User login

Lichen Planopilaris in a Patient Treated With Bexarotene for Lymphomatoid Papulosis

To the Editor:

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a rare chronic skin disorder characterized by recurrent, self-healing crops of papulonodular eruptions, often resembling cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.1 Oral bexarotene, a retinoid X receptor–selective retinoid, can be used to control the disease.2,3 Lichen planopilaris (LPP) is a type of cicatricial alopecia characterized by irreversible hair loss, perifollicular inflammation, and follicular hyperkeratosis, commonly affecting the scalp vertex in adults.4 We report a case of a patient with lymphomatoid papulosis who was treated with bexarotene and subsequently developed LPP. We also discuss a proposed mechanism by which bexarotene may have influenced the onset of LPP.

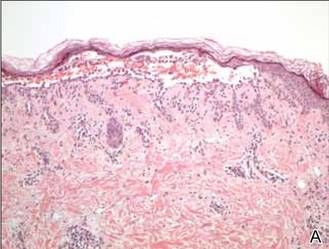

A 35-year-old woman who was previously healthy initially presented with recurrent pruritic papular eruptions on the flank, axillae, and groin of several months’ duration. The lesions appeared as 2-mm, flat-topped, violaceous papules. The patient had no known drug allergies, no medical or family history of skin disease, and was only taking 3000 mg/d of omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil). Histopathologic examination of a biopsy specimen from the inner thigh showed enlarged, atypical, dermal lymphocytes that were CD30+ (Figure 1). These findings were consistent with lymphomatoid papulosis. As she had undergone tubal ligation several years prior, she was prescribed oral bexarotene 300 mg once daily in addition to triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily, as needed. Symptoms were well controlled on this regimen.

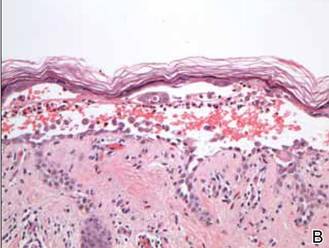

Six months later the patient returned, presenting with a new central patch of scarring alopecia on the vertex of the scalp (Figure 2). Adjacent to the area of hair loss were areas of prominent perifollicular scale that were slightly violaceous in color. Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the scalp showed dermal scarring with perifollicular lamellar fibrosis surrounded by a rim of lymphoplasmacytic inflammation (Figure 3). Sebaceous glands were found to be reduced in number. These findings were consistent with cicatricial alopecia, which was further classified as LPP in conjunction with the clinical findings. No CD30+ lymphocytes were identified in these specimens.

Baseline fasting triglycerides were 123 mg/dL (desirable: <150 mg/dL; borderline: 150–199 mg/dL; high: ≥200 mg/dL) and were stable over the first 4 months on bexarotene. After 5 months of therapy, the triglycerides increased to a high of 255 mg/dL, which corresponded with the onset of LPP. She was treated for the hypertriglyceridemia with omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil), and subsequent triglyceride levels have normalized and been stable. Her alopecia has not progressed but is persistent. She continues to have central hypothyroidism due to bexarotene and is on levothyroxine. The lymphomatoid papulosis also remains stable with no signs of progression to cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

Although the exact mechanism of LPP is not fully understood, studies have suggested that cellular lipid metabolism may be responsible for the inflammation of the pilosebaceous unit.4-11 Hyperlipidemia is the most common side effect of oral bexarotene, typically occurring within the first 2 to 4 weeks of treatment.3,12 Considering the insights into the role of lipid regulation on LPP pathogenesis, it is reasonable to suspect that the dyslipidemia caused by bexarotene may have triggered the onset of LPP in our patient. The patient’s lipid values mostly remained within reference range throughout the course of treatment, though she did have elevation of triglycerides around the onset of LPP. Dyslipidemia has been reported in patients with lichen planus but not in patients with LPP. One case-control study showed no dyslipidemia in patients with LPP, but the triglyceride levels were not tracked over time and patients had varying durations since onset of disease at presentation.9-11,13 In our case, we were fortunate to have this information, and it may suggest an interaction between lipid dysregulation and the development of LPP. It would be interesting to explore this further in a larger patient population and to evaluate if control of dyslipidemia reduces progression of disease as it appears to have done for our patient.

- Karp DL, Horn TD. Lymphomatoid papulosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:379-395; quiz 396-398.

- Krathen RA, Ward S, Duvic M. Bexarotene is a new treatment option for lymphomatoid papulosis. Dermatology. 2003;206:142-147.

- Targretin (bexarotene) capsule [package insert]. St. Petersburg, FL: Cardinal Health; 2003. http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=63656f64-e240-4855-8df9-ca1655863735. Accessed April 9, 2020.

- Assouly P, Reygagne P. Lichen planopilaris: update on diagnosis and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:3-10.

- Dogra S, Sarangal R. What’s new in cicatricial alopecia? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:576-90.

- Zheng Y, Eilertsen KJ, Ge L, et al. Scd1 is expressed in sebaceous glands and is disrupted in the asebia mouse. Nat Genet. 1999;23:268-270.

- Sundberg JP, Boggess D, Sundberg BA, et al. Asebia-2J (Scd1(ab2J)): a new allele and a model for scarring alopecia. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:2067-2075.

- Karnik P, Tekeste Z, McCormick TS, et al. Hair follicle stem cell-specific PPARgamma deletion causes scarring alopecia. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1243-157.

- López-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Rodríguez-Martínes MA. Alterations in serum lipid profile patterns in oral lichen planus: a cross-sectional study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:399-404.

- Arias-Santiago S, Buendía-Eisman A, Aneiros-Fernández J, et al. Lipid levels in patients with lichen planus: a case-control study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1398-1401.

- Dreiher J, Shapiro J, Cohen AD. Lichen planus and dyslipidaemia: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:626-629.

- de Vries-van der Weij J, de Haan W, Hu L, et al. Bexarotene induces dyslipidemia by increased very low-density lipoprotein production and cholesteryl ester transfer protein-mediated reduction of high-density lipoprotein. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2368-2375.

- Conic RRZ, Piliang M, Bergfeld W, et al. Association of lichen planopilaris with dyslipidemia. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1088-1089.

To the Editor:

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a rare chronic skin disorder characterized by recurrent, self-healing crops of papulonodular eruptions, often resembling cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.1 Oral bexarotene, a retinoid X receptor–selective retinoid, can be used to control the disease.2,3 Lichen planopilaris (LPP) is a type of cicatricial alopecia characterized by irreversible hair loss, perifollicular inflammation, and follicular hyperkeratosis, commonly affecting the scalp vertex in adults.4 We report a case of a patient with lymphomatoid papulosis who was treated with bexarotene and subsequently developed LPP. We also discuss a proposed mechanism by which bexarotene may have influenced the onset of LPP.

