User login

Ready to Go Home? Assessment of Shared Mental Models of the Patient and Discharging Team Regarding Readiness for Hospital Discharge

Preparing patients for hospital discharge requires multiple tasks that cross professional boundaries. Clinician’s roles may be ambiguous, and responsibility for a safe high-quality discharge is often diffused among the team rather than being defined as the core responsibility of a single member.1-8 Without a shared understanding of patient resources and tasks involved in anticipatory planning, lapses in discharge preparation can occur, which places patients at increased risk for harm after hospitalization.3-7 As a result, organizations like the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) have called for team-based patient-centered discharge planning.8 Yet to develop more effective team-based discharge planning interventions, a more nuanced understanding of how healthcare teams work together is needed.2,3,9

Shared mental models (SMMs) provide a useful theoretical framework and measurement approach for examining how interprofessional teams coordinate complex tasks like hospital discharge.10-13 SMMs represent the team members’ collective understanding and organized knowledge of key elements needed for teams to perform effectively.9-11 Validated questionnaires can be used to measure two key properties of SMMs: the degree to which team members have a similar understanding of the situation at hand (team SMM convergence) and to what extent this understanding is aligned with the patient (team-patient SMM convergence).10,11 Researchers have found that teams with higher-quality SMMs have a better understanding of what is happening and why, have clearer expectations of their roles and tasks, and can better predict what might happen next.10,12 As a result, these teams more effectively coordinate actions and adapt to task demands even in cases of high complexity, uncertainty, and stress.10-13 Prior studies examining healthcare teams in emergency departments,14-16 critical care units,17,18 and operating rooms19 suggest high-quality SMMs are needed to safely care for patients.13 Yet there has been limited evaluation of SMMs in general internal medicine, much less during hospital discharge.9,13 The purpose of this study was to examine SMMs for a critical task of the inpatient team: developing a shared understanding of the patient’s readiness for hospital discharge.20,21

METHODS

Design

We used a cross-sectional survey design at a single Midwestern community hospital to determine inpatient care teams’ SMMs of patient hospital discharge readiness. This study is part of a larger mixed-methods evaluation of interprofessional hospital discharge teamwork in older adult patients at risk for a poor transition to home.9 Data were collected using questionnaires from patients and their team (nurse, coordinator, and physician) within 4 hours of the patient leaving the hospital. First, we measured the teams’ assessment, team convergence, and team-patient convergence on patient readiness for discharge from the hospital. Then, after identifying relevant potential predictors from the literature, we developed regression models to predict the teams’ assessment, team convergence, and team-patient convergence of discharge readiness based on these variables. Our local institutional review board approved this study.

Sample and Participants

We used a convenience sampling approach to identify eligible discharge events consisting of the patient and care team.9 We focused on patients at high-risk for poor hospital-to-home transitions.3,22 Eligible events included older patients (≥65 years) who were discharged home without home health or hospice services and admitted with a primary diagnosis of heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, hip replacement, knee replacement, pneumonia, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Patient exclusion criteria included inability to complete study forms because of mental incapacity or a language barrier. Discharge team member inclusion criteria included the bedside nurse, attending physician, and coordinator (a unit-dedicated discharge nurse or social worker) caring for the patient participant at the time of hospital discharge. Each discharge team was unique: The same three individuals could not be included as a “team” for more than one discharge event, although individual members could be included as a part of other teams with a different set of individuals. Appendix A provides an enrollment flowchart.

Conceptual Framework

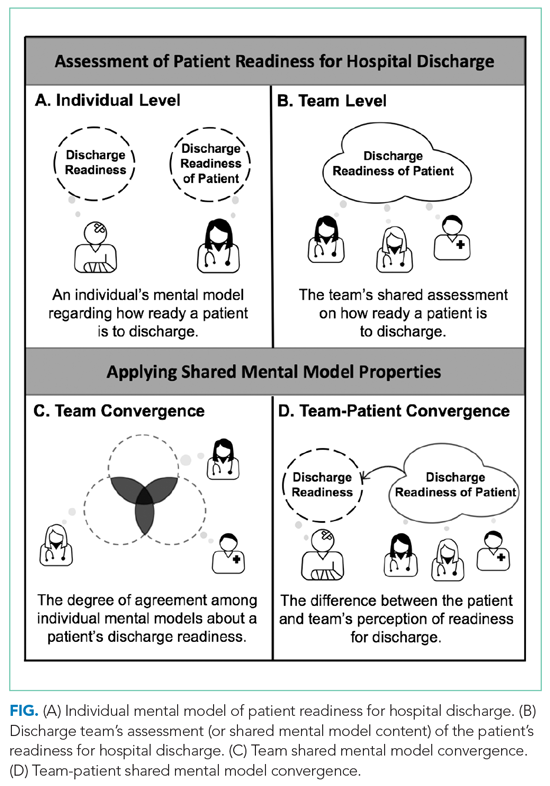

We applied the SMM conceptual framework to the context of hospital discharge. As shown in the Figure, SMMs are examined at the team level and contain the critical knowledge held by the team to be effective.15,16 From a patient-centered perspective, patients are considered the expert on how ready they feel to be discharged home.20,23,24 In this case, the SMM content is the discharge team members’ shared assessment of how ready the patient is for hospital discharge (Figure, B).10 Convergence is the degree of agreement among individual mental models.10-13 In this study we examined two types of convergence: (1) team convergence, or the team members degree of agreement on the patient’s readiness for discharge (Figure, C), and (2) team-patient convergence, or the degree to which the team’s SMM aligns with the patient’s mental model (Figure, D).10-13

Measures and Variables

Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scales/Short Form

We used parallel clinician and patient versions of the Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scale/Short Form (RHDS/SF)25-28 to determine the teams’ assessment of discharge readiness, team SMM convergence, and team-patient SMM convergence.

The RHDS/SF scales are 8-item validated instruments that use a Likert scale (0 for not ready to 10 for totally ready) to assess the individual clinician’s or patient’s perceptions of how ready the patient is to be discharged.20,25,27 The RHDS/SF instruments include four dimensions conceptualized as crucial to patient readiness for discharge and important to anticipatory planning: (1) Personal Status, physical-emotional state of the patient before discharge; (2) Knowledge, perceived adequacy of information needed to respond to common posthospitalization concerns/problems; (3) Coping Ability, perceived ability to self-manage health care needs; and (4) Expected Support, emotional-physical assistance available (Appendix B).20,25,27 The RHDS/SF instruments’ results are calculated as a mean of item scores, with higher individual scores indicating the rater assessed the patient as being more ready for hospital discharge.20 The RHDS/SF scales have undergone rigorous psychometric testing and are linked to patient outcomes (eg, readmissions, emergency room visits, patient coping difficulties after discharge, and patient-rated quality of preparation for posthospital care).20,25-28 For example, predictive validity assessments for adult medical-surgical patients found lower Nurse-RHDS/SF scores are associated with a six- to ninefold increase in 30-day readmission risk.20

Contextual Variables

We reviewed the literature to identify potential patient and system factors associated with adverse transitional care outcomes1-8 and/or higher quality SMMs in other settings.10-19 For example, patient characteristics included age, principal diagnosis, length of stay, number of comorbidities, and cognition impairment (using the Short Portable Mini Mental Status Questionnaire29).2,22,30 Examples of system factor include teamwork and communication quality1-6 on day of discharge, as well as educational background and experience of clinicians on the team.31-33 We adapted a validated survey using 7-point Likert scale questions to determine teamwork quality and communication quality during individual patent discharges.33Appendix C provides descriptions of all variables.

Data Collection

Patient recruitment occurred from February to October 2017 in a single community hospital in Iowa.9 We identified potentially eligible events in collaboration with the unit charge nurses. Patients were screened 24 to 48 hours prior to anticipated day of discharge; those interested/eligible underwent informed consent procedures.9 We collected data from the patient and their corresponding bedside nurse, coordinator, and attending physician on the day of discharge. After the discharge order was placed and care instructions were provided, the patient completed a demographic survey, Short Portable Mini Mental Status Questionnaire, and the Patient-RHDS/SF. Individual team members completed a survey with the demographic information, their respective versions of RHDS/SF, and day-of-discharge teamwork-related questions. On average, the survey took clinicians less than 5 minutes to complete. We performed a chart review to determine additional patient characteristics such as principal diagnosis, length of stay, and number of comorbidities.

