User login

Are single-incision mini-slings the new gold standard for stress urinary incontinence?

Abdel-Fattah M, Cooper D, Davidson T, et al. Single-incision mini-slings for stress urinary incontinence in women. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1230-1243.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

A joint society position statement by the American Urogynecologic Society and the Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine and Urogenital Reconstruction published in December 2021 declared synthetic midurethral slings, first cleared for use in the United States in the early 1990s, the most extensively studied anti-incontinence operation and the standard of care for the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence.1 Full-length retropubic and transobturator (out-in and in-out) slings have been extensively evaluated for safety and efficacy in well-conducted randomized trials.2 Single-incision mini-slings (SIMS) were first cleared for use in 2006, but they lack the long-term safety and comparative effectiveness data of full-length standard midurethral slings (SMUS).3 Furthermore, several iterations of the mini-slings have come to market but have been withdrawn or modified to allow for adjustability.

The SIMS trial by Abdel-Fattah and colleagues, published recently in the New England Journal of Medicine, is one of the few randomized trials with long-term (3 year) subjective and objective outcome data based on comparison of adjustable single-incision mini-slings versus standard full-length midurethral slings.

Details of the study

The SIMS trial is a noninferiority multicenter randomized controlled trial funded by the National Institute for Health Research at 21 hospitals in the United Kingdom that compared adjustable mini-sling procedures performed under local anesthesia with full-length retrotropubic and transobturator sling procedures performed under general anesthesia. Patients and surgeons were not masked to study group assignment because of the differences in anesthesia, and patients with greater than stage 2 prolapse were excluded from the trial.

The primary outcome was Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I) based on a 7-point Likert scale, with success defined as very much improved or much improved at 15 months and failure defined as all other responses (improved, same, worse, much worse, and very much worse). A noninferiority margin was set at 10 percentage points at 15 months.

Secondary outcomes and adverse events at 36 months included postoperative pain, return to normal activities, objective success based on a 24-hour pad test weight of less than 8 g, and tape exposure, organ injury, new or worsening urinary urgency, dyspareunia, and need for prolonged catheterization.

A total of 596 women were enrolled in the study, 298 in the mini-sling arm and 298 in the standard midurethral sling arm. Baseline characteristics were similar in both groups with most sling procedures being performed by general consultant gynecologists (>60%) versus subspecialist urogynecologists.

Results. Success at 15 months, based on the PGI-I responses of very much better or much better, was noted in 79.1% of patients in the mini-sling group (212/268) versus 75.6% in the full-length sling group (189/250). The authors deemed mini-slings noninferior to standard full-length slings (adjusted risk difference, 4.6 percentage points; 95% confidence interval [CI], -2.7 to 11.8; P<.001 for noninferiority). Success rates declined but remained similar in both groups at 36 months: 72% in the mini-sling group (177/246) and 66.8% (157/235) in the full-length sling group.

More than 70% of mini-incision slings were Altis (Coloplast) and 22% were Ajust (CR Bard; since withdrawn from the market). The majority of standard midurethral full-length slings were transobturator slings (52.9%) versus retropubic slings (35.6%).

While blood loss, organ injury, and 36-month objective 24-hour pad test did not differ between groups, there were significant differences in other secondary outcomes. Dyspareunia and coital incontinence were more common with mini-slings at 15 and 36 months, reported in 11.7% of the mini-sling group and 4.8% of the full-length group (P<.01). Groin or thigh pain did not differ significantly between groups at 36 months (14.1% in mini-sling and 14.9% in full-length sling group, P = .61). Mesh exposure was noted in 3.3% of those with mini-slings and 1.9% of those with standard midurethral slings. The need for surgical intervention to treat recurrent stress incontinence or mesh removal for voiding dysfunction, pain, or mesh exposure also did not differ between groups (8.7% of the mini-sling group and 4.6% of the midurethral sling group; P = .12).

Study strengths and limitations

The strengths of this pragmatic randomized trial are in the use of clinically important and validated patient-reported subjective and objective outcomes in an adequately powered multisite trial of long duration (36 months). This study is important in demonstrating noninferiority of the mini-sling procedure compared with full-length slings, especially given this trial’s timing when there was a pause or suspension of sling mesh use in the United Kingdom beginning in 2018.

Study limitations include the loss to follow-up with diminished response rate of 87.1% at 15 months and 81.4% at 36 months and the inability to adequately assess for the uncommon outcomes, such as mesh-related complications and groin pain.

Further analysis needed

The high rate of dyspareunia (11.7%) with mini-slings deserves further analysis and consideration of whether or not to implant them in patients who are sexually active. Groin or thigh pain did not differ at 36 months but reported pain coincided with the higher percentage of transobturator slings placed over retropubic slings. Prior randomized trials of transobturator versus retropubic midurethral slings have demonstrated this same phenomenon of increased groin pain with the transobturator approach.2 Furthermore, this study by Abdel-Fattah and colleagues excluded patients with advanced anterior or apical prolapse, but one trial is currently underway in the United States.4

In conclusion, this trial suggests some advantages of single-incision mini-slings—ability to perform the procedure under local anesthesia, less synthetic mesh implantation with theoretically decreased risk of bladder perforation or bowel injury, and potential for easier removal compared with full-length slings. Disadvantages include dyspareunia and mesh exposure, which could be significant trade-offs for patients. ●

In the IDEAL framework for evaluating new surgical innovations, the recommended process begins with an idea, followed by development by a few surgeons in a few patients, then exploration in a feasibility randomized controlled trial, an assessment in larger trials by many surgeons, and long-term follow-up.5 The SIMS trial falls under the assessment tab of the IDEAL framework and represents a much-needed study prior to widespread adoption of single-incision mini-slings. The higher dyspareunia rate in women undergoing single-incision mini-slings deserves further evaluation.

