User login

Break the ‘fear circuit’ in resistant panic disorder

When initial therapy fails to control a patient’s panic attacks, a neuroanatomic model of anxiety disorders may help. This model proposes that panic sufferers have an abnormally sensitive brain “fear circuit.”1 It suggests why both medications and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) are effective for treating panic disorder (PD) and can be used as a guide to more successful treatment.

This article explains the fear circuit model and describes how to determine whether initial drug treatment of panic symptoms has been adequate. It offers evidence-and experience-based dosing ranges, augmentation strategies, tips for antidepressant titration, and solutions to the most common inadequate response problems.

HOW THE FEAR CIRCUIT WORKS

Panic disorder may occur with or without agoraphobia. The diagnosis requires recurrent, unexpected panic attacks (Table 1), with at least one attack followed by 1 month or more of:

- persistent concern about having additional attacks

- worry about the implications of the attack

- or significant change in behavior related to the attack.

Panic disorder is usually accompanied by phobic avoidance and anticipatory anxiety, and it often coexists with other psychiatric disorders. Anxiety disorders may share a common genetic vulnerability. Childhood experiences, gender, and life events may increase or decrease the probability that a biologically vulnerable individual will develop an anxiety disorder or depression.1

Table 1

Panic attacks: The core symptom of panic disorder

| A panic attack is a discrete period of intense fear or discomfort, in which four (or more) of the following symptoms develop abruptly and peak within 10 minutes: |

|

| Source: DSM-IV-TR |

Fear circuit model. PD’s pathophysiology is not completely understood, but evidence suggests that an overactive brain alarm network may increase vulnerability for PD (Box).1,2 Individual patients require different intensities of treatment to normalize their panic symptoms:

Mild to moderate PD (characterized by little or no avoidance and no comorbid disorders) often responds to either medication or CBT. A single intervention—such as using CBT to enhance the cortical inhibitory effects or using medication to reduce the amygdala’s reactivity—may suffice for symptomatic relief.

Severe or complicated PD (characterized by frequent panic attacks, significant agoraphobia, and comorbid anxiety disorders or depression) may require high medication dosages, intense CBT/exposure therapy, or both to normalize more severely disrupted communication among the fear circuit’s components.

ASSESSING TREATMENT OUTCOME

The goal of treatment is remission: a return to functioning without illness-related impairment or loss of quality of life, as if the patient had never been ill. In clinical practice, we can use validated, patient-rated assessment tools to document improvement in panic-related impairment, patient satisfaction, and quality of life—the real targets of treatment. Two useful tools are the Sheehan Disability Scale3 and the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire.4

With adequate treatment, achieving remission can take several months or more; without it, remission may never occur. The following guidelines can help ensure that you provide adequate treatment.

What is adequate CBT? When patients’ symptoms fail to respond to CBT, the first step is to examine whether inadequate treatment is the culprit. At least 10 weekly CBT sessions administered by a “qualified professional” has been suggested as an adequate CBT trial for PD.5 Unfortunately, qualified CBT therapists are not always available. If CBT referral is not an option, clinicians can provide patients with at least some elements of CBT, such as education about PD, information resources, and self-exposure instruction as indicated. For more information on CBT for PD, see Related Resources.

What is adequate drug treatment? Noncompliance with medication because a patient fears adverse effects or has insufficient information can easily thwart treatment. Before treatment begins, therefore, it is important to establish your credibility. Provide the patient with information about PD, its treatment options, and what to expect so that he or she can collaborate in treatment (Table 2).

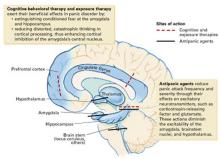

An inherited, abnormally active brain alarm mechanism—or “fear circuit”—may explain panic disorder, according to a theoretical neuroanatomic model.1 Its hub is the central nucleus of the amygdala, which coordinates fear responses via pathways communicating with the hippocampus, thalamus, hypothalamus, brainstem, and cortical processing areas.

The amygdala mediates acute emotional responses, including fear and anxiety. The hypothalamus mediates physiologic changes connected with emotions, such as release of stress hormones and some changes in heart rate. The prefrontal cortex is involved in thinking and memory and may be instrumental in predicting the consequences of rewards or punishments. In vulnerable individuals, defects in coordinating the sensory input among these brain regions may cause the central nucleus to discharge, resulting in a panic attack.

Medication and cognitive-behavioral therapy may reduce fear circuit reactivity and prevent panic attacks by acting at different components of the fear circuit. When the amygdala’s central nucleus no longer overreacts to sensory input, anticipatory anxiety and phobic avoidance usually dissipate over time.2,3 Thus, the fear circuit model integrates the clinical observation that both cognitive-behavioral therapy and medication are effective for treating panic.1

Abnormal interactions among components of this oversensitive fear circuit also may occur in social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression.1 In these disorders, communication patterns among the parts of the hypothesized circuit may be disrupted in different ways. The clinical observation that anxious individuals often become depressed when under stress is consistent with this model and with the literature.

Antidepressants are preferred as first-line treatment of PD, even in nondepressed patients. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are recommended for PD because of their comparable efficacy and tolerability compared with older antipanic agents.6 SSRIs are also effective against other anxiety disorders likely to co-occur with PD.7

Many panic patients are exquisitely sensitive to activation by initial antidepressant dosages. Activation rarely occurs in other disorders, so its appearance suggests that your diagnosis is correct. Clinical strategies to help you manage antidepressant titration are suggested in Table 3.

Table 2

Prescription for success in treating panic disorder

| Relieve patient of perceived burden of being ill Explain the disorder’s familial/genetic origins Describe the fear circuit model Include spouse or significant other in treatment |

| Build patient-physician collaboration Explain potential medication side effects Describe the usual pattern of symptom relief (stop panic attacks → reduce anticipatory anxiety → decrease phobia) Estimate a time frame for improvement Map out next steps if first try is unsuccessful Be available, especially at first |

| Address patient’s long-term medication concerns Discuss safety, long-term efficacy Frame treatment as a pathway to independence from panic attacks Use analogy of diabetes or hypertension to explain that medication is for managing symptoms, rather than a cure Discuss tapering medication after sustained improvement (12 to 18 months) to determine continued need for medication |

In clinical settings, two naturalistic studies suggested that more-favorable outcomes are associated with antipanic medication dosages shown in Table 4 as “possibly effective”—and that most patients with poor medication response received inadequate treatment.8,9Table 4 ’s dosages come from those two studies—published before the efficacy studies of SSRIs in PD—and from later studies of SSRIs and the selective norepinephrine-serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine.7,8,10

The lower end of the “probably effective” range in Table 4 represents the lowest dose levels generally expected to be effective for PD. Not all agents in the table are FDA-approved for PD, nor are the dosages of approved agents necessarily “within labeling.” Some patients’ symptoms may resolve at higher or lower dosages.

Table 3

Tips to help the patient tolerate antidepressant titration

| Be pre-emptive Before starting therapy, explain that low initial dosing and flexible titration help to control unpleasant but medically safe “jitteriness” known as antidepressant-induced activation Tell the patient that activation rarely occurs in disorders other than PD (“Its appearance suggests that the diagnosis is correct and that we’re likely on the right track”) |

| Be reassuring Tell the patient, “You control the gas peddle—I’ll help you steer” (to an effective dose) |

| Be cautious Start with 25 to 50% of the usual antidepressant initial dosage for depression (Table 4); if too activating, reduce and advance more gradually Activation usually dissipates in 1 to 2 weeks; over time, larger dosage increments are often possible |

| Be attentive Use benzodiazepines or beta blockers as needed to attenuate activation |

Some patients require months to reach and maintain the “probably effective” dosage for at least 6 weeks. Short-term benzodiazepines can be used to control panic symptoms during antidepressant titration, then tapered off.11 We categorize patients who are unable to tolerate an “adequate dose” as not having had a therapeutic trial—not as treatment failures.

No controlled studies of PD have examined the success rate of switching to a second antidepressant after a first one has been ineffective.12 In clinical practice, we may try two different SSRIs and venlafaxine. When switching agents, we usually co-administer the treatments for a few weeks, titrate the second agent upward gradually, then taper and discontinue the first agent over 2 to 4 weeks. We use short-term benzodiazepines as needed.

