User login

Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value: Postacute Care Transitions: Developing a Skilled Nursing Facility Collaborative within an Academic Health System

Hospitals and health systems are under mounting financial pressure to shorten hospitalizations and reduce readmissions. These priorities have led to an ever-increasing focus on postacute care (PAC), and more specifically on improving transitions from the hospital.1,2 According to a 2013 Institute of Medicine report, PAC is the source of 73% of the variation in Medicare spending3 and readmissions during the postacute episode nearly double the average Medicare payment.4 Within the PAC landscape, discharges to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) have received particular focus due to the high rates of readmission and associated care costs.5

Hospitals, hospital physicians, PAC providers, and payers need to improve SNF transitions in care. Hospitals are increasingly responsible for patient care beyond their walls through several mechanisms including rehospitalization penalties, value-based reimbursement strategies (eg, bundled payments), and risk-based contracting on the total cost of care through relationships with accountable care organizations (ACOs) and Medicare Advantage plans. Similarly, hospital-employed physicians and PAC providers are more engaged in achieving value-based goals through increased alignment of provider compensation models6,7 with risk-based contracting.

Current evidence suggests that rehospitalizations could be reduced by focusing on a concentrated referral network of preferred high-quality SNFs;8,9 however, less is known about how to develop and operate such linkages at the administrative or clinical levels.8 In this article, we propose a collaborative framework for the establishment of a preferred PAC network.

SKILLED NURSING FACILITY PREFERRED PROVIDER NETWORK

One mechanism employed to improve transitions to SNFs and reduce associated readmissions is to create a preferred provider network. Increasing the concentration of hospital discharges to higher performing facilities is associated with lower rehospitalization rates, particularly during the critical days following discharge.10

While the criteria applied for preferred provider networks vary, there are several emerging themes.10 Quality metrics are often applied, generally starting with Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) quality star ratings and Long-Term Care Minimum Data Set (MDS) metrics with additional criteria frequently layered upon those. Some examples include the extent of physician coverage,11 the extent of nursing coverage (eg, nursing ratios or 24/7 nursing care), geographic access, and flexible admission times (including weekends and nights).12 In addition, several outcome measures may be used such as 30-day readmission rates, patient/family satisfaction ratings, ED visits, primary care follow-up within seven days of PAC discharge, or impact on the total cost of care.

Beyond the specified criteria, some hospitals choose to build upon existing relationships when developing their preferred network. By selecting historically high-volume facilities, they are able to leverage the existing name recognition amongst patients and providers.13 This minimizes retraining of discharge planners, maintains institutional relationships, and aligns with the patients’ geographic preferences.2,13 While the high volume SNFs may not have the highest quality ratings, some hospitals find they can leverage the value of preferred partner status to push behavior change and improve performance.13

PROPOSED HEALTH SYSTEM FRAMEWORK FOR CREATING A SKILLED NURSING FACILITY COLLABORATIVE

Here we propose a framework for the establishment of a preferred provider network for a hospital or health system based on the early experience of establishing an SNF Collaborative within Johns Hopkins Medicine (JHM). JHM is a large integrated health care system, which includes five hospitals within the region, including two large academic hospitals and three community hospitals serving patients in Maryland and the District of Columbia.14

JHM identified a need for improved coordination with PAC providers and saw opportunities to build upon successful individual hospital efforts to create a system-level approach with a PAC partnership sharing the goals of improving care and reducing costs. Additional opportunities exist given the unique Maryland all-payer Global Budget Revenue system managed by the Health Services Cost Review Commission. This system imposes hospital-level penalties for readmissions or poor quality measure performance and is moving to a new phase that will place hospitals directly at risk for the total Part A and Part B Medicare expenditures for a cohort of attributed Medicare patients, inclusive of their PAC expenses. This state-wide program is one example of a shift in payment structures from volume to value that is occurring throughout the healthcare sector.

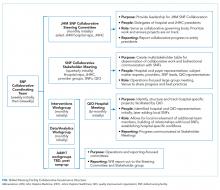

Developing a formal collaboration inclusive of the five local hospitals, Johns Hopkins HealthCare (JHHC)—the managed care division of JHM—and the JHM ACO (Johns Hopkins Medicine Alliance for Patients, JMAP), we established a JHM SNF Collaborative. This group was tasked with improving the continuum of care for our patients discharged to PAC facilities. Given the number and diversity of entities involved, we sought to draw on efforts already managed and piloted locally, while disseminating best practices and providing added services at the collaborative level. We propose a collaborative multistakeholder model (Figure) that we anticipate will be adaptable to other health systems.

At the outset, we established a Steering Committee and a broad Stakeholder Group (Figure). The Steering Committee is comprised of representatives from all participating JHM entities and serves as the collaborative governing body. This group initially identified 36 local SNF partners including a mixture of larger corporate chains and freestanding entities. In an effort to respect patient choice and acknowledge geographic preferences and capacity limitations, partner selection was based on a combination of publically available quality metrics, historic referral volumes, and recommendations of each JHM hospital. While we sought to align with high-performing SNFs, we also saw an opportunity to leverage collaboration to drive improvement in lower-performing facilities that continue to receive a high volume of referrals. The Stakeholder Group includes a broader representation from JHM, including subject matter experts from related medical specialties (eg, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Internal Medicine, Emergency Medicine, and various surgical subspecialties); partner SNFs, and the local CMS-funded Quality Improvement Organization (QIO). Physician leadership was essential at all levels of the collaborative governing structure including the core Coordinating Team (Figure). Providers representing different hospitals were able to speak about variations in practice patterns and to assess the feasibility of suggested solutions on existing workflows.

After establishing the governance framework for the collaborative, it was determined that dedicated workgroups were needed to drive protocol-based initiatives, data, and analytics. For the former, we selected transitions of care as our initial focus area. All affiliated hospitals were working to address care transitions, but there were opportunities to develop a harmonized approach leveraging individual hospital input. The workgroup included representation from medical and administrative hospital leadership, JHHC, JMAP, our home care group, and SNF medical leadership. Initial priorities identified are reviewed in the Table. We anticipate new priorities for the collaborative over time and intend for the workgroup to evolve in line with shifting priorities.

We similarly established a multidisciplinary data and analytics workgroup to identify resources to develop the SNF, and a system-level dashboard to track our ongoing work. While incorporating data from five hospitals with varied patient populations, we felt that the risk-adjusted PAC data were critical to the collaborative establishment and goal setting. After exploring internal and external resources, we initially elected to engage an outside vendor offering risk-adjusted performance metrics. We have subsequently worked with the state health information exchange, CRISP,15 to develop a robust dashboard for Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries that could provide similar data.

IMPLEMENTATION

In the process of establishing the SNF Collaborative at JHM, there were a number of early challenges faced and lessons learned:

- In a large integrated delivery system, there is a need to balance the benefits of central coordination with the support for ongoing local efforts to promote partner engagement at the hospital and SNF level. The forums created within the collaborative governance structure can facilitate sharing of the prior health system, hospital or SNF initiatives to grow upon successes and avoid prior pitfalls.

- Early identification of risk-adjusted PAC data sources is central to the collaborative establishment and goal setting. This requires assessment of internal analytic resources, budget, and desired timeline for implementation to determine the optimal arrangement. Similarly, identification of available data sources to drive the analytic efforts is essential and should include a health information exchange, claims, and MDS among others.

- Partnering with local QIOs provides support for facility-level quality improvement efforts. They have the staff and onsite expertise to facilitate process implementation within individual SNFs.

- Larger preferred provider networks require considerable administrative support to facilitate communication with the entities, coordinate completion of network agreements, and manage the dissemination of SNF- and hospital-specific performance data.

- Legal and contractual support related to data sharing and HIPAA compliance is needed due to the complexity of the health system and SNF legal structure. Multiple JHM legal entities were involved in this collaborative as were a mixture of freestanding SNFs and corporate chains. There was a significant effort required to execute both data-sharing agreements as well as charters to enable QIO participation.

- Physician leadership and insight are key to implementing meaningful and broad change. When devising system-wide solutions, incorporation and respect for local processes and needs are paramount for provider engagement and behavior change. This process will likely identify gaps in understanding the PAC patient’s experience and needs. It may also reveal practice variability and foster opportunities for provider education on the needs of PAC teams and how to best facilitate quality transitions.

CONCLUSION

We proposed a framework for establishing a collaborative partnership with a preferred network of SNF providers. Depending on organizational readiness, significant upfront investment of time and resources could be needed to establish a coordinated network of SNF providers. However, once established, such networks can be leveraged to support ongoing process improvement efforts within a hospital or delivery system and can be used strategically by such health systems as they implement value-based health strategies. Furthermore, the lessons learned from transitions to SNFs can be applied more broadly in the PAC landscape including transitions to home from both the hospital and SNF.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge all the members and participants in the Johns Hopkins Medicine Skilled Nursing Facility Collaborative and the executive sponsors and JHM hospital presidents for their support of this work.

Disclosures

Michele Bellantoni receives intramural salary support for being the medical director of the JHM SNF Collaborative. Damien Doyle is a part-time geriatrician at the Hebrew Home of Greater Washington, a skilled nursing facility. He received travel expense support for GAPNA, a local Advanced Practice Nurse Association meeting.The authors otherwise have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

The authors state that there were no external sponsors for this work.

1. Burke RE, Whitfield EA, Hittle D, et al. Hospital readmission from post-acute care facilities: risk factors, timing, and outcomes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(3):249-255. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2015.11.005. PubMed

2. Mchugh JP, Zinn J, Shield RR, et al. Strategy and risk sharing in hospital–post-acute care integration. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018:1. doi:10.1097/hmr.0000000000000204. PubMed

3. Institute of Medicine. Variation in Health Care Spending Assessing Geographic Variation.; 2013. http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report Files/2013/Geographic-Variation2/geovariation_rb.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2018.

4. Dobson A, DaVanzo JE, Heath S, et al. Medicare Payment Bundling: Insights from Claims Data and Policy Implications Analyses of Episode-Based Payment. Washington, DC; 2012. http://www.aha.org/content/12/ahaaamcbundlingreport.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2018.

5. Mor V, Intrator O, Feng Z, Grabowski DC. The revolving door of rehospitalization from skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff. 2010;29(1):57-64. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0629. PubMed

6. Torchiana DF, Colton DG, Rao SK, Lenz SK, Meyer GS, Ferris TG. Massachusetts general physicians organization’s quality incentive program produces encouraging results. Health Aff. 2013;32(10):1748-1756. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0377. PubMed

7. Michtalik HJ, Carolan HT, Haut ER, et al. Use of provider-level dashboards and pay-for-performance in venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. J Hosp Med. 2014;10(3):172-178. doi:10.1002/jhm.2303. PubMed

8. Rahman M, Foster AD, Grabowski DC, Zinn JS, Mor V. Effect of hospital-SNF referral linkages on rehospitalization. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6pt1):1898-1919. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12112. PubMed

9. Huckfeldt PJ, Weissblum L, Escarce JJ, Karaca-Mandic P, Sood N. Do skilled nursing facilities selected to participate in preferred provider networks have higher quality and lower costs? Health Serv Res. 2018. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13027. PubMed

10. American Hospital Association. The role of post-acute care in new care delivery models. TrendWatch. http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/15dec-tw-postacute.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed December 19, 2017.

11. Lage DE, Rusinak D, Carr D, Grabowski DC, Ackerly DC. Creating a network of high-quality skilled nursing facilities: preliminary data on the postacute care quality improvement experiences of an accountable care organization. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(4):804-808. doi:10.1111/jgs.13351. PubMed

12. Ouslander JG, Bonner A, Herndon L, Shutes J. The Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers (INTERACT) quality improvement program: an overview for medical directors and primary care clinicians in long-term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(3):162-170. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2013.12.005. PubMed

13. McHugh JP, Foster A, Mor V, et al. Reducing hospital readmissions through preferred networks of skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff. 2017;36(9):1591-1598. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0211. PubMed

14. Fast Facts: Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/about/downloads/JHM-Fast-Facts.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2018.

15. CRISP – Chesapeake Regional Information System for our Patients. https://www.crisphealth.org/. Accessed October 17, 2018.

Hospitals and health systems are under mounting financial pressure to shorten hospitalizations and reduce readmissions. These priorities have led to an ever-increasing focus on postacute care (PAC), and more specifically on improving transitions from the hospital.1,2 According to a 2013 Institute of Medicine report, PAC is the source of 73% of the variation in Medicare spending3 and readmissions during the postacute episode nearly double the average Medicare payment.4 Within the PAC landscape, discharges to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) have received particular focus due to the high rates of readmission and associated care costs.5

Hospitals, hospital physicians, PAC providers, and payers need to improve SNF transitions in care. Hospitals are increasingly responsible for patient care beyond their walls through several mechanisms including rehospitalization penalties, value-based reimbursement strategies (eg, bundled payments), and risk-based contracting on the total cost of care through relationships with accountable care organizations (ACOs) and Medicare Advantage plans. Similarly, hospital-employed physicians and PAC providers are more engaged in achieving value-based goals through increased alignment of provider compensation models6,7 with risk-based contracting.

Current evidence suggests that rehospitalizations could be reduced by focusing on a concentrated referral network of preferred high-quality SNFs;8,9 however, less is known about how to develop and operate such linkages at the administrative or clinical levels.8 In this article, we propose a collaborative framework for the establishment of a preferred PAC network.

SKILLED NURSING FACILITY PREFERRED PROVIDER NETWORK

One mechanism employed to improve transitions to SNFs and reduce associated readmissions is to create a preferred provider network. Increasing the concentration of hospital discharges to higher performing facilities is associated with lower rehospitalization rates, particularly during the critical days following discharge.10

While the criteria applied for preferred provider networks vary, there are several emerging themes.10 Quality metrics are often applied, generally starting with Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) quality star ratings and Long-Term Care Minimum Data Set (MDS) metrics with additional criteria frequently layered upon those. Some examples include the extent of physician coverage,11 the extent of nursing coverage (eg, nursing ratios or 24/7 nursing care), geographic access, and flexible admission times (including weekends and nights).12 In addition, several outcome measures may be used such as 30-day readmission rates, patient/family satisfaction ratings, ED visits, primary care follow-up within seven days of PAC discharge, or impact on the total cost of care.

Beyond the specified criteria, some hospitals choose to build upon existing relationships when developing their preferred network. By selecting historically high-volume facilities, they are able to leverage the existing name recognition amongst patients and providers.13 This minimizes retraining of discharge planners, maintains institutional relationships, and aligns with the patients’ geographic preferences.2,13 While the high volume SNFs may not have the highest quality ratings, some hospitals find they can leverage the value of preferred partner status to push behavior change and improve performance.13

PROPOSED HEALTH SYSTEM FRAMEWORK FOR CREATING A SKILLED NURSING FACILITY COLLABORATIVE

Here we propose a framework for the establishment of a preferred provider network for a hospital or health system based on the early experience of establishing an SNF Collaborative within Johns Hopkins Medicine (JHM). JHM is a large integrated health care system, which includes five hospitals within the region, including two large academic hospitals and three community hospitals serving patients in Maryland and the District of Columbia.14

JHM identified a need for improved coordination with PAC providers and saw opportunities to build upon successful individual hospital efforts to create a system-level approach with a PAC partnership sharing the goals of improving care and reducing costs. Additional opportunities exist given the unique Maryland all-payer Global Budget Revenue system managed by the Health Services Cost Review Commission. This system imposes hospital-level penalties for readmissions or poor quality measure performance and is moving to a new phase that will place hospitals directly at risk for the total Part A and Part B Medicare expenditures for a cohort of attributed Medicare patients, inclusive of their PAC expenses. This state-wide program is one example of a shift in payment structures from volume to value that is occurring throughout the healthcare sector.

Developing a formal collaboration inclusive of the five local hospitals, Johns Hopkins HealthCare (JHHC)—the managed care division of JHM—and the JHM ACO (Johns Hopkins Medicine Alliance for Patients, JMAP), we established a JHM SNF Collaborative. This group was tasked with improving the continuum of care for our patients discharged to PAC facilities. Given the number and diversity of entities involved, we sought to draw on efforts already managed and piloted locally, while disseminating best practices and providing added services at the collaborative level. We propose a collaborative multistakeholder model (Figure) that we anticipate will be adaptable to other health systems.

At the outset, we established a Steering Committee and a broad Stakeholder Group (Figure). The Steering Committee is comprised of representatives from all participating JHM entities and serves as the collaborative governing body. This group initially identified 36 local SNF partners including a mixture of larger corporate chains and freestanding entities. In an effort to respect patient choice and acknowledge geographic preferences and capacity limitations, partner selection was based on a combination of publically available quality metrics, historic referral volumes, and recommendations of each JHM hospital. While we sought to align with high-performing SNFs, we also saw an opportunity to leverage collaboration to drive improvement in lower-performing facilities that continue to receive a high volume of referrals. The Stakeholder Group includes a broader representation from JHM, including subject matter experts from related medical specialties (eg, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Internal Medicine, Emergency Medicine, and various surgical subspecialties); partner SNFs, and the local CMS-funded Quality Improvement Organization (QIO). Physician leadership was essential at all levels of the collaborative governing structure including the core Coordinating Team (Figure). Providers representing different hospitals were able to speak about variations in practice patterns and to assess the feasibility of suggested solutions on existing workflows.

After establishing the governance framework for the collaborative, it was determined that dedicated workgroups were needed to drive protocol-based initiatives, data, and analytics. For the former, we selected transitions of care as our initial focus area. All affiliated hospitals were working to address care transitions, but there were opportunities to develop a harmonized approach leveraging individual hospital input. The workgroup included representation from medical and administrative hospital leadership, JHHC, JMAP, our home care group, and SNF medical leadership. Initial priorities identified are reviewed in the Table. We anticipate new priorities for the collaborative over time and intend for the workgroup to evolve in line with shifting priorities.

We similarly established a multidisciplinary data and analytics workgroup to identify resources to develop the SNF, and a system-level dashboard to track our ongoing work. While incorporating data from five hospitals with varied patient populations, we felt that the risk-adjusted PAC data were critical to the collaborative establishment and goal setting. After exploring internal and external resources, we initially elected to engage an outside vendor offering risk-adjusted performance metrics. We have subsequently worked with the state health information exchange, CRISP,15 to develop a robust dashboard for Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries that could provide similar data.

IMPLEMENTATION

In the process of establishing the SNF Collaborative at JHM, there were a number of early challenges faced and lessons learned:

- In a large integrated delivery system, there is a need to balance the benefits of central coordination with the support for ongoing local efforts to promote partner engagement at the hospital and SNF level. The forums created within the collaborative governance structure can facilitate sharing of the prior health system, hospital or SNF initiatives to grow upon successes and avoid prior pitfalls.

- Early identification of risk-adjusted PAC data sources is central to the collaborative establishment and goal setting. This requires assessment of internal analytic resources, budget, and desired timeline for implementation to determine the optimal arrangement. Similarly, identification of available data sources to drive the analytic efforts is essential and should include a health information exchange, claims, and MDS among others.

- Partnering with local QIOs provides support for facility-level quality improvement efforts. They have the staff and onsite expertise to facilitate process implementation within individual SNFs.

- Larger preferred provider networks require considerable administrative support to facilitate communication with the entities, coordinate completion of network agreements, and manage the dissemination of SNF- and hospital-specific performance data.

- Legal and contractual support related to data sharing and HIPAA compliance is needed due to the complexity of the health system and SNF legal structure. Multiple JHM legal entities were involved in this collaborative as were a mixture of freestanding SNFs and corporate chains. There was a significant effort required to execute both data-sharing agreements as well as charters to enable QIO participation.

- Physician leadership and insight are key to implementing meaningful and broad change. When devising system-wide solutions, incorporation and respect for local processes and needs are paramount for provider engagement and behavior change. This process will likely identify gaps in understanding the PAC patient’s experience and needs. It may also reveal practice variability and foster opportunities for provider education on the needs of PAC teams and how to best facilitate quality transitions.

CONCLUSION

We proposed a framework for establishing a collaborative partnership with a preferred network of SNF providers. Depending on organizational readiness, significant upfront investment of time and resources could be needed to establish a coordinated network of SNF providers. However, once established, such networks can be leveraged to support ongoing process improvement efforts within a hospital or delivery system and can be used strategically by such health systems as they implement value-based health strategies. Furthermore, the lessons learned from transitions to SNFs can be applied more broadly in the PAC landscape including transitions to home from both the hospital and SNF.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge all the members and participants in the Johns Hopkins Medicine Skilled Nursing Facility Collaborative and the executive sponsors and JHM hospital presidents for their support of this work.

Disclosures

Michele Bellantoni receives intramural salary support for being the medical director of the JHM SNF Collaborative. Damien Doyle is a part-time geriatrician at the Hebrew Home of Greater Washington, a skilled nursing facility. He received travel expense support for GAPNA, a local Advanced Practice Nurse Association meeting.The authors otherwise have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

The authors state that there were no external sponsors for this work.

Hospitals and health systems are under mounting financial pressure to shorten hospitalizations and reduce readmissions. These priorities have led to an ever-increasing focus on postacute care (PAC), and more specifically on improving transitions from the hospital.1,2 According to a 2013 Institute of Medicine report, PAC is the source of 73% of the variation in Medicare spending3 and readmissions during the postacute episode nearly double the average Medicare payment.4 Within the PAC landscape, discharges to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) have received particular focus due to the high rates of readmission and associated care costs.5

Hospitals, hospital physicians, PAC providers, and payers need to improve SNF transitions in care. Hospitals are increasingly responsible for patient care beyond their walls through several mechanisms including rehospitalization penalties, value-based reimbursement strategies (eg, bundled payments), and risk-based contracting on the total cost of care through relationships with accountable care organizations (ACOs) and Medicare Advantage plans. Similarly, hospital-employed physicians and PAC providers are more engaged in achieving value-based goals through increased alignment of provider compensation models6,7 with risk-based contracting.

Current evidence suggests that rehospitalizations could be reduced by focusing on a concentrated referral network of preferred high-quality SNFs;8,9 however, less is known about how to develop and operate such linkages at the administrative or clinical levels.8 In this article, we propose a collaborative framework for the establishment of a preferred PAC network.

SKILLED NURSING FACILITY PREFERRED PROVIDER NETWORK

One mechanism employed to improve transitions to SNFs and reduce associated readmissions is to create a preferred provider network. Increasing the concentration of hospital discharges to higher performing facilities is associated with lower rehospitalization rates, particularly during the critical days following discharge.10

While the criteria applied for preferred provider networks vary, there are several emerging themes.10 Quality metrics are often applied, generally starting with Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) quality star ratings and Long-Term Care Minimum Data Set (MDS) metrics with additional criteria frequently layered upon those. Some examples include the extent of physician coverage,11 the extent of nursing coverage (eg, nursing ratios or 24/7 nursing care), geographic access, and flexible admission times (including weekends and nights).12 In addition, several outcome measures may be used such as 30-day readmission rates, patient/family satisfaction ratings, ED visits, primary care follow-up within seven days of PAC discharge, or impact on the total cost of care.

Beyond the specified criteria, some hospitals choose to build upon existing relationships when developing their preferred network. By selecting historically high-volume facilities, they are able to leverage the existing name recognition amongst patients and providers.13 This minimizes retraining of discharge planners, maintains institutional relationships, and aligns with the patients’ geographic preferences.2,13 While the high volume SNFs may not have the highest quality ratings, some hospitals find they can leverage the value of preferred partner status to push behavior change and improve performance.13

PROPOSED HEALTH SYSTEM FRAMEWORK FOR CREATING A SKILLED NURSING FACILITY COLLABORATIVE

Here we propose a framework for the establishment of a preferred provider network for a hospital or health system based on the early experience of establishing an SNF Collaborative within Johns Hopkins Medicine (JHM). JHM is a large integrated health care system, which includes five hospitals within the region, including two large academic hospitals and three community hospitals serving patients in Maryland and the District of Columbia.14

JHM identified a need for improved coordination with PAC providers and saw opportunities to build upon successful individual hospital efforts to create a system-level approach with a PAC partnership sharing the goals of improving care and reducing costs. Additional opportunities exist given the unique Maryland all-payer Global Budget Revenue system managed by the Health Services Cost Review Commission. This system imposes hospital-level penalties for readmissions or poor quality measure performance and is moving to a new phase that will place hospitals directly at risk for the total Part A and Part B Medicare expenditures for a cohort of attributed Medicare patients, inclusive of their PAC expenses. This state-wide program is one example of a shift in payment structures from volume to value that is occurring throughout the healthcare sector.

Developing a formal collaboration inclusive of the five local hospitals, Johns Hopkins HealthCare (JHHC)—the managed care division of JHM—and the JHM ACO (Johns Hopkins Medicine Alliance for Patients, JMAP), we established a JHM SNF Collaborative. This group was tasked with improving the continuum of care for our patients discharged to PAC facilities. Given the number and diversity of entities involved, we sought to draw on efforts already managed and piloted locally, while disseminating best practices and providing added services at the collaborative level. We propose a collaborative multistakeholder model (Figure) that we anticipate will be adaptable to other health systems.

At the outset, we established a Steering Committee and a broad Stakeholder Group (Figure). The Steering Committee is comprised of representatives from all participating JHM entities and serves as the collaborative governing body. This group initially identified 36 local SNF partners including a mixture of larger corporate chains and freestanding entities. In an effort to respect patient choice and acknowledge geographic preferences and capacity limitations, partner selection was based on a combination of publically available quality metrics, historic referral volumes, and recommendations of each JHM hospital. While we sought to align with high-performing SNFs, we also saw an opportunity to leverage collaboration to drive improvement in lower-performing facilities that continue to receive a high volume of referrals. The Stakeholder Group includes a broader representation from JHM, including subject matter experts from related medical specialties (eg, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Internal Medicine, Emergency Medicine, and various surgical subspecialties); partner SNFs, and the local CMS-funded Quality Improvement Organization (QIO). Physician leadership was essential at all levels of the collaborative governing structure including the core Coordinating Team (Figure). Providers representing different hospitals were able to speak about variations in practice patterns and to assess the feasibility of suggested solutions on existing workflows.

After establishing the governance framework for the collaborative, it was determined that dedicated workgroups were needed to drive protocol-based initiatives, data, and analytics. For the former, we selected transitions of care as our initial focus area. All affiliated hospitals were working to address care transitions, but there were opportunities to develop a harmonized approach leveraging individual hospital input. The workgroup included representation from medical and administrative hospital leadership, JHHC, JMAP, our home care group, and SNF medical leadership. Initial priorities identified are reviewed in the Table. We anticipate new priorities for the collaborative over time and intend for the workgroup to evolve in line with shifting priorities.

We similarly established a multidisciplinary data and analytics workgroup to identify resources to develop the SNF, and a system-level dashboard to track our ongoing work. While incorporating data from five hospitals with varied patient populations, we felt that the risk-adjusted PAC data were critical to the collaborative establishment and goal setting. After exploring internal and external resources, we initially elected to engage an outside vendor offering risk-adjusted performance metrics. We have subsequently worked with the state health information exchange, CRISP,15 to develop a robust dashboard for Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries that could provide similar data.

IMPLEMENTATION

In the process of establishing the SNF Collaborative at JHM, there were a number of early challenges faced and lessons learned:

- In a large integrated delivery system, there is a need to balance the benefits of central coordination with the support for ongoing local efforts to promote partner engagement at the hospital and SNF level. The forums created within the collaborative governance structure can facilitate sharing of the prior health system, hospital or SNF initiatives to grow upon successes and avoid prior pitfalls.

- Early identification of risk-adjusted PAC data sources is central to the collaborative establishment and goal setting. This requires assessment of internal analytic resources, budget, and desired timeline for implementation to determine the optimal arrangement. Similarly, identification of available data sources to drive the analytic efforts is essential and should include a health information exchange, claims, and MDS among others.

- Partnering with local QIOs provides support for facility-level quality improvement efforts. They have the staff and onsite expertise to facilitate process implementation within individual SNFs.

- Larger preferred provider networks require considerable administrative support to facilitate communication with the entities, coordinate completion of network agreements, and manage the dissemination of SNF- and hospital-specific performance data.

- Legal and contractual support related to data sharing and HIPAA compliance is needed due to the complexity of the health system and SNF legal structure. Multiple JHM legal entities were involved in this collaborative as were a mixture of freestanding SNFs and corporate chains. There was a significant effort required to execute both data-sharing agreements as well as charters to enable QIO participation.

- Physician leadership and insight are key to implementing meaningful and broad change. When devising system-wide solutions, incorporation and respect for local processes and needs are paramount for provider engagement and behavior change. This process will likely identify gaps in understanding the PAC patient’s experience and needs. It may also reveal practice variability and foster opportunities for provider education on the needs of PAC teams and how to best facilitate quality transitions.

CONCLUSION

We proposed a framework for establishing a collaborative partnership with a preferred network of SNF providers. Depending on organizational readiness, significant upfront investment of time and resources could be needed to establish a coordinated network of SNF providers. However, once established, such networks can be leveraged to support ongoing process improvement efforts within a hospital or delivery system and can be used strategically by such health systems as they implement value-based health strategies. Furthermore, the lessons learned from transitions to SNFs can be applied more broadly in the PAC landscape including transitions to home from both the hospital and SNF.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge all the members and participants in the Johns Hopkins Medicine Skilled Nursing Facility Collaborative and the executive sponsors and JHM hospital presidents for their support of this work.

Disclosures

Michele Bellantoni receives intramural salary support for being the medical director of the JHM SNF Collaborative. Damien Doyle is a part-time geriatrician at the Hebrew Home of Greater Washington, a skilled nursing facility. He received travel expense support for GAPNA, a local Advanced Practice Nurse Association meeting.The authors otherwise have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

The authors state that there were no external sponsors for this work.

1. Burke RE, Whitfield EA, Hittle D, et al. Hospital readmission from post-acute care facilities: risk factors, timing, and outcomes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(3):249-255. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2015.11.005. PubMed

2. Mchugh JP, Zinn J, Shield RR, et al. Strategy and risk sharing in hospital–post-acute care integration. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018:1. doi:10.1097/hmr.0000000000000204. PubMed

3. Institute of Medicine. Variation in Health Care Spending Assessing Geographic Variation.; 2013. http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report Files/2013/Geographic-Variation2/geovariation_rb.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2018.

4. Dobson A, DaVanzo JE, Heath S, et al. Medicare Payment Bundling: Insights from Claims Data and Policy Implications Analyses of Episode-Based Payment. Washington, DC; 2012. http://www.aha.org/content/12/ahaaamcbundlingreport.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2018.

5. Mor V, Intrator O, Feng Z, Grabowski DC. The revolving door of rehospitalization from skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff. 2010;29(1):57-64. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0629. PubMed

6. Torchiana DF, Colton DG, Rao SK, Lenz SK, Meyer GS, Ferris TG. Massachusetts general physicians organization’s quality incentive program produces encouraging results. Health Aff. 2013;32(10):1748-1756. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0377. PubMed

7. Michtalik HJ, Carolan HT, Haut ER, et al. Use of provider-level dashboards and pay-for-performance in venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. J Hosp Med. 2014;10(3):172-178. doi:10.1002/jhm.2303. PubMed

8. Rahman M, Foster AD, Grabowski DC, Zinn JS, Mor V. Effect of hospital-SNF referral linkages on rehospitalization. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6pt1):1898-1919. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12112. PubMed

9. Huckfeldt PJ, Weissblum L, Escarce JJ, Karaca-Mandic P, Sood N. Do skilled nursing facilities selected to participate in preferred provider networks have higher quality and lower costs? Health Serv Res. 2018. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13027. PubMed

10. American Hospital Association. The role of post-acute care in new care delivery models. TrendWatch. http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/15dec-tw-postacute.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed December 19, 2017.

11. Lage DE, Rusinak D, Carr D, Grabowski DC, Ackerly DC. Creating a network of high-quality skilled nursing facilities: preliminary data on the postacute care quality improvement experiences of an accountable care organization. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(4):804-808. doi:10.1111/jgs.13351. PubMed

12. Ouslander JG, Bonner A, Herndon L, Shutes J. The Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers (INTERACT) quality improvement program: an overview for medical directors and primary care clinicians in long-term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(3):162-170. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2013.12.005. PubMed

13. McHugh JP, Foster A, Mor V, et al. Reducing hospital readmissions through preferred networks of skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff. 2017;36(9):1591-1598. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0211. PubMed

14. Fast Facts: Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/about/downloads/JHM-Fast-Facts.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2018.

15. CRISP – Chesapeake Regional Information System for our Patients. https://www.crisphealth.org/. Accessed October 17, 2018.

1. Burke RE, Whitfield EA, Hittle D, et al. Hospital readmission from post-acute care facilities: risk factors, timing, and outcomes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(3):249-255. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2015.11.005. PubMed

2. Mchugh JP, Zinn J, Shield RR, et al. Strategy and risk sharing in hospital–post-acute care integration. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018:1. doi:10.1097/hmr.0000000000000204. PubMed

3. Institute of Medicine. Variation in Health Care Spending Assessing Geographic Variation.; 2013. http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report Files/2013/Geographic-Variation2/geovariation_rb.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2018.

4. Dobson A, DaVanzo JE, Heath S, et al. Medicare Payment Bundling: Insights from Claims Data and Policy Implications Analyses of Episode-Based Payment. Washington, DC; 2012. http://www.aha.org/content/12/ahaaamcbundlingreport.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2018.

5. Mor V, Intrator O, Feng Z, Grabowski DC. The revolving door of rehospitalization from skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff. 2010;29(1):57-64. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0629. PubMed

6. Torchiana DF, Colton DG, Rao SK, Lenz SK, Meyer GS, Ferris TG. Massachusetts general physicians organization’s quality incentive program produces encouraging results. Health Aff. 2013;32(10):1748-1756. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0377. PubMed

7. Michtalik HJ, Carolan HT, Haut ER, et al. Use of provider-level dashboards and pay-for-performance in venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. J Hosp Med. 2014;10(3):172-178. doi:10.1002/jhm.2303. PubMed

8. Rahman M, Foster AD, Grabowski DC, Zinn JS, Mor V. Effect of hospital-SNF referral linkages on rehospitalization. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6pt1):1898-1919. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12112. PubMed

9. Huckfeldt PJ, Weissblum L, Escarce JJ, Karaca-Mandic P, Sood N. Do skilled nursing facilities selected to participate in preferred provider networks have higher quality and lower costs? Health Serv Res. 2018. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13027. PubMed

10. American Hospital Association. The role of post-acute care in new care delivery models. TrendWatch. http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/15dec-tw-postacute.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed December 19, 2017.

11. Lage DE, Rusinak D, Carr D, Grabowski DC, Ackerly DC. Creating a network of high-quality skilled nursing facilities: preliminary data on the postacute care quality improvement experiences of an accountable care organization. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(4):804-808. doi:10.1111/jgs.13351. PubMed

12. Ouslander JG, Bonner A, Herndon L, Shutes J. The Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers (INTERACT) quality improvement program: an overview for medical directors and primary care clinicians in long-term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(3):162-170. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2013.12.005. PubMed

13. McHugh JP, Foster A, Mor V, et al. Reducing hospital readmissions through preferred networks of skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff. 2017;36(9):1591-1598. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0211. PubMed

14. Fast Facts: Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/about/downloads/JHM-Fast-Facts.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2018.

15. CRISP – Chesapeake Regional Information System for our Patients. https://www.crisphealth.org/. Accessed October 17, 2018.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

A Concise Tool for Measuring Care Coordination from the Provider’s Perspective in the Hospital Setting

Care Coordination has been defined as “…the deliberate organization of patient care activities between two or more participants (including the patient) involved in a patient’s care to facilitate the appropriate delivery of healthcare services.”1 The Institute of Medicine identified care coordination as a key strategy to improve the American healthcare system,2 and evidence has been building that well-coordinated care improves patient outcomes and reduces healthcare costs associated with chronic conditions.3-5 In 2012, Johns Hopkins Medicine was awarded a Healthcare Innovation Award by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to improve coordination of care across the continuum of care for adult patients admitted to Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) and Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center (JHBMC), and for high-risk low-income Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries receiving ambulatory care in targeted zip codes. The purpose of this project, known as the Johns Hopkins Community Health Partnership (J-CHiP), was to improve health and healthcare and to reduce healthcare costs. The acute care component of the program consisted of a bundle of interventions focused on improving coordination of care for all patients, including a “bridge to home” discharge process, as they transitioned back to the community from inpatient admission. The bundle included the following: early screening for discharge planning to predict needed postdischarge services; discussion in daily multidisciplinary rounds about goals and priorities of the hospitalization and potential postdischarge needs; patient and family self-care management; education enhanced medication management, including the option of “medications in hand” at the time of discharge; postdischarge telephone follow-up by nurses; and, for patients identified as high-risk, a “transition guide” (a nurse who works with the patient via home visits and by phone to optimize compliance with care for 30 days postdischarge).6 While the primary endpoints of the J-CHiP program were to improve clinical outcomes and reduce healthcare costs, we were also interested in the impact of the program on care coordination processes in the acute care setting. This created the need for an instrument to measure healthcare professionals’ views of care coordination in their immediate work environments.

We began our search for existing measures by reviewing the Coordination Measures Atlas published in 2014.7 Although this report evaluates over 80 different measures of care coordination, most of them focus on the perspective of the patient and/or family members, on specific conditions, and on primary care or outpatient settings.7,8 We were unable to identify an existing measure from the provider perspective, designed for the inpatient setting, that was both brief but comprehensive enough to cover a range of care coordination domains.8

Consequently, our first aim was to develop a brief, comprehensive tool to measure care coordination from the perspective of hospital inpatient staff that could be used to compare different units or types of providers, or to conduct longitudinal assessment. The second aim was to conduct a preliminary evaluation of the tool in our healthcare setting, including to assess its psychometric properties, to describe provider perceptions of care coordination after the implementation of J-CHiP, and to explore potential differences among departments, types of professionals, and between the 2 hospitals.

METHODS

Development of the Care Coordination Questionnaire

The survey was developed in collaboration with leaders of the J-CHiP Acute Care Team. We met at the outset and on multiple subsequent occasions to align survey domains with the main components of the J-CHiP acute care intervention and to assure that the survey would be relevant and understandable to a variety of multidisciplinary professionals, including physicians, nurses, social workers, physical therapists, and other health professionals. Care was taken to avoid redundancy with existing evaluation efforts and to minimize respondent burden. This process helped to ensure the content validity of the items, the usefulness of the results, and the future usability of the tool.

We modeled the Care Coordination Questionnaire (CCQ) after the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ),9 a widely used survey that is deployed approximately annually at JHH and JHBMC. While the SAQ focuses on healthcare provider attitudes about issues relevant to patient safety (often referred to as safety climate or safety culture), this new tool was designed to focus on healthcare professionals’ attitudes about care coordination. Similar to the way that the SAQ “elicits a snapshot of the safety climate through surveys of frontline worker perceptions,” we sought to elicit a picture of our care coordination climate through a survey of frontline hospital staff.

The CCQ was built upon the domains and approaches to care coordination described in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Care Coordination Atlas.3 This report identifies 9 mechanisms for achieving care coordination, including the following: Establish Accountability or Negotiate Responsibility; Communicate; Facilitate Transitions; Assess Needs and Goals; Create a Proactive Plan of Care; Monitor, Follow Up, and Respond to Change; Support Self-Management Goals; Link to Community Resources; and Align Resources with Patient and Population Needs; as well as 5 broad approaches commonly used to improve the delivery of healthcare, including Teamwork Focused on Coordination, Healthcare Home, Care Management, Medication Management, and Health IT-Enabled Coordination.7 We generated at least 1 item to represent 8 of the 9 domains, as well as the broad approach described as Teamwork Focused on Coordination. After developing an initial set of items, we sought input from 3 senior leaders of the J-CHiP Acute Care Team to determine if the items covered the care coordination domains of interest, and to provide feedback on content validity. To test the interpretability of survey items and consistency across professional groups, we sent an initial version of the survey questions to at least 1 person from each of the following professional groups: hospitalist, social worker, case manager, clinical pharmacist, and nurse. We asked them to review all of our survey questions and to provide us with feedback on all aspects of the questions, such as whether they believed the questions were relevant and understandable to the members of their professional discipline, the appropriateness of the wording of the questions, and other comments. Modifications were made to the content and wording of the questions based on the feedback received. The final draft of the questionnaire was reviewed by the leadership team of the J-CHiP Acute Care Team to ensure its usefulness in providing actionable information.

The resulting 12-item questionnaire used a 5-point Likert response scale ranging from 1 = “disagree strongly” to 5 = “agree strongly,” and an additional option of “not applicable (N/A).” To help assess construct validity, a global question was added at the end of the questionnaire asking, “Overall, how would you rate the care coordination at the hospital of your primary work setting?” The response was measured on a 10-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = “totally uncoordinated care” to 10 = “perfectly coordinated care” (see Appendix). In addition, the questionnaire requested information about the respondents’ gender, position, and their primary unit, department, and hospital affiliation.

Data Collection Procedures

An invitation to complete an anonymous questionnaire was sent to the following inpatient care professionals: all nursing staff working on care coordination units in the departments of medicine, surgery, and neurology/neurosurgery, as well as physicians, pharmacists, acute care therapists (eg, occupational and physical therapists), and other frontline staff. All healthcare staff fitting these criteria was sent an e-mail with a request to fill out the survey online using QualtricsTM (Qualtrics Labs Inc., Provo, UT), as well as multiple follow-up reminders. The participants worked either at the JHH (a 1194-bed tertiary academic medical center in Baltimore, MD) or the JHBMC (a 440-bed academic community hospital located nearby). Data were collected from October 2015 through January 2016.

Analysis

Means and standard deviations were calculated by treating the responses as continuous variables. We tried 3 different methods to handle missing data: (1) without imputation, (2) imputing the mean value of each item, and (3) substituting a neutral score. Because all 3 methods produced very similar results, we treated the N/A responses as missing values without imputation for simplicity of analysis. We used STATA 13.1 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas) to analyze the data.

To identify subscales, we performed exploratory factor analysis on responses to the 12 specific items. Promax rotation was selected based on the simple structure. Subscale scores for each respondent were generated by computing the mean of responses to the items in the subscale. Internal consistency reliability of the subscales was estimated using Cronbach’s alpha. We calculated Pearson correlation coefficients for the items in each subscale, and examined Cronbach’s alpha deleting each item in turn. For each of the subscales identified and the global scale, we calculated the mean, standard deviation, median and interquartile range. Although distributions of scores tended to be non-normal, this was done to increase interpretability. We also calculated percent scoring at the ceiling (highest possible score).

We analyzed the data with 3 research questions in mind: Was there a difference in perceptions of care coordination between (1) staff affiliated with the 2 different hospitals, (2) staff affiliated with different clinical departments, or (3) staff with different professional roles? For comparisons based on hospital and department, and type of professional, nonparametric tests (Wilcoxon rank-sum and Kruskal-Wallis test) were used with a level of statistical significance set at 0.05. The comparison between hospitals and departments was made only among nurses to minimize the confounding effect of different distribution of professionals. We tested the distribution of “years in specialty” between hospitals and departments for this comparison using Pearson’s χ2 test. The difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.167 for hospitals, and P = 0.518 for departments), so we assumed that the potential confounding effect of this variable was negligible in this analysis. The comparison of scores within each professional group used the Friedman test. Pearson’s χ2 test was used to compare the baseline characteristics between 2 hospitals.

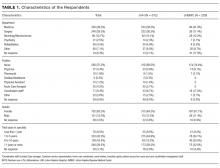

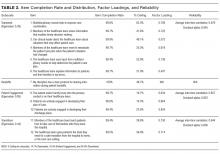

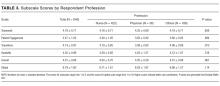

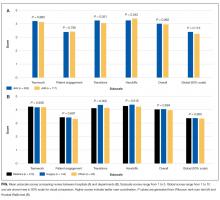

RESULTS

Among the 1486 acute care professionals asked to participate in the survey, 841 completed the questionnaire (response rate 56.6%). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants from each hospital. Table 2 summarizes the item response rates, proportion scoring at the ceiling, and weighting from the factor analysis. All items had completion rates of 99.2% or higher, with N/A responses ranging from 0% (item 2) to 3.1% (item 7). The percent scoring at the ceiling was 1.7% for the global item and ranged from 18.3% up to 63.3% for other individual items.

We also examined differences in perceptions of care coordination among nursing units to illustrate the tool’s ability to detect variation in Patient Engagement subscale scores for JHH nurses (see Appendix).

DISCUSSION

This study resulted in one of the first measurement tools to succinctly measure multiple aspects of care coordination in the hospital from the perspective of healthcare professionals. Given the hectic work environment of healthcare professionals, and the increasing emphasis on collecting data for evaluation and improvement, it is important to minimize respondent burden. This effort was catalyzed by a multifaceted initiative to redesign acute care delivery and promote seamless transitions of care, supported by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. In initial testing, this questionnaire has evidence for reliability and validity. It was encouraging to find that the preliminary psychometric performance of the measure was very similar in 2 different settings of a tertiary academic hospital and a community hospital.

Our analysis of the survey data explored potential differences between the 2 hospitals, among different types of healthcare professionals and across different departments. Although we expected differences, we had no specific hypotheses about what those differences might be, and, in fact, did not observe any substantial differences. This could be taken to indicate that the intervention was uniformly and successfully implemented in both hospitals, and engaged various professionals in different departments. The ability to detect differences in care coordination at the nursing unit level could also prove to be beneficial for more precisely targeting where process improvement is needed. Further data collection and analyses should be conducted to more systematically compare units and to help identify those where practice is most advanced and those where improvements may be needed. It would also be informative to link differences in care coordination scores with patient outcomes. In addition, differences identified on specific domains between professional groups could be helpful to identify where greater efforts are needed to improve interdisciplinary practice. Sampling strategies stratified by provider type would need to be targeted to make this kind of analysis informative.

The consistently lower scores observed for patient engagement, from the perspective of care professionals in all groups, suggest that this is an area where improvement is needed. These findings are consistent with published reports on the common failure by hospitals to include patients as a member of their own care team. In addition to measuring care processes from the perspective of frontline healthcare workers, future evaluations within the healthcare system would also benefit from including data collected from the perspective of the patient and family.

This study had some limitations. First, there may be more than 4 domains of care coordination that are important and can be measured in the acute care setting from provider perspective. However, the addition of more domains should be balanced against practicality and respondent burden. It may be possible to further clarify priority domains in hospital settings as opposed to the primary care setting. Future research should be directed to find these areas and to develop a more comprehensive, yet still concise measurement instrument. Second, the tool was developed to measure the impact of a large-scale intervention, and to fit into the specific context of 2 hospitals. Therefore, it should be tested in different settings of hospital care to see how it performs. However, virtually all hospitals in the United States today are adapting to changes in both financing and healthcare delivery. A tool such as the one described in this paper could be helpful to many organizations. Third, the scoring system for the overall scale score is not weighted and therefore reflects teamwork more than other components of care coordination, which are represented by fewer items. In general, we believe that use of the subscale scores may be more informative. Alternative scoring systems might also be proposed, including item weighting based on factor scores.

For the purposes of evaluation in this specific instance, we only collected data at a single point in time, after the intervention had been deployed. Thus, we were not able to evaluate the effectiveness of the J-CHiP intervention. We also did not intend to focus too much on the differences between units, given the limited number of respondents from individual units. It would be useful to collect more data at future time points, both to test the responsiveness of the scales and to evaluate the impact of future interventions at both the hospital and unit level.

The preliminary data from this study have generated insights about gaps in current practice, such as in engaging patients in the inpatient care process. It has also increased awareness by hospital leaders about the need to achieve high reliability in the adoption of new procedures and interdisciplinary practice. This tool might be used to find areas in need of improvement, to evaluate the effect of initiatives to improve care coordination, to monitor the change over time in the perception of care coordination among healthcare professionals, and to develop better intervention strategies for coordination activities in acute care settings. Additional research is needed to provide further evidence for the reliability and validity of this measure in diverse settings.

Disclosure

The project described was supported by Grant Number 1C1CMS331053-01-00 from the US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the US Department of Health and Human Services or any of its agencies. The research presented was conducted by the awardee. Results may or may not be consistent with or confirmed by the findings of the independent evaluation contractor.

The authors have no other disclosures.

1. McDonald KM, Sundaram V, Bravata DM, et al. Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies (Vol. 7: Care Coordination). Technical Reviews, No. 9.7. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2007. PubMed

2. Adams K, Corrigan J. Priority areas for national action: transforming health care quality. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. PubMed

3. Renders CM, Valk GD, Griffin S, Wagner EH, Eijk JT, Assendelft WJ. Interventions to improve the management of diabetes mellitus in primary care, outpatient and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001(1):CD001481. PubMed

4. McAlister FA, Lawson FM, Teo KK, Armstrong PW. A systematic review of randomized trials of disease management programs in heart failure. Am J Med. 2001;110(5):378-384. PubMed

5. Bruce ML, Raue PJ, Reilly CF, et al. Clinical effectiveness of integrating depression care management into medicare home health: the Depression CAREPATH Randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(1):55-64. PubMed

6. Berkowitz SA, Brown P, Brotman DJ, et al. Case Study: Johns Hopkins Community Health Partnership: A model for transformation. Healthc (Amst). 2016;4(4):264-270. PubMed

7. McDonald. KM, Schultz. E, Albin. L, et al. Care Coordination Measures Atlas Version 4. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014.

8 Schultz EM, Pineda N, Lonhart J, Davies SM, McDonald KM. A systematic review of the care coordination measurement landscape. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:119. PubMed

9. Sexton JB, Helmreich RL, Neilands TB, et al. The Safety Attitudes Questionnaire: psychometric properties, benchmarking data, and emerging research. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:44. PubMed

Care Coordination has been defined as “…the deliberate organization of patient care activities between two or more participants (including the patient) involved in a patient’s care to facilitate the appropriate delivery of healthcare services.”1 The Institute of Medicine identified care coordination as a key strategy to improve the American healthcare system,2 and evidence has been building that well-coordinated care improves patient outcomes and reduces healthcare costs associated with chronic conditions.3-5 In 2012, Johns Hopkins Medicine was awarded a Healthcare Innovation Award by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to improve coordination of care across the continuum of care for adult patients admitted to Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) and Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center (JHBMC), and for high-risk low-income Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries receiving ambulatory care in targeted zip codes. The purpose of this project, known as the Johns Hopkins Community Health Partnership (J-CHiP), was to improve health and healthcare and to reduce healthcare costs. The acute care component of the program consisted of a bundle of interventions focused on improving coordination of care for all patients, including a “bridge to home” discharge process, as they transitioned back to the community from inpatient admission. The bundle included the following: early screening for discharge planning to predict needed postdischarge services; discussion in daily multidisciplinary rounds about goals and priorities of the hospitalization and potential postdischarge needs; patient and family self-care management; education enhanced medication management, including the option of “medications in hand” at the time of discharge; postdischarge telephone follow-up by nurses; and, for patients identified as high-risk, a “transition guide” (a nurse who works with the patient via home visits and by phone to optimize compliance with care for 30 days postdischarge).6 While the primary endpoints of the J-CHiP program were to improve clinical outcomes and reduce healthcare costs, we were also interested in the impact of the program on care coordination processes in the acute care setting. This created the need for an instrument to measure healthcare professionals’ views of care coordination in their immediate work environments.

We began our search for existing measures by reviewing the Coordination Measures Atlas published in 2014.7 Although this report evaluates over 80 different measures of care coordination, most of them focus on the perspective of the patient and/or family members, on specific conditions, and on primary care or outpatient settings.7,8 We were unable to identify an existing measure from the provider perspective, designed for the inpatient setting, that was both brief but comprehensive enough to cover a range of care coordination domains.8

Consequently, our first aim was to develop a brief, comprehensive tool to measure care coordination from the perspective of hospital inpatient staff that could be used to compare different units or types of providers, or to conduct longitudinal assessment. The second aim was to conduct a preliminary evaluation of the tool in our healthcare setting, including to assess its psychometric properties, to describe provider perceptions of care coordination after the implementation of J-CHiP, and to explore potential differences among departments, types of professionals, and between the 2 hospitals.

METHODS

Development of the Care Coordination Questionnaire

The survey was developed in collaboration with leaders of the J-CHiP Acute Care Team. We met at the outset and on multiple subsequent occasions to align survey domains with the main components of the J-CHiP acute care intervention and to assure that the survey would be relevant and understandable to a variety of multidisciplinary professionals, including physicians, nurses, social workers, physical therapists, and other health professionals. Care was taken to avoid redundancy with existing evaluation efforts and to minimize respondent burden. This process helped to ensure the content validity of the items, the usefulness of the results, and the future usability of the tool.

We modeled the Care Coordination Questionnaire (CCQ) after the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ),9 a widely used survey that is deployed approximately annually at JHH and JHBMC. While the SAQ focuses on healthcare provider attitudes about issues relevant to patient safety (often referred to as safety climate or safety culture), this new tool was designed to focus on healthcare professionals’ attitudes about care coordination. Similar to the way that the SAQ “elicits a snapshot of the safety climate through surveys of frontline worker perceptions,” we sought to elicit a picture of our care coordination climate through a survey of frontline hospital staff.

The CCQ was built upon the domains and approaches to care coordination described in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Care Coordination Atlas.3 This report identifies 9 mechanisms for achieving care coordination, including the following: Establish Accountability or Negotiate Responsibility; Communicate; Facilitate Transitions; Assess Needs and Goals; Create a Proactive Plan of Care; Monitor, Follow Up, and Respond to Change; Support Self-Management Goals; Link to Community Resources; and Align Resources with Patient and Population Needs; as well as 5 broad approaches commonly used to improve the delivery of healthcare, including Teamwork Focused on Coordination, Healthcare Home, Care Management, Medication Management, and Health IT-Enabled Coordination.7 We generated at least 1 item to represent 8 of the 9 domains, as well as the broad approach described as Teamwork Focused on Coordination. After developing an initial set of items, we sought input from 3 senior leaders of the J-CHiP Acute Care Team to determine if the items covered the care coordination domains of interest, and to provide feedback on content validity. To test the interpretability of survey items and consistency across professional groups, we sent an initial version of the survey questions to at least 1 person from each of the following professional groups: hospitalist, social worker, case manager, clinical pharmacist, and nurse. We asked them to review all of our survey questions and to provide us with feedback on all aspects of the questions, such as whether they believed the questions were relevant and understandable to the members of their professional discipline, the appropriateness of the wording of the questions, and other comments. Modifications were made to the content and wording of the questions based on the feedback received. The final draft of the questionnaire was reviewed by the leadership team of the J-CHiP Acute Care Team to ensure its usefulness in providing actionable information.

The resulting 12-item questionnaire used a 5-point Likert response scale ranging from 1 = “disagree strongly” to 5 = “agree strongly,” and an additional option of “not applicable (N/A).” To help assess construct validity, a global question was added at the end of the questionnaire asking, “Overall, how would you rate the care coordination at the hospital of your primary work setting?” The response was measured on a 10-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = “totally uncoordinated care” to 10 = “perfectly coordinated care” (see Appendix). In addition, the questionnaire requested information about the respondents’ gender, position, and their primary unit, department, and hospital affiliation.

Data Collection Procedures

An invitation to complete an anonymous questionnaire was sent to the following inpatient care professionals: all nursing staff working on care coordination units in the departments of medicine, surgery, and neurology/neurosurgery, as well as physicians, pharmacists, acute care therapists (eg, occupational and physical therapists), and other frontline staff. All healthcare staff fitting these criteria was sent an e-mail with a request to fill out the survey online using QualtricsTM (Qualtrics Labs Inc., Provo, UT), as well as multiple follow-up reminders. The participants worked either at the JHH (a 1194-bed tertiary academic medical center in Baltimore, MD) or the JHBMC (a 440-bed academic community hospital located nearby). Data were collected from October 2015 through January 2016.

Analysis

Means and standard deviations were calculated by treating the responses as continuous variables. We tried 3 different methods to handle missing data: (1) without imputation, (2) imputing the mean value of each item, and (3) substituting a neutral score. Because all 3 methods produced very similar results, we treated the N/A responses as missing values without imputation for simplicity of analysis. We used STATA 13.1 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas) to analyze the data.

To identify subscales, we performed exploratory factor analysis on responses to the 12 specific items. Promax rotation was selected based on the simple structure. Subscale scores for each respondent were generated by computing the mean of responses to the items in the subscale. Internal consistency reliability of the subscales was estimated using Cronbach’s alpha. We calculated Pearson correlation coefficients for the items in each subscale, and examined Cronbach’s alpha deleting each item in turn. For each of the subscales identified and the global scale, we calculated the mean, standard deviation, median and interquartile range. Although distributions of scores tended to be non-normal, this was done to increase interpretability. We also calculated percent scoring at the ceiling (highest possible score).

We analyzed the data with 3 research questions in mind: Was there a difference in perceptions of care coordination between (1) staff affiliated with the 2 different hospitals, (2) staff affiliated with different clinical departments, or (3) staff with different professional roles? For comparisons based on hospital and department, and type of professional, nonparametric tests (Wilcoxon rank-sum and Kruskal-Wallis test) were used with a level of statistical significance set at 0.05. The comparison between hospitals and departments was made only among nurses to minimize the confounding effect of different distribution of professionals. We tested the distribution of “years in specialty” between hospitals and departments for this comparison using Pearson’s χ2 test. The difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.167 for hospitals, and P = 0.518 for departments), so we assumed that the potential confounding effect of this variable was negligible in this analysis. The comparison of scores within each professional group used the Friedman test. Pearson’s χ2 test was used to compare the baseline characteristics between 2 hospitals.

RESULTS

Among the 1486 acute care professionals asked to participate in the survey, 841 completed the questionnaire (response rate 56.6%). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants from each hospital. Table 2 summarizes the item response rates, proportion scoring at the ceiling, and weighting from the factor analysis. All items had completion rates of 99.2% or higher, with N/A responses ranging from 0% (item 2) to 3.1% (item 7). The percent scoring at the ceiling was 1.7% for the global item and ranged from 18.3% up to 63.3% for other individual items.

We also examined differences in perceptions of care coordination among nursing units to illustrate the tool’s ability to detect variation in Patient Engagement subscale scores for JHH nurses (see Appendix).

DISCUSSION

This study resulted in one of the first measurement tools to succinctly measure multiple aspects of care coordination in the hospital from the perspective of healthcare professionals. Given the hectic work environment of healthcare professionals, and the increasing emphasis on collecting data for evaluation and improvement, it is important to minimize respondent burden. This effort was catalyzed by a multifaceted initiative to redesign acute care delivery and promote seamless transitions of care, supported by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. In initial testing, this questionnaire has evidence for reliability and validity. It was encouraging to find that the preliminary psychometric performance of the measure was very similar in 2 different settings of a tertiary academic hospital and a community hospital.