User login

Common Ground: Primary Care and Specialty Clinicians’ Perceptions of E-Consults in the Veterans Health Administration

Electronic consultation (e-consult) is designed to increase access to specialty care by facilitating communication between primary care and specialty clinicians without the need for outpatient face-to-face encounters.1–4 In 2011, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) implemented an e-consult program as a component of its overall strategy to increase access to specialty services, reduce costs of care, and reduce appointment travel burden on patients.

E-consult has substantially increased within the VA since its implementation.5,6 Consistent with limited evaluations from other health care systems, evaluations of the VA e-consult program demonstrated reduced costs, reduced travel time for patients, and improved access to specialty care.2,5–11 However, there is wide variation in e-consult use across VA specialties, facilities, and regions.5,6,12,13 For example, hematology, preoperative evaluation, neurosurgery, endocrinology, and infectious diseases use e-consults more frequently when compared with in-person consults in the VA.6 Reasons for this variation or specific barriers and facilitators of using e-consults have not been described.

Prior qualitative studies report that primary care practitioners (PCPs) describe e-consults as convenient, educational, beneficial for patient care, and useful for improving patient access to specialty care.8,14,15 One study identified limited PCP knowledge of e-consults as a barrier to use.16 Specialists have reported that e-consult improves clinical communication, but increases their workload.1,14,17,18 These studies did not assess perspectives from both clinicians who initiate e-consults and those who respond to them. This is the first qualitative study to assess e-consult perceptions from perspectives of both PCPs and specialists among a large, national sample of VA clinicians who use e-consults. The objective of this study was to understand perspectives of e-consults between PCPs and specialists that may be relevant to increasing adoption in the VA.

Methods

The team (CL, ML, PG, 2 analysts under the guidance of GS and JS and support from RRK, and a biostatistician) conducted semistructured interviews with PCPs, specialists, and specialty division leaders who were employed by VA in 2016 and 2017. Specialties of interest were identified by the VA Office of Specialty Care and included cardiology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, and hematology.

E-Consult Procedures

Within the VA, the specific procedures used to initiate, triage and manage e-consults are coordinated at VA medical centers (VAMCs) and at the Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) regional level. E-consult can be requested by any clinician. Generally, e-consults are initiated by PCPs through standardized, specialty-specific templates. Recipients, typically specialists, respond by answering questions, suggesting additional testing and evaluation, or requesting an in-person visit. Communication is documented in the patient’s electronic health record (EHR). Specialists receive different levels of workload credit for responding to e-consults similar to a relative value unit reimbursement model. Training in the use of e-consults is available to practitioners but may vary at local and regional levels.

Recruitment

Our sample included PCPs, specialists, and specialty care division leaders. We first quantified e-consult rates (e-consults per 100 patient visits) between July 2016 and June 2017 at VA facilities within primary care and the 4 priority specialties and identified the 30 sites with the highest e-consult rates and 30 sites with the lowest e-consult rates. Sites with < 500 total visits, < 3 specialties, or without any e-consult visit during the study period were excluded. E-consult rates at community-based outpatient clinics were included with associated VAMCs. We then stratified PCPs by whether they were high or low users of e-consults (determined by the top and bottom users within each site) and credentials (MD vs nurse practitioner [NP] or physician assistant [PA]). Specialists were sampled based on their rate of use relative to colleagues within their site and the use rate of their division. We sampled division chiefs and individuals who had > 300 total visits and 1 e-consult during the study period. To recruit participants, the primary investigator sent an initial email and 2 reminder emails. The team followed up with respondents to schedule an interview.

Interview guides were designed to elicit rich descriptions of barriers and facilitators to e-consult use (eAppendix available at doi:10.12788/fp.0214). The team used the Practical Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM), which considers factors along 6 domains for intervention planning, implementation, and sustainment.19 Telephone interviews lasted about 20 minutes and were conducted between September 2017 and March 2018. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

The team used an iterative, team-based, inductive/deductive approach to conventional content analysis.20,21 Initial code categories were created so that we could identify e-consult best practices—facilitators of e-consult that were recommended by both PCPs and specialists. Inductive codes or labels applied to identify meaningful quotations, phrases, or key terms were used to identify emergent ideas and were added throughout coding after discussion among team members. Consensus was reached using a team-based approach.21 Four analysts independently coded the same 3 transcripts and met to discuss points of divergence and convergence. Analyses continued with emergent themes, categories, and conclusions. Atlas.ti. v.7 was used for coding and data management.22

Results

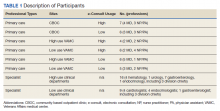

We conducted 34 interviews with clinicians (Table 1) from 13 VISNs. Four best-practice themes emerged among both PCPs and specialists, including that e-consults (1) are best suited for certain clinical questions and patients; (2) require relevant background information from requesting clinicians and clear recommendations from responding clinicians; (3) are a novel opportunity to provide efficient, transparent care; and (4) may not be fully adopted due to low awareness. Supporting quotations for the following findings are provided in Table 2.

Specific Clinical Questions and Patients

PCPs described specific patients and questions for which they most frequently used e-consults, such as for medication changes (Q1), determining treatment steps (Q2,3), and or clarifying laboratory or imaging findings. PCPs frequently used e-consults for patients who did not require a physical examination or when specialists could make recommendations without seeing patients face-to-face (Q3). An important use of e-consults described by PCPs was for treating conditions they could manage within primary care if additional guidance were available (Q4). Several PCPs and specialists also noted that e-consults were particularly useful for patients who were unable to travel or did not want face-to-face appointments (Q5). Notably, PCPs and specialists mentioned situations for which e-consults were inappropriate, including when a detailed history or physical examination was needed, or if a complex condition was suspected (Q6).

Background Data and Clear Recommendations

Participants described necessary data that should be included in high-quality e-consults. Specialists voiced frustration in time-consuming chart reviews that were often necessary when these data were not provided by the requestor. In some cases, specialists were unable to access necessary EHR data, which delayed responses (Q7). PCPs noted that the most useful responses carefully considered the question, used current patient information to determine treatments, provided clear recommendations, and defined who was responsible for next steps (Q8). PCPs and specialists stated that e-consult templates that required relevant information facilitated high-quality e-consults. Neither wanted to waste the other clinician's time (Q8).

A Novel Opportunity

Many PCPs felt that e-consults improved communication (eg, efficiency, response time), established new communication between clinicians, and reduced patients’ appointment burden (Q10, Q11). Many specialists felt that e-consults improved documentation of communication between clinicians and increased transparency of clinical decisions (Q12). Additionally, many specialists mentioned that e-consults capture previously informal curbside consults, enabling them to receive workload credit (Q13).

Lack of Awareness

Some noted that the biggest barrier to e-consults was not being aware of them generally, or which specialties offer e-consults (Q14). One PCP described e-consults as the best kept secret and found value in sharing the utility of e-consults with colleagues (Q15). All participants, including those who did not frequently use e-consults, felt that e-consults improved the quality of care by providing more timely care or better answers to clinical questions (Q16). Several practitioners also felt that e-consults increased access to specialty care. For example, specialists reported that e-consults enabled them to better manage patient load by using e-consults to answer relatively simple questions, reserving face-to-face consults for more complex patients (Q17).

Discussion

The objective of this study was to identify potential best practices for e-consults that may help increase their quality and use within the VA. We built on prior studies that offered insights on PCP and specialists’ overall satisfaction with e-consult by identifying several themes relevant to the further adoption of e-consults in the VA and elsewhere without a face-to-face visit.8,13,14,16–18 Future work may be beneficial in identifying whether the study themes identified can explain variation in e-consult use or whether addressing these factors might lead to increased or higher quality e-consult use. We are unaware of any qualitative study of comparable scale in a different health care system. Further, this is the first study to assess perspectives on e-consults among those who initiate and respond to them within the same health care system. Perhaps the most important finding from this study is that e-consults are generally viewed favorably, which is a necessary leverage point to increase their adoption within the system.

