User login

Treat-to-Target Outcomes With Tapinarof Cream 1% in Phase 3 Trials for Plaque Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease affecting approximately 8 million adults in the United States and 2% of the global population.1,2 Psoriasis causes pain, itching, and disfigurement and is associated with a physical, psychological, and economic burden that substantially affects health-related quality of life.3-5

Setting treatment goals and treating to target are evidence-based approaches that have been successfully applied to several chronic diseases to improve patient outcomes, including diabetes, hypertension, and rheumatoid arthritis.6-9 Treat-to-target strategies generally set low disease activity (or remission) as an overall goal and seek to achieve this using available therapeutic options as necessary. Introduced following the availability of biologics and targeted systemic therapies, treat-to-target strategies generally provide guidance on expectations of treatment but not specific treatments, as personalized treatment decisions depend on an assessment of individual patients and consider clinical and demographic features as well as preferences for available therapeutic options. If targets are not achieved in the assigned time span, adjustments can be made to the treatment approach in close consultation with the patient. If the target is reached, follow-up visits can be scheduled to ensure improvement is maintained or to establish if more aggressive goals could be selected.

Treat-to-target strategies for the management of psoriasis developed by the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) Medical Board include reducing the extent of psoriasis to 1% or lower total body surface area (BSA) after 3 months of treatment.10 Treatment targets endorsed by the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) in guidelines on the use of systemic therapies in psoriasis include achieving a 75% or greater reduction in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score within 3 to 4 months of treatment.11

In clinical practice, many patients do not achieve these treatment targets, and topical treatments alone generally are insufficient in achieving treatment goals for psoriasis.12,13 Moreover, conventional topical treatments (eg, topical corticosteroids) used by most patients with psoriasis regardless of disease severity are associated with adverse events that can limit their use. Most topical corticosteroids have US Food and Drug Administration label restrictions relating to sites of application, duration and extent of use, and frequency of administration.14,15

Tapinarof cream 1% (VTAMA [Dermavant Sciences, Inc]) is a first-in-class topical nonsteroidal aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist that was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of plaque psoriasis in adults16 and is being studied for the treatment of plaque psoriasis in children 2 years and older as well as for atopic dermatitis in adults and children 2 years and older. In PSOARING 1 (ClinicalTrials .gov identifier NCT03956355) and PSOARING 2 (NCT03983980)—identical 12-week pivotal phase 3 trials—monotherapy with tapinarof cream 1% once daily (QD) demonstrated statistically significant efficacy vs vehicle cream and was well tolerated in adults with mild to severe plaque psoriasis (Supplementary Figure S1).17 Lebwohl et al17 reported that significantly higher PASI75 responses were observed at week 12 with tapinarof cream vs vehicle in PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2 (36% and 48% vs 10% and 7%, respectively; both P<.0001). A significantly higher PASI90 response of 19% and 21% at week 12 also was observed with tapinarof cream vs 2% and 3% with vehicle in PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2, respectively (P=.0005 and P<.0001).17

In PSOARING 3 (NCT04053387)—the long-term extension trial (Supplementary Figure S1)—efficacy continued to improve or was maintained beyond the two 12-week trials, with improvements in total BSA affected and PASI scores for up to 52 weeks.18 Tapinarof cream 1% QD demonstrated positive, rapid, and durable outcomes in PSOARING 3, including high rates of complete disease clearance (Physician Global Assessment [PGA] score=0 [clear])(40.9% [312/763]), durability of response on treatment with no evidence of tachyphylaxis, and a remittive effect of approximately 4 months when off therapy (defined as maintenance of a PGA score of 0 [clear] or 1 [almost clear] after first achieving a PGA score of 0).18

Herein, we report absolute treatment targets for patients with plaque psoriasis who received tapinarof cream 1% QD in the PSOARING trials that are at least as stringent as the corresponding NPF and EADV targets of achieving a total BSA affected of 1% or lower or a PASI75 response within 3 to 4 months, respectively.

METHODS

Study Design

The pooled efficacy analyses included all patients with a baseline PGA score of 2 or higher (mild or worse) before treatment with tapinarof cream 1% QD in the PSOARING trials. This included patients who received tapinarof cream 1% in PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2 who may or may not have continued into PSOARING 3, as well as those who received the vehicle in PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2 who enrolled in PSOARING 3 and had a PGA score of 2 or higher before receiving tapinarof cream 1%.

Trial Participants

Full methods, including inclusion and exclusion criteria, for the PSOARING trials have been previously reported.17,18 Patients were aged 18 to 75 years and had chronic plaque psoriasis that was stable for at least 6 months before randomization; 3% to 20% total BSA affected (excluding the scalp, palms, fingernails, toenails, and soles); and a PGA score of 2 (mild), 3 (moderate), or 4 (severe) at baseline.

The clinical trials were conducted in compliance with the guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was obtained from local ethics committees or institutional review boards at each center. All patients provided written informed consent.

Trial Treatment

In PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2, patients were randomized (2:1) to receive tapinarof cream 1% or vehicle QD for 12 weeks. In PSOARING 3 (the long-term extension trial), patients received up to 40 weeks of open-label tapinarof, followed by 4 weeks of follow-up off treatment. Patients received intermittent or continuous treatment with tapinarof cream 1% in PSOARING 3 based on PGA score: those entering the trial with a PGA score of 1 or higher received tapinarof cream 1% until complete disease clearance was achieved (defined as a PGA score of 0 [clear]). Those entering PSOARING 3 with or achieving a PGA score of 0 (clear) discontinued treatment and were observed for the duration of maintenance of a PGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) while off therapy (the protocol-defined “duration of remittive effect”). If disease worsening (defined as a PGA score 2 or higher) occurred, tapinarof cream 1% was restarted and continued until a PGA score of 0 (clear) was achieved. This pattern of treatment, discontinuation on achieving a PGA score of 0 (clear), and retreatment on disease worsening continued until the end of the trial. As a result, patients in PSOARING 3 could receive tapinarof cream 1% continuously or intermittently for 40 weeks.

Outcome Measures and Statistical Analyses

The assessment of total BSA affected by plaque psoriasis is an estimate of the total extent of disease as a percentage of total skin area. In the PSOARING trials, the skin surface of one hand (palm and digits) was assumed to be approximately equivalent to 1% BSA. The total BSA affected by psoriasis was evaluated from 0% to 100%, with greater total BSA affected being an indication of more extensive disease. The BSA efficacy outcomes used in these analyses were based post hoc on the proportion of patients who achieved a 1% or lower or 0.5% or lower total BSA affected.

Psoriasis Area and Severity Index scores assess both the severity and extent of psoriasis. A PASI score lower than 5 often is considered indicative of mild psoriasis, a score of 5 to 10 indicates moderate disease, and a score higher than 10 indicates severe disease.19 The maximum PASI score is 72. The PASI efficacy outcomes used in these analyses were based post hoc on the proportion of patients who achieved an absolute total PASI score of 3 or lower, 2 or lower, and 1 or lower.

Efficacy analyses were based on pooled data for all patients in the PSOARING trials who had a PGA score of 2 to 4 (mild to severe) before treatment with tapinarof cream 1% in the intention-to-treat population using observed cases. Time-to-target analyses were based on Kaplan-Meier (KM) estimates using observed cases.

Safety analyses included the incidence and frequency of adverse events and were based on all patients who received tapinarof cream 1% in the PSOARING trials.

