User login

From the Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Clinical inertia is defined as the failure of clinicians to initiate or escalate guideline-directed medical therapy to achieve treatment goals for well-defined clinical conditions.1,2 Evidence-based guidelines recommend optimal disease management with readily available medical therapies throughout the phases of clinical care. Unfortunately, the care provided to individual patients undergoes multiple modifications throughout the disease course, resulting in divergent pathways, significant deviations from treatment guidelines, and failure of “safeguard” checkpoints to reinstate, initiate, optimize, or stop treatments. Clinical inertia generally describes rigidity or resistance to change around implementing evidence-based guidelines. Furthermore, this term describes treatment behavior on the part of an individual clinician, not organizational inertia, which generally encompasses both internal (immediate clinical practice settings) and external factors (national and international guidelines and recommendations), eventually leading to resistance to optimizing disease treatment and therapeutic regimens. Individual clinicians’ clinical inertia in the form of resistance to guideline implementation and evidence-based principles can be one factor that drives organizational inertia. In turn, such individual behavior can be dictated by personal beliefs, knowledge, interpretation, skills, management principles, and biases. The terms therapeutic inertia or clinical inertia should not be confused with nonadherence from the patient’s standpoint when the clinician follows the best practice guidelines.3

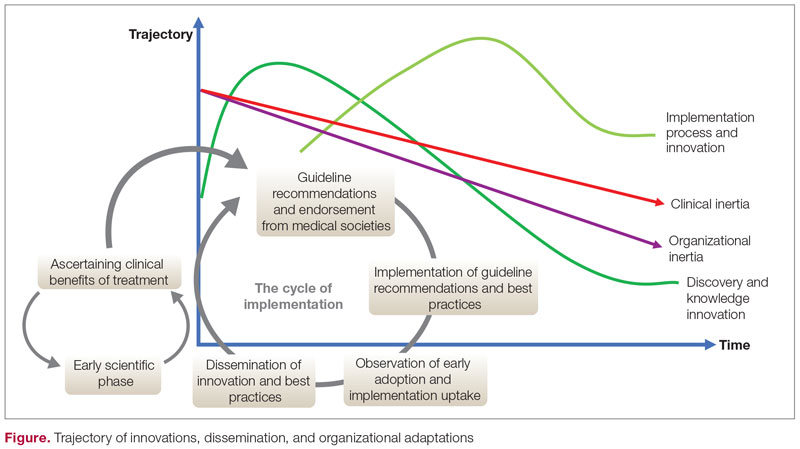

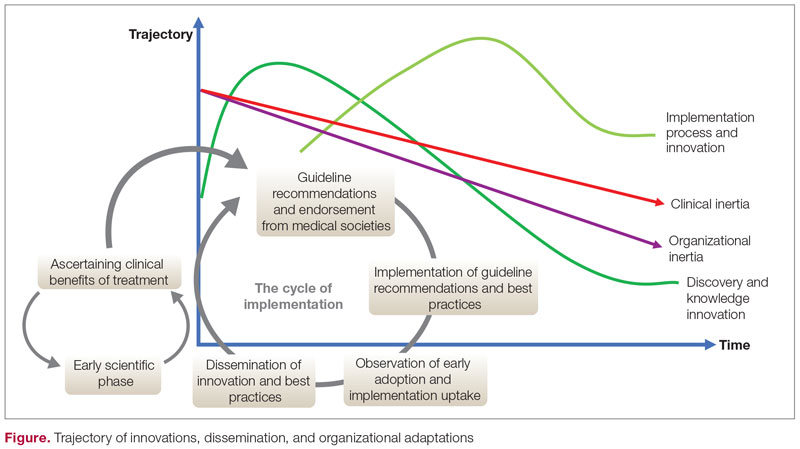

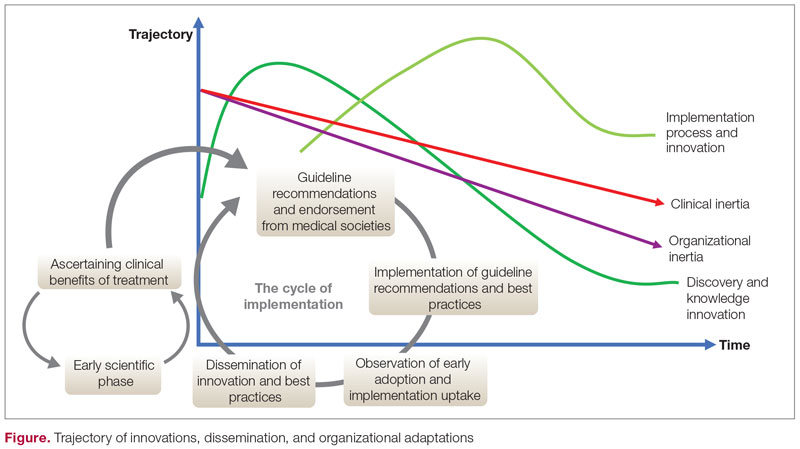

Clinical inertia has been described in several clinical domains, including diabetes,4,5 hypertension,6,7 heart failure,8 depression,9 pulmonary medicine,10 and complex disease management.11 Clinicians can set suboptimal treatment goals due to specific beliefs and attitudes around optimal therapeutic goals. For example, when treating a patient with a chronic disease that is presently stable, a clinician could elect to initiate suboptimal treatment, as escalation of treatment might not be the priority in stable disease; they also may have concerns about overtreatment. Other factors that can contribute to clinical inertia (ie, undertreatment in the presence of indications for treatment) include those related to the patient, the clinical setting, and the organization, along with the importance of individualizing therapies in specific patients. Organizational inertia is the initial global resistance by the system to implementation, which can slow the dissemination and adaptation of best practices but eventually declines over time. Individual clinical inertia, on the other hand, will likely persist after the system-level rollout of guideline-based approaches.

