User login

Severity of Symptoms

The frequency and severity of symptoms among older hospitalized patients with chronic illnesses can have a profound negative impact on their quality of life.1, 2 Nonetheless, research examining the prevalence and management of symptoms has focused predominantly on cancer patients.3 Few studies have included patients with other serious conditions such as heart failure (HF) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),3, 4 which are very common and are major causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States.5 One longitudinal assessment of symptom severity among a group of community‐based older adults diagnosed with COPD and HF reported high rates of moderate‐to‐severe pain, dyspnea, and anxiety at baseline and follow‐up, as long as 22 months later.6 Persistent symptoms over time can have an adverse effect on an individual's physical and emotional well‐being, and highlight opportunities to improve care.3, 7 Understanding patterns of symptom change over time is a key first step in developing systems to improve quality of care for people with chronic illness.

Among hospitalized patients, pain, dyspnea, anxiety, and depression cause the greatest symptom burden, accounting for 67% of all symptoms classified as moderate to severe.8 While assessment and management of symptoms may be the reason for admission to the hospital and the focus of inpatient care, this focus may not persist after discharge, leaving patients with significant symptoms that can diminish quality of life and contribute to readmission.9 We studied a cohort of older inpatients with serious illness over time in order to determine the prevalence, severity, burden, and predictors of symptoms during the course of hospitalization and at 2 weeks after discharge.

METHODS

Setting

The study was undertaken at a large academic medical center in San Francisco.

Subjects

Participants were patients 65 years or older admitted to the medicine or cardiology services with a primary diagnosis of cancer, COPD, or HF. Participants were required to be fully oriented and English‐speaking. Patients gave written informed consent to participate. The Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco, approved this study (H8695‐35172‐01).

Data Collection

Data collection was undertaken from March 2001 to December 2003. This study was part of a prospective, clinical trial that compared a proactive palliative medicine consultation with usual hospital care, and has been previously described.10 Upon study enrollment, all patients completed the Inpatient Care Survey. The survey asked participants about demographic information such as date of birth, sex, education level, race, and marital status. The survey instruments also included the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) index and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS‐15). Each weekday during hospitalization, a trained research assistant asked patients to report their worst symptom level for pain, dyspnea, and anxiety in the past 24 hours using a 010 numeric rating scale, where 0 was none and 10 was the worst you can imagine. We further characterized scores into categories such that 0 was defined as none, 13 as mild, 46 as moderate, and 710 as severe. A follow‐up telephone survey, 2 weeks after discharge, reassessed patients' worst symptom levels in the past 24 hours for pain, dyspnea, and anxiety.

We also generated a composite score of symptoms to report a symptom burden score for these 3 symptoms. Using the categories of symptom severity, we assigned a score of 0 for none, 1 for mild, 2 for moderate, and 3 for severe. We summed the assigned scores for all 3 symptoms for each subject to generate a symptom burden score as follows: no symptom burden (0), mild symptom burden (13), moderate symptom burden (46), and severe symptom burden (79). In this scale, a moderate symptom burden would mean that a subject reported having at least 1 symptom at a moderate or severe level, with at least 1 other symptom present. A severe symptom burden would require the presence of all 3 symptoms, with at least 1 at a severe level.

We reviewed patient charts to assess severity of patient illness upon admission. For cancer, we recorded type; for COPD, we noted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1); and for HF, we recorded the ejection fraction. We also queried the National Death Index to get vital statistics on all subjects.

Data Preparation

The IADL asks patients to report whether they can perform 13 daily living skills without help, with some help, or were unable to complete tasks.11 Subjects who reported needing at least some help with any of the 13 items were categorized as dependent. The GDS‐15 is a widely used, validated 15‐item scale for assessing depressive mood in the elderly.12 Scores for the GDS‐15 range from 0 to 15, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms. Based on previous research, we categorized patients as either not depressed (05) or having probable depression (6 or more).12

Statistical Analysis

Because our clinical trial had no impact on care or symptoms, we combined intervention and usual care patients for this analysis of symptom severity. Descriptive statistics, such as frequencies, means, standard deviations (SDs), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to examine the distribution of measures. Chi‐square (2) analysis was undertaken to examine bivariate associations between categorical variables. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was undertaken to examine associations between categorical and continuous variables. Multivariate logistic regression was used to examine predictors of symptom burden at follow‐up, including patient characteristics that were significant to P 0.10 in bivariate analysis. We used KaplanMeier survival curves to examine the relationship between primary diagnosis and mortality, and assessed statistical significance using log‐rank tests (MantelCox).13 The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Mac (version 17; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL; March 11, 2009) was used to analyze these data.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

A total of 150 patients enrolled in the study. The mean length of stay was 5.4 days (SD: 5.6; range: 147 days). HF was the most common primary diagnosis (46.7%, n = 70) with 48% (n = 34) having an ejection fraction of 45% or less (mean = 43%; SD: 22); followed by cancer (30%, n = 45) with the most common type being prostate (18%, n = 8), lung (13%, n = 6), and breast (13%, n = 6); and COPD (23%, n = 35) with an average FEV1 of 1.5 L (SD: 0.94; range: 0.503.9). The mean age was 77 years (SD: 7.9; range: 6596 years). The majority of participants were men (56%, n = 83) and white (73%, n = 108), with the most being either married/partnered (43%, n = 64) or divorced/widowed (44%, n = 66). The IADL identified almost two‐thirds of participants as dependent (62%, n = 94). The GDS‐15 categorized three‐quarters of participants (n = 118) as not depressed. The only significant association between participant characteristics and their primary diagnosis was for the IADL index (Table 1), with significantly more (2 = 6.3; P = 0.04) patients with HF categorized as being dependent (72%).

| Characteristics | Primary Diagnosis | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer n = 44 | HF n = 70 | COPD n = 35 | |||

| |||||

| Length of stay | (Mean days) | 5.4 | 4.7 | 6.5 | 0.3 |

| Age | (Mean years) | 76 | 78 | 76 | 0.3 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 47% | 37% | 57% | 0.1 | |

| Marital status | 0.2 | ||||

| Single | 16 | 9 | 17 | ||

| Married/partnered | 51 | 45 | 29 | ||

| Divorced/widowed | 33 | 46 | 54 | ||

| Race | |||||

| White | 89 | 64 | 69 | 0.1 | |

| Black/African American | 7 | 21 | 23 | ||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 5 | 10 | 9 | ||

