User login

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

Key Elements of Critical Care

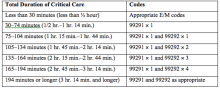

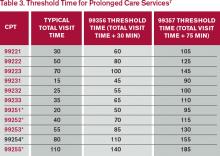

Code 99291 is used for critical care, evaluation, and management of the critically ill or critically injured patient, first 30–74 minutes.1 It is to be reported only once per day per physician or group member of the same specialty.

Code 99292 is for critical care, evaluation, and management of the critically ill or critically injured patient, each additional 30 minutes. It is to be listed separately in addition to the code for primary service.1 Code 99292 is categorized as an add-on code. It must be reported on the same invoice as its primary code, 99291. Multiple units of code 99292 can be reported per day per physician/group.

Despite the increased resources and references for critical care billing, critical care reporting issues persist. Medicare data analysis continues to identify 99291 as high risk for claim payment errors, perpetuating prepayment claim edits for outlier utilization and location discrepancies (i.e., settings other than inpatient hospital, outpatient hospital, or the emergency department). 2,3,4

Bolster your documentation with these three key elements.

Critical Illness, Injury Management

Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) define “critical illness or injury” as a condition that acutely impairs one or more vital organ systems such that there is a high probability of imminent or life-threatening deterioration in the patient’s condition (e.g., central nervous system failure; circulatory failure; shock; renal, hepatic, metabolic, and/or respiratory failure).5

Hospitalists providing care to the critically ill patient must perform highly complex decision making and interventions of high intensity that are required to prevent the patient’s inevitable decline. CMS further elaborates that “the patient shall be critically ill or injured at the time of the physician’s visit.”6 This is to ensure that hospitalists and other specialists support the medical necessity of the service and do not continue to report critical care codes on days after the patient has become stable and improved.

Consider the following scenarios:

CMS examples of patients whose medical condition may warrant critical care services (99291, 99292):6

- An 81-year-old male patient is admitted to the ICU following abdominal aortic aneurysm resection. Two days after surgery, he requires fluids and pressors to maintain adequate perfusion and arterial pressures. He remains ventilator dependent.

- A 67-year-old female patient is three days post mitral valve repair. She develops petechiae, hypotension, and hypoxia requiring respiratory and circulatory support.

- A 70-year-old admitted for right lower lobe pneumococcal pneumonia with a history of COPD becomes hypoxic and hypotensive two days after admission.

- A 68-year-old admitted for an acute anterior wall myocardial infarction continues to have symptomatic ventricular tachycardia that is marginally responsive to antiarrhythmic therapy.

CMS examples of patients who may not satisfy Medicare medical necessity criteria, or do not meet critical care criteria, or who do not have a critical care illness or injury and, therefore, are not eligible for critical care payment but may be reported using another appropriate hospital care code, such as subsequent hospital care codes (99231–99233), initial hospital care codes (99221–99223), or hospital consultation codes (99251–99255) when applicable:1,6

- Patients admitted to a critical care unit because no other hospital beds were available;

- Patients admitted to a critical care unit for close nursing observation and/or frequent monitoring of vital signs (e.g., drug toxicity or overdose);

- Patients admitted to a critical care unit because hospital rules require certain treatments (e.g., insulin infusions) to be administered in the critical care unit; and

- Patients receiving only care of a chronic illness in absence of care for a critical illness (e.g., daily management of a chronic ventilator patient, management of or care related to dialysis for end-stage renal disease). Services considered palliative in nature as this type of care do not meet the definition of critical care services.7

Concurrent Care

Critically ill patients often require the care of hospitalists and other specialists throughout the course of treatment. Payors are sensitive to the multiple hours billed by multiple providers for a single patient on a given day. Claim logic provides an automated response to only allow reimbursement for 99291 once per day when reported by physicians of the same group and specialty.8 Physicians of different specialties can separately report critical care hours as long as they are caring for a condition that meets the definition of critical care.

The CMS example of this: A dermatologist evaluates and treats a rash on an ICU patient who is maintained on a ventilator and nitroglycerine infusion that are being managed by an intensivist. The dermatologist should not report a service for critical care.6

Similarly for hospitalists, if an intensivist is taking care of the critical condition and there is nothing more for the hospitalist to add to the plan of care for the critical condition, critical care services may not be justified.

When different specialists are reporting critical care on the same day, it is imperative for the documentation to demonstrate that care is not duplicative of any other provider’s care (i.e., identify management of different conditions or revising elements of the plan). The care cannot overlap the same time period of any other physician reporting critical care services.

Calculating Time

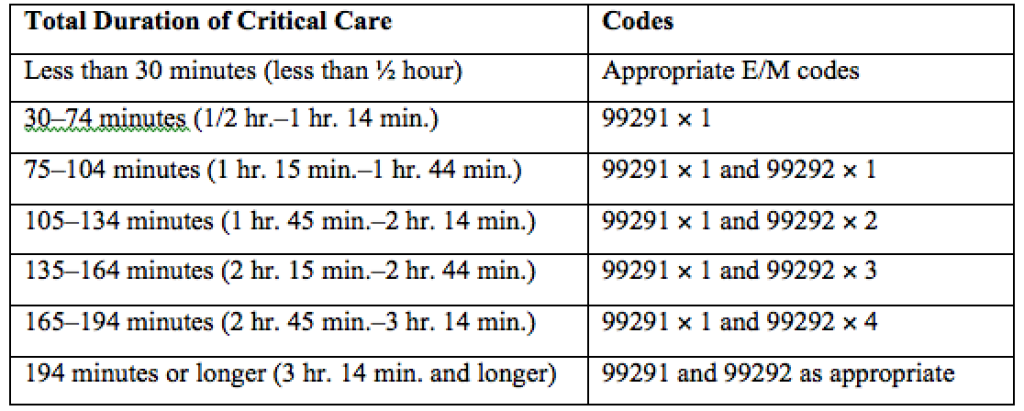

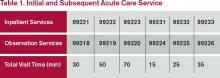

Critical care time constitutes bedside time and time spent on the patient’s unit/floor where the physician is immediately available to the patient (see Table 1). Certain labs, diagnostic studies, and procedures are considered inherent to critical care services and are not reported separately on the claim form: cardiac output measurements (93561, 93562); chest X-rays (71010, 71015, 71020); pulse oximetry (94760, 94761, 94762); blood gases and interpretation of data stored in computers, such as ECGs, blood pressures, and hematologic data (99090); gastric intubation (43752, 43753); temporary transcutaneous pacing (92953); ventilation management (94002–94004, 94660, 94662); and vascular access procedures (36000, 36410, 36415, 36591, 36600).1

Instead, physician time associated with the performance and/or interpretation of these services is toward the cumulative critical care time of the day. Services or procedures that are considered separately billable (e.g., central line placement, intubation, CPR) cannot contribute to critical care time.

When separately billable procedures are performed by the same provider/specialty group on the same day as critical care, physicians should make a notation in the medical record indicating the non-overlapping service times (e.g., “central line insertion is not included as critical care time”). This may assist with securing reimbursement when the payor requests the documentation for each reported claim item.

