User login

The branching tree of hospital medicine

Diversity of training backgrounds

You’ve probably heard of a “nocturnist,” but have you ever heard of a “weekendist?”

The field of hospital medicine (HM) has evolved dramatically since the term “hospitalist” was introduced in the literature in 1996.1 There is a saying in HM that “if you know one HM program, you know one HM program,” alluding to the fact that every HM program is unique. The diversity of individual HM programs combined with the overall evolution of the field has expanded the range of jobs available in HM.

The nomenclature of adding an -ist to the end of the specific roles (e.g., nocturnist, weekendist) has become commonplace. These roles have developed with the increasing need for day and night staffing at many hospitals secondary to increased and more complex patients, less availability of residents because of work hour restrictions, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) rules that require overnight supervision of residents

Additionally, the field of HM increasingly includes physicians trained in internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, and medicine-pediatrics (med-peds). In this article, we describe the variety of roles available to trainees joining HM and the multitude of different training backgrounds hospitalists come from.

Nocturnists

The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report notes that 76.1% of adult-only HM groups have nocturnists, hospitalists who work primarily at night to admit and to provide coverage for admitted patients.2 Nocturnists often provide benefit to the rest of their hospitalist group by allowing fewer required night shifts for those that prefer to work during the day.

Nocturnists may choose a nighttime schedule for several reasons, including the ability to be home more during the day. They also have the potential to work fewer total hours or shifts while still earning a similar or increased income, compared with predominantly daytime hospitalists, increasing their flexibility to pursue other interests. These nocturnists become experts in navigating the admission process and responding to inpatient emergencies often with less support when compared with daytime hospitalists.

In addition to career nocturnist work, nocturnist jobs can be a great fit for those residency graduates who are undecided about fellowship and enjoy the acuity of inpatient medicine. It provides an opportunity to hone their clinical skill set prior to specialized training while earning an attending salary, and offers flexible hours which may allow for research or other endeavors. In academic centers, nocturnist educational roles take on a different character as well and may involve more 1:1 educational experiences. The role of nocturnists as educators is expanding as ACGME rules call for more oversight and educational opportunities for residents who are working at night.

However, challenges exist for nocturnists, including keeping abreast of new changes in their HM groups and hospital systems and engaging in quality initiatives, given that most meetings occur during the day. Additionally, nocturnists must adapt to sleeping during the day, potentially getting less sleep then they would otherwise and being “off cycle” with family and friends. For nocturnists raising children, being off cycle may be advantageous as it can allow them to be home with their children after school.

Weekendists

Another common hospitalist role is the weekendist, hospitalists who spend much of their clinical time preferentially working weekends. Similar to nocturnists, weekendists provide benefit to their hospitalist group by allowing others to have more weekends off.

Weekendists may prefer working weekends because of fewer total shifts or hours and/or higher compensation per shift. Additionally, weekendists have the flexibility to do other work on weekdays, such as research or another hospitalist job. For those that do nonclinical work during the week, a weekendist position may allow them to keep their clinical skills up to date. However, weekendists may face intense clinical days with a higher census because of fewer hospitalists rounding on the weekends.

Weekendists must balance having more potential time available during the weekdays but less time on the weekends to devote to family and friends. Furthermore, weekendists may feel less engaged with nonclinical opportunities, including quality improvement, educational offerings, and teaching opportunities.

SNFists

With increasing emphasis on transitions of care and the desire to avoid readmission penalties, some hospitalists have transitioned to work partly or primarily in skilled nursing facilities (SNF) and have been referred to as “SNFists.” Some of these hospitalists may split their clinical time between SNFs and acute care hospitals, while others may work exclusively at SNFs.

SNFists have the potential to be invaluable in improving transitions of care after discharge to post–acute care facilities because of increased provider presence in these facilities, comfort with medically complex patients, and appreciation of government regulations.4 SNFists may face potential challenges of needing to staff more than one post–acute care hospital and of having less resources available, compared with an acute care hospital.

Specific specialty hospitalists

For a variety of reasons including clinical interest, many hospitalists have become specialized with regards to their primary inpatient population. Some hospitalists spend the majority of their clinical time on a specific service in the hospital, often working closely with the subspecialist caring for that patient. These hospitalists may focus on hematology, oncology, bone-marrow transplant, neurology, cardiology, surgery services, or critical care, among others. Hospitalists focused on a specific service often become knowledge experts in that specialty. Conversely, by focusing on a specific service, certain pathologies may be less commonly seen, which may narrow the breadth of the hospital medicine job.

Hospitalist training

Internal medicine hospitalists may be the most common hospitalists encountered in many hospitals and at each Society of Hospital Medicine annual conference, but there has also been rapid growth in hospitalists from other specialties and backgrounds.

Family medicine hospitalists are a part of 64.9% of HM groups and about 9% of family medicine graduates are choosing HM as a career path.2,3 Most family medicine hospitalists work in adult HM groups, but some, particularly in rural or academic settings, care for pediatric, newborn, and/or maternity patients. Similarly, pediatric hospitalists have become entrenched at many hospitals where children are admitted. These pediatric hospitalists, like adult hospitalists, may work in a variety of different clinical roles including in EDs, newborn nurseries, and inpatient wards or ICUs; they may also provide consult, sedation, or procedural services.

Med-peds hospitalists that split time between internal medicine and pediatrics are becoming more commonplace in the field. Many work at academic centers where they often work on each side separately, doing the same work as their internal medicine or pediatrics colleagues, and then switching to the other side after a period of time. Some centers offer unique roles for med-peds hospitalists including working on adult consult teams in children’s hospitals, where they provide consult care to older patients that may still receive their care at a children’s hospital. There are also nonacademic hospitals that primarily staff med-peds hospitalists, where they can provide the full spectrum of care from the newborn nursery to the inpatient pediatric and adult wards.

Hospital medicine is a young field that is constantly changing with new and developing roles for hospitalists from a wide variety of backgrounds. Stick around to see which “-ist” will come next in HM.

Dr. Hall is a med-peds hospitalist and assistant professor at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Sanyal-Dey is an academic hospitalist at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center and the University of California, San Francisco, where she is the director of clinical operations, and director of the faculty inpatient service. Dr. Chang is associate professor and interprofessional education thread director (MD curriculum) at Washington University, St. Louis. Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System and associate professor at the University of California, San Diego. He is the chair of SHM’s Physicians in Training committee. Dr. Seymour is family medicine hospitalist education director at the University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, and associate professor at the University of Massachusetts.

References

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. The Emerging Role of “Hospitalists” in the American Health Care System. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(7):514-7.

2. 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report. Philadelphia: Society of Hospital Medicine, 2018.

3. Weaver SP, Hill J. Academician Attitudes and Beliefs Regarding the Use of Hospitalists: A CERA Study. Fam Med. 2015;47(5):357-61.

4. Teno JM et al. Temporal Trends in the Numbers of Skilled Nursing Facility Specialists From 2007 Through 2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1376-8.

Diversity of training backgrounds

Diversity of training backgrounds

You’ve probably heard of a “nocturnist,” but have you ever heard of a “weekendist?”

The field of hospital medicine (HM) has evolved dramatically since the term “hospitalist” was introduced in the literature in 1996.1 There is a saying in HM that “if you know one HM program, you know one HM program,” alluding to the fact that every HM program is unique. The diversity of individual HM programs combined with the overall evolution of the field has expanded the range of jobs available in HM.

The nomenclature of adding an -ist to the end of the specific roles (e.g., nocturnist, weekendist) has become commonplace. These roles have developed with the increasing need for day and night staffing at many hospitals secondary to increased and more complex patients, less availability of residents because of work hour restrictions, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) rules that require overnight supervision of residents

Additionally, the field of HM increasingly includes physicians trained in internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, and medicine-pediatrics (med-peds). In this article, we describe the variety of roles available to trainees joining HM and the multitude of different training backgrounds hospitalists come from.

Nocturnists

The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report notes that 76.1% of adult-only HM groups have nocturnists, hospitalists who work primarily at night to admit and to provide coverage for admitted patients.2 Nocturnists often provide benefit to the rest of their hospitalist group by allowing fewer required night shifts for those that prefer to work during the day.

