User login

Quality Improvement in Health Care: From Conceptual Frameworks and Definitions to Implementation

As the movement to improve quality in health care has evolved over the past several decades, organizations whose missions focus on supporting and promoting quality in health care have defined essential concepts, standards, and measures that comprise quality and that can be used to guide quality improvement (QI) work. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines quality in clinical care as safe, effective, and people-centered service.1 These 3 pillars of quality form the foundation of a quality system aiming to deliver health care in a timely, equitable, efficient, and integrated manner. The WHO estimates that 5.7 to 8.4 million deaths occur yearly in low- and middle-income countries due to poor quality care. Regarding safety, patient harm from unsafe care is estimated to be among the top 10 causes of death and disability worldwide.2 A health care QI plan involves identifying areas for improvement, setting measurable goals, implementing evidence-based strategies and interventions, monitoring progress toward achieving those goals, and continuously evaluating and adjusting the plan as needed to ensure sustained improvement over time. Such a plan can be implemented at various levels of health care organizations, from individual clinical units to entire hospitals or even regional health care systems.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) identifies 5 domains of quality in health care: effectiveness, efficiency, equity, patient-centeredness, and safety.3 Effectiveness relies on providing care processes supported by scientific evidence and achieving desired outcomes in the IOM recommendations. The primary efficiency aim maximizes the quality of health care delivered or the benefits achieved for a given resource unit. Equity relates to providing health care of equal quality to all individuals, regardless of personal characteristics. Moreover, patient-centeredness relates to meeting patients’ needs and preferences and providing education and support. Safety relates to avoiding actual or potential harm. Timeliness relates to obtaining needed care while minimizing delays. Finally, the IOM defines health care quality as the systematic evaluation and provision of evidence-based and safe care characterized by a culture of continuous improvement, resulting in optimal health outcomes. Taking all these concepts into consideration, 4 key attributes have been identified as essential to the global definition of health care quality: effectiveness, safety, culture of continuous improvement, and desired outcomes. This conceptualization of health care quality encompasses the fundamental components and has the potential to enhance the delivery of care. This definition’s theoretical and practical implications provide a comprehensive and consistent understanding of the elements required to improve health care and maintain public trust.

Health care quality is a dynamic, ever-evolving construct that requires continuous assessment and evaluation to ensure the delivery of care meets the changing needs of society. The National Quality Forum’s National Voluntary Consensus Standards for health care provide measures, guidance, and recommendations on achieving effective outcomes through evidence-based practices.4 These standards establish criteria by which health care systems and providers can assess and improve their quality performance.

In the United States, in order to implement and disseminate best practices, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) developed Quality Payment Programs that offer incentives to health care providers to improve the quality of care delivery. This CMS program evaluates providers based on their performance in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System performance categories.5 These include measures related to patient experience, cost, clinical quality, improvement activities, and the use of certified electronic health record technology. The scores that providers receive are used to determine their performance-based reimbursements under Medicare’s fee-for-service program.

The concept of health care quality is also applicable in other countries. In the United Kingdom, QI initiatives are led by the Department of Health and Social Care. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) produces guidelines on best practices to ensure that care delivery meets established safety and quality standards, reaching cost-effectiveness excellence.6 In Australia, the Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Health Care is responsible for setting benchmarks for performance in health care systems through a clear, structured agenda.7 Ultimately, health care quality is a complex and multifaceted issue that requires a comprehensive approach to ensure the best outcomes for patients. With the implementation of measures such as the CMS Quality Payment Programs and NICE guidelines, health care organizations can take steps to ensure their systems of care delivery reflect evidence-based practices and demonstrate a commitment to providing high-quality care.

Implementing a health care QI plan that encompasses the 4 key attributes of health care quality—effectiveness, safety, culture of continuous improvement, and desired outcomes—requires collaboration among different departments and stakeholders and a data-driven approach to decision-making. Effective communication with patients and their families is critical to ensuring that their needs are being met and that they are active partners in their health care journey. While a health care QI plan is essential for delivering high-quality, safe patient care, it also helps health care organizations comply with regulatory requirements, meet accreditation standards, and stay competitive in the ever-evolving health care landscape.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH; Ebrahim.Barkoudah@baystatehealth.org

1. World Health Organization. Quality of care. Accessed on May 17, 2023. www.who.int/health-topics/quality-of-care#tab=tab_1

2. World Health Organization. Patient safety. Accessed on May 17, 2023 www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/patient-safety

3. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Understanding quality measurement. Accessed on May 17, 2023. www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/chtoolbx/understand/index.html

4. Ferrell B, Connor SR, Cordes A, et al. The national agenda for quality palliative care: the National Consensus Project and the National Quality Forum. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(6):737-744. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.024

5. U.S Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Quality payment program. Accessed on March 14, 2023 qpp.cms.gov/mips/overview

6. Claxton K, Martin S, Soares M, et al. Methods for the estimation of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence cost-effectiveness threshold. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(14):1-503, v-vi. doi: 10.3310/hta19140

7. Braithwaite J, Healy J, Dwan K. The Governance of Health Safety and Quality, Commonwealth of Australia. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://regnet.anu.edu.au/research/publications/3626/governance-health-safety-and-quality 2005

As the movement to improve quality in health care has evolved over the past several decades, organizations whose missions focus on supporting and promoting quality in health care have defined essential concepts, standards, and measures that comprise quality and that can be used to guide quality improvement (QI) work. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines quality in clinical care as safe, effective, and people-centered service.1 These 3 pillars of quality form the foundation of a quality system aiming to deliver health care in a timely, equitable, efficient, and integrated manner. The WHO estimates that 5.7 to 8.4 million deaths occur yearly in low- and middle-income countries due to poor quality care. Regarding safety, patient harm from unsafe care is estimated to be among the top 10 causes of death and disability worldwide.2 A health care QI plan involves identifying areas for improvement, setting measurable goals, implementing evidence-based strategies and interventions, monitoring progress toward achieving those goals, and continuously evaluating and adjusting the plan as needed to ensure sustained improvement over time. Such a plan can be implemented at various levels of health care organizations, from individual clinical units to entire hospitals or even regional health care systems.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) identifies 5 domains of quality in health care: effectiveness, efficiency, equity, patient-centeredness, and safety.3 Effectiveness relies on providing care processes supported by scientific evidence and achieving desired outcomes in the IOM recommendations. The primary efficiency aim maximizes the quality of health care delivered or the benefits achieved for a given resource unit. Equity relates to providing health care of equal quality to all individuals, regardless of personal characteristics. Moreover, patient-centeredness relates to meeting patients’ needs and preferences and providing education and support. Safety relates to avoiding actual or potential harm. Timeliness relates to obtaining needed care while minimizing delays. Finally, the IOM defines health care quality as the systematic evaluation and provision of evidence-based and safe care characterized by a culture of continuous improvement, resulting in optimal health outcomes. Taking all these concepts into consideration, 4 key attributes have been identified as essential to the global definition of health care quality: effectiveness, safety, culture of continuous improvement, and desired outcomes. This conceptualization of health care quality encompasses the fundamental components and has the potential to enhance the delivery of care. This definition’s theoretical and practical implications provide a comprehensive and consistent understanding of the elements required to improve health care and maintain public trust.