Data Analysis

Team Assessment of Patient Discharge Readiness

The teams’ shared assessment (SMM content) was determined by averaging the members’ individual scores on the Clinician-RHDS/SF.34 Discharge events with higher team assessments indicated the team perceived the patient as being readier for hospital discharge. Guided by prior research, we examined the RHDS/SF scores as a continuous variable and as a four-level categorical variable of readiness: low (<7), moderate (7-7.9), high (8-8.9), and very high (9-10).20

Team SMM Convergence

To determine the teams’ convergence on patient discharge readiness, we calculated an adjusted interrater agreement index (r*wg(j))35,36 for each team using the individual clinicians’ scores on the RHDS/SF. These convergence values were categorized into four agreement levels: low agreement (<0.7), moderate agreement (0.7-0.79), high agreement (0.8-0.89), and very high agreement (0.9-1). See Appendix D for the r*wg(j) equation.35,36

Team-Patient SMM Convergence

To determine the team-patient SMM convergence, we subtracted the team’s assessment of patient discharge readiness from the Patient-RHDS/SF score. We used a one-unit change on the RHDS/SF (1 point on the 0-10 scale) as a meaningful difference between the patient’s self-assessment and teams’ assessment on readiness for hospital discharge. This definition for divergence aligns with prior RHDS psychometric testing studies20,27 and research examining convergence between patient and nurse assessments.28 For example, Weiss and colleagues27 found a 1-point decrease in the RN-RHDS/SF item mean was associated with a 45% increase in likelihood of postdischarge utilization (hospital readmission and emergency room department visits). Therefore, we defined convergence of team-patient SMMs (or similar patient and team scores) as those with an absolute difference score less than 1 point, whereas teams with low team-patient SMM convergence (or divergent patient and team scores) were defined as having an absolute difference score greater than 1 point.

Prediction Models

For the exploratory aim, we first examined the bivariate relationship between the outcome variables (discharge teams’ assessment of patient readiness, team convergence, and team-patient convergence) and the identified contextual variables. We also checked for potential collinearity among the explanatory variables. Then we used a linear stepwise regression procedure to identify factors associated with each continuous outcome variable. Due to the small sample size, we performed separate backward stepwise regression selection analyses for the three outcomes of interest. The candidate explanatory variables were evaluated using P < .20 for model entry. Final models were evaluated using leave-one-out cross validation. STATA (v.15.1, StataCorp; 2017) was used for analysis.

RESULTS

Sample

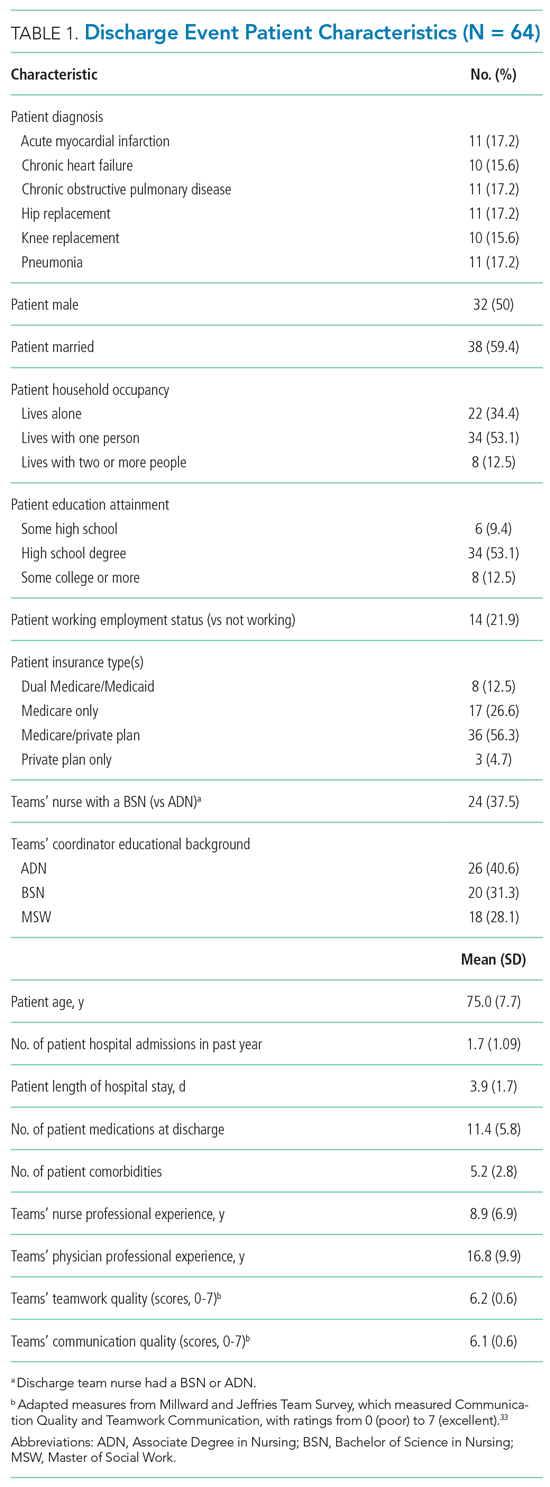

A total of 64 discharge events were included in this study. All discharge teams had a unique composition including 64 patients and varying combinations of 56 individual nurses (n = 27), physicians (n = 23), and coordinators (n = 6). Each event had three team members (ie, a nurse, a coordinator, and a physician) with no missing data. The majority of the 64 patient participants were White, retired, had a high school education, and lived in their own home with only one other person (Table 1).

Interprofessional Teams’ SMM of Readiness for Hospital Discharge

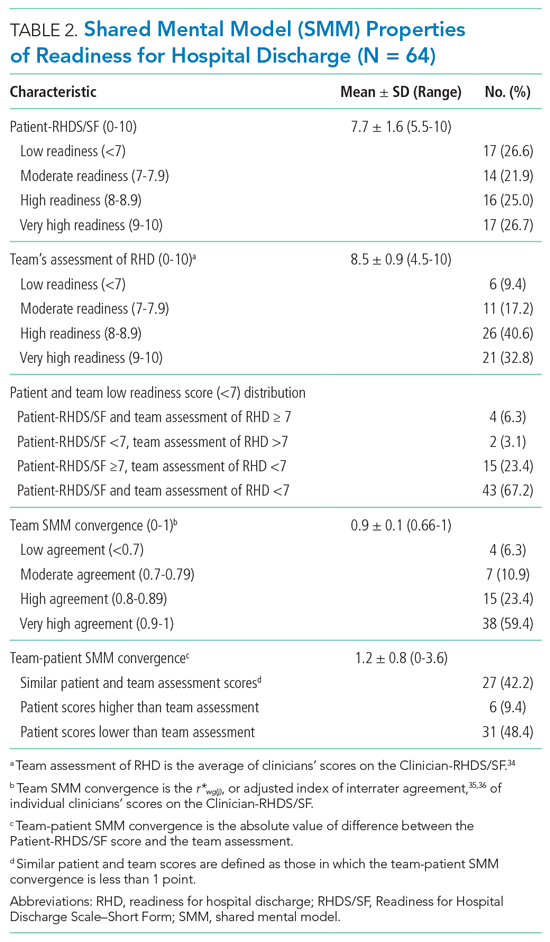

While the majority of teams perceived patients had high readiness for hospital discharge (mean, 8.5 out of 10; SD, 0.91), patients scores were nearly a full point lower (mean, 7.7; SD, 1.6; Table 2). The largest difference across categories was in the low-readiness category with 27% of patient scores falling into this category vs only 9.4% of discharge team mean scores. The mean SMM convergence of team perception of patients’ readiness for discharge was 0.90 (SD, 0.10); however, scores ranged from 0.66 (low agreement) to 1 (complete agreement). The average SMM team-patient convergence, or the discrepancy between the discharge team mean scores and the patient total scores across domains, was 1.16 (SD, 0.82). Of the 64 discharge events, 42.2% had similar team-patient perceptions of readiness for discharge, 9.4% had the patient reporting higher readiness for discharge than the team, and 48.4% had a team assessment rating of higher readiness for discharge than the patient’s self-assessment.

Prediction Models

In the exploratory analysis, we created individual linear regression models to predict the teams’ assessment, team convergence, and team-patient convergence for readiness of hospital discharge (Table 3; Appendix E). Factors associated with the teams’ assessment of discharge readiness included whether the patient was married and had less cognitive impairment, both of which were positively related to a higher-rated readiness among teams. An important system factor was higher quality of communication among team members, which was positively associated with teams’ assessment of patient discharge readiness. In contrast, only patient factors—married patients and those with a principal diagnosis of heart failure—were associated with more convergent team SMMs. Team-patient convergence was positively associated with two patient factors: marital status (married) and fewer comorbidities. However, team-patient convergence was also associated with two system factors: teams with a bachelor’s level–trained nurse (compared with a nurse with an associate degree ) and teams reporting a higher quality of teamwork on day of discharge.