Nocturnists may choose a nighttime schedule for several reasons, including the ability to be home more during the day. They also have the potential to work fewer total hours or shifts while still earning a similar or increased income, compared with predominantly daytime hospitalists, increasing their flexibility to pursue other interests. These nocturnists become experts in navigating the admission process and responding to inpatient emergencies often with less support when compared with daytime hospitalists.

In addition to career nocturnist work, nocturnist jobs can be a great fit for those residency graduates who are undecided about fellowship and enjoy the acuity of inpatient medicine. It provides an opportunity to hone their clinical skill set prior to specialized training while earning an attending salary, and offers flexible hours which may allow for research or other endeavors. In academic centers, nocturnist educational roles take on a different character as well and may involve more 1:1 educational experiences. The role of nocturnists as educators is expanding as ACGME rules call for more oversight and educational opportunities for residents who are working at night.

However, challenges exist for nocturnists, including keeping abreast of new changes in their HM groups and hospital systems and engaging in quality initiatives, given that most meetings occur during the day. Additionally, nocturnists must adapt to sleeping during the day, potentially getting less sleep then they would otherwise and being “off cycle” with family and friends. For nocturnists raising children, being off cycle may be advantageous as it can allow them to be home with their children after school.

Weekendists

Another common hospitalist role is the weekendist, hospitalists who spend much of their clinical time preferentially working weekends. Similar to nocturnists, weekendists provide benefit to their hospitalist group by allowing others to have more weekends off.

Weekendists may prefer working weekends because of fewer total shifts or hours and/or higher compensation per shift. Additionally, weekendists have the flexibility to do other work on weekdays, such as research or another hospitalist job. For those that do nonclinical work during the week, a weekendist position may allow them to keep their clinical skills up to date. However, weekendists may face intense clinical days with a higher census because of fewer hospitalists rounding on the weekends.

Weekendists must balance having more potential time available during the weekdays but less time on the weekends to devote to family and friends. Furthermore, weekendists may feel less engaged with nonclinical opportunities, including quality improvement, educational offerings, and teaching opportunities.

SNFists

With increasing emphasis on transitions of care and the desire to avoid readmission penalties, some hospitalists have transitioned to work partly or primarily in skilled nursing facilities (SNF) and have been referred to as “SNFists.” Some of these hospitalists may split their clinical time between SNFs and acute care hospitals, while others may work exclusively at SNFs.

SNFists have the potential to be invaluable in improving transitions of care after discharge to post–acute care facilities because of increased provider presence in these facilities, comfort with medically complex patients, and appreciation of government regulations.4 SNFists may face potential challenges of needing to staff more than one post–acute care hospital and of having less resources available, compared with an acute care hospital.

Specific specialty hospitalists

For a variety of reasons including clinical interest, many hospitalists have become specialized with regards to their primary inpatient population. Some hospitalists spend the majority of their clinical time on a specific service in the hospital, often working closely with the subspecialist caring for that patient. These hospitalists may focus on hematology, oncology, bone-marrow transplant, neurology, cardiology, surgery services, or critical care, among others. Hospitalists focused on a specific service often become knowledge experts in that specialty. Conversely, by focusing on a specific service, certain pathologies may be less commonly seen, which may narrow the breadth of the hospital medicine job.

Hospitalist training

Internal medicine hospitalists may be the most common hospitalists encountered in many hospitals and at each Society of Hospital Medicine annual conference, but there has also been rapid growth in hospitalists from other specialties and backgrounds.

Family medicine hospitalists are a part of 64.9% of HM groups and about 9% of family medicine graduates are choosing HM as a career path.2,3 Most family medicine hospitalists work in adult HM groups, but some, particularly in rural or academic settings, care for pediatric, newborn, and/or maternity patients. Similarly, pediatric hospitalists have become entrenched at many hospitals where children are admitted. These pediatric hospitalists, like adult hospitalists, may work in a variety of different clinical roles including in EDs, newborn nurseries, and inpatient wards or ICUs; they may also provide consult, sedation, or procedural services.

Med-peds hospitalists that split time between internal medicine and pediatrics are becoming more commonplace in the field. Many work at academic centers where they often work on each side separately, doing the same work as their internal medicine or pediatrics colleagues, and then switching to the other side after a period of time. Some centers offer unique roles for med-peds hospitalists including working on adult consult teams in children’s hospitals, where they provide consult care to older patients that may still receive their care at a children’s hospital. There are also nonacademic hospitals that primarily staff med-peds hospitalists, where they can provide the full spectrum of care from the newborn nursery to the inpatient pediatric and adult wards.

Hospital medicine is a young field that is constantly changing with new and developing roles for hospitalists from a wide variety of backgrounds. Stick around to see which “-ist” will come next in HM.

Dr. Hall is a med-peds hospitalist and assistant professor at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Sanyal-Dey is an academic hospitalist at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center and the University of California, San Francisco, where she is the director of clinical operations, and director of the faculty inpatient service. Dr. Chang is associate professor and interprofessional education thread director (MD curriculum) at Washington University, St. Louis. Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System and associate professor at the University of California, San Diego. He is the chair of SHM’s Physicians in Training committee. Dr. Seymour is family medicine hospitalist education director at the University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, and associate professor at the University of Massachusetts.

References

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. The Emerging Role of “Hospitalists” in the American Health Care System. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(7):514-7.

2. 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report. Philadelphia: Society of Hospital Medicine, 2018.

3. Weaver SP, Hill J. Academician Attitudes and Beliefs Regarding the Use of Hospitalists: A CERA Study. Fam Med. 2015;47(5):357-61.

4. Teno JM et al. Temporal Trends in the Numbers of Skilled Nursing Facility Specialists From 2007 Through 2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1376-8.

You’ve probably heard of a “nocturnist,” but have you ever heard of a “weekendist?”

The field of hospital medicine (HM) has evolved dramatically since the term “hospitalist” was introduced in the literature in 1996.1 There is a saying in HM that “if you know one HM program, you know one HM program,” alluding to the fact that every HM program is unique. The diversity of individual HM programs combined with the overall evolution of the field has expanded the range of jobs available in HM.

The nomenclature of adding an -ist to the end of the specific roles (e.g., nocturnist, weekendist) has become commonplace. These roles have developed with the increasing need for day and night staffing at many hospitals secondary to increased and more complex patients, less availability of residents because of work hour restrictions, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) rules that require overnight supervision of residents

Additionally, the field of HM increasingly includes physicians trained in internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, and medicine-pediatrics (med-peds). In this article, we describe the variety of roles available to trainees joining HM and the multitude of different training backgrounds hospitalists come from.

Nocturnists

The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report notes that 76.1% of adult-only HM groups have nocturnists, hospitalists who work primarily at night to admit and to provide coverage for admitted patients.2 Nocturnists often provide benefit to the rest of their hospitalist group by allowing fewer required night shifts for those that prefer to work during the day.

Nocturnists may choose a nighttime schedule for several reasons, including the ability to be home more during the day. They also have the potential to work fewer total hours or shifts while still earning a similar or increased income, compared with predominantly daytime hospitalists, increasing their flexibility to pursue other interests. These nocturnists become experts in navigating the admission process and responding to inpatient emergencies often with less support when compared with daytime hospitalists.

In addition to career nocturnist work, nocturnist jobs can be a great fit for those residency graduates who are undecided about fellowship and enjoy the acuity of inpatient medicine. It provides an opportunity to hone their clinical skill set prior to specialized training while earning an attending salary, and offers flexible hours which may allow for research or other endeavors. In academic centers, nocturnist educational roles take on a different character as well and may involve more 1:1 educational experiences. The role of nocturnists as educators is expanding as ACGME rules call for more oversight and educational opportunities for residents who are working at night.

However, challenges exist for nocturnists, including keeping abreast of new changes in their HM groups and hospital systems and engaging in quality initiatives, given that most meetings occur during the day. Additionally, nocturnists must adapt to sleeping during the day, potentially getting less sleep then they would otherwise and being “off cycle” with family and friends. For nocturnists raising children, being off cycle may be advantageous as it can allow them to be home with their children after school.

