User login

Management of Acute and Chronic Pain Associated With Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Comprehensive Review of Pharmacologic and Therapeutic Considerations in Clinical Practice

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory, androgen gland disorder characterized by recurrent rupture of the hair follicles with a vigorous inflammatory response. This response results in abscess formation and development of draining sinus tracts and hypertrophic fibrous scars.1,2 Pain, discomfort, and odorous discharge from the recalcitrant lesions have a profound impact on patient quality of life.3,4

The morbidity and disease burden associated with HS are particularly underestimated, as patients frequently report debilitating pain that often is overlooked.5,6 Additionally, the quality and intensity of perceived pain are compounded by frequently associated depression and anxiety.7-9 Pain has been reported by patients with HS to be the highest cause of morbidity, despite the disfiguring nature of the disease and its associated psychosocial distress.7,10 Nonetheless, HS lacks an accepted pain management algorithm similar to those that have been developed for the treatment of other acute or chronic pain disorders, such as back pain and sickle cell disease.4,11-13

Given the lack of formal studies regarding pain management in patients with HS, clinicians are limited to general pain guidelines, expert opinion, small trials, and patient preference.3 Furthermore, effective pain management in HS necessitates the treatment of both chronic pain affecting daily function and acute pain present during disease flares, surgical interventions, and dressing changes.3 The result is a wide array of strategies used for HS-associated pain.3,4

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Hidradenitis suppurativa historically has been an overlooked and underdiagnosed disease, which limits epidemiology data.5 Current estimates are that HS affects approximately 1% of the general population; however, prevalence rates range from 0.03% to 4.1%.14-16

The exact etiology of HS remains unclear, but it is thought that genetic factors, immune dysregulation, and environmental/behavioral influences all contribute to its pathophysiology.1,17 Up to 40% of patients with HS report a positive family history of the disease.18-20 Hidradenitis suppurativa has been associated with other inflammatory disease states, such as inflammatory bowel disease, spondyloarthropathies, and pyoderma gangrenosum.16,21,22

It is thought that HS is the result of some defect in keratin clearance that leads to follicular hyperkeratinization and occlusion.1 Resultant rupture of pilosebaceous units and spillage of contents (including keratin and bacteria) into the surrounding dermis triggers a vigorous inflammatory response. Sinus tracts and fistulas become the targets of bacterial colonization, biofilm formation, and secondary infection. The result is suppuration and extension of the lesions as well as sustained chronic inflammation.23,24

Although the etiology of HS is complex, several modifiable risk factors for the disease have been identified, most prominently cigarette smoking and obesity. Approximately 70% of patients with HS smoke cigarettes.2,15,25,26 Obesity has a well-known association with HS, and it is possible that weight reduction lowers disease severity.27-30

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Establishing a diagnosis of HS necessitates recognition of disease morphology, topography, and chronicity. Hidradenitis suppurativa most commonly occurs in the axillae, inguinal and anogenital region, perineal region, and inframammary region.5,31 A typical history involves a prolonged disease course with recurrent lesions and intermittent periods of improvement or remission. Primary lesions are deep, inflamed, painful, and sterile. Ultimately, these lesions rupture and track subcutaneously.15,25 Intercommunicating sinus tracts form from multiple recurrent nodules in close proximity and may ultimately lead to fibrotic scarring and local architectural distortion.32 The Hurley staging system helps to guide treatment interventions based on disease severity. Approach to pain management is discussed below.

Pain Management in HS: General Principles

Pain management is complex for clinicians, as there are limited studies from which to draw treatment recommendations. Incomplete understanding of the etiology and pathophysiology of the disease contributes to the lack of established management guidelines.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms hidradenitis, suppurativa, pain, and management revealed 61 different results dating back to 1980, 52 of which had been published in the last 5 years. When the word acute was added to the search, there were only 6 results identified. These results clearly reflect a better understanding of HS-mediated pain as well as clinical unmet needs and evolving strategies in pain management therapeutics. However, many of these studies reflect therapies focused on the mediation or modulation of HS pathogenesis rather than potential pain management therapies.

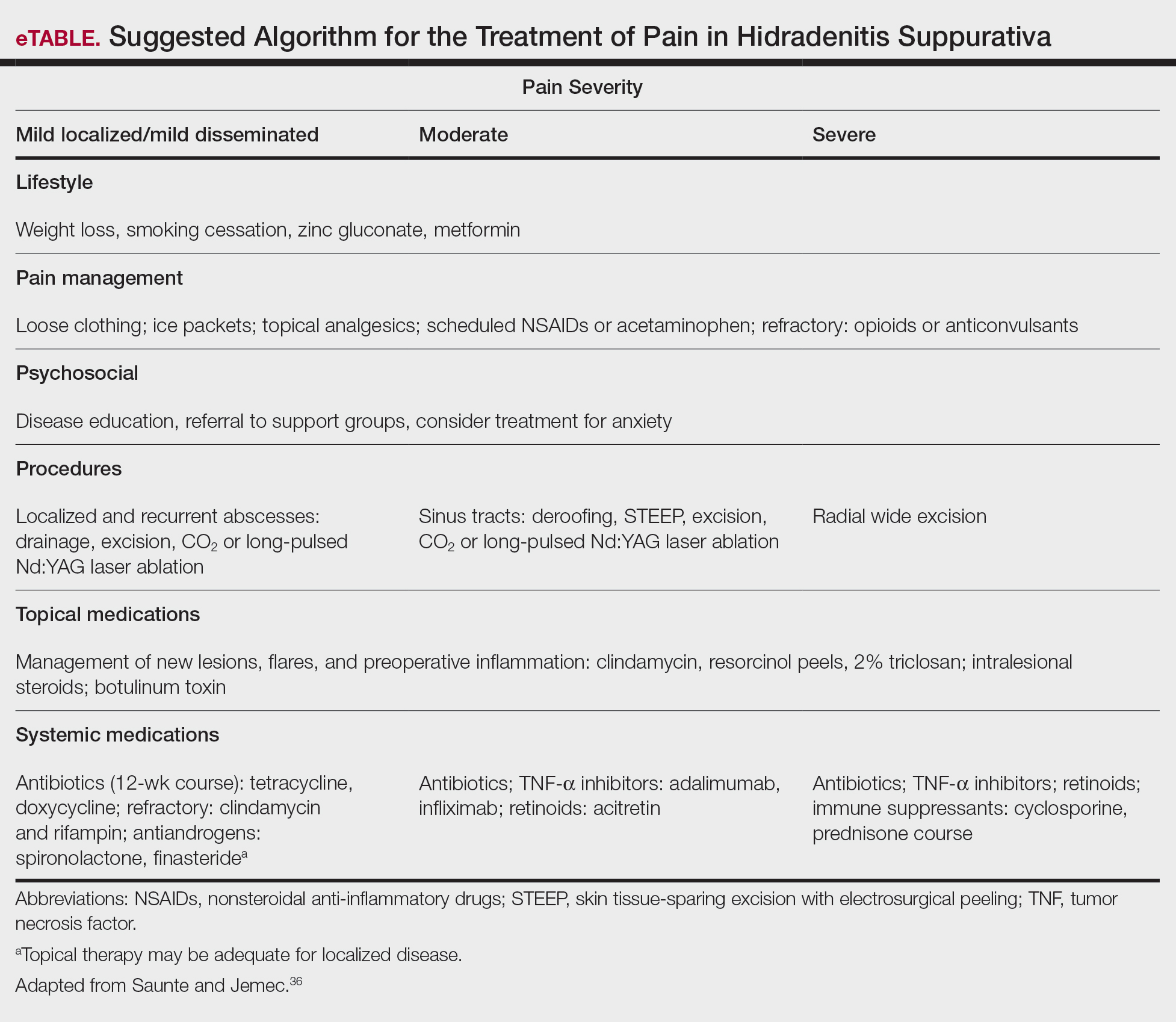

In addition, the heterogenous nature of the pain experience in HS poses a challenge for clinicians. Patients may experience multiple pain types concurrently, including inflammatory, noninflammatory, nociceptive, neuropathic, and ischemic, as well as pain related to arthritis.3,33,34 Pain perception is further complicated by the observation that patients with HS have high rates of psychiatric comorbidities such as depression and anxiety, both of which profoundly alter perception of both the strength and quality of pain.7,8,22,35 A suggested algorithm for treatment of pain in HS is described in the eTable.36

Chronicity is a hallmark of HS. Patients experience a prolonged disease course involving acute painful exacerbations superimposed on chronic pain that affects all aspects of daily life. Changes in self-perception, daily living activities, mood state, physical functioning, and physical comfort frequently are reported to have a major impact on quality of life.1,3,37

In 2018, Thorlacius et al38 created a multistakeholder consensus on a core outcome set of domains detailing what to measure in clinical trials for HS. The authors hoped that the routine adoption of these core domains would promote the collection of consistent and relevant information, bolster the strength of evidence synthesis, and minimize the risk for outcome reporting bias among studies.38 It is important to ascertain the patient’s description of his/her pain to distinguish between stimulus-dependent nociceptive pain vs spontaneous neuropathic pain.3,7,10 The most common pain descriptors used by patients are “shooting,” “itchy,” “blinding,” “cutting,” and “exhausting.”10 In addition to obtaining descriptive factors, it is important for the clinician to obtain information on the timing of the pain, whether or not the pain is relieved with spontaneous or surgical drainage, and if the patient is experiencing chronic background pain secondary to scarring or skin contraction.3 With the routine utilization of a consistent set of core domains, advances in our understanding of the different elements of HS pain, and increased provider awareness of the disease, the future of pain management in patients with HS seems promising.

