User login

Actinic Keratosis as a Marker of Field Cancerization in Excision Specimens of Cutaneous Malignancies

The concept of field cancerization was first proposed in 1953 by Slaughter et al1 in their study of oral squamous carcinomas. Their findings of multifocal patches of premalignant disease, abnormal tissue surrounding tumors, multiple localized primary tumors, and tumor recurrence following surgical resection was suggestive of a field of dysplastic cells with malignant potential.1 Since then, modern molecular techniques have been used to establish a genetic basis for this model in many different types of cancer, including cutaneous malignancies.2-4 The field begins from a singular stem cell, which undergoes one or more genetic changes that allow for a growth advantage compared to surrounding cells. The stem cell then divides, forming a patch of clonal daughter cells that displace the surrounding normal epithelium. Growth of this patch eventually leads to a dysplastic field of monoclonal cells, which notably does not yet show invasive growth or metastatic behavior. Over time, continued carcinogenic exposure results in additional genetic alterations among different cells in the field, which leads to new subclonal proliferations that share common clonal origin but exhibit unique genetic changes. Eventually, transformative events may occur, resulting in cells with invasive and metastatic properties, thus forming a carcinoma.5

In the case of cutaneous malignancies, UV radiation in the form of UVA and UVB rays is the most common source of carcinogenesis. It is well established that UV radiation has numerous effects on the body, including but not limited to local and systemic immunosuppression, alteration of signal transduction pathways, and the development of mutations in DNA via direct damage by UVB or indirect damage by free radical formation with UVA.6,7 Normally, DNA is protected from UV radiation–induced genetic alteration by the p53 gene, TP53. As such, damage to this gene is highly associated with cancer induction. One study found that more than 90% of squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) and more than 50% of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) contain UV-like mutations in TP53.8 The concept of field cancerization suggests that because the skin surrounding cutaneous malignancies has been exposed to the same chronic UV light as the initial lesion, it is at an increased risk for genetic abnormalities and thus possible malignant transformation.