Weekendists

Another common hospitalist role is the weekendist, hospitalists who spend much of their clinical time preferentially working weekends. Similar to nocturnists, weekendists provide benefit to their hospitalist group by allowing others to have more weekends off.

Weekendists may prefer working weekends because of fewer total shifts or hours and/or higher compensation per shift. Additionally, weekendists have the flexibility to do other work on weekdays, such as research or another hospitalist job. For those that do nonclinical work during the week, a weekendist position may allow them to keep their clinical skills up to date. However, weekendists may face intense clinical days with a higher census because of fewer hospitalists rounding on the weekends.

Weekendists must balance having more potential time available during the weekdays but less time on the weekends to devote to family and friends. Furthermore, weekendists may feel less engaged with nonclinical opportunities, including quality improvement, educational offerings, and teaching opportunities.

SNFists

With increasing emphasis on transitions of care and the desire to avoid readmission penalties, some hospitalists have transitioned to work partly or primarily in skilled nursing facilities (SNF) and have been referred to as “SNFists.” Some of these hospitalists may split their clinical time between SNFs and acute care hospitals, while others may work exclusively at SNFs.

SNFists have the potential to be invaluable in improving transitions of care after discharge to post–acute care facilities because of increased provider presence in these facilities, comfort with medically complex patients, and appreciation of government regulations.4 SNFists may face potential challenges of needing to staff more than one post–acute care hospital and of having less resources available, compared with an acute care hospital.

Specific specialty hospitalists

For a variety of reasons including clinical interest, many hospitalists have become specialized with regards to their primary inpatient population. Some hospitalists spend the majority of their clinical time on a specific service in the hospital, often working closely with the subspecialist caring for that patient. These hospitalists may focus on hematology, oncology, bone-marrow transplant, neurology, cardiology, surgery services, or critical care, among others. Hospitalists focused on a specific service often become knowledge experts in that specialty. Conversely, by focusing on a specific service, certain pathologies may be less commonly seen, which may narrow the breadth of the hospital medicine job.

Hospitalist training

Internal medicine hospitalists may be the most common hospitalists encountered in many hospitals and at each Society of Hospital Medicine annual conference, but there has also been rapid growth in hospitalists from other specialties and backgrounds.

Family medicine hospitalists are a part of 64.9% of HM groups and about 9% of family medicine graduates are choosing HM as a career path.2,3 Most family medicine hospitalists work in adult HM groups, but some, particularly in rural or academic settings, care for pediatric, newborn, and/or maternity patients. Similarly, pediatric hospitalists have become entrenched at many hospitals where children are admitted. These pediatric hospitalists, like adult hospitalists, may work in a variety of different clinical roles including in EDs, newborn nurseries, and inpatient wards or ICUs; they may also provide consult, sedation, or procedural services.

Med-peds hospitalists that split time between internal medicine and pediatrics are becoming more commonplace in the field. Many work at academic centers where they often work on each side separately, doing the same work as their internal medicine or pediatrics colleagues, and then switching to the other side after a period of time. Some centers offer unique roles for med-peds hospitalists including working on adult consult teams in children’s hospitals, where they provide consult care to older patients that may still receive their care at a children’s hospital. There are also nonacademic hospitals that primarily staff med-peds hospitalists, where they can provide the full spectrum of care from the newborn nursery to the inpatient pediatric and adult wards.

Hospital medicine is a young field that is constantly changing with new and developing roles for hospitalists from a wide variety of backgrounds. Stick around to see which “-ist” will come next in HM.

Dr. Hall is a med-peds hospitalist and assistant professor at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Sanyal-Dey is an academic hospitalist at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center and the University of California, San Francisco, where she is the director of clinical operations, and director of the faculty inpatient service. Dr. Chang is associate professor and interprofessional education thread director (MD curriculum) at Washington University, St. Louis. Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System and associate professor at the University of California, San Diego. He is the chair of SHM’s Physicians in Training committee. Dr. Seymour is family medicine hospitalist education director at the University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, and associate professor at the University of Massachusetts.

References

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. The Emerging Role of “Hospitalists” in the American Health Care System. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(7):514-7.

2. 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report. Philadelphia: Society of Hospital Medicine, 2018.

3. Weaver SP, Hill J. Academician Attitudes and Beliefs Regarding the Use of Hospitalists: A CERA Study. Fam Med. 2015;47(5):357-61.

4. Teno JM et al. Temporal Trends in the Numbers of Skilled Nursing Facility Specialists From 2007 Through 2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1376-8.

PTSD in the inpatient setting

A problem hiding in plain sight

“I need to get out of here! I haven’t gotten any sleep, my medications never come on time, and I feel like a pincushion. I am leaving NOW!” The commotion interrupts your intern’s meticulous presentation as your team quickly files into the room. You find a disheveled, visibly frustrated man tearing at his intravenous line, surrounded by his half-eaten breakfast and multiple urinals filled to various levels. His IV pump is beeping, and telemetry wires hang haphazardly off his chest.

Mr. Smith had been admitted for a heart failure exacerbation. You’d been making steady progress with diuresis but are now faced with a likely discharge against medical advice if you can’t defuse the situation.

As hospitalists, this scenario might feel eerily familiar. Perhaps Mr. Smith had enough of being in the hospital and just wanted to go home to see his dog, or maybe the food was not up to his standards.

However, his next line stops your team dead in its tracks. “I feel like I am in Vietnam all over again. I am tied up with all these wires and feel like a prisoner! Please let me go.” It turns out that Mr. Smith had a comorbidity that was overlooked during his initial intake: posttraumatic stress disorder.

Impact of PTSD

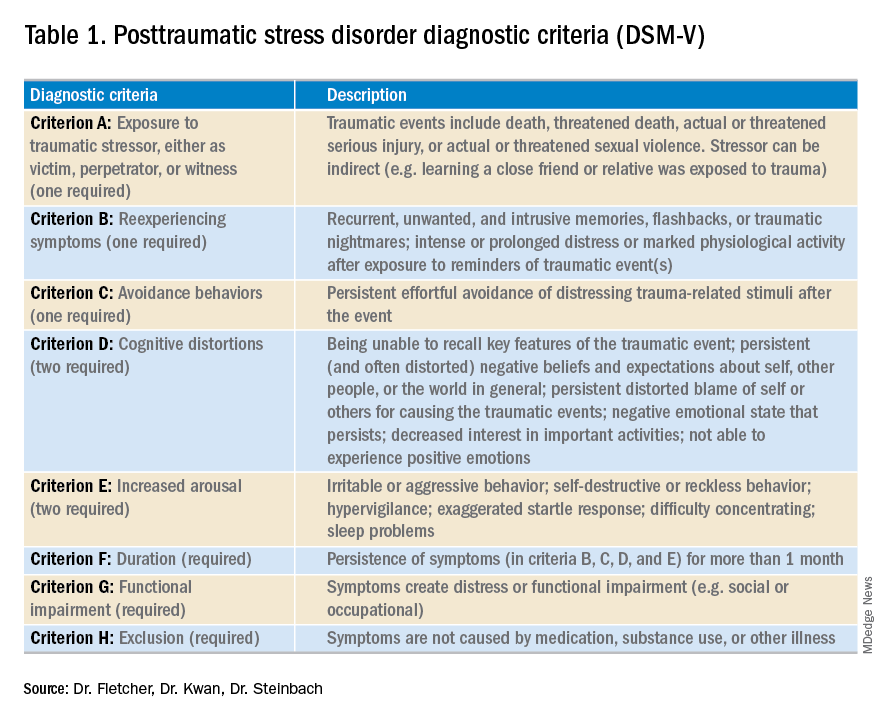

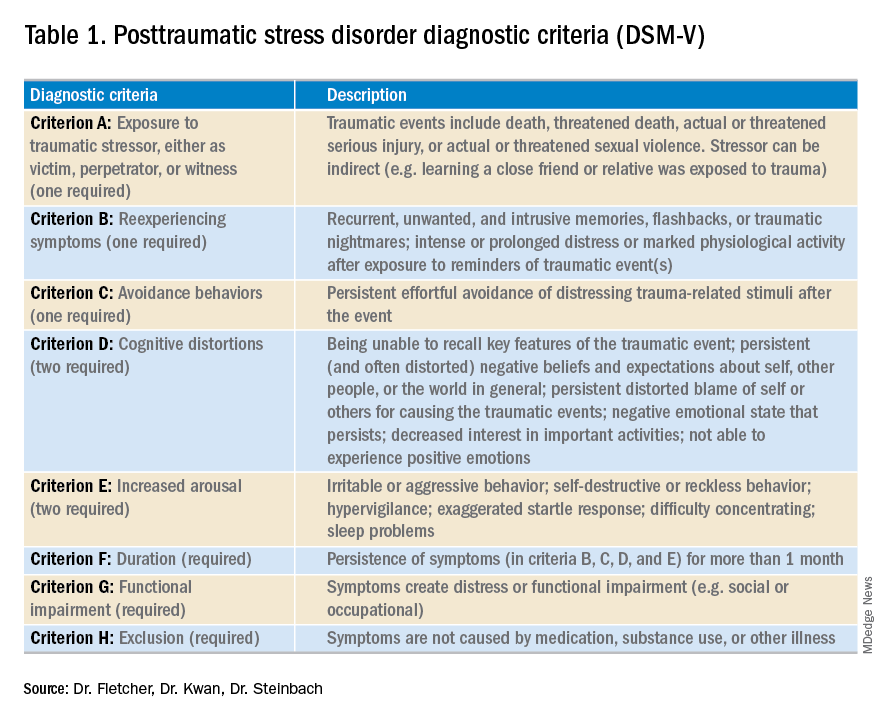

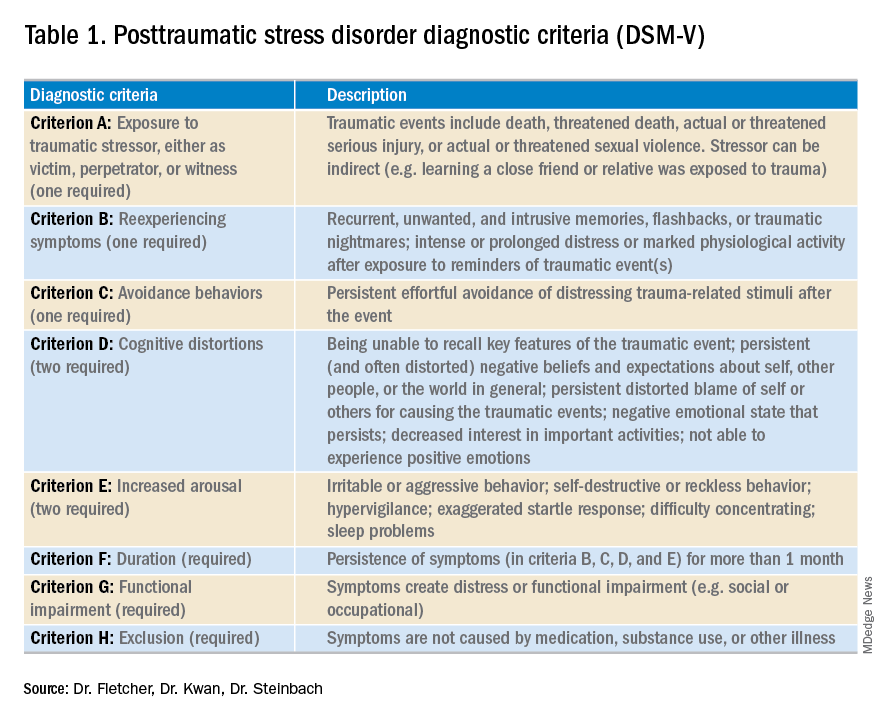

PTSD is a diagnosis characterized by intrusive recurrent thoughts, dreams, or flashbacks that follow exposure to a traumatic event or series of events (see Table 1). While more common among veterans (for example, Vietnam veterans have an estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD of 30.9% for men and 26.9% for women),1 a national survey of U.S. households estimated the lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adult Americans to be 6.8%.2 PTSD is often underdiagnosed and underreported by patients in the outpatient setting, leading to underrecognition and undertreatment of these patients in the inpatient setting.

Although it may not be surprising that patients with PTSD use more mental health services, they are also more likely to use nonmental health services. In one study, total utilization of outpatient nonmental health services was 91% greater in veterans with PTSD, and these patients were three times more likely to be hospitalized than those without any mental health diagnoses.3 Additionally, they are likely to present later and stay longer when compared with patients without PTSD. One study estimated the cost of PTSD-related hospitalization in the United States from 2002 to 2011 as being $34.9 billion.4 Notably, close to 95% of hospitalizations in this study listed PTSD as a secondary rather than primary diagnosis, suggesting that the vast majority of these admitted patients are cared for by frontline providers who are not trained mental health professionals.

How PTSD manifests in the hospital

But, how exactly can the hospital environment contribute to decompensation of PTSD symptoms? Unfortunately, there is little empiric data to guide us. Based on what we do know of PTSD, we offer the following hypotheses.

Patients with PTSD may feel a loss of control or helplessness when admitted to the inpatient setting. For example, they cannot control when they receive their medications or when they get their meals. The act of showering or going outside requires approval. In addition, they might perceive they are being “ordered around” by staff and may be carted off to a study without knowing why the study is being done in the first place.

Triggers in the hospital environment may contribute to PTSD flares. Think about the loud, beeping IV pump that constantly goes off at random intervals, disrupting sleep. What about a blood draw in the early morning where the phlebotomist sticks a needle into the arm of a sleeping patient? Or the well-intentioned provider doing prerounds who wakes a sleeping patient with a shake of the shoulder or some other form of physical touch? The multidisciplinary team crowding around their hospital bed? For a patient suffering from PTSD, any of these could easily set off a cascade of escalating symptoms.

Knowing that these triggers exist, can anything be done to ameliorate their effects? We propose some practical suggestions for improving the hospital experience for patients with PTSD.

Strategies to combat PTSD in the inpatient setting

Perhaps the most practical place to start is with preserving sleep in hospitalized patients with PTSD. The majority of patients with PTSD have sleep disturbances, and interrupted sleep routines in these patients can exacerbate nightmares and underlying psychiatric issues.5 Therefore, we should strive to avoid unnecessary awakenings.

While this principle holds true for all hospitalized patients, it must be especially prioritized in patients with PTSD. Ask yourself these questions during your next admission: Must intravenous fluids run 24 hours a day, or could they be stopped at 6 p.m.? Are vital signs needed overnight? Could the last dose of furosemide occur at 4 p.m. to avoid nocturia?

Another strategy involves bedtime routines. Many of these patients may already follow a home sleep routine as part of their chronic PTSD management. To honor these habits in the hospital might mean that staff encourage turning the lights and the television off at a designated time. Additionally, the literature suggests music therapy can have a significant impact on enhanced sleep quality. When available, music therapy may reduce insomnia and decrease the amount of time prior to falling asleep.6

Other methods to counteract PTSD fall under the general principle of “trauma-informed care.” Trauma-informed care comprises practices promoting a culture of safety, empowerment, and healing.7 It is a mindful and sensitive approach that acknowledges the pervasive nature of trauma exposure, the reality of ongoing adverse effects in trauma survivors, and the fact that recovery is highly personal and complex.8

By definition, patients with PTSD have endured some traumatic event. Therefore, ideal care teams will ask patients about things that may trigger their anxiety and then work to mitigate them. For example, some patients with PTSD have a severe startle response when woken up by someone touching them. When patients feel that they can share their concerns with their care team and their team honors that observation by waking them in a different way, trust and control may be gained. This process of asking for patient guidance and adjusting accordingly is consistent with a trauma-informed care approach.9 A true trauma-informed care approach involves the entire practice environment but examining and adjusting our own behavior and assumptions are good places to start.

Summary of recommended treatments

Psychotherapy is preferable over pharmacotherapy, but both can be combined as needed. Individual trauma-focused psychotherapies utilizing a primary component of exposure and/or cognitive restructuring have strong evidence for effectiveness but are primarily outpatient based.

