and surgical patients. Many different models exist within these two broad categories. These models vary based on setting, local needs, or local pediatric expertise. Regardless of model, similar skills are required, especially involving communication and coordination of care. Pediatric hospitalists are in a unique position to improve care delivery and advocate for the needs of children within consultation and co-management roles.

Knowledge

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Describe consultation and co-management models, including characteristics of local models.

- Articulate the responsibilities typically defined by consultation and co-management models.

- Review the importance of clear communication, multidisciplinary team engagement, and roles of different care providers within a consulting and co-management model.

- Compare and contrast the value of verbal versus written agreements for consultation and co-management relationships and discuss their impact on patient safety.

- Discuss the intent and impact of mandatory consultation for hospitalized children based on certain criteria, such as age or underlying condition, especially regarding patient safety and the role of pediatric hospitalists.

- Recognize opportunities for pediatric consultation to offer recommendations for the whole child, attending to immunizations, dental care, and other preventative needs.

- State examples where a one-time consultation may be appropriate.

- Describe common failures in consultation and co-management, especially regarding handoffs, patient communication, documentation, billing, and others.

- Summarize basic surgical conditions, indications for common surgical procedures, and list common complications of surgical procedures.

- Describe the principles of preoperative and perioperative care, including roles for anesthesiologists, subspecialists, surgeons, and pediatric hospitalists.

- Describe common pain management modalities, including medication and non-medication interventions, attending to potential side effects of medications including narcotics.

- Compare and contrast billing procedures for consultation and co-management from billing as primary attending of record, with attention to the impact of billing by other providers.

Skills

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Provide a timely and comprehensive evaluation of pediatric patients and pediatric-specific recommendations.

- Demonstrate strong diagnostic and management skills in the care of hospitalized children, including those with medical complexity and common surgical conditions.

- Communicate recommendations clearly and efficiently to other subspecialists and healthcare providers.

- Diagnose complications of common surgical procedures, including features of clinical deterioration.

- Communicate effectively with the primary team regarding complications or other declines in status and triage to a higher level of care as appropriate.

- Identify and abate pediatric-specific patient risks due to age, underlying condition, local resources, or other factors.

- Coordinate care and communicate clearly and effectively with patients, the family/caregivers, and all team members.

- Demonstrate expertise in pain management, especially in the perioperative patient.

- Describe principles of perioperative fluid management in the pediatric surgical patient.

- Explain the pediatric hospitalist’s role in consultation and co-management with the patient and the family/caregivers.

- Maintain clear, timely communication and documentation of clinical recommendations.

- Place patient care orders when appropriate.

- Educate trainees, including pediatric and surgical trainees, about models of consultation and co-management.

- Create a comprehensive discharge plan in partnership with the primary team.

Attitudes

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Exemplify responsible and accountable care of hospitalized children within the scope of the consultation and co-management relationship across differing clinical specialties.

- Reflect on the importance of providing timely patient care, documentation of recommendations, and written orders as appropriate.

- Realize the importance of communicating effectively with patients, the family/caregivers, subspecialists, and other healthcare providers.

- Respect the contributions of all healthcare team members.

- Recognize that gaps in knowledge and skills may adversely impact patient care and role model behaviors that promote patient safety and quality care.

Systems Organization and Improvement

In order to improve efficiency and quality within their organizations, pediatric hospitalists should:

- Collaborate with other subspecialist leaders by providing input to improve consultation and co-management programs.

- Identify opportunities to lead, coordinate, or participate in activities to enhance teamwork between healthcare professionals.

- Lead, coordinate, or participate in identifying and managing aspects of consultation and co-management care that may be targets for quality improvement.

- Collaborate with administrators and colleagues to optimize hospitalist value provided and assure practice is appropriately within the scope of the hospital medicine.

- Lead, coordinate, or participate in the development of guidelines for consultation and co-management programs.

1. Rappaport DI, Rosenberg RE, Shaughnessy EE, et al. Pediatric hospitalist comanagement of surgical patients: Structural, quality, and financial considerations. J Hosp Med. 2014 Nov;9(11):737–742. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2266.

2. Society for Hospital Medicine. Resources for Effective Co-Management of Hospitalized Patients. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/co-management/. Accessed August 26, 2019.

1. Rappaport DI, Rosenberg RE, Shaughnessy EE, et al. Pediatric hospitalist comanagement of surgical patients: Structural, quality, and financial considerations. J Hosp Med. 2014 Nov;9(11):737–742. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2266.

2. Society for Hospital Medicine. Resources for Effective Co-Management of Hospitalized Patients. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/co-management/. Accessed August 26, 2019.

Clinical Progress Note: Perioperative Pain Control in Hospitalized Pediatric Patients

Pediatric hospitalists play an increasingly significant role in perioperative pain management.1 Advances in pediatric surgical comanagement may improve quality of care and reduce the length of hospitalization.2 This review is based on queries of the PubMed and Cochrane databases between January 1, 2014, and July 15, 2019, using the search terms “perioperative pain management,” “postoperative pain,” “pediatric,” and “children.” In addition, the authors reviewed key position statements from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American Pain Society (APS), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) regarding pain management.3 This update is intended to be relevant for practicing pediatric hospitalists, with a focus on recently expanded options for pain management and judicious opioid use in hospitalized children.

PERIOPERATIVE PAIN MANAGEMENT

Postoperative pain management begins preoperatively according to the concept of the perioperative surgical home (PSH).4 The preoperative history should identify the patient’s previous positive (eg, good pain control) and negative (eg, adverse reactions) experiences with pain medications. Family and patient expectations should be discussed regarding types and sources of pain, pain duration, exacerbating/alleviating factors, and modalities available for realistic pain control because preoperative information can limit anxiety and improve outcomes. Pain specialists can perform risk assessments preoperatively and develop plans to address pharmacologic tolerance, withdrawal, and opioid-induced hyperalgesia after surgery.5 Children with chronic pain and on preoperative opioids may require more analgesia for a longer duration postoperatively. Early recognition of variability of patient’s pain perception and differences in responses to pain need to be clearly communicated across the disciplines in a collaborative model of care.

Children with medical complexity and/or cognitive, emotional, or behavioral impairments may benefit from preoperative psychosocial treatments and utilization of pain self-management training and strategies that could further reduce anxiety and optimize postoperative care because patient and parental preoperative anxiety may be associated with adverse outcomes. Validated pain assessment tools like Revised FLACC (Face, Leg, Activity, Cry, and Consolability) Scale and Individualized Numeric Rating Scale could be particularly useful in children with limitations in communication or altered pain perception; therefore, medical teams and family members should discuss their utilization preoperatively.

