User login

Generalized pustular eruption

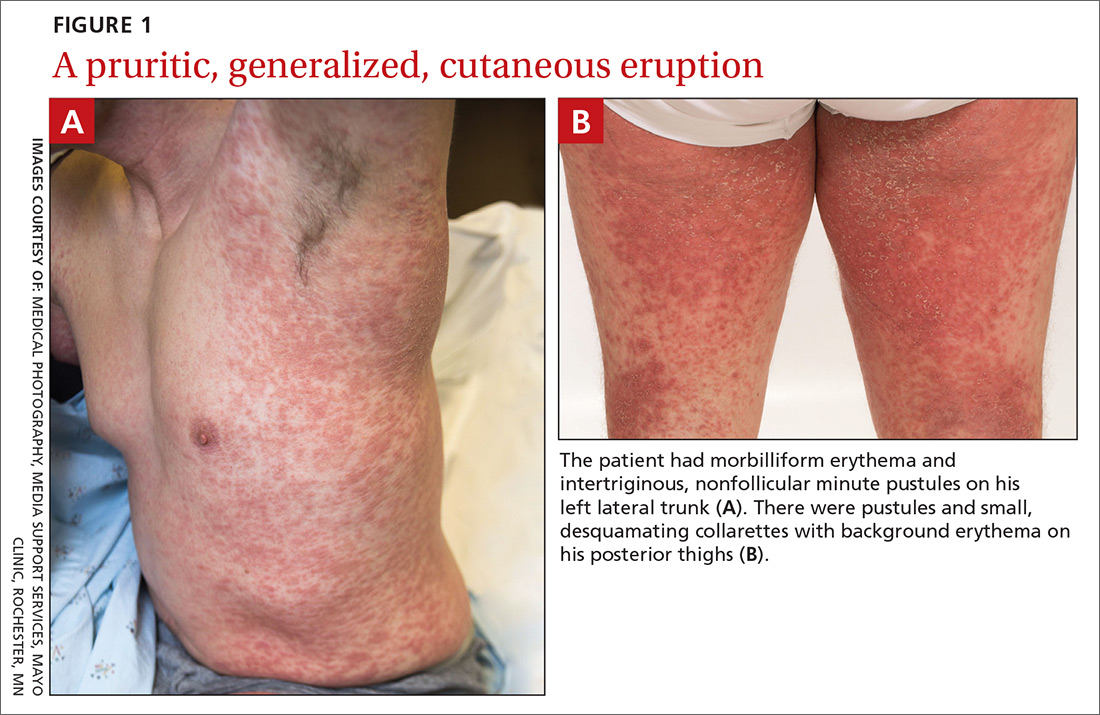

A 38-year-old man sought care in the emergency department for an acute, pruritic, generalized cutaneous eruption that manifested in the intertriginous areas of the inner thighs, antecubital fossae, and axilla (FIGURE 1A). He reported associated chills, a 15-pound weight gain, and swelling of his inner thighs. Two weeks before presentation, he had received azithromycin for an upper respiratory tract infection. He was unsure if the rash developed prior to or after taking the medication. He was not taking any other medications and had no history of skin conditions.

On examination, the patient was afebrile and had bilateral thigh edema. Skin examination revealed background erythema with morbilliform papules, plaques, and patches on the bilateral flanks, back, buttocks, arms, legs, and central neck. Pinpoint pustules were present in the intertriginous sites and on the low back and buttocks. The laboratory evaluation revealed leukocytosis (11.0 × 109 cells/L), increased levels of neutrophils and eosinophils, and an elevated C-reactive protein level (12.8 mg/L). The remaining laboratory results were unremarkable. The patient was referred to Dermatology.

An examination by the dermatologist 3 days later revealed small areas of annular desquamation with a few pinpoint pustules, mostly located on the inner thighs and buttocks (FIGURE 1B). Skin biopsies were taken from the anterior hip region. The histopathology revealed subacute dermatitis with mixed dermal inflammatory cells, including neutrophils and eosinophils, and discrete subcorneal spongiform pustules.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)

The acute rash with minute pustules and associated leukocytosis with neutrophilia and eosinophilia led to an early diagnosis of AGEP, which may have been triggered by azithromycin—the patient’s only recent medication. AGEP is a severe cutaneous eruption that may be associated with systemic involvement. Medications are usually implicated, and patients often seek urgent evaluation.

