User login

Quality Improvement in Health Care: From Conceptual Frameworks and Definitions to Implementation

As the movement to improve quality in health care has evolved over the past several decades, organizations whose missions focus on supporting and promoting quality in health care have defined essential concepts, standards, and measures that comprise quality and that can be used to guide quality improvement (QI) work. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines quality in clinical care as safe, effective, and people-centered service.1 These 3 pillars of quality form the foundation of a quality system aiming to deliver health care in a timely, equitable, efficient, and integrated manner. The WHO estimates that 5.7 to 8.4 million deaths occur yearly in low- and middle-income countries due to poor quality care. Regarding safety, patient harm from unsafe care is estimated to be among the top 10 causes of death and disability worldwide.2 A health care QI plan involves identifying areas for improvement, setting measurable goals, implementing evidence-based strategies and interventions, monitoring progress toward achieving those goals, and continuously evaluating and adjusting the plan as needed to ensure sustained improvement over time. Such a plan can be implemented at various levels of health care organizations, from individual clinical units to entire hospitals or even regional health care systems.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) identifies 5 domains of quality in health care: effectiveness, efficiency, equity, patient-centeredness, and safety.3 Effectiveness relies on providing care processes supported by scientific evidence and achieving desired outcomes in the IOM recommendations. The primary efficiency aim maximizes the quality of health care delivered or the benefits achieved for a given resource unit. Equity relates to providing health care of equal quality to all individuals, regardless of personal characteristics. Moreover, patient-centeredness relates to meeting patients’ needs and preferences and providing education and support. Safety relates to avoiding actual or potential harm. Timeliness relates to obtaining needed care while minimizing delays. Finally, the IOM defines health care quality as the systematic evaluation and provision of evidence-based and safe care characterized by a culture of continuous improvement, resulting in optimal health outcomes. Taking all these concepts into consideration, 4 key attributes have been identified as essential to the global definition of health care quality: effectiveness, safety, culture of continuous improvement, and desired outcomes. This conceptualization of health care quality encompasses the fundamental components and has the potential to enhance the delivery of care. This definition’s theoretical and practical implications provide a comprehensive and consistent understanding of the elements required to improve health care and maintain public trust.

Health care quality is a dynamic, ever-evolving construct that requires continuous assessment and evaluation to ensure the delivery of care meets the changing needs of society. The National Quality Forum’s National Voluntary Consensus Standards for health care provide measures, guidance, and recommendations on achieving effective outcomes through evidence-based practices.4 These standards establish criteria by which health care systems and providers can assess and improve their quality performance.

In the United States, in order to implement and disseminate best practices, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) developed Quality Payment Programs that offer incentives to health care providers to improve the quality of care delivery. This CMS program evaluates providers based on their performance in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System performance categories.5 These include measures related to patient experience, cost, clinical quality, improvement activities, and the use of certified electronic health record technology. The scores that providers receive are used to determine their performance-based reimbursements under Medicare’s fee-for-service program.

The concept of health care quality is also applicable in other countries. In the United Kingdom, QI initiatives are led by the Department of Health and Social Care. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) produces guidelines on best practices to ensure that care delivery meets established safety and quality standards, reaching cost-effectiveness excellence.6 In Australia, the Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Health Care is responsible for setting benchmarks for performance in health care systems through a clear, structured agenda.7 Ultimately, health care quality is a complex and multifaceted issue that requires a comprehensive approach to ensure the best outcomes for patients. With the implementation of measures such as the CMS Quality Payment Programs and NICE guidelines, health care organizations can take steps to ensure their systems of care delivery reflect evidence-based practices and demonstrate a commitment to providing high-quality care.

Implementing a health care QI plan that encompasses the 4 key attributes of health care quality—effectiveness, safety, culture of continuous improvement, and desired outcomes—requires collaboration among different departments and stakeholders and a data-driven approach to decision-making. Effective communication with patients and their families is critical to ensuring that their needs are being met and that they are active partners in their health care journey. While a health care QI plan is essential for delivering high-quality, safe patient care, it also helps health care organizations comply with regulatory requirements, meet accreditation standards, and stay competitive in the ever-evolving health care landscape.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH; Ebrahim.Barkoudah@baystatehealth.org

1. World Health Organization. Quality of care. Accessed on May 17, 2023. www.who.int/health-topics/quality-of-care#tab=tab_1

2. World Health Organization. Patient safety. Accessed on May 17, 2023 www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/patient-safety

3. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Understanding quality measurement. Accessed on May 17, 2023. www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/chtoolbx/understand/index.html

4. Ferrell B, Connor SR, Cordes A, et al. The national agenda for quality palliative care: the National Consensus Project and the National Quality Forum. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(6):737-744. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.024

5. U.S Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Quality payment program. Accessed on March 14, 2023 qpp.cms.gov/mips/overview

6. Claxton K, Martin S, Soares M, et al. Methods for the estimation of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence cost-effectiveness threshold. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(14):1-503, v-vi. doi: 10.3310/hta19140

7. Braithwaite J, Healy J, Dwan K. The Governance of Health Safety and Quality, Commonwealth of Australia. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://regnet.anu.edu.au/research/publications/3626/governance-health-safety-and-quality 2005

As the movement to improve quality in health care has evolved over the past several decades, organizations whose missions focus on supporting and promoting quality in health care have defined essential concepts, standards, and measures that comprise quality and that can be used to guide quality improvement (QI) work. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines quality in clinical care as safe, effective, and people-centered service.1 These 3 pillars of quality form the foundation of a quality system aiming to deliver health care in a timely, equitable, efficient, and integrated manner. The WHO estimates that 5.7 to 8.4 million deaths occur yearly in low- and middle-income countries due to poor quality care. Regarding safety, patient harm from unsafe care is estimated to be among the top 10 causes of death and disability worldwide.2 A health care QI plan involves identifying areas for improvement, setting measurable goals, implementing evidence-based strategies and interventions, monitoring progress toward achieving those goals, and continuously evaluating and adjusting the plan as needed to ensure sustained improvement over time. Such a plan can be implemented at various levels of health care organizations, from individual clinical units to entire hospitals or even regional health care systems.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) identifies 5 domains of quality in health care: effectiveness, efficiency, equity, patient-centeredness, and safety.3 Effectiveness relies on providing care processes supported by scientific evidence and achieving desired outcomes in the IOM recommendations. The primary efficiency aim maximizes the quality of health care delivered or the benefits achieved for a given resource unit. Equity relates to providing health care of equal quality to all individuals, regardless of personal characteristics. Moreover, patient-centeredness relates to meeting patients’ needs and preferences and providing education and support. Safety relates to avoiding actual or potential harm. Timeliness relates to obtaining needed care while minimizing delays. Finally, the IOM defines health care quality as the systematic evaluation and provision of evidence-based and safe care characterized by a culture of continuous improvement, resulting in optimal health outcomes. Taking all these concepts into consideration, 4 key attributes have been identified as essential to the global definition of health care quality: effectiveness, safety, culture of continuous improvement, and desired outcomes. This conceptualization of health care quality encompasses the fundamental components and has the potential to enhance the delivery of care. This definition’s theoretical and practical implications provide a comprehensive and consistent understanding of the elements required to improve health care and maintain public trust.

Health care quality is a dynamic, ever-evolving construct that requires continuous assessment and evaluation to ensure the delivery of care meets the changing needs of society. The National Quality Forum’s National Voluntary Consensus Standards for health care provide measures, guidance, and recommendations on achieving effective outcomes through evidence-based practices.4 These standards establish criteria by which health care systems and providers can assess and improve their quality performance.

In the United States, in order to implement and disseminate best practices, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) developed Quality Payment Programs that offer incentives to health care providers to improve the quality of care delivery. This CMS program evaluates providers based on their performance in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System performance categories.5 These include measures related to patient experience, cost, clinical quality, improvement activities, and the use of certified electronic health record technology. The scores that providers receive are used to determine their performance-based reimbursements under Medicare’s fee-for-service program.

