User login

Tackling midurethral sling complications

Over the past 2 decades, midurethral slings, both via a retropubic and a transobturator approach have become the first-line therapy for the surgical correction of female stress urinary incontinence. Not only are cure rates excellent for both techniques, but the incidence of complications are low.

Intraoperatively, major concerns include vascular lesions, nerve injuries, and injuries to the bowel. More minor concerns are related to the bladder.

Perioperative complications include retropubic hematoma, blood loss, urinary tract infection, and spondylitis. Postoperative risks include transient versus permanent urinary retention, vaginal versus urethral erosion, de novo urgency, bladder erosion, and urethral obstruction.

In this edition of Master Class in gynecologic surgery, I am pleased to solicit the help of Dr. Charles Rardin, who will make recommendations regarding the management of some of the most common complications related to midurethral sling procedures.

Dr. Rardin is the director of the Robotic Surgery Program at Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island, in Providence; a surgeon in Women & Infants’ division of urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery; and is the director of the hospital’s fellowship urogynecology and reconstructive pelvic surgery.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller is a consultant and on the speaker’s bureau for Ethicon.

Over the past 2 decades, midurethral slings, both via a retropubic and a transobturator approach have become the first-line therapy for the surgical correction of female stress urinary incontinence. Not only are cure rates excellent for both techniques, but the incidence of complications are low.

Intraoperatively, major concerns include vascular lesions, nerve injuries, and injuries to the bowel. More minor concerns are related to the bladder.

Perioperative complications include retropubic hematoma, blood loss, urinary tract infection, and spondylitis. Postoperative risks include transient versus permanent urinary retention, vaginal versus urethral erosion, de novo urgency, bladder erosion, and urethral obstruction.

In this edition of Master Class in gynecologic surgery, I am pleased to solicit the help of Dr. Charles Rardin, who will make recommendations regarding the management of some of the most common complications related to midurethral sling procedures.

Dr. Rardin is the director of the Robotic Surgery Program at Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island, in Providence; a surgeon in Women & Infants’ division of urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery; and is the director of the hospital’s fellowship urogynecology and reconstructive pelvic surgery.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller is a consultant and on the speaker’s bureau for Ethicon.

Over the past 2 decades, midurethral slings, both via a retropubic and a transobturator approach have become the first-line therapy for the surgical correction of female stress urinary incontinence. Not only are cure rates excellent for both techniques, but the incidence of complications are low.

Intraoperatively, major concerns include vascular lesions, nerve injuries, and injuries to the bowel. More minor concerns are related to the bladder.

Perioperative complications include retropubic hematoma, blood loss, urinary tract infection, and spondylitis. Postoperative risks include transient versus permanent urinary retention, vaginal versus urethral erosion, de novo urgency, bladder erosion, and urethral obstruction.

In this edition of Master Class in gynecologic surgery, I am pleased to solicit the help of Dr. Charles Rardin, who will make recommendations regarding the management of some of the most common complications related to midurethral sling procedures.

Dr. Rardin is the director of the Robotic Surgery Program at Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island, in Providence; a surgeon in Women & Infants’ division of urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery; and is the director of the hospital’s fellowship urogynecology and reconstructive pelvic surgery.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller is a consultant and on the speaker’s bureau for Ethicon.

Breaking down midurethral sling approaches

It has been nearly 20 years since the first minimally invasive midurethral sling was introduced. This development was followed 5 years later with the introduction of the transobturator midurethral sling. The advent of both ambulatory techniques has essentially changed the landscape in the surgical treatment of stress urinary incontinence; midurethral slings are certainly considered the procedure of choice for many women.

The midurethral sling has continued to evolve. Not only does the surgeon have the choice of placing a retropubic midurethral sling (bottom to top or top to bottom) and the transobturator midurethral sling (inside-out or outside-in), but, as of late, single incision midurethral slings (mini-slings or mini-tape) as well.

In the previous Master Class on urinary incontinence, Dr. Eric Sokol discussed issues of sling selection and the evidence in favor of various types of retropubic and transobturator slings. This month, we’ll discuss the technique behind these two approaches. I have elicited the assistance of Dr. Sokol, as well as Dr. Charles Rardin.

Dr. Sokol is an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology, associate professor of urology (by courtesy), and cochief of the division of urogynecology and pelvic reconstructive surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University. He has published many articles regarding urogynecology and minimally invasive surgery. Dr. Sokol has been awarded numerous teaching awards, and he is a reviewer for multiple prestigious, peer-reviewed journals.

Dr. Rardin is the director of the robotic surgery program at Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island, Providence, a surgeon in the division of urogynecology and reconstructive pelvic surgery, and is the director of the hospital’s fellowship in urogynecology and reconstructive pelvic surgery. He is also an assistant professor at Brown University, also in Providence. He has published numerous articles in peer-reviewed journals.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller is a consultant and on the speaker’s bureau for Ethicon.

It has been nearly 20 years since the first minimally invasive midurethral sling was introduced. This development was followed 5 years later with the introduction of the transobturator midurethral sling. The advent of both ambulatory techniques has essentially changed the landscape in the surgical treatment of stress urinary incontinence; midurethral slings are certainly considered the procedure of choice for many women.

The midurethral sling has continued to evolve. Not only does the surgeon have the choice of placing a retropubic midurethral sling (bottom to top or top to bottom) and the transobturator midurethral sling (inside-out or outside-in), but, as of late, single incision midurethral slings (mini-slings or mini-tape) as well.

In the previous Master Class on urinary incontinence, Dr. Eric Sokol discussed issues of sling selection and the evidence in favor of various types of retropubic and transobturator slings. This month, we’ll discuss the technique behind these two approaches. I have elicited the assistance of Dr. Sokol, as well as Dr. Charles Rardin.

Dr. Sokol is an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology, associate professor of urology (by courtesy), and cochief of the division of urogynecology and pelvic reconstructive surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University. He has published many articles regarding urogynecology and minimally invasive surgery. Dr. Sokol has been awarded numerous teaching awards, and he is a reviewer for multiple prestigious, peer-reviewed journals.

Dr. Rardin is the director of the robotic surgery program at Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island, Providence, a surgeon in the division of urogynecology and reconstructive pelvic surgery, and is the director of the hospital’s fellowship in urogynecology and reconstructive pelvic surgery. He is also an assistant professor at Brown University, also in Providence. He has published numerous articles in peer-reviewed journals.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller is a consultant and on the speaker’s bureau for Ethicon.

It has been nearly 20 years since the first minimally invasive midurethral sling was introduced. This development was followed 5 years later with the introduction of the transobturator midurethral sling. The advent of both ambulatory techniques has essentially changed the landscape in the surgical treatment of stress urinary incontinence; midurethral slings are certainly considered the procedure of choice for many women.

The midurethral sling has continued to evolve. Not only does the surgeon have the choice of placing a retropubic midurethral sling (bottom to top or top to bottom) and the transobturator midurethral sling (inside-out or outside-in), but, as of late, single incision midurethral slings (mini-slings or mini-tape) as well.