MULTIMODAL ANALGESIA

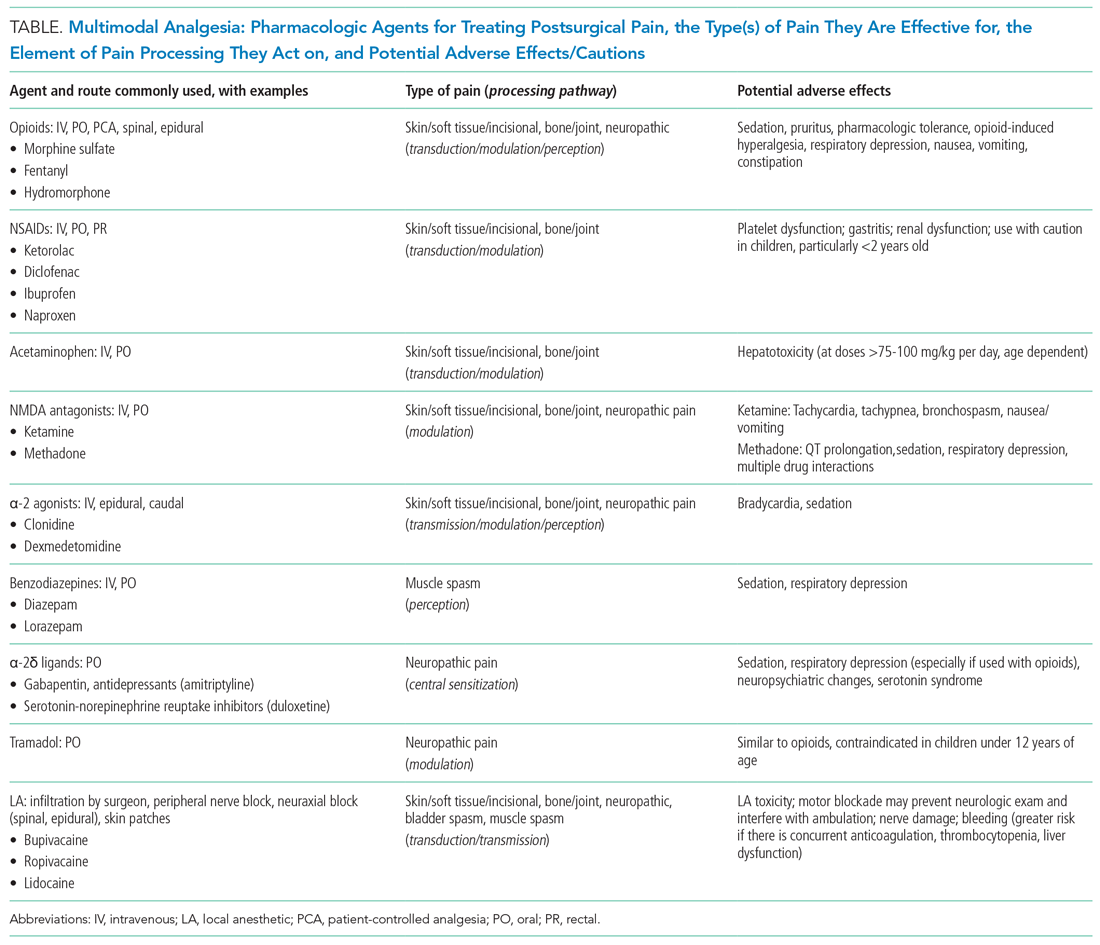

Multimodal analgesia (MMA) is a strategy that synergistically uses pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic modalities to target pain at multiple points of the pain processing pathway (Table).6 MMA can optimize pain control by addressing different types of pain (eg, incisional pain, muscle spasm, or neuropathic pain), expedite recovery, reduce potential pharmacologic side effects, and decrease opioid consumption. Patients taking opioids are at an increased risk of developing opioid-related side effects such as respiratory depression, medication tolerance, and anxiety, with resultant longer hospital stay, increased readmissions, and higher costs of care.7 Treatment for postoperative pain should prioritize appropriately dosed and precisely scheduled MMA before opioid-focused analgesia with the goals of decreasing opioid-related adverse effects, intentional misuse, diversion, and accidental ingestions. The AAP, APS, CDC, and SHM endorse the use of MMA and recommend nonpharmacologic measures and regional anesthesia.8,9 The most used modalities in MMA are discussed below.

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen has central-acting analgesic and antipyretic properties and readily crosses the blood brain barrier, which makes it particularly useful in spine and neurological surgeries. Oral administration is preferred when feasible. The AAP recommends refraining from rectal administration of acetaminophen as analgesia in children because of concerns about toxic effects and erratic, variable absorption.10 A systematic review of six studies found no benefit in pain control between intravenous (IV) and oral (PO) administration of acetaminophen in adults.11 There is a paucity of studies in children comparing PO with IV acetaminophen perioperative efficacy. Children may benefit from IV formulations in the early postoperative period, in cases with frequent nausea and vomiting, and in those with oral medication intolerance. Since infants have greater risk of respiratory depression from opioids, IV acetaminophen may have utility in this age group. Because of the cost associated with IV formulation, some institutions restrict IV acetaminophen. However, rapidly well-controlled pain and minimization of opioid-related side effects with shorter hospital stays may lower healthcare costs despite the cost of acetaminophen itself.

NSAIDs

NSAIDs possess anti-inflammatory properties through the inhibition of cyclooxygenase and blockade of prostaglandin production. NSAID risks include bleeding, renal and gastrointestinal toxicities, and potentially delayed wound and bone healing. Ketorolac is an NSAID that continues to be widely used with demonstrated opioid-sparing effects. Many retrospective studies including large numbers of pediatric patients have not demonstrated increased risks of bleeding nor poor wound healing with short postoperative use. A Cochrane review, however, concluded that there is insufficient data to either support or reject the efficacy or safety of ketorolac for postoperative pain treatment in children, mostly because of the very low quality of evidence.12

Regional Anesthesia

Regional anesthesia, which includes central (spinal/epidural/caudal) and peripheral blocks, decreases postoperative pain and opioid-associated side effects. Blocks typically consist of local anesthetic with or without the addition of adjuncts (eg, clonidine, dexamethasone). Regional anesthesia may also improve pulmonary function, compared with that of nonregional MMA use, in patients who have thoracic or upper abdominal surgeries. While having broad applications, the utility of regional anesthesia is greatest in preterm infants/neonates and in those with underlying respiratory pathology. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials demonstrated that regional anesthesia decreased opioid consumption and minimized postoperative pain with no significant complications attributed to its use.13 Additional studies are needed to better delineate specific surgical procedures and subpopulations of pediatric patients in which regional anesthesia may provide the most benefit.