The concept of health care quality is also applicable in other countries. In the United Kingdom, QI initiatives are led by the Department of Health and Social Care. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) produces guidelines on best practices to ensure that care delivery meets established safety and quality standards, reaching cost-effectiveness excellence.6 In Australia, the Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Health Care is responsible for setting benchmarks for performance in health care systems through a clear, structured agenda.7 Ultimately, health care quality is a complex and multifaceted issue that requires a comprehensive approach to ensure the best outcomes for patients. With the implementation of measures such as the CMS Quality Payment Programs and NICE guidelines, health care organizations can take steps to ensure their systems of care delivery reflect evidence-based practices and demonstrate a commitment to providing high-quality care.

Implementing a health care QI plan that encompasses the 4 key attributes of health care quality—effectiveness, safety, culture of continuous improvement, and desired outcomes—requires collaboration among different departments and stakeholders and a data-driven approach to decision-making. Effective communication with patients and their families is critical to ensuring that their needs are being met and that they are active partners in their health care journey. While a health care QI plan is essential for delivering high-quality, safe patient care, it also helps health care organizations comply with regulatory requirements, meet accreditation standards, and stay competitive in the ever-evolving health care landscape.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH; Ebrahim.Barkoudah@baystatehealth.org

As the movement to improve quality in health care has evolved over the past several decades, organizations whose missions focus on supporting and promoting quality in health care have defined essential concepts, standards, and measures that comprise quality and that can be used to guide quality improvement (QI) work. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines quality in clinical care as safe, effective, and people-centered service.1 These 3 pillars of quality form the foundation of a quality system aiming to deliver health care in a timely, equitable, efficient, and integrated manner. The WHO estimates that 5.7 to 8.4 million deaths occur yearly in low- and middle-income countries due to poor quality care. Regarding safety, patient harm from unsafe care is estimated to be among the top 10 causes of death and disability worldwide.2 A health care QI plan involves identifying areas for improvement, setting measurable goals, implementing evidence-based strategies and interventions, monitoring progress toward achieving those goals, and continuously evaluating and adjusting the plan as needed to ensure sustained improvement over time. Such a plan can be implemented at various levels of health care organizations, from individual clinical units to entire hospitals or even regional health care systems.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) identifies 5 domains of quality in health care: effectiveness, efficiency, equity, patient-centeredness, and safety.3 Effectiveness relies on providing care processes supported by scientific evidence and achieving desired outcomes in the IOM recommendations. The primary efficiency aim maximizes the quality of health care delivered or the benefits achieved for a given resource unit. Equity relates to providing health care of equal quality to all individuals, regardless of personal characteristics. Moreover, patient-centeredness relates to meeting patients’ needs and preferences and providing education and support. Safety relates to avoiding actual or potential harm. Timeliness relates to obtaining needed care while minimizing delays. Finally, the IOM defines health care quality as the systematic evaluation and provision of evidence-based and safe care characterized by a culture of continuous improvement, resulting in optimal health outcomes. Taking all these concepts into consideration, 4 key attributes have been identified as essential to the global definition of health care quality: effectiveness, safety, culture of continuous improvement, and desired outcomes. This conceptualization of health care quality encompasses the fundamental components and has the potential to enhance the delivery of care. This definition’s theoretical and practical implications provide a comprehensive and consistent understanding of the elements required to improve health care and maintain public trust.

Health care quality is a dynamic, ever-evolving construct that requires continuous assessment and evaluation to ensure the delivery of care meets the changing needs of society. The National Quality Forum’s National Voluntary Consensus Standards for health care provide measures, guidance, and recommendations on achieving effective outcomes through evidence-based practices.4 These standards establish criteria by which health care systems and providers can assess and improve their quality performance.

In the United States, in order to implement and disseminate best practices, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) developed Quality Payment Programs that offer incentives to health care providers to improve the quality of care delivery. This CMS program evaluates providers based on their performance in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System performance categories.5 These include measures related to patient experience, cost, clinical quality, improvement activities, and the use of certified electronic health record technology. The scores that providers receive are used to determine their performance-based reimbursements under Medicare’s fee-for-service program.

The concept of health care quality is also applicable in other countries. In the United Kingdom, QI initiatives are led by the Department of Health and Social Care. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) produces guidelines on best practices to ensure that care delivery meets established safety and quality standards, reaching cost-effectiveness excellence.6 In Australia, the Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Health Care is responsible for setting benchmarks for performance in health care systems through a clear, structured agenda.7 Ultimately, health care quality is a complex and multifaceted issue that requires a comprehensive approach to ensure the best outcomes for patients. With the implementation of measures such as the CMS Quality Payment Programs and NICE guidelines, health care organizations can take steps to ensure their systems of care delivery reflect evidence-based practices and demonstrate a commitment to providing high-quality care.

Implementing a health care QI plan that encompasses the 4 key attributes of health care quality—effectiveness, safety, culture of continuous improvement, and desired outcomes—requires collaboration among different departments and stakeholders and a data-driven approach to decision-making. Effective communication with patients and their families is critical to ensuring that their needs are being met and that they are active partners in their health care journey. While a health care QI plan is essential for delivering high-quality, safe patient care, it also helps health care organizations comply with regulatory requirements, meet accreditation standards, and stay competitive in the ever-evolving health care landscape.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH; Ebrahim.Barkoudah@baystatehealth.org

1. World Health Organization. Quality of care. Accessed on May 17, 2023. www.who.int/health-topics/quality-of-care#tab=tab_1

2. World Health Organization. Patient safety. Accessed on May 17, 2023 www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/patient-safety

3. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Understanding quality measurement. Accessed on May 17, 2023. www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/chtoolbx/understand/index.html

4. Ferrell B, Connor SR, Cordes A, et al. The national agenda for quality palliative care: the National Consensus Project and the National Quality Forum. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(6):737-744. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.024

5. U.S Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Quality payment program. Accessed on March 14, 2023 qpp.cms.gov/mips/overview

6. Claxton K, Martin S, Soares M, et al. Methods for the estimation of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence cost-effectiveness threshold. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(14):1-503, v-vi. doi: 10.3310/hta19140

7. Braithwaite J, Healy J, Dwan K. The Governance of Health Safety and Quality, Commonwealth of Australia. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://regnet.anu.edu.au/research/publications/3626/governance-health-safety-and-quality 2005

1. World Health Organization. Quality of care. Accessed on May 17, 2023. www.who.int/health-topics/quality-of-care#tab=tab_1

2. World Health Organization. Patient safety. Accessed on May 17, 2023 www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/patient-safety

3. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Understanding quality measurement. Accessed on May 17, 2023. www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/chtoolbx/understand/index.html

4. Ferrell B, Connor SR, Cordes A, et al. The national agenda for quality palliative care: the National Consensus Project and the National Quality Forum. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(6):737-744. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.024

5. U.S Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Quality payment program. Accessed on March 14, 2023 qpp.cms.gov/mips/overview

6. Claxton K, Martin S, Soares M, et al. Methods for the estimation of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence cost-effectiveness threshold. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(14):1-503, v-vi. doi: 10.3310/hta19140

7. Braithwaite J, Healy J, Dwan K. The Governance of Health Safety and Quality, Commonwealth of Australia. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://regnet.anu.edu.au/research/publications/3626/governance-health-safety-and-quality 2005

JCOM: 30 Years of Advancing Quality Improvement and Innovation in Care Delivery

This year marks the publication of the 30th volume of the Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management (JCOM). As we celebrate JCOM’s 30th year, we look forward to the future and continuing the journey to inform quality improvement leaders and practitioners about advances in the field and share experiences. The path forward on this journey involves collaboration across stakeholders, the application of innovative improvement methods, and a commitment to achieving health equity. Health care quality improvement plans must prioritize patient-centered care, promote evidence-based practices and continuous learning, and establish clear metrics to measure progress and success. Furthermore, engagement with patients and communities must be at the forefront of any quality improvement plan, as their perspectives and experiences are essential to understanding and addressing the root causes of disparities in health care delivery. Additionally, effective communication and coordination among health care providers, administrators, policymakers, and other stakeholders are crucial to achieving sustainable improvements in health care quality.

JCOM’s mission is to serve as a platform for sharing knowledge, experiences, and best practices to improve patient outcomes and promote health equity. The vision encompasses a world where all individuals have access to high-quality, patient-centered health care that is free of disparities and achieves optimal health outcomes. JCOM’s strategy is to publish articles that showcase innovative quality improvement initiatives, share evidence-based practices and research findings, highlight successful collaborations, and provide practical guidance for health care professionals to implement quality improvement initiatives in their organizations.

We believe that by sharing these insights and experiences, we can accelerate progress toward achieving equitable and high-quality health care for all individuals and communities, regardless of their socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, gender identity, or any other factor that may impact their access to care and health outcomes. We continue to welcome submissions from all health care professionals, researchers, and other stakeholders involved in quality improvement initiatives. Together, we can work toward a future where every individual has access to the highest quality of health care and experiences equitable health outcomes.

A comprehensive and collaborative approach to health care quality improvement, which is led by a peer review process and scientific publication of the progress, is a necessary part of ensuring that all patients receive high-quality care that is equitable and patient-centered. The future of health care quality will require further research and scholarly work in the areas of training and development, data infrastructure and analytics, as well as technology-enabled solutions that support continuous improvement and innovation. Health care organizations can build a culture of quality improvement that drives meaningful progress toward achieving health equity and improving health care delivery for all by sharing the output from their research.

Thank you for joining us in this mission to improve health care quality, promote optimal health care delivery methods, and create a world where health care is not only accessible, but also equitable and of the highest standards. Let us continue to work toward building a health care system that prioritizes patient-centered care. Together, we can make a difference and ensure that every individual receives the care they need and deserve.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

This year marks the publication of the 30th volume of the Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management (JCOM). As we celebrate JCOM’s 30th year, we look forward to the future and continuing the journey to inform quality improvement leaders and practitioners about advances in the field and share experiences. The path forward on this journey involves collaboration across stakeholders, the application of innovative improvement methods, and a commitment to achieving health equity. Health care quality improvement plans must prioritize patient-centered care, promote evidence-based practices and continuous learning, and establish clear metrics to measure progress and success. Furthermore, engagement with patients and communities must be at the forefront of any quality improvement plan, as their perspectives and experiences are essential to understanding and addressing the root causes of disparities in health care delivery. Additionally, effective communication and coordination among health care providers, administrators, policymakers, and other stakeholders are crucial to achieving sustainable improvements in health care quality.

JCOM’s mission is to serve as a platform for sharing knowledge, experiences, and best practices to improve patient outcomes and promote health equity. The vision encompasses a world where all individuals have access to high-quality, patient-centered health care that is free of disparities and achieves optimal health outcomes. JCOM’s strategy is to publish articles that showcase innovative quality improvement initiatives, share evidence-based practices and research findings, highlight successful collaborations, and provide practical guidance for health care professionals to implement quality improvement initiatives in their organizations.

We believe that by sharing these insights and experiences, we can accelerate progress toward achieving equitable and high-quality health care for all individuals and communities, regardless of their socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, gender identity, or any other factor that may impact their access to care and health outcomes. We continue to welcome submissions from all health care professionals, researchers, and other stakeholders involved in quality improvement initiatives. Together, we can work toward a future where every individual has access to the highest quality of health care and experiences equitable health outcomes.

A comprehensive and collaborative approach to health care quality improvement, which is led by a peer review process and scientific publication of the progress, is a necessary part of ensuring that all patients receive high-quality care that is equitable and patient-centered. The future of health care quality will require further research and scholarly work in the areas of training and development, data infrastructure and analytics, as well as technology-enabled solutions that support continuous improvement and innovation. Health care organizations can build a culture of quality improvement that drives meaningful progress toward achieving health equity and improving health care delivery for all by sharing the output from their research.

Thank you for joining us in this mission to improve health care quality, promote optimal health care delivery methods, and create a world where health care is not only accessible, but also equitable and of the highest standards. Let us continue to work toward building a health care system that prioritizes patient-centered care. Together, we can make a difference and ensure that every individual receives the care they need and deserve.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

This year marks the publication of the 30th volume of the Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management (JCOM). As we celebrate JCOM’s 30th year, we look forward to the future and continuing the journey to inform quality improvement leaders and practitioners about advances in the field and share experiences. The path forward on this journey involves collaboration across stakeholders, the application of innovative improvement methods, and a commitment to achieving health equity. Health care quality improvement plans must prioritize patient-centered care, promote evidence-based practices and continuous learning, and establish clear metrics to measure progress and success. Furthermore, engagement with patients and communities must be at the forefront of any quality improvement plan, as their perspectives and experiences are essential to understanding and addressing the root causes of disparities in health care delivery. Additionally, effective communication and coordination among health care providers, administrators, policymakers, and other stakeholders are crucial to achieving sustainable improvements in health care quality.

JCOM’s mission is to serve as a platform for sharing knowledge, experiences, and best practices to improve patient outcomes and promote health equity. The vision encompasses a world where all individuals have access to high-quality, patient-centered health care that is free of disparities and achieves optimal health outcomes. JCOM’s strategy is to publish articles that showcase innovative quality improvement initiatives, share evidence-based practices and research findings, highlight successful collaborations, and provide practical guidance for health care professionals to implement quality improvement initiatives in their organizations.

We believe that by sharing these insights and experiences, we can accelerate progress toward achieving equitable and high-quality health care for all individuals and communities, regardless of their socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, gender identity, or any other factor that may impact their access to care and health outcomes. We continue to welcome submissions from all health care professionals, researchers, and other stakeholders involved in quality improvement initiatives. Together, we can work toward a future where every individual has access to the highest quality of health care and experiences equitable health outcomes.

A comprehensive and collaborative approach to health care quality improvement, which is led by a peer review process and scientific publication of the progress, is a necessary part of ensuring that all patients receive high-quality care that is equitable and patient-centered. The future of health care quality will require further research and scholarly work in the areas of training and development, data infrastructure and analytics, as well as technology-enabled solutions that support continuous improvement and innovation. Health care organizations can build a culture of quality improvement that drives meaningful progress toward achieving health equity and improving health care delivery for all by sharing the output from their research.

Thank you for joining us in this mission to improve health care quality, promote optimal health care delivery methods, and create a world where health care is not only accessible, but also equitable and of the highest standards. Let us continue to work toward building a health care system that prioritizes patient-centered care. Together, we can make a difference and ensure that every individual receives the care they need and deserve.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

Safety in Health Care: An Essential Pillar of Quality

Each year, 40,000 to 98,000 deaths occur due to medical errors.1 The Harvard Medical Practice Study (HMPS), published in 1991, found that 3.7% of hospitalized patients were harmed by adverse events and 1% were harmed by adverse events due to negligence.2 The latest HMPS showed that, despite significant improvements in patient safety over the past 3 decades, patient safety challenges persist. This study found that inpatient care leads to harm in nearly a quarter of patients, and that 1 in 4 of these adverse events are preventable.3

Since the first HMPS study was published, efforts to improve patient safety have focused on identifying causes of medical error and the design and implementation of interventions to mitigate errors. Factors contributing to medical errors have been well documented: the complexity of care delivery from inpatient to outpatient settings, with transitions of care and extensive use of medications; multiple comorbidities; and the fragmentation of care across multiple systems and specialties. Although most errors are related to process or system failure, accountability of each practitioner and clinician is essential to promoting a culture of safety. Many medical errors are preventable through multifaceted approaches employed throughout the phases of the care,4 with medication errors, both prescribing and administration, and diagnostic and treatment errors encompassing most risk prevention areas. Broadly, safety efforts should emphasize building a culture of safety where all safety events are reported, including near-miss events.

Two articles in this issue of JCOM address key elements of patient safety: building a safety culture and diagnostic error. Merchant et al5 report on an initiative designed to promote a safety culture by recognizing and rewarding staff who identify and report near misses. The tiered awards program they designed led to significantly increased staff participation in the safety awards nomination process and was associated with increased reporting of actual and close-call events and greater attendance at monthly safety forums. Goyal et al,6 noting that diagnostic error rates in hospitalized patients remain unacceptably high, provide a concise update on diagnostic error among inpatients, focusing on issues related to defining and measuring diagnostic errors and current strategies to improve diagnostic safety in hospitalized patients. In a third article, Sathi et al report on efforts to teach quality improvement (QI) methods to internal medicine trainees; their project increased residents’ knowledge of their patient panels and comfort with QI approaches and led to improved patient outcomes.

Major progress has been made to improve health care safety since the first HMPS was published. However, the latest HMPS shows that patient safety efforts must continue, given the persistent risk for patient harm in the current health care delivery system. Safety, along with clear accountability for identifying, reporting, and addressing errors, should be a top priority for health care systems throughout the preventive, diagnostic, and therapeutic phases of care.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

1. Clancy C, Munier W, Brady J. National healthcare quality report. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013.

2. Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(6):370-376. doi:10.1056/NEJM199102073240604

3. Bates DW, Levine DM, Salmasian H, et al. The safety of inpatient health care. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(2):142-153. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa2206117

4. Bates DW, Cullen DJ, Laird N, et al. Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events: implications for prevention. JAMA. 1995;274(1):29-34.

5. Merchant NB, O’Neal J, Murray JS. Development of a safety awards program at a Veterans Affairs health care system: a quality improvement initiative. J Clin Outcome Manag. 2023;30(1):9-16. doi:10.12788/jcom.0120

6. Goyal A, Martin-Doyle W, Dalal AK. Diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients. J Clin Outcome Manag. 2023;30(1):17-27. doi:10.12788/jcom.0121

7. Sathi K, Huang KTL, Chandler DM, et al. Teaching quality improvement to internal medicine residents to address patient care gaps in ambulatory quality metrics. J Clin Outcome Manag. 2023;30(1):1-6.doi:10.12788/jcom.0119

Each year, 40,000 to 98,000 deaths occur due to medical errors.1 The Harvard Medical Practice Study (HMPS), published in 1991, found that 3.7% of hospitalized patients were harmed by adverse events and 1% were harmed by adverse events due to negligence.2 The latest HMPS showed that, despite significant improvements in patient safety over the past 3 decades, patient safety challenges persist. This study found that inpatient care leads to harm in nearly a quarter of patients, and that 1 in 4 of these adverse events are preventable.3

Since the first HMPS study was published, efforts to improve patient safety have focused on identifying causes of medical error and the design and implementation of interventions to mitigate errors. Factors contributing to medical errors have been well documented: the complexity of care delivery from inpatient to outpatient settings, with transitions of care and extensive use of medications; multiple comorbidities; and the fragmentation of care across multiple systems and specialties. Although most errors are related to process or system failure, accountability of each practitioner and clinician is essential to promoting a culture of safety. Many medical errors are preventable through multifaceted approaches employed throughout the phases of the care,4 with medication errors, both prescribing and administration, and diagnostic and treatment errors encompassing most risk prevention areas. Broadly, safety efforts should emphasize building a culture of safety where all safety events are reported, including near-miss events.

Two articles in this issue of JCOM address key elements of patient safety: building a safety culture and diagnostic error. Merchant et al5 report on an initiative designed to promote a safety culture by recognizing and rewarding staff who identify and report near misses. The tiered awards program they designed led to significantly increased staff participation in the safety awards nomination process and was associated with increased reporting of actual and close-call events and greater attendance at monthly safety forums. Goyal et al,6 noting that diagnostic error rates in hospitalized patients remain unacceptably high, provide a concise update on diagnostic error among inpatients, focusing on issues related to defining and measuring diagnostic errors and current strategies to improve diagnostic safety in hospitalized patients. In a third article, Sathi et al report on efforts to teach quality improvement (QI) methods to internal medicine trainees; their project increased residents’ knowledge of their patient panels and comfort with QI approaches and led to improved patient outcomes.

Major progress has been made to improve health care safety since the first HMPS was published. However, the latest HMPS shows that patient safety efforts must continue, given the persistent risk for patient harm in the current health care delivery system. Safety, along with clear accountability for identifying, reporting, and addressing errors, should be a top priority for health care systems throughout the preventive, diagnostic, and therapeutic phases of care.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

Each year, 40,000 to 98,000 deaths occur due to medical errors.1 The Harvard Medical Practice Study (HMPS), published in 1991, found that 3.7% of hospitalized patients were harmed by adverse events and 1% were harmed by adverse events due to negligence.2 The latest HMPS showed that, despite significant improvements in patient safety over the past 3 decades, patient safety challenges persist. This study found that inpatient care leads to harm in nearly a quarter of patients, and that 1 in 4 of these adverse events are preventable.3

Since the first HMPS study was published, efforts to improve patient safety have focused on identifying causes of medical error and the design and implementation of interventions to mitigate errors. Factors contributing to medical errors have been well documented: the complexity of care delivery from inpatient to outpatient settings, with transitions of care and extensive use of medications; multiple comorbidities; and the fragmentation of care across multiple systems and specialties. Although most errors are related to process or system failure, accountability of each practitioner and clinician is essential to promoting a culture of safety. Many medical errors are preventable through multifaceted approaches employed throughout the phases of the care,4 with medication errors, both prescribing and administration, and diagnostic and treatment errors encompassing most risk prevention areas. Broadly, safety efforts should emphasize building a culture of safety where all safety events are reported, including near-miss events.

Two articles in this issue of JCOM address key elements of patient safety: building a safety culture and diagnostic error. Merchant et al5 report on an initiative designed to promote a safety culture by recognizing and rewarding staff who identify and report near misses. The tiered awards program they designed led to significantly increased staff participation in the safety awards nomination process and was associated with increased reporting of actual and close-call events and greater attendance at monthly safety forums. Goyal et al,6 noting that diagnostic error rates in hospitalized patients remain unacceptably high, provide a concise update on diagnostic error among inpatients, focusing on issues related to defining and measuring diagnostic errors and current strategies to improve diagnostic safety in hospitalized patients. In a third article, Sathi et al report on efforts to teach quality improvement (QI) methods to internal medicine trainees; their project increased residents’ knowledge of their patient panels and comfort with QI approaches and led to improved patient outcomes.

Major progress has been made to improve health care safety since the first HMPS was published. However, the latest HMPS shows that patient safety efforts must continue, given the persistent risk for patient harm in the current health care delivery system. Safety, along with clear accountability for identifying, reporting, and addressing errors, should be a top priority for health care systems throughout the preventive, diagnostic, and therapeutic phases of care.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

1. Clancy C, Munier W, Brady J. National healthcare quality report. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013.

2. Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(6):370-376. doi:10.1056/NEJM199102073240604

3. Bates DW, Levine DM, Salmasian H, et al. The safety of inpatient health care. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(2):142-153. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa2206117

4. Bates DW, Cullen DJ, Laird N, et al. Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events: implications for prevention. JAMA. 1995;274(1):29-34.

5. Merchant NB, O’Neal J, Murray JS. Development of a safety awards program at a Veterans Affairs health care system: a quality improvement initiative. J Clin Outcome Manag. 2023;30(1):9-16. doi:10.12788/jcom.0120

6. Goyal A, Martin-Doyle W, Dalal AK. Diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients. J Clin Outcome Manag. 2023;30(1):17-27. doi:10.12788/jcom.0121

7. Sathi K, Huang KTL, Chandler DM, et al. Teaching quality improvement to internal medicine residents to address patient care gaps in ambulatory quality metrics. J Clin Outcome Manag. 2023;30(1):1-6.doi:10.12788/jcom.0119

1. Clancy C, Munier W, Brady J. National healthcare quality report. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013.

2. Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(6):370-376. doi:10.1056/NEJM199102073240604

3. Bates DW, Levine DM, Salmasian H, et al. The safety of inpatient health care. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(2):142-153. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa2206117

4. Bates DW, Cullen DJ, Laird N, et al. Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events: implications for prevention. JAMA. 1995;274(1):29-34.

5. Merchant NB, O’Neal J, Murray JS. Development of a safety awards program at a Veterans Affairs health care system: a quality improvement initiative. J Clin Outcome Manag. 2023;30(1):9-16. doi:10.12788/jcom.0120

6. Goyal A, Martin-Doyle W, Dalal AK. Diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients. J Clin Outcome Manag. 2023;30(1):17-27. doi:10.12788/jcom.0121

7. Sathi K, Huang KTL, Chandler DM, et al. Teaching quality improvement to internal medicine residents to address patient care gaps in ambulatory quality metrics. J Clin Outcome Manag. 2023;30(1):1-6.doi:10.12788/jcom.0119

Best Practice Implementation and Clinical Inertia

From the Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Clinical inertia is defined as the failure of clinicians to initiate or escalate guideline-directed medical therapy to achieve treatment goals for well-defined clinical conditions.1,2 Evidence-based guidelines recommend optimal disease management with readily available medical therapies throughout the phases of clinical care. Unfortunately, the care provided to individual patients undergoes multiple modifications throughout the disease course, resulting in divergent pathways, significant deviations from treatment guidelines, and failure of “safeguard” checkpoints to reinstate, initiate, optimize, or stop treatments. Clinical inertia generally describes rigidity or resistance to change around implementing evidence-based guidelines. Furthermore, this term describes treatment behavior on the part of an individual clinician, not organizational inertia, which generally encompasses both internal (immediate clinical practice settings) and external factors (national and international guidelines and recommendations), eventually leading to resistance to optimizing disease treatment and therapeutic regimens. Individual clinicians’ clinical inertia in the form of resistance to guideline implementation and evidence-based principles can be one factor that drives organizational inertia. In turn, such individual behavior can be dictated by personal beliefs, knowledge, interpretation, skills, management principles, and biases. The terms therapeutic inertia or clinical inertia should not be confused with nonadherence from the patient’s standpoint when the clinician follows the best practice guidelines.3

Clinical inertia has been described in several clinical domains, including diabetes,4,5 hypertension,6,7 heart failure,8 depression,9 pulmonary medicine,10 and complex disease management.11 Clinicians can set suboptimal treatment goals due to specific beliefs and attitudes around optimal therapeutic goals. For example, when treating a patient with a chronic disease that is presently stable, a clinician could elect to initiate suboptimal treatment, as escalation of treatment might not be the priority in stable disease; they also may have concerns about overtreatment. Other factors that can contribute to clinical inertia (ie, undertreatment in the presence of indications for treatment) include those related to the patient, the clinical setting, and the organization, along with the importance of individualizing therapies in specific patients. Organizational inertia is the initial global resistance by the system to implementation, which can slow the dissemination and adaptation of best practices but eventually declines over time. Individual clinical inertia, on the other hand, will likely persist after the system-level rollout of guideline-based approaches.

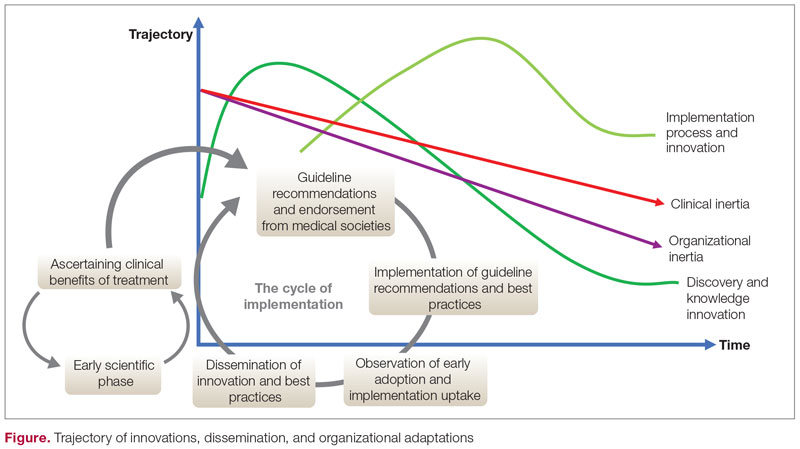

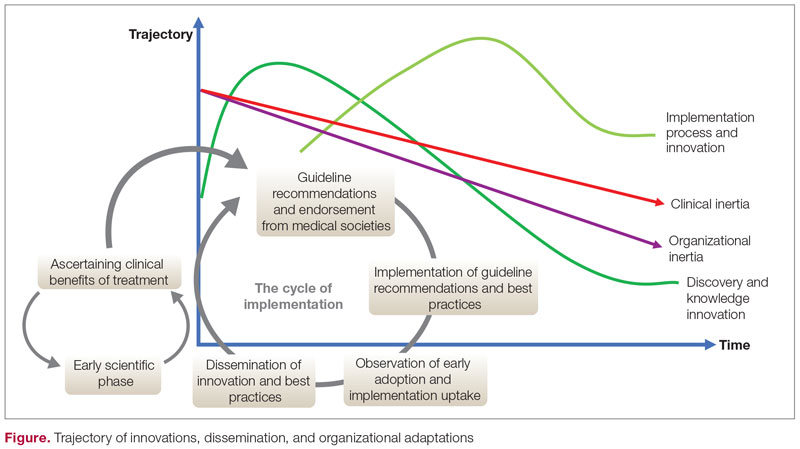

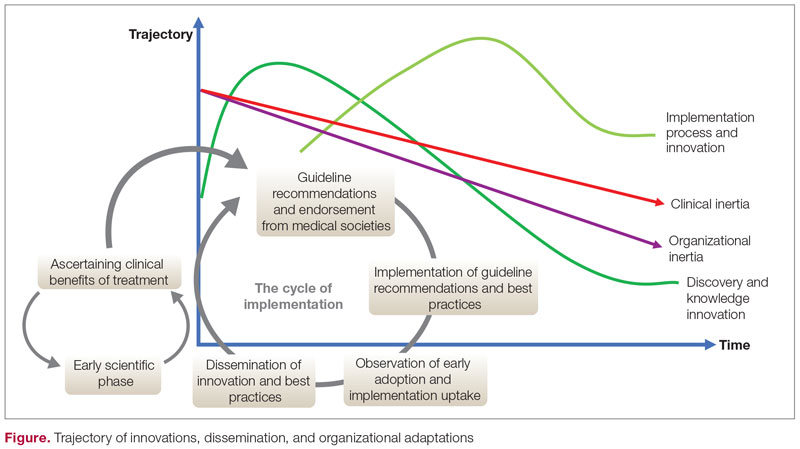

The trajectory of dissemination, implementation, and adaptation of innovations and best practices is illustrated in the Figure. When the guidelines and medical societies endorse the adaptation of innovations or practice change after the benefits of such innovations/change have been established by the regulatory bodies, uptake can be hindered by both organizational and clinical inertia. Overcoming inertia to system-level changes requires addressing individual clinicians, along with practice and organizational factors, in order to ensure systematic adaptations. From the clinicians’ view, training and cognitive interventions to improve the adaptation and coping skills can improve understanding of treatment options through standardized educational and behavioral modification tools, direct and indirect feedback around performance, and decision support through a continuous improvement approach on both individual and system levels.

Addressing inertia in clinical practice requires a deep understanding of the individual and organizational elements that foster resistance to adapting best practice models. Research that explores tools and approaches to overcome inertia in managing complex diseases is a key step in advancing clinical innovation and disseminating best practices.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825-834. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012

2. Allen JD, Curtiss FR, Fairman KA. Nonadherence, clinical inertia, or therapeutic inertia? J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15(8):690-695. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2009.15.8.690

3. Zafar A, Davies M, Azhar A, Khunti K. Clinical inertia in management of T2DM. Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;4(4):203-207. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2010.07.003

4. Khunti K, Davies MJ. Clinical inertia—time to reappraise the terminology? Prim Care Diabetes. 2017;11(2):105-106. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2017.01.007

5. O’Connor PJ. Overcome clinical inertia to control systolic blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(22):2677-2678. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.22.2677

6. Faria C, Wenzel M, Lee KW, et al. A narrative review of clinical inertia: focus on hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2009;3(4):267-276. doi:10.1016/j.jash.2009.03.001

7. Jarjour M, Henri C, de Denus S, et al. Care gaps in adherence to heart failure guidelines: clinical inertia or physiological limitations? JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8(9):725-738. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2020.04.019

8. Henke RM, Zaslavsky AM, McGuire TG, et al. Clinical inertia in depression treatment. Med Care. 2009;47(9):959-67. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5da0

9. Cooke CE, Sidel M, Belletti DA, Fuhlbrigge AL. Clinical inertia in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD. 2012;9(1):73-80. doi:10.3109/15412555.2011.631957

10. Whitford DL, Al-Anjawi HA, Al-Baharna MM. Impact of clinical inertia on cardiovascular risk factors in patients with diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2014;8(2):133-138. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2013.10.007

From the Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Clinical inertia is defined as the failure of clinicians to initiate or escalate guideline-directed medical therapy to achieve treatment goals for well-defined clinical conditions.1,2 Evidence-based guidelines recommend optimal disease management with readily available medical therapies throughout the phases of clinical care. Unfortunately, the care provided to individual patients undergoes multiple modifications throughout the disease course, resulting in divergent pathways, significant deviations from treatment guidelines, and failure of “safeguard” checkpoints to reinstate, initiate, optimize, or stop treatments. Clinical inertia generally describes rigidity or resistance to change around implementing evidence-based guidelines. Furthermore, this term describes treatment behavior on the part of an individual clinician, not organizational inertia, which generally encompasses both internal (immediate clinical practice settings) and external factors (national and international guidelines and recommendations), eventually leading to resistance to optimizing disease treatment and therapeutic regimens. Individual clinicians’ clinical inertia in the form of resistance to guideline implementation and evidence-based principles can be one factor that drives organizational inertia. In turn, such individual behavior can be dictated by personal beliefs, knowledge, interpretation, skills, management principles, and biases. The terms therapeutic inertia or clinical inertia should not be confused with nonadherence from the patient’s standpoint when the clinician follows the best practice guidelines.3

Clinical inertia has been described in several clinical domains, including diabetes,4,5 hypertension,6,7 heart failure,8 depression,9 pulmonary medicine,10 and complex disease management.11 Clinicians can set suboptimal treatment goals due to specific beliefs and attitudes around optimal therapeutic goals. For example, when treating a patient with a chronic disease that is presently stable, a clinician could elect to initiate suboptimal treatment, as escalation of treatment might not be the priority in stable disease; they also may have concerns about overtreatment. Other factors that can contribute to clinical inertia (ie, undertreatment in the presence of indications for treatment) include those related to the patient, the clinical setting, and the organization, along with the importance of individualizing therapies in specific patients. Organizational inertia is the initial global resistance by the system to implementation, which can slow the dissemination and adaptation of best practices but eventually declines over time. Individual clinical inertia, on the other hand, will likely persist after the system-level rollout of guideline-based approaches.

The trajectory of dissemination, implementation, and adaptation of innovations and best practices is illustrated in the Figure. When the guidelines and medical societies endorse the adaptation of innovations or practice change after the benefits of such innovations/change have been established by the regulatory bodies, uptake can be hindered by both organizational and clinical inertia. Overcoming inertia to system-level changes requires addressing individual clinicians, along with practice and organizational factors, in order to ensure systematic adaptations. From the clinicians’ view, training and cognitive interventions to improve the adaptation and coping skills can improve understanding of treatment options through standardized educational and behavioral modification tools, direct and indirect feedback around performance, and decision support through a continuous improvement approach on both individual and system levels.

Addressing inertia in clinical practice requires a deep understanding of the individual and organizational elements that foster resistance to adapting best practice models. Research that explores tools and approaches to overcome inertia in managing complex diseases is a key step in advancing clinical innovation and disseminating best practices.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

Disclosures: None reported.

From the Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Clinical inertia is defined as the failure of clinicians to initiate or escalate guideline-directed medical therapy to achieve treatment goals for well-defined clinical conditions.1,2 Evidence-based guidelines recommend optimal disease management with readily available medical therapies throughout the phases of clinical care. Unfortunately, the care provided to individual patients undergoes multiple modifications throughout the disease course, resulting in divergent pathways, significant deviations from treatment guidelines, and failure of “safeguard” checkpoints to reinstate, initiate, optimize, or stop treatments. Clinical inertia generally describes rigidity or resistance to change around implementing evidence-based guidelines. Furthermore, this term describes treatment behavior on the part of an individual clinician, not organizational inertia, which generally encompasses both internal (immediate clinical practice settings) and external factors (national and international guidelines and recommendations), eventually leading to resistance to optimizing disease treatment and therapeutic regimens. Individual clinicians’ clinical inertia in the form of resistance to guideline implementation and evidence-based principles can be one factor that drives organizational inertia. In turn, such individual behavior can be dictated by personal beliefs, knowledge, interpretation, skills, management principles, and biases. The terms therapeutic inertia or clinical inertia should not be confused with nonadherence from the patient’s standpoint when the clinician follows the best practice guidelines.3

Clinical inertia has been described in several clinical domains, including diabetes,4,5 hypertension,6,7 heart failure,8 depression,9 pulmonary medicine,10 and complex disease management.11 Clinicians can set suboptimal treatment goals due to specific beliefs and attitudes around optimal therapeutic goals. For example, when treating a patient with a chronic disease that is presently stable, a clinician could elect to initiate suboptimal treatment, as escalation of treatment might not be the priority in stable disease; they also may have concerns about overtreatment. Other factors that can contribute to clinical inertia (ie, undertreatment in the presence of indications for treatment) include those related to the patient, the clinical setting, and the organization, along with the importance of individualizing therapies in specific patients. Organizational inertia is the initial global resistance by the system to implementation, which can slow the dissemination and adaptation of best practices but eventually declines over time. Individual clinical inertia, on the other hand, will likely persist after the system-level rollout of guideline-based approaches.

The trajectory of dissemination, implementation, and adaptation of innovations and best practices is illustrated in the Figure. When the guidelines and medical societies endorse the adaptation of innovations or practice change after the benefits of such innovations/change have been established by the regulatory bodies, uptake can be hindered by both organizational and clinical inertia. Overcoming inertia to system-level changes requires addressing individual clinicians, along with practice and organizational factors, in order to ensure systematic adaptations. From the clinicians’ view, training and cognitive interventions to improve the adaptation and coping skills can improve understanding of treatment options through standardized educational and behavioral modification tools, direct and indirect feedback around performance, and decision support through a continuous improvement approach on both individual and system levels.

Addressing inertia in clinical practice requires a deep understanding of the individual and organizational elements that foster resistance to adapting best practice models. Research that explores tools and approaches to overcome inertia in managing complex diseases is a key step in advancing clinical innovation and disseminating best practices.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825-834. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012

2. Allen JD, Curtiss FR, Fairman KA. Nonadherence, clinical inertia, or therapeutic inertia? J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15(8):690-695. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2009.15.8.690

3. Zafar A, Davies M, Azhar A, Khunti K. Clinical inertia in management of T2DM. Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;4(4):203-207. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2010.07.003

4. Khunti K, Davies MJ. Clinical inertia—time to reappraise the terminology? Prim Care Diabetes. 2017;11(2):105-106. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2017.01.007

5. O’Connor PJ. Overcome clinical inertia to control systolic blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(22):2677-2678. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.22.2677

6. Faria C, Wenzel M, Lee KW, et al. A narrative review of clinical inertia: focus on hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2009;3(4):267-276. doi:10.1016/j.jash.2009.03.001

7. Jarjour M, Henri C, de Denus S, et al. Care gaps in adherence to heart failure guidelines: clinical inertia or physiological limitations? JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8(9):725-738. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2020.04.019

8. Henke RM, Zaslavsky AM, McGuire TG, et al. Clinical inertia in depression treatment. Med Care. 2009;47(9):959-67. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5da0

9. Cooke CE, Sidel M, Belletti DA, Fuhlbrigge AL. Clinical inertia in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD. 2012;9(1):73-80. doi:10.3109/15412555.2011.631957

10. Whitford DL, Al-Anjawi HA, Al-Baharna MM. Impact of clinical inertia on cardiovascular risk factors in patients with diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2014;8(2):133-138. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2013.10.007

1. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825-834. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012

2. Allen JD, Curtiss FR, Fairman KA. Nonadherence, clinical inertia, or therapeutic inertia? J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15(8):690-695. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2009.15.8.690

3. Zafar A, Davies M, Azhar A, Khunti K. Clinical inertia in management of T2DM. Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;4(4):203-207. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2010.07.003

4. Khunti K, Davies MJ. Clinical inertia—time to reappraise the terminology? Prim Care Diabetes. 2017;11(2):105-106. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2017.01.007

5. O’Connor PJ. Overcome clinical inertia to control systolic blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(22):2677-2678. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.22.2677

6. Faria C, Wenzel M, Lee KW, et al. A narrative review of clinical inertia: focus on hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2009;3(4):267-276. doi:10.1016/j.jash.2009.03.001

7. Jarjour M, Henri C, de Denus S, et al. Care gaps in adherence to heart failure guidelines: clinical inertia or physiological limitations? JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8(9):725-738. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2020.04.019

8. Henke RM, Zaslavsky AM, McGuire TG, et al. Clinical inertia in depression treatment. Med Care. 2009;47(9):959-67. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5da0

9. Cooke CE, Sidel M, Belletti DA, Fuhlbrigge AL. Clinical inertia in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD. 2012;9(1):73-80. doi:10.3109/15412555.2011.631957

10. Whitford DL, Al-Anjawi HA, Al-Baharna MM. Impact of clinical inertia on cardiovascular risk factors in patients with diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2014;8(2):133-138. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2013.10.007

Barriers to System Quality Improvement in Health Care

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

Process improvement in any industry sector aims to increase the efficiency of resource utilization and delivery methods (cost) and the quality of the product (outcomes), with the goal of ultimately achieving continuous development.1 In the health care industry, variation in processes and outcomes along with inefficiency in resource use that result in changes in value (the product of outcomes/costs) are the general targets of quality improvement (QI) efforts employing various implementation methodologies.2 When the ultimate aim is to serve the patient (customer), best clinical practice includes both maintaining high quality (individual care delivery) and controlling costs (efficient care system delivery), leading to optimal delivery (value-based care). High-quality individual care and efficient care delivery are not competing concepts, but when working to improve both health care outcomes and cost, traditional and nontraditional barriers to system QI often arise.3

The possible scenarios after a QI intervention include backsliding (regression to the mean over time), steady-state (minimal fixed improvement that could sustain), and continuous improvement (tangible enhancement after completing the intervention with legacy effect).4 The scalability of results can be considered during the process measurement and the intervention design phases of all QI projects; however, the complex nature of barriers in the health care environment during each level of implementation should be accounted for to prevent failure in the scalability phase.5

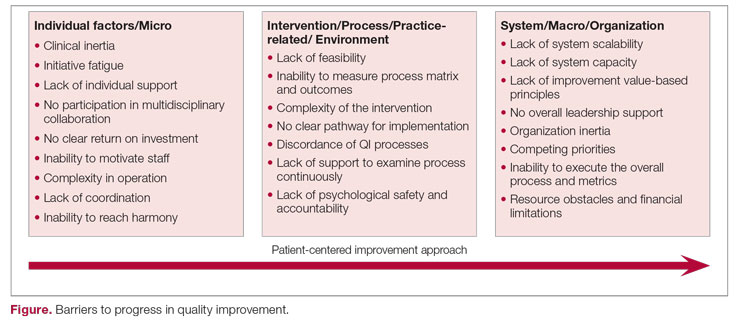

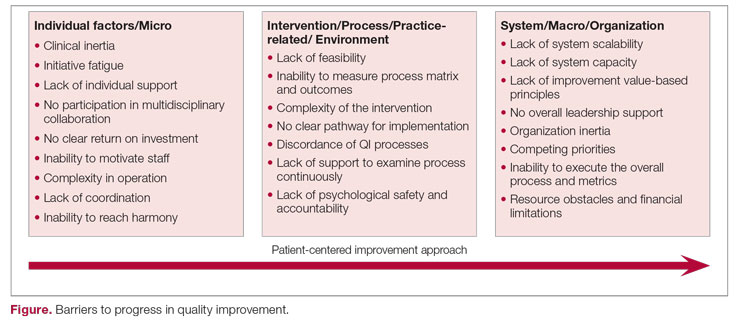

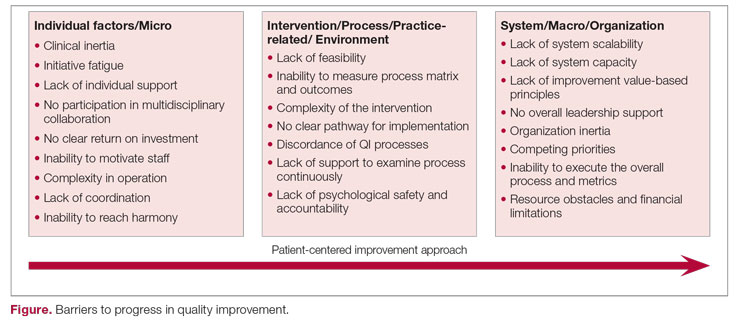

The barriers to optimal QI outcomes leading to continuous improvement are multifactorial and are related to intrinsic and extrinsic factors.6 These factors include 3 fundamental levels: (1) individual level inertia/beliefs, prior personal knowledge, and team-related factors7,8; (2) intervention-related and process-specific barriers and clinical practice obstacles; and (3) organizational level challenges and macro-level and population-level barriers (Figure). The obstacles faced during the implementation phase will likely include 2 of these levels simultaneously, which could add complexity and hinder or prevent the implementation of a tangible successful QI process and eventually lead to backsliding or minimal fixed improvement rather than continuous improvement. Furthermore, a patient-centered approach to QI would contribute to further complexity in design and execution, given the importance of reaching sustainable, meaningful improvement by adding elements of patient’s preferences, caregiver engagement, and the shared decision-making processes.9

Overcoming these multidomain barriers and reaching resilience and sustainability requires thoughtful planning and execution through a multifaceted approach.10 A meaningful start could include addressing the clinical inertia for the individual and the team by promoting open innovation and allowing outside institutional collaborations and ideas through networks.11 On the individual level, encouraging participation and motivating health care workers in QI to reach a multidisciplinary operation approach will lead to harmony in collaboration. Concurrently, the organization should support the QI capability and scalability by removing competing priorities and establishing effective leadership that ensures resource allocation, communicates clear value-based principles, and engenders a psychological safety environment.

A continuous improvement state is the optimal QI target, a target that can be attained by removing obstacles and paving a clear pathway to implementation. Focusing on the 3 levels of barriers will position the organization for meaningful and successful QI phases to achieve continuous improvement.

1. Adesola S, Baines T. Developing and evaluating a methodology for business process improvement. Business Process Manage J. 2005;11(1):37-46. doi:10.1108/14637150510578719

2. Gershon M. Choosing which process improvement methodology to implement. J Appl Business & Economics. 2010;10(5):61-69.

3. Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results. Harvard Business Press; 2006.

4. Holweg M, Davies J, De Meyer A, Lawson B, Schmenner RW. Process Theory: The Principles of Operations Management. Oxford University Press; 2018.

5. Shortell SM, Bennett CL, Byck GR. Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement on clinical practice: what it will take to accelerate progress. Milbank Q. 1998;76(4):593-624. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.00107

6. Solomons NM, Spross JA. Evidence‐based practice barriers and facilitators from a continuous quality improvement perspective: an integrative review. J Nurs Manage. 2011;19(1):109-120. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01144.x

7. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825-34. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012

8. Stevenson K, Baker R, Farooqi A, Sorrie R, Khunti K. Features of primary health care teams associated with successful quality improvement of diabetes care: a qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2001;18(1):21-26. doi:10.1093/fampra/18.1.21

9. What is patient-centered care? NEJM Catalyst. January 1, 2017. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.17.0559

10. Kilbourne AM, Beck K, Spaeth‐Rublee B, et al. Measuring and improving the quality of mental health care: a global perspective. World Psychiatry. 2018;17(1):30-8. doi:10.1002/wps.20482

11. Huang HC, Lai MC, Lin LH, Chen CT. Overcoming organizational inertia to strengthen business model innovation: An open innovation perspective. J Organizational Change Manage. 2013;26(6):977-1002. doi:10.1108/JOCM-04-2012-0047

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

Process improvement in any industry sector aims to increase the efficiency of resource utilization and delivery methods (cost) and the quality of the product (outcomes), with the goal of ultimately achieving continuous development.1 In the health care industry, variation in processes and outcomes along with inefficiency in resource use that result in changes in value (the product of outcomes/costs) are the general targets of quality improvement (QI) efforts employing various implementation methodologies.2 When the ultimate aim is to serve the patient (customer), best clinical practice includes both maintaining high quality (individual care delivery) and controlling costs (efficient care system delivery), leading to optimal delivery (value-based care). High-quality individual care and efficient care delivery are not competing concepts, but when working to improve both health care outcomes and cost, traditional and nontraditional barriers to system QI often arise.3

The possible scenarios after a QI intervention include backsliding (regression to the mean over time), steady-state (minimal fixed improvement that could sustain), and continuous improvement (tangible enhancement after completing the intervention with legacy effect).4 The scalability of results can be considered during the process measurement and the intervention design phases of all QI projects; however, the complex nature of barriers in the health care environment during each level of implementation should be accounted for to prevent failure in the scalability phase.5

The barriers to optimal QI outcomes leading to continuous improvement are multifactorial and are related to intrinsic and extrinsic factors.6 These factors include 3 fundamental levels: (1) individual level inertia/beliefs, prior personal knowledge, and team-related factors7,8; (2) intervention-related and process-specific barriers and clinical practice obstacles; and (3) organizational level challenges and macro-level and population-level barriers (Figure). The obstacles faced during the implementation phase will likely include 2 of these levels simultaneously, which could add complexity and hinder or prevent the implementation of a tangible successful QI process and eventually lead to backsliding or minimal fixed improvement rather than continuous improvement. Furthermore, a patient-centered approach to QI would contribute to further complexity in design and execution, given the importance of reaching sustainable, meaningful improvement by adding elements of patient’s preferences, caregiver engagement, and the shared decision-making processes.9

Overcoming these multidomain barriers and reaching resilience and sustainability requires thoughtful planning and execution through a multifaceted approach.10 A meaningful start could include addressing the clinical inertia for the individual and the team by promoting open innovation and allowing outside institutional collaborations and ideas through networks.11 On the individual level, encouraging participation and motivating health care workers in QI to reach a multidisciplinary operation approach will lead to harmony in collaboration. Concurrently, the organization should support the QI capability and scalability by removing competing priorities and establishing effective leadership that ensures resource allocation, communicates clear value-based principles, and engenders a psychological safety environment.

A continuous improvement state is the optimal QI target, a target that can be attained by removing obstacles and paving a clear pathway to implementation. Focusing on the 3 levels of barriers will position the organization for meaningful and successful QI phases to achieve continuous improvement.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

Process improvement in any industry sector aims to increase the efficiency of resource utilization and delivery methods (cost) and the quality of the product (outcomes), with the goal of ultimately achieving continuous development.1 In the health care industry, variation in processes and outcomes along with inefficiency in resource use that result in changes in value (the product of outcomes/costs) are the general targets of quality improvement (QI) efforts employing various implementation methodologies.2 When the ultimate aim is to serve the patient (customer), best clinical practice includes both maintaining high quality (individual care delivery) and controlling costs (efficient care system delivery), leading to optimal delivery (value-based care). High-quality individual care and efficient care delivery are not competing concepts, but when working to improve both health care outcomes and cost, traditional and nontraditional barriers to system QI often arise.3

The possible scenarios after a QI intervention include backsliding (regression to the mean over time), steady-state (minimal fixed improvement that could sustain), and continuous improvement (tangible enhancement after completing the intervention with legacy effect).4 The scalability of results can be considered during the process measurement and the intervention design phases of all QI projects; however, the complex nature of barriers in the health care environment during each level of implementation should be accounted for to prevent failure in the scalability phase.5

The barriers to optimal QI outcomes leading to continuous improvement are multifactorial and are related to intrinsic and extrinsic factors.6 These factors include 3 fundamental levels: (1) individual level inertia/beliefs, prior personal knowledge, and team-related factors7,8; (2) intervention-related and process-specific barriers and clinical practice obstacles; and (3) organizational level challenges and macro-level and population-level barriers (Figure). The obstacles faced during the implementation phase will likely include 2 of these levels simultaneously, which could add complexity and hinder or prevent the implementation of a tangible successful QI process and eventually lead to backsliding or minimal fixed improvement rather than continuous improvement. Furthermore, a patient-centered approach to QI would contribute to further complexity in design and execution, given the importance of reaching sustainable, meaningful improvement by adding elements of patient’s preferences, caregiver engagement, and the shared decision-making processes.9

Overcoming these multidomain barriers and reaching resilience and sustainability requires thoughtful planning and execution through a multifaceted approach.10 A meaningful start could include addressing the clinical inertia for the individual and the team by promoting open innovation and allowing outside institutional collaborations and ideas through networks.11 On the individual level, encouraging participation and motivating health care workers in QI to reach a multidisciplinary operation approach will lead to harmony in collaboration. Concurrently, the organization should support the QI capability and scalability by removing competing priorities and establishing effective leadership that ensures resource allocation, communicates clear value-based principles, and engenders a psychological safety environment.

A continuous improvement state is the optimal QI target, a target that can be attained by removing obstacles and paving a clear pathway to implementation. Focusing on the 3 levels of barriers will position the organization for meaningful and successful QI phases to achieve continuous improvement.

1. Adesola S, Baines T. Developing and evaluating a methodology for business process improvement. Business Process Manage J. 2005;11(1):37-46. doi:10.1108/14637150510578719

2. Gershon M. Choosing which process improvement methodology to implement. J Appl Business & Economics. 2010;10(5):61-69.

3. Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results. Harvard Business Press; 2006.

4. Holweg M, Davies J, De Meyer A, Lawson B, Schmenner RW. Process Theory: The Principles of Operations Management. Oxford University Press; 2018.

5. Shortell SM, Bennett CL, Byck GR. Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement on clinical practice: what it will take to accelerate progress. Milbank Q. 1998;76(4):593-624. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.00107

6. Solomons NM, Spross JA. Evidence‐based practice barriers and facilitators from a continuous quality improvement perspective: an integrative review. J Nurs Manage. 2011;19(1):109-120. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01144.x

7. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825-34. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012

8. Stevenson K, Baker R, Farooqi A, Sorrie R, Khunti K. Features of primary health care teams associated with successful quality improvement of diabetes care: a qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2001;18(1):21-26. doi:10.1093/fampra/18.1.21