Activities on the floor/unit that do not directly contribute to patient care or management (e.g., review of literature, teaching rounds) cannot be counted toward critical care time. Do not count time associated with indirect care provided outside of the patient’s unit/floor (e.g., reviewing data or calling the family from the office) toward critical care time.

Family discussions can be counted toward critical care time but must take place at bedside or on the patient’s unit/floor. The patient must participate in the discussion unless medically unable or clinically incompetent to participate. If unable to participate, a notation in the chart must delineate the patient’s inability to participate and the reason.

Credited time can only involve obtaining a medical history and/or discussing treatment options or limitation(s) of treatment. The conversation must bear directly on patient management.1,7 Do not count time associated with providing periodic condition updates to the family, answering questions about the patient’s condition that are unrelated to decision making, or counseling the family during their grief process. If the conversation must take place via phone, it may be counted toward critical care time if the physician is calling from the patient’s unit/floor and the conversation involves the same criterion identified for face-to-face family meetings.10

Physicians should keep track of their critical care time throughout the day. Since critical care time is a cumulative service, each entry should include the total time that critical care services were provided (e.g., 45 minutes).10 Some payors may still impose the notation of “start-and-stop time” per encounter (e.g., 2–2:50 a.m.).

Same-specialty physicians (i.e., two hospitalists from the same group practice) may require separate claims. The initial critical care hour (99291) must be met by a single physician. Medically necessary critical care time beyond the first hour (99292) may be met individually by the same physician or collectively with another physician from the same group. The physician performing the additional time, beyond the first hour, reports the appropriate units of 99292 (see Table 1) under the corresponding NPI.11

CMS has issued instructions for contractors to recognize this atypical reporting method. However, non-Medicare payors may not recognize this newer reporting method and maintain that the cumulative service (by the same-specialty physician in the same provider group) should be reported under one physician name. Be sure to query the payors for appropriate reporting methods. TH

References

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Crosslin, R. Current Procedural Terminology 2015 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2014. 23-25.

- Widespread prepayment targeted review notification—CPT 99291. Cahaba website. Available at: www.cahabagba.com/news/widespread-prepayment-targeted-review-notification-part-b/. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Critical care CPT 99291 widespread prepayment targeted review results. Cahaba website. Available at: https://www.cahabagba.com/news/critical-care-cpt-99291-widespread-prepayment-targeted-review-results-2/. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Prepayment edit of evaluation and management (E/M) code 99291. First Coast Service Options, Inc. website. Available at: medicare.fcso.com/Publications_B/2013/251608.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12A. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12B. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Critical care fact sheet. CGS Administrators, LLC website. Available at: www.cgsmedicare.com/partb/mr/pdf/critical_care_fact_sheet.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Same day same service policy. United Healthcare website. Available at: www.unitedhealthcareonline.com/ccmcontent/ProviderII/UHC/en-US/Main%20Menu/Tools%20&%20Resources/Policies%20and%20Protocols/Medicare%20Advantage%20Reimbursement%20Policies/S/SameDaySameService.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12G. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12E. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12I. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

Code 99291 is used for critical care, evaluation, and management of the critically ill or critically injured patient, first 30–74 minutes.1 It is to be reported only once per day per physician or group member of the same specialty.

Code 99292 is for critical care, evaluation, and management of the critically ill or critically injured patient, each additional 30 minutes. It is to be listed separately in addition to the code for primary service.1 Code 99292 is categorized as an add-on code. It must be reported on the same invoice as its primary code, 99291. Multiple units of code 99292 can be reported per day per physician/group.

Despite the increased resources and references for critical care billing, critical care reporting issues persist. Medicare data analysis continues to identify 99291 as high risk for claim payment errors, perpetuating prepayment claim edits for outlier utilization and location discrepancies (i.e., settings other than inpatient hospital, outpatient hospital, or the emergency department). 2,3,4

Bolster your documentation with these three key elements.

Critical Illness, Injury Management

Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) define “critical illness or injury” as a condition that acutely impairs one or more vital organ systems such that there is a high probability of imminent or life-threatening deterioration in the patient’s condition (e.g., central nervous system failure; circulatory failure; shock; renal, hepatic, metabolic, and/or respiratory failure).5

Hospitalists providing care to the critically ill patient must perform highly complex decision making and interventions of high intensity that are required to prevent the patient’s inevitable decline. CMS further elaborates that “the patient shall be critically ill or injured at the time of the physician’s visit.”6 This is to ensure that hospitalists and other specialists support the medical necessity of the service and do not continue to report critical care codes on days after the patient has become stable and improved.

Consider the following scenarios:

CMS examples of patients whose medical condition may warrant critical care services (99291, 99292):6

- An 81-year-old male patient is admitted to the ICU following abdominal aortic aneurysm resection. Two days after surgery, he requires fluids and pressors to maintain adequate perfusion and arterial pressures. He remains ventilator dependent.

- A 67-year-old female patient is three days post mitral valve repair. She develops petechiae, hypotension, and hypoxia requiring respiratory and circulatory support.

- A 70-year-old admitted for right lower lobe pneumococcal pneumonia with a history of COPD becomes hypoxic and hypotensive two days after admission.

- A 68-year-old admitted for an acute anterior wall myocardial infarction continues to have symptomatic ventricular tachycardia that is marginally responsive to antiarrhythmic therapy.

CMS examples of patients who may not satisfy Medicare medical necessity criteria, or do not meet critical care criteria, or who do not have a critical care illness or injury and, therefore, are not eligible for critical care payment but may be reported using another appropriate hospital care code, such as subsequent hospital care codes (99231–99233), initial hospital care codes (99221–99223), or hospital consultation codes (99251–99255) when applicable:1,6

- Patients admitted to a critical care unit because no other hospital beds were available;

- Patients admitted to a critical care unit for close nursing observation and/or frequent monitoring of vital signs (e.g., drug toxicity or overdose);

- Patients admitted to a critical care unit because hospital rules require certain treatments (e.g., insulin infusions) to be administered in the critical care unit; and

- Patients receiving only care of a chronic illness in absence of care for a critical illness (e.g., daily management of a chronic ventilator patient, management of or care related to dialysis for end-stage renal disease). Services considered palliative in nature as this type of care do not meet the definition of critical care services.7

Concurrent Care

Critically ill patients often require the care of hospitalists and other specialists throughout the course of treatment. Payors are sensitive to the multiple hours billed by multiple providers for a single patient on a given day. Claim logic provides an automated response to only allow reimbursement for 99291 once per day when reported by physicians of the same group and specialty.8 Physicians of different specialties can separately report critical care hours as long as they are caring for a condition that meets the definition of critical care.

The CMS example of this: A dermatologist evaluates and treats a rash on an ICU patient who is maintained on a ventilator and nitroglycerine infusion that are being managed by an intensivist. The dermatologist should not report a service for critical care.6

Similarly for hospitalists, if an intensivist is taking care of the critical condition and there is nothing more for the hospitalist to add to the plan of care for the critical condition, critical care services may not be justified.