For pharmacologic treatment, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (for example, sertraline, paroxetine, or fluoxetine) and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (for example, venlafaxine) monotherapy have strong evidence for effectiveness and can be started while inpatient. However, these medications typically take weeks to produce benefits. Recent trials studying prazosin, an alpha1-adrenergic receptor antagonist used to alleviate nightmares associated with PTSD, have demonstrated inefficacy or even harm,leading experts to caution against its use.10,11 Finally, benzodiazepine and atypical antipsychotic usage should be restricted and used as a last resort.12

In summary, PTSD is common among veterans and nonveterans. While hospitalists may rarely admit patients because of their PTSD, they will often take care of patients who have PTSD as a comorbidity. Therefore, understanding the basics of PTSD and how hospitalization may exacerbate its symptoms can meaningfully improve care for these patients.

Dr. Fletcher is a hospitalist at the Milwaukee Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Froedtert Hospital in Wauwatosa, Wis. She is professor of internal medicine and program director for the internal medicine residency program at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. She is also faculty mentor for the VA’s Chief Resident for Quality and Safety. Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the VA San Diego Healthcare System and is associate professor at the University of California, San Diego, in the division of hospital medicine. He serves as an associate clerkship director of both the internal medicine clerkship and the medicine subinternship. He is the chair of SHM’s Physicians in Training committee. Dr. Steinbach is chief of hospital medicine at the Atlanta VA Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

References

1. Kang HK et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and chronic fatigue syndrome–like illness among Gulf War veterans: A population-based survey of 30,000 veterans. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(2):141-8.

2. Kessler RC et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005; 62(6):593-602.

3. Cohen BE et al. Mental health diagnoses and utilization of VA nonmental health medical services among returning Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):18-24.

4. Haviland MG et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder–related hospitalizations in the United States (2002-2011): Rates, co-occurring illnesses, suicidal ideation/self-harm, and hospital charges. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016; 204(2):78-86.

5. Aurora RN et al. Best practice guide for the treatment of nightmare disorder in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6(4):389-401.

6. Blanaru M et al. The effects of music relaxation and muscle relaxation techniques on sleep quality and emotional measures among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder. Ment Illn. 2012;4(2):e13.

7. Tello M. (2018, Oct 16). Trauma-informed care: What it is, and why it’s important. Retrieved March 18, 2019, from https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/trauma-informed-care-what-it-is-and-why-its-important-2018101613562.

8. Harris M et al. Using trauma theory to design service systems. San Francisco: 2001.

9. Substance abuse and mental health services administration. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS publication no. SMA 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014.

10. Raskind MA et al. Trial of prazosin for posttraumatic stress disorder in military veterans. N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 8;378(6):507-7.

11. McCall WV et al. A pilot, randomized clinical trial of bedtime doses of prazosin versus placebo in suicidal posttraumatic stress disorder patients with nightmares. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018 Dec;38(6):618-21.

12. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs/U.S. Department of Defense. Clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress reaction 2017. Accessed February 18, 2019.

A problem hiding in plain sight

A problem hiding in plain sight

“I need to get out of here! I haven’t gotten any sleep, my medications never come on time, and I feel like a pincushion. I am leaving NOW!” The commotion interrupts your intern’s meticulous presentation as your team quickly files into the room. You find a disheveled, visibly frustrated man tearing at his intravenous line, surrounded by his half-eaten breakfast and multiple urinals filled to various levels. His IV pump is beeping, and telemetry wires hang haphazardly off his chest.

Mr. Smith had been admitted for a heart failure exacerbation. You’d been making steady progress with diuresis but are now faced with a likely discharge against medical advice if you can’t defuse the situation.

As hospitalists, this scenario might feel eerily familiar. Perhaps Mr. Smith had enough of being in the hospital and just wanted to go home to see his dog, or maybe the food was not up to his standards.

However, his next line stops your team dead in its tracks. “I feel like I am in Vietnam all over again. I am tied up with all these wires and feel like a prisoner! Please let me go.” It turns out that Mr. Smith had a comorbidity that was overlooked during his initial intake: posttraumatic stress disorder.

Impact of PTSD

PTSD is a diagnosis characterized by intrusive recurrent thoughts, dreams, or flashbacks that follow exposure to a traumatic event or series of events (see Table 1). While more common among veterans (for example, Vietnam veterans have an estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD of 30.9% for men and 26.9% for women),1 a national survey of U.S. households estimated the lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adult Americans to be 6.8%.2 PTSD is often underdiagnosed and underreported by patients in the outpatient setting, leading to underrecognition and undertreatment of these patients in the inpatient setting.

Although it may not be surprising that patients with PTSD use more mental health services, they are also more likely to use nonmental health services. In one study, total utilization of outpatient nonmental health services was 91% greater in veterans with PTSD, and these patients were three times more likely to be hospitalized than those without any mental health diagnoses.3 Additionally, they are likely to present later and stay longer when compared with patients without PTSD. One study estimated the cost of PTSD-related hospitalization in the United States from 2002 to 2011 as being $34.9 billion.4 Notably, close to 95% of hospitalizations in this study listed PTSD as a secondary rather than primary diagnosis, suggesting that the vast majority of these admitted patients are cared for by frontline providers who are not trained mental health professionals.

How PTSD manifests in the hospital

But, how exactly can the hospital environment contribute to decompensation of PTSD symptoms? Unfortunately, there is little empiric data to guide us. Based on what we do know of PTSD, we offer the following hypotheses.

Patients with PTSD may feel a loss of control or helplessness when admitted to the inpatient setting. For example, they cannot control when they receive their medications or when they get their meals. The act of showering or going outside requires approval. In addition, they might perceive they are being “ordered around” by staff and may be carted off to a study without knowing why the study is being done in the first place.

Triggers in the hospital environment may contribute to PTSD flares. Think about the loud, beeping IV pump that constantly goes off at random intervals, disrupting sleep. What about a blood draw in the early morning where the phlebotomist sticks a needle into the arm of a sleeping patient? Or the well-intentioned provider doing prerounds who wakes a sleeping patient with a shake of the shoulder or some other form of physical touch? The multidisciplinary team crowding around their hospital bed? For a patient suffering from PTSD, any of these could easily set off a cascade of escalating symptoms.

Knowing that these triggers exist, can anything be done to ameliorate their effects? We propose some practical suggestions for improving the hospital experience for patients with PTSD.

Strategies to combat PTSD in the inpatient setting

Perhaps the most practical place to start is with preserving sleep in hospitalized patients with PTSD. The majority of patients with PTSD have sleep disturbances, and interrupted sleep routines in these patients can exacerbate nightmares and underlying psychiatric issues.5 Therefore, we should strive to avoid unnecessary awakenings.

While this principle holds true for all hospitalized patients, it must be especially prioritized in patients with PTSD. Ask yourself these questions during your next admission: Must intravenous fluids run 24 hours a day, or could they be stopped at 6 p.m.? Are vital signs needed overnight? Could the last dose of furosemide occur at 4 p.m. to avoid nocturia?

Another strategy involves bedtime routines. Many of these patients may already follow a home sleep routine as part of their chronic PTSD management. To honor these habits in the hospital might mean that staff encourage turning the lights and the television off at a designated time. Additionally, the literature suggests music therapy can have a significant impact on enhanced sleep quality. When available, music therapy may reduce insomnia and decrease the amount of time prior to falling asleep.6

Other methods to counteract PTSD fall under the general principle of “trauma-informed care.” Trauma-informed care comprises practices promoting a culture of safety, empowerment, and healing.7 It is a mindful and sensitive approach that acknowledges the pervasive nature of trauma exposure, the reality of ongoing adverse effects in trauma survivors, and the fact that recovery is highly personal and complex.8

By definition, patients with PTSD have endured some traumatic event. Therefore, ideal care teams will ask patients about things that may trigger their anxiety and then work to mitigate them. For example, some patients with PTSD have a severe startle response when woken up by someone touching them. When patients feel that they can share their concerns with their care team and their team honors that observation by waking them in a different way, trust and control may be gained. This process of asking for patient guidance and adjusting accordingly is consistent with a trauma-informed care approach.9 A true trauma-informed care approach involves the entire practice environment but examining and adjusting our own behavior and assumptions are good places to start.