A 35-year-old woman who was previously healthy initially presented with recurrent pruritic papular eruptions on the flank, axillae, and groin of several months’ duration. The lesions appeared as 2-mm, flat-topped, violaceous papules. The patient had no known drug allergies, no medical or family history of skin disease, and was only taking 3000 mg/d of omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil). Histopathologic examination of a biopsy specimen from the inner thigh showed enlarged, atypical, dermal lymphocytes that were CD30+ (Figure 1). These findings were consistent with lymphomatoid papulosis. As she had undergone tubal ligation several years prior, she was prescribed oral bexarotene 300 mg once daily in addition to triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily, as needed. Symptoms were well controlled on this regimen.

Six months later the patient returned, presenting with a new central patch of scarring alopecia on the vertex of the scalp (Figure 2). Adjacent to the area of hair loss were areas of prominent perifollicular scale that were slightly violaceous in color. Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the scalp showed dermal scarring with perifollicular lamellar fibrosis surrounded by a rim of lymphoplasmacytic inflammation (Figure 3). Sebaceous glands were found to be reduced in number. These findings were consistent with cicatricial alopecia, which was further classified as LPP in conjunction with the clinical findings. No CD30+ lymphocytes were identified in these specimens.

Baseline fasting triglycerides were 123 mg/dL (desirable: <150 mg/dL; borderline: 150–199 mg/dL; high: ≥200 mg/dL) and were stable over the first 4 months on bexarotene. After 5 months of therapy, the triglycerides increased to a high of 255 mg/dL, which corresponded with the onset of LPP. She was treated for the hypertriglyceridemia with omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil), and subsequent triglyceride levels have normalized and been stable. Her alopecia has not progressed but is persistent. She continues to have central hypothyroidism due to bexarotene and is on levothyroxine. The lymphomatoid papulosis also remains stable with no signs of progression to cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

Although the exact mechanism of LPP is not fully understood, studies have suggested that cellular lipid metabolism may be responsible for the inflammation of the pilosebaceous unit.4-11 Hyperlipidemia is the most common side effect of oral bexarotene, typically occurring within the first 2 to 4 weeks of treatment.3,12 Considering the insights into the role of lipid regulation on LPP pathogenesis, it is reasonable to suspect that the dyslipidemia caused by bexarotene may have triggered the onset of LPP in our patient. The patient’s lipid values mostly remained within reference range throughout the course of treatment, though she did have elevation of triglycerides around the onset of LPP. Dyslipidemia has been reported in patients with lichen planus but not in patients with LPP. One case-control study showed no dyslipidemia in patients with LPP, but the triglyceride levels were not tracked over time and patients had varying durations since onset of disease at presentation.9-11,13 In our case, we were fortunate to have this information, and it may suggest an interaction between lipid dysregulation and the development of LPP. It would be interesting to explore this further in a larger patient population and to evaluate if control of dyslipidemia reduces progression of disease as it appears to have done for our patient.

To the Editor:

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a rare chronic skin disorder characterized by recurrent, self-healing crops of papulonodular eruptions, often resembling cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.1 Oral bexarotene, a retinoid X receptor–selective retinoid, can be used to control the disease.2,3 Lichen planopilaris (LPP) is a type of cicatricial alopecia characterized by irreversible hair loss, perifollicular inflammation, and follicular hyperkeratosis, commonly affecting the scalp vertex in adults.4 We report a case of a patient with lymphomatoid papulosis who was treated with bexarotene and subsequently developed LPP. We also discuss a proposed mechanism by which bexarotene may have influenced the onset of LPP.

A 35-year-old woman who was previously healthy initially presented with recurrent pruritic papular eruptions on the flank, axillae, and groin of several months’ duration. The lesions appeared as 2-mm, flat-topped, violaceous papules. The patient had no known drug allergies, no medical or family history of skin disease, and was only taking 3000 mg/d of omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil). Histopathologic examination of a biopsy specimen from the inner thigh showed enlarged, atypical, dermal lymphocytes that were CD30+ (Figure 1). These findings were consistent with lymphomatoid papulosis. As she had undergone tubal ligation several years prior, she was prescribed oral bexarotene 300 mg once daily in addition to triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily, as needed. Symptoms were well controlled on this regimen.

Six months later the patient returned, presenting with a new central patch of scarring alopecia on the vertex of the scalp (Figure 2). Adjacent to the area of hair loss were areas of prominent perifollicular scale that were slightly violaceous in color. Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the scalp showed dermal scarring with perifollicular lamellar fibrosis surrounded by a rim of lymphoplasmacytic inflammation (Figure 3). Sebaceous glands were found to be reduced in number. These findings were consistent with cicatricial alopecia, which was further classified as LPP in conjunction with the clinical findings. No CD30+ lymphocytes were identified in these specimens.

Baseline fasting triglycerides were 123 mg/dL (desirable: <150 mg/dL; borderline: 150–199 mg/dL; high: ≥200 mg/dL) and were stable over the first 4 months on bexarotene. After 5 months of therapy, the triglycerides increased to a high of 255 mg/dL, which corresponded with the onset of LPP. She was treated for the hypertriglyceridemia with omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil), and subsequent triglyceride levels have normalized and been stable. Her alopecia has not progressed but is persistent. She continues to have central hypothyroidism due to bexarotene and is on levothyroxine. The lymphomatoid papulosis also remains stable with no signs of progression to cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

Although the exact mechanism of LPP is not fully understood, studies have suggested that cellular lipid metabolism may be responsible for the inflammation of the pilosebaceous unit.4-11 Hyperlipidemia is the most common side effect of oral bexarotene, typically occurring within the first 2 to 4 weeks of treatment.3,12 Considering the insights into the role of lipid regulation on LPP pathogenesis, it is reasonable to suspect that the dyslipidemia caused by bexarotene may have triggered the onset of LPP in our patient. The patient’s lipid values mostly remained within reference range throughout the course of treatment, though she did have elevation of triglycerides around the onset of LPP. Dyslipidemia has been reported in patients with lichen planus but not in patients with LPP. One case-control study showed no dyslipidemia in patients with LPP, but the triglyceride levels were not tracked over time and patients had varying durations since onset of disease at presentation.9-11,13 In our case, we were fortunate to have this information, and it may suggest an interaction between lipid dysregulation and the development of LPP. It would be interesting to explore this further in a larger patient population and to evaluate if control of dyslipidemia reduces progression of disease as it appears to have done for our patient.

- Karp DL, Horn TD. Lymphomatoid papulosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:379-395; quiz 396-398.

- Krathen RA, Ward S, Duvic M. Bexarotene is a new treatment option for lymphomatoid papulosis. Dermatology. 2003;206:142-147.

- Targretin (bexarotene) capsule [package insert]. St. Petersburg, FL: Cardinal Health; 2003. http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=63656f64-e240-4855-8df9-ca1655863735. Accessed April 9, 2020.

- Assouly P, Reygagne P. Lichen planopilaris: update on diagnosis and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:3-10.

- Dogra S, Sarangal R. What’s new in cicatricial alopecia? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:576-90.

- Zheng Y, Eilertsen KJ, Ge L, et al. Scd1 is expressed in sebaceous glands and is disrupted in the asebia mouse. Nat Genet. 1999;23:268-270.

- Sundberg JP, Boggess D, Sundberg BA, et al. Asebia-2J (Scd1(ab2J)): a new allele and a model for scarring alopecia. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:2067-2075.