When different specialists are reporting critical care on the same day, it is imperative for the documentation to demonstrate that care is not duplicative of any other provider’s care (i.e., identify management of different conditions or revising elements of the plan). The care cannot overlap the same time period of any other physician reporting critical care services.

Calculating Time

Critical care time constitutes bedside time and time spent on the patient’s unit/floor where the physician is immediately available to the patient (see Table 1). Certain labs, diagnostic studies, and procedures are considered inherent to critical care services and are not reported separately on the claim form: cardiac output measurements (93561, 93562); chest X-rays (71010, 71015, 71020); pulse oximetry (94760, 94761, 94762); blood gases and interpretation of data stored in computers, such as ECGs, blood pressures, and hematologic data (99090); gastric intubation (43752, 43753); temporary transcutaneous pacing (92953); ventilation management (94002–94004, 94660, 94662); and vascular access procedures (36000, 36410, 36415, 36591, 36600).1

Instead, physician time associated with the performance and/or interpretation of these services is toward the cumulative critical care time of the day. Services or procedures that are considered separately billable (e.g., central line placement, intubation, CPR) cannot contribute to critical care time.

When separately billable procedures are performed by the same provider/specialty group on the same day as critical care, physicians should make a notation in the medical record indicating the non-overlapping service times (e.g., “central line insertion is not included as critical care time”). This may assist with securing reimbursement when the payor requests the documentation for each reported claim item.

Activities on the floor/unit that do not directly contribute to patient care or management (e.g., review of literature, teaching rounds) cannot be counted toward critical care time. Do not count time associated with indirect care provided outside of the patient’s unit/floor (e.g., reviewing data or calling the family from the office) toward critical care time.

Family discussions can be counted toward critical care time but must take place at bedside or on the patient’s unit/floor. The patient must participate in the discussion unless medically unable or clinically incompetent to participate. If unable to participate, a notation in the chart must delineate the patient’s inability to participate and the reason.

Credited time can only involve obtaining a medical history and/or discussing treatment options or limitation(s) of treatment. The conversation must bear directly on patient management.1,7 Do not count time associated with providing periodic condition updates to the family, answering questions about the patient’s condition that are unrelated to decision making, or counseling the family during their grief process. If the conversation must take place via phone, it may be counted toward critical care time if the physician is calling from the patient’s unit/floor and the conversation involves the same criterion identified for face-to-face family meetings.10

Physicians should keep track of their critical care time throughout the day. Since critical care time is a cumulative service, each entry should include the total time that critical care services were provided (e.g., 45 minutes).10 Some payors may still impose the notation of “start-and-stop time” per encounter (e.g., 2–2:50 a.m.).

Same-specialty physicians (i.e., two hospitalists from the same group practice) may require separate claims. The initial critical care hour (99291) must be met by a single physician. Medically necessary critical care time beyond the first hour (99292) may be met individually by the same physician or collectively with another physician from the same group. The physician performing the additional time, beyond the first hour, reports the appropriate units of 99292 (see Table 1) under the corresponding NPI.11

CMS has issued instructions for contractors to recognize this atypical reporting method. However, non-Medicare payors may not recognize this newer reporting method and maintain that the cumulative service (by the same-specialty physician in the same provider group) should be reported under one physician name. Be sure to query the payors for appropriate reporting methods. TH

References

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Crosslin, R. Current Procedural Terminology 2015 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2014. 23-25.

- Widespread prepayment targeted review notification—CPT 99291. Cahaba website. Available at: www.cahabagba.com/news/widespread-prepayment-targeted-review-notification-part-b/. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Critical care CPT 99291 widespread prepayment targeted review results. Cahaba website. Available at: https://www.cahabagba.com/news/critical-care-cpt-99291-widespread-prepayment-targeted-review-results-2/. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Prepayment edit of evaluation and management (E/M) code 99291. First Coast Service Options, Inc. website. Available at: medicare.fcso.com/Publications_B/2013/251608.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12A. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12B. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Critical care fact sheet. CGS Administrators, LLC website. Available at: www.cgsmedicare.com/partb/mr/pdf/critical_care_fact_sheet.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Same day same service policy. United Healthcare website. Available at: www.unitedhealthcareonline.com/ccmcontent/ProviderII/UHC/en-US/Main%20Menu/Tools%20&%20Resources/Policies%20and%20Protocols/Medicare%20Advantage%20Reimbursement%20Policies/S/SameDaySameService.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12G. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12E. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12I. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

Code 99291 is used for critical care, evaluation, and management of the critically ill or critically injured patient, first 30–74 minutes.1 It is to be reported only once per day per physician or group member of the same specialty.

Code 99292 is for critical care, evaluation, and management of the critically ill or critically injured patient, each additional 30 minutes. It is to be listed separately in addition to the code for primary service.1 Code 99292 is categorized as an add-on code. It must be reported on the same invoice as its primary code, 99291. Multiple units of code 99292 can be reported per day per physician/group.

Despite the increased resources and references for critical care billing, critical care reporting issues persist. Medicare data analysis continues to identify 99291 as high risk for claim payment errors, perpetuating prepayment claim edits for outlier utilization and location discrepancies (i.e., settings other than inpatient hospital, outpatient hospital, or the emergency department). 2,3,4

Bolster your documentation with these three key elements.

Critical Illness, Injury Management

Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) define “critical illness or injury” as a condition that acutely impairs one or more vital organ systems such that there is a high probability of imminent or life-threatening deterioration in the patient’s condition (e.g., central nervous system failure; circulatory failure; shock; renal, hepatic, metabolic, and/or respiratory failure).5

Hospitalists providing care to the critically ill patient must perform highly complex decision making and interventions of high intensity that are required to prevent the patient’s inevitable decline. CMS further elaborates that “the patient shall be critically ill or injured at the time of the physician’s visit.”6 This is to ensure that hospitalists and other specialists support the medical necessity of the service and do not continue to report critical care codes on days after the patient has become stable and improved.

Consider the following scenarios:

CMS examples of patients whose medical condition may warrant critical care services (99291, 99292):6

- An 81-year-old male patient is admitted to the ICU following abdominal aortic aneurysm resection. Two days after surgery, he requires fluids and pressors to maintain adequate perfusion and arterial pressures. He remains ventilator dependent.

- A 67-year-old female patient is three days post mitral valve repair. She develops petechiae, hypotension, and hypoxia requiring respiratory and circulatory support.

- A 70-year-old admitted for right lower lobe pneumococcal pneumonia with a history of COPD becomes hypoxic and hypotensive two days after admission.

- A 68-year-old admitted for an acute anterior wall myocardial infarction continues to have symptomatic ventricular tachycardia that is marginally responsive to antiarrhythmic therapy.