RESULTS

Baseline Patient Demographics and Disease Characteristics

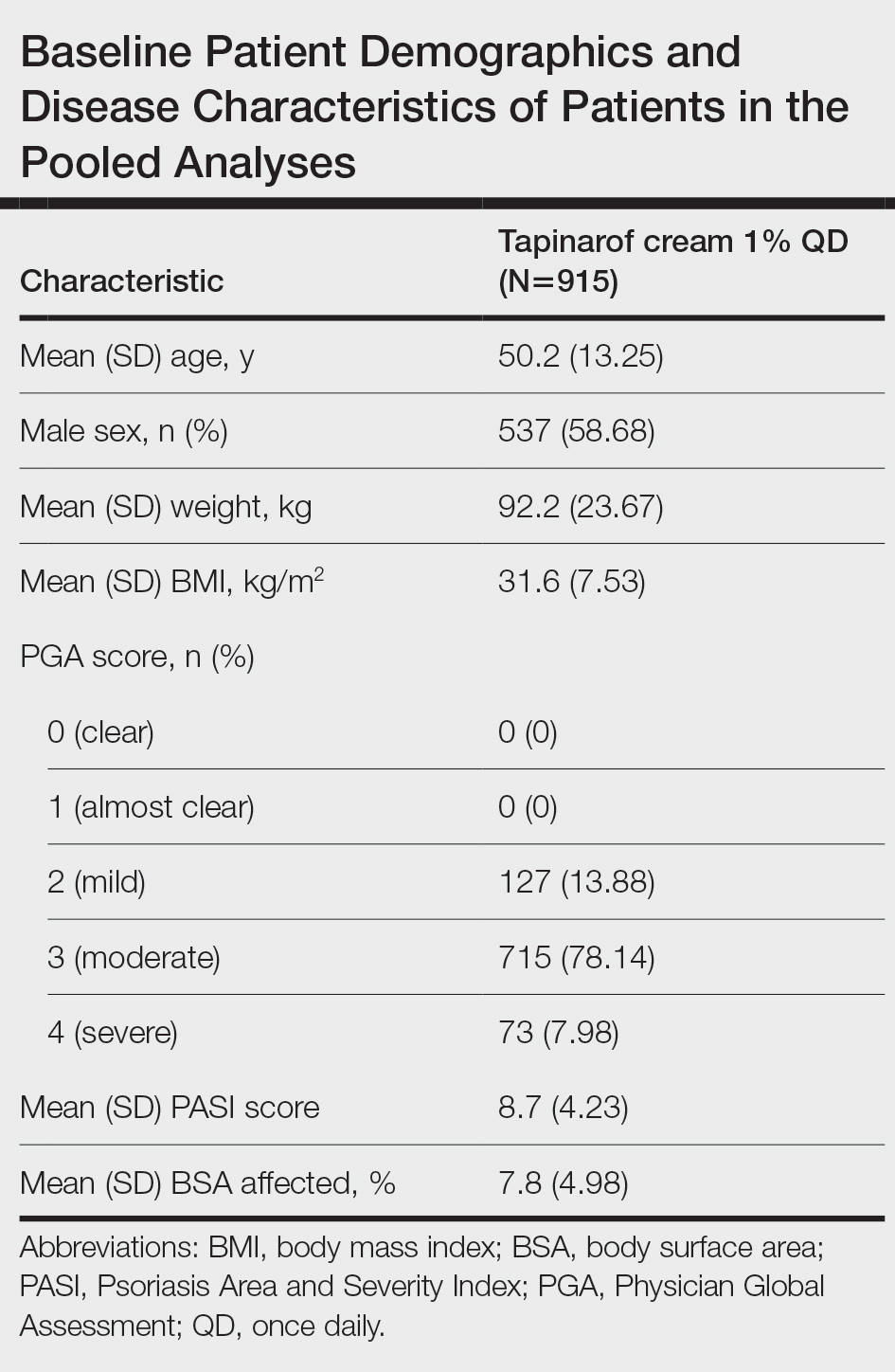

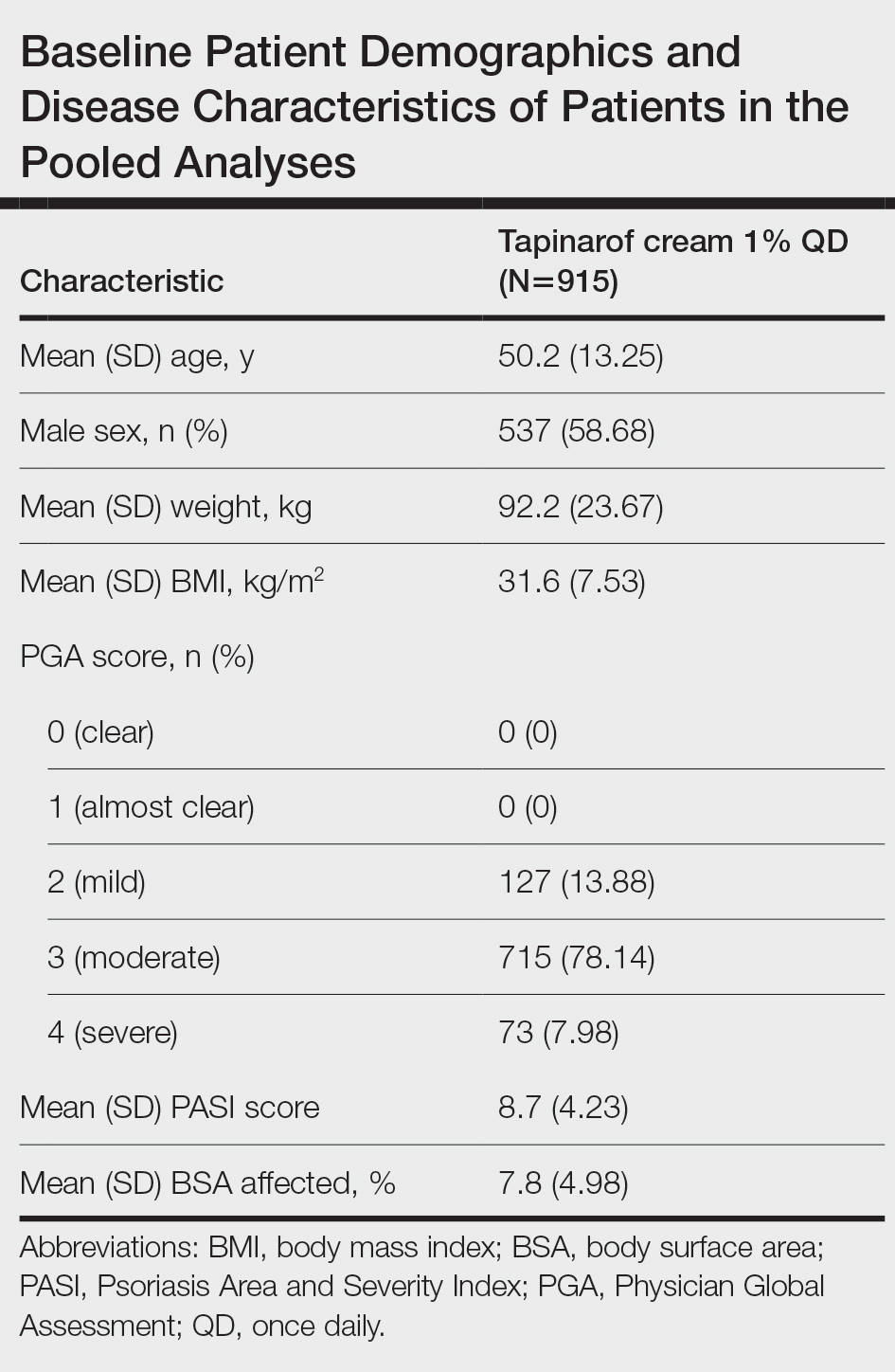

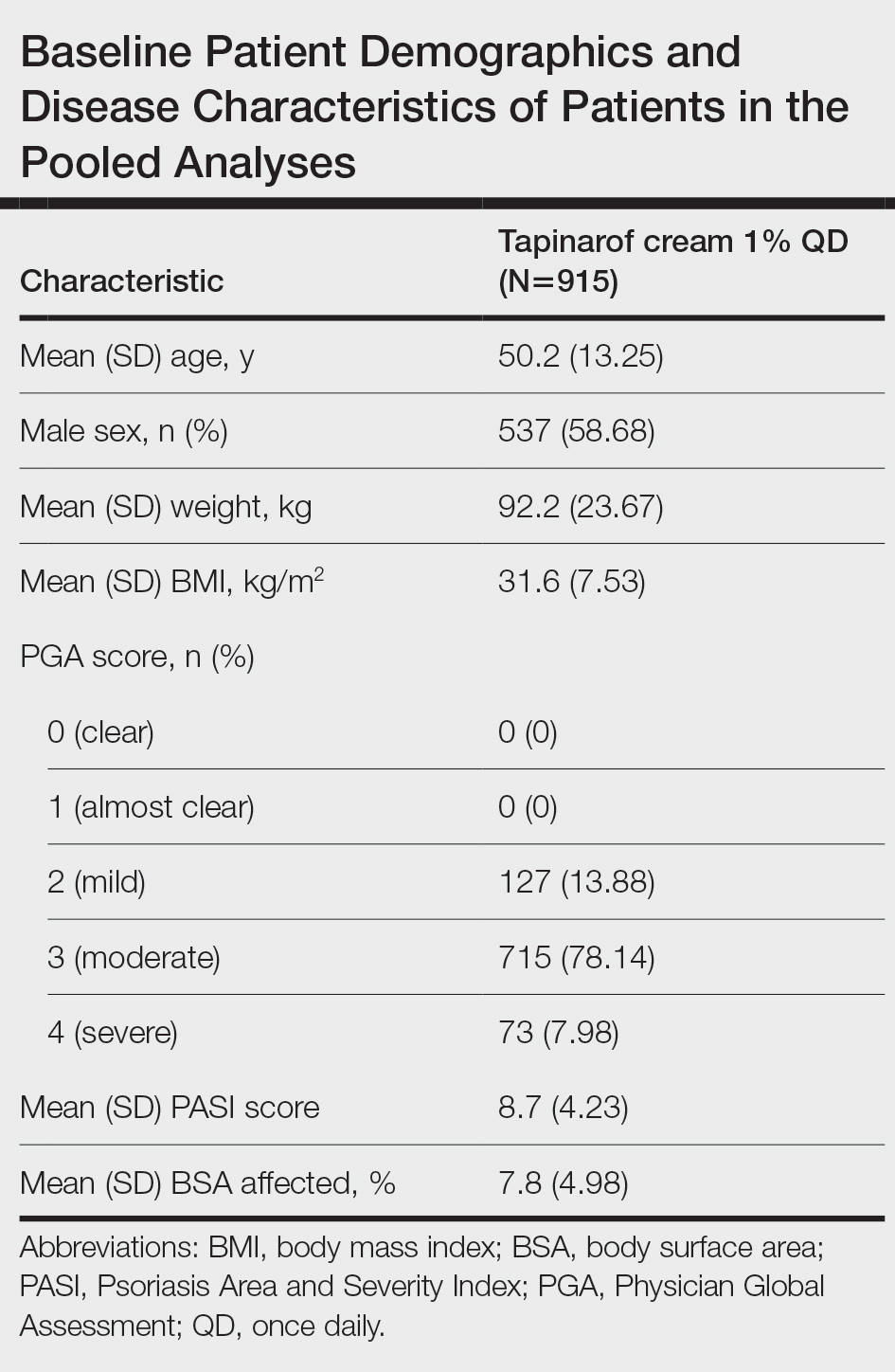

The pooled efficacy analyses included 915 eligible patients (Table). At baseline, the mean (SD) age was 50.2 (13.25) years, 58.7% were male, the mean (SD) weight was 92.2 (23.67) kg, and the mean (SD) body mass index was 31.6 (7.53) kg/m2. The percentage of patients with a PGA score of 2 (mild), 3 (moderate), or 4 (severe) was 13.9%, 78.1%, and 8.0%, respectively. The mean (SD) PASI score was 8.7 (4.23) and mean (SD) total BSA affected was 7.8% (4.98).

Efficacy

Achievement of BSA-Affected Targets—

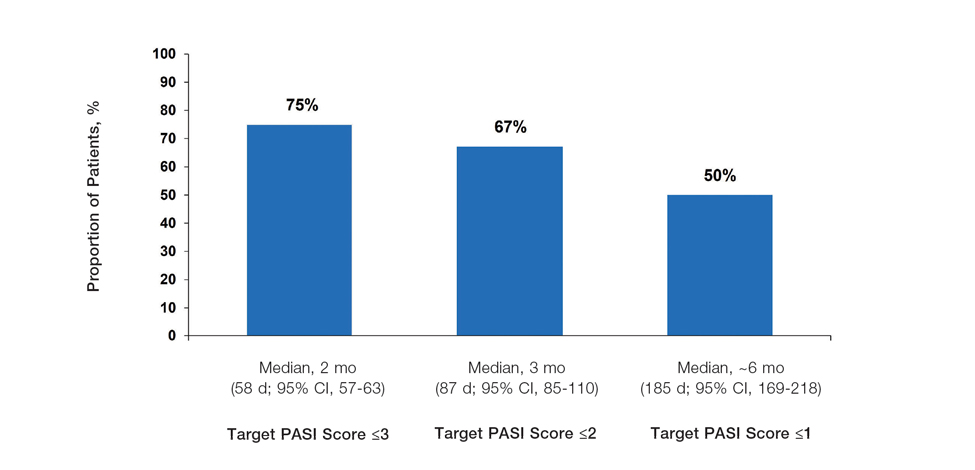

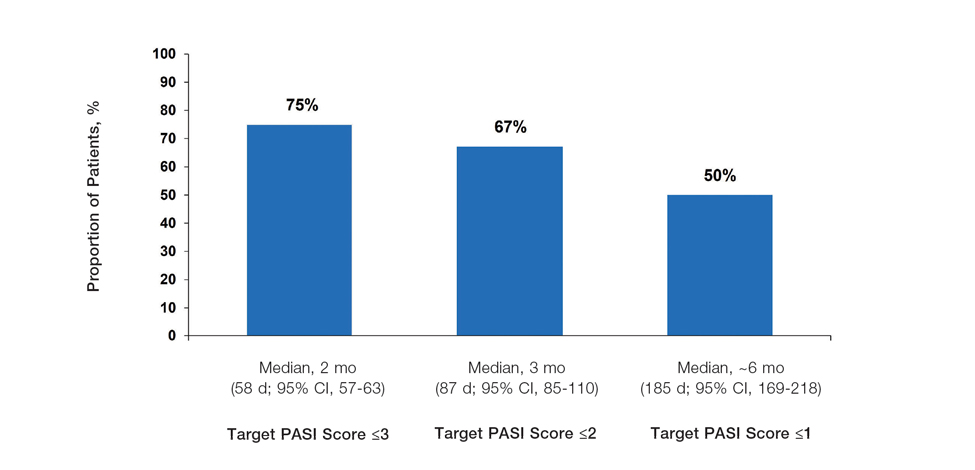

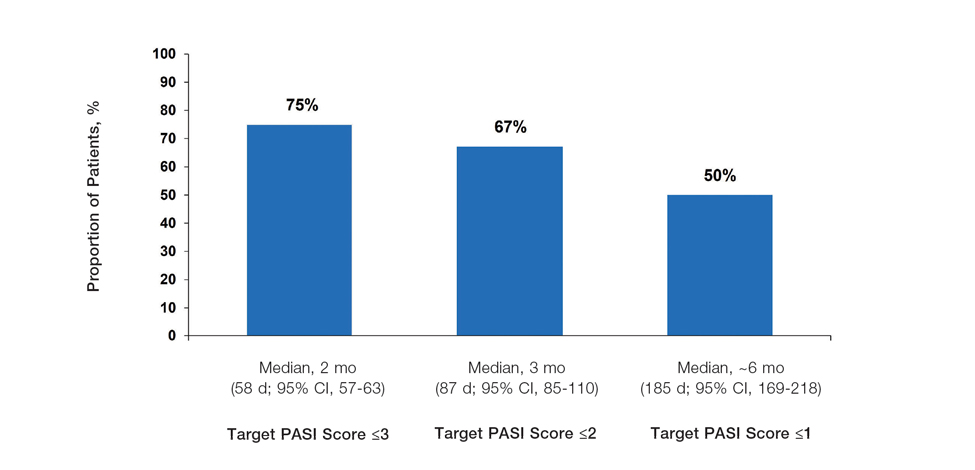

Achievement of Absolute PASI Targets—Across the total trial period (up to 52 weeks), an absolute total PASI score of 3 or lower was achieved by 75% of patients (686/915), with a median time to achieve this of 2 months (KM estimate: 58 days [95% CI, 57-63]); approximately 67% of patients (612/915) achieved a total PASI score of 2 or lower, with a median time to achieve of 3 months (KM estimate: 87 days [95% CI, 85-110])(Figure 2; Supplementary Figures S3a and S3b). A PASI score of 1 or lower was achieved by approximately 50% of patients (460/915), with a median time to achieve of approximately 6 months (KM estimate: 185 days [95% CI, 169-218])(Figure 2, Supplementary Figure S3c).