In the previous Master Class on urinary incontinence, Dr. Eric Sokol discussed issues of sling selection and the evidence in favor of various types of retropubic and transobturator slings. This month, we’ll discuss the technique behind these two approaches. I have elicited the assistance of Dr. Sokol, as well as Dr. Charles Rardin.

Dr. Sokol is an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology, associate professor of urology (by courtesy), and cochief of the division of urogynecology and pelvic reconstructive surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University. He has published many articles regarding urogynecology and minimally invasive surgery. Dr. Sokol has been awarded numerous teaching awards, and he is a reviewer for multiple prestigious, peer-reviewed journals.

Dr. Rardin is the director of the robotic surgery program at Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island, Providence, a surgeon in the division of urogynecology and reconstructive pelvic surgery, and is the director of the hospital’s fellowship in urogynecology and reconstructive pelvic surgery. He is also an assistant professor at Brown University, also in Providence. He has published numerous articles in peer-reviewed journals.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller is a consultant and on the speaker’s bureau for Ethicon.

Treatment of stress urinary incontinence

According to a 2004 article by Dr. Eric S. Rovner and Dr. Alan J. Wein, 200 different surgical procedures have been described to treat stress urinary incontinence (Rev. Urol. 2004;6(Suppl 3):S29-47). Two goals exist in such surgical procedures:

1. Urethra repositioning or stabilization of the urethra and bladder neck through creation of retropubic support that is impervious to intraabdominal pressure changes.

2. Augmentation of the ureteral resistance provided by the intrinsic sphincter unit, with or without impacting urethra and bladder neck support (sling vs. periurethral injectables, or a combination of the two).

Sling procedures were initially introduced almost a century ago and have recently become increasingly popular – in part, secondary to a decrease in associated morbidity. Unlike transabdominal or transvaginal urethropexy, a sling not only provides support to the vesicourethral junction, but also may create some aspect of urethral coaptation or compression.

Midurethral slings were introduced nearly 20 years ago. These procedures can be performed with a local anesthetic or with minimal regional anesthesia – thus, in an outpatient setting. In addition, midurethral slings are associated with decreased pain and postoperative convalescence.

I have asked Dr. Eric Russell Sokol to lead this state-of-the-art discussion on midurethral slings. Dr. Sokol is an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology, associate professor of urology (by courtesy), and cochief of the division of urogynecology and pelvic reconstructive surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University. He has published many articles regarding urogynecology and minimally invasive surgery. Dr. Sokol has been awarded numerous teaching awards, and he is a reviewer for multiple prestigious, peer-reviewed journals. It is a pleasure and an honor to welcome Dr. Sokol to this edition of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, the second installment on urinary incontinence.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller is a consultant and on the speaker’s bureau for Ethicon.

According to a 2004 article by Dr. Eric S. Rovner and Dr. Alan J. Wein, 200 different surgical procedures have been described to treat stress urinary incontinence (Rev. Urol. 2004;6(Suppl 3):S29-47). Two goals exist in such surgical procedures:

1. Urethra repositioning or stabilization of the urethra and bladder neck through creation of retropubic support that is impervious to intraabdominal pressure changes.

2. Augmentation of the ureteral resistance provided by the intrinsic sphincter unit, with or without impacting urethra and bladder neck support (sling vs. periurethral injectables, or a combination of the two).

Sling procedures were initially introduced almost a century ago and have recently become increasingly popular – in part, secondary to a decrease in associated morbidity. Unlike transabdominal or transvaginal urethropexy, a sling not only provides support to the vesicourethral junction, but also may create some aspect of urethral coaptation or compression.

Midurethral slings were introduced nearly 20 years ago. These procedures can be performed with a local anesthetic or with minimal regional anesthesia – thus, in an outpatient setting. In addition, midurethral slings are associated with decreased pain and postoperative convalescence.

I have asked Dr. Eric Russell Sokol to lead this state-of-the-art discussion on midurethral slings. Dr. Sokol is an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology, associate professor of urology (by courtesy), and cochief of the division of urogynecology and pelvic reconstructive surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University. He has published many articles regarding urogynecology and minimally invasive surgery. Dr. Sokol has been awarded numerous teaching awards, and he is a reviewer for multiple prestigious, peer-reviewed journals. It is a pleasure and an honor to welcome Dr. Sokol to this edition of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, the second installment on urinary incontinence.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller is a consultant and on the speaker’s bureau for Ethicon.

According to a 2004 article by Dr. Eric S. Rovner and Dr. Alan J. Wein, 200 different surgical procedures have been described to treat stress urinary incontinence (Rev. Urol. 2004;6(Suppl 3):S29-47). Two goals exist in such surgical procedures:

1. Urethra repositioning or stabilization of the urethra and bladder neck through creation of retropubic support that is impervious to intraabdominal pressure changes.

2. Augmentation of the ureteral resistance provided by the intrinsic sphincter unit, with or without impacting urethra and bladder neck support (sling vs. periurethral injectables, or a combination of the two).

Sling procedures were initially introduced almost a century ago and have recently become increasingly popular – in part, secondary to a decrease in associated morbidity. Unlike transabdominal or transvaginal urethropexy, a sling not only provides support to the vesicourethral junction, but also may create some aspect of urethral coaptation or compression.

Midurethral slings were introduced nearly 20 years ago. These procedures can be performed with a local anesthetic or with minimal regional anesthesia – thus, in an outpatient setting. In addition, midurethral slings are associated with decreased pain and postoperative convalescence.

I have asked Dr. Eric Russell Sokol to lead this state-of-the-art discussion on midurethral slings. Dr. Sokol is an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology, associate professor of urology (by courtesy), and cochief of the division of urogynecology and pelvic reconstructive surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University. He has published many articles regarding urogynecology and minimally invasive surgery. Dr. Sokol has been awarded numerous teaching awards, and he is a reviewer for multiple prestigious, peer-reviewed journals. It is a pleasure and an honor to welcome Dr. Sokol to this edition of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, the second installment on urinary incontinence.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller is a consultant and on the speaker’s bureau for Ethicon.

Hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation

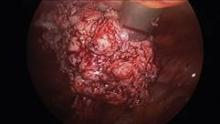

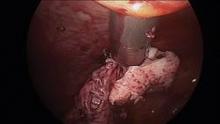

One of the hottest and most controversial topics in gynecologic surgery, at present, is laparoscopic electromechanical power morcellation.

In April of this year, the Food and Drug Administration sent out a news release regarding the potential risk of spread of sarcomatous tissue at the time of this procedure. In that release, the agency "discouraged" use of laparoscopic electromechanical power morcellation. Responses came from many societies, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the AAGL, which indicated that laparoscopic electromechanical power morcellation could be used if proper care was taken.

I am personally proud that the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery has been very proactive and diligent in its discussion of laparoscopic electromechanical power morcellation. This is the third in our series regarding this topic.

In our first segment, I discussed the issue of electromechanical power morcellation relative to the inadvertent spread of sarcomatous tissue. In our second in the series, Dr. Ceana Nezhat, Dr. Bernard Taylor, and Dr. Tony Shibley discussed ways to minimize this risk – including morcellation in a bag. Videos of their individual techniques of electromechanical power morcellation, as well as that of Dr. Douglas Brown, can be viewed on SurgeryU. In addition, my partner, Dr. Aarathi Cholkeri-Singh, and I have a video on SurgeryU illustrating our technique of morcellation in a bag.

This current Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery is now devoted to hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation. In my discussions with physicians throughout the country relative to this technique, it has become evident that some institutions have not only banned the use of electromechanical power morcellation at time of laparoscopy, but have also stopped usage of hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation. While neither the FDA nor the lay press has ever questioned the use of hysteroscopic morcellators, I believe it is imperative that this topic be reviewed. I am sure that it will be obvious that hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation has thus far proved to be a safe and effective treatment option for various pathologic entities, including submucosal uterine fibroids.

To review hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation, I have invited Dr. Joseph S. Sanfilippo, professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Pittsburgh and director of the division of reproductive endocrinology and infertility at Magee-Womens Hospital in Pittsburgh.

Dr. Sanfilippo is a lecturer and educator. He has written an extensive number of peer-reviewed articles, and has been a contributor to several textbooks. In addition, Dr. Sanfilippo has been and remains a very active member of the AAGL.

It is a pleasure and honor to welcome Dr. Sanfilippo to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, the third installment on morcellation.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy, and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller disclosed that he is a consultant to Hologic and is on the speakers bureau for Smith & Nephew. Videos for this and past Master Class in Gynecology Surgery articles can be viewed on SurgeryU.

One of the hottest and most controversial topics in gynecologic surgery, at present, is laparoscopic electromechanical power morcellation.

In April of this year, the Food and Drug Administration sent out a news release regarding the potential risk of spread of sarcomatous tissue at the time of this procedure. In that release, the agency "discouraged" use of laparoscopic electromechanical power morcellation. Responses came from many societies, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the AAGL, which indicated that laparoscopic electromechanical power morcellation could be used if proper care was taken.

I am personally proud that the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery has been very proactive and diligent in its discussion of laparoscopic electromechanical power morcellation. This is the third in our series regarding this topic.

In our first segment, I discussed the issue of electromechanical power morcellation relative to the inadvertent spread of sarcomatous tissue. In our second in the series, Dr. Ceana Nezhat, Dr. Bernard Taylor, and Dr. Tony Shibley discussed ways to minimize this risk – including morcellation in a bag. Videos of their individual techniques of electromechanical power morcellation, as well as that of Dr. Douglas Brown, can be viewed on SurgeryU. In addition, my partner, Dr. Aarathi Cholkeri-Singh, and I have a video on SurgeryU illustrating our technique of morcellation in a bag.

This current Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery is now devoted to hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation. In my discussions with physicians throughout the country relative to this technique, it has become evident that some institutions have not only banned the use of electromechanical power morcellation at time of laparoscopy, but have also stopped usage of hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation. While neither the FDA nor the lay press has ever questioned the use of hysteroscopic morcellators, I believe it is imperative that this topic be reviewed. I am sure that it will be obvious that hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation has thus far proved to be a safe and effective treatment option for various pathologic entities, including submucosal uterine fibroids.

To review hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation, I have invited Dr. Joseph S. Sanfilippo, professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Pittsburgh and director of the division of reproductive endocrinology and infertility at Magee-Womens Hospital in Pittsburgh.

Dr. Sanfilippo is a lecturer and educator. He has written an extensive number of peer-reviewed articles, and has been a contributor to several textbooks. In addition, Dr. Sanfilippo has been and remains a very active member of the AAGL.

It is a pleasure and honor to welcome Dr. Sanfilippo to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, the third installment on morcellation.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy, and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller disclosed that he is a consultant to Hologic and is on the speakers bureau for Smith & Nephew. Videos for this and past Master Class in Gynecology Surgery articles can be viewed on SurgeryU.

One of the hottest and most controversial topics in gynecologic surgery, at present, is laparoscopic electromechanical power morcellation.

In April of this year, the Food and Drug Administration sent out a news release regarding the potential risk of spread of sarcomatous tissue at the time of this procedure. In that release, the agency "discouraged" use of laparoscopic electromechanical power morcellation. Responses came from many societies, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the AAGL, which indicated that laparoscopic electromechanical power morcellation could be used if proper care was taken.

I am personally proud that the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery has been very proactive and diligent in its discussion of laparoscopic electromechanical power morcellation. This is the third in our series regarding this topic.

In our first segment, I discussed the issue of electromechanical power morcellation relative to the inadvertent spread of sarcomatous tissue. In our second in the series, Dr. Ceana Nezhat, Dr. Bernard Taylor, and Dr. Tony Shibley discussed ways to minimize this risk – including morcellation in a bag. Videos of their individual techniques of electromechanical power morcellation, as well as that of Dr. Douglas Brown, can be viewed on SurgeryU. In addition, my partner, Dr. Aarathi Cholkeri-Singh, and I have a video on SurgeryU illustrating our technique of morcellation in a bag.

This current Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery is now devoted to hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation. In my discussions with physicians throughout the country relative to this technique, it has become evident that some institutions have not only banned the use of electromechanical power morcellation at time of laparoscopy, but have also stopped usage of hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation. While neither the FDA nor the lay press has ever questioned the use of hysteroscopic morcellators, I believe it is imperative that this topic be reviewed. I am sure that it will be obvious that hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation has thus far proved to be a safe and effective treatment option for various pathologic entities, including submucosal uterine fibroids.

To review hysteroscopic electromechanical power morcellation, I have invited Dr. Joseph S. Sanfilippo, professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Pittsburgh and director of the division of reproductive endocrinology and infertility at Magee-Womens Hospital in Pittsburgh.

Dr. Sanfilippo is a lecturer and educator. He has written an extensive number of peer-reviewed articles, and has been a contributor to several textbooks. In addition, Dr. Sanfilippo has been and remains a very active member of the AAGL.

It is a pleasure and honor to welcome Dr. Sanfilippo to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, the third installment on morcellation.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy, and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller disclosed that he is a consultant to Hologic and is on the speakers bureau for Smith & Nephew. Videos for this and past Master Class in Gynecology Surgery articles can be viewed on SurgeryU.

Electromechanical power morcellation confined to a bag

In the previous edition of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I described the controversy concerning electromechanical power morcellation freely in the abdominopelvic cavity. I also discussed the risks, as noted in the literature, of spreading an unsuspected leiomyosarcoma, and thus, up-staging the disease and lowering both the length of the disease-free state and the overall survival. I also talked about the lack of an adequate diagnostic study to definitively separate a leiomyoma from a leiomyosarcoma, discussed the at-risk population group, and also noted the benefits of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery. At that time, I stated I was against a ban on the morcellator, and that I recommended that physicians provide proper informed consent and, when possible, consider other treatment options, especially in the at-risk population. These included continued use of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery utilizing a specimen bag for electromechanical power morcellation.

Following that publication, the Food and Drug Administration released a statement regarding electromechanical power morcellation on April 17, 2014. While "discouraging" the use of electromechanical power morcellation, they wisely did not call for a moratorium. Again, the FDA recommended that patients be properly informed as to risk and that alternative therapies be discussed, which included the use of power morcellation in a bag.

While the FDA did not ban electromechanical power morcellation, the phrase "discourages the use" sent widespread ripples throughout our specialty. Within a week, Ethicon Endo-Surgery pulled its morcellator off the market worldwide. My hospital system – Advocate Health Care – as well as virtually every hospital in Boston placed a moratorium on electromechanical power morcellation. Dr. Jim Tsaltas, president of the Australian Gynecological Endoscopy & Surgery Society (AGES), was contacted by his country’s FDA equivalent to discuss the use of power morcellation freely in the abdominopelvic cavity.

Since the letter from the FDA, position papers have come from both the world’s largest society focused on minimally invasive surgery, the AAGL, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Both of the society’s statements agree that proper informed consent is imperative and that alternate treatment be considered, especially in the at-risk population. Although both papers discuss the use of electromechanical power morcellation in the confines of a bag, the ACOG statement accurately notes that there is very little data regarding morcellation in a bag placed in the abdominopelvic cavity.

Experience with electromechanical power morcellation in a bag placed in the abdominopelvic cavity is now quickly developing. To quote my coauthor, Dr. Ceana Nezhat, "My goal with this Master Class is to provide a forum for discussion and encourage gynecologic surgeons to continue to practice minimally invasive surgery for the benefit of their patients. Despite the current limitation on unprotected, intraperitoneal electromechanical morcellation, the hope is that surgeons will not revert back to laparotomy, but will continue to learn and find innovative ways to provide the least invasive surgical techniques or refer to centers that can provide these services to women."

In this edition of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I am featuring techniques of electromechanical power morcellation in a specimen bag by early adapters and innovators, and other techniques by Dr. Tony Shibley, Dr. Bernard Taylor, and Dr. Ceana H. Nezhat.

Dr. Shibley has been in full-time practice with Ob.Gyn. Specialists, Fairview Health Services in the Minneapolis area (Edina), for the past 20 years. He has a focus on single-site surgery and has been involved in minimally invasive surgical education both nationally and internationally, as well as in medical device development.

Dr. Taylor is a urogynecologist who is a female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgeon practicing at the Carolinas Medical Center–Advanced Surgical Specialties for Women in Charlotte, N.C. He lectures nationally and internationally on minimally invasive gynecologic surgery.

Dr. Nezhat is the current president of the AAGL, adjunct professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Emory University and program director of minimally invasive surgery at Northside Hospital, both in Atlanta, and adjunct clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy, and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column. Dr. Miller disclosed that he is a consultant to Ethicon Endo-Surgery.

Videos of our experts’ individual techniques of electromechanical power morcellation within the confines of a bag, as well as that of Dr. Douglas Brown, director of the Center for Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, can be viewed at the SurgeryU website. Also at SurgeryU is a video of the electromechanical power morcellation technique in a bag that my partner, Dr. Aarathi Cholkeri-Singh, and I utilize. We use a 3,100-cc ripstop nylon specimen bag from Espiner Medical and the 5 x 150 mm, extra-long, shielded-bladed balloon-tipped trocar from Applied Medical. Go to SurgeryU to view videos of the procedures.

In the previous edition of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I described the controversy concerning electromechanical power morcellation freely in the abdominopelvic cavity. I also discussed the risks, as noted in the literature, of spreading an unsuspected leiomyosarcoma, and thus, up-staging the disease and lowering both the length of the disease-free state and the overall survival. I also talked about the lack of an adequate diagnostic study to definitively separate a leiomyoma from a leiomyosarcoma, discussed the at-risk population group, and also noted the benefits of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery. At that time, I stated I was against a ban on the morcellator, and that I recommended that physicians provide proper informed consent and, when possible, consider other treatment options, especially in the at-risk population. These included continued use of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery utilizing a specimen bag for electromechanical power morcellation.

Following that publication, the Food and Drug Administration released a statement regarding electromechanical power morcellation on April 17, 2014. While "discouraging" the use of electromechanical power morcellation, they wisely did not call for a moratorium. Again, the FDA recommended that patients be properly informed as to risk and that alternative therapies be discussed, which included the use of power morcellation in a bag.

While the FDA did not ban electromechanical power morcellation, the phrase "discourages the use" sent widespread ripples throughout our specialty. Within a week, Ethicon Endo-Surgery pulled its morcellator off the market worldwide. My hospital system – Advocate Health Care – as well as virtually every hospital in Boston placed a moratorium on electromechanical power morcellation. Dr. Jim Tsaltas, president of the Australian Gynecological Endoscopy & Surgery Society (AGES), was contacted by his country’s FDA equivalent to discuss the use of power morcellation freely in the abdominopelvic cavity.

Since the letter from the FDA, position papers have come from both the world’s largest society focused on minimally invasive surgery, the AAGL, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Both of the society’s statements agree that proper informed consent is imperative and that alternate treatment be considered, especially in the at-risk population. Although both papers discuss the use of electromechanical power morcellation in the confines of a bag, the ACOG statement accurately notes that there is very little data regarding morcellation in a bag placed in the abdominopelvic cavity.

Experience with electromechanical power morcellation in a bag placed in the abdominopelvic cavity is now quickly developing. To quote my coauthor, Dr. Ceana Nezhat, "My goal with this Master Class is to provide a forum for discussion and encourage gynecologic surgeons to continue to practice minimally invasive surgery for the benefit of their patients. Despite the current limitation on unprotected, intraperitoneal electromechanical morcellation, the hope is that surgeons will not revert back to laparotomy, but will continue to learn and find innovative ways to provide the least invasive surgical techniques or refer to centers that can provide these services to women."

In this edition of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I am featuring techniques of electromechanical power morcellation in a specimen bag by early adapters and innovators, and other techniques by Dr. Tony Shibley, Dr. Bernard Taylor, and Dr. Ceana H. Nezhat.

Dr. Shibley has been in full-time practice with Ob.Gyn. Specialists, Fairview Health Services in the Minneapolis area (Edina), for the past 20 years. He has a focus on single-site surgery and has been involved in minimally invasive surgical education both nationally and internationally, as well as in medical device development.

Dr. Taylor is a urogynecologist who is a female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgeon practicing at the Carolinas Medical Center–Advanced Surgical Specialties for Women in Charlotte, N.C. He lectures nationally and internationally on minimally invasive gynecologic surgery.

Dr. Nezhat is the current president of the AAGL, adjunct professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Emory University and program director of minimally invasive surgery at Northside Hospital, both in Atlanta, and adjunct clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy, and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column. Dr. Miller disclosed that he is a consultant to Ethicon Endo-Surgery.

Videos of our experts’ individual techniques of electromechanical power morcellation within the confines of a bag, as well as that of Dr. Douglas Brown, director of the Center for Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, can be viewed at the SurgeryU website. Also at SurgeryU is a video of the electromechanical power morcellation technique in a bag that my partner, Dr. Aarathi Cholkeri-Singh, and I utilize. We use a 3,100-cc ripstop nylon specimen bag from Espiner Medical and the 5 x 150 mm, extra-long, shielded-bladed balloon-tipped trocar from Applied Medical. Go to SurgeryU to view videos of the procedures.