CMS examples of patients who may not satisfy Medicare medical necessity criteria, or do not meet critical care criteria, or who do not have a critical care illness or injury and, therefore, are not eligible for critical care payment but may be reported using another appropriate hospital care code, such as subsequent hospital care codes (99231–99233), initial hospital care codes (99221–99223), or hospital consultation codes (99251–99255) when applicable:1,6

- Patients admitted to a critical care unit because no other hospital beds were available;

- Patients admitted to a critical care unit for close nursing observation and/or frequent monitoring of vital signs (e.g., drug toxicity or overdose);

- Patients admitted to a critical care unit because hospital rules require certain treatments (e.g., insulin infusions) to be administered in the critical care unit; and

- Patients receiving only care of a chronic illness in absence of care for a critical illness (e.g., daily management of a chronic ventilator patient, management of or care related to dialysis for end-stage renal disease). Services considered palliative in nature as this type of care do not meet the definition of critical care services.7

Concurrent Care

Critically ill patients often require the care of hospitalists and other specialists throughout the course of treatment. Payors are sensitive to the multiple hours billed by multiple providers for a single patient on a given day. Claim logic provides an automated response to only allow reimbursement for 99291 once per day when reported by physicians of the same group and specialty.8 Physicians of different specialties can separately report critical care hours as long as they are caring for a condition that meets the definition of critical care.

The CMS example of this: A dermatologist evaluates and treats a rash on an ICU patient who is maintained on a ventilator and nitroglycerine infusion that are being managed by an intensivist. The dermatologist should not report a service for critical care.6

Similarly for hospitalists, if an intensivist is taking care of the critical condition and there is nothing more for the hospitalist to add to the plan of care for the critical condition, critical care services may not be justified.

When different specialists are reporting critical care on the same day, it is imperative for the documentation to demonstrate that care is not duplicative of any other provider’s care (i.e., identify management of different conditions or revising elements of the plan). The care cannot overlap the same time period of any other physician reporting critical care services.

Calculating Time

Critical care time constitutes bedside time and time spent on the patient’s unit/floor where the physician is immediately available to the patient (see Table 1). Certain labs, diagnostic studies, and procedures are considered inherent to critical care services and are not reported separately on the claim form: cardiac output measurements (93561, 93562); chest X-rays (71010, 71015, 71020); pulse oximetry (94760, 94761, 94762); blood gases and interpretation of data stored in computers, such as ECGs, blood pressures, and hematologic data (99090); gastric intubation (43752, 43753); temporary transcutaneous pacing (92953); ventilation management (94002–94004, 94660, 94662); and vascular access procedures (36000, 36410, 36415, 36591, 36600).1

Instead, physician time associated with the performance and/or interpretation of these services is toward the cumulative critical care time of the day. Services or procedures that are considered separately billable (e.g., central line placement, intubation, CPR) cannot contribute to critical care time.

When separately billable procedures are performed by the same provider/specialty group on the same day as critical care, physicians should make a notation in the medical record indicating the non-overlapping service times (e.g., “central line insertion is not included as critical care time”). This may assist with securing reimbursement when the payor requests the documentation for each reported claim item.

Activities on the floor/unit that do not directly contribute to patient care or management (e.g., review of literature, teaching rounds) cannot be counted toward critical care time. Do not count time associated with indirect care provided outside of the patient’s unit/floor (e.g., reviewing data or calling the family from the office) toward critical care time.

Family discussions can be counted toward critical care time but must take place at bedside or on the patient’s unit/floor. The patient must participate in the discussion unless medically unable or clinically incompetent to participate. If unable to participate, a notation in the chart must delineate the patient’s inability to participate and the reason.

Credited time can only involve obtaining a medical history and/or discussing treatment options or limitation(s) of treatment. The conversation must bear directly on patient management.1,7 Do not count time associated with providing periodic condition updates to the family, answering questions about the patient’s condition that are unrelated to decision making, or counseling the family during their grief process. If the conversation must take place via phone, it may be counted toward critical care time if the physician is calling from the patient’s unit/floor and the conversation involves the same criterion identified for face-to-face family meetings.10

Physicians should keep track of their critical care time throughout the day. Since critical care time is a cumulative service, each entry should include the total time that critical care services were provided (e.g., 45 minutes).10 Some payors may still impose the notation of “start-and-stop time” per encounter (e.g., 2–2:50 a.m.).

Same-specialty physicians (i.e., two hospitalists from the same group practice) may require separate claims. The initial critical care hour (99291) must be met by a single physician. Medically necessary critical care time beyond the first hour (99292) may be met individually by the same physician or collectively with another physician from the same group. The physician performing the additional time, beyond the first hour, reports the appropriate units of 99292 (see Table 1) under the corresponding NPI.11

CMS has issued instructions for contractors to recognize this atypical reporting method. However, non-Medicare payors may not recognize this newer reporting method and maintain that the cumulative service (by the same-specialty physician in the same provider group) should be reported under one physician name. Be sure to query the payors for appropriate reporting methods. TH

References

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Crosslin, R. Current Procedural Terminology 2015 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2014. 23-25.

- Widespread prepayment targeted review notification—CPT 99291. Cahaba website. Available at: www.cahabagba.com/news/widespread-prepayment-targeted-review-notification-part-b/. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Critical care CPT 99291 widespread prepayment targeted review results. Cahaba website. Available at: https://www.cahabagba.com/news/critical-care-cpt-99291-widespread-prepayment-targeted-review-results-2/. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Prepayment edit of evaluation and management (E/M) code 99291. First Coast Service Options, Inc. website. Available at: medicare.fcso.com/Publications_B/2013/251608.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12A. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12B. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Critical care fact sheet. CGS Administrators, LLC website. Available at: www.cgsmedicare.com/partb/mr/pdf/critical_care_fact_sheet.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Same day same service policy. United Healthcare website. Available at: www.unitedhealthcareonline.com/ccmcontent/ProviderII/UHC/en-US/Main%20Menu/Tools%20&%20Resources/Policies%20and%20Protocols/Medicare%20Advantage%20Reimbursement%20Policies/S/SameDaySameService.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12G. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12E. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12I. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

ICD-10 Flexibility Helps Transition to New Coding Systems, Principles, Payer Policy Requirements

Effective October 1, providers submit claims with ICD-10-CM codes. As they adapt to this new system, physicians, clinical staff, and billers should be relying on feedback from each other to achieve a successful transition. On July 6, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), in conjunction with the AMA, issued a letter to the provider community offering ICD-10-CM guidance. The joint announcement and guidance regarding ICD-10 flexibilities minimizes the anxiety that often accompanies change and clarifies a few key points about claim scrutiny.1

According to the correspondence, “CMS is releasing additional guidance that will allow for flexibility in the claims auditing and quality reporting process as the medical community gains experience using the new ICD-10 code set.”1 The guidance specifies the flexibility that will be used during the first 12 months of ICD-10-CM use.

This “flexibility” is an opportunity and should not be disregarded. Physician practices can effectively use this time to become accustomed to the ICD-10-CM system, correct coding principles, and payer policy requirements. Internal audit and review processes should increase in order to correct or confirm appropriate coding and claim submission.

Valid Codes

Medicare review contractors are instructed “not to deny physician or other practitioner claims billed under the Part B physician fee schedule through either automated medical review or complex medical review based solely on the specificity of the ICD-10 diagnosis code as long as the physician/practitioner used a valid code from the right family.”2 This “flexibility” will only occur for the first 12 months of ICD-10-CM implementation; the ultimate goal is for providers to assign the correct diagnosis code and the appropriate level of specificity after one year.