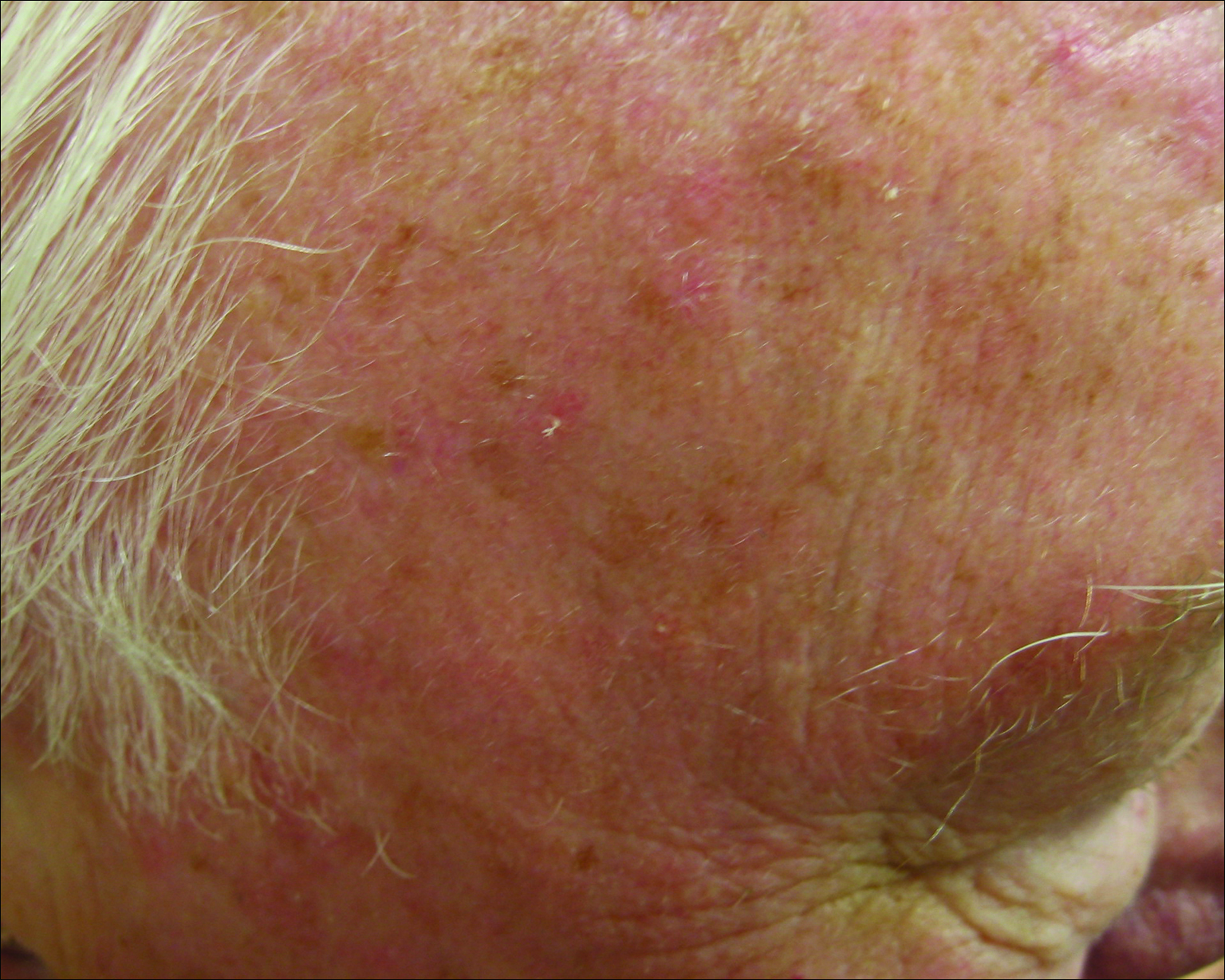

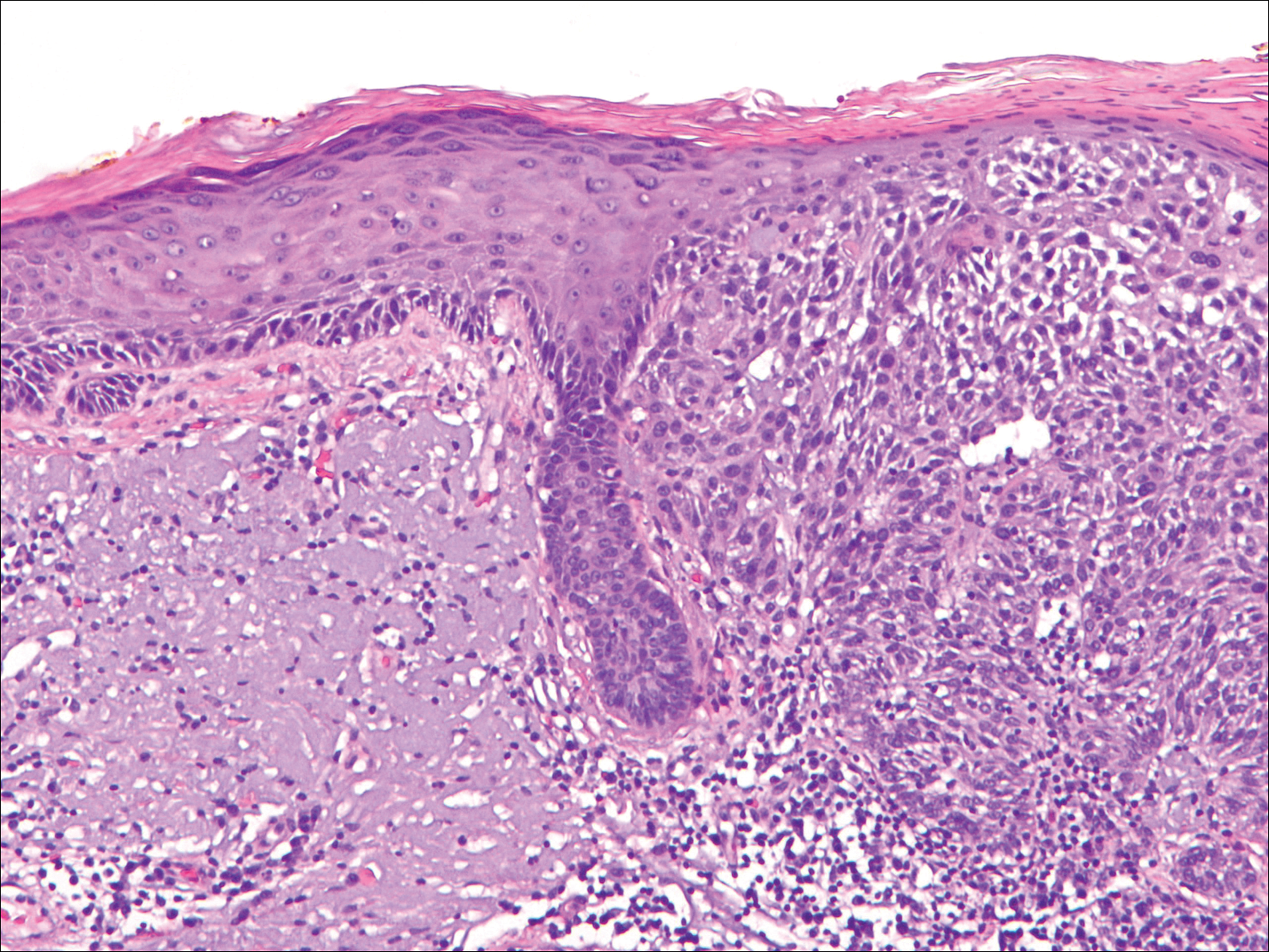

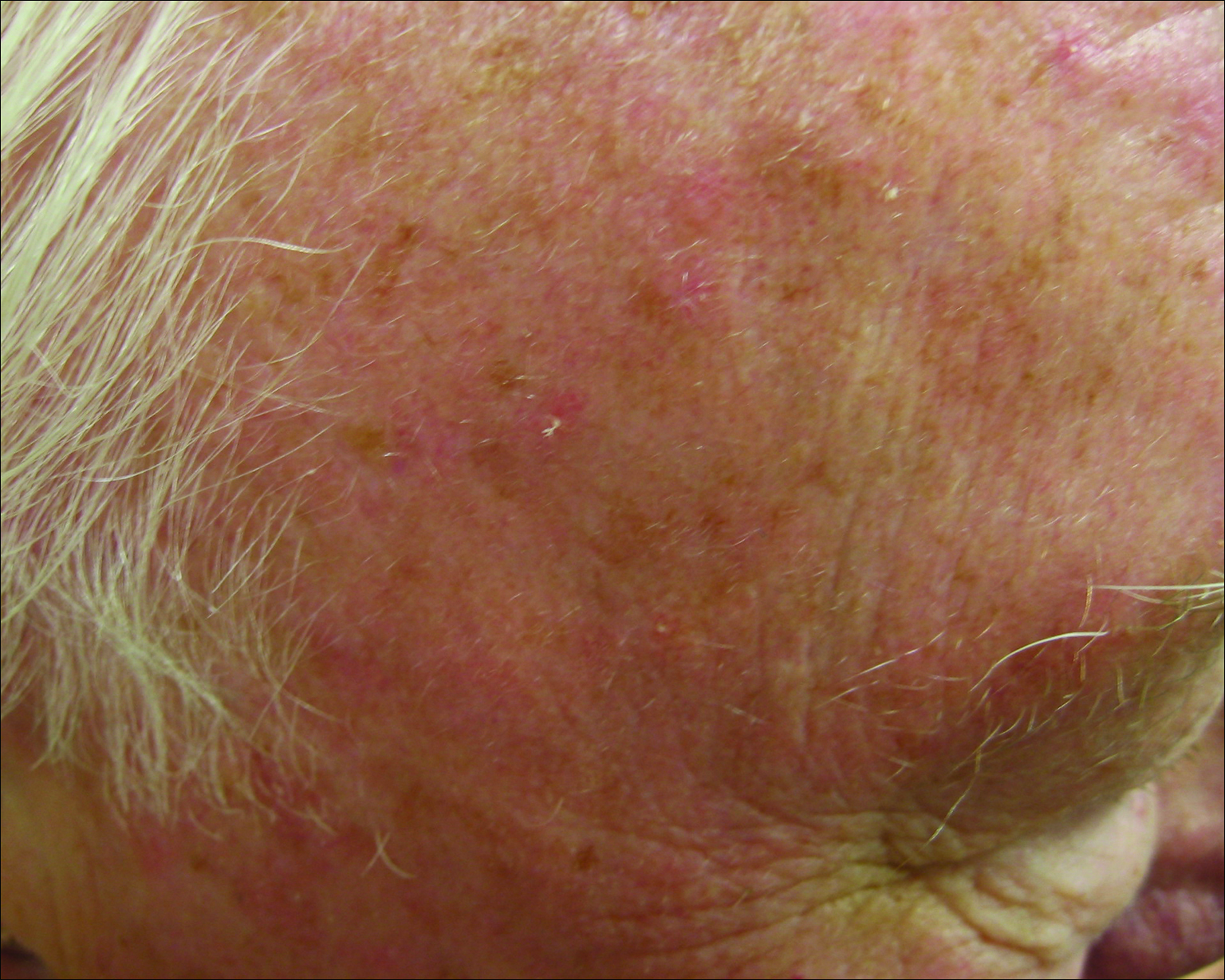

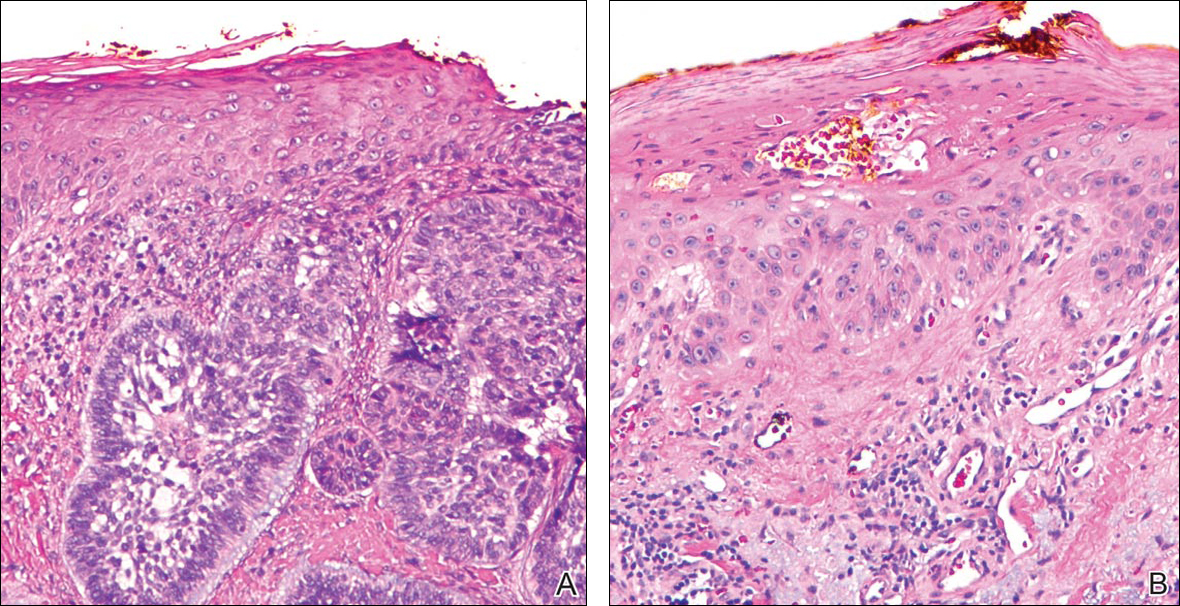

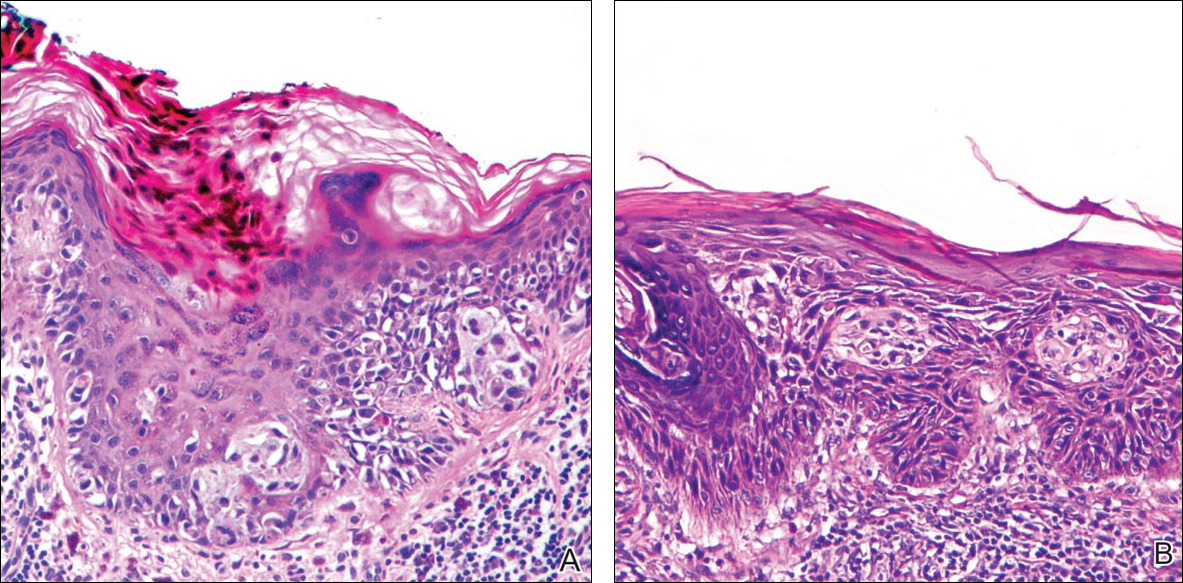

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are common neoplasms of the skin that generally are regarded as precancerous lesions or may be considered to be the earliest stage of SCC in situ.9 Actinic keratoses usually develop as a consequence of chronic exposure to UV radiation and often are clinically apparent as erythematous scaly papules in sun-exposed areas (Figure 1).10 They also are identified histologically as atypical keratinocytes along the basal layer of the epidermis with possible enlargement, hyperchromatic nuclei, lack of maturation, mitotic figures, inflammatory infiltrate, and/or hyperkeratosis.10 Furthermore, the genetic changes associated with AKs are well documented and are strongly associated with changes to p53.11 Given these characteristics, AKs serve as good markers of genetic damage with potential for malignancy. In this study, we used histologically identified AKs to assess the presence of field damage in the tissue immediately surrounding excision specimens of SCCs, BCCs, and malignant melanomas (MMs).

Methods

This study was approved by the Program for the Protection of Human Subjects at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (New York, New York) prior to initiation. All cutaneous specimens submitted to the dermatopathology service for consultation between April 2013 and June 2013 were reviewed for inclusion in this study. Data collection was extended for MMs to include all specimens from January 2013 to June 2013 given the limited number of cases in the original data collection period.

