User login

Where Have All the Medicare Inpatients Gone?

The advent of COVID-19 saw a precipitous decline in inpatient admissions. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals were seeing a trend toward fewer inpatient admissions for Medicare beneficiaries, which has not been thoroughly examined or explained.1 In this issue, Keohane et al2 studied Medicare inpatient episode trends between 2009 and 2017 and found that, during this period, inpatient episodes per 1000 Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries declined by 18.2%, from 326 to 267 per 1000 beneficiaries.

This trend can be partly explained by changes in the way that care is delivered. First, observation stays have risen, and these are excluded in the authors’ analysis. From 2010 to 2017, observation visits per 1000 beneficiaries increased from 28 to 51.1 Second, due to improved outpatient management, margin constraints, and efficiency gains, hospitals are less likely to admit patients with less complex problems or keep patients overnight for uncomplicated procedural interventions. In cardiology, there has been an increase in the proportion of same-day percutaneous coronary interventions, from 4.5% in 2009 to 28.6% in 2017.3 The authors do not include a quantitative measure of complexity, but their data support this conclusion as they find larger declines in episodes that began with a planned admission and those that involved no use of post–acute care services, and thus were likely less complicated admissions. Finally, the increased use of alternative care sites such as home-based care settings and urgent care clinics, the proliferation of telemedicine, and the continual development of guideline-based therapy have resulted in better outpatient management of diseases.

The growth of value-based care has also contributed to the reduction in inpatient admission. The past decade has seen the growth of bundled-payment contracts, accountable care organizations (ACO), and advanced primary care models. In 2018, an estimated 20% of Medicare beneficiaries were part of an ACO.4 These changes have led healthcare systems to invest in care management and postdischarge interventions, such as postdischarge phone calls, transitional clinics, and transition guides to reduce admissions and readmissions. Johns Hopkins adopted all these strategies to drive performance on the Maryland Total Cost of Care Model, which like an ACO holds hospitals accountable for both inpatient and outpatient costs incurred by Medicare FFS beneficiaries. A consistent theme among successful ACOs has been a reduction in inpatient spending.5

The authors are likely undercounting the volume of admissions by Medicare beneficiaries. First, to define an episode, they leverage the Medicare definition of bundles and include traditional Medicare inpatient, outpatient, and Part D services 30 days prior to hospitalizations and up to 90 days after. Admissions for the same diagnosis related group that occur in the 90 days after the anchor hospitalization are included in the same episode. From a clinical perspective, it is not intuitively clear why an admission for heart failure or pneumonia that occurs 3 months after an anchor hospitalization would not be defined as a separate and distinct admission rather than a readmission. Second, their analysis focuses on Medicare FFS and does not include Medicare Advantage, which now accounts for 42% of total Medicare beneficiaries. In fact, Medicare Advantage experienced significant growth in enrollment during the study period, increasing from 10 million to 24 million beneficiaries.6

Despite the reduction in inpatient volumes, the authors find that inpatient spending has increased. Spending per episode increased by 11.4% over this period, when adjusted for Medicare payment increases. Actual spending per episode unadjusted for payment increases rose by 25%. Thus, they astutely point out that most of the increase has been driven by Medicare payment increases. It is likely that increases in the complexity of patients and more dedicated focus on appropriate coding have also contributed. The authors, however, do not provide information on changes to the total cost of care outside of their defined inpatient episodes, a relevant measure to those participating in value-based models.

It is likely that the trend toward fewer inpatient admissions and increased outpatient management of medical conditions will continue as value-based care models grow. Studies like these are important in documenting this trend, but it will be important in future studies to understand how these changes have impacted the quality of care delivered to patients. Prior studies have found that reductions in readmissions through the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program were associated with increases in mortality as a potential unintended consequence.7

1. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. A Data Book: Health Care Spending and the Medicare Program. June 2018. Accessed October 25, 2021. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/data-book/jun19_databook_entirereport_sec.pdf

2. Keohane LM, Kripalani S, Buntin MB, et al. Traditional Medicare spending on inpatient episodes as hospitalizations decline. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(11):652-658. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3699

3. Bradley SM, Kaltenbach LA, Xiang K, et al. Trends in use and outcomes of same-day discharge following elective percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14(15):1655-1666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2021.05.043

4. National Association of ACOs. NAACOs overview of the 2018 Medicare ACO class. Accessed October 25, 2021. https://www.naacos.com/overview-of-the-2018-medicare-aco-class

5. McWilliams JM, Hatfield LA, Landon BE, Hamed P, Chernew ME. Medicare spending after 3 years of the Medicare shared savings program. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(12):1139-1149. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1803388

6. Freed M, Fuglesten Biniek J, Damico A, Neuman T. Medicare Advantage in 2021: Enrollment update and key trends. KFF. June 21, 2021. Accessed October 25, 2021. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-in-2021-enrollment-update-and-key-trends/

7. Gupta A, Allen LA, Bhatt DL, et al. Association of the hospital readmissions reduction program implementation with readmission and mortality outcomes in heart failure. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(1):44-53. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2017.4265

The advent of COVID-19 saw a precipitous decline in inpatient admissions. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals were seeing a trend toward fewer inpatient admissions for Medicare beneficiaries, which has not been thoroughly examined or explained.1 In this issue, Keohane et al2 studied Medicare inpatient episode trends between 2009 and 2017 and found that, during this period, inpatient episodes per 1000 Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries declined by 18.2%, from 326 to 267 per 1000 beneficiaries.

This trend can be partly explained by changes in the way that care is delivered. First, observation stays have risen, and these are excluded in the authors’ analysis. From 2010 to 2017, observation visits per 1000 beneficiaries increased from 28 to 51.1 Second, due to improved outpatient management, margin constraints, and efficiency gains, hospitals are less likely to admit patients with less complex problems or keep patients overnight for uncomplicated procedural interventions. In cardiology, there has been an increase in the proportion of same-day percutaneous coronary interventions, from 4.5% in 2009 to 28.6% in 2017.3 The authors do not include a quantitative measure of complexity, but their data support this conclusion as they find larger declines in episodes that began with a planned admission and those that involved no use of post–acute care services, and thus were likely less complicated admissions. Finally, the increased use of alternative care sites such as home-based care settings and urgent care clinics, the proliferation of telemedicine, and the continual development of guideline-based therapy have resulted in better outpatient management of diseases.