CHERYL B. IGLESIA, MD

- Joint position statement on midurethral slings for stress urinary incontinence. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27:707-710. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000001096.

- Richter HE, Albo ME, Zyczynski HM, et al; Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network. Retropubic versus transobturator midurethral slings for stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2066-2076.

- Nambiar A, Cody JD, Jeffery ST. Single-incision sling operations for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;6:CD008709.

- National Institutes of Health. Retropubic vs single-incision mid-urethral sling for stress urinary incontinence. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03520114. Accessed July16, 2022. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT0352011 4?cond=altis+sling&draw=2&rank=6

- McCulloch P, Altman DG, Campbell WB, et al. No surgical innovation without evaluation: the IDEAL recommendations. Lancet. 2009;374:1105-1111.

Abdel-Fattah M, Cooper D, Davidson T, et al. Single-incision mini-slings for stress urinary incontinence in women. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1230-1243.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

A joint society position statement by the American Urogynecologic Society and the Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine and Urogenital Reconstruction published in December 2021 declared synthetic midurethral slings, first cleared for use in the United States in the early 1990s, the most extensively studied anti-incontinence operation and the standard of care for the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence.1 Full-length retropubic and transobturator (out-in and in-out) slings have been extensively evaluated for safety and efficacy in well-conducted randomized trials.2 Single-incision mini-slings (SIMS) were first cleared for use in 2006, but they lack the long-term safety and comparative effectiveness data of full-length standard midurethral slings (SMUS).3 Furthermore, several iterations of the mini-slings have come to market but have been withdrawn or modified to allow for adjustability.

The SIMS trial by Abdel-Fattah and colleagues, published recently in the New England Journal of Medicine, is one of the few randomized trials with long-term (3 year) subjective and objective outcome data based on comparison of adjustable single-incision mini-slings versus standard full-length midurethral slings.

Details of the study

The SIMS trial is a noninferiority multicenter randomized controlled trial funded by the National Institute for Health Research at 21 hospitals in the United Kingdom that compared adjustable mini-sling procedures performed under local anesthesia with full-length retrotropubic and transobturator sling procedures performed under general anesthesia. Patients and surgeons were not masked to study group assignment because of the differences in anesthesia, and patients with greater than stage 2 prolapse were excluded from the trial.

The primary outcome was Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I) based on a 7-point Likert scale, with success defined as very much improved or much improved at 15 months and failure defined as all other responses (improved, same, worse, much worse, and very much worse). A noninferiority margin was set at 10 percentage points at 15 months.

Secondary outcomes and adverse events at 36 months included postoperative pain, return to normal activities, objective success based on a 24-hour pad test weight of less than 8 g, and tape exposure, organ injury, new or worsening urinary urgency, dyspareunia, and need for prolonged catheterization.

A total of 596 women were enrolled in the study, 298 in the mini-sling arm and 298 in the standard midurethral sling arm. Baseline characteristics were similar in both groups with most sling procedures being performed by general consultant gynecologists (>60%) versus subspecialist urogynecologists.

Results. Success at 15 months, based on the PGI-I responses of very much better or much better, was noted in 79.1% of patients in the mini-sling group (212/268) versus 75.6% in the full-length sling group (189/250). The authors deemed mini-slings noninferior to standard full-length slings (adjusted risk difference, 4.6 percentage points; 95% confidence interval [CI], -2.7 to 11.8; P<.001 for noninferiority). Success rates declined but remained similar in both groups at 36 months: 72% in the mini-sling group (177/246) and 66.8% (157/235) in the full-length sling group.

More than 70% of mini-incision slings were Altis (Coloplast) and 22% were Ajust (CR Bard; since withdrawn from the market). The majority of standard midurethral full-length slings were transobturator slings (52.9%) versus retropubic slings (35.6%).

While blood loss, organ injury, and 36-month objective 24-hour pad test did not differ between groups, there were significant differences in other secondary outcomes. Dyspareunia and coital incontinence were more common with mini-slings at 15 and 36 months, reported in 11.7% of the mini-sling group and 4.8% of the full-length group (P<.01). Groin or thigh pain did not differ significantly between groups at 36 months (14.1% in mini-sling and 14.9% in full-length sling group, P = .61). Mesh exposure was noted in 3.3% of those with mini-slings and 1.9% of those with standard midurethral slings. The need for surgical intervention to treat recurrent stress incontinence or mesh removal for voiding dysfunction, pain, or mesh exposure also did not differ between groups (8.7% of the mini-sling group and 4.6% of the midurethral sling group; P = .12).

Study strengths and limitations

The strengths of this pragmatic randomized trial are in the use of clinically important and validated patient-reported subjective and objective outcomes in an adequately powered multisite trial of long duration (36 months). This study is important in demonstrating noninferiority of the mini-sling procedure compared with full-length slings, especially given this trial’s timing when there was a pause or suspension of sling mesh use in the United Kingdom beginning in 2018.

Study limitations include the loss to follow-up with diminished response rate of 87.1% at 15 months and 81.4% at 36 months and the inability to adequately assess for the uncommon outcomes, such as mesh-related complications and groin pain.