Summary of recommended treatments

Psychotherapy is preferable over pharmacotherapy, but both can be combined as needed. Individual trauma-focused psychotherapies utilizing a primary component of exposure and/or cognitive restructuring have strong evidence for effectiveness but are primarily outpatient based.

For pharmacologic treatment, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (for example, sertraline, paroxetine, or fluoxetine) and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (for example, venlafaxine) monotherapy have strong evidence for effectiveness and can be started while inpatient. However, these medications typically take weeks to produce benefits. Recent trials studying prazosin, an alpha1-adrenergic receptor antagonist used to alleviate nightmares associated with PTSD, have demonstrated inefficacy or even harm,leading experts to caution against its use.10,11 Finally, benzodiazepine and atypical antipsychotic usage should be restricted and used as a last resort.12

In summary, PTSD is common among veterans and nonveterans. While hospitalists may rarely admit patients because of their PTSD, they will often take care of patients who have PTSD as a comorbidity. Therefore, understanding the basics of PTSD and how hospitalization may exacerbate its symptoms can meaningfully improve care for these patients.

Dr. Fletcher is a hospitalist at the Milwaukee Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Froedtert Hospital in Wauwatosa, Wis. She is professor of internal medicine and program director for the internal medicine residency program at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. She is also faculty mentor for the VA’s Chief Resident for Quality and Safety. Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the VA San Diego Healthcare System and is associate professor at the University of California, San Diego, in the division of hospital medicine. He serves as an associate clerkship director of both the internal medicine clerkship and the medicine subinternship. He is the chair of SHM’s Physicians in Training committee. Dr. Steinbach is chief of hospital medicine at the Atlanta VA Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

References

1. Kang HK et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and chronic fatigue syndrome–like illness among Gulf War veterans: A population-based survey of 30,000 veterans. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(2):141-8.

2. Kessler RC et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005; 62(6):593-602.

3. Cohen BE et al. Mental health diagnoses and utilization of VA nonmental health medical services among returning Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):18-24.

4. Haviland MG et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder–related hospitalizations in the United States (2002-2011): Rates, co-occurring illnesses, suicidal ideation/self-harm, and hospital charges. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016; 204(2):78-86.

5. Aurora RN et al. Best practice guide for the treatment of nightmare disorder in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6(4):389-401.

6. Blanaru M et al. The effects of music relaxation and muscle relaxation techniques on sleep quality and emotional measures among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder. Ment Illn. 2012;4(2):e13.

7. Tello M. (2018, Oct 16). Trauma-informed care: What it is, and why it’s important. Retrieved March 18, 2019, from https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/trauma-informed-care-what-it-is-and-why-its-important-2018101613562.

8. Harris M et al. Using trauma theory to design service systems. San Francisco: 2001.

9. Substance abuse and mental health services administration. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS publication no. SMA 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014.

10. Raskind MA et al. Trial of prazosin for posttraumatic stress disorder in military veterans. N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 8;378(6):507-7.

11. McCall WV et al. A pilot, randomized clinical trial of bedtime doses of prazosin versus placebo in suicidal posttraumatic stress disorder patients with nightmares. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018 Dec;38(6):618-21.

12. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs/U.S. Department of Defense. Clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress reaction 2017. Accessed February 18, 2019.

“I need to get out of here! I haven’t gotten any sleep, my medications never come on time, and I feel like a pincushion. I am leaving NOW!” The commotion interrupts your intern’s meticulous presentation as your team quickly files into the room. You find a disheveled, visibly frustrated man tearing at his intravenous line, surrounded by his half-eaten breakfast and multiple urinals filled to various levels. His IV pump is beeping, and telemetry wires hang haphazardly off his chest.

Mr. Smith had been admitted for a heart failure exacerbation. You’d been making steady progress with diuresis but are now faced with a likely discharge against medical advice if you can’t defuse the situation.

As hospitalists, this scenario might feel eerily familiar. Perhaps Mr. Smith had enough of being in the hospital and just wanted to go home to see his dog, or maybe the food was not up to his standards.

However, his next line stops your team dead in its tracks. “I feel like I am in Vietnam all over again. I am tied up with all these wires and feel like a prisoner! Please let me go.” It turns out that Mr. Smith had a comorbidity that was overlooked during his initial intake: posttraumatic stress disorder.

Impact of PTSD

PTSD is a diagnosis characterized by intrusive recurrent thoughts, dreams, or flashbacks that follow exposure to a traumatic event or series of events (see Table 1). While more common among veterans (for example, Vietnam veterans have an estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD of 30.9% for men and 26.9% for women),1 a national survey of U.S. households estimated the lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adult Americans to be 6.8%.2 PTSD is often underdiagnosed and underreported by patients in the outpatient setting, leading to underrecognition and undertreatment of these patients in the inpatient setting.

Although it may not be surprising that patients with PTSD use more mental health services, they are also more likely to use nonmental health services. In one study, total utilization of outpatient nonmental health services was 91% greater in veterans with PTSD, and these patients were three times more likely to be hospitalized than those without any mental health diagnoses.3 Additionally, they are likely to present later and stay longer when compared with patients without PTSD. One study estimated the cost of PTSD-related hospitalization in the United States from 2002 to 2011 as being $34.9 billion.4 Notably, close to 95% of hospitalizations in this study listed PTSD as a secondary rather than primary diagnosis, suggesting that the vast majority of these admitted patients are cared for by frontline providers who are not trained mental health professionals.

How PTSD manifests in the hospital

But, how exactly can the hospital environment contribute to decompensation of PTSD symptoms? Unfortunately, there is little empiric data to guide us. Based on what we do know of PTSD, we offer the following hypotheses.

Patients with PTSD may feel a loss of control or helplessness when admitted to the inpatient setting. For example, they cannot control when they receive their medications or when they get their meals. The act of showering or going outside requires approval. In addition, they might perceive they are being “ordered around” by staff and may be carted off to a study without knowing why the study is being done in the first place.

Triggers in the hospital environment may contribute to PTSD flares. Think about the loud, beeping IV pump that constantly goes off at random intervals, disrupting sleep. What about a blood draw in the early morning where the phlebotomist sticks a needle into the arm of a sleeping patient? Or the well-intentioned provider doing prerounds who wakes a sleeping patient with a shake of the shoulder or some other form of physical touch? The multidisciplinary team crowding around their hospital bed? For a patient suffering from PTSD, any of these could easily set off a cascade of escalating symptoms.

Knowing that these triggers exist, can anything be done to ameliorate their effects? We propose some practical suggestions for improving the hospital experience for patients with PTSD.

Strategies to combat PTSD in the inpatient setting

Perhaps the most practical place to start is with preserving sleep in hospitalized patients with PTSD. The majority of patients with PTSD have sleep disturbances, and interrupted sleep routines in these patients can exacerbate nightmares and underlying psychiatric issues.5 Therefore, we should strive to avoid unnecessary awakenings.

While this principle holds true for all hospitalized patients, it must be especially prioritized in patients with PTSD. Ask yourself these questions during your next admission: Must intravenous fluids run 24 hours a day, or could they be stopped at 6 p.m.? Are vital signs needed overnight? Could the last dose of furosemide occur at 4 p.m. to avoid nocturia?

Another strategy involves bedtime routines. Many of these patients may already follow a home sleep routine as part of their chronic PTSD management. To honor these habits in the hospital might mean that staff encourage turning the lights and the television off at a designated time. Additionally, the literature suggests music therapy can have a significant impact on enhanced sleep quality. When available, music therapy may reduce insomnia and decrease the amount of time prior to falling asleep.6

Other methods to counteract PTSD fall under the general principle of “trauma-informed care.” Trauma-informed care comprises practices promoting a culture of safety, empowerment, and healing.7 It is a mindful and sensitive approach that acknowledges the pervasive nature of trauma exposure, the reality of ongoing adverse effects in trauma survivors, and the fact that recovery is highly personal and complex.8

By definition, patients with PTSD have endured some traumatic event. Therefore, ideal care teams will ask patients about things that may trigger their anxiety and then work to mitigate them. For example, some patients with PTSD have a severe startle response when woken up by someone touching them. When patients feel that they can share their concerns with their care team and their team honors that observation by waking them in a different way, trust and control may be gained. This process of asking for patient guidance and adjusting accordingly is consistent with a trauma-informed care approach.9 A true trauma-informed care approach involves the entire practice environment but examining and adjusting our own behavior and assumptions are good places to start.