Partial improvement. Sometimes overall symptoms improve meaningfully, but bothersome panic symptoms remain. Clinical response may improve sufficiently if you raise the medication dosage in increments while monitoring for safety and tolerability. Address medicolegal concerns by documenting in the patient’s chart:

- your rationale for prescribing dosages that exceed FDA guidelines

- that you discussed possible risks versus benefits with the patient, and the patient agrees to the treatment.

When in doubt about using dosages that exceed FDA guidelines for patients with unusually resistant panic symptoms, obtain consultation from an expert or colleague.

Table 4

Recommended drug dosages for panic disorder

| Class/agent | Possibly effective (mg/d) | Probably effective (mg/d) | High dosage (mg/d) | Initial dosage (mg/d) | Confidence level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSRIs | |||||

| Citalopram | <20 | 20-60 | >60 | 10 | ++ |

| Escitalopram | <10 | 10-30 | >30 | 5 | ++++ |

| Fluoxetine | <40 | 40-80 | >80 | 10 | ++ |

| Fluvoxamine | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 25 | ++++ |

| Paroxetine* | <40 | 40-60 | >60 | 5-10 | ++++ |

| Sertraline* | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 12.5-25 | ++++ |

| SNRI | |||||

| Venlafaxine | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 18.75-37.5 | ++ |

| Benzodiazepines | |||||

| Alprazolam* | <2 | 2-8 | >8 | 0.5-1.0 | ++++ |

| Clonazepam* | <1 | 2-4 | >4 | 0.25-0.5 | ++++ |

| Tricyclics | |||||

| Clomipramine | <100 | 100-200 | >200 | 10 | ++++ |

| Desipramine | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 10 | ++ |

| Imipramine | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 10 | ++++ |

| MAOIs | |||||

| Phenelzine | <45 | 45-90 | >90 | 15 | +++ |

| Tranylcypromine | <30 | 30-70 | >70 | 10 | + |

| Antiepileptics | |||||

| Gabapentin | 100-200 | 600-3,400 | ++ | ||

| Valproate (VPA) | 250-500 | 1,000-2,000 | ++ | ||

| * FDA-approved for treating panic disorder | |||||

| Confidence: | |||||

| + (uncontrolled series) | |||||

| ++ (at least 1 controlled study) | |||||

| +++ (>1 controlled study) | |||||

| ++++ (Unequivocal) | |||||

Using benzodiazepines. As noted above, adjunctive use of benzodiazepines while initiating antidepressant therapy can help extremely anxious or medication-sensitive patients.11 Many clinicians coadminister benzodiazepines with antidepressants over the longer term.7 As a primary treatment, benzodiazepines may be useful for patients who could not tolerate or did not respond to at least two or three antidepressant trials.

Table 5

Solving inadequate response to initial SSRI treatment of panic disorder

| Problem | Differential diagnosis | Suggested solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Persistent panic attacks | Unexpected attacks Inadequate treatment or duration Situational attacks Medical condition Other psychiatric disorder | ≥Threshold dose for 6 weeks Try second SSRI Try venlafaxine CBT/exposure therapy Address specific conditions Rule out social phobia, OCD, PTSD |

| Persistent nonpanic anxiety | Medication-related Activation (SSRI or SNRI) Akathisia from SSRI Comorbid GAD Interdose BZD rebound BZD or alcohol withdrawal Residual anxiety | Adjust dosage, add BZD or beta blocker Adjust dosage, add beta blocker or BZD Increase antidepressant dosage, add BZD Switch to longer-acting agent Assess and treat as indicated Add/increase BZD |

| Residual phobia | Agoraphobia | CBT/exposure, adjust medication |

| Other disorders | Depression Bipolar disorder Personality disorders Medical disorder | Aggressive antidepressant treatment ±BZDs Mood stabilizer and antidepressant ±BZDs Specific psychotherapy Review and modify treatment as indicated |

| Environmental event or stressor(s) | Review work, family events, patient perception of stressor | Family/spouse interview and education Environmental hygiene as indicated Brief adjustment in treatment plan(s) as needed |

| Poor adherence | Drug sexual side effects Inadequate patient or family understanding of panic disorder and its treatment | Try bupropion, sildenafil, amantadine, switch agents Patient/family education Make resource materials available |

| BZD: Benzodiazepine | ||

| CBT: Cognitive-behavioral therapy | ||

| GAD: Generalized anxiety disorder | ||

| OCD: Obsessive-compulsive disorder | ||

| PTSD: Posttraumatic stress disorder | ||

| SNRI: Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | ||

| SSRI: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | ||

Because benzodiazepine monotherapy does not reliably protect against depression, we advise clinicians to encourage patients to self-monitor and report any signs of emerging depression. Avoid benzodiazepines in patients with a history of alcohol or substance abuse.7

Other agents. Once the mainstay of antipanic treatment, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are seldom used today because of their side effects, toxicity in overdose, and—for MAOIs—tyramine-restricted diet. Their usefulness in resistant panic is probably limited to last-ditch efforts.

DISSECTING TREATMENT FAILURE

In uncomplicated PD, lack of improvement after two or more adequate medication trials is unusual. If you observe minimal or no improvement, review carefully for other causes of anxiety or factors that can complicate PD treatment (Table 5).

If no other cause for the persistent symptom(s) is apparent, the fear circuit model may help you decide how to modify or enhance medication treatment, add CBT, or both.

For example:

- If panic attacks persist, advancing the medication dosage (if tolerated and acceptably safe) may help. Consider increasing the dosage, augmenting, or switching to a different agent.

- If persistent attacks are consistently cued to feared situations, try intervening with moreaggressive exposure therapy. Consider whether other disorders such as unrecognized social anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may be perpetuating the fearful avoidance.

- If the patient is depressed, consider that depression-related social withdrawal may be causing the avoidance symptoms. Aggressive antidepressant pharmacotherapy is strongly suggested.

AUGMENTATION STRATEGIES

Medication for CBT failure. Only two controlled studies have examined adding an adequate dose of medication after patients failed to respond to exposure/CBT alone:

- One study of 18 hospitalized patients with agoraphobia who failed a course of behavioral psychodynamic therapy reported improvement when clomipramine, 150 mg/d, was given for 3 weeks.13

- In a study of 43 patients who failed initial CBT, greater improvement was reported in patients who received CBT plus paroxetine, 40 mg/d, compared with those who received placebo while continuing CBT.14

Augmentation in drug therapy. Only one controlled study has examined augmentation therapy after lack of response to an SSRI—in this case 8 weeks of fluoxetine after two undefined “antidepressant failures.” When pindolol, 2.5 mg tid, or placebo were added to the fluoxetine therapy, the 13 patients who received pindolol improved clinically and statistically more on several standardized ratings than the 12 who received placebo.15

An 8-week, open-label trial showed beneficial effects of olanzapine, up to 20 mg/d, in patients with well-described treatment-resistant PD.16

Other well-described treatment adjustments reported to benefit nonresponsive PD include:

- Adding fluoxetine to a TCA or adding a TCA to fluoxetine, for TCA/SSRI combination therapy17

- Switching to the selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor reboxetine, 2 to 8 mg/d for 6 weeks after inadequate paroxetine or fluoxetine response (average of 8 weeks, maximum dosage 40 mg/d).18 (Note: Reboxetine is not available in the United States.)

- Using open-label gabapentin, 600 to 2,400 mg/d, after two SSRI treatment failures.19

- Adding the dopamine receptor agonist pramipexole, 1.0 to 1.5 mg/d, to various antipanic medications.20

Augmenting an SSRI with pindolol or supplementing unsuccessful behavioral treatment with “probably effective” dosages of paroxetine or clomipramine could be recommended with some confidence, although more definitive studies are needed. As outlined above, some strategies17-20 might be considered if a patient fails to respond to two or more adequate medication trials. Anecdotal reports are difficult to assess but may be clinically useful when other treatment options have been exhausted.

- Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders: the nature and treatment of anxiety and panic New York: Guilford Press, 1988.

- Craske MG, DeCola JP, Sachs AD, Pontillo DC. Panic control treatment of agoraphobia. J Anxiety Disord 2003;17:321-33.