Further analysis needed

The high rate of dyspareunia (11.7%) with mini-slings deserves further analysis and consideration of whether or not to implant them in patients who are sexually active. Groin or thigh pain did not differ at 36 months but reported pain coincided with the higher percentage of transobturator slings placed over retropubic slings. Prior randomized trials of transobturator versus retropubic midurethral slings have demonstrated this same phenomenon of increased groin pain with the transobturator approach.2 Furthermore, this study by Abdel-Fattah and colleagues excluded patients with advanced anterior or apical prolapse, but one trial is currently underway in the United States.4

In conclusion, this trial suggests some advantages of single-incision mini-slings—ability to perform the procedure under local anesthesia, less synthetic mesh implantation with theoretically decreased risk of bladder perforation or bowel injury, and potential for easier removal compared with full-length slings. Disadvantages include dyspareunia and mesh exposure, which could be significant trade-offs for patients. ●

In the IDEAL framework for evaluating new surgical innovations, the recommended process begins with an idea, followed by development by a few surgeons in a few patients, then exploration in a feasibility randomized controlled trial, an assessment in larger trials by many surgeons, and long-term follow-up.5 The SIMS trial falls under the assessment tab of the IDEAL framework and represents a much-needed study prior to widespread adoption of single-incision mini-slings. The higher dyspareunia rate in women undergoing single-incision mini-slings deserves further evaluation.

CHERYL B. IGLESIA, MD

Abdel-Fattah M, Cooper D, Davidson T, et al. Single-incision mini-slings for stress urinary incontinence in women. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1230-1243.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

A joint society position statement by the American Urogynecologic Society and the Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine and Urogenital Reconstruction published in December 2021 declared synthetic midurethral slings, first cleared for use in the United States in the early 1990s, the most extensively studied anti-incontinence operation and the standard of care for the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence.1 Full-length retropubic and transobturator (out-in and in-out) slings have been extensively evaluated for safety and efficacy in well-conducted randomized trials.2 Single-incision mini-slings (SIMS) were first cleared for use in 2006, but they lack the long-term safety and comparative effectiveness data of full-length standard midurethral slings (SMUS).3 Furthermore, several iterations of the mini-slings have come to market but have been withdrawn or modified to allow for adjustability.

The SIMS trial by Abdel-Fattah and colleagues, published recently in the New England Journal of Medicine, is one of the few randomized trials with long-term (3 year) subjective and objective outcome data based on comparison of adjustable single-incision mini-slings versus standard full-length midurethral slings.

Details of the study

The SIMS trial is a noninferiority multicenter randomized controlled trial funded by the National Institute for Health Research at 21 hospitals in the United Kingdom that compared adjustable mini-sling procedures performed under local anesthesia with full-length retrotropubic and transobturator sling procedures performed under general anesthesia. Patients and surgeons were not masked to study group assignment because of the differences in anesthesia, and patients with greater than stage 2 prolapse were excluded from the trial.

The primary outcome was Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I) based on a 7-point Likert scale, with success defined as very much improved or much improved at 15 months and failure defined as all other responses (improved, same, worse, much worse, and very much worse). A noninferiority margin was set at 10 percentage points at 15 months.

Secondary outcomes and adverse events at 36 months included postoperative pain, return to normal activities, objective success based on a 24-hour pad test weight of less than 8 g, and tape exposure, organ injury, new or worsening urinary urgency, dyspareunia, and need for prolonged catheterization.

A total of 596 women were enrolled in the study, 298 in the mini-sling arm and 298 in the standard midurethral sling arm. Baseline characteristics were similar in both groups with most sling procedures being performed by general consultant gynecologists (>60%) versus subspecialist urogynecologists.

Results. Success at 15 months, based on the PGI-I responses of very much better or much better, was noted in 79.1% of patients in the mini-sling group (212/268) versus 75.6% in the full-length sling group (189/250). The authors deemed mini-slings noninferior to standard full-length slings (adjusted risk difference, 4.6 percentage points; 95% confidence interval [CI], -2.7 to 11.8; P<.001 for noninferiority). Success rates declined but remained similar in both groups at 36 months: 72% in the mini-sling group (177/246) and 66.8% (157/235) in the full-length sling group.

More than 70% of mini-incision slings were Altis (Coloplast) and 22% were Ajust (CR Bard; since withdrawn from the market). The majority of standard midurethral full-length slings were transobturator slings (52.9%) versus retropubic slings (35.6%).

While blood loss, organ injury, and 36-month objective 24-hour pad test did not differ between groups, there were significant differences in other secondary outcomes. Dyspareunia and coital incontinence were more common with mini-slings at 15 and 36 months, reported in 11.7% of the mini-sling group and 4.8% of the full-length group (P<.01). Groin or thigh pain did not differ significantly between groups at 36 months (14.1% in mini-sling and 14.9% in full-length sling group, P = .61). Mesh exposure was noted in 3.3% of those with mini-slings and 1.9% of those with standard midurethral slings. The need for surgical intervention to treat recurrent stress incontinence or mesh removal for voiding dysfunction, pain, or mesh exposure also did not differ between groups (8.7% of the mini-sling group and 4.6% of the midurethral sling group; P = .12).

Study strengths and limitations

The strengths of this pragmatic randomized trial are in the use of clinically important and validated patient-reported subjective and objective outcomes in an adequately powered multisite trial of long duration (36 months). This study is important in demonstrating noninferiority of the mini-sling procedure compared with full-length slings, especially given this trial’s timing when there was a pause or suspension of sling mesh use in the United Kingdom beginning in 2018.