The “family code” allowance should not be confused with provision of an incomplete or truncated diagnosis code; these types of codes will always result in claim denial. The ICD-10-CM code presented on the claim form must be carried out to the highest character available for that particular code.

For example, an initial encounter involving an infected peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) is reported with ICD-10-CM T80.212A (local infection due to central venous catheter). An individual unfamiliar with ICD-10-CM nomenclature may not realize that the seventh extension character of the code is required to carry the code out to its highest level of specificity. If T880.212 is mistakenly reported because the encounter detail (i.e., initial encounter [A], subsequent encounter [D], or sequela [S]) was not documented or provided to the biller, the payers’ claim edit system will identify this as a truncated or invalid diagnosis and reject the claim. Therefore, the code is required to be complete. The “flexibility” refers to reporting the code that best reflects the documented condition. As long as the reported code comes from the same family of codes and is valid, the claim cannot be denied.

Code Families

Code families are “codes within a category [that] are clinically related and provide differences in capturing specific information on the type of condition.”3 Upon review, Medicare will allow ICD-10-CM codes from the same code family to be reported on the claim without penalty if the most accurate code is not selected.

For example, a patient with COPD with acute exacerbation is admitted to the hospital. During the 12-month “flexibility” period, the claim could include J44.9 (COPD, unspecified) without being considered erroneous. The most appropriate code, however, is J44.1 (COPD with acute exacerbation). During the course of the hospitalization, if the physician determines that the COPD exacerbation was caused by an acute lower respiratory infection, J44.0 (COPD with acute lower respiratory infection) is the best option.

The provider goal for this flexibility period is to identify all of the “unspecified codes” used on their claims, review the documentation, and determine the most appropriate code. The practice staff assigned to this task would then provide feedback to the physicians to enhance their future reporting strategies. Although “unspecified” codes are often reported by default, physicians and staff should attempt to reduce usage of this code type unless the patient’s condition is unable to be further specified or categorized at a given point in time.

For example, it would not be acceptable to report R10.8 (unspecified abdominal pain) when a more specific diagnosis code can be easily determined by patient history or exam findings (e.g. right upper quadrant abdominal pain, R10.11).

Affected Claims

As previously stated, “Medicare review contractors will not deny physician or other practitioner claims billed under the Part B physician fee schedule through either automated medical review or complex medical record review.”3 The review contractors included are as follows:

- Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) process claims submitted by physicians, hospitals, and other healthcare professionals and submit payment to those providers according to Medicare rules and regulations (including identifying and correcting underpayments and overpayments);

- Recovery Auditors (RACs) review claims to identify potential underpayments and overpayments in Medicare fee-for-service, as part of the Recovery Audit Program;

- Zone Program Integrity Contractors (ZPICs) perform investigations that are unique and tailored to the specific circumstances and occur only in situations where there is potential fraud and take appropriate corrective actions; and

- Supplemental Medical Review Contractor (SMRCs) conduct nationwide medical review as directed by CMS (including identifying underpayments and overpayments).4

This instruction applies to claims that are typically selected for review due to the ICD-10-CM code used on the claim but does not affect claims that are selected for review for other reasons (e.g. modifier 25 [separately identifiable visit performed on the same day as another procedure or service], unbundling, service-specific current procedural terminology code). If a claim is selected for one of these other reasons and does not meet the corresponding criterion, the service will be denied. This instruction also excludes claims for services that correspond to an existing local coverage determination (LCD) or national coverage determination (NCD).

For example, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is not considered “medically necessary” when reported with R10.8 (unspecified abdominal pain) and would be denied. EGD requires a more specific diagnosis (e.g. right upper quadrant abdominal pain, R10.11) per Medicare LCD.

Non-Medicare Payer Considerations

Most payers that are required to convert to ICD-10-CM have also provided some guidance about claim submission. Although most do not address the audit and review process, payers will follow some basic principles:

- Claims submitted with service dates on or after October 1 must use ICD-10-CM codes.

- Claims submitted with service dates prior to October 1 must use ICD-9-CM codes; this includes claims that are initially submitted after October 1 or require correction and resubmission after October 1.

- Physician claims will be held to medical necessity guidelines identified by specific ICD-10-CM codes represented in existing payer policies.

- General equivalence mappings (GEMs) should only be used as a starting point to convert large databases and large code lists from ICD-9 to ICD-10. Many ICD-9-CM codes do not crosswalk directly to an ICD-10-CM code. Physician and staff should continue to use the ICD-10-CM coding books and resources to determine the most accurate code selection.

- “Unspecified” codes are only for use when the information in the medical record is insufficient to assign a more specific code.5,6,7

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS and AMA announce efforts to help providers get ready for ICD-10. July 6, 2015. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS and AMA announce efforts to help providers get ready for ICD-10: frequently asked questions. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Clarifying questions and answers related to the July 6, 2015 CMS/AMA joint announcement and guidance regarding ICD-10 flexibilities. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Learning Network: Medicare claim review programs. May 2015. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Aetna. Preparation for ICD-10-CM: frequently asked questions. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Independence Blue Cross. Transition to ICD-10: frequently asked questions. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Cigna. Ready, Set, Switch: Know Your ICD-10 Codes. Accessed November 16, 2015.

Effective October 1, providers submit claims with ICD-10-CM codes. As they adapt to this new system, physicians, clinical staff, and billers should be relying on feedback from each other to achieve a successful transition. On July 6, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), in conjunction with the AMA, issued a letter to the provider community offering ICD-10-CM guidance. The joint announcement and guidance regarding ICD-10 flexibilities minimizes the anxiety that often accompanies change and clarifies a few key points about claim scrutiny.1

According to the correspondence, “CMS is releasing additional guidance that will allow for flexibility in the claims auditing and quality reporting process as the medical community gains experience using the new ICD-10 code set.”1 The guidance specifies the flexibility that will be used during the first 12 months of ICD-10-CM use.

This “flexibility” is an opportunity and should not be disregarded. Physician practices can effectively use this time to become accustomed to the ICD-10-CM system, correct coding principles, and payer policy requirements. Internal audit and review processes should increase in order to correct or confirm appropriate coding and claim submission.

Valid Codes

Medicare review contractors are instructed “not to deny physician or other practitioner claims billed under the Part B physician fee schedule through either automated medical review or complex medical review based solely on the specificity of the ICD-10 diagnosis code as long as the physician/practitioner used a valid code from the right family.”2 This “flexibility” will only occur for the first 12 months of ICD-10-CM implementation; the ultimate goal is for providers to assign the correct diagnosis code and the appropriate level of specificity after one year.

The “family code” allowance should not be confused with provision of an incomplete or truncated diagnosis code; these types of codes will always result in claim denial. The ICD-10-CM code presented on the claim form must be carried out to the highest character available for that particular code.