- National Institute for Mental Health: Panic Disorder http://www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/fearandtrauma.cfm

- Anxiety Disorders Association of America http://www.adaa.org/

Drug brand names

- Alprazolam • Xanax

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clomipramine • Anafranil

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Desipramine • Norpramin

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Imipramine • Tofranil

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Phenelzine • Nardil

- Pindolol • Visken

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Pramipexole • Mirapex

- Reboxetine • Vestra

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Tranylcypromine • Parnate

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosure

Dr. Lydiard receives research support from GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly and Co., Organon, Sanofi-Synthelabo, Cephalon, UCB Pharma, and Merck & Co. and he is a speaker for or consultant to Pfizer Inc., Eli Lilly and Co., Solvay Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, and Forest Pharmaceuticals.

1. Gorman JM, Kent JM, Sullivan GM, Coplan JD. Neuroanatomical hypothesis of panic disorder, revisited. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:493-505.

2. Coplan JD, Lydiard RB. Brain circuits in panic disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1998;44:1264-76.

3. Sheehan DV. The anxiety disease. New York: Charles Scribner and Sons, 1983;151.-

4. Rapaport MH, Wolkow RM, Clary CM. Methodologies and outcomes from the sertraline multicenter flexible-dose trials. Psychopharmacol Bull 1998;34:183-9.

5. Otto MW. Psychosocial approach to treatment-resistant anxiety disorders (presentation). Chantilly, VA: Anxiety Disorders Association of America conference on novel approaches to treatment of refractory anxiety disorders, June 15-16, 2003.

6. Gorman JM, Shear MK, McIntyre JS, Zarin DA. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155(May supplement).

7. Lydiard RB, Otto MW, Milrod B. Panic disorder treatment. In: Gabbard, GO (ed). Treatment of psychiatric disorders (3rd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc, 2001;1447-82.

8. Simon NM, Safrens SA, Otto MW, et al. Outcome with pharmacotherapy in a naturalistic study of panic disorder. J Affect Disord 2002;69:201-8.

9. Yonkers KA, Ellison J, Shera D, et al. Description of antipanic therapy in a prospective longitudinal study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1996;16:223-32.

10. Pollack MH, Worthington JJ, 3rd, Otto MW, et al. Venlafaxine for panic disorder: results from a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Psychopharmacol Bull 1996;32:667-70.

11. Goddard AW, Brouette T, Almai A, et al. Early coadministration of clonazepam with sertraline for panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58:681-6.

12. Simon NM. Pharmacological approach to treatment-resistant anxiety disorders (presentation). Chantilly, VA: Anxiety Disorders Association of America conference on novel approaches to treatment of refractory anxiety disorders, June 15-16, 2003.

13. Hoffart A, Due-Madsen J, Lande B, et al. Clomipramine in the treatment of agoraphobic inpatients resistant to behavioral therapy. J Clin Psychiatry 1993;54:481-7.

14. Kampman M, Keijsers GP, Hoogduin CA, Hendriks GJ. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the effects of adjunctive paroxetine in panic disorder patients unsuccessfully treated with cognitive-behavioral therapy alone. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:772-7.

15. Hirschmann S, Dannon PN, Iancu I, et al. Pindolol augmentation in patients with treatment-resistant panic disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;20:556-9.

16. Hollifield M, Thompson P, Uhlenluth E. Potential efficacy and safety of olanzapine in refractory panic disorder (presentation). San Francisco: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, 2003.

17. Tiffon L, Coplan J, Papp L, Gorman J. Augmentation strategies with tricyclic or fluoxetine treatment in seven partially responsive panic disorder patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1994;55:66-9.

18. Dannon PN, Iancu I, Grunhaus L. The efficacy of reboxetine in treatment-refractory patients with panic disorder: an open-label study. Hum Psychopharmacol 2002;17:329-33.

19. Chiu S. Gabapentin treatment response in SSRI-refractory panic disorder (presentation) San Francisco: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, 2003.

20. Marazziti D, Presta S, Pfanner C, et al. Pramipexole augmentation in panic with agoraphobia. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:498-9.

When initial therapy fails to control a patient’s panic attacks, a neuroanatomic model of anxiety disorders may help. This model proposes that panic sufferers have an abnormally sensitive brain “fear circuit.”1 It suggests why both medications and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) are effective for treating panic disorder (PD) and can be used as a guide to more successful treatment.

This article explains the fear circuit model and describes how to determine whether initial drug treatment of panic symptoms has been adequate. It offers evidence-and experience-based dosing ranges, augmentation strategies, tips for antidepressant titration, and solutions to the most common inadequate response problems.

HOW THE FEAR CIRCUIT WORKS

Panic disorder may occur with or without agoraphobia. The diagnosis requires recurrent, unexpected panic attacks (Table 1), with at least one attack followed by 1 month or more of:

- persistent concern about having additional attacks

- worry about the implications of the attack

- or significant change in behavior related to the attack.

Panic disorder is usually accompanied by phobic avoidance and anticipatory anxiety, and it often coexists with other psychiatric disorders. Anxiety disorders may share a common genetic vulnerability. Childhood experiences, gender, and life events may increase or decrease the probability that a biologically vulnerable individual will develop an anxiety disorder or depression.1

Table 1

Panic attacks: The core symptom of panic disorder

| A panic attack is a discrete period of intense fear or discomfort, in which four (or more) of the following symptoms develop abruptly and peak within 10 minutes: |

|

| Source: DSM-IV-TR |

Fear circuit model. PD’s pathophysiology is not completely understood, but evidence suggests that an overactive brain alarm network may increase vulnerability for PD (Box).1,2 Individual patients require different intensities of treatment to normalize their panic symptoms:

Mild to moderate PD (characterized by little or no avoidance and no comorbid disorders) often responds to either medication or CBT. A single intervention—such as using CBT to enhance the cortical inhibitory effects or using medication to reduce the amygdala’s reactivity—may suffice for symptomatic relief.

Severe or complicated PD (characterized by frequent panic attacks, significant agoraphobia, and comorbid anxiety disorders or depression) may require high medication dosages, intense CBT/exposure therapy, or both to normalize more severely disrupted communication among the fear circuit’s components.

ASSESSING TREATMENT OUTCOME

The goal of treatment is remission: a return to functioning without illness-related impairment or loss of quality of life, as if the patient had never been ill. In clinical practice, we can use validated, patient-rated assessment tools to document improvement in panic-related impairment, patient satisfaction, and quality of life—the real targets of treatment. Two useful tools are the Sheehan Disability Scale3 and the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire.4

With adequate treatment, achieving remission can take several months or more; without it, remission may never occur. The following guidelines can help ensure that you provide adequate treatment.

What is adequate CBT? When patients’ symptoms fail to respond to CBT, the first step is to examine whether inadequate treatment is the culprit. At least 10 weekly CBT sessions administered by a “qualified professional” has been suggested as an adequate CBT trial for PD.5 Unfortunately, qualified CBT therapists are not always available. If CBT referral is not an option, clinicians can provide patients with at least some elements of CBT, such as education about PD, information resources, and self-exposure instruction as indicated. For more information on CBT for PD, see Related Resources.

What is adequate drug treatment? Noncompliance with medication because a patient fears adverse effects or has insufficient information can easily thwart treatment. Before treatment begins, therefore, it is important to establish your credibility. Provide the patient with information about PD, its treatment options, and what to expect so that he or she can collaborate in treatment (Table 2).

An inherited, abnormally active brain alarm mechanism—or “fear circuit”—may explain panic disorder, according to a theoretical neuroanatomic model.1 Its hub is the central nucleus of the amygdala, which coordinates fear responses via pathways communicating with the hippocampus, thalamus, hypothalamus, brainstem, and cortical processing areas.

The amygdala mediates acute emotional responses, including fear and anxiety. The hypothalamus mediates physiologic changes connected with emotions, such as release of stress hormones and some changes in heart rate. The prefrontal cortex is involved in thinking and memory and may be instrumental in predicting the consequences of rewards or punishments. In vulnerable individuals, defects in coordinating the sensory input among these brain regions may cause the central nucleus to discharge, resulting in a panic attack.

Medication and cognitive-behavioral therapy may reduce fear circuit reactivity and prevent panic attacks by acting at different components of the fear circuit. When the amygdala’s central nucleus no longer overreacts to sensory input, anticipatory anxiety and phobic avoidance usually dissipate over time.2,3 Thus, the fear circuit model integrates the clinical observation that both cognitive-behavioral therapy and medication are effective for treating panic.1

Abnormal interactions among components of this oversensitive fear circuit also may occur in social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression.1 In these disorders, communication patterns among the parts of the hypothesized circuit may be disrupted in different ways. The clinical observation that anxious individuals often become depressed when under stress is consistent with this model and with the literature.