Clinicians reported several benefits to e-consults, including timely responses to clinical questions, efficient communication, allow for documentation of specialist recommendations, and help capture workload. These benefits are consistent with prior literature that indicates both PCPs and specialists in the VA and other health care systems feel that e-consults improves communication, decreases unnecessary visits, and improves quality of care.1,14,17,18 In particular, clinicians reported that e-consults improve their practice efficiency and efficacy. This is of critical importance given the pressures of providing timely access to primary and specialty care within the VA. Interestingly, many VA practitioners were unaware which specialties offered e-consults within their facilities, reflecting previous work showing that PCPs are often unaware of e-consult options.16 This may partially explain variation in e-consult use. Increasing awareness and educating clinicians on the benefits of e-consults may help promote use among non- and low users.

A common theme reported by both groups was the importance of providing necessary information within e-consult questions and responses. Specialists felt there was a need to ensure that PCPs provide relevant and patient-specific information that would enable them to efficiently and accurately answer questions without the need for extensive EHR review. This reflects previous work showing that specialists are often unable to respond to e-consult requests because they do not contain sufficient information.22 PCPs described a need to ensure that specialists’ responses included information that was detailed enough to make clinical decisions without the need for a reconsult. This highlights a common challenge to medical consultation, in that necessary or relevant information may not be apparent to all clinicians. To address this, there may be a role in developing enhanced, flexible templating that elicits necessary patient-specific information. Such a template may automatically pull relevant data from the EHR and prompt clinicians to provide important information. We did not assess how perspectives of templates varied, and further work could help define precisely what constitutes an effective template, including how it should capture appropriate patient data and how this impacts acceptability or use of e-consults generally. Collaboratively developed service agreements and e-consult templates could help guide PCPs and specialists to engage in efficient communication.

Another theme among both groups was that e-consult is most appropriate within specific clinical scenarios. Examples included review of laboratory results, questions about medication changes, or for patients who were reluctant to travel to appointments. Identifying and promoting specific opportunities for e-consults may help increase their use and align e-consult practices with scenarios that are likely to provide the most benefit to patients. For example, it could be helpful to understand the distance patients must travel for specialty care. Providing that information during clinical encounters could trigger clinicians to consider e-consults as an option. Future work might aim to identify clinical scenarios that clinicians feel are not well suited for e-consults and determine how to adapt them for those scenarios.

Limitations

Generalizability of these findings is limited given the qualitative study design. Participants’ descriptions of experiences with e-consults reflect the experiences of clinicians in the VA and may not reflect clinicians in other settings. We also interviewed a sample of clinicians who were already using e-consults. Important information could be learned from future work with those who have not yet adopted e-consult procedures or adopted and abandoned them.

Conclusions

E-consult is perceived as beneficial by VA PCPs and specialists. Participants suggested using e-consults for appropriate questions or patients and including necessary information and next steps in both the initial e-consult and response. Finding ways to facilitate e-consults with these suggestions in mind may increase delivery of high-quality e-consults. Future work could compare the findings of this work to similar work assessing clinicians perceptions of e-consults outside of the VA.

1. Battaglia C, Lambert-Kerzner A, Aron DC, et al. Evaluation of e-consults in the VHA: provider perspectives. Fed Pract. 2015;32(7):42-48.

2. Haverhals LM, Sayre G, Helfrich CD, et al. E-consult implementation: lessons learned using consolidated framework for implementation research. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(12):e640-e647. Published 2015 Dec 1.

3. Sewell JL, Telischak KS, Day LW, Kirschner N, Weissman A. Preconsultation exchange in the United States: use, awareness, and attitudes. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(12):e556-e564. Published 2014 Dec 1.

4. Horner K, Wagner E, Tufano J. Electronic consultations between primary and specialty care clinicians: early insights. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2011;23:1-14.

5. Kirsh S, Carey E, Aron DC, et al. Impact of a national specialty e-consultation implementation project on access. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(12):e648-654. Published 2015 Dec 1.

6. Saxon DR, Kaboli PJ, Haraldsson B, Wilson C, Ohl M, Augustine MR. Growth of electronic consultations in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care. 2021;27(1):12-19. doi:10.37765/ajmc.2021.88572

7. Olayiwola JN, Anderson D, Jepeal N, et al. Electronic consultations to improve the primary care-specialty care interface for cardiology in the medically underserved: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(2):133-140. doi:10.1370/afm.1869

8. Schettini P, Shah KP, O’Leary CP, et al. Keeping care connected: e-Consultation program improves access to nephrology care. J Telemed Telecare. 2019;25(3):142-150. doi:10.1177/1357633X17748350

9. Whittington MD, Ho PM, Kirsh SR, et al. Cost savings associated with electronic specialty consultations. Am J Manag Care. 2021;27(1):e16-e23. Published 2021 Jan 1. doi:10.37765/ajmc.2021.88579

10. Shipherd JC, Kauth MR, Matza A. Nationwide interdisciplinary e-consultation on transgender care in the Veterans Health Administration. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(12):1008-1012. doi:10.1089/tmj.2016.0013

11. Strymish J, Gupte G, Afable MK, et al. Electronic consultations (E-consults): advancing infectious disease care in a large Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(8):1123-1125. doi:10.1093/cid/cix058

12. Williams KM, Kirsh S, Aron D, et al. Evaluation of the Veterans Health Administration’s Specialty Care Transformational Initiatives to promote patient-centered delivery of specialty care: a mixed-methods approach. Telemed J E-Health. 2017;23(7):577-589. doi:10.1089/tmj.2016.0166

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Specialty Care Transformational Initiative Evaluation Center. Evaluation of specialty care initiatives. Published 2013.

14. Vimalananda VG, Gupte G, Seraj SM, et al. Electronic consultations (e-consults) to improve access to specialty care: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. J Telemed Telecare. 2015;21(6):323-330. doi:10.1177/1357633X15582108

15. Lee M, Leonard C, Greene P, et al. Perspectives of VA primary care clinicians toward electronic consultation-related workload burden. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2018104. Published 2020 Oct 1. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.18104

16. Deeds SA, Dowdell KJ, Chew LD, Ackerman SL. Implementing an opt-in eConsult program at seven academic medical centers: a qualitative analysis of primary care provider experiences. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(8):1427-1433. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05067-7

17. Rodriguez KL, Burkitt KH, Bayliss NK, et al. Veteran, primary care provider, and specialist satisfaction with electronic consultation. JMIR Med Inform. 2015;3(1):e5. Published 2015 Jan 14. doi:10.2196/medinform.3725

18. Gupte G, Vimalananda V, Simon SR, DeVito K, Clark J, Orlander JD. Disruptive innovation: implementation of electronic consultations in a Veterans Affairs Health Care System. JMIR Med Inform. 2016;4(1):e6. Published 2016 Feb 12. doi:10.2196/medinform.4801

19. Feldstein AC, Glasgow RE. A practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) for integrating research findings into practice. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(4):228-243. doi:10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34030-6

20. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Sage Publications; 2002.

21. Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758-1772. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x

22. Kim EJ, Orlander JD, Afable M, et al. Cardiology electronic consultation (e-consult) use by primary care providers at VA medical centres in New England. J Telemed Telecare. 2019;25(6):370-377. doi:10.1177/1357633X18774468

Electronic consultation (e-consult) is designed to increase access to specialty care by facilitating communication between primary care and specialty clinicians without the need for outpatient face-to-face encounters.1–4 In 2011, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) implemented an e-consult program as a component of its overall strategy to increase access to specialty services, reduce costs of care, and reduce appointment travel burden on patients.