| Other | 0 | 4 | 0 | ||

| IADL | |||||

| Dependent | 49 | 72 | 60 | 0.04 | |

| GDS‐15 | |||||

| Probable depression | 18 | 22 | 21 | 0.9 | |

Frequency and Severity of Symptoms

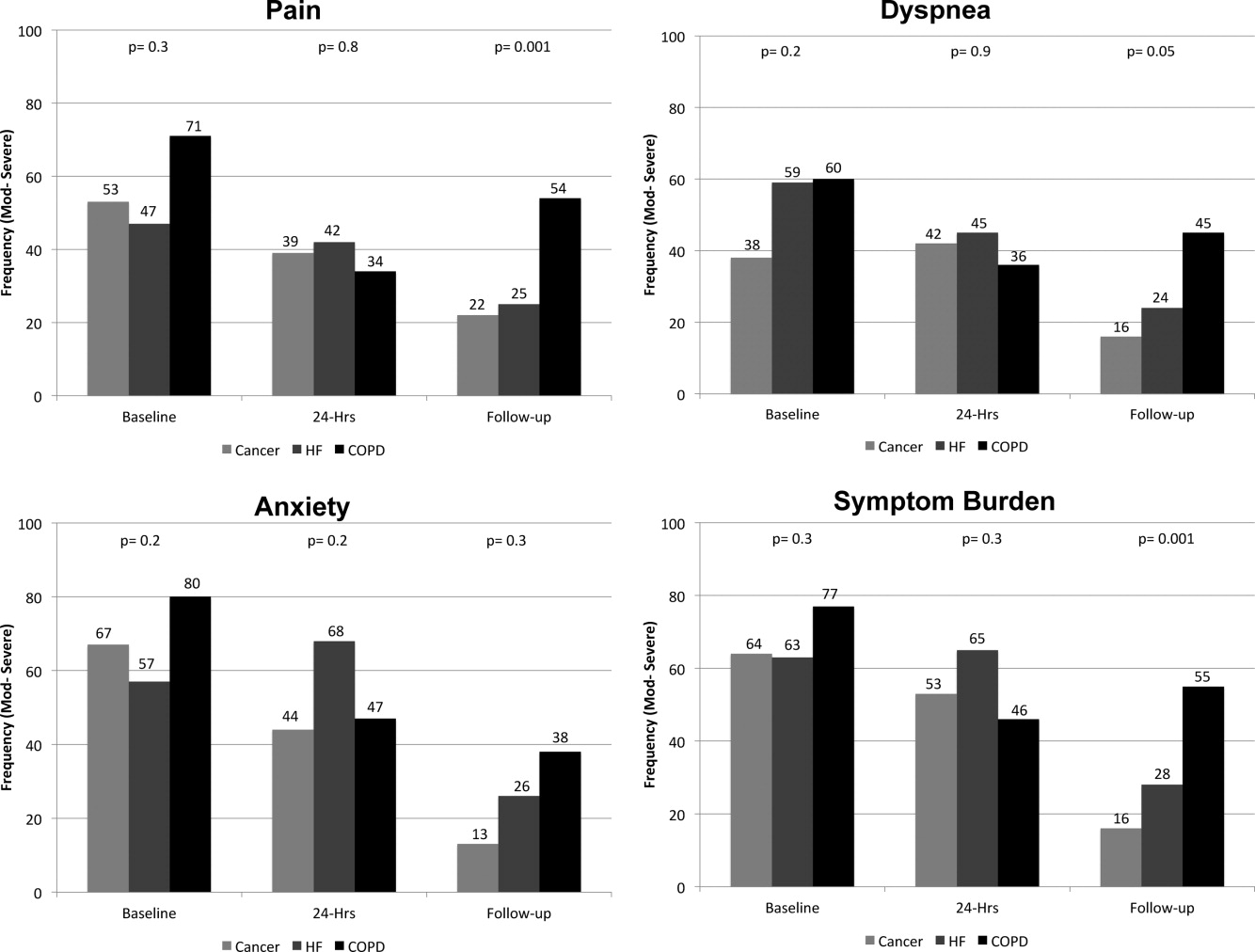

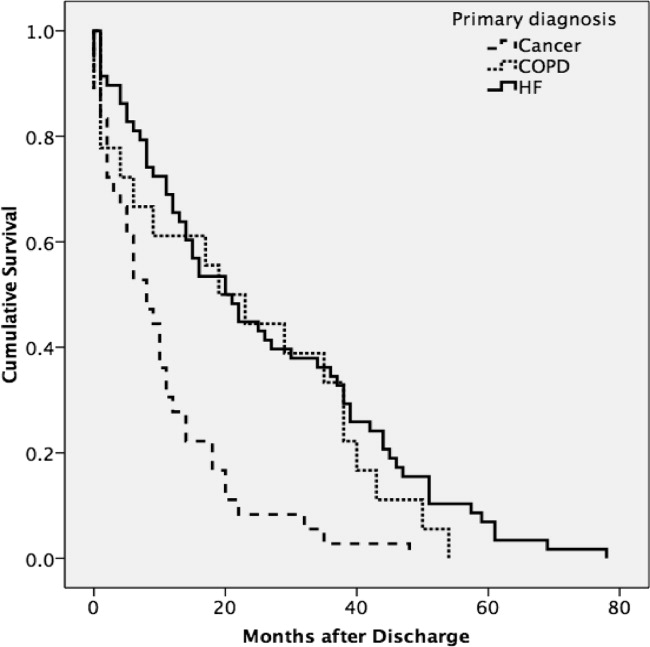

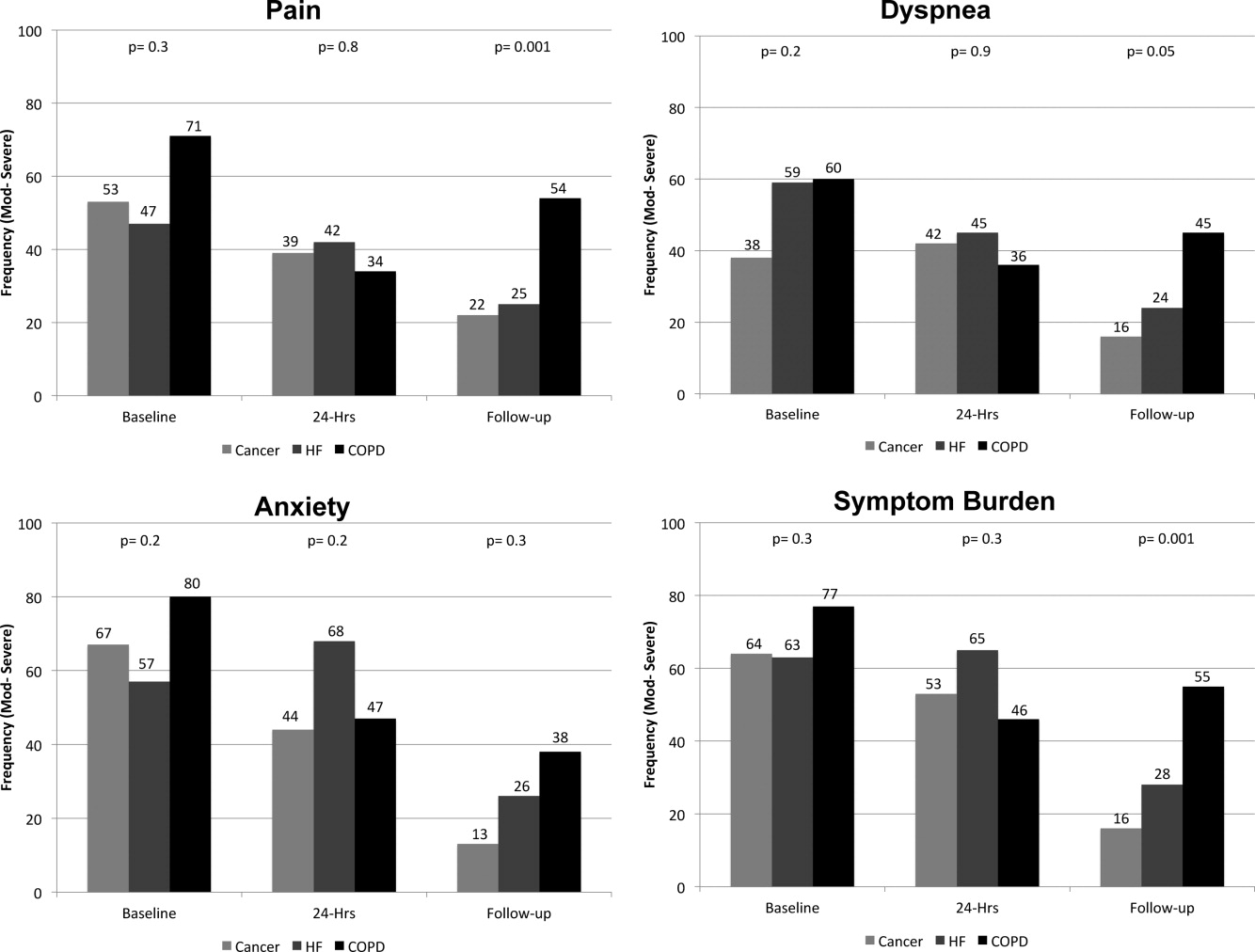

On average, the postdischarge follow‐up assessment was undertaken 24 days (median = 21.0; SD: 17.9; range: 7140 days) after the baseline assessment and 20 days after discharge (median = 15; SD: 17.0; range: 4139). At baseline, a large proportion of participants reported symptoms at a moderate‐to‐severe level for pain (54%, n = 81), dyspnea (53%, n = 79), and anxiety (63%, n = 94). The majority of patients (64%, n = 96) reported having 2 or more symptoms at a moderate‐to‐severe level and one quarter (27%, n = 41) had 3 symptoms at a moderate‐to‐severe level. While the frequency of moderate‐to‐severe symptoms decreased at the 24‐hour hospital assessment (pain = 42%, dyspnea = 45%, anxiety = 55%) and again at 2‐week follow‐up (pain = 28%, dyspnea = 27%, anxiety = 25%), a substantial symptom burden persisted with 30% (n = 36) of patients having moderate‐to‐severe levels at 2‐week follow‐up. Overall there were no differences between primary diagnosis and the frequency of symptoms at baseline or 24‐hour hospital assessment (Figure 1). However at follow‐up, those diagnosed with COPD were more likely to report moderate/severe pain (54%; 2 = 22.0; P < 0.001), dyspnea (45%; 2 = 9.3; P = 0.05), and overall symptom burden (55%; 2 = 25.9; P < 0.001) than those with cancer (pain = 22%, dyspnea = 16%, symptom burden = 16%) or HF (pain = 25%, dyspnea = 24%, symptom burden = 28%).

As symptom burden was our composite score for pain, dyspnea, and anxiety, we were interested in identifying variables in addition to primary diagnosis that might be associated with symptom burden at follow‐up. Bivariate analysis revealed that there was no significant association between symptom burden and age (2 = 1.5; P = 0.5), gender (2 = 1.3; P = 0.3), length of stay (2 = 0.4; P = 0.8), and (IADL) level of independence (2 = 0.3; P = 0.6). However, those with probable depression were more likely (2 = 11.9; P = 0.001) to have a moderate/severe symptom burden (62%, n = 13), compared to those with no depression (24%, n = 23). After adjusting for severity of symptom burden at baseline, multivariate logistic regression revealed that primary diagnosis (P = 0.01) and probable depression (OR = 4.9; 95% CI = 1.6, 14.9; P = 0.005) were associated with symptom severity. Patients with COPD had greater odds (OR = 7.0; 95% CI = 1.9, 26.2; P = 0.002) of moderate/severe symptom burden than those with cancer, while those with HF did not (OR = 2.3; 95% CI = 0.7, 7.7; P = 0.16). There was significant interaction between primary diagnosis and depression (P = 0.2).