DISCUSSION

Our study applied novel approaches to explore the interprofessional teams’ understanding of discharge readiness, a concept known to be an important predictor of patient outcomes after discharge, including readmission.20,28 We found that discharge teams frequently had poor quality SMMs of hospital discharge readiness. Despite having a discharge order and receiving home care instructions, one in four patients reported low readiness for hospital discharge. Additionally, discharge teams frequently overestimated patient’s readiness for hospital discharge. Misalignment on patient readiness for discharge occurred both within the discharge team (ie, low team convergence) and between patients and their care teams (ie, low team-patient convergence). The potential importance of this disagreement is substantiated by prior work suggesting that divergence in readiness ratings between nurses and patients are associated with postdischarge coping difficulties.28

Previous readiness for discharge has been measured from the perspective of the patient,20,21,27,28 nurse,20,25-28 and physician,37 yet rarely has the teams’ perspective been examined. We add to this literature by measuring the team’s perspective, as well as agreement between team and patient, on the individual patient’s readiness for discharge. Notably, we found that higher-quality communication is positively related to teams’ assessment of discharge readiness, with teams that reported higher quality teamwork having more convergent team-patient SMMs. Our results support many qualitative studies identifying communication and teamwork as major factors in teams’ effectiveness in discharge planning.1-7,9 However, given the small sample size in this study, additional research is needed to further understand these relationships, as well as link SMMs to patient outcomes such as hospital readmission.

In an attempt to improve discharge planning, hospitals are increasingly assessing readiness for discharge as a low-intensity, low-cost intervention.26,27 Yet, recent evidence suggests that readiness assessments alone have minimal impact on reducing hospital readmissions.26 To be successful, these assessments likely depend on quality interprofessional communication and ensuring the patient’s voice is incorporated into the discharge decision process.26 However, there have been few ways to effectively evaluate these types of team interventions.9 Measuring SMM properties holds promise for identifying specific team mechanisms that may influence the effectiveness and fidelity of interventions for team-based discharge planning. As our findings indicate, SMMs provide a theoretical and methodological basis for evaluating if readiness for discharge was team based (convergence among team members) and patient centered (convergence among team assessment and patient self-assessment). Researchers and improvement scientists can use the approach outlined to evaluate team-based patient-centered interventions for hospital discharge planning.9

This study provides a unique contribution to the growing work in the team science of SMMs.9,10 We rigorously evaluated SMMs of key stakeholders (patients and their interprofessional team) in “real-time” clinical practice using a patient-centered assessment linked with postdischarge outcomes.20,27,28 However, it is still unknown how much convergence is needed (and with whom) to safely discharge patients.13 Prior studies suggest highly convergent SMMs increase team performance when they are also accurate.10-13 Convergence alone should not be sought because this may reflect groupthink or clinical inertia.10,15 To improve discharge team performance over time,10‑13 it is important to assess not only patient’s readiness on the day of discharge but also how prepared the patient actually was for the recovery period following acute care. In the larger mixed-methods study, we found that teams’ with more convergent SMMs on teamwork quality were associated with patient’s reported quality of transition 30-days after discharge.9 Together, these findings further highlight the importance of aligning patient and interprofessional team members perspectives during the discharge planning, as well as providing clinicians with regular feedback about patient’s postdischarge experiences and outcomes.

To optimize team performance, the discharge planning process must be considered from an interprofessional team perspective as it functions in real-world practice settings. There are increasing pressures to discharge patients “quicker and sicker,” to simplify and standardize clinical process, and to provide patient-centered care.3,5-8 Without thoughtful interventions to facilitate communication during discharge planning, these pressures likely reinforce inaccurate assumptions regarding the work of fellow team members and force teams to think “fast” instead of “slow.”38-40 One approach to overcome such barriers is to focus on building a high-quality interprofessional SMM around discharge readiness. For example, the RHDS/SF questions could be integrated into the electronic medical records, displayed on dashboards, and discussed regularly during discharge rounds. In particular, to strengthen the team’s SMM and quality of teamwork, together the staff can ask three practical questions (Appendix F): (1) Do we think the patient is ready for discharge? (2) To what extent do we all agree the patient is ready for discharge? (3) Does our assessment of discharge readiness match the patient’s? During this high-risk transition point, asking these questions might allow the team to move from thinking fast to thinking slowly so they can more effectively identify heuristics they may be using inaccurately, prevent blind spots, and move toward high reliability.10,13,18,38-40

This study has limitations. First, events were recruited from patients with any of only six conditions at a single hospital. Other settings, patient condition types, or team compositions of other clinicians may differ in results. Second, in this study the SMM content was focused on readiness for hospital discharge among four key stakeholders. It is possible other SMM content needs to be shared among the interprofessional discharge team (eg, caregivers’ perspectives,2,6-8 resource availability,3-6 clinicians’ roles4,9) or additional members should be included (eg, physical therapists, nursing assistants, home health consultants, or primary care clinicians). Although this study focused on a patient-centered outcome (Patient-RHDS/SF), we did not examine other important outcomes such as hospital readmission. Additionally, due to the small sample size, these results have limited generalizability and should be interpreted with caution. Last, we limited data collection to the day of hospital discharge; future studies might consider assessing discharge readiness throughout hospitalization.

CONCLUSION

Readying patients for hospital discharge is a time-sensitivehigh-risk task requiring multiple healthcare professionals to concurrently assess patient needs, formulate an anticipatory care plan, provide education, and arrange for postdischarge needs.20,21 Despite this, few studies have analyzed teamwork aspects to understand how these transitions could be improved.9 By piloting SMM measurement and describing factors that affect SMMs, we provide a step toward identifying and evaluating strategies to assist interprofessional care teams in preparing patients for a safe, high-quality, patient-centered hospital discharge.

Presentations

This work was presented at the Midwest Nursing Research Society’s 2018 Annual Research Conference in Cleveland, Ohio, as well as at AcademyHealth’s 2019 Annual Research Meeting in Washington, District of Columbia.

- Greysen SR, Schiliro D, Horwitz LI, Curry L, Bradley E. “Out of sight, out of mind”: house staff perceptions of quality-limiting factors in discharge care at teaching hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):376-381.https://doi.org/10.1002/%20jhm.1928

- Fuji KT, Abbott AA, Norris JF. Exploring care transitions from patient, caregiver, and health-care provider perspectives. Clin Nurs Res. 2013;22(3):258-274. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054773812465084

- Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL, Coleman EA. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):314-323. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.228

- Waring J, Bishop S, Marshall F. A qualitative study of professional and career perceptions of the threats to safe hospital discharge for stroke and hip fracture patients in the English National Health Service. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:297. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1568-2

- Nosbusch JM, Weiss ME, Bobay KL. An integrated review of the literature on challenges confronting the acute care staff nurse in discharge planning. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(5-6):754-774. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03257.x

- Ashbrook L, Mourad M, Sehgal N. Communicating discharge instructions to patients: a survey of nurse, intern, and hospitalist practices. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(1):36-41. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1986

- Prusaczyk B, Kripalani S, Dhand A. Networks of hospital discharge planning teams and readmissions. J Interprof Care. 2019;33(1):85-92. https://doi.org/1 0.1080/13561820.2018.1515193

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Revisions to Requirements for Discharge Planning for Hospitals, Critical Access Hospitals, and Home Health Agencies, and Hospital and Critical Access Hospital Changes to Promote Innovation, Flexibility, and Improvement in Patient Care. Septemeber 30, 2019. Federal Register. Accessed May 24, 2021. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/09/30/2019-20732/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-revisions-to-requirements-for-discharge-planning-for-hospitals

- Manges K, Groves PS, Farag A, Peterson R, Harton J, Greysen SR. A mixed methods study examining teamwork shared mental models of interprofessional teams during hospital discharge. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29(6):499-508. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009716

- Mohammed S, Ferzandi L, Hamilton K. Metaphor no more: a 15-year review of the team mental model construct. J Manage. 2010;36(4):876-910. https:// doi.org/10.1177%2F0149206309356804

- Langan-Fox J, Code S, Langfield-Smith K. Team mental models: techniques, methods, and analytic approaches. Hum Factors. 2000;42(2);242-271. https:// doi.org/10.1518/001872000779656534

