User login

Hyperkeratotic Nodule on the Knee in a Patient With KID Syndrome

The Diagnosis: Proliferating Pilar Cyst

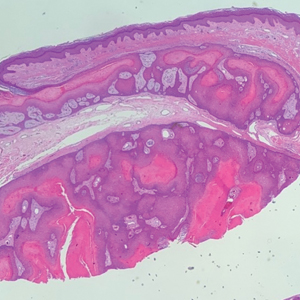

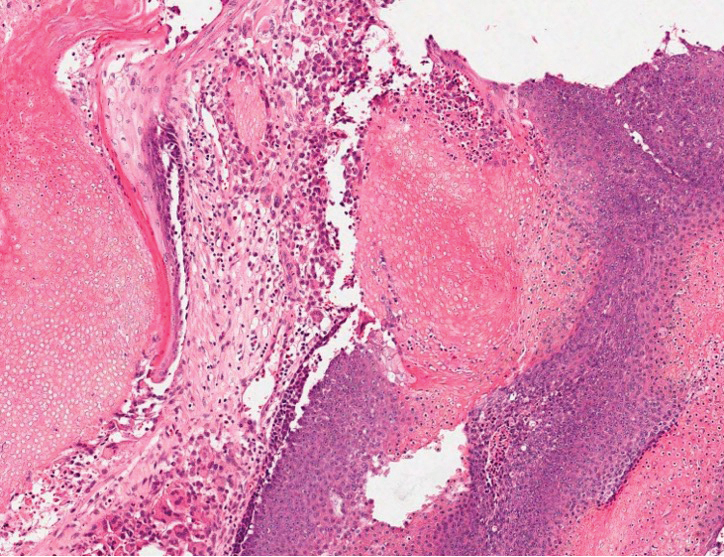

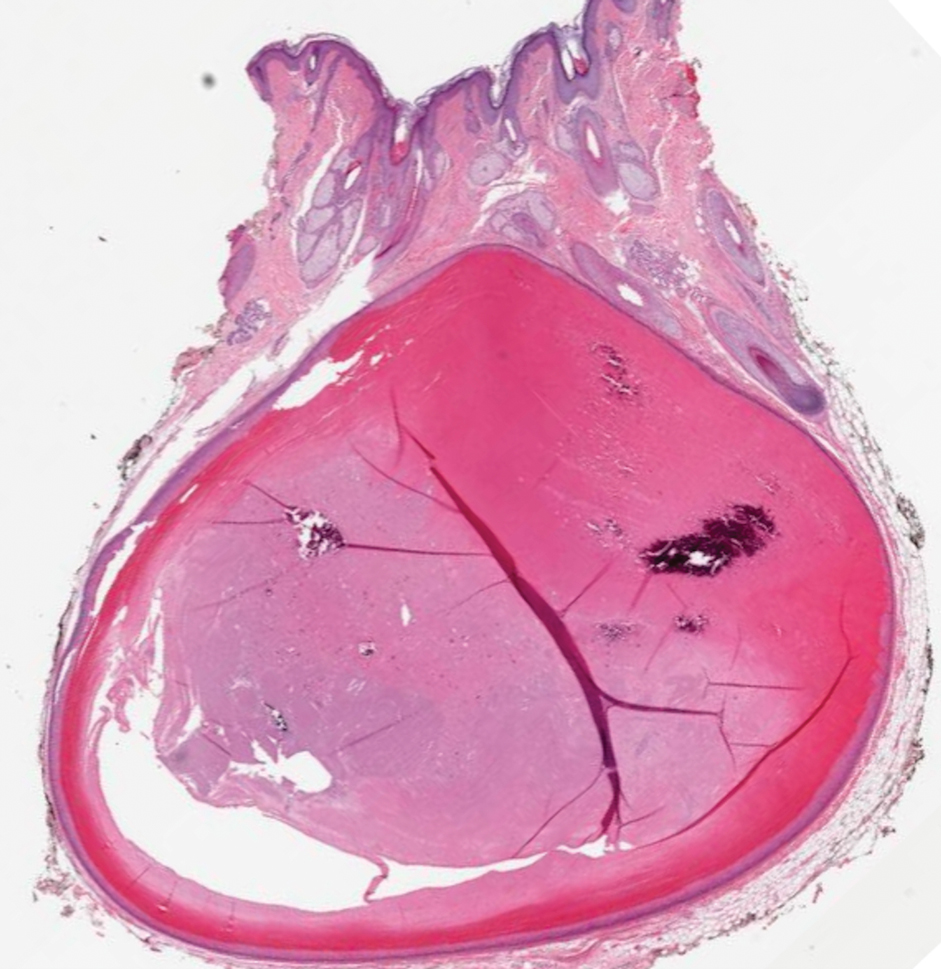

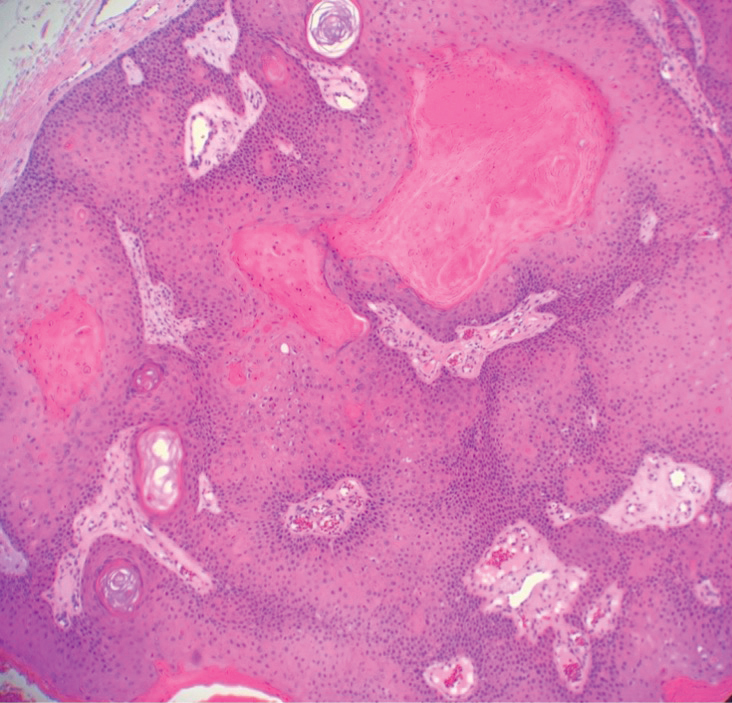

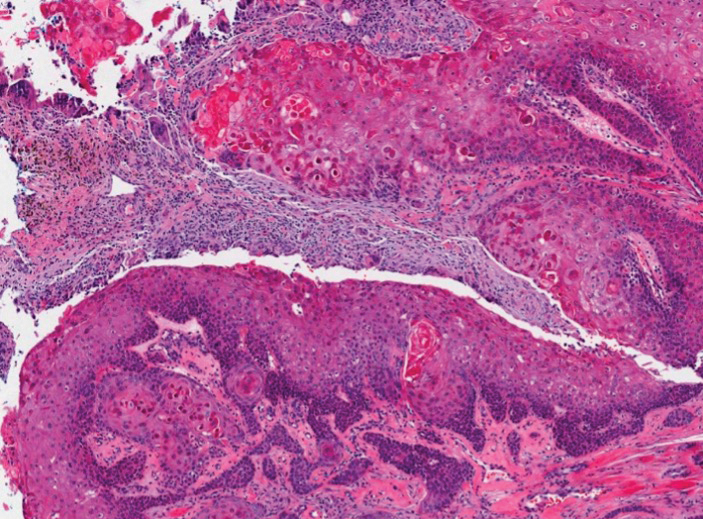

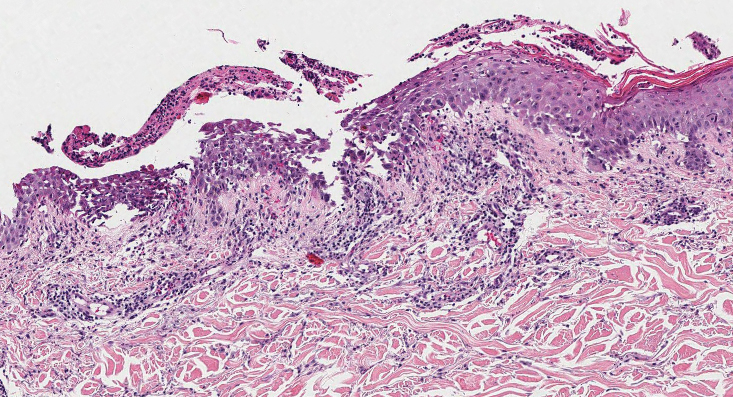

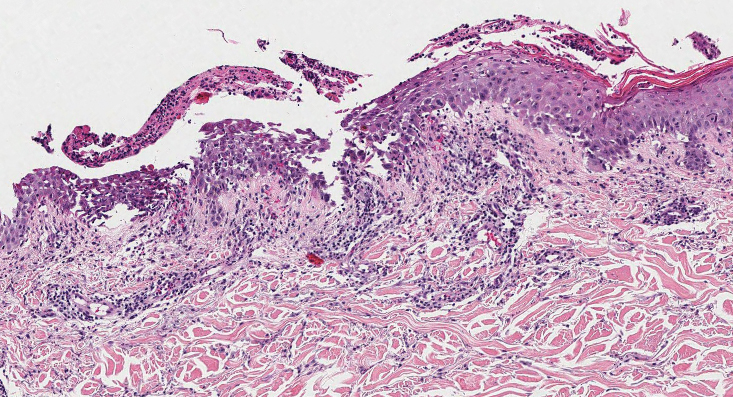

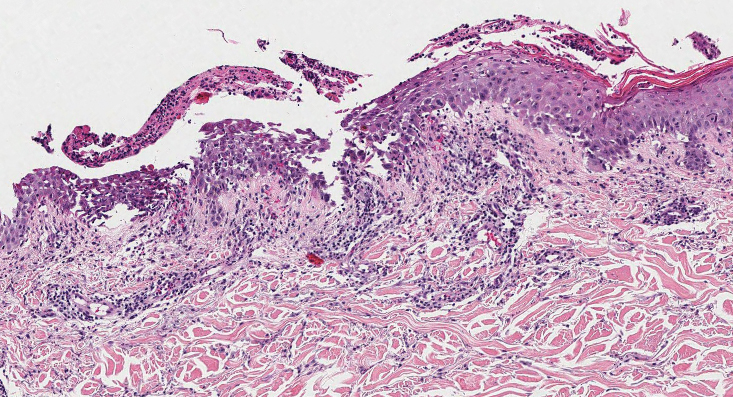

Histopathology revealed an extensive lobulated epithelial proliferation in a characteristic “rolls and scrolls” pattern (Figure 1). This finding along with the patient’s prior diagnosis of keratitis-ichthyosisdeafness (KID) syndrome supported the diagnosis of a proliferating pilar cyst.

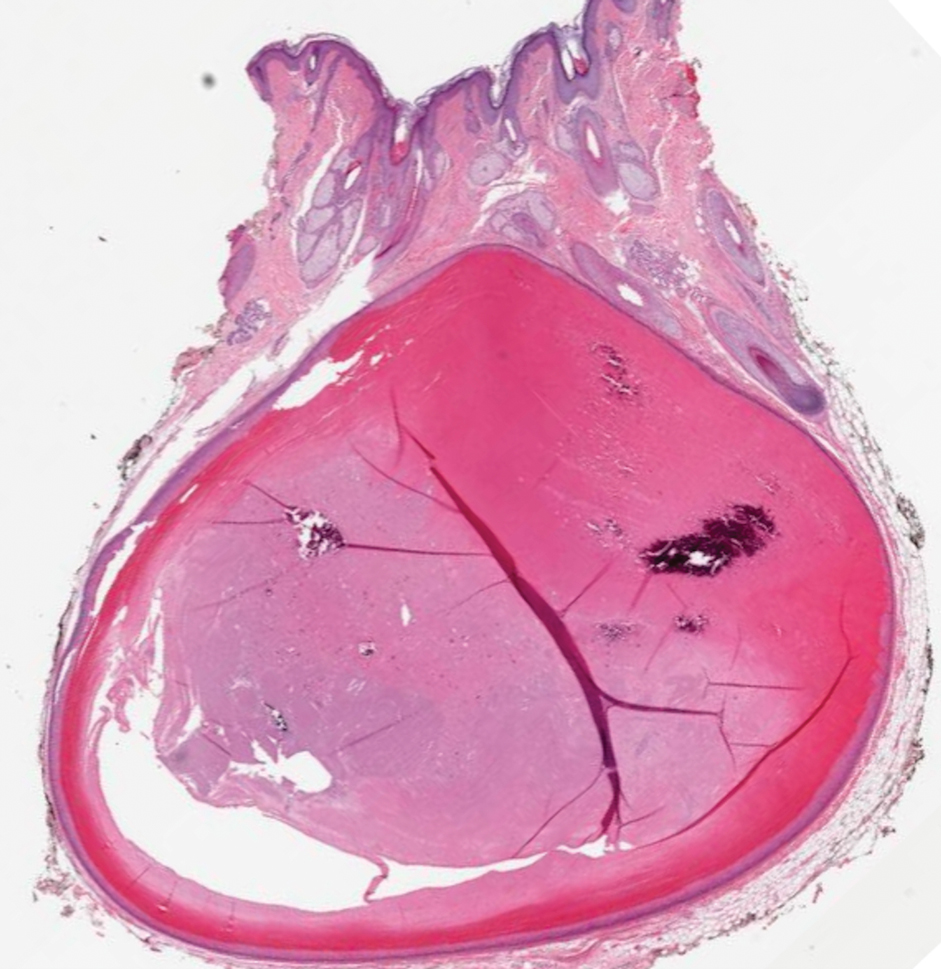

Pilar (or trichilemmal) cysts are common dermal cysts typically found on the outer root sheath of hair follicles. They clinically manifest as multiple yellow dome-shaped nodules without central puncta. They are slow growing and histologically are characterized as cysts with a stratified squamous epithelium demonstrating lack of a granular layer (trichilemmal keratinization) with bright red keratin contents and central focal calcification (Figure 2). Pilar cysts are more common in adult women and may be inherited through an autosomal-dominant pattern.1

Proliferating pilar cysts represent less than 3% of all pilar cysts.2 In addition to the characteristic features of a pilar cyst, proliferating pilar cysts generally are larger (can be >6-cm wide) and are more ulcerative.3 Histopathology of proliferating pilar cysts reveals a more extensive epithelial proliferation, yielding a rolls and scrolls appearance, and may demonstrate nuclear atypia.4 Proliferating pilar cysts classically manifest as large, raised, smooth and/or ulcerated nodules on the scalp accompanied by areas of excessive hair growth in older women. They generally arise from pre-existing pilar cysts but also may occur sporadically.4