Study limitations include the loss to follow-up with diminished response rate of 87.1% at 15 months and 81.4% at 36 months and the inability to adequately assess for the uncommon outcomes, such as mesh-related complications and groin pain.

Further analysis needed

The high rate of dyspareunia (11.7%) with mini-slings deserves further analysis and consideration of whether or not to implant them in patients who are sexually active. Groin or thigh pain did not differ at 36 months but reported pain coincided with the higher percentage of transobturator slings placed over retropubic slings. Prior randomized trials of transobturator versus retropubic midurethral slings have demonstrated this same phenomenon of increased groin pain with the transobturator approach.2 Furthermore, this study by Abdel-Fattah and colleagues excluded patients with advanced anterior or apical prolapse, but one trial is currently underway in the United States.4

In conclusion, this trial suggests some advantages of single-incision mini-slings—ability to perform the procedure under local anesthesia, less synthetic mesh implantation with theoretically decreased risk of bladder perforation or bowel injury, and potential for easier removal compared with full-length slings. Disadvantages include dyspareunia and mesh exposure, which could be significant trade-offs for patients. ●

In the IDEAL framework for evaluating new surgical innovations, the recommended process begins with an idea, followed by development by a few surgeons in a few patients, then exploration in a feasibility randomized controlled trial, an assessment in larger trials by many surgeons, and long-term follow-up.5 The SIMS trial falls under the assessment tab of the IDEAL framework and represents a much-needed study prior to widespread adoption of single-incision mini-slings. The higher dyspareunia rate in women undergoing single-incision mini-slings deserves further evaluation.

CHERYL B. IGLESIA, MD

- Joint position statement on midurethral slings for stress urinary incontinence. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27:707-710. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000001096.

- Richter HE, Albo ME, Zyczynski HM, et al; Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network. Retropubic versus transobturator midurethral slings for stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2066-2076.

- Nambiar A, Cody JD, Jeffery ST. Single-incision sling operations for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;6:CD008709.

- National Institutes of Health. Retropubic vs single-incision mid-urethral sling for stress urinary incontinence. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03520114. Accessed July16, 2022. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT0352011 4?cond=altis+sling&draw=2&rank=6

- McCulloch P, Altman DG, Campbell WB, et al. No surgical innovation without evaluation: the IDEAL recommendations. Lancet. 2009;374:1105-1111.

- Joint position statement on midurethral slings for stress urinary incontinence. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27:707-710. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000001096.

- Richter HE, Albo ME, Zyczynski HM, et al; Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network. Retropubic versus transobturator midurethral slings for stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2066-2076.

- Nambiar A, Cody JD, Jeffery ST. Single-incision sling operations for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;6:CD008709.

- National Institutes of Health. Retropubic vs single-incision mid-urethral sling for stress urinary incontinence. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03520114. Accessed July16, 2022. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT0352011 4?cond=altis+sling&draw=2&rank=6

- McCulloch P, Altman DG, Campbell WB, et al. No surgical innovation without evaluation: the IDEAL recommendations. Lancet. 2009;374:1105-1111.

Best practices for evaluating pelvic pain in patients with Essure tubal occlusion devices

The evaluation and management of chronic pelvic pain in patients with a history of Essure device (Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc, Whippany, New Jersey) insertion have posed many challenges for both clinicians and patients. The availability of high-quality, evidence-based clinical guidance has been limited. We have reviewed the currently available published data, and here provide an overview of takeaways, as well as share our perspective and approach on evaluating and managing chronic pelvic pain in this unique patient population.

The device

The Essure microinsert is a hysteroscopically placed device that facilitates permanent sterilization by occluding the bilateral proximal fallopian tubes. The microinsert has an inner and outer nitinol coil that attaches the device to the proximal fallopian tube to ensure retention. The inner coil releases polyethylene terephthalate fibers that cause tubal fiber proliferation to occlude the lumen of the fallopian tube and achieve sterilization.

The device was first approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2002. In subsequent years, the device was well received and widely used, with approximately 750,000 women worldwide undergoing Essure placement.1,2 Shortly after approval, many adverse events (AEs), including pelvic pain and abnormal uterine bleeding, were reported, resulting in a public meeting of the FDA Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel in September 2015. A postmarket surveillance study on the device ensued to assess complication rates including unplanned pregnancy, pelvic pain, and surgery for removal. In February 2016, the FDA issued a black box warning and a patient decision checklist.3,4 In December 2018, Bayer stopped selling and distributing Essure in the United States.5 A 4-year follow-up surveillance study on Essure was submitted to the FDA in March 2020.

Adverse outcomes

Common AEs related to the Essure device include heavy uterine bleeding, pelvic pain, and other quality-of-life symptoms such as fatigue and weight gain.6-8 The main safety endpoints for the mandated FDA postmarket 522 surveillance studies were chronic lower abdominal and pelvic pain; abnormal uterine bleeding; hypersensitivity; allergic reaction, as well as autoimmune disorders incorporating inflammatory markers and human leukocyte antigen; and gynecologic surgery for device removal.9 Postmarket surveillence has shown that most AEs are related to placement complications or pelvic pain after Essure insertion. However, there have been several reports of autoimmune diseases categorized as serious AEs, such as new-onset systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and worsening ulcerative colitis, after Essure insertion.5

Evaluation of symptoms

Prevalence of pelvic pain following device placement

We conducted a PubMed and MEDLINE search from January 2000 to May 2020, which identified 43 studies citing AEs related to device placement, including pelvic or abdominal pain, abnormal uterine bleeding, hypersensitivity, and autoimmune disorders. A particularly debilitating and frequently cited AE was new-onset pelvic pain or worsening of preexisting pelvic pain. Perforation of the uterus or fallopian tube, resulting in displacement of the device into the peritoneal cavity, or fragmentation of the microinsert was reported as a serious AE that occurred after device placement. However, due to the complexity of chronic pelvic pain pathogenesis, the effect of the insert on patients with existing chronic pelvic pain remains unknown.

Authors of a large retrospective study found that approximately 2.7% of 1,430 patients developed new-onset or worsening pelvic pain after device placement. New-onset pelvic pain in 1% of patients was thought to be secondary to device placement, without a coexisting pathology or diagnosis.10

In a retrospective study by Clark and colleagues, 22 of 50 women (44%) with pelvic pain after microinsert placement were found to have at least one other cause of pelvic pain. The most common alternative diagnoses were endometriosis, adenomyosis, salpingitis, and adhesive disease. Nine of the 50 patients (18%) were found to have endometriosis upon surgical removal of the microinsert.7

Another case series examined outcomes in 29 patients undergoing laparoscopic device removal due to new-onset pelvic pain. Intraoperative findings included endometriosis in 5 patients (17.2%) and pelvic adhesions in 3 (10.3%).2 Chronic pelvic pain secondary to endometriosis may be exacerbated with Essure insertion due to discontinuation of hormonal birth control after device placement,7 and this diagnosis along with adenomyosis should be strongly considered in patients whose pelvic pain began when hormonal contraception was discontinued after placement of the device.

Continue to: Risk factors...

Risk factors

Authors of a retrospective cohort study found that patients with prior diagnosis of a chronic pain syndrome, low back pain, headaches, or fibromyalgia were 5 to 6 times more likely to report acute and chronic pain after hysteroscopic sterilization with Essure.11 Since chronic pain is often thought to be driven by a hyperalgesic state of the central nervous system, as previously shown in patients with conditions such as vulvodynia, interstitial cystitis, and fibromyalgia,12 a hyperalgesic state can potentially explain why some patients are more susceptible to developing worsening pain.

Van Limburg and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study with prospective follow-up on 284 women who underwent Essure sterilization. Among these patients, 48% reported negative AEs; risk factors included young age at placement, increasing gravidity, and no prior abdominal surgery.13

Onset of pain

The timing and onset of pelvic pain vary widely, suggesting there is no particular time frame for this AE after device placement.2,6,14-18 A case series by Arjona and colleagues analyzed the incidence of chronic pelvic pain in 4,274 patients after Essure sterilization. Seven patients (0.16%) reported chronic pelvic pain that necessitated device removal. In 6 of the women, the pelvic pain began within 1 week of device placement. In 3 of the 6 cases, the surgeon reported the removal procedures as “difficult.” In all 6 cases, the level of pelvic pain increased with time and was not alleviated with standard analgesic medications.6

In another case series of 26 patients, the authors evaluated patients undergoing laparoscopic removal of Essure secondary to pelvic pain and reported that the time range for symptom presentation was immediate to 85 months. Thirteen of 26 patients (50%) reported pain onset within less than 1 month of device placement, 5 of 26 patients (19.2%) reported pain between 1 and 12 months after device placement, and 8 of 26 patients (30.8%) reported pain onset more than 12 months after microinsert placement.2 In this study, 17.2% of operative reports indicated difficulty with device placement. It is unclear whether difficulty with placement was associated with development of subsequent abdominal or pelvic pain; however, the relevance of initial insertion difficulty diminished with longer follow-up.