Antidepressants are preferred as first-line treatment of PD, even in nondepressed patients. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are recommended for PD because of their comparable efficacy and tolerability compared with older antipanic agents.6 SSRIs are also effective against other anxiety disorders likely to co-occur with PD.7

Many panic patients are exquisitely sensitive to activation by initial antidepressant dosages. Activation rarely occurs in other disorders, so its appearance suggests that your diagnosis is correct. Clinical strategies to help you manage antidepressant titration are suggested in Table 3.

Table 2

Prescription for success in treating panic disorder

| Relieve patient of perceived burden of being ill Explain the disorder’s familial/genetic origins Describe the fear circuit model Include spouse or significant other in treatment |

| Build patient-physician collaboration Explain potential medication side effects Describe the usual pattern of symptom relief (stop panic attacks → reduce anticipatory anxiety → decrease phobia) Estimate a time frame for improvement Map out next steps if first try is unsuccessful Be available, especially at first |

| Address patient’s long-term medication concerns Discuss safety, long-term efficacy Frame treatment as a pathway to independence from panic attacks Use analogy of diabetes or hypertension to explain that medication is for managing symptoms, rather than a cure Discuss tapering medication after sustained improvement (12 to 18 months) to determine continued need for medication |

In clinical settings, two naturalistic studies suggested that more-favorable outcomes are associated with antipanic medication dosages shown in Table 4 as “possibly effective”—and that most patients with poor medication response received inadequate treatment.8,9Table 4 ’s dosages come from those two studies—published before the efficacy studies of SSRIs in PD—and from later studies of SSRIs and the selective norepinephrine-serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine.7,8,10

The lower end of the “probably effective” range in Table 4 represents the lowest dose levels generally expected to be effective for PD. Not all agents in the table are FDA-approved for PD, nor are the dosages of approved agents necessarily “within labeling.” Some patients’ symptoms may resolve at higher or lower dosages.

Table 3

Tips to help the patient tolerate antidepressant titration

| Be pre-emptive Before starting therapy, explain that low initial dosing and flexible titration help to control unpleasant but medically safe “jitteriness” known as antidepressant-induced activation Tell the patient that activation rarely occurs in disorders other than PD (“Its appearance suggests that the diagnosis is correct and that we’re likely on the right track”) |

| Be reassuring Tell the patient, “You control the gas peddle—I’ll help you steer” (to an effective dose) |

| Be cautious Start with 25 to 50% of the usual antidepressant initial dosage for depression (Table 4); if too activating, reduce and advance more gradually Activation usually dissipates in 1 to 2 weeks; over time, larger dosage increments are often possible |

| Be attentive Use benzodiazepines or beta blockers as needed to attenuate activation |

Some patients require months to reach and maintain the “probably effective” dosage for at least 6 weeks. Short-term benzodiazepines can be used to control panic symptoms during antidepressant titration, then tapered off.11 We categorize patients who are unable to tolerate an “adequate dose” as not having had a therapeutic trial—not as treatment failures.

No controlled studies of PD have examined the success rate of switching to a second antidepressant after a first one has been ineffective.12 In clinical practice, we may try two different SSRIs and venlafaxine. When switching agents, we usually co-administer the treatments for a few weeks, titrate the second agent upward gradually, then taper and discontinue the first agent over 2 to 4 weeks. We use short-term benzodiazepines as needed.

Partial improvement. Sometimes overall symptoms improve meaningfully, but bothersome panic symptoms remain. Clinical response may improve sufficiently if you raise the medication dosage in increments while monitoring for safety and tolerability. Address medicolegal concerns by documenting in the patient’s chart:

- your rationale for prescribing dosages that exceed FDA guidelines

- that you discussed possible risks versus benefits with the patient, and the patient agrees to the treatment.

When in doubt about using dosages that exceed FDA guidelines for patients with unusually resistant panic symptoms, obtain consultation from an expert or colleague.

Table 4

Recommended drug dosages for panic disorder

| Class/agent | Possibly effective (mg/d) | Probably effective (mg/d) | High dosage (mg/d) | Initial dosage (mg/d) | Confidence level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSRIs | |||||

| Citalopram | <20 | 20-60 | >60 | 10 | ++ |

| Escitalopram | <10 | 10-30 | >30 | 5 | ++++ |

| Fluoxetine | <40 | 40-80 | >80 | 10 | ++ |

| Fluvoxamine | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 25 | ++++ |

| Paroxetine* | <40 | 40-60 | >60 | 5-10 | ++++ |

| Sertraline* | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 12.5-25 | ++++ |

| SNRI | |||||

| Venlafaxine | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 18.75-37.5 | ++ |

| Benzodiazepines | |||||

| Alprazolam* | <2 | 2-8 | >8 | 0.5-1.0 | ++++ |

| Clonazepam* | <1 | 2-4 | >4 | 0.25-0.5 | ++++ |

| Tricyclics | |||||

| Clomipramine | <100 | 100-200 | >200 | 10 | ++++ |

| Desipramine | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 10 | ++ |

| Imipramine | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 10 | ++++ |

| MAOIs | |||||

| Phenelzine | <45 | 45-90 | >90 | 15 | +++ |

| Tranylcypromine | <30 | 30-70 | >70 | 10 | + |

| Antiepileptics | |||||

| Gabapentin | 100-200 | 600-3,400 | ++ | ||

| Valproate (VPA) | 250-500 | 1,000-2,000 | ++ | ||

| * FDA-approved for treating panic disorder | |||||

| Confidence: | |||||

| + (uncontrolled series) | |||||

| ++ (at least 1 controlled study) | |||||

| +++ (>1 controlled study) | |||||

| ++++ (Unequivocal) | |||||

Using benzodiazepines. As noted above, adjunctive use of benzodiazepines while initiating antidepressant therapy can help extremely anxious or medication-sensitive patients.11 Many clinicians coadminister benzodiazepines with antidepressants over the longer term.7 As a primary treatment, benzodiazepines may be useful for patients who could not tolerate or did not respond to at least two or three antidepressant trials.

Table 5

Solving inadequate response to initial SSRI treatment of panic disorder

| Problem | Differential diagnosis | Suggested solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Persistent panic attacks | Unexpected attacks Inadequate treatment or duration Situational attacks Medical condition Other psychiatric disorder | ≥Threshold dose for 6 weeks Try second SSRI Try venlafaxine CBT/exposure therapy Address specific conditions Rule out social phobia, OCD, PTSD |

| Persistent nonpanic anxiety | Medication-related Activation (SSRI or SNRI) Akathisia from SSRI Comorbid GAD Interdose BZD rebound BZD or alcohol withdrawal Residual anxiety | Adjust dosage, add BZD or beta blocker Adjust dosage, add beta blocker or BZD Increase antidepressant dosage, add BZD Switch to longer-acting agent Assess and treat as indicated Add/increase BZD |

| Residual phobia | Agoraphobia | CBT/exposure, adjust medication |

| Other disorders | Depression Bipolar disorder Personality disorders Medical disorder | Aggressive antidepressant treatment ±BZDs Mood stabilizer and antidepressant ±BZDs Specific psychotherapy Review and modify treatment as indicated |

| Environmental event or stressor(s) | Review work, family events, patient perception of stressor | Family/spouse interview and education Environmental hygiene as indicated Brief adjustment in treatment plan(s) as needed |

| Poor adherence | Drug sexual side effects Inadequate patient or family understanding of panic disorder and its treatment | Try bupropion, sildenafil, amantadine, switch agents Patient/family education Make resource materials available |

| BZD: Benzodiazepine | ||

| CBT: Cognitive-behavioral therapy | ||

| GAD: Generalized anxiety disorder | ||

| OCD: Obsessive-compulsive disorder | ||

| PTSD: Posttraumatic stress disorder | ||

| SNRI: Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | ||

| SSRI: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | ||

Because benzodiazepine monotherapy does not reliably protect against depression, we advise clinicians to encourage patients to self-monitor and report any signs of emerging depression. Avoid benzodiazepines in patients with a history of alcohol or substance abuse.7

Other agents. Once the mainstay of antipanic treatment, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are seldom used today because of their side effects, toxicity in overdose, and—for MAOIs—tyramine-restricted diet. Their usefulness in resistant panic is probably limited to last-ditch efforts.