The development of multiple proliferating pilar cysts has been observed in patients with KID syndrome, a rare congenital ectodermal disorder characterized by a triad of vascularizing keratitis, hyperkeratosis, and sensorineural deafness.5,6 It is caused by a missense mutation of the GJB2 gene encoding for connexin 26, a gap junction that facilitates intercellular signaling and is expressed in a variety of structures including the cochlea, cornea, sweat glands, and inner and outer root sheaths of hair follicles.7

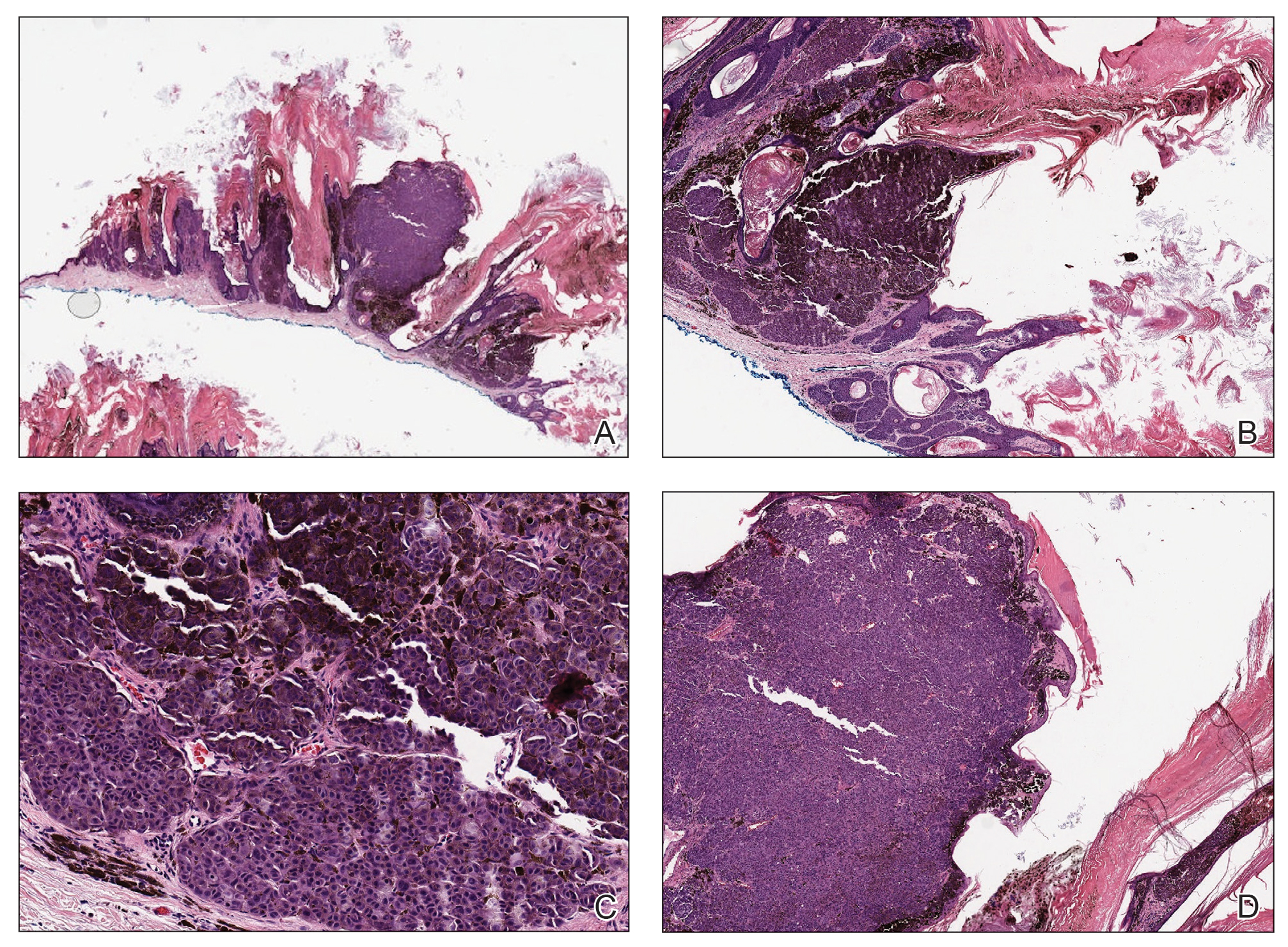

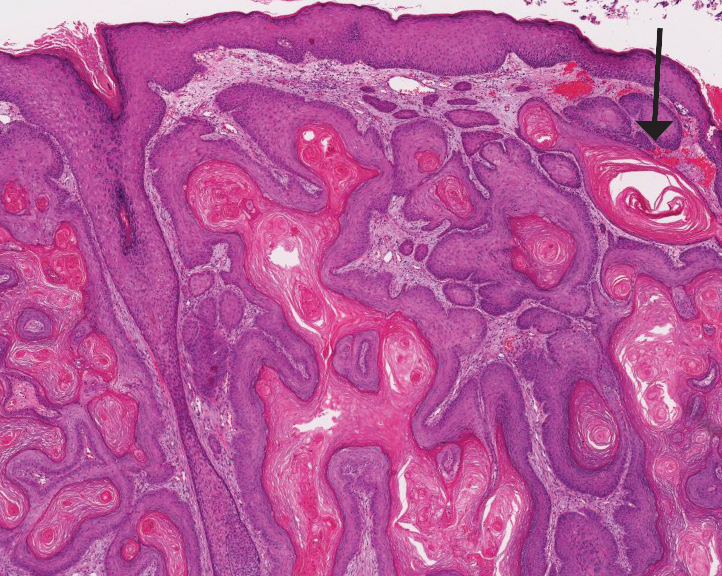

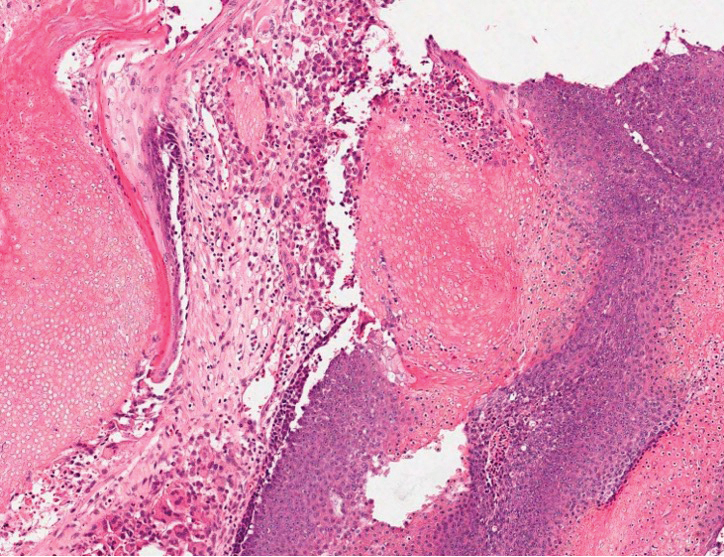

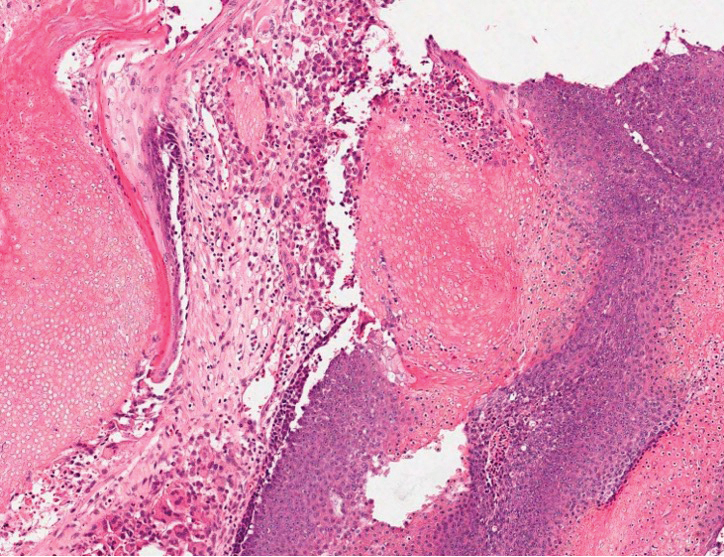

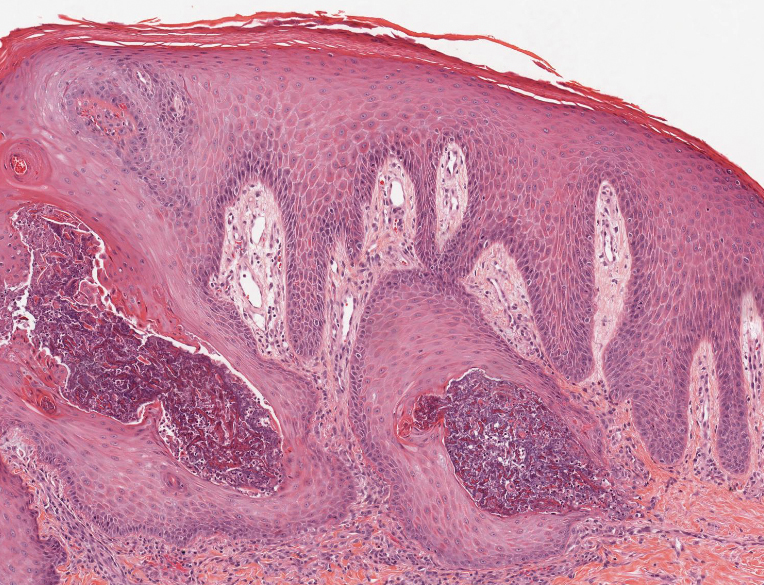

The differential diagnosis for proliferating pilar cysts includes pilomatrixomas, squamous cell carcinomas, and malignant proliferating pilar tumors. Pilomatrixomas (or calcifying epitheliomas of Malherbe) are the most common adnexal skin tumors in the pediatric population and most commonly present on the head, neck, and arms.8 They also can manifest in adults. Pilomatrixomas are benign dermal-subcutaneous tumors encapsulated by connective tissue that are found on the hair matrix and are histologically characterized by basaloid cells, shadow (or ghost) cells, dystrophic calcifications, and giant cells.9 The amount of basaloid cells and shadow cells can vary. Tumor progression results in the enucleation of the basaloid cells to form eosinophilic shadow cells in which calcification can occur. Giant cell granulomas may form contiguous with the calcifications. Both proliferating pilar cysts and pilomatrixomas have a rolls and scrolls appearance on low-power microscopy, but the latter are differentiated by their shadow cells and basaloid areas (Figure 3).