Gabapentinoids

Children receiving gabapentinoids perioperatively have been shown to have fewer adverse reactions, decreased opioid consumption, and less anxiety, as well as improved pain scores. Gabapentin is increasingly being utilized for children with idiopathic scoliosis undergoing posterior spinal fusion, and there is some evidence for improving pain control and reducing opioid use. However, a recent systematic review found a paucity of data supporting its clinical use.14 Both gabapentin and pregabalin may further increase risks of respiratory depression, especially in synergy with opioids and benzodiazepines.

Opioids

Opioids should be used with caution in pediatric patients and are reserved primarily for the management of severe acute pain. The shortest duration of the lowest effective dose of opioids should be encouraged. Patient-controlled opioid analgesia (PCA) offers benefits when parenteral postoperative analgesia is indicated: It maximizes pain relief, minimizes risk of overdose, and improves psychological well-being through self-administration of pain medicines. Basal-infusion PCA should not be routinely used because it is associated with nausea, vomiting, and respiratory depression without having superior analgesia compared with demand use only. Monitoring of side stream end-tidal capnography can readily detect respiratory depression, especially if opioids, benzodiazepines, gabapentinoids, and diphenhydramine are used concomitantly. Patient education regarding opioid use, side effects, safe storage, and disposal practices is imperative because significant amounts of opioids remain in households after completion of treatment for pain and because opioid diversion and accidental ingestions account for significant morbidity. Providers need to balance efficient pain management with opioid stewardship, complying with state and federal policies to limit harm related to opioid diversion.15

Nonpharmacological Modalities

The use of nonpharmacologic therapies, along with pharmacologic modalities, for perioperative pain management has been shown to decrease opioid use and opioid-related side effects. Trials of acupressure have demonstrated improvement in nausea and vomiting, sleep quality, and pain and anxiety scores. Nonpharmacologic treatments currently serve as a complementary approach for pain and anxiety management in the perioperative setting including acupuncture, acupressure, osteopathic manipulative treatment, massage, meditation, biofeedback, hypnotherapy, and physical/occupational, relaxation, cognitive-behavioral, chiropractic, music, and art therapies. The Joint Commission suggests consideration of such modalities by hospitals.

FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS

Pediatric hospitalists have been traditionally involved in research and patient care improvements and should continue to actively contribute to establishing evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of acute postoperative pain in hospitalized children and adolescents. The sparsity of high-quality evidence prompts the need for more research. A standardized approach to perioperative pain management in the form of checklists, pathways, and protocols for specific procedures may be useful to educate providers and patients, while also standardizing available evidence-based interventions (eg, pediatric Enhanced Recovery After Surgery [ERAS] protocols).

CONCLUSION

Combining multimodal pharmacologic and integrative nonpharmacologic modalities can decrease opioid use and related side effects and improve the perioperative care of hospitalized children. Pediatric hospitalists have an opportunity to optimize care preoperatively, practice multimodal analgesia, and contribute to reducing risk of opioid diversion post operatively.

1. Society of Hospital Medicine Co-Management Advisory Panel. A white paper on a guide to hospitalist/orthopedic surgery co-management. http://tools.hospitalmedicine.org/Implementation/Co-ManagementWhitePaper-final_5-10-10.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2019.

2. Rappaport DI, Rosenberg RE, Shaughnessy EE, et al. Pediatric hospitalist comanagement of surgical patients: Structural, quality, and financial considerations. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(11):737-742. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2266.

3. Evidence-Based Nonpharmacologic Strategies for Comprehensive Pain Care: The Consortium Pain Task Force White Paper. http://www.nonpharmpaincare.org. Accessed on October 11, 2019.

4. Vetter TR, Kain ZN. Role of perioperative surgical home in optimizing the perioperative use of opioids. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(5):1653-1657. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000002280.

5. Edwards DA, Hedrick TL, Jayaram J, et al. American Society for Enhanced Recovery and Perioperative Quality Initiative joint consensus statement on perioperative management of patients on preoperative opioid therapy. Anesth Analg. 2019;129(2):553-566. http://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000004018.

6. Micromedex (electronic version). IBM Watson Health. Greenwood Village, Colorado, USA. https://www.micromedexsolutions.com. Accessed October 10, 2019.

7. Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Management of postoperative pain: A clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain. 2016;17(2):131-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008.

8. Herzig SJ, Mosher HJ, Calcaterra SL, Jena AB, Nuckols TK. Improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: A consensus statement from the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;3(4):263-266. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2980.

9. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain – United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624-1645. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.1464.

10. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs. Acetaminophen toxicity in children. Pediatrics. 2001;108 (4):1020-1024. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.108.4.1020.

11. Jibril F, Sharaby S, Mohamed A, Wilby, KJ. Intravenous versus oral acetaminophen for pain: Systemic review of current evidence to support clinical decision-making. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2015;68(3):238-247. https://doi.org/10.4212/cjhp.v68i3.1458.

12. McNicol ED, Rowe E, Cooper TE. Ketorolac for postoperative pain in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7(7). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012294.pub2.

13. Kendall MC, Castro Alves LJ, Suh EI, McCormick ZL, De Oliveira GS. Regional anesthesia to ameliorate postoperative analgesia outcomes in pediatric surgical patients: an updated systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Local Reg Anesth. 2018;11:91-109. https://doi.org/10.2147/LRA.S185554.

14. Egunsola 0, Wylie CE, Chitty KM, et al. Systematic review of the efficacy and safety of gabapentin and pregabalin for pain in children and adolescents. Anesth Analg. 2019;128(4):811-819. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000003936.

15. Harbaugh C, Gadepalli SK. Pediatric postoperative opioid prescribing and the opioid crisis. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2019;31(3):377-385. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000000768.

Pediatric hospitalists play an increasingly significant role in perioperative pain management.1 Advances in pediatric surgical comanagement may improve quality of care and reduce the length of hospitalization.2 This review is based on queries of the PubMed and Cochrane databases between January 1, 2014, and July 15, 2019, using the search terms “perioperative pain management,” “postoperative pain,” “pediatric,” and “children.” In addition, the authors reviewed key position statements from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American Pain Society (APS), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) regarding pain management.3 This update is intended to be relevant for practicing pediatric hospitalists, with a focus on recently expanded options for pain management and judicious opioid use in hospitalized children.