The growth of value-based care has also contributed to the reduction in inpatient admission. The past decade has seen the growth of bundled-payment contracts, accountable care organizations (ACO), and advanced primary care models. In 2018, an estimated 20% of Medicare beneficiaries were part of an ACO.4 These changes have led healthcare systems to invest in care management and postdischarge interventions, such as postdischarge phone calls, transitional clinics, and transition guides to reduce admissions and readmissions. Johns Hopkins adopted all these strategies to drive performance on the Maryland Total Cost of Care Model, which like an ACO holds hospitals accountable for both inpatient and outpatient costs incurred by Medicare FFS beneficiaries. A consistent theme among successful ACOs has been a reduction in inpatient spending.5

The authors are likely undercounting the volume of admissions by Medicare beneficiaries. First, to define an episode, they leverage the Medicare definition of bundles and include traditional Medicare inpatient, outpatient, and Part D services 30 days prior to hospitalizations and up to 90 days after. Admissions for the same diagnosis related group that occur in the 90 days after the anchor hospitalization are included in the same episode. From a clinical perspective, it is not intuitively clear why an admission for heart failure or pneumonia that occurs 3 months after an anchor hospitalization would not be defined as a separate and distinct admission rather than a readmission. Second, their analysis focuses on Medicare FFS and does not include Medicare Advantage, which now accounts for 42% of total Medicare beneficiaries. In fact, Medicare Advantage experienced significant growth in enrollment during the study period, increasing from 10 million to 24 million beneficiaries.6

Despite the reduction in inpatient volumes, the authors find that inpatient spending has increased. Spending per episode increased by 11.4% over this period, when adjusted for Medicare payment increases. Actual spending per episode unadjusted for payment increases rose by 25%. Thus, they astutely point out that most of the increase has been driven by Medicare payment increases. It is likely that increases in the complexity of patients and more dedicated focus on appropriate coding have also contributed. The authors, however, do not provide information on changes to the total cost of care outside of their defined inpatient episodes, a relevant measure to those participating in value-based models.

It is likely that the trend toward fewer inpatient admissions and increased outpatient management of medical conditions will continue as value-based care models grow. Studies like these are important in documenting this trend, but it will be important in future studies to understand how these changes have impacted the quality of care delivered to patients. Prior studies have found that reductions in readmissions through the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program were associated with increases in mortality as a potential unintended consequence.7

The advent of COVID-19 saw a precipitous decline in inpatient admissions. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals were seeing a trend toward fewer inpatient admissions for Medicare beneficiaries, which has not been thoroughly examined or explained.1 In this issue, Keohane et al2 studied Medicare inpatient episode trends between 2009 and 2017 and found that, during this period, inpatient episodes per 1000 Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries declined by 18.2%, from 326 to 267 per 1000 beneficiaries.

This trend can be partly explained by changes in the way that care is delivered. First, observation stays have risen, and these are excluded in the authors’ analysis. From 2010 to 2017, observation visits per 1000 beneficiaries increased from 28 to 51.1 Second, due to improved outpatient management, margin constraints, and efficiency gains, hospitals are less likely to admit patients with less complex problems or keep patients overnight for uncomplicated procedural interventions. In cardiology, there has been an increase in the proportion of same-day percutaneous coronary interventions, from 4.5% in 2009 to 28.6% in 2017.3 The authors do not include a quantitative measure of complexity, but their data support this conclusion as they find larger declines in episodes that began with a planned admission and those that involved no use of post–acute care services, and thus were likely less complicated admissions. Finally, the increased use of alternative care sites such as home-based care settings and urgent care clinics, the proliferation of telemedicine, and the continual development of guideline-based therapy have resulted in better outpatient management of diseases.

The growth of value-based care has also contributed to the reduction in inpatient admission. The past decade has seen the growth of bundled-payment contracts, accountable care organizations (ACO), and advanced primary care models. In 2018, an estimated 20% of Medicare beneficiaries were part of an ACO.4 These changes have led healthcare systems to invest in care management and postdischarge interventions, such as postdischarge phone calls, transitional clinics, and transition guides to reduce admissions and readmissions. Johns Hopkins adopted all these strategies to drive performance on the Maryland Total Cost of Care Model, which like an ACO holds hospitals accountable for both inpatient and outpatient costs incurred by Medicare FFS beneficiaries. A consistent theme among successful ACOs has been a reduction in inpatient spending.5

The authors are likely undercounting the volume of admissions by Medicare beneficiaries. First, to define an episode, they leverage the Medicare definition of bundles and include traditional Medicare inpatient, outpatient, and Part D services 30 days prior to hospitalizations and up to 90 days after. Admissions for the same diagnosis related group that occur in the 90 days after the anchor hospitalization are included in the same episode. From a clinical perspective, it is not intuitively clear why an admission for heart failure or pneumonia that occurs 3 months after an anchor hospitalization would not be defined as a separate and distinct admission rather than a readmission. Second, their analysis focuses on Medicare FFS and does not include Medicare Advantage, which now accounts for 42% of total Medicare beneficiaries. In fact, Medicare Advantage experienced significant growth in enrollment during the study period, increasing from 10 million to 24 million beneficiaries.6

Despite the reduction in inpatient volumes, the authors find that inpatient spending has increased. Spending per episode increased by 11.4% over this period, when adjusted for Medicare payment increases. Actual spending per episode unadjusted for payment increases rose by 25%. Thus, they astutely point out that most of the increase has been driven by Medicare payment increases. It is likely that increases in the complexity of patients and more dedicated focus on appropriate coding have also contributed. The authors, however, do not provide information on changes to the total cost of care outside of their defined inpatient episodes, a relevant measure to those participating in value-based models.