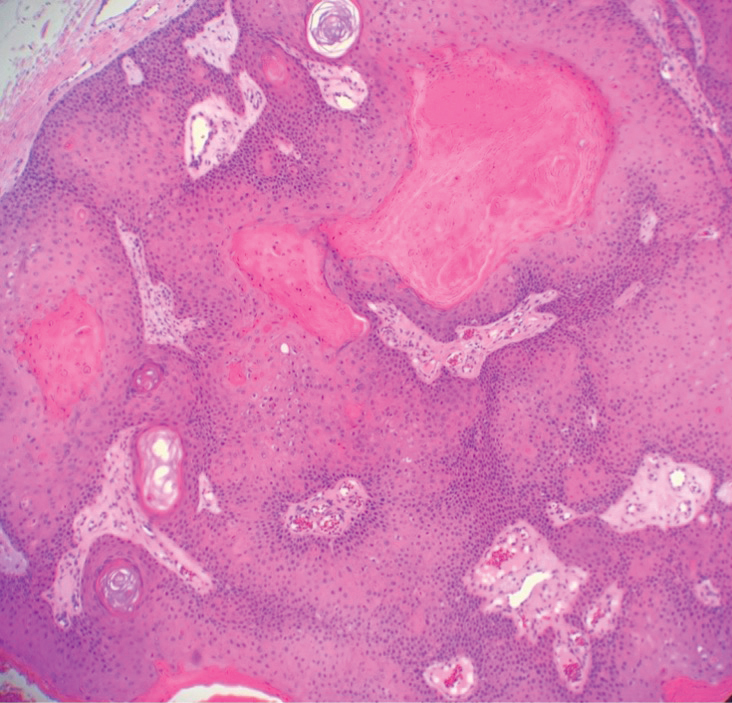

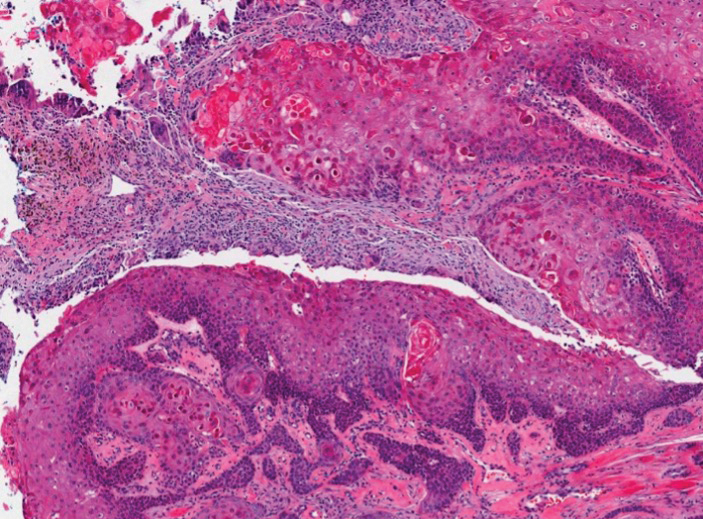

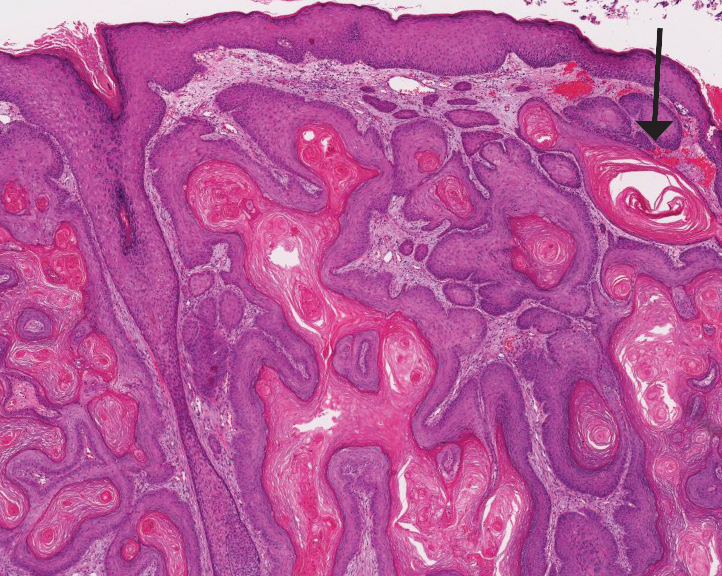

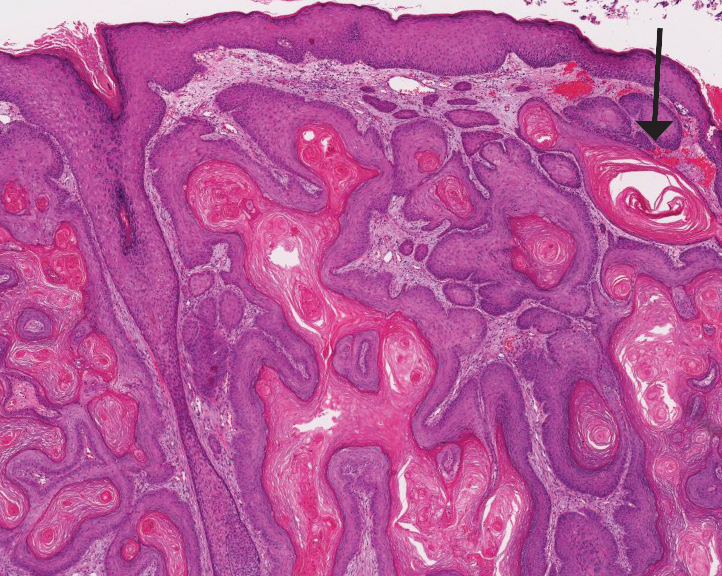

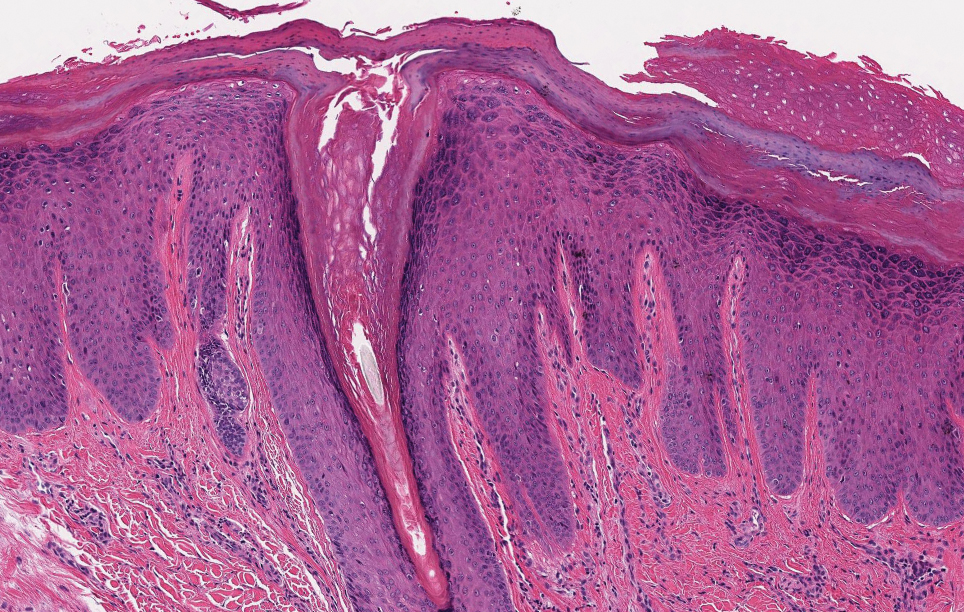

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common nonmelanoma skin cancer and more commonly affects men. Risk factors for SCC include immunosuppression and exposure to UV radiation. Histopathology of well-differentiated SCCs reveals invasive squamous cells with larger nuclei and a glassy appearance in addition to possible mitotic figures and keratin pearls (Figure 4). They typically manifest in sun-exposed areas such as the scalp, face, forearms, dorsal aspects of the hands, and lower legs.10 Proliferating pilar tumors often lack the nuclear atypia and invasive architecture of a well-differentiated SCC.

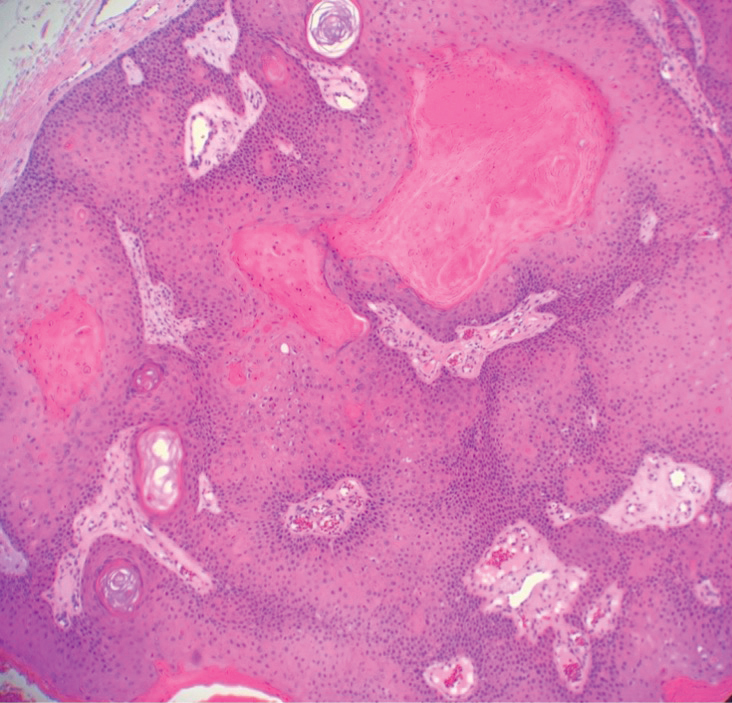

Features of malignant proliferating pilar tumors overlap with proliferating pilar cysts. In addition to the proliferative epithelium with abrupt trichilemmal keratinization that is typical of a proliferating pilar cyst, a malignant proliferating pilar tumor will demonstrate invasion into the surrounding tissue and lymph nodes, mitotic and architectural atypia, and necrosis (Figure 5).11 Malignant proliferating pilar tumors grow rapidly, ranging in size from 1 to 10 cm, and may develop from pre-existing or proliferating pilar cysts or de novo.

The development of multiple proliferating pilar cysts and thus increased risk for progression to malignant proliferating pilar tumors has been observed in patients with KID syndrome.6 Our case highlights the importance of early screening and recognition of proliferating pilar tumors in patients with this condition.

- Poiares Baptista A, Garcia E Silva L, Born MC. Proliferating trichilemmal cyst. J Cutan Pathol. 1983;10:178-187.

- Al Aboud DM, Yarrarapu SNS, Patel BC. Pilar cyst. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Kim UG, Kook DB, Kim TH, et al. Trichilemmal carcinoma from proliferating trichilemmal cyst on the posterior neck [published online March 25, 2017]. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2017;18:50-53. doi:10.7181/acfs.2017.18.1.50

- Folpe AL, Reisenauer AK, Mentzel T, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal tumors: clinicopathologic evaluation is a guide to biologic behavior. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:492-498.

- Alsabbagh M. Keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome: a comprehensive review of cutaneous and systemic manifestations. Pediatr Dermatol. 2023;40:19-27.

- Nyquist GG, Mumm C, Grau R, et al. Malignant proliferating pilar tumors arising in KID syndrome: a report of two patients. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:734-741.

- Richard G, Rouan F, Willoughby CE, et al. Missense mutations in GJB2 encoding connexin-26 cause the ectodermal dysplasia keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70: 1341-1348.

- Lee SI, Choi JH, Sung KY, et al. Proliferating pilar tumor of the cheek misdiagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma. Indian J Dermatol. 2022;67:207.

- Thompson LD. Pilomatricoma. Ear Nose Throat J. 2012;91:18-20.

- Waldman A, Schmults C. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:1-12.

- Cavanagh G, Negbenebor NA, Robinson-Bostom L, et al. Two cases of malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor (MPTT) and review of literature. R I Med J (2013). 2022;105:12-16.

The Diagnosis: Proliferating Pilar Cyst

Histopathology revealed an extensive lobulated epithelial proliferation in a characteristic “rolls and scrolls” pattern (Figure 1). This finding along with the patient’s prior diagnosis of keratitis-ichthyosisdeafness (KID) syndrome supported the diagnosis of a proliferating pilar cyst.

Pilar (or trichilemmal) cysts are common dermal cysts typically found on the outer root sheath of hair follicles. They clinically manifest as multiple yellow dome-shaped nodules without central puncta. They are slow growing and histologically are characterized as cysts with a stratified squamous epithelium demonstrating lack of a granular layer (trichilemmal keratinization) with bright red keratin contents and central focal calcification (Figure 2). Pilar cysts are more common in adult women and may be inherited through an autosomal-dominant pattern.1

Proliferating pilar cysts represent less than 3% of all pilar cysts.2 In addition to the characteristic features of a pilar cyst, proliferating pilar cysts generally are larger (can be >6-cm wide) and are more ulcerative.3 Histopathology of proliferating pilar cysts reveals a more extensive epithelial proliferation, yielding a rolls and scrolls appearance, and may demonstrate nuclear atypia.4 Proliferating pilar cysts classically manifest as large, raised, smooth and/or ulcerated nodules on the scalp accompanied by areas of excessive hair growth in older women. They generally arise from pre-existing pilar cysts but also may occur sporadically.4

The development of multiple proliferating pilar cysts has been observed in patients with KID syndrome, a rare congenital ectodermal disorder characterized by a triad of vascularizing keratitis, hyperkeratosis, and sensorineural deafness.5,6 It is caused by a missense mutation of the GJB2 gene encoding for connexin 26, a gap junction that facilitates intercellular signaling and is expressed in a variety of structures including the cochlea, cornea, sweat glands, and inner and outer root sheaths of hair follicles.7

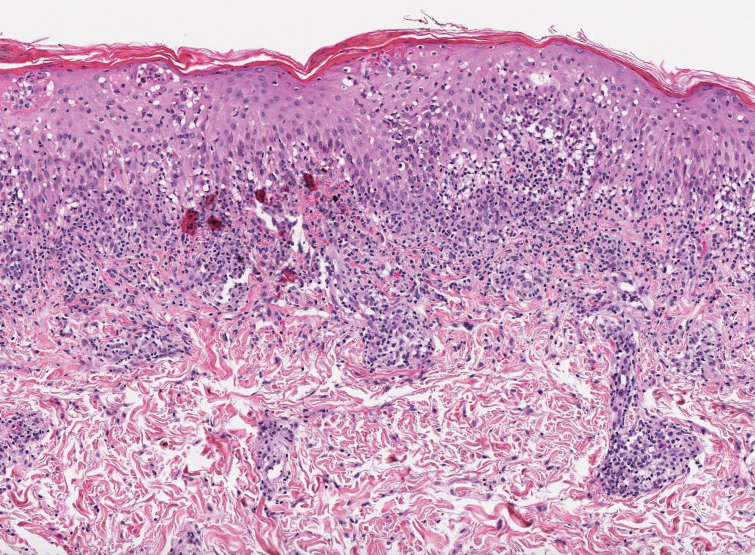

The differential diagnosis for proliferating pilar cysts includes pilomatrixomas, squamous cell carcinomas, and malignant proliferating pilar tumors. Pilomatrixomas (or calcifying epitheliomas of Malherbe) are the most common adnexal skin tumors in the pediatric population and most commonly present on the head, neck, and arms.8 They also can manifest in adults. Pilomatrixomas are benign dermal-subcutaneous tumors encapsulated by connective tissue that are found on the hair matrix and are histologically characterized by basaloid cells, shadow (or ghost) cells, dystrophic calcifications, and giant cells.9 The amount of basaloid cells and shadow cells can vary. Tumor progression results in the enucleation of the basaloid cells to form eosinophilic shadow cells in which calcification can occur. Giant cell granulomas may form contiguous with the calcifications. Both proliferating pilar cysts and pilomatrixomas have a rolls and scrolls appearance on low-power microscopy, but the latter are differentiated by their shadow cells and basaloid areas (Figure 3).

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common nonmelanoma skin cancer and more commonly affects men. Risk factors for SCC include immunosuppression and exposure to UV radiation. Histopathology of well-differentiated SCCs reveals invasive squamous cells with larger nuclei and a glassy appearance in addition to possible mitotic figures and keratin pearls (Figure 4). They typically manifest in sun-exposed areas such as the scalp, face, forearms, dorsal aspects of the hands, and lower legs.10 Proliferating pilar tumors often lack the nuclear atypia and invasive architecture of a well-differentiated SCC.

Features of malignant proliferating pilar tumors overlap with proliferating pilar cysts. In addition to the proliferative epithelium with abrupt trichilemmal keratinization that is typical of a proliferating pilar cyst, a malignant proliferating pilar tumor will demonstrate invasion into the surrounding tissue and lymph nodes, mitotic and architectural atypia, and necrosis (Figure 5).11 Malignant proliferating pilar tumors grow rapidly, ranging in size from 1 to 10 cm, and may develop from pre-existing or proliferating pilar cysts or de novo.

The development of multiple proliferating pilar cysts and thus increased risk for progression to malignant proliferating pilar tumors has been observed in patients with KID syndrome.6 Our case highlights the importance of early screening and recognition of proliferating pilar tumors in patients with this condition.

The Diagnosis: Proliferating Pilar Cyst

Histopathology revealed an extensive lobulated epithelial proliferation in a characteristic “rolls and scrolls” pattern (Figure 1). This finding along with the patient’s prior diagnosis of keratitis-ichthyosisdeafness (KID) syndrome supported the diagnosis of a proliferating pilar cyst.