E-consult has substantially increased within the VA since its implementation.5,6 Consistent with limited evaluations from other health care systems, evaluations of the VA e-consult program demonstrated reduced costs, reduced travel time for patients, and improved access to specialty care.2,5–11 However, there is wide variation in e-consult use across VA specialties, facilities, and regions.5,6,12,13 For example, hematology, preoperative evaluation, neurosurgery, endocrinology, and infectious diseases use e-consults more frequently when compared with in-person consults in the VA.6 Reasons for this variation or specific barriers and facilitators of using e-consults have not been described.

Prior qualitative studies report that primary care practitioners (PCPs) describe e-consults as convenient, educational, beneficial for patient care, and useful for improving patient access to specialty care.8,14,15 One study identified limited PCP knowledge of e-consults as a barrier to use.16 Specialists have reported that e-consult improves clinical communication, but increases their workload.1,14,17,18 These studies did not assess perspectives from both clinicians who initiate e-consults and those who respond to them. This is the first qualitative study to assess e-consult perceptions from perspectives of both PCPs and specialists among a large, national sample of VA clinicians who use e-consults. The objective of this study was to understand perspectives of e-consults between PCPs and specialists that may be relevant to increasing adoption in the VA.

Methods

The team (CL, ML, PG, 2 analysts under the guidance of GS and JS and support from RRK, and a biostatistician) conducted semistructured interviews with PCPs, specialists, and specialty division leaders who were employed by VA in 2016 and 2017. Specialties of interest were identified by the VA Office of Specialty Care and included cardiology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, and hematology.

E-Consult Procedures

Within the VA, the specific procedures used to initiate, triage and manage e-consults are coordinated at VA medical centers (VAMCs) and at the Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) regional level. E-consult can be requested by any clinician. Generally, e-consults are initiated by PCPs through standardized, specialty-specific templates. Recipients, typically specialists, respond by answering questions, suggesting additional testing and evaluation, or requesting an in-person visit. Communication is documented in the patient’s electronic health record (EHR). Specialists receive different levels of workload credit for responding to e-consults similar to a relative value unit reimbursement model. Training in the use of e-consults is available to practitioners but may vary at local and regional levels.

Recruitment

Our sample included PCPs, specialists, and specialty care division leaders. We first quantified e-consult rates (e-consults per 100 patient visits) between July 2016 and June 2017 at VA facilities within primary care and the 4 priority specialties and identified the 30 sites with the highest e-consult rates and 30 sites with the lowest e-consult rates. Sites with < 500 total visits, < 3 specialties, or without any e-consult visit during the study period were excluded. E-consult rates at community-based outpatient clinics were included with associated VAMCs. We then stratified PCPs by whether they were high or low users of e-consults (determined by the top and bottom users within each site) and credentials (MD vs nurse practitioner [NP] or physician assistant [PA]). Specialists were sampled based on their rate of use relative to colleagues within their site and the use rate of their division. We sampled division chiefs and individuals who had > 300 total visits and 1 e-consult during the study period. To recruit participants, the primary investigator sent an initial email and 2 reminder emails. The team followed up with respondents to schedule an interview.

Interview guides were designed to elicit rich descriptions of barriers and facilitators to e-consult use (eAppendix available at doi:10.12788/fp.0214). The team used the Practical Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM), which considers factors along 6 domains for intervention planning, implementation, and sustainment.19 Telephone interviews lasted about 20 minutes and were conducted between September 2017 and March 2018. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

The team used an iterative, team-based, inductive/deductive approach to conventional content analysis.20,21 Initial code categories were created so that we could identify e-consult best practices—facilitators of e-consult that were recommended by both PCPs and specialists. Inductive codes or labels applied to identify meaningful quotations, phrases, or key terms were used to identify emergent ideas and were added throughout coding after discussion among team members. Consensus was reached using a team-based approach.21 Four analysts independently coded the same 3 transcripts and met to discuss points of divergence and convergence. Analyses continued with emergent themes, categories, and conclusions. Atlas.ti. v.7 was used for coding and data management.22

Results

We conducted 34 interviews with clinicians (Table 1) from 13 VISNs. Four best-practice themes emerged among both PCPs and specialists, including that e-consults (1) are best suited for certain clinical questions and patients; (2) require relevant background information from requesting clinicians and clear recommendations from responding clinicians; (3) are a novel opportunity to provide efficient, transparent care; and (4) may not be fully adopted due to low awareness. Supporting quotations for the following findings are provided in Table 2.

Specific Clinical Questions and Patients

PCPs described specific patients and questions for which they most frequently used e-consults, such as for medication changes (Q1), determining treatment steps (Q2,3), and or clarifying laboratory or imaging findings. PCPs frequently used e-consults for patients who did not require a physical examination or when specialists could make recommendations without seeing patients face-to-face (Q3). An important use of e-consults described by PCPs was for treating conditions they could manage within primary care if additional guidance were available (Q4). Several PCPs and specialists also noted that e-consults were particularly useful for patients who were unable to travel or did not want face-to-face appointments (Q5). Notably, PCPs and specialists mentioned situations for which e-consults were inappropriate, including when a detailed history or physical examination was needed, or if a complex condition was suspected (Q6).

Background Data and Clear Recommendations

Participants described necessary data that should be included in high-quality e-consults. Specialists voiced frustration in time-consuming chart reviews that were often necessary when these data were not provided by the requestor. In some cases, specialists were unable to access necessary EHR data, which delayed responses (Q7). PCPs noted that the most useful responses carefully considered the question, used current patient information to determine treatments, provided clear recommendations, and defined who was responsible for next steps (Q8). PCPs and specialists stated that e-consult templates that required relevant information facilitated high-quality e-consults. Neither wanted to waste the other clinician's time (Q8).

A Novel Opportunity

Many PCPs felt that e-consults improved communication (eg, efficiency, response time), established new communication between clinicians, and reduced patients’ appointment burden (Q10, Q11). Many specialists felt that e-consults improved documentation of communication between clinicians and increased transparency of clinical decisions (Q12). Additionally, many specialists mentioned that e-consults capture previously informal curbside consults, enabling them to receive workload credit (Q13).

Lack of Awareness

Some noted that the biggest barrier to e-consults was not being aware of them generally, or which specialties offer e-consults (Q14). One PCP described e-consults as the best kept secret and found value in sharing the utility of e-consults with colleagues (Q15). All participants, including those who did not frequently use e-consults, felt that e-consults improved the quality of care by providing more timely care or better answers to clinical questions (Q16). Several practitioners also felt that e-consults increased access to specialty care. For example, specialists reported that e-consults enabled them to better manage patient load by using e-consults to answer relatively simple questions, reserving face-to-face consults for more complex patients (Q17).

Discussion

The objective of this study was to identify potential best practices for e-consults that may help increase their quality and use within the VA. We built on prior studies that offered insights on PCP and specialists’ overall satisfaction with e-consult by identifying several themes relevant to the further adoption of e-consults in the VA and elsewhere without a face-to-face visit.8,13,14,16–18 Future work may be beneficial in identifying whether the study themes identified can explain variation in e-consult use or whether addressing these factors might lead to increased or higher quality e-consult use. We are unaware of any qualitative study of comparable scale in a different health care system. Further, this is the first study to assess perspectives on e-consults among those who initiate and respond to them within the same health care system. Perhaps the most important finding from this study is that e-consults are generally viewed favorably, which is a necessary leverage point to increase their adoption within the system.