- Karnik P, Tekeste Z, McCormick TS, et al. Hair follicle stem cell-specific PPARgamma deletion causes scarring alopecia. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1243-157.

- López-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Rodríguez-Martínes MA. Alterations in serum lipid profile patterns in oral lichen planus: a cross-sectional study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:399-404.

- Arias-Santiago S, Buendía-Eisman A, Aneiros-Fernández J, et al. Lipid levels in patients with lichen planus: a case-control study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1398-1401.

- Dreiher J, Shapiro J, Cohen AD. Lichen planus and dyslipidaemia: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:626-629.

- de Vries-van der Weij J, de Haan W, Hu L, et al. Bexarotene induces dyslipidemia by increased very low-density lipoprotein production and cholesteryl ester transfer protein-mediated reduction of high-density lipoprotein. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2368-2375.

- Conic RRZ, Piliang M, Bergfeld W, et al. Association of lichen planopilaris with dyslipidemia. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1088-1089.

- Karp DL, Horn TD. Lymphomatoid papulosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:379-395; quiz 396-398.

- Krathen RA, Ward S, Duvic M. Bexarotene is a new treatment option for lymphomatoid papulosis. Dermatology. 2003;206:142-147.

- Targretin (bexarotene) capsule [package insert]. St. Petersburg, FL: Cardinal Health; 2003. http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=63656f64-e240-4855-8df9-ca1655863735. Accessed April 9, 2020.

- Assouly P, Reygagne P. Lichen planopilaris: update on diagnosis and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:3-10.

- Dogra S, Sarangal R. What’s new in cicatricial alopecia? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:576-90.

- Zheng Y, Eilertsen KJ, Ge L, et al. Scd1 is expressed in sebaceous glands and is disrupted in the asebia mouse. Nat Genet. 1999;23:268-270.

- Sundberg JP, Boggess D, Sundberg BA, et al. Asebia-2J (Scd1(ab2J)): a new allele and a model for scarring alopecia. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:2067-2075.

- Karnik P, Tekeste Z, McCormick TS, et al. Hair follicle stem cell-specific PPARgamma deletion causes scarring alopecia. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1243-157.

- López-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Rodríguez-Martínes MA. Alterations in serum lipid profile patterns in oral lichen planus: a cross-sectional study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:399-404.

- Arias-Santiago S, Buendía-Eisman A, Aneiros-Fernández J, et al. Lipid levels in patients with lichen planus: a case-control study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1398-1401.

- Dreiher J, Shapiro J, Cohen AD. Lichen planus and dyslipidaemia: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:626-629.

- de Vries-van der Weij J, de Haan W, Hu L, et al. Bexarotene induces dyslipidemia by increased very low-density lipoprotein production and cholesteryl ester transfer protein-mediated reduction of high-density lipoprotein. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2368-2375.

- Conic RRZ, Piliang M, Bergfeld W, et al. Association of lichen planopilaris with dyslipidemia. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1088-1089.

Practice Points

- Oral retinoids may be associated with development of lichen planopilaris (LPP).

- Hypertriglyceridemia may be associated with onset of LPP.

Clustered Vesicles in a Blaschkoid Pattern

The Diagnosis: Linear Vesiculobullous Keratosis Follicularis (Darier Disease)

Darier disease (DD), or keratosis follicularis, is typically an autosomal-dominant disorder that is characterized by greasy hyperkeratotic papules that coalesce into warty plaques with a predilection for seborrheic areas. The lesions usually are pruritic; malodorous; and may be exacerbated by sunlight, heat, or sweating. Darier disease may be accompanied by oral mucosal involvement including fine white papules on the palate.1 The condition also can be accompanied by hand and nail involvement (95% of cases) including palmar pitting, punctate keratoses, hemorrhagic macules, palmoplantar keratoderma, and acrokeratosis verruciformis–like lesions on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet. Nail changes predominately occur on the fingers, manifesting as longitudinal splitting, subungual hyperkeratosis, or characteristic white and red longitudinal bands with V-shaped nicks at the free margin of the nail. In linear DD, hand and nail involvement is rare and, when present, ipsilateral to the primary lesions.1,2

The clinical variants of DD are classified by lesion morphology or distribution, or both. Morphological variants include vesiculobullous, cornified, erosive, acral hemorrhagic, and guttate leukodermic macular.1,2 The clinical features of chronic relapsing vesicular lesions and histologic findings described in this case are consistent with vesiculobullous DD, though genetic testing was not performed.3,4 As in our case, some patients lack a family history and the disease is thought to be the result of genetic mosaicism or somatic postzygotic mutations that affect a limited number of cells. These mosaic variants are named by their cutaneous distribution (ie, linear, segmental, unilateral, localized) and tend to course along the Blaschko lines, most commonly on the trunk. Studies have shown various types of mutations specific to the ATP2A2 gene in the affected tissue but not in the unaffected skin.5 This gene encodes for sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum ATPase SERCA2, which is responsible for intracellular calcium signaling. These mosaic forms of DD are unlikely to be inherited by offspring, in contrast to patients with mosaic epidermal nevi with epidermolytic hyperkeratosis who have a high likelihood of having children with generalized epidermolytic hyperkeratosis.6

Darier disease is a chronic incurable disease. Topical corticosteroid, retinoid, 5-fluorouracil, keratolytics, and laser ablation or excision are used in mild and limited disease with mixed outcomes.7 Oral retinoids are effective in severe or systemic cases of DD by inhibiting hyperkeratosis.8 Individuals with DD are predisposed to infection, warranting regular surveillance and use of antimicrobials and bleach baths. In addition to prophylaxis for bacterial superinfection, patients also are predisposed to getting disseminated herpes simplex virus in the form of eczema herpeticum.

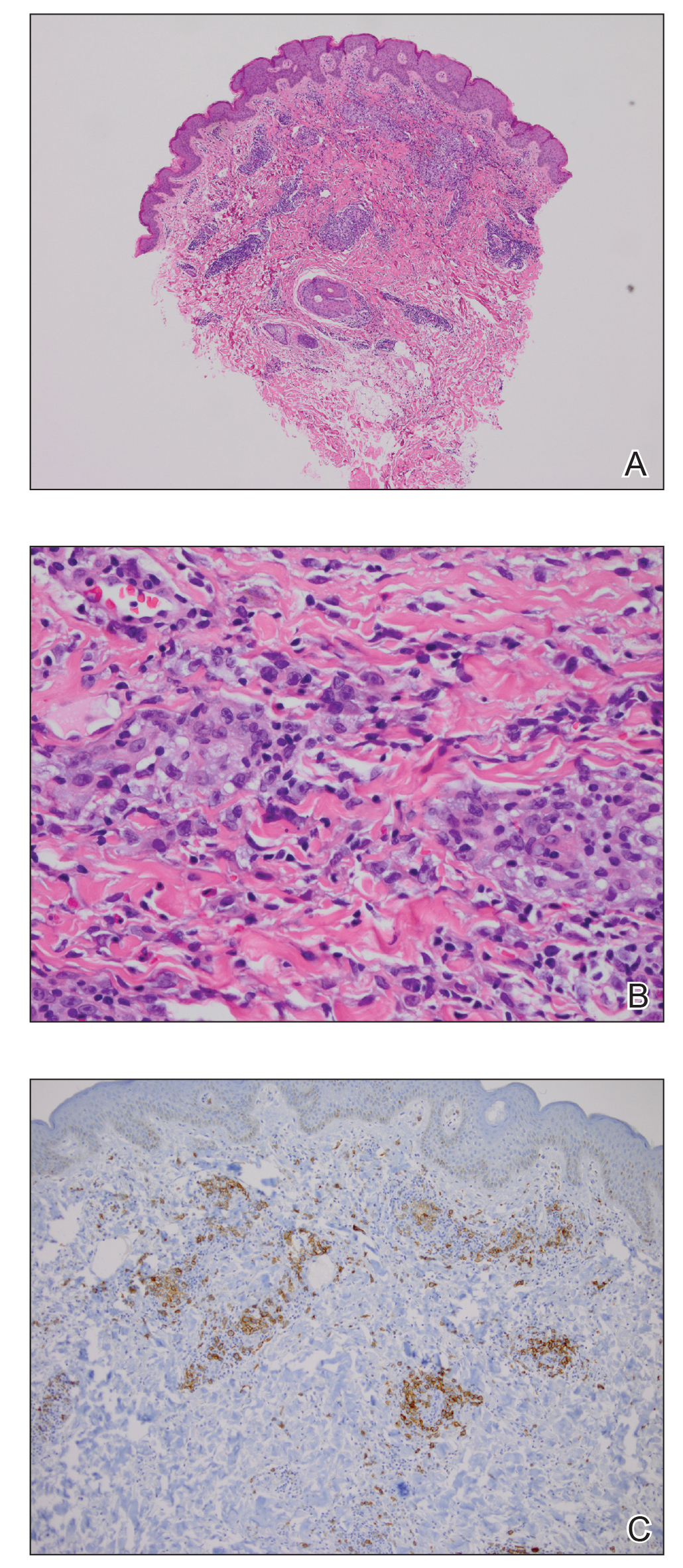

In our patient, the diagnosis was confirmed by performing a punch biopsy from one of the vesicular lesions. Histopathologic examination revealed suprabasal acantholytic dyskeratosis with superficial perivascular and interstitial inflammation with eosinophils (Figure). Immunohistochemical staining showed no evidence of varicella-zoster virus or herpes simplex virus type 1 or type 2.

Histopathology revealed suprabasal acantholysis forming an intraepidermal cleft with superficial perivascular inflammation (A)(H&E, original magnification ×100) and acantholysis with dyskeratotic keratinocytes floating within the intraepidermal cleft (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). |

Our patient was prescribed tretinoin cream 0.1% daily and was advised to use sun protection and stop valacyclovir. At follow-up she noted decreased frequency of outbreaks after starting the tretinoin cream and the patient has now been free of any outbreaks for 8 months.

1. Burge SM, Wilkinson JD. Darier-White disease: a review of the clinical features in 163 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:40-50.

2. Cooper SM, Burge SM. Darier’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:97-105.

3. Kakar B, Kabir S, Garg VK, et al. A case of bullous Darier’s disease histologically mimicking Hailey-Hailey disease. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:28.

4. Telfer NR, Burge SM, Ryan TJ. Vesiculo-bullous Darier’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 1990;122:831-834.

5. Sakuntabhai A, Dhitavat J, Burge SM, et al. Mosaicism for ATP2A2 mutations causes segmental Darier’s disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:1144-1147.

6. O’Malley MP, Haake A, Goldsmith L, et al. Localized Darier disease. implications for genetic studies. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1134-1138.

7. Le Bidre E, Delage M, Celerier P, et al. Efficacy and risks of topical 5-fluorouracil in Darier’s disease. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010;137:455-459.

8. Abe M, Yasuda M, Yokoyama Y, et al. Successful treatment of combination therapy with tacalcitol lotion associated with sunscreen for localized Darier’s disease. J Dermatol. 2010;37:718-721.

The Diagnosis: Linear Vesiculobullous Keratosis Follicularis (Darier Disease)

Darier disease (DD), or keratosis follicularis, is typically an autosomal-dominant disorder that is characterized by greasy hyperkeratotic papules that coalesce into warty plaques with a predilection for seborrheic areas. The lesions usually are pruritic; malodorous; and may be exacerbated by sunlight, heat, or sweating. Darier disease may be accompanied by oral mucosal involvement including fine white papules on the palate.1 The condition also can be accompanied by hand and nail involvement (95% of cases) including palmar pitting, punctate keratoses, hemorrhagic macules, palmoplantar keratoderma, and acrokeratosis verruciformis–like lesions on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet. Nail changes predominately occur on the fingers, manifesting as longitudinal splitting, subungual hyperkeratosis, or characteristic white and red longitudinal bands with V-shaped nicks at the free margin of the nail. In linear DD, hand and nail involvement is rare and, when present, ipsilateral to the primary lesions.1,2

The clinical variants of DD are classified by lesion morphology or distribution, or both. Morphological variants include vesiculobullous, cornified, erosive, acral hemorrhagic, and guttate leukodermic macular.1,2 The clinical features of chronic relapsing vesicular lesions and histologic findings described in this case are consistent with vesiculobullous DD, though genetic testing was not performed.3,4 As in our case, some patients lack a family history and the disease is thought to be the result of genetic mosaicism or somatic postzygotic mutations that affect a limited number of cells. These mosaic variants are named by their cutaneous distribution (ie, linear, segmental, unilateral, localized) and tend to course along the Blaschko lines, most commonly on the trunk. Studies have shown various types of mutations specific to the ATP2A2 gene in the affected tissue but not in the unaffected skin.5 This gene encodes for sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum ATPase SERCA2, which is responsible for intracellular calcium signaling. These mosaic forms of DD are unlikely to be inherited by offspring, in contrast to patients with mosaic epidermal nevi with epidermolytic hyperkeratosis who have a high likelihood of having children with generalized epidermolytic hyperkeratosis.6

Darier disease is a chronic incurable disease. Topical corticosteroid, retinoid, 5-fluorouracil, keratolytics, and laser ablation or excision are used in mild and limited disease with mixed outcomes.7 Oral retinoids are effective in severe or systemic cases of DD by inhibiting hyperkeratosis.8 Individuals with DD are predisposed to infection, warranting regular surveillance and use of antimicrobials and bleach baths. In addition to prophylaxis for bacterial superinfection, patients also are predisposed to getting disseminated herpes simplex virus in the form of eczema herpeticum.

In our patient, the diagnosis was confirmed by performing a punch biopsy from one of the vesicular lesions. Histopathologic examination revealed suprabasal acantholytic dyskeratosis with superficial perivascular and interstitial inflammation with eosinophils (Figure). Immunohistochemical staining showed no evidence of varicella-zoster virus or herpes simplex virus type 1 or type 2.

Histopathology revealed suprabasal acantholysis forming an intraepidermal cleft with superficial perivascular inflammation (A)(H&E, original magnification ×100) and acantholysis with dyskeratotic keratinocytes floating within the intraepidermal cleft (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). |

Our patient was prescribed tretinoin cream 0.1% daily and was advised to use sun protection and stop valacyclovir. At follow-up she noted decreased frequency of outbreaks after starting the tretinoin cream and the patient has now been free of any outbreaks for 8 months.

The Diagnosis: Linear Vesiculobullous Keratosis Follicularis (Darier Disease)

Darier disease (DD), or keratosis follicularis, is typically an autosomal-dominant disorder that is characterized by greasy hyperkeratotic papules that coalesce into warty plaques with a predilection for seborrheic areas. The lesions usually are pruritic; malodorous; and may be exacerbated by sunlight, heat, or sweating. Darier disease may be accompanied by oral mucosal involvement including fine white papules on the palate.1 The condition also can be accompanied by hand and nail involvement (95% of cases) including palmar pitting, punctate keratoses, hemorrhagic macules, palmoplantar keratoderma, and acrokeratosis verruciformis–like lesions on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet. Nail changes predominately occur on the fingers, manifesting as longitudinal splitting, subungual hyperkeratosis, or characteristic white and red longitudinal bands with V-shaped nicks at the free margin of the nail. In linear DD, hand and nail involvement is rare and, when present, ipsilateral to the primary lesions.1,2

The clinical variants of DD are classified by lesion morphology or distribution, or both. Morphological variants include vesiculobullous, cornified, erosive, acral hemorrhagic, and guttate leukodermic macular.1,2 The clinical features of chronic relapsing vesicular lesions and histologic findings described in this case are consistent with vesiculobullous DD, though genetic testing was not performed.3,4 As in our case, some patients lack a family history and the disease is thought to be the result of genetic mosaicism or somatic postzygotic mutations that affect a limited number of cells. These mosaic variants are named by their cutaneous distribution (ie, linear, segmental, unilateral, localized) and tend to course along the Blaschko lines, most commonly on the trunk. Studies have shown various types of mutations specific to the ATP2A2 gene in the affected tissue but not in the unaffected skin.5 This gene encodes for sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum ATPase SERCA2, which is responsible for intracellular calcium signaling. These mosaic forms of DD are unlikely to be inherited by offspring, in contrast to patients with mosaic epidermal nevi with epidermolytic hyperkeratosis who have a high likelihood of having children with generalized epidermolytic hyperkeratosis.6

Darier disease is a chronic incurable disease. Topical corticosteroid, retinoid, 5-fluorouracil, keratolytics, and laser ablation or excision are used in mild and limited disease with mixed outcomes.7 Oral retinoids are effective in severe or systemic cases of DD by inhibiting hyperkeratosis.8 Individuals with DD are predisposed to infection, warranting regular surveillance and use of antimicrobials and bleach baths. In addition to prophylaxis for bacterial superinfection, patients also are predisposed to getting disseminated herpes simplex virus in the form of eczema herpeticum.

In our patient, the diagnosis was confirmed by performing a punch biopsy from one of the vesicular lesions. Histopathologic examination revealed suprabasal acantholytic dyskeratosis with superficial perivascular and interstitial inflammation with eosinophils (Figure). Immunohistochemical staining showed no evidence of varicella-zoster virus or herpes simplex virus type 1 or type 2.

Histopathology revealed suprabasal acantholysis forming an intraepidermal cleft with superficial perivascular inflammation (A)(H&E, original magnification ×100) and acantholysis with dyskeratotic keratinocytes floating within the intraepidermal cleft (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). |

Our patient was prescribed tretinoin cream 0.1% daily and was advised to use sun protection and stop valacyclovir. At follow-up she noted decreased frequency of outbreaks after starting the tretinoin cream and the patient has now been free of any outbreaks for 8 months.

1. Burge SM, Wilkinson JD. Darier-White disease: a review of the clinical features in 163 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:40-50.

2. Cooper SM, Burge SM. Darier’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:97-105.

3. Kakar B, Kabir S, Garg VK, et al. A case of bullous Darier’s disease histologically mimicking Hailey-Hailey disease. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:28.

4. Telfer NR, Burge SM, Ryan TJ. Vesiculo-bullous Darier’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 1990;122:831-834.

5. Sakuntabhai A, Dhitavat J, Burge SM, et al. Mosaicism for ATP2A2 mutations causes segmental Darier’s disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:1144-1147.

6. O’Malley MP, Haake A, Goldsmith L, et al. Localized Darier disease. implications for genetic studies. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1134-1138.

7. Le Bidre E, Delage M, Celerier P, et al. Efficacy and risks of topical 5-fluorouracil in Darier’s disease. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010;137:455-459.

8. Abe M, Yasuda M, Yokoyama Y, et al. Successful treatment of combination therapy with tacalcitol lotion associated with sunscreen for localized Darier’s disease. J Dermatol. 2010;37:718-721.

1. Burge SM, Wilkinson JD. Darier-White disease: a review of the clinical features in 163 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:40-50.

2. Cooper SM, Burge SM. Darier’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:97-105.

3. Kakar B, Kabir S, Garg VK, et al. A case of bullous Darier’s disease histologically mimicking Hailey-Hailey disease. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:28.

4. Telfer NR, Burge SM, Ryan TJ. Vesiculo-bullous Darier’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 1990;122:831-834.

5. Sakuntabhai A, Dhitavat J, Burge SM, et al. Mosaicism for ATP2A2 mutations causes segmental Darier’s disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:1144-1147.

6. O’Malley MP, Haake A, Goldsmith L, et al. Localized Darier disease. implications for genetic studies. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1134-1138.

7. Le Bidre E, Delage M, Celerier P, et al. Efficacy and risks of topical 5-fluorouracil in Darier’s disease. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010;137:455-459.

8. Abe M, Yasuda M, Yokoyama Y, et al. Successful treatment of combination therapy with tacalcitol lotion associated with sunscreen for localized Darier’s disease. J Dermatol. 2010;37:718-721.

A 42-year-old woman presented with an intermittent nontender and minimally pruritic rash localized to the left side of the trunk of 20 years’ duration. Four to 6 times per year blisters would develop and then resolve after 1 to 2 weeks with mildly pruritic brown patches. These patches would resolve within approximately 4 weeks. Most notably, the condition was exacerbated by sunlight and heat, though stress sometimes led to an outbreak of vesicles. The patient reported that the eruption, which she was told was recurrent shingles, would improve with oral valacyclovir 1 g twice daily and did not improve with topical steroid usage. She never had antecedent or concurrent fevers, shortness of breath, arthralgia, or cold sores. There was no family history of any blistering skin conditions such as epidermolysis bullosa, pemphigus, Darier disease, or bullous pemphigoid. Her partner also did not have a history of similar rashes, and the patient denied any history of travel outside of England and the southwestern United States. Initial physical examination revealed clustered vesicles surrounded by brown-pink patches in a blaschkoid pattern spanning from the anterior to posterior aspects of the left flank. Notably, the patient had no oral lesions and no changes of the hair or nails.