Acute and Perioperative Pain Management

Acute Pain Management—The pain in HS can range from mild to excruciating.3,7 The difference between acute and chronic pain in this condition may be hard to delineate, as patients may have intense acute flares on top of a baseline level of chronic pain.3,7,14 These factors, in combination with various pain types of differing etiologies, make the treatment of HS-associated pain a therapeutic challenge.

The first-line treatments for acute pain in HS are oral acetaminophen, oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and topical analgesics.3 These treatment modalities are especially helpful for nociceptive pain, which often is described as having an aching or tender quality.3 Topical treatment for acute pain episodes includes diclofenac gel and liposomal lidocaine cream.39 Topical lidocaine in particular has the benefit of being rapid acting, and its effect can last 1 to 2 hours. Ketamine has been anecdotally used as a topical treatment. Treatment options for neuropathic pain include topical amitriptyline, gabapentin, and pregabalin.39 Dressings and ice packs may be used in cases of mild acute pain, depending on patient preference.3

First-line therapies may not provide adequate pain control in many patients.3,40,41 Should the first-line treatments fail, oral opiates can be considered as a treatment option, especially if the patient has a history of recurrent pain unresponsive to milder methods of pain control.3,40,41 However, prudence should be exercised, as patients with HS have a higher risk for opioid abuse, and referral to a pain specialist is advisable.40 Generally, use of opioids should be limited to the smallest period of time possible.40,41 Codeine can be used as a first opioid option, with hydromorphone available as an alternative.41

Pain caused by inflamed abscesses and nodules can be treated with either intralesional corticosteroids or incision and drainage. Intralesional triamcinolone has been found to cause substantial pain relief within 1 day of injection in patients with HS.3,42

Prompt discussion about the remitting course of HS will prepare patients for flares. Although the therapies discussed here aim to reduce the clinical severity and inflammation associated with HS, achieving pain-free remission can be challenging. Barriers to developing a long-term treatment regimen include intolerable side effects or simply nonresponsive disease.36,43

Management of Perioperative Pain—Medical treatment of HS often yields only transient or mild results. Hurley stage II or III lesions typically require surgical removal of affected tissues.32,44-46 Surgery may dramatically reduce the primary disease burden and provide substantial pain relief.3,4,44 Complete resection of the affected tissue by wide excision is the most common surgical procedure used.46-48 However, various tissue-sparing techniques, such as skin-tissue-sparing excision with electrosurgical peeling, also have been utilized. Tissue-sparing surgical techniques may lead to shorter healing times and less postoperative pain.48

There currently is little guidance available on the perioperative management of pain as it relates to surgical procedures for HS. The pain experienced from surgery varies based on the area and location of affected tissue; extent of disease; surgical technique used; and whether primary closure, closure by secondary intention, or skin grafting is utilized.47,49 Medical treatment aimed at reducing inflammation prior to surgical intervention may improve postoperative pain and complications.

The use of general vs local anesthesia during surgery depends on the extent of the disease and the amount of tissue being removed; however, the use of local anesthesia has been associated with a higher recurrence of disease, possibly owing to less aggressive tissue removal.50 Intraoperatively, the injection of 0.5% bupivacaine around the wound edges may lead to less postoperative pain.3,48 Postoperative pain usually is managed with acetaminophen and NSAIDs.48 In cases of severe postoperative pain, short- and long-acting opioid oxycodone preparations may be used. The combination of diclofenac and tramadol also has been used postoperatively.3 Patients who do not undergo extensive surgery often can leave the hospital the same day.

Effective strategies for mitigating HS-associated pain must address the chronic pain component of the disease. Long-term management involves lifestyle modifications and pharmacologic agents.

Chronic Pain Management

Although HS is not a curable disease, there are treatments available to minimize symptoms. Long-term management of HS is essential to minimize the effects of chronic pain and physical scarring associated with inflammation.31 In one study from the French Society of Dermatology, pain reported by patients with HS was directly associated with severity and duration of disease, emotional symptoms, and reduced functionality.51 For these reasons, many treatments for HS target reducing clinical severity and achieving remission, often defined as more than 6 months without any recurrence of lesions.52 In addition to lifestyle management, therapies available to manage HS include topical and systemic medications as well as procedures such as surgical excision.36,43,52,53

Lifestyle Modifications

Regardless of the severity of HS, all patients may benefit from basic education on the pathogenesis of the disease.36 The associations with smoking and obesity have been well documented, and treatment of these comorbid conditions is indicated.36,43,52 For example, in relation to obesity, the use of metformin is very well tolerated and seems to positively impact HS symptoms.43 Several studies have suggested that weight reduction lowers disease severity.28-30 Patients should be counseled on the importance of smoking cessation and weight loss.

Finally, the emotional impact of HS is not to be discounted, both the physical and social discomfort as well as the chronicity of the disease and frustration with treatment.51 Chronic pain has been associated with increased rates of depression, and 43% of patients with HS specifically have been diagnosed with major depressive disorder.7 For these reasons, clinician guidance, social support, and websites can improve patient understanding of the disease, adherence to treatment, and comorbid anxiety and depression.52

Topical Therapy

Topical therapy generally is limited to mild disease and is geared at decreasing inflammation or superimposed infection.36,52 Some of the earliest therapies used were topical antibiotics.43 Topical clindamycin has been shown to be as effective as oral tetracyclines in reducing the number of abscesses, but neither treatment substantially reduces pain associated with smaller nodules.54 Intralesional corticosteroids such as triamcinolone acetonide have been shown to decrease both patient-reported pain and physician-assessed severity within 1 to 7 days.42 Routine injection, however, is not a feasible means of long-term treatment both because of inconvenience and the potential adverse effects of corticosteroids.36,52 Both topical clindamycin and intralesional steroids are helpful in reducing inflammation prior to planned surgical intervention.36,52,53

Newer topical therapies include resorcinol peels and combination antimicrobials, such as 2% triclosan and oral zinc gluconate.52,53 Data surrounding the use of resorcinol in mild to moderate HS are promising and have shown decreased severity of both new and long-standing nodules. Fifteen-percent resorcinol peels are helpful tools that allow for self-administration by patients during exacerbations to decrease pain and flare duration.55,56 In a 2016 clinical trial, a combination of oral zinc gluconate with topical triclosan was shown to reduce flare-ups and nodules in mild HS.57 Oral zinc alone may have anti-inflammatory properties and generally is well tolerated.43,53 Topical therapies have a role in reducing HS-associated pain but often are limited to milder disease.

Systemic Agents

Several therapeutic options exist for the treatment of HS; however, a detailed description of their mechanisms and efficacies is beyond the scope of this review, which is focused on pain. Briefly, these systemic agents include antibiotics, retinoids, corticosteroids, antiandrogens, and biologics.43,52,53

Treatment with antibiotics such as tetracyclines or a combination of clindamycin plus rifampin has been shown to produce complete remission in 60% to 80% of users; however, this treatment requires more than 6 months of antibiotic therapy, which can be difficult to tolerate.52,53,58 Relapse is common after antibiotic cessation.2,43,52 Antibiotics have demonstrated efficacy during acute flares and in reducing inflammatory activity prior to surgery.52

Retinoids have been utilized in the treatment of HS because of their action on sebaceous glands and hair follicles.43,53 Acitretin has been shown to be the most effective oral retinoid available in the United States.43 Unfortunately, many of the studies investigating the use of retinoids for treatment of HS are limited by small sample size.36,43,52

Because HS is predominantly an inflammatory condition, immunosuppressants have been adapted to manage patients when antibiotics and topicals have failed. Systemic steroids rarely are used for long-term therapy because of the severe side effects and are preferred only for acute management.36,52 Cyclosporine and dapsone have demonstrated efficacy in treating moderate to severe HS, whereas methotrexate and colchicine have shown little efficacy.52 Both cyclosporine and dapsone are difficult to tolerate, require laboratory monitoring, and lead to only conservative improvement rather than remission in most patients.43

Immune dysregulation in HS involves elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), which is a key mediator of inflammation and a stimulator of other inflammatory cytokines.59,60 The first approved biologic treatment of HS was adalimumab, a TNF-α inhibitor, which showed a 50% reduction in total abscess and inflammatory nodule count in 60% of patients with moderate to severe HS.61-63 Of course, TNF-α inhibitor therapy is not without risks, specifically those of infection.43,53,61,62 Maintenance therapy may be required if patients relapse.53,61

Various interleukin inhibitors also have emerged as potential therapies for HS, such as ustekinumab and anakinra.36,64 Both have been subject to numerous small case trials that have reported improvements in clinical severity and pain; however, both drugs were associated with a fair number of nonresponders.36,64,65

Surgical Procedures

Although HS lesions may regress on their own in a matter of weeks, surgical drainage allows an acute alleviation of the severe burning pain associated with HS flares.36,52,53 Because of improved understanding of the disease pathophysiology, recent therapies targeting the hair follicle have been developed and have shown promising results. These therapies include laser- and light-based procedures. Long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser therapy reduces the number of hair follicles and sebaceous glands and has been effective for Hurley stage I or II disease.36,43,52,53,66 Photodynamic therapy offers a less-invasive option compared to surgery and laser therapy.52,53,66 Both Nd:YAG and CO2 laser therapy offer low recurrence rates (<30%) due to destruction of the apocrine unit.43,53 Photodynamic therapy for mild disease offers a less-invasive option compared to surgery and laser therapy.53 There is a need for larger randomized controlled trials involving laser, light, and CO2 therapies.66

Conclusion

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a debilitating condition with an underestimated disease burden. Although the pathophysiology of the disease is not completely understood, it is evident that pain is a major cause of morbidity. Patients experience a multitude of acute and chronic pain types: inflammatory, noninflammatory, nociceptive, neuropathic, and ischemic. Pain perception and quality of life are further impacted by psychiatric conditions such as depression and anxiety, both of which are common comorbidities in patients with HS. Several pharmacologic agents have been used to treat HS-associated pain with mixed results. First-line treatment of acute pain episodes includes oral acetaminophen, NSAIDs, and topical analgesics. Management of chronic pain includes utilization of topical agents, systemic agents, and biologics, as well as addressing lifestyle (eg, obesity, smoking status) and psychiatric comorbidities. Although these therapies have roles in HS pain management, the most effective pain remedies developed thus far are limited to surgery and TNF-α inhibitors. Optimization of pain control in patients with HS requires multidisciplinary collaboration among dermatologists, pain specialists, psychiatrists, and other members of the health care team. Further large-scale studies are needed to create an evidence-based treatment algorithm for the management of pain in HS.

- Napolitano M, Megna M, Timoshchuk EA, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: from pathogenesis to diagnosis and treatment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:105-115. doi:10.2147/CCID.S111019

- Revuz J. Hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol. 2009;23:985-998. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03356.x

- Horváth B, Janse IC, Sibbald GR. Pain management in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5 suppl 1):S47-S51. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.046

- Puza CJ, Wolfe SA, Jaleel T. Pain management in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa requiring surgery. Dermatolog Surg. 2019;45:1327-1330. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001693

- Kurzen H, Kurokawa I, Jemec GBE, et al. What causes hidradenitis suppurativa? Exp Dermatol. 2008;17:455-456. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00712_1.x

- Kelly G, Sweeney CM, Tobin AM, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: the role of immune dysregulation. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1186-1196. doi:10.1111/ijd.12550

- Patel ZS, Hoffman LK, Buse DC, et al. Pain, psychological comorbidities, disability, and impaired quality of life in hidradenitis suppurativa. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2017;21:49. doi:10.1007/s11916-017-0647-3

- Sist TC, Florio GA, Miner MF, et al. The relationship between depression and pain language in cancer and chronic non-cancer pain patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1998;15:350-358. doi:10.1016/S0885-3924(98)00006-2

- Jemec GBE. Hidradenitis suppurativa. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:158-164. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1014163

- Nielsen RM, Lindsø Andersen P, Sigsgaard V, et al. Pain perception in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2019;182:bjd.17935. doi:10.1111/bjd.17935

- Tanabe P, Myers R, Zosel A, et al. Emergency department management of acute pain episodes in sickle cell disease. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:419-425. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2006.11.033

- Chou R, Loeser JD, Owens DK, et al. Interventional therapies, surgery, and interdisciplinary rehabilitation for low back pain: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:1066-1077. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a1390d

- Enamandram M, Rathmell JP, Kimball AB. Chronic pain management in dermatology: a guide to assessment and nonopioid pharmacotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:563-573; quiz 573-574. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.11.039

- Jemec GBE, Kimball AB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology and scope of the problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5 suppl 1):S4-S7. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.052

- Vinkel C, Thomsen SF. Hidradenitis suppurativa: causes, features, and current treatments. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:17-23.

- Patil S, Apurwa A, Nadkarni N, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: inside and out. Indian J Dermatol. 2018;63:91-98. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_412_16

- Woodruff CM, Charlie AM, Leslie KS. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a guide for the practicing physician. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:1679-1693. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.020

- Pink AE, Simpson MA, Desai N, et al. Mutations in the γ-secretase genes NCSTN, PSENEN, and PSEN1 underlie rare forms of hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa). J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:2459-2461. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.162

- Jemec GBE, Heidenheim M, Nielsen NH. The prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa and its potential precursor lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:191-194. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90321-7

- Fitzsimmons JS, Guilbert PR. A family study of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Med Genet. 1985;22:367-373. doi:10.1136/jmg.22.5.367

- Kelly G, Prens EP. Inflammatory mechanisms in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:51-58. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.08.004

- Yazdanyar S, Jemec GB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a review of cause and treatment. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:118-123. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283428d07

- Kathju S, Lasko LA, Stoodley P. Considering hidradenitis suppurativa as a bacterial biofilm disease. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2012;65:385-389. doi:10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.00946.x

- Jahns AC, Killasli H, Nosek D, et al. Microbiology of hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa): a histological study of 27 patients. APMIS. 2014;122:804-809. doi:10.1111/apm.12220

- Ralf Paus L, Kurzen H, Kurokawa I, et al. What causes hidradenitis suppurativa? Exp Dermatol. 2008;17:455-456. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00712_1.x

- Vazquez BG, Alikhan A, Weaver AL, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa and associated factors: a population-based study of Olmsted County, Minnesota. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:97-103. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.255

- Kromann CB, Ibler KS, Kristiansen VB, et al. The influence of body weight on the prevalence and severity of hidradenitis suppurativa. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:553-557. doi:10.2340/00015555-1800

- Lindsø Andersen P, Kromann C, Fonvig CE, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa in a cohort of overweight and obese children and adolescents. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:47-51. doi:10.1111/ijd.14639

- Revuz JE, Canoui-Poitrine F, Wolkenstein P, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with hidradenitis suppurativa: results from two case-control studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:596-601. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.06.020

- Kromann CB, Deckers IE, Esmann S, et al. Risk factors, clinical course and long-term prognosis in hidradenitis suppurativa: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:819-824. doi:10.1111/bjd.13090

- Wieczorek M, Walecka I. Hidradenitis suppurativa—known and unknown disease. Reumatologia. 2018;56:337-339. doi:10.5114/reum.2018.80709

- Hsiao J, Leslie K, McMichael A, et al. Folliculitis and other follicular disorders. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:615-632.

- Scheinfeld N. Treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa associated pain with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, celecoxib, gapapentin, pegabalin, duloxetine, and venlafaxine. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20616.

- Scheinfeld N. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a practical review of possible medical treatments based on over 350 hidradenitis patients. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:1.

- Rajmohan V, Suresh Kumar S. Psychiatric morbidity, pain perception, and functional status of chronic pain patients in palliative care. Indian J Palliat Care. 2013;19:146-151. doi:10.4103/0973-1075.121527

- Saunte DML, Jemec GBE. Hidradenitis suppurativa: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2017;318:2019-2032. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.16691

- Wang B, Yang W, Wen W, et al. Gamma-secretase gene mutations in familial acne inversa. Science. 2010;330:1065. doi:10.1126/science.1196284

- Thorlacius L, Ingram JR, Villumsen B, et al. A core domain set for hidradenitis suppurativa trial outcomes: an international Delphi process. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:642-650. doi:10.1111/bjd.16672

- Scheinfeld N. Topical treatments of skin pain: a general review with a focus on hidradenitis suppurativa with topical agents. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030/qt4m57506k.

- Reddy S, Orenstein LAV, Strunk A, et al. Incidence of long-term opioid use among opioid-naive patients with hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1284-1290. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.2610

- Zouboulis CC, Desai N, Emtestam L, et al. European S1 guideline for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol. 2015;29:619-644. doi:10.1111/jdv.12966

- Riis PT, Boer J, Prens EP, et al. Intralesional triamcinolone for flares of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): a case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1151-1155. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.06.049

- Robert E, Bodin F, Paul C, et al. Non-surgical treatments for hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2017;62:274-294. doi:10.1016/j.anplas.2017.03.012

- Menderes A, Sunay O, Vayvada H, et al. Surgical management of hidradenitis suppurativa. Int J Med Sci. 2010;7:240-247. doi:10.7150/ijms.7.240

- Alharbi Z, Kauczok J, Pallua N. A review of wide surgical excision of hidradenitis suppurativa. BMC Dermatol. 2012;12:9. doi:10.1186/1471-5945-12-9

- Burney RE. 35-year experience with surgical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. World J Surg. 2017;41:2723-2730. doi:10.1007/s00268-017-4091-7

- Bocchini SF, Habr-Gama A, Kiss DR, et al. Gluteal and perianal hidradenitis suppurativa: surgical treatment by wide excision. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:944-949. doi:10.1007/s10350-004-6691-1

- Blok JL, Spoo JR, Leeman FWJ, et al. Skin-tissue-sparing excision with electrosurgical peeling (STEEP): a surgical treatment option for severe hidradenitis suppurativa Hurley stage II/III. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:379-382. doi:10.1111/jdv.12376

- Bilali S, Todi V, Lila A, et al. Surgical treatment of chronic hidradenitis suppurativa in the gluteal and perianal regions. Acta Chir Iugosl. 2012;59:91-95. doi:10.2298/ACI1202091B

- Walter AC, Meissner M, Kaufmann R, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa after radical surgery-long-term follow-up for recurrences and associated factors. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1323-1331. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001668.

- Wolkenstein P, Loundou A, Barrau K, et al. Quality of life impairment in hidradenitis suppurativa: a study of 61 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:621-623. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.061

- Alavi A, Lynde C, Alhusayen R, et al. Approach to the management of patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a consensus document. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21:513-524. doi:10.1177/1203475417716117

- Duran C, Baumeister A. Recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Physician Assist. 2019;32:36-42. doi:10.1097/01.JAA.0000578768.62051.13

- Jemec GBE, Wendelboe P. Topical clindamycin versus systemic tetracycline in the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:971-974. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(98)70272-5

- Pascual JC, Encabo B, Ruiz de Apodaca RF, et al. Topical 15% resorcinol for hidradenitis suppurativa: an uncontrolled prospective trial with clinical and ultrasonographic follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:1175-1178. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.07.008

- Boer J, Jemec GBE. Resorcinol peels as a possible self-treatment of painful nodules in hidradenitis suppurativa. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:36-40. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03377.x

- Hessam S, Sand M, Meier NM, et al. Combination of oral zinc gluconate and topical triclosan: an anti-inflammatory treatment modality for initial hidradenitis suppurativa. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;84:197-202. doi:10.1016/j.jdermsci.2016.08.010

- Gener G, Canoui-Poitrine F, Revuz JE, et al. Combination therapy with clindamycin and rifampicin for hidradenitis suppurativa: a series of 116 consecutive patients. Dermatology. 2009;219:148-154. doi:10.1159/000228334

- Vossen ARJV, van der Zee HH, Prens EP. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review integrating inflammatory pathways into a cohesive pathogenic model. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2965. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02965

- Chu WM. Tumor necrosis factor. Cancer Lett. 2013;328:222-225. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2012.10.014

- Kimball AB, Okun MM, Williams DA, et al. Two phase 3 trials of adalimumab for hidradenitis suppurativa. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:422-434. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1504370

- Morita A, Takahashi H, Ozawa K, et al. Twenty-four-week interim analysis from a phase 3 open-label trial of adalimumab in Japanese patients with moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa. J Dermatol. 2019;46:745-751. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.14997

- Ghias MH, Johnston AD, Kutner AJ, et al. High-dose, high-frequency infliximab: a novel treatment paradigm for hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1094-1101. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.071

- Tzanetakou V, Kanni T, Giatrakou S, et al. Safety and efficacy of anakinra in severe hidradenitis suppurativa a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:52-59. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.3903

- Blok JL, Li K, Brodmerkel C, et al. Ustekinumab in hidradenitis suppurativa: clinical results and a search for potential biomarkers in serum. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:839-846. doi:10.1111/bjd.14338

- John H, Manoloudakis N, Stephen Sinclair J. A systematic review of the use of lasers for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69:1374-1381. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2016.05.029

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory, androgen gland disorder characterized by recurrent rupture of the hair follicles with a vigorous inflammatory response. This response results in abscess formation and development of draining sinus tracts and hypertrophic fibrous scars.1,2 Pain, discomfort, and odorous discharge from the recalcitrant lesions have a profound impact on patient quality of life.3,4

The morbidity and disease burden associated with HS are particularly underestimated, as patients frequently report debilitating pain that often is overlooked.5,6 Additionally, the quality and intensity of perceived pain are compounded by frequently associated depression and anxiety.7-9 Pain has been reported by patients with HS to be the highest cause of morbidity, despite the disfiguring nature of the disease and its associated psychosocial distress.7,10 Nonetheless, HS lacks an accepted pain management algorithm similar to those that have been developed for the treatment of other acute or chronic pain disorders, such as back pain and sickle cell disease.4,11-13

Given the lack of formal studies regarding pain management in patients with HS, clinicians are limited to general pain guidelines, expert opinion, small trials, and patient preference.3 Furthermore, effective pain management in HS necessitates the treatment of both chronic pain affecting daily function and acute pain present during disease flares, surgical interventions, and dressing changes.3 The result is a wide array of strategies used for HS-associated pain.3,4

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Hidradenitis suppurativa historically has been an overlooked and underdiagnosed disease, which limits epidemiology data.5 Current estimates are that HS affects approximately 1% of the general population; however, prevalence rates range from 0.03% to 4.1%.14-16

The exact etiology of HS remains unclear, but it is thought that genetic factors, immune dysregulation, and environmental/behavioral influences all contribute to its pathophysiology.1,17 Up to 40% of patients with HS report a positive family history of the disease.18-20 Hidradenitis suppurativa has been associated with other inflammatory disease states, such as inflammatory bowel disease, spondyloarthropathies, and pyoderma gangrenosum.16,21,22

It is thought that HS is the result of some defect in keratin clearance that leads to follicular hyperkeratinization and occlusion.1 Resultant rupture of pilosebaceous units and spillage of contents (including keratin and bacteria) into the surrounding dermis triggers a vigorous inflammatory response. Sinus tracts and fistulas become the targets of bacterial colonization, biofilm formation, and secondary infection. The result is suppuration and extension of the lesions as well as sustained chronic inflammation.23,24

Although the etiology of HS is complex, several modifiable risk factors for the disease have been identified, most prominently cigarette smoking and obesity. Approximately 70% of patients with HS smoke cigarettes.2,15,25,26 Obesity has a well-known association with HS, and it is possible that weight reduction lowers disease severity.27-30

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Establishing a diagnosis of HS necessitates recognition of disease morphology, topography, and chronicity. Hidradenitis suppurativa most commonly occurs in the axillae, inguinal and anogenital region, perineal region, and inframammary region.5,31 A typical history involves a prolonged disease course with recurrent lesions and intermittent periods of improvement or remission. Primary lesions are deep, inflamed, painful, and sterile. Ultimately, these lesions rupture and track subcutaneously.15,25 Intercommunicating sinus tracts form from multiple recurrent nodules in close proximity and may ultimately lead to fibrotic scarring and local architectural distortion.32 The Hurley staging system helps to guide treatment interventions based on disease severity. Approach to pain management is discussed below.

