User login

Update in Hospital Medicine: Practical Lessons from the Literature

ESSENTIAL PUBLICATIONS

Prevalence of Pulmonary Embolism among Patients Hospitalized for Syncope. Prandoni P et al. New England Journal of Medicine, 2016;375(16):1524-31.1

Background

Pulmonary embolism (PE), a potentially fatal disease, is rarely considered as a likely cause of syncope. To determine the prevalence of PE among patients presenting with their first episode of syncope, the authors performed a systematic workup for pulmonary embolism in adult patients admitted for syncope at 11 hospitals in Italy.

Findings

Of the 2584 patients who presented to the emergency department (ED) with syncope during the study, 560 patients were admitted and met the inclusion criteria. A modified Wells Score was applied, and a D-dimer was measured on every hospitalized patient. Those with a high pretest probability, a Wells Score of 4.0 or higher, or a positive D-dimer underwent further testing for pulmonary embolism by a CT scan, a ventilation perfusion scan, or an autopsy. Ninety-seven of the 560 patients admitted to the hospital for syncope were found to have a PE (17%). One in

Cautions

Nearly 72% of the patients with common explanations for syncope, such as vasovagal, drug-induced, or volume depletion, were discharged from the ED and not included in the study. The authors focused on the prevalence of PE. The causation between PE and syncope is not clear in each of the patients. Of the patients’ diagnosis by a CT, only 67% of the PEs were found to be in a main pulmonary artery or lobar artery. The other 33% were segmental or subsegmental. Of those diagnosed by a ventilation perfusion scan, 50% of the patients had 25% or more of the area of both lungs involved. The other 50% involved less than 25% of the area of both lungs. Also, it is important to note that 75% of the patients admitted to the hospital in this study were 70 years of age or older.

Implications

After common diagnoses are ruled out, it is important to consider pulmonary embolism in patients hospitalized with syncope. Providers should calculate a Wells Score and measure a D-dimer to guide the decision making.

Assessing the Risks Associated with MRI in Patients with a Pacemaker or Defibrillator. Russo RJ et al. New England Journal of Medicine, 2017;376(8):755-64.2

Background

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in patients with implantable cardiac devices is considered a safety risk due to the potential of cardiac lead heating and subsequent myocardial injury or alterations of the pacing properties. Although manufacturers have developed “MRI-conditional” devices designed to reduce these risks, still 2 million people in the United States and 6 million people worldwide have “non–MRI-conditional” devices. The authors evaluated the event rates in patients with “non-MRI-conditional” devices undergoing an MRI.

Findings

The authors prospectively followed up 1500 adults with cardiac devices placed since 2001 who received nonthoracic MRIs according to a specific protocol available in the supplemental materials published with this article in the New England Journal of Medicine. Of the 1000 patients with pacemakers only, they observed 5 atrial arrhythmias and 6 electrical resets. Of the 500 patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs), they observed 1 atrial arrhythmia and 1 generator failure (although this case had deviated from the protocol). All of the atrial arrhythmias were self-terminating. No deaths, lead failure requiring an immediate replacement, a loss of capture, or ventricular arrhythmias were observed.

Cautions

Patients who were pacing dependent were excluded. No devices implanted before 2001 were included in the study, and the MRIs performed were only 1.5 Tesla (a lower field strength than the also available 3 Tesla MRIs).

Implications

It is safe to proceed with 1.5 Tesla nonthoracic MRIs in patients, following the protocol outlined in this article, with non–MRI conditional cardiac devices implanted since 2001.

Culture If Spikes? Indications and Yield of Blood Cultures in Hospitalized Medical Patients. Linsenmeyer K et al. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 2016;11(5):336-40.3

Background

Blood cultures are frequently drawn for the evaluation of an inpatient fever. This “culture if spikes” approach may lead to unnecessary testing and false positive results. In this study, the authors evaluated rates of true positive and false positive blood cultures in the setting of an inpatient fever.

Findings

The patients hospitalized on the general medicine or cardiology floors at a Veterans Affairs teaching hospital were prospectively followed over 7 months. A total of 576 blood cultures were ordered among 323 unique patients. The patients were older (average age of 70 years) and predominantly male (94%). The true-positive rate for cultures, determined by a consensus among the microbiology and infectious disease departments based on a review of clinical and laboratory data, was 3.6% compared with a false-positive rate of 2.3%. The clinical characteristics associated with a higher likelihood of a true positive included: the indication for a culture as a follow-up from a previous culture (likelihood ratio [LR] 3.4), a working diagnosis of bacteremia or endocarditis (LR 3.7), and the constellation of fever and leukocytosis in a patient who has not been on antibiotics (LR 5.6).

Cautions

This study was performed at a single center with patients in the medicine and cardiology services, and thus, the data is representative of clinical practice patterns specific to that site.

Implications

Reflexive ordering of blood cultures for inpatient fever is of a low yield with a false-positive rate that approximates the true positive rate. A large number of patients are tested unnecessarily, and for those with positive tests, physicians are as likely to be misled as they are certain to truly identify a pathogen. The positive predictive value of blood cultures is improved when drawn on patients who are not on antibiotics and when the patient has a specific diagnosis, such as pneumonia, previous bacteremia, or suspected endocarditis.

Incidence of and Risk Factors for Chronic Opioid Use among Opioid-Naive Patients in the Postoperative Period. Sun EC et al. JAMA Internal Medicine, 2016;176(9):1286-93.4

Background

Each day in the United States, 650,000 opioid prescriptions are filled, and 78 people suffer an opiate-related death. Opioids are frequently prescribed for inpatient management of postoperative pain. In this study, authors compared the development of chronic opioid use between patients who had undergone surgery and those who had not.

Findings

This was a retrospective analysis of a nationwide insurance claims database. A total of 641,941 opioid-naive patients underwent 1 of 11 designated surgeries in the study period and were compared with 18,011,137 opioid-naive patients who did not undergo surgery. Chronic opioid use was defined as the filling of 10 or more prescriptions or receiving more than a 120-day supply between 90 and 365 days postoperatively (or following the assigned faux surgical date in those not having surgery). This was observed in a small proportion of the surgical patients (less than 0.5%). However, several procedures were associated with the increased odds of postoperative chronic opioid use, including a simple mastectomy (Odds ratio [OR] 2.65), a cesarean delivery (OR 1.28), an open appendectomy (OR 1.69), an open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy (ORs 3.60 and 1.62, respectively), and a total hip and total knee arthroplasty (ORs 2.52 and 5.10, respectively). Also, male sex, age greater than 50 years, preoperative benzodiazepines or antidepressants, and a history of drug abuse were associated with increased odds.

Cautions

This study was limited by the claims-based data and that the nonsurgical population was inherently different from the surgical population in ways that could lead to confounding.

Implications

In perioperative care, there is a need to focus on multimodal approaches to pain and to implement opioid reducing and sparing strategies that might include options such as acetaminophen, NSAIDs, neuropathic pain medications, and Lidocaine patches. Moreover, at discharge, careful consideration should be given to the quantity and duration of the postoperative opioids.

Rapid Rule-out of Acute Myocardial Infarction with a Single High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin T Measurement below the Limit of Detection: A Collaborative Meta-Analysis. Pickering JW et al. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2017;166:715-24.5

Background

High-sensitivity cardiac troponin testing (hs-cTnT) is now available in the United States. Studies have found that these can play a significant role in a rapid rule-out of acute myocardial infarction (AMI).

Findings

In this meta-analysis, the authors identified 11 studies with 9241 participants that prospectively evaluated patients presenting to the emergency department (ED) with chest pain, underwent an ECG, and had hs-cTnT drawn. A total of 30% of the patients were classified as low risk with negative hs-cTnT and negative ECG (defined as no ST changes or T-wave inversions indicative of ischemia). Among the low risk patients, only 14 of the 2825 (0.5%) had AMI according to the Global Task Forces definition.6 Seven of these were in patients with hs-cTnT drawn within 3 hours of a chest pain onset. The pooled negative predictive value was 99.0% (CI 93.8%–99.8%).