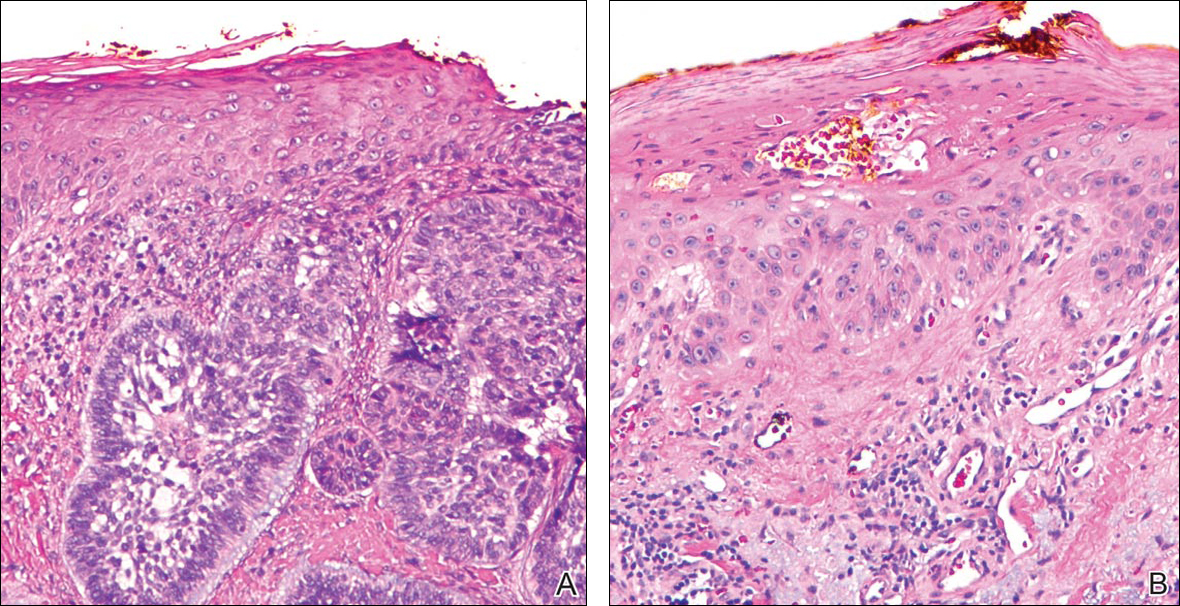

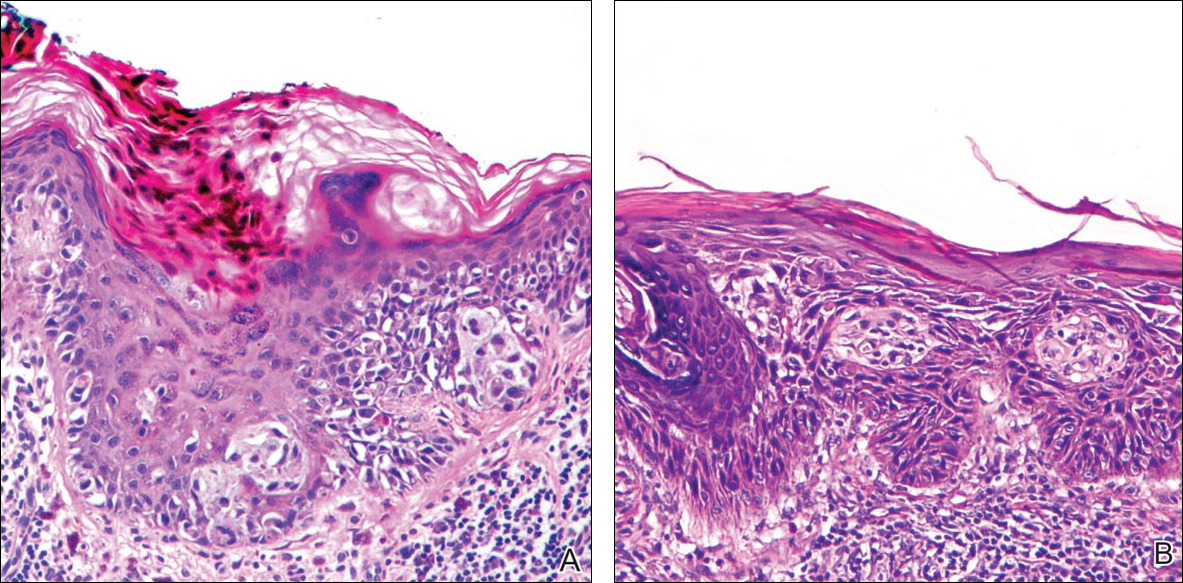

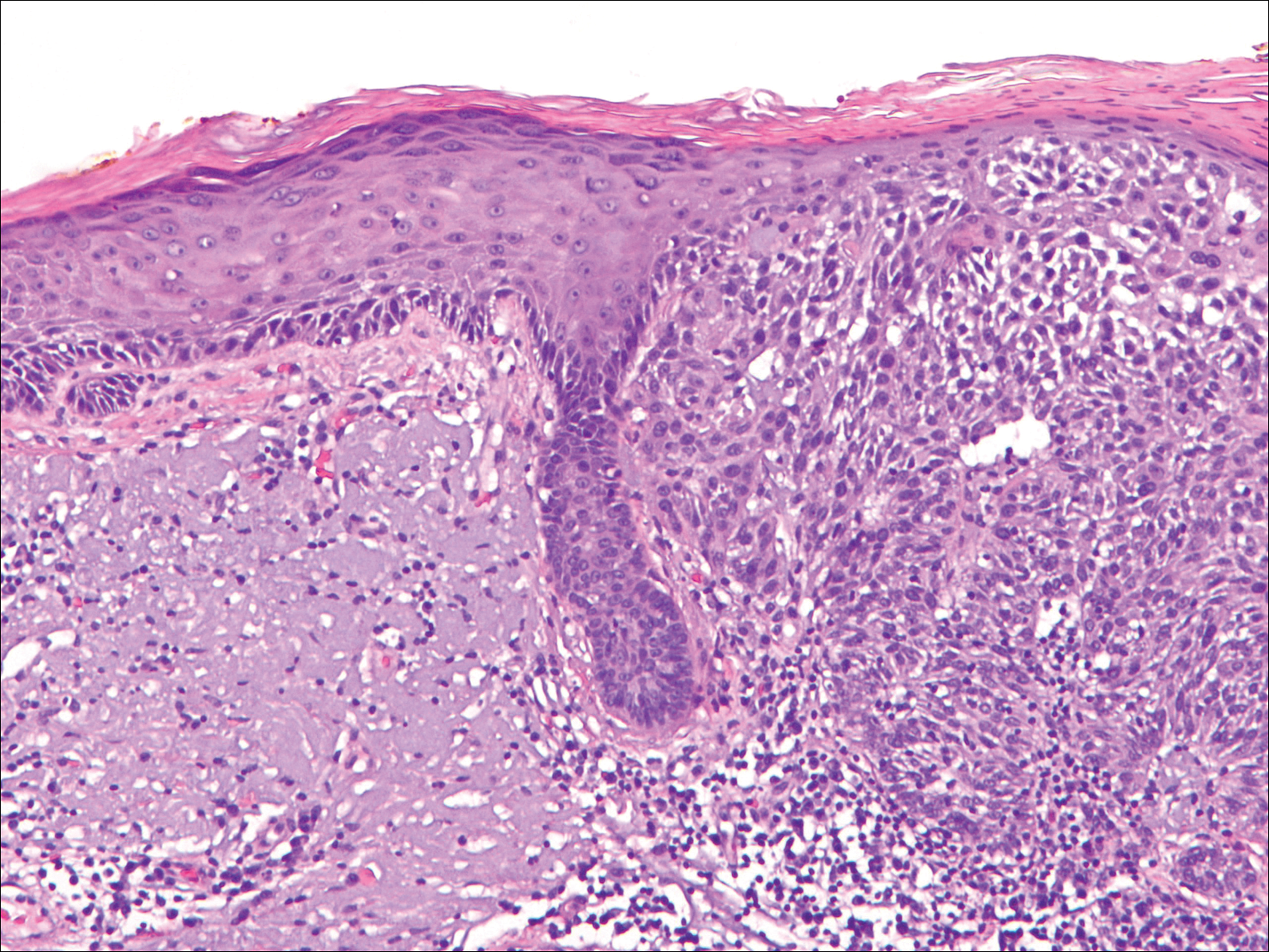

Initial screening for this study was done electronically and assessed for a diagnosis of SCC (Figure 2), BCC (Figure 3), or MM (Figure 4) as determined by a board-certified dermatopathologist (G.G.). The resulting pool of specimens was then screened to include only excision specimens and to exclude curettage specimens and superficial specimens that lacked dermis. In this study, we chose to look at reexcisions rather than initial biopsies so that there was a greater likelihood of having an intact epidermis surrounding a malignancy that could be assessed for the presence of AKs as markers for field cancerization. Specimens were examined in full via serial transverse cross-sections at 3-mm intervals. Additional step sections were obtained at smaller intervals when margins were close or unclear.

Selected cases were reassessed by a board-certified dermatopathologist (G.G.) to confirm the diagnosis and to assess for the presence of at least 1 AK within the specimen sample that was separated from the original malignancy by histologically normal-appearing cells. Samples were also assessed for the presence of an AK within 0.1 mm of the distal lateral margins of the tissue sample. Information regarding patient age, gender, lesion location, lesion type, and specimen size was collected for each sample. In accordance with institutional review board protocol, research data were collected without any protected health information. All analyses and results were deidentified and stored on a password-protected computer database. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software. When applicable, P<.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

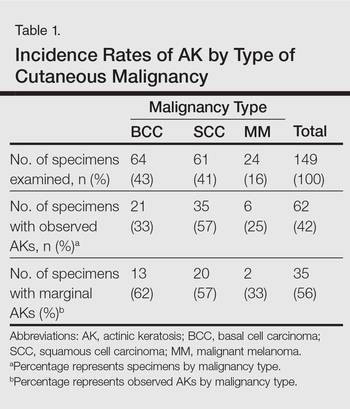

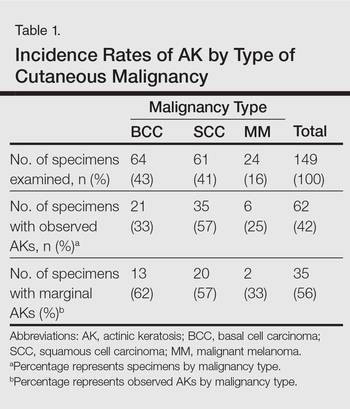

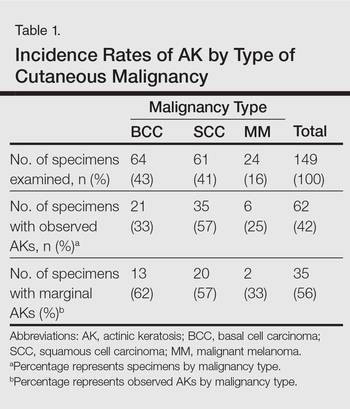

There were 205 cases that passed the initial screening filters, of which 56 were excluded due to the presence of curettage or lack of a sufficient tissue sample. Of the remaining 149 cases, the distribution by malignancy type was tabulated along with the percentage of observed AKs. If an AK was observed, the percentage that had an AK at the lateral margins (marginal AK) was determined (Table 1). A χ2 analysis determined that AKs were observed significantly more often in SCC specimens (57% [35/61]) than BCC (33% [21/64]) or malignant melanoma (25% [6/24]) specimens (P=.0125).