It is likely that the trend toward fewer inpatient admissions and increased outpatient management of medical conditions will continue as value-based care models grow. Studies like these are important in documenting this trend, but it will be important in future studies to understand how these changes have impacted the quality of care delivered to patients. Prior studies have found that reductions in readmissions through the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program were associated with increases in mortality as a potential unintended consequence.7

1. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. A Data Book: Health Care Spending and the Medicare Program. June 2018. Accessed October 25, 2021. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/data-book/jun19_databook_entirereport_sec.pdf

2. Keohane LM, Kripalani S, Buntin MB, et al. Traditional Medicare spending on inpatient episodes as hospitalizations decline. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(11):652-658. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3699

3. Bradley SM, Kaltenbach LA, Xiang K, et al. Trends in use and outcomes of same-day discharge following elective percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14(15):1655-1666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2021.05.043

4. National Association of ACOs. NAACOs overview of the 2018 Medicare ACO class. Accessed October 25, 2021. https://www.naacos.com/overview-of-the-2018-medicare-aco-class

5. McWilliams JM, Hatfield LA, Landon BE, Hamed P, Chernew ME. Medicare spending after 3 years of the Medicare shared savings program. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(12):1139-1149. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1803388

6. Freed M, Fuglesten Biniek J, Damico A, Neuman T. Medicare Advantage in 2021: Enrollment update and key trends. KFF. June 21, 2021. Accessed October 25, 2021. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-in-2021-enrollment-update-and-key-trends/

7. Gupta A, Allen LA, Bhatt DL, et al. Association of the hospital readmissions reduction program implementation with readmission and mortality outcomes in heart failure. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(1):44-53. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2017.4265

1. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. A Data Book: Health Care Spending and the Medicare Program. June 2018. Accessed October 25, 2021. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/data-book/jun19_databook_entirereport_sec.pdf

2. Keohane LM, Kripalani S, Buntin MB, et al. Traditional Medicare spending on inpatient episodes as hospitalizations decline. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(11):652-658. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3699

3. Bradley SM, Kaltenbach LA, Xiang K, et al. Trends in use and outcomes of same-day discharge following elective percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14(15):1655-1666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2021.05.043

4. National Association of ACOs. NAACOs overview of the 2018 Medicare ACO class. Accessed October 25, 2021. https://www.naacos.com/overview-of-the-2018-medicare-aco-class

5. McWilliams JM, Hatfield LA, Landon BE, Hamed P, Chernew ME. Medicare spending after 3 years of the Medicare shared savings program. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(12):1139-1149. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1803388

6. Freed M, Fuglesten Biniek J, Damico A, Neuman T. Medicare Advantage in 2021: Enrollment update and key trends. KFF. June 21, 2021. Accessed October 25, 2021. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-in-2021-enrollment-update-and-key-trends/

7. Gupta A, Allen LA, Bhatt DL, et al. Association of the hospital readmissions reduction program implementation with readmission and mortality outcomes in heart failure. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(1):44-53. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2017.4265

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value: Postacute Care Transitions: Developing a Skilled Nursing Facility Collaborative within an Academic Health System

Hospitals and health systems are under mounting financial pressure to shorten hospitalizations and reduce readmissions. These priorities have led to an ever-increasing focus on postacute care (PAC), and more specifically on improving transitions from the hospital.1,2 According to a 2013 Institute of Medicine report, PAC is the source of 73% of the variation in Medicare spending3 and readmissions during the postacute episode nearly double the average Medicare payment.4 Within the PAC landscape, discharges to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) have received particular focus due to the high rates of readmission and associated care costs.5

Hospitals, hospital physicians, PAC providers, and payers need to improve SNF transitions in care. Hospitals are increasingly responsible for patient care beyond their walls through several mechanisms including rehospitalization penalties, value-based reimbursement strategies (eg, bundled payments), and risk-based contracting on the total cost of care through relationships with accountable care organizations (ACOs) and Medicare Advantage plans. Similarly, hospital-employed physicians and PAC providers are more engaged in achieving value-based goals through increased alignment of provider compensation models6,7 with risk-based contracting.

Current evidence suggests that rehospitalizations could be reduced by focusing on a concentrated referral network of preferred high-quality SNFs;8,9 however, less is known about how to develop and operate such linkages at the administrative or clinical levels.8 In this article, we propose a collaborative framework for the establishment of a preferred PAC network.

SKILLED NURSING FACILITY PREFERRED PROVIDER NETWORK

One mechanism employed to improve transitions to SNFs and reduce associated readmissions is to create a preferred provider network. Increasing the concentration of hospital discharges to higher performing facilities is associated with lower rehospitalization rates, particularly during the critical days following discharge.10

While the criteria applied for preferred provider networks vary, there are several emerging themes.10 Quality metrics are often applied, generally starting with Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) quality star ratings and Long-Term Care Minimum Data Set (MDS) metrics with additional criteria frequently layered upon those. Some examples include the extent of physician coverage,11 the extent of nursing coverage (eg, nursing ratios or 24/7 nursing care), geographic access, and flexible admission times (including weekends and nights).12 In addition, several outcome measures may be used such as 30-day readmission rates, patient/family satisfaction ratings, ED visits, primary care follow-up within seven days of PAC discharge, or impact on the total cost of care.

Beyond the specified criteria, some hospitals choose to build upon existing relationships when developing their preferred network. By selecting historically high-volume facilities, they are able to leverage the existing name recognition amongst patients and providers.13 This minimizes retraining of discharge planners, maintains institutional relationships, and aligns with the patients’ geographic preferences.2,13 While the high volume SNFs may not have the highest quality ratings, some hospitals find they can leverage the value of preferred partner status to push behavior change and improve performance.13

PROPOSED HEALTH SYSTEM FRAMEWORK FOR CREATING A SKILLED NURSING FACILITY COLLABORATIVE

Here we propose a framework for the establishment of a preferred provider network for a hospital or health system based on the early experience of establishing an SNF Collaborative within Johns Hopkins Medicine (JHM). JHM is a large integrated health care system, which includes five hospitals within the region, including two large academic hospitals and three community hospitals serving patients in Maryland and the District of Columbia.14

JHM identified a need for improved coordination with PAC providers and saw opportunities to build upon successful individual hospital efforts to create a system-level approach with a PAC partnership sharing the goals of improving care and reducing costs. Additional opportunities exist given the unique Maryland all-payer Global Budget Revenue system managed by the Health Services Cost Review Commission. This system imposes hospital-level penalties for readmissions or poor quality measure performance and is moving to a new phase that will place hospitals directly at risk for the total Part A and Part B Medicare expenditures for a cohort of attributed Medicare patients, inclusive of their PAC expenses. This state-wide program is one example of a shift in payment structures from volume to value that is occurring throughout the healthcare sector.

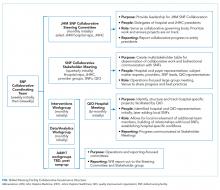

Developing a formal collaboration inclusive of the five local hospitals, Johns Hopkins HealthCare (JHHC)—the managed care division of JHM—and the JHM ACO (Johns Hopkins Medicine Alliance for Patients, JMAP), we established a JHM SNF Collaborative. This group was tasked with improving the continuum of care for our patients discharged to PAC facilities. Given the number and diversity of entities involved, we sought to draw on efforts already managed and piloted locally, while disseminating best practices and providing added services at the collaborative level. We propose a collaborative multistakeholder model (Figure) that we anticipate will be adaptable to other health systems.