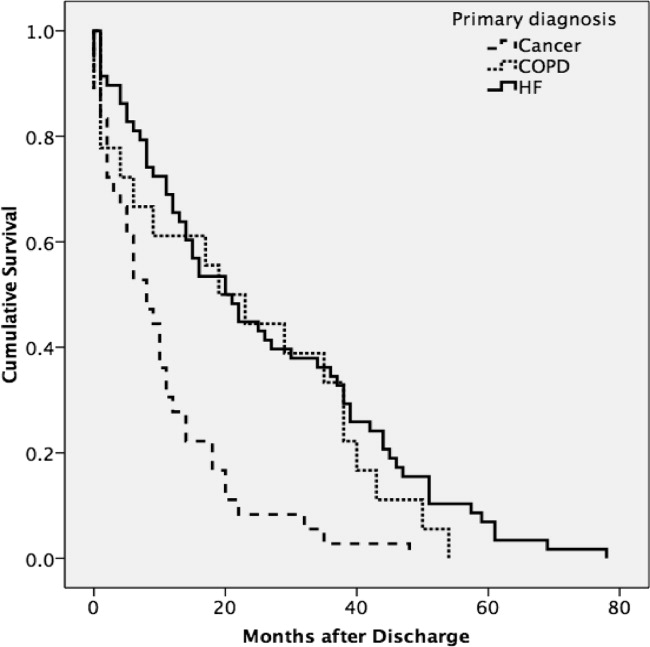

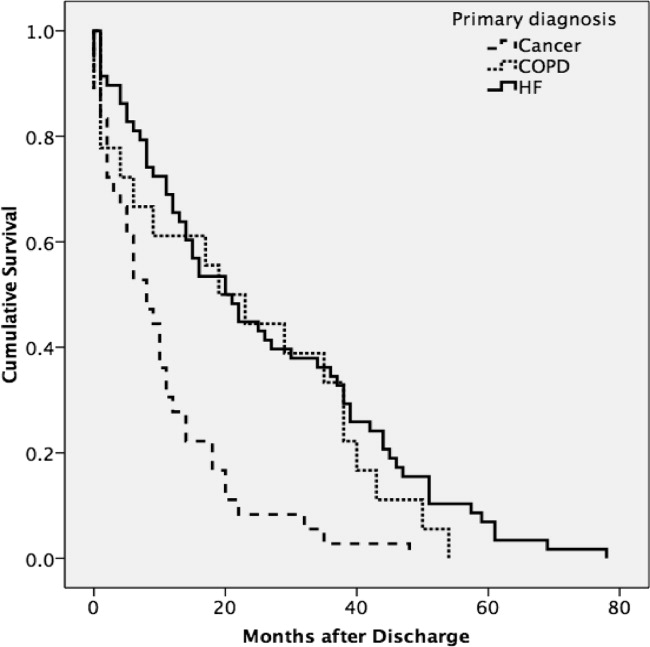

Primary Diagnosis, Symptom Burden, and Survival Time

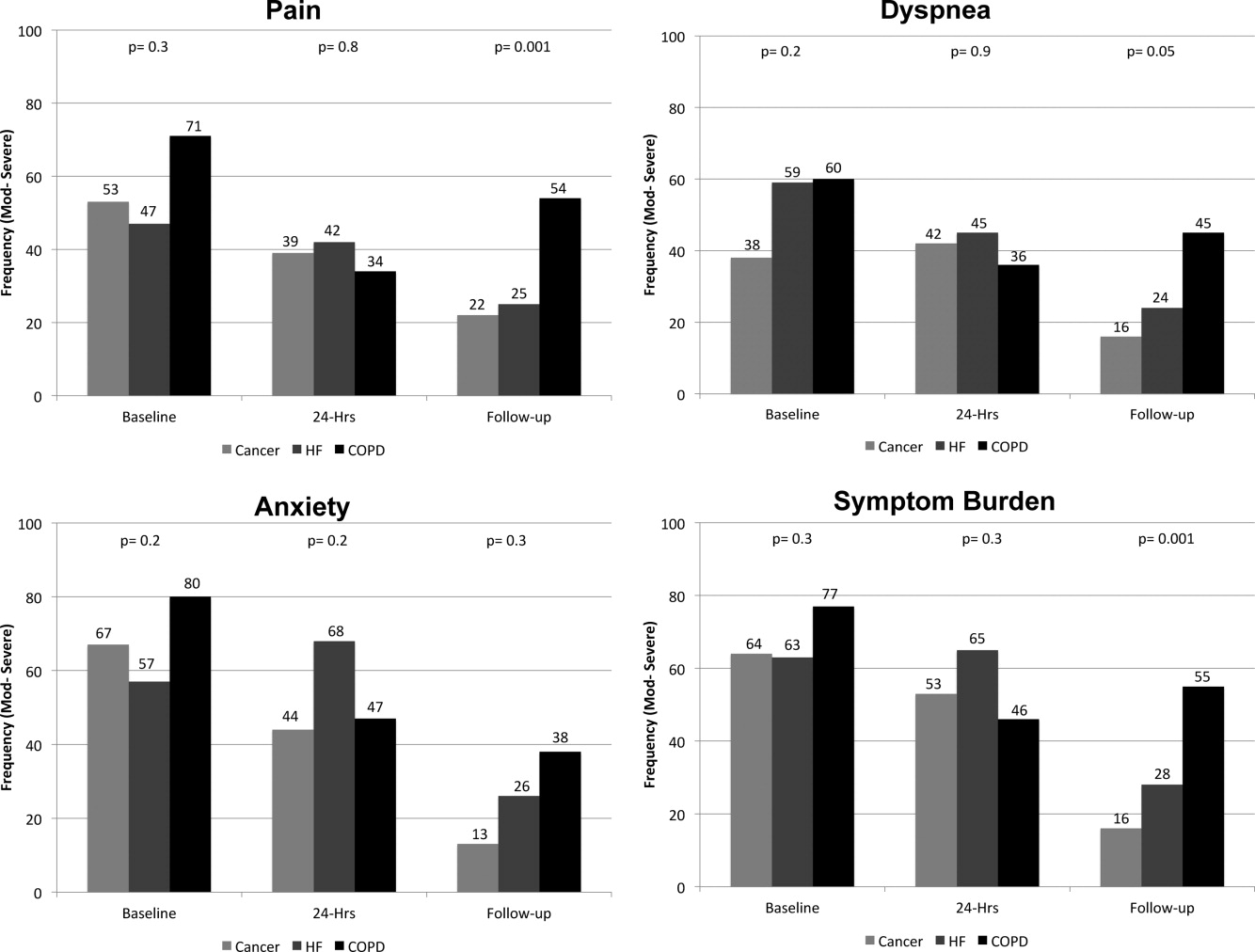

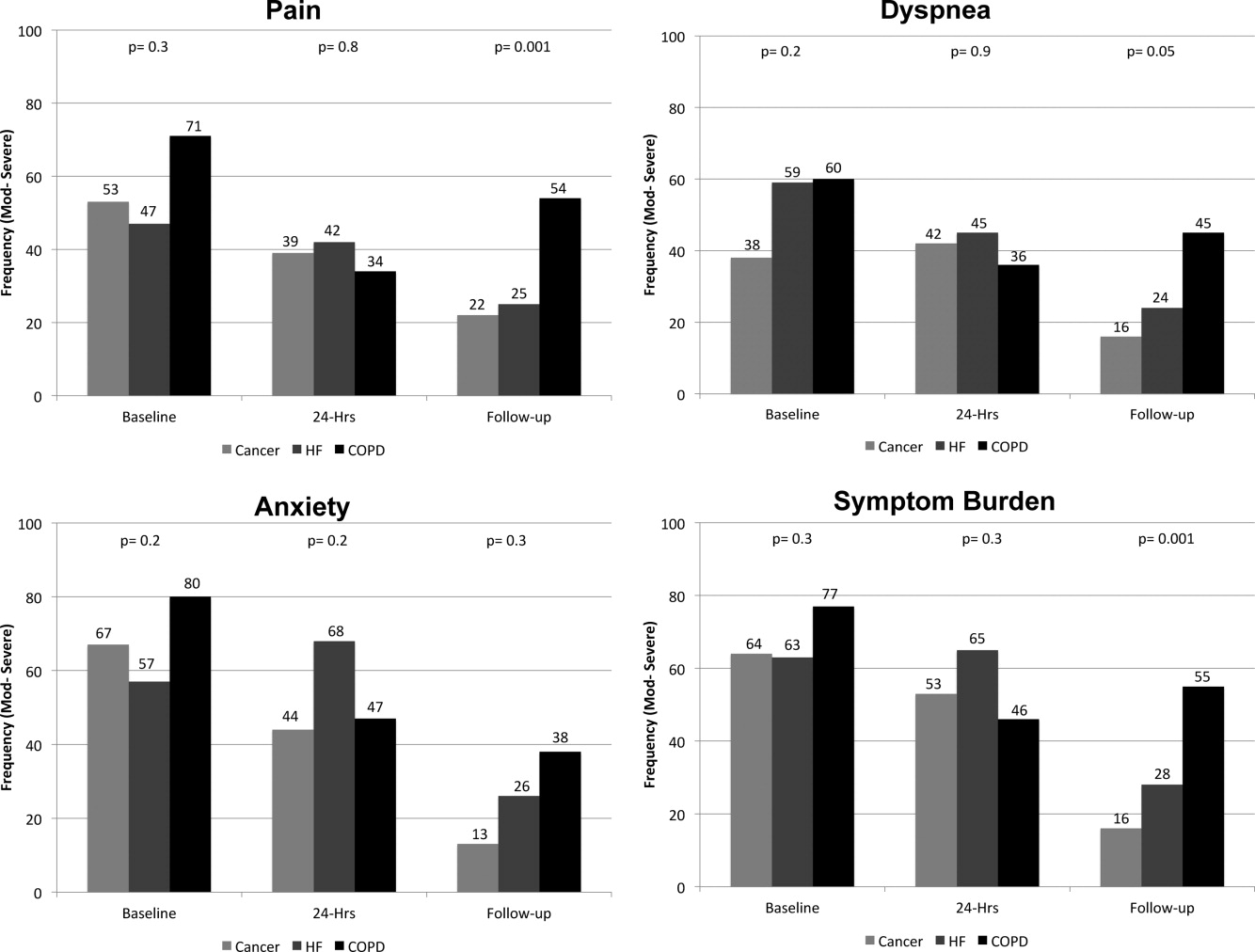

A total of 75% of patients were identified by the National Death Index to have died between hospital discharge and December 2007, of which 47% had died within 12 months after discharge. KaplanMeier survival curves (Figure 2) revealed a significant difference (MantelCox: 2 = 19.3; df = 1; P = 0.0001) in survival time, with patients diagnosed with COPD (median = 19.0 months; 95% CI = 6.5, 31.5) and HF (median = 20.0 months; 95% CI = 12.5, 27.5) having a longer survival than those with cancer (median = 8.0 months; 95% CI = 4.1, 11.9).

We also examined the relationship between symptom burden and survival time. KaplanMeier survival curves revealed no significant difference (MantelCox: 2 = 0.2; P = 0.6) in the survival time of patients classified with a symptom burden of none/moderate (median = 15.0 months; 95% CI = 8.8, 21.2) or moderate/severe (median = 14.0 months; 95% CI = 2.6, 25.4).

DISCUSSION

In our sample of older inpatients diagnosed with cancer, HF, and COPD, a large proportion reported moderate‐to‐severe levels of pain, dyspnea, and anxiety at baseline and follow‐up. When combined, these levels represent a considerable symptom burden, with over three‐quarters of participants reporting 2 to 3 symptoms at a moderate/severe level at baseline. While symptom scores decreased at 24‐hours and 2‐week follow‐up, symptom burden remained high, with almost half of the participants reporting 23 symptoms at a moderate‐to‐severe level at 24‐hour assessment and a large minority reporting moderate‐to‐severe symptoms at follow‐up. A higher percentage of patients with COPD reported moderate‐to‐severe pain, dyspnea, and overall symptom burden at follow‐up than participants with cancer or HF who reported a similar symptom burden. We also found that patients with probable depression were more likely to have a significant symptom burden at follow‐up. These findings highlight the need to routinely assess and treat symptoms over time, including depression, and especially in patients with COPD. While we found that hospital care was seemingly effective in improving symptoms, they persist at distressing levels in many patients.

Few studies have assessed the severity of symptoms over time. One study that did, examined symptom severity among community‐based elders diagnosed with HF and COPD.6 At baseline, these participants had a lower prevalence of moderate‐to‐severe symptoms than the hospitalized patients enrolled in our study, a finding that would be anticipated, as they may not have been as ill. However, symptom severity persisted in the community‐based subjects and, in some cases, worsened over the 22‐month assessment period for pain (HF = 20% vs 42%; COPD = 27% vs 20%), dyspnea (HF = 19% vs 29%; COPD = 66% vs 76%), and anxiety (HF = 2% vs 12%; COPD = 32% vs 23%).6 In contrast, while our subjects with a primary diagnosis of HF and COPD had a higher prevalence of moderate‐to‐severe symptoms at baseline, they did experience an improvement in the severity of pain, dyspnea, and anxiety at the 2‐week follow‐up assessment. However, despite a decrease in the prevalence of moderate‐to‐severe symptoms from baseline to follow‐up, a high symptom burden persisted for many patients, particularly for those diagnosed with COPD and those with probable depression at baseline. The severity of a patient's symptoms can have a profound negative effect on health status and quality of life.14 Findings from these studies suggest that symptoms are currently not being adequately managed, and highlight an urgent need to develop coordinated strategies and systems that focus on improving the management of symptoms, including depression, over time.6

We also found that subjects recruited for this study had advanced disease, evidenced by the fact that nearly half died within 12 months. We did not use specific prognostic indices or severity of illness criteria for recruiting subjects and simply approached patients admitted with one of the target diagnoses. Our study suggests that targeting these patients for routine symptom assessment and management, including for palliative care, would be a reasonable approach given the high symptom burden and relatively high mortality at 1 year.