In the previous edition of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I described the controversy concerning electromechanical power morcellation freely in the abdominopelvic cavity. I also discussed the risks, as noted in the literature, of spreading an unsuspected leiomyosarcoma, and thus, up-staging the disease and lowering both the length of the disease-free state and the overall survival. I also talked about the lack of an adequate diagnostic study to definitively separate a leiomyoma from a leiomyosarcoma, discussed the at-risk population group, and also noted the benefits of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery. At that time, I stated I was against a ban on the morcellator, and that I recommended that physicians provide proper informed consent and, when possible, consider other treatment options, especially in the at-risk population. These included continued use of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery utilizing a specimen bag for electromechanical power morcellation.

Following that publication, the Food and Drug Administration released a statement regarding electromechanical power morcellation on April 17, 2014. While "discouraging" the use of electromechanical power morcellation, they wisely did not call for a moratorium. Again, the FDA recommended that patients be properly informed as to risk and that alternative therapies be discussed, which included the use of power morcellation in a bag.

While the FDA did not ban electromechanical power morcellation, the phrase "discourages the use" sent widespread ripples throughout our specialty. Within a week, Ethicon Endo-Surgery pulled its morcellator off the market worldwide. My hospital system – Advocate Health Care – as well as virtually every hospital in Boston placed a moratorium on electromechanical power morcellation. Dr. Jim Tsaltas, president of the Australian Gynecological Endoscopy & Surgery Society (AGES), was contacted by his country’s FDA equivalent to discuss the use of power morcellation freely in the abdominopelvic cavity.

Since the letter from the FDA, position papers have come from both the world’s largest society focused on minimally invasive surgery, the AAGL, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Both of the society’s statements agree that proper informed consent is imperative and that alternate treatment be considered, especially in the at-risk population. Although both papers discuss the use of electromechanical power morcellation in the confines of a bag, the ACOG statement accurately notes that there is very little data regarding morcellation in a bag placed in the abdominopelvic cavity.

Experience with electromechanical power morcellation in a bag placed in the abdominopelvic cavity is now quickly developing. To quote my coauthor, Dr. Ceana Nezhat, "My goal with this Master Class is to provide a forum for discussion and encourage gynecologic surgeons to continue to practice minimally invasive surgery for the benefit of their patients. Despite the current limitation on unprotected, intraperitoneal electromechanical morcellation, the hope is that surgeons will not revert back to laparotomy, but will continue to learn and find innovative ways to provide the least invasive surgical techniques or refer to centers that can provide these services to women."

In this edition of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I am featuring techniques of electromechanical power morcellation in a specimen bag by early adapters and innovators, and other techniques by Dr. Tony Shibley, Dr. Bernard Taylor, and Dr. Ceana H. Nezhat.

Dr. Shibley has been in full-time practice with Ob.Gyn. Specialists, Fairview Health Services in the Minneapolis area (Edina), for the past 20 years. He has a focus on single-site surgery and has been involved in minimally invasive surgical education both nationally and internationally, as well as in medical device development.

Dr. Taylor is a urogynecologist who is a female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgeon practicing at the Carolinas Medical Center–Advanced Surgical Specialties for Women in Charlotte, N.C. He lectures nationally and internationally on minimally invasive gynecologic surgery.

Dr. Nezhat is the current president of the AAGL, adjunct professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Emory University and program director of minimally invasive surgery at Northside Hospital, both in Atlanta, and adjunct clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy, and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column. Dr. Miller disclosed that he is a consultant to Ethicon Endo-Surgery.

Videos of our experts’ individual techniques of electromechanical power morcellation within the confines of a bag, as well as that of Dr. Douglas Brown, director of the Center for Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, can be viewed at the SurgeryU website. Also at SurgeryU is a video of the electromechanical power morcellation technique in a bag that my partner, Dr. Aarathi Cholkeri-Singh, and I utilize. We use a 3,100-cc ripstop nylon specimen bag from Espiner Medical and the 5 x 150 mm, extra-long, shielded-bladed balloon-tipped trocar from Applied Medical. Go to SurgeryU to view videos of the procedures.

Putting morcellation into perspective – ‘Just the facts, Ma’am, nothing but the facts’

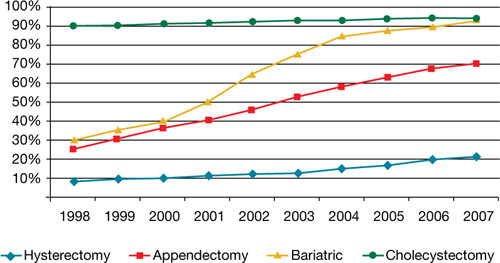

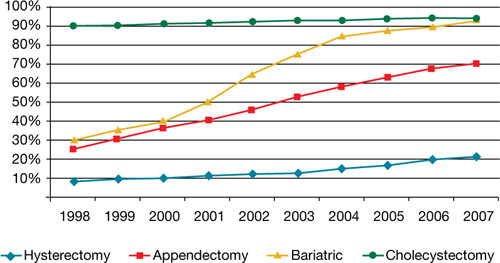

Intra-abdominal (intracorporeal) morcellation, especially electronically powered morcellation, has recently come under scrutiny. Generally performed at the time of conventional laparoscopic or robotic supracervical hysterectomy, total hysterectomy for the large uterus, or myomectomy, both power and cold-knife morcellation may splatter tissue fragments in the pelvis and abdomen, leading to potential parasitizing of the tissue and ectopic growth. Recent evidence indicates inadvertent morcellation of a leiomyosarcoma may negatively affect the patient’s subsequent disease-free survival and overall survival.

Concerns about morcellation heightened after Dr. Amy J. Reed, an anesthesiologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, and a mother of 6, underwent presumed fibroid surgery and was diagnosed, post morcellation, with leiomyosarcoma. Dr. Reed’s husband, Dr. Hooman Noorchashm, a cardiothoracic surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, where his wife’s surgery was performed, is calling for a moratorium on intra-abdominal morcellation, whether it involves the use of a power morcellator, or for that matter, the cold knife.

It is imperative and incumbent upon our specialty to have a detailed evaluation of the risks and benefits of morcellation. While morcellation of the rare leiomyosarcoma is a risk, banning intraabdominal/intrapelvic morcellation will certainly have a profound negative impact on patients who are able to undergo a minimally invasive gynecologic procedure. Banning morcellation would increase intraoperative risk and subsequent concern of postoperative pelvic adhesions and thus, potential impact on fertility (post myomectomy), dyspareunia, and pelvic pain. Further, a ban would incur higher costs and more loss of patient productivity (Hum. Reprod. 1998 13:2102-6). These concerns were the basis for the AAGL position statement touting a minimally invasive approach to hysterectomy (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:1-3).

Since their introduction in the mid-1990s, electronically powered morcellators have been used to remove the uterus, fibroid(s), spleen, or kidney. Varying in size from 12-20 mm, electronic morcellators generally consist of a rotating circular blade at the end of a hollow tube. A tenaculum or multitoothed grasper is placed through the tube and blade to grasp the tissue to the revolving blade. The specimen is then removed in strips. Tissue splatter is inevitable, at least until the technique evolves to allow morcellation to be performed within the confines of a bag.

Benign uterine fibroids are the most common pelvic tumor in women. Literature reviews indicate the lifetime risk is 70% for white women and 80% in women of African ancestry. Uterine sarcomas occur in 3-7 women per 100,000 (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;205:492.e1-5). Further, Dr. Kimberly A. Kho of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and Dr. Ceana H. Dr. Nezhat of Atlanta Center for Minimally Invasive Surgery and Reproductive Medicine, conducted a meta-analysis of 5,666 uterine procedures, and found 13 unsuspected uterine sarcomas, for a prevalence of 0.23% (JAMA 2014 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.1093]).

This finding is consistent with that of a previous study by Dr. W.H. Parker who also noted a 0.23% risk, based on data from 1,332 women undergoing surgery secondary to uterine fibroids. Interestingly, in Dr. Parker’s study, the risk was 0.27% among women with rapidly growing leiomyoma, often thought to be a risk factor for sarcoma development (Obstet. Gynecol. 1994;83:414-8).

Because of the difficulty of making a preoperative diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma, it is doubtful that this risk will be decreased in the near future. Risk factors have not been well established, although a twofold higher incidence of leiomyosarcomas has been observed in black women (Gynecol. Oncol. 2004;93:204-8). Increasing age would appear to increase uterine sarcoma risk, as the majority of cases are diagnosed in postmenopausal women. Tamoxifen, when used for 5 or more years, appears to be associated with higher sarcoma rates (J. Clin. Oncol. 2002;20:2758-60) as is a history of pelvic irradiation or childhood retinoblastoma.

Unless metastatic disease is present, symptoms are similar for leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas. A rapidly growing mass, a finding associated with an increased risk of uterine sarcoma, was not seen in Parker’s study of 1,332 women undergoing hysterectomy or myomectomy for uterine leiomyoma. Similarly, size does not count; a large uterine mass or increased uterine size did not appear to be associated with a greater risk of sarcoma (Gynecol. Oncol. 2003;89:460-9).

Some contend that failed response with such therapies as gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and uterine artery embolization are associated with increased incidence of leiomyosarcoma, but the data are not convincing (Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1998;76:237-40).

Physical examination and imaging may be helpful in finding enlarged lymph nodes, but imaging methods have not been reliably shown to enable a preoperative diagnosis of uterine leiomyosarcoma (Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1188-98; AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2003;181:1369-74). Further, while some physicians point out that an ill-defined margin may increase leiomyosarcoma risk, this finding is certainly noted as well with benign adenomyomas.

Finally, data are scant in support of preoperative endometrial sampling to establish a diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma. In two studies comparing a total of 14 patients, 7 were correctly diagnosed with leiomyosarcoma prior to surgery (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1990;162:968-74; Gynecol. Oncol. 2008;110:43-8).

With little differentiation in clinical presentation and the inability to distinguish leiomyoma from leiomyosarcoma based on imaging or sampling, it is not surprising that patients undergoing morcellation for an expected benign condition would subsequently be diagnosed with uterine leiomyosarcoma. With this in mind, it is important to review the current body of literature to further evaluate the risks and benefits of morcellation, and what place minimally invasive gynecologic surgery will have for the treatment of uterine masses.

Tumor morcellation of unrecognized leiomyosarcomas was significantly associated with poorer disease free survival (odds ratio, 2.59, P = 1.43), higher stage (I vs. II; [OR, 19.12, P = .037]) and poorer overall survival (OR, 3.07, P =.040) in a 2011 study. Park et al. assessed 56 consecutive patients, 25 with morcellation and 31 without tumor morcellation, who had stage I and stage II uterine leiomyosarcomas and were treated between 1989 and 2010. The percentage of patients with dissemination also was noted to be greater in patients with tumor morcellation (44% vs. 12.9%, P =.032). Interestingly, ovarian tissue was more frequently preserved in the morcellation group (38.7% vs. 72%, P =.013) (Gynecol. Oncol. 2011;122:255-9)

In response to a subsequent Letter to the Editor about these risks, the study’s author put the findings in perspective. "The frequency of incidental uterine leiomyosarcoma in patients who undergo surgery for presumed uterine leiomyoma is extremely rare. At our medical center, only 49 of 22,825 patients (0.21%) who underwent surgery for presumed uterine leiomyoma had incidental uterine leiomyosarcoma. Therefore, we believe that surgeons need not avoid non-laparotomic* surgical routes because of the rare possibility of an incidental diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma, even when tumor morcellation is required" (Gynecol. Oncol. 2012;124:172-3).

Additionally, a retrospective study from Brigham & Women’s Hospital found that disease was often already disseminated before morcellation procedures. In 21 patients with a median age of 46 years and no documented evidence of extrauterine disease, 15 had uterine leiomyosarcomas and 6 had smooth muscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential that were inadvertently morcellated; data was incorporated from January 2005 to January 2012. While most patients underwent power morcellation with laparoscopy, two underwent laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy with hand morcellation, and one patient had a vaginal hysterectomy with hand morcellation.

Immediate surgical reexploration was performed for staging in 12 patients. Significant findings of disseminated intraperitoneal disease were detected in two of seven patients with presumed stage I uterine leiomyosarcoma and in one of four patients with presumed stage I smooth muscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential. Moreover, of the eight patients who did not have disseminated disease at the time of the staging procedure, one subsequently had a recurrence. The remaining patients had no recurrences and remain disease free.

One patient was already FIGO stage IV at the original surgery, two more patients were upstaged at the original surgery and underwent re-exploration at 18 and 20 months respectively (certainly, a long period prior to second look). Moreover, the authors note various reasons why a significant number of patients were upstaged; including incorrect staging after initial surgery, progression of disease during the time interval, or secondary to direct seeding of morcellated tumor fragments. Five of the 15 leiomyosarcoma patients were deceased at the time of the publication. The authors also point out that their study is limited by the fact that it is retrospective, and access to information regarding care received from non-affiliated institutions is limited (Gynecol. Oncol. 2014;132:360-5).

In summary, morcellation of an unsuspected uterine sarcoma, whether using an electrically powered morcellator at the time of laparoscopy or cold knife at time of vaginal surgery, appears to have a negative impact; however, the studies to date are merely retrospective case studies. By no means do they provide the evidence required to place a moratorium on morcellation.

Further, if such a ban is imposed, would it then not be equally justifiable to pose similar regulations on use of oral contraceptives for symptom relief, endometrial ablation when fibroids are involved, or for that matter, uterine artery embolization? All these potential treatment regimens delay diagnosis and treatment and leave the potential uterine sarcoma in situ.

In the end, while the disease-free survival as well as overall survival appears to be hindered by dissemination of leiomyosarcoma at time of both electronic and cold-knife morcellation, the diagnosis is fortunately rare. A moratorium on the technique, however, would increase the number of concomitant laparotomies that would be required, and along with it, the increased inherent risk as well as prolonged recovery. At the present time, without better diagnostic tools or safer morcellation techniques, it is imperative to have an open dialogue of the risks and benefits of morcellation and minimally invasive surgery with patients presenting with anticipated fibroids. Additionally, our industry partners must be empowered to create safer morcellation techniques. This would appear to be morcellation within a bag.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy, and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column. Dr. Miller said he is a consultant for Ethicon, which manufactures a morcellator.

*Correction, 3/19/2014: An earlier version of this story misstated the type of surgical route.

Intra-abdominal (intracorporeal) morcellation, especially electronically powered morcellation, has recently come under scrutiny. Generally performed at the time of conventional laparoscopic or robotic supracervical hysterectomy, total hysterectomy for the large uterus, or myomectomy, both power and cold-knife morcellation may splatter tissue fragments in the pelvis and abdomen, leading to potential parasitizing of the tissue and ectopic growth. Recent evidence indicates inadvertent morcellation of a leiomyosarcoma may negatively affect the patient’s subsequent disease-free survival and overall survival.

Concerns about morcellation heightened after Dr. Amy J. Reed, an anesthesiologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, and a mother of 6, underwent presumed fibroid surgery and was diagnosed, post morcellation, with leiomyosarcoma. Dr. Reed’s husband, Dr. Hooman Noorchashm, a cardiothoracic surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, where his wife’s surgery was performed, is calling for a moratorium on intra-abdominal morcellation, whether it involves the use of a power morcellator, or for that matter, the cold knife.

It is imperative and incumbent upon our specialty to have a detailed evaluation of the risks and benefits of morcellation. While morcellation of the rare leiomyosarcoma is a risk, banning intraabdominal/intrapelvic morcellation will certainly have a profound negative impact on patients who are able to undergo a minimally invasive gynecologic procedure. Banning morcellation would increase intraoperative risk and subsequent concern of postoperative pelvic adhesions and thus, potential impact on fertility (post myomectomy), dyspareunia, and pelvic pain. Further, a ban would incur higher costs and more loss of patient productivity (Hum. Reprod. 1998 13:2102-6). These concerns were the basis for the AAGL position statement touting a minimally invasive approach to hysterectomy (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:1-3).

Since their introduction in the mid-1990s, electronically powered morcellators have been used to remove the uterus, fibroid(s), spleen, or kidney. Varying in size from 12-20 mm, electronic morcellators generally consist of a rotating circular blade at the end of a hollow tube. A tenaculum or multitoothed grasper is placed through the tube and blade to grasp the tissue to the revolving blade. The specimen is then removed in strips. Tissue splatter is inevitable, at least until the technique evolves to allow morcellation to be performed within the confines of a bag.

Benign uterine fibroids are the most common pelvic tumor in women. Literature reviews indicate the lifetime risk is 70% for white women and 80% in women of African ancestry. Uterine sarcomas occur in 3-7 women per 100,000 (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;205:492.e1-5). Further, Dr. Kimberly A. Kho of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and Dr. Ceana H. Dr. Nezhat of Atlanta Center for Minimally Invasive Surgery and Reproductive Medicine, conducted a meta-analysis of 5,666 uterine procedures, and found 13 unsuspected uterine sarcomas, for a prevalence of 0.23% (JAMA 2014 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.1093]).

This finding is consistent with that of a previous study by Dr. W.H. Parker who also noted a 0.23% risk, based on data from 1,332 women undergoing surgery secondary to uterine fibroids. Interestingly, in Dr. Parker’s study, the risk was 0.27% among women with rapidly growing leiomyoma, often thought to be a risk factor for sarcoma development (Obstet. Gynecol. 1994;83:414-8).

Because of the difficulty of making a preoperative diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma, it is doubtful that this risk will be decreased in the near future. Risk factors have not been well established, although a twofold higher incidence of leiomyosarcomas has been observed in black women (Gynecol. Oncol. 2004;93:204-8). Increasing age would appear to increase uterine sarcoma risk, as the majority of cases are diagnosed in postmenopausal women. Tamoxifen, when used for 5 or more years, appears to be associated with higher sarcoma rates (J. Clin. Oncol. 2002;20:2758-60) as is a history of pelvic irradiation or childhood retinoblastoma.

Unless metastatic disease is present, symptoms are similar for leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas. A rapidly growing mass, a finding associated with an increased risk of uterine sarcoma, was not seen in Parker’s study of 1,332 women undergoing hysterectomy or myomectomy for uterine leiomyoma. Similarly, size does not count; a large uterine mass or increased uterine size did not appear to be associated with a greater risk of sarcoma (Gynecol. Oncol. 2003;89:460-9).

Some contend that failed response with such therapies as gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and uterine artery embolization are associated with increased incidence of leiomyosarcoma, but the data are not convincing (Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1998;76:237-40).

Physical examination and imaging may be helpful in finding enlarged lymph nodes, but imaging methods have not been reliably shown to enable a preoperative diagnosis of uterine leiomyosarcoma (Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1188-98; AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2003;181:1369-74). Further, while some physicians point out that an ill-defined margin may increase leiomyosarcoma risk, this finding is certainly noted as well with benign adenomyomas.

Finally, data are scant in support of preoperative endometrial sampling to establish a diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma. In two studies comparing a total of 14 patients, 7 were correctly diagnosed with leiomyosarcoma prior to surgery (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1990;162:968-74; Gynecol. Oncol. 2008;110:43-8).

With little differentiation in clinical presentation and the inability to distinguish leiomyoma from leiomyosarcoma based on imaging or sampling, it is not surprising that patients undergoing morcellation for an expected benign condition would subsequently be diagnosed with uterine leiomyosarcoma. With this in mind, it is important to review the current body of literature to further evaluate the risks and benefits of morcellation, and what place minimally invasive gynecologic surgery will have for the treatment of uterine masses.

Tumor morcellation of unrecognized leiomyosarcomas was significantly associated with poorer disease free survival (odds ratio, 2.59, P = 1.43), higher stage (I vs. II; [OR, 19.12, P = .037]) and poorer overall survival (OR, 3.07, P =.040) in a 2011 study. Park et al. assessed 56 consecutive patients, 25 with morcellation and 31 without tumor morcellation, who had stage I and stage II uterine leiomyosarcomas and were treated between 1989 and 2010. The percentage of patients with dissemination also was noted to be greater in patients with tumor morcellation (44% vs. 12.9%, P =.032). Interestingly, ovarian tissue was more frequently preserved in the morcellation group (38.7% vs. 72%, P =.013) (Gynecol. Oncol. 2011;122:255-9)

In response to a subsequent Letter to the Editor about these risks, the study’s author put the findings in perspective. "The frequency of incidental uterine leiomyosarcoma in patients who undergo surgery for presumed uterine leiomyoma is extremely rare. At our medical center, only 49 of 22,825 patients (0.21%) who underwent surgery for presumed uterine leiomyoma had incidental uterine leiomyosarcoma. Therefore, we believe that surgeons need not avoid non-laparotomic* surgical routes because of the rare possibility of an incidental diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma, even when tumor morcellation is required" (Gynecol. Oncol. 2012;124:172-3).

Additionally, a retrospective study from Brigham & Women’s Hospital found that disease was often already disseminated before morcellation procedures. In 21 patients with a median age of 46 years and no documented evidence of extrauterine disease, 15 had uterine leiomyosarcomas and 6 had smooth muscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential that were inadvertently morcellated; data was incorporated from January 2005 to January 2012. While most patients underwent power morcellation with laparoscopy, two underwent laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy with hand morcellation, and one patient had a vaginal hysterectomy with hand morcellation.

Immediate surgical reexploration was performed for staging in 12 patients. Significant findings of disseminated intraperitoneal disease were detected in two of seven patients with presumed stage I uterine leiomyosarcoma and in one of four patients with presumed stage I smooth muscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential. Moreover, of the eight patients who did not have disseminated disease at the time of the staging procedure, one subsequently had a recurrence. The remaining patients had no recurrences and remain disease free.

One patient was already FIGO stage IV at the original surgery, two more patients were upstaged at the original surgery and underwent re-exploration at 18 and 20 months respectively (certainly, a long period prior to second look). Moreover, the authors note various reasons why a significant number of patients were upstaged; including incorrect staging after initial surgery, progression of disease during the time interval, or secondary to direct seeding of morcellated tumor fragments. Five of the 15 leiomyosarcoma patients were deceased at the time of the publication. The authors also point out that their study is limited by the fact that it is retrospective, and access to information regarding care received from non-affiliated institutions is limited (Gynecol. Oncol. 2014;132:360-5).

In summary, morcellation of an unsuspected uterine sarcoma, whether using an electrically powered morcellator at the time of laparoscopy or cold knife at time of vaginal surgery, appears to have a negative impact; however, the studies to date are merely retrospective case studies. By no means do they provide the evidence required to place a moratorium on morcellation.

Further, if such a ban is imposed, would it then not be equally justifiable to pose similar regulations on use of oral contraceptives for symptom relief, endometrial ablation when fibroids are involved, or for that matter, uterine artery embolization? All these potential treatment regimens delay diagnosis and treatment and leave the potential uterine sarcoma in situ.

In the end, while the disease-free survival as well as overall survival appears to be hindered by dissemination of leiomyosarcoma at time of both electronic and cold-knife morcellation, the diagnosis is fortunately rare. A moratorium on the technique, however, would increase the number of concomitant laparotomies that would be required, and along with it, the increased inherent risk as well as prolonged recovery. At the present time, without better diagnostic tools or safer morcellation techniques, it is imperative to have an open dialogue of the risks and benefits of morcellation and minimally invasive surgery with patients presenting with anticipated fibroids. Additionally, our industry partners must be empowered to create safer morcellation techniques. This would appear to be morcellation within a bag.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy, and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column. Dr. Miller said he is a consultant for Ethicon, which manufactures a morcellator.

*Correction, 3/19/2014: An earlier version of this story misstated the type of surgical route.

Intra-abdominal (intracorporeal) morcellation, especially electronically powered morcellation, has recently come under scrutiny. Generally performed at the time of conventional laparoscopic or robotic supracervical hysterectomy, total hysterectomy for the large uterus, or myomectomy, both power and cold-knife morcellation may splatter tissue fragments in the pelvis and abdomen, leading to potential parasitizing of the tissue and ectopic growth. Recent evidence indicates inadvertent morcellation of a leiomyosarcoma may negatively affect the patient’s subsequent disease-free survival and overall survival.

Concerns about morcellation heightened after Dr. Amy J. Reed, an anesthesiologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, and a mother of 6, underwent presumed fibroid surgery and was diagnosed, post morcellation, with leiomyosarcoma. Dr. Reed’s husband, Dr. Hooman Noorchashm, a cardiothoracic surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, where his wife’s surgery was performed, is calling for a moratorium on intra-abdominal morcellation, whether it involves the use of a power morcellator, or for that matter, the cold knife.

It is imperative and incumbent upon our specialty to have a detailed evaluation of the risks and benefits of morcellation. While morcellation of the rare leiomyosarcoma is a risk, banning intraabdominal/intrapelvic morcellation will certainly have a profound negative impact on patients who are able to undergo a minimally invasive gynecologic procedure. Banning morcellation would increase intraoperative risk and subsequent concern of postoperative pelvic adhesions and thus, potential impact on fertility (post myomectomy), dyspareunia, and pelvic pain. Further, a ban would incur higher costs and more loss of patient productivity (Hum. Reprod. 1998 13:2102-6). These concerns were the basis for the AAGL position statement touting a minimally invasive approach to hysterectomy (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:1-3).

Since their introduction in the mid-1990s, electronically powered morcellators have been used to remove the uterus, fibroid(s), spleen, or kidney. Varying in size from 12-20 mm, electronic morcellators generally consist of a rotating circular blade at the end of a hollow tube. A tenaculum or multitoothed grasper is placed through the tube and blade to grasp the tissue to the revolving blade. The specimen is then removed in strips. Tissue splatter is inevitable, at least until the technique evolves to allow morcellation to be performed within the confines of a bag.

Benign uterine fibroids are the most common pelvic tumor in women. Literature reviews indicate the lifetime risk is 70% for white women and 80% in women of African ancestry. Uterine sarcomas occur in 3-7 women per 100,000 (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;205:492.e1-5). Further, Dr. Kimberly A. Kho of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and Dr. Ceana H. Dr. Nezhat of Atlanta Center for Minimally Invasive Surgery and Reproductive Medicine, conducted a meta-analysis of 5,666 uterine procedures, and found 13 unsuspected uterine sarcomas, for a prevalence of 0.23% (JAMA 2014 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.1093]).

This finding is consistent with that of a previous study by Dr. W.H. Parker who also noted a 0.23% risk, based on data from 1,332 women undergoing surgery secondary to uterine fibroids. Interestingly, in Dr. Parker’s study, the risk was 0.27% among women with rapidly growing leiomyoma, often thought to be a risk factor for sarcoma development (Obstet. Gynecol. 1994;83:414-8).

Because of the difficulty of making a preoperative diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma, it is doubtful that this risk will be decreased in the near future. Risk factors have not been well established, although a twofold higher incidence of leiomyosarcomas has been observed in black women (Gynecol. Oncol. 2004;93:204-8). Increasing age would appear to increase uterine sarcoma risk, as the majority of cases are diagnosed in postmenopausal women. Tamoxifen, when used for 5 or more years, appears to be associated with higher sarcoma rates (J. Clin. Oncol. 2002;20:2758-60) as is a history of pelvic irradiation or childhood retinoblastoma.

Unless metastatic disease is present, symptoms are similar for leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas. A rapidly growing mass, a finding associated with an increased risk of uterine sarcoma, was not seen in Parker’s study of 1,332 women undergoing hysterectomy or myomectomy for uterine leiomyoma. Similarly, size does not count; a large uterine mass or increased uterine size did not appear to be associated with a greater risk of sarcoma (Gynecol. Oncol. 2003;89:460-9).

Some contend that failed response with such therapies as gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and uterine artery embolization are associated with increased incidence of leiomyosarcoma, but the data are not convincing (Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1998;76:237-40).

Physical examination and imaging may be helpful in finding enlarged lymph nodes, but imaging methods have not been reliably shown to enable a preoperative diagnosis of uterine leiomyosarcoma (Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1188-98; AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2003;181:1369-74). Further, while some physicians point out that an ill-defined margin may increase leiomyosarcoma risk, this finding is certainly noted as well with benign adenomyomas.