User login

Transverse Melanonychia and Palmar Hyperpigmentation Secondary to Hydroxyurea Therapy

To the Editor:

An 85-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, stroke, hypothyroidism, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic myeloproliferative disorder presented to our clinic for evaluation of brown lesions on the hands and discoloration of the fingernails and toenails of 4 months’ duration. Six months prior to visiting our clinic she was admitted to the hospital for a pulmonary embolism. On admission she was noted to have a platelet count of more than 2 million/μL (reference range, 150,000–350,000/μL). She received urgent plasmapheresis and started hydroxyurea 500 mg twice daily, which she continued as an outpatient.

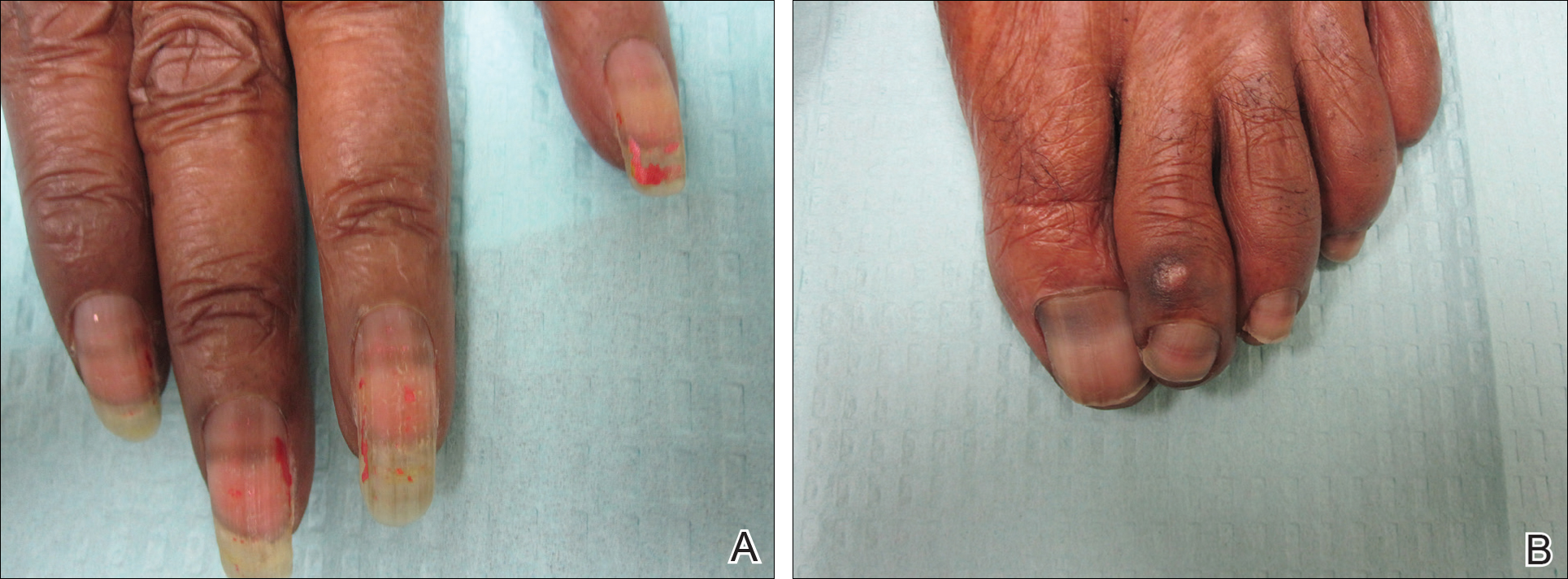

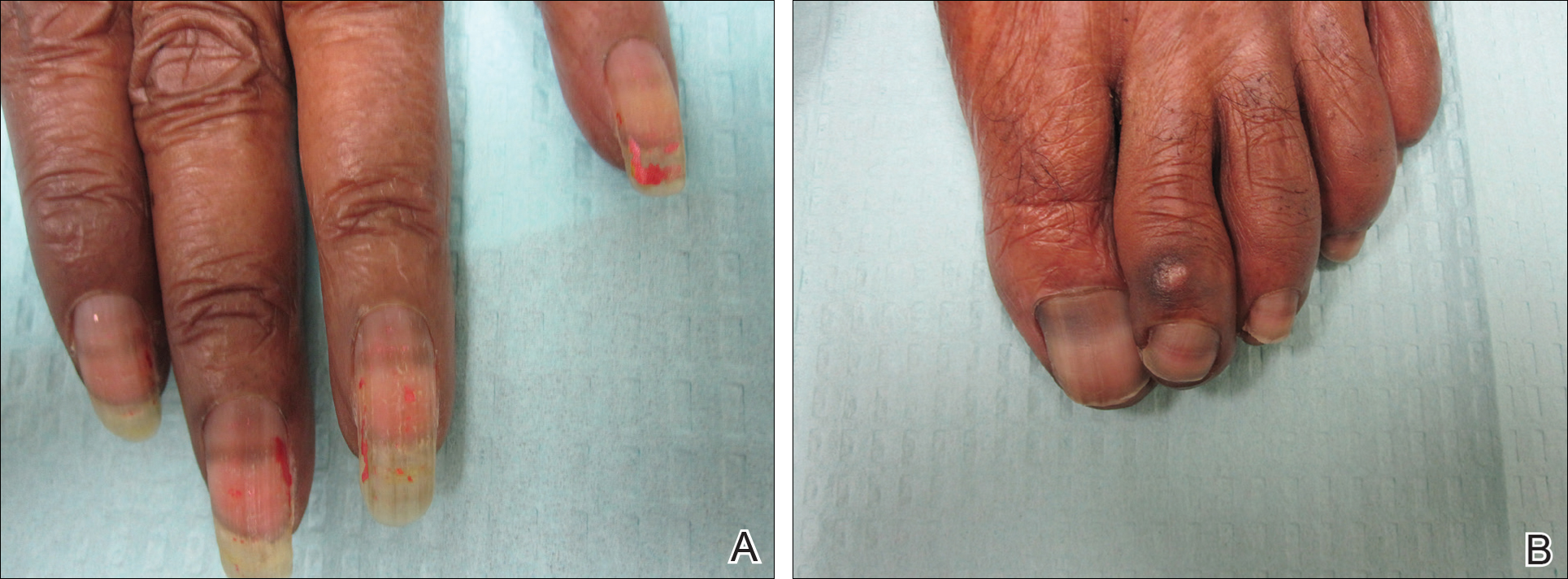

On physical examination at our clinic she had diffusely scattered red and brown macules on the bilateral palms and transverse hyperpigmented bands of various intensities on all fingernails and toenails (Figure). Her platelet count was 372,000/μL, white blood cell count was 5200/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL), hemoglobin was 12.6 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), hematocrit was 39.0% (reference range, 41%–50%), and mean corpuscular volume was 87.5 fL per red cell (reference range, 80–96 fL per red cell).

The patient was diagnosed with hydroxyurea-induced nail hyperpigmentation and was counseled on the benign nature of the condition. Three months later her platelet count decreased to below 100,000/μL, and hydroxyurea was discontinued. She noticed considerable improvement in the lesions on the hands and nails with the cessation of hydroxyurea.

Hydroxyurea is a cytostatic agent that has been used for more than 40 years in the treatment of myeloproliferative disorders including chronic myelogenous leukemia, polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and sickle cell anemia.1 It inhibits ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase and promotes cell death in the S phase of the cell cycle.1-3

Several adverse cutaneous reactions have been associated with hydroxyurea including increased pigmentation, hyperkeratosis, skin atrophy, xerosis, lichenoid eruptions, palmoplantar keratoderma, cutaneous vasculitis, alopecia, chronic leg ulcers, cutaneous carcinomas, and melanonychia.3,4

Hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia most often occurs after several months of therapy but has been reported to occur as early as 4 months and as late as 5 years after initiating the drug.1,4-6 The prevalence of melanonychia in the general population has been estimated at 1% and is thought to increase to approximately 4% in patients treated with hydroxyurea.1,2,6,7 The prevalence of affected individuals increases with age; it is more common in females as well as black and Hispanic patients.2

Multiple patterns of hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia have been described, including longitudinal bands, transverse bands, and diffuse hyperpigmentation.1-3,6 By far the most common pattern described in the literature is longitudinal banding1-3,8; transverse bands are more rare. Although there are sporadic case reports linking the transverse bands with hydroxyurea, these bands occur more frequently with systemic chemotherapy such as doxorubicin and cyclosphosphamide.1,6

The exact pathogenesis of hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia remains unclear, though it is thought to result from focal melanogenesis in the nail bed or matrix followed by deposition of melanin granules on the nail plate.5,8 When these melanocytes are activated, melanosomes filled with melanin are transferred to differentiating matrix cells, which migrate distally as they become nail plate oncocytes, resulting in a visible band of pigmentation in the nail plate.2 There also may be a genetic and photosensitivity component.1,2

Prior case series have described spontaneous remission of nail hyperpigmentation following discontinuation of hydroxyurea therapy.1 In many patients, however, the chronic nature of the myeloproliferative disorder and lack of alternative treatments make a therapeutic change difficult. Although the melanonychia itself is benign, it may precede the appearance of more serious mucocutaneous side effects, such as skin ulceration or development of cutaneous carcinomas, so careful monitoring should be performed.2

Our patient presented with melanonychia that was transverse, polydactylic, monochromic, stable in size and shape, and associated with palmar hyperpigmentation. Of note, the pigmentation remitted over time along with discontinuation of the drug. Although this presentation did not warrant a nail matrix biopsy, it should be noted that patients with single nail melanonychia suspicious for melanoma should have a biopsy, even with concomitant use of hydroxyurea.2 Although transverse melanonychia most commonly is associated with other systemic chemotherapeutics, in the absence of such medications hydroxyurea was the likely culprit in our patient. The palmar hyperpigmentation, which has previously been reported with hydroxyurea use, further solidifies the diagnosis.

- Aste N, Futmo G, Contu F, et al. Nail pigmentation caused by hydroxyurea: report of 9 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:146-147.

- Murray N, Tapia P, Porcell J, et al. Acquired melanonychia in Chilean patients with essential thrombocythemia treated with hydroxyurea: a report of 7 clinical cases and review of the literature [published online February 7, 2013]. ISRN Dermatol. 2013;2013:325246.

- Utas S. A case of hydroxyurea-induced longitudinal melanonychia. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:469-470.

- Saraceno R, Teoli M, Chimenti S. Hydroxyurea associated with concomitant occurrence of diffuse longitudinal melanonychia and multiple squamous cell carcinomas in an elderly subject. Clin Ther. 2008;30:1324-1329.

- Cohen AD, Hallel-Halevy D, Hatskelzon L, et al. Longitudinal melanonychia associated with hydroxyurea therapy in a patient with essential thrombocytosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol. 1999;13:137-139.

- Hernández-Martín A, Ros-Forteza S, de Unamuno P. Longitudinal, transverse, and diffuse nail hyperpigmentation induced by hydroxyurea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 2):333-334.

- Kwong Y. Hydroxyurea-induced nail pigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:275-276.

- O’Branski E, Ware R, Prose N, et al. Skin and nail changes in children with sickle cell anemia receiving hydroxyurea therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:859-861.

To the Editor:

An 85-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, stroke, hypothyroidism, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic myeloproliferative disorder presented to our clinic for evaluation of brown lesions on the hands and discoloration of the fingernails and toenails of 4 months’ duration. Six months prior to visiting our clinic she was admitted to the hospital for a pulmonary embolism. On admission she was noted to have a platelet count of more than 2 million/μL (reference range, 150,000–350,000/μL). She received urgent plasmapheresis and started hydroxyurea 500 mg twice daily, which she continued as an outpatient.

On physical examination at our clinic she had diffusely scattered red and brown macules on the bilateral palms and transverse hyperpigmented bands of various intensities on all fingernails and toenails (Figure). Her platelet count was 372,000/μL, white blood cell count was 5200/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL), hemoglobin was 12.6 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), hematocrit was 39.0% (reference range, 41%–50%), and mean corpuscular volume was 87.5 fL per red cell (reference range, 80–96 fL per red cell).

The patient was diagnosed with hydroxyurea-induced nail hyperpigmentation and was counseled on the benign nature of the condition. Three months later her platelet count decreased to below 100,000/μL, and hydroxyurea was discontinued. She noticed considerable improvement in the lesions on the hands and nails with the cessation of hydroxyurea.

Hydroxyurea is a cytostatic agent that has been used for more than 40 years in the treatment of myeloproliferative disorders including chronic myelogenous leukemia, polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and sickle cell anemia.1 It inhibits ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase and promotes cell death in the S phase of the cell cycle.1-3

Several adverse cutaneous reactions have been associated with hydroxyurea including increased pigmentation, hyperkeratosis, skin atrophy, xerosis, lichenoid eruptions, palmoplantar keratoderma, cutaneous vasculitis, alopecia, chronic leg ulcers, cutaneous carcinomas, and melanonychia.3,4

Hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia most often occurs after several months of therapy but has been reported to occur as early as 4 months and as late as 5 years after initiating the drug.1,4-6 The prevalence of melanonychia in the general population has been estimated at 1% and is thought to increase to approximately 4% in patients treated with hydroxyurea.1,2,6,7 The prevalence of affected individuals increases with age; it is more common in females as well as black and Hispanic patients.2

Multiple patterns of hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia have been described, including longitudinal bands, transverse bands, and diffuse hyperpigmentation.1-3,6 By far the most common pattern described in the literature is longitudinal banding1-3,8; transverse bands are more rare. Although there are sporadic case reports linking the transverse bands with hydroxyurea, these bands occur more frequently with systemic chemotherapy such as doxorubicin and cyclosphosphamide.1,6

The exact pathogenesis of hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia remains unclear, though it is thought to result from focal melanogenesis in the nail bed or matrix followed by deposition of melanin granules on the nail plate.5,8 When these melanocytes are activated, melanosomes filled with melanin are transferred to differentiating matrix cells, which migrate distally as they become nail plate oncocytes, resulting in a visible band of pigmentation in the nail plate.2 There also may be a genetic and photosensitivity component.1,2

Prior case series have described spontaneous remission of nail hyperpigmentation following discontinuation of hydroxyurea therapy.1 In many patients, however, the chronic nature of the myeloproliferative disorder and lack of alternative treatments make a therapeutic change difficult. Although the melanonychia itself is benign, it may precede the appearance of more serious mucocutaneous side effects, such as skin ulceration or development of cutaneous carcinomas, so careful monitoring should be performed.2

Our patient presented with melanonychia that was transverse, polydactylic, monochromic, stable in size and shape, and associated with palmar hyperpigmentation. Of note, the pigmentation remitted over time along with discontinuation of the drug. Although this presentation did not warrant a nail matrix biopsy, it should be noted that patients with single nail melanonychia suspicious for melanoma should have a biopsy, even with concomitant use of hydroxyurea.2 Although transverse melanonychia most commonly is associated with other systemic chemotherapeutics, in the absence of such medications hydroxyurea was the likely culprit in our patient. The palmar hyperpigmentation, which has previously been reported with hydroxyurea use, further solidifies the diagnosis.

To the Editor:

An 85-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, stroke, hypothyroidism, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic myeloproliferative disorder presented to our clinic for evaluation of brown lesions on the hands and discoloration of the fingernails and toenails of 4 months’ duration. Six months prior to visiting our clinic she was admitted to the hospital for a pulmonary embolism. On admission she was noted to have a platelet count of more than 2 million/μL (reference range, 150,000–350,000/μL). She received urgent plasmapheresis and started hydroxyurea 500 mg twice daily, which she continued as an outpatient.

On physical examination at our clinic she had diffusely scattered red and brown macules on the bilateral palms and transverse hyperpigmented bands of various intensities on all fingernails and toenails (Figure). Her platelet count was 372,000/μL, white blood cell count was 5200/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL), hemoglobin was 12.6 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), hematocrit was 39.0% (reference range, 41%–50%), and mean corpuscular volume was 87.5 fL per red cell (reference range, 80–96 fL per red cell).

The patient was diagnosed with hydroxyurea-induced nail hyperpigmentation and was counseled on the benign nature of the condition. Three months later her platelet count decreased to below 100,000/μL, and hydroxyurea was discontinued. She noticed considerable improvement in the lesions on the hands and nails with the cessation of hydroxyurea.

Hydroxyurea is a cytostatic agent that has been used for more than 40 years in the treatment of myeloproliferative disorders including chronic myelogenous leukemia, polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and sickle cell anemia.1 It inhibits ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase and promotes cell death in the S phase of the cell cycle.1-3

Several adverse cutaneous reactions have been associated with hydroxyurea including increased pigmentation, hyperkeratosis, skin atrophy, xerosis, lichenoid eruptions, palmoplantar keratoderma, cutaneous vasculitis, alopecia, chronic leg ulcers, cutaneous carcinomas, and melanonychia.3,4

Hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia most often occurs after several months of therapy but has been reported to occur as early as 4 months and as late as 5 years after initiating the drug.1,4-6 The prevalence of melanonychia in the general population has been estimated at 1% and is thought to increase to approximately 4% in patients treated with hydroxyurea.1,2,6,7 The prevalence of affected individuals increases with age; it is more common in females as well as black and Hispanic patients.2

Multiple patterns of hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia have been described, including longitudinal bands, transverse bands, and diffuse hyperpigmentation.1-3,6 By far the most common pattern described in the literature is longitudinal banding1-3,8; transverse bands are more rare. Although there are sporadic case reports linking the transverse bands with hydroxyurea, these bands occur more frequently with systemic chemotherapy such as doxorubicin and cyclosphosphamide.1,6

The exact pathogenesis of hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia remains unclear, though it is thought to result from focal melanogenesis in the nail bed or matrix followed by deposition of melanin granules on the nail plate.5,8 When these melanocytes are activated, melanosomes filled with melanin are transferred to differentiating matrix cells, which migrate distally as they become nail plate oncocytes, resulting in a visible band of pigmentation in the nail plate.2 There also may be a genetic and photosensitivity component.1,2

Prior case series have described spontaneous remission of nail hyperpigmentation following discontinuation of hydroxyurea therapy.1 In many patients, however, the chronic nature of the myeloproliferative disorder and lack of alternative treatments make a therapeutic change difficult. Although the melanonychia itself is benign, it may precede the appearance of more serious mucocutaneous side effects, such as skin ulceration or development of cutaneous carcinomas, so careful monitoring should be performed.2

Our patient presented with melanonychia that was transverse, polydactylic, monochromic, stable in size and shape, and associated with palmar hyperpigmentation. Of note, the pigmentation remitted over time along with discontinuation of the drug. Although this presentation did not warrant a nail matrix biopsy, it should be noted that patients with single nail melanonychia suspicious for melanoma should have a biopsy, even with concomitant use of hydroxyurea.2 Although transverse melanonychia most commonly is associated with other systemic chemotherapeutics, in the absence of such medications hydroxyurea was the likely culprit in our patient. The palmar hyperpigmentation, which has previously been reported with hydroxyurea use, further solidifies the diagnosis.

- Aste N, Futmo G, Contu F, et al. Nail pigmentation caused by hydroxyurea: report of 9 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:146-147.

- Murray N, Tapia P, Porcell J, et al. Acquired melanonychia in Chilean patients with essential thrombocythemia treated with hydroxyurea: a report of 7 clinical cases and review of the literature [published online February 7, 2013]. ISRN Dermatol. 2013;2013:325246.

- Utas S. A case of hydroxyurea-induced longitudinal melanonychia. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:469-470.

- Saraceno R, Teoli M, Chimenti S. Hydroxyurea associated with concomitant occurrence of diffuse longitudinal melanonychia and multiple squamous cell carcinomas in an elderly subject. Clin Ther. 2008;30:1324-1329.

- Cohen AD, Hallel-Halevy D, Hatskelzon L, et al. Longitudinal melanonychia associated with hydroxyurea therapy in a patient with essential thrombocytosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol. 1999;13:137-139.

- Hernández-Martín A, Ros-Forteza S, de Unamuno P. Longitudinal, transverse, and diffuse nail hyperpigmentation induced by hydroxyurea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 2):333-334.

- Kwong Y. Hydroxyurea-induced nail pigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:275-276.

- O’Branski E, Ware R, Prose N, et al. Skin and nail changes in children with sickle cell anemia receiving hydroxyurea therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:859-861.

- Aste N, Futmo G, Contu F, et al. Nail pigmentation caused by hydroxyurea: report of 9 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:146-147.

- Murray N, Tapia P, Porcell J, et al. Acquired melanonychia in Chilean patients with essential thrombocythemia treated with hydroxyurea: a report of 7 clinical cases and review of the literature [published online February 7, 2013]. ISRN Dermatol. 2013;2013:325246.

- Utas S. A case of hydroxyurea-induced longitudinal melanonychia. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:469-470.

- Saraceno R, Teoli M, Chimenti S. Hydroxyurea associated with concomitant occurrence of diffuse longitudinal melanonychia and multiple squamous cell carcinomas in an elderly subject. Clin Ther. 2008;30:1324-1329.

- Cohen AD, Hallel-Halevy D, Hatskelzon L, et al. Longitudinal melanonychia associated with hydroxyurea therapy in a patient with essential thrombocytosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol. 1999;13:137-139.

- Hernández-Martín A, Ros-Forteza S, de Unamuno P. Longitudinal, transverse, and diffuse nail hyperpigmentation induced by hydroxyurea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 2):333-334.

- Kwong Y. Hydroxyurea-induced nail pigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:275-276.

- O’Branski E, Ware R, Prose N, et al. Skin and nail changes in children with sickle cell anemia receiving hydroxyurea therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:859-861.

Practice Points

- Transverse melanonychia may result as a side effect of hydroxyurea.

- Discontinuation of hydroxyurea typically results in a resolution of symptoms. If the medication cannot be stopped, however, pigmentary changes may precede the development of severe mucocutaneous side effects and close monitoring is warranted.

- Patients with single nail melanonychia suspicious for melanoma should have a biopsy, even with concomitant use of hydroxyurea.

Friable Warty Plaque on the Heel

The Diagnosis: Verrucous Hemangioma

Verrucous hemangioma (VH) is a rare vascular anomaly that has not been definitively delineated as a malformation or a tumor, as it has features of both. Verrucous hemangioma presents at birth as a compressible soft mass with a red violaceous hue favoring the legs.1,2 Over time VH will develop a warty, friable, and keratotic surface that can begin to evolve as early as 6 months or as late as 34 years of age.3 Verrucous hemangioma does not involute and tends to grow proportionally with the patient. Thus, VH classically has been considered a vascular malformation.

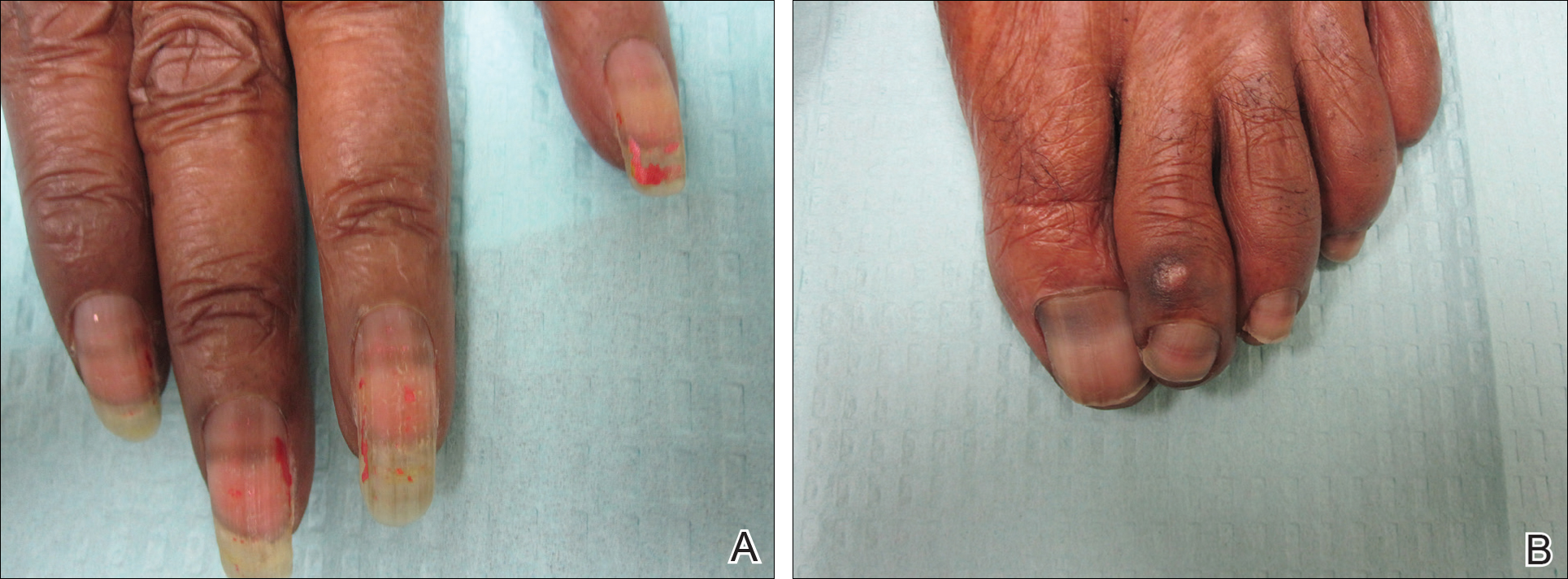

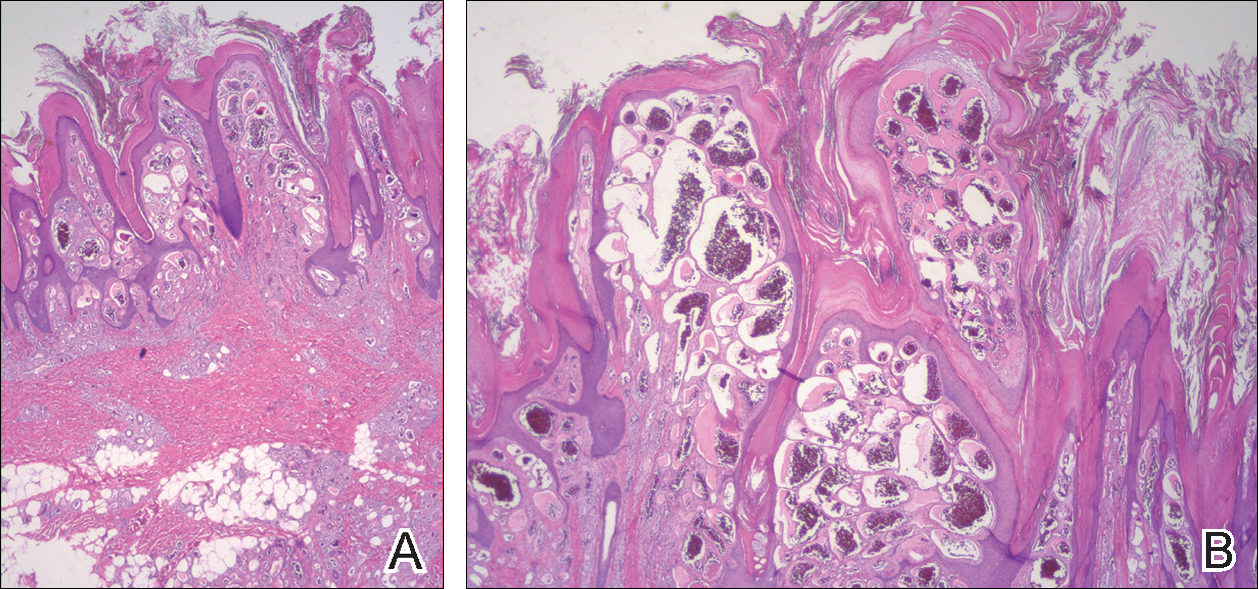

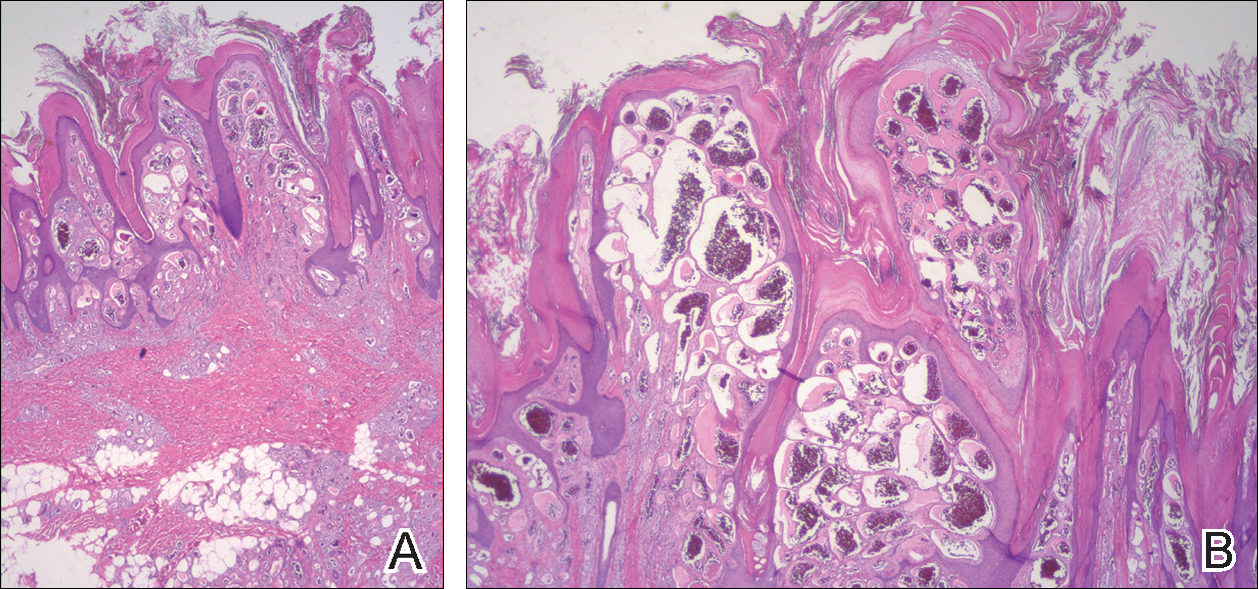

On histopathology VH shows collections of uniform, thin-walled vessels with a multilamellated basement membrane throughout the dermis, similar to an infantile hemangioma (IH). These lesions extend deep into the subcutaneous tissue and often involve the underlying fascia. The papillary dermis has large ectatic vessels, while the epidermis displays verrucous hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and irregular acanthosis without viral change (Figure).4,5 The superficial component can resemble an angiokeratoma; however, VH is differentiated by a deeper component that is often larger in size and has a more protracted clinical course.

Similar to IH, immunohistochemical studies have shown that VH expresses Wilms tumor 1 and glucose transporter 1 but is negative for D2-40.4 These findings suggest that VH is a vascular tumor rather than a vascular malformation, as was previously reported.6 Additional research has shown that the immunohistochemical staining profile of VH is nearly identical to IH, which has led to postulation that VH may be of placental mesodermal origin, as has been hypothesized for IH.5

Due to its deep infiltration and tendency for recurrence, VH is most effectively treated with wide local excision.3,6-8 Preoperative planning with magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated. Although laser monotherapy and other local destructive therapies have been largely unsuccessful, postsurgical laser therapy with CO2 lasers as well as dual pulsed dye laser and Nd:YAG laser have shown promise in preventing recurrence.3

- Tennant LB, Mulliken JB, Perez-Atayde AR, et al. Verrucous hemangioma revisited. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:208-215.

- Koc M, Kavala M, Kocatür E, et al. An unusual vascular tumor: verrucous hemangioma. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:7.

- Yang CH, Ohara K. Successful surgical treatment of verrucous hemangioma: a combined approach. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:913-919; discussion 920.

- Trindade F, Torrelo A, Requena L, et al. An immunohistochemical study of verrucous hemangiomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:472-476.

- Laing EL, Brasch HD, Steel R, et al. Verrucous hemangioma expresses primitive markers. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:391-396.

- Mankani MH, Dufresne CR. Verrucous malformations: their presentation and management. Ann Plast Surg. 2000;45:31-36.

- Clairwood MQ, Bruckner AL, Dadras SS. Verrucous hemangioma: a report of two cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:740-746.

- Segura Palacios JM, Boixeda P, Rocha J, et al. Laser treatment for verrucous hemangioma. Laser Med Sci. 2012;27:681-684.

The Diagnosis: Verrucous Hemangioma

Verrucous hemangioma (VH) is a rare vascular anomaly that has not been definitively delineated as a malformation or a tumor, as it has features of both. Verrucous hemangioma presents at birth as a compressible soft mass with a red violaceous hue favoring the legs.1,2 Over time VH will develop a warty, friable, and keratotic surface that can begin to evolve as early as 6 months or as late as 34 years of age.3 Verrucous hemangioma does not involute and tends to grow proportionally with the patient. Thus, VH classically has been considered a vascular malformation.

On histopathology VH shows collections of uniform, thin-walled vessels with a multilamellated basement membrane throughout the dermis, similar to an infantile hemangioma (IH). These lesions extend deep into the subcutaneous tissue and often involve the underlying fascia. The papillary dermis has large ectatic vessels, while the epidermis displays verrucous hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and irregular acanthosis without viral change (Figure).4,5 The superficial component can resemble an angiokeratoma; however, VH is differentiated by a deeper component that is often larger in size and has a more protracted clinical course.

Similar to IH, immunohistochemical studies have shown that VH expresses Wilms tumor 1 and glucose transporter 1 but is negative for D2-40.4 These findings suggest that VH is a vascular tumor rather than a vascular malformation, as was previously reported.6 Additional research has shown that the immunohistochemical staining profile of VH is nearly identical to IH, which has led to postulation that VH may be of placental mesodermal origin, as has been hypothesized for IH.5

Due to its deep infiltration and tendency for recurrence, VH is most effectively treated with wide local excision.3,6-8 Preoperative planning with magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated. Although laser monotherapy and other local destructive therapies have been largely unsuccessful, postsurgical laser therapy with CO2 lasers as well as dual pulsed dye laser and Nd:YAG laser have shown promise in preventing recurrence.3

The Diagnosis: Verrucous Hemangioma

Verrucous hemangioma (VH) is a rare vascular anomaly that has not been definitively delineated as a malformation or a tumor, as it has features of both. Verrucous hemangioma presents at birth as a compressible soft mass with a red violaceous hue favoring the legs.1,2 Over time VH will develop a warty, friable, and keratotic surface that can begin to evolve as early as 6 months or as late as 34 years of age.3 Verrucous hemangioma does not involute and tends to grow proportionally with the patient. Thus, VH classically has been considered a vascular malformation.

On histopathology VH shows collections of uniform, thin-walled vessels with a multilamellated basement membrane throughout the dermis, similar to an infantile hemangioma (IH). These lesions extend deep into the subcutaneous tissue and often involve the underlying fascia. The papillary dermis has large ectatic vessels, while the epidermis displays verrucous hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and irregular acanthosis without viral change (Figure).4,5 The superficial component can resemble an angiokeratoma; however, VH is differentiated by a deeper component that is often larger in size and has a more protracted clinical course.

Similar to IH, immunohistochemical studies have shown that VH expresses Wilms tumor 1 and glucose transporter 1 but is negative for D2-40.4 These findings suggest that VH is a vascular tumor rather than a vascular malformation, as was previously reported.6 Additional research has shown that the immunohistochemical staining profile of VH is nearly identical to IH, which has led to postulation that VH may be of placental mesodermal origin, as has been hypothesized for IH.5

Due to its deep infiltration and tendency for recurrence, VH is most effectively treated with wide local excision.3,6-8 Preoperative planning with magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated. Although laser monotherapy and other local destructive therapies have been largely unsuccessful, postsurgical laser therapy with CO2 lasers as well as dual pulsed dye laser and Nd:YAG laser have shown promise in preventing recurrence.3

- Tennant LB, Mulliken JB, Perez-Atayde AR, et al. Verrucous hemangioma revisited. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:208-215.

- Koc M, Kavala M, Kocatür E, et al. An unusual vascular tumor: verrucous hemangioma. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:7.

- Yang CH, Ohara K. Successful surgical treatment of verrucous hemangioma: a combined approach. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:913-919; discussion 920.

- Trindade F, Torrelo A, Requena L, et al. An immunohistochemical study of verrucous hemangiomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:472-476.

- Laing EL, Brasch HD, Steel R, et al. Verrucous hemangioma expresses primitive markers. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:391-396.

- Mankani MH, Dufresne CR. Verrucous malformations: their presentation and management. Ann Plast Surg. 2000;45:31-36.

- Clairwood MQ, Bruckner AL, Dadras SS. Verrucous hemangioma: a report of two cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:740-746.

- Segura Palacios JM, Boixeda P, Rocha J, et al. Laser treatment for verrucous hemangioma. Laser Med Sci. 2012;27:681-684.

- Tennant LB, Mulliken JB, Perez-Atayde AR, et al. Verrucous hemangioma revisited. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:208-215.

- Koc M, Kavala M, Kocatür E, et al. An unusual vascular tumor: verrucous hemangioma. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:7.

- Yang CH, Ohara K. Successful surgical treatment of verrucous hemangioma: a combined approach. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:913-919; discussion 920.

- Trindade F, Torrelo A, Requena L, et al. An immunohistochemical study of verrucous hemangiomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:472-476.

- Laing EL, Brasch HD, Steel R, et al. Verrucous hemangioma expresses primitive markers. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:391-396.

- Mankani MH, Dufresne CR. Verrucous malformations: their presentation and management. Ann Plast Surg. 2000;45:31-36.

- Clairwood MQ, Bruckner AL, Dadras SS. Verrucous hemangioma: a report of two cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:740-746.

- Segura Palacios JM, Boixeda P, Rocha J, et al. Laser treatment for verrucous hemangioma. Laser Med Sci. 2012;27:681-684.

A 31-year-old man presented with a large friable and warty plaque on the left heel. He recalled that the lesion had been present since birth as a flat red birthmark that grew proportionally with him. Throughout his adolescence its surface became increasingly rough and bumpy. The patient described receiving laser treatment twice in his early 20s without notable improvement. He wanted the lesion removed because it was easily traumatized, resulting in bleeding, pain, and infection. The patient reported being otherwise healthy.