User login

Is It Time to Revisit Pediatric Postdischarge Home Visits for Readmissions Reduction?

Despite concerted national efforts to decrease pediatric readmissions, recent data suggest that preventable and all-cause readmission rates of hospitalized children remain unchanged.1 Because some readmissions may be caused by inadequate postdischarge follow-up, nurse (RN) home visits offer the prospect of addressing unresolved clinical issues after discharge and ameliorating patient and family concerns that may otherwise prompt re-presentation for acute care. Yet a recent trial of this approach, the Hospital to Home Outcomes (H2O) trial,2 found the opposite to be true: participants receiving home nurse visits had higher reutilization rates than did participants in the control group. This raises interesting questions: Is it time to revisit postdischarge outreach as an intervention to reduce pediatric readmissions—and even pediatric readmissions altogether as an outcome metric?

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Riddle et al3 explored the perspectives of key stakeholders to understand the factors driving increased reutilization after postdischarge home visits in the H2O trial and obtained feedback for improving potential interventions. The investigators used a qualitative approach that consisted of telephone interviews with 33 parents who were enrolled in the H2O trial and in-person focus groups with 10 home care RNs involved in the trial, 12 hospital medicine physicians, and 7 primary care physicians (PCPs). Inductive thematic analysis was used to analyze responses to open-ended questions through a rigorous, iterative and multidisciplinary process. Key themes elicited from stakeholders included questions about the clinical appropriateness of reutilization episodes; the influence of insufficiently contextualized “red flag,” or warning sign, instructions given to parents in facilitating reutilization; the potential for hospital-employed home care nurses to inadvertently promote emergency department rather than PCP follow-up; and escalation of care exceeding that expected in a PCP office. Stakeholders suggested the intervention could be improved by enhancing postdischarge communication between home care RNs, hospital medicine physicians, and PCPs; tailoring home visits to specific clinical, patient, and family scenarios; and more clearly framing “red flags.”

We welcome the work of Riddle and colleagues in exposing the elements of home visits that may have led to increased utilization, and their proposed next steps to improve the intervention—enhancing contact with PCP offices and focusing interventions on specific populations—unquestionably have merit. We agree that this may be particularly true in children with medical complexity (a population that was excluded from this study), who have unique discharge needs and account for over half of pediatric readmissions.4 However, we suggest that the instinct to refine the design of the study intervention should be weighed against alternative possibilities: that postdischarge interventions are simply not effective in decreasing reutilization or, at the very least, that the findings of the H2O trial should not lead us to invest the resources required to further discern the efficacy of postdischarge interventions.

This counter-intuitive possibility is only compounded by the fact that reutilization rates were not improved in the study group’s H2O II trial, a follow-up study that focused on postdischarge nurse telephone calls as the intervention of interest5; and indeed, the results of these two, well-designed negative trials have been previously cited to propose postdischarge nurse contact as a potential target of deimplementation efforts.6 In the pediatric population, in which caregivers rather than patients themselves are generally responsible for seeking out care, postdischarge outreach may inevitably escalate concerning findings that will result in reutilization. Instead, perhaps the H2O study findings should prompt a broader exploration for alternative solutions to pediatric readmission reduction. One such solution could build on the finding by Riddle et al that stakeholders perceive ambiguity in whether discharging physicians, or rather PCPs, have ownership of clinical issues after discharge. Rather than asking visiting RNs to triangulate between inpatient and outpatient physicians, developing systems to directly integrate PCPs in the hospital discharge process for select patients—for instance, through leveraging the rapid expansion of telemedicine services during the COVID-19 crisis—may promote shared understanding of a patient’s illness trajectory and follow-up needs.

Importantly, the authors also noted that despite the findings of increased reutilization, parents who received home visits expressed their wishes to receive home visits in the future. While not a central finding of the study, this validates a hypothesis expressed in prior work by the H2O study group: “Hospital quality readmission metrics may not be well aligned with family desires for improved postdischarge transitions.”5 Given that efforts to reduce pediatric readmission have been largely unsuccessful and that readmission events are relatively uncommon in the general pediatric population,4 the parental wishes resonate with existing calls in the literature to consider looking beyond readmissions reduction in isolation as a quality metric. In contrast to the increasing presence of hospital reimbursement penalties among state Medicaid agencies for readmissions, a shift in focus toward outcome measures that are patient- and family-centered is imperative.1,7 If home visits are not ultimately a solution to pediatric reutilization reduction, they may nonetheless still enable families to effectively manage the concerns that families endorse following discharge, including medication safety and social hardships.8

In summary, Riddle et al not only provided important context for the unexpected outcome of a well-designed randomized clinical trial but also provided a rich source of qualitative data that furthers our understanding of a child’s discharge home from the hospital through the perspective of multiple stakeholders. While the authors offer well-reasoned next steps in narrowing the intervention population of interest and enhancing connections of families with PCP care, it may be time to broadly revisit postdischarge interventions and outcomes to identify new approaches and redefine quality measures for hospital-to-home transitions of children and their families.

1. Auger KA, Harris JM, Gay JC, et al. Progress (?) toward reducing pediatric readmissions. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):618-621. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3210

2. Auger KA, Simmons JM, Tubbs-Cooley HL, et al. Postdischarge nurse home visits and reuse: the hospital to home outcomes (H2O) trial. Pediatrics. 2018;142(1):e20173919. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0092

3. Riddle SW, Sherman SN, Moore MJ, et al. A qualitative study of increased pediatric reutilization after a postdischarge home nurse visit. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:518-525. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3370

4. Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372-380. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.188351

5. Auger KA, Shah SS, Tubbs-Cooley HL, et al. Effects of a 1-time nurse-led telephone call after pediatric discharge: the H2O II randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(9):e181482. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1482

6. Bonafide CP, Keren R. Negative studies and the science of deimplementation. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(9):807-809. https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2077

7. Leyenaar JK, Lagu T, Lindenauer PK. Are pediatric readmission reduction efforts falling flat? J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):644-645. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3269

8. Tubbs-Cooley HL, Riddle SW, Gold JM, et al. Paediatric clinical and social concerns identified by home visit nurses in the immediate postdischarge period. J Adv Nurs. 2020;76(6):1394-1403. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14341

Despite concerted national efforts to decrease pediatric readmissions, recent data suggest that preventable and all-cause readmission rates of hospitalized children remain unchanged.1 Because some readmissions may be caused by inadequate postdischarge follow-up, nurse (RN) home visits offer the prospect of addressing unresolved clinical issues after discharge and ameliorating patient and family concerns that may otherwise prompt re-presentation for acute care. Yet a recent trial of this approach, the Hospital to Home Outcomes (H2O) trial,2 found the opposite to be true: participants receiving home nurse visits had higher reutilization rates than did participants in the control group. This raises interesting questions: Is it time to revisit postdischarge outreach as an intervention to reduce pediatric readmissions—and even pediatric readmissions altogether as an outcome metric?

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Riddle et al3 explored the perspectives of key stakeholders to understand the factors driving increased reutilization after postdischarge home visits in the H2O trial and obtained feedback for improving potential interventions. The investigators used a qualitative approach that consisted of telephone interviews with 33 parents who were enrolled in the H2O trial and in-person focus groups with 10 home care RNs involved in the trial, 12 hospital medicine physicians, and 7 primary care physicians (PCPs). Inductive thematic analysis was used to analyze responses to open-ended questions through a rigorous, iterative and multidisciplinary process. Key themes elicited from stakeholders included questions about the clinical appropriateness of reutilization episodes; the influence of insufficiently contextualized “red flag,” or warning sign, instructions given to parents in facilitating reutilization; the potential for hospital-employed home care nurses to inadvertently promote emergency department rather than PCP follow-up; and escalation of care exceeding that expected in a PCP office. Stakeholders suggested the intervention could be improved by enhancing postdischarge communication between home care RNs, hospital medicine physicians, and PCPs; tailoring home visits to specific clinical, patient, and family scenarios; and more clearly framing “red flags.”

We welcome the work of Riddle and colleagues in exposing the elements of home visits that may have led to increased utilization, and their proposed next steps to improve the intervention—enhancing contact with PCP offices and focusing interventions on specific populations—unquestionably have merit. We agree that this may be particularly true in children with medical complexity (a population that was excluded from this study), who have unique discharge needs and account for over half of pediatric readmissions.4 However, we suggest that the instinct to refine the design of the study intervention should be weighed against alternative possibilities: that postdischarge interventions are simply not effective in decreasing reutilization or, at the very least, that the findings of the H2O trial should not lead us to invest the resources required to further discern the efficacy of postdischarge interventions.

This counter-intuitive possibility is only compounded by the fact that reutilization rates were not improved in the study group’s H2O II trial, a follow-up study that focused on postdischarge nurse telephone calls as the intervention of interest5; and indeed, the results of these two, well-designed negative trials have been previously cited to propose postdischarge nurse contact as a potential target of deimplementation efforts.6 In the pediatric population, in which caregivers rather than patients themselves are generally responsible for seeking out care, postdischarge outreach may inevitably escalate concerning findings that will result in reutilization. Instead, perhaps the H2O study findings should prompt a broader exploration for alternative solutions to pediatric readmission reduction. One such solution could build on the finding by Riddle et al that stakeholders perceive ambiguity in whether discharging physicians, or rather PCPs, have ownership of clinical issues after discharge. Rather than asking visiting RNs to triangulate between inpatient and outpatient physicians, developing systems to directly integrate PCPs in the hospital discharge process for select patients—for instance, through leveraging the rapid expansion of telemedicine services during the COVID-19 crisis—may promote shared understanding of a patient’s illness trajectory and follow-up needs.

Importantly, the authors also noted that despite the findings of increased reutilization, parents who received home visits expressed their wishes to receive home visits in the future. While not a central finding of the study, this validates a hypothesis expressed in prior work by the H2O study group: “Hospital quality readmission metrics may not be well aligned with family desires for improved postdischarge transitions.”5 Given that efforts to reduce pediatric readmission have been largely unsuccessful and that readmission events are relatively uncommon in the general pediatric population,4 the parental wishes resonate with existing calls in the literature to consider looking beyond readmissions reduction in isolation as a quality metric. In contrast to the increasing presence of hospital reimbursement penalties among state Medicaid agencies for readmissions, a shift in focus toward outcome measures that are patient- and family-centered is imperative.1,7 If home visits are not ultimately a solution to pediatric reutilization reduction, they may nonetheless still enable families to effectively manage the concerns that families endorse following discharge, including medication safety and social hardships.8

In summary, Riddle et al not only provided important context for the unexpected outcome of a well-designed randomized clinical trial but also provided a rich source of qualitative data that furthers our understanding of a child’s discharge home from the hospital through the perspective of multiple stakeholders. While the authors offer well-reasoned next steps in narrowing the intervention population of interest and enhancing connections of families with PCP care, it may be time to broadly revisit postdischarge interventions and outcomes to identify new approaches and redefine quality measures for hospital-to-home transitions of children and their families.

Despite concerted national efforts to decrease pediatric readmissions, recent data suggest that preventable and all-cause readmission rates of hospitalized children remain unchanged.1 Because some readmissions may be caused by inadequate postdischarge follow-up, nurse (RN) home visits offer the prospect of addressing unresolved clinical issues after discharge and ameliorating patient and family concerns that may otherwise prompt re-presentation for acute care. Yet a recent trial of this approach, the Hospital to Home Outcomes (H2O) trial,2 found the opposite to be true: participants receiving home nurse visits had higher reutilization rates than did participants in the control group. This raises interesting questions: Is it time to revisit postdischarge outreach as an intervention to reduce pediatric readmissions—and even pediatric readmissions altogether as an outcome metric?

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Riddle et al3 explored the perspectives of key stakeholders to understand the factors driving increased reutilization after postdischarge home visits in the H2O trial and obtained feedback for improving potential interventions. The investigators used a qualitative approach that consisted of telephone interviews with 33 parents who were enrolled in the H2O trial and in-person focus groups with 10 home care RNs involved in the trial, 12 hospital medicine physicians, and 7 primary care physicians (PCPs). Inductive thematic analysis was used to analyze responses to open-ended questions through a rigorous, iterative and multidisciplinary process. Key themes elicited from stakeholders included questions about the clinical appropriateness of reutilization episodes; the influence of insufficiently contextualized “red flag,” or warning sign, instructions given to parents in facilitating reutilization; the potential for hospital-employed home care nurses to inadvertently promote emergency department rather than PCP follow-up; and escalation of care exceeding that expected in a PCP office. Stakeholders suggested the intervention could be improved by enhancing postdischarge communication between home care RNs, hospital medicine physicians, and PCPs; tailoring home visits to specific clinical, patient, and family scenarios; and more clearly framing “red flags.”

We welcome the work of Riddle and colleagues in exposing the elements of home visits that may have led to increased utilization, and their proposed next steps to improve the intervention—enhancing contact with PCP offices and focusing interventions on specific populations—unquestionably have merit. We agree that this may be particularly true in children with medical complexity (a population that was excluded from this study), who have unique discharge needs and account for over half of pediatric readmissions.4 However, we suggest that the instinct to refine the design of the study intervention should be weighed against alternative possibilities: that postdischarge interventions are simply not effective in decreasing reutilization or, at the very least, that the findings of the H2O trial should not lead us to invest the resources required to further discern the efficacy of postdischarge interventions.

This counter-intuitive possibility is only compounded by the fact that reutilization rates were not improved in the study group’s H2O II trial, a follow-up study that focused on postdischarge nurse telephone calls as the intervention of interest5; and indeed, the results of these two, well-designed negative trials have been previously cited to propose postdischarge nurse contact as a potential target of deimplementation efforts.6 In the pediatric population, in which caregivers rather than patients themselves are generally responsible for seeking out care, postdischarge outreach may inevitably escalate concerning findings that will result in reutilization. Instead, perhaps the H2O study findings should prompt a broader exploration for alternative solutions to pediatric readmission reduction. One such solution could build on the finding by Riddle et al that stakeholders perceive ambiguity in whether discharging physicians, or rather PCPs, have ownership of clinical issues after discharge. Rather than asking visiting RNs to triangulate between inpatient and outpatient physicians, developing systems to directly integrate PCPs in the hospital discharge process for select patients—for instance, through leveraging the rapid expansion of telemedicine services during the COVID-19 crisis—may promote shared understanding of a patient’s illness trajectory and follow-up needs.

Importantly, the authors also noted that despite the findings of increased reutilization, parents who received home visits expressed their wishes to receive home visits in the future. While not a central finding of the study, this validates a hypothesis expressed in prior work by the H2O study group: “Hospital quality readmission metrics may not be well aligned with family desires for improved postdischarge transitions.”5 Given that efforts to reduce pediatric readmission have been largely unsuccessful and that readmission events are relatively uncommon in the general pediatric population,4 the parental wishes resonate with existing calls in the literature to consider looking beyond readmissions reduction in isolation as a quality metric. In contrast to the increasing presence of hospital reimbursement penalties among state Medicaid agencies for readmissions, a shift in focus toward outcome measures that are patient- and family-centered is imperative.1,7 If home visits are not ultimately a solution to pediatric reutilization reduction, they may nonetheless still enable families to effectively manage the concerns that families endorse following discharge, including medication safety and social hardships.8

In summary, Riddle et al not only provided important context for the unexpected outcome of a well-designed randomized clinical trial but also provided a rich source of qualitative data that furthers our understanding of a child’s discharge home from the hospital through the perspective of multiple stakeholders. While the authors offer well-reasoned next steps in narrowing the intervention population of interest and enhancing connections of families with PCP care, it may be time to broadly revisit postdischarge interventions and outcomes to identify new approaches and redefine quality measures for hospital-to-home transitions of children and their families.

1. Auger KA, Harris JM, Gay JC, et al. Progress (?) toward reducing pediatric readmissions. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):618-621. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3210

2. Auger KA, Simmons JM, Tubbs-Cooley HL, et al. Postdischarge nurse home visits and reuse: the hospital to home outcomes (H2O) trial. Pediatrics. 2018;142(1):e20173919. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0092

3. Riddle SW, Sherman SN, Moore MJ, et al. A qualitative study of increased pediatric reutilization after a postdischarge home nurse visit. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:518-525. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3370

4. Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372-380. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.188351

5. Auger KA, Shah SS, Tubbs-Cooley HL, et al. Effects of a 1-time nurse-led telephone call after pediatric discharge: the H2O II randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(9):e181482. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1482

6. Bonafide CP, Keren R. Negative studies and the science of deimplementation. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(9):807-809. https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2077

7. Leyenaar JK, Lagu T, Lindenauer PK. Are pediatric readmission reduction efforts falling flat? J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):644-645. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3269

8. Tubbs-Cooley HL, Riddle SW, Gold JM, et al. Paediatric clinical and social concerns identified by home visit nurses in the immediate postdischarge period. J Adv Nurs. 2020;76(6):1394-1403. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14341

1. Auger KA, Harris JM, Gay JC, et al. Progress (?) toward reducing pediatric readmissions. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):618-621. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3210

2. Auger KA, Simmons JM, Tubbs-Cooley HL, et al. Postdischarge nurse home visits and reuse: the hospital to home outcomes (H2O) trial. Pediatrics. 2018;142(1):e20173919. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0092

3. Riddle SW, Sherman SN, Moore MJ, et al. A qualitative study of increased pediatric reutilization after a postdischarge home nurse visit. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:518-525. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3370

4. Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372-380. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.188351

5. Auger KA, Shah SS, Tubbs-Cooley HL, et al. Effects of a 1-time nurse-led telephone call after pediatric discharge: the H2O II randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(9):e181482. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1482

6. Bonafide CP, Keren R. Negative studies and the science of deimplementation. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(9):807-809. https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2077

7. Leyenaar JK, Lagu T, Lindenauer PK. Are pediatric readmission reduction efforts falling flat? J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):644-645. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3269

8. Tubbs-Cooley HL, Riddle SW, Gold JM, et al. Paediatric clinical and social concerns identified by home visit nurses in the immediate postdischarge period. J Adv Nurs. 2020;76(6):1394-1403. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14341

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Leadership & Professional Development: Having a Backup Plan

“Confidence comes from being prepared.”

—John Wooden

Hospital medicine is a field that requires a constant state of readiness and flexibility. With respect to patient care, constant preparedness is required because conditions change. This necessitates always having a backup plan, or Plan B. For example, your patient with a gastrointestinal (GI) bleed should have two large-bore intravenous (IV) catheters and packed red blood cells (RBCs) typed and crossed. If the patient becomes unstable, the response is not just doing more of the same (IV fluids and proton pump inhibitors); the focus shifts to your Plan B: call GI, transfuse blood, transfer the patient to the intensive care unit.

In contrast to clinical scenarios, there is often a lack of readiness to deal with rapid changes in workflow. Without a plan, efficiency decreases, stress levels rise, and both patients and providers alike suffer the consequences. Patients spending extended periods of time in the Emergency Department (ED) receive less timely services and often don’t benefit from the expertise that they would receive in inpatient units.1 This is particularly true in an era in which many hospitals are experiencing higher overall volume and surges are more common.

Ideally, readiness should manifest as the ability to adapt to changes at the individual, hospitalist team, and leadership levels. Having a Plan B in the practice of hospital medicine is a focused exercise for anticipating future problems and addressing them prospectively. When thinking about a Plan B, the following are some steps to consider:

1. Identify Triggers. In the earlier example of the GI bleed, our triggers for Plan B would be a change in vitals or a brisk drop in hemoglobin. Regarding hospital workflow, the triggers might include low service or bed capacity or a decreased number of expected discharges for the day. Perhaps a high ED census or increased surgical volume will trigger your plan to handle the surge.

2. Define Your Response. At both an individual and service level, there are steps you might consider in your Plan B. On teaching services, this might mean prioritizing rounding on patients that you’re expecting to discharge so they’re able to leave the hospital sooner. For patients on observation status who are boarding in the ED for extended periods, there might be opportunities to safely discharge them with follow-up or even complete their work-up in the ED. There may be circumstances in which providers should exceed the usual service capacity and conditions in which it is truly unsafe to exceed that limit. If there are resources available to increase staffing, consider how to best utilize them.

3. Engage Broadly and Proactively. It is very difficult to execute a Plan B (or frankly a Plan A) without buy-in from your stakeholders. This starts with the rank and file, those on your team who will actually execute the plan. The leadership of your department or division, the ED, and nursing will also likely need to provide input. If financial resources for flexing up staff are part of your plan, the hospital administration might need to weigh in. It is best to engage stakeholders early on rather than during a crisis.

4. Constant Assessment and Improvement. Going back to our example of our patient with a GI bleed, you’re constantly reevaluating your patient to determine if your Plan B is working. Similarly, you should collect data and reassess the effectiveness of your plan. There are likely opportunities to improve it.

There are no textbook chapters or medical school lectures to prepare hospitalists for these real-world crises. Yet failing to have a Plan B is to surrender a tremendous amount of personal control in the face of chaos, to jeopardize patient care, and to ultimately forgo the opportunity to achieve a level of mastery in a field predicated on readiness.

1. Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the United States Health System. Hospital-Based Emergency Care at the Breaking Point. Washington, District of Columbia: The National Academies Press; 2006.

“Confidence comes from being prepared.”

—John Wooden

Hospital medicine is a field that requires a constant state of readiness and flexibility. With respect to patient care, constant preparedness is required because conditions change. This necessitates always having a backup plan, or Plan B. For example, your patient with a gastrointestinal (GI) bleed should have two large-bore intravenous (IV) catheters and packed red blood cells (RBCs) typed and crossed. If the patient becomes unstable, the response is not just doing more of the same (IV fluids and proton pump inhibitors); the focus shifts to your Plan B: call GI, transfuse blood, transfer the patient to the intensive care unit.