PERIOPERATIVE PAIN MANAGEMENT

Postoperative pain management begins preoperatively according to the concept of the perioperative surgical home (PSH).4 The preoperative history should identify the patient’s previous positive (eg, good pain control) and negative (eg, adverse reactions) experiences with pain medications. Family and patient expectations should be discussed regarding types and sources of pain, pain duration, exacerbating/alleviating factors, and modalities available for realistic pain control because preoperative information can limit anxiety and improve outcomes. Pain specialists can perform risk assessments preoperatively and develop plans to address pharmacologic tolerance, withdrawal, and opioid-induced hyperalgesia after surgery.5 Children with chronic pain and on preoperative opioids may require more analgesia for a longer duration postoperatively. Early recognition of variability of patient’s pain perception and differences in responses to pain need to be clearly communicated across the disciplines in a collaborative model of care.

Children with medical complexity and/or cognitive, emotional, or behavioral impairments may benefit from preoperative psychosocial treatments and utilization of pain self-management training and strategies that could further reduce anxiety and optimize postoperative care because patient and parental preoperative anxiety may be associated with adverse outcomes. Validated pain assessment tools like Revised FLACC (Face, Leg, Activity, Cry, and Consolability) Scale and Individualized Numeric Rating Scale could be particularly useful in children with limitations in communication or altered pain perception; therefore, medical teams and family members should discuss their utilization preoperatively.

MULTIMODAL ANALGESIA

Multimodal analgesia (MMA) is a strategy that synergistically uses pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic modalities to target pain at multiple points of the pain processing pathway (Table).6 MMA can optimize pain control by addressing different types of pain (eg, incisional pain, muscle spasm, or neuropathic pain), expedite recovery, reduce potential pharmacologic side effects, and decrease opioid consumption. Patients taking opioids are at an increased risk of developing opioid-related side effects such as respiratory depression, medication tolerance, and anxiety, with resultant longer hospital stay, increased readmissions, and higher costs of care.7 Treatment for postoperative pain should prioritize appropriately dosed and precisely scheduled MMA before opioid-focused analgesia with the goals of decreasing opioid-related adverse effects, intentional misuse, diversion, and accidental ingestions. The AAP, APS, CDC, and SHM endorse the use of MMA and recommend nonpharmacologic measures and regional anesthesia.8,9 The most used modalities in MMA are discussed below.

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen has central-acting analgesic and antipyretic properties and readily crosses the blood brain barrier, which makes it particularly useful in spine and neurological surgeries. Oral administration is preferred when feasible. The AAP recommends refraining from rectal administration of acetaminophen as analgesia in children because of concerns about toxic effects and erratic, variable absorption.10 A systematic review of six studies found no benefit in pain control between intravenous (IV) and oral (PO) administration of acetaminophen in adults.11 There is a paucity of studies in children comparing PO with IV acetaminophen perioperative efficacy. Children may benefit from IV formulations in the early postoperative period, in cases with frequent nausea and vomiting, and in those with oral medication intolerance. Since infants have greater risk of respiratory depression from opioids, IV acetaminophen may have utility in this age group. Because of the cost associated with IV formulation, some institutions restrict IV acetaminophen. However, rapidly well-controlled pain and minimization of opioid-related side effects with shorter hospital stays may lower healthcare costs despite the cost of acetaminophen itself.

NSAIDs

NSAIDs possess anti-inflammatory properties through the inhibition of cyclooxygenase and blockade of prostaglandin production. NSAID risks include bleeding, renal and gastrointestinal toxicities, and potentially delayed wound and bone healing. Ketorolac is an NSAID that continues to be widely used with demonstrated opioid-sparing effects. Many retrospective studies including large numbers of pediatric patients have not demonstrated increased risks of bleeding nor poor wound healing with short postoperative use. A Cochrane review, however, concluded that there is insufficient data to either support or reject the efficacy or safety of ketorolac for postoperative pain treatment in children, mostly because of the very low quality of evidence.12

Regional Anesthesia

Regional anesthesia, which includes central (spinal/epidural/caudal) and peripheral blocks, decreases postoperative pain and opioid-associated side effects. Blocks typically consist of local anesthetic with or without the addition of adjuncts (eg, clonidine, dexamethasone). Regional anesthesia may also improve pulmonary function, compared with that of nonregional MMA use, in patients who have thoracic or upper abdominal surgeries. While having broad applications, the utility of regional anesthesia is greatest in preterm infants/neonates and in those with underlying respiratory pathology. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials demonstrated that regional anesthesia decreased opioid consumption and minimized postoperative pain with no significant complications attributed to its use.13 Additional studies are needed to better delineate specific surgical procedures and subpopulations of pediatric patients in which regional anesthesia may provide the most benefit.

Gabapentinoids

Children receiving gabapentinoids perioperatively have been shown to have fewer adverse reactions, decreased opioid consumption, and less anxiety, as well as improved pain scores. Gabapentin is increasingly being utilized for children with idiopathic scoliosis undergoing posterior spinal fusion, and there is some evidence for improving pain control and reducing opioid use. However, a recent systematic review found a paucity of data supporting its clinical use.14 Both gabapentin and pregabalin may further increase risks of respiratory depression, especially in synergy with opioids and benzodiazepines.

Opioids

Opioids should be used with caution in pediatric patients and are reserved primarily for the management of severe acute pain. The shortest duration of the lowest effective dose of opioids should be encouraged. Patient-controlled opioid analgesia (PCA) offers benefits when parenteral postoperative analgesia is indicated: It maximizes pain relief, minimizes risk of overdose, and improves psychological well-being through self-administration of pain medicines. Basal-infusion PCA should not be routinely used because it is associated with nausea, vomiting, and respiratory depression without having superior analgesia compared with demand use only. Monitoring of side stream end-tidal capnography can readily detect respiratory depression, especially if opioids, benzodiazepines, gabapentinoids, and diphenhydramine are used concomitantly. Patient education regarding opioid use, side effects, safe storage, and disposal practices is imperative because significant amounts of opioids remain in households after completion of treatment for pain and because opioid diversion and accidental ingestions account for significant morbidity. Providers need to balance efficient pain management with opioid stewardship, complying with state and federal policies to limit harm related to opioid diversion.15

Nonpharmacological Modalities

The use of nonpharmacologic therapies, along with pharmacologic modalities, for perioperative pain management has been shown to decrease opioid use and opioid-related side effects. Trials of acupressure have demonstrated improvement in nausea and vomiting, sleep quality, and pain and anxiety scores. Nonpharmacologic treatments currently serve as a complementary approach for pain and anxiety management in the perioperative setting including acupuncture, acupressure, osteopathic manipulative treatment, massage, meditation, biofeedback, hypnotherapy, and physical/occupational, relaxation, cognitive-behavioral, chiropractic, music, and art therapies. The Joint Commission suggests consideration of such modalities by hospitals.

FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS

Pediatric hospitalists have been traditionally involved in research and patient care improvements and should continue to actively contribute to establishing evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of acute postoperative pain in hospitalized children and adolescents. The sparsity of high-quality evidence prompts the need for more research. A standardized approach to perioperative pain management in the form of checklists, pathways, and protocols for specific procedures may be useful to educate providers and patients, while also standardizing available evidence-based interventions (eg, pediatric Enhanced Recovery After Surgery [ERAS] protocols).

CONCLUSION

Combining multimodal pharmacologic and integrative nonpharmacologic modalities can decrease opioid use and related side effects and improve the perioperative care of hospitalized children. Pediatric hospitalists have an opportunity to optimize care preoperatively, practice multimodal analgesia, and contribute to reducing risk of opioid diversion post operatively.

Pediatric hospitalists play an increasingly significant role in perioperative pain management.1 Advances in pediatric surgical comanagement may improve quality of care and reduce the length of hospitalization.2 This review is based on queries of the PubMed and Cochrane databases between January 1, 2014, and July 15, 2019, using the search terms “perioperative pain management,” “postoperative pain,” “pediatric,” and “children.” In addition, the authors reviewed key position statements from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American Pain Society (APS), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) regarding pain management.3 This update is intended to be relevant for practicing pediatric hospitalists, with a focus on recently expanded options for pain management and judicious opioid use in hospitalized children.

PERIOPERATIVE PAIN MANAGEMENT

Postoperative pain management begins preoperatively according to the concept of the perioperative surgical home (PSH).4 The preoperative history should identify the patient’s previous positive (eg, good pain control) and negative (eg, adverse reactions) experiences with pain medications. Family and patient expectations should be discussed regarding types and sources of pain, pain duration, exacerbating/alleviating factors, and modalities available for realistic pain control because preoperative information can limit anxiety and improve outcomes. Pain specialists can perform risk assessments preoperatively and develop plans to address pharmacologic tolerance, withdrawal, and opioid-induced hyperalgesia after surgery.5 Children with chronic pain and on preoperative opioids may require more analgesia for a longer duration postoperatively. Early recognition of variability of patient’s pain perception and differences in responses to pain need to be clearly communicated across the disciplines in a collaborative model of care.

Children with medical complexity and/or cognitive, emotional, or behavioral impairments may benefit from preoperative psychosocial treatments and utilization of pain self-management training and strategies that could further reduce anxiety and optimize postoperative care because patient and parental preoperative anxiety may be associated with adverse outcomes. Validated pain assessment tools like Revised FLACC (Face, Leg, Activity, Cry, and Consolability) Scale and Individualized Numeric Rating Scale could be particularly useful in children with limitations in communication or altered pain perception; therefore, medical teams and family members should discuss their utilization preoperatively.

MULTIMODAL ANALGESIA

Multimodal analgesia (MMA) is a strategy that synergistically uses pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic modalities to target pain at multiple points of the pain processing pathway (Table).6 MMA can optimize pain control by addressing different types of pain (eg, incisional pain, muscle spasm, or neuropathic pain), expedite recovery, reduce potential pharmacologic side effects, and decrease opioid consumption. Patients taking opioids are at an increased risk of developing opioid-related side effects such as respiratory depression, medication tolerance, and anxiety, with resultant longer hospital stay, increased readmissions, and higher costs of care.7 Treatment for postoperative pain should prioritize appropriately dosed and precisely scheduled MMA before opioid-focused analgesia with the goals of decreasing opioid-related adverse effects, intentional misuse, diversion, and accidental ingestions. The AAP, APS, CDC, and SHM endorse the use of MMA and recommend nonpharmacologic measures and regional anesthesia.8,9 The most used modalities in MMA are discussed below.

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen has central-acting analgesic and antipyretic properties and readily crosses the blood brain barrier, which makes it particularly useful in spine and neurological surgeries. Oral administration is preferred when feasible. The AAP recommends refraining from rectal administration of acetaminophen as analgesia in children because of concerns about toxic effects and erratic, variable absorption.10 A systematic review of six studies found no benefit in pain control between intravenous (IV) and oral (PO) administration of acetaminophen in adults.11 There is a paucity of studies in children comparing PO with IV acetaminophen perioperative efficacy. Children may benefit from IV formulations in the early postoperative period, in cases with frequent nausea and vomiting, and in those with oral medication intolerance. Since infants have greater risk of respiratory depression from opioids, IV acetaminophen may have utility in this age group. Because of the cost associated with IV formulation, some institutions restrict IV acetaminophen. However, rapidly well-controlled pain and minimization of opioid-related side effects with shorter hospital stays may lower healthcare costs despite the cost of acetaminophen itself.

NSAIDs

NSAIDs possess anti-inflammatory properties through the inhibition of cyclooxygenase and blockade of prostaglandin production. NSAID risks include bleeding, renal and gastrointestinal toxicities, and potentially delayed wound and bone healing. Ketorolac is an NSAID that continues to be widely used with demonstrated opioid-sparing effects. Many retrospective studies including large numbers of pediatric patients have not demonstrated increased risks of bleeding nor poor wound healing with short postoperative use. A Cochrane review, however, concluded that there is insufficient data to either support or reject the efficacy or safety of ketorolac for postoperative pain treatment in children, mostly because of the very low quality of evidence.12

Regional Anesthesia

Regional anesthesia, which includes central (spinal/epidural/caudal) and peripheral blocks, decreases postoperative pain and opioid-associated side effects. Blocks typically consist of local anesthetic with or without the addition of adjuncts (eg, clonidine, dexamethasone). Regional anesthesia may also improve pulmonary function, compared with that of nonregional MMA use, in patients who have thoracic or upper abdominal surgeries. While having broad applications, the utility of regional anesthesia is greatest in preterm infants/neonates and in those with underlying respiratory pathology. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials demonstrated that regional anesthesia decreased opioid consumption and minimized postoperative pain with no significant complications attributed to its use.13 Additional studies are needed to better delineate specific surgical procedures and subpopulations of pediatric patients in which regional anesthesia may provide the most benefit.

Gabapentinoids

Children receiving gabapentinoids perioperatively have been shown to have fewer adverse reactions, decreased opioid consumption, and less anxiety, as well as improved pain scores. Gabapentin is increasingly being utilized for children with idiopathic scoliosis undergoing posterior spinal fusion, and there is some evidence for improving pain control and reducing opioid use. However, a recent systematic review found a paucity of data supporting its clinical use.14 Both gabapentin and pregabalin may further increase risks of respiratory depression, especially in synergy with opioids and benzodiazepines.