Health care quality is a dynamic, ever-evolving construct that requires continuous assessment and evaluation to ensure the delivery of care meets the changing needs of society. The National Quality Forum’s National Voluntary Consensus Standards for health care provide measures, guidance, and recommendations on achieving effective outcomes through evidence-based practices.4 These standards establish criteria by which health care systems and providers can assess and improve their quality performance.

In the United States, in order to implement and disseminate best practices, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) developed Quality Payment Programs that offer incentives to health care providers to improve the quality of care delivery. This CMS program evaluates providers based on their performance in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System performance categories.5 These include measures related to patient experience, cost, clinical quality, improvement activities, and the use of certified electronic health record technology. The scores that providers receive are used to determine their performance-based reimbursements under Medicare’s fee-for-service program.

The concept of health care quality is also applicable in other countries. In the United Kingdom, QI initiatives are led by the Department of Health and Social Care. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) produces guidelines on best practices to ensure that care delivery meets established safety and quality standards, reaching cost-effectiveness excellence.6 In Australia, the Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Health Care is responsible for setting benchmarks for performance in health care systems through a clear, structured agenda.7 Ultimately, health care quality is a complex and multifaceted issue that requires a comprehensive approach to ensure the best outcomes for patients. With the implementation of measures such as the CMS Quality Payment Programs and NICE guidelines, health care organizations can take steps to ensure their systems of care delivery reflect evidence-based practices and demonstrate a commitment to providing high-quality care.

Implementing a health care QI plan that encompasses the 4 key attributes of health care quality—effectiveness, safety, culture of continuous improvement, and desired outcomes—requires collaboration among different departments and stakeholders and a data-driven approach to decision-making. Effective communication with patients and their families is critical to ensuring that their needs are being met and that they are active partners in their health care journey. While a health care QI plan is essential for delivering high-quality, safe patient care, it also helps health care organizations comply with regulatory requirements, meet accreditation standards, and stay competitive in the ever-evolving health care landscape.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH; Ebrahim.Barkoudah@baystatehealth.org

As the movement to improve quality in health care has evolved over the past several decades, organizations whose missions focus on supporting and promoting quality in health care have defined essential concepts, standards, and measures that comprise quality and that can be used to guide quality improvement (QI) work. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines quality in clinical care as safe, effective, and people-centered service.1 These 3 pillars of quality form the foundation of a quality system aiming to deliver health care in a timely, equitable, efficient, and integrated manner. The WHO estimates that 5.7 to 8.4 million deaths occur yearly in low- and middle-income countries due to poor quality care. Regarding safety, patient harm from unsafe care is estimated to be among the top 10 causes of death and disability worldwide.2 A health care QI plan involves identifying areas for improvement, setting measurable goals, implementing evidence-based strategies and interventions, monitoring progress toward achieving those goals, and continuously evaluating and adjusting the plan as needed to ensure sustained improvement over time. Such a plan can be implemented at various levels of health care organizations, from individual clinical units to entire hospitals or even regional health care systems.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) identifies 5 domains of quality in health care: effectiveness, efficiency, equity, patient-centeredness, and safety.3 Effectiveness relies on providing care processes supported by scientific evidence and achieving desired outcomes in the IOM recommendations. The primary efficiency aim maximizes the quality of health care delivered or the benefits achieved for a given resource unit. Equity relates to providing health care of equal quality to all individuals, regardless of personal characteristics. Moreover, patient-centeredness relates to meeting patients’ needs and preferences and providing education and support. Safety relates to avoiding actual or potential harm. Timeliness relates to obtaining needed care while minimizing delays. Finally, the IOM defines health care quality as the systematic evaluation and provision of evidence-based and safe care characterized by a culture of continuous improvement, resulting in optimal health outcomes. Taking all these concepts into consideration, 4 key attributes have been identified as essential to the global definition of health care quality: effectiveness, safety, culture of continuous improvement, and desired outcomes. This conceptualization of health care quality encompasses the fundamental components and has the potential to enhance the delivery of care. This definition’s theoretical and practical implications provide a comprehensive and consistent understanding of the elements required to improve health care and maintain public trust.

Health care quality is a dynamic, ever-evolving construct that requires continuous assessment and evaluation to ensure the delivery of care meets the changing needs of society. The National Quality Forum’s National Voluntary Consensus Standards for health care provide measures, guidance, and recommendations on achieving effective outcomes through evidence-based practices.4 These standards establish criteria by which health care systems and providers can assess and improve their quality performance.

In the United States, in order to implement and disseminate best practices, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) developed Quality Payment Programs that offer incentives to health care providers to improve the quality of care delivery. This CMS program evaluates providers based on their performance in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System performance categories.5 These include measures related to patient experience, cost, clinical quality, improvement activities, and the use of certified electronic health record technology. The scores that providers receive are used to determine their performance-based reimbursements under Medicare’s fee-for-service program.

The concept of health care quality is also applicable in other countries. In the United Kingdom, QI initiatives are led by the Department of Health and Social Care. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) produces guidelines on best practices to ensure that care delivery meets established safety and quality standards, reaching cost-effectiveness excellence.6 In Australia, the Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Health Care is responsible for setting benchmarks for performance in health care systems through a clear, structured agenda.7 Ultimately, health care quality is a complex and multifaceted issue that requires a comprehensive approach to ensure the best outcomes for patients. With the implementation of measures such as the CMS Quality Payment Programs and NICE guidelines, health care organizations can take steps to ensure their systems of care delivery reflect evidence-based practices and demonstrate a commitment to providing high-quality care.

Implementing a health care QI plan that encompasses the 4 key attributes of health care quality—effectiveness, safety, culture of continuous improvement, and desired outcomes—requires collaboration among different departments and stakeholders and a data-driven approach to decision-making. Effective communication with patients and their families is critical to ensuring that their needs are being met and that they are active partners in their health care journey. While a health care QI plan is essential for delivering high-quality, safe patient care, it also helps health care organizations comply with regulatory requirements, meet accreditation standards, and stay competitive in the ever-evolving health care landscape.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH; Ebrahim.Barkoudah@baystatehealth.org

1. World Health Organization. Quality of care. Accessed on May 17, 2023. www.who.int/health-topics/quality-of-care#tab=tab_1

2. World Health Organization. Patient safety. Accessed on May 17, 2023 www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/patient-safety

3. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Understanding quality measurement. Accessed on May 17, 2023. www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/chtoolbx/understand/index.html

4. Ferrell B, Connor SR, Cordes A, et al. The national agenda for quality palliative care: the National Consensus Project and the National Quality Forum. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(6):737-744. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.024

5. U.S Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Quality payment program. Accessed on March 14, 2023 qpp.cms.gov/mips/overview

6. Claxton K, Martin S, Soares M, et al. Methods for the estimation of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence cost-effectiveness threshold. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(14):1-503, v-vi. doi: 10.3310/hta19140

7. Braithwaite J, Healy J, Dwan K. The Governance of Health Safety and Quality, Commonwealth of Australia. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://regnet.anu.edu.au/research/publications/3626/governance-health-safety-and-quality 2005

1. World Health Organization. Quality of care. Accessed on May 17, 2023. www.who.int/health-topics/quality-of-care#tab=tab_1

2. World Health Organization. Patient safety. Accessed on May 17, 2023 www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/patient-safety

3. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Understanding quality measurement. Accessed on May 17, 2023. www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/chtoolbx/understand/index.html

4. Ferrell B, Connor SR, Cordes A, et al. The national agenda for quality palliative care: the National Consensus Project and the National Quality Forum. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(6):737-744. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.024

5. U.S Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Quality payment program. Accessed on March 14, 2023 qpp.cms.gov/mips/overview

6. Claxton K, Martin S, Soares M, et al. Methods for the estimation of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence cost-effectiveness threshold. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(14):1-503, v-vi. doi: 10.3310/hta19140

7. Braithwaite J, Healy J, Dwan K. The Governance of Health Safety and Quality, Commonwealth of Australia. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://regnet.anu.edu.au/research/publications/3626/governance-health-safety-and-quality 2005

The Mission of Continuous Improvement in Health Care: A New Era for Clinical Outcomes Management

This issue of the Journal of Clinical Outcomes (JCOM) debuts a new cover design that brings forward the articles and features in each issue. Although the Journal’s cover has a new look, JCOM’s goals remain the same—improving care by disseminating evidence of quality improvement in health care and sharing access to the medical literature with our readers. We continue our mission to promote the best medical practice by providing clinicians with updates and communicating advances that lead to measurable improvement in health care delivery, quality, and outcomes.

As we continue the work of improving health care quality, knowledge gaps and unmet needs in the literature remain. These unmet needs are evident throughout all phases of health care delivery. Moreover, the Institutes of Medicine report that centered on efforts to build a safer health care environment by redesigning health care processes remains salient.1 The journey to continuous improvement in health care, where we achieve threshold change in the quality of each process and across the entire health care system, requires collective effort. Such efforts include establishing clear metrics and measurements for improvement goals throughout the patient’s journey through diagnosis, treatment, transitions of care, and disease management.2,3 To address evidence and knowledge gaps in the literature, JCOM publishes reports of original studies and quality improvement projects as well as reviews, providing its 30,000 readers with new evidence to implement in daily practice. We welcome submissions of original research reports, reports of quality improvement projects that follow the SQUIRE 2.0 standards,4 and perspectives on developments and innovations in health care delivery.

The next chapter in health care delivery improvement will encompass value-based care.5 This new era of clinical outcomes management will dictate the metrics and outcomes reporting6 and how to plan future investments. The value-based phase will increase innovation and shape policies that advance population health, transforming every step in the care delivery journey.7 The next phase in health care delivery will also create a viable financial structure while implementing effective performance measures for optimal outcomes through patient-centered care and optimization of cost and care strategies. In light of health care’s evolution toward a value-based model, JCOM welcomes submissions of manuscripts that explore themes central to this model, including patient-centered care, implementation of best practices, system design, safety, cost-effectiveness, and the balance between cost optimization and quality. For JCOM’s authors and readers, our editorial team remains commited to the highest standards in timely publishing to support our community through our collective expertise and dedication to quality improvement.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

1. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2000.

2. Singh H, Sittig DF. Advancing the science of measurement of diagnostic errors in healthcare: the Safer Dx framework. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(2):103-10. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003675

3. Bates DW. Preventing medication errors: a summary. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64(14 Suppl 9):S3-9. doi:10.2146/ajhp070190

4. Revised Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence. SQUIRE 2.0. Accessed July 25, 2022. http://squire-statement.org

5. Gray M. Value based healthcare. BMJ. 2017;356:j437. doi:10.1136/bmj.j437

6. What is value-based healthcare? NEJM Catalyst. January 1, 2017. Accessed July 25, 2022. catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.17.0558

7. Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results. Harvard Business Press; 2006.

This issue of the Journal of Clinical Outcomes (JCOM) debuts a new cover design that brings forward the articles and features in each issue. Although the Journal’s cover has a new look, JCOM’s goals remain the same—improving care by disseminating evidence of quality improvement in health care and sharing access to the medical literature with our readers. We continue our mission to promote the best medical practice by providing clinicians with updates and communicating advances that lead to measurable improvement in health care delivery, quality, and outcomes.

As we continue the work of improving health care quality, knowledge gaps and unmet needs in the literature remain. These unmet needs are evident throughout all phases of health care delivery. Moreover, the Institutes of Medicine report that centered on efforts to build a safer health care environment by redesigning health care processes remains salient.1 The journey to continuous improvement in health care, where we achieve threshold change in the quality of each process and across the entire health care system, requires collective effort. Such efforts include establishing clear metrics and measurements for improvement goals throughout the patient’s journey through diagnosis, treatment, transitions of care, and disease management.2,3 To address evidence and knowledge gaps in the literature, JCOM publishes reports of original studies and quality improvement projects as well as reviews, providing its 30,000 readers with new evidence to implement in daily practice. We welcome submissions of original research reports, reports of quality improvement projects that follow the SQUIRE 2.0 standards,4 and perspectives on developments and innovations in health care delivery.

The next chapter in health care delivery improvement will encompass value-based care.5 This new era of clinical outcomes management will dictate the metrics and outcomes reporting6 and how to plan future investments. The value-based phase will increase innovation and shape policies that advance population health, transforming every step in the care delivery journey.7 The next phase in health care delivery will also create a viable financial structure while implementing effective performance measures for optimal outcomes through patient-centered care and optimization of cost and care strategies. In light of health care’s evolution toward a value-based model, JCOM welcomes submissions of manuscripts that explore themes central to this model, including patient-centered care, implementation of best practices, system design, safety, cost-effectiveness, and the balance between cost optimization and quality. For JCOM’s authors and readers, our editorial team remains commited to the highest standards in timely publishing to support our community through our collective expertise and dedication to quality improvement.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

This issue of the Journal of Clinical Outcomes (JCOM) debuts a new cover design that brings forward the articles and features in each issue. Although the Journal’s cover has a new look, JCOM’s goals remain the same—improving care by disseminating evidence of quality improvement in health care and sharing access to the medical literature with our readers. We continue our mission to promote the best medical practice by providing clinicians with updates and communicating advances that lead to measurable improvement in health care delivery, quality, and outcomes.

As we continue the work of improving health care quality, knowledge gaps and unmet needs in the literature remain. These unmet needs are evident throughout all phases of health care delivery. Moreover, the Institutes of Medicine report that centered on efforts to build a safer health care environment by redesigning health care processes remains salient.1 The journey to continuous improvement in health care, where we achieve threshold change in the quality of each process and across the entire health care system, requires collective effort. Such efforts include establishing clear metrics and measurements for improvement goals throughout the patient’s journey through diagnosis, treatment, transitions of care, and disease management.2,3 To address evidence and knowledge gaps in the literature, JCOM publishes reports of original studies and quality improvement projects as well as reviews, providing its 30,000 readers with new evidence to implement in daily practice. We welcome submissions of original research reports, reports of quality improvement projects that follow the SQUIRE 2.0 standards,4 and perspectives on developments and innovations in health care delivery.

The next chapter in health care delivery improvement will encompass value-based care.5 This new era of clinical outcomes management will dictate the metrics and outcomes reporting6 and how to plan future investments. The value-based phase will increase innovation and shape policies that advance population health, transforming every step in the care delivery journey.7 The next phase in health care delivery will also create a viable financial structure while implementing effective performance measures for optimal outcomes through patient-centered care and optimization of cost and care strategies. In light of health care’s evolution toward a value-based model, JCOM welcomes submissions of manuscripts that explore themes central to this model, including patient-centered care, implementation of best practices, system design, safety, cost-effectiveness, and the balance between cost optimization and quality. For JCOM’s authors and readers, our editorial team remains commited to the highest standards in timely publishing to support our community through our collective expertise and dedication to quality improvement.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

1. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2000.

2. Singh H, Sittig DF. Advancing the science of measurement of diagnostic errors in healthcare: the Safer Dx framework. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(2):103-10. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003675

3. Bates DW. Preventing medication errors: a summary. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64(14 Suppl 9):S3-9. doi:10.2146/ajhp070190

4. Revised Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence. SQUIRE 2.0. Accessed July 25, 2022. http://squire-statement.org

5. Gray M. Value based healthcare. BMJ. 2017;356:j437. doi:10.1136/bmj.j437

6. What is value-based healthcare? NEJM Catalyst. January 1, 2017. Accessed July 25, 2022. catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.17.0558

7. Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results. Harvard Business Press; 2006.

1. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2000.

2. Singh H, Sittig DF. Advancing the science of measurement of diagnostic errors in healthcare: the Safer Dx framework. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(2):103-10. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003675

3. Bates DW. Preventing medication errors: a summary. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64(14 Suppl 9):S3-9. doi:10.2146/ajhp070190

4. Revised Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence. SQUIRE 2.0. Accessed July 25, 2022. http://squire-statement.org

5. Gray M. Value based healthcare. BMJ. 2017;356:j437. doi:10.1136/bmj.j437

6. What is value-based healthcare? NEJM Catalyst. January 1, 2017. Accessed July 25, 2022. catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.17.0558

7. Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results. Harvard Business Press; 2006.

The Intersection of Clinical Quality Improvement Research and Implementation Science

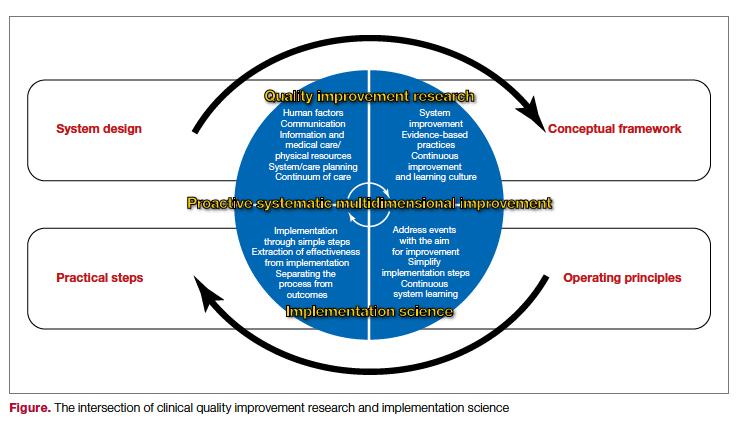

The Institute of Medicine brought much-needed attention to the need for process improvement in medicine with its seminal report To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, which was issued in 1999, leading to the quality movement’s call to close health care performance gaps in Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century.1,2 Quality improvement science in medicine has evolved over the past 2 decades to include a broad spectrum of approaches, from agile improvement to continuous learning and improvement. Current efforts focus on Lean-based process improvement along with a reduction in variation in clinical practice to align practice with the principles of evidence-based medicine in a patient-centered approach.3 Further, the definition of quality improvement under the Affordable Care Act was framed as an equitable, timely, value-based, patient-centered approach to achieving population-level health goals.4 Thus, the science of quality improvement drives the core principles of care delivery improvement, and the rigorous evidence needed to expand innovation is embedded within the same framework.5,6 In clinical practice, quality improvement projects aim to define gaps and then specific steps are undertaken to improve the evidence-based practice of a specific process. The overarching goal is to enhance the efficacy of the practice by reducing waste within a particular domain. Thus, quality improvement and implementation research eventually unify how clinical practice is advanced concurrently to bridge identified gaps.7

System redesign through a patient-centered framework forms the core of an overarching strategy to support system-level processes. Both require a deep understanding of the fields of quality improvement science and implementation science.8 Furthermore, aligning clinical research needs, system aims, patients’ values, and clinical care give the new design a clear path forward. Patient-centered improvement includes the essential elements of system redesign around human factors, including communication, physical resources, and updated information during episodes of care. The patient-centered improvement design is juxtaposed with care planning and establishing continuum of care processes.9 It is essential to note that safety is rooted within the quality domain as a top priority in medicine.10 The best implementation methods and approaches are discussed and debated, and the improvement progress continues on multiple fronts.11 Patient safety systems are implemented simultaneously during the redesign phase. Moreover, identifying and testing the health care delivery methods in the era of competing strategic priorities to achieve the desirable clinical outcomes highlights the importance of implementation, while contemplating the methods of dissemination, scalability, and sustainability of the best evidence-based clinical practice.

The cycle of quality improvement research completes the system implementation efforts. The conceptual framework of quality improvement includes multiple areas of care and transition, along with applying the best clinical practices in a culture that emphasizes continuous improvement and learning. At the same time, the operating principles should include continuous improvement in a simple and continuous system of learning as a core concept. Our proposed implementation approach involves taking simple and practical steps while separating the process from the outcomes measures, extracting effectiveness throughout the process. It is essential to keep in mind that building a proactive and systematic improvement environment requires a framework for safety, reliability, and effective care, as well as the alignment of the physical system, communication, and professional environment and culture (Figure).

In summary, system design for quality improvement research should incorporate the principles and conceptual framework that embody effective implementation strategies, with a focus on operational and practical steps. Continuous improvement will be reached through the multidimensional development of current health care system metrics and the incorporation of implementation science methods.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2000.

2. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001.

3. Berwick DM. The science of improvement. JAMA. 2008;299(10):1182-1184. doi:10.1001/jama.299.10.1182

4. Mazurenko O, Balio CP, Agarwal R, Carroll AE, Menachemi N. The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: a systematic review. Health Affairs. 2018;37(6):944-950. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1491

5. Fan E, Needham DM. The science of quality improvement. JAMA. 2008;300(4):390-391. doi:10.1001/jama.300.4.390-b

6. Alexander JA, Hearld LR. The science of quality improvement implementation: developing capacity to make a difference. Med Care. 2011:S6-20. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e1709c

7. Rohweder C, Wangen M, Black M, et al. Understanding quality improvement collaboratives through an implementation science lens. Prev Med. 2019;129:105859. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105859

8. Bergeson SC, Dean JD. A systems approach to patient-centered care. JAMA. 2006;296(23):2848-2851. doi:10.1001/jama.296.23.2848

9. Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):i85-90. doi:10.1136/qhc.13.suppl_1.i85

10. Leape LL, Berwick DM, Bates DW. What practices will most improve safety? Evidence-based medicine meets patient safety. JAMA. 2002;288(4):501-507. doi:10.1001/jama.288.4.501

11. Auerbach AD, Landefeld CS, Shojania KG. The tension between needing to improve care and knowing how to do it. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(6):608-613. doi:10.1056/NEJMsb070738

The Institute of Medicine brought much-needed attention to the need for process improvement in medicine with its seminal report To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, which was issued in 1999, leading to the quality movement’s call to close health care performance gaps in Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century.1,2 Quality improvement science in medicine has evolved over the past 2 decades to include a broad spectrum of approaches, from agile improvement to continuous learning and improvement. Current efforts focus on Lean-based process improvement along with a reduction in variation in clinical practice to align practice with the principles of evidence-based medicine in a patient-centered approach.3 Further, the definition of quality improvement under the Affordable Care Act was framed as an equitable, timely, value-based, patient-centered approach to achieving population-level health goals.4 Thus, the science of quality improvement drives the core principles of care delivery improvement, and the rigorous evidence needed to expand innovation is embedded within the same framework.5,6 In clinical practice, quality improvement projects aim to define gaps and then specific steps are undertaken to improve the evidence-based practice of a specific process. The overarching goal is to enhance the efficacy of the practice by reducing waste within a particular domain. Thus, quality improvement and implementation research eventually unify how clinical practice is advanced concurrently to bridge identified gaps.7

System redesign through a patient-centered framework forms the core of an overarching strategy to support system-level processes. Both require a deep understanding of the fields of quality improvement science and implementation science.8 Furthermore, aligning clinical research needs, system aims, patients’ values, and clinical care give the new design a clear path forward. Patient-centered improvement includes the essential elements of system redesign around human factors, including communication, physical resources, and updated information during episodes of care. The patient-centered improvement design is juxtaposed with care planning and establishing continuum of care processes.9 It is essential to note that safety is rooted within the quality domain as a top priority in medicine.10 The best implementation methods and approaches are discussed and debated, and the improvement progress continues on multiple fronts.11 Patient safety systems are implemented simultaneously during the redesign phase. Moreover, identifying and testing the health care delivery methods in the era of competing strategic priorities to achieve the desirable clinical outcomes highlights the importance of implementation, while contemplating the methods of dissemination, scalability, and sustainability of the best evidence-based clinical practice.

The cycle of quality improvement research completes the system implementation efforts. The conceptual framework of quality improvement includes multiple areas of care and transition, along with applying the best clinical practices in a culture that emphasizes continuous improvement and learning. At the same time, the operating principles should include continuous improvement in a simple and continuous system of learning as a core concept. Our proposed implementation approach involves taking simple and practical steps while separating the process from the outcomes measures, extracting effectiveness throughout the process. It is essential to keep in mind that building a proactive and systematic improvement environment requires a framework for safety, reliability, and effective care, as well as the alignment of the physical system, communication, and professional environment and culture (Figure).

In summary, system design for quality improvement research should incorporate the principles and conceptual framework that embody effective implementation strategies, with a focus on operational and practical steps. Continuous improvement will be reached through the multidimensional development of current health care system metrics and the incorporation of implementation science methods.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

Disclosures: None reported.

The Institute of Medicine brought much-needed attention to the need for process improvement in medicine with its seminal report To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, which was issued in 1999, leading to the quality movement’s call to close health care performance gaps in Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century.1,2 Quality improvement science in medicine has evolved over the past 2 decades to include a broad spectrum of approaches, from agile improvement to continuous learning and improvement. Current efforts focus on Lean-based process improvement along with a reduction in variation in clinical practice to align practice with the principles of evidence-based medicine in a patient-centered approach.3 Further, the definition of quality improvement under the Affordable Care Act was framed as an equitable, timely, value-based, patient-centered approach to achieving population-level health goals.4 Thus, the science of quality improvement drives the core principles of care delivery improvement, and the rigorous evidence needed to expand innovation is embedded within the same framework.5,6 In clinical practice, quality improvement projects aim to define gaps and then specific steps are undertaken to improve the evidence-based practice of a specific process. The overarching goal is to enhance the efficacy of the practice by reducing waste within a particular domain. Thus, quality improvement and implementation research eventually unify how clinical practice is advanced concurrently to bridge identified gaps.7

System redesign through a patient-centered framework forms the core of an overarching strategy to support system-level processes. Both require a deep understanding of the fields of quality improvement science and implementation science.8 Furthermore, aligning clinical research needs, system aims, patients’ values, and clinical care give the new design a clear path forward. Patient-centered improvement includes the essential elements of system redesign around human factors, including communication, physical resources, and updated information during episodes of care. The patient-centered improvement design is juxtaposed with care planning and establishing continuum of care processes.9 It is essential to note that safety is rooted within the quality domain as a top priority in medicine.10 The best implementation methods and approaches are discussed and debated, and the improvement progress continues on multiple fronts.11 Patient safety systems are implemented simultaneously during the redesign phase. Moreover, identifying and testing the health care delivery methods in the era of competing strategic priorities to achieve the desirable clinical outcomes highlights the importance of implementation, while contemplating the methods of dissemination, scalability, and sustainability of the best evidence-based clinical practice.

The cycle of quality improvement research completes the system implementation efforts. The conceptual framework of quality improvement includes multiple areas of care and transition, along with applying the best clinical practices in a culture that emphasizes continuous improvement and learning. At the same time, the operating principles should include continuous improvement in a simple and continuous system of learning as a core concept. Our proposed implementation approach involves taking simple and practical steps while separating the process from the outcomes measures, extracting effectiveness throughout the process. It is essential to keep in mind that building a proactive and systematic improvement environment requires a framework for safety, reliability, and effective care, as well as the alignment of the physical system, communication, and professional environment and culture (Figure).

In summary, system design for quality improvement research should incorporate the principles and conceptual framework that embody effective implementation strategies, with a focus on operational and practical steps. Continuous improvement will be reached through the multidimensional development of current health care system metrics and the incorporation of implementation science methods.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2000.

2. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001.

3. Berwick DM. The science of improvement. JAMA. 2008;299(10):1182-1184. doi:10.1001/jama.299.10.1182

4. Mazurenko O, Balio CP, Agarwal R, Carroll AE, Menachemi N. The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: a systematic review. Health Affairs. 2018;37(6):944-950. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1491

5. Fan E, Needham DM. The science of quality improvement. JAMA. 2008;300(4):390-391. doi:10.1001/jama.300.4.390-b

6. Alexander JA, Hearld LR. The science of quality improvement implementation: developing capacity to make a difference. Med Care. 2011:S6-20. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e1709c

7. Rohweder C, Wangen M, Black M, et al. Understanding quality improvement collaboratives through an implementation science lens. Prev Med. 2019;129:105859. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105859

8. Bergeson SC, Dean JD. A systems approach to patient-centered care. JAMA. 2006;296(23):2848-2851. doi:10.1001/jama.296.23.2848

9. Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):i85-90. doi:10.1136/qhc.13.suppl_1.i85

10. Leape LL, Berwick DM, Bates DW. What practices will most improve safety? Evidence-based medicine meets patient safety. JAMA. 2002;288(4):501-507. doi:10.1001/jama.288.4.501

11. Auerbach AD, Landefeld CS, Shojania KG. The tension between needing to improve care and knowing how to do it. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(6):608-613. doi:10.1056/NEJMsb070738

1. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2000.

2. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001.

3. Berwick DM. The science of improvement. JAMA. 2008;299(10):1182-1184. doi:10.1001/jama.299.10.1182

4. Mazurenko O, Balio CP, Agarwal R, Carroll AE, Menachemi N. The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: a systematic review. Health Affairs. 2018;37(6):944-950. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1491

5. Fan E, Needham DM. The science of quality improvement. JAMA. 2008;300(4):390-391. doi:10.1001/jama.300.4.390-b

6. Alexander JA, Hearld LR. The science of quality improvement implementation: developing capacity to make a difference. Med Care. 2011:S6-20. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e1709c

7. Rohweder C, Wangen M, Black M, et al. Understanding quality improvement collaboratives through an implementation science lens. Prev Med. 2019;129:105859. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105859

8. Bergeson SC, Dean JD. A systems approach to patient-centered care. JAMA. 2006;296(23):2848-2851. doi:10.1001/jama.296.23.2848

9. Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):i85-90. doi:10.1136/qhc.13.suppl_1.i85

10. Leape LL, Berwick DM, Bates DW. What practices will most improve safety? Evidence-based medicine meets patient safety. JAMA. 2002;288(4):501-507. doi:10.1001/jama.288.4.501

11. Auerbach AD, Landefeld CS, Shojania KG. The tension between needing to improve care and knowing how to do it. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(6):608-613. doi:10.1056/NEJMsb070738

Aiming for System Improvement While Transitioning to the New Normal

As we transition out of the Omicron surge, the lessons we’ve learned from the prior surges carry forward and add to our knowledge foundation. Medical journals have published numerous research and perspectives manuscripts on all aspects of COVID-19 over the past 2 years, adding much-needed knowledge to our clinical practice during the pandemic. However, the story does not stop there, as the pandemic has impacted the usual, non-COVID-19 clinical care we provide. The value-based health care delivery model accounts for both COVID-19 clinical care and the usual care we provide our patients every day. Clinicians, administrators, and health care workers will need to know how to balance both worlds in the years to come.

In this issue of JCOM, the work of balancing the demands of COVID-19 care with those of system improvement continues. Two original research articles address the former, with Liesching et al1 reporting data on improving clinical outcomes of patients with COVID-19 through acute care oxygen therapies, and Ali et al2 explaining the impact of COVID-19 on STEMI care delivery models. Liesching et al’s study showed that patients admitted for COVID-19 after the first surge were more likely to receive high-flow nasal cannula and had better outcomes, while Ali et al showed that patients with STEMI yet again experienced worse outcomes during the first wave.

On the system improvement front, Cusick et al3 report on a quality improvement (QI) project that addressed acute disease management of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) during hospitalization, Sosa et al4 discuss efforts to improve comorbidity capture at their institution, and Uche et al5 present the results of a nonpharmacologic initiative to improve management of chronic pain among veterans. Cusick et al’s QI project showed that a HIT testing strategy could be safely implemented through an evidence-based process to nudge resource utilization using specific management pathways. While capturing and measuring the complexity of diseases and comorbidities can be challenging, accurate capture is essential, as patient acuity has implications for reimbursement and quality comparisons for hospitals and physicians; Sosa et al describe a series of initiatives implemented at their institution that improved comorbidity capture. Furthermore, Uche et al report on a 10-week complementary and integrative health program for veterans with noncancer chronic pain that reduced pain intensity and improved quality of life for its participants. These QI reports show that, though the health care landscape has changed over the past 2 years, the aim remains the same: to provide the best care for patients regardless of the diagnosis, location, or time.

Conducting QI projects during the COVID-19 pandemic has been difficult, especially in terms of implementing consistent processes and management pathways while contending with staff and supply shortages. The pandemic, however, has highlighted the importance of continuing QI efforts, specifically around infectious disease prevention and good clinical practices. Moreover, the recent continuous learning and implementation around COVID-19 patient care has been a significant achievement, as clinicians and administrators worked continuously to understand and improve processes, create a supporting culture, and redesign care delivery on the fly. The management of both COVID-19 care and our usual care QI efforts should incorporate the lessons learned from the pandemic and leverage system redesign for future steps. As we’ve seen, survival in COVID-19 improved dramatically since the beginning of the pandemic, as clinical trials became more adaptive and efficient and system upgrades like telemedicine and digital technologies in the public health response led to major advancements. The work to improve the care provided in the clinic and at the bedside will continue through one collective approach in the new normal.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

1. Liesching TN, Lei Y. Oxygen therapies and clinical outcomes for patients hospitalized with covid-19: first surge vs second surge. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2022;29(2):58-64. doi:10.12788/jcom.0086

2. Ali SH, Hyer S, Davis K, Murrow JR. Acute STEMI during the COVID-19 pandemic at Piedmont Athens Regional: incidence, clinical characteristics, and outcomes. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2022;29(2):65-71. doi:10.12788/jcom.0085

3. Cusick A, Hanigan S, Bashaw L, et al. A practical and cost-effective approach to the diagnosis of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: a single-center quality improvement study. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2022;29(2):72-77.

4. Sosa MA, Ferreira T, Gershengorn H, et al. Improving hospital metrics through the implementation of a comorbidity capture tool and other quality initiatives. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2022;29(2):80-87. doi:10.12788/jcom.00885. Uche JU, Jamison M, Waugh S. Evaluation of the Empower Veterans Program for military veterans with chronic pain. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2022;29(2):88-95. doi:10.12788/jcom.0089

As we transition out of the Omicron surge, the lessons we’ve learned from the prior surges carry forward and add to our knowledge foundation. Medical journals have published numerous research and perspectives manuscripts on all aspects of COVID-19 over the past 2 years, adding much-needed knowledge to our clinical practice during the pandemic. However, the story does not stop there, as the pandemic has impacted the usual, non-COVID-19 clinical care we provide. The value-based health care delivery model accounts for both COVID-19 clinical care and the usual care we provide our patients every day. Clinicians, administrators, and health care workers will need to know how to balance both worlds in the years to come.

In this issue of JCOM, the work of balancing the demands of COVID-19 care with those of system improvement continues. Two original research articles address the former, with Liesching et al1 reporting data on improving clinical outcomes of patients with COVID-19 through acute care oxygen therapies, and Ali et al2 explaining the impact of COVID-19 on STEMI care delivery models. Liesching et al’s study showed that patients admitted for COVID-19 after the first surge were more likely to receive high-flow nasal cannula and had better outcomes, while Ali et al showed that patients with STEMI yet again experienced worse outcomes during the first wave.

On the system improvement front, Cusick et al3 report on a quality improvement (QI) project that addressed acute disease management of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) during hospitalization, Sosa et al4 discuss efforts to improve comorbidity capture at their institution, and Uche et al5 present the results of a nonpharmacologic initiative to improve management of chronic pain among veterans. Cusick et al’s QI project showed that a HIT testing strategy could be safely implemented through an evidence-based process to nudge resource utilization using specific management pathways. While capturing and measuring the complexity of diseases and comorbidities can be challenging, accurate capture is essential, as patient acuity has implications for reimbursement and quality comparisons for hospitals and physicians; Sosa et al describe a series of initiatives implemented at their institution that improved comorbidity capture. Furthermore, Uche et al report on a 10-week complementary and integrative health program for veterans with noncancer chronic pain that reduced pain intensity and improved quality of life for its participants. These QI reports show that, though the health care landscape has changed over the past 2 years, the aim remains the same: to provide the best care for patients regardless of the diagnosis, location, or time.

Conducting QI projects during the COVID-19 pandemic has been difficult, especially in terms of implementing consistent processes and management pathways while contending with staff and supply shortages. The pandemic, however, has highlighted the importance of continuing QI efforts, specifically around infectious disease prevention and good clinical practices. Moreover, the recent continuous learning and implementation around COVID-19 patient care has been a significant achievement, as clinicians and administrators worked continuously to understand and improve processes, create a supporting culture, and redesign care delivery on the fly. The management of both COVID-19 care and our usual care QI efforts should incorporate the lessons learned from the pandemic and leverage system redesign for future steps. As we’ve seen, survival in COVID-19 improved dramatically since the beginning of the pandemic, as clinical trials became more adaptive and efficient and system upgrades like telemedicine and digital technologies in the public health response led to major advancements. The work to improve the care provided in the clinic and at the bedside will continue through one collective approach in the new normal.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

As we transition out of the Omicron surge, the lessons we’ve learned from the prior surges carry forward and add to our knowledge foundation. Medical journals have published numerous research and perspectives manuscripts on all aspects of COVID-19 over the past 2 years, adding much-needed knowledge to our clinical practice during the pandemic. However, the story does not stop there, as the pandemic has impacted the usual, non-COVID-19 clinical care we provide. The value-based health care delivery model accounts for both COVID-19 clinical care and the usual care we provide our patients every day. Clinicians, administrators, and health care workers will need to know how to balance both worlds in the years to come.

In this issue of JCOM, the work of balancing the demands of COVID-19 care with those of system improvement continues. Two original research articles address the former, with Liesching et al1 reporting data on improving clinical outcomes of patients with COVID-19 through acute care oxygen therapies, and Ali et al2 explaining the impact of COVID-19 on STEMI care delivery models. Liesching et al’s study showed that patients admitted for COVID-19 after the first surge were more likely to receive high-flow nasal cannula and had better outcomes, while Ali et al showed that patients with STEMI yet again experienced worse outcomes during the first wave.

On the system improvement front, Cusick et al3 report on a quality improvement (QI) project that addressed acute disease management of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) during hospitalization, Sosa et al4 discuss efforts to improve comorbidity capture at their institution, and Uche et al5 present the results of a nonpharmacologic initiative to improve management of chronic pain among veterans. Cusick et al’s QI project showed that a HIT testing strategy could be safely implemented through an evidence-based process to nudge resource utilization using specific management pathways. While capturing and measuring the complexity of diseases and comorbidities can be challenging, accurate capture is essential, as patient acuity has implications for reimbursement and quality comparisons for hospitals and physicians; Sosa et al describe a series of initiatives implemented at their institution that improved comorbidity capture. Furthermore, Uche et al report on a 10-week complementary and integrative health program for veterans with noncancer chronic pain that reduced pain intensity and improved quality of life for its participants. These QI reports show that, though the health care landscape has changed over the past 2 years, the aim remains the same: to provide the best care for patients regardless of the diagnosis, location, or time.

Conducting QI projects during the COVID-19 pandemic has been difficult, especially in terms of implementing consistent processes and management pathways while contending with staff and supply shortages. The pandemic, however, has highlighted the importance of continuing QI efforts, specifically around infectious disease prevention and good clinical practices. Moreover, the recent continuous learning and implementation around COVID-19 patient care has been a significant achievement, as clinicians and administrators worked continuously to understand and improve processes, create a supporting culture, and redesign care delivery on the fly. The management of both COVID-19 care and our usual care QI efforts should incorporate the lessons learned from the pandemic and leverage system redesign for future steps. As we’ve seen, survival in COVID-19 improved dramatically since the beginning of the pandemic, as clinical trials became more adaptive and efficient and system upgrades like telemedicine and digital technologies in the public health response led to major advancements. The work to improve the care provided in the clinic and at the bedside will continue through one collective approach in the new normal.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

1. Liesching TN, Lei Y. Oxygen therapies and clinical outcomes for patients hospitalized with covid-19: first surge vs second surge. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2022;29(2):58-64. doi:10.12788/jcom.0086

2. Ali SH, Hyer S, Davis K, Murrow JR. Acute STEMI during the COVID-19 pandemic at Piedmont Athens Regional: incidence, clinical characteristics, and outcomes. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2022;29(2):65-71. doi:10.12788/jcom.0085

3. Cusick A, Hanigan S, Bashaw L, et al. A practical and cost-effective approach to the diagnosis of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: a single-center quality improvement study. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2022;29(2):72-77.

4. Sosa MA, Ferreira T, Gershengorn H, et al. Improving hospital metrics through the implementation of a comorbidity capture tool and other quality initiatives. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2022;29(2):80-87. doi:10.12788/jcom.00885. Uche JU, Jamison M, Waugh S. Evaluation of the Empower Veterans Program for military veterans with chronic pain. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2022;29(2):88-95. doi:10.12788/jcom.0089

1. Liesching TN, Lei Y. Oxygen therapies and clinical outcomes for patients hospitalized with covid-19: first surge vs second surge. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2022;29(2):58-64. doi:10.12788/jcom.0086

2. Ali SH, Hyer S, Davis K, Murrow JR. Acute STEMI during the COVID-19 pandemic at Piedmont Athens Regional: incidence, clinical characteristics, and outcomes. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2022;29(2):65-71. doi:10.12788/jcom.0085

3. Cusick A, Hanigan S, Bashaw L, et al. A practical and cost-effective approach to the diagnosis of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: a single-center quality improvement study. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2022;29(2):72-77.

4. Sosa MA, Ferreira T, Gershengorn H, et al. Improving hospital metrics through the implementation of a comorbidity capture tool and other quality initiatives. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2022;29(2):80-87. doi:10.12788/jcom.00885. Uche JU, Jamison M, Waugh S. Evaluation of the Empower Veterans Program for military veterans with chronic pain. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2022;29(2):88-95. doi:10.12788/jcom.0089

Simulation-Based Training in Medical Education: Immediate Growth or Cautious Optimism?

For years, professional athletes have used simulation-based training (SBT), a combination of virtual and experiential learning that aims to optimize technical skills, teamwork, and communication.1 In SBT, critical plays and skills are first watched on video or reviewed on a chalkboard, and then run in the presence of a coach who offers immediate feedback to the player. The hope is that the individual will then be able to perfectly execute that play or scenario when it is game time. While SBT is a developing tool in medical education—allowing learners to practice important clinical skills prior to practicing in the higher-stakes clinical environment—an important question remains: what training can go virtual and what needs to stay in person?

In this issue, Carter et al2 present a single-site, telesimulation curriculum that addresses consult request and handoff communication using SBT. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the authors converted an in-person intern bootcamp into a virtual, Zoom®-based workshop and compared assessments and evaluations to the previous year’s (2019) in-person bootcamp. Compared to the in-person class, the telesimulation-based cohort were equally or better trained in the consult request portion of the workshop. However, participants were significantly less likely to perform the assessed handoff skills optimally, with only a quarter (26%) appropriately prioritizing patients and less than half (49%) providing an appropriate amount of information in the patient summary. Additionally, postworkshop surveys found that SBT participants were more satisfied with their performance in both the consult request and handoff scenarios and felt more prepared (99% vs 91%) to perform handoffs in clinical practice compared to the previous year’s in-person cohort.