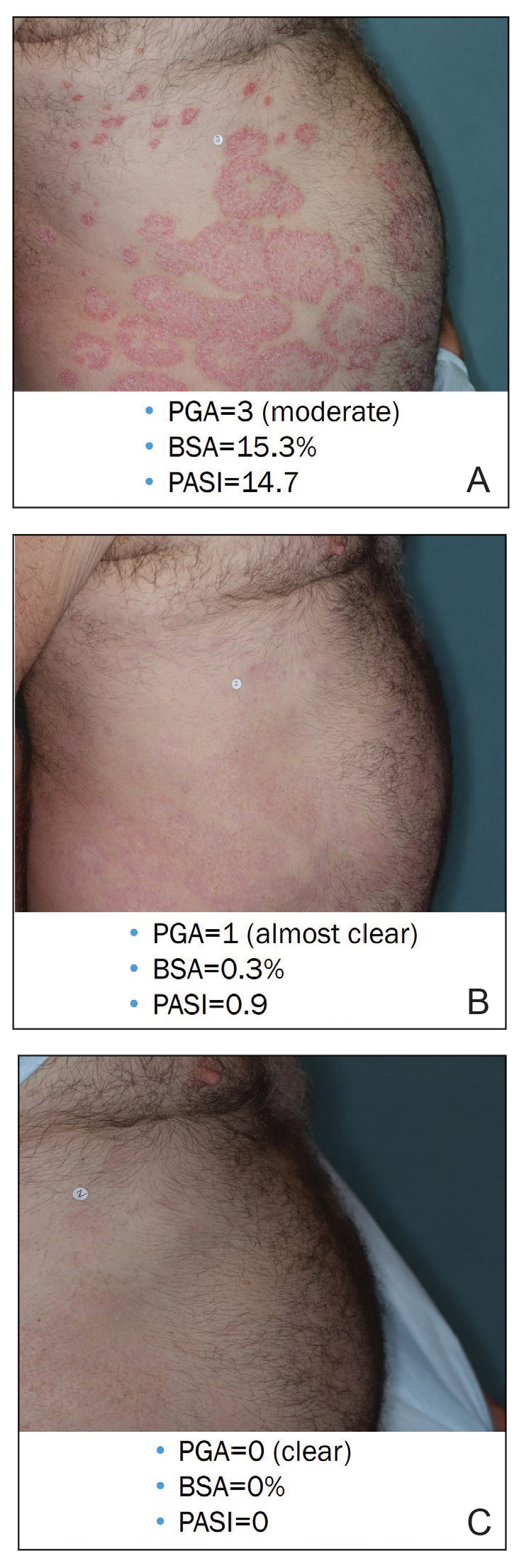

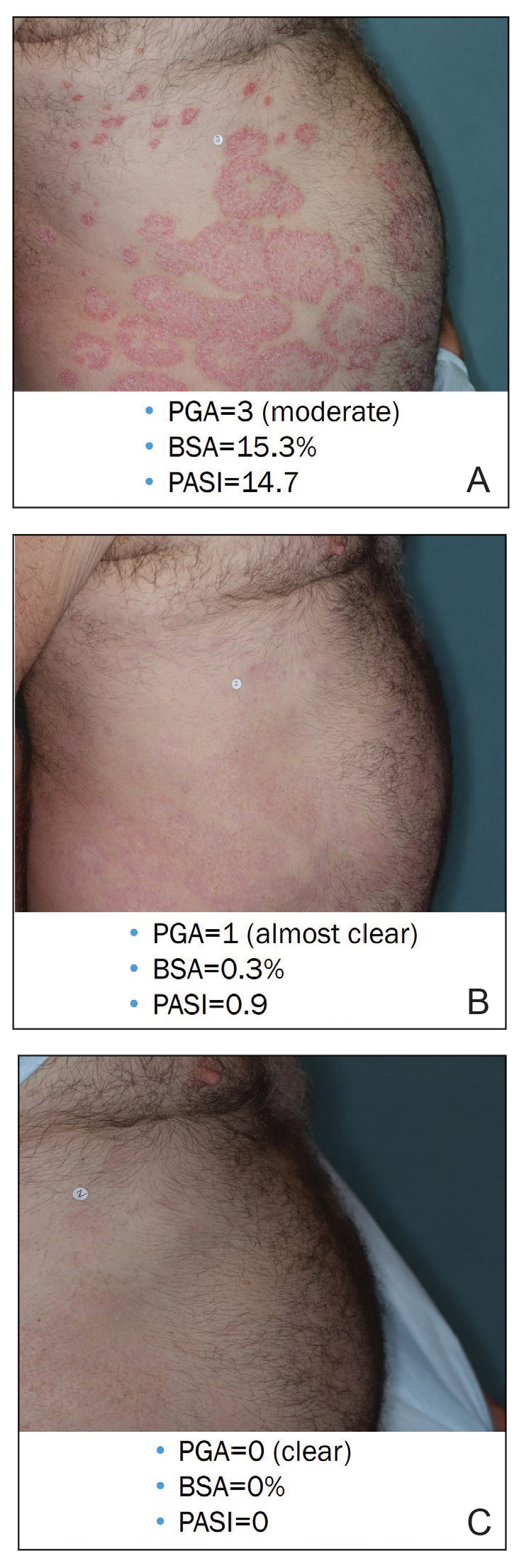

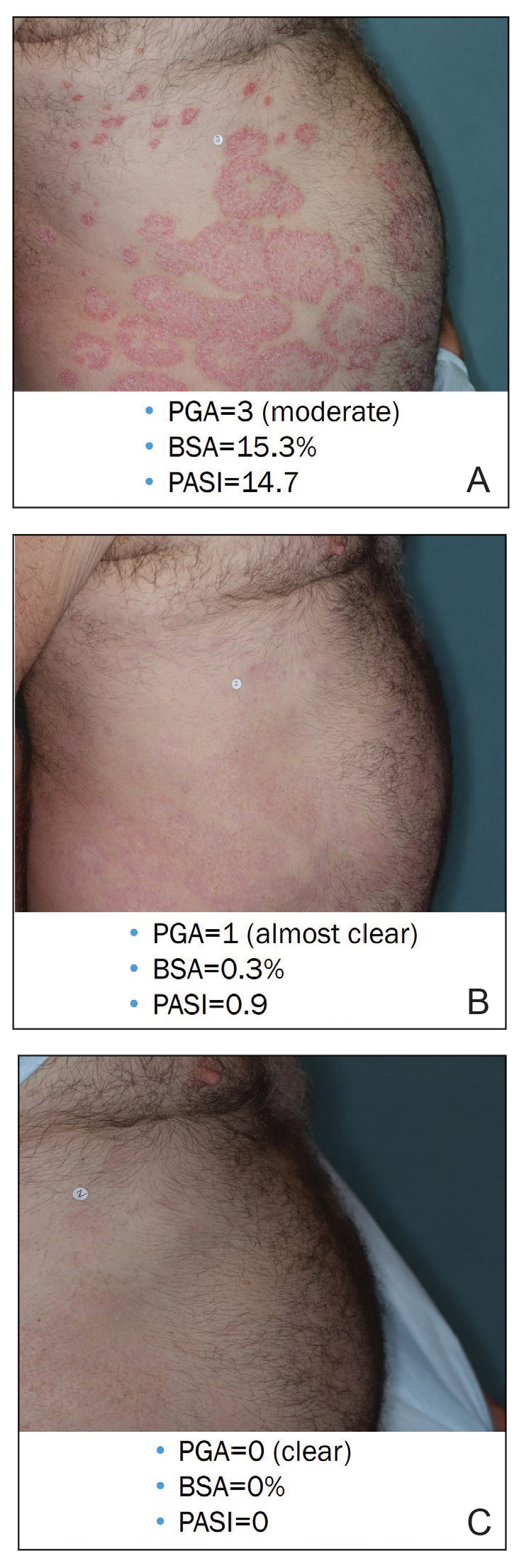

Illustrative Case—Case photography showing the clinical response in a 63-year-old man with moderate plaque psoriasis in PSOARING 2 is shown in Figure 3. After 12 weeks of treatment with tapinarof cream 1% QD, the patient achieved all primary and secondary efficacy end points. In addition to achieving the regulatory end point of a PGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) and a decrease from baseline of at least 2 points, achievement of 0% total BSA affected and a total PASI score of 0 at week 12 exceeded the NPF and EADV consensus treatment targets.10,11 Targets were achieved as early as week 4, with a total BSA affected of 0.5% or lower and a total PASI score of 1 or lower, illustrated by marked skin clearing and only faint residual erythema that completely resolved at week 12, with the absence of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Safety

Safety data for the PSOARING trials have been previously reported.17,18 The most common treatment-emergent adverse events were folliculitis, contact dermatitis, upper respiratory tract infection, and nasopharyngitis. Treatment-emergent adverse events generally were mild or moderate in severity and did not lead to trial discontinuation.17,18

COMMENT

Treat-to-target management approaches aim to improve patient outcomes by striving to achieve optimal goals. The treat-to-target approach supports shared decision-making between clinicians and patients based on common expectations of what constitutes treatment success.

