User login

Blue-black hyperpigmentation on the extremities

A 68-year-old man with type 2 diabetes presented with progressive hyperpigmentation of the lower extremities and face over the past 3 years. Clinical examination revealed confluent, blue-black hyperpigmentation of the lower extremities (Figure), upper extremities, neck, and face. Laboratory tests and arterial studies were within normal ranges. The patient’s medication list included lisinopril 10 mg/d, metformin 1000 mg twice daily, minocycline 100 mg twice daily, and omeprazole 20 mg/d.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation

Hyperpigmentation is a rare but not uncommon adverse effect of long-term minocycline use. In this case, our patient had been taking minocycline for more than 5 years. When seen in our clinic, he said he could not remember why he was taking minocycline and incorrectly assumed it was for his diabetes. Chart review of outside records revealed that it had been prescribed, and refilled annually, by his primary physician for rosacea.

Minocycline hyperpigmentation is subdivided into 3 types:

- Type I manifests with blue-black discoloration in previously inflamed areas of skin.

- Type II manifests with blue-gray pigmentation in previously normal skin areas.

- Type III manifests diffusely with muddy-brown hyperpigmentation on photoexposed skin.

Furthermore, noncutaneous manifestations may occur on the sclera, nails, ear cartilage, bone, oral mucosa, teeth, and thyroid gland.1

Diagnosis focuses on identifying the source

Minocycline is one of many drugs that can induce hyperpigmentation of the skin. In addition to history, examination, and review of the patient’s medication list, there are some clues on exam that may suggest a certain type of medication at play.

Continue to: Antimalarials

Antimalarials. Chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, and quinacrine can cause blue-black skin hyperpigmentation in as many as 25% of patients. Common locations include the shins, face, oral mucosa, and subungual skin. This hyperpigmentation rarely fully resolves.2

Amiodarone. Hyperpigmentation secondary to amiodarone use typically is slate-gray in color and involves photoexposed skin. Patients should be counseled that pigmentation may—but does not always—fade with time after discontinuation of the drug.2

Heavy metals. Argyria results from exposure to silver, either ingested orally or applied externally. A common cause of argyria is ingestion of excessive amounts of silver-containing supplements.3 Affected patients present with diffuse slate-gray discoloration of the skin.

Other metals implicated in skin hyperpigmentation include arsenic, gold, mercury, and iron. Review of all supplements and herbal remedies in patients presenting with skin hyperpigmentation is crucial.

Bleomycin is a chemotherapeutic agent with a rare but unique adverse effect of inducing flagellate hyperpigmentation that favors the chest, abdomen, or back. This may be induced by trauma or scratching and is often transient. Hyperpigmentation can occur secondary to either intravenous or intralesional injection of the medication.2

Continue to: In addition to medication...

In addition to medication- or supplement-induced hyperpigmentation, there is a physiologic source that should be considered when a patient presents with lower-extremity hyperpigmentation:

Stasis hyperpigmentation. Patients with chronic venous insufficiency may present with hyperpigmentation of the lower extremities. Commonly due to dysfunctional venous valves or obstruction, stasis hyperpigmentation manifests with red-brown discoloration from dermal hemosiderin deposition.4

Unlike our patient, those with stasis hyperpigmentation may present symptomatically, with associated dry skin, pruritus, induration, and inflammation. Treatment involves management of the underlying venous insufficiency.4

When there’s no obvious cause, be prepared to dig deeper

At the time of initial assessment, a thorough review of systems and detailed medication history, including over-the-counter supplements, should be obtained. Physical examination revealing diffuse, generalized hyperpigmentation with no reliable culprit medication in the patient’s history warrants further laboratory evaluation. This includes ordering renal and liver studies and tests for thyroid-stimulating hormone and ferritin and cortisol levels to rule out metabolic or endocrine hyperpigmentation disorders.

Stopping the offending medication is the first step

Discontinuation of the offending medication may result in mild improvement in skin hyperpigmentation over time. Some patients may not experience any improvement. If improvement occurs, it is important to educate patients that it can take several months to years. Dermatology guidelines favor discontinuation of antibiotics for acne or rosacea after 3 to 6 months to avoid bacterial resistance.5 Worsening hyperpigmentation despite medication discontinuation warrants further work-up.

Patients who are distressed by persistent hyperpigmentation can be treated using picosecond or Q-switched lasers.6

Our patient was advised to discontinue the minocycline. Three test spots on his face were treated with pulsed-dye laser, carbon dioxide laser, and dermabrasion. The patient noted that the spots responded better to the carbon dioxide laser and dermabrasion compared to the pulsed-dye laser. He did not follow up for further treatment.

1. Wetter DA. Minocycline hyperpigmentation. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:e33. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.02.013

2. Chang MW. Chapter 67: Disorders of hyperpigmentation. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, et al (eds). Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1122-1124.

3. Bowden LP, Royer MC, Hallman JR, et al. Rapid onset of argyria induced by a silver-containing dietary supplement. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:832-835. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2011.01755.x

4. Patterson J. Stasis dermatitis. In: Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier;2010: 121-153.

5. Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-73.e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037

6. Barrett T, de Zwaan S. Picosecond alexandrite laser is superior to Q-switched Nd:YAG laser in treatment of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation: a case study and review of the literature. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2018;20:387-390. doi: 10.1080/14764172.2017.1418514

A 68-year-old man with type 2 diabetes presented with progressive hyperpigmentation of the lower extremities and face over the past 3 years. Clinical examination revealed confluent, blue-black hyperpigmentation of the lower extremities (Figure), upper extremities, neck, and face. Laboratory tests and arterial studies were within normal ranges. The patient’s medication list included lisinopril 10 mg/d, metformin 1000 mg twice daily, minocycline 100 mg twice daily, and omeprazole 20 mg/d.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation

Hyperpigmentation is a rare but not uncommon adverse effect of long-term minocycline use. In this case, our patient had been taking minocycline for more than 5 years. When seen in our clinic, he said he could not remember why he was taking minocycline and incorrectly assumed it was for his diabetes. Chart review of outside records revealed that it had been prescribed, and refilled annually, by his primary physician for rosacea.

Minocycline hyperpigmentation is subdivided into 3 types:

- Type I manifests with blue-black discoloration in previously inflamed areas of skin.

- Type II manifests with blue-gray pigmentation in previously normal skin areas.

- Type III manifests diffusely with muddy-brown hyperpigmentation on photoexposed skin.

Furthermore, noncutaneous manifestations may occur on the sclera, nails, ear cartilage, bone, oral mucosa, teeth, and thyroid gland.1

Diagnosis focuses on identifying the source

Minocycline is one of many drugs that can induce hyperpigmentation of the skin. In addition to history, examination, and review of the patient’s medication list, there are some clues on exam that may suggest a certain type of medication at play.

Continue to: Antimalarials

Antimalarials. Chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, and quinacrine can cause blue-black skin hyperpigmentation in as many as 25% of patients. Common locations include the shins, face, oral mucosa, and subungual skin. This hyperpigmentation rarely fully resolves.2

Amiodarone. Hyperpigmentation secondary to amiodarone use typically is slate-gray in color and involves photoexposed skin. Patients should be counseled that pigmentation may—but does not always—fade with time after discontinuation of the drug.2

Heavy metals. Argyria results from exposure to silver, either ingested orally or applied externally. A common cause of argyria is ingestion of excessive amounts of silver-containing supplements.3 Affected patients present with diffuse slate-gray discoloration of the skin.

Other metals implicated in skin hyperpigmentation include arsenic, gold, mercury, and iron. Review of all supplements and herbal remedies in patients presenting with skin hyperpigmentation is crucial.

Bleomycin is a chemotherapeutic agent with a rare but unique adverse effect of inducing flagellate hyperpigmentation that favors the chest, abdomen, or back. This may be induced by trauma or scratching and is often transient. Hyperpigmentation can occur secondary to either intravenous or intralesional injection of the medication.2

Continue to: In addition to medication...

In addition to medication- or supplement-induced hyperpigmentation, there is a physiologic source that should be considered when a patient presents with lower-extremity hyperpigmentation:

Stasis hyperpigmentation. Patients with chronic venous insufficiency may present with hyperpigmentation of the lower extremities. Commonly due to dysfunctional venous valves or obstruction, stasis hyperpigmentation manifests with red-brown discoloration from dermal hemosiderin deposition.4

Unlike our patient, those with stasis hyperpigmentation may present symptomatically, with associated dry skin, pruritus, induration, and inflammation. Treatment involves management of the underlying venous insufficiency.4

When there’s no obvious cause, be prepared to dig deeper

At the time of initial assessment, a thorough review of systems and detailed medication history, including over-the-counter supplements, should be obtained. Physical examination revealing diffuse, generalized hyperpigmentation with no reliable culprit medication in the patient’s history warrants further laboratory evaluation. This includes ordering renal and liver studies and tests for thyroid-stimulating hormone and ferritin and cortisol levels to rule out metabolic or endocrine hyperpigmentation disorders.