Clinicians reported several benefits to e-consults, including timely responses to clinical questions, efficient communication, allow for documentation of specialist recommendations, and help capture workload. These benefits are consistent with prior literature that indicates both PCPs and specialists in the VA and other health care systems feel that e-consults improves communication, decreases unnecessary visits, and improves quality of care.1,14,17,18 In particular, clinicians reported that e-consults improve their practice efficiency and efficacy. This is of critical importance given the pressures of providing timely access to primary and specialty care within the VA. Interestingly, many VA practitioners were unaware which specialties offered e-consults within their facilities, reflecting previous work showing that PCPs are often unaware of e-consult options.16 This may partially explain variation in e-consult use. Increasing awareness and educating clinicians on the benefits of e-consults may help promote use among non- and low users.

A common theme reported by both groups was the importance of providing necessary information within e-consult questions and responses. Specialists felt there was a need to ensure that PCPs provide relevant and patient-specific information that would enable them to efficiently and accurately answer questions without the need for extensive EHR review. This reflects previous work showing that specialists are often unable to respond to e-consult requests because they do not contain sufficient information.22 PCPs described a need to ensure that specialists’ responses included information that was detailed enough to make clinical decisions without the need for a reconsult. This highlights a common challenge to medical consultation, in that necessary or relevant information may not be apparent to all clinicians. To address this, there may be a role in developing enhanced, flexible templating that elicits necessary patient-specific information. Such a template may automatically pull relevant data from the EHR and prompt clinicians to provide important information. We did not assess how perspectives of templates varied, and further work could help define precisely what constitutes an effective template, including how it should capture appropriate patient data and how this impacts acceptability or use of e-consults generally. Collaboratively developed service agreements and e-consult templates could help guide PCPs and specialists to engage in efficient communication.

Another theme among both groups was that e-consult is most appropriate within specific clinical scenarios. Examples included review of laboratory results, questions about medication changes, or for patients who were reluctant to travel to appointments. Identifying and promoting specific opportunities for e-consults may help increase their use and align e-consult practices with scenarios that are likely to provide the most benefit to patients. For example, it could be helpful to understand the distance patients must travel for specialty care. Providing that information during clinical encounters could trigger clinicians to consider e-consults as an option. Future work might aim to identify clinical scenarios that clinicians feel are not well suited for e-consults and determine how to adapt them for those scenarios.

Limitations

Generalizability of these findings is limited given the qualitative study design. Participants’ descriptions of experiences with e-consults reflect the experiences of clinicians in the VA and may not reflect clinicians in other settings. We also interviewed a sample of clinicians who were already using e-consults. Important information could be learned from future work with those who have not yet adopted e-consult procedures or adopted and abandoned them.

Conclusions

E-consult is perceived as beneficial by VA PCPs and specialists. Participants suggested using e-consults for appropriate questions or patients and including necessary information and next steps in both the initial e-consult and response. Finding ways to facilitate e-consults with these suggestions in mind may increase delivery of high-quality e-consults. Future work could compare the findings of this work to similar work assessing clinicians perceptions of e-consults outside of the VA.

Electronic consultation (e-consult) is designed to increase access to specialty care by facilitating communication between primary care and specialty clinicians without the need for outpatient face-to-face encounters.1–4 In 2011, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) implemented an e-consult program as a component of its overall strategy to increase access to specialty services, reduce costs of care, and reduce appointment travel burden on patients.

E-consult has substantially increased within the VA since its implementation.5,6 Consistent with limited evaluations from other health care systems, evaluations of the VA e-consult program demonstrated reduced costs, reduced travel time for patients, and improved access to specialty care.2,5–11 However, there is wide variation in e-consult use across VA specialties, facilities, and regions.5,6,12,13 For example, hematology, preoperative evaluation, neurosurgery, endocrinology, and infectious diseases use e-consults more frequently when compared with in-person consults in the VA.6 Reasons for this variation or specific barriers and facilitators of using e-consults have not been described.

Prior qualitative studies report that primary care practitioners (PCPs) describe e-consults as convenient, educational, beneficial for patient care, and useful for improving patient access to specialty care.8,14,15 One study identified limited PCP knowledge of e-consults as a barrier to use.16 Specialists have reported that e-consult improves clinical communication, but increases their workload.1,14,17,18 These studies did not assess perspectives from both clinicians who initiate e-consults and those who respond to them. This is the first qualitative study to assess e-consult perceptions from perspectives of both PCPs and specialists among a large, national sample of VA clinicians who use e-consults. The objective of this study was to understand perspectives of e-consults between PCPs and specialists that may be relevant to increasing adoption in the VA.

Methods

The team (CL, ML, PG, 2 analysts under the guidance of GS and JS and support from RRK, and a biostatistician) conducted semistructured interviews with PCPs, specialists, and specialty division leaders who were employed by VA in 2016 and 2017. Specialties of interest were identified by the VA Office of Specialty Care and included cardiology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, and hematology.

E-Consult Procedures

Within the VA, the specific procedures used to initiate, triage and manage e-consults are coordinated at VA medical centers (VAMCs) and at the Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) regional level. E-consult can be requested by any clinician. Generally, e-consults are initiated by PCPs through standardized, specialty-specific templates. Recipients, typically specialists, respond by answering questions, suggesting additional testing and evaluation, or requesting an in-person visit. Communication is documented in the patient’s electronic health record (EHR). Specialists receive different levels of workload credit for responding to e-consults similar to a relative value unit reimbursement model. Training in the use of e-consults is available to practitioners but may vary at local and regional levels.

Recruitment

Our sample included PCPs, specialists, and specialty care division leaders. We first quantified e-consult rates (e-consults per 100 patient visits) between July 2016 and June 2017 at VA facilities within primary care and the 4 priority specialties and identified the 30 sites with the highest e-consult rates and 30 sites with the lowest e-consult rates. Sites with < 500 total visits, < 3 specialties, or without any e-consult visit during the study period were excluded. E-consult rates at community-based outpatient clinics were included with associated VAMCs. We then stratified PCPs by whether they were high or low users of e-consults (determined by the top and bottom users within each site) and credentials (MD vs nurse practitioner [NP] or physician assistant [PA]). Specialists were sampled based on their rate of use relative to colleagues within their site and the use rate of their division. We sampled division chiefs and individuals who had > 300 total visits and 1 e-consult during the study period. To recruit participants, the primary investigator sent an initial email and 2 reminder emails. The team followed up with respondents to schedule an interview.

Interview guides were designed to elicit rich descriptions of barriers and facilitators to e-consult use (eAppendix available at doi:10.12788/fp.0214). The team used the Practical Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM), which considers factors along 6 domains for intervention planning, implementation, and sustainment.19 Telephone interviews lasted about 20 minutes and were conducted between September 2017 and March 2018. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

The team used an iterative, team-based, inductive/deductive approach to conventional content analysis.20,21 Initial code categories were created so that we could identify e-consult best practices—facilitators of e-consult that were recommended by both PCPs and specialists. Inductive codes or labels applied to identify meaningful quotations, phrases, or key terms were used to identify emergent ideas and were added throughout coding after discussion among team members. Consensus was reached using a team-based approach.21 Four analysts independently coded the same 3 transcripts and met to discuss points of divergence and convergence. Analyses continued with emergent themes, categories, and conclusions. Atlas.ti. v.7 was used for coding and data management.22

Results

We conducted 34 interviews with clinicians (Table 1) from 13 VISNs. Four best-practice themes emerged among both PCPs and specialists, including that e-consults (1) are best suited for certain clinical questions and patients; (2) require relevant background information from requesting clinicians and clear recommendations from responding clinicians; (3) are a novel opportunity to provide efficient, transparent care; and (4) may not be fully adopted due to low awareness. Supporting quotations for the following findings are provided in Table 2.