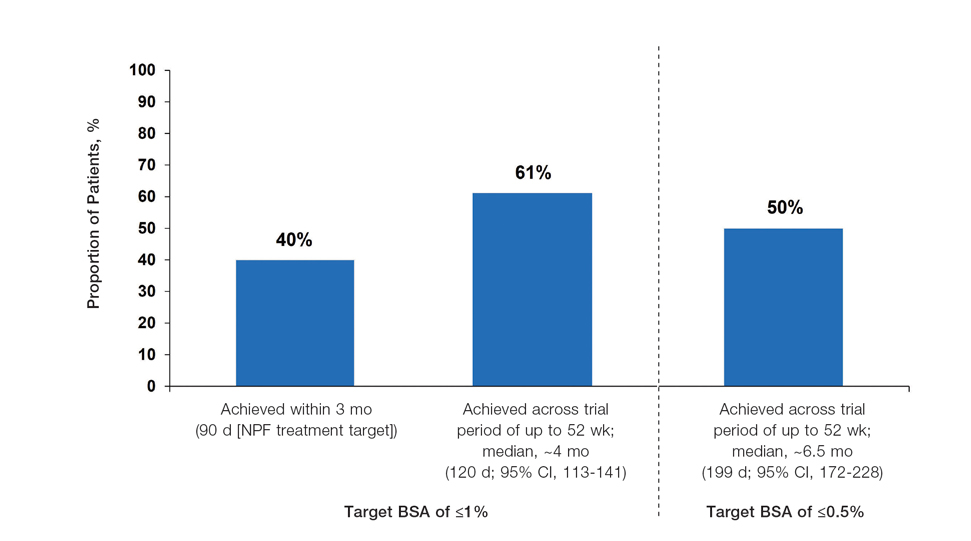

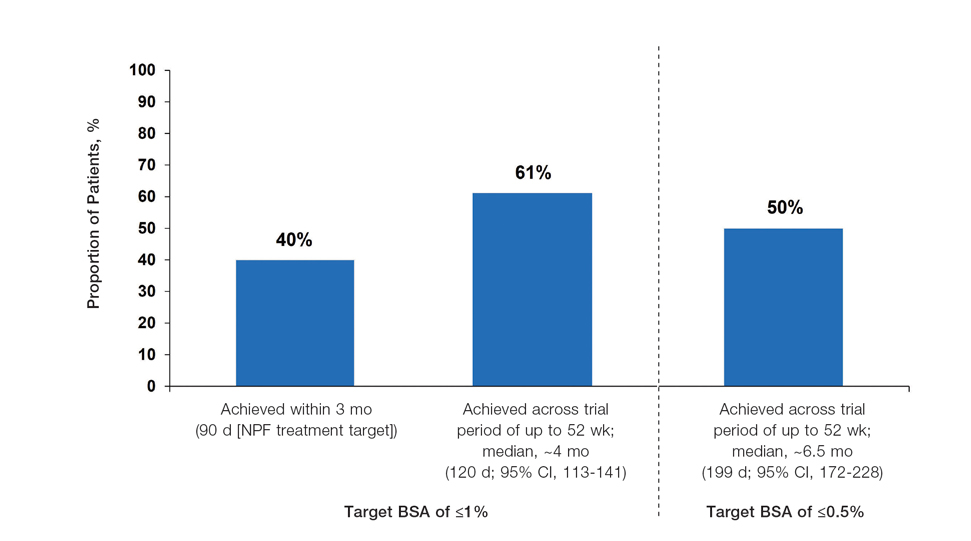

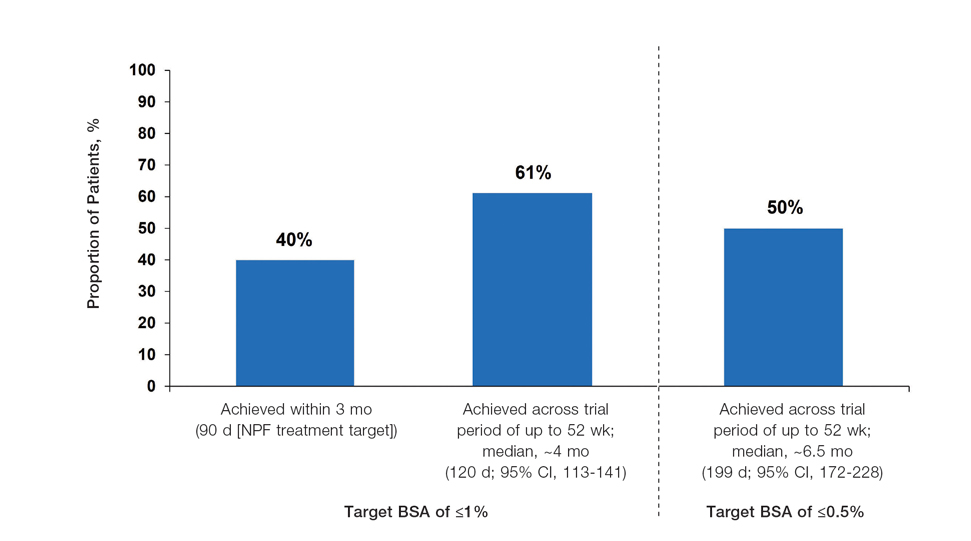

The findings of this analysis based on pooled data from a large cohort of patients demonstrate that a high proportion of patients can achieve or exceed recommended treatment targets with tapinarof cream 1% QD and maintain improvements long-term. The NPF-recommended treatment target of 1% or lower BSA affected within approximately 3 months (90 days) of treatment was achieved by 40% of tapinarof-treated patients. In addition, 1% or lower BSA affected at any time during the trials was achieved by 61% of patients (median, approximately 4 months). The analyses also indicated that PASI total scores of 3 or lower and 2 or lower were achieved by 75% and 67% of tapinarof-treated patients, respectively, within 2 to 3 months.

These findings support the previously reported efficacy of tapinarof cream, including high rates of complete disease clearance (40.9% [312/763]), durable response following treatment interruption, an off-therapy remittive effect of approximately 4 months, and good disease control on therapy with no evidence of tachyphylaxis.17,18

CONCLUSION

Taken together with previously reported tapinarof efficacy and safety results, our findings demonstrate that a high proportion of patients treated with tapinarof cream as monotherapy can achieve aggressive treatment targets set by both US and European guidelines developed for systemic and biologic therapies. Tapinarof cream 1% QD is an effective topical treatment option for patients with plaque psoriasis that has been approved without restrictions relating to severity or extent of disease treated, duration of use, or application sites, including application to sensitive and intertriginous skin.

Acknowledgments—Editorial and medical writing support under the guidance of the authors was provided by Melanie Govender, MSc (Med), ApotheCom (United Kingdom), and was funded by Dermavant Sciences, Inc, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP) guidelines.

- Armstrong AW, Mehta MD, Schupp CW, et al. Psoriasis prevalence in adults in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:940-946.

- Parisi R, Iskandar IYK, Kontopantelis E, et al. National, regional, and worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis: systematic analysis and modelling study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1590.

- Pilon D, Teeple A, Zhdanava M, et al. The economic burden of psoriasis with high comorbidity among privately insured patients in the United States. J Med Econ. 2019;22:196-203.

- Singh S, Taylor C, Kornmehl H, et al. Psoriasis and suicidality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:425-440.e2.

- Feldman SR, Goffe B, Rice G, et al. The challenge of managing psoriasis: unmet medical needs and stakeholder perspectives. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2016;9:504-513.

- Ford JA, Solomon DH. Challenges in implementing treat-to-target strategies in rheumatology. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2019;45:101-112.

- Sitbon O, Galiè N. Treat-to-target strategies in pulmonary arterial hypertension: the importance of using multiple goals. Eur Respir Rev. 2010;19:272-278.

- Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:631-637.

- Wangnoo SK, Sethi B, Sahay RK, et al. Treat-to-target trials in diabetes. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;18:166-174.

- Armstrong AW, Siegel MP, Bagel J, et al. From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: treatment targets for plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:290-298.

- Pathirana D, Ormerod AD, Saiag P, et al. European S3-guidelines on the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(Suppl 2):1-70.

- Strober BE, van der Walt JM, Armstrong AW, et al. Clinical goals and barriers to effective psoriasis care. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2019; 9:5-18.

- Bagel J, Gold LS. Combining topical psoriasis treatment to enhance systemic and phototherapy: a review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1209-1222.

- Elmets CA, Korman NJ, Prater EF, et al. Joint AAD-NPF Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapy and alternative medicine modalities for psoriasis severity measures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:432-470.

- Stein Gold LF. Topical therapies for psoriasis: improving management strategies and patient adherence. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2016;35 (2 Suppl 2):S36-S44; quiz S45.

- VTAMA® (tapinarof) cream. Prescribing information. Dermavant Sciences; 2022. Accessed September 13, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/215272s000lbl.pdf

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229 and supplementary appendix.

- Strober B, Stein Gold L, Bissonnette R, et al. One-year safety and efficacy of tapinarof cream for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: results from the PSOARING 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:800-806.

- Clinical Review Report: Guselkumab (Tremfya) [Internet]. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2018. Accessed September 13, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534047/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK534047.pdf

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease affecting approximately 8 million adults in the United States and 2% of the global population.1,2 Psoriasis causes pain, itching, and disfigurement and is associated with a physical, psychological, and economic burden that substantially affects health-related quality of life.3-5

Setting treatment goals and treating to target are evidence-based approaches that have been successfully applied to several chronic diseases to improve patient outcomes, including diabetes, hypertension, and rheumatoid arthritis.6-9 Treat-to-target strategies generally set low disease activity (or remission) as an overall goal and seek to achieve this using available therapeutic options as necessary. Introduced following the availability of biologics and targeted systemic therapies, treat-to-target strategies generally provide guidance on expectations of treatment but not specific treatments, as personalized treatment decisions depend on an assessment of individual patients and consider clinical and demographic features as well as preferences for available therapeutic options. If targets are not achieved in the assigned time span, adjustments can be made to the treatment approach in close consultation with the patient. If the target is reached, follow-up visits can be scheduled to ensure improvement is maintained or to establish if more aggressive goals could be selected.

Treat-to-target strategies for the management of psoriasis developed by the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) Medical Board include reducing the extent of psoriasis to 1% or lower total body surface area (BSA) after 3 months of treatment.10 Treatment targets endorsed by the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) in guidelines on the use of systemic therapies in psoriasis include achieving a 75% or greater reduction in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score within 3 to 4 months of treatment.11

In clinical practice, many patients do not achieve these treatment targets, and topical treatments alone generally are insufficient in achieving treatment goals for psoriasis.12,13 Moreover, conventional topical treatments (eg, topical corticosteroids) used by most patients with psoriasis regardless of disease severity are associated with adverse events that can limit their use. Most topical corticosteroids have US Food and Drug Administration label restrictions relating to sites of application, duration and extent of use, and frequency of administration.14,15

Tapinarof cream 1% (VTAMA [Dermavant Sciences, Inc]) is a first-in-class topical nonsteroidal aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist that was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of plaque psoriasis in adults16 and is being studied for the treatment of plaque psoriasis in children 2 years and older as well as for atopic dermatitis in adults and children 2 years and older. In PSOARING 1 (ClinicalTrials .gov identifier NCT03956355) and PSOARING 2 (NCT03983980)—identical 12-week pivotal phase 3 trials—monotherapy with tapinarof cream 1% once daily (QD) demonstrated statistically significant efficacy vs vehicle cream and was well tolerated in adults with mild to severe plaque psoriasis (Supplementary Figure S1).17 Lebwohl et al17 reported that significantly higher PASI75 responses were observed at week 12 with tapinarof cream vs vehicle in PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2 (36% and 48% vs 10% and 7%, respectively; both P<.0001). A significantly higher PASI90 response of 19% and 21% at week 12 also was observed with tapinarof cream vs 2% and 3% with vehicle in PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2, respectively (P=.0005 and P<.0001).17

In PSOARING 3 (NCT04053387)—the long-term extension trial (Supplementary Figure S1)—efficacy continued to improve or was maintained beyond the two 12-week trials, with improvements in total BSA affected and PASI scores for up to 52 weeks.18 Tapinarof cream 1% QD demonstrated positive, rapid, and durable outcomes in PSOARING 3, including high rates of complete disease clearance (Physician Global Assessment [PGA] score=0 [clear])(40.9% [312/763]), durability of response on treatment with no evidence of tachyphylaxis, and a remittive effect of approximately 4 months when off therapy (defined as maintenance of a PGA score of 0 [clear] or 1 [almost clear] after first achieving a PGA score of 0).18

Herein, we report absolute treatment targets for patients with plaque psoriasis who received tapinarof cream 1% QD in the PSOARING trials that are at least as stringent as the corresponding NPF and EADV targets of achieving a total BSA affected of 1% or lower or a PASI75 response within 3 to 4 months, respectively.