At the outset, we established a Steering Committee and a broad Stakeholder Group (Figure). The Steering Committee is comprised of representatives from all participating JHM entities and serves as the collaborative governing body. This group initially identified 36 local SNF partners including a mixture of larger corporate chains and freestanding entities. In an effort to respect patient choice and acknowledge geographic preferences and capacity limitations, partner selection was based on a combination of publically available quality metrics, historic referral volumes, and recommendations of each JHM hospital. While we sought to align with high-performing SNFs, we also saw an opportunity to leverage collaboration to drive improvement in lower-performing facilities that continue to receive a high volume of referrals. The Stakeholder Group includes a broader representation from JHM, including subject matter experts from related medical specialties (eg, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Internal Medicine, Emergency Medicine, and various surgical subspecialties); partner SNFs, and the local CMS-funded Quality Improvement Organization (QIO). Physician leadership was essential at all levels of the collaborative governing structure including the core Coordinating Team (Figure). Providers representing different hospitals were able to speak about variations in practice patterns and to assess the feasibility of suggested solutions on existing workflows.

After establishing the governance framework for the collaborative, it was determined that dedicated workgroups were needed to drive protocol-based initiatives, data, and analytics. For the former, we selected transitions of care as our initial focus area. All affiliated hospitals were working to address care transitions, but there were opportunities to develop a harmonized approach leveraging individual hospital input. The workgroup included representation from medical and administrative hospital leadership, JHHC, JMAP, our home care group, and SNF medical leadership. Initial priorities identified are reviewed in the Table. We anticipate new priorities for the collaborative over time and intend for the workgroup to evolve in line with shifting priorities.

We similarly established a multidisciplinary data and analytics workgroup to identify resources to develop the SNF, and a system-level dashboard to track our ongoing work. While incorporating data from five hospitals with varied patient populations, we felt that the risk-adjusted PAC data were critical to the collaborative establishment and goal setting. After exploring internal and external resources, we initially elected to engage an outside vendor offering risk-adjusted performance metrics. We have subsequently worked with the state health information exchange, CRISP,15 to develop a robust dashboard for Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries that could provide similar data.

IMPLEMENTATION

In the process of establishing the SNF Collaborative at JHM, there were a number of early challenges faced and lessons learned:

- In a large integrated delivery system, there is a need to balance the benefits of central coordination with the support for ongoing local efforts to promote partner engagement at the hospital and SNF level. The forums created within the collaborative governance structure can facilitate sharing of the prior health system, hospital or SNF initiatives to grow upon successes and avoid prior pitfalls.

- Early identification of risk-adjusted PAC data sources is central to the collaborative establishment and goal setting. This requires assessment of internal analytic resources, budget, and desired timeline for implementation to determine the optimal arrangement. Similarly, identification of available data sources to drive the analytic efforts is essential and should include a health information exchange, claims, and MDS among others.

- Partnering with local QIOs provides support for facility-level quality improvement efforts. They have the staff and onsite expertise to facilitate process implementation within individual SNFs.

- Larger preferred provider networks require considerable administrative support to facilitate communication with the entities, coordinate completion of network agreements, and manage the dissemination of SNF- and hospital-specific performance data.

- Legal and contractual support related to data sharing and HIPAA compliance is needed due to the complexity of the health system and SNF legal structure. Multiple JHM legal entities were involved in this collaborative as were a mixture of freestanding SNFs and corporate chains. There was a significant effort required to execute both data-sharing agreements as well as charters to enable QIO participation.

- Physician leadership and insight are key to implementing meaningful and broad change. When devising system-wide solutions, incorporation and respect for local processes and needs are paramount for provider engagement and behavior change. This process will likely identify gaps in understanding the PAC patient’s experience and needs. It may also reveal practice variability and foster opportunities for provider education on the needs of PAC teams and how to best facilitate quality transitions.

CONCLUSION

We proposed a framework for establishing a collaborative partnership with a preferred network of SNF providers. Depending on organizational readiness, significant upfront investment of time and resources could be needed to establish a coordinated network of SNF providers. However, once established, such networks can be leveraged to support ongoing process improvement efforts within a hospital or delivery system and can be used strategically by such health systems as they implement value-based health strategies. Furthermore, the lessons learned from transitions to SNFs can be applied more broadly in the PAC landscape including transitions to home from both the hospital and SNF.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge all the members and participants in the Johns Hopkins Medicine Skilled Nursing Facility Collaborative and the executive sponsors and JHM hospital presidents for their support of this work.

Disclosures

Michele Bellantoni receives intramural salary support for being the medical director of the JHM SNF Collaborative. Damien Doyle is a part-time geriatrician at the Hebrew Home of Greater Washington, a skilled nursing facility. He received travel expense support for GAPNA, a local Advanced Practice Nurse Association meeting.The authors otherwise have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

The authors state that there were no external sponsors for this work.

1. Burke RE, Whitfield EA, Hittle D, et al. Hospital readmission from post-acute care facilities: risk factors, timing, and outcomes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(3):249-255. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2015.11.005. PubMed

2. Mchugh JP, Zinn J, Shield RR, et al. Strategy and risk sharing in hospital–post-acute care integration. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018:1. doi:10.1097/hmr.0000000000000204. PubMed

3. Institute of Medicine. Variation in Health Care Spending Assessing Geographic Variation.; 2013. http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report Files/2013/Geographic-Variation2/geovariation_rb.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2018.

4. Dobson A, DaVanzo JE, Heath S, et al. Medicare Payment Bundling: Insights from Claims Data and Policy Implications Analyses of Episode-Based Payment. Washington, DC; 2012. http://www.aha.org/content/12/ahaaamcbundlingreport.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2018.