In contrast to clinical scenarios, there is often a lack of readiness to deal with rapid changes in workflow. Without a plan, efficiency decreases, stress levels rise, and both patients and providers alike suffer the consequences. Patients spending extended periods of time in the Emergency Department (ED) receive less timely services and often don’t benefit from the expertise that they would receive in inpatient units.1 This is particularly true in an era in which many hospitals are experiencing higher overall volume and surges are more common.

Ideally, readiness should manifest as the ability to adapt to changes at the individual, hospitalist team, and leadership levels. Having a Plan B in the practice of hospital medicine is a focused exercise for anticipating future problems and addressing them prospectively. When thinking about a Plan B, the following are some steps to consider:

1. Identify Triggers. In the earlier example of the GI bleed, our triggers for Plan B would be a change in vitals or a brisk drop in hemoglobin. Regarding hospital workflow, the triggers might include low service or bed capacity or a decreased number of expected discharges for the day. Perhaps a high ED census or increased surgical volume will trigger your plan to handle the surge.

2. Define Your Response. At both an individual and service level, there are steps you might consider in your Plan B. On teaching services, this might mean prioritizing rounding on patients that you’re expecting to discharge so they’re able to leave the hospital sooner. For patients on observation status who are boarding in the ED for extended periods, there might be opportunities to safely discharge them with follow-up or even complete their work-up in the ED. There may be circumstances in which providers should exceed the usual service capacity and conditions in which it is truly unsafe to exceed that limit. If there are resources available to increase staffing, consider how to best utilize them.

3. Engage Broadly and Proactively. It is very difficult to execute a Plan B (or frankly a Plan A) without buy-in from your stakeholders. This starts with the rank and file, those on your team who will actually execute the plan. The leadership of your department or division, the ED, and nursing will also likely need to provide input. If financial resources for flexing up staff are part of your plan, the hospital administration might need to weigh in. It is best to engage stakeholders early on rather than during a crisis.

4. Constant Assessment and Improvement. Going back to our example of our patient with a GI bleed, you’re constantly reevaluating your patient to determine if your Plan B is working. Similarly, you should collect data and reassess the effectiveness of your plan. There are likely opportunities to improve it.

There are no textbook chapters or medical school lectures to prepare hospitalists for these real-world crises. Yet failing to have a Plan B is to surrender a tremendous amount of personal control in the face of chaos, to jeopardize patient care, and to ultimately forgo the opportunity to achieve a level of mastery in a field predicated on readiness.

“Confidence comes from being prepared.”

—John Wooden

Hospital medicine is a field that requires a constant state of readiness and flexibility. With respect to patient care, constant preparedness is required because conditions change. This necessitates always having a backup plan, or Plan B. For example, your patient with a gastrointestinal (GI) bleed should have two large-bore intravenous (IV) catheters and packed red blood cells (RBCs) typed and crossed. If the patient becomes unstable, the response is not just doing more of the same (IV fluids and proton pump inhibitors); the focus shifts to your Plan B: call GI, transfuse blood, transfer the patient to the intensive care unit.

In contrast to clinical scenarios, there is often a lack of readiness to deal with rapid changes in workflow. Without a plan, efficiency decreases, stress levels rise, and both patients and providers alike suffer the consequences. Patients spending extended periods of time in the Emergency Department (ED) receive less timely services and often don’t benefit from the expertise that they would receive in inpatient units.1 This is particularly true in an era in which many hospitals are experiencing higher overall volume and surges are more common.

Ideally, readiness should manifest as the ability to adapt to changes at the individual, hospitalist team, and leadership levels. Having a Plan B in the practice of hospital medicine is a focused exercise for anticipating future problems and addressing them prospectively. When thinking about a Plan B, the following are some steps to consider:

1. Identify Triggers. In the earlier example of the GI bleed, our triggers for Plan B would be a change in vitals or a brisk drop in hemoglobin. Regarding hospital workflow, the triggers might include low service or bed capacity or a decreased number of expected discharges for the day. Perhaps a high ED census or increased surgical volume will trigger your plan to handle the surge.

2. Define Your Response. At both an individual and service level, there are steps you might consider in your Plan B. On teaching services, this might mean prioritizing rounding on patients that you’re expecting to discharge so they’re able to leave the hospital sooner. For patients on observation status who are boarding in the ED for extended periods, there might be opportunities to safely discharge them with follow-up or even complete their work-up in the ED. There may be circumstances in which providers should exceed the usual service capacity and conditions in which it is truly unsafe to exceed that limit. If there are resources available to increase staffing, consider how to best utilize them.

3. Engage Broadly and Proactively. It is very difficult to execute a Plan B (or frankly a Plan A) without buy-in from your stakeholders. This starts with the rank and file, those on your team who will actually execute the plan. The leadership of your department or division, the ED, and nursing will also likely need to provide input. If financial resources for flexing up staff are part of your plan, the hospital administration might need to weigh in. It is best to engage stakeholders early on rather than during a crisis.

4. Constant Assessment and Improvement. Going back to our example of our patient with a GI bleed, you’re constantly reevaluating your patient to determine if your Plan B is working. Similarly, you should collect data and reassess the effectiveness of your plan. There are likely opportunities to improve it.

There are no textbook chapters or medical school lectures to prepare hospitalists for these real-world crises. Yet failing to have a Plan B is to surrender a tremendous amount of personal control in the face of chaos, to jeopardize patient care, and to ultimately forgo the opportunity to achieve a level of mastery in a field predicated on readiness.

1. Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the United States Health System. Hospital-Based Emergency Care at the Breaking Point. Washington, District of Columbia: The National Academies Press; 2006.

1. Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the United States Health System. Hospital-Based Emergency Care at the Breaking Point. Washington, District of Columbia: The National Academies Press; 2006.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Quantifying the Risks of Hospitalization—Is It Really as Safe as We Believe?

Even though I could not remember her name, I remembered her story, and I would bet that my colleagues did as well. She was someone that we had all cared for at one time or another. She frequently presented to the hospital with chest pain or shortness of breath attributable to a combination of longstanding congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cocaine abuse. But most tragic of all, she was homeless, which meant that she was frequently hospitalized not only for medical complaints but also for a night’s shelter and a bite of food. Even though she often refused medical treatment and social workers’ efforts to stabilize her housing situation, the staff in the emergency room and observation unit all knew her by name and greeted her like an old friend. And then one day she stopped showing up to the hospital. Sitting in the emergency department (ED), I overheard that she was found outside of a storefront and had passed away. Saddened by her death, which was not unexpected given her medical issues, I still wondered if we had done right by her during the hundreds of times that she had come to our hospital. Clinicians at busy safety-net hospitals face these questions every day, and it would seem beyond doubt that our duty is to address both medical and nonmedical determinants of health of everyone that walks through our door. But is this in fact the right thing to do? Is it possible that we unwittingly expose these vulnerable patients to risks from hospitalization alone?

In this month’s Journal of Hospital Medicine, Sekijima et al. sought to quantify precisely the risks of hospitalization, particularly among the subset of patients whose “severity” of medical problems alone might not have warranted hospital admission, a scenario known colloquially as a “social” admission.1 In real time, an inhouse triage physician classified patients as being admitted with or without “definite medical acuity.” Investigators retrospectively identified adverse events and illness acuity using standardized instruments, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Global Trigger Tool and Emergency Severity Index, respectively. Despite the acknowledged differences in the patient population and the inherent subjectivity within the designation process, Sekijima et al. found no statistically significant difference in the percentage of admissions with an adverse event nor in the rate of adverse events per 1,000 patient days. Falls, oversedation/hypotension and code/arrest/rapid response activation were the most frequently encountered adverse events.

