User login

Returns to Emergency Department, Observation, or Inpatient Care Within 30 Days After Hospitalization in 4 States, 2009 and 2010 Versus 2013 and 2014

Given the frequency, potential preventability, and costs associated with hospital readmissions, reducing readmissions is a priority in efforts to improve the quality and value of healthcare.1,2 State and national bodies have created diverse initiatives to facilitate improvements in hospital discharge practices and reduce 30-day readmission rates across payers.3-5 For example, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement have published tools for improving discharge practices.6,7 Medicare instituted financial penalties for hospitals with higher-than-expected readmission rates for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure (HF), and pneumonia in 2012, while private payers and Medicaid programs have established their own policies.8-13 Furthermore, private payers and Medicaid programs shifted toward capitated and value-based reimbursement models in which readmissions lead to financial losses for hospitals.14,15 Accordingly, hospitals have implemented diverse interventions to reduce readmissions.16,17 From 2009 to 2013, 30-day readmissions declined among privately insured adults (from 12.4% to 11.7%), Medicare patients (from 22.0% to 20.0%), and uninsured individuals (11.5% to 11.0%) but climbed among patients with Medicaid (from 19.8% to 20.5%) after index admissions for AMI, HF, pneumonia, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.18

To date, research, policies, and quality improvement interventions have largely focused on improvements to one aspect of the system of care—that provided in the inpatient setting—among older adults with Medicare. Yet, inpatient readmissions may underestimate how often patients return to the hospital because patients can be placed under observation or stabilized and discharged from the emergency department (ED) instead of being readmitted. Observation and ED visits are less costly to payers than inpatient admissions.19 Thus, information about utilization of inpatient, observation, and ED visits within 30 days of hospital discharge may be more informative than inpatient readmissions alone. However, little is known about trends in returns to the hospital for observation and ED visits and whether such trends vary by payer.

Our objective was to assess whether changes have occurred in rates of total 30-day, all-cause, unplanned returns to the hospital among adults with index admissions for AMI, HF, and pneumonia in which returns to the hospital included inpatient readmissions, observation visits, and ED visits. We also assessed whether changes in the rate of hospital inpatient readmissions coincided with changes in rates of returns for ED or observation visits. To examine the effects of readmission policies implemented by diverse payers and broad changes to the health system following the Affordable Care Act, we compared data from 201 hospitals in 4 states in 2009 and 2010 with data from the same hospitals for 2013 and 2014.

METHODS

Data Sources, Populations, and Study Variables

We used Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) State Inpatient Databases, State Emergency Department Databases, and State Ambulatory Surgery and Services Databases from Georgia, Nebraska, South Carolina, and Tennessee. These states comprise 7% of the US population and were the only states with data that included all observation and ED visits as well as encrypted patient identification numbers that permitted linkage across facilities and hospitals.20

Index admissions for patients aged 18 years and older were eligible if they occurred at nonfederal general medical/surgical hospitals (excluding critical access hospitals) that had at least 1 index admission per target condition per year and at least 5 inpatient, observation, and ED visits for any condition per year.

We classified patients into the following 4 populations by age and insurance coverage: 18 to 64 years with private insurance, 65 years and older with Medicare (excluding younger adults with Medicare), 18 to 64 years with Medicaid, and 18 to 64 years without insurance. We identified patients aged 65 years and older with Medicare by using the primary or secondary expected payer for the index admission. This group included patients who were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. If Medicare was not the primary or secondary payer, we used the primary payer to identify Medicaid, privately insured, and uninsured patients aged 18 to 64 years. None of the states expanded Medicaid coverage during the years studied.

The primary outcome of interest was the rate of having 1 or more all-cause, unplanned return(s) to an acute care hospital within 30 days of discharge after an index admission for AMI, HF, and pneumonia as defined by a modified version of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ readmission metrics.21,22 We examined total return rates as well as rates for inpatient, observation, and ED care. We also examined the leading diagnoses associated with returns to the hospital. For each index admission, we included only 1 return visit, giving priority to inpatient readmissions, then observation visits, and then ED visits.

The HCUP databases are consistent with the definition of limited data sets under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Privacy Rule and contain no direct patient identifiers. The AHRQ Institutional Review Board considers research using HCUP data to have exempt status.

Statistical Analysis

To compare rates at which patients returned to the hospital during 2 cohort periods (2009 and 2010 vs 2013 and 2014), we used coarsened exact matching, a well-established matching technique for balancing covariates between 2 populations of patients that may be related to the outcome.23 For observational datasets, coarsened exact matching is preferable to traditional matching because it enables the investigator to assess balance between the 2 populations, select the desired degree of balance, and eliminate observations for which comparable matches cannot be found.

We assembled sets of index admissions in each study period that were similar with respect to payer, primary diagnosis, and other factors. Matching variables included the patient’s age group, sex, and Elixhauser Comorbidity Index24 (in deciles), as well as the hospital’s ratio of observation visits relative to inpatient admissions in 2009 and 2010 combined (in quartiles; see supplementary Appendix). For Medicare beneficiaries, we also matched on dual enrollment in Medicaid.

We conducted the matching process separately for each target condition and payer population. First, we grouped index admissions in both periods into strata defined by all possible combinations of the matching variables and allowing one-to-many random matching within strata. We then dropped records in any strata for which there were no records in 1 of the time periods. Finally, we calculated weights based on the size of each stratum. We used these weights to account for the different numbers of index admissions in each stratum between the 2 study periods. For example, if a stratum contained 10 index admissions in 2009 and 2010 combined and 20 in 2013 and 2014 combined, an admission weighed double in the earlier period. After weighting, the index admissions in each period (2009 and 2010; 2013 and 2014) had similar characteristics (Table 1).

RESULTS

There were 423,503 eligible index admissions for AMI, HF, and pneumonia in the 2 periods combined; 422,840 (99.8%) were successfully matched and included in this analysis. After matching weights were applied, there were few statistically significant differences across the 2 time periods (see Table 1 and supplementary Appendix).

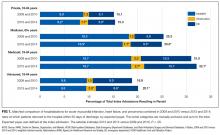

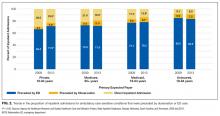

From 2009 and 2010 to 2013 and 2014, the percentage of patients hospitalized for AMI, HF, and pneumonia who had only observation or ED visits when they returned to the hospital increased from 41.4% to 46.7% among patients with private insurance (P < 0.001), from 27.8% to 32.1% among older patients with Medicare (P < 0.001), from 39.5% to 41.8% among patients with Medicaid (P = 0.03), and from 49.2% to 52.8% among patients without insurance (P = 0.004; Table 1). The percentage of returns to the hospital for observation increased across all payers (P < 0.001); in 2013 and 2014 combined, observation visits ranged from 6.8% of hospital returns among patients with Medicare to 11.1% among patients with private insurance. The percentage of returns to the hospital for an ED visit increased among patients with private insurance (P = 0.02) and Medicare (P < 0.001); in 2013 and 2014, ED visits ranged from 25.3% of returns to the hospital among patients with Medicare to 42.9% among uninsured patients.

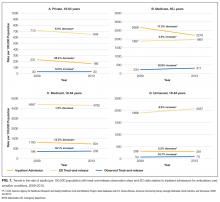

The increases in 30-day observation and ED visits coincided with reductions in inpatient readmissions among patients with private insurance and Medicare and contributed to growth in total returns to the hospital among patients with Medicaid or no insurance (Figure 1).