METHODS

Study Design

The pooled efficacy analyses included all patients with a baseline PGA score of 2 or higher (mild or worse) before treatment with tapinarof cream 1% QD in the PSOARING trials. This included patients who received tapinarof cream 1% in PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2 who may or may not have continued into PSOARING 3, as well as those who received the vehicle in PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2 who enrolled in PSOARING 3 and had a PGA score of 2 or higher before receiving tapinarof cream 1%.

Trial Participants

Full methods, including inclusion and exclusion criteria, for the PSOARING trials have been previously reported.17,18 Patients were aged 18 to 75 years and had chronic plaque psoriasis that was stable for at least 6 months before randomization; 3% to 20% total BSA affected (excluding the scalp, palms, fingernails, toenails, and soles); and a PGA score of 2 (mild), 3 (moderate), or 4 (severe) at baseline.

The clinical trials were conducted in compliance with the guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was obtained from local ethics committees or institutional review boards at each center. All patients provided written informed consent.

Trial Treatment

In PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2, patients were randomized (2:1) to receive tapinarof cream 1% or vehicle QD for 12 weeks. In PSOARING 3 (the long-term extension trial), patients received up to 40 weeks of open-label tapinarof, followed by 4 weeks of follow-up off treatment. Patients received intermittent or continuous treatment with tapinarof cream 1% in PSOARING 3 based on PGA score: those entering the trial with a PGA score of 1 or higher received tapinarof cream 1% until complete disease clearance was achieved (defined as a PGA score of 0 [clear]). Those entering PSOARING 3 with or achieving a PGA score of 0 (clear) discontinued treatment and were observed for the duration of maintenance of a PGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) while off therapy (the protocol-defined “duration of remittive effect”). If disease worsening (defined as a PGA score 2 or higher) occurred, tapinarof cream 1% was restarted and continued until a PGA score of 0 (clear) was achieved. This pattern of treatment, discontinuation on achieving a PGA score of 0 (clear), and retreatment on disease worsening continued until the end of the trial. As a result, patients in PSOARING 3 could receive tapinarof cream 1% continuously or intermittently for 40 weeks.

Outcome Measures and Statistical Analyses

The assessment of total BSA affected by plaque psoriasis is an estimate of the total extent of disease as a percentage of total skin area. In the PSOARING trials, the skin surface of one hand (palm and digits) was assumed to be approximately equivalent to 1% BSA. The total BSA affected by psoriasis was evaluated from 0% to 100%, with greater total BSA affected being an indication of more extensive disease. The BSA efficacy outcomes used in these analyses were based post hoc on the proportion of patients who achieved a 1% or lower or 0.5% or lower total BSA affected.

Psoriasis Area and Severity Index scores assess both the severity and extent of psoriasis. A PASI score lower than 5 often is considered indicative of mild psoriasis, a score of 5 to 10 indicates moderate disease, and a score higher than 10 indicates severe disease.19 The maximum PASI score is 72. The PASI efficacy outcomes used in these analyses were based post hoc on the proportion of patients who achieved an absolute total PASI score of 3 or lower, 2 or lower, and 1 or lower.

Efficacy analyses were based on pooled data for all patients in the PSOARING trials who had a PGA score of 2 to 4 (mild to severe) before treatment with tapinarof cream 1% in the intention-to-treat population using observed cases. Time-to-target analyses were based on Kaplan-Meier (KM) estimates using observed cases.

Safety analyses included the incidence and frequency of adverse events and were based on all patients who received tapinarof cream 1% in the PSOARING trials.

RESULTS

Baseline Patient Demographics and Disease Characteristics

The pooled efficacy analyses included 915 eligible patients (Table). At baseline, the mean (SD) age was 50.2 (13.25) years, 58.7% were male, the mean (SD) weight was 92.2 (23.67) kg, and the mean (SD) body mass index was 31.6 (7.53) kg/m2. The percentage of patients with a PGA score of 2 (mild), 3 (moderate), or 4 (severe) was 13.9%, 78.1%, and 8.0%, respectively. The mean (SD) PASI score was 8.7 (4.23) and mean (SD) total BSA affected was 7.8% (4.98).

Efficacy

Achievement of BSA-Affected Targets—

Achievement of Absolute PASI Targets—Across the total trial period (up to 52 weeks), an absolute total PASI score of 3 or lower was achieved by 75% of patients (686/915), with a median time to achieve this of 2 months (KM estimate: 58 days [95% CI, 57-63]); approximately 67% of patients (612/915) achieved a total PASI score of 2 or lower, with a median time to achieve of 3 months (KM estimate: 87 days [95% CI, 85-110])(Figure 2; Supplementary Figures S3a and S3b). A PASI score of 1 or lower was achieved by approximately 50% of patients (460/915), with a median time to achieve of approximately 6 months (KM estimate: 185 days [95% CI, 169-218])(Figure 2, Supplementary Figure S3c).

Illustrative Case—Case photography showing the clinical response in a 63-year-old man with moderate plaque psoriasis in PSOARING 2 is shown in Figure 3. After 12 weeks of treatment with tapinarof cream 1% QD, the patient achieved all primary and secondary efficacy end points. In addition to achieving the regulatory end point of a PGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) and a decrease from baseline of at least 2 points, achievement of 0% total BSA affected and a total PASI score of 0 at week 12 exceeded the NPF and EADV consensus treatment targets.10,11 Targets were achieved as early as week 4, with a total BSA affected of 0.5% or lower and a total PASI score of 1 or lower, illustrated by marked skin clearing and only faint residual erythema that completely resolved at week 12, with the absence of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Safety

Safety data for the PSOARING trials have been previously reported.17,18 The most common treatment-emergent adverse events were folliculitis, contact dermatitis, upper respiratory tract infection, and nasopharyngitis. Treatment-emergent adverse events generally were mild or moderate in severity and did not lead to trial discontinuation.17,18

COMMENT

Treat-to-target management approaches aim to improve patient outcomes by striving to achieve optimal goals. The treat-to-target approach supports shared decision-making between clinicians and patients based on common expectations of what constitutes treatment success.

The findings of this analysis based on pooled data from a large cohort of patients demonstrate that a high proportion of patients can achieve or exceed recommended treatment targets with tapinarof cream 1% QD and maintain improvements long-term. The NPF-recommended treatment target of 1% or lower BSA affected within approximately 3 months (90 days) of treatment was achieved by 40% of tapinarof-treated patients. In addition, 1% or lower BSA affected at any time during the trials was achieved by 61% of patients (median, approximately 4 months). The analyses also indicated that PASI total scores of 3 or lower and 2 or lower were achieved by 75% and 67% of tapinarof-treated patients, respectively, within 2 to 3 months.

These findings support the previously reported efficacy of tapinarof cream, including high rates of complete disease clearance (40.9% [312/763]), durable response following treatment interruption, an off-therapy remittive effect of approximately 4 months, and good disease control on therapy with no evidence of tachyphylaxis.17,18

CONCLUSION

Taken together with previously reported tapinarof efficacy and safety results, our findings demonstrate that a high proportion of patients treated with tapinarof cream as monotherapy can achieve aggressive treatment targets set by both US and European guidelines developed for systemic and biologic therapies. Tapinarof cream 1% QD is an effective topical treatment option for patients with plaque psoriasis that has been approved without restrictions relating to severity or extent of disease treated, duration of use, or application sites, including application to sensitive and intertriginous skin.

Acknowledgments—Editorial and medical writing support under the guidance of the authors was provided by Melanie Govender, MSc (Med), ApotheCom (United Kingdom), and was funded by Dermavant Sciences, Inc, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP) guidelines.

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease affecting approximately 8 million adults in the United States and 2% of the global population.1,2 Psoriasis causes pain, itching, and disfigurement and is associated with a physical, psychological, and economic burden that substantially affects health-related quality of life.3-5

Setting treatment goals and treating to target are evidence-based approaches that have been successfully applied to several chronic diseases to improve patient outcomes, including diabetes, hypertension, and rheumatoid arthritis.6-9 Treat-to-target strategies generally set low disease activity (or remission) as an overall goal and seek to achieve this using available therapeutic options as necessary. Introduced following the availability of biologics and targeted systemic therapies, treat-to-target strategies generally provide guidance on expectations of treatment but not specific treatments, as personalized treatment decisions depend on an assessment of individual patients and consider clinical and demographic features as well as preferences for available therapeutic options. If targets are not achieved in the assigned time span, adjustments can be made to the treatment approach in close consultation with the patient. If the target is reached, follow-up visits can be scheduled to ensure improvement is maintained or to establish if more aggressive goals could be selected.

Treat-to-target strategies for the management of psoriasis developed by the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) Medical Board include reducing the extent of psoriasis to 1% or lower total body surface area (BSA) after 3 months of treatment.10 Treatment targets endorsed by the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) in guidelines on the use of systemic therapies in psoriasis include achieving a 75% or greater reduction in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score within 3 to 4 months of treatment.11

In clinical practice, many patients do not achieve these treatment targets, and topical treatments alone generally are insufficient in achieving treatment goals for psoriasis.12,13 Moreover, conventional topical treatments (eg, topical corticosteroids) used by most patients with psoriasis regardless of disease severity are associated with adverse events that can limit their use. Most topical corticosteroids have US Food and Drug Administration label restrictions relating to sites of application, duration and extent of use, and frequency of administration.14,15

Tapinarof cream 1% (VTAMA [Dermavant Sciences, Inc]) is a first-in-class topical nonsteroidal aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist that was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of plaque psoriasis in adults16 and is being studied for the treatment of plaque psoriasis in children 2 years and older as well as for atopic dermatitis in adults and children 2 years and older. In PSOARING 1 (ClinicalTrials .gov identifier NCT03956355) and PSOARING 2 (NCT03983980)—identical 12-week pivotal phase 3 trials—monotherapy with tapinarof cream 1% once daily (QD) demonstrated statistically significant efficacy vs vehicle cream and was well tolerated in adults with mild to severe plaque psoriasis (Supplementary Figure S1).17 Lebwohl et al17 reported that significantly higher PASI75 responses were observed at week 12 with tapinarof cream vs vehicle in PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2 (36% and 48% vs 10% and 7%, respectively; both P<.0001). A significantly higher PASI90 response of 19% and 21% at week 12 also was observed with tapinarof cream vs 2% and 3% with vehicle in PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2, respectively (P=.0005 and P<.0001).17

In PSOARING 3 (NCT04053387)—the long-term extension trial (Supplementary Figure S1)—efficacy continued to improve or was maintained beyond the two 12-week trials, with improvements in total BSA affected and PASI scores for up to 52 weeks.18 Tapinarof cream 1% QD demonstrated positive, rapid, and durable outcomes in PSOARING 3, including high rates of complete disease clearance (Physician Global Assessment [PGA] score=0 [clear])(40.9% [312/763]), durability of response on treatment with no evidence of tachyphylaxis, and a remittive effect of approximately 4 months when off therapy (defined as maintenance of a PGA score of 0 [clear] or 1 [almost clear] after first achieving a PGA score of 0).18

Herein, we report absolute treatment targets for patients with plaque psoriasis who received tapinarof cream 1% QD in the PSOARING trials that are at least as stringent as the corresponding NPF and EADV targets of achieving a total BSA affected of 1% or lower or a PASI75 response within 3 to 4 months, respectively.