For example, an initial encounter involving an infected peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) is reported with ICD-10-CM T80.212A (local infection due to central venous catheter). An individual unfamiliar with ICD-10-CM nomenclature may not realize that the seventh extension character of the code is required to carry the code out to its highest level of specificity. If T880.212 is mistakenly reported because the encounter detail (i.e., initial encounter [A], subsequent encounter [D], or sequela [S]) was not documented or provided to the biller, the payers’ claim edit system will identify this as a truncated or invalid diagnosis and reject the claim. Therefore, the code is required to be complete. The “flexibility” refers to reporting the code that best reflects the documented condition. As long as the reported code comes from the same family of codes and is valid, the claim cannot be denied.

Code Families

Code families are “codes within a category [that] are clinically related and provide differences in capturing specific information on the type of condition.”3 Upon review, Medicare will allow ICD-10-CM codes from the same code family to be reported on the claim without penalty if the most accurate code is not selected.

For example, a patient with COPD with acute exacerbation is admitted to the hospital. During the 12-month “flexibility” period, the claim could include J44.9 (COPD, unspecified) without being considered erroneous. The most appropriate code, however, is J44.1 (COPD with acute exacerbation). During the course of the hospitalization, if the physician determines that the COPD exacerbation was caused by an acute lower respiratory infection, J44.0 (COPD with acute lower respiratory infection) is the best option.

The provider goal for this flexibility period is to identify all of the “unspecified codes” used on their claims, review the documentation, and determine the most appropriate code. The practice staff assigned to this task would then provide feedback to the physicians to enhance their future reporting strategies. Although “unspecified” codes are often reported by default, physicians and staff should attempt to reduce usage of this code type unless the patient’s condition is unable to be further specified or categorized at a given point in time.

For example, it would not be acceptable to report R10.8 (unspecified abdominal pain) when a more specific diagnosis code can be easily determined by patient history or exam findings (e.g. right upper quadrant abdominal pain, R10.11).

Affected Claims

As previously stated, “Medicare review contractors will not deny physician or other practitioner claims billed under the Part B physician fee schedule through either automated medical review or complex medical record review.”3 The review contractors included are as follows:

- Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) process claims submitted by physicians, hospitals, and other healthcare professionals and submit payment to those providers according to Medicare rules and regulations (including identifying and correcting underpayments and overpayments);

- Recovery Auditors (RACs) review claims to identify potential underpayments and overpayments in Medicare fee-for-service, as part of the Recovery Audit Program;

- Zone Program Integrity Contractors (ZPICs) perform investigations that are unique and tailored to the specific circumstances and occur only in situations where there is potential fraud and take appropriate corrective actions; and

- Supplemental Medical Review Contractor (SMRCs) conduct nationwide medical review as directed by CMS (including identifying underpayments and overpayments).4

This instruction applies to claims that are typically selected for review due to the ICD-10-CM code used on the claim but does not affect claims that are selected for review for other reasons (e.g. modifier 25 [separately identifiable visit performed on the same day as another procedure or service], unbundling, service-specific current procedural terminology code). If a claim is selected for one of these other reasons and does not meet the corresponding criterion, the service will be denied. This instruction also excludes claims for services that correspond to an existing local coverage determination (LCD) or national coverage determination (NCD).

For example, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is not considered “medically necessary” when reported with R10.8 (unspecified abdominal pain) and would be denied. EGD requires a more specific diagnosis (e.g. right upper quadrant abdominal pain, R10.11) per Medicare LCD.

Non-Medicare Payer Considerations

Most payers that are required to convert to ICD-10-CM have also provided some guidance about claim submission. Although most do not address the audit and review process, payers will follow some basic principles:

- Claims submitted with service dates on or after October 1 must use ICD-10-CM codes.

- Claims submitted with service dates prior to October 1 must use ICD-9-CM codes; this includes claims that are initially submitted after October 1 or require correction and resubmission after October 1.

- Physician claims will be held to medical necessity guidelines identified by specific ICD-10-CM codes represented in existing payer policies.

- General equivalence mappings (GEMs) should only be used as a starting point to convert large databases and large code lists from ICD-9 to ICD-10. Many ICD-9-CM codes do not crosswalk directly to an ICD-10-CM code. Physician and staff should continue to use the ICD-10-CM coding books and resources to determine the most accurate code selection.

- “Unspecified” codes are only for use when the information in the medical record is insufficient to assign a more specific code.5,6,7

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS and AMA announce efforts to help providers get ready for ICD-10. July 6, 2015. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS and AMA announce efforts to help providers get ready for ICD-10: frequently asked questions. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Clarifying questions and answers related to the July 6, 2015 CMS/AMA joint announcement and guidance regarding ICD-10 flexibilities. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Learning Network: Medicare claim review programs. May 2015. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Aetna. Preparation for ICD-10-CM: frequently asked questions. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Independence Blue Cross. Transition to ICD-10: frequently asked questions. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Cigna. Ready, Set, Switch: Know Your ICD-10 Codes. Accessed November 16, 2015.

Effective October 1, providers submit claims with ICD-10-CM codes. As they adapt to this new system, physicians, clinical staff, and billers should be relying on feedback from each other to achieve a successful transition. On July 6, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), in conjunction with the AMA, issued a letter to the provider community offering ICD-10-CM guidance. The joint announcement and guidance regarding ICD-10 flexibilities minimizes the anxiety that often accompanies change and clarifies a few key points about claim scrutiny.1

According to the correspondence, “CMS is releasing additional guidance that will allow for flexibility in the claims auditing and quality reporting process as the medical community gains experience using the new ICD-10 code set.”1 The guidance specifies the flexibility that will be used during the first 12 months of ICD-10-CM use.

This “flexibility” is an opportunity and should not be disregarded. Physician practices can effectively use this time to become accustomed to the ICD-10-CM system, correct coding principles, and payer policy requirements. Internal audit and review processes should increase in order to correct or confirm appropriate coding and claim submission.

Valid Codes

Medicare review contractors are instructed “not to deny physician or other practitioner claims billed under the Part B physician fee schedule through either automated medical review or complex medical review based solely on the specificity of the ICD-10 diagnosis code as long as the physician/practitioner used a valid code from the right family.”2 This “flexibility” will only occur for the first 12 months of ICD-10-CM implementation; the ultimate goal is for providers to assign the correct diagnosis code and the appropriate level of specificity after one year.

The “family code” allowance should not be confused with provision of an incomplete or truncated diagnosis code; these types of codes will always result in claim denial. The ICD-10-CM code presented on the claim form must be carried out to the highest character available for that particular code.

For example, an initial encounter involving an infected peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) is reported with ICD-10-CM T80.212A (local infection due to central venous catheter). An individual unfamiliar with ICD-10-CM nomenclature may not realize that the seventh extension character of the code is required to carry the code out to its highest level of specificity. If T880.212 is mistakenly reported because the encounter detail (i.e., initial encounter [A], subsequent encounter [D], or sequela [S]) was not documented or provided to the biller, the payers’ claim edit system will identify this as a truncated or invalid diagnosis and reject the claim. Therefore, the code is required to be complete. The “flexibility” refers to reporting the code that best reflects the documented condition. As long as the reported code comes from the same family of codes and is valid, the claim cannot be denied.

Code Families

Code families are “codes within a category [that] are clinically related and provide differences in capturing specific information on the type of condition.”3 Upon review, Medicare will allow ICD-10-CM codes from the same code family to be reported on the claim without penalty if the most accurate code is not selected.