Figure 2

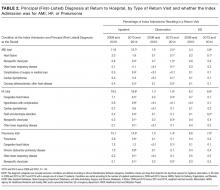

Patients initially hospitalized for HF and pneumonia who returned to the hospital within 30 days often returned for the same conditions (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Matching index admissions for AMI, HF, or pneumonia in 201 hospitals in 2009 and 2010 with those in 2013 and 2014, we observed that increases in observation and ED visits coincided with reductions in inpatient readmissions among patients with private insurance and Medicare and contributed to growth in total returns to the hospital among patients with Medicaid or no insurance. Among patients with private insurance and Medicare, inpatient readmissions declined significantly for all 3 target conditions, but total returns to the hospital remained constant for AMI and HF, rose for privately insured patients with pneumonia, and declined modestly for Medicare patients with pneumonia. Inpatient readmissions were unchanged for adults aged 18 to 64 years with Medicaid or no insurance, but total returns to the hospital increased significantly, reaching 32% among those with Medicaid.

These findings add to recent literature, which has primarily emphasized inpatient readmissions among Medicare beneficiaries with several exceptions. A prior analysis indicates that readmissions have declined among diverse payer populations nationally.18 Gerhardt et al25 found that from 2011 to 2012, all-cause 30-day readmissions declined among fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare beneficiaries following any index admission, while ED revisits remained stable and observation revisits increased slightly. Evaluating the CMS Hospital Readmission Reductions Program (HRRP), Zuckerman et al17 reported that from 2007 to 2015, inpatient readmissions declined among FFS Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older who were hospitalized with AMI, HF, or pneumonia, while returns to the hospital for observation rose approximately 2%; ED visits were not included. We found that Medicare (FFS and Medicare Advantage) patients with AMI and HF returned to the hospital with the same frequency in 2009 and 2010 as in 2013 and 2014, and those patients with pneumonia returned slightly less often. In aggregate, declines in inpatient readmissions in the 4 states we studied coincided with increases in observation and ED care. Moreover, these shifts occurred not only among Medicare beneficiaries but also among privately insured adults, Medicaid recipients, and the uninsured.

Three factors may have contributed to these apparent shifts from readmissions to observation and ED visits. First, some authors have suggested that hospitals may reduce readmissions by intentionally placing some of the patients who return to the hospital under observation instead of admitting them.17,26 If true, hospitals with greater declines in readmissions would have larger increases in observation revisits. Zuckerman et al17 found no correlation among Medicare beneficiaries between hospital-level trends in observation revisits and readmissions, but returns to observation rose more rapidly for AMI, HF, and pneumonia (compared with other conditions) during long term follow-up than during the HRRP implementation period. Other authors have documented that declines in readmissions have been greatest at hospitals with the highest baseline readmission rates,27,28 and hospitals with lower readmission rates have more observation return visits.29

Second, shifts from inpatient readmissions to return visits for observation may reflect unintentional rather than intentional changes in the services provided. Clinical practice patterns are evolving such that patients who present to the hospital for acute care increasingly are placed under observation or discharged from the ED instead of being admitted, regardless of whether they recently were hospitalized.30 Inpatient admissions, which are strongly correlated with readmission rates,28,31 are declining nationally,32 and both observation and ED visits are rising.33-35 Although little is known about effects on health outcomes and patient out-of-pocket costs,shifts from inpatient admissions to observation and ED visits reduce costs to payers.36,37

Third, instead of substitution, more patients may be returning for lower-acuity conditions that can be treated in the ED or under observation. Hospitals are implementing diverse and multifaceted interventions to reduce readmissions that can involve assessing patient needs and the risk for readmission, educating patients about self-care and risks after discharge, reconciling medication, scheduling follow-up visits, and monitoring patients through telephone calls and home nursing visits.26,38,39 Although the intent may be to reduce patients’ need to return to the hospital, interventions that educate patients about risks after discharge may lower the threshold at which they find symptoms worrisome enough to return. This could increase lower-acuity return visits. We found that reasons for returning were similar in 2009 and 2010 versus 2013 and 2014, but we did not examine acuity of illness at the time of return.

Other areas of concern are the high rates at which Medicaid patients are returning to the hospital and the increases in rates of returns among Medicaid patients and the uninsured. Individuals in these disadvantaged populations may be having difficulty accessing ambulatory care or may be turning to the ED more often for lower acuity problems that arise after discharge. In 3 of the 4 states we studied, 15% to 16% of adults live in poverty and 10% to 30% live in primary care health professional shortage areas.40,41 Given the implications for patient outcomes and costs, trends among these populations warrant further scrutiny.42,43

This analysis has several limitations. Data were from 4 states, but trends in readmissions are similar nationally. From 2010 through 2015, the all-condition readmission rate declined by 8% among Medicare beneficiaries nationally and by 6.1% in South Carolina, 7.4% in Georgia, 8.3% in Nebraska, and 8.7% in Tennessee.44 We report trends across hospitals and did not examine hospital-level revisits. Therefore, further research is needed to determine whether these findings are related to co-occurring trends, intentional substitution, or other factors.

In conclusion, measuring inpatient readmissions without accounting for return visits to the ED and observation underestimates the rate at which patients return to the hospital following an inpatient hospitalization. Because of growth in observation and ED visits, trends in the total rates at which patients return to the hospital can differ from trends in inpatient readmissions. In the 4 states we studied, total return rates were particularly high and rising among patients with Medicaid and lower, but also rising, among the uninsured. Policy analysts and researchers should investigate the factors contributing to growth in readmissions in these vulnerable populations and determine whether similar trends are occurring nationwide. Hospitalists play critical roles in admitting and discharging inpatients, caring for patients under observation, and implementing quality improvement programs. Irrespective of payer, hospitalists’ efforts to improve the quality and value of care should include observation and ED visits as well as inpatient readmissions.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Minya Sheng, M.S. (Truven Health Analytics) for assistance in programming and data management and Linda Lee, Ph.D. (Truven Health Analytics) for providing editorial review of the manuscript. We also wish to acknowledge the 4 HCUP Partner organizations that contributed to the HCUP State Databases used in this study: Georgia Hospital Association, Nebraska Hospital Association, South Carolina Revenue and Fiscal Affairs Office, and Tennessee Hospital Association.

Disclosure

Funding for this study was provided by the AHRQ Center for Delivery, Organization, and Markets, HCUP (Contract No. HHSA-290-2013-00002-C). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the AHRQ or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures to declare.

1. Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418-1428. PubMed

2. Lum HD, Studenski SA, Degenholtz HB, Hardy SE. Early hospital readmission is a predictor of one-year mortality in community-dwelling older Medicare beneficiaries. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(11):1467-1474. PubMed

3. Peach State Health Plan. New Peach State Health Plan 30-Day Readmission Payment Policy. https://www.pshpgeorgia.com/newsroom/30-day-readmission-payment-policy.html . Accessed September 26, 2017.

4. Axon RN, Cole L, Moonan A, et al. Evolution and Initial Experience of a Statewide Care Transitions Quality Improvement Collaborative: Preventing Avoidable Readmissions Together. Popul Health Manag. 2016 Feb;19(1):4-10. PubMed

5. Nebraska Hospital Association. Quality and Safety. http://www.nebraskahospitals.org/quality_and_safety/qs_home.html. Accessed July 25, 2017.

6. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Re-Engineered Discharge (RED) Toolkit. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/systems/hospital/red/toolkit/index.html. Accessed July 25, 2017.

7. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Readmissions. http://www.ihi.org/Topics/Readmissions/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed July 25, 2017.

8. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP). https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html. Accessed July 19, 2016.

9. Polinski JM, Moore JM, Kyrychenko P, et al. An insurer’s care transition program emphasizes medication reconciliation, reduces readmissions and costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(7):1222-1229. PubMed

10. BlueCross BlueShield. Highmark’s Quality Blue Program helps hospitals reduce readmissions and infections for members. http://www.bcbs.com/healthcare-news/plans/highmark-quality-blue-program-helps-hospitals-reduce-readmissions-and-infections-for-members.html. Accessed November 7, 2016.

11. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Designing and delivering whole-person transitional care: the hospital guide to reducing Medicaid readmissions. Rockville, MD: AHRQ; September 2016. AHRQ Pub. No. 16-0047-EF. http://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/systems/hospital/medicaidreadmitguide/medicaidreadmissions.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2017.

12. Aetna. Aetna, Genesis HealthCare take aim at preventing hospital readmissions. https://news.aetna.com/news-releases/aetna-genesis-healthcare-take-aim-at-preventing-hospital-readmissions/. Accessed November 7, 2016.

13. Molina Healthcare. Medical Management Program.http://www.molinahealthcare.com/providers/wi/medicaid/manual/PDF/manual_WI_19_Medical_Management.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2017.

14. Kaiser Family Foundation. Total Medicaid MCOs. State health facts, 2016. http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-medicaid-mcos/. Accessed July 19, 2016.

15. Muhlestein D, McClellan M. Accountable care organizations in 2016: private and public-sector growth and dispersion. Health Affairs blog. April 21, 2016. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2016/04/21/accountable-care-organizations-in-2016-private-and-public-sector-growth-and-dispersion/. Accessed November 7, 2016.

16. Leppin AL, Gionfriddo MR, Kessler M, et al. Preventing 30-day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1095-1107. PubMed

17. Zuckerman RB, Sheingold SH, Orav EJ, Ruhter J, Epstein AM. Readmissions, observation, and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(16):1543-1551. PubMed

18. Fingar KR, Washington R. Trends in hospital readmissions for four high-volume conditions, 2009–2013. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; November 2015. Statistical Brief No. 196. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb196-Readmissions-Trends-High-Volume-Conditions.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2017.

19. Ross MA, Hockenberry JM, Mutter R, Barrett M, Wheatley M, Pitts SR. Protocol-driven emergency department observation units offer savings, shorter stays, and reduced admissions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(12):2149-2156. PubMed

20. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). HCUP Databases. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; November 2016. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/databases.jsp. Accessed March 15, 2017.

21. QualityNet. Archived resources: readmission measures and measure methodology. https://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?cid=1228774371008&pagename=QnetPublic%2FPage%2FQnetTier4&c=Page. Accessed November 7, 2016.

22. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2014 measures updates and specifications report: hospital-level 30-day risk-standardized readmission measures: acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke. March 2014. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/Measure-Methodology.html. Accessed September 26, 2017.

23. Iacus SM, King G, Porro G. Causal inference without balance checking: coarsened exact matching. Political Analysis. 2012;20(1):1-24.

24. Moore BJ, White S, Washington R, Coenen N, Elixhauser A. Identifying increased risk of readmission and in-hospital mortality using hospital administrative data: The AHRQ Elixhauser Comorbidity Index. Med Care. 2017;55(7):698-705. PubMed

25. Gerhardt G, Yemane A, Apostle K, Oelschlaeger A, Rollins E, Brennan N. Evaluating whether changes in utilization of hospital outpatient services contributed to lower Medicare readmission rate. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2014;4(1):mmrr2014.004.01.b03. PubMed

26. Kripalani S, Theobald CN, Anctil B, Vasilevskis EE. Reducing hospital readmission rates: current strategies and future directions. Annu Rev Med. 2014;65:471-485. PubMed

27. Desai NR, Ross JS, Kwon JY, et al. Association between hospital penalty status under the hospital readmission reduction program and readmission rates for target and nontarget conditions. JAMA. 2016;316(24):2647-2656. PubMed

28. Epstein AM, Jha AK, Orav EJ. The relationship between hospital admission rates and rehospitalizations. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(24):2287-2295. PubMed

29. Venkatesh AK, Wang C, Ross JS, et al. Hospital use of observation stays: cross sectional study of the impact on readmission rates. Med Care. 2016;54(12)1070-1077. PubMed

30. Nuckols TK, Fingar KR, Barrett M, Steiner CA, Stocks C, Owens PL. The shifting landscape in utilization of inpatient, observation, and emergency department Services Across Payers. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(6):443-446. PubMed

31. Dharmarajan K, Qin L, Lin Z, et al. Declining admission rates and thirty-day readmission rates positively associated even though patients grew sicker over time. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(7):1294-1302. PubMed

32. Grube M, Kaufman K, York R. Decline in utilization rates signals a change in the inpatient business model. Health Affairs blog. March 8, 2013. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2013/03/08/decline-in-utilization-rates-signals-a-change-in-the-inpatient-business-model/. Accessed November 7, 2016.

33. Feng Z, Wright B, Mor V. Sharp rise in Medicare enrollees being held in hospitals for observation raises concerns about causes and consequences. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(6):1251-1259. PubMed

34. Venkatesh AK, Geisler BP, Gibson Chambers JJ, et al. Use of observation care in US emergency departments, 2001 to 2008. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24326. PubMed

35. Schuur JD, Venkatesh AK. The growing role of emergency departments in hospital admissions. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):391-393. PubMed

36. Kangovi S, Cafardi SG, Smith RA, Kulkarni R, Grande D. Patient financial responsibility for observation care. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(11):718-723. PubMed

37. Doyle BJ, Ettner SL, Nuckols TK. Supplemental insurance reduces out-of-pocket costs in Medicare observation services. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(7):502-504. doi:10.1002/jhm.2588. PubMed

38. Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520-528. PubMed

39. Bradley EH, Curry L, Horwitz LI, et al. Hospital strategies associated with 30-day readmission rates for patients with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(4):444-450. PubMed

40. US Census Bureau. American Fact Finder: community facts. http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml. Accessed November 1, 2016.

41. Van Vleet A, Paradise J. Tapping nurse practitioners to meet rising demand for primary care. Kaiser Family Foundation Issue Brief. January 20, 2015. http://kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/tapping-nurse-practitioners-to-meet-rising-demand-for-primary-care/. Accessed November 7, 2016.

42. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Hospital guide to reducing Medicaid readmissions. Rockville, MD: AHRQ; August 2014. AHRQ Publication No. 14-0050-EF. http://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/publications/files/medreadmissions.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2017.

43. Boccuti C, Casillas G. Aiming for fewer hospital U-turns: The Medicare Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. Kaiser Family Foundation Issue Brief. March 10, 2017. http://kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/aiming-for-fewer-hospital-u-turns-the-medicare-hospital-readmission-reduction-program/. Accessed November 7, 2016.

44. Conway P, Gronniger T. New data: 49 states plus DC reduce avoidable hospital readmissions. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services blog. September 13, 2016. http://medtecheng.com/new-data-49-states-plus-dc-reduce-avoidable-hospital-readmissions/. Accessed September 26, 2017.

Given the frequency, potential preventability, and costs associated with hospital readmissions, reducing readmissions is a priority in efforts to improve the quality and value of healthcare.1,2 State and national bodies have created diverse initiatives to facilitate improvements in hospital discharge practices and reduce 30-day readmission rates across payers.3-5 For example, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement have published tools for improving discharge practices.6,7 Medicare instituted financial penalties for hospitals with higher-than-expected readmission rates for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure (HF), and pneumonia in 2012, while private payers and Medicaid programs have established their own policies.8-13 Furthermore, private payers and Medicaid programs shifted toward capitated and value-based reimbursement models in which readmissions lead to financial losses for hospitals.14,15 Accordingly, hospitals have implemented diverse interventions to reduce readmissions.16,17 From 2009 to 2013, 30-day readmissions declined among privately insured adults (from 12.4% to 11.7%), Medicare patients (from 22.0% to 20.0%), and uninsured individuals (11.5% to 11.0%) but climbed among patients with Medicaid (from 19.8% to 20.5%) after index admissions for AMI, HF, pneumonia, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.18

To date, research, policies, and quality improvement interventions have largely focused on improvements to one aspect of the system of care—that provided in the inpatient setting—among older adults with Medicare. Yet, inpatient readmissions may underestimate how often patients return to the hospital because patients can be placed under observation or stabilized and discharged from the emergency department (ED) instead of being readmitted. Observation and ED visits are less costly to payers than inpatient admissions.19 Thus, information about utilization of inpatient, observation, and ED visits within 30 days of hospital discharge may be more informative than inpatient readmissions alone. However, little is known about trends in returns to the hospital for observation and ED visits and whether such trends vary by payer.