Specific Clinical Questions and Patients

PCPs described specific patients and questions for which they most frequently used e-consults, such as for medication changes (Q1), determining treatment steps (Q2,3), and or clarifying laboratory or imaging findings. PCPs frequently used e-consults for patients who did not require a physical examination or when specialists could make recommendations without seeing patients face-to-face (Q3). An important use of e-consults described by PCPs was for treating conditions they could manage within primary care if additional guidance were available (Q4). Several PCPs and specialists also noted that e-consults were particularly useful for patients who were unable to travel or did not want face-to-face appointments (Q5). Notably, PCPs and specialists mentioned situations for which e-consults were inappropriate, including when a detailed history or physical examination was needed, or if a complex condition was suspected (Q6).

Background Data and Clear Recommendations

Participants described necessary data that should be included in high-quality e-consults. Specialists voiced frustration in time-consuming chart reviews that were often necessary when these data were not provided by the requestor. In some cases, specialists were unable to access necessary EHR data, which delayed responses (Q7). PCPs noted that the most useful responses carefully considered the question, used current patient information to determine treatments, provided clear recommendations, and defined who was responsible for next steps (Q8). PCPs and specialists stated that e-consult templates that required relevant information facilitated high-quality e-consults. Neither wanted to waste the other clinician's time (Q8).

A Novel Opportunity

Many PCPs felt that e-consults improved communication (eg, efficiency, response time), established new communication between clinicians, and reduced patients’ appointment burden (Q10, Q11). Many specialists felt that e-consults improved documentation of communication between clinicians and increased transparency of clinical decisions (Q12). Additionally, many specialists mentioned that e-consults capture previously informal curbside consults, enabling them to receive workload credit (Q13).

Lack of Awareness

Some noted that the biggest barrier to e-consults was not being aware of them generally, or which specialties offer e-consults (Q14). One PCP described e-consults as the best kept secret and found value in sharing the utility of e-consults with colleagues (Q15). All participants, including those who did not frequently use e-consults, felt that e-consults improved the quality of care by providing more timely care or better answers to clinical questions (Q16). Several practitioners also felt that e-consults increased access to specialty care. For example, specialists reported that e-consults enabled them to better manage patient load by using e-consults to answer relatively simple questions, reserving face-to-face consults for more complex patients (Q17).

Discussion

The objective of this study was to identify potential best practices for e-consults that may help increase their quality and use within the VA. We built on prior studies that offered insights on PCP and specialists’ overall satisfaction with e-consult by identifying several themes relevant to the further adoption of e-consults in the VA and elsewhere without a face-to-face visit.8,13,14,16–18 Future work may be beneficial in identifying whether the study themes identified can explain variation in e-consult use or whether addressing these factors might lead to increased or higher quality e-consult use. We are unaware of any qualitative study of comparable scale in a different health care system. Further, this is the first study to assess perspectives on e-consults among those who initiate and respond to them within the same health care system. Perhaps the most important finding from this study is that e-consults are generally viewed favorably, which is a necessary leverage point to increase their adoption within the system.

Clinicians reported several benefits to e-consults, including timely responses to clinical questions, efficient communication, allow for documentation of specialist recommendations, and help capture workload. These benefits are consistent with prior literature that indicates both PCPs and specialists in the VA and other health care systems feel that e-consults improves communication, decreases unnecessary visits, and improves quality of care.1,14,17,18 In particular, clinicians reported that e-consults improve their practice efficiency and efficacy. This is of critical importance given the pressures of providing timely access to primary and specialty care within the VA. Interestingly, many VA practitioners were unaware which specialties offered e-consults within their facilities, reflecting previous work showing that PCPs are often unaware of e-consult options.16 This may partially explain variation in e-consult use. Increasing awareness and educating clinicians on the benefits of e-consults may help promote use among non- and low users.

A common theme reported by both groups was the importance of providing necessary information within e-consult questions and responses. Specialists felt there was a need to ensure that PCPs provide relevant and patient-specific information that would enable them to efficiently and accurately answer questions without the need for extensive EHR review. This reflects previous work showing that specialists are often unable to respond to e-consult requests because they do not contain sufficient information.22 PCPs described a need to ensure that specialists’ responses included information that was detailed enough to make clinical decisions without the need for a reconsult. This highlights a common challenge to medical consultation, in that necessary or relevant information may not be apparent to all clinicians. To address this, there may be a role in developing enhanced, flexible templating that elicits necessary patient-specific information. Such a template may automatically pull relevant data from the EHR and prompt clinicians to provide important information. We did not assess how perspectives of templates varied, and further work could help define precisely what constitutes an effective template, including how it should capture appropriate patient data and how this impacts acceptability or use of e-consults generally. Collaboratively developed service agreements and e-consult templates could help guide PCPs and specialists to engage in efficient communication.

Another theme among both groups was that e-consult is most appropriate within specific clinical scenarios. Examples included review of laboratory results, questions about medication changes, or for patients who were reluctant to travel to appointments. Identifying and promoting specific opportunities for e-consults may help increase their use and align e-consult practices with scenarios that are likely to provide the most benefit to patients. For example, it could be helpful to understand the distance patients must travel for specialty care. Providing that information during clinical encounters could trigger clinicians to consider e-consults as an option. Future work might aim to identify clinical scenarios that clinicians feel are not well suited for e-consults and determine how to adapt them for those scenarios.

Limitations

Generalizability of these findings is limited given the qualitative study design. Participants’ descriptions of experiences with e-consults reflect the experiences of clinicians in the VA and may not reflect clinicians in other settings. We also interviewed a sample of clinicians who were already using e-consults. Important information could be learned from future work with those who have not yet adopted e-consult procedures or adopted and abandoned them.

Conclusions

E-consult is perceived as beneficial by VA PCPs and specialists. Participants suggested using e-consults for appropriate questions or patients and including necessary information and next steps in both the initial e-consult and response. Finding ways to facilitate e-consults with these suggestions in mind may increase delivery of high-quality e-consults. Future work could compare the findings of this work to similar work assessing clinicians perceptions of e-consults outside of the VA.

1. Battaglia C, Lambert-Kerzner A, Aron DC, et al. Evaluation of e-consults in the VHA: provider perspectives. Fed Pract. 2015;32(7):42-48.

2. Haverhals LM, Sayre G, Helfrich CD, et al. E-consult implementation: lessons learned using consolidated framework for implementation research. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(12):e640-e647. Published 2015 Dec 1.

3. Sewell JL, Telischak KS, Day LW, Kirschner N, Weissman A. Preconsultation exchange in the United States: use, awareness, and attitudes. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(12):e556-e564. Published 2014 Dec 1.

4. Horner K, Wagner E, Tufano J. Electronic consultations between primary and specialty care clinicians: early insights. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2011;23:1-14.

5. Kirsh S, Carey E, Aron DC, et al. Impact of a national specialty e-consultation implementation project on access. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(12):e648-654. Published 2015 Dec 1.