DISSECTING TREATMENT FAILURE

In uncomplicated PD, lack of improvement after two or more adequate medication trials is unusual. If you observe minimal or no improvement, review carefully for other causes of anxiety or factors that can complicate PD treatment (Table 5).

If no other cause for the persistent symptom(s) is apparent, the fear circuit model may help you decide how to modify or enhance medication treatment, add CBT, or both.

For example:

- If panic attacks persist, advancing the medication dosage (if tolerated and acceptably safe) may help. Consider increasing the dosage, augmenting, or switching to a different agent.

- If persistent attacks are consistently cued to feared situations, try intervening with moreaggressive exposure therapy. Consider whether other disorders such as unrecognized social anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may be perpetuating the fearful avoidance.

- If the patient is depressed, consider that depression-related social withdrawal may be causing the avoidance symptoms. Aggressive antidepressant pharmacotherapy is strongly suggested.

AUGMENTATION STRATEGIES

Medication for CBT failure. Only two controlled studies have examined adding an adequate dose of medication after patients failed to respond to exposure/CBT alone:

- One study of 18 hospitalized patients with agoraphobia who failed a course of behavioral psychodynamic therapy reported improvement when clomipramine, 150 mg/d, was given for 3 weeks.13

- In a study of 43 patients who failed initial CBT, greater improvement was reported in patients who received CBT plus paroxetine, 40 mg/d, compared with those who received placebo while continuing CBT.14

Augmentation in drug therapy. Only one controlled study has examined augmentation therapy after lack of response to an SSRI—in this case 8 weeks of fluoxetine after two undefined “antidepressant failures.” When pindolol, 2.5 mg tid, or placebo were added to the fluoxetine therapy, the 13 patients who received pindolol improved clinically and statistically more on several standardized ratings than the 12 who received placebo.15

An 8-week, open-label trial showed beneficial effects of olanzapine, up to 20 mg/d, in patients with well-described treatment-resistant PD.16

Other well-described treatment adjustments reported to benefit nonresponsive PD include:

- Adding fluoxetine to a TCA or adding a TCA to fluoxetine, for TCA/SSRI combination therapy17

- Switching to the selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor reboxetine, 2 to 8 mg/d for 6 weeks after inadequate paroxetine or fluoxetine response (average of 8 weeks, maximum dosage 40 mg/d).18 (Note: Reboxetine is not available in the United States.)

- Using open-label gabapentin, 600 to 2,400 mg/d, after two SSRI treatment failures.19

- Adding the dopamine receptor agonist pramipexole, 1.0 to 1.5 mg/d, to various antipanic medications.20

Augmenting an SSRI with pindolol or supplementing unsuccessful behavioral treatment with “probably effective” dosages of paroxetine or clomipramine could be recommended with some confidence, although more definitive studies are needed. As outlined above, some strategies17-20 might be considered if a patient fails to respond to two or more adequate medication trials. Anecdotal reports are difficult to assess but may be clinically useful when other treatment options have been exhausted.

- Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders: the nature and treatment of anxiety and panic New York: Guilford Press, 1988.

- Craske MG, DeCola JP, Sachs AD, Pontillo DC. Panic control treatment of agoraphobia. J Anxiety Disord 2003;17:321-33.

- National Institute for Mental Health: Panic Disorder http://www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/fearandtrauma.cfm

- Anxiety Disorders Association of America http://www.adaa.org/

Drug brand names

- Alprazolam • Xanax

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clomipramine • Anafranil

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Desipramine • Norpramin

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Imipramine • Tofranil

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Phenelzine • Nardil

- Pindolol • Visken

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Pramipexole • Mirapex

- Reboxetine • Vestra

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Tranylcypromine • Parnate

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosure

Dr. Lydiard receives research support from GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly and Co., Organon, Sanofi-Synthelabo, Cephalon, UCB Pharma, and Merck & Co. and he is a speaker for or consultant to Pfizer Inc., Eli Lilly and Co., Solvay Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, and Forest Pharmaceuticals.

When initial therapy fails to control a patient’s panic attacks, a neuroanatomic model of anxiety disorders may help. This model proposes that panic sufferers have an abnormally sensitive brain “fear circuit.”1 It suggests why both medications and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) are effective for treating panic disorder (PD) and can be used as a guide to more successful treatment.

This article explains the fear circuit model and describes how to determine whether initial drug treatment of panic symptoms has been adequate. It offers evidence-and experience-based dosing ranges, augmentation strategies, tips for antidepressant titration, and solutions to the most common inadequate response problems.

HOW THE FEAR CIRCUIT WORKS

Panic disorder may occur with or without agoraphobia. The diagnosis requires recurrent, unexpected panic attacks (Table 1), with at least one attack followed by 1 month or more of:

- persistent concern about having additional attacks

- worry about the implications of the attack

- or significant change in behavior related to the attack.

Panic disorder is usually accompanied by phobic avoidance and anticipatory anxiety, and it often coexists with other psychiatric disorders. Anxiety disorders may share a common genetic vulnerability. Childhood experiences, gender, and life events may increase or decrease the probability that a biologically vulnerable individual will develop an anxiety disorder or depression.1

Table 1

Panic attacks: The core symptom of panic disorder

| A panic attack is a discrete period of intense fear or discomfort, in which four (or more) of the following symptoms develop abruptly and peak within 10 minutes: |

|

| Source: DSM-IV-TR |

Fear circuit model. PD’s pathophysiology is not completely understood, but evidence suggests that an overactive brain alarm network may increase vulnerability for PD (Box).1,2 Individual patients require different intensities of treatment to normalize their panic symptoms:

Mild to moderate PD (characterized by little or no avoidance and no comorbid disorders) often responds to either medication or CBT. A single intervention—such as using CBT to enhance the cortical inhibitory effects or using medication to reduce the amygdala’s reactivity—may suffice for symptomatic relief.

Severe or complicated PD (characterized by frequent panic attacks, significant agoraphobia, and comorbid anxiety disorders or depression) may require high medication dosages, intense CBT/exposure therapy, or both to normalize more severely disrupted communication among the fear circuit’s components.

ASSESSING TREATMENT OUTCOME

The goal of treatment is remission: a return to functioning without illness-related impairment or loss of quality of life, as if the patient had never been ill. In clinical practice, we can use validated, patient-rated assessment tools to document improvement in panic-related impairment, patient satisfaction, and quality of life—the real targets of treatment. Two useful tools are the Sheehan Disability Scale3 and the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire.4

With adequate treatment, achieving remission can take several months or more; without it, remission may never occur. The following guidelines can help ensure that you provide adequate treatment.

What is adequate CBT? When patients’ symptoms fail to respond to CBT, the first step is to examine whether inadequate treatment is the culprit. At least 10 weekly CBT sessions administered by a “qualified professional” has been suggested as an adequate CBT trial for PD.5 Unfortunately, qualified CBT therapists are not always available. If CBT referral is not an option, clinicians can provide patients with at least some elements of CBT, such as education about PD, information resources, and self-exposure instruction as indicated. For more information on CBT for PD, see Related Resources.

What is adequate drug treatment? Noncompliance with medication because a patient fears adverse effects or has insufficient information can easily thwart treatment. Before treatment begins, therefore, it is important to establish your credibility. Provide the patient with information about PD, its treatment options, and what to expect so that he or she can collaborate in treatment (Table 2).

An inherited, abnormally active brain alarm mechanism—or “fear circuit”—may explain panic disorder, according to a theoretical neuroanatomic model.1 Its hub is the central nucleus of the amygdala, which coordinates fear responses via pathways communicating with the hippocampus, thalamus, hypothalamus, brainstem, and cortical processing areas.

The amygdala mediates acute emotional responses, including fear and anxiety. The hypothalamus mediates physiologic changes connected with emotions, such as release of stress hormones and some changes in heart rate. The prefrontal cortex is involved in thinking and memory and may be instrumental in predicting the consequences of rewards or punishments. In vulnerable individuals, defects in coordinating the sensory input among these brain regions may cause the central nucleus to discharge, resulting in a panic attack.

