Article

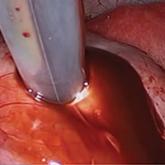

Hysterectomy in patients with history of prior cesarean delivery: A reverse dissection technique for vesicouterine adhesions

- Author:

- Camran Nezhat, MD

- Mailinh Vu, MD

- Nataliya Vang, MD

- Edzhem Tombash, MS3

- Azadeh Nezhat, MD

Vesicouterine adhesions resulting from prior CDs or other surgeries can distort the pelvic anatomy and present challenges during...

Article

A patient with severe adenomyosis requests uterine-sparing surgery

- Author:

- Camran Nezhat, MD

- Michelle A. Wood, DO

- Megan Kennedy Burns, MD, MA

- Azadeh Nezhat, MD

Combined laparoscopy and, when necessary, minilaparotomy is the authors’ preferred technique. It can relieve many symptoms of...

Video

Laparoscopic excision of type I and type II endometriomas

- Author:

- Frances Farrimond, BA

- Rebecca Falik, MD

- Anjie Li, MD

- Azadeh Nezhat, MD

- Camran Nezhat, MD

News

Cesarean scar defect: What is it and how should it be treated?

- Author:

- Camran Nezhat, MD

- Lindsey Grace, MD

- Rose Soliemannjad, BS

- Gity Meshkat Razavi, MD

- Azadeh Nezhat, MD

Hysteroscopic resection and laparoscopic repair can reduce a woman’s symptoms arising from cesarean scar defect. The technique of choice depends...