AGEP typically begins as an acute eruption in the intertriginous sites of the axilla, groin, and neck, but often becomes more generalized.1,2 The diagnosis is strongly suggested by the condition’s key features: fever (97% of cases) and leukocytosis (87%) with neutrophilia (91%) and eosinophilia (30%); leukocytosis peaks 4 days after pustulosis occurs and lasts for about 12 days.1 Although common, fever is not always documented in patients with AGEP. 3 (Our patient was a case in point.) While not a key characteristic of AGEP, our patient’s weight gain was likely explained by the severe edema secondary to his inflammatory skin eruption.

Medications are implicated, but pathophysiology is unknown

In approximately 90% of AGEP cases, medications such as antibiotics and calcium channel blockers are implicated; however, the lack of such an association does not preclude the diagnosis.1,4 In cases of drug reactions, the eruption typically develops 1 to 2 days after a medication is begun, and the pustules typically resolve in fewer than 15 days.5 In 17% of patients, systemic involvement can occur and can include the liver, kidneys, bone marrow, and lungs.6 A physical exam, review of systems, and a laboratory evaluation can help rule out systemic involvement and guide additional testing.

AGEP has an incidence of 1 to 5 cases per million people per year, affecting women slightly more frequently than men.7 While the pathophysiology is not well understood, AGEP and its differential diagnoses are categorized as T cell-related inflammatory responses.4,7

Distinguishing AGEP from some look-alikes

There are at least 4 severe cutaneous eruptions that might be confused with AGEP, all of which may be associated with fever. They include: drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome; Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS); toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN); and pustular psoriasis.8-10 The clinical features that may help differentiate these conditions from AGEP include timeline, mucocutaneous features, organ system involvement, and histopathologic findings.4,8

DRESS occurs 2 to 6 weeks after drug exposure, rather than a few days, as is seen with AGEP. It often involves morbilliform erythema and facial edema with substantial eosinophilia and possible nephritis, pneumonitis, myocarditis, and thyroiditis.9 Unlike AGEP, DRESS does not have a predilection for intertriginous anatomic locations.

SJS and TEN occur 1 to 3 weeks after drug exposure. These conditions manifest with the development of bullae, atypical targetoid lesions, painful dusky erythema, epidermal necrosis, and mucosal involvement at multiple sites. Tubular nephritis, tracheobronchial necrosis, and multisystem organ failure can occur, with reported mortality rates of 5% to 35%.8,11

Pustular psoriasis is frequently confused with AGEP. However, AGEP usually develops fewer than 2 days after drug exposure, with pustules that begin in intertriginous sites, and there is associated neutrophilia and possible organ involvement.1,8 Patients who have AGEP typically do not have a history of psoriasis, while patients with pustular psoriasis often do.7 A history of drug reaction is uncommon with pustular psoriasis (although rapid tapering of systemic corticosteroids in patients with psoriasis can trigger the development of pustular psoriasis), whereas a previous history of drug reaction is common in AGEP.3,7

Discontinue medication, treat with corticosteroids

Patients who have AGEP, including those with systemic involvement, generally improve after the offending drug is discontinued and treatment with topical corticosteroids is initiated.6 A brief course of systemic corticosteroids can also be considered for patients with severe skin involvement or systemic involvement.3

Our patient was prescribed topical corticosteroid wet dressing treatments twice daily for 2 weeks. At the 2-week follow-up visit, the rash had completely cleared, and only minimal residual erythema was noted (FIGURE 2). The patient was instructed to avoid azithromycin.

CORRESPONDENCE

David A. Wetter, MD, Department of Dermatology, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905; wetter.david@mayo.edu.

1. Roujeau JC, Bioulac-Sage P, Bourseau C, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Analysis of 63 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1333-1338.

2. Lee HY, Chou D, Pang SM, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: analysis of cases managed in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:507-512.

3. Alniemi DT, Wetter DA, Bridges AG, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: clinical characteristics, etiologic associations, treatments, and outcomes in a series of 28 patients at Mayo Clinic, 1996-2013. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:405-414.

4. Bouvresse S, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Ortonne N, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis, DRESS, AGEP: do overlap cases exist? Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:72.

5. Sidoroff A, Halevy S, Bavinck JN, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—a clinical reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:113-119.

6. Hotz C, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Haddad C, et al. Systemic involvement of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a retrospective study on 58 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1223-1232.

7. Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:E1214.

8. Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: Part II. Management and therapeutics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:709.e1-e9.

9. Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: Part I. Clinical perspectives. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:693.e1-e14.

10. Bastuji-Garin S, Rzany B, Stern RS, et al. Clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:92-96.

11. Roujeau JC. The spectrum of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a clinical classification. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:28S-30S.

A 38-year-old man sought care in the emergency department for an acute, pruritic, generalized cutaneous eruption that manifested in the intertriginous areas of the inner thighs, antecubital fossae, and axilla (FIGURE 1A). He reported associated chills, a 15-pound weight gain, and swelling of his inner thighs. Two weeks before presentation, he had received azithromycin for an upper respiratory tract infection. He was unsure if the rash developed prior to or after taking the medication. He was not taking any other medications and had no history of skin conditions.

On examination, the patient was afebrile and had bilateral thigh edema. Skin examination revealed background erythema with morbilliform papules, plaques, and patches on the bilateral flanks, back, buttocks, arms, legs, and central neck. Pinpoint pustules were present in the intertriginous sites and on the low back and buttocks. The laboratory evaluation revealed leukocytosis (11.0 × 109 cells/L), increased levels of neutrophils and eosinophils, and an elevated C-reactive protein level (12.8 mg/L). The remaining laboratory results were unremarkable. The patient was referred to Dermatology.

An examination by the dermatologist 3 days later revealed small areas of annular desquamation with a few pinpoint pustules, mostly located on the inner thighs and buttocks (FIGURE 1B). Skin biopsies were taken from the anterior hip region. The histopathology revealed subacute dermatitis with mixed dermal inflammatory cells, including neutrophils and eosinophils, and discrete subcorneal spongiform pustules.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)

The acute rash with minute pustules and associated leukocytosis with neutrophilia and eosinophilia led to an early diagnosis of AGEP, which may have been triggered by azithromycin—the patient’s only recent medication. AGEP is a severe cutaneous eruption that may be associated with systemic involvement. Medications are usually implicated, and patients often seek urgent evaluation.

AGEP typically begins as an acute eruption in the intertriginous sites of the axilla, groin, and neck, but often becomes more generalized.1,2 The diagnosis is strongly suggested by the condition’s key features: fever (97% of cases) and leukocytosis (87%) with neutrophilia (91%) and eosinophilia (30%); leukocytosis peaks 4 days after pustulosis occurs and lasts for about 12 days.1 Although common, fever is not always documented in patients with AGEP. 3 (Our patient was a case in point.) While not a key characteristic of AGEP, our patient’s weight gain was likely explained by the severe edema secondary to his inflammatory skin eruption.

Medications are implicated, but pathophysiology is unknown

In approximately 90% of AGEP cases, medications such as antibiotics and calcium channel blockers are implicated; however, the lack of such an association does not preclude the diagnosis.1,4 In cases of drug reactions, the eruption typically develops 1 to 2 days after a medication is begun, and the pustules typically resolve in fewer than 15 days.5 In 17% of patients, systemic involvement can occur and can include the liver, kidneys, bone marrow, and lungs.6 A physical exam, review of systems, and a laboratory evaluation can help rule out systemic involvement and guide additional testing.

AGEP has an incidence of 1 to 5 cases per million people per year, affecting women slightly more frequently than men.7 While the pathophysiology is not well understood, AGEP and its differential diagnoses are categorized as T cell-related inflammatory responses.4,7

Distinguishing AGEP from some look-alikes

There are at least 4 severe cutaneous eruptions that might be confused with AGEP, all of which may be associated with fever. They include: drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome; Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS); toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN); and pustular psoriasis.8-10 The clinical features that may help differentiate these conditions from AGEP include timeline, mucocutaneous features, organ system involvement, and histopathologic findings.4,8

DRESS occurs 2 to 6 weeks after drug exposure, rather than a few days, as is seen with AGEP. It often involves morbilliform erythema and facial edema with substantial eosinophilia and possible nephritis, pneumonitis, myocarditis, and thyroiditis.9 Unlike AGEP, DRESS does not have a predilection for intertriginous anatomic locations.