Medication and cognitive-behavioral therapy may reduce fear circuit reactivity and prevent panic attacks by acting at different components of the fear circuit. When the amygdala’s central nucleus no longer overreacts to sensory input, anticipatory anxiety and phobic avoidance usually dissipate over time.2,3 Thus, the fear circuit model integrates the clinical observation that both cognitive-behavioral therapy and medication are effective for treating panic.1

Abnormal interactions among components of this oversensitive fear circuit also may occur in social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression.1 In these disorders, communication patterns among the parts of the hypothesized circuit may be disrupted in different ways. The clinical observation that anxious individuals often become depressed when under stress is consistent with this model and with the literature.

Antidepressants are preferred as first-line treatment of PD, even in nondepressed patients. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are recommended for PD because of their comparable efficacy and tolerability compared with older antipanic agents.6 SSRIs are also effective against other anxiety disorders likely to co-occur with PD.7

Many panic patients are exquisitely sensitive to activation by initial antidepressant dosages. Activation rarely occurs in other disorders, so its appearance suggests that your diagnosis is correct. Clinical strategies to help you manage antidepressant titration are suggested in Table 3.

Table 2

Prescription for success in treating panic disorder

| Relieve patient of perceived burden of being ill Explain the disorder’s familial/genetic origins Describe the fear circuit model Include spouse or significant other in treatment |

| Build patient-physician collaboration Explain potential medication side effects Describe the usual pattern of symptom relief (stop panic attacks → reduce anticipatory anxiety → decrease phobia) Estimate a time frame for improvement Map out next steps if first try is unsuccessful Be available, especially at first |

| Address patient’s long-term medication concerns Discuss safety, long-term efficacy Frame treatment as a pathway to independence from panic attacks Use analogy of diabetes or hypertension to explain that medication is for managing symptoms, rather than a cure Discuss tapering medication after sustained improvement (12 to 18 months) to determine continued need for medication |

In clinical settings, two naturalistic studies suggested that more-favorable outcomes are associated with antipanic medication dosages shown in Table 4 as “possibly effective”—and that most patients with poor medication response received inadequate treatment.8,9Table 4 ’s dosages come from those two studies—published before the efficacy studies of SSRIs in PD—and from later studies of SSRIs and the selective norepinephrine-serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine.7,8,10

The lower end of the “probably effective” range in Table 4 represents the lowest dose levels generally expected to be effective for PD. Not all agents in the table are FDA-approved for PD, nor are the dosages of approved agents necessarily “within labeling.” Some patients’ symptoms may resolve at higher or lower dosages.

Table 3

Tips to help the patient tolerate antidepressant titration

| Be pre-emptive Before starting therapy, explain that low initial dosing and flexible titration help to control unpleasant but medically safe “jitteriness” known as antidepressant-induced activation Tell the patient that activation rarely occurs in disorders other than PD (“Its appearance suggests that the diagnosis is correct and that we’re likely on the right track”) |

| Be reassuring Tell the patient, “You control the gas peddle—I’ll help you steer” (to an effective dose) |

| Be cautious Start with 25 to 50% of the usual antidepressant initial dosage for depression (Table 4); if too activating, reduce and advance more gradually Activation usually dissipates in 1 to 2 weeks; over time, larger dosage increments are often possible |

| Be attentive Use benzodiazepines or beta blockers as needed to attenuate activation |

Some patients require months to reach and maintain the “probably effective” dosage for at least 6 weeks. Short-term benzodiazepines can be used to control panic symptoms during antidepressant titration, then tapered off.11 We categorize patients who are unable to tolerate an “adequate dose” as not having had a therapeutic trial—not as treatment failures.

No controlled studies of PD have examined the success rate of switching to a second antidepressant after a first one has been ineffective.12 In clinical practice, we may try two different SSRIs and venlafaxine. When switching agents, we usually co-administer the treatments for a few weeks, titrate the second agent upward gradually, then taper and discontinue the first agent over 2 to 4 weeks. We use short-term benzodiazepines as needed.

Partial improvement. Sometimes overall symptoms improve meaningfully, but bothersome panic symptoms remain. Clinical response may improve sufficiently if you raise the medication dosage in increments while monitoring for safety and tolerability. Address medicolegal concerns by documenting in the patient’s chart:

- your rationale for prescribing dosages that exceed FDA guidelines

- that you discussed possible risks versus benefits with the patient, and the patient agrees to the treatment.

When in doubt about using dosages that exceed FDA guidelines for patients with unusually resistant panic symptoms, obtain consultation from an expert or colleague.

Table 4

Recommended drug dosages for panic disorder

| Class/agent | Possibly effective (mg/d) | Probably effective (mg/d) | High dosage (mg/d) | Initial dosage (mg/d) | Confidence level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSRIs | |||||

| Citalopram | <20 | 20-60 | >60 | 10 | ++ |

| Escitalopram | <10 | 10-30 | >30 | 5 | ++++ |

| Fluoxetine | <40 | 40-80 | >80 | 10 | ++ |

| Fluvoxamine | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 25 | ++++ |

| Paroxetine* | <40 | 40-60 | >60 | 5-10 | ++++ |

| Sertraline* | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 12.5-25 | ++++ |

| SNRI | |||||

| Venlafaxine | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 18.75-37.5 | ++ |

| Benzodiazepines | |||||

| Alprazolam* | <2 | 2-8 | >8 | 0.5-1.0 | ++++ |

| Clonazepam* | <1 | 2-4 | >4 | 0.25-0.5 | ++++ |

| Tricyclics | |||||

| Clomipramine | <100 | 100-200 | >200 | 10 | ++++ |

| Desipramine | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 10 | ++ |

| Imipramine | <150 | 150-300 | >300 | 10 | ++++ |

| MAOIs | |||||

| Phenelzine | <45 | 45-90 | >90 | 15 | +++ |

| Tranylcypromine | <30 | 30-70 | >70 | 10 | + |

| Antiepileptics | |||||

| Gabapentin | 100-200 | 600-3,400 | ++ | ||

| Valproate (VPA) | 250-500 | 1,000-2,000 | ++ | ||

| * FDA-approved for treating panic disorder | |||||

| Confidence: | |||||

| + (uncontrolled series) | |||||

| ++ (at least 1 controlled study) | |||||

| +++ (>1 controlled study) | |||||

| ++++ (Unequivocal) | |||||

Using benzodiazepines. As noted above, adjunctive use of benzodiazepines while initiating antidepressant therapy can help extremely anxious or medication-sensitive patients.11 Many clinicians coadminister benzodiazepines with antidepressants over the longer term.7 As a primary treatment, benzodiazepines may be useful for patients who could not tolerate or did not respond to at least two or three antidepressant trials.

Table 5

Solving inadequate response to initial SSRI treatment of panic disorder

| Problem | Differential diagnosis | Suggested solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Persistent panic attacks | Unexpected attacks Inadequate treatment or duration Situational attacks Medical condition Other psychiatric disorder | ≥Threshold dose for 6 weeks Try second SSRI Try venlafaxine CBT/exposure therapy Address specific conditions Rule out social phobia, OCD, PTSD |

| Persistent nonpanic anxiety | Medication-related Activation (SSRI or SNRI) Akathisia from SSRI Comorbid GAD Interdose BZD rebound BZD or alcohol withdrawal Residual anxiety | Adjust dosage, add BZD or beta blocker Adjust dosage, add beta blocker or BZD Increase antidepressant dosage, add BZD Switch to longer-acting agent Assess and treat as indicated Add/increase BZD |

| Residual phobia | Agoraphobia | CBT/exposure, adjust medication |

| Other disorders | Depression Bipolar disorder Personality disorders Medical disorder | Aggressive antidepressant treatment ±BZDs Mood stabilizer and antidepressant ±BZDs Specific psychotherapy Review and modify treatment as indicated |

| Environmental event or stressor(s) | Review work, family events, patient perception of stressor | Family/spouse interview and education Environmental hygiene as indicated Brief adjustment in treatment plan(s) as needed |

| Poor adherence | Drug sexual side effects Inadequate patient or family understanding of panic disorder and its treatment | Try bupropion, sildenafil, amantadine, switch agents Patient/family education Make resource materials available |

| BZD: Benzodiazepine | ||

| CBT: Cognitive-behavioral therapy | ||

| GAD: Generalized anxiety disorder | ||

| OCD: Obsessive-compulsive disorder | ||

| PTSD: Posttraumatic stress disorder | ||

| SNRI: Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | ||

| SSRI: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | ||

Because benzodiazepine monotherapy does not reliably protect against depression, we advise clinicians to encourage patients to self-monitor and report any signs of emerging depression. Avoid benzodiazepines in patients with a history of alcohol or substance abuse.7

Other agents. Once the mainstay of antipanic treatment, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are seldom used today because of their side effects, toxicity in overdose, and—for MAOIs—tyramine-restricted diet. Their usefulness in resistant panic is probably limited to last-ditch efforts.