Pain Management in HS: General Principles

Pain management is complex for clinicians, as there are limited studies from which to draw treatment recommendations. Incomplete understanding of the etiology and pathophysiology of the disease contributes to the lack of established management guidelines.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms hidradenitis, suppurativa, pain, and management revealed 61 different results dating back to 1980, 52 of which had been published in the last 5 years. When the word acute was added to the search, there were only 6 results identified. These results clearly reflect a better understanding of HS-mediated pain as well as clinical unmet needs and evolving strategies in pain management therapeutics. However, many of these studies reflect therapies focused on the mediation or modulation of HS pathogenesis rather than potential pain management therapies.

In addition, the heterogenous nature of the pain experience in HS poses a challenge for clinicians. Patients may experience multiple pain types concurrently, including inflammatory, noninflammatory, nociceptive, neuropathic, and ischemic, as well as pain related to arthritis.3,33,34 Pain perception is further complicated by the observation that patients with HS have high rates of psychiatric comorbidities such as depression and anxiety, both of which profoundly alter perception of both the strength and quality of pain.7,8,22,35 A suggested algorithm for treatment of pain in HS is described in the eTable.36

Chronicity is a hallmark of HS. Patients experience a prolonged disease course involving acute painful exacerbations superimposed on chronic pain that affects all aspects of daily life. Changes in self-perception, daily living activities, mood state, physical functioning, and physical comfort frequently are reported to have a major impact on quality of life.1,3,37

In 2018, Thorlacius et al38 created a multistakeholder consensus on a core outcome set of domains detailing what to measure in clinical trials for HS. The authors hoped that the routine adoption of these core domains would promote the collection of consistent and relevant information, bolster the strength of evidence synthesis, and minimize the risk for outcome reporting bias among studies.38 It is important to ascertain the patient’s description of his/her pain to distinguish between stimulus-dependent nociceptive pain vs spontaneous neuropathic pain.3,7,10 The most common pain descriptors used by patients are “shooting,” “itchy,” “blinding,” “cutting,” and “exhausting.”10 In addition to obtaining descriptive factors, it is important for the clinician to obtain information on the timing of the pain, whether or not the pain is relieved with spontaneous or surgical drainage, and if the patient is experiencing chronic background pain secondary to scarring or skin contraction.3 With the routine utilization of a consistent set of core domains, advances in our understanding of the different elements of HS pain, and increased provider awareness of the disease, the future of pain management in patients with HS seems promising.

Acute and Perioperative Pain Management

Acute Pain Management—The pain in HS can range from mild to excruciating.3,7 The difference between acute and chronic pain in this condition may be hard to delineate, as patients may have intense acute flares on top of a baseline level of chronic pain.3,7,14 These factors, in combination with various pain types of differing etiologies, make the treatment of HS-associated pain a therapeutic challenge.

The first-line treatments for acute pain in HS are oral acetaminophen, oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and topical analgesics.3 These treatment modalities are especially helpful for nociceptive pain, which often is described as having an aching or tender quality.3 Topical treatment for acute pain episodes includes diclofenac gel and liposomal lidocaine cream.39 Topical lidocaine in particular has the benefit of being rapid acting, and its effect can last 1 to 2 hours. Ketamine has been anecdotally used as a topical treatment. Treatment options for neuropathic pain include topical amitriptyline, gabapentin, and pregabalin.39 Dressings and ice packs may be used in cases of mild acute pain, depending on patient preference.3

First-line therapies may not provide adequate pain control in many patients.3,40,41 Should the first-line treatments fail, oral opiates can be considered as a treatment option, especially if the patient has a history of recurrent pain unresponsive to milder methods of pain control.3,40,41 However, prudence should be exercised, as patients with HS have a higher risk for opioid abuse, and referral to a pain specialist is advisable.40 Generally, use of opioids should be limited to the smallest period of time possible.40,41 Codeine can be used as a first opioid option, with hydromorphone available as an alternative.41

Pain caused by inflamed abscesses and nodules can be treated with either intralesional corticosteroids or incision and drainage. Intralesional triamcinolone has been found to cause substantial pain relief within 1 day of injection in patients with HS.3,42

Prompt discussion about the remitting course of HS will prepare patients for flares. Although the therapies discussed here aim to reduce the clinical severity and inflammation associated with HS, achieving pain-free remission can be challenging. Barriers to developing a long-term treatment regimen include intolerable side effects or simply nonresponsive disease.36,43

Management of Perioperative Pain—Medical treatment of HS often yields only transient or mild results. Hurley stage II or III lesions typically require surgical removal of affected tissues.32,44-46 Surgery may dramatically reduce the primary disease burden and provide substantial pain relief.3,4,44 Complete resection of the affected tissue by wide excision is the most common surgical procedure used.46-48 However, various tissue-sparing techniques, such as skin-tissue-sparing excision with electrosurgical peeling, also have been utilized. Tissue-sparing surgical techniques may lead to shorter healing times and less postoperative pain.48

There currently is little guidance available on the perioperative management of pain as it relates to surgical procedures for HS. The pain experienced from surgery varies based on the area and location of affected tissue; extent of disease; surgical technique used; and whether primary closure, closure by secondary intention, or skin grafting is utilized.47,49 Medical treatment aimed at reducing inflammation prior to surgical intervention may improve postoperative pain and complications.

The use of general vs local anesthesia during surgery depends on the extent of the disease and the amount of tissue being removed; however, the use of local anesthesia has been associated with a higher recurrence of disease, possibly owing to less aggressive tissue removal.50 Intraoperatively, the injection of 0.5% bupivacaine around the wound edges may lead to less postoperative pain.3,48 Postoperative pain usually is managed with acetaminophen and NSAIDs.48 In cases of severe postoperative pain, short- and long-acting opioid oxycodone preparations may be used. The combination of diclofenac and tramadol also has been used postoperatively.3 Patients who do not undergo extensive surgery often can leave the hospital the same day.

Effective strategies for mitigating HS-associated pain must address the chronic pain component of the disease. Long-term management involves lifestyle modifications and pharmacologic agents.

Chronic Pain Management

Although HS is not a curable disease, there are treatments available to minimize symptoms. Long-term management of HS is essential to minimize the effects of chronic pain and physical scarring associated with inflammation.31 In one study from the French Society of Dermatology, pain reported by patients with HS was directly associated with severity and duration of disease, emotional symptoms, and reduced functionality.51 For these reasons, many treatments for HS target reducing clinical severity and achieving remission, often defined as more than 6 months without any recurrence of lesions.52 In addition to lifestyle management, therapies available to manage HS include topical and systemic medications as well as procedures such as surgical excision.36,43,52,53

Lifestyle Modifications

Regardless of the severity of HS, all patients may benefit from basic education on the pathogenesis of the disease.36 The associations with smoking and obesity have been well documented, and treatment of these comorbid conditions is indicated.36,43,52 For example, in relation to obesity, the use of metformin is very well tolerated and seems to positively impact HS symptoms.43 Several studies have suggested that weight reduction lowers disease severity.28-30 Patients should be counseled on the importance of smoking cessation and weight loss.

Finally, the emotional impact of HS is not to be discounted, both the physical and social discomfort as well as the chronicity of the disease and frustration with treatment.51 Chronic pain has been associated with increased rates of depression, and 43% of patients with HS specifically have been diagnosed with major depressive disorder.7 For these reasons, clinician guidance, social support, and websites can improve patient understanding of the disease, adherence to treatment, and comorbid anxiety and depression.52

Topical Therapy

Topical therapy generally is limited to mild disease and is geared at decreasing inflammation or superimposed infection.36,52 Some of the earliest therapies used were topical antibiotics.43 Topical clindamycin has been shown to be as effective as oral tetracyclines in reducing the number of abscesses, but neither treatment substantially reduces pain associated with smaller nodules.54 Intralesional corticosteroids such as triamcinolone acetonide have been shown to decrease both patient-reported pain and physician-assessed severity within 1 to 7 days.42 Routine injection, however, is not a feasible means of long-term treatment both because of inconvenience and the potential adverse effects of corticosteroids.36,52 Both topical clindamycin and intralesional steroids are helpful in reducing inflammation prior to planned surgical intervention.36,52,53

Newer topical therapies include resorcinol peels and combination antimicrobials, such as 2% triclosan and oral zinc gluconate.52,53 Data surrounding the use of resorcinol in mild to moderate HS are promising and have shown decreased severity of both new and long-standing nodules. Fifteen-percent resorcinol peels are helpful tools that allow for self-administration by patients during exacerbations to decrease pain and flare duration.55,56 In a 2016 clinical trial, a combination of oral zinc gluconate with topical triclosan was shown to reduce flare-ups and nodules in mild HS.57 Oral zinc alone may have anti-inflammatory properties and generally is well tolerated.43,53 Topical therapies have a role in reducing HS-associated pain but often are limited to milder disease.

Systemic Agents

Several therapeutic options exist for the treatment of HS; however, a detailed description of their mechanisms and efficacies is beyond the scope of this review, which is focused on pain. Briefly, these systemic agents include antibiotics, retinoids, corticosteroids, antiandrogens, and biologics.43,52,53

Treatment with antibiotics such as tetracyclines or a combination of clindamycin plus rifampin has been shown to produce complete remission in 60% to 80% of users; however, this treatment requires more than 6 months of antibiotic therapy, which can be difficult to tolerate.52,53,58 Relapse is common after antibiotic cessation.2,43,52 Antibiotics have demonstrated efficacy during acute flares and in reducing inflammatory activity prior to surgery.52

Retinoids have been utilized in the treatment of HS because of their action on sebaceous glands and hair follicles.43,53 Acitretin has been shown to be the most effective oral retinoid available in the United States.43 Unfortunately, many of the studies investigating the use of retinoids for treatment of HS are limited by small sample size.36,43,52

Because HS is predominantly an inflammatory condition, immunosuppressants have been adapted to manage patients when antibiotics and topicals have failed. Systemic steroids rarely are used for long-term therapy because of the severe side effects and are preferred only for acute management.36,52 Cyclosporine and dapsone have demonstrated efficacy in treating moderate to severe HS, whereas methotrexate and colchicine have shown little efficacy.52 Both cyclosporine and dapsone are difficult to tolerate, require laboratory monitoring, and lead to only conservative improvement rather than remission in most patients.43

Immune dysregulation in HS involves elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), which is a key mediator of inflammation and a stimulator of other inflammatory cytokines.59,60 The first approved biologic treatment of HS was adalimumab, a TNF-α inhibitor, which showed a 50% reduction in total abscess and inflammatory nodule count in 60% of patients with moderate to severe HS.61-63 Of course, TNF-α inhibitor therapy is not without risks, specifically those of infection.43,53,61,62 Maintenance therapy may be required if patients relapse.53,61

Various interleukin inhibitors also have emerged as potential therapies for HS, such as ustekinumab and anakinra.36,64 Both have been subject to numerous small case trials that have reported improvements in clinical severity and pain; however, both drugs were associated with a fair number of nonresponders.36,64,65

Surgical Procedures

Although HS lesions may regress on their own in a matter of weeks, surgical drainage allows an acute alleviation of the severe burning pain associated with HS flares.36,52,53 Because of improved understanding of the disease pathophysiology, recent therapies targeting the hair follicle have been developed and have shown promising results. These therapies include laser- and light-based procedures. Long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser therapy reduces the number of hair follicles and sebaceous glands and has been effective for Hurley stage I or II disease.36,43,52,53,66 Photodynamic therapy offers a less-invasive option compared to surgery and laser therapy.52,53,66 Both Nd:YAG and CO2 laser therapy offer low recurrence rates (<30%) due to destruction of the apocrine unit.43,53 Photodynamic therapy for mild disease offers a less-invasive option compared to surgery and laser therapy.53 There is a need for larger randomized controlled trials involving laser, light, and CO2 therapies.66

Conclusion

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a debilitating condition with an underestimated disease burden. Although the pathophysiology of the disease is not completely understood, it is evident that pain is a major cause of morbidity. Patients experience a multitude of acute and chronic pain types: inflammatory, noninflammatory, nociceptive, neuropathic, and ischemic. Pain perception and quality of life are further impacted by psychiatric conditions such as depression and anxiety, both of which are common comorbidities in patients with HS. Several pharmacologic agents have been used to treat HS-associated pain with mixed results. First-line treatment of acute pain episodes includes oral acetaminophen, NSAIDs, and topical analgesics. Management of chronic pain includes utilization of topical agents, systemic agents, and biologics, as well as addressing lifestyle (eg, obesity, smoking status) and psychiatric comorbidities. Although these therapies have roles in HS pain management, the most effective pain remedies developed thus far are limited to surgery and TNF-α inhibitors. Optimization of pain control in patients with HS requires multidisciplinary collaboration among dermatologists, pain specialists, psychiatrists, and other members of the health care team. Further large-scale studies are needed to create an evidence-based treatment algorithm for the management of pain in HS.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory, androgen gland disorder characterized by recurrent rupture of the hair follicles with a vigorous inflammatory response. This response results in abscess formation and development of draining sinus tracts and hypertrophic fibrous scars.1,2 Pain, discomfort, and odorous discharge from the recalcitrant lesions have a profound impact on patient quality of life.3,4

The morbidity and disease burden associated with HS are particularly underestimated, as patients frequently report debilitating pain that often is overlooked.5,6 Additionally, the quality and intensity of perceived pain are compounded by frequently associated depression and anxiety.7-9 Pain has been reported by patients with HS to be the highest cause of morbidity, despite the disfiguring nature of the disease and its associated psychosocial distress.7,10 Nonetheless, HS lacks an accepted pain management algorithm similar to those that have been developed for the treatment of other acute or chronic pain disorders, such as back pain and sickle cell disease.4,11-13

Given the lack of formal studies regarding pain management in patients with HS, clinicians are limited to general pain guidelines, expert opinion, small trials, and patient preference.3 Furthermore, effective pain management in HS necessitates the treatment of both chronic pain affecting daily function and acute pain present during disease flares, surgical interventions, and dressing changes.3 The result is a wide array of strategies used for HS-associated pain.3,4

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Hidradenitis suppurativa historically has been an overlooked and underdiagnosed disease, which limits epidemiology data.5 Current estimates are that HS affects approximately 1% of the general population; however, prevalence rates range from 0.03% to 4.1%.14-16

The exact etiology of HS remains unclear, but it is thought that genetic factors, immune dysregulation, and environmental/behavioral influences all contribute to its pathophysiology.1,17 Up to 40% of patients with HS report a positive family history of the disease.18-20 Hidradenitis suppurativa has been associated with other inflammatory disease states, such as inflammatory bowel disease, spondyloarthropathies, and pyoderma gangrenosum.16,21,22

It is thought that HS is the result of some defect in keratin clearance that leads to follicular hyperkeratinization and occlusion.1 Resultant rupture of pilosebaceous units and spillage of contents (including keratin and bacteria) into the surrounding dermis triggers a vigorous inflammatory response. Sinus tracts and fistulas become the targets of bacterial colonization, biofilm formation, and secondary infection. The result is suppuration and extension of the lesions as well as sustained chronic inflammation.23,24

Although the etiology of HS is complex, several modifiable risk factors for the disease have been identified, most prominently cigarette smoking and obesity. Approximately 70% of patients with HS smoke cigarettes.2,15,25,26 Obesity has a well-known association with HS, and it is possible that weight reduction lowers disease severity.27-30

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Establishing a diagnosis of HS necessitates recognition of disease morphology, topography, and chronicity. Hidradenitis suppurativa most commonly occurs in the axillae, inguinal and anogenital region, perineal region, and inframammary region.5,31 A typical history involves a prolonged disease course with recurrent lesions and intermittent periods of improvement or remission. Primary lesions are deep, inflamed, painful, and sterile. Ultimately, these lesions rupture and track subcutaneously.15,25 Intercommunicating sinus tracts form from multiple recurrent nodules in close proximity and may ultimately lead to fibrotic scarring and local architectural distortion.32 The Hurley staging system helps to guide treatment interventions based on disease severity. Approach to pain management is discussed below.

Pain Management in HS: General Principles

Pain management is complex for clinicians, as there are limited studies from which to draw treatment recommendations. Incomplete understanding of the etiology and pathophysiology of the disease contributes to the lack of established management guidelines.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms hidradenitis, suppurativa, pain, and management revealed 61 different results dating back to 1980, 52 of which had been published in the last 5 years. When the word acute was added to the search, there were only 6 results identified. These results clearly reflect a better understanding of HS-mediated pain as well as clinical unmet needs and evolving strategies in pain management therapeutics. However, many of these studies reflect therapies focused on the mediation or modulation of HS pathogenesis rather than potential pain management therapies.