Stopping the offending medication is the first step

Discontinuation of the offending medication may result in mild improvement in skin hyperpigmentation over time. Some patients may not experience any improvement. If improvement occurs, it is important to educate patients that it can take several months to years. Dermatology guidelines favor discontinuation of antibiotics for acne or rosacea after 3 to 6 months to avoid bacterial resistance.5 Worsening hyperpigmentation despite medication discontinuation warrants further work-up.

Patients who are distressed by persistent hyperpigmentation can be treated using picosecond or Q-switched lasers.6

Our patient was advised to discontinue the minocycline. Three test spots on his face were treated with pulsed-dye laser, carbon dioxide laser, and dermabrasion. The patient noted that the spots responded better to the carbon dioxide laser and dermabrasion compared to the pulsed-dye laser. He did not follow up for further treatment.

A 68-year-old man with type 2 diabetes presented with progressive hyperpigmentation of the lower extremities and face over the past 3 years. Clinical examination revealed confluent, blue-black hyperpigmentation of the lower extremities (Figure), upper extremities, neck, and face. Laboratory tests and arterial studies were within normal ranges. The patient’s medication list included lisinopril 10 mg/d, metformin 1000 mg twice daily, minocycline 100 mg twice daily, and omeprazole 20 mg/d.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation

Hyperpigmentation is a rare but not uncommon adverse effect of long-term minocycline use. In this case, our patient had been taking minocycline for more than 5 years. When seen in our clinic, he said he could not remember why he was taking minocycline and incorrectly assumed it was for his diabetes. Chart review of outside records revealed that it had been prescribed, and refilled annually, by his primary physician for rosacea.

Minocycline hyperpigmentation is subdivided into 3 types:

- Type I manifests with blue-black discoloration in previously inflamed areas of skin.

- Type II manifests with blue-gray pigmentation in previously normal skin areas.

- Type III manifests diffusely with muddy-brown hyperpigmentation on photoexposed skin.

Furthermore, noncutaneous manifestations may occur on the sclera, nails, ear cartilage, bone, oral mucosa, teeth, and thyroid gland.1

Diagnosis focuses on identifying the source

Minocycline is one of many drugs that can induce hyperpigmentation of the skin. In addition to history, examination, and review of the patient’s medication list, there are some clues on exam that may suggest a certain type of medication at play.

Continue to: Antimalarials

Antimalarials. Chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, and quinacrine can cause blue-black skin hyperpigmentation in as many as 25% of patients. Common locations include the shins, face, oral mucosa, and subungual skin. This hyperpigmentation rarely fully resolves.2

Amiodarone. Hyperpigmentation secondary to amiodarone use typically is slate-gray in color and involves photoexposed skin. Patients should be counseled that pigmentation may—but does not always—fade with time after discontinuation of the drug.2

Heavy metals. Argyria results from exposure to silver, either ingested orally or applied externally. A common cause of argyria is ingestion of excessive amounts of silver-containing supplements.3 Affected patients present with diffuse slate-gray discoloration of the skin.

Other metals implicated in skin hyperpigmentation include arsenic, gold, mercury, and iron. Review of all supplements and herbal remedies in patients presenting with skin hyperpigmentation is crucial.

Bleomycin is a chemotherapeutic agent with a rare but unique adverse effect of inducing flagellate hyperpigmentation that favors the chest, abdomen, or back. This may be induced by trauma or scratching and is often transient. Hyperpigmentation can occur secondary to either intravenous or intralesional injection of the medication.2

Continue to: In addition to medication...

In addition to medication- or supplement-induced hyperpigmentation, there is a physiologic source that should be considered when a patient presents with lower-extremity hyperpigmentation:

Stasis hyperpigmentation. Patients with chronic venous insufficiency may present with hyperpigmentation of the lower extremities. Commonly due to dysfunctional venous valves or obstruction, stasis hyperpigmentation manifests with red-brown discoloration from dermal hemosiderin deposition.4

Unlike our patient, those with stasis hyperpigmentation may present symptomatically, with associated dry skin, pruritus, induration, and inflammation. Treatment involves management of the underlying venous insufficiency.4

When there’s no obvious cause, be prepared to dig deeper

At the time of initial assessment, a thorough review of systems and detailed medication history, including over-the-counter supplements, should be obtained. Physical examination revealing diffuse, generalized hyperpigmentation with no reliable culprit medication in the patient’s history warrants further laboratory evaluation. This includes ordering renal and liver studies and tests for thyroid-stimulating hormone and ferritin and cortisol levels to rule out metabolic or endocrine hyperpigmentation disorders.

Stopping the offending medication is the first step

Discontinuation of the offending medication may result in mild improvement in skin hyperpigmentation over time. Some patients may not experience any improvement. If improvement occurs, it is important to educate patients that it can take several months to years. Dermatology guidelines favor discontinuation of antibiotics for acne or rosacea after 3 to 6 months to avoid bacterial resistance.5 Worsening hyperpigmentation despite medication discontinuation warrants further work-up.

Patients who are distressed by persistent hyperpigmentation can be treated using picosecond or Q-switched lasers.6

Our patient was advised to discontinue the minocycline. Three test spots on his face were treated with pulsed-dye laser, carbon dioxide laser, and dermabrasion. The patient noted that the spots responded better to the carbon dioxide laser and dermabrasion compared to the pulsed-dye laser. He did not follow up for further treatment.

1. Wetter DA. Minocycline hyperpigmentation. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:e33. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.02.013

2. Chang MW. Chapter 67: Disorders of hyperpigmentation. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, et al (eds). Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1122-1124.

3. Bowden LP, Royer MC, Hallman JR, et al. Rapid onset of argyria induced by a silver-containing dietary supplement. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:832-835. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2011.01755.x

4. Patterson J. Stasis dermatitis. In: Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier;2010: 121-153.

5. Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-73.e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037

6. Barrett T, de Zwaan S. Picosecond alexandrite laser is superior to Q-switched Nd:YAG laser in treatment of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation: a case study and review of the literature. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2018;20:387-390. doi: 10.1080/14764172.2017.1418514

1. Wetter DA. Minocycline hyperpigmentation. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:e33. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.02.013

2. Chang MW. Chapter 67: Disorders of hyperpigmentation. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, et al (eds). Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1122-1124.

3. Bowden LP, Royer MC, Hallman JR, et al. Rapid onset of argyria induced by a silver-containing dietary supplement. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:832-835. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2011.01755.x

4. Patterson J. Stasis dermatitis. In: Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier;2010: 121-153.

5. Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-73.e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037

6. Barrett T, de Zwaan S. Picosecond alexandrite laser is superior to Q-switched Nd:YAG laser in treatment of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation: a case study and review of the literature. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2018;20:387-390. doi: 10.1080/14764172.2017.1418514

Extensive scarring alopecia and widespread rash

A 23-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and a history of poor adherence to recommended treatment presented with a widespread pruritic rash and diffuse hair loss. The rash had rapidly progressed following sun exposure during the summer. The patient cited her mental health status (anxiety, depression), socioeconomic factors, and challenges with prescription insurance coverage as reasons for nonadherence to treatment.

Clinical examination revealed diffuse scarring alopecia and abnormal pigmentation of the scalp (FIGURE 1A), as well as large, red-brown, scaly, atrophic plaques on the face, ears, extremities, back, and buttocks (FIGURES 1B and 1C).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Generalized chronic cutaneouslupus erythematosus

The clinical features of our patient were most consistent with generalized chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE), which is 1 of 3 subtypes of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE). The other 2 are acute and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ACLE and SCLE, respectively). CCLE is further divided into 3 distinct entities: discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), chilblain lupus erythematosus, and lupus erythematosus panniculitis.

Distinguishing between the different forms of cutaneous lupus can be challenging; diagnosis is based on differences in clinical features and duration of skin changes, as well as biopsy and lab results.1 The clinical features of our patient were most consistent with DLE, based on the scarring alopecia with scaly atrophic plaques, dyspigmentation, and exacerbation following sun exposure.

DLE is the most common form of CCLE and frequently manifests in a localized, photosensitive distribution involving the scalp, ears, and/or face.2 Less commonly, it can demonstrate a more generalized distribution involving the trunk and/or extremities (reported incidence of 1.04 per 100,000 people).3 Longstanding DLE lesions commonly exhibit scarring and dyspigmentation. DLE occurs in approximately 15% to 30% of SLE patients,4 whereas about 10% of patients with DLE will progress to SLE.3

Positive antinuclear antibodies (ANA) are found in 54% of patients with CCLE, compared to 74% and 81% of patients with SCLE and ACLE, respectively.5 Thus, a negative ANA should not rule out the possibility of CLE.

Comprehensive lab work and biopsy could expose a systemic origin

While our patient already had a diagnosis of SLE, many patients will present with no prior history of autoimmune connective tissue disease, and, in that case, the objective should be to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate for systemic involvement. This includes a thorough review of systems; skin biopsy; complete blood count; liver function tests; urinalysis; and measurement of creatinine, inflammatory markers, ANA, extractable nuclear antigens, double-stranded DNA, complement levels (C3, C4, total), and antiphospholipid antibodies.6

Continue to: Biopsy

Biopsy features of DLE include vacuolar interface dermatitis, basement membrane zone thickening, follicular plugging, superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphohistiocytic inflammation with plasma cells, and increased mucin deposition. Direct immunofluorescence biopsy may show a continuous granular immunoglobulin (Ig) G/IgA/IgM and C3 band at the basement membrane zone.

Abnormal serologic tests may support the diagnosis of SLE based on American College of Rheumatology criteria and could suggest additional organ involvement or associated conditions, such as lupus nephritis or antiphospholipid syndrome (respectively). Currently, no clear consensus exists on monitoring patients with cutaneous lupus for systemic disease.

A gamut of skin-changing conditions should be considered

The differential diagnosis in this case includes SCLE, dermatitis, tinea corporis, cutaneous drug eruptions, and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

SCLE classically manifests with annular or psoriasiform lesions on the sun-exposed areas of the upper trunk (eg, the chest, neck, and upper extremities), while the central face and scalp are typically spared. Differentiating between generalized DLE and SCLE may be the most difficult, given similarities in the associated skin changes.

Dermatitis (atopic or contact) manifests as pruritic erythematous eczematous plaques, most commonly involving the flexural areas in atopic dermatitis and an exposure-dependent distribution pattern in contact dermatitis. The patient may have a history of atopy.

Continue to: Tinea corporis

Tinea corporis will manifest with annular scaly patches or plaques and may demonstrate erythematous papules around hair follicles in Majocchi granuloma. A positive potassium hydroxide exam demonstrating fungal hyphae confirms the diagnosis.

Cutaneous drug eruptions can have various morphologies and timing of onset. Certain photosensitive drug reactions can be triggered or exacerbated with sun exposure. Therefore, it is necessary to obtain a thorough medication history, including any new medications that were started within the past 4 to 6 weeks, although onset can be delayed beyond this timeframe.

GVHD is a complication that more commonly follows allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants, although it may be seen following solid-organ transplantation or transfusion of nonirradiated blood. Chronic GVHD has an onset ≥ 100 days after transplant and is divided into nonsclerotic (lichenoid, atopic dermatitis-like, psoriasiform, poikilodermatous) and sclerotic morphologies.

Successful Tx requires adherence but may not prevent flare-ups

First-line treatment options for severe and widespread skin manifestations of CLE include photoprotection, smoking cessation, topical corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine, and systemic corticosteroids. Second-line treatments include chloroquine, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil; thalidomide or lenalidomide may be considered for patients with refractory disease.7,8

With successful treatment and photoprotection, patients may achieve significant skin clearing. Occasional flares, especially during warmer months, may occur if they are not diligent about photoprotection. Systemic treatments will also improve the patient’s systemic symptoms if the patient has concomitant SLE.

Our patient was advised to use topical steroids and to restart hydroxychloroquine 300 mg/d and mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg/d (a regimen with which she had previously been nonadherent). The patient followed up with her family physician for assessment of her other medical issues. No new interventions for her mental health were initiated during this visit, as the severity of her depression was considered mild. She was referred to a case manager to navigate multiple medical appointments and prescription insurance coverage issues. The patient’s dose of mycophenolate mofetil was increased gradually to 3 g/d, and the patient experienced improvement in both her cutaneous lesions and systemic symptoms.

1. Petty AJ, Floyd L, Henderson C, et al. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: progress and challenges. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020;20:12. doi: 10.1007/s11882-020-00906-8

2. Kuhn A, Landmann A. The classification and diagnosis of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:14-19. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.021

3. Durosaro O, Davis MDP, Reed KB, et al. Incidence of cutaneous lupus erythematosus, 1965-2005: a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:249-253. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.21

4. Merola JF. Overview of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. UpToDate. Updated September 19, 2021. Accessed February 17, 2022. www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-cutaneous-lupus-erythematosus

5. Biazar C, Sigges J, Patsinakidis N, et al. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: first multicenter database analysis of 1002 patients from the European Society of Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (EUSCLE). Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12:444-454. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2012.08.019

6. O’Brien JC, Chong BF. not just skin deep: systemic disease involvement in patients with cutaneous lupus. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S69-S74. doi: 10.1016/j.jisp.2016.09.001

7. Kuhn A, Ruland V, Bonsmann G. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: update of therapeutic options part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e179-e193. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.06.018

8. Kindle SA, Wetter DA, Davis MDP, et al. Lenalidomide treatment of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: the Mayo Clinic experience. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:e431-e439. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13226

A 23-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and a history of poor adherence to recommended treatment presented with a widespread pruritic rash and diffuse hair loss. The rash had rapidly progressed following sun exposure during the summer. The patient cited her mental health status (anxiety, depression), socioeconomic factors, and challenges with prescription insurance coverage as reasons for nonadherence to treatment.

Clinical examination revealed diffuse scarring alopecia and abnormal pigmentation of the scalp (FIGURE 1A), as well as large, red-brown, scaly, atrophic plaques on the face, ears, extremities, back, and buttocks (FIGURES 1B and 1C).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Generalized chronic cutaneouslupus erythematosus

The clinical features of our patient were most consistent with generalized chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE), which is 1 of 3 subtypes of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE). The other 2 are acute and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ACLE and SCLE, respectively). CCLE is further divided into 3 distinct entities: discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), chilblain lupus erythematosus, and lupus erythematosus panniculitis.

Distinguishing between the different forms of cutaneous lupus can be challenging; diagnosis is based on differences in clinical features and duration of skin changes, as well as biopsy and lab results.1 The clinical features of our patient were most consistent with DLE, based on the scarring alopecia with scaly atrophic plaques, dyspigmentation, and exacerbation following sun exposure.

DLE is the most common form of CCLE and frequently manifests in a localized, photosensitive distribution involving the scalp, ears, and/or face.2 Less commonly, it can demonstrate a more generalized distribution involving the trunk and/or extremities (reported incidence of 1.04 per 100,000 people).3 Longstanding DLE lesions commonly exhibit scarring and dyspigmentation. DLE occurs in approximately 15% to 30% of SLE patients,4 whereas about 10% of patients with DLE will progress to SLE.3

Positive antinuclear antibodies (ANA) are found in 54% of patients with CCLE, compared to 74% and 81% of patients with SCLE and ACLE, respectively.5 Thus, a negative ANA should not rule out the possibility of CLE.

Comprehensive lab work and biopsy could expose a systemic origin

While our patient already had a diagnosis of SLE, many patients will present with no prior history of autoimmune connective tissue disease, and, in that case, the objective should be to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate for systemic involvement. This includes a thorough review of systems; skin biopsy; complete blood count; liver function tests; urinalysis; and measurement of creatinine, inflammatory markers, ANA, extractable nuclear antigens, double-stranded DNA, complement levels (C3, C4, total), and antiphospholipid antibodies.6

Continue to: Biopsy

Biopsy features of DLE include vacuolar interface dermatitis, basement membrane zone thickening, follicular plugging, superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphohistiocytic inflammation with plasma cells, and increased mucin deposition. Direct immunofluorescence biopsy may show a continuous granular immunoglobulin (Ig) G/IgA/IgM and C3 band at the basement membrane zone.

Abnormal serologic tests may support the diagnosis of SLE based on American College of Rheumatology criteria and could suggest additional organ involvement or associated conditions, such as lupus nephritis or antiphospholipid syndrome (respectively). Currently, no clear consensus exists on monitoring patients with cutaneous lupus for systemic disease.

A gamut of skin-changing conditions should be considered

The differential diagnosis in this case includes SCLE, dermatitis, tinea corporis, cutaneous drug eruptions, and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

SCLE classically manifests with annular or psoriasiform lesions on the sun-exposed areas of the upper trunk (eg, the chest, neck, and upper extremities), while the central face and scalp are typically spared. Differentiating between generalized DLE and SCLE may be the most difficult, given similarities in the associated skin changes.

Dermatitis (atopic or contact) manifests as pruritic erythematous eczematous plaques, most commonly involving the flexural areas in atopic dermatitis and an exposure-dependent distribution pattern in contact dermatitis. The patient may have a history of atopy.

Continue to: Tinea corporis

Tinea corporis will manifest with annular scaly patches or plaques and may demonstrate erythematous papules around hair follicles in Majocchi granuloma. A positive potassium hydroxide exam demonstrating fungal hyphae confirms the diagnosis.

Cutaneous drug eruptions can have various morphologies and timing of onset. Certain photosensitive drug reactions can be triggered or exacerbated with sun exposure. Therefore, it is necessary to obtain a thorough medication history, including any new medications that were started within the past 4 to 6 weeks, although onset can be delayed beyond this timeframe.

GVHD is a complication that more commonly follows allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants, although it may be seen following solid-organ transplantation or transfusion of nonirradiated blood. Chronic GVHD has an onset ≥ 100 days after transplant and is divided into nonsclerotic (lichenoid, atopic dermatitis-like, psoriasiform, poikilodermatous) and sclerotic morphologies.

Successful Tx requires adherence but may not prevent flare-ups

First-line treatment options for severe and widespread skin manifestations of CLE include photoprotection, smoking cessation, topical corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine, and systemic corticosteroids. Second-line treatments include chloroquine, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil; thalidomide or lenalidomide may be considered for patients with refractory disease.7,8

With successful treatment and photoprotection, patients may achieve significant skin clearing. Occasional flares, especially during warmer months, may occur if they are not diligent about photoprotection. Systemic treatments will also improve the patient’s systemic symptoms if the patient has concomitant SLE.

Our patient was advised to use topical steroids and to restart hydroxychloroquine 300 mg/d and mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg/d (a regimen with which she had previously been nonadherent). The patient followed up with her family physician for assessment of her other medical issues. No new interventions for her mental health were initiated during this visit, as the severity of her depression was considered mild. She was referred to a case manager to navigate multiple medical appointments and prescription insurance coverage issues. The patient’s dose of mycophenolate mofetil was increased gradually to 3 g/d, and the patient experienced improvement in both her cutaneous lesions and systemic symptoms.

A 23-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and a history of poor adherence to recommended treatment presented with a widespread pruritic rash and diffuse hair loss. The rash had rapidly progressed following sun exposure during the summer. The patient cited her mental health status (anxiety, depression), socioeconomic factors, and challenges with prescription insurance coverage as reasons for nonadherence to treatment.

Clinical examination revealed diffuse scarring alopecia and abnormal pigmentation of the scalp (FIGURE 1A), as well as large, red-brown, scaly, atrophic plaques on the face, ears, extremities, back, and buttocks (FIGURES 1B and 1C).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Generalized chronic cutaneouslupus erythematosus

The clinical features of our patient were most consistent with generalized chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE), which is 1 of 3 subtypes of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE). The other 2 are acute and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ACLE and SCLE, respectively). CCLE is further divided into 3 distinct entities: discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), chilblain lupus erythematosus, and lupus erythematosus panniculitis.

Distinguishing between the different forms of cutaneous lupus can be challenging; diagnosis is based on differences in clinical features and duration of skin changes, as well as biopsy and lab results.1 The clinical features of our patient were most consistent with DLE, based on the scarring alopecia with scaly atrophic plaques, dyspigmentation, and exacerbation following sun exposure.

DLE is the most common form of CCLE and frequently manifests in a localized, photosensitive distribution involving the scalp, ears, and/or face.2 Less commonly, it can demonstrate a more generalized distribution involving the trunk and/or extremities (reported incidence of 1.04 per 100,000 people).3 Longstanding DLE lesions commonly exhibit scarring and dyspigmentation. DLE occurs in approximately 15% to 30% of SLE patients,4 whereas about 10% of patients with DLE will progress to SLE.3

Positive antinuclear antibodies (ANA) are found in 54% of patients with CCLE, compared to 74% and 81% of patients with SCLE and ACLE, respectively.5 Thus, a negative ANA should not rule out the possibility of CLE.

Comprehensive lab work and biopsy could expose a systemic origin

While our patient already had a diagnosis of SLE, many patients will present with no prior history of autoimmune connective tissue disease, and, in that case, the objective should be to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate for systemic involvement. This includes a thorough review of systems; skin biopsy; complete blood count; liver function tests; urinalysis; and measurement of creatinine, inflammatory markers, ANA, extractable nuclear antigens, double-stranded DNA, complement levels (C3, C4, total), and antiphospholipid antibodies.6

Continue to: Biopsy

Biopsy features of DLE include vacuolar interface dermatitis, basement membrane zone thickening, follicular plugging, superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphohistiocytic inflammation with plasma cells, and increased mucin deposition. Direct immunofluorescence biopsy may show a continuous granular immunoglobulin (Ig) G/IgA/IgM and C3 band at the basement membrane zone.

Abnormal serologic tests may support the diagnosis of SLE based on American College of Rheumatology criteria and could suggest additional organ involvement or associated conditions, such as lupus nephritis or antiphospholipid syndrome (respectively). Currently, no clear consensus exists on monitoring patients with cutaneous lupus for systemic disease.

A gamut of skin-changing conditions should be considered

The differential diagnosis in this case includes SCLE, dermatitis, tinea corporis, cutaneous drug eruptions, and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

SCLE classically manifests with annular or psoriasiform lesions on the sun-exposed areas of the upper trunk (eg, the chest, neck, and upper extremities), while the central face and scalp are typically spared. Differentiating between generalized DLE and SCLE may be the most difficult, given similarities in the associated skin changes.

Dermatitis (atopic or contact) manifests as pruritic erythematous eczematous plaques, most commonly involving the flexural areas in atopic dermatitis and an exposure-dependent distribution pattern in contact dermatitis. The patient may have a history of atopy.

Continue to: Tinea corporis

Tinea corporis will manifest with annular scaly patches or plaques and may demonstrate erythematous papules around hair follicles in Majocchi granuloma. A positive potassium hydroxide exam demonstrating fungal hyphae confirms the diagnosis.

Cutaneous drug eruptions can have various morphologies and timing of onset. Certain photosensitive drug reactions can be triggered or exacerbated with sun exposure. Therefore, it is necessary to obtain a thorough medication history, including any new medications that were started within the past 4 to 6 weeks, although onset can be delayed beyond this timeframe.

GVHD is a complication that more commonly follows allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants, although it may be seen following solid-organ transplantation or transfusion of nonirradiated blood. Chronic GVHD has an onset ≥ 100 days after transplant and is divided into nonsclerotic (lichenoid, atopic dermatitis-like, psoriasiform, poikilodermatous) and sclerotic morphologies.

Successful Tx requires adherence but may not prevent flare-ups

First-line treatment options for severe and widespread skin manifestations of CLE include photoprotection, smoking cessation, topical corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine, and systemic corticosteroids. Second-line treatments include chloroquine, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil; thalidomide or lenalidomide may be considered for patients with refractory disease.7,8

With successful treatment and photoprotection, patients may achieve significant skin clearing. Occasional flares, especially during warmer months, may occur if they are not diligent about photoprotection. Systemic treatments will also improve the patient’s systemic symptoms if the patient has concomitant SLE.

Our patient was advised to use topical steroids and to restart hydroxychloroquine 300 mg/d and mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg/d (a regimen with which she had previously been nonadherent). The patient followed up with her family physician for assessment of her other medical issues. No new interventions for her mental health were initiated during this visit, as the severity of her depression was considered mild. She was referred to a case manager to navigate multiple medical appointments and prescription insurance coverage issues. The patient’s dose of mycophenolate mofetil was increased gradually to 3 g/d, and the patient experienced improvement in both her cutaneous lesions and systemic symptoms.

1. Petty AJ, Floyd L, Henderson C, et al. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: progress and challenges. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020;20:12. doi: 10.1007/s11882-020-00906-8

2. Kuhn A, Landmann A. The classification and diagnosis of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:14-19. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.021

3. Durosaro O, Davis MDP, Reed KB, et al. Incidence of cutaneous lupus erythematosus, 1965-2005: a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:249-253. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.21

4. Merola JF. Overview of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. UpToDate. Updated September 19, 2021. Accessed February 17, 2022. www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-cutaneous-lupus-erythematosus

5. Biazar C, Sigges J, Patsinakidis N, et al. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: first multicenter database analysis of 1002 patients from the European Society of Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (EUSCLE). Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12:444-454. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2012.08.019

6. O’Brien JC, Chong BF. not just skin deep: systemic disease involvement in patients with cutaneous lupus. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S69-S74. doi: 10.1016/j.jisp.2016.09.001

7. Kuhn A, Ruland V, Bonsmann G. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: update of therapeutic options part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e179-e193. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.06.018

8. Kindle SA, Wetter DA, Davis MDP, et al. Lenalidomide treatment of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: the Mayo Clinic experience. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:e431-e439. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13226

1. Petty AJ, Floyd L, Henderson C, et al. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: progress and challenges. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020;20:12. doi: 10.1007/s11882-020-00906-8

2. Kuhn A, Landmann A. The classification and diagnosis of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:14-19. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.021

3. Durosaro O, Davis MDP, Reed KB, et al. Incidence of cutaneous lupus erythematosus, 1965-2005: a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:249-253. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.21

4. Merola JF. Overview of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. UpToDate. Updated September 19, 2021. Accessed February 17, 2022. www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-cutaneous-lupus-erythematosus

5. Biazar C, Sigges J, Patsinakidis N, et al. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: first multicenter database analysis of 1002 patients from the European Society of Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (EUSCLE). Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12:444-454. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2012.08.019

6. O’Brien JC, Chong BF. not just skin deep: systemic disease involvement in patients with cutaneous lupus. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S69-S74. doi: 10.1016/j.jisp.2016.09.001

7. Kuhn A, Ruland V, Bonsmann G. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: update of therapeutic options part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e179-e193. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.06.018

8. Kindle SA, Wetter DA, Davis MDP, et al. Lenalidomide treatment of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: the Mayo Clinic experience. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:e431-e439. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13226

Generalized pustular eruption

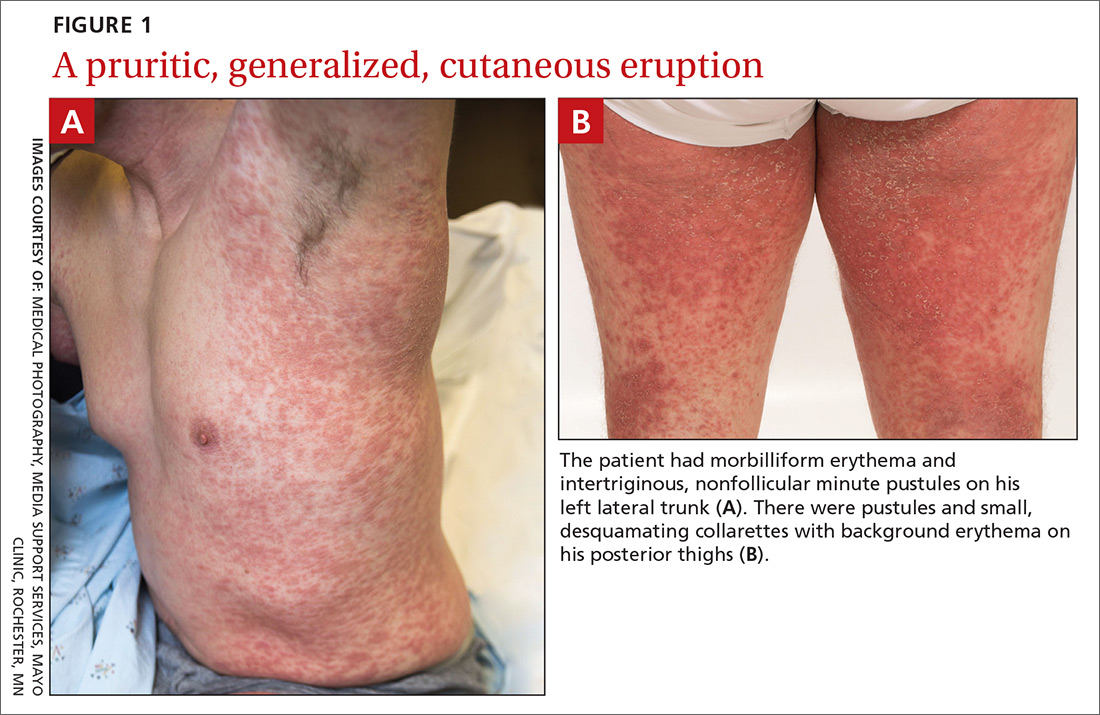

A 38-year-old man sought care in the emergency department for an acute, pruritic, generalized cutaneous eruption that manifested in the intertriginous areas of the inner thighs, antecubital fossae, and axilla (FIGURE 1A). He reported associated chills, a 15-pound weight gain, and swelling of his inner thighs. Two weeks before presentation, he had received azithromycin for an upper respiratory tract infection. He was unsure if the rash developed prior to or after taking the medication. He was not taking any other medications and had no history of skin conditions.

On examination, the patient was afebrile and had bilateral thigh edema. Skin examination revealed background erythema with morbilliform papules, plaques, and patches on the bilateral flanks, back, buttocks, arms, legs, and central neck. Pinpoint pustules were present in the intertriginous sites and on the low back and buttocks. The laboratory evaluation revealed leukocytosis (11.0 × 109 cells/L), increased levels of neutrophils and eosinophils, and an elevated C-reactive protein level (12.8 mg/L). The remaining laboratory results were unremarkable. The patient was referred to Dermatology.

An examination by the dermatologist 3 days later revealed small areas of annular desquamation with a few pinpoint pustules, mostly located on the inner thighs and buttocks (FIGURE 1B). Skin biopsies were taken from the anterior hip region. The histopathology revealed subacute dermatitis with mixed dermal inflammatory cells, including neutrophils and eosinophils, and discrete subcorneal spongiform pustules.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)

The acute rash with minute pustules and associated leukocytosis with neutrophilia and eosinophilia led to an early diagnosis of AGEP, which may have been triggered by azithromycin—the patient’s only recent medication. AGEP is a severe cutaneous eruption that may be associated with systemic involvement. Medications are usually implicated, and patients often seek urgent evaluation.

AGEP typically begins as an acute eruption in the intertriginous sites of the axilla, groin, and neck, but often becomes more generalized.1,2 The diagnosis is strongly suggested by the condition’s key features: fever (97% of cases) and leukocytosis (87%) with neutrophilia (91%) and eosinophilia (30%); leukocytosis peaks 4 days after pustulosis occurs and lasts for about 12 days.1 Although common, fever is not always documented in patients with AGEP. 3 (Our patient was a case in point.) While not a key characteristic of AGEP, our patient’s weight gain was likely explained by the severe edema secondary to his inflammatory skin eruption.

Medications are implicated, but pathophysiology is unknown

In approximately 90% of AGEP cases, medications such as antibiotics and calcium channel blockers are implicated; however, the lack of such an association does not preclude the diagnosis.1,4 In cases of drug reactions, the eruption typically develops 1 to 2 days after a medication is begun, and the pustules typically resolve in fewer than 15 days.5 In 17% of patients, systemic involvement can occur and can include the liver, kidneys, bone marrow, and lungs.6 A physical exam, review of systems, and a laboratory evaluation can help rule out systemic involvement and guide additional testing.

AGEP has an incidence of 1 to 5 cases per million people per year, affecting women slightly more frequently than men.7 While the pathophysiology is not well understood, AGEP and its differential diagnoses are categorized as T cell-related inflammatory responses.4,7

Distinguishing AGEP from some look-alikes

There are at least 4 severe cutaneous eruptions that might be confused with AGEP, all of which may be associated with fever. They include: drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome; Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS); toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN); and pustular psoriasis.8-10 The clinical features that may help differentiate these conditions from AGEP include timeline, mucocutaneous features, organ system involvement, and histopathologic findings.4,8

DRESS occurs 2 to 6 weeks after drug exposure, rather than a few days, as is seen with AGEP. It often involves morbilliform erythema and facial edema with substantial eosinophilia and possible nephritis, pneumonitis, myocarditis, and thyroiditis.9 Unlike AGEP, DRESS does not have a predilection for intertriginous anatomic locations.

SJS and TEN occur 1 to 3 weeks after drug exposure. These conditions manifest with the development of bullae, atypical targetoid lesions, painful dusky erythema, epidermal necrosis, and mucosal involvement at multiple sites. Tubular nephritis, tracheobronchial necrosis, and multisystem organ failure can occur, with reported mortality rates of 5% to 35%.8,11

Pustular psoriasis is frequently confused with AGEP. However, AGEP usually develops fewer than 2 days after drug exposure, with pustules that begin in intertriginous sites, and there is associated neutrophilia and possible organ involvement.1,8 Patients who have AGEP typically do not have a history of psoriasis, while patients with pustular psoriasis often do.7 A history of drug reaction is uncommon with pustular psoriasis (although rapid tapering of systemic corticosteroids in patients with psoriasis can trigger the development of pustular psoriasis), whereas a previous history of drug reaction is common in AGEP.3,7

Discontinue medication, treat with corticosteroids

Patients who have AGEP, including those with systemic involvement, generally improve after the offending drug is discontinued and treatment with topical corticosteroids is initiated.6 A brief course of systemic corticosteroids can also be considered for patients with severe skin involvement or systemic involvement.3

Our patient was prescribed topical corticosteroid wet dressing treatments twice daily for 2 weeks. At the 2-week follow-up visit, the rash had completely cleared, and only minimal residual erythema was noted (FIGURE 2). The patient was instructed to avoid azithromycin.

CORRESPONDENCE

David A. Wetter, MD, Department of Dermatology, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905; wetter.david@mayo.edu.

1. Roujeau JC, Bioulac-Sage P, Bourseau C, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Analysis of 63 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1333-1338.

2. Lee HY, Chou D, Pang SM, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: analysis of cases managed in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:507-512.

3. Alniemi DT, Wetter DA, Bridges AG, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: clinical characteristics, etiologic associations, treatments, and outcomes in a series of 28 patients at Mayo Clinic, 1996-2013. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:405-414.

4. Bouvresse S, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Ortonne N, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis, DRESS, AGEP: do overlap cases exist? Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:72.

5. Sidoroff A, Halevy S, Bavinck JN, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—a clinical reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:113-119.

6. Hotz C, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Haddad C, et al. Systemic involvement of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a retrospective study on 58 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1223-1232.

7. Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:E1214.

8. Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: Part II. Management and therapeutics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:709.e1-e9.

9. Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: Part I. Clinical perspectives. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:693.e1-e14.

10. Bastuji-Garin S, Rzany B, Stern RS, et al. Clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:92-96.

11. Roujeau JC. The spectrum of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a clinical classification. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:28S-30S.

A 38-year-old man sought care in the emergency department for an acute, pruritic, generalized cutaneous eruption that manifested in the intertriginous areas of the inner thighs, antecubital fossae, and axilla (FIGURE 1A). He reported associated chills, a 15-pound weight gain, and swelling of his inner thighs. Two weeks before presentation, he had received azithromycin for an upper respiratory tract infection. He was unsure if the rash developed prior to or after taking the medication. He was not taking any other medications and had no history of skin conditions.

On examination, the patient was afebrile and had bilateral thigh edema. Skin examination revealed background erythema with morbilliform papules, plaques, and patches on the bilateral flanks, back, buttocks, arms, legs, and central neck. Pinpoint pustules were present in the intertriginous sites and on the low back and buttocks. The laboratory evaluation revealed leukocytosis (11.0 × 109 cells/L), increased levels of neutrophils and eosinophils, and an elevated C-reactive protein level (12.8 mg/L). The remaining laboratory results were unremarkable. The patient was referred to Dermatology.

An examination by the dermatologist 3 days later revealed small areas of annular desquamation with a few pinpoint pustules, mostly located on the inner thighs and buttocks (FIGURE 1B). Skin biopsies were taken from the anterior hip region. The histopathology revealed subacute dermatitis with mixed dermal inflammatory cells, including neutrophils and eosinophils, and discrete subcorneal spongiform pustules.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)

The acute rash with minute pustules and associated leukocytosis with neutrophilia and eosinophilia led to an early diagnosis of AGEP, which may have been triggered by azithromycin—the patient’s only recent medication. AGEP is a severe cutaneous eruption that may be associated with systemic involvement. Medications are usually implicated, and patients often seek urgent evaluation.

AGEP typically begins as an acute eruption in the intertriginous sites of the axilla, groin, and neck, but often becomes more generalized.1,2 The diagnosis is strongly suggested by the condition’s key features: fever (97% of cases) and leukocytosis (87%) with neutrophilia (91%) and eosinophilia (30%); leukocytosis peaks 4 days after pustulosis occurs and lasts for about 12 days.1 Although common, fever is not always documented in patients with AGEP. 3 (Our patient was a case in point.) While not a key characteristic of AGEP, our patient’s weight gain was likely explained by the severe edema secondary to his inflammatory skin eruption.

Medications are implicated, but pathophysiology is unknown

In approximately 90% of AGEP cases, medications such as antibiotics and calcium channel blockers are implicated; however, the lack of such an association does not preclude the diagnosis.1,4 In cases of drug reactions, the eruption typically develops 1 to 2 days after a medication is begun, and the pustules typically resolve in fewer than 15 days.5 In 17% of patients, systemic involvement can occur and can include the liver, kidneys, bone marrow, and lungs.6 A physical exam, review of systems, and a laboratory evaluation can help rule out systemic involvement and guide additional testing.

AGEP has an incidence of 1 to 5 cases per million people per year, affecting women slightly more frequently than men.7 While the pathophysiology is not well understood, AGEP and its differential diagnoses are categorized as T cell-related inflammatory responses.4,7

Distinguishing AGEP from some look-alikes

There are at least 4 severe cutaneous eruptions that might be confused with AGEP, all of which may be associated with fever. They include: drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome; Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS); toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN); and pustular psoriasis.8-10 The clinical features that may help differentiate these conditions from AGEP include timeline, mucocutaneous features, organ system involvement, and histopathologic findings.4,8

DRESS occurs 2 to 6 weeks after drug exposure, rather than a few days, as is seen with AGEP. It often involves morbilliform erythema and facial edema with substantial eosinophilia and possible nephritis, pneumonitis, myocarditis, and thyroiditis.9 Unlike AGEP, DRESS does not have a predilection for intertriginous anatomic locations.

SJS and TEN occur 1 to 3 weeks after drug exposure. These conditions manifest with the development of bullae, atypical targetoid lesions, painful dusky erythema, epidermal necrosis, and mucosal involvement at multiple sites. Tubular nephritis, tracheobronchial necrosis, and multisystem organ failure can occur, with reported mortality rates of 5% to 35%.8,11

Pustular psoriasis is frequently confused with AGEP. However, AGEP usually develops fewer than 2 days after drug exposure, with pustules that begin in intertriginous sites, and there is associated neutrophilia and possible organ involvement.1,8 Patients who have AGEP typically do not have a history of psoriasis, while patients with pustular psoriasis often do.7 A history of drug reaction is uncommon with pustular psoriasis (although rapid tapering of systemic corticosteroids in patients with psoriasis can trigger the development of pustular psoriasis), whereas a previous history of drug reaction is common in AGEP.3,7

Discontinue medication, treat with corticosteroids

Patients who have AGEP, including those with systemic involvement, generally improve after the offending drug is discontinued and treatment with topical corticosteroids is initiated.6 A brief course of systemic corticosteroids can also be considered for patients with severe skin involvement or systemic involvement.3

Our patient was prescribed topical corticosteroid wet dressing treatments twice daily for 2 weeks. At the 2-week follow-up visit, the rash had completely cleared, and only minimal residual erythema was noted (FIGURE 2). The patient was instructed to avoid azithromycin.

CORRESPONDENCE

David A. Wetter, MD, Department of Dermatology, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905; wetter.david@mayo.edu.

A 38-year-old man sought care in the emergency department for an acute, pruritic, generalized cutaneous eruption that manifested in the intertriginous areas of the inner thighs, antecubital fossae, and axilla (FIGURE 1A). He reported associated chills, a 15-pound weight gain, and swelling of his inner thighs. Two weeks before presentation, he had received azithromycin for an upper respiratory tract infection. He was unsure if the rash developed prior to or after taking the medication. He was not taking any other medications and had no history of skin conditions.

On examination, the patient was afebrile and had bilateral thigh edema. Skin examination revealed background erythema with morbilliform papules, plaques, and patches on the bilateral flanks, back, buttocks, arms, legs, and central neck. Pinpoint pustules were present in the intertriginous sites and on the low back and buttocks. The laboratory evaluation revealed leukocytosis (11.0 × 109 cells/L), increased levels of neutrophils and eosinophils, and an elevated C-reactive protein level (12.8 mg/L). The remaining laboratory results were unremarkable. The patient was referred to Dermatology.

An examination by the dermatologist 3 days later revealed small areas of annular desquamation with a few pinpoint pustules, mostly located on the inner thighs and buttocks (FIGURE 1B). Skin biopsies were taken from the anterior hip region. The histopathology revealed subacute dermatitis with mixed dermal inflammatory cells, including neutrophils and eosinophils, and discrete subcorneal spongiform pustules.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)

The acute rash with minute pustules and associated leukocytosis with neutrophilia and eosinophilia led to an early diagnosis of AGEP, which may have been triggered by azithromycin—the patient’s only recent medication. AGEP is a severe cutaneous eruption that may be associated with systemic involvement. Medications are usually implicated, and patients often seek urgent evaluation.

AGEP typically begins as an acute eruption in the intertriginous sites of the axilla, groin, and neck, but often becomes more generalized.1,2 The diagnosis is strongly suggested by the condition’s key features: fever (97% of cases) and leukocytosis (87%) with neutrophilia (91%) and eosinophilia (30%); leukocytosis peaks 4 days after pustulosis occurs and lasts for about 12 days.1 Although common, fever is not always documented in patients with AGEP. 3 (Our patient was a case in point.) While not a key characteristic of AGEP, our patient’s weight gain was likely explained by the severe edema secondary to his inflammatory skin eruption.

Medications are implicated, but pathophysiology is unknown

In approximately 90% of AGEP cases, medications such as antibiotics and calcium channel blockers are implicated; however, the lack of such an association does not preclude the diagnosis.1,4 In cases of drug reactions, the eruption typically develops 1 to 2 days after a medication is begun, and the pustules typically resolve in fewer than 15 days.5 In 17% of patients, systemic involvement can occur and can include the liver, kidneys, bone marrow, and lungs.6 A physical exam, review of systems, and a laboratory evaluation can help rule out systemic involvement and guide additional testing.

AGEP has an incidence of 1 to 5 cases per million people per year, affecting women slightly more frequently than men.7 While the pathophysiology is not well understood, AGEP and its differential diagnoses are categorized as T cell-related inflammatory responses.4,7

Distinguishing AGEP from some look-alikes

There are at least 4 severe cutaneous eruptions that might be confused with AGEP, all of which may be associated with fever. They include: drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome; Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS); toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN); and pustular psoriasis.8-10 The clinical features that may help differentiate these conditions from AGEP include timeline, mucocutaneous features, organ system involvement, and histopathologic findings.4,8

DRESS occurs 2 to 6 weeks after drug exposure, rather than a few days, as is seen with AGEP. It often involves morbilliform erythema and facial edema with substantial eosinophilia and possible nephritis, pneumonitis, myocarditis, and thyroiditis.9 Unlike AGEP, DRESS does not have a predilection for intertriginous anatomic locations.

SJS and TEN occur 1 to 3 weeks after drug exposure. These conditions manifest with the development of bullae, atypical targetoid lesions, painful dusky erythema, epidermal necrosis, and mucosal involvement at multiple sites. Tubular nephritis, tracheobronchial necrosis, and multisystem organ failure can occur, with reported mortality rates of 5% to 35%.8,11

Pustular psoriasis is frequently confused with AGEP. However, AGEP usually develops fewer than 2 days after drug exposure, with pustules that begin in intertriginous sites, and there is associated neutrophilia and possible organ involvement.1,8 Patients who have AGEP typically do not have a history of psoriasis, while patients with pustular psoriasis often do.7 A history of drug reaction is uncommon with pustular psoriasis (although rapid tapering of systemic corticosteroids in patients with psoriasis can trigger the development of pustular psoriasis), whereas a previous history of drug reaction is common in AGEP.3,7

Discontinue medication, treat with corticosteroids

Patients who have AGEP, including those with systemic involvement, generally improve after the offending drug is discontinued and treatment with topical corticosteroids is initiated.6 A brief course of systemic corticosteroids can also be considered for patients with severe skin involvement or systemic involvement.3

Our patient was prescribed topical corticosteroid wet dressing treatments twice daily for 2 weeks. At the 2-week follow-up visit, the rash had completely cleared, and only minimal residual erythema was noted (FIGURE 2). The patient was instructed to avoid azithromycin.

CORRESPONDENCE

David A. Wetter, MD, Department of Dermatology, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905; wetter.david@mayo.edu.

1. Roujeau JC, Bioulac-Sage P, Bourseau C, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Analysis of 63 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1333-1338.

2. Lee HY, Chou D, Pang SM, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: analysis of cases managed in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:507-512.

3. Alniemi DT, Wetter DA, Bridges AG, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: clinical characteristics, etiologic associations, treatments, and outcomes in a series of 28 patients at Mayo Clinic, 1996-2013. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:405-414.

4. Bouvresse S, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Ortonne N, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis, DRESS, AGEP: do overlap cases exist? Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:72.

5. Sidoroff A, Halevy S, Bavinck JN, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—a clinical reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:113-119.

6. Hotz C, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Haddad C, et al. Systemic involvement of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a retrospective study on 58 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1223-1232.

7. Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:E1214.

8. Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: Part II. Management and therapeutics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:709.e1-e9.

9. Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: Part I. Clinical perspectives. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:693.e1-e14.

10. Bastuji-Garin S, Rzany B, Stern RS, et al. Clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:92-96.

11. Roujeau JC. The spectrum of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a clinical classification. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:28S-30S.

1. Roujeau JC, Bioulac-Sage P, Bourseau C, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Analysis of 63 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1333-1338.

2. Lee HY, Chou D, Pang SM, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: analysis of cases managed in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:507-512.

3. Alniemi DT, Wetter DA, Bridges AG, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: clinical characteristics, etiologic associations, treatments, and outcomes in a series of 28 patients at Mayo Clinic, 1996-2013. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:405-414.

4. Bouvresse S, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Ortonne N, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis, DRESS, AGEP: do overlap cases exist? Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:72.

5. Sidoroff A, Halevy S, Bavinck JN, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—a clinical reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:113-119.

6. Hotz C, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Haddad C, et al. Systemic involvement of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a retrospective study on 58 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1223-1232.

7. Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:E1214.

8. Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: Part II. Management and therapeutics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:709.e1-e9.

9. Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: Part I. Clinical perspectives. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:693.e1-e14.

10. Bastuji-Garin S, Rzany B, Stern RS, et al. Clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:92-96.

11. Roujeau JC. The spectrum of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a clinical classification. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:28S-30S.

Widespread erythematous skin eruption

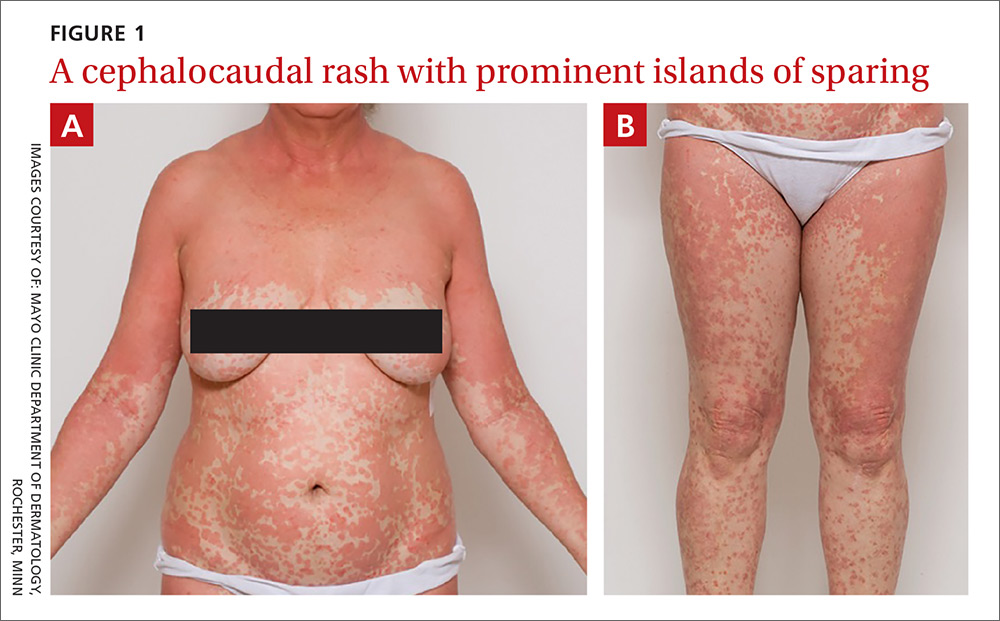

A 48-year-old woman sought care for a widespread pruritic skin eruption that began on her upper back and spread to her arms, lower trunk, and lower legs. She’d had the rash for approximately 2 months and didn’t have any systemic symptoms. A course of prednisone prior to her presentation failed to improve the rash. She denied a personal or family history of rheumatologic or dermatologic disease and reported no new medications or exposures.

On physical exam, she was afebrile and her vital signs were normal. The rash had red-to-salmon–colored scaling patches with discrete and coalescing follicular papules. There were prominent islands of sparing (FIGURE 1).

The patient’s palms were waxy and erythematous and her feet had hyperkeratosis. A complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and lipid panel were normal. A skin biopsy demonstrated psoriasiform dermatitis with alternating areas of orthokeratosis and parakeratosis (the presence of keratinocyte nuclei within the stratum corneum where nuclei typically aren’t found).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pityriasis rubra pilaris

The patient was given a diagnosis of pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) based on her distinctive clinical presentation. This included the presence of prominent islands of sparing, the red-to-salmon scaling patches with follicular papules, the waxy erythema of her palms, and the cephalocaudal progression of her rash. The patient’s skin biopsy findings (in particular, the alternating orthokeratosis/parakeratosis) were also supportive of the diagnosis and helpful to exclude other potential causes of erythroderma (described below).