Opioids

Opioids should be used with caution in pediatric patients and are reserved primarily for the management of severe acute pain. The shortest duration of the lowest effective dose of opioids should be encouraged. Patient-controlled opioid analgesia (PCA) offers benefits when parenteral postoperative analgesia is indicated: It maximizes pain relief, minimizes risk of overdose, and improves psychological well-being through self-administration of pain medicines. Basal-infusion PCA should not be routinely used because it is associated with nausea, vomiting, and respiratory depression without having superior analgesia compared with demand use only. Monitoring of side stream end-tidal capnography can readily detect respiratory depression, especially if opioids, benzodiazepines, gabapentinoids, and diphenhydramine are used concomitantly. Patient education regarding opioid use, side effects, safe storage, and disposal practices is imperative because significant amounts of opioids remain in households after completion of treatment for pain and because opioid diversion and accidental ingestions account for significant morbidity. Providers need to balance efficient pain management with opioid stewardship, complying with state and federal policies to limit harm related to opioid diversion.15

Nonpharmacological Modalities

The use of nonpharmacologic therapies, along with pharmacologic modalities, for perioperative pain management has been shown to decrease opioid use and opioid-related side effects. Trials of acupressure have demonstrated improvement in nausea and vomiting, sleep quality, and pain and anxiety scores. Nonpharmacologic treatments currently serve as a complementary approach for pain and anxiety management in the perioperative setting including acupuncture, acupressure, osteopathic manipulative treatment, massage, meditation, biofeedback, hypnotherapy, and physical/occupational, relaxation, cognitive-behavioral, chiropractic, music, and art therapies. The Joint Commission suggests consideration of such modalities by hospitals.

FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS

Pediatric hospitalists have been traditionally involved in research and patient care improvements and should continue to actively contribute to establishing evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of acute postoperative pain in hospitalized children and adolescents. The sparsity of high-quality evidence prompts the need for more research. A standardized approach to perioperative pain management in the form of checklists, pathways, and protocols for specific procedures may be useful to educate providers and patients, while also standardizing available evidence-based interventions (eg, pediatric Enhanced Recovery After Surgery [ERAS] protocols).

CONCLUSION

Combining multimodal pharmacologic and integrative nonpharmacologic modalities can decrease opioid use and related side effects and improve the perioperative care of hospitalized children. Pediatric hospitalists have an opportunity to optimize care preoperatively, practice multimodal analgesia, and contribute to reducing risk of opioid diversion post operatively.

1. Society of Hospital Medicine Co-Management Advisory Panel. A white paper on a guide to hospitalist/orthopedic surgery co-management. http://tools.hospitalmedicine.org/Implementation/Co-ManagementWhitePaper-final_5-10-10.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2019.

2. Rappaport DI, Rosenberg RE, Shaughnessy EE, et al. Pediatric hospitalist comanagement of surgical patients: Structural, quality, and financial considerations. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(11):737-742. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2266.

3. Evidence-Based Nonpharmacologic Strategies for Comprehensive Pain Care: The Consortium Pain Task Force White Paper. http://www.nonpharmpaincare.org. Accessed on October 11, 2019.

4. Vetter TR, Kain ZN. Role of perioperative surgical home in optimizing the perioperative use of opioids. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(5):1653-1657. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000002280.

5. Edwards DA, Hedrick TL, Jayaram J, et al. American Society for Enhanced Recovery and Perioperative Quality Initiative joint consensus statement on perioperative management of patients on preoperative opioid therapy. Anesth Analg. 2019;129(2):553-566. http://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000004018.

6. Micromedex (electronic version). IBM Watson Health. Greenwood Village, Colorado, USA. https://www.micromedexsolutions.com. Accessed October 10, 2019.

7. Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Management of postoperative pain: A clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain. 2016;17(2):131-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008.

8. Herzig SJ, Mosher HJ, Calcaterra SL, Jena AB, Nuckols TK. Improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: A consensus statement from the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;3(4):263-266. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2980.

9. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain – United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624-1645. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.1464.

10. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs. Acetaminophen toxicity in children. Pediatrics. 2001;108 (4):1020-1024. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.108.4.1020.

11. Jibril F, Sharaby S, Mohamed A, Wilby, KJ. Intravenous versus oral acetaminophen for pain: Systemic review of current evidence to support clinical decision-making. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2015;68(3):238-247. https://doi.org/10.4212/cjhp.v68i3.1458.

12. McNicol ED, Rowe E, Cooper TE. Ketorolac for postoperative pain in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7(7). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012294.pub2.

13. Kendall MC, Castro Alves LJ, Suh EI, McCormick ZL, De Oliveira GS. Regional anesthesia to ameliorate postoperative analgesia outcomes in pediatric surgical patients: an updated systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Local Reg Anesth. 2018;11:91-109. https://doi.org/10.2147/LRA.S185554.

14. Egunsola 0, Wylie CE, Chitty KM, et al. Systematic review of the efficacy and safety of gabapentin and pregabalin for pain in children and adolescents. Anesth Analg. 2019;128(4):811-819. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000003936.

15. Harbaugh C, Gadepalli SK. Pediatric postoperative opioid prescribing and the opioid crisis. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2019;31(3):377-385. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000000768.

1. Society of Hospital Medicine Co-Management Advisory Panel. A white paper on a guide to hospitalist/orthopedic surgery co-management. http://tools.hospitalmedicine.org/Implementation/Co-ManagementWhitePaper-final_5-10-10.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2019.

2. Rappaport DI, Rosenberg RE, Shaughnessy EE, et al. Pediatric hospitalist comanagement of surgical patients: Structural, quality, and financial considerations. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(11):737-742. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2266.

3. Evidence-Based Nonpharmacologic Strategies for Comprehensive Pain Care: The Consortium Pain Task Force White Paper. http://www.nonpharmpaincare.org. Accessed on October 11, 2019.

4. Vetter TR, Kain ZN. Role of perioperative surgical home in optimizing the perioperative use of opioids. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(5):1653-1657. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000002280.

5. Edwards DA, Hedrick TL, Jayaram J, et al. American Society for Enhanced Recovery and Perioperative Quality Initiative joint consensus statement on perioperative management of patients on preoperative opioid therapy. Anesth Analg. 2019;129(2):553-566. http://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000004018.

6. Micromedex (electronic version). IBM Watson Health. Greenwood Village, Colorado, USA. https://www.micromedexsolutions.com. Accessed October 10, 2019.

7. Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Management of postoperative pain: A clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain. 2016;17(2):131-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008.

8. Herzig SJ, Mosher HJ, Calcaterra SL, Jena AB, Nuckols TK. Improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: A consensus statement from the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;3(4):263-266. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2980.

9. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain – United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624-1645. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.1464.

10. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs. Acetaminophen toxicity in children. Pediatrics. 2001;108 (4):1020-1024. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.108.4.1020.

11. Jibril F, Sharaby S, Mohamed A, Wilby, KJ. Intravenous versus oral acetaminophen for pain: Systemic review of current evidence to support clinical decision-making. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2015;68(3):238-247. https://doi.org/10.4212/cjhp.v68i3.1458.

12. McNicol ED, Rowe E, Cooper TE. Ketorolac for postoperative pain in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7(7). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012294.pub2.

13. Kendall MC, Castro Alves LJ, Suh EI, McCormick ZL, De Oliveira GS. Regional anesthesia to ameliorate postoperative analgesia outcomes in pediatric surgical patients: an updated systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Local Reg Anesth. 2018;11:91-109. https://doi.org/10.2147/LRA.S185554.

14. Egunsola 0, Wylie CE, Chitty KM, et al. Systematic review of the efficacy and safety of gabapentin and pregabalin for pain in children and adolescents. Anesth Analg. 2019;128(4):811-819. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000003936.

15. Harbaugh C, Gadepalli SK. Pediatric postoperative opioid prescribing and the opioid crisis. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2019;31(3):377-385. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000000768.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Pediatric Surgical Comanagement

According to the 2012 Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) survey, 94% of adult hospitalists and 74% of pediatric hospitalists provide inpatient care to surgical patients.[1] Many of these programs involve comanagement, which the SHM Comanagement Advisory Panel has described as a system of care featuring shared responsibility, authority, and accountability for hospitalized patients with medical and surgical needs.[2] Collaboration between medical and surgical teams for these patients has occurred commonly at some community institutions for decades, but may only be emerging at some tertiary care hospitals. The trend of comanagement appears to be increasing in popularity in adult medicine.[3] As in adult patients, comanagement for children undergoing surgical procedures, particularly those children with special healthcare needs (CSHCNs), has been proposed as a strategy for improving quality and costs. In this review, we will describe structural, quality, and financial implications of pediatric hospitalist comanagement programs, each of which include both potential benefits and drawbacks, as well as discuss a future research agenda for these programs.

ORGANIZATIONAL NEEDS AND STRUCTURE OF COMANAGEMENT PROGRAMS

Patterns of comanagement likely depend on hospital size and structure, both in adult patients[3] and in pediatrics. Children hospitalized for surgical procedures generally fall into 1 of 2 groups: those who are typically healthy and at low risk for complications, and those who are medically complex and at high risk. Healthy children often undergo high‐prevalence, low‐complexity surgical procedures such as tonsillectomy and hernia repairs;[4] these patients are commonly cared for at community hospitals by adult and pediatric surgeons. Whereas medically complex children also undergo these common procedures, they are more likely to be cared for at tertiary care centers and are also more likely to undergo higher‐complexity surgeries such as spinal fusions, hip osteotomies, and ventriculoperitoneal shunt placements.[4] Hospitalist comanagement programs at community hospitals and tertiary care centers may therefore have evolved differently in response to different needs of patients, providers, and organizations,[5] though some institutions may not fall neatly into 1 of these 2 categories.

Comanagement in Community Hospitals

A significant number of pediatric patients are hospitalized each year in community hospitals.[6] As noted above, children undergoing surgery in these settings are generally healthy, and may be cared for by surgeons with varying amounts of pediatric expertise. In this model, the surgeon may frequently be offsite when not in the operating room, necessitating some type of onsite postoperative coverage. In pediatrics, following adult models, this coverage need may be relatively straightforward: surgeons perform the procedure, followed by a medical team assuming postoperative care with surgical consultation. Because of general surgeons' varying experience with children, the American Academy of Pediatrics suggests that patients younger than 14 years or weighing less than 40 kg cared for by providers without routine pediatric experience should have a pediatric‐trained provider involved in their care,[7] though this suggestion does not mandate comanagement.

For children cared for by adult providers who have little experience with areas of pediatric‐specific care such as medication dosing and assessment of deterioration, we believe that involvement of a pediatric provider may impact care in a number of ways. A pediatric hospitalist's availability on the inpatient unit may allow him or her to better manage routine issues such as pain control and intravenous fluids without surgeon input, improving the efficiency of care. A pediatric hospitalist's general pediatric training may allow him or her to more quickly recognize when a child is medically deteriorating, or when transfer to a tertiary care center may be necessary, making care safer. However, no studies have specifically examined these variables. Future research should measure outcomes such as transfers to higher levels of care, medication errors, length of stay (LOS), and complication rates, especially in community hospital settings.

Comanagement in Tertiary Care Referral Centers

At tertiary care referral centers, surgeries in children are most often performed by pediatric surgeons. In these settings, providing routine hospitalist comanagement to all patients may be neither cost‐effective nor feasible. Adult studies have suggested that population‐targeted models can significantly improve several clinical outcomes. For example, in several studies of patients 65 years and older hospitalized with hip fractures, comanagement with a geriatric hospitalist was associated with improved clinical outcomes and shortened LOS.[8, 9, 10, 11, 12]

An analogous group of pediatric patients to the geriatric population may be CSHCNs or children who are medically complex. Several frameworks have been proposed to identify these patients.[13] Many institutions classify medically complex patients as those with complex chronic medical conditions (CCCs).[13, 14, 15] One framework to identify CSHCNs suggested including not only children with CCCs, but also those with (1) substantial service needs and/or family burden; (2) severe functional limitations; and/or (3) high rates of healthcare system utilization, often requiring the care of several subspecialty providers.[16] As the needs of these patients may be quite diverse, pediatric hospitalists may be involved in many aspects of their care, from preoperative evaluation,[17] to establishing protocols for best practices, to communicating with primary care providers, and even seeing patients in postoperative follow‐up clinics. These patients are known to be at high risk for surgical complications, readmissions,[14] medical errors,[18] lapses in communication, and high care costs. In 1 study, comanagement for children with neuromuscular scoliosis hospitalized for spinal fusion surgery has been associated with shorter LOS and less variability in LOS.[19] However, drawbacks of comanagement programs involving CSHCNs may include difficulty with consistent identification of the population who will most benefit from comanagement and higher initial costs of care.[18]

Models of Comanagement and Comanagement Agreements

A comanagement agreement should address 5 major questions: (1) Who is the primary service? (2) Who is the consulting/comanaging service? (3) Are consults as‐needed or automatic? (4) Who writes orders for the patient? (5) Which staffing model will be used for patient care?[20] Although each question above may be answered differently in different systems, the correct comanagement program is a program that aligns most closely with the patient population and care setting.[11, 20]