In addition, the heterogenous nature of the pain experience in HS poses a challenge for clinicians. Patients may experience multiple pain types concurrently, including inflammatory, noninflammatory, nociceptive, neuropathic, and ischemic, as well as pain related to arthritis.3,33,34 Pain perception is further complicated by the observation that patients with HS have high rates of psychiatric comorbidities such as depression and anxiety, both of which profoundly alter perception of both the strength and quality of pain.7,8,22,35 A suggested algorithm for treatment of pain in HS is described in the eTable.36

Chronicity is a hallmark of HS. Patients experience a prolonged disease course involving acute painful exacerbations superimposed on chronic pain that affects all aspects of daily life. Changes in self-perception, daily living activities, mood state, physical functioning, and physical comfort frequently are reported to have a major impact on quality of life.1,3,37

In 2018, Thorlacius et al38 created a multistakeholder consensus on a core outcome set of domains detailing what to measure in clinical trials for HS. The authors hoped that the routine adoption of these core domains would promote the collection of consistent and relevant information, bolster the strength of evidence synthesis, and minimize the risk for outcome reporting bias among studies.38 It is important to ascertain the patient’s description of his/her pain to distinguish between stimulus-dependent nociceptive pain vs spontaneous neuropathic pain.3,7,10 The most common pain descriptors used by patients are “shooting,” “itchy,” “blinding,” “cutting,” and “exhausting.”10 In addition to obtaining descriptive factors, it is important for the clinician to obtain information on the timing of the pain, whether or not the pain is relieved with spontaneous or surgical drainage, and if the patient is experiencing chronic background pain secondary to scarring or skin contraction.3 With the routine utilization of a consistent set of core domains, advances in our understanding of the different elements of HS pain, and increased provider awareness of the disease, the future of pain management in patients with HS seems promising.

Acute and Perioperative Pain Management

Acute Pain Management—The pain in HS can range from mild to excruciating.3,7 The difference between acute and chronic pain in this condition may be hard to delineate, as patients may have intense acute flares on top of a baseline level of chronic pain.3,7,14 These factors, in combination with various pain types of differing etiologies, make the treatment of HS-associated pain a therapeutic challenge.

The first-line treatments for acute pain in HS are oral acetaminophen, oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and topical analgesics.3 These treatment modalities are especially helpful for nociceptive pain, which often is described as having an aching or tender quality.3 Topical treatment for acute pain episodes includes diclofenac gel and liposomal lidocaine cream.39 Topical lidocaine in particular has the benefit of being rapid acting, and its effect can last 1 to 2 hours. Ketamine has been anecdotally used as a topical treatment. Treatment options for neuropathic pain include topical amitriptyline, gabapentin, and pregabalin.39 Dressings and ice packs may be used in cases of mild acute pain, depending on patient preference.3

First-line therapies may not provide adequate pain control in many patients.3,40,41 Should the first-line treatments fail, oral opiates can be considered as a treatment option, especially if the patient has a history of recurrent pain unresponsive to milder methods of pain control.3,40,41 However, prudence should be exercised, as patients with HS have a higher risk for opioid abuse, and referral to a pain specialist is advisable.40 Generally, use of opioids should be limited to the smallest period of time possible.40,41 Codeine can be used as a first opioid option, with hydromorphone available as an alternative.41

Pain caused by inflamed abscesses and nodules can be treated with either intralesional corticosteroids or incision and drainage. Intralesional triamcinolone has been found to cause substantial pain relief within 1 day of injection in patients with HS.3,42

Prompt discussion about the remitting course of HS will prepare patients for flares. Although the therapies discussed here aim to reduce the clinical severity and inflammation associated with HS, achieving pain-free remission can be challenging. Barriers to developing a long-term treatment regimen include intolerable side effects or simply nonresponsive disease.36,43

Management of Perioperative Pain—Medical treatment of HS often yields only transient or mild results. Hurley stage II or III lesions typically require surgical removal of affected tissues.32,44-46 Surgery may dramatically reduce the primary disease burden and provide substantial pain relief.3,4,44 Complete resection of the affected tissue by wide excision is the most common surgical procedure used.46-48 However, various tissue-sparing techniques, such as skin-tissue-sparing excision with electrosurgical peeling, also have been utilized. Tissue-sparing surgical techniques may lead to shorter healing times and less postoperative pain.48

There currently is little guidance available on the perioperative management of pain as it relates to surgical procedures for HS. The pain experienced from surgery varies based on the area and location of affected tissue; extent of disease; surgical technique used; and whether primary closure, closure by secondary intention, or skin grafting is utilized.47,49 Medical treatment aimed at reducing inflammation prior to surgical intervention may improve postoperative pain and complications.

The use of general vs local anesthesia during surgery depends on the extent of the disease and the amount of tissue being removed; however, the use of local anesthesia has been associated with a higher recurrence of disease, possibly owing to less aggressive tissue removal.50 Intraoperatively, the injection of 0.5% bupivacaine around the wound edges may lead to less postoperative pain.3,48 Postoperative pain usually is managed with acetaminophen and NSAIDs.48 In cases of severe postoperative pain, short- and long-acting opioid oxycodone preparations may be used. The combination of diclofenac and tramadol also has been used postoperatively.3 Patients who do not undergo extensive surgery often can leave the hospital the same day.

Effective strategies for mitigating HS-associated pain must address the chronic pain component of the disease. Long-term management involves lifestyle modifications and pharmacologic agents.

Chronic Pain Management

Although HS is not a curable disease, there are treatments available to minimize symptoms. Long-term management of HS is essential to minimize the effects of chronic pain and physical scarring associated with inflammation.31 In one study from the French Society of Dermatology, pain reported by patients with HS was directly associated with severity and duration of disease, emotional symptoms, and reduced functionality.51 For these reasons, many treatments for HS target reducing clinical severity and achieving remission, often defined as more than 6 months without any recurrence of lesions.52 In addition to lifestyle management, therapies available to manage HS include topical and systemic medications as well as procedures such as surgical excision.36,43,52,53

Lifestyle Modifications

Regardless of the severity of HS, all patients may benefit from basic education on the pathogenesis of the disease.36 The associations with smoking and obesity have been well documented, and treatment of these comorbid conditions is indicated.36,43,52 For example, in relation to obesity, the use of metformin is very well tolerated and seems to positively impact HS symptoms.43 Several studies have suggested that weight reduction lowers disease severity.28-30 Patients should be counseled on the importance of smoking cessation and weight loss.

Finally, the emotional impact of HS is not to be discounted, both the physical and social discomfort as well as the chronicity of the disease and frustration with treatment.51 Chronic pain has been associated with increased rates of depression, and 43% of patients with HS specifically have been diagnosed with major depressive disorder.7 For these reasons, clinician guidance, social support, and websites can improve patient understanding of the disease, adherence to treatment, and comorbid anxiety and depression.52

Topical Therapy

Topical therapy generally is limited to mild disease and is geared at decreasing inflammation or superimposed infection.36,52 Some of the earliest therapies used were topical antibiotics.43 Topical clindamycin has been shown to be as effective as oral tetracyclines in reducing the number of abscesses, but neither treatment substantially reduces pain associated with smaller nodules.54 Intralesional corticosteroids such as triamcinolone acetonide have been shown to decrease both patient-reported pain and physician-assessed severity within 1 to 7 days.42 Routine injection, however, is not a feasible means of long-term treatment both because of inconvenience and the potential adverse effects of corticosteroids.36,52 Both topical clindamycin and intralesional steroids are helpful in reducing inflammation prior to planned surgical intervention.36,52,53

Newer topical therapies include resorcinol peels and combination antimicrobials, such as 2% triclosan and oral zinc gluconate.52,53 Data surrounding the use of resorcinol in mild to moderate HS are promising and have shown decreased severity of both new and long-standing nodules. Fifteen-percent resorcinol peels are helpful tools that allow for self-administration by patients during exacerbations to decrease pain and flare duration.55,56 In a 2016 clinical trial, a combination of oral zinc gluconate with topical triclosan was shown to reduce flare-ups and nodules in mild HS.57 Oral zinc alone may have anti-inflammatory properties and generally is well tolerated.43,53 Topical therapies have a role in reducing HS-associated pain but often are limited to milder disease.

Systemic Agents

Several therapeutic options exist for the treatment of HS; however, a detailed description of their mechanisms and efficacies is beyond the scope of this review, which is focused on pain. Briefly, these systemic agents include antibiotics, retinoids, corticosteroids, antiandrogens, and biologics.43,52,53

Treatment with antibiotics such as tetracyclines or a combination of clindamycin plus rifampin has been shown to produce complete remission in 60% to 80% of users; however, this treatment requires more than 6 months of antibiotic therapy, which can be difficult to tolerate.52,53,58 Relapse is common after antibiotic cessation.2,43,52 Antibiotics have demonstrated efficacy during acute flares and in reducing inflammatory activity prior to surgery.52

Retinoids have been utilized in the treatment of HS because of their action on sebaceous glands and hair follicles.43,53 Acitretin has been shown to be the most effective oral retinoid available in the United States.43 Unfortunately, many of the studies investigating the use of retinoids for treatment of HS are limited by small sample size.36,43,52

Because HS is predominantly an inflammatory condition, immunosuppressants have been adapted to manage patients when antibiotics and topicals have failed. Systemic steroids rarely are used for long-term therapy because of the severe side effects and are preferred only for acute management.36,52 Cyclosporine and dapsone have demonstrated efficacy in treating moderate to severe HS, whereas methotrexate and colchicine have shown little efficacy.52 Both cyclosporine and dapsone are difficult to tolerate, require laboratory monitoring, and lead to only conservative improvement rather than remission in most patients.43

Immune dysregulation in HS involves elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), which is a key mediator of inflammation and a stimulator of other inflammatory cytokines.59,60 The first approved biologic treatment of HS was adalimumab, a TNF-α inhibitor, which showed a 50% reduction in total abscess and inflammatory nodule count in 60% of patients with moderate to severe HS.61-63 Of course, TNF-α inhibitor therapy is not without risks, specifically those of infection.43,53,61,62 Maintenance therapy may be required if patients relapse.53,61

Various interleukin inhibitors also have emerged as potential therapies for HS, such as ustekinumab and anakinra.36,64 Both have been subject to numerous small case trials that have reported improvements in clinical severity and pain; however, both drugs were associated with a fair number of nonresponders.36,64,65

Surgical Procedures

Although HS lesions may regress on their own in a matter of weeks, surgical drainage allows an acute alleviation of the severe burning pain associated with HS flares.36,52,53 Because of improved understanding of the disease pathophysiology, recent therapies targeting the hair follicle have been developed and have shown promising results. These therapies include laser- and light-based procedures. Long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser therapy reduces the number of hair follicles and sebaceous glands and has been effective for Hurley stage I or II disease.36,43,52,53,66 Photodynamic therapy offers a less-invasive option compared to surgery and laser therapy.52,53,66 Both Nd:YAG and CO2 laser therapy offer low recurrence rates (<30%) due to destruction of the apocrine unit.43,53 Photodynamic therapy for mild disease offers a less-invasive option compared to surgery and laser therapy.53 There is a need for larger randomized controlled trials involving laser, light, and CO2 therapies.66

Conclusion

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a debilitating condition with an underestimated disease burden. Although the pathophysiology of the disease is not completely understood, it is evident that pain is a major cause of morbidity. Patients experience a multitude of acute and chronic pain types: inflammatory, noninflammatory, nociceptive, neuropathic, and ischemic. Pain perception and quality of life are further impacted by psychiatric conditions such as depression and anxiety, both of which are common comorbidities in patients with HS. Several pharmacologic agents have been used to treat HS-associated pain with mixed results. First-line treatment of acute pain episodes includes oral acetaminophen, NSAIDs, and topical analgesics. Management of chronic pain includes utilization of topical agents, systemic agents, and biologics, as well as addressing lifestyle (eg, obesity, smoking status) and psychiatric comorbidities. Although these therapies have roles in HS pain management, the most effective pain remedies developed thus far are limited to surgery and TNF-α inhibitors. Optimization of pain control in patients with HS requires multidisciplinary collaboration among dermatologists, pain specialists, psychiatrists, and other members of the health care team. Further large-scale studies are needed to create an evidence-based treatment algorithm for the management of pain in HS.

- Napolitano M, Megna M, Timoshchuk EA, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: from pathogenesis to diagnosis and treatment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:105-115. doi:10.2147/CCID.S111019

- Revuz J. Hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol. 2009;23:985-998. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03356.x

- Horváth B, Janse IC, Sibbald GR. Pain management in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5 suppl 1):S47-S51. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.046

- Puza CJ, Wolfe SA, Jaleel T. Pain management in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa requiring surgery. Dermatolog Surg. 2019;45:1327-1330. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001693

- Kurzen H, Kurokawa I, Jemec GBE, et al. What causes hidradenitis suppurativa? Exp Dermatol. 2008;17:455-456. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00712_1.x

- Kelly G, Sweeney CM, Tobin AM, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: the role of immune dysregulation. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1186-1196. doi:10.1111/ijd.12550

- Patel ZS, Hoffman LK, Buse DC, et al. Pain, psychological comorbidities, disability, and impaired quality of life in hidradenitis suppurativa. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2017;21:49. doi:10.1007/s11916-017-0647-3

- Sist TC, Florio GA, Miner MF, et al. The relationship between depression and pain language in cancer and chronic non-cancer pain patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1998;15:350-358. doi:10.1016/S0885-3924(98)00006-2

- Jemec GBE. Hidradenitis suppurativa. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:158-164. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1014163

- Nielsen RM, Lindsø Andersen P, Sigsgaard V, et al. Pain perception in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2019;182:bjd.17935. doi:10.1111/bjd.17935

- Tanabe P, Myers R, Zosel A, et al. Emergency department management of acute pain episodes in sickle cell disease. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:419-425. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2006.11.033

- Chou R, Loeser JD, Owens DK, et al. Interventional therapies, surgery, and interdisciplinary rehabilitation for low back pain: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:1066-1077. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a1390d

- Enamandram M, Rathmell JP, Kimball AB. Chronic pain management in dermatology: a guide to assessment and nonopioid pharmacotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:563-573; quiz 573-574. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.11.039

- Jemec GBE, Kimball AB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology and scope of the problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5 suppl 1):S4-S7. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.052

- Vinkel C, Thomsen SF. Hidradenitis suppurativa: causes, features, and current treatments. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:17-23.

- Patil S, Apurwa A, Nadkarni N, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: inside and out. Indian J Dermatol. 2018;63:91-98. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_412_16

- Woodruff CM, Charlie AM, Leslie KS. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a guide for the practicing physician. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:1679-1693. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.020

- Pink AE, Simpson MA, Desai N, et al. Mutations in the γ-secretase genes NCSTN, PSENEN, and PSEN1 underlie rare forms of hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa). J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:2459-2461. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.162

- Jemec GBE, Heidenheim M, Nielsen NH. The prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa and its potential precursor lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:191-194. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90321-7

- Fitzsimmons JS, Guilbert PR. A family study of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Med Genet. 1985;22:367-373. doi:10.1136/jmg.22.5.367

- Kelly G, Prens EP. Inflammatory mechanisms in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:51-58. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.08.004

- Yazdanyar S, Jemec GB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a review of cause and treatment. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:118-123. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283428d07

- Kathju S, Lasko LA, Stoodley P. Considering hidradenitis suppurativa as a bacterial biofilm disease. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2012;65:385-389. doi:10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.00946.x

- Jahns AC, Killasli H, Nosek D, et al. Microbiology of hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa): a histological study of 27 patients. APMIS. 2014;122:804-809. doi:10.1111/apm.12220

- Ralf Paus L, Kurzen H, Kurokawa I, et al. What causes hidradenitis suppurativa? Exp Dermatol. 2008;17:455-456. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00712_1.x

- Vazquez BG, Alikhan A, Weaver AL, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa and associated factors: a population-based study of Olmsted County, Minnesota. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:97-103. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.255

- Kromann CB, Ibler KS, Kristiansen VB, et al. The influence of body weight on the prevalence and severity of hidradenitis suppurativa. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:553-557. doi:10.2340/00015555-1800

- Lindsø Andersen P, Kromann C, Fonvig CE, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa in a cohort of overweight and obese children and adolescents. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:47-51. doi:10.1111/ijd.14639

- Revuz JE, Canoui-Poitrine F, Wolkenstein P, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with hidradenitis suppurativa: results from two case-control studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:596-601. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.06.020

- Kromann CB, Deckers IE, Esmann S, et al. Risk factors, clinical course and long-term prognosis in hidradenitis suppurativa: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:819-824. doi:10.1111/bjd.13090

- Wieczorek M, Walecka I. Hidradenitis suppurativa—known and unknown disease. Reumatologia. 2018;56:337-339. doi:10.5114/reum.2018.80709