Our objective was to assess whether changes have occurred in rates of total 30-day, all-cause, unplanned returns to the hospital among adults with index admissions for AMI, HF, and pneumonia in which returns to the hospital included inpatient readmissions, observation visits, and ED visits. We also assessed whether changes in the rate of hospital inpatient readmissions coincided with changes in rates of returns for ED or observation visits. To examine the effects of readmission policies implemented by diverse payers and broad changes to the health system following the Affordable Care Act, we compared data from 201 hospitals in 4 states in 2009 and 2010 with data from the same hospitals for 2013 and 2014.

METHODS

Data Sources, Populations, and Study Variables

We used Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) State Inpatient Databases, State Emergency Department Databases, and State Ambulatory Surgery and Services Databases from Georgia, Nebraska, South Carolina, and Tennessee. These states comprise 7% of the US population and were the only states with data that included all observation and ED visits as well as encrypted patient identification numbers that permitted linkage across facilities and hospitals.20

Index admissions for patients aged 18 years and older were eligible if they occurred at nonfederal general medical/surgical hospitals (excluding critical access hospitals) that had at least 1 index admission per target condition per year and at least 5 inpatient, observation, and ED visits for any condition per year.

We classified patients into the following 4 populations by age and insurance coverage: 18 to 64 years with private insurance, 65 years and older with Medicare (excluding younger adults with Medicare), 18 to 64 years with Medicaid, and 18 to 64 years without insurance. We identified patients aged 65 years and older with Medicare by using the primary or secondary expected payer for the index admission. This group included patients who were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. If Medicare was not the primary or secondary payer, we used the primary payer to identify Medicaid, privately insured, and uninsured patients aged 18 to 64 years. None of the states expanded Medicaid coverage during the years studied.

The primary outcome of interest was the rate of having 1 or more all-cause, unplanned return(s) to an acute care hospital within 30 days of discharge after an index admission for AMI, HF, and pneumonia as defined by a modified version of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ readmission metrics.21,22 We examined total return rates as well as rates for inpatient, observation, and ED care. We also examined the leading diagnoses associated with returns to the hospital. For each index admission, we included only 1 return visit, giving priority to inpatient readmissions, then observation visits, and then ED visits.

The HCUP databases are consistent with the definition of limited data sets under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Privacy Rule and contain no direct patient identifiers. The AHRQ Institutional Review Board considers research using HCUP data to have exempt status.

Statistical Analysis

To compare rates at which patients returned to the hospital during 2 cohort periods (2009 and 2010 vs 2013 and 2014), we used coarsened exact matching, a well-established matching technique for balancing covariates between 2 populations of patients that may be related to the outcome.23 For observational datasets, coarsened exact matching is preferable to traditional matching because it enables the investigator to assess balance between the 2 populations, select the desired degree of balance, and eliminate observations for which comparable matches cannot be found.

We assembled sets of index admissions in each study period that were similar with respect to payer, primary diagnosis, and other factors. Matching variables included the patient’s age group, sex, and Elixhauser Comorbidity Index24 (in deciles), as well as the hospital’s ratio of observation visits relative to inpatient admissions in 2009 and 2010 combined (in quartiles; see supplementary Appendix). For Medicare beneficiaries, we also matched on dual enrollment in Medicaid.

We conducted the matching process separately for each target condition and payer population. First, we grouped index admissions in both periods into strata defined by all possible combinations of the matching variables and allowing one-to-many random matching within strata. We then dropped records in any strata for which there were no records in 1 of the time periods. Finally, we calculated weights based on the size of each stratum. We used these weights to account for the different numbers of index admissions in each stratum between the 2 study periods. For example, if a stratum contained 10 index admissions in 2009 and 2010 combined and 20 in 2013 and 2014 combined, an admission weighed double in the earlier period. After weighting, the index admissions in each period (2009 and 2010; 2013 and 2014) had similar characteristics (Table 1).

RESULTS

There were 423,503 eligible index admissions for AMI, HF, and pneumonia in the 2 periods combined; 422,840 (99.8%) were successfully matched and included in this analysis. After matching weights were applied, there were few statistically significant differences across the 2 time periods (see Table 1 and supplementary Appendix).

From 2009 and 2010 to 2013 and 2014, the percentage of patients hospitalized for AMI, HF, and pneumonia who had only observation or ED visits when they returned to the hospital increased from 41.4% to 46.7% among patients with private insurance (P < 0.001), from 27.8% to 32.1% among older patients with Medicare (P < 0.001), from 39.5% to 41.8% among patients with Medicaid (P = 0.03), and from 49.2% to 52.8% among patients without insurance (P = 0.004; Table 1). The percentage of returns to the hospital for observation increased across all payers (P < 0.001); in 2013 and 2014 combined, observation visits ranged from 6.8% of hospital returns among patients with Medicare to 11.1% among patients with private insurance. The percentage of returns to the hospital for an ED visit increased among patients with private insurance (P = 0.02) and Medicare (P < 0.001); in 2013 and 2014, ED visits ranged from 25.3% of returns to the hospital among patients with Medicare to 42.9% among uninsured patients.

The increases in 30-day observation and ED visits coincided with reductions in inpatient readmissions among patients with private insurance and Medicare and contributed to growth in total returns to the hospital among patients with Medicaid or no insurance (Figure 1).

Figure 2

Patients initially hospitalized for HF and pneumonia who returned to the hospital within 30 days often returned for the same conditions (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Matching index admissions for AMI, HF, or pneumonia in 201 hospitals in 2009 and 2010 with those in 2013 and 2014, we observed that increases in observation and ED visits coincided with reductions in inpatient readmissions among patients with private insurance and Medicare and contributed to growth in total returns to the hospital among patients with Medicaid or no insurance. Among patients with private insurance and Medicare, inpatient readmissions declined significantly for all 3 target conditions, but total returns to the hospital remained constant for AMI and HF, rose for privately insured patients with pneumonia, and declined modestly for Medicare patients with pneumonia. Inpatient readmissions were unchanged for adults aged 18 to 64 years with Medicaid or no insurance, but total returns to the hospital increased significantly, reaching 32% among those with Medicaid.

These findings add to recent literature, which has primarily emphasized inpatient readmissions among Medicare beneficiaries with several exceptions. A prior analysis indicates that readmissions have declined among diverse payer populations nationally.18 Gerhardt et al25 found that from 2011 to 2012, all-cause 30-day readmissions declined among fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare beneficiaries following any index admission, while ED revisits remained stable and observation revisits increased slightly. Evaluating the CMS Hospital Readmission Reductions Program (HRRP), Zuckerman et al17 reported that from 2007 to 2015, inpatient readmissions declined among FFS Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older who were hospitalized with AMI, HF, or pneumonia, while returns to the hospital for observation rose approximately 2%; ED visits were not included. We found that Medicare (FFS and Medicare Advantage) patients with AMI and HF returned to the hospital with the same frequency in 2009 and 2010 as in 2013 and 2014, and those patients with pneumonia returned slightly less often. In aggregate, declines in inpatient readmissions in the 4 states we studied coincided with increases in observation and ED care. Moreover, these shifts occurred not only among Medicare beneficiaries but also among privately insured adults, Medicaid recipients, and the uninsured.