5. Mor V, Intrator O, Feng Z, Grabowski DC. The revolving door of rehospitalization from skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff. 2010;29(1):57-64. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0629. PubMed

6. Torchiana DF, Colton DG, Rao SK, Lenz SK, Meyer GS, Ferris TG. Massachusetts general physicians organization’s quality incentive program produces encouraging results. Health Aff. 2013;32(10):1748-1756. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0377. PubMed

7. Michtalik HJ, Carolan HT, Haut ER, et al. Use of provider-level dashboards and pay-for-performance in venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. J Hosp Med. 2014;10(3):172-178. doi:10.1002/jhm.2303. PubMed

8. Rahman M, Foster AD, Grabowski DC, Zinn JS, Mor V. Effect of hospital-SNF referral linkages on rehospitalization. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6pt1):1898-1919. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12112. PubMed

9. Huckfeldt PJ, Weissblum L, Escarce JJ, Karaca-Mandic P, Sood N. Do skilled nursing facilities selected to participate in preferred provider networks have higher quality and lower costs? Health Serv Res. 2018. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13027. PubMed

10. American Hospital Association. The role of post-acute care in new care delivery models. TrendWatch. http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/15dec-tw-postacute.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed December 19, 2017.

11. Lage DE, Rusinak D, Carr D, Grabowski DC, Ackerly DC. Creating a network of high-quality skilled nursing facilities: preliminary data on the postacute care quality improvement experiences of an accountable care organization. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(4):804-808. doi:10.1111/jgs.13351. PubMed

12. Ouslander JG, Bonner A, Herndon L, Shutes J. The Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers (INTERACT) quality improvement program: an overview for medical directors and primary care clinicians in long-term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(3):162-170. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2013.12.005. PubMed

13. McHugh JP, Foster A, Mor V, et al. Reducing hospital readmissions through preferred networks of skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff. 2017;36(9):1591-1598. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0211. PubMed

14. Fast Facts: Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/about/downloads/JHM-Fast-Facts.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2018.

15. CRISP – Chesapeake Regional Information System for our Patients. https://www.crisphealth.org/. Accessed October 17, 2018.

Hospitals and health systems are under mounting financial pressure to shorten hospitalizations and reduce readmissions. These priorities have led to an ever-increasing focus on postacute care (PAC), and more specifically on improving transitions from the hospital.1,2 According to a 2013 Institute of Medicine report, PAC is the source of 73% of the variation in Medicare spending3 and readmissions during the postacute episode nearly double the average Medicare payment.4 Within the PAC landscape, discharges to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) have received particular focus due to the high rates of readmission and associated care costs.5

Hospitals, hospital physicians, PAC providers, and payers need to improve SNF transitions in care. Hospitals are increasingly responsible for patient care beyond their walls through several mechanisms including rehospitalization penalties, value-based reimbursement strategies (eg, bundled payments), and risk-based contracting on the total cost of care through relationships with accountable care organizations (ACOs) and Medicare Advantage plans. Similarly, hospital-employed physicians and PAC providers are more engaged in achieving value-based goals through increased alignment of provider compensation models6,7 with risk-based contracting.

Current evidence suggests that rehospitalizations could be reduced by focusing on a concentrated referral network of preferred high-quality SNFs;8,9 however, less is known about how to develop and operate such linkages at the administrative or clinical levels.8 In this article, we propose a collaborative framework for the establishment of a preferred PAC network.

SKILLED NURSING FACILITY PREFERRED PROVIDER NETWORK

One mechanism employed to improve transitions to SNFs and reduce associated readmissions is to create a preferred provider network. Increasing the concentration of hospital discharges to higher performing facilities is associated with lower rehospitalization rates, particularly during the critical days following discharge.10

While the criteria applied for preferred provider networks vary, there are several emerging themes.10 Quality metrics are often applied, generally starting with Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) quality star ratings and Long-Term Care Minimum Data Set (MDS) metrics with additional criteria frequently layered upon those. Some examples include the extent of physician coverage,11 the extent of nursing coverage (eg, nursing ratios or 24/7 nursing care), geographic access, and flexible admission times (including weekends and nights).12 In addition, several outcome measures may be used such as 30-day readmission rates, patient/family satisfaction ratings, ED visits, primary care follow-up within seven days of PAC discharge, or impact on the total cost of care.

Beyond the specified criteria, some hospitals choose to build upon existing relationships when developing their preferred network. By selecting historically high-volume facilities, they are able to leverage the existing name recognition amongst patients and providers.13 This minimizes retraining of discharge planners, maintains institutional relationships, and aligns with the patients’ geographic preferences.2,13 While the high volume SNFs may not have the highest quality ratings, some hospitals find they can leverage the value of preferred partner status to push behavior change and improve performance.13

PROPOSED HEALTH SYSTEM FRAMEWORK FOR CREATING A SKILLED NURSING FACILITY COLLABORATIVE

Here we propose a framework for the establishment of a preferred provider network for a hospital or health system based on the early experience of establishing an SNF Collaborative within Johns Hopkins Medicine (JHM). JHM is a large integrated health care system, which includes five hospitals within the region, including two large academic hospitals and three community hospitals serving patients in Maryland and the District of Columbia.14

JHM identified a need for improved coordination with PAC providers and saw opportunities to build upon successful individual hospital efforts to create a system-level approach with a PAC partnership sharing the goals of improving care and reducing costs. Additional opportunities exist given the unique Maryland all-payer Global Budget Revenue system managed by the Health Services Cost Review Commission. This system imposes hospital-level penalties for readmissions or poor quality measure performance and is moving to a new phase that will place hospitals directly at risk for the total Part A and Part B Medicare expenditures for a cohort of attributed Medicare patients, inclusive of their PAC expenses. This state-wide program is one example of a shift in payment structures from volume to value that is occurring throughout the healthcare sector.

Developing a formal collaboration inclusive of the five local hospitals, Johns Hopkins HealthCare (JHHC)—the managed care division of JHM—and the JHM ACO (Johns Hopkins Medicine Alliance for Patients, JMAP), we established a JHM SNF Collaborative. This group was tasked with improving the continuum of care for our patients discharged to PAC facilities. Given the number and diversity of entities involved, we sought to draw on efforts already managed and piloted locally, while disseminating best practices and providing added services at the collaborative level. We propose a collaborative multistakeholder model (Figure) that we anticipate will be adaptable to other health systems.

At the outset, we established a Steering Committee and a broad Stakeholder Group (Figure). The Steering Committee is comprised of representatives from all participating JHM entities and serves as the collaborative governing body. This group initially identified 36 local SNF partners including a mixture of larger corporate chains and freestanding entities. In an effort to respect patient choice and acknowledge geographic preferences and capacity limitations, partner selection was based on a combination of publically available quality metrics, historic referral volumes, and recommendations of each JHM hospital. While we sought to align with high-performing SNFs, we also saw an opportunity to leverage collaboration to drive improvement in lower-performing facilities that continue to receive a high volume of referrals. The Stakeholder Group includes a broader representation from JHM, including subject matter experts from related medical specialties (eg, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Internal Medicine, Emergency Medicine, and various surgical subspecialties); partner SNFs, and the local CMS-funded Quality Improvement Organization (QIO). Physician leadership was essential at all levels of the collaborative governing structure including the core Coordinating Team (Figure). Providers representing different hospitals were able to speak about variations in practice patterns and to assess the feasibility of suggested solutions on existing workflows.