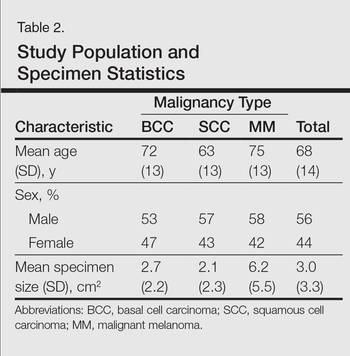

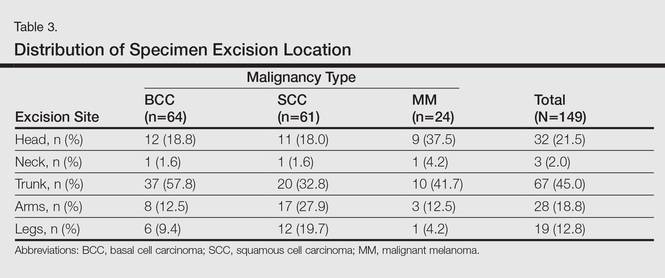

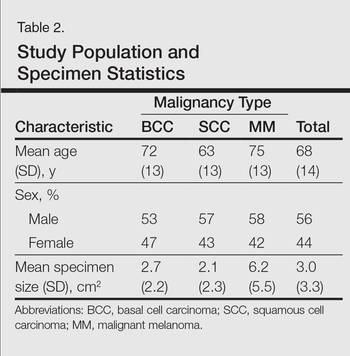

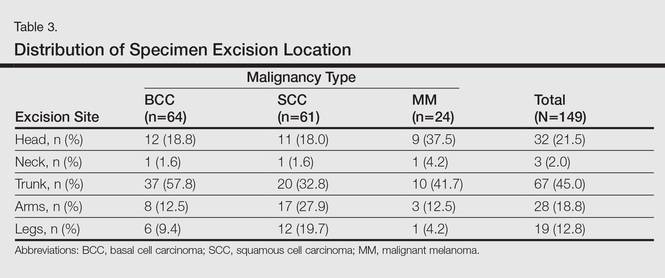

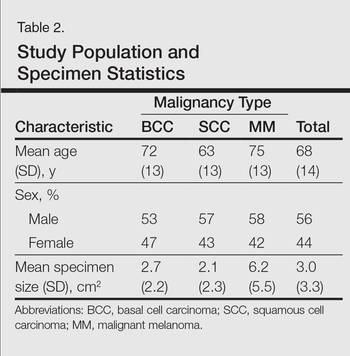

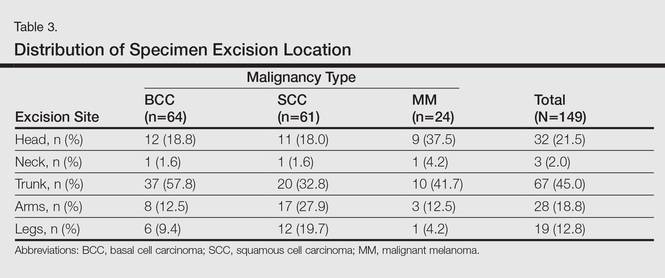

Statistics regarding patient age and gender as well as specimen size were stratified by malignancy type (Table 2). Using a receiver operating characteristic curve and the Youden index, an optimal cutoff of older than 67 years was determined to increase probability of observing an AK (P=.077) with sensitivity of 0.531 and specificity of 0.529. The distribution of specimen excision location for each malignancy type is shown in Table 3.

A multivariate analysis was performed to determine if the variables of patient age, gender, biopsy size, malignancy type (SCC, BCC, or MM), or cancer location (head, neck, trunk, arms, or legs) were independently useful in predicting whether an AK would be observed in the excision specimen. The significance of variables in the logistic regression model was assessed using a backward stepwise regression selection procedure entering variables if P<.15 and excluding variables if P>.25. Significant variables in predicting the occurrence of AK were SCC malignancy type (P=.007; odds ratio [OR], 2.61) and location on the head (P=.044; OR, 2.39) and arms (P=.042; OR, 2.55).

Comment

The χ2 analysis of our data showed that SCC specimens were significantly more likely to have an associated AK than either BCCs or MMs (P=.0125), which is not surprising given that AKs are considered by many to be early-stage SCCs.12 It is important to note, however, that BCCs and MMs both had nonnegligible rates of associated AKs. Although BCC and MM do not arise from the same background of genetic changes as SCC, this finding is noteworthy because it demonstrates definitive field damage with malignant potential in the area surrounding these cutaneous malignancies.

Our data also showed that there was a significantly greater association of AKs in malignancies located on the head (P=.044) and arms (P=.042), possibly because these 2 areas tend to be the most sun exposed and thus are more likely to have sustained field damage as evidenced by the higher percentage of AKs. A study by Jonason et al13 described a similar finding in which sun-exposed skin exhibited significantly more frequent (P=.04) and larger (P=.02) clonal patches of mutated p53 keratinocytes than sun-protected skin.

It is likely that the field damage surrounding the cutaneous lesions in our study is actually greater than what we reported because the AK was present at the margin of the excision specimens the majority of the time (56%), which suggests that there likely may have been more AKs found if a wider area surrounding the malignancy had been studied given that AKs often are at the periphery of the lesion and may be missed by a small excision. Fewer marginal AKs were observed with MM cases, possibly because the excision specimens were more than double the size of SCC or BCC excisions. Furthermore, there likely is to be more damage than what can be appreciated by visual changes alone.

Kanjilal et al14 used polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing to demonstrate numerous p53 mutations in nonmalignant-appearing skin surrounding BCCs and SCCs. Brennan et al15 found p53 mutations in surgical margins of excised SCCs considered to be tumor free by histopathologic analysis in more than half of the specimens studied. Notably, tumor recurrence was significantly more likely in areas where mutations were found and no tumor recurrence was seen in areas free of p53 mutations (P=.02).15 Tabor et al4 similarly found genetically altered fields in histologically clear surgical margins of SCCs but also showed that local tumor recurrence following excision had more molecular markers in common with the nonresected premalignant field than it did with the primary tumor. Thus, these studies provide a genetic basis for field damage that can exist even in histologically benign-appearing cells.

We believe our findings are clinically relevant, as they provide additional evidence for the theory of field cancerization as demonstrated by the nonnegligible rates of AKs and thus field damage with malignant potential in the skin immediately surrounding cutaneous malignancies. The limitations of our study, however, include a small sample size; no consideration of the effects of prior topical, field, or systemic treatments; and lack of a control group. Nevertheless, our findings emphasize the importance of assessing the extent of field damage when determining treatment strategies. Clinicians treating cutaneous malignancies should consider the need for field therapy, especially in sun-exposed regions, to avoid additional primary tumors.16 Further research is needed, however, to identify optimal methods for quantifying field damage clinically and determining the most effective treatment strategies.

- Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. Field cancerization in oral stratified squamous epithelium; clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer. 1953;6:963-968.

- Braakhuis B, Tabor M, Kummer J, et al. A genetic explanation of Slaughter’s concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1727-1730.

- Stern R, Bolshakov S, Nataraj A, et al. p53 Mutation in nonmelanoma skin cancers occurring in psoralen ultraviolet A-treated patients: evidence for heterogeneity and field cancerization. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:522-526.

- Tabor M, Brakenhoff R, van Houten VM, et al. Persistence of genetically altered fields in head and neck cancer patients: biological and clinical implications. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1523-1532.

- Torezan L. Cutaneous field cancerization: clinical, histopathological and therapeutic aspects. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:775-786.

- Ullrich S, Kripke M, Ananthaswamy H. Mechanisms underlying UV-induced immune suppression: implications for sunscreen design. Exp Dermatol. 2002;11:1-4.

- de Gruijl FR. Photocarcinogenesis: UVA vs UVB. Methods Enzymol. 2000;319:359-366.

- Brash DE, Ziegler A, Jonason AS, et al. Sunlight and sunburn in human skin cancer: p53, apoptosis, and tumor promotion. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1996;1:136-142.

- Ackerman AB, Mones JM. Solar (actinic) keratosis is squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:9-22.

- Rossi R, Mori M, Lotti T. Actinic keratosis. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:895-904.

- Ziegler A, Jonason AS, Leffel DJ, et al. Sunburn and p53 in the onset of skin cancer. Nature. 1994;372:773-776.

- Cockerell C. Histopathology of incipient intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (“actinic keratosis”). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:11-17.

- Jonason AS, Kunala S, Price GJ, et al. Frequent clones of p53-mutated keratinocytes in normal human skin. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:14025-14029.

- Kanjilal S, Strom SS, Clayman GL, et al. p53 Mutations in nonmelanoma skin cancer of the head and neck: molecular evidence for field cancerization. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3604-3609.

- Brennan JA, Mao L, Hruban RH, et al. Molecular assessment of histopathological staging in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:429-435.

- Braathen LR, Morton CA, Basset-Seguin N, et al. Photodynamic therapy for skin field cancerization: an international consensus. International Society for Photodynamic Therapy in Dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1063-1066.

The concept of field cancerization was first proposed in 1953 by Slaughter et al1 in their study of oral squamous carcinomas. Their findings of multifocal patches of premalignant disease, abnormal tissue surrounding tumors, multiple localized primary tumors, and tumor recurrence following surgical resection was suggestive of a field of dysplastic cells with malignant potential.1 Since then, modern molecular techniques have been used to establish a genetic basis for this model in many different types of cancer, including cutaneous malignancies.2-4 The field begins from a singular stem cell, which undergoes one or more genetic changes that allow for a growth advantage compared to surrounding cells. The stem cell then divides, forming a patch of clonal daughter cells that displace the surrounding normal epithelium. Growth of this patch eventually leads to a dysplastic field of monoclonal cells, which notably does not yet show invasive growth or metastatic behavior. Over time, continued carcinogenic exposure results in additional genetic alterations among different cells in the field, which leads to new subclonal proliferations that share common clonal origin but exhibit unique genetic changes. Eventually, transformative events may occur, resulting in cells with invasive and metastatic properties, thus forming a carcinoma.5

In the case of cutaneous malignancies, UV radiation in the form of UVA and UVB rays is the most common source of carcinogenesis. It is well established that UV radiation has numerous effects on the body, including but not limited to local and systemic immunosuppression, alteration of signal transduction pathways, and the development of mutations in DNA via direct damage by UVB or indirect damage by free radical formation with UVA.6,7 Normally, DNA is protected from UV radiation–induced genetic alteration by the p53 gene, TP53. As such, damage to this gene is highly associated with cancer induction. One study found that more than 90% of squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) and more than 50% of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) contain UV-like mutations in TP53.8 The concept of field cancerization suggests that because the skin surrounding cutaneous malignancies has been exposed to the same chronic UV light as the initial lesion, it is at an increased risk for genetic abnormalities and thus possible malignant transformation.

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are common neoplasms of the skin that generally are regarded as precancerous lesions or may be considered to be the earliest stage of SCC in situ.9 Actinic keratoses usually develop as a consequence of chronic exposure to UV radiation and often are clinically apparent as erythematous scaly papules in sun-exposed areas (Figure 1).10 They also are identified histologically as atypical keratinocytes along the basal layer of the epidermis with possible enlargement, hyperchromatic nuclei, lack of maturation, mitotic figures, inflammatory infiltrate, and/or hyperkeratosis.10 Furthermore, the genetic changes associated with AKs are well documented and are strongly associated with changes to p53.11 Given these characteristics, AKs serve as good markers of genetic damage with potential for malignancy. In this study, we used histologically identified AKs to assess the presence of field damage in the tissue immediately surrounding excision specimens of SCCs, BCCs, and malignant melanomas (MMs).

Methods

This study was approved by the Program for the Protection of Human Subjects at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (New York, New York) prior to initiation. All cutaneous specimens submitted to the dermatopathology service for consultation between April 2013 and June 2013 were reviewed for inclusion in this study. Data collection was extended for MMs to include all specimens from January 2013 to June 2013 given the limited number of cases in the original data collection period.

Initial screening for this study was done electronically and assessed for a diagnosis of SCC (Figure 2), BCC (Figure 3), or MM (Figure 4) as determined by a board-certified dermatopathologist (G.G.). The resulting pool of specimens was then screened to include only excision specimens and to exclude curettage specimens and superficial specimens that lacked dermis. In this study, we chose to look at reexcisions rather than initial biopsies so that there was a greater likelihood of having an intact epidermis surrounding a malignancy that could be assessed for the presence of AKs as markers for field cancerization. Specimens were examined in full via serial transverse cross-sections at 3-mm intervals. Additional step sections were obtained at smaller intervals when margins were close or unclear.

Selected cases were reassessed by a board-certified dermatopathologist (G.G.) to confirm the diagnosis and to assess for the presence of at least 1 AK within the specimen sample that was separated from the original malignancy by histologically normal-appearing cells. Samples were also assessed for the presence of an AK within 0.1 mm of the distal lateral margins of the tissue sample. Information regarding patient age, gender, lesion location, lesion type, and specimen size was collected for each sample. In accordance with institutional review board protocol, research data were collected without any protected health information. All analyses and results were deidentified and stored on a password-protected computer database. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software. When applicable, P<.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

There were 205 cases that passed the initial screening filters, of which 56 were excluded due to the presence of curettage or lack of a sufficient tissue sample. Of the remaining 149 cases, the distribution by malignancy type was tabulated along with the percentage of observed AKs. If an AK was observed, the percentage that had an AK at the lateral margins (marginal AK) was determined (Table 1). A χ2 analysis determined that AKs were observed significantly more often in SCC specimens (57% [35/61]) than BCC (33% [21/64]) or malignant melanoma (25% [6/24]) specimens (P=.0125).

Statistics regarding patient age and gender as well as specimen size were stratified by malignancy type (Table 2). Using a receiver operating characteristic curve and the Youden index, an optimal cutoff of older than 67 years was determined to increase probability of observing an AK (P=.077) with sensitivity of 0.531 and specificity of 0.529. The distribution of specimen excision location for each malignancy type is shown in Table 3.

A multivariate analysis was performed to determine if the variables of patient age, gender, biopsy size, malignancy type (SCC, BCC, or MM), or cancer location (head, neck, trunk, arms, or legs) were independently useful in predicting whether an AK would be observed in the excision specimen. The significance of variables in the logistic regression model was assessed using a backward stepwise regression selection procedure entering variables if P<.15 and excluding variables if P>.25. Significant variables in predicting the occurrence of AK were SCC malignancy type (P=.007; odds ratio [OR], 2.61) and location on the head (P=.044; OR, 2.39) and arms (P=.042; OR, 2.55).

Comment

The χ2 analysis of our data showed that SCC specimens were significantly more likely to have an associated AK than either BCCs or MMs (P=.0125), which is not surprising given that AKs are considered by many to be early-stage SCCs.12 It is important to note, however, that BCCs and MMs both had nonnegligible rates of associated AKs. Although BCC and MM do not arise from the same background of genetic changes as SCC, this finding is noteworthy because it demonstrates definitive field damage with malignant potential in the area surrounding these cutaneous malignancies.

