User login

Diversity in the Dermatology Workforce: 2017 Status Update

Physician diversity benefits patient care: Patients are more satisfied during race-concordant visits, report their physicians as more engaged and responsive to their needs, and experience notably longer visits.1,2 Nonwhite physicians (ie, races and ethnicities that are underrepresented in medicine [URM] with respect to the general population) are more likely to care for underserved communities. Furthermore, increased diversity in the learning environment supports preparedness of all trainees to serve diverse patients.3 For these reasons, a more diverse physician workforce can contribute to better access to care in all communities, thus addressing health disparities.1,4

Increasing diversity in the dermatology workforce has been identified as an emerging priority.5 Dermatology is one of the least diverse specialties,5 and the representation of URM dermatologists is lower compared to other medical specialties and the general US population. The proportion of specialty leaders from underrepresented backgrounds may be even smaller. The lack of diversity in academic dermatology has negative consequences for patients and communities. Increasing the diversity of resident trainees is the only way to improve the diversity gap within the dermatology workforce.6

Recent commentary on this topic has highlighted several priorities for addressing the dermatology diversity gap,6-11 including the following: (1) making diversity an explicit goal in dermatology; (2) ensuring early exposure to dermatology in medical school; (3) supporting mentorship programs for minority medical students; (4) increasing medical student diversity; (5) encouraging that all dermatology program directors and leaders train in implicit bias; and (6) reviewing residency admission criteria to ensure they are objective and equitable, not biased against any applicants.

The process of reviewing residency selection criteria has begun. In 2017, Chen and Shinkai7 called for our specialty to rethink the selection process. The authors argued that emphasis on test scores, grades, and publications systematically disadvantages underrepresented minorities and students from lower socioeconomic statuses. The authors proposed several solutions: (1) make diversity an explicit goal of the selection process, (2) shift away from test scores for all applicants, (3) change the interview format, (4) prioritize other competencies such as observation skills, and (5) recruit and retain faculty who support URM trainees.7

Several dermatology leadership groups have taken action to promote programs that aim to improve diversity within dermatology. The Dermatology Diversity Champions initiative includes 6 US dermatology residency programs that are committed to increasing diversity and collaborate to evaluate pilot approaches. The American Academy of Dermatology President’s Conference on Diversity in Dermatology in Chicago, Illinois, in August 2017, as well as the focus on diversity in residency training programs at the Annual Meeting of the Association of Professors of Dermatology in Chicago, Illinois, in October 2017, are strong indicators that our specialty as a whole is aware and eager to embrace diversity as a priority. The American Academy of Dermatology President’s Conference, which was comprised of representatives from many leadership organizations and interest groups within dermatology, identified 3 action items: (1) increase the pipeline of URM students into medical school, (2) increase interest in dermatology among URM medical students, and (3) increase URM representation in residency training programs.

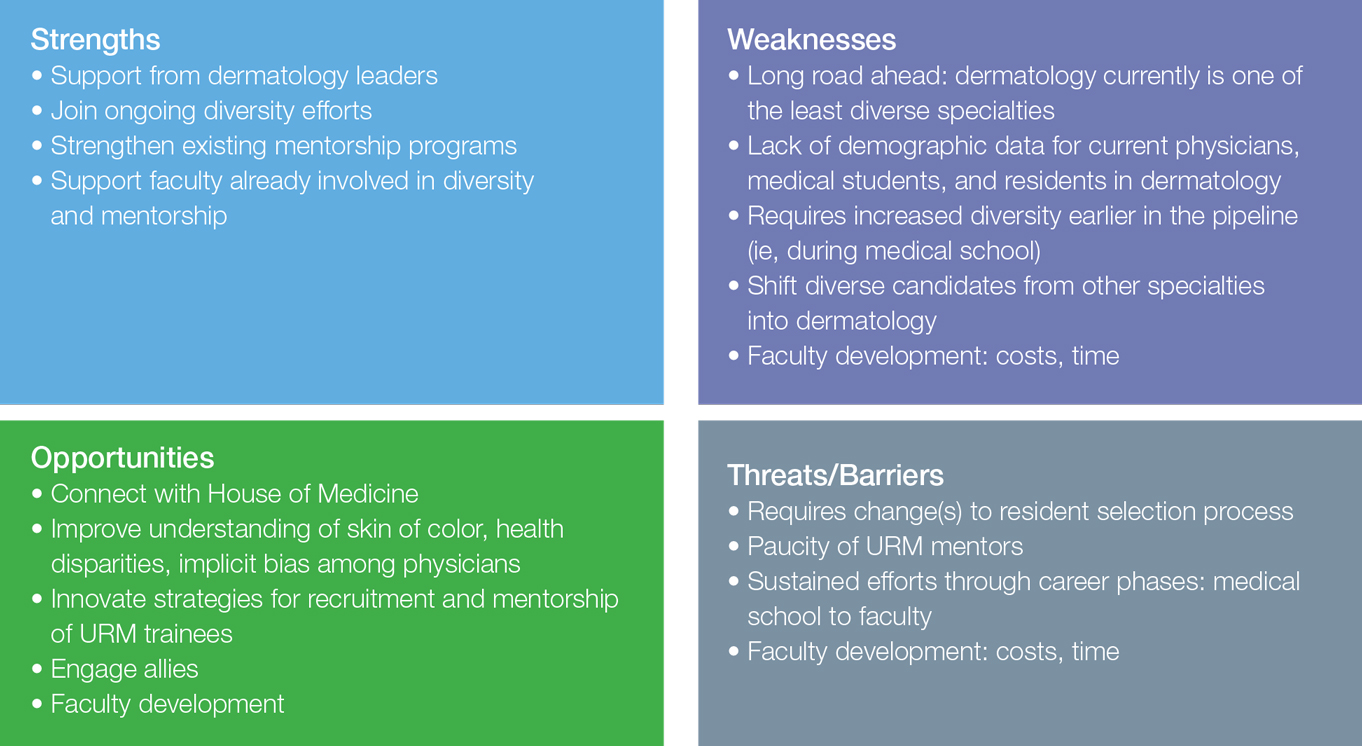

There are many strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats/barriers (SWOT) to attaining this goal. Current strengths include strong support from dermatology leaders and activities that build on existing mentorship and diversity efforts by leaders within our specialty. SWOT analysis highlights several key opportunities of this mission, including connecting with the House of Medicine in shared efforts to improve diversity, as well as increased understanding of skin of color, health disparities, and implicit bias among physicians. Although faculty development will require time and financial investment, it will lead to tremendous benefits and opportunities for all dermatologists, including URM physicians. Other weaknesses and threats/barriers are outlined in the Figure.

Final Thoughts

We are far from reaching our goal of a diverse dermatology workforce, and the road ahead is long. We have a start and we have momentum. We can move forward by spreading the word that all types of diversity are a priority for our specialty. Making a true difference will require commitment and sustained efforts. Dermatology can lead the way as all of American medicine strives to attain workforce diversity.

- Saha S. Taking diversity seriously: the merits of increasing minority representation in medicine. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:291-292.

- Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, et al. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:907-915.

- Saha S, Guiton G, Wimmers PF, et al. Student body racial and ethnic composition and diversity-related outcomes in US medical schools. JAMA. 2008;300:1135-1145.

- Marrast LM, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, et al. Minority physicians’ role in the care of underserved patients: diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing health disparities. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:289-291.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Lester J, Wintroub B, Linos E. Disparities in academic dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:878-879.

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants—turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260.

- Granstein RD, Cornelius L, Shinkai K. Diversity in dermatology—a call for action. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:499-500.

- McKesey J, Berger TG, Lim HW, et al. Cultural competence for the 21st century dermatologist practicing in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:1159-1169.

- Van Voorhees AS, Enos CW. Diversity in dermatology residency programs. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S46-S49.

- Imadojemu S, James WD. Increasing African American representation in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:15-16.