After establishing the governance framework for the collaborative, it was determined that dedicated workgroups were needed to drive protocol-based initiatives, data, and analytics. For the former, we selected transitions of care as our initial focus area. All affiliated hospitals were working to address care transitions, but there were opportunities to develop a harmonized approach leveraging individual hospital input. The workgroup included representation from medical and administrative hospital leadership, JHHC, JMAP, our home care group, and SNF medical leadership. Initial priorities identified are reviewed in the Table. We anticipate new priorities for the collaborative over time and intend for the workgroup to evolve in line with shifting priorities.

We similarly established a multidisciplinary data and analytics workgroup to identify resources to develop the SNF, and a system-level dashboard to track our ongoing work. While incorporating data from five hospitals with varied patient populations, we felt that the risk-adjusted PAC data were critical to the collaborative establishment and goal setting. After exploring internal and external resources, we initially elected to engage an outside vendor offering risk-adjusted performance metrics. We have subsequently worked with the state health information exchange, CRISP,15 to develop a robust dashboard for Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries that could provide similar data.

IMPLEMENTATION

In the process of establishing the SNF Collaborative at JHM, there were a number of early challenges faced and lessons learned:

- In a large integrated delivery system, there is a need to balance the benefits of central coordination with the support for ongoing local efforts to promote partner engagement at the hospital and SNF level. The forums created within the collaborative governance structure can facilitate sharing of the prior health system, hospital or SNF initiatives to grow upon successes and avoid prior pitfalls.

- Early identification of risk-adjusted PAC data sources is central to the collaborative establishment and goal setting. This requires assessment of internal analytic resources, budget, and desired timeline for implementation to determine the optimal arrangement. Similarly, identification of available data sources to drive the analytic efforts is essential and should include a health information exchange, claims, and MDS among others.

- Partnering with local QIOs provides support for facility-level quality improvement efforts. They have the staff and onsite expertise to facilitate process implementation within individual SNFs.

- Larger preferred provider networks require considerable administrative support to facilitate communication with the entities, coordinate completion of network agreements, and manage the dissemination of SNF- and hospital-specific performance data.

- Legal and contractual support related to data sharing and HIPAA compliance is needed due to the complexity of the health system and SNF legal structure. Multiple JHM legal entities were involved in this collaborative as were a mixture of freestanding SNFs and corporate chains. There was a significant effort required to execute both data-sharing agreements as well as charters to enable QIO participation.

- Physician leadership and insight are key to implementing meaningful and broad change. When devising system-wide solutions, incorporation and respect for local processes and needs are paramount for provider engagement and behavior change. This process will likely identify gaps in understanding the PAC patient’s experience and needs. It may also reveal practice variability and foster opportunities for provider education on the needs of PAC teams and how to best facilitate quality transitions.

CONCLUSION

We proposed a framework for establishing a collaborative partnership with a preferred network of SNF providers. Depending on organizational readiness, significant upfront investment of time and resources could be needed to establish a coordinated network of SNF providers. However, once established, such networks can be leveraged to support ongoing process improvement efforts within a hospital or delivery system and can be used strategically by such health systems as they implement value-based health strategies. Furthermore, the lessons learned from transitions to SNFs can be applied more broadly in the PAC landscape including transitions to home from both the hospital and SNF.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge all the members and participants in the Johns Hopkins Medicine Skilled Nursing Facility Collaborative and the executive sponsors and JHM hospital presidents for their support of this work.

Disclosures

Michele Bellantoni receives intramural salary support for being the medical director of the JHM SNF Collaborative. Damien Doyle is a part-time geriatrician at the Hebrew Home of Greater Washington, a skilled nursing facility. He received travel expense support for GAPNA, a local Advanced Practice Nurse Association meeting.The authors otherwise have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

The authors state that there were no external sponsors for this work.

Hospitals and health systems are under mounting financial pressure to shorten hospitalizations and reduce readmissions. These priorities have led to an ever-increasing focus on postacute care (PAC), and more specifically on improving transitions from the hospital.1,2 According to a 2013 Institute of Medicine report, PAC is the source of 73% of the variation in Medicare spending3 and readmissions during the postacute episode nearly double the average Medicare payment.4 Within the PAC landscape, discharges to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) have received particular focus due to the high rates of readmission and associated care costs.5

Hospitals, hospital physicians, PAC providers, and payers need to improve SNF transitions in care. Hospitals are increasingly responsible for patient care beyond their walls through several mechanisms including rehospitalization penalties, value-based reimbursement strategies (eg, bundled payments), and risk-based contracting on the total cost of care through relationships with accountable care organizations (ACOs) and Medicare Advantage plans. Similarly, hospital-employed physicians and PAC providers are more engaged in achieving value-based goals through increased alignment of provider compensation models6,7 with risk-based contracting.

Current evidence suggests that rehospitalizations could be reduced by focusing on a concentrated referral network of preferred high-quality SNFs;8,9 however, less is known about how to develop and operate such linkages at the administrative or clinical levels.8 In this article, we propose a collaborative framework for the establishment of a preferred PAC network.

SKILLED NURSING FACILITY PREFERRED PROVIDER NETWORK

One mechanism employed to improve transitions to SNFs and reduce associated readmissions is to create a preferred provider network. Increasing the concentration of hospital discharges to higher performing facilities is associated with lower rehospitalization rates, particularly during the critical days following discharge.10

While the criteria applied for preferred provider networks vary, there are several emerging themes.10 Quality metrics are often applied, generally starting with Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) quality star ratings and Long-Term Care Minimum Data Set (MDS) metrics with additional criteria frequently layered upon those. Some examples include the extent of physician coverage,11 the extent of nursing coverage (eg, nursing ratios or 24/7 nursing care), geographic access, and flexible admission times (including weekends and nights).12 In addition, several outcome measures may be used such as 30-day readmission rates, patient/family satisfaction ratings, ED visits, primary care follow-up within seven days of PAC discharge, or impact on the total cost of care.