Summary of recommended treatments

Psychotherapy is preferable over pharmacotherapy, but both can be combined as needed. Individual trauma-focused psychotherapies utilizing a primary component of exposure and/or cognitive restructuring have strong evidence for effectiveness but are primarily outpatient based.

For pharmacologic treatment, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (for example, sertraline, paroxetine, or fluoxetine) and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (for example, venlafaxine) monotherapy have strong evidence for effectiveness and can be started while inpatient. However, these medications typically take weeks to produce benefits. Recent trials studying prazosin, an alpha1-adrenergic receptor antagonist used to alleviate nightmares associated with PTSD, have demonstrated inefficacy or even harm,leading experts to caution against its use.10,11 Finally, benzodiazepine and atypical antipsychotic usage should be restricted and used as a last resort.12

In summary, PTSD is common among veterans and nonveterans. While hospitalists may rarely admit patients because of their PTSD, they will often take care of patients who have PTSD as a comorbidity. Therefore, understanding the basics of PTSD and how hospitalization may exacerbate its symptoms can meaningfully improve care for these patients.

Dr. Fletcher is a hospitalist at the Milwaukee Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Froedtert Hospital in Wauwatosa, Wis. She is professor of internal medicine and program director for the internal medicine residency program at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. She is also faculty mentor for the VA’s Chief Resident for Quality and Safety. Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the VA San Diego Healthcare System and is associate professor at the University of California, San Diego, in the division of hospital medicine. He serves as an associate clerkship director of both the internal medicine clerkship and the medicine subinternship. He is the chair of SHM’s Physicians in Training committee. Dr. Steinbach is chief of hospital medicine at the Atlanta VA Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

References

1. Kang HK et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and chronic fatigue syndrome–like illness among Gulf War veterans: A population-based survey of 30,000 veterans. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(2):141-8.

2. Kessler RC et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005; 62(6):593-602.

3. Cohen BE et al. Mental health diagnoses and utilization of VA nonmental health medical services among returning Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):18-24.

4. Haviland MG et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder–related hospitalizations in the United States (2002-2011): Rates, co-occurring illnesses, suicidal ideation/self-harm, and hospital charges. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016; 204(2):78-86.

5. Aurora RN et al. Best practice guide for the treatment of nightmare disorder in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6(4):389-401.

6. Blanaru M et al. The effects of music relaxation and muscle relaxation techniques on sleep quality and emotional measures among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder. Ment Illn. 2012;4(2):e13.

7. Tello M. (2018, Oct 16). Trauma-informed care: What it is, and why it’s important. Retrieved March 18, 2019, from https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/trauma-informed-care-what-it-is-and-why-its-important-2018101613562.

8. Harris M et al. Using trauma theory to design service systems. San Francisco: 2001.

9. Substance abuse and mental health services administration. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS publication no. SMA 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014.

10. Raskind MA et al. Trial of prazosin for posttraumatic stress disorder in military veterans. N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 8;378(6):507-7.

11. McCall WV et al. A pilot, randomized clinical trial of bedtime doses of prazosin versus placebo in suicidal posttraumatic stress disorder patients with nightmares. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018 Dec;38(6):618-21.

12. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs/U.S. Department of Defense. Clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress reaction 2017. Accessed February 18, 2019.

The changing landscape of medical education

A brave new world

It’s Monday morning, and your intern is presenting an overnight admission. Lost in the details of his disorganized introduction, your mind wanders. “Why doesn’t this intern know how to present? When I trained, all those admissions during long sleepless nights really taught me to do this right.” But can we equate hours worked with competency achieved? And if not, what is the alternative? This article introduces some major changes in medical education and their implications for hospitalists.

Most hospitalists trained in an educational system influenced by Sir William Osler. In the early 1900s, he introduced the natural method of teaching, positing that student exposure to patients and experience over time ensured that physicians in training would become competent doctors.1 His influence led to the current structure of medical education, which includes conventional third-year clerkships and time-limited rotations (such as a 2-week nephrology block).

While familiarity may be comforting, there are signs our current model of medical education is inefficient, inadequate, and obsolete.

For one, the traditional system is failing to adequately prepare physicians to provide safe and complex care. Reports, such as the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) “To Err is Human,”2 describe a high rate of preventable errors, highlighting considerable room for improvement in training the next generation of physicians.3,4

Meanwhile, trainees are still largely being deemed ready for the workforce by length of training completed (for example, completion of four-year medical school) rather than a skill set distinctly achieved. Our system leaves little flexibility to individualize learner goals, which is significant given some students and residents take shorter or longer periods of time to achieve proficiency. In addition, learner outcomes can be quite variable, as we have all experienced.

Even our methods of assessment may not adequately evaluate trainees’ skill sets. For example, most clerkships still rely heavily on the shelf exam5 as a surrogate for medical knowledge. As such, learners may conclude that testing performance trumps development of other professional skills.6 Efforts are being made to revamp evaluation systems to reflect mastery (such as Entrustable Professional Activities, or EPAs) toward competencies.7 Still, many institutions continue to rely on faculty evaluations that often reflect interpersonal dynamics rather than true critical thinking skills.6

Recognizing the above limitations, many educators have called for changing to outcome-based, or competency-based, training (CBME). CBME targets attainment of skills in performing concrete critical clinical activities,8 such as identifying unstable patients, providing initial management, and obtaining help. To be successful, supervisors must directly observe trainees, assess demonstrated skills, and provide feedback about progress.

Unfortunately, this considerable investment of time and effort is often poorly compensated. Additionally, unanswered questions remain. For example, how will residency programs continue to challenge physicians deemed “competent” in a required skill? What happens when a trainee is deficient and not appropriately progressing in a required skill? Is flexible training time part of the future of medical education? While CBME appears to be a more effective method of education, questions like these must be addressed during implementation.

Beyond the fact that hours worked cannot be used as a surrogate for competency, excessive unregulated work hours can be detrimental to learners, their supervisors, and patients. In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) implemented a major change in medical education: duty hour limitations. The premise that sleep-deprived providers are more prone to error is well established. However, controversy remains as to whether these regulations translate into improved patient care and provider well-being. Studies published following the ACGME change demonstrate increasing burnout among physicians,9-11 which has led some educators to explore the potential relationship between burnout and duty hour restrictions.

The recent “iCOMPARE” trial, which compared internal medicine (IM) residencies with “standard duty-hour” policies to those with “flexible” policies (that is, they did not specify limits on shift length or mandatory time off between shifts), supported a lack of correlation between hours worked and burnout.12 Researchers administered the Maslach Burnout Inventory to all participants.13 While those in the “flexible hours” arm reported greater dissatisfaction with the effect of the program on their personal lives, both groups reported significant burnout, with interns recording high scores in emotional exhaustion (79% in flexible programs vs. 72% in standard), depersonalization (75% vs. 72%), and lack of personal accomplishment (71% vs. 69%).

Disturbingly, these scores were not restricted to interns but were present in all residents. The good news? Limiting duty hours does not cause burnout. On the other hand, it does not protect from burnout. Trainee burnout appears to transcend the issue of hours worked. Clearly, we need to address the systemic flaws in our work environments that contribute to this epidemic. Nationwide, educators and organizations are continuing to define causes of burnout and test interventions to improve wellness.

A final front of change in medical education worth mentioning is the use of the electronic medical record (EMR). While the EMR has improved many aspects of patient care, its implementation is associated with decreased time spent with patients and parallels the rise in burnout. Another unforeseen consequence has been its disruptive impact on medical student documentation. A national survey of clerkship directors found that, while 64% of programs allowed students to use the EMR, only two-thirds of those programs permitted students to document electronically.14

Many institutions limit student access because of either liability concerns or the fact that student notes cannot be used to support medical billing. Concerning workarounds among preceptors, such as logging in students under their own credentials to write notes, have been identified.15 Yet medical students need to learn how to document a clinical encounter and maintain medical records.7,16 Authoring notes engages students, promotes a sense of patient ownership, and empowers them to feel like essential team members. Participating in the EMR also allows for critical feedback and skill development.

In 2016, the Society of Hospital Medicine joined several major internal medicine organizations in asking the federal government to reconsider guidelines prohibiting attendings from referring to medical student notes. In February 2018, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) revised its student documentation guidelines (see Box A), allowing teaching physicians to use all student documentation (not just Review of Systems, Family History, and Social History) for billable services.

While the guidelines officially went into effect in March 2018, many institutions are still fine-tuning their implementation, in part because of nonspecific policy language. For instance, if a student composes a note and a resident edits and signs it, can the attending physician simply cosign the resident note? Also, once a student has presented a case, can the attending see the patient and verify findings without the student present?

Despite the above challenges, the revision to CMS guidelines is a significant “win” and can potentially reduce the documentation burden on teaching physicians. With more oversight of their notes, the next generation of students will be encouraged to produce accurate, high-quality documentation.

In summary, these changes in the way we define competency, in duty hours, and in the use of the EMR demonstrate that medical education is continuously improving via robust critique and educator engagement in outcomes. We are fortunate to train in a system that respects the scientific method and utilizes data and critical events to drive important changes in practice. Understanding these changes might help hospitalists relate to the backgrounds and needs of learners. And who knows – maybe next time that intern will do a better job presenting!

Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System (VASDHS) and an associate professor at the University of California, San Diego, in the division of hospital medicine. He is the chair of the SHM Physicians in Training committee. Dr. Sebasky is an associate clinical professor at UCSD in the division of hospital medicine. Dr. Muchmore is a hematologist/oncologist and professor of clinical medicine in the department of medicine at UCSD and associate chief of staff for education at VASDHS.

References

1. Osler W. “The Hospital as a College.” In Aequanimitas. Osler W, Ed. (Philadelphia: P. Blakiston’s Son & Co., 1932).

2. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health Care System. (Washington: National Academies Press, 1999).

3. Ten Cate O. Competency-based postgraduate medical education: Past, present and future. GMS J Med Educ. 2017 Nov 15. doi: 10.3205/zma001146.

4. Carraccio C, Englander R, Van Melle E, et al. Advancing competency-based medical education: A charter for clinician–educators. Acad Med. 2016;91(5):645-9.

5. 2016 NBME Clinical Clerkship Subject Examination Survey.

6. Mehta NB, Hull AL, Young JB, et al. Just imagine: New paradigms for medical education. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1418-23.

7. Fazio SB, Ledford CH, Aronowitz PB, et al. Competency-based medical education in the internal medicine clerkship: A report from the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine Undergraduate Medical Education Task Force. Acad Med. 2018;93(3):421-7.

8. Ten Cate O, Scheele F. Competency-based postgraduate training: Can we bridge the gap between theory and clinical practice? Acad Med. 2007 Jun;82(6):542-7.

9. Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, et al. The relationship between physician burnout and quality of healthcare in terms of safety and acceptability: A systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015141.

10. Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, et al. Healthcare Staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: A systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159015.

11. Salyers MP, Bonfils KA, Luther L, et al. The relationship between professional burnout and quality and safety in healthcare: A meta-analysis. Gen Intern Med. 2017 Apr; 32(4):475-82.

12. Desai SV, Asch DA, Bellini LM, et al. Education outcomes in a duty hour flexibility trial in internal medicine. N Engl J Med. 2018 378:1494-508.

13. Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach burnout inventory manual. 3rd ed. (Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1996).

14. Hammoud MM, Margo K, Christner JG, et al. Opportunities and challenges in integrating electronic health records into undergraduate medical education: A national survey of clerkship directors. Teach Learn Med. 2012;24(3):219-24.

15. White J, Anthony D, WinklerPrins V, et al. Electronic medical records, medical students, and ambulatory family physicians: A multi-institution study. Acad Med. 2017;92(10):1485-90.

16. Pageler NM, Friedman CP, Longhurst CA. Refocusing medical education in the EMR era. JAMA 2013;310(21):2249-50.

Box A

“Students may document services in the medical record. However, the teaching physician must verify in the medical record all student documentation or findings, including history, physical exam, and/or medical decision making. The teaching physician must personally perform (or re-perform) the physical exam and medical decision making activities of the E/M service being billed, but may verify any student documentation of them in the medical record, rather than re-documenting this work.”

A brave new world

A brave new world

It’s Monday morning, and your intern is presenting an overnight admission. Lost in the details of his disorganized introduction, your mind wanders. “Why doesn’t this intern know how to present? When I trained, all those admissions during long sleepless nights really taught me to do this right.” But can we equate hours worked with competency achieved? And if not, what is the alternative? This article introduces some major changes in medical education and their implications for hospitalists.

Most hospitalists trained in an educational system influenced by Sir William Osler. In the early 1900s, he introduced the natural method of teaching, positing that student exposure to patients and experience over time ensured that physicians in training would become competent doctors.1 His influence led to the current structure of medical education, which includes conventional third-year clerkships and time-limited rotations (such as a 2-week nephrology block).

While familiarity may be comforting, there are signs our current model of medical education is inefficient, inadequate, and obsolete.

For one, the traditional system is failing to adequately prepare physicians to provide safe and complex care. Reports, such as the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) “To Err is Human,”2 describe a high rate of preventable errors, highlighting considerable room for improvement in training the next generation of physicians.3,4

Meanwhile, trainees are still largely being deemed ready for the workforce by length of training completed (for example, completion of four-year medical school) rather than a skill set distinctly achieved. Our system leaves little flexibility to individualize learner goals, which is significant given some students and residents take shorter or longer periods of time to achieve proficiency. In addition, learner outcomes can be quite variable, as we have all experienced.

Even our methods of assessment may not adequately evaluate trainees’ skill sets. For example, most clerkships still rely heavily on the shelf exam5 as a surrogate for medical knowledge. As such, learners may conclude that testing performance trumps development of other professional skills.6 Efforts are being made to revamp evaluation systems to reflect mastery (such as Entrustable Professional Activities, or EPAs) toward competencies.7 Still, many institutions continue to rely on faculty evaluations that often reflect interpersonal dynamics rather than true critical thinking skills.6

Recognizing the above limitations, many educators have called for changing to outcome-based, or competency-based, training (CBME). CBME targets attainment of skills in performing concrete critical clinical activities,8 such as identifying unstable patients, providing initial management, and obtaining help. To be successful, supervisors must directly observe trainees, assess demonstrated skills, and provide feedback about progress.

Unfortunately, this considerable investment of time and effort is often poorly compensated. Additionally, unanswered questions remain. For example, how will residency programs continue to challenge physicians deemed “competent” in a required skill? What happens when a trainee is deficient and not appropriately progressing in a required skill? Is flexible training time part of the future of medical education? While CBME appears to be a more effective method of education, questions like these must be addressed during implementation.

Beyond the fact that hours worked cannot be used as a surrogate for competency, excessive unregulated work hours can be detrimental to learners, their supervisors, and patients. In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) implemented a major change in medical education: duty hour limitations. The premise that sleep-deprived providers are more prone to error is well established. However, controversy remains as to whether these regulations translate into improved patient care and provider well-being. Studies published following the ACGME change demonstrate increasing burnout among physicians,9-11 which has led some educators to explore the potential relationship between burnout and duty hour restrictions.

The recent “iCOMPARE” trial, which compared internal medicine (IM) residencies with “standard duty-hour” policies to those with “flexible” policies (that is, they did not specify limits on shift length or mandatory time off between shifts), supported a lack of correlation between hours worked and burnout.12 Researchers administered the Maslach Burnout Inventory to all participants.13 While those in the “flexible hours” arm reported greater dissatisfaction with the effect of the program on their personal lives, both groups reported significant burnout, with interns recording high scores in emotional exhaustion (79% in flexible programs vs. 72% in standard), depersonalization (75% vs. 72%), and lack of personal accomplishment (71% vs. 69%).