The trajectory of dissemination, implementation, and adaptation of innovations and best practices is illustrated in the Figure. When the guidelines and medical societies endorse the adaptation of innovations or practice change after the benefits of such innovations/change have been established by the regulatory bodies, uptake can be hindered by both organizational and clinical inertia. Overcoming inertia to system-level changes requires addressing individual clinicians, along with practice and organizational factors, in order to ensure systematic adaptations. From the clinicians’ view, training and cognitive interventions to improve the adaptation and coping skills can improve understanding of treatment options through standardized educational and behavioral modification tools, direct and indirect feedback around performance, and decision support through a continuous improvement approach on both individual and system levels.

Addressing inertia in clinical practice requires a deep understanding of the individual and organizational elements that foster resistance to adapting best practice models. Research that explores tools and approaches to overcome inertia in managing complex diseases is a key step in advancing clinical innovation and disseminating best practices.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825-834. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012

2. Allen JD, Curtiss FR, Fairman KA. Nonadherence, clinical inertia, or therapeutic inertia? J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15(8):690-695. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2009.15.8.690

3. Zafar A, Davies M, Azhar A, Khunti K. Clinical inertia in management of T2DM. Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;4(4):203-207. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2010.07.003

4. Khunti K, Davies MJ. Clinical inertia—time to reappraise the terminology? Prim Care Diabetes. 2017;11(2):105-106. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2017.01.007

5. O’Connor PJ. Overcome clinical inertia to control systolic blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(22):2677-2678. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.22.2677

6. Faria C, Wenzel M, Lee KW, et al. A narrative review of clinical inertia: focus on hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2009;3(4):267-276. doi:10.1016/j.jash.2009.03.001

7. Jarjour M, Henri C, de Denus S, et al. Care gaps in adherence to heart failure guidelines: clinical inertia or physiological limitations? JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8(9):725-738. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2020.04.019

8. Henke RM, Zaslavsky AM, McGuire TG, et al. Clinical inertia in depression treatment. Med Care. 2009;47(9):959-67. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5da0

9. Cooke CE, Sidel M, Belletti DA, Fuhlbrigge AL. Clinical inertia in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD. 2012;9(1):73-80. doi:10.3109/15412555.2011.631957

10. Whitford DL, Al-Anjawi HA, Al-Baharna MM. Impact of clinical inertia on cardiovascular risk factors in patients with diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2014;8(2):133-138. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2013.10.007