DISSECTING TREATMENT FAILURE

In uncomplicated PD, lack of improvement after two or more adequate medication trials is unusual. If you observe minimal or no improvement, review carefully for other causes of anxiety or factors that can complicate PD treatment (Table 5).

If no other cause for the persistent symptom(s) is apparent, the fear circuit model may help you decide how to modify or enhance medication treatment, add CBT, or both.

For example:

- If panic attacks persist, advancing the medication dosage (if tolerated and acceptably safe) may help. Consider increasing the dosage, augmenting, or switching to a different agent.

- If persistent attacks are consistently cued to feared situations, try intervening with moreaggressive exposure therapy. Consider whether other disorders such as unrecognized social anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may be perpetuating the fearful avoidance.

- If the patient is depressed, consider that depression-related social withdrawal may be causing the avoidance symptoms. Aggressive antidepressant pharmacotherapy is strongly suggested.

AUGMENTATION STRATEGIES

Medication for CBT failure. Only two controlled studies have examined adding an adequate dose of medication after patients failed to respond to exposure/CBT alone:

- One study of 18 hospitalized patients with agoraphobia who failed a course of behavioral psychodynamic therapy reported improvement when clomipramine, 150 mg/d, was given for 3 weeks.13

- In a study of 43 patients who failed initial CBT, greater improvement was reported in patients who received CBT plus paroxetine, 40 mg/d, compared with those who received placebo while continuing CBT.14

Augmentation in drug therapy. Only one controlled study has examined augmentation therapy after lack of response to an SSRI—in this case 8 weeks of fluoxetine after two undefined “antidepressant failures.” When pindolol, 2.5 mg tid, or placebo were added to the fluoxetine therapy, the 13 patients who received pindolol improved clinically and statistically more on several standardized ratings than the 12 who received placebo.15

An 8-week, open-label trial showed beneficial effects of olanzapine, up to 20 mg/d, in patients with well-described treatment-resistant PD.16

Other well-described treatment adjustments reported to benefit nonresponsive PD include:

- Adding fluoxetine to a TCA or adding a TCA to fluoxetine, for TCA/SSRI combination therapy17

- Switching to the selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor reboxetine, 2 to 8 mg/d for 6 weeks after inadequate paroxetine or fluoxetine response (average of 8 weeks, maximum dosage 40 mg/d).18 (Note: Reboxetine is not available in the United States.)

- Using open-label gabapentin, 600 to 2,400 mg/d, after two SSRI treatment failures.19

- Adding the dopamine receptor agonist pramipexole, 1.0 to 1.5 mg/d, to various antipanic medications.20

Augmenting an SSRI with pindolol or supplementing unsuccessful behavioral treatment with “probably effective” dosages of paroxetine or clomipramine could be recommended with some confidence, although more definitive studies are needed. As outlined above, some strategies17-20 might be considered if a patient fails to respond to two or more adequate medication trials. Anecdotal reports are difficult to assess but may be clinically useful when other treatment options have been exhausted.

- Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders: the nature and treatment of anxiety and panic New York: Guilford Press, 1988.

- Craske MG, DeCola JP, Sachs AD, Pontillo DC. Panic control treatment of agoraphobia. J Anxiety Disord 2003;17:321-33.

- National Institute for Mental Health: Panic Disorder http://www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/fearandtrauma.cfm

- Anxiety Disorders Association of America http://www.adaa.org/

Drug brand names

- Alprazolam • Xanax

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clomipramine • Anafranil

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Desipramine • Norpramin

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Imipramine • Tofranil

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Phenelzine • Nardil

- Pindolol • Visken

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Pramipexole • Mirapex

- Reboxetine • Vestra

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Tranylcypromine • Parnate

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosure

Dr. Lydiard receives research support from GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly and Co., Organon, Sanofi-Synthelabo, Cephalon, UCB Pharma, and Merck & Co. and he is a speaker for or consultant to Pfizer Inc., Eli Lilly and Co., Solvay Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, and Forest Pharmaceuticals.

1. Gorman JM, Kent JM, Sullivan GM, Coplan JD. Neuroanatomical hypothesis of panic disorder, revisited. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:493-505.

2. Coplan JD, Lydiard RB. Brain circuits in panic disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1998;44:1264-76.

3. Sheehan DV. The anxiety disease. New York: Charles Scribner and Sons, 1983;151.-

4. Rapaport MH, Wolkow RM, Clary CM. Methodologies and outcomes from the sertraline multicenter flexible-dose trials. Psychopharmacol Bull 1998;34:183-9.

5. Otto MW. Psychosocial approach to treatment-resistant anxiety disorders (presentation). Chantilly, VA: Anxiety Disorders Association of America conference on novel approaches to treatment of refractory anxiety disorders, June 15-16, 2003.

6. Gorman JM, Shear MK, McIntyre JS, Zarin DA. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155(May supplement).

7. Lydiard RB, Otto MW, Milrod B. Panic disorder treatment. In: Gabbard, GO (ed). Treatment of psychiatric disorders (3rd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc, 2001;1447-82.

8. Simon NM, Safrens SA, Otto MW, et al. Outcome with pharmacotherapy in a naturalistic study of panic disorder. J Affect Disord 2002;69:201-8.

9. Yonkers KA, Ellison J, Shera D, et al. Description of antipanic therapy in a prospective longitudinal study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1996;16:223-32.

10. Pollack MH, Worthington JJ, 3rd, Otto MW, et al. Venlafaxine for panic disorder: results from a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Psychopharmacol Bull 1996;32:667-70.

11. Goddard AW, Brouette T, Almai A, et al. Early coadministration of clonazepam with sertraline for panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58:681-6.

12. Simon NM. Pharmacological approach to treatment-resistant anxiety disorders (presentation). Chantilly, VA: Anxiety Disorders Association of America conference on novel approaches to treatment of refractory anxiety disorders, June 15-16, 2003.

13. Hoffart A, Due-Madsen J, Lande B, et al. Clomipramine in the treatment of agoraphobic inpatients resistant to behavioral therapy. J Clin Psychiatry 1993;54:481-7.

14. Kampman M, Keijsers GP, Hoogduin CA, Hendriks GJ. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the effects of adjunctive paroxetine in panic disorder patients unsuccessfully treated with cognitive-behavioral therapy alone. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:772-7.

15. Hirschmann S, Dannon PN, Iancu I, et al. Pindolol augmentation in patients with treatment-resistant panic disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;20:556-9.

16. Hollifield M, Thompson P, Uhlenluth E. Potential efficacy and safety of olanzapine in refractory panic disorder (presentation). San Francisco: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, 2003.

17. Tiffon L, Coplan J, Papp L, Gorman J. Augmentation strategies with tricyclic or fluoxetine treatment in seven partially responsive panic disorder patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1994;55:66-9.

18. Dannon PN, Iancu I, Grunhaus L. The efficacy of reboxetine in treatment-refractory patients with panic disorder: an open-label study. Hum Psychopharmacol 2002;17:329-33.

19. Chiu S. Gabapentin treatment response in SSRI-refractory panic disorder (presentation) San Francisco: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, 2003.

20. Marazziti D, Presta S, Pfanner C, et al. Pramipexole augmentation in panic with agoraphobia. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:498-9.

1. Gorman JM, Kent JM, Sullivan GM, Coplan JD. Neuroanatomical hypothesis of panic disorder, revisited. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:493-505.

2. Coplan JD, Lydiard RB. Brain circuits in panic disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1998;44:1264-76.

3. Sheehan DV. The anxiety disease. New York: Charles Scribner and Sons, 1983;151.-

4. Rapaport MH, Wolkow RM, Clary CM. Methodologies and outcomes from the sertraline multicenter flexible-dose trials. Psychopharmacol Bull 1998;34:183-9.

5. Otto MW. Psychosocial approach to treatment-resistant anxiety disorders (presentation). Chantilly, VA: Anxiety Disorders Association of America conference on novel approaches to treatment of refractory anxiety disorders, June 15-16, 2003.

6. Gorman JM, Shear MK, McIntyre JS, Zarin DA. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155(May supplement).

7. Lydiard RB, Otto MW, Milrod B. Panic disorder treatment. In: Gabbard, GO (ed). Treatment of psychiatric disorders (3rd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc, 2001;1447-82.

8. Simon NM, Safrens SA, Otto MW, et al. Outcome with pharmacotherapy in a naturalistic study of panic disorder. J Affect Disord 2002;69:201-8.

9. Yonkers KA, Ellison J, Shera D, et al. Description of antipanic therapy in a prospective longitudinal study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1996;16:223-32.

10. Pollack MH, Worthington JJ, 3rd, Otto MW, et al. Venlafaxine for panic disorder: results from a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Psychopharmacol Bull 1996;32:667-70.

11. Goddard AW, Brouette T, Almai A, et al. Early coadministration of clonazepam with sertraline for panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58:681-6.

12. Simon NM. Pharmacological approach to treatment-resistant anxiety disorders (presentation). Chantilly, VA: Anxiety Disorders Association of America conference on novel approaches to treatment of refractory anxiety disorders, June 15-16, 2003.

13. Hoffart A, Due-Madsen J, Lande B, et al. Clomipramine in the treatment of agoraphobic inpatients resistant to behavioral therapy. J Clin Psychiatry 1993;54:481-7.

14. Kampman M, Keijsers GP, Hoogduin CA, Hendriks GJ. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the effects of adjunctive paroxetine in panic disorder patients unsuccessfully treated with cognitive-behavioral therapy alone. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:772-7.

15. Hirschmann S, Dannon PN, Iancu I, et al. Pindolol augmentation in patients with treatment-resistant panic disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;20:556-9.

16. Hollifield M, Thompson P, Uhlenluth E. Potential efficacy and safety of olanzapine in refractory panic disorder (presentation). San Francisco: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, 2003.

17. Tiffon L, Coplan J, Papp L, Gorman J. Augmentation strategies with tricyclic or fluoxetine treatment in seven partially responsive panic disorder patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1994;55:66-9.

18. Dannon PN, Iancu I, Grunhaus L. The efficacy of reboxetine in treatment-refractory patients with panic disorder: an open-label study. Hum Psychopharmacol 2002;17:329-33.

19. Chiu S. Gabapentin treatment response in SSRI-refractory panic disorder (presentation) San Francisco: American Psychiatric Association annual meeting, 2003.

20. Marazziti D, Presta S, Pfanner C, et al. Pramipexole augmentation in panic with agoraphobia. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:498-9.

When does shyness become a disorder?

Social phobia was accorded official psychiatric diagnostic status in the United States less than 20 years ago, but has been described in the medical literature for centuries. Hippocrates described such a patient: “He dare not come in company for fear he should be misused, disgraced, overshoot himself in gestures or speeches or be sick; he thinks every man observes him.”1

This observation was made more than 2,000 years ago. Yet social anxiety disorder (SAD) was left largely unstudied until the mid-1980s.2 An estimated 20 million people in the U.S. suffer from this disorder.

What causes some people to break into a cold sweat at the thought of the most casual encounter with a checkout clerk, a coworker, or an acquaintance? Limited evidence points to underlying biological abnormalities in SAD, but there have been no conclusive findings.

Two main subtypes of SAD exist (Box 1). Roughly 25% of sufferers have discrete or nongeneralized SAD, that is, circumscribed social fears limited to one or two situations, such as speaking in public or performing before an audience. The remaining 75% suffer from generalized SAD, the more severe subtype in which all or nearly all interpersonal interactions are difficult.

Generalized SAD often begins early in life, with a mean onset at about age 15, but 35% of the time SAD occurs in individuals before age 10.3 This subtype appears to run in families, while the nongeneralized subtype does not, suggesting that a genetic inheritance is possible. From an etiological perspective, the possible effects of parenting styles of socially anxious parents, or acquisition of social anxiety conditioned by experiencing extreme embarrassment, may also contribute to the development of SAD in some people. Approximately twice as many females as males are affected, and almost all are affected before age 25.3,4 When social fears interfere with social, occupational, or family life, the affected individual is not suffering from normal "shyness," but rather a treatable anxiety disorder.

–Toastmasters slogan

Generalized

- Most social interactions

- Early onset

- Social skills deficit

- High comorbidity

- Lower achievement

- Remission rare

Nongeneralized

- Limited fears

- Later onset

- Social skills normal

- Less comorbidity

- Less Impairment

- Remits often

The National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) estimated lifetime prevalence of SAD at 13.3% and 12-month prevalence at 7.6%, making it the third most common psychiatric disorder, following only major depression and alcohol abuse/dependence.5 Despite this high rate, SAD remains woefully underdiagnosed.

Anyone who has had to speak in public, play a musical instrument at a recital, or perform in some way under the watchful expectation of an audience has experienced anxiety as he or she anticipates the "big moment” (Box 2). Once the performance is under way, the anxiety usually lessens to a more manageable level for most people. In fact, nearly one in three Americans will admit to moderate or great fear of speaking in public.

Mr. L, a 40-year-old eighth-grade teacher, consulted a psychiatrist because he was scheduled to be evaluated by a state education accreditation committee while teaching class. Though he had always passed these before, he had been worried sick for weeks and was experiencing panic attacks each time he thought about the accreditation visit.

He lived with his mother, had never dated, and had few friends. He was extremely inhibited outside the classroom, brought cash to stores to avoid being observed while writing a check or signing credit card slips, and avoided social gatherings outside of his church, which he attended with his mother and tolerated with distress.

Further history revealed that he had quit medical school during his third year because he had so much difficulty presenting cases to the attending on ward rounds that he chose to leave the profession in order to avoid feeling sick each morning and afternoon.

Enough people encounter the fear of public speaking to support the weekly Toastmasters meetings in most U.S. cities. Many people overcome their social anxiety about public speaking or performing with continued practice. However, those with nongeneralized SAD, who are among the most severely affected, may remain so fearful of speaking or performing under scrutiny that they avoid it at any cost—even if it means passing up a job or promotion or even choosing to change professions.

The majority (75%) of those with SAD—representing approximately 15 million individuals in the U.S.—suffer from generalized SAD, a much more severe, potentially disabling subtype. These unfortunate individuals fear and avoid most or all social interactions outside their home except those with family or close friends. When they encounter or even anticipate entering feared social situations, individuals with generalized SAD experience severe anxiety. Blushing, tremulousness, and sweating can be noticed by others, and thus are particularly distressing to those with SAD.

Recovery without treatment is rare. The typically early age at onset of generalized SAD3,4 imposes greater limitations on development of social competence than on those who develop more discrete fear of public speaking or performing later in life—after socialization skills have already developed.

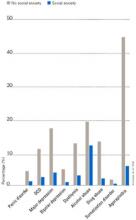

Individuals with SAD frequently suffer from comorbid psychiatric disorders, mostly depression and/or other anxiety disorders.6Figure 1 shows that individuals with SAD are at significantly increased risk for depression, other anxiety disorders, and alcohol and drug abuse. Since generalized SAD usually appears at an earlier age than other anxiety disorders, it represents a risk factor for subsequent depression. The level of functional impairment caused by SAD is similar to that caused by major depression7 (Figure 2).

As more comorbid psychiatric disorders accrue, impairment and increased risk for additional disorders may occur. Further, the risk of suicide is increased in those with comorbid SAD vs. those with SAD only. The findings suggest that if social anxiety were detected and treated effectively at an early age, it might be possible to prevent other psychiatric disorders—particularly depression—as well as the predictable morbidity and mortality that accompanies untreated SAD. Given the estimated $44 billion annual cost of anxiety disorders in the U.S.,8 research targeted at testing this hypothesis would appear to be a good investment.

Figure 1 HOW PREVALENT IS LIFETIME COMORBIDITY IN SAD?

- Inherent avoidance of scrutiny, (e.g., evaluation)

- Uncertain diagnostic threshold

- Acceptance of pathological shyness as ‘just my personality’

- Lack of understanding by professionals, family, friends

- Coping strategies that mask disability

- Comorbid psychiatric disorders that mask SAD

Figure 2 QUALITY OF LIFE IN PATIENTS WITH SOCIAL ANXIETY DISORDER

Seeing the unseen: making the diagnosis quickly