For example, a patient with COPD with acute exacerbation is admitted to the hospital. During the 12-month “flexibility” period, the claim could include J44.9 (COPD, unspecified) without being considered erroneous. The most appropriate code, however, is J44.1 (COPD with acute exacerbation). During the course of the hospitalization, if the physician determines that the COPD exacerbation was caused by an acute lower respiratory infection, J44.0 (COPD with acute lower respiratory infection) is the best option.

The provider goal for this flexibility period is to identify all of the “unspecified codes” used on their claims, review the documentation, and determine the most appropriate code. The practice staff assigned to this task would then provide feedback to the physicians to enhance their future reporting strategies. Although “unspecified” codes are often reported by default, physicians and staff should attempt to reduce usage of this code type unless the patient’s condition is unable to be further specified or categorized at a given point in time.

For example, it would not be acceptable to report R10.8 (unspecified abdominal pain) when a more specific diagnosis code can be easily determined by patient history or exam findings (e.g. right upper quadrant abdominal pain, R10.11).

Affected Claims

As previously stated, “Medicare review contractors will not deny physician or other practitioner claims billed under the Part B physician fee schedule through either automated medical review or complex medical record review.”3 The review contractors included are as follows:

- Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) process claims submitted by physicians, hospitals, and other healthcare professionals and submit payment to those providers according to Medicare rules and regulations (including identifying and correcting underpayments and overpayments);

- Recovery Auditors (RACs) review claims to identify potential underpayments and overpayments in Medicare fee-for-service, as part of the Recovery Audit Program;

- Zone Program Integrity Contractors (ZPICs) perform investigations that are unique and tailored to the specific circumstances and occur only in situations where there is potential fraud and take appropriate corrective actions; and

- Supplemental Medical Review Contractor (SMRCs) conduct nationwide medical review as directed by CMS (including identifying underpayments and overpayments).4

This instruction applies to claims that are typically selected for review due to the ICD-10-CM code used on the claim but does not affect claims that are selected for review for other reasons (e.g. modifier 25 [separately identifiable visit performed on the same day as another procedure or service], unbundling, service-specific current procedural terminology code). If a claim is selected for one of these other reasons and does not meet the corresponding criterion, the service will be denied. This instruction also excludes claims for services that correspond to an existing local coverage determination (LCD) or national coverage determination (NCD).

For example, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is not considered “medically necessary” when reported with R10.8 (unspecified abdominal pain) and would be denied. EGD requires a more specific diagnosis (e.g. right upper quadrant abdominal pain, R10.11) per Medicare LCD.

Non-Medicare Payer Considerations

Most payers that are required to convert to ICD-10-CM have also provided some guidance about claim submission. Although most do not address the audit and review process, payers will follow some basic principles:

- Claims submitted with service dates on or after October 1 must use ICD-10-CM codes.

- Claims submitted with service dates prior to October 1 must use ICD-9-CM codes; this includes claims that are initially submitted after October 1 or require correction and resubmission after October 1.

- Physician claims will be held to medical necessity guidelines identified by specific ICD-10-CM codes represented in existing payer policies.

- General equivalence mappings (GEMs) should only be used as a starting point to convert large databases and large code lists from ICD-9 to ICD-10. Many ICD-9-CM codes do not crosswalk directly to an ICD-10-CM code. Physician and staff should continue to use the ICD-10-CM coding books and resources to determine the most accurate code selection.

- “Unspecified” codes are only for use when the information in the medical record is insufficient to assign a more specific code.5,6,7

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS and AMA announce efforts to help providers get ready for ICD-10. July 6, 2015. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS and AMA announce efforts to help providers get ready for ICD-10: frequently asked questions. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Clarifying questions and answers related to the July 6, 2015 CMS/AMA joint announcement and guidance regarding ICD-10 flexibilities. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Learning Network: Medicare claim review programs. May 2015. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Aetna. Preparation for ICD-10-CM: frequently asked questions. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Independence Blue Cross. Transition to ICD-10: frequently asked questions. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Cigna. Ready, Set, Switch: Know Your ICD-10 Codes. Accessed November 16, 2015.

Billing, Coding Documentation to Support Services, Minimize Risks

The electronic health record (EHR) has many benefits:

- Improved patient care;

- Improved care coordination;

- Improved diagnostics and patient outcomes;

- Increased patient participation; and

- Increased practice efficiencies and cost savings.1

EHRs also introduce risks, however. Heightened concern about EHR misuse and vulnerability elevates the level of scrutiny placed on provider documentation as it relates to billing and coding. Without clear guidelines from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) or other payers, the potential for unintentional misapplication exists. Auditor misinterpretation is also possible. Providers should utilize simple defensive documentation principles to support their services and minimize their risks.

Reason for Encounter

Under section 1862 (a)(1)(A) of the Social Security Act, the Medicare Program may only pay for items and services that are “reasonable and necessary for the diagnosis or treatment of illness or injury or to improve the functioning of a malformed body member,” unless there is another statutory authorization for payment (e.g. colorectal cancer screening).2

A payer can determine if a service is “reasonable and necessary” based on the service indication. The reason for the patient encounter, otherwise known as the chief complaint, must be evident. This can be a symptom, problem, condition, diagnosis, physician-recommended return, or another factor that necessitates the encounter.1 It cannot be inferred and must be clearly stated in the documentation. Without it, a payer may question the medical necessity of the service, especially if it involves hospital-based services in the course of which multiple specialists will see the patient on any given date. Payers are likely to deny services that cannot be easily differentiated (e.g. “no c/o”). Furthermore, payers can deny concurrent care services for the following reasons:3

- Services exceed normal frequency or duration for a given condition without documented circumstances requiring additional care; or

- Services by one physician duplicate/overlap those of the other provider without any recognizable distinction.

Providers should be specific in identifying the encounter reason, as in the following examples: “Patient seen for shortness of breath” or “Patient with COPD, feeling improved with 3L O2 NC.”

Assessment and Plan

Accurately representing patient complexity for every visit throughout the hospitalization presents its challenges. Although the problem list may not dramatically change day to day, providers must formulate an assessment of the patient’s condition with a corresponding plan of care for each encounter. Documenting problems without a corresponding plan of care does not substantiate physician participation in the management of that problem. Providing a brief, generalized comment (e.g. “DM, CKD, CHF: Continue current treatment plan”) minimizes the complexity and effort put forth in the encounter and could result in auditor downgrading upon documentation review.

Developing shortcuts might falsely minimize the provider’s documentation burden. An electronic documentation system might make it possible to copy previous progress notes into the current encounter to save time; however, the previously entered information could include elements that do not require reassessment during a subsequent encounter or contain information about conditions that are being managed concurrently by another specialist (e.g. CKD being managed by the nephrologist). Leaving the copied information unmodified may not accurately reflect the patient’s current condition or the care provided by the hospitalist during the current encounter. Information that is pulled forward or copied and pasted from a previous entry should be modified to demonstrate updated content and nonoverlapping care relevant to that date.