METHODS

Study Design

The pooled efficacy analyses included all patients with a baseline PGA score of 2 or higher (mild or worse) before treatment with tapinarof cream 1% QD in the PSOARING trials. This included patients who received tapinarof cream 1% in PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2 who may or may not have continued into PSOARING 3, as well as those who received the vehicle in PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2 who enrolled in PSOARING 3 and had a PGA score of 2 or higher before receiving tapinarof cream 1%.

Trial Participants

Full methods, including inclusion and exclusion criteria, for the PSOARING trials have been previously reported.17,18 Patients were aged 18 to 75 years and had chronic plaque psoriasis that was stable for at least 6 months before randomization; 3% to 20% total BSA affected (excluding the scalp, palms, fingernails, toenails, and soles); and a PGA score of 2 (mild), 3 (moderate), or 4 (severe) at baseline.

The clinical trials were conducted in compliance with the guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was obtained from local ethics committees or institutional review boards at each center. All patients provided written informed consent.

Trial Treatment

In PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2, patients were randomized (2:1) to receive tapinarof cream 1% or vehicle QD for 12 weeks. In PSOARING 3 (the long-term extension trial), patients received up to 40 weeks of open-label tapinarof, followed by 4 weeks of follow-up off treatment. Patients received intermittent or continuous treatment with tapinarof cream 1% in PSOARING 3 based on PGA score: those entering the trial with a PGA score of 1 or higher received tapinarof cream 1% until complete disease clearance was achieved (defined as a PGA score of 0 [clear]). Those entering PSOARING 3 with or achieving a PGA score of 0 (clear) discontinued treatment and were observed for the duration of maintenance of a PGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) while off therapy (the protocol-defined “duration of remittive effect”). If disease worsening (defined as a PGA score 2 or higher) occurred, tapinarof cream 1% was restarted and continued until a PGA score of 0 (clear) was achieved. This pattern of treatment, discontinuation on achieving a PGA score of 0 (clear), and retreatment on disease worsening continued until the end of the trial. As a result, patients in PSOARING 3 could receive tapinarof cream 1% continuously or intermittently for 40 weeks.

Outcome Measures and Statistical Analyses

The assessment of total BSA affected by plaque psoriasis is an estimate of the total extent of disease as a percentage of total skin area. In the PSOARING trials, the skin surface of one hand (palm and digits) was assumed to be approximately equivalent to 1% BSA. The total BSA affected by psoriasis was evaluated from 0% to 100%, with greater total BSA affected being an indication of more extensive disease. The BSA efficacy outcomes used in these analyses were based post hoc on the proportion of patients who achieved a 1% or lower or 0.5% or lower total BSA affected.

Psoriasis Area and Severity Index scores assess both the severity and extent of psoriasis. A PASI score lower than 5 often is considered indicative of mild psoriasis, a score of 5 to 10 indicates moderate disease, and a score higher than 10 indicates severe disease.19 The maximum PASI score is 72. The PASI efficacy outcomes used in these analyses were based post hoc on the proportion of patients who achieved an absolute total PASI score of 3 or lower, 2 or lower, and 1 or lower.

Efficacy analyses were based on pooled data for all patients in the PSOARING trials who had a PGA score of 2 to 4 (mild to severe) before treatment with tapinarof cream 1% in the intention-to-treat population using observed cases. Time-to-target analyses were based on Kaplan-Meier (KM) estimates using observed cases.

Safety analyses included the incidence and frequency of adverse events and were based on all patients who received tapinarof cream 1% in the PSOARING trials.

RESULTS

Baseline Patient Demographics and Disease Characteristics

The pooled efficacy analyses included 915 eligible patients (Table). At baseline, the mean (SD) age was 50.2 (13.25) years, 58.7% were male, the mean (SD) weight was 92.2 (23.67) kg, and the mean (SD) body mass index was 31.6 (7.53) kg/m2. The percentage of patients with a PGA score of 2 (mild), 3 (moderate), or 4 (severe) was 13.9%, 78.1%, and 8.0%, respectively. The mean (SD) PASI score was 8.7 (4.23) and mean (SD) total BSA affected was 7.8% (4.98).

Efficacy

Achievement of BSA-Affected Targets—

Achievement of Absolute PASI Targets—Across the total trial period (up to 52 weeks), an absolute total PASI score of 3 or lower was achieved by 75% of patients (686/915), with a median time to achieve this of 2 months (KM estimate: 58 days [95% CI, 57-63]); approximately 67% of patients (612/915) achieved a total PASI score of 2 or lower, with a median time to achieve of 3 months (KM estimate: 87 days [95% CI, 85-110])(Figure 2; Supplementary Figures S3a and S3b). A PASI score of 1 or lower was achieved by approximately 50% of patients (460/915), with a median time to achieve of approximately 6 months (KM estimate: 185 days [95% CI, 169-218])(Figure 2, Supplementary Figure S3c).

Illustrative Case—Case photography showing the clinical response in a 63-year-old man with moderate plaque psoriasis in PSOARING 2 is shown in Figure 3. After 12 weeks of treatment with tapinarof cream 1% QD, the patient achieved all primary and secondary efficacy end points. In addition to achieving the regulatory end point of a PGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) and a decrease from baseline of at least 2 points, achievement of 0% total BSA affected and a total PASI score of 0 at week 12 exceeded the NPF and EADV consensus treatment targets.10,11 Targets were achieved as early as week 4, with a total BSA affected of 0.5% or lower and a total PASI score of 1 or lower, illustrated by marked skin clearing and only faint residual erythema that completely resolved at week 12, with the absence of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Safety

Safety data for the PSOARING trials have been previously reported.17,18 The most common treatment-emergent adverse events were folliculitis, contact dermatitis, upper respiratory tract infection, and nasopharyngitis. Treatment-emergent adverse events generally were mild or moderate in severity and did not lead to trial discontinuation.17,18

COMMENT

Treat-to-target management approaches aim to improve patient outcomes by striving to achieve optimal goals. The treat-to-target approach supports shared decision-making between clinicians and patients based on common expectations of what constitutes treatment success.

The findings of this analysis based on pooled data from a large cohort of patients demonstrate that a high proportion of patients can achieve or exceed recommended treatment targets with tapinarof cream 1% QD and maintain improvements long-term. The NPF-recommended treatment target of 1% or lower BSA affected within approximately 3 months (90 days) of treatment was achieved by 40% of tapinarof-treated patients. In addition, 1% or lower BSA affected at any time during the trials was achieved by 61% of patients (median, approximately 4 months). The analyses also indicated that PASI total scores of 3 or lower and 2 or lower were achieved by 75% and 67% of tapinarof-treated patients, respectively, within 2 to 3 months.

These findings support the previously reported efficacy of tapinarof cream, including high rates of complete disease clearance (40.9% [312/763]), durable response following treatment interruption, an off-therapy remittive effect of approximately 4 months, and good disease control on therapy with no evidence of tachyphylaxis.17,18

CONCLUSION

Taken together with previously reported tapinarof efficacy and safety results, our findings demonstrate that a high proportion of patients treated with tapinarof cream as monotherapy can achieve aggressive treatment targets set by both US and European guidelines developed for systemic and biologic therapies. Tapinarof cream 1% QD is an effective topical treatment option for patients with plaque psoriasis that has been approved without restrictions relating to severity or extent of disease treated, duration of use, or application sites, including application to sensitive and intertriginous skin.

Acknowledgments—Editorial and medical writing support under the guidance of the authors was provided by Melanie Govender, MSc (Med), ApotheCom (United Kingdom), and was funded by Dermavant Sciences, Inc, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP) guidelines.

- Armstrong AW, Mehta MD, Schupp CW, et al. Psoriasis prevalence in adults in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:940-946.

- Parisi R, Iskandar IYK, Kontopantelis E, et al. National, regional, and worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis: systematic analysis and modelling study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1590.

- Pilon D, Teeple A, Zhdanava M, et al. The economic burden of psoriasis with high comorbidity among privately insured patients in the United States. J Med Econ. 2019;22:196-203.

- Singh S, Taylor C, Kornmehl H, et al. Psoriasis and suicidality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:425-440.e2.

- Feldman SR, Goffe B, Rice G, et al. The challenge of managing psoriasis: unmet medical needs and stakeholder perspectives. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2016;9:504-513.

- Ford JA, Solomon DH. Challenges in implementing treat-to-target strategies in rheumatology. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2019;45:101-112.

- Sitbon O, Galiè N. Treat-to-target strategies in pulmonary arterial hypertension: the importance of using multiple goals. Eur Respir Rev. 2010;19:272-278.

- Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:631-637.

- Wangnoo SK, Sethi B, Sahay RK, et al. Treat-to-target trials in diabetes. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;18:166-174.

- Armstrong AW, Siegel MP, Bagel J, et al. From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: treatment targets for plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:290-298.

- Pathirana D, Ormerod AD, Saiag P, et al. European S3-guidelines on the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(Suppl 2):1-70.

- Strober BE, van der Walt JM, Armstrong AW, et al. Clinical goals and barriers to effective psoriasis care. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2019; 9:5-18.

- Bagel J, Gold LS. Combining topical psoriasis treatment to enhance systemic and phototherapy: a review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1209-1222.

- Elmets CA, Korman NJ, Prater EF, et al. Joint AAD-NPF Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapy and alternative medicine modalities for psoriasis severity measures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:432-470.

- Stein Gold LF. Topical therapies for psoriasis: improving management strategies and patient adherence. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2016;35 (2 Suppl 2):S36-S44; quiz S45.

- VTAMA® (tapinarof) cream. Prescribing information. Dermavant Sciences; 2022. Accessed September 13, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/215272s000lbl.pdf

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229 and supplementary appendix.

- Strober B, Stein Gold L, Bissonnette R, et al. One-year safety and efficacy of tapinarof cream for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: results from the PSOARING 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:800-806.

- Clinical Review Report: Guselkumab (Tremfya) [Internet]. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2018. Accessed September 13, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534047/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK534047.pdf

- Armstrong AW, Mehta MD, Schupp CW, et al. Psoriasis prevalence in adults in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:940-946.

- Parisi R, Iskandar IYK, Kontopantelis E, et al. National, regional, and worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis: systematic analysis and modelling study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1590.

- Pilon D, Teeple A, Zhdanava M, et al. The economic burden of psoriasis with high comorbidity among privately insured patients in the United States. J Med Econ. 2019;22:196-203.

- Singh S, Taylor C, Kornmehl H, et al. Psoriasis and suicidality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:425-440.e2.

- Feldman SR, Goffe B, Rice G, et al. The challenge of managing psoriasis: unmet medical needs and stakeholder perspectives. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2016;9:504-513.

- Ford JA, Solomon DH. Challenges in implementing treat-to-target strategies in rheumatology. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2019;45:101-112.

- Sitbon O, Galiè N. Treat-to-target strategies in pulmonary arterial hypertension: the importance of using multiple goals. Eur Respir Rev. 2010;19:272-278.

- Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:631-637.

- Wangnoo SK, Sethi B, Sahay RK, et al. Treat-to-target trials in diabetes. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;18:166-174.

- Armstrong AW, Siegel MP, Bagel J, et al. From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: treatment targets for plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:290-298.

- Pathirana D, Ormerod AD, Saiag P, et al. European S3-guidelines on the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(Suppl 2):1-70.

- Strober BE, van der Walt JM, Armstrong AW, et al. Clinical goals and barriers to effective psoriasis care. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2019; 9:5-18.

- Bagel J, Gold LS. Combining topical psoriasis treatment to enhance systemic and phototherapy: a review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1209-1222.

- Elmets CA, Korman NJ, Prater EF, et al. Joint AAD-NPF Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapy and alternative medicine modalities for psoriasis severity measures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:432-470.

- Stein Gold LF. Topical therapies for psoriasis: improving management strategies and patient adherence. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2016;35 (2 Suppl 2):S36-S44; quiz S45.

- VTAMA® (tapinarof) cream. Prescribing information. Dermavant Sciences; 2022. Accessed September 13, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/215272s000lbl.pdf

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229 and supplementary appendix.

- Strober B, Stein Gold L, Bissonnette R, et al. One-year safety and efficacy of tapinarof cream for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: results from the PSOARING 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:800-806.

- Clinical Review Report: Guselkumab (Tremfya) [Internet]. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2018. Accessed September 13, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534047/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK534047.pdf

Practice Points

- In clinical practice, many patients with psoriasis do not achieve treatment targets set forth by the National Psoriasis Foundation and the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, and topical treatments alone generally are insufficient in achieving treatment goals for psoriasis.

- Tapinarof cream 1% is a nonsteroidal aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of plaque psoriasis in adults; it also is being studied for the treatment of plaque psoriasis in children 2 years and older.

- Tapinarof cream 1% is an effective topical treatment option for patients with plaque psoriasis of any severity, with no limitations on treatment duration, total extent of use, or application sites, including intertriginous skin and sensitive areas.

Brodalumab in an Organ Transplant Recipient With Psoriasis

The treatment landscape for psoriasis has evolved rapidly over the last decade. Biologic therapies have demonstrated robust efficacy and acceptable safety profiles among many patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. However, the use of biologics among immunocompromised patients with psoriasis rarely is discussed in the literature. As new biologics for psoriasis are being developed, a critical gap exists in the literature regarding the safety and efficacy of these medications in immunocompromised patients. Per American Academy of Dermatology–National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines, caution should be exercised when using biologics in patients with immunocompromising conditions.1 In organ transplant recipients, the potential risks of combining systemic medications used for organ transplantation and biologic treatments for psoriasis are unknown.2

In the posttransplant period, the immunosuppressive regimens for transplantation likely will improve psoriasis. However, patients with organ transplant and psoriasis still experience flares that can be challenging to treat.3 Prior treatment modalities to prevent psoriasis flares in organ transplant recipients have relied largely on topical therapies, posttransplant immunosuppressive medications (eg, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil) that prevent graft rejection, and systemic corticosteroids. We report a case of a 50-year-old man with a recent history of liver transplantation who presented with severe plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.

Case Report

A 50-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis that had been present for 15 years. His plaque psoriasis covered approximately 40% of the body surface area, including the scalp, trunk, arms, and legs. In addition, he had diffuse joint pain in the hands and feet; a radiograph revealed active psoriatic arthritis involving the joints of the fingers and toes.

One year prior to presentation to our dermatology clinic, the patient underwent an an orthotopic liver transplant for history of Child-Pugh class C liver cirrhosis secondary to untreated hepatitis C virus (HCV) and alcohol use that was complicated by hepatocellular carcinoma. He acquired a high-risk donor liver that was HCV positive with HCV genotype 1a. Starting 2 months after the transplant, he underwent 12 weeks of treatment for HCV with glecaprevir-pibrentasvir. Once his HCV treatment course was completed, he achieved a sustained virologic response with an undetectable viral load. To prevent transplant rejection, he was on chronic immunosuppression with tacrolimus, a calcineurin inhibitor, and mycophenolate mofetil, an inhibitor of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase whose action leads to decreased proliferation of T cells and B cells.

The patient’s psoriasis initially was treated with triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% applied twice daily to the psoriasis lesions for 1 year by another dermatologist. However, his psoriasis progressed to involve 40% of the body surface area. Following our evaluation 1 year posttransplant, the patient was started on subcutaneous brodalumab 210 mg at weeks 0, 1, and 2, then every 2 weeks thereafter. Approximately 10 weeks after initiation of brodalumab, the patient’s psoriasis was completely clear, and he was asymptomatic from psoriatic arthritis. The patient’s improvement persisted at 6 months, and his liver enzymes, including alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin, alanine transaminase, and aspartate transaminase, continued to be within reference range. To date, there has been no evidence of posttransplant complications such as graft-vs-host disease, serious infections, or skin cancers.

Comment

Increased Risk for Infection and Malignancies in Transplant Patients

Transplant patients are on immunosuppressive regimens that increase their risk for infection and malignancies. For example, high doses of immunosuppresants predispose these patients to reactivation of viral infections, including BK and JC viruses.4 In addition, the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma is 65- to 250-fold higher in transplant patients compared to the general population.5 The risk for Merkel cell carcinoma is increased after solid organ transplantation compared to the general population.6 Importantly, transplant patients have a higher mortality from skin cancers than other types of cancers, including breast and colon cancer.7

Psoriasis in Organ Transplant Recipients

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated, inflammatory disease with a prevalence of approximately 3% in the United States.8 Approximately one-third of patients with psoriasis develop psoriatic arthritis.9 Organ transplant recipients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis represent a unique patient population whereby their use of chronic immunosuppressive medications to prevent graft rejection may put them at risk for developing infections and malignancies.

Special Considerations for Brodalumab

Brodalumab is an immunomodulatory biologic that binds to and inhibits IL-17RA, thereby inhibiting the actions of IL-17A, F, E, and C.2 The blockade of IL-17RA by brodalumab has been shown to result in reversal of psoriatic phenotype and gene expression patterns.10 Brodalumab was chosen as the treatment in our patient because it has a rapid onset of action, sustained efficacy, and an acceptable safety profile.11 Brodalumab is well tolerated, with approximately 60% of patients achieving clearance long-term.12 Candidal infections can occur in patients with brodalumab, but the rates are low and they are reversible with antifungal treatment.13 The increased mucocutaneous candidal infections are consistent with medications whose mechanism of action is IL-17 inhibition.14,15 The most common adverse reactions found were nasopharyngitis and headache.16 The causal link between brodalumab and suicidality has not been established.17

The use of brodalumab for psoriasis in organ transplant recipients has not been previously reported in the literature. A few case reports have been published on the successful use of etanercept and ixekizumab as biologic treatment options for psoriasis in transplant patients.18-23 In addition to choosing an appropriate biologic for psoriasis in transplant patients, transplant providers may evaluate the choice of immunosuppression regimen for the organ transplant in the context of psoriasis. In a retrospective analysis of liver transplant patients with psoriasis, Foroncewicz et al3 found cyclosporine, which was used as an antirejection immunosuppressive agent in the posttransplant period, to be more effective than tacrolimus in treating recurrent psoriasis in liver transplant recipients.

Our case illustrates one example of the successful use of brodalumab in a patient with a solid organ transplant. Our patient’s psoriasis and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis greatly improved after initiation of brodalumab. In the posttransplant period, the patient did not develop graft-vs-host disease, infections, malignancies, depression, or suicidal ideation while taking brodalumab.

Conclusion

It is important that the patient, dermatology team, and transplant team work together to navigate the challenges and relatively unknown landscape of psoriasis treatment in organ transplant recipients. As the number of organ transplant recipients continues to increase, this issue will become more clinically relevant. Case reports and future prospective studies will continue to inform us regarding the role of biologics in psoriasis treatment posttransplantation.

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072.

- Prussick R, Wu JJ, Armstrong AW, et al. Psoriasis in solid organ transplant patients: best practice recommendations from The Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Dermatol Treat. 2018;29:329-333.

- Foroncewicz B, Mucha K, Lerut J, et al. Cyclosporine is superior to tacrolimus in liver transplant recipients with recurrent psoriasis. Ann Transplant. 2014;19:427-433.

- Boukoum H, Nahdi I, Sahtout W, et al. BK and JC virus infections in healthy patients compared to kidney transplant recipients in Tunisia. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2016;97:204-208.

- Bouwes Bavinck JN, Euvrard S, Naldi L, et al. Keratotic skin lesions and other risk factors are associated with skin cancer in organ-transplant recipients: a case-control study in The Netherlands, United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Italy. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1647-1656.

- Clark CA, Robbins HA, Tatalovich Z, et al. Risk of Merkel cell carcinoma after transplant. Clin Oncol. 2019;31:779-788.

- Lakhani NA, Saraiya M, Thompson TD, et al. Total body skin examination for skin cancer screening among U.S. adults from 2000 to 2010. Prev Med. 2014;61:75-80.

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:512-516.

- Alinaghi F, Calov M, Kristensen LE, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:251-265.

- Russell CB, Rand H, Bigler J, et al. Gene expression profiles normalized in psoriatic skin by treatment with brodalumab, a human anti-IL-17 receptor monoclonal antibody. J Immunol. 2014;192:3828-3836.

- Foulkes AC, Warren RB. Brodalumab in psoriasis: evidence to date and clinical potential. Drugs Context. 2019;8:212570. doi:10.7573/dic.212570

- Puig L, Lebwohl M, Bachelez H, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of brodalumab in the treatment of psoriasis: 120-week results from the randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator-controlled phase 3 AMAGINE-2 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:352-359.

- Lebwohl M, Strober B, Menter A, et al. Phase 3 studies comparing brodalumab and ustekinumab in psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1318-1328.

- Conti HR, Shen F, Nayyar N, et al. Th17 cells and IL-17 receptor signaling are essential for mucosal host defense against oral candidiasis. J Exp Med. 2009;206:299-311.

- Puel A, Cypowyj S, Bustamante J, et al. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in humans with inborn errors of interleukin-17 immunity. Science. 2011;332:65-68.

- Farahnik B, Beroukhim B, Abrouk M, et al. Brodalumab for the treatment of psoriasis: a review of Phase III trials. Dermatol Ther. 2016;6:111-124.

- Lebwohl MG, Papp KA, Marangell LB, et al. Psychiatric adverse events during treatment with brodalumab: analysis of psoriasis clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:81-89.

- DeSimone C, Perino F, Caldarola G, et al. Treatment of psoriasis with etanercept in immunocompromised patients: two case reports. J Int Med Res. 2016;44:67-71.

- Madankumar R, Teperman LW, Stein JA. Use of etanercept for psoriasis in a liver transplant recipient. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:S36-S37.

- Collazo MH, González JR, Torres EA. Etanercept therapy for psoriasis in a patient with concomitant hepatitis C and liver transplant. P R Health Sci J. 2008;27:346-347.

- Hoover WD. Etanercept therapy for severe plaque psoriasis in a patient who underwent a liver transplant. Cutis. 2007;80:211-214.

- Brokalaki EI, Voshege N, Witzke O, et al. Treatment of severe psoriasis with etanercept in a pancreas-kidney transplant recipient. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:2776-2777.

- Lora V, Graceffa D, De Felice C, et al. Treatment of severe psoriasis with ixekizumab in a liver transplant recipient with concomitant hepatitis B virus infection. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:E12909.

The treatment landscape for psoriasis has evolved rapidly over the last decade. Biologic therapies have demonstrated robust efficacy and acceptable safety profiles among many patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. However, the use of biologics among immunocompromised patients with psoriasis rarely is discussed in the literature. As new biologics for psoriasis are being developed, a critical gap exists in the literature regarding the safety and efficacy of these medications in immunocompromised patients. Per American Academy of Dermatology–National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines, caution should be exercised when using biologics in patients with immunocompromising conditions.1 In organ transplant recipients, the potential risks of combining systemic medications used for organ transplantation and biologic treatments for psoriasis are unknown.2

In the posttransplant period, the immunosuppressive regimens for transplantation likely will improve psoriasis. However, patients with organ transplant and psoriasis still experience flares that can be challenging to treat.3 Prior treatment modalities to prevent psoriasis flares in organ transplant recipients have relied largely on topical therapies, posttransplant immunosuppressive medications (eg, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil) that prevent graft rejection, and systemic corticosteroids. We report a case of a 50-year-old man with a recent history of liver transplantation who presented with severe plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.