Interpretation of these findings should be mitigated by the following limitations. Because of our setting, our findings may not be generalizable to all patients with cancer, HF, and COPD. However, our subjects were admitted to general medical and cardiology services, and had common conditions, and therefore are likely similar to those presenting to other hospitals. We relied on self‐report measures to assess severity of symptoms. Patient self‐report, while potentially subject to imprecision due to poor recall and social demand biases, is considered the gold standard for symptom assessment.15 Finally, 2‐week follow‐up is relatively short, and it is possible that symptoms may have improved had we assessed them over a longer period. The longitudinal study of elders in the community that followed subjects over 22 months found that, for many patients, symptoms worsened over time and nearly half of our subjects died at 12 months, suggesting that longer follow‐up would have been unlikely to show improvement in symptoms.6

A significant minority of participants reported a substantial, persistent symptom burden, yet all symptoms assessed in our study are potentially modifiable. Recognizing and treating symptoms can be achieved through the use of targeted interventions.6 Because symptoms can occur in clusters, successful treatment of 1 symptom may also help to improve other symptoms.1 The large number of participants reporting moderate‐to‐severe levels of symptom burden at 2 weeks after discharge highlights an unmet need for improved symptom control in the outpatient setting. Unfortunately, while evidence exists for managing pain in patients with cancer, such evidence‐based practices are lacking for the management of pain and other symptoms in patients with HF and COPD. Some symptoms may require specific, disease‐oriented management. However, many symptoms may be due to common comorbidities, such as pain from degenerative joint disease, that may likely respond to proven treatments.16

Our study confirmed the significant burden of symptoms experienced by patients with serious illness and demonstrated that patients with COPD report as much symptom burden as patients with cancer and HF, if not more. While symptom severity improved over the course of the hospitalization and follow‐up, a large percentage of patients reported significant symptom burden at follow‐up. Depression was also common in these patients. Because these symptoms diminish quality of life, routine assessment and management of these symptoms is critical for improving the quality of care provided to these patients. Additional research on the best approaches to manage symptoms, including medications, interventions, and structures of care, could further improve care.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the patients who participated in this study. They thank Joanne Batt, Wren Levenberg, and Emily Philipps for their expert help as research assistants. They also thank Harold Collard, MD, for providing valuable feedback on the manuscript. Data obtained from the National Death Index assisted us in meeting our study objectives. Steven Pantilat had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

- ,,.Symptom clusters: the new frontier in symptom management research.J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr.2004(32):17–21.

- .Symptom burden: multiple symptoms and their impact as patient‐reported outcomes.J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr.2007(37):16–21.

- ,,.A comparison of symptom prevalence in far advanced cancer, AIDS, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and renal disease.J Pain Symptom Manage.2006;31(1):58–69.

- ,,, et al.Comparing three life‐limiting diseases: does diagnosis matter or is sick, sick?J Pain Symptom Manage.2011;42(3):331–341.

- ,,,,,.Deaths: final data for 2006.Natl Vital Stat Rep.2009;57(14):1–134.

- ,,,,,.Range and severity of symptoms over time among older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure.Arch Intern Med.2007;167(22):2503–2508.

- ,,,.Living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a survey of patients' knowledge and attitudes.Respir Med.2009;103(7):1004–1012.

- ,,,,.The symptom burden of seriously ill hospitalized patients. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcome and Risks of Treatment.J Pain Symptom Manage.1999;17(4):248–255.

- ,,, et al.Relationship between early physician follow‐up and 30‐day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure.JAMA.2010;303(17):1716–1722.

- ,,,.Hospital‐based palliative medicine consultation: a randomized controlled trial.Arch Intern Med.2010;170(22):2038–2040.

- ,,,,.Studies of illness in the aged. The Index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function.JAMA.1963;185:914–919.

- ,,,.Screening for late life depression: cut‐off scores for the Geriatric Depression Scale and the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia among Japanese subjects.Int J Geriatr Psychiatry.2003;18(6):498–505.

- ,.Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations.J Am Stat Assoc.1958;53(282):457–481.

- ,,.End stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.Pneumonol Alergol Pol.2009;77(2):173–179.

- ,,,.Relationship between social desirability and self‐report in chronic pain patients.Clin J Pain.1995;11(3):189–193.

- ,,,.Etiology and severity of pain among outpatients living with HF.J Card Fail.2010;16(8):S88.

The frequency and severity of symptoms among older hospitalized patients with chronic illnesses can have a profound negative impact on their quality of life.1, 2 Nonetheless, research examining the prevalence and management of symptoms has focused predominantly on cancer patients.3 Few studies have included patients with other serious conditions such as heart failure (HF) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),3, 4 which are very common and are major causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States.5 One longitudinal assessment of symptom severity among a group of community‐based older adults diagnosed with COPD and HF reported high rates of moderate‐to‐severe pain, dyspnea, and anxiety at baseline and follow‐up, as long as 22 months later.6 Persistent symptoms over time can have an adverse effect on an individual's physical and emotional well‐being, and highlight opportunities to improve care.3, 7 Understanding patterns of symptom change over time is a key first step in developing systems to improve quality of care for people with chronic illness.

Among hospitalized patients, pain, dyspnea, anxiety, and depression cause the greatest symptom burden, accounting for 67% of all symptoms classified as moderate to severe.8 While assessment and management of symptoms may be the reason for admission to the hospital and the focus of inpatient care, this focus may not persist after discharge, leaving patients with significant symptoms that can diminish quality of life and contribute to readmission.9 We studied a cohort of older inpatients with serious illness over time in order to determine the prevalence, severity, burden, and predictors of symptoms during the course of hospitalization and at 2 weeks after discharge.

METHODS

Setting

The study was undertaken at a large academic medical center in San Francisco.

Subjects

Participants were patients 65 years or older admitted to the medicine or cardiology services with a primary diagnosis of cancer, COPD, or HF. Participants were required to be fully oriented and English‐speaking. Patients gave written informed consent to participate. The Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco, approved this study (H8695‐35172‐01).

Data Collection

Data collection was undertaken from March 2001 to December 2003. This study was part of a prospective, clinical trial that compared a proactive palliative medicine consultation with usual hospital care, and has been previously described.10 Upon study enrollment, all patients completed the Inpatient Care Survey. The survey asked participants about demographic information such as date of birth, sex, education level, race, and marital status. The survey instruments also included the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) index and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS‐15). Each weekday during hospitalization, a trained research assistant asked patients to report their worst symptom level for pain, dyspnea, and anxiety in the past 24 hours using a 010 numeric rating scale, where 0 was none and 10 was the worst you can imagine. We further characterized scores into categories such that 0 was defined as none, 13 as mild, 46 as moderate, and 710 as severe. A follow‐up telephone survey, 2 weeks after discharge, reassessed patients' worst symptom levels in the past 24 hours for pain, dyspnea, and anxiety.

We also generated a composite score of symptoms to report a symptom burden score for these 3 symptoms. Using the categories of symptom severity, we assigned a score of 0 for none, 1 for mild, 2 for moderate, and 3 for severe. We summed the assigned scores for all 3 symptoms for each subject to generate a symptom burden score as follows: no symptom burden (0), mild symptom burden (13), moderate symptom burden (46), and severe symptom burden (79). In this scale, a moderate symptom burden would mean that a subject reported having at least 1 symptom at a moderate or severe level, with at least 1 other symptom present. A severe symptom burden would require the presence of all 3 symptoms, with at least 1 at a severe level.

We reviewed patient charts to assess severity of patient illness upon admission. For cancer, we recorded type; for COPD, we noted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1); and for HF, we recorded the ejection fraction. We also queried the National Death Index to get vital statistics on all subjects.

Data Preparation

The IADL asks patients to report whether they can perform 13 daily living skills without help, with some help, or were unable to complete tasks.11 Subjects who reported needing at least some help with any of the 13 items were categorized as dependent. The GDS‐15 is a widely used, validated 15‐item scale for assessing depressive mood in the elderly.12 Scores for the GDS‐15 range from 0 to 15, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms. Based on previous research, we categorized patients as either not depressed (05) or having probable depression (6 or more).12

Statistical Analysis

Because our clinical trial had no impact on care or symptoms, we combined intervention and usual care patients for this analysis of symptom severity. Descriptive statistics, such as frequencies, means, standard deviations (SDs), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to examine the distribution of measures. Chi‐square (2) analysis was undertaken to examine bivariate associations between categorical variables. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was undertaken to examine associations between categorical and continuous variables. Multivariate logistic regression was used to examine predictors of symptom burden at follow‐up, including patient characteristics that were significant to P 0.10 in bivariate analysis. We used KaplanMeier survival curves to examine the relationship between primary diagnosis and mortality, and assessed statistical significance using log‐rank tests (MantelCox).13 The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Mac (version 17; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL; March 11, 2009) was used to analyze these data.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

A total of 150 patients enrolled in the study. The mean length of stay was 5.4 days (SD: 5.6; range: 147 days). HF was the most common primary diagnosis (46.7%, n = 70) with 48% (n = 34) having an ejection fraction of 45% or less (mean = 43%; SD: 22); followed by cancer (30%, n = 45) with the most common type being prostate (18%, n = 8), lung (13%, n = 6), and breast (13%, n = 6); and COPD (23%, n = 35) with an average FEV1 of 1.5 L (SD: 0.94; range: 0.503.9). The mean age was 77 years (SD: 7.9; range: 6596 years). The majority of participants were men (56%, n = 83) and white (73%, n = 108), with the most being either married/partnered (43%, n = 64) or divorced/widowed (44%, n = 66). The IADL identified almost two‐thirds of participants as dependent (62%, n = 94). The GDS‐15 categorized three‐quarters of participants (n = 118) as not depressed. The only significant association between participant characteristics and their primary diagnosis was for the IADL index (Table 1), with significantly more (2 = 6.3; P = 0.04) patients with HF categorized as being dependent (72%).

| Characteristics | Primary Diagnosis | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer n = 44 | HF n = 70 | COPD n = 35 | |||

| |||||

| Length of stay | (Mean days) | 5.4 | 4.7 | 6.5 | 0.3 |

| Age | (Mean years) | 76 | 78 | 76 | 0.3 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 47% | 37% | 57% | 0.1 | |

| Marital status | 0.2 | ||||

| Single | 16 | 9 | 17 | ||

| Married/partnered | 51 | 45 | 29 | ||

| Divorced/widowed | 33 | 46 | 54 | ||

| Race | |||||

| White | 89 | 64 | 69 | 0.1 | |

| Black/African American | 7 | 21 | 23 | ||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 5 | 10 | 9 | ||

| Other | 0 | 4 | 0 | ||

| IADL | |||||

| Dependent | 49 | 72 | 60 | 0.04 | |

| GDS‐15 | |||||

| Probable depression | 18 | 22 | 21 | 0.9 | |

Frequency and Severity of Symptoms

On average, the postdischarge follow‐up assessment was undertaken 24 days (median = 21.0; SD: 17.9; range: 7140 days) after the baseline assessment and 20 days after discharge (median = 15; SD: 17.0; range: 4139). At baseline, a large proportion of participants reported symptoms at a moderate‐to‐severe level for pain (54%, n = 81), dyspnea (53%, n = 79), and anxiety (63%, n = 94). The majority of patients (64%, n = 96) reported having 2 or more symptoms at a moderate‐to‐severe level and one quarter (27%, n = 41) had 3 symptoms at a moderate‐to‐severe level. While the frequency of moderate‐to‐severe symptoms decreased at the 24‐hour hospital assessment (pain = 42%, dyspnea = 45%, anxiety = 55%) and again at 2‐week follow‐up (pain = 28%, dyspnea = 27%, anxiety = 25%), a substantial symptom burden persisted with 30% (n = 36) of patients having moderate‐to‐severe levels at 2‐week follow‐up. Overall there were no differences between primary diagnosis and the frequency of symptoms at baseline or 24‐hour hospital assessment (Figure 1). However at follow‐up, those diagnosed with COPD were more likely to report moderate/severe pain (54%; 2 = 22.0; P < 0.001), dyspnea (45%; 2 = 9.3; P = 0.05), and overall symptom burden (55%; 2 = 25.9; P < 0.001) than those with cancer (pain = 22%, dyspnea = 16%, symptom burden = 16%) or HF (pain = 25%, dyspnea = 24%, symptom burden = 28%).

As symptom burden was our composite score for pain, dyspnea, and anxiety, we were interested in identifying variables in addition to primary diagnosis that might be associated with symptom burden at follow‐up. Bivariate analysis revealed that there was no significant association between symptom burden and age (2 = 1.5; P = 0.5), gender (2 = 1.3; P = 0.3), length of stay (2 = 0.4; P = 0.8), and (IADL) level of independence (2 = 0.3; P = 0.6). However, those with probable depression were more likely (2 = 11.9; P = 0.001) to have a moderate/severe symptom burden (62%, n = 13), compared to those with no depression (24%, n = 23). After adjusting for severity of symptom burden at baseline, multivariate logistic regression revealed that primary diagnosis (P = 0.01) and probable depression (OR = 4.9; 95% CI = 1.6, 14.9; P = 0.005) were associated with symptom severity. Patients with COPD had greater odds (OR = 7.0; 95% CI = 1.9, 26.2; P = 0.002) of moderate/severe symptom burden than those with cancer, while those with HF did not (OR = 2.3; 95% CI = 0.7, 7.7; P = 0.16). There was significant interaction between primary diagnosis and depression (P = 0.2).

Primary Diagnosis, Symptom Burden, and Survival Time

A total of 75% of patients were identified by the National Death Index to have died between hospital discharge and December 2007, of which 47% had died within 12 months after discharge. KaplanMeier survival curves (Figure 2) revealed a significant difference (MantelCox: 2 = 19.3; df = 1; P = 0.0001) in survival time, with patients diagnosed with COPD (median = 19.0 months; 95% CI = 6.5, 31.5) and HF (median = 20.0 months; 95% CI = 12.5, 27.5) having a longer survival than those with cancer (median = 8.0 months; 95% CI = 4.1, 11.9).

We also examined the relationship between symptom burden and survival time. KaplanMeier survival curves revealed no significant difference (MantelCox: 2 = 0.2; P = 0.6) in the survival time of patients classified with a symptom burden of none/moderate (median = 15.0 months; 95% CI = 8.8, 21.2) or moderate/severe (median = 14.0 months; 95% CI = 2.6, 25.4).

DISCUSSION

In our sample of older inpatients diagnosed with cancer, HF, and COPD, a large proportion reported moderate‐to‐severe levels of pain, dyspnea, and anxiety at baseline and follow‐up. When combined, these levels represent a considerable symptom burden, with over three‐quarters of participants reporting 2 to 3 symptoms at a moderate/severe level at baseline. While symptom scores decreased at 24‐hours and 2‐week follow‐up, symptom burden remained high, with almost half of the participants reporting 23 symptoms at a moderate‐to‐severe level at 24‐hour assessment and a large minority reporting moderate‐to‐severe symptoms at follow‐up. A higher percentage of patients with COPD reported moderate‐to‐severe pain, dyspnea, and overall symptom burden at follow‐up than participants with cancer or HF who reported a similar symptom burden. We also found that patients with probable depression were more likely to have a significant symptom burden at follow‐up. These findings highlight the need to routinely assess and treat symptoms over time, including depression, and especially in patients with COPD. While we found that hospital care was seemingly effective in improving symptoms, they persist at distressing levels in many patients.

Few studies have assessed the severity of symptoms over time. One study that did, examined symptom severity among community‐based elders diagnosed with HF and COPD.6 At baseline, these participants had a lower prevalence of moderate‐to‐severe symptoms than the hospitalized patients enrolled in our study, a finding that would be anticipated, as they may not have been as ill. However, symptom severity persisted in the community‐based subjects and, in some cases, worsened over the 22‐month assessment period for pain (HF = 20% vs 42%; COPD = 27% vs 20%), dyspnea (HF = 19% vs 29%; COPD = 66% vs 76%), and anxiety (HF = 2% vs 12%; COPD = 32% vs 23%).6 In contrast, while our subjects with a primary diagnosis of HF and COPD had a higher prevalence of moderate‐to‐severe symptoms at baseline, they did experience an improvement in the severity of pain, dyspnea, and anxiety at the 2‐week follow‐up assessment. However, despite a decrease in the prevalence of moderate‐to‐severe symptoms from baseline to follow‐up, a high symptom burden persisted for many patients, particularly for those diagnosed with COPD and those with probable depression at baseline. The severity of a patient's symptoms can have a profound negative effect on health status and quality of life.14 Findings from these studies suggest that symptoms are currently not being adequately managed, and highlight an urgent need to develop coordinated strategies and systems that focus on improving the management of symptoms, including depression, over time.6

We also found that subjects recruited for this study had advanced disease, evidenced by the fact that nearly half died within 12 months. We did not use specific prognostic indices or severity of illness criteria for recruiting subjects and simply approached patients admitted with one of the target diagnoses. Our study suggests that targeting these patients for routine symptom assessment and management, including for palliative care, would be a reasonable approach given the high symptom burden and relatively high mortality at 1 year.

Interpretation of these findings should be mitigated by the following limitations. Because of our setting, our findings may not be generalizable to all patients with cancer, HF, and COPD. However, our subjects were admitted to general medical and cardiology services, and had common conditions, and therefore are likely similar to those presenting to other hospitals. We relied on self‐report measures to assess severity of symptoms. Patient self‐report, while potentially subject to imprecision due to poor recall and social demand biases, is considered the gold standard for symptom assessment.15 Finally, 2‐week follow‐up is relatively short, and it is possible that symptoms may have improved had we assessed them over a longer period. The longitudinal study of elders in the community that followed subjects over 22 months found that, for many patients, symptoms worsened over time and nearly half of our subjects died at 12 months, suggesting that longer follow‐up would have been unlikely to show improvement in symptoms.6

A significant minority of participants reported a substantial, persistent symptom burden, yet all symptoms assessed in our study are potentially modifiable. Recognizing and treating symptoms can be achieved through the use of targeted interventions.6 Because symptoms can occur in clusters, successful treatment of 1 symptom may also help to improve other symptoms.1 The large number of participants reporting moderate‐to‐severe levels of symptom burden at 2 weeks after discharge highlights an unmet need for improved symptom control in the outpatient setting. Unfortunately, while evidence exists for managing pain in patients with cancer, such evidence‐based practices are lacking for the management of pain and other symptoms in patients with HF and COPD. Some symptoms may require specific, disease‐oriented management. However, many symptoms may be due to common comorbidities, such as pain from degenerative joint disease, that may likely respond to proven treatments.16

Our study confirmed the significant burden of symptoms experienced by patients with serious illness and demonstrated that patients with COPD report as much symptom burden as patients with cancer and HF, if not more. While symptom severity improved over the course of the hospitalization and follow‐up, a large percentage of patients reported significant symptom burden at follow‐up. Depression was also common in these patients. Because these symptoms diminish quality of life, routine assessment and management of these symptoms is critical for improving the quality of care provided to these patients. Additional research on the best approaches to manage symptoms, including medications, interventions, and structures of care, could further improve care.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the patients who participated in this study. They thank Joanne Batt, Wren Levenberg, and Emily Philipps for their expert help as research assistants. They also thank Harold Collard, MD, for providing valuable feedback on the manuscript. Data obtained from the National Death Index assisted us in meeting our study objectives. Steven Pantilat had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The frequency and severity of symptoms among older hospitalized patients with chronic illnesses can have a profound negative impact on their quality of life.1, 2 Nonetheless, research examining the prevalence and management of symptoms has focused predominantly on cancer patients.3 Few studies have included patients with other serious conditions such as heart failure (HF) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),3, 4 which are very common and are major causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States.5 One longitudinal assessment of symptom severity among a group of community‐based older adults diagnosed with COPD and HF reported high rates of moderate‐to‐severe pain, dyspnea, and anxiety at baseline and follow‐up, as long as 22 months later.6 Persistent symptoms over time can have an adverse effect on an individual's physical and emotional well‐being, and highlight opportunities to improve care.3, 7 Understanding patterns of symptom change over time is a key first step in developing systems to improve quality of care for people with chronic illness.

Among hospitalized patients, pain, dyspnea, anxiety, and depression cause the greatest symptom burden, accounting for 67% of all symptoms classified as moderate to severe.8 While assessment and management of symptoms may be the reason for admission to the hospital and the focus of inpatient care, this focus may not persist after discharge, leaving patients with significant symptoms that can diminish quality of life and contribute to readmission.9 We studied a cohort of older inpatients with serious illness over time in order to determine the prevalence, severity, burden, and predictors of symptoms during the course of hospitalization and at 2 weeks after discharge.

METHODS

Setting

The study was undertaken at a large academic medical center in San Francisco.

Subjects

Participants were patients 65 years or older admitted to the medicine or cardiology services with a primary diagnosis of cancer, COPD, or HF. Participants were required to be fully oriented and English‐speaking. Patients gave written informed consent to participate. The Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco, approved this study (H8695‐35172‐01).

Data Collection

Data collection was undertaken from March 2001 to December 2003. This study was part of a prospective, clinical trial that compared a proactive palliative medicine consultation with usual hospital care, and has been previously described.10 Upon study enrollment, all patients completed the Inpatient Care Survey. The survey asked participants about demographic information such as date of birth, sex, education level, race, and marital status. The survey instruments also included the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) index and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS‐15). Each weekday during hospitalization, a trained research assistant asked patients to report their worst symptom level for pain, dyspnea, and anxiety in the past 24 hours using a 010 numeric rating scale, where 0 was none and 10 was the worst you can imagine. We further characterized scores into categories such that 0 was defined as none, 13 as mild, 46 as moderate, and 710 as severe. A follow‐up telephone survey, 2 weeks after discharge, reassessed patients' worst symptom levels in the past 24 hours for pain, dyspnea, and anxiety.

We also generated a composite score of symptoms to report a symptom burden score for these 3 symptoms. Using the categories of symptom severity, we assigned a score of 0 for none, 1 for mild, 2 for moderate, and 3 for severe. We summed the assigned scores for all 3 symptoms for each subject to generate a symptom burden score as follows: no symptom burden (0), mild symptom burden (13), moderate symptom burden (46), and severe symptom burden (79). In this scale, a moderate symptom burden would mean that a subject reported having at least 1 symptom at a moderate or severe level, with at least 1 other symptom present. A severe symptom burden would require the presence of all 3 symptoms, with at least 1 at a severe level.

We reviewed patient charts to assess severity of patient illness upon admission. For cancer, we recorded type; for COPD, we noted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1); and for HF, we recorded the ejection fraction. We also queried the National Death Index to get vital statistics on all subjects.

Data Preparation

The IADL asks patients to report whether they can perform 13 daily living skills without help, with some help, or were unable to complete tasks.11 Subjects who reported needing at least some help with any of the 13 items were categorized as dependent. The GDS‐15 is a widely used, validated 15‐item scale for assessing depressive mood in the elderly.12 Scores for the GDS‐15 range from 0 to 15, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms. Based on previous research, we categorized patients as either not depressed (05) or having probable depression (6 or more).12

Statistical Analysis

Because our clinical trial had no impact on care or symptoms, we combined intervention and usual care patients for this analysis of symptom severity. Descriptive statistics, such as frequencies, means, standard deviations (SDs), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to examine the distribution of measures. Chi‐square (2) analysis was undertaken to examine bivariate associations between categorical variables. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was undertaken to examine associations between categorical and continuous variables. Multivariate logistic regression was used to examine predictors of symptom burden at follow‐up, including patient characteristics that were significant to P 0.10 in bivariate analysis. We used KaplanMeier survival curves to examine the relationship between primary diagnosis and mortality, and assessed statistical significance using log‐rank tests (MantelCox).13 The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Mac (version 17; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL; March 11, 2009) was used to analyze these data.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

A total of 150 patients enrolled in the study. The mean length of stay was 5.4 days (SD: 5.6; range: 147 days). HF was the most common primary diagnosis (46.7%, n = 70) with 48% (n = 34) having an ejection fraction of 45% or less (mean = 43%; SD: 22); followed by cancer (30%, n = 45) with the most common type being prostate (18%, n = 8), lung (13%, n = 6), and breast (13%, n = 6); and COPD (23%, n = 35) with an average FEV1 of 1.5 L (SD: 0.94; range: 0.503.9). The mean age was 77 years (SD: 7.9; range: 6596 years). The majority of participants were men (56%, n = 83) and white (73%, n = 108), with the most being either married/partnered (43%, n = 64) or divorced/widowed (44%, n = 66). The IADL identified almost two‐thirds of participants as dependent (62%, n = 94). The GDS‐15 categorized three‐quarters of participants (n = 118) as not depressed. The only significant association between participant characteristics and their primary diagnosis was for the IADL index (Table 1), with significantly more (2 = 6.3; P = 0.04) patients with HF categorized as being dependent (72%).

| Characteristics | Primary Diagnosis | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer n = 44 | HF n = 70 | COPD n = 35 | |||

| |||||

| Length of stay | (Mean days) | 5.4 | 4.7 | 6.5 | 0.3 |

| Age | (Mean years) | 76 | 78 | 76 | 0.3 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 47% | 37% | 57% | 0.1 | |

| Marital status | 0.2 | ||||

| Single | 16 | 9 | 17 | ||

| Married/partnered | 51 | 45 | 29 | ||

| Divorced/widowed | 33 | 46 | 54 | ||

| Race | |||||

| White | 89 | 64 | 69 | 0.1 | |

| Black/African American | 7 | 21 | 23 | ||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 5 | 10 | 9 | ||

| Other | 0 | 4 | 0 | ||

| IADL | |||||

| Dependent | 49 | 72 | 60 | 0.04 | |

| GDS‐15 | |||||

| Probable depression | 18 | 22 | 21 | 0.9 | |

Frequency and Severity of Symptoms

On average, the postdischarge follow‐up assessment was undertaken 24 days (median = 21.0; SD: 17.9; range: 7140 days) after the baseline assessment and 20 days after discharge (median = 15; SD: 17.0; range: 4139). At baseline, a large proportion of participants reported symptoms at a moderate‐to‐severe level for pain (54%, n = 81), dyspnea (53%, n = 79), and anxiety (63%, n = 94). The majority of patients (64%, n = 96) reported having 2 or more symptoms at a moderate‐to‐severe level and one quarter (27%, n = 41) had 3 symptoms at a moderate‐to‐severe level. While the frequency of moderate‐to‐severe symptoms decreased at the 24‐hour hospital assessment (pain = 42%, dyspnea = 45%, anxiety = 55%) and again at 2‐week follow‐up (pain = 28%, dyspnea = 27%, anxiety = 25%), a substantial symptom burden persisted with 30% (n = 36) of patients having moderate‐to‐severe levels at 2‐week follow‐up. Overall there were no differences between primary diagnosis and the frequency of symptoms at baseline or 24‐hour hospital assessment (Figure 1). However at follow‐up, those diagnosed with COPD were more likely to report moderate/severe pain (54%; 2 = 22.0; P < 0.001), dyspnea (45%; 2 = 9.3; P = 0.05), and overall symptom burden (55%; 2 = 25.9; P < 0.001) than those with cancer (pain = 22%, dyspnea = 16%, symptom burden = 16%) or HF (pain = 25%, dyspnea = 24%, symptom burden = 28%).

As symptom burden was our composite score for pain, dyspnea, and anxiety, we were interested in identifying variables in addition to primary diagnosis that might be associated with symptom burden at follow‐up. Bivariate analysis revealed that there was no significant association between symptom burden and age (2 = 1.5; P = 0.5), gender (2 = 1.3; P = 0.3), length of stay (2 = 0.4; P = 0.8), and (IADL) level of independence (2 = 0.3; P = 0.6). However, those with probable depression were more likely (2 = 11.9; P = 0.001) to have a moderate/severe symptom burden (62%, n = 13), compared to those with no depression (24%, n = 23). After adjusting for severity of symptom burden at baseline, multivariate logistic regression revealed that primary diagnosis (P = 0.01) and probable depression (OR = 4.9; 95% CI = 1.6, 14.9; P = 0.005) were associated with symptom severity. Patients with COPD had greater odds (OR = 7.0; 95% CI = 1.9, 26.2; P = 0.002) of moderate/severe symptom burden than those with cancer, while those with HF did not (OR = 2.3; 95% CI = 0.7, 7.7; P = 0.16). There was significant interaction between primary diagnosis and depression (P = 0.2).

Primary Diagnosis, Symptom Burden, and Survival Time

A total of 75% of patients were identified by the National Death Index to have died between hospital discharge and December 2007, of which 47% had died within 12 months after discharge. KaplanMeier survival curves (Figure 2) revealed a significant difference (MantelCox: 2 = 19.3; df = 1; P = 0.0001) in survival time, with patients diagnosed with COPD (median = 19.0 months; 95% CI = 6.5, 31.5) and HF (median = 20.0 months; 95% CI = 12.5, 27.5) having a longer survival than those with cancer (median = 8.0 months; 95% CI = 4.1, 11.9).

We also examined the relationship between symptom burden and survival time. KaplanMeier survival curves revealed no significant difference (MantelCox: 2 = 0.2; P = 0.6) in the survival time of patients classified with a symptom burden of none/moderate (median = 15.0 months; 95% CI = 8.8, 21.2) or moderate/severe (median = 14.0 months; 95% CI = 2.6, 25.4).

DISCUSSION

In our sample of older inpatients diagnosed with cancer, HF, and COPD, a large proportion reported moderate‐to‐severe levels of pain, dyspnea, and anxiety at baseline and follow‐up. When combined, these levels represent a considerable symptom burden, with over three‐quarters of participants reporting 2 to 3 symptoms at a moderate/severe level at baseline. While symptom scores decreased at 24‐hours and 2‐week follow‐up, symptom burden remained high, with almost half of the participants reporting 23 symptoms at a moderate‐to‐severe level at 24‐hour assessment and a large minority reporting moderate‐to‐severe symptoms at follow‐up. A higher percentage of patients with COPD reported moderate‐to‐severe pain, dyspnea, and overall symptom burden at follow‐up than participants with cancer or HF who reported a similar symptom burden. We also found that patients with probable depression were more likely to have a significant symptom burden at follow‐up. These findings highlight the need to routinely assess and treat symptoms over time, including depression, and especially in patients with COPD. While we found that hospital care was seemingly effective in improving symptoms, they persist at distressing levels in many patients.

Few studies have assessed the severity of symptoms over time. One study that did, examined symptom severity among community‐based elders diagnosed with HF and COPD.6 At baseline, these participants had a lower prevalence of moderate‐to‐severe symptoms than the hospitalized patients enrolled in our study, a finding that would be anticipated, as they may not have been as ill. However, symptom severity persisted in the community‐based subjects and, in some cases, worsened over the 22‐month assessment period for pain (HF = 20% vs 42%; COPD = 27% vs 20%), dyspnea (HF = 19% vs 29%; COPD = 66% vs 76%), and anxiety (HF = 2% vs 12%; COPD = 32% vs 23%).6 In contrast, while our subjects with a primary diagnosis of HF and COPD had a higher prevalence of moderate‐to‐severe symptoms at baseline, they did experience an improvement in the severity of pain, dyspnea, and anxiety at the 2‐week follow‐up assessment. However, despite a decrease in the prevalence of moderate‐to‐severe symptoms from baseline to follow‐up, a high symptom burden persisted for many patients, particularly for those diagnosed with COPD and those with probable depression at baseline. The severity of a patient's symptoms can have a profound negative effect on health status and quality of life.14 Findings from these studies suggest that symptoms are currently not being adequately managed, and highlight an urgent need to develop coordinated strategies and systems that focus on improving the management of symptoms, including depression, over time.6

We also found that subjects recruited for this study had advanced disease, evidenced by the fact that nearly half died within 12 months. We did not use specific prognostic indices or severity of illness criteria for recruiting subjects and simply approached patients admitted with one of the target diagnoses. Our study suggests that targeting these patients for routine symptom assessment and management, including for palliative care, would be a reasonable approach given the high symptom burden and relatively high mortality at 1 year.

Interpretation of these findings should be mitigated by the following limitations. Because of our setting, our findings may not be generalizable to all patients with cancer, HF, and COPD. However, our subjects were admitted to general medical and cardiology services, and had common conditions, and therefore are likely similar to those presenting to other hospitals. We relied on self‐report measures to assess severity of symptoms. Patient self‐report, while potentially subject to imprecision due to poor recall and social demand biases, is considered the gold standard for symptom assessment.15 Finally, 2‐week follow‐up is relatively short, and it is possible that symptoms may have improved had we assessed them over a longer period. The longitudinal study of elders in the community that followed subjects over 22 months found that, for many patients, symptoms worsened over time and nearly half of our subjects died at 12 months, suggesting that longer follow‐up would have been unlikely to show improvement in symptoms.6

A significant minority of participants reported a substantial, persistent symptom burden, yet all symptoms assessed in our study are potentially modifiable. Recognizing and treating symptoms can be achieved through the use of targeted interventions.6 Because symptoms can occur in clusters, successful treatment of 1 symptom may also help to improve other symptoms.1 The large number of participants reporting moderate‐to‐severe levels of symptom burden at 2 weeks after discharge highlights an unmet need for improved symptom control in the outpatient setting. Unfortunately, while evidence exists for managing pain in patients with cancer, such evidence‐based practices are lacking for the management of pain and other symptoms in patients with HF and COPD. Some symptoms may require specific, disease‐oriented management. However, many symptoms may be due to common comorbidities, such as pain from degenerative joint disease, that may likely respond to proven treatments.16

Our study confirmed the significant burden of symptoms experienced by patients with serious illness and demonstrated that patients with COPD report as much symptom burden as patients with cancer and HF, if not more. While symptom severity improved over the course of the hospitalization and follow‐up, a large percentage of patients reported significant symptom burden at follow‐up. Depression was also common in these patients. Because these symptoms diminish quality of life, routine assessment and management of these symptoms is critical for improving the quality of care provided to these patients. Additional research on the best approaches to manage symptoms, including medications, interventions, and structures of care, could further improve care.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the patients who participated in this study. They thank Joanne Batt, Wren Levenberg, and Emily Philipps for their expert help as research assistants. They also thank Harold Collard, MD, for providing valuable feedback on the manuscript. Data obtained from the National Death Index assisted us in meeting our study objectives. Steven Pantilat had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

- ,,.Symptom clusters: the new frontier in symptom management research.J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr.2004(32):17–21.

- .Symptom burden: multiple symptoms and their impact as patient‐reported outcomes.J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr.2007(37):16–21.

- ,,.A comparison of symptom prevalence in far advanced cancer, AIDS, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and renal disease.J Pain Symptom Manage.2006;31(1):58–69.

- ,,, et al.Comparing three life‐limiting diseases: does diagnosis matter or is sick, sick?J Pain Symptom Manage.2011;42(3):331–341.

- ,,,,,.Deaths: final data for 2006.Natl Vital Stat Rep.2009;57(14):1–134.

- ,,,,,.Range and severity of symptoms over time among older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure.Arch Intern Med.2007;167(22):2503–2508.

- ,,,.Living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a survey of patients' knowledge and attitudes.Respir Med.2009;103(7):1004–1012.

- ,,,,.The symptom burden of seriously ill hospitalized patients. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcome and Risks of Treatment.J Pain Symptom Manage.1999;17(4):248–255.

- ,,, et al.Relationship between early physician follow‐up and 30‐day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure.JAMA.2010;303(17):1716–1722.

- ,,,.Hospital‐based palliative medicine consultation: a randomized controlled trial.Arch Intern Med.2010;170(22):2038–2040.

- ,,,,.Studies of illness in the aged. The Index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function.JAMA.1963;185:914–919.

- ,,,.Screening for late life depression: cut‐off scores for the Geriatric Depression Scale and the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia among Japanese subjects.Int J Geriatr Psychiatry.2003;18(6):498–505.

- ,.Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations.J Am Stat Assoc.1958;53(282):457–481.

- ,,.End stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.Pneumonol Alergol Pol.2009;77(2):173–179.

- ,,,.Relationship between social desirability and self‐report in chronic pain patients.Clin J Pain.1995;11(3):189–193.

- ,,,.Etiology and severity of pain among outpatients living with HF.J Card Fail.2010;16(8):S88.

- ,,.Symptom clusters: the new frontier in symptom management research.J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr.2004(32):17–21.

- .Symptom burden: multiple symptoms and their impact as patient‐reported outcomes.J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr.2007(37):16–21.

- ,,.A comparison of symptom prevalence in far advanced cancer, AIDS, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and renal disease.J Pain Symptom Manage.2006;31(1):58–69.

- ,,, et al.Comparing three life‐limiting diseases: does diagnosis matter or is sick, sick?J Pain Symptom Manage.2011;42(3):331–341.

- ,,,,,.Deaths: final data for 2006.Natl Vital Stat Rep.2009;57(14):1–134.

- ,,,,,.Range and severity of symptoms over time among older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure.Arch Intern Med.2007;167(22):2503–2508.

- ,,,.Living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a survey of patients' knowledge and attitudes.Respir Med.2009;103(7):1004–1012.

- ,,,,.The symptom burden of seriously ill hospitalized patients. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcome and Risks of Treatment.J Pain Symptom Manage.1999;17(4):248–255.

- ,,, et al.Relationship between early physician follow‐up and 30‐day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure.JAMA.2010;303(17):1716–1722.

- ,,,.Hospital‐based palliative medicine consultation: a randomized controlled trial.Arch Intern Med.2010;170(22):2038–2040.

- ,,,,.Studies of illness in the aged. The Index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function.JAMA.1963;185:914–919.

- ,,,.Screening for late life depression: cut‐off scores for the Geriatric Depression Scale and the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia among Japanese subjects.Int J Geriatr Psychiatry.2003;18(6):498–505.

- ,.Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations.J Am Stat Assoc.1958;53(282):457–481.

- ,,.End stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.Pneumonol Alergol Pol.2009;77(2):173–179.

- ,,,.Relationship between social desirability and self‐report in chronic pain patients.Clin J Pain.1995;11(3):189–193.

- ,,,.Etiology and severity of pain among outpatients living with HF.J Card Fail.2010;16(8):S88.

Copyright © 2012 Society of Hospital Medicine

Editorial

Older Americans comprise approximately half the patients on inpatient medical wards. There are too few geriatricians to care for these patients, and few geriatricians practice hospital medicine. Hospitalists often provide the majority of inpatient geriatric care, and at teaching hospitals, hospitalists also play a pivotal role in educating residents and students to provide high‐quality care for hospitalized geriatric patients. Thus, hospitalists will be the primary clinicians educating many trainees to care for older patients, and the hospitalists must be skilled in addressing the clinical syndromes that are common in these patients, including delirium, dementia, falls, and infection.1 Generalists and geriatricians have anticipated a shortfall in clinicians prepared to educate trainees about geriatrics and called for faculty development for generalists in geriatrics.2, 3

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Podrazik and colleagues present initial results from a major initiative to enhance the quality and quantity of geriatric inpatient education for residents and students.4 The Curriculum for the Hospitalized Aging Medical Patient (CHAMP) at the University of Chicago represents a multifaceted faculty development effort funded in part by the Donald W. Reynolds and John A. Hartford Foundations. In 12 half‐day sessions offered weekly, hospitalist and general internist faculty members learned about four thematic areasthe frail older person, hazards of hospitalization, end‐of‐life issues, and transitions of carewhile also receiving training in engaging and effective teaching strategies. At each session, participants drew on their own experiences attending on the wards to generate clinical examples and test new teaching strategies. CHAMP incorporates the attributes of best practices for integrating geriatrics education into internal medicine residency training: it promotes model care for older hospital patients, uses a train‐the‐trainer model, addresses care transitions, and promotes interdisciplinary teamwork.5

CHAMP achieved its initial goals. Faculty participants were satisfied and CHAMP substantially increased participants' confidence in practicing and teaching geriatric care. Faculty participants also gained confidence in their teaching abilities and presumably learned teaching strategies that could be applied to other topics in inpatient medicine. Faculty participants demonstrated modest improvements in their knowledge of geriatric issues and more positive attitudes about geriatrics at the end of the course than at the beginning. It is worth noting that the hospitalist and general internist ward attending physicians who participated in CHAMP were volunteers and may have started the process with greater interest in learning geriatric care than other attendings. Thus, it is unknown whether CHAMP might have greater or lesser effect on other faculty.

The CHAMP train‐the‐trainer model offers the potential to impact future practitioners. Findings of the CHAMP investigators are consistent with the literature on faculty development programs for educators, which shows that faculty development on teaching yields high participant satisfaction, knowledge gains, and improved self‐assessment of the ability to implement changes in teaching practice.6 The use in CHAMP of a diverse menu of teaching strategies and active learning techniques such as case‐based discussions and the Objective Structured Teaching Exercise in a small group of colleagues should promote learning and retention.

Is the CHAMP curriculum worth the cost? The program requires resources to pay for 48 hours for each faculty participant and for instructors with expertise in geriatrics and teaching skills. We estimate that the cost for 12 faculty participants would be roughly $72,000. We believe this investment will likely pay off in terms of enhancing faculty skills, improving faculty job satisfaction, promoting faculty retention in academic or other teaching positions, and improving care provided by trainees. For example, if CHAMP were to lead to the retention and promotion of even 2 faculty for just 1 year, it would save recruitment costs that would exceed the direct program costs, and other benefits of CHAMP would only further add value. However, analysis of the benefits of CHAMP will require more in‐depth evaluation data of its impact. The program leaders currently contact former participants around the time of ward attending to reinforce teaching concepts and encourage implementation of CHAMP materials, through a Commitment to Change contract. The ultimate downstream educational goal would be that these faculty learners retain and apply this newly acquired knowledge and skills in their clinical practice and teaching activities. Ideally, evidence would confirm that these benefits improve patient care. The long‐term evaluation plan for CHAMP incorporates important additional outcome measures including resident and student geriatric knowledge as well as patient satisfaction and clinical outcomes. We commend the authors for aiming to expand their evaluation plan over time and aspiring for sustained changes in teaching practice. The literature on the impact of hospitalists has similarly evolved from early descriptions of hospitalists and the logistics of developing a hospitalist program to sophisticated analyses of the impact of hospitalists on clinical outcomes such as length of stay and mortality.7, 8

The feasibility of disseminating CHAMP is an open question. The University of Chicago model employs a time‐intensive curriculum that engages participants in part by releasing them from clinical duties for a half day per week. Release time was funded through combined support from external funding sources and the Department of Medicine. This model addresses the major barrier to faculty development in geriatrics for general internists: lack of time.2, 9 The investment in intensive, longitudinal faculty development may generate higher returns than periodic short faculty workshop sessions that do not build in the time for role‐playing, practice, and reinforcement of key concepts. This type of intervention may also be more feasible when done in conjunction with one of the approximately 50 Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)supported Geriatrics Education Centers, which can fund teachers and infrastructure for faculty development.

How is this article useful for hospitalist educators? Many hospitalists at academic centers serve important teaching functions, and some will aspire to advance their educational efforts through more scholarly activities such as curriculum design. The CHAMP curriculum represents a successful model for hospitalists aiming to follow a rigorous approach to curriculum design relevant to inpatient medicine, and the extensive CHAMP materials are available online.10 It serves as a practical model that could be applied to other clinical topics related to hospital medicine. Hospitalists are effective and respected teachers for residents and students, and they develop unique expertise in the content and process of inpatient medicine.11 The authors followed the 6 steps of effective curriculum design: problem identification, targeted needs assessment, goals and objectives, education methods, implementation, and evaluation.12

The CHAMP curriculum typifies a set of materials that aligns well with the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Core Competencies.13 As part of their needs assessment, the authors also surveyed hospitalists at a regional SHM meeting to determine the geriatrics topics for which they perceived greatest educational need. The Core Competencies chapters on the care of the elderly patient, delirium and dementia, hospital‐acquired infections, and palliative care highlight the common learning goals shared by hospital medicine and geriatrics. Both disciplines also emphasize the team‐based, multidisciplinary approach to care, particularly during care transitions, that is highlighted in the CHAMP curriculum.

More generally, the CHAMP curriculum can be used to teach and assess the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) competencies, which must be assessed in all ACGME‐accredited residency programs.14 In an initial session on Teaching on Today's Wards, CHAMP participants brainstorm about how to incorporate both geriatrics content and the ACGME competencies into their post‐call rounds. The emphasis in CHAMP on the health care system and interdisciplinary care is evident in topics such as end‐of‐life care and transitions in care, and provides opportunity for assessment of residents' performance in the ACGME competency of systems‐based practice. The organization of the curriculum by ACGME competency makes it more applicable today than some prior geriatric curricula that emphasized similar themes but without the emphasis on demonstrating competency as an outcome.15

Hospitalists partnering with the Donald W. Reynolds and John A. Hartford Foundations and other external organizations may find funding opportunities for educational projects. For example, the Hartford Foundation has partnered with SHM since 2002 to support hospitalists' efforts to improve care for older adults. Products of this collaboration include a Geriatric Toolbox that contains assessment tools designed for use with geriatric patients.16 The tools assess a range of parameters including nutritional, functional, and mental status, and the website supplies guidelines on the advantages and disadvantages and appropriate use of each assessment tool. With support from the Hartford Foundation, hospitalists have also conducted several workshops at SHM meetings on improving assessment and care of geriatric patients and developed a discharge‐planning checklist for older adults.

As hospitalist programs gain traction in academic centers, hospitalists will increasingly serve as key geriatric content educators for trainees. The CHAMP curriculum offers a model of intensive faculty development for hospitalists and general internists that clinician educators find engaging and empowering. The partnerships of geriatricians and hospitalists, and of the SHM with national geriatrics organizations, have the potential for widespread benefits for both learners and elderly patients.

Older Americans comprise approximately half the patients on inpatient medical wards. There are too few geriatricians to care for these patients, and few geriatricians practice hospital medicine. Hospitalists often provide the majority of inpatient geriatric care, and at teaching hospitals, hospitalists also play a pivotal role in educating residents and students to provide high‐quality care for hospitalized geriatric patients. Thus, hospitalists will be the primary clinicians educating many trainees to care for older patients, and the hospitalists must be skilled in addressing the clinical syndromes that are common in these patients, including delirium, dementia, falls, and infection.1 Generalists and geriatricians have anticipated a shortfall in clinicians prepared to educate trainees about geriatrics and called for faculty development for generalists in geriatrics.2, 3

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Podrazik and colleagues present initial results from a major initiative to enhance the quality and quantity of geriatric inpatient education for residents and students.4 The Curriculum for the Hospitalized Aging Medical Patient (CHAMP) at the University of Chicago represents a multifaceted faculty development effort funded in part by the Donald W. Reynolds and John A. Hartford Foundations. In 12 half‐day sessions offered weekly, hospitalist and general internist faculty members learned about four thematic areasthe frail older person, hazards of hospitalization, end‐of‐life issues, and transitions of carewhile also receiving training in engaging and effective teaching strategies. At each session, participants drew on their own experiences attending on the wards to generate clinical examples and test new teaching strategies. CHAMP incorporates the attributes of best practices for integrating geriatrics education into internal medicine residency training: it promotes model care for older hospital patients, uses a train‐the‐trainer model, addresses care transitions, and promotes interdisciplinary teamwork.5

CHAMP achieved its initial goals. Faculty participants were satisfied and CHAMP substantially increased participants' confidence in practicing and teaching geriatric care. Faculty participants also gained confidence in their teaching abilities and presumably learned teaching strategies that could be applied to other topics in inpatient medicine. Faculty participants demonstrated modest improvements in their knowledge of geriatric issues and more positive attitudes about geriatrics at the end of the course than at the beginning. It is worth noting that the hospitalist and general internist ward attending physicians who participated in CHAMP were volunteers and may have started the process with greater interest in learning geriatric care than other attendings. Thus, it is unknown whether CHAMP might have greater or lesser effect on other faculty.

The CHAMP train‐the‐trainer model offers the potential to impact future practitioners. Findings of the CHAMP investigators are consistent with the literature on faculty development programs for educators, which shows that faculty development on teaching yields high participant satisfaction, knowledge gains, and improved self‐assessment of the ability to implement changes in teaching practice.6 The use in CHAMP of a diverse menu of teaching strategies and active learning techniques such as case‐based discussions and the Objective Structured Teaching Exercise in a small group of colleagues should promote learning and retention.

Is the CHAMP curriculum worth the cost? The program requires resources to pay for 48 hours for each faculty participant and for instructors with expertise in geriatrics and teaching skills. We estimate that the cost for 12 faculty participants would be roughly $72,000. We believe this investment will likely pay off in terms of enhancing faculty skills, improving faculty job satisfaction, promoting faculty retention in academic or other teaching positions, and improving care provided by trainees. For example, if CHAMP were to lead to the retention and promotion of even 2 faculty for just 1 year, it would save recruitment costs that would exceed the direct program costs, and other benefits of CHAMP would only further add value. However, analysis of the benefits of CHAMP will require more in‐depth evaluation data of its impact. The program leaders currently contact former participants around the time of ward attending to reinforce teaching concepts and encourage implementation of CHAMP materials, through a Commitment to Change contract. The ultimate downstream educational goal would be that these faculty learners retain and apply this newly acquired knowledge and skills in their clinical practice and teaching activities. Ideally, evidence would confirm that these benefits improve patient care. The long‐term evaluation plan for CHAMP incorporates important additional outcome measures including resident and student geriatric knowledge as well as patient satisfaction and clinical outcomes. We commend the authors for aiming to expand their evaluation plan over time and aspiring for sustained changes in teaching practice. The literature on the impact of hospitalists has similarly evolved from early descriptions of hospitalists and the logistics of developing a hospitalist program to sophisticated analyses of the impact of hospitalists on clinical outcomes such as length of stay and mortality.7, 8

The feasibility of disseminating CHAMP is an open question. The University of Chicago model employs a time‐intensive curriculum that engages participants in part by releasing them from clinical duties for a half day per week. Release time was funded through combined support from external funding sources and the Department of Medicine. This model addresses the major barrier to faculty development in geriatrics for general internists: lack of time.2, 9 The investment in intensive, longitudinal faculty development may generate higher returns than periodic short faculty workshop sessions that do not build in the time for role‐playing, practice, and reinforcement of key concepts. This type of intervention may also be more feasible when done in conjunction with one of the approximately 50 Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)supported Geriatrics Education Centers, which can fund teachers and infrastructure for faculty development.

How is this article useful for hospitalist educators? Many hospitalists at academic centers serve important teaching functions, and some will aspire to advance their educational efforts through more scholarly activities such as curriculum design. The CHAMP curriculum represents a successful model for hospitalists aiming to follow a rigorous approach to curriculum design relevant to inpatient medicine, and the extensive CHAMP materials are available online.10 It serves as a practical model that could be applied to other clinical topics related to hospital medicine. Hospitalists are effective and respected teachers for residents and students, and they develop unique expertise in the content and process of inpatient medicine.11 The authors followed the 6 steps of effective curriculum design: problem identification, targeted needs assessment, goals and objectives, education methods, implementation, and evaluation.12