Our data also showed that there was a significantly greater association of AKs in malignancies located on the head (P=.044) and arms (P=.042), possibly because these 2 areas tend to be the most sun exposed and thus are more likely to have sustained field damage as evidenced by the higher percentage of AKs. A study by Jonason et al13 described a similar finding in which sun-exposed skin exhibited significantly more frequent (P=.04) and larger (P=.02) clonal patches of mutated p53 keratinocytes than sun-protected skin.

It is likely that the field damage surrounding the cutaneous lesions in our study is actually greater than what we reported because the AK was present at the margin of the excision specimens the majority of the time (56%), which suggests that there likely may have been more AKs found if a wider area surrounding the malignancy had been studied given that AKs often are at the periphery of the lesion and may be missed by a small excision. Fewer marginal AKs were observed with MM cases, possibly because the excision specimens were more than double the size of SCC or BCC excisions. Furthermore, there likely is to be more damage than what can be appreciated by visual changes alone.

Kanjilal et al14 used polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing to demonstrate numerous p53 mutations in nonmalignant-appearing skin surrounding BCCs and SCCs. Brennan et al15 found p53 mutations in surgical margins of excised SCCs considered to be tumor free by histopathologic analysis in more than half of the specimens studied. Notably, tumor recurrence was significantly more likely in areas where mutations were found and no tumor recurrence was seen in areas free of p53 mutations (P=.02).15 Tabor et al4 similarly found genetically altered fields in histologically clear surgical margins of SCCs but also showed that local tumor recurrence following excision had more molecular markers in common with the nonresected premalignant field than it did with the primary tumor. Thus, these studies provide a genetic basis for field damage that can exist even in histologically benign-appearing cells.

We believe our findings are clinically relevant, as they provide additional evidence for the theory of field cancerization as demonstrated by the nonnegligible rates of AKs and thus field damage with malignant potential in the skin immediately surrounding cutaneous malignancies. The limitations of our study, however, include a small sample size; no consideration of the effects of prior topical, field, or systemic treatments; and lack of a control group. Nevertheless, our findings emphasize the importance of assessing the extent of field damage when determining treatment strategies. Clinicians treating cutaneous malignancies should consider the need for field therapy, especially in sun-exposed regions, to avoid additional primary tumors.16 Further research is needed, however, to identify optimal methods for quantifying field damage clinically and determining the most effective treatment strategies.

The concept of field cancerization was first proposed in 1953 by Slaughter et al1 in their study of oral squamous carcinomas. Their findings of multifocal patches of premalignant disease, abnormal tissue surrounding tumors, multiple localized primary tumors, and tumor recurrence following surgical resection was suggestive of a field of dysplastic cells with malignant potential.1 Since then, modern molecular techniques have been used to establish a genetic basis for this model in many different types of cancer, including cutaneous malignancies.2-4 The field begins from a singular stem cell, which undergoes one or more genetic changes that allow for a growth advantage compared to surrounding cells. The stem cell then divides, forming a patch of clonal daughter cells that displace the surrounding normal epithelium. Growth of this patch eventually leads to a dysplastic field of monoclonal cells, which notably does not yet show invasive growth or metastatic behavior. Over time, continued carcinogenic exposure results in additional genetic alterations among different cells in the field, which leads to new subclonal proliferations that share common clonal origin but exhibit unique genetic changes. Eventually, transformative events may occur, resulting in cells with invasive and metastatic properties, thus forming a carcinoma.5

In the case of cutaneous malignancies, UV radiation in the form of UVA and UVB rays is the most common source of carcinogenesis. It is well established that UV radiation has numerous effects on the body, including but not limited to local and systemic immunosuppression, alteration of signal transduction pathways, and the development of mutations in DNA via direct damage by UVB or indirect damage by free radical formation with UVA.6,7 Normally, DNA is protected from UV radiation–induced genetic alteration by the p53 gene, TP53. As such, damage to this gene is highly associated with cancer induction. One study found that more than 90% of squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) and more than 50% of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) contain UV-like mutations in TP53.8 The concept of field cancerization suggests that because the skin surrounding cutaneous malignancies has been exposed to the same chronic UV light as the initial lesion, it is at an increased risk for genetic abnormalities and thus possible malignant transformation.

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are common neoplasms of the skin that generally are regarded as precancerous lesions or may be considered to be the earliest stage of SCC in situ.9 Actinic keratoses usually develop as a consequence of chronic exposure to UV radiation and often are clinically apparent as erythematous scaly papules in sun-exposed areas (Figure 1).10 They also are identified histologically as atypical keratinocytes along the basal layer of the epidermis with possible enlargement, hyperchromatic nuclei, lack of maturation, mitotic figures, inflammatory infiltrate, and/or hyperkeratosis.10 Furthermore, the genetic changes associated with AKs are well documented and are strongly associated with changes to p53.11 Given these characteristics, AKs serve as good markers of genetic damage with potential for malignancy. In this study, we used histologically identified AKs to assess the presence of field damage in the tissue immediately surrounding excision specimens of SCCs, BCCs, and malignant melanomas (MMs).

Methods

This study was approved by the Program for the Protection of Human Subjects at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (New York, New York) prior to initiation. All cutaneous specimens submitted to the dermatopathology service for consultation between April 2013 and June 2013 were reviewed for inclusion in this study. Data collection was extended for MMs to include all specimens from January 2013 to June 2013 given the limited number of cases in the original data collection period.

Initial screening for this study was done electronically and assessed for a diagnosis of SCC (Figure 2), BCC (Figure 3), or MM (Figure 4) as determined by a board-certified dermatopathologist (G.G.). The resulting pool of specimens was then screened to include only excision specimens and to exclude curettage specimens and superficial specimens that lacked dermis. In this study, we chose to look at reexcisions rather than initial biopsies so that there was a greater likelihood of having an intact epidermis surrounding a malignancy that could be assessed for the presence of AKs as markers for field cancerization. Specimens were examined in full via serial transverse cross-sections at 3-mm intervals. Additional step sections were obtained at smaller intervals when margins were close or unclear.

Selected cases were reassessed by a board-certified dermatopathologist (G.G.) to confirm the diagnosis and to assess for the presence of at least 1 AK within the specimen sample that was separated from the original malignancy by histologically normal-appearing cells. Samples were also assessed for the presence of an AK within 0.1 mm of the distal lateral margins of the tissue sample. Information regarding patient age, gender, lesion location, lesion type, and specimen size was collected for each sample. In accordance with institutional review board protocol, research data were collected without any protected health information. All analyses and results were deidentified and stored on a password-protected computer database. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software. When applicable, P<.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

There were 205 cases that passed the initial screening filters, of which 56 were excluded due to the presence of curettage or lack of a sufficient tissue sample. Of the remaining 149 cases, the distribution by malignancy type was tabulated along with the percentage of observed AKs. If an AK was observed, the percentage that had an AK at the lateral margins (marginal AK) was determined (Table 1). A χ2 analysis determined that AKs were observed significantly more often in SCC specimens (57% [35/61]) than BCC (33% [21/64]) or malignant melanoma (25% [6/24]) specimens (P=.0125).

Statistics regarding patient age and gender as well as specimen size were stratified by malignancy type (Table 2). Using a receiver operating characteristic curve and the Youden index, an optimal cutoff of older than 67 years was determined to increase probability of observing an AK (P=.077) with sensitivity of 0.531 and specificity of 0.529. The distribution of specimen excision location for each malignancy type is shown in Table 3.

A multivariate analysis was performed to determine if the variables of patient age, gender, biopsy size, malignancy type (SCC, BCC, or MM), or cancer location (head, neck, trunk, arms, or legs) were independently useful in predicting whether an AK would be observed in the excision specimen. The significance of variables in the logistic regression model was assessed using a backward stepwise regression selection procedure entering variables if P<.15 and excluding variables if P>.25. Significant variables in predicting the occurrence of AK were SCC malignancy type (P=.007; odds ratio [OR], 2.61) and location on the head (P=.044; OR, 2.39) and arms (P=.042; OR, 2.55).