Beyond the specified criteria, some hospitals choose to build upon existing relationships when developing their preferred network. By selecting historically high-volume facilities, they are able to leverage the existing name recognition amongst patients and providers.13 This minimizes retraining of discharge planners, maintains institutional relationships, and aligns with the patients’ geographic preferences.2,13 While the high volume SNFs may not have the highest quality ratings, some hospitals find they can leverage the value of preferred partner status to push behavior change and improve performance.13

PROPOSED HEALTH SYSTEM FRAMEWORK FOR CREATING A SKILLED NURSING FACILITY COLLABORATIVE

Here we propose a framework for the establishment of a preferred provider network for a hospital or health system based on the early experience of establishing an SNF Collaborative within Johns Hopkins Medicine (JHM). JHM is a large integrated health care system, which includes five hospitals within the region, including two large academic hospitals and three community hospitals serving patients in Maryland and the District of Columbia.14

JHM identified a need for improved coordination with PAC providers and saw opportunities to build upon successful individual hospital efforts to create a system-level approach with a PAC partnership sharing the goals of improving care and reducing costs. Additional opportunities exist given the unique Maryland all-payer Global Budget Revenue system managed by the Health Services Cost Review Commission. This system imposes hospital-level penalties for readmissions or poor quality measure performance and is moving to a new phase that will place hospitals directly at risk for the total Part A and Part B Medicare expenditures for a cohort of attributed Medicare patients, inclusive of their PAC expenses. This state-wide program is one example of a shift in payment structures from volume to value that is occurring throughout the healthcare sector.

Developing a formal collaboration inclusive of the five local hospitals, Johns Hopkins HealthCare (JHHC)—the managed care division of JHM—and the JHM ACO (Johns Hopkins Medicine Alliance for Patients, JMAP), we established a JHM SNF Collaborative. This group was tasked with improving the continuum of care for our patients discharged to PAC facilities. Given the number and diversity of entities involved, we sought to draw on efforts already managed and piloted locally, while disseminating best practices and providing added services at the collaborative level. We propose a collaborative multistakeholder model (Figure) that we anticipate will be adaptable to other health systems.

At the outset, we established a Steering Committee and a broad Stakeholder Group (Figure). The Steering Committee is comprised of representatives from all participating JHM entities and serves as the collaborative governing body. This group initially identified 36 local SNF partners including a mixture of larger corporate chains and freestanding entities. In an effort to respect patient choice and acknowledge geographic preferences and capacity limitations, partner selection was based on a combination of publically available quality metrics, historic referral volumes, and recommendations of each JHM hospital. While we sought to align with high-performing SNFs, we also saw an opportunity to leverage collaboration to drive improvement in lower-performing facilities that continue to receive a high volume of referrals. The Stakeholder Group includes a broader representation from JHM, including subject matter experts from related medical specialties (eg, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Internal Medicine, Emergency Medicine, and various surgical subspecialties); partner SNFs, and the local CMS-funded Quality Improvement Organization (QIO). Physician leadership was essential at all levels of the collaborative governing structure including the core Coordinating Team (Figure). Providers representing different hospitals were able to speak about variations in practice patterns and to assess the feasibility of suggested solutions on existing workflows.

After establishing the governance framework for the collaborative, it was determined that dedicated workgroups were needed to drive protocol-based initiatives, data, and analytics. For the former, we selected transitions of care as our initial focus area. All affiliated hospitals were working to address care transitions, but there were opportunities to develop a harmonized approach leveraging individual hospital input. The workgroup included representation from medical and administrative hospital leadership, JHHC, JMAP, our home care group, and SNF medical leadership. Initial priorities identified are reviewed in the Table. We anticipate new priorities for the collaborative over time and intend for the workgroup to evolve in line with shifting priorities.

We similarly established a multidisciplinary data and analytics workgroup to identify resources to develop the SNF, and a system-level dashboard to track our ongoing work. While incorporating data from five hospitals with varied patient populations, we felt that the risk-adjusted PAC data were critical to the collaborative establishment and goal setting. After exploring internal and external resources, we initially elected to engage an outside vendor offering risk-adjusted performance metrics. We have subsequently worked with the state health information exchange, CRISP,15 to develop a robust dashboard for Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries that could provide similar data.

IMPLEMENTATION

In the process of establishing the SNF Collaborative at JHM, there were a number of early challenges faced and lessons learned:

- In a large integrated delivery system, there is a need to balance the benefits of central coordination with the support for ongoing local efforts to promote partner engagement at the hospital and SNF level. The forums created within the collaborative governance structure can facilitate sharing of the prior health system, hospital or SNF initiatives to grow upon successes and avoid prior pitfalls.

- Early identification of risk-adjusted PAC data sources is central to the collaborative establishment and goal setting. This requires assessment of internal analytic resources, budget, and desired timeline for implementation to determine the optimal arrangement. Similarly, identification of available data sources to drive the analytic efforts is essential and should include a health information exchange, claims, and MDS among others.

- Partnering with local QIOs provides support for facility-level quality improvement efforts. They have the staff and onsite expertise to facilitate process implementation within individual SNFs.

- Larger preferred provider networks require considerable administrative support to facilitate communication with the entities, coordinate completion of network agreements, and manage the dissemination of SNF- and hospital-specific performance data.

- Legal and contractual support related to data sharing and HIPAA compliance is needed due to the complexity of the health system and SNF legal structure. Multiple JHM legal entities were involved in this collaborative as were a mixture of freestanding SNFs and corporate chains. There was a significant effort required to execute both data-sharing agreements as well as charters to enable QIO participation.

- Physician leadership and insight are key to implementing meaningful and broad change. When devising system-wide solutions, incorporation and respect for local processes and needs are paramount for provider engagement and behavior change. This process will likely identify gaps in understanding the PAC patient’s experience and needs. It may also reveal practice variability and foster opportunities for provider education on the needs of PAC teams and how to best facilitate quality transitions.

CONCLUSION

We proposed a framework for establishing a collaborative partnership with a preferred network of SNF providers. Depending on organizational readiness, significant upfront investment of time and resources could be needed to establish a coordinated network of SNF providers. However, once established, such networks can be leveraged to support ongoing process improvement efforts within a hospital or delivery system and can be used strategically by such health systems as they implement value-based health strategies. Furthermore, the lessons learned from transitions to SNFs can be applied more broadly in the PAC landscape including transitions to home from both the hospital and SNF.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge all the members and participants in the Johns Hopkins Medicine Skilled Nursing Facility Collaborative and the executive sponsors and JHM hospital presidents for their support of this work.