Delving deeper into the origin of admissions without definite medical acuity, the authors identified homelessness, lack of outpatient social support, substance use disorder, and lack of outpatient medical support as the most common reasons for “nonmedical” admissions. As healthcare providers, we recognize that these factors are generally long-term, chronic socioeconomic determinants of health. Despite our objective knowledge that we are limited in our ability to fix these problems on a short-term basis, the authors’ observations reflect our compulsion to try and help in any way possible. Patients admitted without definite medical acuity were more vulnerable and had higher rates of public insurance and housing insecurity. However, they were less acutely ill, as indicated by lower Emergency Severity Index scores. These factors were not associated with statistically significant differences in either 48-hour ED readmission or 30-day hospital readmission rates.

The process of appropriately triaging patients to an inpatient setting is challenging because of wide variability in both patients and ED providers. Hospitalists are increasingly recognized as an additional resource to assist in the triage process, as we are uniquely in a position to view the patient’s clinical presentation within the context of their anticipated clinical trajectory, promote effective utilization of inpatient bed availability, and anticipate potential barriers to discharge. Graduate medical education now identifies the triage process as a specific milestone within the transitions of care competency, as it requires mastery of interpersonal communication, professionalism, systems-based thinking, and patient-centered care.2 However, many institutions lack a dedicated faculty member to perform the triage role. Our institution recently examined the feasibility of instituting a daily “huddle” between the admitting hospitalist and the ED to facilitate interdepartmental communication to create care plans in patient triage and to promote patient throughput. Available admission beds are valuable commodities, and one challenge is that the ED makes disposition decisions without knowledge of the number of available beds in the hospital. The goal of the huddle was to quickly discuss all patients potentially requiring admission prior to the final disposition decision and to address any modifiable factors to potentially prevent a “social” admission with social work early in the day. Further work is in progress to determine if introducing flexibility within existing provider roles can improve the triage process in a measurable and efficient manner.

Many challenges remain as we balance the medical needs of patients with any potential social drivers that necessitate admission to the inpatient hospital setting. From an ED perspective, social support and community follow-up were “universally considered powerful influences on admission,” and other factors such as time of day, clinical volume, and the four-hour waiting time target also played a significant role in the decision to admit.3 Hunter et al. found that admissions with moderate to low acuity may be shorter or less costly,4 which presents an interesting question of cost-effectiveness as an avenue for further study. As clinicians, we are intuitively aware of the subjective risk of hospitalization itself, and this work provides new objective evidence that hospitalization confers specific and quantifiable risks. Though we can undoubtedly use this knowledge to guide internal decisions about admissions and discharges, do we also have an obligation to inform our patients about these risks in real time? Ultimately, hospitalization itself might be viewed as a “procedure” or intervention that has inherent risks for all who receive it, regardless of the individual patient or hospital characteristics. As hospitalists, we should continue to strive to reduce these risks, but we should also initiate a conversation about the risks and benefits of hospitalization similarly to how we discuss other procedures with patients and their families.

1. Sekijima A, Sunga C, Bann M. Adverse events experienced by patients hospitalized without definite medical acuity: A retrospective cohort study. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(1):42-45. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3235.

2. Wang ES, Velásquez ST, Smith CJ, et al. Triaging inpatient admissions : An opportunity for resident education. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(5):754-757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04882-2.

3. Pope I, Burn H, Ismail SA, et al. A qualitative study exploring the factors influencing admission to hospital from the emergency department. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e011543. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011543.

4. Lewis Hunter AE, Spatz ES, Bernstein SL, Rosenthal MS. Factors influencing hospital admission of non-critically ill patients presenting to the emergency department: a cross-sectional study. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):37-44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3438-8.

Even though I could not remember her name, I remembered her story, and I would bet that my colleagues did as well. She was someone that we had all cared for at one time or another. She frequently presented to the hospital with chest pain or shortness of breath attributable to a combination of longstanding congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cocaine abuse. But most tragic of all, she was homeless, which meant that she was frequently hospitalized not only for medical complaints but also for a night’s shelter and a bite of food. Even though she often refused medical treatment and social workers’ efforts to stabilize her housing situation, the staff in the emergency room and observation unit all knew her by name and greeted her like an old friend. And then one day she stopped showing up to the hospital. Sitting in the emergency department (ED), I overheard that she was found outside of a storefront and had passed away. Saddened by her death, which was not unexpected given her medical issues, I still wondered if we had done right by her during the hundreds of times that she had come to our hospital. Clinicians at busy safety-net hospitals face these questions every day, and it would seem beyond doubt that our duty is to address both medical and nonmedical determinants of health of everyone that walks through our door. But is this in fact the right thing to do? Is it possible that we unwittingly expose these vulnerable patients to risks from hospitalization alone?

In this month’s Journal of Hospital Medicine, Sekijima et al. sought to quantify precisely the risks of hospitalization, particularly among the subset of patients whose “severity” of medical problems alone might not have warranted hospital admission, a scenario known colloquially as a “social” admission.1 In real time, an inhouse triage physician classified patients as being admitted with or without “definite medical acuity.” Investigators retrospectively identified adverse events and illness acuity using standardized instruments, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Global Trigger Tool and Emergency Severity Index, respectively. Despite the acknowledged differences in the patient population and the inherent subjectivity within the designation process, Sekijima et al. found no statistically significant difference in the percentage of admissions with an adverse event nor in the rate of adverse events per 1,000 patient days. Falls, oversedation/hypotension and code/arrest/rapid response activation were the most frequently encountered adverse events.

Delving deeper into the origin of admissions without definite medical acuity, the authors identified homelessness, lack of outpatient social support, substance use disorder, and lack of outpatient medical support as the most common reasons for “nonmedical” admissions. As healthcare providers, we recognize that these factors are generally long-term, chronic socioeconomic determinants of health. Despite our objective knowledge that we are limited in our ability to fix these problems on a short-term basis, the authors’ observations reflect our compulsion to try and help in any way possible. Patients admitted without definite medical acuity were more vulnerable and had higher rates of public insurance and housing insecurity. However, they were less acutely ill, as indicated by lower Emergency Severity Index scores. These factors were not associated with statistically significant differences in either 48-hour ED readmission or 30-day hospital readmission rates.

The process of appropriately triaging patients to an inpatient setting is challenging because of wide variability in both patients and ED providers. Hospitalists are increasingly recognized as an additional resource to assist in the triage process, as we are uniquely in a position to view the patient’s clinical presentation within the context of their anticipated clinical trajectory, promote effective utilization of inpatient bed availability, and anticipate potential barriers to discharge. Graduate medical education now identifies the triage process as a specific milestone within the transitions of care competency, as it requires mastery of interpersonal communication, professionalism, systems-based thinking, and patient-centered care.2 However, many institutions lack a dedicated faculty member to perform the triage role. Our institution recently examined the feasibility of instituting a daily “huddle” between the admitting hospitalist and the ED to facilitate interdepartmental communication to create care plans in patient triage and to promote patient throughput. Available admission beds are valuable commodities, and one challenge is that the ED makes disposition decisions without knowledge of the number of available beds in the hospital. The goal of the huddle was to quickly discuss all patients potentially requiring admission prior to the final disposition decision and to address any modifiable factors to potentially prevent a “social” admission with social work early in the day. Further work is in progress to determine if introducing flexibility within existing provider roles can improve the triage process in a measurable and efficient manner.

Many challenges remain as we balance the medical needs of patients with any potential social drivers that necessitate admission to the inpatient hospital setting. From an ED perspective, social support and community follow-up were “universally considered powerful influences on admission,” and other factors such as time of day, clinical volume, and the four-hour waiting time target also played a significant role in the decision to admit.3 Hunter et al. found that admissions with moderate to low acuity may be shorter or less costly,4 which presents an interesting question of cost-effectiveness as an avenue for further study. As clinicians, we are intuitively aware of the subjective risk of hospitalization itself, and this work provides new objective evidence that hospitalization confers specific and quantifiable risks. Though we can undoubtedly use this knowledge to guide internal decisions about admissions and discharges, do we also have an obligation to inform our patients about these risks in real time? Ultimately, hospitalization itself might be viewed as a “procedure” or intervention that has inherent risks for all who receive it, regardless of the individual patient or hospital characteristics. As hospitalists, we should continue to strive to reduce these risks, but we should also initiate a conversation about the risks and benefits of hospitalization similarly to how we discuss other procedures with patients and their families.

Even though I could not remember her name, I remembered her story, and I would bet that my colleagues did as well. She was someone that we had all cared for at one time or another. She frequently presented to the hospital with chest pain or shortness of breath attributable to a combination of longstanding congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cocaine abuse. But most tragic of all, she was homeless, which meant that she was frequently hospitalized not only for medical complaints but also for a night’s shelter and a bite of food. Even though she often refused medical treatment and social workers’ efforts to stabilize her housing situation, the staff in the emergency room and observation unit all knew her by name and greeted her like an old friend. And then one day she stopped showing up to the hospital. Sitting in the emergency department (ED), I overheard that she was found outside of a storefront and had passed away. Saddened by her death, which was not unexpected given her medical issues, I still wondered if we had done right by her during the hundreds of times that she had come to our hospital. Clinicians at busy safety-net hospitals face these questions every day, and it would seem beyond doubt that our duty is to address both medical and nonmedical determinants of health of everyone that walks through our door. But is this in fact the right thing to do? Is it possible that we unwittingly expose these vulnerable patients to risks from hospitalization alone?

In this month’s Journal of Hospital Medicine, Sekijima et al. sought to quantify precisely the risks of hospitalization, particularly among the subset of patients whose “severity” of medical problems alone might not have warranted hospital admission, a scenario known colloquially as a “social” admission.1 In real time, an inhouse triage physician classified patients as being admitted with or without “definite medical acuity.” Investigators retrospectively identified adverse events and illness acuity using standardized instruments, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Global Trigger Tool and Emergency Severity Index, respectively. Despite the acknowledged differences in the patient population and the inherent subjectivity within the designation process, Sekijima et al. found no statistically significant difference in the percentage of admissions with an adverse event nor in the rate of adverse events per 1,000 patient days. Falls, oversedation/hypotension and code/arrest/rapid response activation were the most frequently encountered adverse events.

Delving deeper into the origin of admissions without definite medical acuity, the authors identified homelessness, lack of outpatient social support, substance use disorder, and lack of outpatient medical support as the most common reasons for “nonmedical” admissions. As healthcare providers, we recognize that these factors are generally long-term, chronic socioeconomic determinants of health. Despite our objective knowledge that we are limited in our ability to fix these problems on a short-term basis, the authors’ observations reflect our compulsion to try and help in any way possible. Patients admitted without definite medical acuity were more vulnerable and had higher rates of public insurance and housing insecurity. However, they were less acutely ill, as indicated by lower Emergency Severity Index scores. These factors were not associated with statistically significant differences in either 48-hour ED readmission or 30-day hospital readmission rates.

The process of appropriately triaging patients to an inpatient setting is challenging because of wide variability in both patients and ED providers. Hospitalists are increasingly recognized as an additional resource to assist in the triage process, as we are uniquely in a position to view the patient’s clinical presentation within the context of their anticipated clinical trajectory, promote effective utilization of inpatient bed availability, and anticipate potential barriers to discharge. Graduate medical education now identifies the triage process as a specific milestone within the transitions of care competency, as it requires mastery of interpersonal communication, professionalism, systems-based thinking, and patient-centered care.2 However, many institutions lack a dedicated faculty member to perform the triage role. Our institution recently examined the feasibility of instituting a daily “huddle” between the admitting hospitalist and the ED to facilitate interdepartmental communication to create care plans in patient triage and to promote patient throughput. Available admission beds are valuable commodities, and one challenge is that the ED makes disposition decisions without knowledge of the number of available beds in the hospital. The goal of the huddle was to quickly discuss all patients potentially requiring admission prior to the final disposition decision and to address any modifiable factors to potentially prevent a “social” admission with social work early in the day. Further work is in progress to determine if introducing flexibility within existing provider roles can improve the triage process in a measurable and efficient manner.

Many challenges remain as we balance the medical needs of patients with any potential social drivers that necessitate admission to the inpatient hospital setting. From an ED perspective, social support and community follow-up were “universally considered powerful influences on admission,” and other factors such as time of day, clinical volume, and the four-hour waiting time target also played a significant role in the decision to admit.3 Hunter et al. found that admissions with moderate to low acuity may be shorter or less costly,4 which presents an interesting question of cost-effectiveness as an avenue for further study. As clinicians, we are intuitively aware of the subjective risk of hospitalization itself, and this work provides new objective evidence that hospitalization confers specific and quantifiable risks. Though we can undoubtedly use this knowledge to guide internal decisions about admissions and discharges, do we also have an obligation to inform our patients about these risks in real time? Ultimately, hospitalization itself might be viewed as a “procedure” or intervention that has inherent risks for all who receive it, regardless of the individual patient or hospital characteristics. As hospitalists, we should continue to strive to reduce these risks, but we should also initiate a conversation about the risks and benefits of hospitalization similarly to how we discuss other procedures with patients and their families.

1. Sekijima A, Sunga C, Bann M. Adverse events experienced by patients hospitalized without definite medical acuity: A retrospective cohort study. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(1):42-45. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3235.

2. Wang ES, Velásquez ST, Smith CJ, et al. Triaging inpatient admissions : An opportunity for resident education. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(5):754-757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04882-2.

3. Pope I, Burn H, Ismail SA, et al. A qualitative study exploring the factors influencing admission to hospital from the emergency department. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e011543. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011543.

4. Lewis Hunter AE, Spatz ES, Bernstein SL, Rosenthal MS. Factors influencing hospital admission of non-critically ill patients presenting to the emergency department: a cross-sectional study. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):37-44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3438-8.

1. Sekijima A, Sunga C, Bann M. Adverse events experienced by patients hospitalized without definite medical acuity: A retrospective cohort study. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(1):42-45. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3235.

2. Wang ES, Velásquez ST, Smith CJ, et al. Triaging inpatient admissions : An opportunity for resident education. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(5):754-757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04882-2.

3. Pope I, Burn H, Ismail SA, et al. A qualitative study exploring the factors influencing admission to hospital from the emergency department. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e011543. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011543.

4. Lewis Hunter AE, Spatz ES, Bernstein SL, Rosenthal MS. Factors influencing hospital admission of non-critically ill patients presenting to the emergency department: a cross-sectional study. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):37-44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3438-8.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Cognitive Biases Influence Decision-Making Regarding Postacute Care in a Skilled Nursing Facility

The combination of decreasing hospital lengths of stay and increasing age and comorbidity of the United States population is a principal driver of the increased use of postacute care in the US.1-3 Postacute care refers to care in long-term acute care hospitals, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), and care provided by home health agencies after an acute hospitalization. In 2016, 43% of Medicare beneficiaries received postacute care after hospital discharge at the cost of $60 billion annually; nearly half of these received care in an SNF.4 Increasing recognition of the significant cost and poor outcomes of postacute care led to payment reforms, such as bundled payments, that incentivized less expensive forms of postacute care and improvements in outcomes.5-9 Early evaluations suggested that hospitals are sensitive to these reforms and responded by significantly decreasing SNF utilization.10,11 It remains unclear whether this was safe and effective.

In this context, increased attention to how hospital clinicians and hospitalized patients decide whether to use postacute care (and what form to use) is appropriate since the effect of payment reforms could negatively impact vulnerable populations of older adults without adequate protection.12 Suboptimal decision-making can drive both overuse and inappropriate underuse of this expensive medical resource. Initial evidence suggests that patients and clinicians are poorly equipped to make high-quality decisions about postacute care, with significant deficits in both the decision-making process and content.13-16 While these gaps are important to address, they may only be part of the problem. The fields of cognitive psychology and behavioral economics have revealed new insights into decision-making, demonstrating that people deviate from rational decision-making in predictable ways, termed decision heuristics, or cognitive biases.17 This growing field of research suggests heuristics or biases play important roles in decision-making and determining behavior, particularly in situations where there may be little information provided and the patient is stressed, tired, and ill—precisely like deciding on postacute care.18 However, it is currently unknown whether cognitive biases are at play when making hospital discharge decisions.

We sought to identify the most salient heuristics or cognitive biases patients may utilize when making decisions about postacute care at the end of their hospitalization and ways clinicians may contribute to these biases. The overall goal was to derive insights for improving postacute care decision-making.

METHODS

Study Design

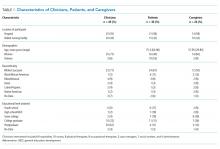

We conducted a secondary analysis on interviews with hospital and SNF clinicians as well as patients and their caregivers who were either leaving the hospital for an SNF or newly arrived in an SNF from the hospital to understand if cognitive biases were present and how they manifested themselves in a real-world clinical context.19 These interviews were part of a larger qualitative study that sought to understand how clinicians, patients, and their caregivers made decisions about postacute care, particularly related to SNFs.13,14 This study represents the analysis of all our interviews, specifically examining decision-making bias. Participating sites, clinical roles, and both patient and caregiver characteristics (Table 1) in our cohort have been previously described.13,14

Analysis

We used a team-based approach to framework analysis, which has been used in other decision-making studies14, including those measuring cognitive bias.20 A limitation in cognitive bias research is the lack of a standardized list or categorization of cognitive biases. We reviewed prior systematic17,21 and narrative reviews18,22, as well as prior studies describing examples of cognitive biases playing a role in decision-making about therapy20 to construct a list of possible cognitive biases to evaluate and narrow these a priori to potential biases relevant to the decision about postacute care based on our prior work (Table 2).

We applied this framework to analyze transcripts through an iterative process of deductive coding and reviewing across four reviewers (ML, RA, AL, CL) and a hospitalist physician with expertise leading qualitative studies (REB).

Intercoder consensus was built through team discussion by resolving points of disagreement.23 Consistency of coding was regularly checked by having more than one investigator code individual manuscripts and comparing coding, and discrepancies were resolved through team discussion. We triangulated the data (shared our preliminary results) using a larger study team, including an expert in behavioral economics (SRG), physicians at study sites (EC, RA), and an anthropologist with expertise in qualitative methods (CL). We did this to ensure credibility (to what extent the findings are credible or believable) and confirmability of findings (ensuring the findings are based on participant narratives rather than researcher biases).

RESULTS

We reviewed a total of 105 interviews with 25 hospital clinicians, 20 SNF clinicians, 21 patients and 14 caregivers in the hospital, and 15 patients and 10 caregivers in the SNF setting (Table 1). We found authority bias/halo effect; default/status quo bias, anchoring bias, and framing was commonly present in decision-making about postacute care in a SNF, whereas there were few if any examples of ambiguity aversion, availability heuristic, confirmation bias, optimism bias, or false consensus effect (Table 2).

Authority Bias/Halo Effect

While most patients deferred to their inpatient teams when it came to decision-making, this effect seemed to differ across VA and non-VA settings. Veterans expressed a higher degree of potential authority bias regarding the VA as an institution, whereas older adults in non-VA settings saw physicians as the authority figure making decisions in their best interests.

Veterans expressed confidence in the VA regarding both whether to go to a SNF and where to go:

“The VA wouldn’t license [an SNF] if they didn’t have a good reputation for care, cleanliness, things of that nature” (Veteran, VA CLC)

“I just knew the VA would have my best interests at heart” (Veteran, VA CLC)

Their caregivers expressed similar confidence:

“I’m not gonna decide [on whether the patient they care for goes to postacute care], like I told you, that’s totally up to the VA. I have trust and faith in them…so wherever they send him, that’s where he’s going” (Caregiver, VA hospital)

In some cases, this perspective was closer to the halo effect: a positive experience with the care provider or the care team led the decision-makers to believe that their recommendations about postacute care would be similarly positive.

“I think we were very trusting in the sense that whatever happened the last time around, he survived it…they took care of him…he got back home, and he started his life again, you know, so why would we question what they’re telling us to do? (Caregiver, VA hospital)

In contrast to Veterans, non-Veteran patients seemed to experience authority bias when it came to the inpatient team.

“Well, I’d like to know more about the PTs [Physical Therapists] there, but I assume since they were recommended, they will be good.” (Patient, University hospital)

This perspective was especially apparent when it came to physicians:

“The level of trust that they [patients] put in their doctor is gonna outweigh what anyone else would say.” (Clinical liaison, SNF)

“[In response to a question about influences on the decision to go to rehab] I don’t…that’s not my decision to make, that’s the doctor’s decision.” (Patient, University hospital)

“They said so…[the doctor] said I needed to go to rehab, so I guess I do because it’s the doctor’s decision.” (Patient, University hospital)

Default/Status quo Bias

In a related way, patients and caregivers with exposure to a SNF seemed to default to the same SNF with which they had previous experience. This bias seems to be primarily related to knowing what to expect.

“He thinks it’s [a particular SNF] the right place for him now…he was there before and he knew, again, it was the right place for him to be” (Caregiver, VA hospital)

“It’s the only one I’ve ever been in…but they have a lot of activities; you have a lot of freedom, staff was good” (Patient, VA hospital)

“I’ve been [to this SNF] before and I kind of know what the program involves…so it was kind of like going home, not, going home is the wrong way to put it…I mean coming here is like something I know, you know, I didn’t need anybody to explain it to me.” (Patient, VA hospital)

“Anybody that’s been to [SNF], that would be their choice to go back to, and I guess I must’ve liked it that first time because I asked to go back again.” (Patient, University hospital)

Anchoring Bias

While anchoring bias was less frequent, it came up in two domains: first, related to costs of care, and second, related to facility characteristics. Costs came up most frequently for Veterans who preferred to move their care to the VA for cost reasons, which appeared in these cases to overshadow other considerations:

“I kept emphasizing that the VA could do all the same things at a lot more reasonable price. The whole purpose of having the VA is for the Veteran, so that…we can get the healthcare that we need at a more reasonable [sic] or a reasonable price.” (Veteran, CLC)

“I think the CLC [VA SNF] is going to take care of her probably the same way any other facility of its type would, unless she were in a private facility, but you know, that costs a lot more money.” (Caregiver, VA hospital)

Patients occasionally had striking responses to particular characteristics of SNFs, regardless of whether this was a central feature or related to their rehabilitation:

“The social worker comes and talks to me about the nursing home where cats are running around, you know, to infect my leg or spin their little cat hairs into my lungs and make my asthma worse…I’m going to have to beg the nurses or the aides or the family or somebody to clean the cat…” (Veteran, VA hospital)

Framing

Framing was the strongest theme among clinician interviews in our sample. Clinicians most frequently described the SNF as a place where patients could recover function (a positive frame), explaining risks (eg, rehospitalization) associated with alternative postacute care options besides the SNF in great detail.

“Aside from explaining the benefits of going and…having that 24-hour care, having the therapies provided to them [the patients], talking about them getting stronger, phrasing it in such a way that patients sometimes are more agreeable, like not calling it a skilled nursing facility, calling it a rehab you know, for them to get physically stronger so they can be the most independent that they can once they do go home, and also explaining … we think that this would be the best plan to prevent them from coming back to the hospital, so those are some of the things that we’ll mention to patients to try and educate them and get them to be agreeable for placement.” (Social worker, University hospital)

Clinicians avoided negative associations with “nursing home” (even though all SNFs are nursing homes) and tended to use more positive frames such as “rehabilitation facility.”

“Use the word rehab….we definitely use the word rehab, to get more therapy, to go home; it’s not a, we really emphasize it’s not a nursing home, it’s not to go to stay forever.” (Physical therapist, safety-net hospital)

Clinicians used a frame of “safety” when discussing the SNF and used a frame of “risk” when discussing alternative postacute care options such as returning home. We did not find examples of clinicians discussing similar risks in going to a SNF even for risks, such as falling, which exist in both settings.

“I’ve talked to them primarily on an avenue of safety because I think people want and they value independence, they value making sure they can get home, but you know, a lot of the times they understand safety is, it can be a concern and outlining that our goal is to make sure that they’re safe and they stay home, and I tend to broach the subject saying that our therapists believe that they might not be safe at home in the moment, but they have potential goals to be safe later on if we continue therapy. I really highlight safety being the major driver of our discussion.” (Physician, VA hospital)

In some cases, framing was so overt that other risk-mitigating options (eg, home healthcare) are not discussed.

“I definitely tend to explain the ideal first. I’m not going to bring up home care when we really think somebody should go to rehab, however, once people say I don’t want to do that, I’m not going, then that’s when I’m like OK, well, let’s talk to the doctors, but we can see about other supports in the home.” (Social worker, VA hospital)

DISCUSSION

In a large sample of patients and their caregivers, as well as multidisciplinary clinicians at three different hospitals and three SNFs, we found authority bias/halo effect and framing biases were most common and seemed most impactful. Default/status quo bias and anchoring bias were also present in decision-making about a SNF. The combination of authority bias/halo effect and framing biases could synergistically interact to augment the likelihood of patients accepting a SNF for postacute care. Patients who had been to a SNF before seemed more likely to choose the SNF they had experienced previously even if they had no other postacute care experiences, and could be highly influenced by isolated characteristics of that facility (such as the physical environment or cost of care).

It is important to mention that cognitive biases do not necessarily have a negative impact: indeed, as Kahneman and Tversky point out, these are useful heuristics from “fast” thinking that are often effective.24 For example, clinicians may be trying to act in the best interests of the patient when framing the decision in terms of regaining function and averting loss of safety and independence. However, the evidence base regarding the outcomes of an SNF versus other postacute options is not robust, and this decision-making is complex. While this decision was most commonly framed in terms of rehabilitation and returning home, the fact that only about half of patients have returned to the community by 100 days4 was not discussed in any interview. In fact, initial evidence suggests replacing the SNF with home healthcare in patients with hip and knee arthroplasty may reduce costs without worsening clinical outcomes.6 However, across a broader population, SNFs significantly reduce 30-day readmissions when directly compared with home healthcare, but other clinical outcomes are similar.25 This evidence suggests that the “right” postacute care option for an individual patient is not clear, highlighting a key role biases may play in decision-making. Further, the nebulous concept of “safety” could introduce potential disparities related to social determinants of health.12 The observed inclination to accept an SNF with which the individual had prior experience may be influenced by the acceptability of this choice because of personal factors or prior research, even if it also represents a bias by limiting the consideration of current alternatives.

Our findings complement those of others in the literature which have also identified profound gaps in discharge decision-making among patients and clinicians,13-16,26-31 though to our knowledge the role of cognitive biases in these decisions has not been explored. This study also addresses gaps in the cognitive bias literature, including the need for real-world data rather than hypothetical vignettes,17 and evaluation of treatment and management decisions rather than diagnoses, which have been more commonly studied.21

These findings have implications for both individual clinicians and healthcare institutions. In the immediate term, these findings may serve as a call to discharging clinicians to modulate language and “debias” their conversations with patients about care after discharge.18,22 Shared decision-making requires an informed choice by patients based on their goals and values; framing a decision in a way that puts the clinician’s goals or values (eg, safety) ahead of patient values (eg, independence and autonomy) or limits disclosure (eg, a “rehab” is a nursing home) in the hope of influencing choice may be more consistent with framing bias and less with shared decision-making.14 Although controversy exists about the best way to “debias” oneself,32 self-awareness of bias is increasingly recognized across healthcare venues as critical to improving care for vulnerable populations.33 The use of data rather than vignettes may be a useful debiasing strategy, although the limitations of currently available data (eg, capturing nursing home quality) are increasingly recognized.34 From a policy and health system perspective, cognitive biases should be integrated into the development of decision aids to facilitate informed, shared, and high-quality decision-making that incorporates patient values, and perhaps “nudges” from behavioral economics to assist patients in choosing the right postdischarge care for them. Such nudges use principles of framing to influence care without restricting choice.35 As the science informing best practice regarding postacute care improves, identifying the “right” postdischarge care may become easier and recommendations more evidence-based.36

Strengths of the study include a large, diverse sample of patients, caregivers, and clinicians in both the hospital and SNF setting. Also, we used a team-based analysis with an experienced team and a deep knowledge of the data, including triangulation with clinicians to verify results. However, all hospitals and SNFs were located in a single metropolitan area, and responses may vary by region or population density. All three hospitals have housestaff teaching programs, and at the time of the interviews all three community SNFs were “five-star” facilities on the Nursing Home Compare website; results may be different at community hospitals or other SNFs. Hospitalists were the only physician group sampled in the hospital as they provide the majority of inpatient care to older adults; geriatricians, in particular, may have had different perspectives. Since we intended to explore whether cognitive biases were present overall, we did not evaluate whether cognitive biases differed by role or subgroup (by clinician type, patient, or caregiver), but this may be a promising area to explore in future work. Many cognitive biases have been described, and there are likely additional biases we did not identify. To confirm the generalizability of these findings, they should be studied in a larger, more generalizable sample of respondents in future work.

Cognitive biases play an important role in patient decision-making about postacute care, particularly regarding SNF care. As postacute care undergoes a transformation spurred by payment reforms, it is more important than ever to ensure that patients understand their choices at hospital discharge and can make a high-quality decision consistent with their goals.