6. Saxon DR, Kaboli PJ, Haraldsson B, Wilson C, Ohl M, Augustine MR. Growth of electronic consultations in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care. 2021;27(1):12-19. doi:10.37765/ajmc.2021.88572

7. Olayiwola JN, Anderson D, Jepeal N, et al. Electronic consultations to improve the primary care-specialty care interface for cardiology in the medically underserved: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(2):133-140. doi:10.1370/afm.1869

8. Schettini P, Shah KP, O’Leary CP, et al. Keeping care connected: e-Consultation program improves access to nephrology care. J Telemed Telecare. 2019;25(3):142-150. doi:10.1177/1357633X17748350

9. Whittington MD, Ho PM, Kirsh SR, et al. Cost savings associated with electronic specialty consultations. Am J Manag Care. 2021;27(1):e16-e23. Published 2021 Jan 1. doi:10.37765/ajmc.2021.88579

10. Shipherd JC, Kauth MR, Matza A. Nationwide interdisciplinary e-consultation on transgender care in the Veterans Health Administration. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(12):1008-1012. doi:10.1089/tmj.2016.0013

11. Strymish J, Gupte G, Afable MK, et al. Electronic consultations (E-consults): advancing infectious disease care in a large Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(8):1123-1125. doi:10.1093/cid/cix058

12. Williams KM, Kirsh S, Aron D, et al. Evaluation of the Veterans Health Administration’s Specialty Care Transformational Initiatives to promote patient-centered delivery of specialty care: a mixed-methods approach. Telemed J E-Health. 2017;23(7):577-589. doi:10.1089/tmj.2016.0166

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Specialty Care Transformational Initiative Evaluation Center. Evaluation of specialty care initiatives. Published 2013.

14. Vimalananda VG, Gupte G, Seraj SM, et al. Electronic consultations (e-consults) to improve access to specialty care: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. J Telemed Telecare. 2015;21(6):323-330. doi:10.1177/1357633X15582108

15. Lee M, Leonard C, Greene P, et al. Perspectives of VA primary care clinicians toward electronic consultation-related workload burden. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2018104. Published 2020 Oct 1. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.18104

16. Deeds SA, Dowdell KJ, Chew LD, Ackerman SL. Implementing an opt-in eConsult program at seven academic medical centers: a qualitative analysis of primary care provider experiences. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(8):1427-1433. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05067-7

17. Rodriguez KL, Burkitt KH, Bayliss NK, et al. Veteran, primary care provider, and specialist satisfaction with electronic consultation. JMIR Med Inform. 2015;3(1):e5. Published 2015 Jan 14. doi:10.2196/medinform.3725

18. Gupte G, Vimalananda V, Simon SR, DeVito K, Clark J, Orlander JD. Disruptive innovation: implementation of electronic consultations in a Veterans Affairs Health Care System. JMIR Med Inform. 2016;4(1):e6. Published 2016 Feb 12. doi:10.2196/medinform.4801

19. Feldstein AC, Glasgow RE. A practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) for integrating research findings into practice. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(4):228-243. doi:10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34030-6

20. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Sage Publications; 2002.

21. Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758-1772. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x

22. Kim EJ, Orlander JD, Afable M, et al. Cardiology electronic consultation (e-consult) use by primary care providers at VA medical centres in New England. J Telemed Telecare. 2019;25(6):370-377. doi:10.1177/1357633X18774468

1. Battaglia C, Lambert-Kerzner A, Aron DC, et al. Evaluation of e-consults in the VHA: provider perspectives. Fed Pract. 2015;32(7):42-48.

2. Haverhals LM, Sayre G, Helfrich CD, et al. E-consult implementation: lessons learned using consolidated framework for implementation research. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(12):e640-e647. Published 2015 Dec 1.

3. Sewell JL, Telischak KS, Day LW, Kirschner N, Weissman A. Preconsultation exchange in the United States: use, awareness, and attitudes. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(12):e556-e564. Published 2014 Dec 1.

4. Horner K, Wagner E, Tufano J. Electronic consultations between primary and specialty care clinicians: early insights. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2011;23:1-14.

5. Kirsh S, Carey E, Aron DC, et al. Impact of a national specialty e-consultation implementation project on access. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(12):e648-654. Published 2015 Dec 1.

6. Saxon DR, Kaboli PJ, Haraldsson B, Wilson C, Ohl M, Augustine MR. Growth of electronic consultations in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care. 2021;27(1):12-19. doi:10.37765/ajmc.2021.88572

7. Olayiwola JN, Anderson D, Jepeal N, et al. Electronic consultations to improve the primary care-specialty care interface for cardiology in the medically underserved: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(2):133-140. doi:10.1370/afm.1869

8. Schettini P, Shah KP, O’Leary CP, et al. Keeping care connected: e-Consultation program improves access to nephrology care. J Telemed Telecare. 2019;25(3):142-150. doi:10.1177/1357633X17748350

9. Whittington MD, Ho PM, Kirsh SR, et al. Cost savings associated with electronic specialty consultations. Am J Manag Care. 2021;27(1):e16-e23. Published 2021 Jan 1. doi:10.37765/ajmc.2021.88579

10. Shipherd JC, Kauth MR, Matza A. Nationwide interdisciplinary e-consultation on transgender care in the Veterans Health Administration. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(12):1008-1012. doi:10.1089/tmj.2016.0013

11. Strymish J, Gupte G, Afable MK, et al. Electronic consultations (E-consults): advancing infectious disease care in a large Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(8):1123-1125. doi:10.1093/cid/cix058

12. Williams KM, Kirsh S, Aron D, et al. Evaluation of the Veterans Health Administration’s Specialty Care Transformational Initiatives to promote patient-centered delivery of specialty care: a mixed-methods approach. Telemed J E-Health. 2017;23(7):577-589. doi:10.1089/tmj.2016.0166

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Specialty Care Transformational Initiative Evaluation Center. Evaluation of specialty care initiatives. Published 2013.

14. Vimalananda VG, Gupte G, Seraj SM, et al. Electronic consultations (e-consults) to improve access to specialty care: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. J Telemed Telecare. 2015;21(6):323-330. doi:10.1177/1357633X15582108

15. Lee M, Leonard C, Greene P, et al. Perspectives of VA primary care clinicians toward electronic consultation-related workload burden. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2018104. Published 2020 Oct 1. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.18104

16. Deeds SA, Dowdell KJ, Chew LD, Ackerman SL. Implementing an opt-in eConsult program at seven academic medical centers: a qualitative analysis of primary care provider experiences. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(8):1427-1433. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05067-7

17. Rodriguez KL, Burkitt KH, Bayliss NK, et al. Veteran, primary care provider, and specialist satisfaction with electronic consultation. JMIR Med Inform. 2015;3(1):e5. Published 2015 Jan 14. doi:10.2196/medinform.3725

18. Gupte G, Vimalananda V, Simon SR, DeVito K, Clark J, Orlander JD. Disruptive innovation: implementation of electronic consultations in a Veterans Affairs Health Care System. JMIR Med Inform. 2016;4(1):e6. Published 2016 Feb 12. doi:10.2196/medinform.4801

19. Feldstein AC, Glasgow RE. A practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) for integrating research findings into practice. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(4):228-243. doi:10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34030-6

20. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Sage Publications; 2002.

21. Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758-1772. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x

22. Kim EJ, Orlander JD, Afable M, et al. Cardiology electronic consultation (e-consult) use by primary care providers at VA medical centres in New England. J Telemed Telecare. 2019;25(6):370-377. doi:10.1177/1357633X18774468

Cognitive Biases Influence Decision-Making Regarding Postacute Care in a Skilled Nursing Facility

The combination of decreasing hospital lengths of stay and increasing age and comorbidity of the United States population is a principal driver of the increased use of postacute care in the US.1-3 Postacute care refers to care in long-term acute care hospitals, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), and care provided by home health agencies after an acute hospitalization. In 2016, 43% of Medicare beneficiaries received postacute care after hospital discharge at the cost of $60 billion annually; nearly half of these received care in an SNF.4 Increasing recognition of the significant cost and poor outcomes of postacute care led to payment reforms, such as bundled payments, that incentivized less expensive forms of postacute care and improvements in outcomes.5-9 Early evaluations suggested that hospitals are sensitive to these reforms and responded by significantly decreasing SNF utilization.10,11 It remains unclear whether this was safe and effective.

In this context, increased attention to how hospital clinicians and hospitalized patients decide whether to use postacute care (and what form to use) is appropriate since the effect of payment reforms could negatively impact vulnerable populations of older adults without adequate protection.12 Suboptimal decision-making can drive both overuse and inappropriate underuse of this expensive medical resource. Initial evidence suggests that patients and clinicians are poorly equipped to make high-quality decisions about postacute care, with significant deficits in both the decision-making process and content.13-16 While these gaps are important to address, they may only be part of the problem. The fields of cognitive psychology and behavioral economics have revealed new insights into decision-making, demonstrating that people deviate from rational decision-making in predictable ways, termed decision heuristics, or cognitive biases.17 This growing field of research suggests heuristics or biases play important roles in decision-making and determining behavior, particularly in situations where there may be little information provided and the patient is stressed, tired, and ill—precisely like deciding on postacute care.18 However, it is currently unknown whether cognitive biases are at play when making hospital discharge decisions.

We sought to identify the most salient heuristics or cognitive biases patients may utilize when making decisions about postacute care at the end of their hospitalization and ways clinicians may contribute to these biases. The overall goal was to derive insights for improving postacute care decision-making.

METHODS

Study Design

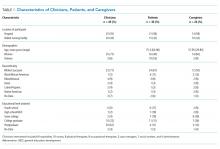

We conducted a secondary analysis on interviews with hospital and SNF clinicians as well as patients and their caregivers who were either leaving the hospital for an SNF or newly arrived in an SNF from the hospital to understand if cognitive biases were present and how they manifested themselves in a real-world clinical context.19 These interviews were part of a larger qualitative study that sought to understand how clinicians, patients, and their caregivers made decisions about postacute care, particularly related to SNFs.13,14 This study represents the analysis of all our interviews, specifically examining decision-making bias. Participating sites, clinical roles, and both patient and caregiver characteristics (Table 1) in our cohort have been previously described.13,14

Analysis

We used a team-based approach to framework analysis, which has been used in other decision-making studies14, including those measuring cognitive bias.20 A limitation in cognitive bias research is the lack of a standardized list or categorization of cognitive biases. We reviewed prior systematic17,21 and narrative reviews18,22, as well as prior studies describing examples of cognitive biases playing a role in decision-making about therapy20 to construct a list of possible cognitive biases to evaluate and narrow these a priori to potential biases relevant to the decision about postacute care based on our prior work (Table 2).

We applied this framework to analyze transcripts through an iterative process of deductive coding and reviewing across four reviewers (ML, RA, AL, CL) and a hospitalist physician with expertise leading qualitative studies (REB).

Intercoder consensus was built through team discussion by resolving points of disagreement.23 Consistency of coding was regularly checked by having more than one investigator code individual manuscripts and comparing coding, and discrepancies were resolved through team discussion. We triangulated the data (shared our preliminary results) using a larger study team, including an expert in behavioral economics (SRG), physicians at study sites (EC, RA), and an anthropologist with expertise in qualitative methods (CL). We did this to ensure credibility (to what extent the findings are credible or believable) and confirmability of findings (ensuring the findings are based on participant narratives rather than researcher biases).

RESULTS

We reviewed a total of 105 interviews with 25 hospital clinicians, 20 SNF clinicians, 21 patients and 14 caregivers in the hospital, and 15 patients and 10 caregivers in the SNF setting (Table 1). We found authority bias/halo effect; default/status quo bias, anchoring bias, and framing was commonly present in decision-making about postacute care in a SNF, whereas there were few if any examples of ambiguity aversion, availability heuristic, confirmation bias, optimism bias, or false consensus effect (Table 2).

Authority Bias/Halo Effect

While most patients deferred to their inpatient teams when it came to decision-making, this effect seemed to differ across VA and non-VA settings. Veterans expressed a higher degree of potential authority bias regarding the VA as an institution, whereas older adults in non-VA settings saw physicians as the authority figure making decisions in their best interests.

Veterans expressed confidence in the VA regarding both whether to go to a SNF and where to go:

“The VA wouldn’t license [an SNF] if they didn’t have a good reputation for care, cleanliness, things of that nature” (Veteran, VA CLC)

“I just knew the VA would have my best interests at heart” (Veteran, VA CLC)

Their caregivers expressed similar confidence:

“I’m not gonna decide [on whether the patient they care for goes to postacute care], like I told you, that’s totally up to the VA. I have trust and faith in them…so wherever they send him, that’s where he’s going” (Caregiver, VA hospital)

In some cases, this perspective was closer to the halo effect: a positive experience with the care provider or the care team led the decision-makers to believe that their recommendations about postacute care would be similarly positive.

“I think we were very trusting in the sense that whatever happened the last time around, he survived it…they took care of him…he got back home, and he started his life again, you know, so why would we question what they’re telling us to do? (Caregiver, VA hospital)

In contrast to Veterans, non-Veteran patients seemed to experience authority bias when it came to the inpatient team.

“Well, I’d like to know more about the PTs [Physical Therapists] there, but I assume since they were recommended, they will be good.” (Patient, University hospital)

This perspective was especially apparent when it came to physicians:

“The level of trust that they [patients] put in their doctor is gonna outweigh what anyone else would say.” (Clinical liaison, SNF)

“[In response to a question about influences on the decision to go to rehab] I don’t…that’s not my decision to make, that’s the doctor’s decision.” (Patient, University hospital)

“They said so…[the doctor] said I needed to go to rehab, so I guess I do because it’s the doctor’s decision.” (Patient, University hospital)

Default/Status quo Bias

In a related way, patients and caregivers with exposure to a SNF seemed to default to the same SNF with which they had previous experience. This bias seems to be primarily related to knowing what to expect.

“He thinks it’s [a particular SNF] the right place for him now…he was there before and he knew, again, it was the right place for him to be” (Caregiver, VA hospital)

“It’s the only one I’ve ever been in…but they have a lot of activities; you have a lot of freedom, staff was good” (Patient, VA hospital)

“I’ve been [to this SNF] before and I kind of know what the program involves…so it was kind of like going home, not, going home is the wrong way to put it…I mean coming here is like something I know, you know, I didn’t need anybody to explain it to me.” (Patient, VA hospital)

“Anybody that’s been to [SNF], that would be their choice to go back to, and I guess I must’ve liked it that first time because I asked to go back again.” (Patient, University hospital)

Anchoring Bias

While anchoring bias was less frequent, it came up in two domains: first, related to costs of care, and second, related to facility characteristics. Costs came up most frequently for Veterans who preferred to move their care to the VA for cost reasons, which appeared in these cases to overshadow other considerations:

“I kept emphasizing that the VA could do all the same things at a lot more reasonable price. The whole purpose of having the VA is for the Veteran, so that…we can get the healthcare that we need at a more reasonable [sic] or a reasonable price.” (Veteran, CLC)

“I think the CLC [VA SNF] is going to take care of her probably the same way any other facility of its type would, unless she were in a private facility, but you know, that costs a lot more money.” (Caregiver, VA hospital)

Patients occasionally had striking responses to particular characteristics of SNFs, regardless of whether this was a central feature or related to their rehabilitation:

“The social worker comes and talks to me about the nursing home where cats are running around, you know, to infect my leg or spin their little cat hairs into my lungs and make my asthma worse…I’m going to have to beg the nurses or the aides or the family or somebody to clean the cat…” (Veteran, VA hospital)

Framing

Framing was the strongest theme among clinician interviews in our sample. Clinicians most frequently described the SNF as a place where patients could recover function (a positive frame), explaining risks (eg, rehospitalization) associated with alternative postacute care options besides the SNF in great detail.

“Aside from explaining the benefits of going and…having that 24-hour care, having the therapies provided to them [the patients], talking about them getting stronger, phrasing it in such a way that patients sometimes are more agreeable, like not calling it a skilled nursing facility, calling it a rehab you know, for them to get physically stronger so they can be the most independent that they can once they do go home, and also explaining … we think that this would be the best plan to prevent them from coming back to the hospital, so those are some of the things that we’ll mention to patients to try and educate them and get them to be agreeable for placement.” (Social worker, University hospital)

Clinicians avoided negative associations with “nursing home” (even though all SNFs are nursing homes) and tended to use more positive frames such as “rehabilitation facility.”

“Use the word rehab….we definitely use the word rehab, to get more therapy, to go home; it’s not a, we really emphasize it’s not a nursing home, it’s not to go to stay forever.” (Physical therapist, safety-net hospital)

Clinicians used a frame of “safety” when discussing the SNF and used a frame of “risk” when discussing alternative postacute care options such as returning home. We did not find examples of clinicians discussing similar risks in going to a SNF even for risks, such as falling, which exist in both settings.

“I’ve talked to them primarily on an avenue of safety because I think people want and they value independence, they value making sure they can get home, but you know, a lot of the times they understand safety is, it can be a concern and outlining that our goal is to make sure that they’re safe and they stay home, and I tend to broach the subject saying that our therapists believe that they might not be safe at home in the moment, but they have potential goals to be safe later on if we continue therapy. I really highlight safety being the major driver of our discussion.” (Physician, VA hospital)

In some cases, framing was so overt that other risk-mitigating options (eg, home healthcare) are not discussed.

“I definitely tend to explain the ideal first. I’m not going to bring up home care when we really think somebody should go to rehab, however, once people say I don’t want to do that, I’m not going, then that’s when I’m like OK, well, let’s talk to the doctors, but we can see about other supports in the home.” (Social worker, VA hospital)

DISCUSSION

In a large sample of patients and their caregivers, as well as multidisciplinary clinicians at three different hospitals and three SNFs, we found authority bias/halo effect and framing biases were most common and seemed most impactful. Default/status quo bias and anchoring bias were also present in decision-making about a SNF. The combination of authority bias/halo effect and framing biases could synergistically interact to augment the likelihood of patients accepting a SNF for postacute care. Patients who had been to a SNF before seemed more likely to choose the SNF they had experienced previously even if they had no other postacute care experiences, and could be highly influenced by isolated characteristics of that facility (such as the physical environment or cost of care).

It is important to mention that cognitive biases do not necessarily have a negative impact: indeed, as Kahneman and Tversky point out, these are useful heuristics from “fast” thinking that are often effective.24 For example, clinicians may be trying to act in the best interests of the patient when framing the decision in terms of regaining function and averting loss of safety and independence. However, the evidence base regarding the outcomes of an SNF versus other postacute options is not robust, and this decision-making is complex. While this decision was most commonly framed in terms of rehabilitation and returning home, the fact that only about half of patients have returned to the community by 100 days4 was not discussed in any interview. In fact, initial evidence suggests replacing the SNF with home healthcare in patients with hip and knee arthroplasty may reduce costs without worsening clinical outcomes.6 However, across a broader population, SNFs significantly reduce 30-day readmissions when directly compared with home healthcare, but other clinical outcomes are similar.25 This evidence suggests that the “right” postacute care option for an individual patient is not clear, highlighting a key role biases may play in decision-making. Further, the nebulous concept of “safety” could introduce potential disparities related to social determinants of health.12 The observed inclination to accept an SNF with which the individual had prior experience may be influenced by the acceptability of this choice because of personal factors or prior research, even if it also represents a bias by limiting the consideration of current alternatives.

Our findings complement those of others in the literature which have also identified profound gaps in discharge decision-making among patients and clinicians,13-16,26-31 though to our knowledge the role of cognitive biases in these decisions has not been explored. This study also addresses gaps in the cognitive bias literature, including the need for real-world data rather than hypothetical vignettes,17 and evaluation of treatment and management decisions rather than diagnoses, which have been more commonly studied.21

These findings have implications for both individual clinicians and healthcare institutions. In the immediate term, these findings may serve as a call to discharging clinicians to modulate language and “debias” their conversations with patients about care after discharge.18,22 Shared decision-making requires an informed choice by patients based on their goals and values; framing a decision in a way that puts the clinician’s goals or values (eg, safety) ahead of patient values (eg, independence and autonomy) or limits disclosure (eg, a “rehab” is a nursing home) in the hope of influencing choice may be more consistent with framing bias and less with shared decision-making.14 Although controversy exists about the best way to “debias” oneself,32 self-awareness of bias is increasingly recognized across healthcare venues as critical to improving care for vulnerable populations.33 The use of data rather than vignettes may be a useful debiasing strategy, although the limitations of currently available data (eg, capturing nursing home quality) are increasingly recognized.34 From a policy and health system perspective, cognitive biases should be integrated into the development of decision aids to facilitate informed, shared, and high-quality decision-making that incorporates patient values, and perhaps “nudges” from behavioral economics to assist patients in choosing the right postdischarge care for them. Such nudges use principles of framing to influence care without restricting choice.35 As the science informing best practice regarding postacute care improves, identifying the “right” postdischarge care may become easier and recommendations more evidence-based.36

Strengths of the study include a large, diverse sample of patients, caregivers, and clinicians in both the hospital and SNF setting. Also, we used a team-based analysis with an experienced team and a deep knowledge of the data, including triangulation with clinicians to verify results. However, all hospitals and SNFs were located in a single metropolitan area, and responses may vary by region or population density. All three hospitals have housestaff teaching programs, and at the time of the interviews all three community SNFs were “five-star” facilities on the Nursing Home Compare website; results may be different at community hospitals or other SNFs. Hospitalists were the only physician group sampled in the hospital as they provide the majority of inpatient care to older adults; geriatricians, in particular, may have had different perspectives. Since we intended to explore whether cognitive biases were present overall, we did not evaluate whether cognitive biases differed by role or subgroup (by clinician type, patient, or caregiver), but this may be a promising area to explore in future work. Many cognitive biases have been described, and there are likely additional biases we did not identify. To confirm the generalizability of these findings, they should be studied in a larger, more generalizable sample of respondents in future work.

Cognitive biases play an important role in patient decision-making about postacute care, particularly regarding SNF care. As postacute care undergoes a transformation spurred by payment reforms, it is more important than ever to ensure that patients understand their choices at hospital discharge and can make a high-quality decision consistent with their goals.

1. Burke RE, Juarez-Colunga E, Levy C, Prochazka AV, Coleman EA, Ginde AA. Rise of post-acute care facilities as a discharge destination of US hospitalizations. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):295-296. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6383.

2. Burke RE, Juarez-Colunga E, Levy C, Prochazka AV, Coleman EA, Ginde AA. Patient and hospitalization characteristics associated with increased postacute care facility discharges from US hospitals. Med Care. 2015;53(6):492-500. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000359.

3. Werner RM, Konetzka RT. Trends in post-acute care use among medicare beneficiaries: 2000 to 2015. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1616-1617. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.2408.

4. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission June 2018 Report to Congress. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/jun18_ch5_medpacreport_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed November 9, 2018.

5. Burke RE, Cumbler E, Coleman EA, Levy C. Post-acute care reform: implications and opportunities for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(1):46-51. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2673.