Case Report

A 50-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis that had been present for 15 years. His plaque psoriasis covered approximately 40% of the body surface area, including the scalp, trunk, arms, and legs. In addition, he had diffuse joint pain in the hands and feet; a radiograph revealed active psoriatic arthritis involving the joints of the fingers and toes.

One year prior to presentation to our dermatology clinic, the patient underwent an an orthotopic liver transplant for history of Child-Pugh class C liver cirrhosis secondary to untreated hepatitis C virus (HCV) and alcohol use that was complicated by hepatocellular carcinoma. He acquired a high-risk donor liver that was HCV positive with HCV genotype 1a. Starting 2 months after the transplant, he underwent 12 weeks of treatment for HCV with glecaprevir-pibrentasvir. Once his HCV treatment course was completed, he achieved a sustained virologic response with an undetectable viral load. To prevent transplant rejection, he was on chronic immunosuppression with tacrolimus, a calcineurin inhibitor, and mycophenolate mofetil, an inhibitor of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase whose action leads to decreased proliferation of T cells and B cells.

The patient’s psoriasis initially was treated with triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% applied twice daily to the psoriasis lesions for 1 year by another dermatologist. However, his psoriasis progressed to involve 40% of the body surface area. Following our evaluation 1 year posttransplant, the patient was started on subcutaneous brodalumab 210 mg at weeks 0, 1, and 2, then every 2 weeks thereafter. Approximately 10 weeks after initiation of brodalumab, the patient’s psoriasis was completely clear, and he was asymptomatic from psoriatic arthritis. The patient’s improvement persisted at 6 months, and his liver enzymes, including alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin, alanine transaminase, and aspartate transaminase, continued to be within reference range. To date, there has been no evidence of posttransplant complications such as graft-vs-host disease, serious infections, or skin cancers.

Comment

Increased Risk for Infection and Malignancies in Transplant Patients

Transplant patients are on immunosuppressive regimens that increase their risk for infection and malignancies. For example, high doses of immunosuppresants predispose these patients to reactivation of viral infections, including BK and JC viruses.4 In addition, the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma is 65- to 250-fold higher in transplant patients compared to the general population.5 The risk for Merkel cell carcinoma is increased after solid organ transplantation compared to the general population.6 Importantly, transplant patients have a higher mortality from skin cancers than other types of cancers, including breast and colon cancer.7

Psoriasis in Organ Transplant Recipients

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated, inflammatory disease with a prevalence of approximately 3% in the United States.8 Approximately one-third of patients with psoriasis develop psoriatic arthritis.9 Organ transplant recipients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis represent a unique patient population whereby their use of chronic immunosuppressive medications to prevent graft rejection may put them at risk for developing infections and malignancies.

Special Considerations for Brodalumab

Brodalumab is an immunomodulatory biologic that binds to and inhibits IL-17RA, thereby inhibiting the actions of IL-17A, F, E, and C.2 The blockade of IL-17RA by brodalumab has been shown to result in reversal of psoriatic phenotype and gene expression patterns.10 Brodalumab was chosen as the treatment in our patient because it has a rapid onset of action, sustained efficacy, and an acceptable safety profile.11 Brodalumab is well tolerated, with approximately 60% of patients achieving clearance long-term.12 Candidal infections can occur in patients with brodalumab, but the rates are low and they are reversible with antifungal treatment.13 The increased mucocutaneous candidal infections are consistent with medications whose mechanism of action is IL-17 inhibition.14,15 The most common adverse reactions found were nasopharyngitis and headache.16 The causal link between brodalumab and suicidality has not been established.17

The use of brodalumab for psoriasis in organ transplant recipients has not been previously reported in the literature. A few case reports have been published on the successful use of etanercept and ixekizumab as biologic treatment options for psoriasis in transplant patients.18-23 In addition to choosing an appropriate biologic for psoriasis in transplant patients, transplant providers may evaluate the choice of immunosuppression regimen for the organ transplant in the context of psoriasis. In a retrospective analysis of liver transplant patients with psoriasis, Foroncewicz et al3 found cyclosporine, which was used as an antirejection immunosuppressive agent in the posttransplant period, to be more effective than tacrolimus in treating recurrent psoriasis in liver transplant recipients.

Our case illustrates one example of the successful use of brodalumab in a patient with a solid organ transplant. Our patient’s psoriasis and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis greatly improved after initiation of brodalumab. In the posttransplant period, the patient did not develop graft-vs-host disease, infections, malignancies, depression, or suicidal ideation while taking brodalumab.

Conclusion

It is important that the patient, dermatology team, and transplant team work together to navigate the challenges and relatively unknown landscape of psoriasis treatment in organ transplant recipients. As the number of organ transplant recipients continues to increase, this issue will become more clinically relevant. Case reports and future prospective studies will continue to inform us regarding the role of biologics in psoriasis treatment posttransplantation.

The treatment landscape for psoriasis has evolved rapidly over the last decade. Biologic therapies have demonstrated robust efficacy and acceptable safety profiles among many patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. However, the use of biologics among immunocompromised patients with psoriasis rarely is discussed in the literature. As new biologics for psoriasis are being developed, a critical gap exists in the literature regarding the safety and efficacy of these medications in immunocompromised patients. Per American Academy of Dermatology–National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines, caution should be exercised when using biologics in patients with immunocompromising conditions.1 In organ transplant recipients, the potential risks of combining systemic medications used for organ transplantation and biologic treatments for psoriasis are unknown.2

In the posttransplant period, the immunosuppressive regimens for transplantation likely will improve psoriasis. However, patients with organ transplant and psoriasis still experience flares that can be challenging to treat.3 Prior treatment modalities to prevent psoriasis flares in organ transplant recipients have relied largely on topical therapies, posttransplant immunosuppressive medications (eg, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil) that prevent graft rejection, and systemic corticosteroids. We report a case of a 50-year-old man with a recent history of liver transplantation who presented with severe plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.

Case Report

A 50-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis that had been present for 15 years. His plaque psoriasis covered approximately 40% of the body surface area, including the scalp, trunk, arms, and legs. In addition, he had diffuse joint pain in the hands and feet; a radiograph revealed active psoriatic arthritis involving the joints of the fingers and toes.

One year prior to presentation to our dermatology clinic, the patient underwent an an orthotopic liver transplant for history of Child-Pugh class C liver cirrhosis secondary to untreated hepatitis C virus (HCV) and alcohol use that was complicated by hepatocellular carcinoma. He acquired a high-risk donor liver that was HCV positive with HCV genotype 1a. Starting 2 months after the transplant, he underwent 12 weeks of treatment for HCV with glecaprevir-pibrentasvir. Once his HCV treatment course was completed, he achieved a sustained virologic response with an undetectable viral load. To prevent transplant rejection, he was on chronic immunosuppression with tacrolimus, a calcineurin inhibitor, and mycophenolate mofetil, an inhibitor of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase whose action leads to decreased proliferation of T cells and B cells.

The patient’s psoriasis initially was treated with triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% applied twice daily to the psoriasis lesions for 1 year by another dermatologist. However, his psoriasis progressed to involve 40% of the body surface area. Following our evaluation 1 year posttransplant, the patient was started on subcutaneous brodalumab 210 mg at weeks 0, 1, and 2, then every 2 weeks thereafter. Approximately 10 weeks after initiation of brodalumab, the patient’s psoriasis was completely clear, and he was asymptomatic from psoriatic arthritis. The patient’s improvement persisted at 6 months, and his liver enzymes, including alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin, alanine transaminase, and aspartate transaminase, continued to be within reference range. To date, there has been no evidence of posttransplant complications such as graft-vs-host disease, serious infections, or skin cancers.

Comment

Increased Risk for Infection and Malignancies in Transplant Patients

Transplant patients are on immunosuppressive regimens that increase their risk for infection and malignancies. For example, high doses of immunosuppresants predispose these patients to reactivation of viral infections, including BK and JC viruses.4 In addition, the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma is 65- to 250-fold higher in transplant patients compared to the general population.5 The risk for Merkel cell carcinoma is increased after solid organ transplantation compared to the general population.6 Importantly, transplant patients have a higher mortality from skin cancers than other types of cancers, including breast and colon cancer.7

Psoriasis in Organ Transplant Recipients

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated, inflammatory disease with a prevalence of approximately 3% in the United States.8 Approximately one-third of patients with psoriasis develop psoriatic arthritis.9 Organ transplant recipients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis represent a unique patient population whereby their use of chronic immunosuppressive medications to prevent graft rejection may put them at risk for developing infections and malignancies.

Special Considerations for Brodalumab

Brodalumab is an immunomodulatory biologic that binds to and inhibits IL-17RA, thereby inhibiting the actions of IL-17A, F, E, and C.2 The blockade of IL-17RA by brodalumab has been shown to result in reversal of psoriatic phenotype and gene expression patterns.10 Brodalumab was chosen as the treatment in our patient because it has a rapid onset of action, sustained efficacy, and an acceptable safety profile.11 Brodalumab is well tolerated, with approximately 60% of patients achieving clearance long-term.12 Candidal infections can occur in patients with brodalumab, but the rates are low and they are reversible with antifungal treatment.13 The increased mucocutaneous candidal infections are consistent with medications whose mechanism of action is IL-17 inhibition.14,15 The most common adverse reactions found were nasopharyngitis and headache.16 The causal link between brodalumab and suicidality has not been established.17

The use of brodalumab for psoriasis in organ transplant recipients has not been previously reported in the literature. A few case reports have been published on the successful use of etanercept and ixekizumab as biologic treatment options for psoriasis in transplant patients.18-23 In addition to choosing an appropriate biologic for psoriasis in transplant patients, transplant providers may evaluate the choice of immunosuppression regimen for the organ transplant in the context of psoriasis. In a retrospective analysis of liver transplant patients with psoriasis, Foroncewicz et al3 found cyclosporine, which was used as an antirejection immunosuppressive agent in the posttransplant period, to be more effective than tacrolimus in treating recurrent psoriasis in liver transplant recipients.

Our case illustrates one example of the successful use of brodalumab in a patient with a solid organ transplant. Our patient’s psoriasis and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis greatly improved after initiation of brodalumab. In the posttransplant period, the patient did not develop graft-vs-host disease, infections, malignancies, depression, or suicidal ideation while taking brodalumab.

Conclusion

It is important that the patient, dermatology team, and transplant team work together to navigate the challenges and relatively unknown landscape of psoriasis treatment in organ transplant recipients. As the number of organ transplant recipients continues to increase, this issue will become more clinically relevant. Case reports and future prospective studies will continue to inform us regarding the role of biologics in psoriasis treatment posttransplantation.

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072.

- Prussick R, Wu JJ, Armstrong AW, et al. Psoriasis in solid organ transplant patients: best practice recommendations from The Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Dermatol Treat. 2018;29:329-333.

- Foroncewicz B, Mucha K, Lerut J, et al. Cyclosporine is superior to tacrolimus in liver transplant recipients with recurrent psoriasis. Ann Transplant. 2014;19:427-433.

- Boukoum H, Nahdi I, Sahtout W, et al. BK and JC virus infections in healthy patients compared to kidney transplant recipients in Tunisia. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2016;97:204-208.