Pilar (or trichilemmal) cysts are common dermal cysts typically found on the outer root sheath of hair follicles. They clinically manifest as multiple yellow dome-shaped nodules without central puncta. They are slow growing and histologically are characterized as cysts with a stratified squamous epithelium demonstrating lack of a granular layer (trichilemmal keratinization) with bright red keratin contents and central focal calcification (Figure 2). Pilar cysts are more common in adult women and may be inherited through an autosomal-dominant pattern.1

Proliferating pilar cysts represent less than 3% of all pilar cysts.2 In addition to the characteristic features of a pilar cyst, proliferating pilar cysts generally are larger (can be >6-cm wide) and are more ulcerative.3 Histopathology of proliferating pilar cysts reveals a more extensive epithelial proliferation, yielding a rolls and scrolls appearance, and may demonstrate nuclear atypia.4 Proliferating pilar cysts classically manifest as large, raised, smooth and/or ulcerated nodules on the scalp accompanied by areas of excessive hair growth in older women. They generally arise from pre-existing pilar cysts but also may occur sporadically.4

The development of multiple proliferating pilar cysts has been observed in patients with KID syndrome, a rare congenital ectodermal disorder characterized by a triad of vascularizing keratitis, hyperkeratosis, and sensorineural deafness.5,6 It is caused by a missense mutation of the GJB2 gene encoding for connexin 26, a gap junction that facilitates intercellular signaling and is expressed in a variety of structures including the cochlea, cornea, sweat glands, and inner and outer root sheaths of hair follicles.7

The differential diagnosis for proliferating pilar cysts includes pilomatrixomas, squamous cell carcinomas, and malignant proliferating pilar tumors. Pilomatrixomas (or calcifying epitheliomas of Malherbe) are the most common adnexal skin tumors in the pediatric population and most commonly present on the head, neck, and arms.8 They also can manifest in adults. Pilomatrixomas are benign dermal-subcutaneous tumors encapsulated by connective tissue that are found on the hair matrix and are histologically characterized by basaloid cells, shadow (or ghost) cells, dystrophic calcifications, and giant cells.9 The amount of basaloid cells and shadow cells can vary. Tumor progression results in the enucleation of the basaloid cells to form eosinophilic shadow cells in which calcification can occur. Giant cell granulomas may form contiguous with the calcifications. Both proliferating pilar cysts and pilomatrixomas have a rolls and scrolls appearance on low-power microscopy, but the latter are differentiated by their shadow cells and basaloid areas (Figure 3).

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common nonmelanoma skin cancer and more commonly affects men. Risk factors for SCC include immunosuppression and exposure to UV radiation. Histopathology of well-differentiated SCCs reveals invasive squamous cells with larger nuclei and a glassy appearance in addition to possible mitotic figures and keratin pearls (Figure 4). They typically manifest in sun-exposed areas such as the scalp, face, forearms, dorsal aspects of the hands, and lower legs.10 Proliferating pilar tumors often lack the nuclear atypia and invasive architecture of a well-differentiated SCC.

Features of malignant proliferating pilar tumors overlap with proliferating pilar cysts. In addition to the proliferative epithelium with abrupt trichilemmal keratinization that is typical of a proliferating pilar cyst, a malignant proliferating pilar tumor will demonstrate invasion into the surrounding tissue and lymph nodes, mitotic and architectural atypia, and necrosis (Figure 5).11 Malignant proliferating pilar tumors grow rapidly, ranging in size from 1 to 10 cm, and may develop from pre-existing or proliferating pilar cysts or de novo.

The development of multiple proliferating pilar cysts and thus increased risk for progression to malignant proliferating pilar tumors has been observed in patients with KID syndrome.6 Our case highlights the importance of early screening and recognition of proliferating pilar tumors in patients with this condition.

- Poiares Baptista A, Garcia E Silva L, Born MC. Proliferating trichilemmal cyst. J Cutan Pathol. 1983;10:178-187.

- Al Aboud DM, Yarrarapu SNS, Patel BC. Pilar cyst. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Kim UG, Kook DB, Kim TH, et al. Trichilemmal carcinoma from proliferating trichilemmal cyst on the posterior neck [published online March 25, 2017]. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2017;18:50-53. doi:10.7181/acfs.2017.18.1.50

- Folpe AL, Reisenauer AK, Mentzel T, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal tumors: clinicopathologic evaluation is a guide to biologic behavior. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:492-498.

- Alsabbagh M. Keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome: a comprehensive review of cutaneous and systemic manifestations. Pediatr Dermatol. 2023;40:19-27.

- Nyquist GG, Mumm C, Grau R, et al. Malignant proliferating pilar tumors arising in KID syndrome: a report of two patients. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:734-741.

- Richard G, Rouan F, Willoughby CE, et al. Missense mutations in GJB2 encoding connexin-26 cause the ectodermal dysplasia keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70: 1341-1348.

- Lee SI, Choi JH, Sung KY, et al. Proliferating pilar tumor of the cheek misdiagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma. Indian J Dermatol. 2022;67:207.

- Thompson LD. Pilomatricoma. Ear Nose Throat J. 2012;91:18-20.

- Waldman A, Schmults C. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:1-12.

- Cavanagh G, Negbenebor NA, Robinson-Bostom L, et al. Two cases of malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor (MPTT) and review of literature. R I Med J (2013). 2022;105:12-16.

- Poiares Baptista A, Garcia E Silva L, Born MC. Proliferating trichilemmal cyst. J Cutan Pathol. 1983;10:178-187.

- Al Aboud DM, Yarrarapu SNS, Patel BC. Pilar cyst. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Kim UG, Kook DB, Kim TH, et al. Trichilemmal carcinoma from proliferating trichilemmal cyst on the posterior neck [published online March 25, 2017]. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2017;18:50-53. doi:10.7181/acfs.2017.18.1.50

- Folpe AL, Reisenauer AK, Mentzel T, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal tumors: clinicopathologic evaluation is a guide to biologic behavior. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:492-498.

- Alsabbagh M. Keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome: a comprehensive review of cutaneous and systemic manifestations. Pediatr Dermatol. 2023;40:19-27.

- Nyquist GG, Mumm C, Grau R, et al. Malignant proliferating pilar tumors arising in KID syndrome: a report of two patients. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:734-741.

- Richard G, Rouan F, Willoughby CE, et al. Missense mutations in GJB2 encoding connexin-26 cause the ectodermal dysplasia keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70: 1341-1348.

- Lee SI, Choi JH, Sung KY, et al. Proliferating pilar tumor of the cheek misdiagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma. Indian J Dermatol. 2022;67:207.

- Thompson LD. Pilomatricoma. Ear Nose Throat J. 2012;91:18-20.

- Waldman A, Schmults C. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:1-12.

- Cavanagh G, Negbenebor NA, Robinson-Bostom L, et al. Two cases of malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor (MPTT) and review of literature. R I Med J (2013). 2022;105:12-16.

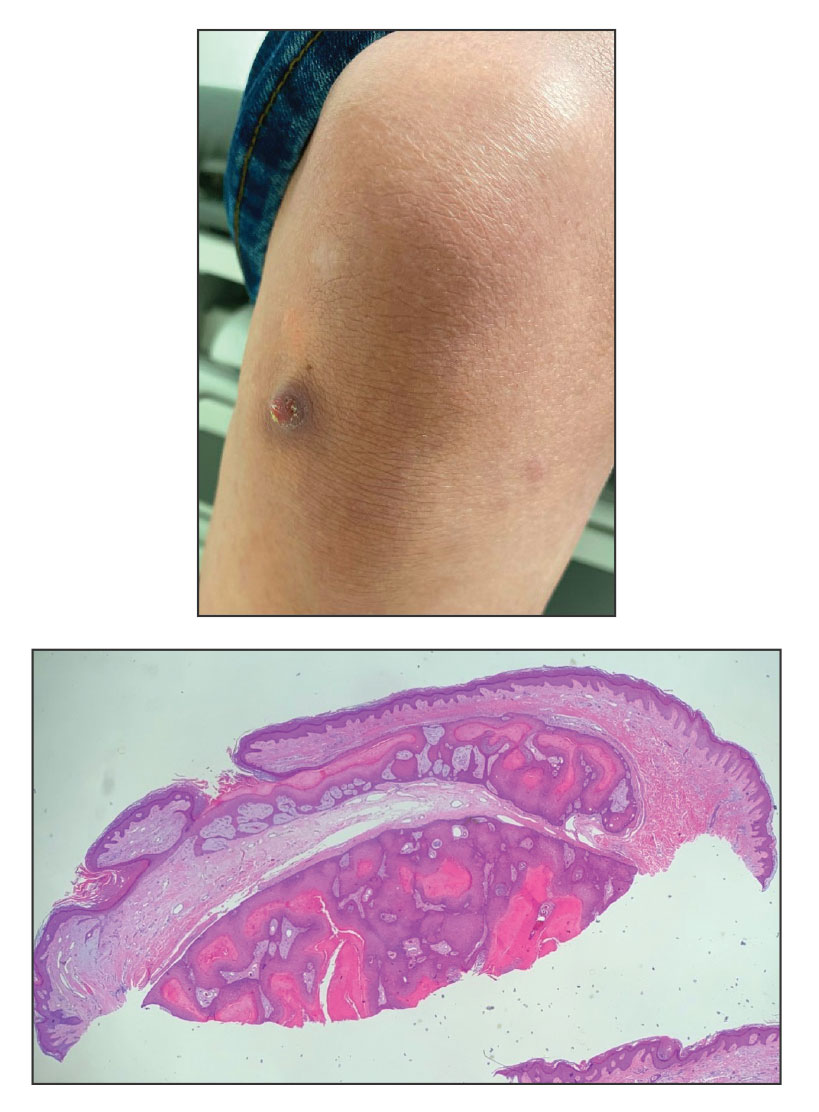

A 28-year-old man presented with an 8-mm, tender, mildly hyperkeratotic nodule on the right knee (top) of unknown duration. He had a history of mild keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness (KID) syndrome that was diagnosed based on the presence of congenital erythrokeratoderma, hearing issues identified at 2 years of age, palmoplantar keratoderma, keratitis, photophobia, chronic fungal nail infections, and alopecia and later was confirmed with a chromosome microarray for the GJB2 gene, which is associated with a connexin 26 mutation. A shave biopsy of the nodule was performed (bottom).

Keratotic Nodules in a Patient With End-Stage Renal Disease

The Diagnosis: Reactive Perforating Collagenosis

Reactive perforating collagenosis (RPC) is the most common type of primary perforating dermatosis and is characterized by the transepithelial elimination of collagen from the dermis. Although familial RPC usually presents in infancy or early childhood, the acquired form has a strong association with type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic renal disease. Up to 10% of hemodialysis patients develop RPC.1 Patients with RPC develop red-brown, umbilicated, papulonodular lesions, often with a central keratotic crust and erythematous halo. The lesions are variable in shape and size (typically up to 10 mm in diameter) and commonly are located on the trunk or extensor aspects of the limbs. Pruritus is the primary concern, and the Koebner phenomenon commonly is seen.2

Although the histopathology can vary depending on the stage of the lesion, an invaginating epidermal process with prominent epidermal hyperplasia surrounding a central plug of keratin, basophilic inflammatory debris, and degenerated collagen are findings indicative of RPC. At the base of the invagination, the altered collagen perforates through the epidermis by the process of transepidermal elimination.3 Trichrome stains can highlight the collagen, while Verhoeff–van Gieson staining is negative (no elastic fiber elimination). Anecdotal reports have described a variety of successful therapies including retinoids, allopurinol, doxycycline, dupilumab, and phototherapy, with phototherapy being especially effective in patients with coexistent renal disease.4-8 Our patient was started on dupilumab 300 mg every other week and triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily (Monday through Friday) for itchy areas. The efficacy of the treatment was to be assessed at the next visit.

Elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS) is a rare skin disease that presents as small papules arranged in serpiginous or annular patterns on the neck, face, arms, or other flexural areas in early adulthood. It more commonly is seen in males and can be associated with other inherited disorders such as Down syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and Marfan syndrome. In rare instances, EPS has been linked to D-penicillamine.9 Elastosis perforans serpiginosa is characterized by focal dermal elastosis and transepithelial elimination of abnormal elastic fibers instead of collagen. The formation of narrow channels extending upward from the dermis in straight or corkscrew patterns commonly is seen (Figure 1). The dermis also may contain a chronic inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, macrophages, or multinucleated giant cells.10 Verhoeff– van Gieson stain highlights the altered elastic fibers in the papillary dermis.

Prurigo nodularis involves chronic, intensely pruritic, lichenified, excoriated nodules that often present as grouped symmetric lesions predominantly on the extensor aspects of the distal extremities and occasionally the trunk. Histologically, prurigo nodularis appears similar to lichen simplex chronicus but in a nodular form with pronounced hyperkeratosis and acanthosis, sometimes to the degree of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Figure 2).11 Its features may resemble chronic eczema with mild spongiosis and focal parakeratosis. In the dermis, there is vascular hyperplasia surrounded by perivascular inflammatory infiltrates. Immunohistochemical staining for calcitonin gene-related peptide and substance P may show a large increase of immunoreactive nerves in the lesional skin of nodular prurigo patients compared to the lichenified skin of eczema patients.12 However, neural hyperplasia is not a diagnostic prerequisite in prurigo nodularis.13 Rarely, hyperplasic nerve trunks associated with Schwann cell proliferation may give rise to small neuromata that can be detected on electron microscopy.14 Screening for underlying systemic disease is recommended to rule out cancer, liver disease, chronic kidney disease, thyroid disorders, or HIV.

Ecthyma can affect children, adults, and especially immunocompromised patients at sites of trauma that allow entry of Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus. Histologically, there is ulceration of the epidermis with a thick overlying inflammatory crust (Figure 3). The heavy infiltrate of neutrophils in the reticular dermis forms the base of the ulcer, and gram-positive cocci may be detected within the inflammatory crust. Ecthyma lesions may resemble the excoriations and shallow ulcers that are seen in a variety of other pruritic conditions.15

Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta is a T-cell–mediated disease that is characterized by crops of lesions in varying sizes and stages including vesicular, hemorrhagic, ulcerated, and necrotic. It often results in varioliform scarring. Histologic findings can include parakeratosis, lichenoid inflammation, extravasation of red blood cells, vasculitis, and apoptotic keratinocytes (Figure 4).16

- Hong SB, Park JH, Ihm CG, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure and diabetes mellitus. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:283-288. doi:10.3346/jkms.2004.19.2.283

- Mullins TB, Sickinger M, Zito PM. Reactive perforating collagenosis. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Bejjanki H, Siroy AE, Koratala A. Reactive perforating collagenosis in end-stage renal disease: not all that itches is uremic pruritus! Am J Med. 2019;132:E658-E660. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.03.015

- Cullen SI. Successful treatment of reactive perforating collagenosis with tretinoin. Cutis. 1979;23:187-193.