Three factors may have contributed to these apparent shifts from readmissions to observation and ED visits. First, some authors have suggested that hospitals may reduce readmissions by intentionally placing some of the patients who return to the hospital under observation instead of admitting them.17,26 If true, hospitals with greater declines in readmissions would have larger increases in observation revisits. Zuckerman et al17 found no correlation among Medicare beneficiaries between hospital-level trends in observation revisits and readmissions, but returns to observation rose more rapidly for AMI, HF, and pneumonia (compared with other conditions) during long term follow-up than during the HRRP implementation period. Other authors have documented that declines in readmissions have been greatest at hospitals with the highest baseline readmission rates,27,28 and hospitals with lower readmission rates have more observation return visits.29

Second, shifts from inpatient readmissions to return visits for observation may reflect unintentional rather than intentional changes in the services provided. Clinical practice patterns are evolving such that patients who present to the hospital for acute care increasingly are placed under observation or discharged from the ED instead of being admitted, regardless of whether they recently were hospitalized.30 Inpatient admissions, which are strongly correlated with readmission rates,28,31 are declining nationally,32 and both observation and ED visits are rising.33-35 Although little is known about effects on health outcomes and patient out-of-pocket costs,shifts from inpatient admissions to observation and ED visits reduce costs to payers.36,37

Third, instead of substitution, more patients may be returning for lower-acuity conditions that can be treated in the ED or under observation. Hospitals are implementing diverse and multifaceted interventions to reduce readmissions that can involve assessing patient needs and the risk for readmission, educating patients about self-care and risks after discharge, reconciling medication, scheduling follow-up visits, and monitoring patients through telephone calls and home nursing visits.26,38,39 Although the intent may be to reduce patients’ need to return to the hospital, interventions that educate patients about risks after discharge may lower the threshold at which they find symptoms worrisome enough to return. This could increase lower-acuity return visits. We found that reasons for returning were similar in 2009 and 2010 versus 2013 and 2014, but we did not examine acuity of illness at the time of return.

Other areas of concern are the high rates at which Medicaid patients are returning to the hospital and the increases in rates of returns among Medicaid patients and the uninsured. Individuals in these disadvantaged populations may be having difficulty accessing ambulatory care or may be turning to the ED more often for lower acuity problems that arise after discharge. In 3 of the 4 states we studied, 15% to 16% of adults live in poverty and 10% to 30% live in primary care health professional shortage areas.40,41 Given the implications for patient outcomes and costs, trends among these populations warrant further scrutiny.42,43

This analysis has several limitations. Data were from 4 states, but trends in readmissions are similar nationally. From 2010 through 2015, the all-condition readmission rate declined by 8% among Medicare beneficiaries nationally and by 6.1% in South Carolina, 7.4% in Georgia, 8.3% in Nebraska, and 8.7% in Tennessee.44 We report trends across hospitals and did not examine hospital-level revisits. Therefore, further research is needed to determine whether these findings are related to co-occurring trends, intentional substitution, or other factors.

In conclusion, measuring inpatient readmissions without accounting for return visits to the ED and observation underestimates the rate at which patients return to the hospital following an inpatient hospitalization. Because of growth in observation and ED visits, trends in the total rates at which patients return to the hospital can differ from trends in inpatient readmissions. In the 4 states we studied, total return rates were particularly high and rising among patients with Medicaid and lower, but also rising, among the uninsured. Policy analysts and researchers should investigate the factors contributing to growth in readmissions in these vulnerable populations and determine whether similar trends are occurring nationwide. Hospitalists play critical roles in admitting and discharging inpatients, caring for patients under observation, and implementing quality improvement programs. Irrespective of payer, hospitalists’ efforts to improve the quality and value of care should include observation and ED visits as well as inpatient readmissions.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Minya Sheng, M.S. (Truven Health Analytics) for assistance in programming and data management and Linda Lee, Ph.D. (Truven Health Analytics) for providing editorial review of the manuscript. We also wish to acknowledge the 4 HCUP Partner organizations that contributed to the HCUP State Databases used in this study: Georgia Hospital Association, Nebraska Hospital Association, South Carolina Revenue and Fiscal Affairs Office, and Tennessee Hospital Association.

Disclosure

Funding for this study was provided by the AHRQ Center for Delivery, Organization, and Markets, HCUP (Contract No. HHSA-290-2013-00002-C). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the AHRQ or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures to declare.

Given the frequency, potential preventability, and costs associated with hospital readmissions, reducing readmissions is a priority in efforts to improve the quality and value of healthcare.1,2 State and national bodies have created diverse initiatives to facilitate improvements in hospital discharge practices and reduce 30-day readmission rates across payers.3-5 For example, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement have published tools for improving discharge practices.6,7 Medicare instituted financial penalties for hospitals with higher-than-expected readmission rates for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure (HF), and pneumonia in 2012, while private payers and Medicaid programs have established their own policies.8-13 Furthermore, private payers and Medicaid programs shifted toward capitated and value-based reimbursement models in which readmissions lead to financial losses for hospitals.14,15 Accordingly, hospitals have implemented diverse interventions to reduce readmissions.16,17 From 2009 to 2013, 30-day readmissions declined among privately insured adults (from 12.4% to 11.7%), Medicare patients (from 22.0% to 20.0%), and uninsured individuals (11.5% to 11.0%) but climbed among patients with Medicaid (from 19.8% to 20.5%) after index admissions for AMI, HF, pneumonia, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.18

To date, research, policies, and quality improvement interventions have largely focused on improvements to one aspect of the system of care—that provided in the inpatient setting—among older adults with Medicare. Yet, inpatient readmissions may underestimate how often patients return to the hospital because patients can be placed under observation or stabilized and discharged from the emergency department (ED) instead of being readmitted. Observation and ED visits are less costly to payers than inpatient admissions.19 Thus, information about utilization of inpatient, observation, and ED visits within 30 days of hospital discharge may be more informative than inpatient readmissions alone. However, little is known about trends in returns to the hospital for observation and ED visits and whether such trends vary by payer.

Our objective was to assess whether changes have occurred in rates of total 30-day, all-cause, unplanned returns to the hospital among adults with index admissions for AMI, HF, and pneumonia in which returns to the hospital included inpatient readmissions, observation visits, and ED visits. We also assessed whether changes in the rate of hospital inpatient readmissions coincided with changes in rates of returns for ED or observation visits. To examine the effects of readmission policies implemented by diverse payers and broad changes to the health system following the Affordable Care Act, we compared data from 201 hospitals in 4 states in 2009 and 2010 with data from the same hospitals for 2013 and 2014.

METHODS

Data Sources, Populations, and Study Variables

We used Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) State Inpatient Databases, State Emergency Department Databases, and State Ambulatory Surgery and Services Databases from Georgia, Nebraska, South Carolina, and Tennessee. These states comprise 7% of the US population and were the only states with data that included all observation and ED visits as well as encrypted patient identification numbers that permitted linkage across facilities and hospitals.20

Index admissions for patients aged 18 years and older were eligible if they occurred at nonfederal general medical/surgical hospitals (excluding critical access hospitals) that had at least 1 index admission per target condition per year and at least 5 inpatient, observation, and ED visits for any condition per year.

We classified patients into the following 4 populations by age and insurance coverage: 18 to 64 years with private insurance, 65 years and older with Medicare (excluding younger adults with Medicare), 18 to 64 years with Medicaid, and 18 to 64 years without insurance. We identified patients aged 65 years and older with Medicare by using the primary or secondary expected payer for the index admission. This group included patients who were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. If Medicare was not the primary or secondary payer, we used the primary payer to identify Medicaid, privately insured, and uninsured patients aged 18 to 64 years. None of the states expanded Medicaid coverage during the years studied.

The primary outcome of interest was the rate of having 1 or more all-cause, unplanned return(s) to an acute care hospital within 30 days of discharge after an index admission for AMI, HF, and pneumonia as defined by a modified version of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ readmission metrics.21,22 We examined total return rates as well as rates for inpatient, observation, and ED care. We also examined the leading diagnoses associated with returns to the hospital. For each index admission, we included only 1 return visit, giving priority to inpatient readmissions, then observation visits, and then ED visits.

The HCUP databases are consistent with the definition of limited data sets under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Privacy Rule and contain no direct patient identifiers. The AHRQ Institutional Review Board considers research using HCUP data to have exempt status.

Statistical Analysis

To compare rates at which patients returned to the hospital during 2 cohort periods (2009 and 2010 vs 2013 and 2014), we used coarsened exact matching, a well-established matching technique for balancing covariates between 2 populations of patients that may be related to the outcome.23 For observational datasets, coarsened exact matching is preferable to traditional matching because it enables the investigator to assess balance between the 2 populations, select the desired degree of balance, and eliminate observations for which comparable matches cannot be found.

We assembled sets of index admissions in each study period that were similar with respect to payer, primary diagnosis, and other factors. Matching variables included the patient’s age group, sex, and Elixhauser Comorbidity Index24 (in deciles), as well as the hospital’s ratio of observation visits relative to inpatient admissions in 2009 and 2010 combined (in quartiles; see supplementary Appendix). For Medicare beneficiaries, we also matched on dual enrollment in Medicaid.

We conducted the matching process separately for each target condition and payer population. First, we grouped index admissions in both periods into strata defined by all possible combinations of the matching variables and allowing one-to-many random matching within strata. We then dropped records in any strata for which there were no records in 1 of the time periods. Finally, we calculated weights based on the size of each stratum. We used these weights to account for the different numbers of index admissions in each stratum between the 2 study periods. For example, if a stratum contained 10 index admissions in 2009 and 2010 combined and 20 in 2013 and 2014 combined, an admission weighed double in the earlier period. After weighting, the index admissions in each period (2009 and 2010; 2013 and 2014) had similar characteristics (Table 1).

RESULTS

There were 423,503 eligible index admissions for AMI, HF, and pneumonia in the 2 periods combined; 422,840 (99.8%) were successfully matched and included in this analysis. After matching weights were applied, there were few statistically significant differences across the 2 time periods (see Table 1 and supplementary Appendix).

From 2009 and 2010 to 2013 and 2014, the percentage of patients hospitalized for AMI, HF, and pneumonia who had only observation or ED visits when they returned to the hospital increased from 41.4% to 46.7% among patients with private insurance (P < 0.001), from 27.8% to 32.1% among older patients with Medicare (P < 0.001), from 39.5% to 41.8% among patients with Medicaid (P = 0.03), and from 49.2% to 52.8% among patients without insurance (P = 0.004; Table 1). The percentage of returns to the hospital for observation increased across all payers (P < 0.001); in 2013 and 2014 combined, observation visits ranged from 6.8% of hospital returns among patients with Medicare to 11.1% among patients with private insurance. The percentage of returns to the hospital for an ED visit increased among patients with private insurance (P = 0.02) and Medicare (P < 0.001); in 2013 and 2014, ED visits ranged from 25.3% of returns to the hospital among patients with Medicare to 42.9% among uninsured patients.

The increases in 30-day observation and ED visits coincided with reductions in inpatient readmissions among patients with private insurance and Medicare and contributed to growth in total returns to the hospital among patients with Medicaid or no insurance (Figure 1).

Figure 2

Patients initially hospitalized for HF and pneumonia who returned to the hospital within 30 days often returned for the same conditions (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Matching index admissions for AMI, HF, or pneumonia in 201 hospitals in 2009 and 2010 with those in 2013 and 2014, we observed that increases in observation and ED visits coincided with reductions in inpatient readmissions among patients with private insurance and Medicare and contributed to growth in total returns to the hospital among patients with Medicaid or no insurance. Among patients with private insurance and Medicare, inpatient readmissions declined significantly for all 3 target conditions, but total returns to the hospital remained constant for AMI and HF, rose for privately insured patients with pneumonia, and declined modestly for Medicare patients with pneumonia. Inpatient readmissions were unchanged for adults aged 18 to 64 years with Medicaid or no insurance, but total returns to the hospital increased significantly, reaching 32% among those with Medicaid.

These findings add to recent literature, which has primarily emphasized inpatient readmissions among Medicare beneficiaries with several exceptions. A prior analysis indicates that readmissions have declined among diverse payer populations nationally.18 Gerhardt et al25 found that from 2011 to 2012, all-cause 30-day readmissions declined among fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare beneficiaries following any index admission, while ED revisits remained stable and observation revisits increased slightly. Evaluating the CMS Hospital Readmission Reductions Program (HRRP), Zuckerman et al17 reported that from 2007 to 2015, inpatient readmissions declined among FFS Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older who were hospitalized with AMI, HF, or pneumonia, while returns to the hospital for observation rose approximately 2%; ED visits were not included. We found that Medicare (FFS and Medicare Advantage) patients with AMI and HF returned to the hospital with the same frequency in 2009 and 2010 as in 2013 and 2014, and those patients with pneumonia returned slightly less often. In aggregate, declines in inpatient readmissions in the 4 states we studied coincided with increases in observation and ED care. Moreover, these shifts occurred not only among Medicare beneficiaries but also among privately insured adults, Medicaid recipients, and the uninsured.

Three factors may have contributed to these apparent shifts from readmissions to observation and ED visits. First, some authors have suggested that hospitals may reduce readmissions by intentionally placing some of the patients who return to the hospital under observation instead of admitting them.17,26 If true, hospitals with greater declines in readmissions would have larger increases in observation revisits. Zuckerman et al17 found no correlation among Medicare beneficiaries between hospital-level trends in observation revisits and readmissions, but returns to observation rose more rapidly for AMI, HF, and pneumonia (compared with other conditions) during long term follow-up than during the HRRP implementation period. Other authors have documented that declines in readmissions have been greatest at hospitals with the highest baseline readmission rates,27,28 and hospitals with lower readmission rates have more observation return visits.29

Second, shifts from inpatient readmissions to return visits for observation may reflect unintentional rather than intentional changes in the services provided. Clinical practice patterns are evolving such that patients who present to the hospital for acute care increasingly are placed under observation or discharged from the ED instead of being admitted, regardless of whether they recently were hospitalized.30 Inpatient admissions, which are strongly correlated with readmission rates,28,31 are declining nationally,32 and both observation and ED visits are rising.33-35 Although little is known about effects on health outcomes and patient out-of-pocket costs,shifts from inpatient admissions to observation and ED visits reduce costs to payers.36,37

Third, instead of substitution, more patients may be returning for lower-acuity conditions that can be treated in the ED or under observation. Hospitals are implementing diverse and multifaceted interventions to reduce readmissions that can involve assessing patient needs and the risk for readmission, educating patients about self-care and risks after discharge, reconciling medication, scheduling follow-up visits, and monitoring patients through telephone calls and home nursing visits.26,38,39 Although the intent may be to reduce patients’ need to return to the hospital, interventions that educate patients about risks after discharge may lower the threshold at which they find symptoms worrisome enough to return. This could increase lower-acuity return visits. We found that reasons for returning were similar in 2009 and 2010 versus 2013 and 2014, but we did not examine acuity of illness at the time of return.

Other areas of concern are the high rates at which Medicaid patients are returning to the hospital and the increases in rates of returns among Medicaid patients and the uninsured. Individuals in these disadvantaged populations may be having difficulty accessing ambulatory care or may be turning to the ED more often for lower acuity problems that arise after discharge. In 3 of the 4 states we studied, 15% to 16% of adults live in poverty and 10% to 30% live in primary care health professional shortage areas.40,41 Given the implications for patient outcomes and costs, trends among these populations warrant further scrutiny.42,43

This analysis has several limitations. Data were from 4 states, but trends in readmissions are similar nationally. From 2010 through 2015, the all-condition readmission rate declined by 8% among Medicare beneficiaries nationally and by 6.1% in South Carolina, 7.4% in Georgia, 8.3% in Nebraska, and 8.7% in Tennessee.44 We report trends across hospitals and did not examine hospital-level revisits. Therefore, further research is needed to determine whether these findings are related to co-occurring trends, intentional substitution, or other factors.

In conclusion, measuring inpatient readmissions without accounting for return visits to the ED and observation underestimates the rate at which patients return to the hospital following an inpatient hospitalization. Because of growth in observation and ED visits, trends in the total rates at which patients return to the hospital can differ from trends in inpatient readmissions. In the 4 states we studied, total return rates were particularly high and rising among patients with Medicaid and lower, but also rising, among the uninsured. Policy analysts and researchers should investigate the factors contributing to growth in readmissions in these vulnerable populations and determine whether similar trends are occurring nationwide. Hospitalists play critical roles in admitting and discharging inpatients, caring for patients under observation, and implementing quality improvement programs. Irrespective of payer, hospitalists’ efforts to improve the quality and value of care should include observation and ED visits as well as inpatient readmissions.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Minya Sheng, M.S. (Truven Health Analytics) for assistance in programming and data management and Linda Lee, Ph.D. (Truven Health Analytics) for providing editorial review of the manuscript. We also wish to acknowledge the 4 HCUP Partner organizations that contributed to the HCUP State Databases used in this study: Georgia Hospital Association, Nebraska Hospital Association, South Carolina Revenue and Fiscal Affairs Office, and Tennessee Hospital Association.

Disclosure

Funding for this study was provided by the AHRQ Center for Delivery, Organization, and Markets, HCUP (Contract No. HHSA-290-2013-00002-C). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the AHRQ or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures to declare.

1. Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418-1428. PubMed

2. Lum HD, Studenski SA, Degenholtz HB, Hardy SE. Early hospital readmission is a predictor of one-year mortality in community-dwelling older Medicare beneficiaries. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(11):1467-1474. PubMed

3. Peach State Health Plan. New Peach State Health Plan 30-Day Readmission Payment Policy. https://www.pshpgeorgia.com/newsroom/30-day-readmission-payment-policy.html . Accessed September 26, 2017.

4. Axon RN, Cole L, Moonan A, et al. Evolution and Initial Experience of a Statewide Care Transitions Quality Improvement Collaborative: Preventing Avoidable Readmissions Together. Popul Health Manag. 2016 Feb;19(1):4-10. PubMed

5. Nebraska Hospital Association. Quality and Safety. http://www.nebraskahospitals.org/quality_and_safety/qs_home.html. Accessed July 25, 2017.

6. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Re-Engineered Discharge (RED) Toolkit. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/systems/hospital/red/toolkit/index.html. Accessed July 25, 2017.

7. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Readmissions. http://www.ihi.org/Topics/Readmissions/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed July 25, 2017.

8. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP). https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html. Accessed July 19, 2016.

9. Polinski JM, Moore JM, Kyrychenko P, et al. An insurer’s care transition program emphasizes medication reconciliation, reduces readmissions and costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(7):1222-1229. PubMed

10. BlueCross BlueShield. Highmark’s Quality Blue Program helps hospitals reduce readmissions and infections for members. http://www.bcbs.com/healthcare-news/plans/highmark-quality-blue-program-helps-hospitals-reduce-readmissions-and-infections-for-members.html. Accessed November 7, 2016.

11. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Designing and delivering whole-person transitional care: the hospital guide to reducing Medicaid readmissions. Rockville, MD: AHRQ; September 2016. AHRQ Pub. No. 16-0047-EF. http://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/systems/hospital/medicaidreadmitguide/medicaidreadmissions.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2017.

12. Aetna. Aetna, Genesis HealthCare take aim at preventing hospital readmissions. https://news.aetna.com/news-releases/aetna-genesis-healthcare-take-aim-at-preventing-hospital-readmissions/. Accessed November 7, 2016.

13. Molina Healthcare. Medical Management Program.http://www.molinahealthcare.com/providers/wi/medicaid/manual/PDF/manual_WI_19_Medical_Management.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2017.

14. Kaiser Family Foundation. Total Medicaid MCOs. State health facts, 2016. http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-medicaid-mcos/. Accessed July 19, 2016.

15. Muhlestein D, McClellan M. Accountable care organizations in 2016: private and public-sector growth and dispersion. Health Affairs blog. April 21, 2016. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2016/04/21/accountable-care-organizations-in-2016-private-and-public-sector-growth-and-dispersion/. Accessed November 7, 2016.

16. Leppin AL, Gionfriddo MR, Kessler M, et al. Preventing 30-day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1095-1107. PubMed

17. Zuckerman RB, Sheingold SH, Orav EJ, Ruhter J, Epstein AM. Readmissions, observation, and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(16):1543-1551. PubMed

18. Fingar KR, Washington R. Trends in hospital readmissions for four high-volume conditions, 2009–2013. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; November 2015. Statistical Brief No. 196. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb196-Readmissions-Trends-High-Volume-Conditions.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2017.

19. Ross MA, Hockenberry JM, Mutter R, Barrett M, Wheatley M, Pitts SR. Protocol-driven emergency department observation units offer savings, shorter stays, and reduced admissions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(12):2149-2156. PubMed

20. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). HCUP Databases. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; November 2016. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/databases.jsp. Accessed March 15, 2017.

21. QualityNet. Archived resources: readmission measures and measure methodology. https://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?cid=1228774371008&pagename=QnetPublic%2FPage%2FQnetTier4&c=Page. Accessed November 7, 2016.

22. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2014 measures updates and specifications report: hospital-level 30-day risk-standardized readmission measures: acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke. March 2014. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/Measure-Methodology.html. Accessed September 26, 2017.

23. Iacus SM, King G, Porro G. Causal inference without balance checking: coarsened exact matching. Political Analysis. 2012;20(1):1-24.

24. Moore BJ, White S, Washington R, Coenen N, Elixhauser A. Identifying increased risk of readmission and in-hospital mortality using hospital administrative data: The AHRQ Elixhauser Comorbidity Index. Med Care. 2017;55(7):698-705. PubMed

25. Gerhardt G, Yemane A, Apostle K, Oelschlaeger A, Rollins E, Brennan N. Evaluating whether changes in utilization of hospital outpatient services contributed to lower Medicare readmission rate. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2014;4(1):mmrr2014.004.01.b03. PubMed

26. Kripalani S, Theobald CN, Anctil B, Vasilevskis EE. Reducing hospital readmission rates: current strategies and future directions. Annu Rev Med. 2014;65:471-485. PubMed

27. Desai NR, Ross JS, Kwon JY, et al. Association between hospital penalty status under the hospital readmission reduction program and readmission rates for target and nontarget conditions. JAMA. 2016;316(24):2647-2656. PubMed

28. Epstein AM, Jha AK, Orav EJ. The relationship between hospital admission rates and rehospitalizations. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(24):2287-2295. PubMed

29. Venkatesh AK, Wang C, Ross JS, et al. Hospital use of observation stays: cross sectional study of the impact on readmission rates. Med Care. 2016;54(12)1070-1077. PubMed

30. Nuckols TK, Fingar KR, Barrett M, Steiner CA, Stocks C, Owens PL. The shifting landscape in utilization of inpatient, observation, and emergency department Services Across Payers. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(6):443-446. PubMed

31. Dharmarajan K, Qin L, Lin Z, et al. Declining admission rates and thirty-day readmission rates positively associated even though patients grew sicker over time. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(7):1294-1302. PubMed

32. Grube M, Kaufman K, York R. Decline in utilization rates signals a change in the inpatient business model. Health Affairs blog. March 8, 2013. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2013/03/08/decline-in-utilization-rates-signals-a-change-in-the-inpatient-business-model/. Accessed November 7, 2016.

33. Feng Z, Wright B, Mor V. Sharp rise in Medicare enrollees being held in hospitals for observation raises concerns about causes and consequences. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(6):1251-1259. PubMed

34. Venkatesh AK, Geisler BP, Gibson Chambers JJ, et al. Use of observation care in US emergency departments, 2001 to 2008. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24326. PubMed

35. Schuur JD, Venkatesh AK. The growing role of emergency departments in hospital admissions. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):391-393. PubMed

36. Kangovi S, Cafardi SG, Smith RA, Kulkarni R, Grande D. Patient financial responsibility for observation care. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(11):718-723. PubMed

37. Doyle BJ, Ettner SL, Nuckols TK. Supplemental insurance reduces out-of-pocket costs in Medicare observation services. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(7):502-504. doi:10.1002/jhm.2588. PubMed

38. Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520-528. PubMed

39. Bradley EH, Curry L, Horwitz LI, et al. Hospital strategies associated with 30-day readmission rates for patients with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(4):444-450. PubMed

40. US Census Bureau. American Fact Finder: community facts. http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml. Accessed November 1, 2016.

41. Van Vleet A, Paradise J. Tapping nurse practitioners to meet rising demand for primary care. Kaiser Family Foundation Issue Brief. January 20, 2015. http://kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/tapping-nurse-practitioners-to-meet-rising-demand-for-primary-care/. Accessed November 7, 2016.

42. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Hospital guide to reducing Medicaid readmissions. Rockville, MD: AHRQ; August 2014. AHRQ Publication No. 14-0050-EF. http://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/publications/files/medreadmissions.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2017.

43. Boccuti C, Casillas G. Aiming for fewer hospital U-turns: The Medicare Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. Kaiser Family Foundation Issue Brief. March 10, 2017. http://kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/aiming-for-fewer-hospital-u-turns-the-medicare-hospital-readmission-reduction-program/. Accessed November 7, 2016.

44. Conway P, Gronniger T. New data: 49 states plus DC reduce avoidable hospital readmissions. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services blog. September 13, 2016. http://medtecheng.com/new-data-49-states-plus-dc-reduce-avoidable-hospital-readmissions/. Accessed September 26, 2017.

1. Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418-1428. PubMed

2. Lum HD, Studenski SA, Degenholtz HB, Hardy SE. Early hospital readmission is a predictor of one-year mortality in community-dwelling older Medicare beneficiaries. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(11):1467-1474. PubMed

3. Peach State Health Plan. New Peach State Health Plan 30-Day Readmission Payment Policy. https://www.pshpgeorgia.com/newsroom/30-day-readmission-payment-policy.html . Accessed September 26, 2017.

4. Axon RN, Cole L, Moonan A, et al. Evolution and Initial Experience of a Statewide Care Transitions Quality Improvement Collaborative: Preventing Avoidable Readmissions Together. Popul Health Manag. 2016 Feb;19(1):4-10. PubMed

5. Nebraska Hospital Association. Quality and Safety. http://www.nebraskahospitals.org/quality_and_safety/qs_home.html. Accessed July 25, 2017.

6. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Re-Engineered Discharge (RED) Toolkit. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/systems/hospital/red/toolkit/index.html. Accessed July 25, 2017.

7. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Readmissions. http://www.ihi.org/Topics/Readmissions/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed July 25, 2017.

8. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP). https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html. Accessed July 19, 2016.

9. Polinski JM, Moore JM, Kyrychenko P, et al. An insurer’s care transition program emphasizes medication reconciliation, reduces readmissions and costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(7):1222-1229. PubMed

10. BlueCross BlueShield. Highmark’s Quality Blue Program helps hospitals reduce readmissions and infections for members. http://www.bcbs.com/healthcare-news/plans/highmark-quality-blue-program-helps-hospitals-reduce-readmissions-and-infections-for-members.html. Accessed November 7, 2016.

11. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Designing and delivering whole-person transitional care: the hospital guide to reducing Medicaid readmissions. Rockville, MD: AHRQ; September 2016. AHRQ Pub. No. 16-0047-EF. http://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/systems/hospital/medicaidreadmitguide/medicaidreadmissions.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2017.

12. Aetna. Aetna, Genesis HealthCare take aim at preventing hospital readmissions. https://news.aetna.com/news-releases/aetna-genesis-healthcare-take-aim-at-preventing-hospital-readmissions/. Accessed November 7, 2016.

13. Molina Healthcare. Medical Management Program.http://www.molinahealthcare.com/providers/wi/medicaid/manual/PDF/manual_WI_19_Medical_Management.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2017.

14. Kaiser Family Foundation. Total Medicaid MCOs. State health facts, 2016. http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-medicaid-mcos/. Accessed July 19, 2016.

15. Muhlestein D, McClellan M. Accountable care organizations in 2016: private and public-sector growth and dispersion. Health Affairs blog. April 21, 2016. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2016/04/21/accountable-care-organizations-in-2016-private-and-public-sector-growth-and-dispersion/. Accessed November 7, 2016.

16. Leppin AL, Gionfriddo MR, Kessler M, et al. Preventing 30-day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1095-1107. PubMed

17. Zuckerman RB, Sheingold SH, Orav EJ, Ruhter J, Epstein AM. Readmissions, observation, and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(16):1543-1551. PubMed

18. Fingar KR, Washington R. Trends in hospital readmissions for four high-volume conditions, 2009–2013. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; November 2015. Statistical Brief No. 196. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb196-Readmissions-Trends-High-Volume-Conditions.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2017.

19. Ross MA, Hockenberry JM, Mutter R, Barrett M, Wheatley M, Pitts SR. Protocol-driven emergency department observation units offer savings, shorter stays, and reduced admissions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(12):2149-2156. PubMed

20. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). HCUP Databases. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; November 2016. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/databases.jsp. Accessed March 15, 2017.

21. QualityNet. Archived resources: readmission measures and measure methodology. https://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?cid=1228774371008&pagename=QnetPublic%2FPage%2FQnetTier4&c=Page. Accessed November 7, 2016.

22. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2014 measures updates and specifications report: hospital-level 30-day risk-standardized readmission measures: acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke. March 2014. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/Measure-Methodology.html. Accessed September 26, 2017.

23. Iacus SM, King G, Porro G. Causal inference without balance checking: coarsened exact matching. Political Analysis. 2012;20(1):1-24.

24. Moore BJ, White S, Washington R, Coenen N, Elixhauser A. Identifying increased risk of readmission and in-hospital mortality using hospital administrative data: The AHRQ Elixhauser Comorbidity Index. Med Care. 2017;55(7):698-705. PubMed

25. Gerhardt G, Yemane A, Apostle K, Oelschlaeger A, Rollins E, Brennan N. Evaluating whether changes in utilization of hospital outpatient services contributed to lower Medicare readmission rate. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2014;4(1):mmrr2014.004.01.b03. PubMed

26. Kripalani S, Theobald CN, Anctil B, Vasilevskis EE. Reducing hospital readmission rates: current strategies and future directions. Annu Rev Med. 2014;65:471-485. PubMed

27. Desai NR, Ross JS, Kwon JY, et al. Association between hospital penalty status under the hospital readmission reduction program and readmission rates for target and nontarget conditions. JAMA. 2016;316(24):2647-2656. PubMed

28. Epstein AM, Jha AK, Orav EJ. The relationship between hospital admission rates and rehospitalizations. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(24):2287-2295. PubMed

29. Venkatesh AK, Wang C, Ross JS, et al. Hospital use of observation stays: cross sectional study of the impact on readmission rates. Med Care. 2016;54(12)1070-1077. PubMed

30. Nuckols TK, Fingar KR, Barrett M, Steiner CA, Stocks C, Owens PL. The shifting landscape in utilization of inpatient, observation, and emergency department Services Across Payers. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(6):443-446. PubMed

31. Dharmarajan K, Qin L, Lin Z, et al. Declining admission rates and thirty-day readmission rates positively associated even though patients grew sicker over time. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(7):1294-1302. PubMed

32. Grube M, Kaufman K, York R. Decline in utilization rates signals a change in the inpatient business model. Health Affairs blog. March 8, 2013. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2013/03/08/decline-in-utilization-rates-signals-a-change-in-the-inpatient-business-model/. Accessed November 7, 2016.

33. Feng Z, Wright B, Mor V. Sharp rise in Medicare enrollees being held in hospitals for observation raises concerns about causes and consequences. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(6):1251-1259. PubMed

34. Venkatesh AK, Geisler BP, Gibson Chambers JJ, et al. Use of observation care in US emergency departments, 2001 to 2008. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24326. PubMed

35. Schuur JD, Venkatesh AK. The growing role of emergency departments in hospital admissions. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):391-393. PubMed

36. Kangovi S, Cafardi SG, Smith RA, Kulkarni R, Grande D. Patient financial responsibility for observation care. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(11):718-723. PubMed