Comment

The χ2 analysis of our data showed that SCC specimens were significantly more likely to have an associated AK than either BCCs or MMs (P=.0125), which is not surprising given that AKs are considered by many to be early-stage SCCs.12 It is important to note, however, that BCCs and MMs both had nonnegligible rates of associated AKs. Although BCC and MM do not arise from the same background of genetic changes as SCC, this finding is noteworthy because it demonstrates definitive field damage with malignant potential in the area surrounding these cutaneous malignancies.

Our data also showed that there was a significantly greater association of AKs in malignancies located on the head (P=.044) and arms (P=.042), possibly because these 2 areas tend to be the most sun exposed and thus are more likely to have sustained field damage as evidenced by the higher percentage of AKs. A study by Jonason et al13 described a similar finding in which sun-exposed skin exhibited significantly more frequent (P=.04) and larger (P=.02) clonal patches of mutated p53 keratinocytes than sun-protected skin.

It is likely that the field damage surrounding the cutaneous lesions in our study is actually greater than what we reported because the AK was present at the margin of the excision specimens the majority of the time (56%), which suggests that there likely may have been more AKs found if a wider area surrounding the malignancy had been studied given that AKs often are at the periphery of the lesion and may be missed by a small excision. Fewer marginal AKs were observed with MM cases, possibly because the excision specimens were more than double the size of SCC or BCC excisions. Furthermore, there likely is to be more damage than what can be appreciated by visual changes alone.

Kanjilal et al14 used polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing to demonstrate numerous p53 mutations in nonmalignant-appearing skin surrounding BCCs and SCCs. Brennan et al15 found p53 mutations in surgical margins of excised SCCs considered to be tumor free by histopathologic analysis in more than half of the specimens studied. Notably, tumor recurrence was significantly more likely in areas where mutations were found and no tumor recurrence was seen in areas free of p53 mutations (P=.02).15 Tabor et al4 similarly found genetically altered fields in histologically clear surgical margins of SCCs but also showed that local tumor recurrence following excision had more molecular markers in common with the nonresected premalignant field than it did with the primary tumor. Thus, these studies provide a genetic basis for field damage that can exist even in histologically benign-appearing cells.

We believe our findings are clinically relevant, as they provide additional evidence for the theory of field cancerization as demonstrated by the nonnegligible rates of AKs and thus field damage with malignant potential in the skin immediately surrounding cutaneous malignancies. The limitations of our study, however, include a small sample size; no consideration of the effects of prior topical, field, or systemic treatments; and lack of a control group. Nevertheless, our findings emphasize the importance of assessing the extent of field damage when determining treatment strategies. Clinicians treating cutaneous malignancies should consider the need for field therapy, especially in sun-exposed regions, to avoid additional primary tumors.16 Further research is needed, however, to identify optimal methods for quantifying field damage clinically and determining the most effective treatment strategies.

- Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. Field cancerization in oral stratified squamous epithelium; clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer. 1953;6:963-968.

- Braakhuis B, Tabor M, Kummer J, et al. A genetic explanation of Slaughter’s concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1727-1730.

- Stern R, Bolshakov S, Nataraj A, et al. p53 Mutation in nonmelanoma skin cancers occurring in psoralen ultraviolet A-treated patients: evidence for heterogeneity and field cancerization. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:522-526.

- Tabor M, Brakenhoff R, van Houten VM, et al. Persistence of genetically altered fields in head and neck cancer patients: biological and clinical implications. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1523-1532.

- Torezan L. Cutaneous field cancerization: clinical, histopathological and therapeutic aspects. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:775-786.

- Ullrich S, Kripke M, Ananthaswamy H. Mechanisms underlying UV-induced immune suppression: implications for sunscreen design. Exp Dermatol. 2002;11:1-4.

- de Gruijl FR. Photocarcinogenesis: UVA vs UVB. Methods Enzymol. 2000;319:359-366.

- Brash DE, Ziegler A, Jonason AS, et al. Sunlight and sunburn in human skin cancer: p53, apoptosis, and tumor promotion. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1996;1:136-142.

- Ackerman AB, Mones JM. Solar (actinic) keratosis is squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:9-22.

- Rossi R, Mori M, Lotti T. Actinic keratosis. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:895-904.

- Ziegler A, Jonason AS, Leffel DJ, et al. Sunburn and p53 in the onset of skin cancer. Nature. 1994;372:773-776.

- Cockerell C. Histopathology of incipient intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (“actinic keratosis”). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:11-17.

- Jonason AS, Kunala S, Price GJ, et al. Frequent clones of p53-mutated keratinocytes in normal human skin. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:14025-14029.

- Kanjilal S, Strom SS, Clayman GL, et al. p53 Mutations in nonmelanoma skin cancer of the head and neck: molecular evidence for field cancerization. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3604-3609.

- Brennan JA, Mao L, Hruban RH, et al. Molecular assessment of histopathological staging in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:429-435.

- Braathen LR, Morton CA, Basset-Seguin N, et al. Photodynamic therapy for skin field cancerization: an international consensus. International Society for Photodynamic Therapy in Dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1063-1066.

- Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. Field cancerization in oral stratified squamous epithelium; clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer. 1953;6:963-968.

- Braakhuis B, Tabor M, Kummer J, et al. A genetic explanation of Slaughter’s concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1727-1730.

- Stern R, Bolshakov S, Nataraj A, et al. p53 Mutation in nonmelanoma skin cancers occurring in psoralen ultraviolet A-treated patients: evidence for heterogeneity and field cancerization. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:522-526.

- Tabor M, Brakenhoff R, van Houten VM, et al. Persistence of genetically altered fields in head and neck cancer patients: biological and clinical implications. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1523-1532.

- Torezan L. Cutaneous field cancerization: clinical, histopathological and therapeutic aspects. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:775-786.

- Ullrich S, Kripke M, Ananthaswamy H. Mechanisms underlying UV-induced immune suppression: implications for sunscreen design. Exp Dermatol. 2002;11:1-4.

- de Gruijl FR. Photocarcinogenesis: UVA vs UVB. Methods Enzymol. 2000;319:359-366.

- Brash DE, Ziegler A, Jonason AS, et al. Sunlight and sunburn in human skin cancer: p53, apoptosis, and tumor promotion. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1996;1:136-142.

- Ackerman AB, Mones JM. Solar (actinic) keratosis is squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:9-22.

- Rossi R, Mori M, Lotti T. Actinic keratosis. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:895-904.

- Ziegler A, Jonason AS, Leffel DJ, et al. Sunburn and p53 in the onset of skin cancer. Nature. 1994;372:773-776.

- Cockerell C. Histopathology of incipient intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (“actinic keratosis”). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:11-17.

- Jonason AS, Kunala S, Price GJ, et al. Frequent clones of p53-mutated keratinocytes in normal human skin. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:14025-14029.

- Kanjilal S, Strom SS, Clayman GL, et al. p53 Mutations in nonmelanoma skin cancer of the head and neck: molecular evidence for field cancerization. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3604-3609.

- Brennan JA, Mao L, Hruban RH, et al. Molecular assessment of histopathological staging in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:429-435.

- Braathen LR, Morton CA, Basset-Seguin N, et al. Photodynamic therapy for skin field cancerization: an international consensus. International Society for Photodynamic Therapy in Dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1063-1066.

Practice Points

- Clinically apparent and subclinical actinic keratoses usually are present in patients, a concept known as field cancerization, and it is important to treat both types of lesions.

- Actinic keratoses are present in the field of cutaneous malignancies, including basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma.