User login

Acute gout: Oral steroids work as well as NSAIDs

Use a short course of oral steroids (prednisone 30-40 mg/d for 5 days) for treatment of acute gout when nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are contraindicated. Steroids are also a reasonable choice as first-line treatment.1,2

Strength of recommendation

B: 2 good-quality, randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

Janssens HJ, Janssen M, van de Lisdonk EH, van Riel PL, van Weel C. Use of oral prednisolone or naproxen for the treatment of gout arthritis: a double-blind, randomized equivalence trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1854-1860.

Man CY, Cheung IT, Cameron PA, Rainer TH. Comparison of oral prednisolone/paracetamol and oral indomethacin/paracetamol combination therapy in the treatment of acute goutlike arthritis: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:670-677.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 68-year-old man with a history of ulcer disease and mild renal insufficiency comes to your office complaining of severe pain in his right foot. You note swelling and redness around the base of the big toe and diagnose acute gout. Wishing to avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and colchicine because of the patient’s medical history, you wonder what you can safely prescribe for pain relief.

NSAIDs have become the mainstay of treatment for acute gout,3,4 replacing colchicine—widely used for gout pain relief since the early 19th century.5 Colchicine fell out of favor because it routinely causes diarrhea and requires caution in patients with renal insufficiency.6 Now, however, there is growing concern about the adverse effects of NSAIDs.

Comorbidities, age, mean fewer options

NSAIDs increase the risk of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, especially in the first week of use.7 Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors, considered as effective as NSAIDs in treating acute gout pain,8 are also associated with GI bleeds.9 In addition, NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors increase cardiovascular risks, prompting the American Heart Association to recommend restricted use of both.10 NSAIDs’ effect on renal function, fluid retention, and interactions with anticoagulants are additional concerns, because gout patients are generally older and often have comorbid renal and cardiovascular diseases.3,11-13

In the United States, nearly 70% of patients who develop acute gout seek treatment from primary care physicians.12 Family physicians need a safe alternative to NSAIDs to relieve the severe pain associated with this condition. Will oral corticosteroids fit the bill?

STUDY SUMMARIES: Oral steroids: A safe and effective alternative

Janssens et al1 conducted a double-blind, randomized equivalence trial of 118 patients to compare the efficacy of prednisolone and naproxen for the treatment of monoarticular gout, confirmed by crystal analysis of synovial fluid. The study was conducted in the eastern Netherlands at a trial center patients were referred to by their family physicians. Those with major comorbidities, including a history of GI bleed or peptic ulcer, were excluded.

Participants were randomized to receive either prednisolone 35 mg* or naproxen 500 mg twice a day, with look-alike placebo tablets of the alternate drug, for 5 days. Pain, the primary outcome, was scored on a validated visual analog scale from 0 mm (no pain) to 100 mm (worst pain experienced).15 The reduction in the pain score at 90 hours was similar in both groups. Only a few minor side effects were reported in both groups, and all completely resolved in 3 weeks.

The study by Man et al2 was a randomized trial that compared indomethacin with oral prednisolone in 90 patients presenting to an emergency department in Hong Kong. Diagnosis of gout was made by clinical impression. Participants in the indomethacin group also received an intramuscular (IM) injection of diclofenac 75 mg, and those in both groups were monitored for acetaminophen use as a secondary endpoint.

Pain reduction, the primary endpoint, was assessed with a 10-point visual analog score, and was slightly better statistically in the oral steroid group. The study was not designed to evaluate for safety, but the authors noted that patients in the indomethacin group experienced more adverse effects (number needed to harm [NNH] for any adverse event: 3; NNH for serious events: 6).

Short-term steroids have few side effects

In both studies, patients receiving oral steroids experienced no significant side effects. This finding is consistent with other studies that have investigated short-term oral steroid use in the treatment of both rheumatoid arthritis and asthma.16,17

WHAT’S NEW?: Evidence supports use of steroids for acute gout

In the United States, prednisone is prescribed as treatment for acute gout only about 9% of the time.12 These 2 studies—the first randomized trials comparing oral steroids with NSAIDs, the usual gout treatment—may lead to greater use of steroids for this painful condition.

Both studies were well designed and conducted in an outpatient (or emergency) setting. Both showed that a short course of oral steroids is as effective as NSAIDs, and without significant side effects.

Previous studies have compared IM steroids with NSAIDs, and IM steroids with IM adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).18,19 However, these studies were not blinded—just one of their methodological problems.4

CAVEATS: Joint aspiration is not the norm

In the Janssens study, participants were diagnosed with gout after monosodium urate crystals were found in joint aspirate.1 This may not be the usual practice in primary care settings, where a clinical diagnosis of gout is typically made. The authors indicate that the failure to perform joint aspiration will lead to occasional cases of septic arthritis being treated with oral steroids. We recommend joint aspiration or a referral for such a procedure when clinical evidence (eg, fever and leukocytosis) is suggestive of septic arthritis.

Possible impact of acetaminophen

In the study by Man et al, acetaminophen was used by both groups as an adjunct for pain relief, and the amount used was higher (mean 10.3 g vs 6.4 g over 14 days) in the oral steroid group. It is possible that some of the pain relief experienced by those in the steroid group may have been from acetaminophen; however, a difference of 4 g over a 14-day period makes that unlikely. Even if additional acetaminophen is required, the advantages of oral steroids rather than NSAIDs or colchicine for patients with contraindications remain.

Also of note: These trials examined short-term treatment of acute gout. These findings cannot be extrapolated to the treatment of intercurrent gout or chronic gouty arthritis, since long-term steroid use has severe adverse effects.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: No significant barriers

We found little to prevent physicians from adopting this practice changer. Oral steroids are readily available and inexpensive, and most primary care clinicians regularly prescribe them for other conditions. This practice change recommendation should be readily implemented.

This study was selected and evaluated using FPIN’s Priority Updates from the Research Literature (PURL) Surveillance System methodology. The criteria and findings leading to the selection of this study as a PURL can be accessed at www.jfponline.com/purls.

* Prednisone is the precursor of prednisolone and is activated in the liver. The activity of both drugs is comparable, and prednisone and prednisolone can be converted milligram to milligram. However, prednisolone may be preferred for patients with severe liver disease.14 (In the United States, prednisolone is available as a liquid and prednisone as a tablet.)

PURL METHODOLOGY

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Janssens HJ, Janssen M, van de Lisdonk EH, van Riel PL, van Weel C. Use of oral prednisolone or naproxen for the treatment of gout arthritis: a double-blind, randomised equivalence trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1854-1860.

2. Man CY, Cheung IT, Cameron PA, Rainer TH. Comparison of oral prednisolone/paracetamol and oral indomethacin/paracetamol combination therapy in the treatment of acute goutlike arthritis: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:670-677.

3. Sutaria S, Katbamna R, Underwood M. Effectiveness of interventions for the treatment of acute and prevention of recurrent gout—a systematic review. Rheumatology. 2006;45:1422-1431.

4. Janssens HJ, Lucassen PL, Van de Laar FA, Janssen M, Van de Lisdonk EH. Systemic corticosteroids for acute gout. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD005521.-

5. Weinberger A, Pinkhas J. The history of colchicine. Korot. 1980;7:760-763.

6. Ahern MJ, Reid C, Gordon TP, McCredie M, Brooks PM, Jones M. Does colchicine work? The results of the first controlled study in acute gout. ANZ J Med. 1987;17:301-304.

7. Lewis SC, Langman MJ, Laporte JR, Matthews JN, Rawlins MD, Wiholm BE. Dose-response relationships between individual nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NANSAIDs) and serious upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis based on individual patient data. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54:320-326.

8. Rubin BR, Burton R, Navarra S, et al. Efficacy and safety profile of treatment with etoricoxib 120 mg once daily compared with indomethacin 50 mg three times daily in acute gout: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:598-606.

9. Laporte JR, Ibanez L, Vidal X, Vendrell L, Leone R. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding associated with the use of NSAIDs: newer versus older agents. Drug Saf. 2004;27:411-420.

10. Antman EM, Bennett JS, Daugherty A, et al. Use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: an update for clinicians: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007;115:1634-1642.

11. Petersel D, Schlesinger N. Treatment of acute gout in hospitalized patients. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1566-1568.

12. Krishnan E, Lienesch D, Kwoh CK. Gout in ambulatory care settings in the United States. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:498-501.

13. Krishnan E, Svendsen K, Neaton JD, Grandits G, Kuller LH. MRFIT Research Group. Long-term cardiovascular mortality among middle-aged men with gout. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1104-1110.

14. Davis M, Williams R, Chakraborty J, et al. Prednisone or prednisolone for the treatment of chronic active hepatitis? A comparison of plasma availability. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1978;5:501-505.

15. Todd KH. Pain assessment instruments for use in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23:285-295.

16. Gotzsche PC, Johansen HK. Short-term low-dose corticosteroids vs placebo and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD000189.-

17. Rowe BH, Spooner C, Ducharme FM, Bretzlaff JA, Bota GW. Early emergency department treatment of acute asthma with systemic corticosteroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(1):CD002308.-

18. Alloway JA, Moriarty MJ, Hoogland YT, Nashel DJ. Comparison of triamcinolone acetonide with indomethacin in the treatment of acute gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:111-113.

19. Siegel LB, Alloway JA, Nashel DJ. Comparison of adrenocorticotropic hormone and triamcinolone acetonide in the treatment of acute gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:1325-1327.

Use a short course of oral steroids (prednisone 30-40 mg/d for 5 days) for treatment of acute gout when nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are contraindicated. Steroids are also a reasonable choice as first-line treatment.1,2

Strength of recommendation

B: 2 good-quality, randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

Janssens HJ, Janssen M, van de Lisdonk EH, van Riel PL, van Weel C. Use of oral prednisolone or naproxen for the treatment of gout arthritis: a double-blind, randomized equivalence trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1854-1860.

Man CY, Cheung IT, Cameron PA, Rainer TH. Comparison of oral prednisolone/paracetamol and oral indomethacin/paracetamol combination therapy in the treatment of acute goutlike arthritis: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:670-677.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 68-year-old man with a history of ulcer disease and mild renal insufficiency comes to your office complaining of severe pain in his right foot. You note swelling and redness around the base of the big toe and diagnose acute gout. Wishing to avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and colchicine because of the patient’s medical history, you wonder what you can safely prescribe for pain relief.

NSAIDs have become the mainstay of treatment for acute gout,3,4 replacing colchicine—widely used for gout pain relief since the early 19th century.5 Colchicine fell out of favor because it routinely causes diarrhea and requires caution in patients with renal insufficiency.6 Now, however, there is growing concern about the adverse effects of NSAIDs.

Comorbidities, age, mean fewer options

NSAIDs increase the risk of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, especially in the first week of use.7 Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors, considered as effective as NSAIDs in treating acute gout pain,8 are also associated with GI bleeds.9 In addition, NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors increase cardiovascular risks, prompting the American Heart Association to recommend restricted use of both.10 NSAIDs’ effect on renal function, fluid retention, and interactions with anticoagulants are additional concerns, because gout patients are generally older and often have comorbid renal and cardiovascular diseases.3,11-13

In the United States, nearly 70% of patients who develop acute gout seek treatment from primary care physicians.12 Family physicians need a safe alternative to NSAIDs to relieve the severe pain associated with this condition. Will oral corticosteroids fit the bill?

STUDY SUMMARIES: Oral steroids: A safe and effective alternative

Janssens et al1 conducted a double-blind, randomized equivalence trial of 118 patients to compare the efficacy of prednisolone and naproxen for the treatment of monoarticular gout, confirmed by crystal analysis of synovial fluid. The study was conducted in the eastern Netherlands at a trial center patients were referred to by their family physicians. Those with major comorbidities, including a history of GI bleed or peptic ulcer, were excluded.

Participants were randomized to receive either prednisolone 35 mg* or naproxen 500 mg twice a day, with look-alike placebo tablets of the alternate drug, for 5 days. Pain, the primary outcome, was scored on a validated visual analog scale from 0 mm (no pain) to 100 mm (worst pain experienced).15 The reduction in the pain score at 90 hours was similar in both groups. Only a few minor side effects were reported in both groups, and all completely resolved in 3 weeks.

The study by Man et al2 was a randomized trial that compared indomethacin with oral prednisolone in 90 patients presenting to an emergency department in Hong Kong. Diagnosis of gout was made by clinical impression. Participants in the indomethacin group also received an intramuscular (IM) injection of diclofenac 75 mg, and those in both groups were monitored for acetaminophen use as a secondary endpoint.

Pain reduction, the primary endpoint, was assessed with a 10-point visual analog score, and was slightly better statistically in the oral steroid group. The study was not designed to evaluate for safety, but the authors noted that patients in the indomethacin group experienced more adverse effects (number needed to harm [NNH] for any adverse event: 3; NNH for serious events: 6).

Short-term steroids have few side effects

In both studies, patients receiving oral steroids experienced no significant side effects. This finding is consistent with other studies that have investigated short-term oral steroid use in the treatment of both rheumatoid arthritis and asthma.16,17

WHAT’S NEW?: Evidence supports use of steroids for acute gout

In the United States, prednisone is prescribed as treatment for acute gout only about 9% of the time.12 These 2 studies—the first randomized trials comparing oral steroids with NSAIDs, the usual gout treatment—may lead to greater use of steroids for this painful condition.

Both studies were well designed and conducted in an outpatient (or emergency) setting. Both showed that a short course of oral steroids is as effective as NSAIDs, and without significant side effects.

Previous studies have compared IM steroids with NSAIDs, and IM steroids with IM adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).18,19 However, these studies were not blinded—just one of their methodological problems.4

CAVEATS: Joint aspiration is not the norm

In the Janssens study, participants were diagnosed with gout after monosodium urate crystals were found in joint aspirate.1 This may not be the usual practice in primary care settings, where a clinical diagnosis of gout is typically made. The authors indicate that the failure to perform joint aspiration will lead to occasional cases of septic arthritis being treated with oral steroids. We recommend joint aspiration or a referral for such a procedure when clinical evidence (eg, fever and leukocytosis) is suggestive of septic arthritis.

Possible impact of acetaminophen

In the study by Man et al, acetaminophen was used by both groups as an adjunct for pain relief, and the amount used was higher (mean 10.3 g vs 6.4 g over 14 days) in the oral steroid group. It is possible that some of the pain relief experienced by those in the steroid group may have been from acetaminophen; however, a difference of 4 g over a 14-day period makes that unlikely. Even if additional acetaminophen is required, the advantages of oral steroids rather than NSAIDs or colchicine for patients with contraindications remain.

Also of note: These trials examined short-term treatment of acute gout. These findings cannot be extrapolated to the treatment of intercurrent gout or chronic gouty arthritis, since long-term steroid use has severe adverse effects.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: No significant barriers

We found little to prevent physicians from adopting this practice changer. Oral steroids are readily available and inexpensive, and most primary care clinicians regularly prescribe them for other conditions. This practice change recommendation should be readily implemented.

This study was selected and evaluated using FPIN’s Priority Updates from the Research Literature (PURL) Surveillance System methodology. The criteria and findings leading to the selection of this study as a PURL can be accessed at www.jfponline.com/purls.

* Prednisone is the precursor of prednisolone and is activated in the liver. The activity of both drugs is comparable, and prednisone and prednisolone can be converted milligram to milligram. However, prednisolone may be preferred for patients with severe liver disease.14 (In the United States, prednisolone is available as a liquid and prednisone as a tablet.)

PURL METHODOLOGY

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Use a short course of oral steroids (prednisone 30-40 mg/d for 5 days) for treatment of acute gout when nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are contraindicated. Steroids are also a reasonable choice as first-line treatment.1,2

Strength of recommendation

B: 2 good-quality, randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

Janssens HJ, Janssen M, van de Lisdonk EH, van Riel PL, van Weel C. Use of oral prednisolone or naproxen for the treatment of gout arthritis: a double-blind, randomized equivalence trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1854-1860.

Man CY, Cheung IT, Cameron PA, Rainer TH. Comparison of oral prednisolone/paracetamol and oral indomethacin/paracetamol combination therapy in the treatment of acute goutlike arthritis: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:670-677.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 68-year-old man with a history of ulcer disease and mild renal insufficiency comes to your office complaining of severe pain in his right foot. You note swelling and redness around the base of the big toe and diagnose acute gout. Wishing to avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and colchicine because of the patient’s medical history, you wonder what you can safely prescribe for pain relief.

NSAIDs have become the mainstay of treatment for acute gout,3,4 replacing colchicine—widely used for gout pain relief since the early 19th century.5 Colchicine fell out of favor because it routinely causes diarrhea and requires caution in patients with renal insufficiency.6 Now, however, there is growing concern about the adverse effects of NSAIDs.

Comorbidities, age, mean fewer options

NSAIDs increase the risk of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, especially in the first week of use.7 Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors, considered as effective as NSAIDs in treating acute gout pain,8 are also associated with GI bleeds.9 In addition, NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors increase cardiovascular risks, prompting the American Heart Association to recommend restricted use of both.10 NSAIDs’ effect on renal function, fluid retention, and interactions with anticoagulants are additional concerns, because gout patients are generally older and often have comorbid renal and cardiovascular diseases.3,11-13

In the United States, nearly 70% of patients who develop acute gout seek treatment from primary care physicians.12 Family physicians need a safe alternative to NSAIDs to relieve the severe pain associated with this condition. Will oral corticosteroids fit the bill?

STUDY SUMMARIES: Oral steroids: A safe and effective alternative

Janssens et al1 conducted a double-blind, randomized equivalence trial of 118 patients to compare the efficacy of prednisolone and naproxen for the treatment of monoarticular gout, confirmed by crystal analysis of synovial fluid. The study was conducted in the eastern Netherlands at a trial center patients were referred to by their family physicians. Those with major comorbidities, including a history of GI bleed or peptic ulcer, were excluded.

Participants were randomized to receive either prednisolone 35 mg* or naproxen 500 mg twice a day, with look-alike placebo tablets of the alternate drug, for 5 days. Pain, the primary outcome, was scored on a validated visual analog scale from 0 mm (no pain) to 100 mm (worst pain experienced).15 The reduction in the pain score at 90 hours was similar in both groups. Only a few minor side effects were reported in both groups, and all completely resolved in 3 weeks.

The study by Man et al2 was a randomized trial that compared indomethacin with oral prednisolone in 90 patients presenting to an emergency department in Hong Kong. Diagnosis of gout was made by clinical impression. Participants in the indomethacin group also received an intramuscular (IM) injection of diclofenac 75 mg, and those in both groups were monitored for acetaminophen use as a secondary endpoint.

Pain reduction, the primary endpoint, was assessed with a 10-point visual analog score, and was slightly better statistically in the oral steroid group. The study was not designed to evaluate for safety, but the authors noted that patients in the indomethacin group experienced more adverse effects (number needed to harm [NNH] for any adverse event: 3; NNH for serious events: 6).

Short-term steroids have few side effects

In both studies, patients receiving oral steroids experienced no significant side effects. This finding is consistent with other studies that have investigated short-term oral steroid use in the treatment of both rheumatoid arthritis and asthma.16,17

WHAT’S NEW?: Evidence supports use of steroids for acute gout

In the United States, prednisone is prescribed as treatment for acute gout only about 9% of the time.12 These 2 studies—the first randomized trials comparing oral steroids with NSAIDs, the usual gout treatment—may lead to greater use of steroids for this painful condition.

Both studies were well designed and conducted in an outpatient (or emergency) setting. Both showed that a short course of oral steroids is as effective as NSAIDs, and without significant side effects.

Previous studies have compared IM steroids with NSAIDs, and IM steroids with IM adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).18,19 However, these studies were not blinded—just one of their methodological problems.4

CAVEATS: Joint aspiration is not the norm

In the Janssens study, participants were diagnosed with gout after monosodium urate crystals were found in joint aspirate.1 This may not be the usual practice in primary care settings, where a clinical diagnosis of gout is typically made. The authors indicate that the failure to perform joint aspiration will lead to occasional cases of septic arthritis being treated with oral steroids. We recommend joint aspiration or a referral for such a procedure when clinical evidence (eg, fever and leukocytosis) is suggestive of septic arthritis.

Possible impact of acetaminophen

In the study by Man et al, acetaminophen was used by both groups as an adjunct for pain relief, and the amount used was higher (mean 10.3 g vs 6.4 g over 14 days) in the oral steroid group. It is possible that some of the pain relief experienced by those in the steroid group may have been from acetaminophen; however, a difference of 4 g over a 14-day period makes that unlikely. Even if additional acetaminophen is required, the advantages of oral steroids rather than NSAIDs or colchicine for patients with contraindications remain.

Also of note: These trials examined short-term treatment of acute gout. These findings cannot be extrapolated to the treatment of intercurrent gout or chronic gouty arthritis, since long-term steroid use has severe adverse effects.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: No significant barriers

We found little to prevent physicians from adopting this practice changer. Oral steroids are readily available and inexpensive, and most primary care clinicians regularly prescribe them for other conditions. This practice change recommendation should be readily implemented.

This study was selected and evaluated using FPIN’s Priority Updates from the Research Literature (PURL) Surveillance System methodology. The criteria and findings leading to the selection of this study as a PURL can be accessed at www.jfponline.com/purls.

* Prednisone is the precursor of prednisolone and is activated in the liver. The activity of both drugs is comparable, and prednisone and prednisolone can be converted milligram to milligram. However, prednisolone may be preferred for patients with severe liver disease.14 (In the United States, prednisolone is available as a liquid and prednisone as a tablet.)

PURL METHODOLOGY

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Janssens HJ, Janssen M, van de Lisdonk EH, van Riel PL, van Weel C. Use of oral prednisolone or naproxen for the treatment of gout arthritis: a double-blind, randomised equivalence trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1854-1860.

2. Man CY, Cheung IT, Cameron PA, Rainer TH. Comparison of oral prednisolone/paracetamol and oral indomethacin/paracetamol combination therapy in the treatment of acute goutlike arthritis: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:670-677.

3. Sutaria S, Katbamna R, Underwood M. Effectiveness of interventions for the treatment of acute and prevention of recurrent gout—a systematic review. Rheumatology. 2006;45:1422-1431.

4. Janssens HJ, Lucassen PL, Van de Laar FA, Janssen M, Van de Lisdonk EH. Systemic corticosteroids for acute gout. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD005521.-

5. Weinberger A, Pinkhas J. The history of colchicine. Korot. 1980;7:760-763.

6. Ahern MJ, Reid C, Gordon TP, McCredie M, Brooks PM, Jones M. Does colchicine work? The results of the first controlled study in acute gout. ANZ J Med. 1987;17:301-304.

7. Lewis SC, Langman MJ, Laporte JR, Matthews JN, Rawlins MD, Wiholm BE. Dose-response relationships between individual nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NANSAIDs) and serious upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis based on individual patient data. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54:320-326.

8. Rubin BR, Burton R, Navarra S, et al. Efficacy and safety profile of treatment with etoricoxib 120 mg once daily compared with indomethacin 50 mg three times daily in acute gout: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:598-606.

9. Laporte JR, Ibanez L, Vidal X, Vendrell L, Leone R. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding associated with the use of NSAIDs: newer versus older agents. Drug Saf. 2004;27:411-420.

10. Antman EM, Bennett JS, Daugherty A, et al. Use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: an update for clinicians: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007;115:1634-1642.

11. Petersel D, Schlesinger N. Treatment of acute gout in hospitalized patients. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1566-1568.

12. Krishnan E, Lienesch D, Kwoh CK. Gout in ambulatory care settings in the United States. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:498-501.

13. Krishnan E, Svendsen K, Neaton JD, Grandits G, Kuller LH. MRFIT Research Group. Long-term cardiovascular mortality among middle-aged men with gout. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1104-1110.

14. Davis M, Williams R, Chakraborty J, et al. Prednisone or prednisolone for the treatment of chronic active hepatitis? A comparison of plasma availability. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1978;5:501-505.

15. Todd KH. Pain assessment instruments for use in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23:285-295.

16. Gotzsche PC, Johansen HK. Short-term low-dose corticosteroids vs placebo and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD000189.-

17. Rowe BH, Spooner C, Ducharme FM, Bretzlaff JA, Bota GW. Early emergency department treatment of acute asthma with systemic corticosteroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(1):CD002308.-

18. Alloway JA, Moriarty MJ, Hoogland YT, Nashel DJ. Comparison of triamcinolone acetonide with indomethacin in the treatment of acute gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:111-113.

19. Siegel LB, Alloway JA, Nashel DJ. Comparison of adrenocorticotropic hormone and triamcinolone acetonide in the treatment of acute gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:1325-1327.

1. Janssens HJ, Janssen M, van de Lisdonk EH, van Riel PL, van Weel C. Use of oral prednisolone or naproxen for the treatment of gout arthritis: a double-blind, randomised equivalence trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1854-1860.

2. Man CY, Cheung IT, Cameron PA, Rainer TH. Comparison of oral prednisolone/paracetamol and oral indomethacin/paracetamol combination therapy in the treatment of acute goutlike arthritis: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:670-677.

3. Sutaria S, Katbamna R, Underwood M. Effectiveness of interventions for the treatment of acute and prevention of recurrent gout—a systematic review. Rheumatology. 2006;45:1422-1431.

4. Janssens HJ, Lucassen PL, Van de Laar FA, Janssen M, Van de Lisdonk EH. Systemic corticosteroids for acute gout. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD005521.-

5. Weinberger A, Pinkhas J. The history of colchicine. Korot. 1980;7:760-763.

6. Ahern MJ, Reid C, Gordon TP, McCredie M, Brooks PM, Jones M. Does colchicine work? The results of the first controlled study in acute gout. ANZ J Med. 1987;17:301-304.

7. Lewis SC, Langman MJ, Laporte JR, Matthews JN, Rawlins MD, Wiholm BE. Dose-response relationships between individual nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NANSAIDs) and serious upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis based on individual patient data. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54:320-326.

8. Rubin BR, Burton R, Navarra S, et al. Efficacy and safety profile of treatment with etoricoxib 120 mg once daily compared with indomethacin 50 mg three times daily in acute gout: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:598-606.

9. Laporte JR, Ibanez L, Vidal X, Vendrell L, Leone R. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding associated with the use of NSAIDs: newer versus older agents. Drug Saf. 2004;27:411-420.

10. Antman EM, Bennett JS, Daugherty A, et al. Use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: an update for clinicians: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007;115:1634-1642.

11. Petersel D, Schlesinger N. Treatment of acute gout in hospitalized patients. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1566-1568.

12. Krishnan E, Lienesch D, Kwoh CK. Gout in ambulatory care settings in the United States. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:498-501.

13. Krishnan E, Svendsen K, Neaton JD, Grandits G, Kuller LH. MRFIT Research Group. Long-term cardiovascular mortality among middle-aged men with gout. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1104-1110.

14. Davis M, Williams R, Chakraborty J, et al. Prednisone or prednisolone for the treatment of chronic active hepatitis? A comparison of plasma availability. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1978;5:501-505.

15. Todd KH. Pain assessment instruments for use in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23:285-295.

16. Gotzsche PC, Johansen HK. Short-term low-dose corticosteroids vs placebo and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD000189.-

17. Rowe BH, Spooner C, Ducharme FM, Bretzlaff JA, Bota GW. Early emergency department treatment of acute asthma with systemic corticosteroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(1):CD002308.-

18. Alloway JA, Moriarty MJ, Hoogland YT, Nashel DJ. Comparison of triamcinolone acetonide with indomethacin in the treatment of acute gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:111-113.

19. Siegel LB, Alloway JA, Nashel DJ. Comparison of adrenocorticotropic hormone and triamcinolone acetonide in the treatment of acute gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:1325-1327.

Copyright © 2008 The Family Physicians Inquiries Network.

All rights reserved.

Sequential therapy boosts H pylori eradication rates

Prescribe sequential therapy rather than the standard (concurrent) therapy to improve H pylori eradication rates, particularly in treatment-naïve patients.1

Strength of recommendation

B: Based on a well-done meta-analysis with disease-oriented outcomes

Jafri NS, Hornung CA, Howden CW. Meta-analysis: sequential therapy appears superior to standard therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in patients naive to treatment. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:923-931.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 40-year-old woman with a peptic ulcer has been diagnosed with Helicobacter pylori infection, and schedules a visit to discuss treatment. You’re aware of the declining eradication rates associated with standard therapy, and have heard that sequential therapy may be a more effective option. Should you offer it to this patient?

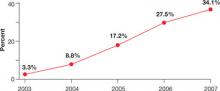

An estimated 30% to 40% of the US population is infected with H pylori,2 a bacterium that plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of peptic ulcer disease, chronic gastritis, and gastric cancer.1 The triple-drug regimen (a proton-pump inhibitor [PPI] and clarithromycin with amoxicillin, tinidazole, or another imidazole) is commonly used to treat H pylori in Europe and in the United States.3 Yet the eradication rate associated with this standard 3-drug regimen in this country is <80%, and appears to be on the decline. The likely problem: the increase in antibiotic-resistant strains of H pylori.2

Put amoxicillin first

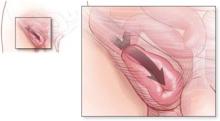

In Italy, eradication rates of >90% have been reported with a sequential therapy: a PPI and amoxicillin for 5 days, followed by the PPI, clarithromycin, and tinidazole for an additional 5 days (FIGURE).4 (Because tinidazole is a relatively new drug in the United States and physicians may use other drugs in its class instead, we refer to the drug class—imidazoles—rather than a specific medication in the FIGURE and much of the text that follows.) Using amoxicillin before the other antibiotics weakens bacterial cell walls, preventing the formation of drug efflux channels that can inhibit clarithromycin and other antibiotics, according to 1 theory.1 Thus, clarithromycin and an imidazole are more effective in the second phase of treatment.1

Should US physicians adopt the Italian protocol and prescribe tinidazole? Would metronidazole or other imidazoles be equally effective?

FIGURE

Sequential vs standard therapy: A comparison

STUDY SUMMARY: Sequential therapy is better on all counts

This meta-analysis found 9 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared H pylori eradication rates with standard 7- to 10-day triple-drug therapy to 10-day sequential therapy; an additional small study used a 5-day triple-drug comparison group. The authors performed a thorough search and used standard meta-analysis methods for data synthesis and analysis. The patients were all H pylori treatment naïve and had not used PPIs, histamine-2 receptor antagonists, or antibiotics in the month preceding the study. All patients (n=2747) had documented H pylori infection based on fecal antigen test, histologic evaluation, biopsy urease test, or urea breath test.

All the trials were conducted in Italy, although 2 of the studies included patients from the United States. Nine RCTs compared a triple-therapy regimen with PPI to sequential therapy, 1 RCT compared a triple-drug regimen with ranitidine to sequential therapy, and 1 included only pediatric patients. Pooled eradication rates were 93.4% (95% confidence interval [CI,] 91.3%-95.5%) for sequential therapy and 76.9% (CI, 71.0%-82.8%) for standard therapy, with a relative risk reduction of 71% (CI, 64%-77%).1 The authors estimated that for every 6.3 patients (95% CI, 5.2-7.1) treated with sequential therapy, there would be 1 additional cure compared to standard therapy. Standard 7- to 10-day triple therapy remained inferior to sequential therapy in all subgroup analyses, including patients with risk factors for eradication failure.

Adherence rates were similar in both groups. Sequential therapy resulted in a median adherence rate of 97.4% (range, 90.0%-98.9%), with standard therapy at 96.8% (range, 93.0%-100%).1 Reported side effects were also similar in both treatment groups.1

WHAT’S NEW?: This meta-analysis reduces doubt

The latest American College of Gastroenterology guidelines on the management of H pylori infection acknowledge that sequential therapy has shown promise in Europe, but the organization has not supported a change from the standard regimen to sequential therapy as first-line treatment. The standard triple-therapy regimen is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, and is the most commonly used H pylori treatment in the United States.1 This is the first meta-analysis based solely on RCTs, and it clearly demonstrates that sequential therapy increased eradication rates.

Helicobacter pylori (called H pylori for short) is a type of bacteria that can cause an ulcer (sore) to develop within the lining of your stomach and intestines. Ulcers can cause pain and bleeding, so it is important to get rid of this bacteria. To do this, you will need to take 4 different medicines over the next 10 days. They must be taken in a certain order, exactly as your doctor has prescribed.

One of the drugs you will be taking (for the entire 10-day period) is a proton pump inhibitor (called a PPI), a medicine that helps reduce the amount of acid in your stomach. ______________ is the name of the PPI your doctor has ordered. Take it twice a day, once in the morning and once in the evening, for 10 days.

You will also take 3 different kinds of antibiotics to eliminate the H pylori bacteria. For the first 5 days, you will take amoxicillin twice a day (2 pills in the morning and 2 in the evening), along with the PPI.

After 5 days, all the amoxicillin pills should be gone, and you will switch to 2 other antibiotics: clarithromycin AND ______________. For the next 5 days, you will take 1 PPI plus 1 clarithromycin and 1 ______________ every morning AND every night.

These medications may cause nausea, diarrhea, and a bad taste in your mouth. These side effects are usually not serious, but if they bother you so much that you cannot continue to take the medicine, it is important to call our office right away.

To remember to take each of the medicines in the morning AND evening on the correct day, use this chart to follow along. Put a check mark in the morning box or the evening box every time you take your medicine.

CAVEATS: Drug resistance, previous Tx could skew results

This meta-analysis only included studies performed in Italy, although 2 of the trials did include US recruits. Drug resistance patterns may be different in this country, which could alter sequential therapy’s eradication rates.

Because 3 antibiotics are used in sequential therapy, we may have fewer remaining options for patients who do not respond to this regimen, and we do not have information about patients with previous treatment failures. In addition, this meta-analysis only evaluated H pylori eradication rates in treatment-naïve patients, so we have no information about the effectiveness of this regimen in patients with previous treatment failures.

Would other sequential regimens—or drugs—work?

Patients who are allergic to amoxicillin would not be candidates for this sequential therapy protocol. While sequential therapy was compared with 7- to 10-day standard triple therapy, this study did not compare it with other regimens—eg, quadruple therapy or a 14-day course of standard triple-drug therapy.

Other drugs may also affect outcomes. The sequential therapy studies all used tinidazole, a relatively new agent in the United States; we don’t know whether metronidazole or other imidazoles are as effective.

The authors of this meta-analysis also noted the possibility of publication bias, but we doubt that there are enough unpublished data to invalidate the findings. Also, the selected RCTs only addressed eradication rates and not patient-oriented outcomes. However, most patient-oriented outcomes, including cancer and ulcers, can take years, even decades, to develop.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Sequential therapy may be confusing

While adherence rates were similar in the standard and sequential treatment groups in the meta-analysis, sequential therapy—which requires switching medications midway through treatment—might be more confusing for patients in actual practice. This has the potential to negatively affect adherence to the sequential regimen.

It will be important for physicians who prescribe sequential therapy to counsel patients on the importance of completing the treatment regimen exactly as prescribed and to provide clear instructions for doing so, ideally in the form of a patient handout like the one on page 653. Cost is not a problem; the price of sequential therapy is about equal to, or possibly less than, that of standard therapy.5

This study was selected and evaluated using FPIN’s Priority Updates from the Research Literature (PURL) Surveillance System methodology. The criteria and findings leading to the selection of this study as a PURL can be accessed at www.jfponline.com/purls.

1. Jafri NS, Hornung CA, Howden CW. Meta-analysis: sequential therapy appears superior to standard therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in patients naive to treatment. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:923-931.

2. Chey WD, Wong BC. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808-1825.

3. Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain C, et al. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut. 2007;56:772-781.

4. Zullo A, De FV, Hassan C, Morini S, Vaira D. The sequential therapy regimen for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a pooled-data analysis. Gut. 2007;56:1353-1357.

5. Vaira D, Zullo A, Vakil N, et al. Sequential therapy versus standard triple-drug therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:556-563.

PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Prescribe sequential therapy rather than the standard (concurrent) therapy to improve H pylori eradication rates, particularly in treatment-naïve patients.1

Strength of recommendation

B: Based on a well-done meta-analysis with disease-oriented outcomes

Jafri NS, Hornung CA, Howden CW. Meta-analysis: sequential therapy appears superior to standard therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in patients naive to treatment. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:923-931.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 40-year-old woman with a peptic ulcer has been diagnosed with Helicobacter pylori infection, and schedules a visit to discuss treatment. You’re aware of the declining eradication rates associated with standard therapy, and have heard that sequential therapy may be a more effective option. Should you offer it to this patient?

An estimated 30% to 40% of the US population is infected with H pylori,2 a bacterium that plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of peptic ulcer disease, chronic gastritis, and gastric cancer.1 The triple-drug regimen (a proton-pump inhibitor [PPI] and clarithromycin with amoxicillin, tinidazole, or another imidazole) is commonly used to treat H pylori in Europe and in the United States.3 Yet the eradication rate associated with this standard 3-drug regimen in this country is <80%, and appears to be on the decline. The likely problem: the increase in antibiotic-resistant strains of H pylori.2

Put amoxicillin first

In Italy, eradication rates of >90% have been reported with a sequential therapy: a PPI and amoxicillin for 5 days, followed by the PPI, clarithromycin, and tinidazole for an additional 5 days (FIGURE).4 (Because tinidazole is a relatively new drug in the United States and physicians may use other drugs in its class instead, we refer to the drug class—imidazoles—rather than a specific medication in the FIGURE and much of the text that follows.) Using amoxicillin before the other antibiotics weakens bacterial cell walls, preventing the formation of drug efflux channels that can inhibit clarithromycin and other antibiotics, according to 1 theory.1 Thus, clarithromycin and an imidazole are more effective in the second phase of treatment.1

Should US physicians adopt the Italian protocol and prescribe tinidazole? Would metronidazole or other imidazoles be equally effective?

FIGURE

Sequential vs standard therapy: A comparison

STUDY SUMMARY: Sequential therapy is better on all counts

This meta-analysis found 9 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared H pylori eradication rates with standard 7- to 10-day triple-drug therapy to 10-day sequential therapy; an additional small study used a 5-day triple-drug comparison group. The authors performed a thorough search and used standard meta-analysis methods for data synthesis and analysis. The patients were all H pylori treatment naïve and had not used PPIs, histamine-2 receptor antagonists, or antibiotics in the month preceding the study. All patients (n=2747) had documented H pylori infection based on fecal antigen test, histologic evaluation, biopsy urease test, or urea breath test.

All the trials were conducted in Italy, although 2 of the studies included patients from the United States. Nine RCTs compared a triple-therapy regimen with PPI to sequential therapy, 1 RCT compared a triple-drug regimen with ranitidine to sequential therapy, and 1 included only pediatric patients. Pooled eradication rates were 93.4% (95% confidence interval [CI,] 91.3%-95.5%) for sequential therapy and 76.9% (CI, 71.0%-82.8%) for standard therapy, with a relative risk reduction of 71% (CI, 64%-77%).1 The authors estimated that for every 6.3 patients (95% CI, 5.2-7.1) treated with sequential therapy, there would be 1 additional cure compared to standard therapy. Standard 7- to 10-day triple therapy remained inferior to sequential therapy in all subgroup analyses, including patients with risk factors for eradication failure.

Adherence rates were similar in both groups. Sequential therapy resulted in a median adherence rate of 97.4% (range, 90.0%-98.9%), with standard therapy at 96.8% (range, 93.0%-100%).1 Reported side effects were also similar in both treatment groups.1

WHAT’S NEW?: This meta-analysis reduces doubt

The latest American College of Gastroenterology guidelines on the management of H pylori infection acknowledge that sequential therapy has shown promise in Europe, but the organization has not supported a change from the standard regimen to sequential therapy as first-line treatment. The standard triple-therapy regimen is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, and is the most commonly used H pylori treatment in the United States.1 This is the first meta-analysis based solely on RCTs, and it clearly demonstrates that sequential therapy increased eradication rates.

Helicobacter pylori (called H pylori for short) is a type of bacteria that can cause an ulcer (sore) to develop within the lining of your stomach and intestines. Ulcers can cause pain and bleeding, so it is important to get rid of this bacteria. To do this, you will need to take 4 different medicines over the next 10 days. They must be taken in a certain order, exactly as your doctor has prescribed.

One of the drugs you will be taking (for the entire 10-day period) is a proton pump inhibitor (called a PPI), a medicine that helps reduce the amount of acid in your stomach. ______________ is the name of the PPI your doctor has ordered. Take it twice a day, once in the morning and once in the evening, for 10 days.

You will also take 3 different kinds of antibiotics to eliminate the H pylori bacteria. For the first 5 days, you will take amoxicillin twice a day (2 pills in the morning and 2 in the evening), along with the PPI.

After 5 days, all the amoxicillin pills should be gone, and you will switch to 2 other antibiotics: clarithromycin AND ______________. For the next 5 days, you will take 1 PPI plus 1 clarithromycin and 1 ______________ every morning AND every night.

These medications may cause nausea, diarrhea, and a bad taste in your mouth. These side effects are usually not serious, but if they bother you so much that you cannot continue to take the medicine, it is important to call our office right away.

To remember to take each of the medicines in the morning AND evening on the correct day, use this chart to follow along. Put a check mark in the morning box or the evening box every time you take your medicine.

CAVEATS: Drug resistance, previous Tx could skew results

This meta-analysis only included studies performed in Italy, although 2 of the trials did include US recruits. Drug resistance patterns may be different in this country, which could alter sequential therapy’s eradication rates.

Because 3 antibiotics are used in sequential therapy, we may have fewer remaining options for patients who do not respond to this regimen, and we do not have information about patients with previous treatment failures. In addition, this meta-analysis only evaluated H pylori eradication rates in treatment-naïve patients, so we have no information about the effectiveness of this regimen in patients with previous treatment failures.

Would other sequential regimens—or drugs—work?

Patients who are allergic to amoxicillin would not be candidates for this sequential therapy protocol. While sequential therapy was compared with 7- to 10-day standard triple therapy, this study did not compare it with other regimens—eg, quadruple therapy or a 14-day course of standard triple-drug therapy.

Other drugs may also affect outcomes. The sequential therapy studies all used tinidazole, a relatively new agent in the United States; we don’t know whether metronidazole or other imidazoles are as effective.

The authors of this meta-analysis also noted the possibility of publication bias, but we doubt that there are enough unpublished data to invalidate the findings. Also, the selected RCTs only addressed eradication rates and not patient-oriented outcomes. However, most patient-oriented outcomes, including cancer and ulcers, can take years, even decades, to develop.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Sequential therapy may be confusing

While adherence rates were similar in the standard and sequential treatment groups in the meta-analysis, sequential therapy—which requires switching medications midway through treatment—might be more confusing for patients in actual practice. This has the potential to negatively affect adherence to the sequential regimen.

It will be important for physicians who prescribe sequential therapy to counsel patients on the importance of completing the treatment regimen exactly as prescribed and to provide clear instructions for doing so, ideally in the form of a patient handout like the one on page 653. Cost is not a problem; the price of sequential therapy is about equal to, or possibly less than, that of standard therapy.5

This study was selected and evaluated using FPIN’s Priority Updates from the Research Literature (PURL) Surveillance System methodology. The criteria and findings leading to the selection of this study as a PURL can be accessed at www.jfponline.com/purls.

Prescribe sequential therapy rather than the standard (concurrent) therapy to improve H pylori eradication rates, particularly in treatment-naïve patients.1

Strength of recommendation

B: Based on a well-done meta-analysis with disease-oriented outcomes

Jafri NS, Hornung CA, Howden CW. Meta-analysis: sequential therapy appears superior to standard therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in patients naive to treatment. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:923-931.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 40-year-old woman with a peptic ulcer has been diagnosed with Helicobacter pylori infection, and schedules a visit to discuss treatment. You’re aware of the declining eradication rates associated with standard therapy, and have heard that sequential therapy may be a more effective option. Should you offer it to this patient?

An estimated 30% to 40% of the US population is infected with H pylori,2 a bacterium that plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of peptic ulcer disease, chronic gastritis, and gastric cancer.1 The triple-drug regimen (a proton-pump inhibitor [PPI] and clarithromycin with amoxicillin, tinidazole, or another imidazole) is commonly used to treat H pylori in Europe and in the United States.3 Yet the eradication rate associated with this standard 3-drug regimen in this country is <80%, and appears to be on the decline. The likely problem: the increase in antibiotic-resistant strains of H pylori.2

Put amoxicillin first

In Italy, eradication rates of >90% have been reported with a sequential therapy: a PPI and amoxicillin for 5 days, followed by the PPI, clarithromycin, and tinidazole for an additional 5 days (FIGURE).4 (Because tinidazole is a relatively new drug in the United States and physicians may use other drugs in its class instead, we refer to the drug class—imidazoles—rather than a specific medication in the FIGURE and much of the text that follows.) Using amoxicillin before the other antibiotics weakens bacterial cell walls, preventing the formation of drug efflux channels that can inhibit clarithromycin and other antibiotics, according to 1 theory.1 Thus, clarithromycin and an imidazole are more effective in the second phase of treatment.1

Should US physicians adopt the Italian protocol and prescribe tinidazole? Would metronidazole or other imidazoles be equally effective?

FIGURE

Sequential vs standard therapy: A comparison

STUDY SUMMARY: Sequential therapy is better on all counts

This meta-analysis found 9 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared H pylori eradication rates with standard 7- to 10-day triple-drug therapy to 10-day sequential therapy; an additional small study used a 5-day triple-drug comparison group. The authors performed a thorough search and used standard meta-analysis methods for data synthesis and analysis. The patients were all H pylori treatment naïve and had not used PPIs, histamine-2 receptor antagonists, or antibiotics in the month preceding the study. All patients (n=2747) had documented H pylori infection based on fecal antigen test, histologic evaluation, biopsy urease test, or urea breath test.

All the trials were conducted in Italy, although 2 of the studies included patients from the United States. Nine RCTs compared a triple-therapy regimen with PPI to sequential therapy, 1 RCT compared a triple-drug regimen with ranitidine to sequential therapy, and 1 included only pediatric patients. Pooled eradication rates were 93.4% (95% confidence interval [CI,] 91.3%-95.5%) for sequential therapy and 76.9% (CI, 71.0%-82.8%) for standard therapy, with a relative risk reduction of 71% (CI, 64%-77%).1 The authors estimated that for every 6.3 patients (95% CI, 5.2-7.1) treated with sequential therapy, there would be 1 additional cure compared to standard therapy. Standard 7- to 10-day triple therapy remained inferior to sequential therapy in all subgroup analyses, including patients with risk factors for eradication failure.

Adherence rates were similar in both groups. Sequential therapy resulted in a median adherence rate of 97.4% (range, 90.0%-98.9%), with standard therapy at 96.8% (range, 93.0%-100%).1 Reported side effects were also similar in both treatment groups.1

WHAT’S NEW?: This meta-analysis reduces doubt

The latest American College of Gastroenterology guidelines on the management of H pylori infection acknowledge that sequential therapy has shown promise in Europe, but the organization has not supported a change from the standard regimen to sequential therapy as first-line treatment. The standard triple-therapy regimen is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, and is the most commonly used H pylori treatment in the United States.1 This is the first meta-analysis based solely on RCTs, and it clearly demonstrates that sequential therapy increased eradication rates.

Helicobacter pylori (called H pylori for short) is a type of bacteria that can cause an ulcer (sore) to develop within the lining of your stomach and intestines. Ulcers can cause pain and bleeding, so it is important to get rid of this bacteria. To do this, you will need to take 4 different medicines over the next 10 days. They must be taken in a certain order, exactly as your doctor has prescribed.

One of the drugs you will be taking (for the entire 10-day period) is a proton pump inhibitor (called a PPI), a medicine that helps reduce the amount of acid in your stomach. ______________ is the name of the PPI your doctor has ordered. Take it twice a day, once in the morning and once in the evening, for 10 days.

You will also take 3 different kinds of antibiotics to eliminate the H pylori bacteria. For the first 5 days, you will take amoxicillin twice a day (2 pills in the morning and 2 in the evening), along with the PPI.

After 5 days, all the amoxicillin pills should be gone, and you will switch to 2 other antibiotics: clarithromycin AND ______________. For the next 5 days, you will take 1 PPI plus 1 clarithromycin and 1 ______________ every morning AND every night.

These medications may cause nausea, diarrhea, and a bad taste in your mouth. These side effects are usually not serious, but if they bother you so much that you cannot continue to take the medicine, it is important to call our office right away.

To remember to take each of the medicines in the morning AND evening on the correct day, use this chart to follow along. Put a check mark in the morning box or the evening box every time you take your medicine.

CAVEATS: Drug resistance, previous Tx could skew results

This meta-analysis only included studies performed in Italy, although 2 of the trials did include US recruits. Drug resistance patterns may be different in this country, which could alter sequential therapy’s eradication rates.

Because 3 antibiotics are used in sequential therapy, we may have fewer remaining options for patients who do not respond to this regimen, and we do not have information about patients with previous treatment failures. In addition, this meta-analysis only evaluated H pylori eradication rates in treatment-naïve patients, so we have no information about the effectiveness of this regimen in patients with previous treatment failures.

Would other sequential regimens—or drugs—work?

Patients who are allergic to amoxicillin would not be candidates for this sequential therapy protocol. While sequential therapy was compared with 7- to 10-day standard triple therapy, this study did not compare it with other regimens—eg, quadruple therapy or a 14-day course of standard triple-drug therapy.

Other drugs may also affect outcomes. The sequential therapy studies all used tinidazole, a relatively new agent in the United States; we don’t know whether metronidazole or other imidazoles are as effective.

The authors of this meta-analysis also noted the possibility of publication bias, but we doubt that there are enough unpublished data to invalidate the findings. Also, the selected RCTs only addressed eradication rates and not patient-oriented outcomes. However, most patient-oriented outcomes, including cancer and ulcers, can take years, even decades, to develop.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Sequential therapy may be confusing

While adherence rates were similar in the standard and sequential treatment groups in the meta-analysis, sequential therapy—which requires switching medications midway through treatment—might be more confusing for patients in actual practice. This has the potential to negatively affect adherence to the sequential regimen.

It will be important for physicians who prescribe sequential therapy to counsel patients on the importance of completing the treatment regimen exactly as prescribed and to provide clear instructions for doing so, ideally in the form of a patient handout like the one on page 653. Cost is not a problem; the price of sequential therapy is about equal to, or possibly less than, that of standard therapy.5

This study was selected and evaluated using FPIN’s Priority Updates from the Research Literature (PURL) Surveillance System methodology. The criteria and findings leading to the selection of this study as a PURL can be accessed at www.jfponline.com/purls.

1. Jafri NS, Hornung CA, Howden CW. Meta-analysis: sequential therapy appears superior to standard therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in patients naive to treatment. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:923-931.

2. Chey WD, Wong BC. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808-1825.

3. Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain C, et al. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut. 2007;56:772-781.

4. Zullo A, De FV, Hassan C, Morini S, Vaira D. The sequential therapy regimen for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a pooled-data analysis. Gut. 2007;56:1353-1357.

5. Vaira D, Zullo A, Vakil N, et al. Sequential therapy versus standard triple-drug therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:556-563.

PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Jafri NS, Hornung CA, Howden CW. Meta-analysis: sequential therapy appears superior to standard therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in patients naive to treatment. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:923-931.

2. Chey WD, Wong BC. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808-1825.

3. Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain C, et al. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut. 2007;56:772-781.

4. Zullo A, De FV, Hassan C, Morini S, Vaira D. The sequential therapy regimen for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a pooled-data analysis. Gut. 2007;56:1353-1357.

5. Vaira D, Zullo A, Vakil N, et al. Sequential therapy versus standard triple-drug therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:556-563.

PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2008 The Family Physicians Inquiries Network.

All rights reserved.

Can metformin undo weight gain induced by antipsychotics?

Lack of evidence for weight loss drugs

The most recent guideline on this topic does not recommend any medication, citing a lack of evidence. In its 2003 consensus statement, a panel representing the American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and the North American Association for the Study of Obesity3 recommends:

- That patients taking second-generation antipsychotics have the following assessments at baseline and regular intervals: weight, height, waist circumference, blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose, and fasting lipids.

- Providing nutrition and exercise counseling to all patients who are over-weight or obese at baseline.

- Initiating treatment with one of the second-generation antipsychotics with a lower risk of weight gain for patients at high risk of diabetes (ie, family history) and for patients who gain 5% or more of their initial weight or develop worsening hyperglycemia or dyslipidemia during treatment.

This guideline does not recommend metformin to reduce weight gain.

A 2007 Cochrane review of interventions to reduce weight gain in patients with schizophrenia included 23 randomized controlled trials of a variety of weight loss interventions, including cognitive/behavioral interventions and a variety of medications, including sibutramine, orlistat, fluoxetine, topiramate, and metformin. The authors highlighted the limited number of studies of short duration and with small sample sizes and concluded that the evidence was insufficient for the use of pharmacologic interventions to prevent or treat weight gain.5

STUDY SUMMARY: Lifestyle changes and metformin compared

This randomized controlled trial was conducted in China and included 128 adults aged 18 to 45 with a first psychotic episode of schizophrenia. All patients had to have gained more than 10% of their pretreatment body weight during the first year of treatment with an antipsychotic medication (clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, or sulpiride [not approved for use in the United States]). All study participants had to be under the care of an adult caregiver who monitored and recorded food intake, exercise, and medication intake. Patients with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, liver or renal dysfunction, substance abuse, or psychiatric diagnoses other than schizophrenia were excluded.

Patients were randomized to 1 of 4 groups for the 12 weeks of the study:

- Metformin alone, 250 mg 3 times daily

- Placebo alone

- Lifestyle intervention plus metformin

- Lifestyle intervention plus placebo

The lifestyle intervention included 3 components: (1) education: monthly programs on nutrition and physical activity; (2) diet: the American Heart Association step 2 diet (<30% calories from fat, 55% carbohydrates, >15% protein, with at least 15 g fiber per 1000 kcal); and (3) exercise: 1 week of sessions with an exercise physiologist followed by an individualized home-based exercise program.

Primary outcomes included changes in weight, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and fasting glucose ( TABLE 2 ). Ten of the 128 randomized patients either discontinued the study or were lost to follow up, but all 128 patients were included in the analysis.

TABLE 2

Mean difference between baseline and endpoint (week 12) of treatment outcomes (95% confidence intervals)1

| LIFESTYLE + METFORMIN | METFORMIN | LIFESTYLE | PLACEBO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight, kg | -4.7 (-5.7 to -3.4) | -3.2 (-3.9 to -2.5) | -1.4 (-2.0 to -0.7) | 3.1 (2.4 to 3.8) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | -1.8 (-2.3 to -1.3) | -1.2 (-1.5 to -0.9) | -0.5 (-0.8 to -0.3) | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.5) |

| Waist circumference, cm | -2.0 (-2.4 to -1.5) | -1.3 (-1.5 to -1.1) | 0.1 (-0.5 to 0.7) | 2.2 (1.7 to 2.8) |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | -7.2 (-10.8 to -5.4) | -10.8 (-16.2 to -7.2) | -7.2 (-9.0 to -3.6) | 1.8 (-1.8 to 3.6) |

Best result: Lifestyle changes plus metformin

Compared with baseline, weight decreased by 7.3% in the lifestyle plus metformin group, by 4.9% in the metformin-only group, and by 2.2% in the lifestyle-only group; in the placebo group, weight increased by 4.8%.

Participants in all 3 intervention groups also showed significant decreases in the mean fasting glucose, insulin levels, and insulin resistance index (IRI). The insulin levels and the IRI increased in the placebo group.

No significant differences in adverse effects were noted among the 4 treatment groups.1

WHAT’S NEW: Convincing evidence

This is the first randomized controlled trial to show convincingly that metformin alone or in combination with lifestyle changes is superior to lifestyle changes alone or placebo for reducing weight gain and other adverse metabolic outcomes induced by second-generation antipsychotics.

Intensive lifestyle interventions

Prior studies found that intensive lifestyle interventions can help reduce antipsychotic-related weight gain. A 3-month randomized controlled trial compared an early behavioral intervention (dietary counseling, an exercise program, and behavior therapy) with routine care in 61 patients with first-episode psychosis who were taking risperidone, olanzapine, or haloperidol;6 significantly fewer patients assigned to behavioral intervention had an increased initial body weight of more than 7%: 39% in the behavioral intervention group vs 79% in the routine care group (P<.002).

Small samples, small effect sizes

Past studies of metformin for antipsychotic-associated weight gain have generally shown a small benefit, though small sample sizes and small effect sizes prohibited definitive conclusions. Unlike the study by Wu and colleagues,1 none of these past studies were designed to compare the combination of metformin and lifestyle intervention with metformin alone, lifestyle intervention alone, or placebo alone.

Klein et al conducted a randomized placebo-controlled trial of metformin in 39 children ages 10 to 17 whose weight had increased more than 10% on atypical antipsychotic therapy.7 The children treated with placebo gained a mean of 4 kg and increased their mean BMI by 1.12 kg/m2 during 16 weeks of treatment, while those in the metformin group did not gain weight and decreased their mean BMI by 0.43 kg/m2.

Baptista et al randomized 40 in-patients with schizophrenia, who were being switched from conventional antipsychotics to olanzapine, to either metformin (850-1750 mg/d) or placebo. Both groups gained a similar amount of weight after the 14-week study (5.5 vs 6.3 kg, metformin vs placebo). Three patients who started with high fasting glucose had decreases while taking metformin, and 3 patients given placebo developed elevated fasting glucose during the study.8

In another randomized controlled trial of metformin vs placebo in 80 patients who had been taking olanzapine for at least 4 months, Baptista et al found only a small, insignificant difference in weight loss after 12 weeks of treatment (metformin group lost 1.4 kg, placebo group lost 0.18 kg, P=.09). They reported that both groups were highly motivated to lose weight and were compliant with the healthy lifestyle recommendations.9

An adequately powered study

The trial1 highlighted in this PURL had an adequate sample size to compare metformin plus a lifestyle intervention with either treatment alone or placebo. It showed a clinically important effect of metformin both by itself and in conjunction with the lifestyle intervention.

CAVEATS: Consider switching drugs

Before adding metformin to help with weight loss, primary care clinicians should contact the patient’s psychiatrist to discuss the option of switching antipsychotic medications. Switching from a medication with a higher risk for weight gain, such as olanzapine, to one with a lower risk, such as aripiprazole or ziprasidone, can lead to significant weight loss.10

Not an option for some

However, some patients, especially those taking clozapine, may have already tried multiple antipsychotic agents without success, and switching is not an option for them.

Prescribing metformin

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Adherence

These study participants were under the care of an adult caregiver who monitored and recorded food and medication intake and exercise level. The lifestyle intervention was thorough and structured and this kind of program is often not available to us for our patients. As a consequence, we may not obtain the same results as in this study. However, even the metformin-alone group showed improvements, and if our patients can reliably take their second-generation antipsychotic, they should also be able to take metformin reliably.

Patient resistance

Some patients may resist taking an additional medication to treat the side effects of their antipsychotic medication. Taking the time to educate them about the increased risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease related to weight gain may help convince them to do so. Warn them about possible gastrointestinal adverse effects of metformin, which tend to lessen or disappear with time.

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

PURLs methodology

This study was selected and evaluated using FPIN’s Priority Updates from the Research Literature (PURL) Surveillance System methodology. The criteria and findings leading to the selection of this study as a PURL can be accessed at www.jfponline.com/purls.

1. Wu R-R, Zhao J-P, Jin H, et al. Lifestyle intervention and metformin for treatment of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:185-193.

2. Rowland K, Schumann SA. Have pedometer, will travel. J Fam Pract. 2008;57:90-93.

3. American Diabetes Association; American Psychiatric Association; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; North American Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:596-601.

4. Newcomer JW. Metabolic considerations in the use of antipsychotic medications: a review of recent evidence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(suppl 1):20-27.

5. Faulkner G, Cohn T, Remington G. Interventions to reduce weight gain in schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD005148.-

6. Alvarez-Jiménez M, González-Blanch C, Vázquez-Barquero JL, et al. Attenuation of antipsychotic-induced weight gain with early behavioral intervention in drug-naïve first-episode psychosis patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1253-1260.

7. Klein DJ, Cottingham EM, Sorter M, Barton BA, Morrison JA. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of metformin treatment of weight gain associated with initiation of atypical antipsychotic therapy in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:2072-2079.

8. Baptista T, Martínez J, Lacruz A, et al. Metformin for prevention of weight gain and insulin resistance with olanzapine: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51:192-196.

9. Baptista T, Rangel N, Fernández V, et al. Metformin as an adjunctive treatment to control body weight and metabolic dysfunction during olanzapine administration: a multicentric, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Schizophrenia Res. 2007;93:99-108.

10. Weiden PJ. Switching antipsychotics as a treatment strategy for antipsychotic-induced weight gain and dyslipidemia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(suppl 4):34-39.

Lack of evidence for weight loss drugs