SJS and TEN occur 1 to 3 weeks after drug exposure. These conditions manifest with the development of bullae, atypical targetoid lesions, painful dusky erythema, epidermal necrosis, and mucosal involvement at multiple sites. Tubular nephritis, tracheobronchial necrosis, and multisystem organ failure can occur, with reported mortality rates of 5% to 35%.8,11

Pustular psoriasis is frequently confused with AGEP. However, AGEP usually develops fewer than 2 days after drug exposure, with pustules that begin in intertriginous sites, and there is associated neutrophilia and possible organ involvement.1,8 Patients who have AGEP typically do not have a history of psoriasis, while patients with pustular psoriasis often do.7 A history of drug reaction is uncommon with pustular psoriasis (although rapid tapering of systemic corticosteroids in patients with psoriasis can trigger the development of pustular psoriasis), whereas a previous history of drug reaction is common in AGEP.3,7

Discontinue medication, treat with corticosteroids

Patients who have AGEP, including those with systemic involvement, generally improve after the offending drug is discontinued and treatment with topical corticosteroids is initiated.6 A brief course of systemic corticosteroids can also be considered for patients with severe skin involvement or systemic involvement.3

Our patient was prescribed topical corticosteroid wet dressing treatments twice daily for 2 weeks. At the 2-week follow-up visit, the rash had completely cleared, and only minimal residual erythema was noted (FIGURE 2). The patient was instructed to avoid azithromycin.

CORRESPONDENCE

David A. Wetter, MD, Department of Dermatology, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905; wetter.david@mayo.edu.

A 38-year-old man sought care in the emergency department for an acute, pruritic, generalized cutaneous eruption that manifested in the intertriginous areas of the inner thighs, antecubital fossae, and axilla (FIGURE 1A). He reported associated chills, a 15-pound weight gain, and swelling of his inner thighs. Two weeks before presentation, he had received azithromycin for an upper respiratory tract infection. He was unsure if the rash developed prior to or after taking the medication. He was not taking any other medications and had no history of skin conditions.

On examination, the patient was afebrile and had bilateral thigh edema. Skin examination revealed background erythema with morbilliform papules, plaques, and patches on the bilateral flanks, back, buttocks, arms, legs, and central neck. Pinpoint pustules were present in the intertriginous sites and on the low back and buttocks. The laboratory evaluation revealed leukocytosis (11.0 × 109 cells/L), increased levels of neutrophils and eosinophils, and an elevated C-reactive protein level (12.8 mg/L). The remaining laboratory results were unremarkable. The patient was referred to Dermatology.

An examination by the dermatologist 3 days later revealed small areas of annular desquamation with a few pinpoint pustules, mostly located on the inner thighs and buttocks (FIGURE 1B). Skin biopsies were taken from the anterior hip region. The histopathology revealed subacute dermatitis with mixed dermal inflammatory cells, including neutrophils and eosinophils, and discrete subcorneal spongiform pustules.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)

The acute rash with minute pustules and associated leukocytosis with neutrophilia and eosinophilia led to an early diagnosis of AGEP, which may have been triggered by azithromycin—the patient’s only recent medication. AGEP is a severe cutaneous eruption that may be associated with systemic involvement. Medications are usually implicated, and patients often seek urgent evaluation.

AGEP typically begins as an acute eruption in the intertriginous sites of the axilla, groin, and neck, but often becomes more generalized.1,2 The diagnosis is strongly suggested by the condition’s key features: fever (97% of cases) and leukocytosis (87%) with neutrophilia (91%) and eosinophilia (30%); leukocytosis peaks 4 days after pustulosis occurs and lasts for about 12 days.1 Although common, fever is not always documented in patients with AGEP. 3 (Our patient was a case in point.) While not a key characteristic of AGEP, our patient’s weight gain was likely explained by the severe edema secondary to his inflammatory skin eruption.

Medications are implicated, but pathophysiology is unknown

In approximately 90% of AGEP cases, medications such as antibiotics and calcium channel blockers are implicated; however, the lack of such an association does not preclude the diagnosis.1,4 In cases of drug reactions, the eruption typically develops 1 to 2 days after a medication is begun, and the pustules typically resolve in fewer than 15 days.5 In 17% of patients, systemic involvement can occur and can include the liver, kidneys, bone marrow, and lungs.6 A physical exam, review of systems, and a laboratory evaluation can help rule out systemic involvement and guide additional testing.

AGEP has an incidence of 1 to 5 cases per million people per year, affecting women slightly more frequently than men.7 While the pathophysiology is not well understood, AGEP and its differential diagnoses are categorized as T cell-related inflammatory responses.4,7

Distinguishing AGEP from some look-alikes

There are at least 4 severe cutaneous eruptions that might be confused with AGEP, all of which may be associated with fever. They include: drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome; Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS); toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN); and pustular psoriasis.8-10 The clinical features that may help differentiate these conditions from AGEP include timeline, mucocutaneous features, organ system involvement, and histopathologic findings.4,8

DRESS occurs 2 to 6 weeks after drug exposure, rather than a few days, as is seen with AGEP. It often involves morbilliform erythema and facial edema with substantial eosinophilia and possible nephritis, pneumonitis, myocarditis, and thyroiditis.9 Unlike AGEP, DRESS does not have a predilection for intertriginous anatomic locations.

SJS and TEN occur 1 to 3 weeks after drug exposure. These conditions manifest with the development of bullae, atypical targetoid lesions, painful dusky erythema, epidermal necrosis, and mucosal involvement at multiple sites. Tubular nephritis, tracheobronchial necrosis, and multisystem organ failure can occur, with reported mortality rates of 5% to 35%.8,11

Pustular psoriasis is frequently confused with AGEP. However, AGEP usually develops fewer than 2 days after drug exposure, with pustules that begin in intertriginous sites, and there is associated neutrophilia and possible organ involvement.1,8 Patients who have AGEP typically do not have a history of psoriasis, while patients with pustular psoriasis often do.7 A history of drug reaction is uncommon with pustular psoriasis (although rapid tapering of systemic corticosteroids in patients with psoriasis can trigger the development of pustular psoriasis), whereas a previous history of drug reaction is common in AGEP.3,7

Discontinue medication, treat with corticosteroids

Patients who have AGEP, including those with systemic involvement, generally improve after the offending drug is discontinued and treatment with topical corticosteroids is initiated.6 A brief course of systemic corticosteroids can also be considered for patients with severe skin involvement or systemic involvement.3

Our patient was prescribed topical corticosteroid wet dressing treatments twice daily for 2 weeks. At the 2-week follow-up visit, the rash had completely cleared, and only minimal residual erythema was noted (FIGURE 2). The patient was instructed to avoid azithromycin.

CORRESPONDENCE

David A. Wetter, MD, Department of Dermatology, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905; wetter.david@mayo.edu.

1. Roujeau JC, Bioulac-Sage P, Bourseau C, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Analysis of 63 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1333-1338.

2. Lee HY, Chou D, Pang SM, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: analysis of cases managed in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:507-512.

3. Alniemi DT, Wetter DA, Bridges AG, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: clinical characteristics, etiologic associations, treatments, and outcomes in a series of 28 patients at Mayo Clinic, 1996-2013. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:405-414.

4. Bouvresse S, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Ortonne N, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis, DRESS, AGEP: do overlap cases exist? Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:72.

5. Sidoroff A, Halevy S, Bavinck JN, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—a clinical reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:113-119.

6. Hotz C, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Haddad C, et al. Systemic involvement of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a retrospective study on 58 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1223-1232.

7. Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:E1214.

8. Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: Part II. Management and therapeutics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:709.e1-e9.

9. Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: Part I. Clinical perspectives. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:693.e1-e14.

10. Bastuji-Garin S, Rzany B, Stern RS, et al. Clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:92-96.

11. Roujeau JC. The spectrum of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a clinical classification. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:28S-30S.

1. Roujeau JC, Bioulac-Sage P, Bourseau C, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Analysis of 63 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1333-1338.

2. Lee HY, Chou D, Pang SM, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: analysis of cases managed in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:507-512.

3. Alniemi DT, Wetter DA, Bridges AG, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: clinical characteristics, etiologic associations, treatments, and outcomes in a series of 28 patients at Mayo Clinic, 1996-2013. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:405-414.

4. Bouvresse S, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Ortonne N, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis, DRESS, AGEP: do overlap cases exist? Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:72.

5. Sidoroff A, Halevy S, Bavinck JN, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—a clinical reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:113-119.

6. Hotz C, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Haddad C, et al. Systemic involvement of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a retrospective study on 58 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1223-1232.

7. Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:E1214.

8. Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: Part II. Management and therapeutics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:709.e1-e9.

9. Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: Part I. Clinical perspectives. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:693.e1-e14.

10. Bastuji-Garin S, Rzany B, Stern RS, et al. Clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:92-96.

11. Roujeau JC. The spectrum of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a clinical classification. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:28S-30S.