Physician diversity benefits patient care: Patients are more satisfied during race-concordant visits, report their physicians as more engaged and responsive to their needs, and experience notably longer visits.1,2 Nonwhite physicians (ie, races and ethnicities that are underrepresented in medicine [URM] with respect to the general population) are more likely to care for underserved communities. Furthermore, increased diversity in the learning environment supports preparedness of all trainees to serve diverse patients.3 For these reasons, a more diverse physician workforce can contribute to better access to care in all communities, thus addressing health disparities.1,4

Increasing diversity in the dermatology workforce has been identified as an emerging priority.5 Dermatology is one of the least diverse specialties,5 and the representation of URM dermatologists is lower compared to other medical specialties and the general US population. The proportion of specialty leaders from underrepresented backgrounds may be even smaller. The lack of diversity in academic dermatology has negative consequences for patients and communities. Increasing the diversity of resident trainees is the only way to improve the diversity gap within the dermatology workforce.6

Recent commentary on this topic has highlighted several priorities for addressing the dermatology diversity gap,6-11 including the following: (1) making diversity an explicit goal in dermatology; (2) ensuring early exposure to dermatology in medical school; (3) supporting mentorship programs for minority medical students; (4) increasing medical student diversity; (5) encouraging that all dermatology program directors and leaders train in implicit bias; and (6) reviewing residency admission criteria to ensure they are objective and equitable, not biased against any applicants.

The process of reviewing residency selection criteria has begun. In 2017, Chen and Shinkai7 called for our specialty to rethink the selection process. The authors argued that emphasis on test scores, grades, and publications systematically disadvantages underrepresented minorities and students from lower socioeconomic statuses. The authors proposed several solutions: (1) make diversity an explicit goal of the selection process, (2) shift away from test scores for all applicants, (3) change the interview format, (4) prioritize other competencies such as observation skills, and (5) recruit and retain faculty who support URM trainees.7

Several dermatology leadership groups have taken action to promote programs that aim to improve diversity within dermatology. The Dermatology Diversity Champions initiative includes 6 US dermatology residency programs that are committed to increasing diversity and collaborate to evaluate pilot approaches. The American Academy of Dermatology President’s Conference on Diversity in Dermatology in Chicago, Illinois, in August 2017, as well as the focus on diversity in residency training programs at the Annual Meeting of the Association of Professors of Dermatology in Chicago, Illinois, in October 2017, are strong indicators that our specialty as a whole is aware and eager to embrace diversity as a priority. The American Academy of Dermatology President’s Conference, which was comprised of representatives from many leadership organizations and interest groups within dermatology, identified 3 action items: (1) increase the pipeline of URM students into medical school, (2) increase interest in dermatology among URM medical students, and (3) increase URM representation in residency training programs.

There are many strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats/barriers (SWOT) to attaining this goal. Current strengths include strong support from dermatology leaders and activities that build on existing mentorship and diversity efforts by leaders within our specialty. SWOT analysis highlights several key opportunities of this mission, including connecting with the House of Medicine in shared efforts to improve diversity, as well as increased understanding of skin of color, health disparities, and implicit bias among physicians. Although faculty development will require time and financial investment, it will lead to tremendous benefits and opportunities for all dermatologists, including URM physicians. Other weaknesses and threats/barriers are outlined in the Figure.

Final Thoughts

We are far from reaching our goal of a diverse dermatology workforce, and the road ahead is long. We have a start and we have momentum. We can move forward by spreading the word that all types of diversity are a priority for our specialty. Making a true difference will require commitment and sustained efforts. Dermatology can lead the way as all of American medicine strives to attain workforce diversity.

Physician diversity benefits patient care: Patients are more satisfied during race-concordant visits, report their physicians as more engaged and responsive to their needs, and experience notably longer visits.1,2 Nonwhite physicians (ie, races and ethnicities that are underrepresented in medicine [URM] with respect to the general population) are more likely to care for underserved communities. Furthermore, increased diversity in the learning environment supports preparedness of all trainees to serve diverse patients.3 For these reasons, a more diverse physician workforce can contribute to better access to care in all communities, thus addressing health disparities.1,4

Increasing diversity in the dermatology workforce has been identified as an emerging priority.5 Dermatology is one of the least diverse specialties,5 and the representation of URM dermatologists is lower compared to other medical specialties and the general US population. The proportion of specialty leaders from underrepresented backgrounds may be even smaller. The lack of diversity in academic dermatology has negative consequences for patients and communities. Increasing the diversity of resident trainees is the only way to improve the diversity gap within the dermatology workforce.6

Recent commentary on this topic has highlighted several priorities for addressing the dermatology diversity gap,6-11 including the following: (1) making diversity an explicit goal in dermatology; (2) ensuring early exposure to dermatology in medical school; (3) supporting mentorship programs for minority medical students; (4) increasing medical student diversity; (5) encouraging that all dermatology program directors and leaders train in implicit bias; and (6) reviewing residency admission criteria to ensure they are objective and equitable, not biased against any applicants.

The process of reviewing residency selection criteria has begun. In 2017, Chen and Shinkai7 called for our specialty to rethink the selection process. The authors argued that emphasis on test scores, grades, and publications systematically disadvantages underrepresented minorities and students from lower socioeconomic statuses. The authors proposed several solutions: (1) make diversity an explicit goal of the selection process, (2) shift away from test scores for all applicants, (3) change the interview format, (4) prioritize other competencies such as observation skills, and (5) recruit and retain faculty who support URM trainees.7

Several dermatology leadership groups have taken action to promote programs that aim to improve diversity within dermatology. The Dermatology Diversity Champions initiative includes 6 US dermatology residency programs that are committed to increasing diversity and collaborate to evaluate pilot approaches. The American Academy of Dermatology President’s Conference on Diversity in Dermatology in Chicago, Illinois, in August 2017, as well as the focus on diversity in residency training programs at the Annual Meeting of the Association of Professors of Dermatology in Chicago, Illinois, in October 2017, are strong indicators that our specialty as a whole is aware and eager to embrace diversity as a priority. The American Academy of Dermatology President’s Conference, which was comprised of representatives from many leadership organizations and interest groups within dermatology, identified 3 action items: (1) increase the pipeline of URM students into medical school, (2) increase interest in dermatology among URM medical students, and (3) increase URM representation in residency training programs.

There are many strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats/barriers (SWOT) to attaining this goal. Current strengths include strong support from dermatology leaders and activities that build on existing mentorship and diversity efforts by leaders within our specialty. SWOT analysis highlights several key opportunities of this mission, including connecting with the House of Medicine in shared efforts to improve diversity, as well as increased understanding of skin of color, health disparities, and implicit bias among physicians. Although faculty development will require time and financial investment, it will lead to tremendous benefits and opportunities for all dermatologists, including URM physicians. Other weaknesses and threats/barriers are outlined in the Figure.

Final Thoughts

We are far from reaching our goal of a diverse dermatology workforce, and the road ahead is long. We have a start and we have momentum. We can move forward by spreading the word that all types of diversity are a priority for our specialty. Making a true difference will require commitment and sustained efforts. Dermatology can lead the way as all of American medicine strives to attain workforce diversity.

- Saha S. Taking diversity seriously: the merits of increasing minority representation in medicine. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:291-292.

- Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, et al. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:907-915.

- Saha S, Guiton G, Wimmers PF, et al. Student body racial and ethnic composition and diversity-related outcomes in US medical schools. JAMA. 2008;300:1135-1145.

- Marrast LM, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, et al. Minority physicians’ role in the care of underserved patients: diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing health disparities. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:289-291.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Lester J, Wintroub B, Linos E. Disparities in academic dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:878-879.

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants—turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260.

- Granstein RD, Cornelius L, Shinkai K. Diversity in dermatology—a call for action. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:499-500.

- McKesey J, Berger TG, Lim HW, et al. Cultural competence for the 21st century dermatologist practicing in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:1159-1169.

- Van Voorhees AS, Enos CW. Diversity in dermatology residency programs. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S46-S49.

- Imadojemu S, James WD. Increasing African American representation in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:15-16.

- Saha S. Taking diversity seriously: the merits of increasing minority representation in medicine. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:291-292.

- Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, et al. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:907-915.

- Saha S, Guiton G, Wimmers PF, et al. Student body racial and ethnic composition and diversity-related outcomes in US medical schools. JAMA. 2008;300:1135-1145.

- Marrast LM, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, et al. Minority physicians’ role in the care of underserved patients: diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing health disparities. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:289-291.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Lester J, Wintroub B, Linos E. Disparities in academic dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:878-879.

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants—turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260.

- Granstein RD, Cornelius L, Shinkai K. Diversity in dermatology—a call for action. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:499-500.

- McKesey J, Berger TG, Lim HW, et al. Cultural competence for the 21st century dermatologist practicing in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:1159-1169.

- Van Voorhees AS, Enos CW. Diversity in dermatology residency programs. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S46-S49.

- Imadojemu S, James WD. Increasing African American representation in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:15-16.