- Tilz H, Becker JC, Legat F, et al. Allopurinol in the treatment of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:94-97. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962013000100012

- Brinkmeier T, Schaller J, Herbst RA, et al. Successful treatment of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis with doxycycline. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:393-395. doi:10.1080/000155502320624249

- Gil-Lianes J, Riquelme-McLoughlin C, Mascaró JM Jr. Reactive perforating collagenosis successfully treated with dupilumab. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:398-400. doi:10.1111/ajd.13874

- Gambichler T, Altmeyer P, Kreuter A. Treatment of acquired perforating dermatosis with narrowband ultraviolet B. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:363-364. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.08.018

- Na SY, Choi M, Kim MJ, et al. Penicillamine-induced elastosis perforans serpiginosa and cutis laxa in a patient with Wilson’s disease. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22:468-471. doi:10.5021/ad.2010.22.4.468

- Lee SH, Choi Y, Kim SC. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:103-106. doi:10.5021/ad.2014.26.1.103

- Weigelt N, Metze D, Ständer S. Prurigo nodularis: systematic analysis of 58 histological criteria in 136 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:578-586. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01484.x

- Abadía Molina F, Burrows NP, Jones RR, et al. Increased sensory neuropeptides in nodular prurigo: a quantitative immunohistochemical analysis. Br J Dermatol. 1992;127:344-351. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb00452.x

- Lindley RP, Payne CM. Neural hyperplasia is not a diagnostic prerequisite in nodular prurigo. a controlled morphometric microscopic study of 26 biopsy specimens. J Cutan Pathol. 1989;16:14-18. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1989.tb00003.x

- Feuerman EJ, Sandbank M. Prurigo nodularis. histological and electron microscopical study. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:1472-1477. doi:10.1001/archderm.111.11.1472

- Weedon D, ed. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone; 2010. 16. Clarey DD, Lauer SR, Trowbridge RM. Clinical, dermatoscopic, and histological findings in a diagnosis of pityriasis lichenoides [published online June 20, 2020]. Cureus. 2020;12:E8725. doi:10.7759 /cureus.8725

The Diagnosis: Reactive Perforating Collagenosis

Reactive perforating collagenosis (RPC) is the most common type of primary perforating dermatosis and is characterized by the transepithelial elimination of collagen from the dermis. Although familial RPC usually presents in infancy or early childhood, the acquired form has a strong association with type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic renal disease. Up to 10% of hemodialysis patients develop RPC.1 Patients with RPC develop red-brown, umbilicated, papulonodular lesions, often with a central keratotic crust and erythematous halo. The lesions are variable in shape and size (typically up to 10 mm in diameter) and commonly are located on the trunk or extensor aspects of the limbs. Pruritus is the primary concern, and the Koebner phenomenon commonly is seen.2

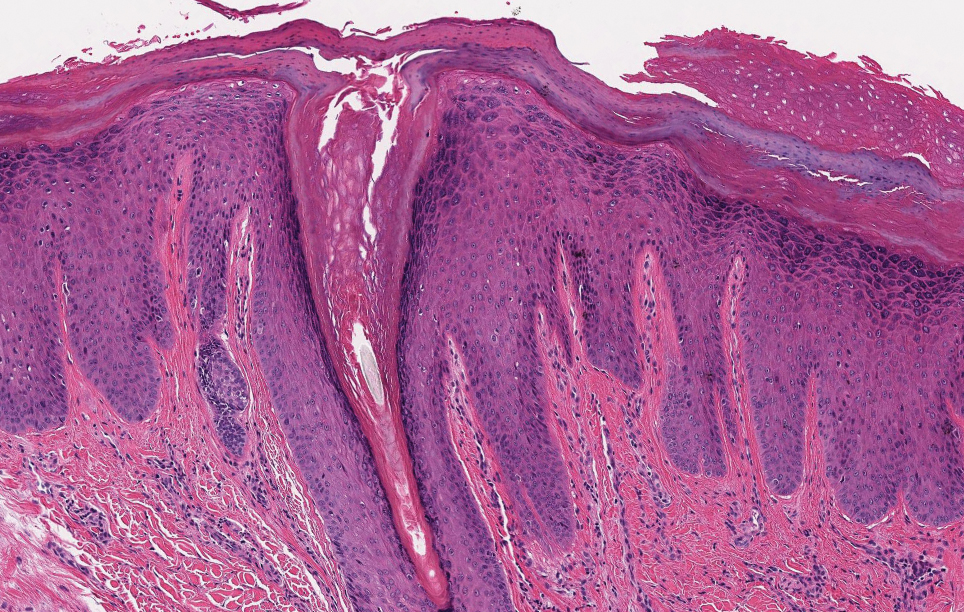

Although the histopathology can vary depending on the stage of the lesion, an invaginating epidermal process with prominent epidermal hyperplasia surrounding a central plug of keratin, basophilic inflammatory debris, and degenerated collagen are findings indicative of RPC. At the base of the invagination, the altered collagen perforates through the epidermis by the process of transepidermal elimination.3 Trichrome stains can highlight the collagen, while Verhoeff–van Gieson staining is negative (no elastic fiber elimination). Anecdotal reports have described a variety of successful therapies including retinoids, allopurinol, doxycycline, dupilumab, and phototherapy, with phototherapy being especially effective in patients with coexistent renal disease.4-8 Our patient was started on dupilumab 300 mg every other week and triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily (Monday through Friday) for itchy areas. The efficacy of the treatment was to be assessed at the next visit.

Elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS) is a rare skin disease that presents as small papules arranged in serpiginous or annular patterns on the neck, face, arms, or other flexural areas in early adulthood. It more commonly is seen in males and can be associated with other inherited disorders such as Down syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and Marfan syndrome. In rare instances, EPS has been linked to D-penicillamine.9 Elastosis perforans serpiginosa is characterized by focal dermal elastosis and transepithelial elimination of abnormal elastic fibers instead of collagen. The formation of narrow channels extending upward from the dermis in straight or corkscrew patterns commonly is seen (Figure 1). The dermis also may contain a chronic inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, macrophages, or multinucleated giant cells.10 Verhoeff– van Gieson stain highlights the altered elastic fibers in the papillary dermis.

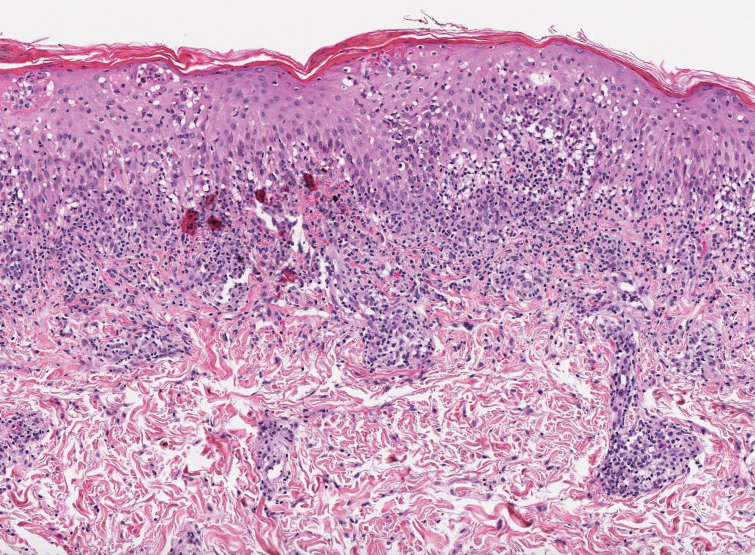

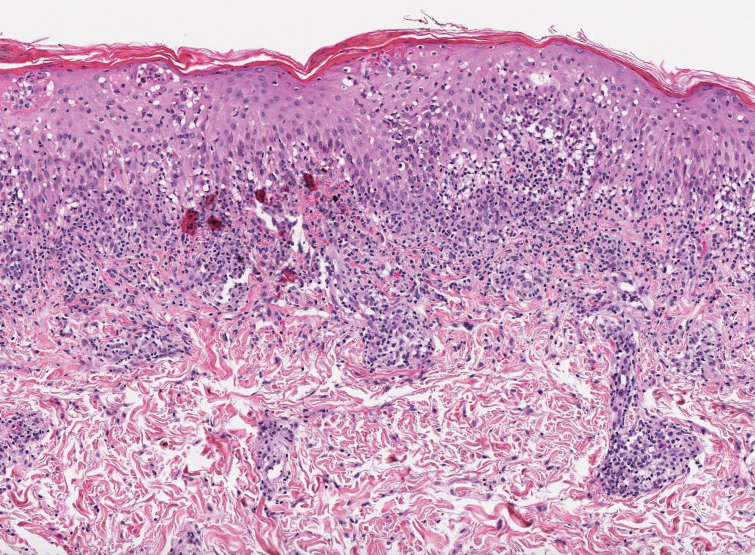

Prurigo nodularis involves chronic, intensely pruritic, lichenified, excoriated nodules that often present as grouped symmetric lesions predominantly on the extensor aspects of the distal extremities and occasionally the trunk. Histologically, prurigo nodularis appears similar to lichen simplex chronicus but in a nodular form with pronounced hyperkeratosis and acanthosis, sometimes to the degree of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Figure 2).11 Its features may resemble chronic eczema with mild spongiosis and focal parakeratosis. In the dermis, there is vascular hyperplasia surrounded by perivascular inflammatory infiltrates. Immunohistochemical staining for calcitonin gene-related peptide and substance P may show a large increase of immunoreactive nerves in the lesional skin of nodular prurigo patients compared to the lichenified skin of eczema patients.12 However, neural hyperplasia is not a diagnostic prerequisite in prurigo nodularis.13 Rarely, hyperplasic nerve trunks associated with Schwann cell proliferation may give rise to small neuromata that can be detected on electron microscopy.14 Screening for underlying systemic disease is recommended to rule out cancer, liver disease, chronic kidney disease, thyroid disorders, or HIV.

Ecthyma can affect children, adults, and especially immunocompromised patients at sites of trauma that allow entry of Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus. Histologically, there is ulceration of the epidermis with a thick overlying inflammatory crust (Figure 3). The heavy infiltrate of neutrophils in the reticular dermis forms the base of the ulcer, and gram-positive cocci may be detected within the inflammatory crust. Ecthyma lesions may resemble the excoriations and shallow ulcers that are seen in a variety of other pruritic conditions.15

Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta is a T-cell–mediated disease that is characterized by crops of lesions in varying sizes and stages including vesicular, hemorrhagic, ulcerated, and necrotic. It often results in varioliform scarring. Histologic findings can include parakeratosis, lichenoid inflammation, extravasation of red blood cells, vasculitis, and apoptotic keratinocytes (Figure 4).16

The Diagnosis: Reactive Perforating Collagenosis

Reactive perforating collagenosis (RPC) is the most common type of primary perforating dermatosis and is characterized by the transepithelial elimination of collagen from the dermis. Although familial RPC usually presents in infancy or early childhood, the acquired form has a strong association with type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic renal disease. Up to 10% of hemodialysis patients develop RPC.1 Patients with RPC develop red-brown, umbilicated, papulonodular lesions, often with a central keratotic crust and erythematous halo. The lesions are variable in shape and size (typically up to 10 mm in diameter) and commonly are located on the trunk or extensor aspects of the limbs. Pruritus is the primary concern, and the Koebner phenomenon commonly is seen.2

Although the histopathology can vary depending on the stage of the lesion, an invaginating epidermal process with prominent epidermal hyperplasia surrounding a central plug of keratin, basophilic inflammatory debris, and degenerated collagen are findings indicative of RPC. At the base of the invagination, the altered collagen perforates through the epidermis by the process of transepidermal elimination.3 Trichrome stains can highlight the collagen, while Verhoeff–van Gieson staining is negative (no elastic fiber elimination). Anecdotal reports have described a variety of successful therapies including retinoids, allopurinol, doxycycline, dupilumab, and phototherapy, with phototherapy being especially effective in patients with coexistent renal disease.4-8 Our patient was started on dupilumab 300 mg every other week and triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily (Monday through Friday) for itchy areas. The efficacy of the treatment was to be assessed at the next visit.

Elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS) is a rare skin disease that presents as small papules arranged in serpiginous or annular patterns on the neck, face, arms, or other flexural areas in early adulthood. It more commonly is seen in males and can be associated with other inherited disorders such as Down syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and Marfan syndrome. In rare instances, EPS has been linked to D-penicillamine.9 Elastosis perforans serpiginosa is characterized by focal dermal elastosis and transepithelial elimination of abnormal elastic fibers instead of collagen. The formation of narrow channels extending upward from the dermis in straight or corkscrew patterns commonly is seen (Figure 1). The dermis also may contain a chronic inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, macrophages, or multinucleated giant cells.10 Verhoeff– van Gieson stain highlights the altered elastic fibers in the papillary dermis.

Prurigo nodularis involves chronic, intensely pruritic, lichenified, excoriated nodules that often present as grouped symmetric lesions predominantly on the extensor aspects of the distal extremities and occasionally the trunk. Histologically, prurigo nodularis appears similar to lichen simplex chronicus but in a nodular form with pronounced hyperkeratosis and acanthosis, sometimes to the degree of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Figure 2).11 Its features may resemble chronic eczema with mild spongiosis and focal parakeratosis. In the dermis, there is vascular hyperplasia surrounded by perivascular inflammatory infiltrates. Immunohistochemical staining for calcitonin gene-related peptide and substance P may show a large increase of immunoreactive nerves in the lesional skin of nodular prurigo patients compared to the lichenified skin of eczema patients.12 However, neural hyperplasia is not a diagnostic prerequisite in prurigo nodularis.13 Rarely, hyperplasic nerve trunks associated with Schwann cell proliferation may give rise to small neuromata that can be detected on electron microscopy.14 Screening for underlying systemic disease is recommended to rule out cancer, liver disease, chronic kidney disease, thyroid disorders, or HIV.

Ecthyma can affect children, adults, and especially immunocompromised patients at sites of trauma that allow entry of Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus. Histologically, there is ulceration of the epidermis with a thick overlying inflammatory crust (Figure 3). The heavy infiltrate of neutrophils in the reticular dermis forms the base of the ulcer, and gram-positive cocci may be detected within the inflammatory crust. Ecthyma lesions may resemble the excoriations and shallow ulcers that are seen in a variety of other pruritic conditions.15

Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta is a T-cell–mediated disease that is characterized by crops of lesions in varying sizes and stages including vesicular, hemorrhagic, ulcerated, and necrotic. It often results in varioliform scarring. Histologic findings can include parakeratosis, lichenoid inflammation, extravasation of red blood cells, vasculitis, and apoptotic keratinocytes (Figure 4).16

- Hong SB, Park JH, Ihm CG, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure and diabetes mellitus. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:283-288. doi:10.3346/jkms.2004.19.2.283

- Mullins TB, Sickinger M, Zito PM. Reactive perforating collagenosis. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Bejjanki H, Siroy AE, Koratala A. Reactive perforating collagenosis in end-stage renal disease: not all that itches is uremic pruritus! Am J Med. 2019;132:E658-E660. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.03.015

- Cullen SI. Successful treatment of reactive perforating collagenosis with tretinoin. Cutis. 1979;23:187-193.

- Tilz H, Becker JC, Legat F, et al. Allopurinol in the treatment of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:94-97. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962013000100012

- Brinkmeier T, Schaller J, Herbst RA, et al. Successful treatment of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis with doxycycline. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:393-395. doi:10.1080/000155502320624249

- Gil-Lianes J, Riquelme-McLoughlin C, Mascaró JM Jr. Reactive perforating collagenosis successfully treated with dupilumab. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:398-400. doi:10.1111/ajd.13874

- Gambichler T, Altmeyer P, Kreuter A. Treatment of acquired perforating dermatosis with narrowband ultraviolet B. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:363-364. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.08.018

- Na SY, Choi M, Kim MJ, et al. Penicillamine-induced elastosis perforans serpiginosa and cutis laxa in a patient with Wilson’s disease. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22:468-471. doi:10.5021/ad.2010.22.4.468

- Lee SH, Choi Y, Kim SC. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:103-106. doi:10.5021/ad.2014.26.1.103

- Weigelt N, Metze D, Ständer S. Prurigo nodularis: systematic analysis of 58 histological criteria in 136 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:578-586. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01484.x

- Abadía Molina F, Burrows NP, Jones RR, et al. Increased sensory neuropeptides in nodular prurigo: a quantitative immunohistochemical analysis. Br J Dermatol. 1992;127:344-351. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb00452.x

- Lindley RP, Payne CM. Neural hyperplasia is not a diagnostic prerequisite in nodular prurigo. a controlled morphometric microscopic study of 26 biopsy specimens. J Cutan Pathol. 1989;16:14-18. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1989.tb00003.x

- Feuerman EJ, Sandbank M. Prurigo nodularis. histological and electron microscopical study. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:1472-1477. doi:10.1001/archderm.111.11.1472

- Weedon D, ed. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone; 2010. 16. Clarey DD, Lauer SR, Trowbridge RM. Clinical, dermatoscopic, and histological findings in a diagnosis of pityriasis lichenoides [published online June 20, 2020]. Cureus. 2020;12:E8725. doi:10.7759 /cureus.8725

- Hong SB, Park JH, Ihm CG, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure and diabetes mellitus. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:283-288. doi:10.3346/jkms.2004.19.2.283

- Mullins TB, Sickinger M, Zito PM. Reactive perforating collagenosis. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Bejjanki H, Siroy AE, Koratala A. Reactive perforating collagenosis in end-stage renal disease: not all that itches is uremic pruritus! Am J Med. 2019;132:E658-E660. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.03.015

- Cullen SI. Successful treatment of reactive perforating collagenosis with tretinoin. Cutis. 1979;23:187-193.

- Tilz H, Becker JC, Legat F, et al. Allopurinol in the treatment of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:94-97. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962013000100012

- Brinkmeier T, Schaller J, Herbst RA, et al. Successful treatment of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis with doxycycline. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:393-395. doi:10.1080/000155502320624249

- Gil-Lianes J, Riquelme-McLoughlin C, Mascaró JM Jr. Reactive perforating collagenosis successfully treated with dupilumab. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:398-400. doi:10.1111/ajd.13874

- Gambichler T, Altmeyer P, Kreuter A. Treatment of acquired perforating dermatosis with narrowband ultraviolet B. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:363-364. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.08.018

- Na SY, Choi M, Kim MJ, et al. Penicillamine-induced elastosis perforans serpiginosa and cutis laxa in a patient with Wilson’s disease. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22:468-471. doi:10.5021/ad.2010.22.4.468

- Lee SH, Choi Y, Kim SC. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:103-106. doi:10.5021/ad.2014.26.1.103

- Weigelt N, Metze D, Ständer S. Prurigo nodularis: systematic analysis of 58 histological criteria in 136 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:578-586. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01484.x

- Abadía Molina F, Burrows NP, Jones RR, et al. Increased sensory neuropeptides in nodular prurigo: a quantitative immunohistochemical analysis. Br J Dermatol. 1992;127:344-351. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb00452.x

- Lindley RP, Payne CM. Neural hyperplasia is not a diagnostic prerequisite in nodular prurigo. a controlled morphometric microscopic study of 26 biopsy specimens. J Cutan Pathol. 1989;16:14-18. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1989.tb00003.x

- Feuerman EJ, Sandbank M. Prurigo nodularis. histological and electron microscopical study. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:1472-1477. doi:10.1001/archderm.111.11.1472

- Weedon D, ed. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone; 2010. 16. Clarey DD, Lauer SR, Trowbridge RM. Clinical, dermatoscopic, and histological findings in a diagnosis of pityriasis lichenoides [published online June 20, 2020]. Cureus. 2020;12:E8725. doi:10.7759 /cureus.8725

A 42-year-old man with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis presented with generalized body itching and nodules on the scalp and back of 1 year’s duration. Physical examination revealed diffuse, hyperpigmented, pruritic, keratotic nodules and macules on the scalp and back (top). A punch biopsy was performed (bottom).

Dermatopathology Etiquette 101

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has established core competencies to serve as a foundation for the training received in a dermatology residency program.1 Although programs are required to have the same concentrations—patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice—no specific guidelines are in place regarding how each of these competencies should be reached within a training period.2 Instead, it remains the responsibility of each program to formulate an individualized curriculum to facilitate proficiency in the multiple areas encompassed by a residency.

In many dermatology residency programs, dermatopathology is a substantial component of educational objectives and the curriculum.1 Residents may spend as much as 25% of their training on dermatopathology. However, there is great variability among programs in methods of teaching dermatopathology. When Hinshaw3 surveyed 52 of 109 dermatology residency programs, they identified differences in dermatopathology teaching that included, but was not limited to, utilization of problem-based learning (in 40.4% of programs), integration of journal reviews (53.8%), and computer-based learning (19.2%). In addition, differences were identified in the recommended primary textbook and the makeup of faculty who taught dermatopathology.3

Although residency programs vary in their methods of teaching this important component of dermatology, most use a multiheaded microscope in some capacity for didactics or sign-out. For most trainees, the dermatopathology laboratory is a new environment compared to the clinical space that medical students and residents become accustomed to throughout their education, thus creating a knowledge gap for trainees on proper dermatopathology etiquette and universal guidelines.

With medical students, residents, and fellows in mind, we have prepared a basic “dermatopathology etiquette” reference for trainees. Just as there are universal rules in the operating room for surgery (eg, sterile technique), we want to establish a code of conduct at the microscope. We hope that these 10 tips will, first, be useful to those who are unsure how to approach their first experience with dermatopathology and, second, serve as a guideline to aid development of appropriate communication skills and functioning within this novel setting. This list also can serve as a resource for dermatopathology attendings to provide to rotating residents and students.

1. New to pathology? It’s okay to ask. Do not hesitate to ask upper-year residents, fellows, and attendings for instructions on such matters as how to adjust your eyepiece to get the best resolution.

2. If a slide drops on the floor, do not move! Your first instinct might be to move your chair to look for the dropped slide, but you might roll over it and break it.

3. When the attending is looking through the scope, you look through the scope. Dermatopathology is a visual exercise. Getting in your “optic mileage” is best done under the guidance of an experienced dermatopathologist.

4. Rules regarding food and drink at the microscope vary by pathologist. It’s best to ask what each attending prefers. Safe advice is to avoid foods that make noise, such as chewing gum and chips, and food that has a strong odor, such as microwaved leftovers.

5. Limit use of a laptop, cell phone, and smartwatch. If you think that using any of these is necessary, it generally is best to announce that you are looking up something related to the case and then share your findings (but not the most recent post on your Facebook News Feed).

6. If you notice that something needs correcting on the report, speak up! We are all human; we all make typos. Do not hesitate to mention this as soon as possible, especially before the case is signed out. You will likely be thanked by your attending because it is harder to rectify once the report has been signed out.

7. Small talk often is welcome during large excisions. This is a great time to ask what others are doing next weekend or what happened in clinic earlier that day, or just to tell a good (clean) joke that is making the rounds. Conversely, if the case is complex, it often is best to wait until it is completed before asking questions.

8. When participating in a roundtable diagnosis, you are welcome to directly state the diagnosis for bread-and-butter cases, such as basal cell carcinomas and seborrheic keratoses. It is appropriate to be more descriptive and methodical in more complex cases. When evaluating a rash, give the general inflammatory pattern first. For example, is it spongiotic? Psoriasiform? Interface? Or a mixed pattern?

9. Extra points for identifying special sites! These include mucosal, genital, and acral sites. You might even get bonus points if you can determine something about the patient (child or adult) based on the pathologic features, such as variation in collagen patterns.

10. Whenever you are in doubt, just describe what you see. You can use the traditional top-down approach or start with stating the most evident finding, then proceed to a top-down description. If it is a neoplasm, describe the overall architecture; then, what you see at a cellular level will get you some points as well.

We acknowledge that this list of 10 tips is not comprehensive and might vary by attending and each institution’s distinctive training format. We are hopeful, however, that these 10 points of etiquette can serve as a guideline.

- Hinshaw M, Hsu P, Lee L-Y, et al. The current state of dermatopathology education: a survey of the Association of Professors of Dermatology. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:620-628. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2008.01128.x

- Hinshaw MA, Stratman EJ. Core competencies in dermatopathology. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:160-165. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2006.00442.x

- Hinshaw MA. Dermatopathology education: an update. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:815-826. doi:10.1016/j.det.2012.06.003

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has established core competencies to serve as a foundation for the training received in a dermatology residency program.1 Although programs are required to have the same concentrations—patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice—no specific guidelines are in place regarding how each of these competencies should be reached within a training period.2 Instead, it remains the responsibility of each program to formulate an individualized curriculum to facilitate proficiency in the multiple areas encompassed by a residency.

In many dermatology residency programs, dermatopathology is a substantial component of educational objectives and the curriculum.1 Residents may spend as much as 25% of their training on dermatopathology. However, there is great variability among programs in methods of teaching dermatopathology. When Hinshaw3 surveyed 52 of 109 dermatology residency programs, they identified differences in dermatopathology teaching that included, but was not limited to, utilization of problem-based learning (in 40.4% of programs), integration of journal reviews (53.8%), and computer-based learning (19.2%). In addition, differences were identified in the recommended primary textbook and the makeup of faculty who taught dermatopathology.3

Although residency programs vary in their methods of teaching this important component of dermatology, most use a multiheaded microscope in some capacity for didactics or sign-out. For most trainees, the dermatopathology laboratory is a new environment compared to the clinical space that medical students and residents become accustomed to throughout their education, thus creating a knowledge gap for trainees on proper dermatopathology etiquette and universal guidelines.

With medical students, residents, and fellows in mind, we have prepared a basic “dermatopathology etiquette” reference for trainees. Just as there are universal rules in the operating room for surgery (eg, sterile technique), we want to establish a code of conduct at the microscope. We hope that these 10 tips will, first, be useful to those who are unsure how to approach their first experience with dermatopathology and, second, serve as a guideline to aid development of appropriate communication skills and functioning within this novel setting. This list also can serve as a resource for dermatopathology attendings to provide to rotating residents and students.

1. New to pathology? It’s okay to ask. Do not hesitate to ask upper-year residents, fellows, and attendings for instructions on such matters as how to adjust your eyepiece to get the best resolution.

2. If a slide drops on the floor, do not move! Your first instinct might be to move your chair to look for the dropped slide, but you might roll over it and break it.

3. When the attending is looking through the scope, you look through the scope. Dermatopathology is a visual exercise. Getting in your “optic mileage” is best done under the guidance of an experienced dermatopathologist.

4. Rules regarding food and drink at the microscope vary by pathologist. It’s best to ask what each attending prefers. Safe advice is to avoid foods that make noise, such as chewing gum and chips, and food that has a strong odor, such as microwaved leftovers.

5. Limit use of a laptop, cell phone, and smartwatch. If you think that using any of these is necessary, it generally is best to announce that you are looking up something related to the case and then share your findings (but not the most recent post on your Facebook News Feed).

6. If you notice that something needs correcting on the report, speak up! We are all human; we all make typos. Do not hesitate to mention this as soon as possible, especially before the case is signed out. You will likely be thanked by your attending because it is harder to rectify once the report has been signed out.

7. Small talk often is welcome during large excisions. This is a great time to ask what others are doing next weekend or what happened in clinic earlier that day, or just to tell a good (clean) joke that is making the rounds. Conversely, if the case is complex, it often is best to wait until it is completed before asking questions.

8. When participating in a roundtable diagnosis, you are welcome to directly state the diagnosis for bread-and-butter cases, such as basal cell carcinomas and seborrheic keratoses. It is appropriate to be more descriptive and methodical in more complex cases. When evaluating a rash, give the general inflammatory pattern first. For example, is it spongiotic? Psoriasiform? Interface? Or a mixed pattern?

9. Extra points for identifying special sites! These include mucosal, genital, and acral sites. You might even get bonus points if you can determine something about the patient (child or adult) based on the pathologic features, such as variation in collagen patterns.

10. Whenever you are in doubt, just describe what you see. You can use the traditional top-down approach or start with stating the most evident finding, then proceed to a top-down description. If it is a neoplasm, describe the overall architecture; then, what you see at a cellular level will get you some points as well.

We acknowledge that this list of 10 tips is not comprehensive and might vary by attending and each institution’s distinctive training format. We are hopeful, however, that these 10 points of etiquette can serve as a guideline.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has established core competencies to serve as a foundation for the training received in a dermatology residency program.1 Although programs are required to have the same concentrations—patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice—no specific guidelines are in place regarding how each of these competencies should be reached within a training period.2 Instead, it remains the responsibility of each program to formulate an individualized curriculum to facilitate proficiency in the multiple areas encompassed by a residency.

In many dermatology residency programs, dermatopathology is a substantial component of educational objectives and the curriculum.1 Residents may spend as much as 25% of their training on dermatopathology. However, there is great variability among programs in methods of teaching dermatopathology. When Hinshaw3 surveyed 52 of 109 dermatology residency programs, they identified differences in dermatopathology teaching that included, but was not limited to, utilization of problem-based learning (in 40.4% of programs), integration of journal reviews (53.8%), and computer-based learning (19.2%). In addition, differences were identified in the recommended primary textbook and the makeup of faculty who taught dermatopathology.3

Although residency programs vary in their methods of teaching this important component of dermatology, most use a multiheaded microscope in some capacity for didactics or sign-out. For most trainees, the dermatopathology laboratory is a new environment compared to the clinical space that medical students and residents become accustomed to throughout their education, thus creating a knowledge gap for trainees on proper dermatopathology etiquette and universal guidelines.

With medical students, residents, and fellows in mind, we have prepared a basic “dermatopathology etiquette” reference for trainees. Just as there are universal rules in the operating room for surgery (eg, sterile technique), we want to establish a code of conduct at the microscope. We hope that these 10 tips will, first, be useful to those who are unsure how to approach their first experience with dermatopathology and, second, serve as a guideline to aid development of appropriate communication skills and functioning within this novel setting. This list also can serve as a resource for dermatopathology attendings to provide to rotating residents and students.