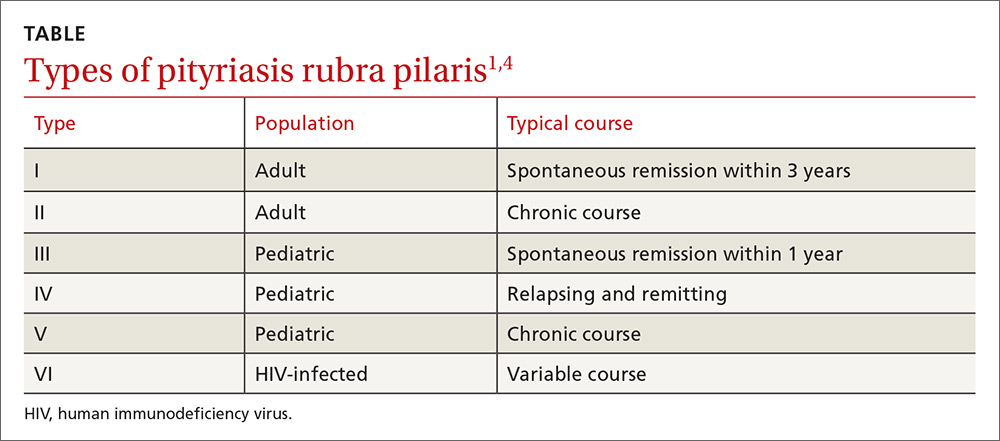

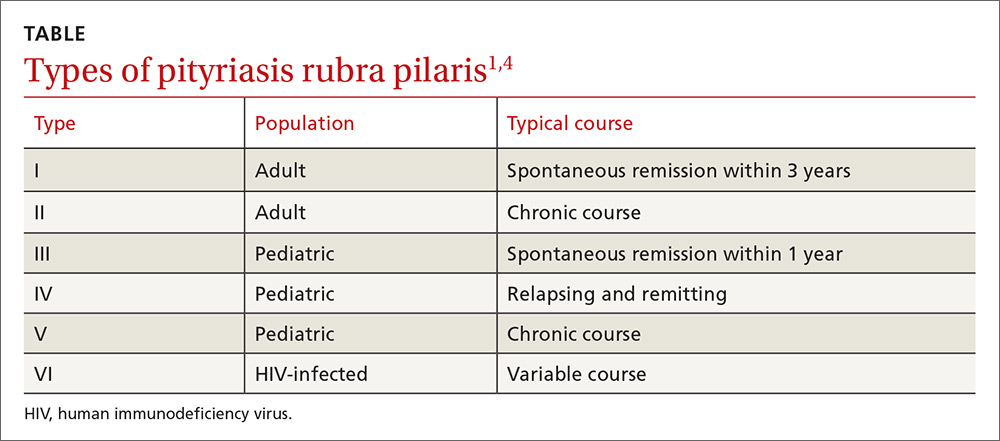

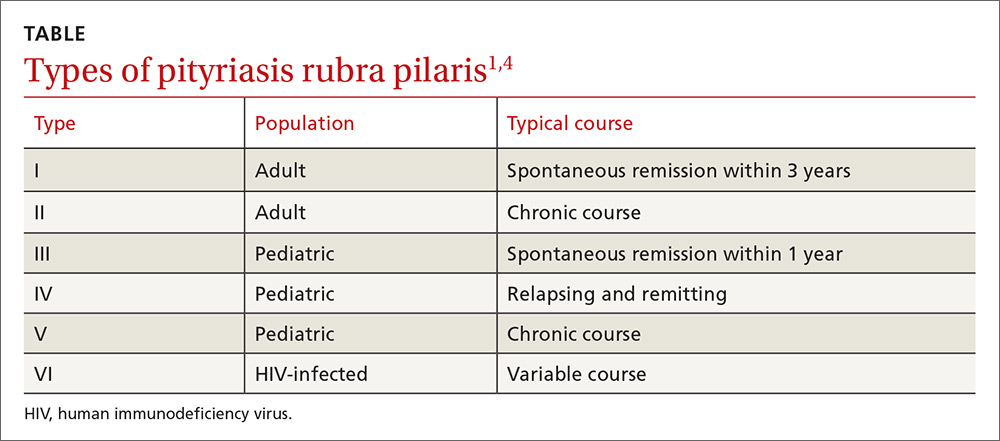

PRP most often affects middle-aged individuals with an equal sex distribution. The etiology and pathogenesis of PRP are not well understood. In rare cases, it has been associated with internal malignancy and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.1,2 PRP may stem from a combination of a dysfunction in vitamin A metabolism, genetic factors, and immune dysregulation.3 Six types of PRP have been identified; they differ in the way they present and the populations affected (TABLE).1,4

PRP can be confused with other causes of erythroderma

PRP can cause erythroderma (also known as exfoliative dermatitis), which is the term applied to an erythematous eruption with scaling that covers ≥90% of the body’s surface area. Akhyani et al found that PRP is responsible for approximately 8% of all erythrodermas;5 the other causes of erythroderma are manifestations of numerous conditions, including psoriasis, dermatitis, drug eruptions, and malignancy. The course and prognosis of the erythroderma varies with the underlying condition causing it.6

Psoriasis is a common cause of exfoliative dermatitis in adults. Erythroderma may occur in patients with underlying psoriasis after discontinuing, or rapidly tapering, systemic corticosteroids.7 Because PRP is a papulosquamous eruption, it is often confused with psoriasis.1,3

Dermatitis. Several subtypes of dermatitis can be associated with erythroderma. These include atopic, seborrheic, allergic contact, airborne, and photosensitivity dermatitis.

Drug eruptions. Numerous pharmacologic agents have been associated with the development of widespread drug-induced skin eruptions. These eruptions include the severe reaction of toxic epidermal necrolysis, which always involves sloughing of skin.

Malignancy. Both cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (including mycosis fungoides) and internal malignancies can lead to erythroderma.6,8,9

PRP has several distinguishing features from other causes of erythroderma

Treatment includes oral retinoids

In the initial evaluation of most cases of erythroderma, it is important to perform a skin biopsy (a 4-mm punch is often best) with a request for a rush reading to avoid missing a possibly severe and life-threatening diagnosis. Skin biopsy is often not diagnostic, but may show alternating parakeratosis and orthokeratosis (as in this case). Careful correlation of the histopathologic findings with the clinical presentation is what usually leads to the diagnosis. Obtaining 2 punch biopsies may be helpful if there are multiple morphologies present or if mycosis fungoides is suspected. If the patient is not physiologically stable, hospitalization is warranted.

Oral retinoids (eg, acitretin) are the first-line treatment for PRP. PRP is a rare disease, so the best treatment data available include studies involving small case series. Other treatments include methotrexate and phototherapy, but results are mixed and patient-dependent.1,3 In fact, some patients have experienced flare-ups when treated with phototherapy; therefore, it is not a commonly used treatment for PRP.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibitors, including infliximab, adalimumab, and etanercept, have been used increasingly with varying degrees of success.10-12 TNF-alpha inhibitors have a relatively good safety profile and should be considered in refractory cases. If there are associated conditions, such as HIV, treating these may also result in remission.2

Our patient was treated with oral acitretin 70 mg/d. At a 3-month follow-up visit, her skin showed signs of partial improvement.

CORRESPONDENCE

André D. Généreux, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Abbott-Northwestern Hospital, 800 East 28th Street, Minneapolis, MN 55407-3799; andre.genereux@allina.com.

1. Klein A, Landthaler M, Karrer S. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a review of diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:157-170.

2. González-López A, Velasco E, Pozo T, et al. HIV-associated pityriasis rubra pilaris responsive to triple antiretroviral therapy. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:931-934.

3. Bruch-Gerharz D, Ruzicka T. Chapter 24. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY:McGraw-Hill;2012.

4. Sehgal VN, Srivastava G. (Juvenile) Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:438-446.

5. Akhyani M, Ghodsi ZS, Toosi S, et al. Erythroderma: a clinical study of 97 cases. BMC Dermatol. 2005;5:5.

6. Sehgal VN, Srivastava G, Sardana K. Erythroderma/exfoliative dermatitis: a synopsis. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:39-47.

7. Rosenbach M, Hsu S, Korman NJ, et al; National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board. Treatment of erythrodermic psoriasis: from the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:655-662.

8. Chong VH, Lim CC. Erythroderma as the first manifestation of colon cancer. South Med J. 2009;102:334-335.

9. Ge W, Teng BW, Yu DC, et al. Dermatosis as the initial presentation of gastric cancer: two cases. Chin J Cancer Res. 2014;26:632-638.

10. Garcovich S, Di Giampetruzzi AR, Antonelli G, et al. Treatment of refractory adult-onset pityriasis rubra pilaris with TNF-alpha antagonists: a case series. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:881-884.

11. Walling HW, Swick BL. Pityriasis rubra pilaris responding rapidly to adalimumab. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:99-101.

12. Eastham AB, Femia AN, Qureshi A, et al. Treatment options for pityriasis rubra pilaris including biologic agents: a retrospective analysis from an academic medical center. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:92-94.

A 48-year-old woman sought care for a widespread pruritic skin eruption that began on her upper back and spread to her arms, lower trunk, and lower legs. She’d had the rash for approximately 2 months and didn’t have any systemic symptoms. A course of prednisone prior to her presentation failed to improve the rash. She denied a personal or family history of rheumatologic or dermatologic disease and reported no new medications or exposures.

On physical exam, she was afebrile and her vital signs were normal. The rash had red-to-salmon–colored scaling patches with discrete and coalescing follicular papules. There were prominent islands of sparing (FIGURE 1).

The patient’s palms were waxy and erythematous and her feet had hyperkeratosis. A complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and lipid panel were normal. A skin biopsy demonstrated psoriasiform dermatitis with alternating areas of orthokeratosis and parakeratosis (the presence of keratinocyte nuclei within the stratum corneum where nuclei typically aren’t found).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pityriasis rubra pilaris