Several different models exist for hospitalistsurgeon comanagement programs[20, 21] (Table 1). Under the consultation model (model I), hospitalists become involved in the care of surgical patients only when requested to do so by the surgical team. Criteria for requesting this kind of consultation and the extent of responsibility afforded to the medical team are often not clearly defined, and may differ from hospital to hospital or even surgeon to surgeon.[22] Hospitalist involvement with adult patients with postoperative medical complications, which presumably employed this as‐needed model, has been associated with lower mortality and LOS[23]; whether this involvement provides similar benefits in children with postoperative complications has not been explicitly studied.

| Model | Attending Service | Consulting Service | Automatic Consultation | Who Writes Orders? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| I | Surgery | Pediatrics | No | Surgery | Similar to traditional consultation |

| II | Surgery | Pediatrics | Yes | Usually surgery | Basic comanagement, consultant may sign off |

| III | Pediatrics | Surgery | Yes | Usually pediatrics | Basic comanagement, consultant may sign off |

| IV | Combined | N/A | N/A | Each service writes own | True comanagement, no sign‐off from either service permitted |

The remaining models involve compulsory participation by both surgical and medical services. In models II and III, patients may be evaluated preoperatively; those felt to meet specific criteria for high medical complexity are either admitted to a medical service with automatic surgical consultation or admitted to a surgical service with automatic medical consultation. In both cases, writing of orders is handled in the same manner as any consultation model; depending on the service agreement, consulting services may sign off or may be required to be involved until discharge. In model IV, care is fully comanaged by medical and surgical services, with each service having ownership over orders pertaining to their discipline. Ethical concerns about such agreements outlined by the American Medical Association include whether all patients cared for under agreements II to IV will truly benefit from the cost of multispecialty care, and whether informed consent from patients themselves should be required given the cost implications.[24]

Comanagement models also vary with respect to frontline provider staffing. Models may incorporate nurse practitioners, hospitalists, physician assistants, or a combination thereof. These providers may assume a variety of roles, including preoperative patient evaluation, direct care of patients while hospitalized, and/or coordination of inpatient and outpatient postoperative care. Staffing requirements for hospitalists and/or mid‐level providers will differ significantly at different institutions based on surgical volume, patient complexity, and other local factors.

COMANAGEMENT AND QUALITY

Comanagement as a Family‐Centered Initiative

Development of a family‐centered culture of care, including care coordination, lies at the core of pediatric hospital medicine, particularly for CSHCNs.[25, 26] In the outpatient setting, family‐centered care has been associated with improved quality of care for CSHCNs.[27, 28] For families of hospitalized children, issues such as involvement in care and timely information transfer have been identified as high priorities.[29] An important tool for addressing these needs is family‐centered rounds (FCRs), which represent multidisciplinary rounds at the bedside involving families and patients as active shared decision makers in conjunction with the medical team.[30, 31] Although FCRs have not been studied in comanagement arrangements specifically, evidence suggests that this tool improves family centeredness and patient safety in nonsurgical patients,[32] and FCRs can likely have a similar impact on postoperative care.

A pediatric hospitalist comanagement program may impact quality and safety of care in a number of other ways. Hospitalists may offer improved access to clinical information for nurses and families, making care safer. One study of comanagement in adult neurosurgical patients found that access to hospitalists led to improved quality and safety of care as perceived by nurses and other members of the care team.[33] A study in pediatric patients found that nurses overwhelmingly supported having hospitalist involvement in complex children undergoing surgery; the same study found that pediatric hospitalists were particularly noted for their communication skills.[34]

Assessing Clinical Outcomes in Pediatric Hospitalist Comanagement Programs

Most studies evaluating the impact of surgical comanagement programs have focused on global metrics such as LOS, overall complication rates, and resource utilization. In adults, results of these studies have been mixed, suggesting that patient selection may be an important factor.[35] In pediatrics, 2 US studies have assessed these metrics at single centers. Simon et al. found that involvement of a pediatric hospitalist in comanagement of patients undergoing spinal fusion surgery significantly decreased LOS.[19] Rappaport et al. found that patients comanaged by hospitalists had lower utilization of laboratory tests and parenteral nutrition, though initial program costs significantly increased.[36] Studies outside the United States, including a study from Sweden,[37] have suggested that a multidisciplinary approach to children's surgical care, including the presence of pediatric specialists, reduced infection rate and other complications. These studies provide general support for the role of hospitalists in comanagement, although determining which aspects of care are most impacted may be difficult.

Comanagement programs might impact safety and quality negatively as well. Care may be fragmented, leading to provider and family dissatisfaction. Poor communication and multiple handoffs among multidisciplinary team members might interfere with the central role of the nurse in patient care.[38] Comanagement programs might lead to provider disengagement if providers feel that others will assume roles with which they may be unfamiliar or poorly trained.[35] This lack of knowledge may also affect communication with families, leading to conflicting messages among the care team and family frustration. In addition, the impact of comanagement programs on trainees such as residents, both surgical and pediatric, has received limited study.[39] Assessing pediatric comanagement programs' impact on communication, family‐centeredness, and trainees deserves further study.

FINANCIAL IMPLICATIONS OF PEDIATRIC COMANAGEMENT PROGRAMS

Children undergoing surgery require significant financial resources for their care. A study of 38 major US children's hospitals found that 3 of the top 10 conditions with the highest annual expenditures were surgical procedures.[4] The most costly procedure was spinal fusion for scoliosis, accounting for an average of $45,000 per admission and $610 million annually. Although a significant portion of these costs represented surgical devices and operating room time, these totals also included the cost of hospital services and in‐hospital complications. CSHCNs more often undergo high‐complexity procedures such as spinal fusions[36] and face greater risk for costly postoperative complications. The financial benefits that come from reductions in outcomes such as LOS and readmissions in this population are potentially large, but may depend on the payment model as described below.

Billing Models in Comanagement Programs

Several billing constructs exist in comanagement models. At many institutions, comanagement billing may resemble that for traditional consultation: the pediatric hospitalist bills for his/her services using standard initial and subsequent consultation billing coding for the child's medical conditions, and may sign off when the hospitalist feels recommendations are complete. Other models may also exist. Model IV comanagement may involve a prearranged financial agreement, in which billing modifiers are used to differentiate surgical care only (modifier 54) and postoperative medical care only (modifier 55). These modifiers, typically used for Medicare patients, indicate a split in a global surgical fee.[40]

The SHM has outlined financial considerations that should be addressed at the time of program inception and updated periodically, including identifying how each party will bill, who bills for which service, and monitoring collection rates and rejected claims.[2] Regardless of billing model, the main focus of comanagement must be quality of care, not financial considerations; situations in which the latter are emphasized at the expense of patient care may be unethical or illegal.[24] Regardless, surgical comanagement programs should seek maximal reimbursement in order to remain viable.

Value of Comanagement for a Healthcare Organization Under Fee‐for‐Service Payment