Cautions

The heterogeneity between the studies in this meta-analysis, especially in the exclusion criteria, warrants careful consideration when being implemented in new settings. A more sensitive test will result in more positive troponins due to different limits of detection. Thus, medical teams and institutions need to plan accordingly. Caution should be taken for any patient presenting within 3 hours of a chest pain onset.

Implications

Rapid rule-out protocols—which include clinical evaluation, a negative ECG, and a negative high-sensitivity cardiac troponin—identify a large proportion of low-risk patients who are unlikely to have a true AMI.

Prevalence and Localization of Pulmonary Embolism in Unexplained Acute Exacerbations of COPD: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Aleva FE et al. Chest, 2017;151(3):544-54.7

Background

Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AE-COPD) are frequent. In up to 30%, no clear trigger is found. Previous studies suggested that 1 in 4 of these patients may have a pulmonary embolus (PE).7 This study reviewed the literature and meta-data to describe the prevalence, the embolism location, and the clinical predictors of PE among patients with unexplained AE-COPD.

Findings

A systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis identified 7 studies with 880 patients. In the pooled analysis, 16% had PE (range: 3%–29%). Of the 120 patients with PE, two-thirds were in lobar or larger arteries and one-third in segmental or smaller. Pleuritic chest pain and signs of cardiac compromise (hypotension, syncope, and right-sided heart failure) were associated with PE.

Cautions

This study was heterogeneous leading to a broad confidence interval for prevalence ranging from 8%–25%. Given the frequency of AE-COPD with no identified trigger, physicians need to attend to risks of repeat radiation exposure when considering an evaluation for PE.

Implications

One in 6 patients with unexplained AE-COPD was found to have PE; the odds were greater in those with pleuritic chest pain or signs of cardiac compromise. In patients with AE-COPD with an unclear trigger, the providers should consider an evaluation for PE by using a clinical prediction rule and/or a D-dimer.

Sitting at Patients’ Bedsides May Improve Patients’ Perceptions of Physician Communication Skills. Merel SE et al. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 2016;11(12):865-8.9

Background

Sitting at a patient’s bedside in the inpatient setting is considered a best practice, yet it has not been widely adopted. The authors conducted a cluster-randomized trial of physicians on a single 28-bed hospitalist only run unit where physicians were assigned to sitting or standing for the first 3 days of a 7-day workweek assignment. New admissions or transfers to the unit were considered eligible for the study.

Findings

Sixteen hospitalists saw on an average 13 patients daily during the study (a total of 159 patients were included in the analysis after 52 patients were excluded or declined to participate). The hospitalists were 69% female, and 81% had been in practice 3 years or less. The average time spent in the patient’s room was 12:00 minutes while seated and 12:10 minutes while standing. There was no difference in the patients’ perception of the amount of time spent—the patients overestimated this by 4 minutes in both groups. Sitting was associated with higher ratings for “listening carefully” and “explaining things in a way that was easy to understand.” There was no difference in ratings on the physicians interrupting the patient when talking or in treating patients with courtesy and respect.

Cautions

The study had a small sample size, was limited to English-speaking patients, and was a single-site study. It involved only attending-level physicians and did not involve nonphysician team members. The physicians were not blinded and were aware that the interactions were monitored, perhaps creating a Hawthorne effect. The analysis did not control for other factors such as the severity of the illness, the number of consultants used, or the degree of health literacy.

Implications

This study supports an important best practice highlighted in etiquette-based medicine 10: sitting at the bedside provided a benefit in the patient’s perception of communication by physicians without a negative effect on the physician’s workflow.

The Duration of Antibiotic Treatment in Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Multi-Center Randomized Clinical Trial. Uranga A et al. JAMA Intern Medicine, 2016;176(9):1257-65.11

Background

The optimal duration of treatment for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is unclear; a growing body of evidence suggests shorter and longer durations may be equivalent.

Findings

At 4 hospitals in Spain, 312 adults with a mean age of 65 years and a diagnosis of CAP (non-ICU) were randomized to a short (5 days) versus a long (provider discretion) course of antibiotics. In the short-course group, the antibiotics were stopped after 5 days if the body temperature had been 37.8o C or less for 48 hours, and no more than 1 sign of clinical instability was present (SBP < 90 mmHg, HR >100/min, RR > 24/min, O2Sat < 90%). The median number of antibiotic days was 5 for the short-course group and 10 for the long-course group (P < .01). There was no difference in the resolution of pneumonia symptoms at 10 days or 30 days or in 30-day mortality. There were no differences in in-hospital side effects. However, 30-day readmissions were higher in the long-course group compared with the short-course group (6.6% vs 1.4%; P = .02). The results were similar across all of the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) classes.

Cautions

Most of the patients were not severely ill (~60% PSI I-III), the level of comorbid disease was low, and nearly 80% of the patients received fluoroquinolone. There was a significant cross over with 30% of patients assigned to the short-course group receiving antibiotics for more than 5 days.

Implications

Inpatient providers should aim to treat patients with community-acquired pneumonia (regardless of the severity of the illness) for 5 days. At day 5, if the patient is afebrile and has no signs of clinical instability, clinicians should be comfortable stopping antibiotics.

Is the Era of Intravenous Proton Pump Inhibitors Coming to an End in Patients with Bleeding Peptic Ulcers? A Meta-Analysis of the Published Literature. Jian Z et al. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 2016;82(3):880-9.12

Background

Guidelines recommend intravenous proton pump inhibitors (PPI) after an endoscopy for patients with a bleeding peptic ulcer. Yet, acid suppression with oral PPI is deemed equivalent to the intravenous route.

Findings

This systematic review and meta-analysis identified 7 randomized controlled trials involving 859 patients. After an endoscopy, the patients were randomized to receive either oral or intravenous PPI. Most of the patients had “high-risk” peptic ulcers (active bleeding, a visible vessel, an adherent clot). The PPI dose and frequency varied between the studies. Re-bleeding rates were no different between the oral and intravenous route at 72 hours (2.4% vs 5.1%; P = .26), 7 days (5.6% vs 6.8%; P =.68), or 30 days (7.9% vs 8.8%; P = .62). There was also no difference in 30-day mortality (2.1% vs 2.4%; P = .88), and the length of stay was the same in both groups. Side effects were not reported.

Cautions

This systematic review and meta-analysis included multiple heterogeneous small studies of moderate quality. A large number of patients were excluded, increasing the risk of a selection bias.

Implications

There is no clear indication for intravenous PPI in the treatment of bleeding peptic ulcers following an endoscopy. Converting to oral PPI is equivalent to intravenous and is a safe, effective, and cost-saving option for patients with bleeding peptic ulcers.

1. Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Prins MH, et al. Prevalence of pulmonary embolism among patients hospitalized for syncope. N Engl J Med. 2016; 375(16):1524-1531. PubMed

2. Russo RJ, Costa HS, Silva PD, et al. Assessing the risks associated with MRI in patients with a pacemaker or defibrillator. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(8):755-764. PubMed

3. Linsenmeyer K, Gupta K, Strymish JM, Dhanani M, Brecher SM, Breu AC. Culture if spikes? Indications and yield of blood cultures in hospitalized medical patients. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(5):336-340. PubMed

4. Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Incidence of and risk factors for chronic opioid use among opioid-naive patients in the postoperative period. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1286-1293. PubMed

5. Pickering JW, Than MP, Cullen L, et al. Rapid rule-out of acute myocardial infarction with a single high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T measurement below the limit of detection: A collaborative meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(10):715-724. PubMed

6. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, Jaffe AS, Apple FS, Galvani M, et al; Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007;116:2634-2653. PubMed

7. Aleva FE, Voets LWLM, Simons SO, de Mast Q, van der Ven AJAM, Heijdra YF. Prevalence and localization of pulmonary embolism in unexplained acute exacerbations of COPD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2017; 151(3):544-554. PubMed

8. Rizkallah J, Man SFP, Sin DD. Prevalence of pulmonary embolism in acute exacerbations of COPD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2009;135(3):786-793. PubMed

9. Merel SE, McKinney CM, Ufkes P, Kwan AC, White AA. Sitting at patients’ bedsides may improve patients’ perceptions of physician communication skills. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):865-868. PubMed

10. Kahn MW. Etiquette-based medicine. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):1988-1989. PubMed

11. Uranga A, España PP, Bilbao A, et al. Duration of antibiotic treatment in community-acquired pneumonia: A multicenter randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1257-1265. PubMed

12. Jian Z, Li H, Race NS, Ma T, Jin H, Yin Z. Is the era of intravenous proton pump inhibitors coming to an end in patients with bleeding peptic ulcers? Meta-analysis of the published literature. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82(3):880-889. PubMed

ESSENTIAL PUBLICATIONS

Prevalence of Pulmonary Embolism among Patients Hospitalized for Syncope. Prandoni P et al. New England Journal of Medicine, 2016;375(16):1524-31.1

Background

Pulmonary embolism (PE), a potentially fatal disease, is rarely considered as a likely cause of syncope. To determine the prevalence of PE among patients presenting with their first episode of syncope, the authors performed a systematic workup for pulmonary embolism in adult patients admitted for syncope at 11 hospitals in Italy.

Findings

Of the 2584 patients who presented to the emergency department (ED) with syncope during the study, 560 patients were admitted and met the inclusion criteria. A modified Wells Score was applied, and a D-dimer was measured on every hospitalized patient. Those with a high pretest probability, a Wells Score of 4.0 or higher, or a positive D-dimer underwent further testing for pulmonary embolism by a CT scan, a ventilation perfusion scan, or an autopsy. Ninety-seven of the 560 patients admitted to the hospital for syncope were found to have a PE (17%). One in

Cautions

Nearly 72% of the patients with common explanations for syncope, such as vasovagal, drug-induced, or volume depletion, were discharged from the ED and not included in the study. The authors focused on the prevalence of PE. The causation between PE and syncope is not clear in each of the patients. Of the patients’ diagnosis by a CT, only 67% of the PEs were found to be in a main pulmonary artery or lobar artery. The other 33% were segmental or subsegmental. Of those diagnosed by a ventilation perfusion scan, 50% of the patients had 25% or more of the area of both lungs involved. The other 50% involved less than 25% of the area of both lungs. Also, it is important to note that 75% of the patients admitted to the hospital in this study were 70 years of age or older.

Implications

After common diagnoses are ruled out, it is important to consider pulmonary embolism in patients hospitalized with syncope. Providers should calculate a Wells Score and measure a D-dimer to guide the decision making.

Assessing the Risks Associated with MRI in Patients with a Pacemaker or Defibrillator. Russo RJ et al. New England Journal of Medicine, 2017;376(8):755-64.2

Background

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in patients with implantable cardiac devices is considered a safety risk due to the potential of cardiac lead heating and subsequent myocardial injury or alterations of the pacing properties. Although manufacturers have developed “MRI-conditional” devices designed to reduce these risks, still 2 million people in the United States and 6 million people worldwide have “non–MRI-conditional” devices. The authors evaluated the event rates in patients with “non-MRI-conditional” devices undergoing an MRI.

Findings

The authors prospectively followed up 1500 adults with cardiac devices placed since 2001 who received nonthoracic MRIs according to a specific protocol available in the supplemental materials published with this article in the New England Journal of Medicine. Of the 1000 patients with pacemakers only, they observed 5 atrial arrhythmias and 6 electrical resets. Of the 500 patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs), they observed 1 atrial arrhythmia and 1 generator failure (although this case had deviated from the protocol). All of the atrial arrhythmias were self-terminating. No deaths, lead failure requiring an immediate replacement, a loss of capture, or ventricular arrhythmias were observed.

Cautions

Patients who were pacing dependent were excluded. No devices implanted before 2001 were included in the study, and the MRIs performed were only 1.5 Tesla (a lower field strength than the also available 3 Tesla MRIs).

Implications

It is safe to proceed with 1.5 Tesla nonthoracic MRIs in patients, following the protocol outlined in this article, with non–MRI conditional cardiac devices implanted since 2001.

Culture If Spikes? Indications and Yield of Blood Cultures in Hospitalized Medical Patients. Linsenmeyer K et al. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 2016;11(5):336-40.3

Background

Blood cultures are frequently drawn for the evaluation of an inpatient fever. This “culture if spikes” approach may lead to unnecessary testing and false positive results. In this study, the authors evaluated rates of true positive and false positive blood cultures in the setting of an inpatient fever.

Findings

The patients hospitalized on the general medicine or cardiology floors at a Veterans Affairs teaching hospital were prospectively followed over 7 months. A total of 576 blood cultures were ordered among 323 unique patients. The patients were older (average age of 70 years) and predominantly male (94%). The true-positive rate for cultures, determined by a consensus among the microbiology and infectious disease departments based on a review of clinical and laboratory data, was 3.6% compared with a false-positive rate of 2.3%. The clinical characteristics associated with a higher likelihood of a true positive included: the indication for a culture as a follow-up from a previous culture (likelihood ratio [LR] 3.4), a working diagnosis of bacteremia or endocarditis (LR 3.7), and the constellation of fever and leukocytosis in a patient who has not been on antibiotics (LR 5.6).

Cautions

This study was performed at a single center with patients in the medicine and cardiology services, and thus, the data is representative of clinical practice patterns specific to that site.

Implications

Reflexive ordering of blood cultures for inpatient fever is of a low yield with a false-positive rate that approximates the true positive rate. A large number of patients are tested unnecessarily, and for those with positive tests, physicians are as likely to be misled as they are certain to truly identify a pathogen. The positive predictive value of blood cultures is improved when drawn on patients who are not on antibiotics and when the patient has a specific diagnosis, such as pneumonia, previous bacteremia, or suspected endocarditis.

Incidence of and Risk Factors for Chronic Opioid Use among Opioid-Naive Patients in the Postoperative Period. Sun EC et al. JAMA Internal Medicine, 2016;176(9):1286-93.4

Background

Each day in the United States, 650,000 opioid prescriptions are filled, and 78 people suffer an opiate-related death. Opioids are frequently prescribed for inpatient management of postoperative pain. In this study, authors compared the development of chronic opioid use between patients who had undergone surgery and those who had not.

Findings

This was a retrospective analysis of a nationwide insurance claims database. A total of 641,941 opioid-naive patients underwent 1 of 11 designated surgeries in the study period and were compared with 18,011,137 opioid-naive patients who did not undergo surgery. Chronic opioid use was defined as the filling of 10 or more prescriptions or receiving more than a 120-day supply between 90 and 365 days postoperatively (or following the assigned faux surgical date in those not having surgery). This was observed in a small proportion of the surgical patients (less than 0.5%). However, several procedures were associated with the increased odds of postoperative chronic opioid use, including a simple mastectomy (Odds ratio [OR] 2.65), a cesarean delivery (OR 1.28), an open appendectomy (OR 1.69), an open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy (ORs 3.60 and 1.62, respectively), and a total hip and total knee arthroplasty (ORs 2.52 and 5.10, respectively). Also, male sex, age greater than 50 years, preoperative benzodiazepines or antidepressants, and a history of drug abuse were associated with increased odds.

Cautions

This study was limited by the claims-based data and that the nonsurgical population was inherently different from the surgical population in ways that could lead to confounding.

Implications

In perioperative care, there is a need to focus on multimodal approaches to pain and to implement opioid reducing and sparing strategies that might include options such as acetaminophen, NSAIDs, neuropathic pain medications, and Lidocaine patches. Moreover, at discharge, careful consideration should be given to the quantity and duration of the postoperative opioids.

Rapid Rule-out of Acute Myocardial Infarction with a Single High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin T Measurement below the Limit of Detection: A Collaborative Meta-Analysis. Pickering JW et al. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2017;166:715-24.5

Background

High-sensitivity cardiac troponin testing (hs-cTnT) is now available in the United States. Studies have found that these can play a significant role in a rapid rule-out of acute myocardial infarction (AMI).

Findings

In this meta-analysis, the authors identified 11 studies with 9241 participants that prospectively evaluated patients presenting to the emergency department (ED) with chest pain, underwent an ECG, and had hs-cTnT drawn. A total of 30% of the patients were classified as low risk with negative hs-cTnT and negative ECG (defined as no ST changes or T-wave inversions indicative of ischemia). Among the low risk patients, only 14 of the 2825 (0.5%) had AMI according to the Global Task Forces definition.6 Seven of these were in patients with hs-cTnT drawn within 3 hours of a chest pain onset. The pooled negative predictive value was 99.0% (CI 93.8%–99.8%).

Cautions

The heterogeneity between the studies in this meta-analysis, especially in the exclusion criteria, warrants careful consideration when being implemented in new settings. A more sensitive test will result in more positive troponins due to different limits of detection. Thus, medical teams and institutions need to plan accordingly. Caution should be taken for any patient presenting within 3 hours of a chest pain onset.

Implications

Rapid rule-out protocols—which include clinical evaluation, a negative ECG, and a negative high-sensitivity cardiac troponin—identify a large proportion of low-risk patients who are unlikely to have a true AMI.

Prevalence and Localization of Pulmonary Embolism in Unexplained Acute Exacerbations of COPD: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Aleva FE et al. Chest, 2017;151(3):544-54.7

Background

Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AE-COPD) are frequent. In up to 30%, no clear trigger is found. Previous studies suggested that 1 in 4 of these patients may have a pulmonary embolus (PE).7 This study reviewed the literature and meta-data to describe the prevalence, the embolism location, and the clinical predictors of PE among patients with unexplained AE-COPD.

Findings

A systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis identified 7 studies with 880 patients. In the pooled analysis, 16% had PE (range: 3%–29%). Of the 120 patients with PE, two-thirds were in lobar or larger arteries and one-third in segmental or smaller. Pleuritic chest pain and signs of cardiac compromise (hypotension, syncope, and right-sided heart failure) were associated with PE.

Cautions

This study was heterogeneous leading to a broad confidence interval for prevalence ranging from 8%–25%. Given the frequency of AE-COPD with no identified trigger, physicians need to attend to risks of repeat radiation exposure when considering an evaluation for PE.

Implications

One in 6 patients with unexplained AE-COPD was found to have PE; the odds were greater in those with pleuritic chest pain or signs of cardiac compromise. In patients with AE-COPD with an unclear trigger, the providers should consider an evaluation for PE by using a clinical prediction rule and/or a D-dimer.

Sitting at Patients’ Bedsides May Improve Patients’ Perceptions of Physician Communication Skills. Merel SE et al. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 2016;11(12):865-8.9

Background

Sitting at a patient’s bedside in the inpatient setting is considered a best practice, yet it has not been widely adopted. The authors conducted a cluster-randomized trial of physicians on a single 28-bed hospitalist only run unit where physicians were assigned to sitting or standing for the first 3 days of a 7-day workweek assignment. New admissions or transfers to the unit were considered eligible for the study.

Findings

Sixteen hospitalists saw on an average 13 patients daily during the study (a total of 159 patients were included in the analysis after 52 patients were excluded or declined to participate). The hospitalists were 69% female, and 81% had been in practice 3 years or less. The average time spent in the patient’s room was 12:00 minutes while seated and 12:10 minutes while standing. There was no difference in the patients’ perception of the amount of time spent—the patients overestimated this by 4 minutes in both groups. Sitting was associated with higher ratings for “listening carefully” and “explaining things in a way that was easy to understand.” There was no difference in ratings on the physicians interrupting the patient when talking or in treating patients with courtesy and respect.

Cautions

The study had a small sample size, was limited to English-speaking patients, and was a single-site study. It involved only attending-level physicians and did not involve nonphysician team members. The physicians were not blinded and were aware that the interactions were monitored, perhaps creating a Hawthorne effect. The analysis did not control for other factors such as the severity of the illness, the number of consultants used, or the degree of health literacy.

Implications

This study supports an important best practice highlighted in etiquette-based medicine 10: sitting at the bedside provided a benefit in the patient’s perception of communication by physicians without a negative effect on the physician’s workflow.

The Duration of Antibiotic Treatment in Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Multi-Center Randomized Clinical Trial. Uranga A et al. JAMA Intern Medicine, 2016;176(9):1257-65.11

Background

The optimal duration of treatment for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is unclear; a growing body of evidence suggests shorter and longer durations may be equivalent.

Findings

At 4 hospitals in Spain, 312 adults with a mean age of 65 years and a diagnosis of CAP (non-ICU) were randomized to a short (5 days) versus a long (provider discretion) course of antibiotics. In the short-course group, the antibiotics were stopped after 5 days if the body temperature had been 37.8o C or less for 48 hours, and no more than 1 sign of clinical instability was present (SBP < 90 mmHg, HR >100/min, RR > 24/min, O2Sat < 90%). The median number of antibiotic days was 5 for the short-course group and 10 for the long-course group (P < .01). There was no difference in the resolution of pneumonia symptoms at 10 days or 30 days or in 30-day mortality. There were no differences in in-hospital side effects. However, 30-day readmissions were higher in the long-course group compared with the short-course group (6.6% vs 1.4%; P = .02). The results were similar across all of the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) classes.

Cautions

Most of the patients were not severely ill (~60% PSI I-III), the level of comorbid disease was low, and nearly 80% of the patients received fluoroquinolone. There was a significant cross over with 30% of patients assigned to the short-course group receiving antibiotics for more than 5 days.

Implications

Inpatient providers should aim to treat patients with community-acquired pneumonia (regardless of the severity of the illness) for 5 days. At day 5, if the patient is afebrile and has no signs of clinical instability, clinicians should be comfortable stopping antibiotics.

Is the Era of Intravenous Proton Pump Inhibitors Coming to an End in Patients with Bleeding Peptic Ulcers? A Meta-Analysis of the Published Literature. Jian Z et al. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 2016;82(3):880-9.12

Background

Guidelines recommend intravenous proton pump inhibitors (PPI) after an endoscopy for patients with a bleeding peptic ulcer. Yet, acid suppression with oral PPI is deemed equivalent to the intravenous route.

Findings

This systematic review and meta-analysis identified 7 randomized controlled trials involving 859 patients. After an endoscopy, the patients were randomized to receive either oral or intravenous PPI. Most of the patients had “high-risk” peptic ulcers (active bleeding, a visible vessel, an adherent clot). The PPI dose and frequency varied between the studies. Re-bleeding rates were no different between the oral and intravenous route at 72 hours (2.4% vs 5.1%; P = .26), 7 days (5.6% vs 6.8%; P =.68), or 30 days (7.9% vs 8.8%; P = .62). There was also no difference in 30-day mortality (2.1% vs 2.4%; P = .88), and the length of stay was the same in both groups. Side effects were not reported.

Cautions

This systematic review and meta-analysis included multiple heterogeneous small studies of moderate quality. A large number of patients were excluded, increasing the risk of a selection bias.

Implications

There is no clear indication for intravenous PPI in the treatment of bleeding peptic ulcers following an endoscopy. Converting to oral PPI is equivalent to intravenous and is a safe, effective, and cost-saving option for patients with bleeding peptic ulcers.

ESSENTIAL PUBLICATIONS

Prevalence of Pulmonary Embolism among Patients Hospitalized for Syncope. Prandoni P et al. New England Journal of Medicine, 2016;375(16):1524-31.1

Background

Pulmonary embolism (PE), a potentially fatal disease, is rarely considered as a likely cause of syncope. To determine the prevalence of PE among patients presenting with their first episode of syncope, the authors performed a systematic workup for pulmonary embolism in adult patients admitted for syncope at 11 hospitals in Italy.

Findings

Of the 2584 patients who presented to the emergency department (ED) with syncope during the study, 560 patients were admitted and met the inclusion criteria. A modified Wells Score was applied, and a D-dimer was measured on every hospitalized patient. Those with a high pretest probability, a Wells Score of 4.0 or higher, or a positive D-dimer underwent further testing for pulmonary embolism by a CT scan, a ventilation perfusion scan, or an autopsy. Ninety-seven of the 560 patients admitted to the hospital for syncope were found to have a PE (17%). One in

Cautions

Nearly 72% of the patients with common explanations for syncope, such as vasovagal, drug-induced, or volume depletion, were discharged from the ED and not included in the study. The authors focused on the prevalence of PE. The causation between PE and syncope is not clear in each of the patients. Of the patients’ diagnosis by a CT, only 67% of the PEs were found to be in a main pulmonary artery or lobar artery. The other 33% were segmental or subsegmental. Of those diagnosed by a ventilation perfusion scan, 50% of the patients had 25% or more of the area of both lungs involved. The other 50% involved less than 25% of the area of both lungs. Also, it is important to note that 75% of the patients admitted to the hospital in this study were 70 years of age or older.

Implications

After common diagnoses are ruled out, it is important to consider pulmonary embolism in patients hospitalized with syncope. Providers should calculate a Wells Score and measure a D-dimer to guide the decision making.

Assessing the Risks Associated with MRI in Patients with a Pacemaker or Defibrillator. Russo RJ et al. New England Journal of Medicine, 2017;376(8):755-64.2

Background

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in patients with implantable cardiac devices is considered a safety risk due to the potential of cardiac lead heating and subsequent myocardial injury or alterations of the pacing properties. Although manufacturers have developed “MRI-conditional” devices designed to reduce these risks, still 2 million people in the United States and 6 million people worldwide have “non–MRI-conditional” devices. The authors evaluated the event rates in patients with “non-MRI-conditional” devices undergoing an MRI.

Findings

The authors prospectively followed up 1500 adults with cardiac devices placed since 2001 who received nonthoracic MRIs according to a specific protocol available in the supplemental materials published with this article in the New England Journal of Medicine. Of the 1000 patients with pacemakers only, they observed 5 atrial arrhythmias and 6 electrical resets. Of the 500 patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs), they observed 1 atrial arrhythmia and 1 generator failure (although this case had deviated from the protocol). All of the atrial arrhythmias were self-terminating. No deaths, lead failure requiring an immediate replacement, a loss of capture, or ventricular arrhythmias were observed.

Cautions

Patients who were pacing dependent were excluded. No devices implanted before 2001 were included in the study, and the MRIs performed were only 1.5 Tesla (a lower field strength than the also available 3 Tesla MRIs).

Implications

It is safe to proceed with 1.5 Tesla nonthoracic MRIs in patients, following the protocol outlined in this article, with non–MRI conditional cardiac devices implanted since 2001.

Culture If Spikes? Indications and Yield of Blood Cultures in Hospitalized Medical Patients. Linsenmeyer K et al. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 2016;11(5):336-40.3

Background

Blood cultures are frequently drawn for the evaluation of an inpatient fever. This “culture if spikes” approach may lead to unnecessary testing and false positive results. In this study, the authors evaluated rates of true positive and false positive blood cultures in the setting of an inpatient fever.

Findings

The patients hospitalized on the general medicine or cardiology floors at a Veterans Affairs teaching hospital were prospectively followed over 7 months. A total of 576 blood cultures were ordered among 323 unique patients. The patients were older (average age of 70 years) and predominantly male (94%). The true-positive rate for cultures, determined by a consensus among the microbiology and infectious disease departments based on a review of clinical and laboratory data, was 3.6% compared with a false-positive rate of 2.3%. The clinical characteristics associated with a higher likelihood of a true positive included: the indication for a culture as a follow-up from a previous culture (likelihood ratio [LR] 3.4), a working diagnosis of bacteremia or endocarditis (LR 3.7), and the constellation of fever and leukocytosis in a patient who has not been on antibiotics (LR 5.6).

Cautions

This study was performed at a single center with patients in the medicine and cardiology services, and thus, the data is representative of clinical practice patterns specific to that site.

Implications

Reflexive ordering of blood cultures for inpatient fever is of a low yield with a false-positive rate that approximates the true positive rate. A large number of patients are tested unnecessarily, and for those with positive tests, physicians are as likely to be misled as they are certain to truly identify a pathogen. The positive predictive value of blood cultures is improved when drawn on patients who are not on antibiotics and when the patient has a specific diagnosis, such as pneumonia, previous bacteremia, or suspected endocarditis.

Incidence of and Risk Factors for Chronic Opioid Use among Opioid-Naive Patients in the Postoperative Period. Sun EC et al. JAMA Internal Medicine, 2016;176(9):1286-93.4

Background

Each day in the United States, 650,000 opioid prescriptions are filled, and 78 people suffer an opiate-related death. Opioids are frequently prescribed for inpatient management of postoperative pain. In this study, authors compared the development of chronic opioid use between patients who had undergone surgery and those who had not.

Findings

This was a retrospective analysis of a nationwide insurance claims database. A total of 641,941 opioid-naive patients underwent 1 of 11 designated surgeries in the study period and were compared with 18,011,137 opioid-naive patients who did not undergo surgery. Chronic opioid use was defined as the filling of 10 or more prescriptions or receiving more than a 120-day supply between 90 and 365 days postoperatively (or following the assigned faux surgical date in those not having surgery). This was observed in a small proportion of the surgical patients (less than 0.5%). However, several procedures were associated with the increased odds of postoperative chronic opioid use, including a simple mastectomy (Odds ratio [OR] 2.65), a cesarean delivery (OR 1.28), an open appendectomy (OR 1.69), an open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy (ORs 3.60 and 1.62, respectively), and a total hip and total knee arthroplasty (ORs 2.52 and 5.10, respectively). Also, male sex, age greater than 50 years, preoperative benzodiazepines or antidepressants, and a history of drug abuse were associated with increased odds.

Cautions

This study was limited by the claims-based data and that the nonsurgical population was inherently different from the surgical population in ways that could lead to confounding.

Implications

In perioperative care, there is a need to focus on multimodal approaches to pain and to implement opioid reducing and sparing strategies that might include options such as acetaminophen, NSAIDs, neuropathic pain medications, and Lidocaine patches. Moreover, at discharge, careful consideration should be given to the quantity and duration of the postoperative opioids.

Rapid Rule-out of Acute Myocardial Infarction with a Single High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin T Measurement below the Limit of Detection: A Collaborative Meta-Analysis. Pickering JW et al. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2017;166:715-24.5

Background

High-sensitivity cardiac troponin testing (hs-cTnT) is now available in the United States. Studies have found that these can play a significant role in a rapid rule-out of acute myocardial infarction (AMI).

Findings

In this meta-analysis, the authors identified 11 studies with 9241 participants that prospectively evaluated patients presenting to the emergency department (ED) with chest pain, underwent an ECG, and had hs-cTnT drawn. A total of 30% of the patients were classified as low risk with negative hs-cTnT and negative ECG (defined as no ST changes or T-wave inversions indicative of ischemia). Among the low risk patients, only 14 of the 2825 (0.5%) had AMI according to the Global Task Forces definition.6 Seven of these were in patients with hs-cTnT drawn within 3 hours of a chest pain onset. The pooled negative predictive value was 99.0% (CI 93.8%–99.8%).

Cautions

The heterogeneity between the studies in this meta-analysis, especially in the exclusion criteria, warrants careful consideration when being implemented in new settings. A more sensitive test will result in more positive troponins due to different limits of detection. Thus, medical teams and institutions need to plan accordingly. Caution should be taken for any patient presenting within 3 hours of a chest pain onset.

Implications

Rapid rule-out protocols—which include clinical evaluation, a negative ECG, and a negative high-sensitivity cardiac troponin—identify a large proportion of low-risk patients who are unlikely to have a true AMI.