- Lim BC, Klein KJ. Team mental models and team performance: a field study of the effects of team mental model similarity and accuracy. J Organ Behav. 2006;27(4):403-418. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.387

- Burtscher MJ, Manser T. Team mental models and their potential to improve teamwork and safety: a review and implications for future research in healthcare. Safety Sci. 2012;50(5):1344-1354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ssci.2011.12.033

- Calder LA, Mastoras G, Rahimpour M, et al. Team communication patterns in emergency resuscitation: a mixed methods qualitative analysis. Int J Emerg Med. 2017:10(1):24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-017-0149-4

- Westli HK, Johnsen BH, Eid J, Rasten I, Brattebø G. Teamwork skills, shared mental models, and performance in simulated trauma teams: an independent group design. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2010;18:47. https:// doi.org/10.1186/1757-7241-18-47

- Johnsen BH, Westli HK, Espevik R, Wisborg R, Brattebø G. High-performing trauma teams: frequency of behavioral markers of a shared mental model displayed by team leaders and quality of medical performance. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2017;25(1):109. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049- 017-0452-3

- Custer JW, White E, Fackler JC, et al. A qualitative study of expert and team cognition on complex patients in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13(3):278-284. https://doi.org/10.1097/ pcc.0b013e31822f1766

- Cutrer WB, Thammasitboon S. Team mental model creation as a mechanism to decrease errors in the intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13(3):354-356. https://doi.org/10.1097/pcc.0b013e3182388994

- Gjeraa K, Dieckmann P, Spanager L, et al. Exploring shared mental models of surgical teams in video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery lobectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;107(3):954-961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.08.010

- Weiss ME, Costa LL, Yakusheva O, Bobay KL. Validation of patient and nurse short forms of the Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scale and their relationship to return to the hospital. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(1):304-317. https:// doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12092

- Galvin EC, Wills T, Coffey A. Readiness for hospital discharge: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73(11):2547-2557. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13324

- Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP). Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Updated August 11, 2020. Accessed January 6, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality-initiatives-patient-assessment-instruments/value-based-programs/hrrp/hospital-readmission-reduction-program.html

- Epstein RM, Fiscella K, Lesser CS, Stange KC. Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-centered health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(8):1489- 1495. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0888

- Graumlich JF, Novotny NL, Aldag JC. Brief scale measuring patient preparedness for hospital discharge to home: psychometric properties. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(6):446-454. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.316

- Bobay KL, Weiss ME, Oswald D, Yakusheva O. Validation of the Registered Nurse Assessment of Readiness for Hospital Discharge scale. Nurs Res. 2018;67(4):305-313. https://doi.org/10.1097/nnr.0000000000000293

- Weiss ME, Yakusheva O, Bobay K, et al. Effect of implementing discharge readiness assessment in adult medical-surgical units on 30-Day return to hospital: the READI randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e187387. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7387

- Weiss ME, Yakusheva O, Bobay K. Nurse and patient perceptions of discharge readiness in relation to postdischarge utilization. Med Care. 2010;48(5):482-486. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0b013e3181d5feae

- Wallace AS, Perkhounkova Y, Bohr NL, Chung SJ. Readiness for hospital discharge, health literacy, and social living status. Clin Nurs Res. 2016;25(5):494- 511. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054773815624380

- Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975;23(10):433- 441. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1975.tb00927.x

- Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, et al. Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA. 2011;306(15):1688-1698. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1515

- Aiken LH, Cimiotti JP, Sloane DM, Smith HL, Flynn L, Neff DF. Effects of nurse staffing and nurse education on patient deaths in hospitals with different nurse work environments. J Nurs Adm. 2012;42(10 Suppl):S10-S16. https:// doi.org/10.1097/01.nna.0000420390.87789.67

- Goodwin JS, Salameh H, Zhou J, Singh S, Kuo YF, Nattinger AB. Association of hospitalist years of experience with mortality in the hospitalized Medicare population. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(2):196-203. https://doi. org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7049

- Millward LJ, Jeffries N. The team survey: a tool for health care team development. J Adv Nurs. 2001;35(2):276-287. https://doi.org/10.1046/j. 1365-2648.2001.01844.x

- Klein KJ, Kozlowski SW. From micro to meso: critical steps in conceptualizing and conducting multilevel research. Organ Res Methods. 2000;3(3):211-236. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810033001

- Lindell MK, Brandt CJ, Whitney DJ. A revised index of interrater agreement for multi-item ratings of a single target. Appl Psychol Meas. 1999;23(2):127- 135. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F01466219922031257

- O’Neill TA. An overview of interrater agreement on Likert scales for researchers and practitioners. Front Psychol. 2017;8:777. https://doi.org/10.3389/ fpsyg.2017.00777

- Sullivan B, Ming D, Boggan JC, et al. An evaluation of physician predictions of discharge on a general medicine service. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(12):808- 810. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2439

- Kahneman D. Thinking, fast and slow. Doubleday; 2011.

- Croskerry P, Singhal G, Mamede S. Cognitive debiasing 1: origins of bias and theory of debiasing. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(Suppl 2):ii58-ii64. https://doi. org/10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001712

- Burke RE, Leonard C, Lee M, et al. Cognitive biases influence decision-making regarding postacute care in a skilled nursing facility. J Hosp Med. 2020:15(1)22-27. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3273

Preparing patients for hospital discharge requires multiple tasks that cross professional boundaries. Clinician’s roles may be ambiguous, and responsibility for a safe high-quality discharge is often diffused among the team rather than being defined as the core responsibility of a single member.1-8 Without a shared understanding of patient resources and tasks involved in anticipatory planning, lapses in discharge preparation can occur, which places patients at increased risk for harm after hospitalization.3-7 As a result, organizations like the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) have called for team-based patient-centered discharge planning.8 Yet to develop more effective team-based discharge planning interventions, a more nuanced understanding of how healthcare teams work together is needed.2,3,9

Shared mental models (SMMs) provide a useful theoretical framework and measurement approach for examining how interprofessional teams coordinate complex tasks like hospital discharge.10-13 SMMs represent the team members’ collective understanding and organized knowledge of key elements needed for teams to perform effectively.9-11 Validated questionnaires can be used to measure two key properties of SMMs: the degree to which team members have a similar understanding of the situation at hand (team SMM convergence) and to what extent this understanding is aligned with the patient (team-patient SMM convergence).10,11 Researchers have found that teams with higher-quality SMMs have a better understanding of what is happening and why, have clearer expectations of their roles and tasks, and can better predict what might happen next.10,12 As a result, these teams more effectively coordinate actions and adapt to task demands even in cases of high complexity, uncertainty, and stress.10-13 Prior studies examining healthcare teams in emergency departments,14-16 critical care units,17,18 and operating rooms19 suggest high-quality SMMs are needed to safely care for patients.13 Yet there has been limited evaluation of SMMs in general internal medicine, much less during hospital discharge.9,13 The purpose of this study was to examine SMMs for a critical task of the inpatient team: developing a shared understanding of the patient’s readiness for hospital discharge.20,21

METHODS

Design

We used a cross-sectional survey design at a single Midwestern community hospital to determine inpatient care teams’ SMMs of patient hospital discharge readiness. This study is part of a larger mixed-methods evaluation of interprofessional hospital discharge teamwork in older adult patients at risk for a poor transition to home.9 Data were collected using questionnaires from patients and their team (nurse, coordinator, and physician) within 4 hours of the patient leaving the hospital. First, we measured the teams’ assessment, team convergence, and team-patient convergence on patient readiness for discharge from the hospital. Then, after identifying relevant potential predictors from the literature, we developed regression models to predict the teams’ assessment, team convergence, and team-patient convergence of discharge readiness based on these variables. Our local institutional review board approved this study.

Sample and Participants

We used a convenience sampling approach to identify eligible discharge events consisting of the patient and care team.9 We focused on patients at high-risk for poor hospital-to-home transitions.3,22 Eligible events included older patients (≥65 years) who were discharged home without home health or hospice services and admitted with a primary diagnosis of heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, hip replacement, knee replacement, pneumonia, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Patient exclusion criteria included inability to complete study forms because of mental incapacity or a language barrier. Discharge team member inclusion criteria included the bedside nurse, attending physician, and coordinator (a unit-dedicated discharge nurse or social worker) caring for the patient participant at the time of hospital discharge. Each discharge team was unique: The same three individuals could not be included as a “team” for more than one discharge event, although individual members could be included as a part of other teams with a different set of individuals. Appendix A provides an enrollment flowchart.

Conceptual Framework

We applied the SMM conceptual framework to the context of hospital discharge. As shown in the Figure, SMMs are examined at the team level and contain the critical knowledge held by the team to be effective.15,16 From a patient-centered perspective, patients are considered the expert on how ready they feel to be discharged home.20,23,24 In this case, the SMM content is the discharge team members’ shared assessment of how ready the patient is for hospital discharge (Figure, B).10 Convergence is the degree of agreement among individual mental models.10-13 In this study we examined two types of convergence: (1) team convergence, or the team members degree of agreement on the patient’s readiness for discharge (Figure, C), and (2) team-patient convergence, or the degree to which the team’s SMM aligns with the patient’s mental model (Figure, D).10-13

Measures and Variables

Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scales/Short Form

We used parallel clinician and patient versions of the Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scale/Short Form (RHDS/SF)25-28 to determine the teams’ assessment of discharge readiness, team SMM convergence, and team-patient SMM convergence.

The RHDS/SF scales are 8-item validated instruments that use a Likert scale (0 for not ready to 10 for totally ready) to assess the individual clinician’s or patient’s perceptions of how ready the patient is to be discharged.20,25,27 The RHDS/SF instruments include four dimensions conceptualized as crucial to patient readiness for discharge and important to anticipatory planning: (1) Personal Status, physical-emotional state of the patient before discharge; (2) Knowledge, perceived adequacy of information needed to respond to common posthospitalization concerns/problems; (3) Coping Ability, perceived ability to self-manage health care needs; and (4) Expected Support, emotional-physical assistance available (Appendix B).20,25,27 The RHDS/SF instruments’ results are calculated as a mean of item scores, with higher individual scores indicating the rater assessed the patient as being more ready for hospital discharge.20 The RHDS/SF scales have undergone rigorous psychometric testing and are linked to patient outcomes (eg, readmissions, emergency room visits, patient coping difficulties after discharge, and patient-rated quality of preparation for posthospital care).20,25-28 For example, predictive validity assessments for adult medical-surgical patients found lower Nurse-RHDS/SF scores are associated with a six- to ninefold increase in 30-day readmission risk.20

Contextual Variables

We reviewed the literature to identify potential patient and system factors associated with adverse transitional care outcomes1-8 and/or higher quality SMMs in other settings.10-19 For example, patient characteristics included age, principal diagnosis, length of stay, number of comorbidities, and cognition impairment (using the Short Portable Mini Mental Status Questionnaire29).2,22,30 Examples of system factor include teamwork and communication quality1-6 on day of discharge, as well as educational background and experience of clinicians on the team.31-33 We adapted a validated survey using 7-point Likert scale questions to determine teamwork quality and communication quality during individual patent discharges.33Appendix C provides descriptions of all variables.

Data Collection

Patient recruitment occurred from February to October 2017 in a single community hospital in Iowa.9 We identified potentially eligible events in collaboration with the unit charge nurses. Patients were screened 24 to 48 hours prior to anticipated day of discharge; those interested/eligible underwent informed consent procedures.9 We collected data from the patient and their corresponding bedside nurse, coordinator, and attending physician on the day of discharge. After the discharge order was placed and care instructions were provided, the patient completed a demographic survey, Short Portable Mini Mental Status Questionnaire, and the Patient-RHDS/SF. Individual team members completed a survey with the demographic information, their respective versions of RHDS/SF, and day-of-discharge teamwork-related questions. On average, the survey took clinicians less than 5 minutes to complete. We performed a chart review to determine additional patient characteristics such as principal diagnosis, length of stay, and number of comorbidities.

Data Analysis

Team Assessment of Patient Discharge Readiness

The teams’ shared assessment (SMM content) was determined by averaging the members’ individual scores on the Clinician-RHDS/SF.34 Discharge events with higher team assessments indicated the team perceived the patient as being readier for hospital discharge. Guided by prior research, we examined the RHDS/SF scores as a continuous variable and as a four-level categorical variable of readiness: low (<7), moderate (7-7.9), high (8-8.9), and very high (9-10).20

Team SMM Convergence

To determine the teams’ convergence on patient discharge readiness, we calculated an adjusted interrater agreement index (r*wg(j))35,36 for each team using the individual clinicians’ scores on the RHDS/SF. These convergence values were categorized into four agreement levels: low agreement (<0.7), moderate agreement (0.7-0.79), high agreement (0.8-0.89), and very high agreement (0.9-1). See Appendix D for the r*wg(j) equation.35,36

Team-Patient SMM Convergence

To determine the team-patient SMM convergence, we subtracted the team’s assessment of patient discharge readiness from the Patient-RHDS/SF score. We used a one-unit change on the RHDS/SF (1 point on the 0-10 scale) as a meaningful difference between the patient’s self-assessment and teams’ assessment on readiness for hospital discharge. This definition for divergence aligns with prior RHDS psychometric testing studies20,27 and research examining convergence between patient and nurse assessments.28 For example, Weiss and colleagues27 found a 1-point decrease in the RN-RHDS/SF item mean was associated with a 45% increase in likelihood of postdischarge utilization (hospital readmission and emergency room department visits). Therefore, we defined convergence of team-patient SMMs (or similar patient and team scores) as those with an absolute difference score less than 1 point, whereas teams with low team-patient SMM convergence (or divergent patient and team scores) were defined as having an absolute difference score greater than 1 point.

Prediction Models

For the exploratory aim, we first examined the bivariate relationship between the outcome variables (discharge teams’ assessment of patient readiness, team convergence, and team-patient convergence) and the identified contextual variables. We also checked for potential collinearity among the explanatory variables. Then we used a linear stepwise regression procedure to identify factors associated with each continuous outcome variable. Due to the small sample size, we performed separate backward stepwise regression selection analyses for the three outcomes of interest. The candidate explanatory variables were evaluated using P < .20 for model entry. Final models were evaluated using leave-one-out cross validation. STATA (v.15.1, StataCorp; 2017) was used for analysis.

RESULTS

Sample

A total of 64 discharge events were included in this study. All discharge teams had a unique composition including 64 patients and varying combinations of 56 individual nurses (n = 27), physicians (n = 23), and coordinators (n = 6). Each event had three team members (ie, a nurse, a coordinator, and a physician) with no missing data. The majority of the 64 patient participants were White, retired, had a high school education, and lived in their own home with only one other person (Table 1).

Interprofessional Teams’ SMM of Readiness for Hospital Discharge

While the majority of teams perceived patients had high readiness for hospital discharge (mean, 8.5 out of 10; SD, 0.91), patients scores were nearly a full point lower (mean, 7.7; SD, 1.6; Table 2). The largest difference across categories was in the low-readiness category with 27% of patient scores falling into this category vs only 9.4% of discharge team mean scores. The mean SMM convergence of team perception of patients’ readiness for discharge was 0.90 (SD, 0.10); however, scores ranged from 0.66 (low agreement) to 1 (complete agreement). The average SMM team-patient convergence, or the discrepancy between the discharge team mean scores and the patient total scores across domains, was 1.16 (SD, 0.82). Of the 64 discharge events, 42.2% had similar team-patient perceptions of readiness for discharge, 9.4% had the patient reporting higher readiness for discharge than the team, and 48.4% had a team assessment rating of higher readiness for discharge than the patient’s self-assessment.

Prediction Models

In the exploratory analysis, we created individual linear regression models to predict the teams’ assessment, team convergence, and team-patient convergence for readiness of hospital discharge (Table 3; Appendix E). Factors associated with the teams’ assessment of discharge readiness included whether the patient was married and had less cognitive impairment, both of which were positively related to a higher-rated readiness among teams. An important system factor was higher quality of communication among team members, which was positively associated with teams’ assessment of patient discharge readiness. In contrast, only patient factors—married patients and those with a principal diagnosis of heart failure—were associated with more convergent team SMMs. Team-patient convergence was positively associated with two patient factors: marital status (married) and fewer comorbidities. However, team-patient convergence was also associated with two system factors: teams with a bachelor’s level–trained nurse (compared with a nurse with an associate degree ) and teams reporting a higher quality of teamwork on day of discharge.