Papules on the Face and Body

The Diagnosis: Lichen Spinulosus

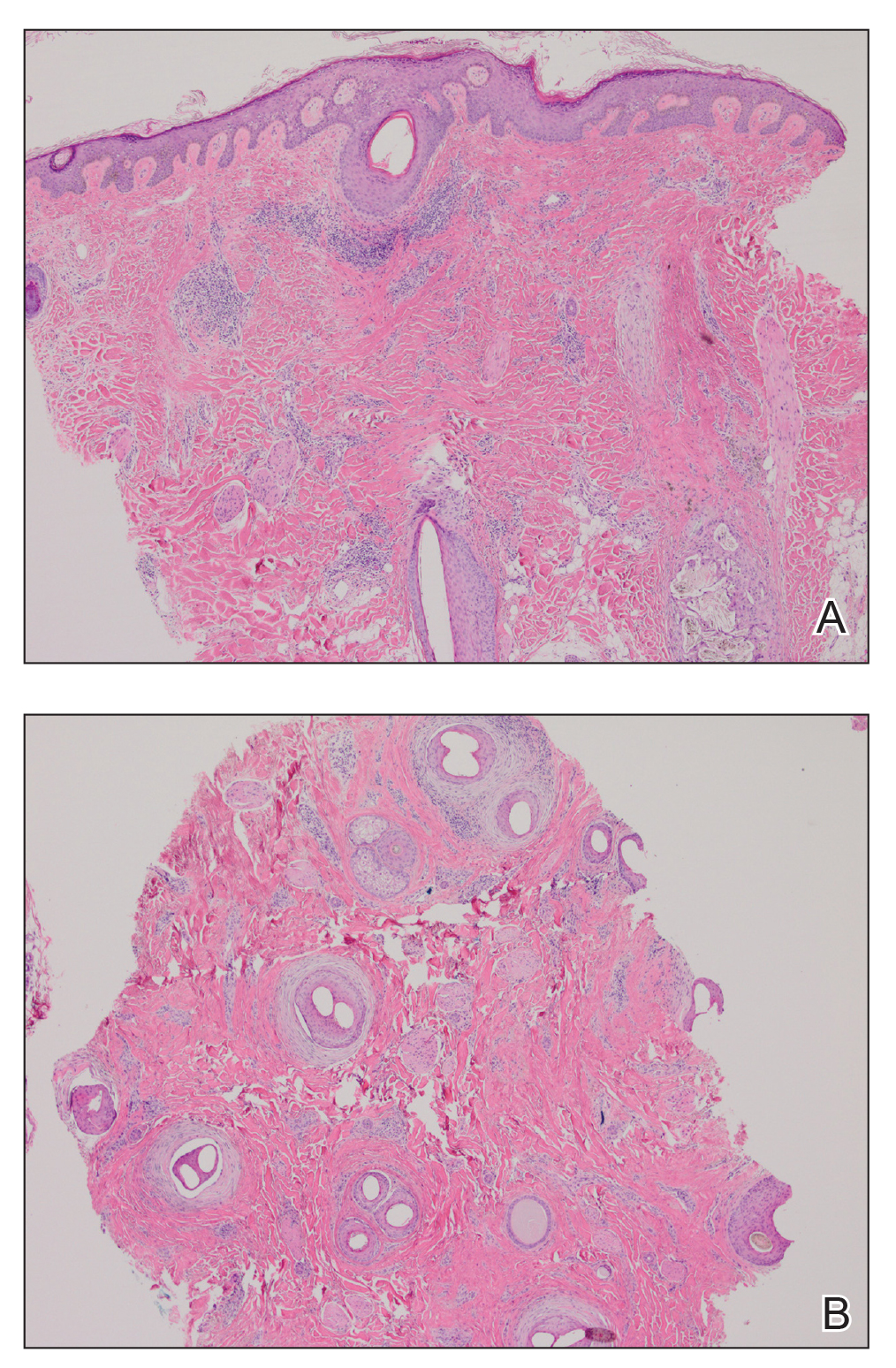

Lichen spinulosus, also referred to as keratosis spinulosa, is a disorder of keratinization characterized by grouped 1- to 3-mm papules with a horny spine localized to follicles (Figure).1 These lesions most commonly occur in the first through third decades of life, presenting as 2- to 6-cm patches on the neck, buttocks, thighs, abdomen, or extensor surfaces.1-4 Some patients report mild pruritus.1 The cause is unknown.1-3,5-7 Several proposed but unproven explanations include atopy,2,4 genetic predisposition,1,2 toxins,3,5 infection,5 abnormal immune response,8 and vitamin deficiency.1,6,7

Our patient’s presentation is atypical due to her age and the involvement of her face. Generalized lichen spinulosus in adults likely is rare. A few similar cases have been reported: a 61-year-old woman with Crohn disease and lichen spinulosus affecting the groin, inframammary region, and back8; 2 case reports linked to alcoholism-associated nutritional deficiency6,7; and generalized lichen spinulosus–like eruptions in 2 patients with human immuno-deficiency virus infection.9,10 Our patient’s medical history indicated an extensive smoking history; thiamine deficiency 5 years prior treated with vitamin B complex supplements, which she still takes; and a recent diagnosis of vitamin D deficiency. She had no evidence of immunodeficiency or systemic illness on routine screening.

The disorders of follicular keratinization are lichen spinulosus, keratosis pilaris, keratosis pilaris atrophicans, pityriasis rubra pilaris, lichen planopilaris, erythromelanosis follicularis faciei, and phrynoderma.11 The clinical differential diagnosis of lichen spinulosus includes keratosis pilaris, phrynoderma, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and frictional lichenoid eruption. Lichen spinulosus can be distinguished from keratosis pilaris by 4 factors1,11: (1) keratosis pilaris lesions develop slowly over time as opposed to the rapid onset in lichen spinulosus; (2) keratosis pilaris is preferentially located on the upper arms and legs; (3) keratosis pilaris does not develop in small clusters; (4) keratosis pilaris, unlike lichen spinulosus, often has a thin outline of perifollicular erythema. Histopathologically, lichen spinulosus is similar to keratosis pilaris, showing dilated hair follicles with a keratin plug and perifollicular and perivascular dermal lymphocytic infiltrate.1 A punch biopsy from our patient’s cheek demonstrated focal follicular hyperkeratosis with dermal perivascular inflammation. Periodic acid–Schiff with diastase stain was negative for pathogenic fungal organisms.

Treatment of lichen spinulosus is initiated to address cosmetic concerns. Traditionally, keratolytics and emollients are utilized. Success has been described with salicylic acid gel 6% without occlusion for 8 weeks12 or with occlusion for 2 weeks.13 Tar preparations and mid-potency topical corticosteroids may be used on lesions not located on the face.2,4,15 Topical vitamin A,2 lactic acid,4 and ammonium lactate lotion2 have been therapeutic in some cases. Facial lesions have been successfully treated with tacalcitol14 or tretinoin gel 0.04% in combination with hydroactive adhesive applications.15 In the case of lichen spinulosus accompanying alcoholism, oral vitamin supplementation has been sufficient for resolution.6,7

Our patient was initially prescribed ammonium lactate lotion twice daily and tretinoin cream 0.025% for facial application nightly. She only used the tretinoin briefly due to skin irritation, and she discontinued use of ammonium lactate due to lotion texture. Three months of vitamin A and vitamin B complex supplementation did not lead to any improvement. She believed the papules softened by scrubbing them with a loofah in the shower and then moisturizing. Malignancy workup, including a colonoscopy, mammography, chest radiograph, and basic blood tests, were negative. No remarkable change was noted by the patient at 1-year follow-up.

1. Friedman SJ. Lichen spinulosus. clinicopathologic review of thirty-five cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:261-264.

2. Boyd AS. Lichen spinulosus: case report and overview. Cutis. 1989;43:557-560.

3. Adamson H. Lichen pilaris, seu spinulosis. Br J Dermatol. 1905;17:39-54.

4. Strickling WA, Norton SA. Spiny eruption on the neck. diagnosis: lichen spinulosus (LS). Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1165-1170.

5. Becker S. Lichen spinulosus following intradermal application of diphtheria toxin. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1930;21:839-840.

6. Irgang S. Lichen spinulosus responsive to ascorbic acid (vitamin C). case in an alcoholic adult. Skin. 1964;3:145-146.

7. Kabashima R, Sugita K, Kabashima K, et al. Lichen spinulosus in an alcoholic patient. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:311-312.

8. Kano Y, Orihara M, Yagita A, et al. Lichen spinulosus in a patient with Crohn disease. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:670-671.

9. Cohen SJ, Dicken CH. Generalized lichen spinulosus in an HIV-positive man. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:116-118.

10. Resnick SD, Murrell DF, Woosley J. Acne conglobata and a generalized lichen spinulosus-like eruption in a man seropositive for human immunodeficiency virus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:1013-1014.

11. McMichael A, Curtis A, Guzman-Sanchez D, et al. Folliculitis and other follicular disorders. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2012:571-586.

12. Tuyp E, McLeod WA, Boyko W. Lichen spinulosus with immunofluorescent studies. Cutis. 1984;33:197-200.

13. Maiocco KJ, Miller OF. Lichen spinulosus: response to therapy. Cutis. 1976;17:294-299.

14. Kim SH, Kang JH, Seo JK, et al. Successful treatment of lichen spinulosus with topical tacalcitol cream. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:546-547.

15. Forman SB, Hudgins EM, Blaylock WK. Lichen spinulosus: excellent response to tretinoin gel and hydroactive adhesive applications. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:122-123.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Spinulosus

Lichen spinulosus, also referred to as keratosis spinulosa, is a disorder of keratinization characterized by grouped 1- to 3-mm papules with a horny spine localized to follicles (Figure).1 These lesions most commonly occur in the first through third decades of life, presenting as 2- to 6-cm patches on the neck, buttocks, thighs, abdomen, or extensor surfaces.1-4 Some patients report mild pruritus.1 The cause is unknown.1-3,5-7 Several proposed but unproven explanations include atopy,2,4 genetic predisposition,1,2 toxins,3,5 infection,5 abnormal immune response,8 and vitamin deficiency.1,6,7

Our patient’s presentation is atypical due to her age and the involvement of her face. Generalized lichen spinulosus in adults likely is rare. A few similar cases have been reported: a 61-year-old woman with Crohn disease and lichen spinulosus affecting the groin, inframammary region, and back8; 2 case reports linked to alcoholism-associated nutritional deficiency6,7; and generalized lichen spinulosus–like eruptions in 2 patients with human immuno-deficiency virus infection.9,10 Our patient’s medical history indicated an extensive smoking history; thiamine deficiency 5 years prior treated with vitamin B complex supplements, which she still takes; and a recent diagnosis of vitamin D deficiency. She had no evidence of immunodeficiency or systemic illness on routine screening.

The disorders of follicular keratinization are lichen spinulosus, keratosis pilaris, keratosis pilaris atrophicans, pityriasis rubra pilaris, lichen planopilaris, erythromelanosis follicularis faciei, and phrynoderma.11 The clinical differential diagnosis of lichen spinulosus includes keratosis pilaris, phrynoderma, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and frictional lichenoid eruption. Lichen spinulosus can be distinguished from keratosis pilaris by 4 factors1,11: (1) keratosis pilaris lesions develop slowly over time as opposed to the rapid onset in lichen spinulosus; (2) keratosis pilaris is preferentially located on the upper arms and legs; (3) keratosis pilaris does not develop in small clusters; (4) keratosis pilaris, unlike lichen spinulosus, often has a thin outline of perifollicular erythema. Histopathologically, lichen spinulosus is similar to keratosis pilaris, showing dilated hair follicles with a keratin plug and perifollicular and perivascular dermal lymphocytic infiltrate.1 A punch biopsy from our patient’s cheek demonstrated focal follicular hyperkeratosis with dermal perivascular inflammation. Periodic acid–Schiff with diastase stain was negative for pathogenic fungal organisms.

Treatment of lichen spinulosus is initiated to address cosmetic concerns. Traditionally, keratolytics and emollients are utilized. Success has been described with salicylic acid gel 6% without occlusion for 8 weeks12 or with occlusion for 2 weeks.13 Tar preparations and mid-potency topical corticosteroids may be used on lesions not located on the face.2,4,15 Topical vitamin A,2 lactic acid,4 and ammonium lactate lotion2 have been therapeutic in some cases. Facial lesions have been successfully treated with tacalcitol14 or tretinoin gel 0.04% in combination with hydroactive adhesive applications.15 In the case of lichen spinulosus accompanying alcoholism, oral vitamin supplementation has been sufficient for resolution.6,7

Our patient was initially prescribed ammonium lactate lotion twice daily and tretinoin cream 0.025% for facial application nightly. She only used the tretinoin briefly due to skin irritation, and she discontinued use of ammonium lactate due to lotion texture. Three months of vitamin A and vitamin B complex supplementation did not lead to any improvement. She believed the papules softened by scrubbing them with a loofah in the shower and then moisturizing. Malignancy workup, including a colonoscopy, mammography, chest radiograph, and basic blood tests, were negative. No remarkable change was noted by the patient at 1-year follow-up.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Spinulosus

Lichen spinulosus, also referred to as keratosis spinulosa, is a disorder of keratinization characterized by grouped 1- to 3-mm papules with a horny spine localized to follicles (Figure).1 These lesions most commonly occur in the first through third decades of life, presenting as 2- to 6-cm patches on the neck, buttocks, thighs, abdomen, or extensor surfaces.1-4 Some patients report mild pruritus.1 The cause is unknown.1-3,5-7 Several proposed but unproven explanations include atopy,2,4 genetic predisposition,1,2 toxins,3,5 infection,5 abnormal immune response,8 and vitamin deficiency.1,6,7

Our patient’s presentation is atypical due to her age and the involvement of her face. Generalized lichen spinulosus in adults likely is rare. A few similar cases have been reported: a 61-year-old woman with Crohn disease and lichen spinulosus affecting the groin, inframammary region, and back8; 2 case reports linked to alcoholism-associated nutritional deficiency6,7; and generalized lichen spinulosus–like eruptions in 2 patients with human immuno-deficiency virus infection.9,10 Our patient’s medical history indicated an extensive smoking history; thiamine deficiency 5 years prior treated with vitamin B complex supplements, which she still takes; and a recent diagnosis of vitamin D deficiency. She had no evidence of immunodeficiency or systemic illness on routine screening.

The disorders of follicular keratinization are lichen spinulosus, keratosis pilaris, keratosis pilaris atrophicans, pityriasis rubra pilaris, lichen planopilaris, erythromelanosis follicularis faciei, and phrynoderma.11 The clinical differential diagnosis of lichen spinulosus includes keratosis pilaris, phrynoderma, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and frictional lichenoid eruption. Lichen spinulosus can be distinguished from keratosis pilaris by 4 factors1,11: (1) keratosis pilaris lesions develop slowly over time as opposed to the rapid onset in lichen spinulosus; (2) keratosis pilaris is preferentially located on the upper arms and legs; (3) keratosis pilaris does not develop in small clusters; (4) keratosis pilaris, unlike lichen spinulosus, often has a thin outline of perifollicular erythema. Histopathologically, lichen spinulosus is similar to keratosis pilaris, showing dilated hair follicles with a keratin plug and perifollicular and perivascular dermal lymphocytic infiltrate.1 A punch biopsy from our patient’s cheek demonstrated focal follicular hyperkeratosis with dermal perivascular inflammation. Periodic acid–Schiff with diastase stain was negative for pathogenic fungal organisms.

Treatment of lichen spinulosus is initiated to address cosmetic concerns. Traditionally, keratolytics and emollients are utilized. Success has been described with salicylic acid gel 6% without occlusion for 8 weeks12 or with occlusion for 2 weeks.13 Tar preparations and mid-potency topical corticosteroids may be used on lesions not located on the face.2,4,15 Topical vitamin A,2 lactic acid,4 and ammonium lactate lotion2 have been therapeutic in some cases. Facial lesions have been successfully treated with tacalcitol14 or tretinoin gel 0.04% in combination with hydroactive adhesive applications.15 In the case of lichen spinulosus accompanying alcoholism, oral vitamin supplementation has been sufficient for resolution.6,7

Our patient was initially prescribed ammonium lactate lotion twice daily and tretinoin cream 0.025% for facial application nightly. She only used the tretinoin briefly due to skin irritation, and she discontinued use of ammonium lactate due to lotion texture. Three months of vitamin A and vitamin B complex supplementation did not lead to any improvement. She believed the papules softened by scrubbing them with a loofah in the shower and then moisturizing. Malignancy workup, including a colonoscopy, mammography, chest radiograph, and basic blood tests, were negative. No remarkable change was noted by the patient at 1-year follow-up.

1. Friedman SJ. Lichen spinulosus. clinicopathologic review of thirty-five cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:261-264.

2. Boyd AS. Lichen spinulosus: case report and overview. Cutis. 1989;43:557-560.

3. Adamson H. Lichen pilaris, seu spinulosis. Br J Dermatol. 1905;17:39-54.

4. Strickling WA, Norton SA. Spiny eruption on the neck. diagnosis: lichen spinulosus (LS). Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1165-1170.

5. Becker S. Lichen spinulosus following intradermal application of diphtheria toxin. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1930;21:839-840.

6. Irgang S. Lichen spinulosus responsive to ascorbic acid (vitamin C). case in an alcoholic adult. Skin. 1964;3:145-146.

7. Kabashima R, Sugita K, Kabashima K, et al. Lichen spinulosus in an alcoholic patient. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:311-312.

8. Kano Y, Orihara M, Yagita A, et al. Lichen spinulosus in a patient with Crohn disease. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:670-671.

9. Cohen SJ, Dicken CH. Generalized lichen spinulosus in an HIV-positive man. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:116-118.

10. Resnick SD, Murrell DF, Woosley J. Acne conglobata and a generalized lichen spinulosus-like eruption in a man seropositive for human immunodeficiency virus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:1013-1014.

11. McMichael A, Curtis A, Guzman-Sanchez D, et al. Folliculitis and other follicular disorders. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2012:571-586.

12. Tuyp E, McLeod WA, Boyko W. Lichen spinulosus with immunofluorescent studies. Cutis. 1984;33:197-200.

13. Maiocco KJ, Miller OF. Lichen spinulosus: response to therapy. Cutis. 1976;17:294-299.

14. Kim SH, Kang JH, Seo JK, et al. Successful treatment of lichen spinulosus with topical tacalcitol cream. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:546-547.

15. Forman SB, Hudgins EM, Blaylock WK. Lichen spinulosus: excellent response to tretinoin gel and hydroactive adhesive applications. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:122-123.

1. Friedman SJ. Lichen spinulosus. clinicopathologic review of thirty-five cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:261-264.

2. Boyd AS. Lichen spinulosus: case report and overview. Cutis. 1989;43:557-560.

3. Adamson H. Lichen pilaris, seu spinulosis. Br J Dermatol. 1905;17:39-54.

4. Strickling WA, Norton SA. Spiny eruption on the neck. diagnosis: lichen spinulosus (LS). Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1165-1170.

5. Becker S. Lichen spinulosus following intradermal application of diphtheria toxin. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1930;21:839-840.

6. Irgang S. Lichen spinulosus responsive to ascorbic acid (vitamin C). case in an alcoholic adult. Skin. 1964;3:145-146.

7. Kabashima R, Sugita K, Kabashima K, et al. Lichen spinulosus in an alcoholic patient. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:311-312.

8. Kano Y, Orihara M, Yagita A, et al. Lichen spinulosus in a patient with Crohn disease. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:670-671.

9. Cohen SJ, Dicken CH. Generalized lichen spinulosus in an HIV-positive man. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:116-118.

10. Resnick SD, Murrell DF, Woosley J. Acne conglobata and a generalized lichen spinulosus-like eruption in a man seropositive for human immunodeficiency virus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:1013-1014.

11. McMichael A, Curtis A, Guzman-Sanchez D, et al. Folliculitis and other follicular disorders. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2012:571-586.

12. Tuyp E, McLeod WA, Boyko W. Lichen spinulosus with immunofluorescent studies. Cutis. 1984;33:197-200.

13. Maiocco KJ, Miller OF. Lichen spinulosus: response to therapy. Cutis. 1976;17:294-299.

14. Kim SH, Kang JH, Seo JK, et al. Successful treatment of lichen spinulosus with topical tacalcitol cream. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:546-547.

15. Forman SB, Hudgins EM, Blaylock WK. Lichen spinulosus: excellent response to tretinoin gel and hydroactive adhesive applications. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:122-123.

A 65-year-old woman presented for evaluation of papules on the face and body that had developed over a short period of time approximately 1.5 years prior. The papules were entirely asymptomatic. She had no prior treatment. On physical examination multiple flesh-colored papules with a central keratotic spicule were noted on the face, neck, arms, and legs.