Disclosures

Michele Bellantoni receives intramural salary support for being the medical director of the JHM SNF Collaborative. Damien Doyle is a part-time geriatrician at the Hebrew Home of Greater Washington, a skilled nursing facility. He received travel expense support for GAPNA, a local Advanced Practice Nurse Association meeting.The authors otherwise have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

The authors state that there were no external sponsors for this work.

1. Burke RE, Whitfield EA, Hittle D, et al. Hospital readmission from post-acute care facilities: risk factors, timing, and outcomes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(3):249-255. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2015.11.005. PubMed

2. Mchugh JP, Zinn J, Shield RR, et al. Strategy and risk sharing in hospital–post-acute care integration. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018:1. doi:10.1097/hmr.0000000000000204. PubMed

3. Institute of Medicine. Variation in Health Care Spending Assessing Geographic Variation.; 2013. http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report Files/2013/Geographic-Variation2/geovariation_rb.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2018.

4. Dobson A, DaVanzo JE, Heath S, et al. Medicare Payment Bundling: Insights from Claims Data and Policy Implications Analyses of Episode-Based Payment. Washington, DC; 2012. http://www.aha.org/content/12/ahaaamcbundlingreport.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2018.

5. Mor V, Intrator O, Feng Z, Grabowski DC. The revolving door of rehospitalization from skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff. 2010;29(1):57-64. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0629. PubMed

6. Torchiana DF, Colton DG, Rao SK, Lenz SK, Meyer GS, Ferris TG. Massachusetts general physicians organization’s quality incentive program produces encouraging results. Health Aff. 2013;32(10):1748-1756. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0377. PubMed

7. Michtalik HJ, Carolan HT, Haut ER, et al. Use of provider-level dashboards and pay-for-performance in venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. J Hosp Med. 2014;10(3):172-178. doi:10.1002/jhm.2303. PubMed

8. Rahman M, Foster AD, Grabowski DC, Zinn JS, Mor V. Effect of hospital-SNF referral linkages on rehospitalization. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6pt1):1898-1919. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12112. PubMed

9. Huckfeldt PJ, Weissblum L, Escarce JJ, Karaca-Mandic P, Sood N. Do skilled nursing facilities selected to participate in preferred provider networks have higher quality and lower costs? Health Serv Res. 2018. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13027. PubMed

10. American Hospital Association. The role of post-acute care in new care delivery models. TrendWatch. http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/15dec-tw-postacute.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed December 19, 2017.

11. Lage DE, Rusinak D, Carr D, Grabowski DC, Ackerly DC. Creating a network of high-quality skilled nursing facilities: preliminary data on the postacute care quality improvement experiences of an accountable care organization. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(4):804-808. doi:10.1111/jgs.13351. PubMed

12. Ouslander JG, Bonner A, Herndon L, Shutes J. The Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers (INTERACT) quality improvement program: an overview for medical directors and primary care clinicians in long-term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(3):162-170. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2013.12.005. PubMed

13. McHugh JP, Foster A, Mor V, et al. Reducing hospital readmissions through preferred networks of skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff. 2017;36(9):1591-1598. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0211. PubMed

14. Fast Facts: Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/about/downloads/JHM-Fast-Facts.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2018.

15. CRISP – Chesapeake Regional Information System for our Patients. https://www.crisphealth.org/. Accessed October 17, 2018.

1. Burke RE, Whitfield EA, Hittle D, et al. Hospital readmission from post-acute care facilities: risk factors, timing, and outcomes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(3):249-255. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2015.11.005. PubMed

2. Mchugh JP, Zinn J, Shield RR, et al. Strategy and risk sharing in hospital–post-acute care integration. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018:1. doi:10.1097/hmr.0000000000000204. PubMed

3. Institute of Medicine. Variation in Health Care Spending Assessing Geographic Variation.; 2013. http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report Files/2013/Geographic-Variation2/geovariation_rb.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2018.

4. Dobson A, DaVanzo JE, Heath S, et al. Medicare Payment Bundling: Insights from Claims Data and Policy Implications Analyses of Episode-Based Payment. Washington, DC; 2012. http://www.aha.org/content/12/ahaaamcbundlingreport.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2018.

5. Mor V, Intrator O, Feng Z, Grabowski DC. The revolving door of rehospitalization from skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff. 2010;29(1):57-64. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0629. PubMed

6. Torchiana DF, Colton DG, Rao SK, Lenz SK, Meyer GS, Ferris TG. Massachusetts general physicians organization’s quality incentive program produces encouraging results. Health Aff. 2013;32(10):1748-1756. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0377. PubMed

7. Michtalik HJ, Carolan HT, Haut ER, et al. Use of provider-level dashboards and pay-for-performance in venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. J Hosp Med. 2014;10(3):172-178. doi:10.1002/jhm.2303. PubMed

8. Rahman M, Foster AD, Grabowski DC, Zinn JS, Mor V. Effect of hospital-SNF referral linkages on rehospitalization. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6pt1):1898-1919. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12112. PubMed

9. Huckfeldt PJ, Weissblum L, Escarce JJ, Karaca-Mandic P, Sood N. Do skilled nursing facilities selected to participate in preferred provider networks have higher quality and lower costs? Health Serv Res. 2018. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13027. PubMed

10. American Hospital Association. The role of post-acute care in new care delivery models. TrendWatch. http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/15dec-tw-postacute.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed December 19, 2017.

11. Lage DE, Rusinak D, Carr D, Grabowski DC, Ackerly DC. Creating a network of high-quality skilled nursing facilities: preliminary data on the postacute care quality improvement experiences of an accountable care organization. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(4):804-808. doi:10.1111/jgs.13351. PubMed

12. Ouslander JG, Bonner A, Herndon L, Shutes J. The Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers (INTERACT) quality improvement program: an overview for medical directors and primary care clinicians in long-term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(3):162-170. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2013.12.005. PubMed

13. McHugh JP, Foster A, Mor V, et al. Reducing hospital readmissions through preferred networks of skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff. 2017;36(9):1591-1598. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0211. PubMed

14. Fast Facts: Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/about/downloads/JHM-Fast-Facts.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2018.

15. CRISP – Chesapeake Regional Information System for our Patients. https://www.crisphealth.org/. Accessed October 17, 2018.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine