User login

Perspectives of Clinicians, Staff, and Veterans in Transitioning Veterans from non-VA Hospitals to Primary Care in a Single VA Healthcare System

As the VA moves toward increased utilization of non-VA care, it is crucial to understand and address the challenges of transitional care faced by dual-use veterans to provide high-quality care that improves healthcare outcomes.7,11,12 The VA implemented a shift in policy from the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 (Public Law 113-146; “Choice Act”) to the VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act beginning June 6, 2019.13,14 Under the MISSION Act, veterans have more ways to access healthcare within the VA’s network and through approved non-VA medical providers in the community known as “community care providers.”15 This shift expanded the existing VA Choice Act of 2014, where the program allowed those veterans who are unable to schedule an appointment within 30 days of their preferred date or the clinically appropriate date, or on the basis of their place of residence, to elect to receive care from eligible non-VA healthcare entities or providers.14,15 These efforts to better serve veterans by increasing non-VA care might present added care coordination challenges for patients and their providers when they seek care in the VA.

High-quality transitional care prevents poor outcomes such as hospital readmissions.16-18 When communication and coordination across healthcare delivery systems are lacking, patients and their families often find themselves at risk for adverse events.19,20 Past research shows that patients have fewer adverse events when they receive comprehensive postdischarge care, including instructions on medications and self-care, symptom recognition and management, and reminders to attend follow-up appointments.17,21,22 Although researchers have identified the components of effective transitional care,23 barriers persist. The communication and collaboration needed to provide coordinated care across healthcare delivery systems are difficult due to the lack of standardized approaches between systems.24 Consequently, follow-up care may be delayed or missed altogether. To our knowledge, there is no published research identifying transitional care challenges for clinicians, staff, and veterans in transitioning from non-VA hospitals to a VA primary care setting.

The objective of this quality assessment was to understand VA and non-VA hospital clinicians’ and staff as well as veterans’ perspectives of the barriers and facilitators to providing high-quality transitional care.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a qualitative assessment within the VA Eastern Colorado Health Care System, an urban tertiary medical center, as well as urban and rural non-VA hospitals used by veterans. Semi-structured interview guides informed by the practical robust implementation and sustainability (PRISM) model, the Lean approach, and the Ideal Transitions of Care Bridge were used.25-27 We explored the PRISM domains such as recipient’s characteristics, the interaction with the external environment, and the implementation and sustainability infrastructure to inform the design and implementation of the intervention.25 The Lean approach included methods to optimize processes by maximizing efficiency and minimizing waste.26 The Ideal Transitions of Care Bridge was used to identify the domains in transitions of care such as discharge planning, communication of information, and care coordination.27

Setting and Participants

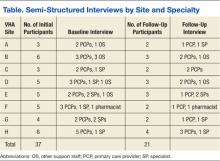

We identified the top 10 non-VA hospitals serving the most urban and rural veterans in 2015 using VA administrative data. Purposive sampling was used to ensure that urban and rural non-VA hospitals and different roles within these hospitals were represented. VA clinicians and staff were selected from the Denver VA Medical Center, a tertiary hospital within the Eastern Colorado Health Care System and one VA Community-Based Outpatient Clinic (CBOC) that primarily serves rural veterans. The Denver VA Medical Center has three clinics staffed by Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACTs), a model built on the concept of Patient-Centered Medical Home.28 Hospital leadership were initially approached for permission to recruit their staff and to be involved as key informants, and all agreed. To ensure representativeness, diversity of roles was recruited, including PACT primary care physicians, nurses, and other staff members such as medical assistants and administrators. Veterans were approached for sampling if they were discharged from a non-VA hospital during June–September 2015 and used the VA for primary care. This was to ensure that they remembered the process they went through postdischarge at the time of the interview.

Data Collection and Analysis

The evaluation team members (RA, EL, and MM) conducted the interviews from November 2015 to July 2016. Clinicians, staff, and veterans were asked semi-structured questions about their experiences and their role in transitioning VA patients across systems (see Appendix for interview guides). Veterans were asked to describe their experience and satisfaction with the current postdischarge transition process. We stopped the interviews when we reached data saturation.29

Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and validated (transcribed interviews were double-checked against recording) to ensure data quality and accuracy. Coding was guided by a conventional content analysis technique30, 31 using a deductive and inductive coding approach.31 The deductive coding approach was drawn from the Ideal Transitions of Care Bridge and PRISM domains. 32,33 Two evaluation team members (RA and EL) defined the initial code book by independently coding the first three interviews, worked to clarify the meanings of emergent codes, and came to a consensus when disagreements occurred. Next, a priori codes were added by team members to include the PRISM domains. These PRISM domains included the implementation and sustainability infrastructure, the external environment, the characteristics of intervention recipients, and the organizational and patient perspectives of an intervention.

Additional emergent codes were added to the code book and agreed upon by team members (RA, EL, and MM). Consistent with previously used methods, consensus building was achieved by identifying and resolving differences by discussing with team members (RA, EL, MM, CB, and RB).29 Codes were examined and organized into themes by team members.29,34-36 This process was continued until no new themes were identified. Results were reviewed by all evaluation team members to assess thoroughness and comprehensiveness.34,35 In addition, team members triangulated the findings with VA and non-VA participants to ensure validity and reduce researcher bias.29,37

RESULTS

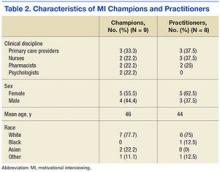

We conducted a total of 70 interviews with 23 VA and 29 non-VA hospital clinicians and staff and 18 veterans (Table 1). Overall, we found that there was no standardized process for transitioning veterans across healthcare delivery systems. Participants reported that transitions were often inefficient when non-VA hospitals could not (1) identify patients as veterans and notify VA primary care of discharge; (2) transfer non-VA hospital medical records to VA primary care; (3) obtain follow-up care appointments with VA primary care; and (4) write VA formulary medications for veterans to fill at VA pharmacies. In addition, participants discussed about facilitators and suggestions to overcome these inefficiencies and improve transitional care (Table2). We mapped the identified barriers as well as the suggestions for improvement to the PRISM and the Ideal Transitions of Care Bridge domains (Table 3).

Unable to Identify Patients as Veterans and Notify VA Primary Care of Discharge

VA and non-VA participants reported difficulty in communicating about veterans’ hospitalizations and discharge follow-up needs across systems. Non-VA clinicians referenced difficulty in identifying patients as veterans to communicate with VA, except in instances where the VA is a payor, while VA providers described feeling largely uninformed of the veterans non-VA hospitalization. For non-VA clinicians, the lack of a systematic method for veteran identification often left them to inadvertently identify veteran status by asking about their primary care clinicians and insurance and even through an offhanded comment made by the veteran. If a veteran was identified, non-VA clinicians described being uncertain about the best way to notify VA primary care of the patient’s impending discharge. Veterans described instances of the non-VA hospital knowing their veteran status upon admission, but accounts varied on whether the non-VA hospital notified the VA primary care of their hospitalization (Table 2, Theme 1).

Unable to Transfer Non-VA Hospital Medical Records to VA Primary Care

VA clinicians discussed about the challenges associated with obtaining the veteran’s medical record from the non-VA hospitals, and when it was received, it was often incomplete information and significantly delayed. They described relying on the veteran’s description of the care received, which was not complete or accurate information needed to make clinical judgment or coordinate follow-up care. Non-VA clinicians mentioned about trying several methods for transferring the medical record to VA primary care, including discharge summary via electronic system and sometimes solely relying on patients to deliver discharge paperwork to their primary care clinicians. In instances where non-VA hospitals sent discharge paperwork to VA, there was no way for non-VA hospitals to verify whether the faxed electronic medical record was received by the VA hospital. Most of the veterans discussed receiving written postdischarge instructions to take to their VA primary care clinicians; however, they were unsure whether the VA primary care received their medical record or any other information from the non-VA hospital (Table 2, Theme 2).

Unable to Obtain Follow-Up Care Appointments with VA Primary Care

All participants described how difficult it was to obtain a follow-up appointment for veterans with VA primary care. This often resulted in delayed follow-up care. VA clinicians also shared that a non-VA hospitalization can be the impetus for a veteran to seek care at the VA for the very first time. Once eligibility is determined, the veteran is assigned a VA primary care clinician. This process may take up to six weeks, and in the meantime, the veteran is scheduled in VA urgent care for immediate postdischarge care. This lag in primary care assignment creates delayed and fragmented care (Table 2, Theme 3).

Non-VA clinicians, administrators, and staff also discussed the difficulties in scheduling follow-up care with VA primary care. Although discharge paperwork instructed patients to see their VA clinicians, there was no process in place for non-VA clinicians to confirm whether the follow-up care was received due to lack of bilateral communication. In addition, veterans discussed the inefficiencies in scheduling follow-up appointments with VA clinicians where attempts to follow-up with primary care clinicians took eight weeks or more. Several veterans described walking into the clinic without an appointment asking to be seen postdischarge or utilizing the VA emergency department for follow-up care after discharge from a non-VA hospital. Veterans admitted utilizing the VA emergency department for nonemergent reasons such as filling their prescriptions because they are unable to see a VA PCP in a timely manner (Table 2, Theme 3).

Unable to Write VA Formulary Medications for Veterans to Fill at VA Pharmacies

All participants described the difficulties in obtaining medications at VA pharmacies when prescribed by the non-VA hospital clinicians. VA clinicians often had to reassess, and rewrite prescriptions written by clinicians, causing delays. Moreover, rural VA clinicians described lack of VA pharmacies in their locations, where veterans had to mail order medications, causing further delays in needed medications. Non-VA clinicians echoed these frustrations. They noted that veterans were confused about their VA pharmacy benefits as well as the need for the non-VA clinicians to follow VA formulary guidelines. Veterans expressed that it was especially challenging to physically go to the VA pharmacy to pick up medications after discharge due to lack of transportation, limited VA pharmacy hours, and long wait times. Several veterans discussed paying for their prescriptions out of pocket even though they had VA pharmacy benefits because it was more convenient to use the non-VA pharmacy. In other instances, veterans discussed going to a VA emergency department and waiting for hours to have their non-VA clinician prescription rewritten by a VA clinician (Table 2, Theme 4).

Facilitators of the Current Transition Process

Several participants provided examples of when transitional care communication between systems occurred seamlessly. VA staff and veterans noted that the VA increased the availability of urgent care appointments, which allowed for timelier postacute care follow-up appointments. Non-VA hospital clinicians also noted the availability of additional appointment slots but stated that they did not learn about these additional appointments directly from the VA. Instead, they learned of these through medical residents caring for patients at both VA and non-VA hospitals. One VA CBOC designated two nurses to care for walk-in veterans for their postdischarge follow-up needs. Some VA participants also noted that the VA Call Center Nurses occasionally called veterans upon discharge to schedule a follow-up appointment and facilitated timely care.

Participants from a VA CBOC discussed being part of a Community Transitions Consortium aimed at identifying high-utilizing patients (veteran and nonveteran) and improving communication across systems. The consortium members discussed each facility’s transition-of-care process, described having access to local non-VA hospital medical records and a backline phone number at the non-VA hospitals to coordinate transitional care. This allowed the VA clinicians to learn about non-VA hospital processes and veteran needs.

Suggestions for Improving the Transitional Care Process

VA and non-VA clinicians suggested hiring a VA liaison, preferably with a clinical background to facilitate care coordination across healthcare systems. They recommended that this person work closely with VA primary care, strengthen the relationship with non-VA hospitals, and help veterans learn more about the transition-of-care processes. Topics discussed for veteran education included how to (1) access their primary care tea

Veterans agreed that improvements to the current process should include an efficient system for obtaining medications and the ability to schedule timely follow-up appointments. Furthermore, veterans wanted education about the VA transition-of-care process following a non-VA hospitalization, including payment and VA notification processes (Table 2, Theme 5).

DISCUSSION

Participants described the current transitional care process as inefficient with specific barriers that have negative consequences on patient care and clinician and staff work processes. They described difficulties in obtaining medications prescribed by non-VA clinicians from VA pharmacies, delays in follow-up appointments at the VA, and lack of bilateral communication between systems and medical record transfer. Participants also provided concrete suggestions to improving the current process, including a care coordinator with clinical background. These findings are important in the context of VA increasing veteran access to care in the community.

Despite an increasing emphasis on veteran access to non-VA care as a result of the VA strategic goals and several new programs,7,12,13 there has not been a close examination of the current transition-of-care process from non-VA hospitals to VA primary care. Several studies have shown that the period following a hospitalization is especially vulnerable and associated with adverse events such as readmission, high cost, and death.12,31,32 Our findings agree with previous research that identified medical record transfer across systems as one of the most challenging issues contributing to deficits in communication between care teams.33 In addition, our study brought into focus the significant challenges faced by veterans in obtaining medications post non-VA hospital discharge. Addressing these key barriers in transitional care will improve the quality, safety, and value of healthcare in the current transition process.38,39

Based on our findings, our participants’ concern in transitional care can be addressed in various ways. First, as veterans are increasingly receiving care in the community, identifying their veteran status early on in the non-VA hospital setting could help in improved, real time communication with the VA. This could be done by updating patient intake forms to ask patients whether they are veterans or not. Second, VA policy-level changes should work to provide veterans access to non-VA pharmacy benefits equivalent to the access patients are receiving for hospital, specialty, and outpatient care. Third, patient and provider satisfaction for dual-use veterans should be examined closely. Although participants expressed frustration with the overall transitions of care from non-VA hospitals to VA primary care setting, influence of this on the Quadruple Aim-improving patient outcomes, experience, and reducing clinician and staff burnout should be examined closely.40 Fourth, evidence-based interventions such as nurse-led transitional care programs that have proven helpful in reducing adverse outcomes in both VA and non-VA settings will be useful to implement.41-45 Such programs could be located in the VA, and a care coordinator role could help facilitate transitional care needs for veterans by working with multiple non-VA hospitals.

The limitations of this study are that the perspectives shared by these participants may not represent all VA and non-VA hospitals as well as veterans’ experiences with transition of care. In addition, the study was conducted in one state and the findings may not be applicable to other healthcare systems. However, our study highlighted the consistent challenges of receiving care across VA and other hospital systems. Two strengths of this study are that it was conducted by multidisciplinary research team members with expertise in qualitative research, clinical care, and implementation science and that we obtained convergent information from VA, non-VA, and veteran participants.

Our current transition-of-care process has several shortcomings. There was a clear agreement on barriers, facilitators, and suggestions for improving the current transitions-of-care process among VA and non-VA hospital participants, as well as from veterans who experienced transitions across different delivery systems. Transitioning veterans to VA primary care following a non-VA hospitalization is a crucial first step for improving care for veterans and reducing adverse outcomes such as avoidable hospital readmissions and death.

These results describe the inefficiencies experienced by patients, clinicians, and staff and their suggestions to alleviate these barriers for optimal continuum of care. To avoid frustration and inefficiencies, the increased emphasis of providing non-VA care for veterans should consider the challenges experienced in transitional care and the opportunities for increased coordination of care.

1. Borowsky SJ, Cowper DC. Dual use of VA and non-VA primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(5):274-280. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00335.x.

2. Charlton ME, Mengeling MA, Schlichting JA, et al. Veteran use of health care systems in rural states. Comparing VA and Non-VA health care use among privately insured veterans under age 65. J Rural Health. 2016;32(4):407-417. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12206.

3. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007.

4. Nguyen KA, Haggstrom DA, Ofner S, et al. Medication use among veterans across health care systems. Appl Clin Inform. 2017;26(1):235-249. https://doi.org/10.4338/ACI-2016-10-RA-0184.

5. Nayar P, Apenteng B, Yu F, Woodbridge P, Fetrick A. Rural veterans’ perspectives of dual care. J Commun Health. 2013;38(1):70-77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-012-9583-7.

6. West AN, Charlton ME. Insured veterans’ use of VA and Non-VA health care in a rural state. J Rural Health. 2016;32(4):387-396. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12196.

7. Gellad WF. The veterans choice act and dual health system use. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(2):153-154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3492-2.

8. Axon RN, Gebregziabher M, Everett CJ, Heidenreich P, Hunt KJ. Dual health care system use is associated with higher rates of hospitalization and hospital readmission among veterans with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2016;174:157-163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2015.09.023.

9. Humensky J, Carretta H, de Groot K, et al. Service utilization of veterans dually eligible for VA and medicare fee-for-service: 1999–2004. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2012;2(3). https://doi.org/10.5600/mmrr.002.03.A06.

10. West AN, Charlton ME, Vaughan-Sarrazin M. Dual use of VA and non-VA hospitals by veterans with multiple hospitalizations. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):431. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1069-8.

11. Gaglioti A, Cozad A, Wittrock S, et al. Non-VA primary care providers’ perspectives on comanagement for rural veterans. Mil Med. 2014;179(11):1236-1243. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00342.

12. Department of Veterans Affairs. Expanded access to non-VA care through the veterans choice program. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2018;83(92):21893-21897.

13. Shuster B. Text-H.R.3236-114th Congress. Surface Transportation and Veterans Health Care Choice Improvement Act of 2015.. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/3236/text/pl. Accessed April 16, 2017; 2015-2016.

14. Veterans Affairs Mission Act. MISSIONAct.va.gov Available at. https://missionact.va.gov/. Accessed August 9, 2019.

15. Veterans Choice Program (VCP). Community care. https://www.va.gov/COMMUNITYCARE/programs/veterans/VCP/index.asp. Accessed August 9, 2019.

16. A Decade of Transitional Care Research with Vulnerable Elder… : journal of cardiovascular nursing. LWW. http://journals.lww.com/jcnjournal/Fulltext/2000/04000/A_Decade_of_Transitional_Care_Research_with.4.aspx. Accessed April 16, 2017.

17. Coleman EA, Boult C. Improving the quality of transitional care for persons with complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):556-557. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51186.x.

18. Krichbaum K. GAPN postacute care coordination improves hip fracture outcomes. West J Nurs Res. 2007;29(5):523-544. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945906293817.

19. Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL, Coleman EA. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):314-323. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.228.

20. Coleman EA, Mahoney E, Parry C. Assessing the quality of preparation for posthospital care from the patient’s perspective: the care transitions measure. Med Care. 2005;43(3):246-255. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200503000-00007.

21. Naylor MD, Aiken LH, Kurtzman ET, Olds DM, Hirschman KB. The importance of transitional care in achieving health reform. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(4):746-754. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0041.

22. Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, et al. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(5):675-684. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52202.x.

23. Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of care consensus policy statement: American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, society of hospital medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(6):364-370. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.510.

24. Coleman EA. Falling through the cracks: challenges and opportunities for improving transitional care for persons with continuous complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):549-555. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51185.x.

25. Feldstein AC, Glasgow RE. A practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) for integrating research findings into practice. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(4):228-243. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1553-7250(08)34030-6.

26. Schweikhart SA, Dembe AE. The applicability of lean and six sigma techniques to clinical and translational research. J Investig Med. 2009;57(7):748-755. https://doi.org/10.2310/JIM.0b013e3181b91b3a.

27. Burke RE, Kripalani S, Vasilevskis EE, Schnipper JL. Moving beyond readmission penalties: creating an ideal process to improve transitional care. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(2):102-109. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1990.

28. Patient Aligned Care Team (PACT)-Patient Care. Services. https://www.patientcare.va.gov/primarycare/PACT.asp. Accessed November 20, 2017.

29. Morse JM. Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(9):1212-1222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315588501.

30. Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277-1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

31. Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5(1):80-92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107.

32. Ayele RA, Lawrence E, McCreight M, et al. Study protocol: improving the transition of care from a non-network hospital back to the patient’s medical home. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):123. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2048-z.

33. Burke RE, Kripalani S, Vasilevskis EE, Schnipper JL. Moving beyond readmission penalties: creating an ideal process to improve transitional care. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(2):102-109. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1990.

34. Qualitative research & evaluation methods. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/qualitative-research-evaluation-methods/book232962. Accessed April 16, 2017. SAGE Publications Inc.

35. Curry LA, Nembhard IM, Bradley EH. Qualitative and mixed methods provide unique contributions to outcomes research. Circulation. 2009;119(10):1442-1452. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.742775.

36. Creswell JW, Hanson WE, Clark Plano VL, Morales A. Qualitative research designs: selection and implementation. Couns Psychol. 2007;35(2):236-264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006287390.

37. Carter N, Bryant-Lukosius D, DiCenso A, Blythe J, Neville AJ. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41(5):545-547. https://doi.org/10.1188/14.ONF.545-547.

38. Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome—an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):100-102. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1212324.

39. Improving Care Transitions. Health affairs-health policy briefs. http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=76. Accessed August 13, 2016.

40. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573-576. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1713.

41. Burke RE, Kelley L, Gunzburger E, et al. Improving transitions of care for veterans transferred to tertiary VA medical centers. Am J Med Qual. 2018;33(2):147-153. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860617715508.

42. Capp R, Misky GJ, Lindrooth RC, et al. Coordination program reduced acute care use and increased primary care visits among frequent emergency care users. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(10):1705-1711. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0612.

43. Kind AJH, Brenny-Fitzpatrick M, Leahy-Gross K, et al. Harnessing protocolized adaptation in dissemination: successful implementation and sustainment of the veterans affairs coordinated-transitional care program in a non-veterans affairs hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(2):409-416. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13935.

44. Kind AJH, Jensen L, Barczi S, et al. Low-cost transitional care with nurse managers making mostly phone contact With patients cut rehospitalization at a VA Hospital. Health Aff. 2012;31(12):2659-2668. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0366.

45. Reese RL, Clement SA, Syeda S, et al. Coordinated-transitional care for veterans with heart failure and chronic lung disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(7):1502-1507. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15978.

As the VA moves toward increased utilization of non-VA care, it is crucial to understand and address the challenges of transitional care faced by dual-use veterans to provide high-quality care that improves healthcare outcomes.7,11,12 The VA implemented a shift in policy from the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 (Public Law 113-146; “Choice Act”) to the VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act beginning June 6, 2019.13,14 Under the MISSION Act, veterans have more ways to access healthcare within the VA’s network and through approved non-VA medical providers in the community known as “community care providers.”15 This shift expanded the existing VA Choice Act of 2014, where the program allowed those veterans who are unable to schedule an appointment within 30 days of their preferred date or the clinically appropriate date, or on the basis of their place of residence, to elect to receive care from eligible non-VA healthcare entities or providers.14,15 These efforts to better serve veterans by increasing non-VA care might present added care coordination challenges for patients and their providers when they seek care in the VA.

High-quality transitional care prevents poor outcomes such as hospital readmissions.16-18 When communication and coordination across healthcare delivery systems are lacking, patients and their families often find themselves at risk for adverse events.19,20 Past research shows that patients have fewer adverse events when they receive comprehensive postdischarge care, including instructions on medications and self-care, symptom recognition and management, and reminders to attend follow-up appointments.17,21,22 Although researchers have identified the components of effective transitional care,23 barriers persist. The communication and collaboration needed to provide coordinated care across healthcare delivery systems are difficult due to the lack of standardized approaches between systems.24 Consequently, follow-up care may be delayed or missed altogether. To our knowledge, there is no published research identifying transitional care challenges for clinicians, staff, and veterans in transitioning from non-VA hospitals to a VA primary care setting.

The objective of this quality assessment was to understand VA and non-VA hospital clinicians’ and staff as well as veterans’ perspectives of the barriers and facilitators to providing high-quality transitional care.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a qualitative assessment within the VA Eastern Colorado Health Care System, an urban tertiary medical center, as well as urban and rural non-VA hospitals used by veterans. Semi-structured interview guides informed by the practical robust implementation and sustainability (PRISM) model, the Lean approach, and the Ideal Transitions of Care Bridge were used.25-27 We explored the PRISM domains such as recipient’s characteristics, the interaction with the external environment, and the implementation and sustainability infrastructure to inform the design and implementation of the intervention.25 The Lean approach included methods to optimize processes by maximizing efficiency and minimizing waste.26 The Ideal Transitions of Care Bridge was used to identify the domains in transitions of care such as discharge planning, communication of information, and care coordination.27

Setting and Participants

We identified the top 10 non-VA hospitals serving the most urban and rural veterans in 2015 using VA administrative data. Purposive sampling was used to ensure that urban and rural non-VA hospitals and different roles within these hospitals were represented. VA clinicians and staff were selected from the Denver VA Medical Center, a tertiary hospital within the Eastern Colorado Health Care System and one VA Community-Based Outpatient Clinic (CBOC) that primarily serves rural veterans. The Denver VA Medical Center has three clinics staffed by Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACTs), a model built on the concept of Patient-Centered Medical Home.28 Hospital leadership were initially approached for permission to recruit their staff and to be involved as key informants, and all agreed. To ensure representativeness, diversity of roles was recruited, including PACT primary care physicians, nurses, and other staff members such as medical assistants and administrators. Veterans were approached for sampling if they were discharged from a non-VA hospital during June–September 2015 and used the VA for primary care. This was to ensure that they remembered the process they went through postdischarge at the time of the interview.

Data Collection and Analysis

The evaluation team members (RA, EL, and MM) conducted the interviews from November 2015 to July 2016. Clinicians, staff, and veterans were asked semi-structured questions about their experiences and their role in transitioning VA patients across systems (see Appendix for interview guides). Veterans were asked to describe their experience and satisfaction with the current postdischarge transition process. We stopped the interviews when we reached data saturation.29

Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and validated (transcribed interviews were double-checked against recording) to ensure data quality and accuracy. Coding was guided by a conventional content analysis technique30, 31 using a deductive and inductive coding approach.31 The deductive coding approach was drawn from the Ideal Transitions of Care Bridge and PRISM domains. 32,33 Two evaluation team members (RA and EL) defined the initial code book by independently coding the first three interviews, worked to clarify the meanings of emergent codes, and came to a consensus when disagreements occurred. Next, a priori codes were added by team members to include the PRISM domains. These PRISM domains included the implementation and sustainability infrastructure, the external environment, the characteristics of intervention recipients, and the organizational and patient perspectives of an intervention.

Additional emergent codes were added to the code book and agreed upon by team members (RA, EL, and MM). Consistent with previously used methods, consensus building was achieved by identifying and resolving differences by discussing with team members (RA, EL, MM, CB, and RB).29 Codes were examined and organized into themes by team members.29,34-36 This process was continued until no new themes were identified. Results were reviewed by all evaluation team members to assess thoroughness and comprehensiveness.34,35 In addition, team members triangulated the findings with VA and non-VA participants to ensure validity and reduce researcher bias.29,37

RESULTS

We conducted a total of 70 interviews with 23 VA and 29 non-VA hospital clinicians and staff and 18 veterans (Table 1). Overall, we found that there was no standardized process for transitioning veterans across healthcare delivery systems. Participants reported that transitions were often inefficient when non-VA hospitals could not (1) identify patients as veterans and notify VA primary care of discharge; (2) transfer non-VA hospital medical records to VA primary care; (3) obtain follow-up care appointments with VA primary care; and (4) write VA formulary medications for veterans to fill at VA pharmacies. In addition, participants discussed about facilitators and suggestions to overcome these inefficiencies and improve transitional care (Table2). We mapped the identified barriers as well as the suggestions for improvement to the PRISM and the Ideal Transitions of Care Bridge domains (Table 3).

Unable to Identify Patients as Veterans and Notify VA Primary Care of Discharge

VA and non-VA participants reported difficulty in communicating about veterans’ hospitalizations and discharge follow-up needs across systems. Non-VA clinicians referenced difficulty in identifying patients as veterans to communicate with VA, except in instances where the VA is a payor, while VA providers described feeling largely uninformed of the veterans non-VA hospitalization. For non-VA clinicians, the lack of a systematic method for veteran identification often left them to inadvertently identify veteran status by asking about their primary care clinicians and insurance and even through an offhanded comment made by the veteran. If a veteran was identified, non-VA clinicians described being uncertain about the best way to notify VA primary care of the patient’s impending discharge. Veterans described instances of the non-VA hospital knowing their veteran status upon admission, but accounts varied on whether the non-VA hospital notified the VA primary care of their hospitalization (Table 2, Theme 1).

Unable to Transfer Non-VA Hospital Medical Records to VA Primary Care

VA clinicians discussed about the challenges associated with obtaining the veteran’s medical record from the non-VA hospitals, and when it was received, it was often incomplete information and significantly delayed. They described relying on the veteran’s description of the care received, which was not complete or accurate information needed to make clinical judgment or coordinate follow-up care. Non-VA clinicians mentioned about trying several methods for transferring the medical record to VA primary care, including discharge summary via electronic system and sometimes solely relying on patients to deliver discharge paperwork to their primary care clinicians. In instances where non-VA hospitals sent discharge paperwork to VA, there was no way for non-VA hospitals to verify whether the faxed electronic medical record was received by the VA hospital. Most of the veterans discussed receiving written postdischarge instructions to take to their VA primary care clinicians; however, they were unsure whether the VA primary care received their medical record or any other information from the non-VA hospital (Table 2, Theme 2).

Unable to Obtain Follow-Up Care Appointments with VA Primary Care

All participants described how difficult it was to obtain a follow-up appointment for veterans with VA primary care. This often resulted in delayed follow-up care. VA clinicians also shared that a non-VA hospitalization can be the impetus for a veteran to seek care at the VA for the very first time. Once eligibility is determined, the veteran is assigned a VA primary care clinician. This process may take up to six weeks, and in the meantime, the veteran is scheduled in VA urgent care for immediate postdischarge care. This lag in primary care assignment creates delayed and fragmented care (Table 2, Theme 3).

Non-VA clinicians, administrators, and staff also discussed the difficulties in scheduling follow-up care with VA primary care. Although discharge paperwork instructed patients to see their VA clinicians, there was no process in place for non-VA clinicians to confirm whether the follow-up care was received due to lack of bilateral communication. In addition, veterans discussed the inefficiencies in scheduling follow-up appointments with VA clinicians where attempts to follow-up with primary care clinicians took eight weeks or more. Several veterans described walking into the clinic without an appointment asking to be seen postdischarge or utilizing the VA emergency department for follow-up care after discharge from a non-VA hospital. Veterans admitted utilizing the VA emergency department for nonemergent reasons such as filling their prescriptions because they are unable to see a VA PCP in a timely manner (Table 2, Theme 3).

Unable to Write VA Formulary Medications for Veterans to Fill at VA Pharmacies

All participants described the difficulties in obtaining medications at VA pharmacies when prescribed by the non-VA hospital clinicians. VA clinicians often had to reassess, and rewrite prescriptions written by clinicians, causing delays. Moreover, rural VA clinicians described lack of VA pharmacies in their locations, where veterans had to mail order medications, causing further delays in needed medications. Non-VA clinicians echoed these frustrations. They noted that veterans were confused about their VA pharmacy benefits as well as the need for the non-VA clinicians to follow VA formulary guidelines. Veterans expressed that it was especially challenging to physically go to the VA pharmacy to pick up medications after discharge due to lack of transportation, limited VA pharmacy hours, and long wait times. Several veterans discussed paying for their prescriptions out of pocket even though they had VA pharmacy benefits because it was more convenient to use the non-VA pharmacy. In other instances, veterans discussed going to a VA emergency department and waiting for hours to have their non-VA clinician prescription rewritten by a VA clinician (Table 2, Theme 4).

Facilitators of the Current Transition Process

Several participants provided examples of when transitional care communication between systems occurred seamlessly. VA staff and veterans noted that the VA increased the availability of urgent care appointments, which allowed for timelier postacute care follow-up appointments. Non-VA hospital clinicians also noted the availability of additional appointment slots but stated that they did not learn about these additional appointments directly from the VA. Instead, they learned of these through medical residents caring for patients at both VA and non-VA hospitals. One VA CBOC designated two nurses to care for walk-in veterans for their postdischarge follow-up needs. Some VA participants also noted that the VA Call Center Nurses occasionally called veterans upon discharge to schedule a follow-up appointment and facilitated timely care.

Participants from a VA CBOC discussed being part of a Community Transitions Consortium aimed at identifying high-utilizing patients (veteran and nonveteran) and improving communication across systems. The consortium members discussed each facility’s transition-of-care process, described having access to local non-VA hospital medical records and a backline phone number at the non-VA hospitals to coordinate transitional care. This allowed the VA clinicians to learn about non-VA hospital processes and veteran needs.

Suggestions for Improving the Transitional Care Process

VA and non-VA clinicians suggested hiring a VA liaison, preferably with a clinical background to facilitate care coordination across healthcare systems. They recommended that this person work closely with VA primary care, strengthen the relationship with non-VA hospitals, and help veterans learn more about the transition-of-care processes. Topics discussed for veteran education included how to (1) access their primary care tea

Veterans agreed that improvements to the current process should include an efficient system for obtaining medications and the ability to schedule timely follow-up appointments. Furthermore, veterans wanted education about the VA transition-of-care process following a non-VA hospitalization, including payment and VA notification processes (Table 2, Theme 5).

DISCUSSION

Participants described the current transitional care process as inefficient with specific barriers that have negative consequences on patient care and clinician and staff work processes. They described difficulties in obtaining medications prescribed by non-VA clinicians from VA pharmacies, delays in follow-up appointments at the VA, and lack of bilateral communication between systems and medical record transfer. Participants also provided concrete suggestions to improving the current process, including a care coordinator with clinical background. These findings are important in the context of VA increasing veteran access to care in the community.

Despite an increasing emphasis on veteran access to non-VA care as a result of the VA strategic goals and several new programs,7,12,13 there has not been a close examination of the current transition-of-care process from non-VA hospitals to VA primary care. Several studies have shown that the period following a hospitalization is especially vulnerable and associated with adverse events such as readmission, high cost, and death.12,31,32 Our findings agree with previous research that identified medical record transfer across systems as one of the most challenging issues contributing to deficits in communication between care teams.33 In addition, our study brought into focus the significant challenges faced by veterans in obtaining medications post non-VA hospital discharge. Addressing these key barriers in transitional care will improve the quality, safety, and value of healthcare in the current transition process.38,39

Based on our findings, our participants’ concern in transitional care can be addressed in various ways. First, as veterans are increasingly receiving care in the community, identifying their veteran status early on in the non-VA hospital setting could help in improved, real time communication with the VA. This could be done by updating patient intake forms to ask patients whether they are veterans or not. Second, VA policy-level changes should work to provide veterans access to non-VA pharmacy benefits equivalent to the access patients are receiving for hospital, specialty, and outpatient care. Third, patient and provider satisfaction for dual-use veterans should be examined closely. Although participants expressed frustration with the overall transitions of care from non-VA hospitals to VA primary care setting, influence of this on the Quadruple Aim-improving patient outcomes, experience, and reducing clinician and staff burnout should be examined closely.40 Fourth, evidence-based interventions such as nurse-led transitional care programs that have proven helpful in reducing adverse outcomes in both VA and non-VA settings will be useful to implement.41-45 Such programs could be located in the VA, and a care coordinator role could help facilitate transitional care needs for veterans by working with multiple non-VA hospitals.

The limitations of this study are that the perspectives shared by these participants may not represent all VA and non-VA hospitals as well as veterans’ experiences with transition of care. In addition, the study was conducted in one state and the findings may not be applicable to other healthcare systems. However, our study highlighted the consistent challenges of receiving care across VA and other hospital systems. Two strengths of this study are that it was conducted by multidisciplinary research team members with expertise in qualitative research, clinical care, and implementation science and that we obtained convergent information from VA, non-VA, and veteran participants.

Our current transition-of-care process has several shortcomings. There was a clear agreement on barriers, facilitators, and suggestions for improving the current transitions-of-care process among VA and non-VA hospital participants, as well as from veterans who experienced transitions across different delivery systems. Transitioning veterans to VA primary care following a non-VA hospitalization is a crucial first step for improving care for veterans and reducing adverse outcomes such as avoidable hospital readmissions and death.

These results describe the inefficiencies experienced by patients, clinicians, and staff and their suggestions to alleviate these barriers for optimal continuum of care. To avoid frustration and inefficiencies, the increased emphasis of providing non-VA care for veterans should consider the challenges experienced in transitional care and the opportunities for increased coordination of care.

As the VA moves toward increased utilization of non-VA care, it is crucial to understand and address the challenges of transitional care faced by dual-use veterans to provide high-quality care that improves healthcare outcomes.7,11,12 The VA implemented a shift in policy from the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 (Public Law 113-146; “Choice Act”) to the VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act beginning June 6, 2019.13,14 Under the MISSION Act, veterans have more ways to access healthcare within the VA’s network and through approved non-VA medical providers in the community known as “community care providers.”15 This shift expanded the existing VA Choice Act of 2014, where the program allowed those veterans who are unable to schedule an appointment within 30 days of their preferred date or the clinically appropriate date, or on the basis of their place of residence, to elect to receive care from eligible non-VA healthcare entities or providers.14,15 These efforts to better serve veterans by increasing non-VA care might present added care coordination challenges for patients and their providers when they seek care in the VA.

High-quality transitional care prevents poor outcomes such as hospital readmissions.16-18 When communication and coordination across healthcare delivery systems are lacking, patients and their families often find themselves at risk for adverse events.19,20 Past research shows that patients have fewer adverse events when they receive comprehensive postdischarge care, including instructions on medications and self-care, symptom recognition and management, and reminders to attend follow-up appointments.17,21,22 Although researchers have identified the components of effective transitional care,23 barriers persist. The communication and collaboration needed to provide coordinated care across healthcare delivery systems are difficult due to the lack of standardized approaches between systems.24 Consequently, follow-up care may be delayed or missed altogether. To our knowledge, there is no published research identifying transitional care challenges for clinicians, staff, and veterans in transitioning from non-VA hospitals to a VA primary care setting.

The objective of this quality assessment was to understand VA and non-VA hospital clinicians’ and staff as well as veterans’ perspectives of the barriers and facilitators to providing high-quality transitional care.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a qualitative assessment within the VA Eastern Colorado Health Care System, an urban tertiary medical center, as well as urban and rural non-VA hospitals used by veterans. Semi-structured interview guides informed by the practical robust implementation and sustainability (PRISM) model, the Lean approach, and the Ideal Transitions of Care Bridge were used.25-27 We explored the PRISM domains such as recipient’s characteristics, the interaction with the external environment, and the implementation and sustainability infrastructure to inform the design and implementation of the intervention.25 The Lean approach included methods to optimize processes by maximizing efficiency and minimizing waste.26 The Ideal Transitions of Care Bridge was used to identify the domains in transitions of care such as discharge planning, communication of information, and care coordination.27

Setting and Participants

We identified the top 10 non-VA hospitals serving the most urban and rural veterans in 2015 using VA administrative data. Purposive sampling was used to ensure that urban and rural non-VA hospitals and different roles within these hospitals were represented. VA clinicians and staff were selected from the Denver VA Medical Center, a tertiary hospital within the Eastern Colorado Health Care System and one VA Community-Based Outpatient Clinic (CBOC) that primarily serves rural veterans. The Denver VA Medical Center has three clinics staffed by Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACTs), a model built on the concept of Patient-Centered Medical Home.28 Hospital leadership were initially approached for permission to recruit their staff and to be involved as key informants, and all agreed. To ensure representativeness, diversity of roles was recruited, including PACT primary care physicians, nurses, and other staff members such as medical assistants and administrators. Veterans were approached for sampling if they were discharged from a non-VA hospital during June–September 2015 and used the VA for primary care. This was to ensure that they remembered the process they went through postdischarge at the time of the interview.

Data Collection and Analysis

The evaluation team members (RA, EL, and MM) conducted the interviews from November 2015 to July 2016. Clinicians, staff, and veterans were asked semi-structured questions about their experiences and their role in transitioning VA patients across systems (see Appendix for interview guides). Veterans were asked to describe their experience and satisfaction with the current postdischarge transition process. We stopped the interviews when we reached data saturation.29

Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and validated (transcribed interviews were double-checked against recording) to ensure data quality and accuracy. Coding was guided by a conventional content analysis technique30, 31 using a deductive and inductive coding approach.31 The deductive coding approach was drawn from the Ideal Transitions of Care Bridge and PRISM domains. 32,33 Two evaluation team members (RA and EL) defined the initial code book by independently coding the first three interviews, worked to clarify the meanings of emergent codes, and came to a consensus when disagreements occurred. Next, a priori codes were added by team members to include the PRISM domains. These PRISM domains included the implementation and sustainability infrastructure, the external environment, the characteristics of intervention recipients, and the organizational and patient perspectives of an intervention.

Additional emergent codes were added to the code book and agreed upon by team members (RA, EL, and MM). Consistent with previously used methods, consensus building was achieved by identifying and resolving differences by discussing with team members (RA, EL, MM, CB, and RB).29 Codes were examined and organized into themes by team members.29,34-36 This process was continued until no new themes were identified. Results were reviewed by all evaluation team members to assess thoroughness and comprehensiveness.34,35 In addition, team members triangulated the findings with VA and non-VA participants to ensure validity and reduce researcher bias.29,37

RESULTS

We conducted a total of 70 interviews with 23 VA and 29 non-VA hospital clinicians and staff and 18 veterans (Table 1). Overall, we found that there was no standardized process for transitioning veterans across healthcare delivery systems. Participants reported that transitions were often inefficient when non-VA hospitals could not (1) identify patients as veterans and notify VA primary care of discharge; (2) transfer non-VA hospital medical records to VA primary care; (3) obtain follow-up care appointments with VA primary care; and (4) write VA formulary medications for veterans to fill at VA pharmacies. In addition, participants discussed about facilitators and suggestions to overcome these inefficiencies and improve transitional care (Table2). We mapped the identified barriers as well as the suggestions for improvement to the PRISM and the Ideal Transitions of Care Bridge domains (Table 3).

Unable to Identify Patients as Veterans and Notify VA Primary Care of Discharge

VA and non-VA participants reported difficulty in communicating about veterans’ hospitalizations and discharge follow-up needs across systems. Non-VA clinicians referenced difficulty in identifying patients as veterans to communicate with VA, except in instances where the VA is a payor, while VA providers described feeling largely uninformed of the veterans non-VA hospitalization. For non-VA clinicians, the lack of a systematic method for veteran identification often left them to inadvertently identify veteran status by asking about their primary care clinicians and insurance and even through an offhanded comment made by the veteran. If a veteran was identified, non-VA clinicians described being uncertain about the best way to notify VA primary care of the patient’s impending discharge. Veterans described instances of the non-VA hospital knowing their veteran status upon admission, but accounts varied on whether the non-VA hospital notified the VA primary care of their hospitalization (Table 2, Theme 1).

Unable to Transfer Non-VA Hospital Medical Records to VA Primary Care

VA clinicians discussed about the challenges associated with obtaining the veteran’s medical record from the non-VA hospitals, and when it was received, it was often incomplete information and significantly delayed. They described relying on the veteran’s description of the care received, which was not complete or accurate information needed to make clinical judgment or coordinate follow-up care. Non-VA clinicians mentioned about trying several methods for transferring the medical record to VA primary care, including discharge summary via electronic system and sometimes solely relying on patients to deliver discharge paperwork to their primary care clinicians. In instances where non-VA hospitals sent discharge paperwork to VA, there was no way for non-VA hospitals to verify whether the faxed electronic medical record was received by the VA hospital. Most of the veterans discussed receiving written postdischarge instructions to take to their VA primary care clinicians; however, they were unsure whether the VA primary care received their medical record or any other information from the non-VA hospital (Table 2, Theme 2).

Unable to Obtain Follow-Up Care Appointments with VA Primary Care

All participants described how difficult it was to obtain a follow-up appointment for veterans with VA primary care. This often resulted in delayed follow-up care. VA clinicians also shared that a non-VA hospitalization can be the impetus for a veteran to seek care at the VA for the very first time. Once eligibility is determined, the veteran is assigned a VA primary care clinician. This process may take up to six weeks, and in the meantime, the veteran is scheduled in VA urgent care for immediate postdischarge care. This lag in primary care assignment creates delayed and fragmented care (Table 2, Theme 3).

Non-VA clinicians, administrators, and staff also discussed the difficulties in scheduling follow-up care with VA primary care. Although discharge paperwork instructed patients to see their VA clinicians, there was no process in place for non-VA clinicians to confirm whether the follow-up care was received due to lack of bilateral communication. In addition, veterans discussed the inefficiencies in scheduling follow-up appointments with VA clinicians where attempts to follow-up with primary care clinicians took eight weeks or more. Several veterans described walking into the clinic without an appointment asking to be seen postdischarge or utilizing the VA emergency department for follow-up care after discharge from a non-VA hospital. Veterans admitted utilizing the VA emergency department for nonemergent reasons such as filling their prescriptions because they are unable to see a VA PCP in a timely manner (Table 2, Theme 3).

Unable to Write VA Formulary Medications for Veterans to Fill at VA Pharmacies

All participants described the difficulties in obtaining medications at VA pharmacies when prescribed by the non-VA hospital clinicians. VA clinicians often had to reassess, and rewrite prescriptions written by clinicians, causing delays. Moreover, rural VA clinicians described lack of VA pharmacies in their locations, where veterans had to mail order medications, causing further delays in needed medications. Non-VA clinicians echoed these frustrations. They noted that veterans were confused about their VA pharmacy benefits as well as the need for the non-VA clinicians to follow VA formulary guidelines. Veterans expressed that it was especially challenging to physically go to the VA pharmacy to pick up medications after discharge due to lack of transportation, limited VA pharmacy hours, and long wait times. Several veterans discussed paying for their prescriptions out of pocket even though they had VA pharmacy benefits because it was more convenient to use the non-VA pharmacy. In other instances, veterans discussed going to a VA emergency department and waiting for hours to have their non-VA clinician prescription rewritten by a VA clinician (Table 2, Theme 4).

Facilitators of the Current Transition Process

Several participants provided examples of when transitional care communication between systems occurred seamlessly. VA staff and veterans noted that the VA increased the availability of urgent care appointments, which allowed for timelier postacute care follow-up appointments. Non-VA hospital clinicians also noted the availability of additional appointment slots but stated that they did not learn about these additional appointments directly from the VA. Instead, they learned of these through medical residents caring for patients at both VA and non-VA hospitals. One VA CBOC designated two nurses to care for walk-in veterans for their postdischarge follow-up needs. Some VA participants also noted that the VA Call Center Nurses occasionally called veterans upon discharge to schedule a follow-up appointment and facilitated timely care.

Participants from a VA CBOC discussed being part of a Community Transitions Consortium aimed at identifying high-utilizing patients (veteran and nonveteran) and improving communication across systems. The consortium members discussed each facility’s transition-of-care process, described having access to local non-VA hospital medical records and a backline phone number at the non-VA hospitals to coordinate transitional care. This allowed the VA clinicians to learn about non-VA hospital processes and veteran needs.

Suggestions for Improving the Transitional Care Process

VA and non-VA clinicians suggested hiring a VA liaison, preferably with a clinical background to facilitate care coordination across healthcare systems. They recommended that this person work closely with VA primary care, strengthen the relationship with non-VA hospitals, and help veterans learn more about the transition-of-care processes. Topics discussed for veteran education included how to (1) access their primary care tea

Veterans agreed that improvements to the current process should include an efficient system for obtaining medications and the ability to schedule timely follow-up appointments. Furthermore, veterans wanted education about the VA transition-of-care process following a non-VA hospitalization, including payment and VA notification processes (Table 2, Theme 5).

DISCUSSION

Participants described the current transitional care process as inefficient with specific barriers that have negative consequences on patient care and clinician and staff work processes. They described difficulties in obtaining medications prescribed by non-VA clinicians from VA pharmacies, delays in follow-up appointments at the VA, and lack of bilateral communication between systems and medical record transfer. Participants also provided concrete suggestions to improving the current process, including a care coordinator with clinical background. These findings are important in the context of VA increasing veteran access to care in the community.

Despite an increasing emphasis on veteran access to non-VA care as a result of the VA strategic goals and several new programs,7,12,13 there has not been a close examination of the current transition-of-care process from non-VA hospitals to VA primary care. Several studies have shown that the period following a hospitalization is especially vulnerable and associated with adverse events such as readmission, high cost, and death.12,31,32 Our findings agree with previous research that identified medical record transfer across systems as one of the most challenging issues contributing to deficits in communication between care teams.33 In addition, our study brought into focus the significant challenges faced by veterans in obtaining medications post non-VA hospital discharge. Addressing these key barriers in transitional care will improve the quality, safety, and value of healthcare in the current transition process.38,39

Based on our findings, our participants’ concern in transitional care can be addressed in various ways. First, as veterans are increasingly receiving care in the community, identifying their veteran status early on in the non-VA hospital setting could help in improved, real time communication with the VA. This could be done by updating patient intake forms to ask patients whether they are veterans or not. Second, VA policy-level changes should work to provide veterans access to non-VA pharmacy benefits equivalent to the access patients are receiving for hospital, specialty, and outpatient care. Third, patient and provider satisfaction for dual-use veterans should be examined closely. Although participants expressed frustration with the overall transitions of care from non-VA hospitals to VA primary care setting, influence of this on the Quadruple Aim-improving patient outcomes, experience, and reducing clinician and staff burnout should be examined closely.40 Fourth, evidence-based interventions such as nurse-led transitional care programs that have proven helpful in reducing adverse outcomes in both VA and non-VA settings will be useful to implement.41-45 Such programs could be located in the VA, and a care coordinator role could help facilitate transitional care needs for veterans by working with multiple non-VA hospitals.

The limitations of this study are that the perspectives shared by these participants may not represent all VA and non-VA hospitals as well as veterans’ experiences with transition of care. In addition, the study was conducted in one state and the findings may not be applicable to other healthcare systems. However, our study highlighted the consistent challenges of receiving care across VA and other hospital systems. Two strengths of this study are that it was conducted by multidisciplinary research team members with expertise in qualitative research, clinical care, and implementation science and that we obtained convergent information from VA, non-VA, and veteran participants.

Our current transition-of-care process has several shortcomings. There was a clear agreement on barriers, facilitators, and suggestions for improving the current transitions-of-care process among VA and non-VA hospital participants, as well as from veterans who experienced transitions across different delivery systems. Transitioning veterans to VA primary care following a non-VA hospitalization is a crucial first step for improving care for veterans and reducing adverse outcomes such as avoidable hospital readmissions and death.

These results describe the inefficiencies experienced by patients, clinicians, and staff and their suggestions to alleviate these barriers for optimal continuum of care. To avoid frustration and inefficiencies, the increased emphasis of providing non-VA care for veterans should consider the challenges experienced in transitional care and the opportunities for increased coordination of care.

1. Borowsky SJ, Cowper DC. Dual use of VA and non-VA primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(5):274-280. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00335.x.

2. Charlton ME, Mengeling MA, Schlichting JA, et al. Veteran use of health care systems in rural states. Comparing VA and Non-VA health care use among privately insured veterans under age 65. J Rural Health. 2016;32(4):407-417. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12206.

3. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007.

4. Nguyen KA, Haggstrom DA, Ofner S, et al. Medication use among veterans across health care systems. Appl Clin Inform. 2017;26(1):235-249. https://doi.org/10.4338/ACI-2016-10-RA-0184.

5. Nayar P, Apenteng B, Yu F, Woodbridge P, Fetrick A. Rural veterans’ perspectives of dual care. J Commun Health. 2013;38(1):70-77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-012-9583-7.

6. West AN, Charlton ME. Insured veterans’ use of VA and Non-VA health care in a rural state. J Rural Health. 2016;32(4):387-396. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12196.

7. Gellad WF. The veterans choice act and dual health system use. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(2):153-154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3492-2.

8. Axon RN, Gebregziabher M, Everett CJ, Heidenreich P, Hunt KJ. Dual health care system use is associated with higher rates of hospitalization and hospital readmission among veterans with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2016;174:157-163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2015.09.023.

9. Humensky J, Carretta H, de Groot K, et al. Service utilization of veterans dually eligible for VA and medicare fee-for-service: 1999–2004. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2012;2(3). https://doi.org/10.5600/mmrr.002.03.A06.

10. West AN, Charlton ME, Vaughan-Sarrazin M. Dual use of VA and non-VA hospitals by veterans with multiple hospitalizations. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):431. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1069-8.

11. Gaglioti A, Cozad A, Wittrock S, et al. Non-VA primary care providers’ perspectives on comanagement for rural veterans. Mil Med. 2014;179(11):1236-1243. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00342.

12. Department of Veterans Affairs. Expanded access to non-VA care through the veterans choice program. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2018;83(92):21893-21897.

13. Shuster B. Text-H.R.3236-114th Congress. Surface Transportation and Veterans Health Care Choice Improvement Act of 2015.. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/3236/text/pl. Accessed April 16, 2017; 2015-2016.

14. Veterans Affairs Mission Act. MISSIONAct.va.gov Available at. https://missionact.va.gov/. Accessed August 9, 2019.

15. Veterans Choice Program (VCP). Community care. https://www.va.gov/COMMUNITYCARE/programs/veterans/VCP/index.asp. Accessed August 9, 2019.

16. A Decade of Transitional Care Research with Vulnerable Elder… : journal of cardiovascular nursing. LWW. http://journals.lww.com/jcnjournal/Fulltext/2000/04000/A_Decade_of_Transitional_Care_Research_with.4.aspx. Accessed April 16, 2017.

17. Coleman EA, Boult C. Improving the quality of transitional care for persons with complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):556-557. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51186.x.

18. Krichbaum K. GAPN postacute care coordination improves hip fracture outcomes. West J Nurs Res. 2007;29(5):523-544. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945906293817.

19. Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL, Coleman EA. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):314-323. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.228.

20. Coleman EA, Mahoney E, Parry C. Assessing the quality of preparation for posthospital care from the patient’s perspective: the care transitions measure. Med Care. 2005;43(3):246-255. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200503000-00007.

21. Naylor MD, Aiken LH, Kurtzman ET, Olds DM, Hirschman KB. The importance of transitional care in achieving health reform. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(4):746-754. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0041.

22. Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, et al. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(5):675-684. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52202.x.

23. Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of care consensus policy statement: American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, society of hospital medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(6):364-370. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.510.

24. Coleman EA. Falling through the cracks: challenges and opportunities for improving transitional care for persons with continuous complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):549-555. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51185.x.

25. Feldstein AC, Glasgow RE. A practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) for integrating research findings into practice. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(4):228-243. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1553-7250(08)34030-6.

26. Schweikhart SA, Dembe AE. The applicability of lean and six sigma techniques to clinical and translational research. J Investig Med. 2009;57(7):748-755. https://doi.org/10.2310/JIM.0b013e3181b91b3a.

27. Burke RE, Kripalani S, Vasilevskis EE, Schnipper JL. Moving beyond readmission penalties: creating an ideal process to improve transitional care. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(2):102-109. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1990.

28. Patient Aligned Care Team (PACT)-Patient Care. Services. https://www.patientcare.va.gov/primarycare/PACT.asp. Accessed November 20, 2017.

29. Morse JM. Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(9):1212-1222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315588501.

30. Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277-1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

31. Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5(1):80-92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107.

32. Ayele RA, Lawrence E, McCreight M, et al. Study protocol: improving the transition of care from a non-network hospital back to the patient’s medical home. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):123. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2048-z.

33. Burke RE, Kripalani S, Vasilevskis EE, Schnipper JL. Moving beyond readmission penalties: creating an ideal process to improve transitional care. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(2):102-109. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1990.

34. Qualitative research & evaluation methods. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/qualitative-research-evaluation-methods/book232962. Accessed April 16, 2017. SAGE Publications Inc.

35. Curry LA, Nembhard IM, Bradley EH. Qualitative and mixed methods provide unique contributions to outcomes research. Circulation. 2009;119(10):1442-1452. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.742775.

36. Creswell JW, Hanson WE, Clark Plano VL, Morales A. Qualitative research designs: selection and implementation. Couns Psychol. 2007;35(2):236-264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006287390.

37. Carter N, Bryant-Lukosius D, DiCenso A, Blythe J, Neville AJ. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41(5):545-547. https://doi.org/10.1188/14.ONF.545-547.

38. Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome—an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):100-102. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1212324.

39. Improving Care Transitions. Health affairs-health policy briefs. http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=76. Accessed August 13, 2016.

40. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573-576. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1713.

41. Burke RE, Kelley L, Gunzburger E, et al. Improving transitions of care for veterans transferred to tertiary VA medical centers. Am J Med Qual. 2018;33(2):147-153. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860617715508.

42. Capp R, Misky GJ, Lindrooth RC, et al. Coordination program reduced acute care use and increased primary care visits among frequent emergency care users. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(10):1705-1711. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0612.

43. Kind AJH, Brenny-Fitzpatrick M, Leahy-Gross K, et al. Harnessing protocolized adaptation in dissemination: successful implementation and sustainment of the veterans affairs coordinated-transitional care program in a non-veterans affairs hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(2):409-416. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13935.

44. Kind AJH, Jensen L, Barczi S, et al. Low-cost transitional care with nurse managers making mostly phone contact With patients cut rehospitalization at a VA Hospital. Health Aff. 2012;31(12):2659-2668. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0366.

45. Reese RL, Clement SA, Syeda S, et al. Coordinated-transitional care for veterans with heart failure and chronic lung disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(7):1502-1507. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15978.

1. Borowsky SJ, Cowper DC. Dual use of VA and non-VA primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(5):274-280. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00335.x.

2. Charlton ME, Mengeling MA, Schlichting JA, et al. Veteran use of health care systems in rural states. Comparing VA and Non-VA health care use among privately insured veterans under age 65. J Rural Health. 2016;32(4):407-417. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12206.

3. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007.

4. Nguyen KA, Haggstrom DA, Ofner S, et al. Medication use among veterans across health care systems. Appl Clin Inform. 2017;26(1):235-249. https://doi.org/10.4338/ACI-2016-10-RA-0184.

5. Nayar P, Apenteng B, Yu F, Woodbridge P, Fetrick A. Rural veterans’ perspectives of dual care. J Commun Health. 2013;38(1):70-77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-012-9583-7.