From the Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Clinical inertia is defined as the failure of clinicians to initiate or escalate guideline-directed medical therapy to achieve treatment goals for well-defined clinical conditions.1,2 Evidence-based guidelines recommend optimal disease management with readily available medical therapies throughout the phases of clinical care. Unfortunately, the care provided to individual patients undergoes multiple modifications throughout the disease course, resulting in divergent pathways, significant deviations from treatment guidelines, and failure of “safeguard” checkpoints to reinstate, initiate, optimize, or stop treatments. Clinical inertia generally describes rigidity or resistance to change around implementing evidence-based guidelines. Furthermore, this term describes treatment behavior on the part of an individual clinician, not organizational inertia, which generally encompasses both internal (immediate clinical practice settings) and external factors (national and international guidelines and recommendations), eventually leading to resistance to optimizing disease treatment and therapeutic regimens. Individual clinicians’ clinical inertia in the form of resistance to guideline implementation and evidence-based principles can be one factor that drives organizational inertia. In turn, such individual behavior can be dictated by personal beliefs, knowledge, interpretation, skills, management principles, and biases. The terms therapeutic inertia or clinical inertia should not be confused with nonadherence from the patient’s standpoint when the clinician follows the best practice guidelines.3

Clinical inertia has been described in several clinical domains, including diabetes,4,5 hypertension,6,7 heart failure,8 depression,9 pulmonary medicine,10 and complex disease management.11 Clinicians can set suboptimal treatment goals due to specific beliefs and attitudes around optimal therapeutic goals. For example, when treating a patient with a chronic disease that is presently stable, a clinician could elect to initiate suboptimal treatment, as escalation of treatment might not be the priority in stable disease; they also may have concerns about overtreatment. Other factors that can contribute to clinical inertia (ie, undertreatment in the presence of indications for treatment) include those related to the patient, the clinical setting, and the organization, along with the importance of individualizing therapies in specific patients. Organizational inertia is the initial global resistance by the system to implementation, which can slow the dissemination and adaptation of best practices but eventually declines over time. Individual clinical inertia, on the other hand, will likely persist after the system-level rollout of guideline-based approaches.

The trajectory of dissemination, implementation, and adaptation of innovations and best practices is illustrated in the Figure. When the guidelines and medical societies endorse the adaptation of innovations or practice change after the benefits of such innovations/change have been established by the regulatory bodies, uptake can be hindered by both organizational and clinical inertia. Overcoming inertia to system-level changes requires addressing individual clinicians, along with practice and organizational factors, in order to ensure systematic adaptations. From the clinicians’ view, training and cognitive interventions to improve the adaptation and coping skills can improve understanding of treatment options through standardized educational and behavioral modification tools, direct and indirect feedback around performance, and decision support through a continuous improvement approach on both individual and system levels.

Addressing inertia in clinical practice requires a deep understanding of the individual and organizational elements that foster resistance to adapting best practice models. Research that explores tools and approaches to overcome inertia in managing complex diseases is a key step in advancing clinical innovation and disseminating best practices.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

Disclosures: None reported.

From the Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Clinical inertia is defined as the failure of clinicians to initiate or escalate guideline-directed medical therapy to achieve treatment goals for well-defined clinical conditions.1,2 Evidence-based guidelines recommend optimal disease management with readily available medical therapies throughout the phases of clinical care. Unfortunately, the care provided to individual patients undergoes multiple modifications throughout the disease course, resulting in divergent pathways, significant deviations from treatment guidelines, and failure of “safeguard” checkpoints to reinstate, initiate, optimize, or stop treatments. Clinical inertia generally describes rigidity or resistance to change around implementing evidence-based guidelines. Furthermore, this term describes treatment behavior on the part of an individual clinician, not organizational inertia, which generally encompasses both internal (immediate clinical practice settings) and external factors (national and international guidelines and recommendations), eventually leading to resistance to optimizing disease treatment and therapeutic regimens. Individual clinicians’ clinical inertia in the form of resistance to guideline implementation and evidence-based principles can be one factor that drives organizational inertia. In turn, such individual behavior can be dictated by personal beliefs, knowledge, interpretation, skills, management principles, and biases. The terms therapeutic inertia or clinical inertia should not be confused with nonadherence from the patient’s standpoint when the clinician follows the best practice guidelines.3

Clinical inertia has been described in several clinical domains, including diabetes,4,5 hypertension,6,7 heart failure,8 depression,9 pulmonary medicine,10 and complex disease management.11 Clinicians can set suboptimal treatment goals due to specific beliefs and attitudes around optimal therapeutic goals. For example, when treating a patient with a chronic disease that is presently stable, a clinician could elect to initiate suboptimal treatment, as escalation of treatment might not be the priority in stable disease; they also may have concerns about overtreatment. Other factors that can contribute to clinical inertia (ie, undertreatment in the presence of indications for treatment) include those related to the patient, the clinical setting, and the organization, along with the importance of individualizing therapies in specific patients. Organizational inertia is the initial global resistance by the system to implementation, which can slow the dissemination and adaptation of best practices but eventually declines over time. Individual clinical inertia, on the other hand, will likely persist after the system-level rollout of guideline-based approaches.

The trajectory of dissemination, implementation, and adaptation of innovations and best practices is illustrated in the Figure. When the guidelines and medical societies endorse the adaptation of innovations or practice change after the benefits of such innovations/change have been established by the regulatory bodies, uptake can be hindered by both organizational and clinical inertia. Overcoming inertia to system-level changes requires addressing individual clinicians, along with practice and organizational factors, in order to ensure systematic adaptations. From the clinicians’ view, training and cognitive interventions to improve the adaptation and coping skills can improve understanding of treatment options through standardized educational and behavioral modification tools, direct and indirect feedback around performance, and decision support through a continuous improvement approach on both individual and system levels.

Addressing inertia in clinical practice requires a deep understanding of the individual and organizational elements that foster resistance to adapting best practice models. Research that explores tools and approaches to overcome inertia in managing complex diseases is a key step in advancing clinical innovation and disseminating best practices.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825-834. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012

2. Allen JD, Curtiss FR, Fairman KA. Nonadherence, clinical inertia, or therapeutic inertia? J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15(8):690-695. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2009.15.8.690

3. Zafar A, Davies M, Azhar A, Khunti K. Clinical inertia in management of T2DM. Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;4(4):203-207. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2010.07.003

4. Khunti K, Davies MJ. Clinical inertia—time to reappraise the terminology? Prim Care Diabetes. 2017;11(2):105-106. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2017.01.007

5. O’Connor PJ. Overcome clinical inertia to control systolic blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(22):2677-2678. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.22.2677

6. Faria C, Wenzel M, Lee KW, et al. A narrative review of clinical inertia: focus on hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2009;3(4):267-276. doi:10.1016/j.jash.2009.03.001

7. Jarjour M, Henri C, de Denus S, et al. Care gaps in adherence to heart failure guidelines: clinical inertia or physiological limitations? JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8(9):725-738. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2020.04.019

8. Henke RM, Zaslavsky AM, McGuire TG, et al. Clinical inertia in depression treatment. Med Care. 2009;47(9):959-67. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5da0

9. Cooke CE, Sidel M, Belletti DA, Fuhlbrigge AL. Clinical inertia in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD. 2012;9(1):73-80. doi:10.3109/15412555.2011.631957

10. Whitford DL, Al-Anjawi HA, Al-Baharna MM. Impact of clinical inertia on cardiovascular risk factors in patients with diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2014;8(2):133-138. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2013.10.007

1. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825-834. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012

2. Allen JD, Curtiss FR, Fairman KA. Nonadherence, clinical inertia, or therapeutic inertia? J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15(8):690-695. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2009.15.8.690

3. Zafar A, Davies M, Azhar A, Khunti K. Clinical inertia in management of T2DM. Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;4(4):203-207. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2010.07.003

4. Khunti K, Davies MJ. Clinical inertia—time to reappraise the terminology? Prim Care Diabetes. 2017;11(2):105-106. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2017.01.007

5. O’Connor PJ. Overcome clinical inertia to control systolic blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(22):2677-2678. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.22.2677

6. Faria C, Wenzel M, Lee KW, et al. A narrative review of clinical inertia: focus on hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2009;3(4):267-276. doi:10.1016/j.jash.2009.03.001

7. Jarjour M, Henri C, de Denus S, et al. Care gaps in adherence to heart failure guidelines: clinical inertia or physiological limitations? JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8(9):725-738. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2020.04.019

8. Henke RM, Zaslavsky AM, McGuire TG, et al. Clinical inertia in depression treatment. Med Care. 2009;47(9):959-67. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5da0

9. Cooke CE, Sidel M, Belletti DA, Fuhlbrigge AL. Clinical inertia in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD. 2012;9(1):73-80. doi:10.3109/15412555.2011.631957

10. Whitford DL, Al-Anjawi HA, Al-Baharna MM. Impact of clinical inertia on cardiovascular risk factors in patients with diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2014;8(2):133-138. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2013.10.007