According to the Office of Inspector General (OIG), “inappropriate copy-pasting could facilitate attempts to inflate claims and duplicate or create fraudulent claims.”4

An equally problematic EHR function involves “overdocumentation,” the practice of inserting false or irrelevant documentation to create the appearance of support for billing higher level services.4 EHR technology has the ability to auto-populate fields using templates built into the system or generate extensive documentation on the basis of a single click. The OIG cautions providers to use these features carefully, because they can produce information suggesting the practitioner performed more comprehensive services than were actually rendered.4

An example is the inclusion of the same lab results more than once. Although clinicians include this information as a reference to avoid having to “find it somewhere in the chart” when it is needed—as a basis for comparison, for example—auditors mistake this as an attempt to gain credit for the daily review of the same “old” information. Including only relevant data will mitigate this concern.

Authorship

Dates and signatures are essential to each encounter. Medicare requires services provided/ordered to be authenticated by the author.5 A reviewer must be able to identify each individual who performs, documents, and bills for a service on a given date. Progress notes that fail to identify the service date or service provider will likely result in denial.

Additionally, a service is questioned when two different sets of handwriting appear on a note, yet only one signature is provided. Since the reviewer cannot confirm the credentials of the unidentified individual and cannot be sure which portion belongs to the identified individual, the entire note is disregarded.

Notes that contain an illegible signature are equally problematic. If the legibility of the signature prevents the reviewer from correctly identifying the rendering provider, the service may be denied.

CMS has instructed Medicare contractors to request a signed provider attestation before issuing a denial.5 The provider should print his/her name beside the signature or include a separate signature sheet with the requested documentation to assist the reviewer in provider identification. Stamped signatures are not acceptable under any circumstance. Medicare accepts only handwritten or electronic signatures.5

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- HealthIT.gov. Benefits of electronic health records (EHRs). Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Social Security Administration. Exclusions from coverage and Medicare as secondary payer. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual: Chapter 15—Covered medical and other health services. Chapter 15, Section 30.E. Concurrent care. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Inspector General. CMS and its contractors have adopted few program integrity practices to address vulnerabilities in EHRs. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Signature guidelines for medical review purposes. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1995 documentation guidelines for evaluation and management services. Accessed August 1, 2015.

The electronic health record (EHR) has many benefits:

- Improved patient care;

- Improved care coordination;

- Improved diagnostics and patient outcomes;

- Increased patient participation; and

- Increased practice efficiencies and cost savings.1

EHRs also introduce risks, however. Heightened concern about EHR misuse and vulnerability elevates the level of scrutiny placed on provider documentation as it relates to billing and coding. Without clear guidelines from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) or other payers, the potential for unintentional misapplication exists. Auditor misinterpretation is also possible. Providers should utilize simple defensive documentation principles to support their services and minimize their risks.

Reason for Encounter

Under section 1862 (a)(1)(A) of the Social Security Act, the Medicare Program may only pay for items and services that are “reasonable and necessary for the diagnosis or treatment of illness or injury or to improve the functioning of a malformed body member,” unless there is another statutory authorization for payment (e.g. colorectal cancer screening).2

A payer can determine if a service is “reasonable and necessary” based on the service indication. The reason for the patient encounter, otherwise known as the chief complaint, must be evident. This can be a symptom, problem, condition, diagnosis, physician-recommended return, or another factor that necessitates the encounter.1 It cannot be inferred and must be clearly stated in the documentation. Without it, a payer may question the medical necessity of the service, especially if it involves hospital-based services in the course of which multiple specialists will see the patient on any given date. Payers are likely to deny services that cannot be easily differentiated (e.g. “no c/o”). Furthermore, payers can deny concurrent care services for the following reasons:3

- Services exceed normal frequency or duration for a given condition without documented circumstances requiring additional care; or

- Services by one physician duplicate/overlap those of the other provider without any recognizable distinction.

Providers should be specific in identifying the encounter reason, as in the following examples: “Patient seen for shortness of breath” or “Patient with COPD, feeling improved with 3L O2 NC.”

Assessment and Plan

Accurately representing patient complexity for every visit throughout the hospitalization presents its challenges. Although the problem list may not dramatically change day to day, providers must formulate an assessment of the patient’s condition with a corresponding plan of care for each encounter. Documenting problems without a corresponding plan of care does not substantiate physician participation in the management of that problem. Providing a brief, generalized comment (e.g. “DM, CKD, CHF: Continue current treatment plan”) minimizes the complexity and effort put forth in the encounter and could result in auditor downgrading upon documentation review.

Developing shortcuts might falsely minimize the provider’s documentation burden. An electronic documentation system might make it possible to copy previous progress notes into the current encounter to save time; however, the previously entered information could include elements that do not require reassessment during a subsequent encounter or contain information about conditions that are being managed concurrently by another specialist (e.g. CKD being managed by the nephrologist). Leaving the copied information unmodified may not accurately reflect the patient’s current condition or the care provided by the hospitalist during the current encounter. Information that is pulled forward or copied and pasted from a previous entry should be modified to demonstrate updated content and nonoverlapping care relevant to that date.

According to the Office of Inspector General (OIG), “inappropriate copy-pasting could facilitate attempts to inflate claims and duplicate or create fraudulent claims.”4

An equally problematic EHR function involves “overdocumentation,” the practice of inserting false or irrelevant documentation to create the appearance of support for billing higher level services.4 EHR technology has the ability to auto-populate fields using templates built into the system or generate extensive documentation on the basis of a single click. The OIG cautions providers to use these features carefully, because they can produce information suggesting the practitioner performed more comprehensive services than were actually rendered.4

An example is the inclusion of the same lab results more than once. Although clinicians include this information as a reference to avoid having to “find it somewhere in the chart” when it is needed—as a basis for comparison, for example—auditors mistake this as an attempt to gain credit for the daily review of the same “old” information. Including only relevant data will mitigate this concern.

Authorship

Dates and signatures are essential to each encounter. Medicare requires services provided/ordered to be authenticated by the author.5 A reviewer must be able to identify each individual who performs, documents, and bills for a service on a given date. Progress notes that fail to identify the service date or service provider will likely result in denial.

Additionally, a service is questioned when two different sets of handwriting appear on a note, yet only one signature is provided. Since the reviewer cannot confirm the credentials of the unidentified individual and cannot be sure which portion belongs to the identified individual, the entire note is disregarded.

Notes that contain an illegible signature are equally problematic. If the legibility of the signature prevents the reviewer from correctly identifying the rendering provider, the service may be denied.

CMS has instructed Medicare contractors to request a signed provider attestation before issuing a denial.5 The provider should print his/her name beside the signature or include a separate signature sheet with the requested documentation to assist the reviewer in provider identification. Stamped signatures are not acceptable under any circumstance. Medicare accepts only handwritten or electronic signatures.5

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- HealthIT.gov. Benefits of electronic health records (EHRs). Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Social Security Administration. Exclusions from coverage and Medicare as secondary payer. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual: Chapter 15—Covered medical and other health services. Chapter 15, Section 30.E. Concurrent care. Accessed August 1, 2015.