Prevalence and Localization of Pulmonary Embolism in Unexplained Acute Exacerbations of COPD: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Aleva FE et al. Chest, 2017;151(3):544-54.7

Background

Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AE-COPD) are frequent. In up to 30%, no clear trigger is found. Previous studies suggested that 1 in 4 of these patients may have a pulmonary embolus (PE).7 This study reviewed the literature and meta-data to describe the prevalence, the embolism location, and the clinical predictors of PE among patients with unexplained AE-COPD.

Findings

A systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis identified 7 studies with 880 patients. In the pooled analysis, 16% had PE (range: 3%–29%). Of the 120 patients with PE, two-thirds were in lobar or larger arteries and one-third in segmental or smaller. Pleuritic chest pain and signs of cardiac compromise (hypotension, syncope, and right-sided heart failure) were associated with PE.

Cautions

This study was heterogeneous leading to a broad confidence interval for prevalence ranging from 8%–25%. Given the frequency of AE-COPD with no identified trigger, physicians need to attend to risks of repeat radiation exposure when considering an evaluation for PE.

Implications

One in 6 patients with unexplained AE-COPD was found to have PE; the odds were greater in those with pleuritic chest pain or signs of cardiac compromise. In patients with AE-COPD with an unclear trigger, the providers should consider an evaluation for PE by using a clinical prediction rule and/or a D-dimer.

Sitting at Patients’ Bedsides May Improve Patients’ Perceptions of Physician Communication Skills. Merel SE et al. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 2016;11(12):865-8.9

Background

Sitting at a patient’s bedside in the inpatient setting is considered a best practice, yet it has not been widely adopted. The authors conducted a cluster-randomized trial of physicians on a single 28-bed hospitalist only run unit where physicians were assigned to sitting or standing for the first 3 days of a 7-day workweek assignment. New admissions or transfers to the unit were considered eligible for the study.

Findings

Sixteen hospitalists saw on an average 13 patients daily during the study (a total of 159 patients were included in the analysis after 52 patients were excluded or declined to participate). The hospitalists were 69% female, and 81% had been in practice 3 years or less. The average time spent in the patient’s room was 12:00 minutes while seated and 12:10 minutes while standing. There was no difference in the patients’ perception of the amount of time spent—the patients overestimated this by 4 minutes in both groups. Sitting was associated with higher ratings for “listening carefully” and “explaining things in a way that was easy to understand.” There was no difference in ratings on the physicians interrupting the patient when talking or in treating patients with courtesy and respect.

Cautions

The study had a small sample size, was limited to English-speaking patients, and was a single-site study. It involved only attending-level physicians and did not involve nonphysician team members. The physicians were not blinded and were aware that the interactions were monitored, perhaps creating a Hawthorne effect. The analysis did not control for other factors such as the severity of the illness, the number of consultants used, or the degree of health literacy.

Implications

This study supports an important best practice highlighted in etiquette-based medicine 10: sitting at the bedside provided a benefit in the patient’s perception of communication by physicians without a negative effect on the physician’s workflow.

The Duration of Antibiotic Treatment in Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Multi-Center Randomized Clinical Trial. Uranga A et al. JAMA Intern Medicine, 2016;176(9):1257-65.11

Background

The optimal duration of treatment for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is unclear; a growing body of evidence suggests shorter and longer durations may be equivalent.

Findings

At 4 hospitals in Spain, 312 adults with a mean age of 65 years and a diagnosis of CAP (non-ICU) were randomized to a short (5 days) versus a long (provider discretion) course of antibiotics. In the short-course group, the antibiotics were stopped after 5 days if the body temperature had been 37.8o C or less for 48 hours, and no more than 1 sign of clinical instability was present (SBP < 90 mmHg, HR >100/min, RR > 24/min, O2Sat < 90%). The median number of antibiotic days was 5 for the short-course group and 10 for the long-course group (P < .01). There was no difference in the resolution of pneumonia symptoms at 10 days or 30 days or in 30-day mortality. There were no differences in in-hospital side effects. However, 30-day readmissions were higher in the long-course group compared with the short-course group (6.6% vs 1.4%; P = .02). The results were similar across all of the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) classes.

Cautions

Most of the patients were not severely ill (~60% PSI I-III), the level of comorbid disease was low, and nearly 80% of the patients received fluoroquinolone. There was a significant cross over with 30% of patients assigned to the short-course group receiving antibiotics for more than 5 days.

Implications

Inpatient providers should aim to treat patients with community-acquired pneumonia (regardless of the severity of the illness) for 5 days. At day 5, if the patient is afebrile and has no signs of clinical instability, clinicians should be comfortable stopping antibiotics.

Is the Era of Intravenous Proton Pump Inhibitors Coming to an End in Patients with Bleeding Peptic Ulcers? A Meta-Analysis of the Published Literature. Jian Z et al. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 2016;82(3):880-9.12

Background

Guidelines recommend intravenous proton pump inhibitors (PPI) after an endoscopy for patients with a bleeding peptic ulcer. Yet, acid suppression with oral PPI is deemed equivalent to the intravenous route.

Findings

This systematic review and meta-analysis identified 7 randomized controlled trials involving 859 patients. After an endoscopy, the patients were randomized to receive either oral or intravenous PPI. Most of the patients had “high-risk” peptic ulcers (active bleeding, a visible vessel, an adherent clot). The PPI dose and frequency varied between the studies. Re-bleeding rates were no different between the oral and intravenous route at 72 hours (2.4% vs 5.1%; P = .26), 7 days (5.6% vs 6.8%; P =.68), or 30 days (7.9% vs 8.8%; P = .62). There was also no difference in 30-day mortality (2.1% vs 2.4%; P = .88), and the length of stay was the same in both groups. Side effects were not reported.

Cautions

This systematic review and meta-analysis included multiple heterogeneous small studies of moderate quality. A large number of patients were excluded, increasing the risk of a selection bias.

Implications

There is no clear indication for intravenous PPI in the treatment of bleeding peptic ulcers following an endoscopy. Converting to oral PPI is equivalent to intravenous and is a safe, effective, and cost-saving option for patients with bleeding peptic ulcers.

1. Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Prins MH, et al. Prevalence of pulmonary embolism among patients hospitalized for syncope. N Engl J Med. 2016; 375(16):1524-1531. PubMed

2. Russo RJ, Costa HS, Silva PD, et al. Assessing the risks associated with MRI in patients with a pacemaker or defibrillator. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(8):755-764. PubMed

3. Linsenmeyer K, Gupta K, Strymish JM, Dhanani M, Brecher SM, Breu AC. Culture if spikes? Indications and yield of blood cultures in hospitalized medical patients. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(5):336-340. PubMed

4. Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Incidence of and risk factors for chronic opioid use among opioid-naive patients in the postoperative period. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1286-1293. PubMed

5. Pickering JW, Than MP, Cullen L, et al. Rapid rule-out of acute myocardial infarction with a single high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T measurement below the limit of detection: A collaborative meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(10):715-724. PubMed

6. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, Jaffe AS, Apple FS, Galvani M, et al; Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007;116:2634-2653. PubMed

7. Aleva FE, Voets LWLM, Simons SO, de Mast Q, van der Ven AJAM, Heijdra YF. Prevalence and localization of pulmonary embolism in unexplained acute exacerbations of COPD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2017; 151(3):544-554. PubMed

8. Rizkallah J, Man SFP, Sin DD. Prevalence of pulmonary embolism in acute exacerbations of COPD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2009;135(3):786-793. PubMed

9. Merel SE, McKinney CM, Ufkes P, Kwan AC, White AA. Sitting at patients’ bedsides may improve patients’ perceptions of physician communication skills. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):865-868. PubMed

10. Kahn MW. Etiquette-based medicine. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):1988-1989. PubMed

11. Uranga A, España PP, Bilbao A, et al. Duration of antibiotic treatment in community-acquired pneumonia: A multicenter randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1257-1265. PubMed

12. Jian Z, Li H, Race NS, Ma T, Jin H, Yin Z. Is the era of intravenous proton pump inhibitors coming to an end in patients with bleeding peptic ulcers? Meta-analysis of the published literature. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82(3):880-889. PubMed

1. Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Prins MH, et al. Prevalence of pulmonary embolism among patients hospitalized for syncope. N Engl J Med. 2016; 375(16):1524-1531. PubMed

2. Russo RJ, Costa HS, Silva PD, et al. Assessing the risks associated with MRI in patients with a pacemaker or defibrillator. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(8):755-764. PubMed

3. Linsenmeyer K, Gupta K, Strymish JM, Dhanani M, Brecher SM, Breu AC. Culture if spikes? Indications and yield of blood cultures in hospitalized medical patients. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(5):336-340. PubMed

4. Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Incidence of and risk factors for chronic opioid use among opioid-naive patients in the postoperative period. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1286-1293. PubMed

5. Pickering JW, Than MP, Cullen L, et al. Rapid rule-out of acute myocardial infarction with a single high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T measurement below the limit of detection: A collaborative meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(10):715-724. PubMed

6. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, Jaffe AS, Apple FS, Galvani M, et al; Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007;116:2634-2653. PubMed

7. Aleva FE, Voets LWLM, Simons SO, de Mast Q, van der Ven AJAM, Heijdra YF. Prevalence and localization of pulmonary embolism in unexplained acute exacerbations of COPD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2017; 151(3):544-554. PubMed

8. Rizkallah J, Man SFP, Sin DD. Prevalence of pulmonary embolism in acute exacerbations of COPD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2009;135(3):786-793. PubMed

9. Merel SE, McKinney CM, Ufkes P, Kwan AC, White AA. Sitting at patients’ bedsides may improve patients’ perceptions of physician communication skills. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):865-868. PubMed

10. Kahn MW. Etiquette-based medicine. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):1988-1989. PubMed

11. Uranga A, España PP, Bilbao A, et al. Duration of antibiotic treatment in community-acquired pneumonia: A multicenter randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1257-1265. PubMed

12. Jian Z, Li H, Race NS, Ma T, Jin H, Yin Z. Is the era of intravenous proton pump inhibitors coming to an end in patients with bleeding peptic ulcers? Meta-analysis of the published literature. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82(3):880-889. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Student perceptions of high-value care education in internal medicine clerkships

During internal medicine (IM) clerkships, course directors are responsible for ensuring that medical students attain basic competency in patient management through use of risk–benefit, cost–benefit, and evidence-based considerations.1 However, the students’ primary teachers—IM residents and attendings—consistently role-model high-value care (HVC) perhaps only half the time.2 The inconsistency may have a few sources, including unawareness of the costs of tests and treatments ordered and little formal training in HVC.3-5 In addition, the environment at some academic institutions may reward learners for performing tests that may be unnecessary.6

We conducted a study to assess medical students’ perceptions of unnecessary testing and the adequacy–inadequacy of HVC instruction, as well as their observations of behavior that may hinder the practice of HVC during the IM clerkship.

METHODS

When students completed their third-year IM clerkships at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine, and the Tulane University School of Medicine, we sent them a recruitment email asking them to complete an anonymous survey regarding their clerkship experiences with HVC. The clerkships’ directors, who collaborated on survey development, searched the literature to quantify behavior thought to decrease the practice of HVC. The survey was tested several times with different learners and faculty to increase response process validity.

The SurveyMonkey online platform was used to administer the survey. Students were given 1 week after the end of their clerkship to complete the survey. Data were collected for the period October 2013 to December 2014. Each student was offered a $10 gift certificate for survey completion. Each institution received exempt approval from its institutional review board.

Survey respondents were divided into those who perceived HVC education as adequate and those who perceived it as inadequate. Chi-square tests were performed with Stata Version 12 (College Station, TX) to determine whether a student’s perception of HVC education being adequate or inadequate was significantly associated with the other survey questions.

RESULTS

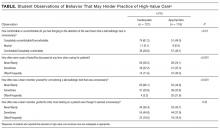

Of 577 eligible students, 307 (53%) completed the survey. About 83% of the respondents reported noticing the ordering of laboratory or radiologic tests they considered unnecessary, and a majority (81%) of those students noticed this activity at least once a week. Overall, 51% of the respondents thought their HVC education was inadequate. Significantly more of the students who perceived their HVC education as inadequate were uncomfortable bringing an unnecessary test to the attention of the ward team, rarely discussed costs, and rarely observed team members being praised for forgoing unnecessary tests (Table). Two significant associations were found: between institution attended and perceived adequacy–inadequacy of HVC education and between institution and frequency of cost discussions.

Most (78.5%) students thought an HVC curriculum should be added to the IM clerkship, and 34.5% thought the HVC curriculum should be incorporated into daily rounds. In regards to additions to the clerkship curriculum, most students wanted to round with phlebotomy (29%) or discuss costs of testing on patients (26%).

Students attributed the ordering of unnecessary tests and treatments to several factors: residents investigating “interesting diagnoses” (46%), teams practicing defensive medicine (43%), consultants making requests (40%), attendings investigating “interesting diagnoses” (27%), and patients making requests (8%).

DISCUSSION

About 51% of the students thought their HVC education was inadequate, and about 83% noticed unnecessary testing. Our study findings reaffirm those of a single-site study in which 93% of students noted unnecessary testing.7

In this study, many students perceived HVC education as inadequate and reported wanting HVC principles added to their training and an HVC curriculum incorporated into daily rounds. Students who perceived HVC education as inadequate were significantly less comfortable bringing an unnecessary test to the attention of the ward team and noticed less discussion about costs and less praise for avoiding unnecessary tests. One institution had a significantly higher proportion of students perceiving their HVC education as adequate and noticing more discussions about test costs. This institution was the only one that incorporated discussions about test costs into its curriculum during the study period—which may account for its students’ perceptions.

This study had a few limitations. First, as the survey was administered after the IM clerkships, students’ responses may have been subject to recall bias. We minimized this bias by allowing 1 week for survey completion. Second, given the 53% response rate, there may have been response bias. However, one institution’s demographics showed no significant differences between responders and nonresponders with respect to age, sex, ethnicity, or type of degree. Third, students’ understanding of what tests and treatments are necessary and unnecessary may be relatively underdeveloped, given their training level. One study found that medical students with minimal clinical experience were able to identify unnecessary tests and treatments, but this study has not been validated at other institutions.7

Efforts to increase HVC education and practice have focused on residents and attendings, but our study findings reaffirm that HVC training is much needed and wanted in undergraduate medical education. Studies are needed to test the effectiveness of HVC curricula in medical school and the ability of these curricula to give students the tools they need to practice HVC.

Disclosures

Dr. Pahwa received support from the Johns Hopkins Hospitalist Scholars Fund, and Dr. Cayea is supported by the Daniel and Jeanette Hendin Schapiro Geriatric Medical Education Center. The sponsors had no role in study design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, data analysis, or manuscript preparation. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Clerkship Directors in Internal Medicine, Society of General Internal Medicine. CDIM-SGIM Core Medicine Clerkship Curriculum Guide: A Resource for Teachers and Learners. Version 3.0. http://connect.im.org/p/cm/ld/fid=385. Published 2006. Accessed May 12, 2015.

2. Patel MS, Reed DA, Smith C, Arora VM. Role-modeling cost-conscious care—a national evaluation of perceptions of faculty at teaching hospitals in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(9):1294-1298. PubMed

3. Tek Sehgal R, Gorman P. Internal medicine physicians’ knowledge of health care charges. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(2):182-187. PubMed

4. Patel MS, Reed DA, Loertscher L, McDonald FS, Arora VM. Teaching residents to provide cost-conscious care: a national survey of residency program directors. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(3):470-472. PubMed

5. Graham JD, Potyk D, Raimi E. Hospitalists’ awareness of patient charges associated with inpatient care. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(5):295-297. PubMed

6. Detsky AS, Verma AA. A new model for medical education: celebrating restraint. JAMA. 2012;308(13):1329-1330. PubMed

7. Tartaglia KM, Kman N, Ledford C. Medical student perceptions of cost-conscious care in an internal medicine clerkship: a thematic analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(10):1491-1496. PubMed

During internal medicine (IM) clerkships, course directors are responsible for ensuring that medical students attain basic competency in patient management through use of risk–benefit, cost–benefit, and evidence-based considerations.1 However, the students’ primary teachers—IM residents and attendings—consistently role-model high-value care (HVC) perhaps only half the time.2 The inconsistency may have a few sources, including unawareness of the costs of tests and treatments ordered and little formal training in HVC.3-5 In addition, the environment at some academic institutions may reward learners for performing tests that may be unnecessary.6

We conducted a study to assess medical students’ perceptions of unnecessary testing and the adequacy–inadequacy of HVC instruction, as well as their observations of behavior that may hinder the practice of HVC during the IM clerkship.

METHODS

When students completed their third-year IM clerkships at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine, and the Tulane University School of Medicine, we sent them a recruitment email asking them to complete an anonymous survey regarding their clerkship experiences with HVC. The clerkships’ directors, who collaborated on survey development, searched the literature to quantify behavior thought to decrease the practice of HVC. The survey was tested several times with different learners and faculty to increase response process validity.

The SurveyMonkey online platform was used to administer the survey. Students were given 1 week after the end of their clerkship to complete the survey. Data were collected for the period October 2013 to December 2014. Each student was offered a $10 gift certificate for survey completion. Each institution received exempt approval from its institutional review board.

Survey respondents were divided into those who perceived HVC education as adequate and those who perceived it as inadequate. Chi-square tests were performed with Stata Version 12 (College Station, TX) to determine whether a student’s perception of HVC education being adequate or inadequate was significantly associated with the other survey questions.

RESULTS

Of 577 eligible students, 307 (53%) completed the survey. About 83% of the respondents reported noticing the ordering of laboratory or radiologic tests they considered unnecessary, and a majority (81%) of those students noticed this activity at least once a week. Overall, 51% of the respondents thought their HVC education was inadequate. Significantly more of the students who perceived their HVC education as inadequate were uncomfortable bringing an unnecessary test to the attention of the ward team, rarely discussed costs, and rarely observed team members being praised for forgoing unnecessary tests (Table). Two significant associations were found: between institution attended and perceived adequacy–inadequacy of HVC education and between institution and frequency of cost discussions.

Most (78.5%) students thought an HVC curriculum should be added to the IM clerkship, and 34.5% thought the HVC curriculum should be incorporated into daily rounds. In regards to additions to the clerkship curriculum, most students wanted to round with phlebotomy (29%) or discuss costs of testing on patients (26%).

Students attributed the ordering of unnecessary tests and treatments to several factors: residents investigating “interesting diagnoses” (46%), teams practicing defensive medicine (43%), consultants making requests (40%), attendings investigating “interesting diagnoses” (27%), and patients making requests (8%).

DISCUSSION

About 51% of the students thought their HVC education was inadequate, and about 83% noticed unnecessary testing. Our study findings reaffirm those of a single-site study in which 93% of students noted unnecessary testing.7

In this study, many students perceived HVC education as inadequate and reported wanting HVC principles added to their training and an HVC curriculum incorporated into daily rounds. Students who perceived HVC education as inadequate were significantly less comfortable bringing an unnecessary test to the attention of the ward team and noticed less discussion about costs and less praise for avoiding unnecessary tests. One institution had a significantly higher proportion of students perceiving their HVC education as adequate and noticing more discussions about test costs. This institution was the only one that incorporated discussions about test costs into its curriculum during the study period—which may account for its students’ perceptions.

This study had a few limitations. First, as the survey was administered after the IM clerkships, students’ responses may have been subject to recall bias. We minimized this bias by allowing 1 week for survey completion. Second, given the 53% response rate, there may have been response bias. However, one institution’s demographics showed no significant differences between responders and nonresponders with respect to age, sex, ethnicity, or type of degree. Third, students’ understanding of what tests and treatments are necessary and unnecessary may be relatively underdeveloped, given their training level. One study found that medical students with minimal clinical experience were able to identify unnecessary tests and treatments, but this study has not been validated at other institutions.7

Efforts to increase HVC education and practice have focused on residents and attendings, but our study findings reaffirm that HVC training is much needed and wanted in undergraduate medical education. Studies are needed to test the effectiveness of HVC curricula in medical school and the ability of these curricula to give students the tools they need to practice HVC.

Disclosures

Dr. Pahwa received support from the Johns Hopkins Hospitalist Scholars Fund, and Dr. Cayea is supported by the Daniel and Jeanette Hendin Schapiro Geriatric Medical Education Center. The sponsors had no role in study design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, data analysis, or manuscript preparation. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

During internal medicine (IM) clerkships, course directors are responsible for ensuring that medical students attain basic competency in patient management through use of risk–benefit, cost–benefit, and evidence-based considerations.1 However, the students’ primary teachers—IM residents and attendings—consistently role-model high-value care (HVC) perhaps only half the time.2 The inconsistency may have a few sources, including unawareness of the costs of tests and treatments ordered and little formal training in HVC.3-5 In addition, the environment at some academic institutions may reward learners for performing tests that may be unnecessary.6

We conducted a study to assess medical students’ perceptions of unnecessary testing and the adequacy–inadequacy of HVC instruction, as well as their observations of behavior that may hinder the practice of HVC during the IM clerkship.

METHODS

When students completed their third-year IM clerkships at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine, and the Tulane University School of Medicine, we sent them a recruitment email asking them to complete an anonymous survey regarding their clerkship experiences with HVC. The clerkships’ directors, who collaborated on survey development, searched the literature to quantify behavior thought to decrease the practice of HVC. The survey was tested several times with different learners and faculty to increase response process validity.

The SurveyMonkey online platform was used to administer the survey. Students were given 1 week after the end of their clerkship to complete the survey. Data were collected for the period October 2013 to December 2014. Each student was offered a $10 gift certificate for survey completion. Each institution received exempt approval from its institutional review board.

Survey respondents were divided into those who perceived HVC education as adequate and those who perceived it as inadequate. Chi-square tests were performed with Stata Version 12 (College Station, TX) to determine whether a student’s perception of HVC education being adequate or inadequate was significantly associated with the other survey questions.

RESULTS

Of 577 eligible students, 307 (53%) completed the survey. About 83% of the respondents reported noticing the ordering of laboratory or radiologic tests they considered unnecessary, and a majority (81%) of those students noticed this activity at least once a week. Overall, 51% of the respondents thought their HVC education was inadequate. Significantly more of the students who perceived their HVC education as inadequate were uncomfortable bringing an unnecessary test to the attention of the ward team, rarely discussed costs, and rarely observed team members being praised for forgoing unnecessary tests (Table). Two significant associations were found: between institution attended and perceived adequacy–inadequacy of HVC education and between institution and frequency of cost discussions.

Most (78.5%) students thought an HVC curriculum should be added to the IM clerkship, and 34.5% thought the HVC curriculum should be incorporated into daily rounds. In regards to additions to the clerkship curriculum, most students wanted to round with phlebotomy (29%) or discuss costs of testing on patients (26%).

Students attributed the ordering of unnecessary tests and treatments to several factors: residents investigating “interesting diagnoses” (46%), teams practicing defensive medicine (43%), consultants making requests (40%), attendings investigating “interesting diagnoses” (27%), and patients making requests (8%).

DISCUSSION

About 51% of the students thought their HVC education was inadequate, and about 83% noticed unnecessary testing. Our study findings reaffirm those of a single-site study in which 93% of students noted unnecessary testing.7

In this study, many students perceived HVC education as inadequate and reported wanting HVC principles added to their training and an HVC curriculum incorporated into daily rounds. Students who perceived HVC education as inadequate were significantly less comfortable bringing an unnecessary test to the attention of the ward team and noticed less discussion about costs and less praise for avoiding unnecessary tests. One institution had a significantly higher proportion of students perceiving their HVC education as adequate and noticing more discussions about test costs. This institution was the only one that incorporated discussions about test costs into its curriculum during the study period—which may account for its students’ perceptions.