1. New to pathology? It’s okay to ask. Do not hesitate to ask upper-year residents, fellows, and attendings for instructions on such matters as how to adjust your eyepiece to get the best resolution.

2. If a slide drops on the floor, do not move! Your first instinct might be to move your chair to look for the dropped slide, but you might roll over it and break it.

3. When the attending is looking through the scope, you look through the scope. Dermatopathology is a visual exercise. Getting in your “optic mileage” is best done under the guidance of an experienced dermatopathologist.

4. Rules regarding food and drink at the microscope vary by pathologist. It’s best to ask what each attending prefers. Safe advice is to avoid foods that make noise, such as chewing gum and chips, and food that has a strong odor, such as microwaved leftovers.

5. Limit use of a laptop, cell phone, and smartwatch. If you think that using any of these is necessary, it generally is best to announce that you are looking up something related to the case and then share your findings (but not the most recent post on your Facebook News Feed).

6. If you notice that something needs correcting on the report, speak up! We are all human; we all make typos. Do not hesitate to mention this as soon as possible, especially before the case is signed out. You will likely be thanked by your attending because it is harder to rectify once the report has been signed out.

7. Small talk often is welcome during large excisions. This is a great time to ask what others are doing next weekend or what happened in clinic earlier that day, or just to tell a good (clean) joke that is making the rounds. Conversely, if the case is complex, it often is best to wait until it is completed before asking questions.

8. When participating in a roundtable diagnosis, you are welcome to directly state the diagnosis for bread-and-butter cases, such as basal cell carcinomas and seborrheic keratoses. It is appropriate to be more descriptive and methodical in more complex cases. When evaluating a rash, give the general inflammatory pattern first. For example, is it spongiotic? Psoriasiform? Interface? Or a mixed pattern?

9. Extra points for identifying special sites! These include mucosal, genital, and acral sites. You might even get bonus points if you can determine something about the patient (child or adult) based on the pathologic features, such as variation in collagen patterns.

10. Whenever you are in doubt, just describe what you see. You can use the traditional top-down approach or start with stating the most evident finding, then proceed to a top-down description. If it is a neoplasm, describe the overall architecture; then, what you see at a cellular level will get you some points as well.

We acknowledge that this list of 10 tips is not comprehensive and might vary by attending and each institution’s distinctive training format. We are hopeful, however, that these 10 points of etiquette can serve as a guideline.

- Hinshaw M, Hsu P, Lee L-Y, et al. The current state of dermatopathology education: a survey of the Association of Professors of Dermatology. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:620-628. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2008.01128.x

- Hinshaw MA, Stratman EJ. Core competencies in dermatopathology. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:160-165. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2006.00442.x

- Hinshaw MA. Dermatopathology education: an update. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:815-826. doi:10.1016/j.det.2012.06.003

- Hinshaw M, Hsu P, Lee L-Y, et al. The current state of dermatopathology education: a survey of the Association of Professors of Dermatology. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:620-628. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2008.01128.x

- Hinshaw MA, Stratman EJ. Core competencies in dermatopathology. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:160-165. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2006.00442.x

- Hinshaw MA. Dermatopathology education: an update. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:815-826. doi:10.1016/j.det.2012.06.003

Dark Brown Hyperkeratotic Nodule on the Back

The Diagnosis: Seborrheic Keratosis-like Melanoma

Seborrheic keratosis (SK) is a benign neoplasm commonly encountered on the skin and frequently diagnosed by clinical examination alone. Seborrheic keratosis-like melanomas are melanomas that clinically or dermatoscopically resemble SKs and thus can be challenging to accurately diagnose. Melanomas can have a hyperkeratotic or verrucous appearance1-3 and can even exhibit dermatoscopic and microscopic features that are found in SKs such as comedolike openings and milialike cysts as well as acanthosis and pseudohorn cysts, respectively.2

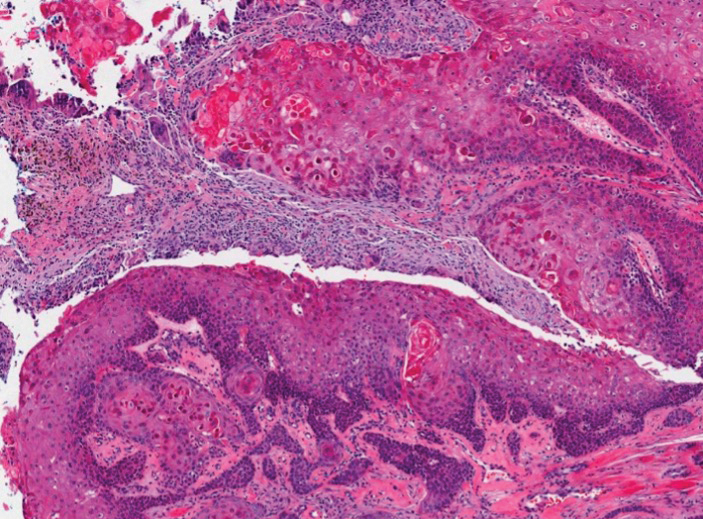

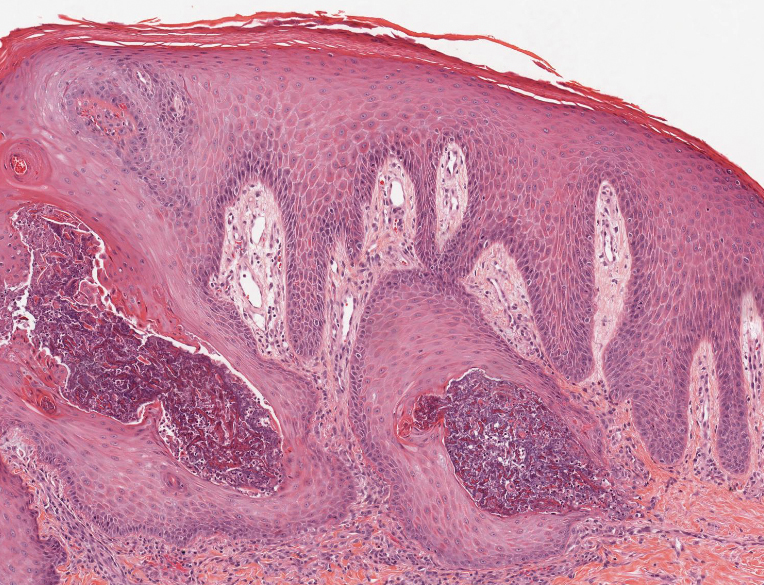

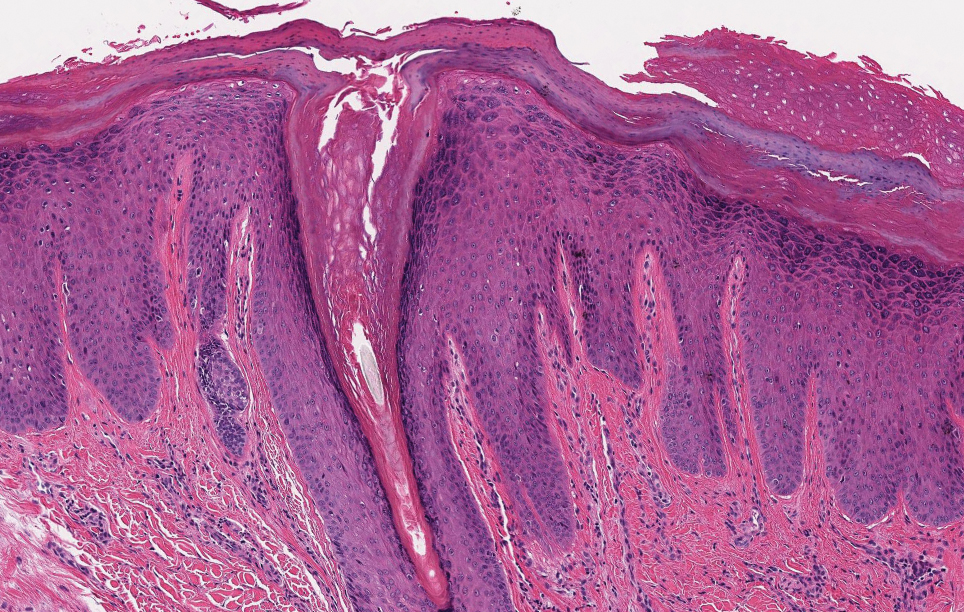

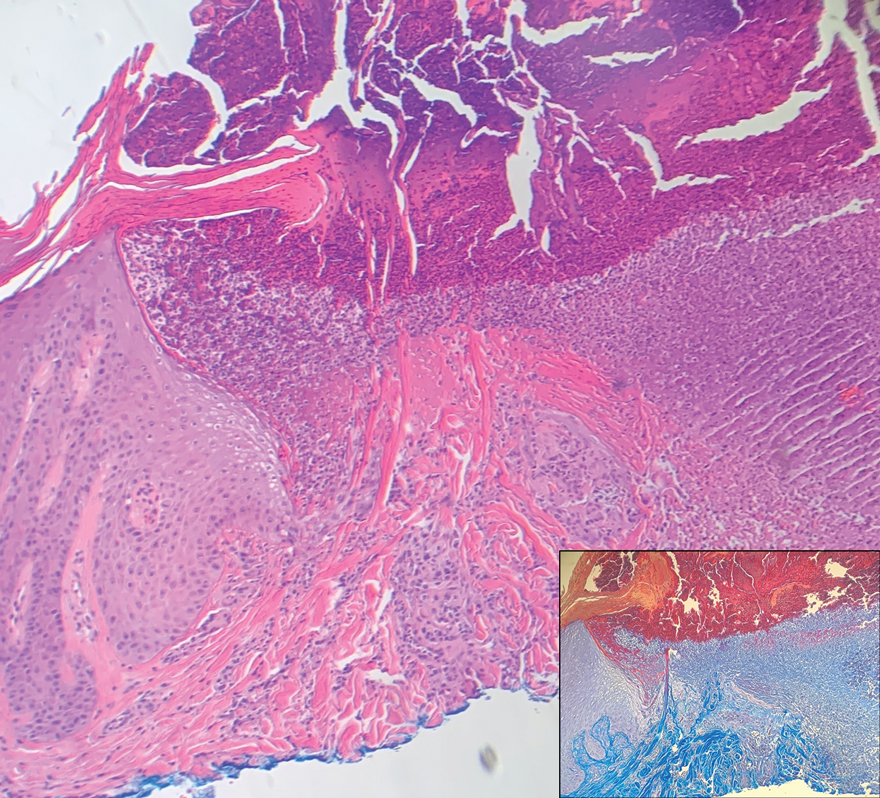

In our patient, histopathology revealed SK-like architecture with hyperorthokeratosis, papillomatosis, pseudohorn cyst formation, and basaloid acanthosis (Figure). However, within the lesion was an asymmetric proliferation of nested atypical melanocytes with melanin pigment production. The atypical melanocytes filled and expanded papillomatous projections without notable pagetoid growth and extended into the dermis. There was a background congenital nevus component. These findings were diagnostic of invasive malignant melanoma, extending to a Breslow depth of 5.5 mm. A follow-up sentinel lymph node biopsy was negative for metastatic melanoma. The clinical and histologic findings did not show melanoma in the surrounding skin to suggest colonization of an SK by an adjacent melanoma. The clinical history of a long-standing lesion in conjunction with a congenital nevus component on histology favored a diagnosis of melanoma arising in association with a congenital nevus with an SK-like architecture rather than arising in a preexisting SK or de novo melanoma.

Because our patient did not have multiple widespread SKs and reported rapid growth in the lesion in the last 6 months, there was concern for a malignant neoplasm. However, in patients with numerous SKs or areas of chronically sun-damaged skin, it can be difficult to identify suspicious lesions. It is important for clinicians to remain aware of SK-like melanomas and have a lower threshold for biopsy of any changing or symptomatic lesion that clinically resembles an SK. In our case, the history of change and the markedly different clinical appearance of the lesion in comparison to our patient's SKs prompted the biopsy. Criteria have been proposed to help differentiate these entities under dermoscopy, with melanoma showing the presence of the blue-black sign, pigment network, pseudopods or streaks, and/or the blue-white veil.4

Cutaneous metastases classically present as dermal nodules, plaques, or ulcers.5,6 A rare pigmented case of metastatic breast adenocarcinoma clinically mimicking melanoma has been reported.7 There is limited literature on the dermoscopic features of cutaneous metastases, but it appears that polymorphic vascular patterns are most common.5,8 The possibility of a metastatic melanoma involving an SK is a theoretical consideration, but there was no prior history of melanoma in our patient, and the histologic findings were consistent with primary melanoma. There was no histologic evidence of pigmented metastatic breast carcinoma or metastatic lung carcinoma.

Pigmented malignant hidroacanthoma simplex and pigmented porocarcinomas are rare malignant sweat gland tumors.9-11 Their benign counterparts are the more commonly encountered hidroacanthoma simplex (intraepidermal poroma) and poroma. Pigmented malignant hidroacanthoma simplex has been reported to clinically mimic an irritated SK.10 The histopathology of our case did not have features of malignant hidroacanthoma simplex or porocarcinoma. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma is an uncommon variant of squamous cell carcinoma, and histopathology would reveal proliferation of atypical keratinocytes.12

- Saggini A, Cota C, Lora V, et al. Uncommon histopathological variants of malignant melanoma. part 2. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:321-342.

- Klebanov N, Gunasekera N, Lin WM, et al. The clinical spectrum of cutaneous melanoma morphology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:178-188.

- Tran PT, Truong AK, Munday W, et al. Verrucous melanoma masquerading as a seborrheic keratosis. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt1m07k7fm.

- Carrera C, Segura S, Aguilera P. Dermoscopic clues for diagnosing melanomas that resemble seborrheic keratosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:544-551.

- Strickley JD, Jenson AB, Jung JY. Cutaneous metastasis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:173-197.

- Chernoff KA, Marghoob AA, Lacouture ME. Dermoscopic findings in cutaneous metastases. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:429-433.

- Marti N, Molina I, Monteagudo C, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of breast carcinoma mimicking malignant melanoma in scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:12.

- Kelati A, Gallouj S. Dermoscopy of skin metastases from breast cancer: two case reports. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12:273.

- Ishida M, Hotta M, Kushima R, et al. A case of porocarcinoma arising in pigmented hidroacanthoma simplex with multiple lymph node, liver and bone metastases. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:227-231.

- Lee JY, Lin MH. Pigmented malignant hidroacanthoma simplex mimicking irritated seborrheic keratosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:705-708.