We focus on this work as it explores the role that SBT or virtual training could have in hospital communication and patient safety training. While previous work has highlighted that technical and procedural skills often lend themselves to in-person adaptation (eg, point-of-care ultrasound), this work suggests that nontechnical skills training could be adapted to the virtual environment. Hospitalists and internal medicine trainees perform a myriad of nontechnical activities, such as end-of-life discussions, obtaining informed consent, providing peer-to-peer feedback, and leading multidisciplinary teams. Activities like these, which require no hands-on interactions, may be well-suited for simulation or virtual-based training.3

However, we make this suggestion with some caution. In Carter et al’s study,2 while we assumed that telesimulation would work for the handoff portion of the workshop, interestingly, the telesimulation-based cohort performed worse than the interns who participated in the previous year’s in-person training while simultaneously and paradoxically reporting that they felt more prepared. The authors offer several possible explanations, including alterations in the assessment checklist and a shift in the facilitators from peer observers to faculty hospitalists. We suspect that differences in the participants’ experiences prior to the bootcamp may also be at play. Given the onset of the pandemic during their final year in undergraduate training, many in this intern cohort were likely removed from their fourth-year clinical clerkships,4 taking from them pivotal opportunities to hone and refine this skill set prior to starting their graduate medical education.

As telesimulation and other virtual care educational opportunities continue to evolve, we must ensure that such training does not sacrifice quality for ease and satisfaction. As the authors’ findings show, simply replicating an in-person curriculum in a virtual environment does not ensure equivalence for all skill sets. We remain cautiously optimistic that as we adjust to a postpandemic world, more SBT and virtual-based educational interventions will allow medical trainees to be ready to perform come game time.

1. McCaskill S. Sports tech comes of age with VR training, coaching apps and smart gear. Forbes. March 31, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/stevemccaskill/2020/03/31/sports-tech-comes-of-age-with-vr-training-coaching-apps-and-smart-gear/?sh=309a8fa219c9

2. Carter K, Podczerwinski J, Love L, et al. Utilizing telesimulation for advanced skills training in consultation and handoff communication: a post-COVID-19 GME bootcamp experience. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(12)730-734. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3733

3. Paige JT, Sonesh SC, Garbee DD, Bonanno LS. Comprensive Healthcare Simulation: Interprofessional Team Training and Simulation. 1st ed. Springer International Publishing; 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28845-7

4. Goldenberg MN, Hersh DC, Wilkins KM, Schwartz ML. Suspending medical student clerkships due to COVID-19. Med Sci Educ. 2020;30(3):1-4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-020-00994-1

For years, professional athletes have used simulation-based training (SBT), a combination of virtual and experiential learning that aims to optimize technical skills, teamwork, and communication.1 In SBT, critical plays and skills are first watched on video or reviewed on a chalkboard, and then run in the presence of a coach who offers immediate feedback to the player. The hope is that the individual will then be able to perfectly execute that play or scenario when it is game time. While SBT is a developing tool in medical education—allowing learners to practice important clinical skills prior to practicing in the higher-stakes clinical environment—an important question remains: what training can go virtual and what needs to stay in person?

In this issue, Carter et al2 present a single-site, telesimulation curriculum that addresses consult request and handoff communication using SBT. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the authors converted an in-person intern bootcamp into a virtual, Zoom®-based workshop and compared assessments and evaluations to the previous year’s (2019) in-person bootcamp. Compared to the in-person class, the telesimulation-based cohort were equally or better trained in the consult request portion of the workshop. However, participants were significantly less likely to perform the assessed handoff skills optimally, with only a quarter (26%) appropriately prioritizing patients and less than half (49%) providing an appropriate amount of information in the patient summary. Additionally, postworkshop surveys found that SBT participants were more satisfied with their performance in both the consult request and handoff scenarios and felt more prepared (99% vs 91%) to perform handoffs in clinical practice compared to the previous year’s in-person cohort.

We focus on this work as it explores the role that SBT or virtual training could have in hospital communication and patient safety training. While previous work has highlighted that technical and procedural skills often lend themselves to in-person adaptation (eg, point-of-care ultrasound), this work suggests that nontechnical skills training could be adapted to the virtual environment. Hospitalists and internal medicine trainees perform a myriad of nontechnical activities, such as end-of-life discussions, obtaining informed consent, providing peer-to-peer feedback, and leading multidisciplinary teams. Activities like these, which require no hands-on interactions, may be well-suited for simulation or virtual-based training.3

However, we make this suggestion with some caution. In Carter et al’s study,2 while we assumed that telesimulation would work for the handoff portion of the workshop, interestingly, the telesimulation-based cohort performed worse than the interns who participated in the previous year’s in-person training while simultaneously and paradoxically reporting that they felt more prepared. The authors offer several possible explanations, including alterations in the assessment checklist and a shift in the facilitators from peer observers to faculty hospitalists. We suspect that differences in the participants’ experiences prior to the bootcamp may also be at play. Given the onset of the pandemic during their final year in undergraduate training, many in this intern cohort were likely removed from their fourth-year clinical clerkships,4 taking from them pivotal opportunities to hone and refine this skill set prior to starting their graduate medical education.

As telesimulation and other virtual care educational opportunities continue to evolve, we must ensure that such training does not sacrifice quality for ease and satisfaction. As the authors’ findings show, simply replicating an in-person curriculum in a virtual environment does not ensure equivalence for all skill sets. We remain cautiously optimistic that as we adjust to a postpandemic world, more SBT and virtual-based educational interventions will allow medical trainees to be ready to perform come game time.

For years, professional athletes have used simulation-based training (SBT), a combination of virtual and experiential learning that aims to optimize technical skills, teamwork, and communication.1 In SBT, critical plays and skills are first watched on video or reviewed on a chalkboard, and then run in the presence of a coach who offers immediate feedback to the player. The hope is that the individual will then be able to perfectly execute that play or scenario when it is game time. While SBT is a developing tool in medical education—allowing learners to practice important clinical skills prior to practicing in the higher-stakes clinical environment—an important question remains: what training can go virtual and what needs to stay in person?

In this issue, Carter et al2 present a single-site, telesimulation curriculum that addresses consult request and handoff communication using SBT. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the authors converted an in-person intern bootcamp into a virtual, Zoom®-based workshop and compared assessments and evaluations to the previous year’s (2019) in-person bootcamp. Compared to the in-person class, the telesimulation-based cohort were equally or better trained in the consult request portion of the workshop. However, participants were significantly less likely to perform the assessed handoff skills optimally, with only a quarter (26%) appropriately prioritizing patients and less than half (49%) providing an appropriate amount of information in the patient summary. Additionally, postworkshop surveys found that SBT participants were more satisfied with their performance in both the consult request and handoff scenarios and felt more prepared (99% vs 91%) to perform handoffs in clinical practice compared to the previous year’s in-person cohort.