DISCUSSION

Our study applied novel approaches to explore the interprofessional teams’ understanding of discharge readiness, a concept known to be an important predictor of patient outcomes after discharge, including readmission.20,28 We found that discharge teams frequently had poor quality SMMs of hospital discharge readiness. Despite having a discharge order and receiving home care instructions, one in four patients reported low readiness for hospital discharge. Additionally, discharge teams frequently overestimated patient’s readiness for hospital discharge. Misalignment on patient readiness for discharge occurred both within the discharge team (ie, low team convergence) and between patients and their care teams (ie, low team-patient convergence). The potential importance of this disagreement is substantiated by prior work suggesting that divergence in readiness ratings between nurses and patients are associated with postdischarge coping difficulties.28

Previous readiness for discharge has been measured from the perspective of the patient,20,21,27,28 nurse,20,25-28 and physician,37 yet rarely has the teams’ perspective been examined. We add to this literature by measuring the team’s perspective, as well as agreement between team and patient, on the individual patient’s readiness for discharge. Notably, we found that higher-quality communication is positively related to teams’ assessment of discharge readiness, with teams that reported higher quality teamwork having more convergent team-patient SMMs. Our results support many qualitative studies identifying communication and teamwork as major factors in teams’ effectiveness in discharge planning.1-7,9 However, given the small sample size in this study, additional research is needed to further understand these relationships, as well as link SMMs to patient outcomes such as hospital readmission.

In an attempt to improve discharge planning, hospitals are increasingly assessing readiness for discharge as a low-intensity, low-cost intervention.26,27 Yet, recent evidence suggests that readiness assessments alone have minimal impact on reducing hospital readmissions.26 To be successful, these assessments likely depend on quality interprofessional communication and ensuring the patient’s voice is incorporated into the discharge decision process.26 However, there have been few ways to effectively evaluate these types of team interventions.9 Measuring SMM properties holds promise for identifying specific team mechanisms that may influence the effectiveness and fidelity of interventions for team-based discharge planning. As our findings indicate, SMMs provide a theoretical and methodological basis for evaluating if readiness for discharge was team based (convergence among team members) and patient centered (convergence among team assessment and patient self-assessment). Researchers and improvement scientists can use the approach outlined to evaluate team-based patient-centered interventions for hospital discharge planning.9

This study provides a unique contribution to the growing work in the team science of SMMs.9,10 We rigorously evaluated SMMs of key stakeholders (patients and their interprofessional team) in “real-time” clinical practice using a patient-centered assessment linked with postdischarge outcomes.20,27,28 However, it is still unknown how much convergence is needed (and with whom) to safely discharge patients.13 Prior studies suggest highly convergent SMMs increase team performance when they are also accurate.10-13 Convergence alone should not be sought because this may reflect groupthink or clinical inertia.10,15 To improve discharge team performance over time,10‑13 it is important to assess not only patient’s readiness on the day of discharge but also how prepared the patient actually was for the recovery period following acute care. In the larger mixed-methods study, we found that teams’ with more convergent SMMs on teamwork quality were associated with patient’s reported quality of transition 30-days after discharge.9 Together, these findings further highlight the importance of aligning patient and interprofessional team members perspectives during the discharge planning, as well as providing clinicians with regular feedback about patient’s postdischarge experiences and outcomes.

To optimize team performance, the discharge planning process must be considered from an interprofessional team perspective as it functions in real-world practice settings. There are increasing pressures to discharge patients “quicker and sicker,” to simplify and standardize clinical process, and to provide patient-centered care.3,5-8 Without thoughtful interventions to facilitate communication during discharge planning, these pressures likely reinforce inaccurate assumptions regarding the work of fellow team members and force teams to think “fast” instead of “slow.”38-40 One approach to overcome such barriers is to focus on building a high-quality interprofessional SMM around discharge readiness. For example, the RHDS/SF questions could be integrated into the electronic medical records, displayed on dashboards, and discussed regularly during discharge rounds. In particular, to strengthen the team’s SMM and quality of teamwork, together the staff can ask three practical questions (Appendix F): (1) Do we think the patient is ready for discharge? (2) To what extent do we all agree the patient is ready for discharge? (3) Does our assessment of discharge readiness match the patient’s? During this high-risk transition point, asking these questions might allow the team to move from thinking fast to thinking slowly so they can more effectively identify heuristics they may be using inaccurately, prevent blind spots, and move toward high reliability.10,13,18,38-40

This study has limitations. First, events were recruited from patients with any of only six conditions at a single hospital. Other settings, patient condition types, or team compositions of other clinicians may differ in results. Second, in this study the SMM content was focused on readiness for hospital discharge among four key stakeholders. It is possible other SMM content needs to be shared among the interprofessional discharge team (eg, caregivers’ perspectives,2,6-8 resource availability,3-6 clinicians’ roles4,9) or additional members should be included (eg, physical therapists, nursing assistants, home health consultants, or primary care clinicians). Although this study focused on a patient-centered outcome (Patient-RHDS/SF), we did not examine other important outcomes such as hospital readmission. Additionally, due to the small sample size, these results have limited generalizability and should be interpreted with caution. Last, we limited data collection to the day of hospital discharge; future studies might consider assessing discharge readiness throughout hospitalization.

CONCLUSION

Readying patients for hospital discharge is a time-sensitivehigh-risk task requiring multiple healthcare professionals to concurrently assess patient needs, formulate an anticipatory care plan, provide education, and arrange for postdischarge needs.20,21 Despite this, few studies have analyzed teamwork aspects to understand how these transitions could be improved.9 By piloting SMM measurement and describing factors that affect SMMs, we provide a step toward identifying and evaluating strategies to assist interprofessional care teams in preparing patients for a safe, high-quality, patient-centered hospital discharge.

Presentations

This work was presented at the Midwest Nursing Research Society’s 2018 Annual Research Conference in Cleveland, Ohio, as well as at AcademyHealth’s 2019 Annual Research Meeting in Washington, District of Columbia.

Preparing patients for hospital discharge requires multiple tasks that cross professional boundaries. Clinician’s roles may be ambiguous, and responsibility for a safe high-quality discharge is often diffused among the team rather than being defined as the core responsibility of a single member.1-8 Without a shared understanding of patient resources and tasks involved in anticipatory planning, lapses in discharge preparation can occur, which places patients at increased risk for harm after hospitalization.3-7 As a result, organizations like the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) have called for team-based patient-centered discharge planning.8 Yet to develop more effective team-based discharge planning interventions, a more nuanced understanding of how healthcare teams work together is needed.2,3,9

Shared mental models (SMMs) provide a useful theoretical framework and measurement approach for examining how interprofessional teams coordinate complex tasks like hospital discharge.10-13 SMMs represent the team members’ collective understanding and organized knowledge of key elements needed for teams to perform effectively.9-11 Validated questionnaires can be used to measure two key properties of SMMs: the degree to which team members have a similar understanding of the situation at hand (team SMM convergence) and to what extent this understanding is aligned with the patient (team-patient SMM convergence).10,11 Researchers have found that teams with higher-quality SMMs have a better understanding of what is happening and why, have clearer expectations of their roles and tasks, and can better predict what might happen next.10,12 As a result, these teams more effectively coordinate actions and adapt to task demands even in cases of high complexity, uncertainty, and stress.10-13 Prior studies examining healthcare teams in emergency departments,14-16 critical care units,17,18 and operating rooms19 suggest high-quality SMMs are needed to safely care for patients.13 Yet there has been limited evaluation of SMMs in general internal medicine, much less during hospital discharge.9,13 The purpose of this study was to examine SMMs for a critical task of the inpatient team: developing a shared understanding of the patient’s readiness for hospital discharge.20,21

METHODS

Design

We used a cross-sectional survey design at a single Midwestern community hospital to determine inpatient care teams’ SMMs of patient hospital discharge readiness. This study is part of a larger mixed-methods evaluation of interprofessional hospital discharge teamwork in older adult patients at risk for a poor transition to home.9 Data were collected using questionnaires from patients and their team (nurse, coordinator, and physician) within 4 hours of the patient leaving the hospital. First, we measured the teams’ assessment, team convergence, and team-patient convergence on patient readiness for discharge from the hospital. Then, after identifying relevant potential predictors from the literature, we developed regression models to predict the teams’ assessment, team convergence, and team-patient convergence of discharge readiness based on these variables. Our local institutional review board approved this study.

Sample and Participants

We used a convenience sampling approach to identify eligible discharge events consisting of the patient and care team.9 We focused on patients at high-risk for poor hospital-to-home transitions.3,22 Eligible events included older patients (≥65 years) who were discharged home without home health or hospice services and admitted with a primary diagnosis of heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, hip replacement, knee replacement, pneumonia, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Patient exclusion criteria included inability to complete study forms because of mental incapacity or a language barrier. Discharge team member inclusion criteria included the bedside nurse, attending physician, and coordinator (a unit-dedicated discharge nurse or social worker) caring for the patient participant at the time of hospital discharge. Each discharge team was unique: The same three individuals could not be included as a “team” for more than one discharge event, although individual members could be included as a part of other teams with a different set of individuals. Appendix A provides an enrollment flowchart.

Conceptual Framework

We applied the SMM conceptual framework to the context of hospital discharge. As shown in the Figure, SMMs are examined at the team level and contain the critical knowledge held by the team to be effective.15,16 From a patient-centered perspective, patients are considered the expert on how ready they feel to be discharged home.20,23,24 In this case, the SMM content is the discharge team members’ shared assessment of how ready the patient is for hospital discharge (Figure, B).10 Convergence is the degree of agreement among individual mental models.10-13 In this study we examined two types of convergence: (1) team convergence, or the team members degree of agreement on the patient’s readiness for discharge (Figure, C), and (2) team-patient convergence, or the degree to which the team’s SMM aligns with the patient’s mental model (Figure, D).10-13

Measures and Variables

Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scales/Short Form

We used parallel clinician and patient versions of the Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scale/Short Form (RHDS/SF)25-28 to determine the teams’ assessment of discharge readiness, team SMM convergence, and team-patient SMM convergence.

The RHDS/SF scales are 8-item validated instruments that use a Likert scale (0 for not ready to 10 for totally ready) to assess the individual clinician’s or patient’s perceptions of how ready the patient is to be discharged.20,25,27 The RHDS/SF instruments include four dimensions conceptualized as crucial to patient readiness for discharge and important to anticipatory planning: (1) Personal Status, physical-emotional state of the patient before discharge; (2) Knowledge, perceived adequacy of information needed to respond to common posthospitalization concerns/problems; (3) Coping Ability, perceived ability to self-manage health care needs; and (4) Expected Support, emotional-physical assistance available (Appendix B).20,25,27 The RHDS/SF instruments’ results are calculated as a mean of item scores, with higher individual scores indicating the rater assessed the patient as being more ready for hospital discharge.20 The RHDS/SF scales have undergone rigorous psychometric testing and are linked to patient outcomes (eg, readmissions, emergency room visits, patient coping difficulties after discharge, and patient-rated quality of preparation for posthospital care).20,25-28 For example, predictive validity assessments for adult medical-surgical patients found lower Nurse-RHDS/SF scores are associated with a six- to ninefold increase in 30-day readmission risk.20

Contextual Variables

We reviewed the literature to identify potential patient and system factors associated with adverse transitional care outcomes1-8 and/or higher quality SMMs in other settings.10-19 For example, patient characteristics included age, principal diagnosis, length of stay, number of comorbidities, and cognition impairment (using the Short Portable Mini Mental Status Questionnaire29).2,22,30 Examples of system factor include teamwork and communication quality1-6 on day of discharge, as well as educational background and experience of clinicians on the team.31-33 We adapted a validated survey using 7-point Likert scale questions to determine teamwork quality and communication quality during individual patent discharges.33Appendix C provides descriptions of all variables.

Data Collection

Patient recruitment occurred from February to October 2017 in a single community hospital in Iowa.9 We identified potentially eligible events in collaboration with the unit charge nurses. Patients were screened 24 to 48 hours prior to anticipated day of discharge; those interested/eligible underwent informed consent procedures.9 We collected data from the patient and their corresponding bedside nurse, coordinator, and attending physician on the day of discharge. After the discharge order was placed and care instructions were provided, the patient completed a demographic survey, Short Portable Mini Mental Status Questionnaire, and the Patient-RHDS/SF. Individual team members completed a survey with the demographic information, their respective versions of RHDS/SF, and day-of-discharge teamwork-related questions. On average, the survey took clinicians less than 5 minutes to complete. We performed a chart review to determine additional patient characteristics such as principal diagnosis, length of stay, and number of comorbidities.

Data Analysis

Team Assessment of Patient Discharge Readiness

The teams’ shared assessment (SMM content) was determined by averaging the members’ individual scores on the Clinician-RHDS/SF.34 Discharge events with higher team assessments indicated the team perceived the patient as being readier for hospital discharge. Guided by prior research, we examined the RHDS/SF scores as a continuous variable and as a four-level categorical variable of readiness: low (<7), moderate (7-7.9), high (8-8.9), and very high (9-10).20

Team SMM Convergence

To determine the teams’ convergence on patient discharge readiness, we calculated an adjusted interrater agreement index (r*wg(j))35,36 for each team using the individual clinicians’ scores on the RHDS/SF. These convergence values were categorized into four agreement levels: low agreement (<0.7), moderate agreement (0.7-0.79), high agreement (0.8-0.89), and very high agreement (0.9-1). See Appendix D for the r*wg(j) equation.35,36

Team-Patient SMM Convergence

To determine the team-patient SMM convergence, we subtracted the team’s assessment of patient discharge readiness from the Patient-RHDS/SF score. We used a one-unit change on the RHDS/SF (1 point on the 0-10 scale) as a meaningful difference between the patient’s self-assessment and teams’ assessment on readiness for hospital discharge. This definition for divergence aligns with prior RHDS psychometric testing studies20,27 and research examining convergence between patient and nurse assessments.28 For example, Weiss and colleagues27 found a 1-point decrease in the RN-RHDS/SF item mean was associated with a 45% increase in likelihood of postdischarge utilization (hospital readmission and emergency room department visits). Therefore, we defined convergence of team-patient SMMs (or similar patient and team scores) as those with an absolute difference score less than 1 point, whereas teams with low team-patient SMM convergence (or divergent patient and team scores) were defined as having an absolute difference score greater than 1 point.

Prediction Models

For the exploratory aim, we first examined the bivariate relationship between the outcome variables (discharge teams’ assessment of patient readiness, team convergence, and team-patient convergence) and the identified contextual variables. We also checked for potential collinearity among the explanatory variables. Then we used a linear stepwise regression procedure to identify factors associated with each continuous outcome variable. Due to the small sample size, we performed separate backward stepwise regression selection analyses for the three outcomes of interest. The candidate explanatory variables were evaluated using P < .20 for model entry. Final models were evaluated using leave-one-out cross validation. STATA (v.15.1, StataCorp; 2017) was used for analysis.

RESULTS

Sample

A total of 64 discharge events were included in this study. All discharge teams had a unique composition including 64 patients and varying combinations of 56 individual nurses (n = 27), physicians (n = 23), and coordinators (n = 6). Each event had three team members (ie, a nurse, a coordinator, and a physician) with no missing data. The majority of the 64 patient participants were White, retired, had a high school education, and lived in their own home with only one other person (Table 1).

Interprofessional Teams’ SMM of Readiness for Hospital Discharge

While the majority of teams perceived patients had high readiness for hospital discharge (mean, 8.5 out of 10; SD, 0.91), patients scores were nearly a full point lower (mean, 7.7; SD, 1.6; Table 2). The largest difference across categories was in the low-readiness category with 27% of patient scores falling into this category vs only 9.4% of discharge team mean scores. The mean SMM convergence of team perception of patients’ readiness for discharge was 0.90 (SD, 0.10); however, scores ranged from 0.66 (low agreement) to 1 (complete agreement). The average SMM team-patient convergence, or the discrepancy between the discharge team mean scores and the patient total scores across domains, was 1.16 (SD, 0.82). Of the 64 discharge events, 42.2% had similar team-patient perceptions of readiness for discharge, 9.4% had the patient reporting higher readiness for discharge than the team, and 48.4% had a team assessment rating of higher readiness for discharge than the patient’s self-assessment.

Prediction Models

In the exploratory analysis, we created individual linear regression models to predict the teams’ assessment, team convergence, and team-patient convergence for readiness of hospital discharge (Table 3; Appendix E). Factors associated with the teams’ assessment of discharge readiness included whether the patient was married and had less cognitive impairment, both of which were positively related to a higher-rated readiness among teams. An important system factor was higher quality of communication among team members, which was positively associated with teams’ assessment of patient discharge readiness. In contrast, only patient factors—married patients and those with a principal diagnosis of heart failure—were associated with more convergent team SMMs. Team-patient convergence was positively associated with two patient factors: marital status (married) and fewer comorbidities. However, team-patient convergence was also associated with two system factors: teams with a bachelor’s level–trained nurse (compared with a nurse with an associate degree ) and teams reporting a higher quality of teamwork on day of discharge.

DISCUSSION

Our study applied novel approaches to explore the interprofessional teams’ understanding of discharge readiness, a concept known to be an important predictor of patient outcomes after discharge, including readmission.20,28 We found that discharge teams frequently had poor quality SMMs of hospital discharge readiness. Despite having a discharge order and receiving home care instructions, one in four patients reported low readiness for hospital discharge. Additionally, discharge teams frequently overestimated patient’s readiness for hospital discharge. Misalignment on patient readiness for discharge occurred both within the discharge team (ie, low team convergence) and between patients and their care teams (ie, low team-patient convergence). The potential importance of this disagreement is substantiated by prior work suggesting that divergence in readiness ratings between nurses and patients are associated with postdischarge coping difficulties.28

Previous readiness for discharge has been measured from the perspective of the patient,20,21,27,28 nurse,20,25-28 and physician,37 yet rarely has the teams’ perspective been examined. We add to this literature by measuring the team’s perspective, as well as agreement between team and patient, on the individual patient’s readiness for discharge. Notably, we found that higher-quality communication is positively related to teams’ assessment of discharge readiness, with teams that reported higher quality teamwork having more convergent team-patient SMMs. Our results support many qualitative studies identifying communication and teamwork as major factors in teams’ effectiveness in discharge planning.1-7,9 However, given the small sample size in this study, additional research is needed to further understand these relationships, as well as link SMMs to patient outcomes such as hospital readmission.

In an attempt to improve discharge planning, hospitals are increasingly assessing readiness for discharge as a low-intensity, low-cost intervention.26,27 Yet, recent evidence suggests that readiness assessments alone have minimal impact on reducing hospital readmissions.26 To be successful, these assessments likely depend on quality interprofessional communication and ensuring the patient’s voice is incorporated into the discharge decision process.26 However, there have been few ways to effectively evaluate these types of team interventions.9 Measuring SMM properties holds promise for identifying specific team mechanisms that may influence the effectiveness and fidelity of interventions for team-based discharge planning. As our findings indicate, SMMs provide a theoretical and methodological basis for evaluating if readiness for discharge was team based (convergence among team members) and patient centered (convergence among team assessment and patient self-assessment). Researchers and improvement scientists can use the approach outlined to evaluate team-based patient-centered interventions for hospital discharge planning.9

This study provides a unique contribution to the growing work in the team science of SMMs.9,10 We rigorously evaluated SMMs of key stakeholders (patients and their interprofessional team) in “real-time” clinical practice using a patient-centered assessment linked with postdischarge outcomes.20,27,28 However, it is still unknown how much convergence is needed (and with whom) to safely discharge patients.13 Prior studies suggest highly convergent SMMs increase team performance when they are also accurate.10-13 Convergence alone should not be sought because this may reflect groupthink or clinical inertia.10,15 To improve discharge team performance over time,10‑13 it is important to assess not only patient’s readiness on the day of discharge but also how prepared the patient actually was for the recovery period following acute care. In the larger mixed-methods study, we found that teams’ with more convergent SMMs on teamwork quality were associated with patient’s reported quality of transition 30-days after discharge.9 Together, these findings further highlight the importance of aligning patient and interprofessional team members perspectives during the discharge planning, as well as providing clinicians with regular feedback about patient’s postdischarge experiences and outcomes.

To optimize team performance, the discharge planning process must be considered from an interprofessional team perspective as it functions in real-world practice settings. There are increasing pressures to discharge patients “quicker and sicker,” to simplify and standardize clinical process, and to provide patient-centered care.3,5-8 Without thoughtful interventions to facilitate communication during discharge planning, these pressures likely reinforce inaccurate assumptions regarding the work of fellow team members and force teams to think “fast” instead of “slow.”38-40 One approach to overcome such barriers is to focus on building a high-quality interprofessional SMM around discharge readiness. For example, the RHDS/SF questions could be integrated into the electronic medical records, displayed on dashboards, and discussed regularly during discharge rounds. In particular, to strengthen the team’s SMM and quality of teamwork, together the staff can ask three practical questions (Appendix F): (1) Do we think the patient is ready for discharge? (2) To what extent do we all agree the patient is ready for discharge? (3) Does our assessment of discharge readiness match the patient’s? During this high-risk transition point, asking these questions might allow the team to move from thinking fast to thinking slowly so they can more effectively identify heuristics they may be using inaccurately, prevent blind spots, and move toward high reliability.10,13,18,38-40

This study has limitations. First, events were recruited from patients with any of only six conditions at a single hospital. Other settings, patient condition types, or team compositions of other clinicians may differ in results. Second, in this study the SMM content was focused on readiness for hospital discharge among four key stakeholders. It is possible other SMM content needs to be shared among the interprofessional discharge team (eg, caregivers’ perspectives,2,6-8 resource availability,3-6 clinicians’ roles4,9) or additional members should be included (eg, physical therapists, nursing assistants, home health consultants, or primary care clinicians). Although this study focused on a patient-centered outcome (Patient-RHDS/SF), we did not examine other important outcomes such as hospital readmission. Additionally, due to the small sample size, these results have limited generalizability and should be interpreted with caution. Last, we limited data collection to the day of hospital discharge; future studies might consider assessing discharge readiness throughout hospitalization.

CONCLUSION

Readying patients for hospital discharge is a time-sensitivehigh-risk task requiring multiple healthcare professionals to concurrently assess patient needs, formulate an anticipatory care plan, provide education, and arrange for postdischarge needs.20,21 Despite this, few studies have analyzed teamwork aspects to understand how these transitions could be improved.9 By piloting SMM measurement and describing factors that affect SMMs, we provide a step toward identifying and evaluating strategies to assist interprofessional care teams in preparing patients for a safe, high-quality, patient-centered hospital discharge.

Presentations

This work was presented at the Midwest Nursing Research Society’s 2018 Annual Research Conference in Cleveland, Ohio, as well as at AcademyHealth’s 2019 Annual Research Meeting in Washington, District of Columbia.

- Greysen SR, Schiliro D, Horwitz LI, Curry L, Bradley E. “Out of sight, out of mind”: house staff perceptions of quality-limiting factors in discharge care at teaching hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):376-381.https://doi.org/10.1002/%20jhm.1928

- Fuji KT, Abbott AA, Norris JF. Exploring care transitions from patient, caregiver, and health-care provider perspectives. Clin Nurs Res. 2013;22(3):258-274. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054773812465084

- Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL, Coleman EA. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):314-323. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.228

- Waring J, Bishop S, Marshall F. A qualitative study of professional and career perceptions of the threats to safe hospital discharge for stroke and hip fracture patients in the English National Health Service. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:297. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1568-2

- Nosbusch JM, Weiss ME, Bobay KL. An integrated review of the literature on challenges confronting the acute care staff nurse in discharge planning. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(5-6):754-774. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03257.x

- Ashbrook L, Mourad M, Sehgal N. Communicating discharge instructions to patients: a survey of nurse, intern, and hospitalist practices. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(1):36-41. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1986

- Prusaczyk B, Kripalani S, Dhand A. Networks of hospital discharge planning teams and readmissions. J Interprof Care. 2019;33(1):85-92. https://doi.org/1 0.1080/13561820.2018.1515193

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Revisions to Requirements for Discharge Planning for Hospitals, Critical Access Hospitals, and Home Health Agencies, and Hospital and Critical Access Hospital Changes to Promote Innovation, Flexibility, and Improvement in Patient Care. Septemeber 30, 2019. Federal Register. Accessed May 24, 2021. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/09/30/2019-20732/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-revisions-to-requirements-for-discharge-planning-for-hospitals

- Manges K, Groves PS, Farag A, Peterson R, Harton J, Greysen SR. A mixed methods study examining teamwork shared mental models of interprofessional teams during hospital discharge. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29(6):499-508. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009716

- Mohammed S, Ferzandi L, Hamilton K. Metaphor no more: a 15-year review of the team mental model construct. J Manage. 2010;36(4):876-910. https:// doi.org/10.1177%2F0149206309356804

- Langan-Fox J, Code S, Langfield-Smith K. Team mental models: techniques, methods, and analytic approaches. Hum Factors. 2000;42(2);242-271. https:// doi.org/10.1518/001872000779656534

- Lim BC, Klein KJ. Team mental models and team performance: a field study of the effects of team mental model similarity and accuracy. J Organ Behav. 2006;27(4):403-418. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.387

- Burtscher MJ, Manser T. Team mental models and their potential to improve teamwork and safety: a review and implications for future research in healthcare. Safety Sci. 2012;50(5):1344-1354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ssci.2011.12.033

- Calder LA, Mastoras G, Rahimpour M, et al. Team communication patterns in emergency resuscitation: a mixed methods qualitative analysis. Int J Emerg Med. 2017:10(1):24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-017-0149-4