- Ueo T, Kashima K, Daa T, et al. Porocarcinoma arising in pigmented hidroacanthoma simplex. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:500-503.

- Motta de Morais P, Schettini A, Rocha J, et al. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma: case report and importance of differential diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:96-98.

The Diagnosis: Seborrheic Keratosis-like Melanoma

Seborrheic keratosis (SK) is a benign neoplasm commonly encountered on the skin and frequently diagnosed by clinical examination alone. Seborrheic keratosis-like melanomas are melanomas that clinically or dermatoscopically resemble SKs and thus can be challenging to accurately diagnose. Melanomas can have a hyperkeratotic or verrucous appearance1-3 and can even exhibit dermatoscopic and microscopic features that are found in SKs such as comedolike openings and milialike cysts as well as acanthosis and pseudohorn cysts, respectively.2

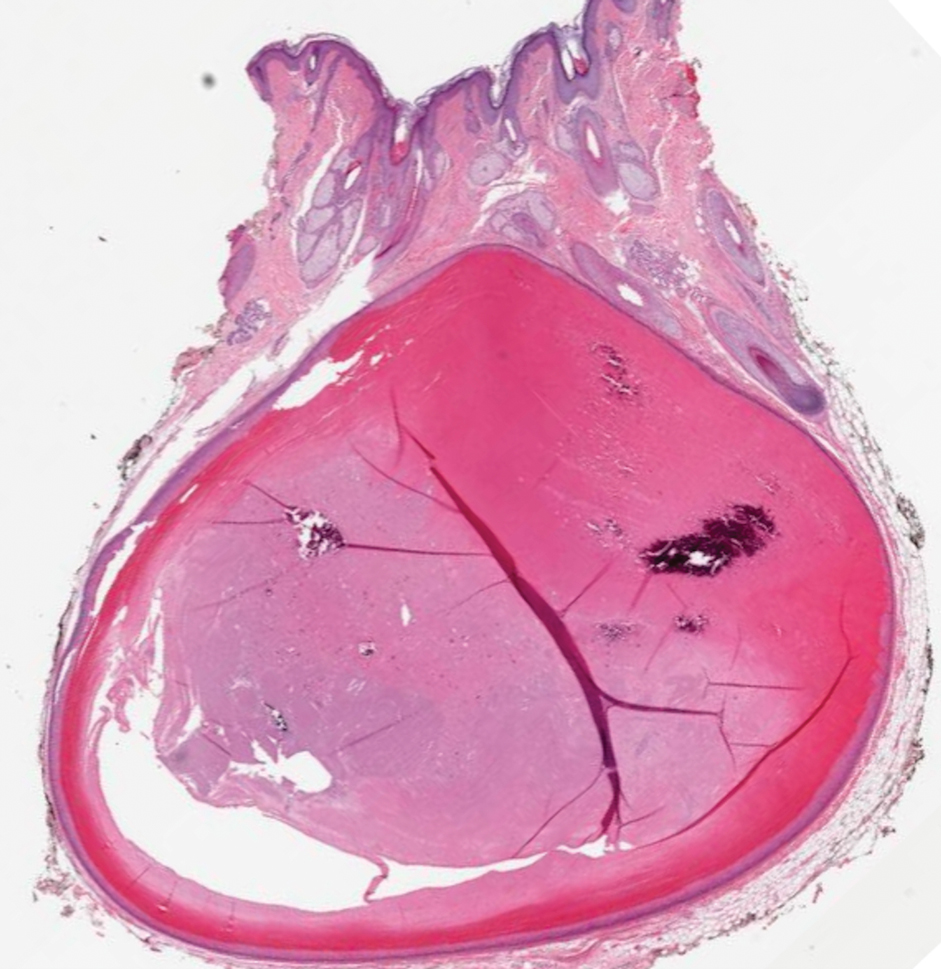

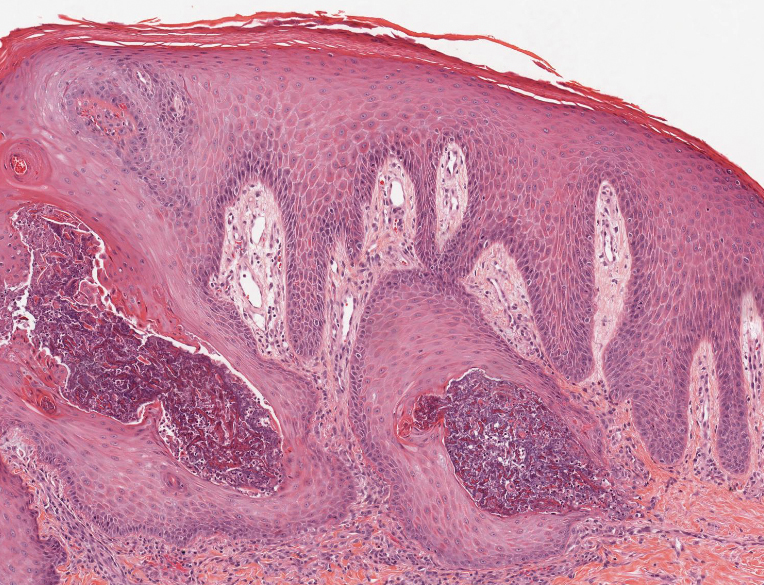

In our patient, histopathology revealed SK-like architecture with hyperorthokeratosis, papillomatosis, pseudohorn cyst formation, and basaloid acanthosis (Figure). However, within the lesion was an asymmetric proliferation of nested atypical melanocytes with melanin pigment production. The atypical melanocytes filled and expanded papillomatous projections without notable pagetoid growth and extended into the dermis. There was a background congenital nevus component. These findings were diagnostic of invasive malignant melanoma, extending to a Breslow depth of 5.5 mm. A follow-up sentinel lymph node biopsy was negative for metastatic melanoma. The clinical and histologic findings did not show melanoma in the surrounding skin to suggest colonization of an SK by an adjacent melanoma. The clinical history of a long-standing lesion in conjunction with a congenital nevus component on histology favored a diagnosis of melanoma arising in association with a congenital nevus with an SK-like architecture rather than arising in a preexisting SK or de novo melanoma.

Because our patient did not have multiple widespread SKs and reported rapid growth in the lesion in the last 6 months, there was concern for a malignant neoplasm. However, in patients with numerous SKs or areas of chronically sun-damaged skin, it can be difficult to identify suspicious lesions. It is important for clinicians to remain aware of SK-like melanomas and have a lower threshold for biopsy of any changing or symptomatic lesion that clinically resembles an SK. In our case, the history of change and the markedly different clinical appearance of the lesion in comparison to our patient's SKs prompted the biopsy. Criteria have been proposed to help differentiate these entities under dermoscopy, with melanoma showing the presence of the blue-black sign, pigment network, pseudopods or streaks, and/or the blue-white veil.4

Cutaneous metastases classically present as dermal nodules, plaques, or ulcers.5,6 A rare pigmented case of metastatic breast adenocarcinoma clinically mimicking melanoma has been reported.7 There is limited literature on the dermoscopic features of cutaneous metastases, but it appears that polymorphic vascular patterns are most common.5,8 The possibility of a metastatic melanoma involving an SK is a theoretical consideration, but there was no prior history of melanoma in our patient, and the histologic findings were consistent with primary melanoma. There was no histologic evidence of pigmented metastatic breast carcinoma or metastatic lung carcinoma.

Pigmented malignant hidroacanthoma simplex and pigmented porocarcinomas are rare malignant sweat gland tumors.9-11 Their benign counterparts are the more commonly encountered hidroacanthoma simplex (intraepidermal poroma) and poroma. Pigmented malignant hidroacanthoma simplex has been reported to clinically mimic an irritated SK.10 The histopathology of our case did not have features of malignant hidroacanthoma simplex or porocarcinoma. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma is an uncommon variant of squamous cell carcinoma, and histopathology would reveal proliferation of atypical keratinocytes.12

The Diagnosis: Seborrheic Keratosis-like Melanoma

Seborrheic keratosis (SK) is a benign neoplasm commonly encountered on the skin and frequently diagnosed by clinical examination alone. Seborrheic keratosis-like melanomas are melanomas that clinically or dermatoscopically resemble SKs and thus can be challenging to accurately diagnose. Melanomas can have a hyperkeratotic or verrucous appearance1-3 and can even exhibit dermatoscopic and microscopic features that are found in SKs such as comedolike openings and milialike cysts as well as acanthosis and pseudohorn cysts, respectively.2

In our patient, histopathology revealed SK-like architecture with hyperorthokeratosis, papillomatosis, pseudohorn cyst formation, and basaloid acanthosis (Figure). However, within the lesion was an asymmetric proliferation of nested atypical melanocytes with melanin pigment production. The atypical melanocytes filled and expanded papillomatous projections without notable pagetoid growth and extended into the dermis. There was a background congenital nevus component. These findings were diagnostic of invasive malignant melanoma, extending to a Breslow depth of 5.5 mm. A follow-up sentinel lymph node biopsy was negative for metastatic melanoma. The clinical and histologic findings did not show melanoma in the surrounding skin to suggest colonization of an SK by an adjacent melanoma. The clinical history of a long-standing lesion in conjunction with a congenital nevus component on histology favored a diagnosis of melanoma arising in association with a congenital nevus with an SK-like architecture rather than arising in a preexisting SK or de novo melanoma.

Because our patient did not have multiple widespread SKs and reported rapid growth in the lesion in the last 6 months, there was concern for a malignant neoplasm. However, in patients with numerous SKs or areas of chronically sun-damaged skin, it can be difficult to identify suspicious lesions. It is important for clinicians to remain aware of SK-like melanomas and have a lower threshold for biopsy of any changing or symptomatic lesion that clinically resembles an SK. In our case, the history of change and the markedly different clinical appearance of the lesion in comparison to our patient's SKs prompted the biopsy. Criteria have been proposed to help differentiate these entities under dermoscopy, with melanoma showing the presence of the blue-black sign, pigment network, pseudopods or streaks, and/or the blue-white veil.4

Cutaneous metastases classically present as dermal nodules, plaques, or ulcers.5,6 A rare pigmented case of metastatic breast adenocarcinoma clinically mimicking melanoma has been reported.7 There is limited literature on the dermoscopic features of cutaneous metastases, but it appears that polymorphic vascular patterns are most common.5,8 The possibility of a metastatic melanoma involving an SK is a theoretical consideration, but there was no prior history of melanoma in our patient, and the histologic findings were consistent with primary melanoma. There was no histologic evidence of pigmented metastatic breast carcinoma or metastatic lung carcinoma.

Pigmented malignant hidroacanthoma simplex and pigmented porocarcinomas are rare malignant sweat gland tumors.9-11 Their benign counterparts are the more commonly encountered hidroacanthoma simplex (intraepidermal poroma) and poroma. Pigmented malignant hidroacanthoma simplex has been reported to clinically mimic an irritated SK.10 The histopathology of our case did not have features of malignant hidroacanthoma simplex or porocarcinoma. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma is an uncommon variant of squamous cell carcinoma, and histopathology would reveal proliferation of atypical keratinocytes.12

- Saggini A, Cota C, Lora V, et al. Uncommon histopathological variants of malignant melanoma. part 2. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:321-342.

- Klebanov N, Gunasekera N, Lin WM, et al. The clinical spectrum of cutaneous melanoma morphology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:178-188.

- Tran PT, Truong AK, Munday W, et al. Verrucous melanoma masquerading as a seborrheic keratosis. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt1m07k7fm.

- Carrera C, Segura S, Aguilera P. Dermoscopic clues for diagnosing melanomas that resemble seborrheic keratosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:544-551.

- Strickley JD, Jenson AB, Jung JY. Cutaneous metastasis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:173-197.

- Chernoff KA, Marghoob AA, Lacouture ME. Dermoscopic findings in cutaneous metastases. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:429-433.

- Marti N, Molina I, Monteagudo C, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of breast carcinoma mimicking malignant melanoma in scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:12.

- Kelati A, Gallouj S. Dermoscopy of skin metastases from breast cancer: two case reports. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12:273.

- Ishida M, Hotta M, Kushima R, et al. A case of porocarcinoma arising in pigmented hidroacanthoma simplex with multiple lymph node, liver and bone metastases. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:227-231.

- Lee JY, Lin MH. Pigmented malignant hidroacanthoma simplex mimicking irritated seborrheic keratosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:705-708.

- Ueo T, Kashima K, Daa T, et al. Porocarcinoma arising in pigmented hidroacanthoma simplex. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:500-503.

- Motta de Morais P, Schettini A, Rocha J, et al. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma: case report and importance of differential diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:96-98.

- Saggini A, Cota C, Lora V, et al. Uncommon histopathological variants of malignant melanoma. part 2. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:321-342.

- Klebanov N, Gunasekera N, Lin WM, et al. The clinical spectrum of cutaneous melanoma morphology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:178-188.

- Tran PT, Truong AK, Munday W, et al. Verrucous melanoma masquerading as a seborrheic keratosis. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt1m07k7fm.

- Carrera C, Segura S, Aguilera P. Dermoscopic clues for diagnosing melanomas that resemble seborrheic keratosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:544-551.

- Strickley JD, Jenson AB, Jung JY. Cutaneous metastasis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:173-197.

- Chernoff KA, Marghoob AA, Lacouture ME. Dermoscopic findings in cutaneous metastases. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:429-433.

- Marti N, Molina I, Monteagudo C, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of breast carcinoma mimicking malignant melanoma in scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:12.

- Kelati A, Gallouj S. Dermoscopy of skin metastases from breast cancer: two case reports. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12:273.

- Ishida M, Hotta M, Kushima R, et al. A case of porocarcinoma arising in pigmented hidroacanthoma simplex with multiple lymph node, liver and bone metastases. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:227-231.

- Lee JY, Lin MH. Pigmented malignant hidroacanthoma simplex mimicking irritated seborrheic keratosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:705-708.

- Ueo T, Kashima K, Daa T, et al. Porocarcinoma arising in pigmented hidroacanthoma simplex. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:500-503.

- Motta de Morais P, Schettini A, Rocha J, et al. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma: case report and importance of differential diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:96-98.

A 71-year-old woman presented with a persistent asymptomatic lesion on the right upper back that had recently increased in size and changed in color, shape, and texture. The lesion had been present for many years. Physical examination revealed a 1.5-cm, dark brown, hyperkeratotic nodule with no identifiable pigment network on dermatoscopy. The patient had no personal history of melanoma but did have a history of stage I non–small cell lung cancer. A review of systems was noncontributory. A shave biopsy of the lesion was performed.

Inframammary Macerated Erosion

The Diagnosis: Hailey-Hailey Disease (Benign Familial Chronic Pemphigus)