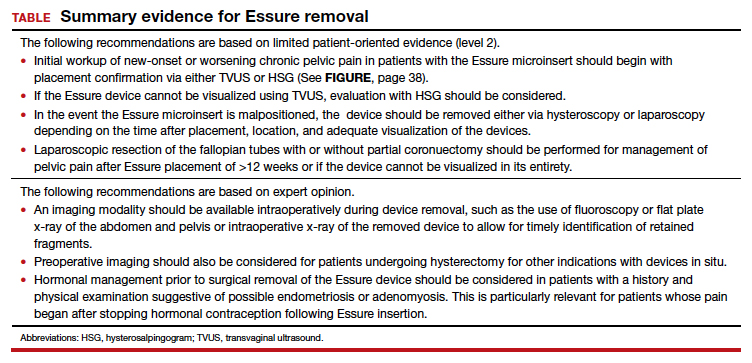

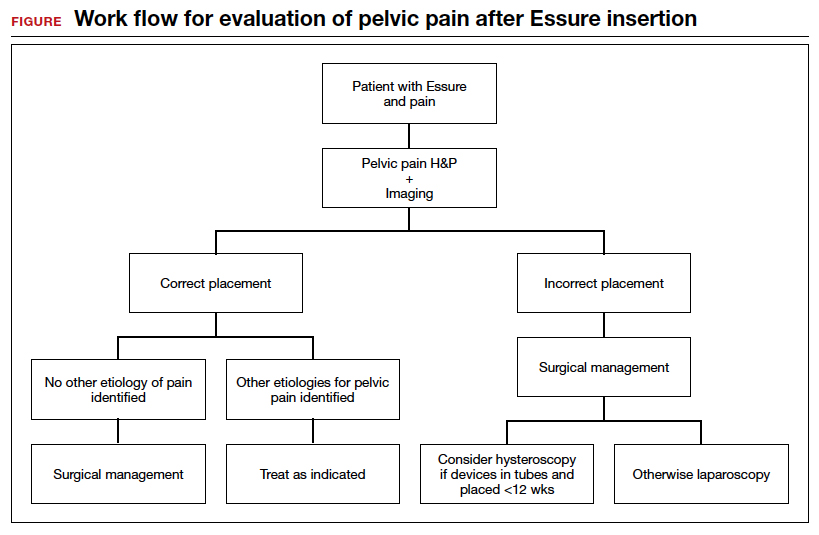

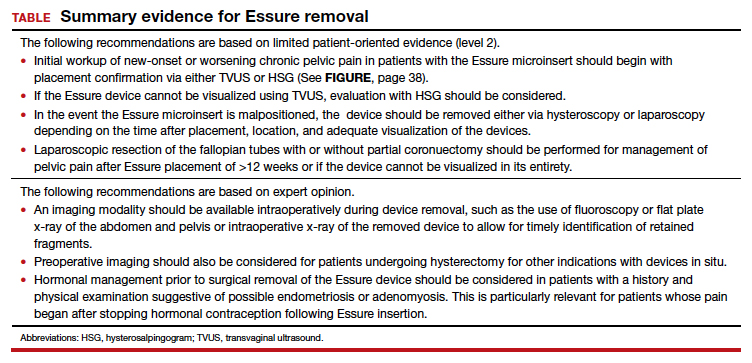

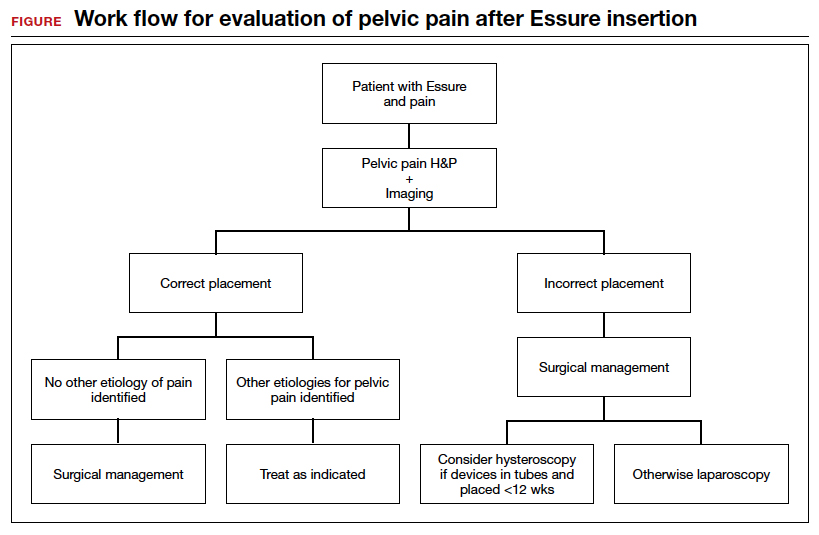

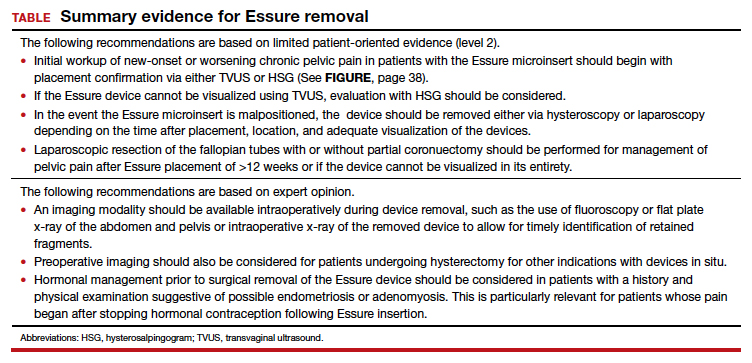

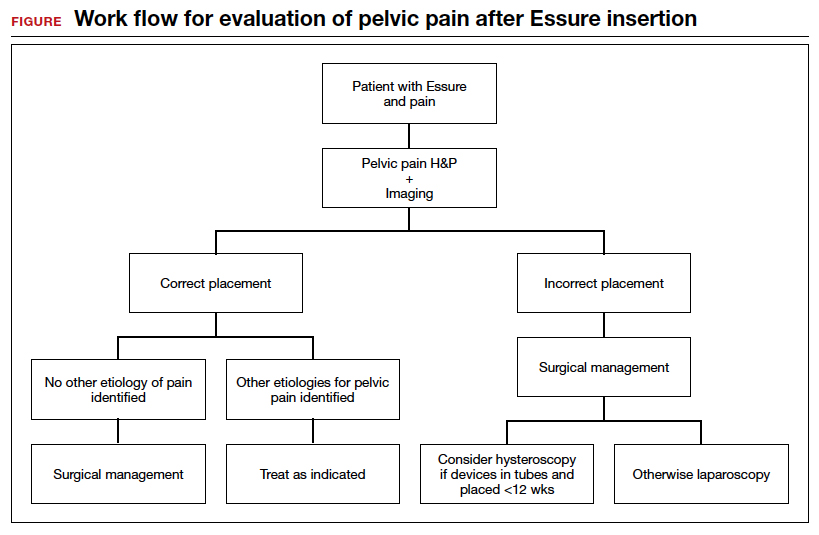

Workup and evaluation

We found 5 studies that provided some framework for evaluating a patient with new-onset or worsening pelvic pain after microinsert placement. Overall, correct placement and functionality of the device should be confirmed by either hysterosalpingogram (HSG) or transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS). The gold standard to determine tubal occlusion is the HSG. However, TVUS may be a dependable alternative, and either test can accurately demonstrate Essure location.19 Patients often prefer TVUS over HSG due to the low cost, minimal discomfort, and short examination time.1 TVUS is a noninvasive and reasonable test to start the initial assessment. The Essure devices are highly echogenic on pelvic ultrasound and easily identifiable by the proximity of the device to the uterotubal junction and its relationship with the surrounding soft tissue. If the device perforates the peritoneal cavity, then the echogenic bowel can impede adequate visualization of the Essure microinsert. If the Essure insert is not visualized on TVUS, an HSG will not only confirm placement but also test insert functionality. After confirming correct placement of the device, the provider can proceed with standard workup for chronic pelvic pain.

If one or more of the devices are malpositioned, the devices are generally presumed to be the etiology of the new pain. Multiple case reports demonstrate pain due to Essure misconfiguration or perforation with subsequent resolution of symptoms after device removal.18,20,21 A case study by Alcantara and colleagues described a patient with chronic pelvic pain and an Essure coil that was curved in an elliptical shape, not adhering to the anatomic course of the fallopian tube. The patient reported pain resolution after laparoscopic removal of the device.20 Another case report by Mahmoud et al described a subserosal malpositioned device that caused acute pelvic pain 4 months after sterilization. The patient reported resolution of pain after the microinsert was removed via laparoscopy.21 These reports highlight the importance of considering malpositioned devices as the etiology of new pelvic pain after Essure placement.

Continue to: Device removal and patient outcomes...

Device removal and patient outcomes

Removal

Several studies that we evaluated included a discussion on the methods for Essure removal. which are divided into 2 general categories: hysteroscopy and laparoscopy.

Hysteroscopic removal is generally used when the device was placed less than 12 weeks prior to removal.7,19 After 12 weeks, removal is more difficult due to fibrosis within the fallopian tubes. A risk with hysteroscopic removal is failure to remove all fibers, which allows inflammation and fibrosis to continue.7 This risk is mitigated via laparoscopic hysterectomy or mini-cornuectomy with bilateral salpingectomy, where the devices can be removed en bloc and without excessive traction.

Laparoscopic Essure removal procedures described in the literature include salpingostomy and traction on the device, salpingectomy, and salpingectomy with mini-cornuectomy. The incision and traction method is typically performed via a 2- to 3-cm incision on the antimesial edge of the fallopian tube along with a circumferential incision to surround the interstitial tubal area. The implant is carefully extracted from the fallopian tube and cornua, and a salpingectomy is then performed.22 The implant is removed prior to the salpingectomy to ensure that the Essure device is removed in its entirety prior to performing a salpingectomy.

A prospective observational study evaluated laparoscopic removal of Essure devices in 80 women with or without cornual excision. Results suggest that the incision and traction method poses more technical difficulties than the cornuectomy approach.23 Surgeons reported significant difficulty controlling the tensile pressure with traction, whereas use of the cornuectomy approach eliminated this risk and decreased the risk of fragmentation and incomplete removal.23,24

Charavil and colleagues demonstrated in a prospective observational study that a vaginal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy is a feasible approach to Essure removal. Twenty-six vaginal hysterectomies with bilateral salpingectomy and Essure removal were performed without conversion to laparoscopy or laparotomy. The surgeons performed an en bloc removal of each hemiuterus along with the ipsilateral tube, which ensured complete removal of the Essure device. Each case was confirmed with an x-ray of the surgical specimen.25

If device fragmentation occurs, there are different methods recommended for locating fragments. A case report of bilateral uterine perforation after uncomplicated Essure placement used a preoperative computed tomography (CT) scan to locate the Essure fragments, but no intraoperative imaging was performed to confirm complete fragment removal.26 The patient continued reporting chronic pelvic pain and ultimately underwent exploratory laparotomy with intraoperative fluoroscopy. Using fluoroscopy, investigators identified omental fragments that were missed on preoperative CT imaging. Fluoroscopy is not commonly used intraoperatively, but it may have added benefit for localizing retained fragments.

A retrospective cohort study reviewed the use of intraoperative x-ray of the removed specimen to confirm complete Essure removal.27 If an x-ray of the removed specimen showed incomplete removal, an intraoperative pelvic x-ray was performed to locate missing fragments. X-ray of the removed devices confirmed complete removal in 63 of 72 patients (87.5%). Six of 9 women with an unsatisfactory specimen x-ray had no residual fragments identified during pelvic x-ray, and the device removal was deemed adequate. The remaining 3 women had radiologic evidence of incomplete device removal and required additional dissection for complete removal. Overall, use of x-ray or fluoroscopy is a relatively safe and accessible way to ensure complete removal of the Essure device and is worth consideration, especially when retained device fragments are suspected.

Symptom resolution

We reviewed 5 studies that examined pain outcomes after removal of the Essure devices. Casey et al found that 23 of 26 patients (88.5%) reported significant pain relief at the postoperative visit, while 3 of 26 (11.5%) reported persistent pelvic pain.2 Two of 3 case series examined other outcomes in addition to postoperative pelvic pain, including sexual function and activities of daily living.7,14 In the first case series by Brito and colleagues, 8 of 11 patients (72.7%) reported an improvement in pelvic pain, ability to perform daily activities, sexual life, and overall quality of life after Essure removal. For the remaining 3 patients with persistent pelvic pain after surgical removal of the device, 2 patients reported worsening pain symptoms and dyspareunia.14 In this study, 5 of 11 patients reported a history of chronic pelvic pain at baseline. In a retrospective case series by Clark et al, 28 of 32 women (87.5%) reported some improvement in all domains, with 24 of 32 patients (75%) reporting almost total or complete improvement in quality of life, sexual life, pelvic pain, and scores related to activities of daily living. Pain and quality-of-life scores were similar for women who underwent uterine-preserving surgery and for those who underwent hysterectomy. Ten of 32 women (31.3%) reported persistent or worsening symptoms after the Essure removal surgery. In these patients, the authors recommended consideration of other autoimmune and hypersensitivity etiologies.7

In a retrospective cohort study by Kamencic et al from 2002 to 2013 of 1,430 patients who underwent Essure placement with postplacement imaging, 62 patients (4.3%) required a second surgery after Essure placement due to pelvic pain.10 This study also found that 4 of 62 patients (0.3%) had no other obvious cause for the pelvic pain. All 4 of these women had complete resolution of their pain with removal of the Essure microinsert device. A prospective observational study by Chene e

Summary

Although Essure products were withdrawn from the market in the United States in 2018, many patients still experience significant AEs associated with the device. The goal of the perspectives and data presented here is to assist clinicians in addressing and managing the pain experienced by patients after device insertion. ●

- Connor VF. Essure: a review six years later. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16:282-290. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2009.02.009.

- Casey J, Aguirre F, Yunker A. Outcomes of laparoscopic removal of the Essure sterilization device for pelvic pain: a case series. Contraception. 2016;94:190-192. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2016.03.017.

- Jackson I. Essure device removed entirely from market, with 99% of unused birth control implants retrieved: FDA. AboutLawsuits.com. January 13, 2020. https://www.aboutlawsuits.com/Essure-removal-update-166509. Accessed June 7, 2022.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Labeling for permanent hysteroscopically-placed tubal implants intended for sterilization. October 31, 2016. https://www.fda.gov/media/96315/download. Accessed June 7, 2022.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA activities related to Essure. March 14, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/essure-permanent-birth-control/fda-activities-related-essure. Accessed June 8, 2022.

- Arjona Berral JE, Rodríguez Jiménez B, Velasco Sánchez E, et al. Essure and chronic pelvic pain: a population-based cohort. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;34:712-713. doi:10.3109/01443615.2014.92075.

- Clark NV, Rademaker D, Mushinski AA, et al. Essure removal for the treatment of device-attributed symptoms: an expanded case series and follow-up survey. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:971-976. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2017.05.015.

- Sills ES, Rickers NS, Li X. Surgical management after hysteroscopic sterilization: minimally invasive approach incorporating intraoperative fluoroscopy for symptomatic patients with >2 Essure devices. Surg Technol Int. 2018;32:156-161.

- Administration USF and D. 522 Postmarket Surveillance Studies. Center for Devices and Radiological Health; 2020.

- Kamencic H, Thiel L, Karreman E, et al. Does Essure cause significant de novo pain? A retrospective review of indications for second surgeries after Essure placement. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:1158-1162. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2016.08.823.

- Yunker AC, Ritch JM, Robinson EF, et al. Incidence and risk factors for chronic pelvic pain after hysteroscopic sterilization. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:390-994. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2014.06.007.

- Phillips K, Clauw DJ. Central pain mechanisms in chronic pain states--maybe it is all in their head. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25:141-154. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2011.02.005.

- van Limburg Stirum EVJ, Clark NV, Lindsey A, et al. Factors associated with negative patient experiences with Essure sterilization. JSLS. 2020;24(1):e2019.00065. doi:10.4293/JSLS.2019.00065.

- Brito LG, Cohen SL, Goggins ER, et al. Essure surgical removal and subsequent symptom resolution: case series and follow-up survey. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:910-913. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2015.03.018.

- Maassen LW, van Gastel DM, Haveman I, et al. Removal of Essure sterilization devices: a retrospective cohort study in the Netherlands. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:1056-1062. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2018.10.009.

- Sills ES, Palermo GD. Surgical excision of Essure devices with ESHRE class IIb uterine malformation: sequential hysteroscopic-laparoscopic approach to the septate uterus. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2016;8:49-52.

- Ricci G, Restaino S, Di Lorenzo G, et al. Risk of Essure microinsert abdominal migration: case report and review of literature. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2014;10:963-968. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S65634.

- Borley J, Shabajee N, Tan TL. A kink is not always a perforation: assessing Essure hysteroscopic sterilization placement. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:2429.e15-7. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.02.006.

- Djeffal H, Blouet M, Pizzoferato AC, et al. Imaging findings in Essure-related complications: a pictorial review.7Br J Radiol. 2018;91(1090):20170686. doi:10.1259/bjr.20170686.

- Lora Alcantara I, Rezai S, Kirby C, et al. Essure surgical removal and subsequent resolution of chronic pelvic pain: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2016;2016:6961202. doi:10.1155/2016/6961202.

- Mahmoud MS, Fridman D, Merhi ZO. Subserosal misplacement of Essure device manifested by late-onset acute pelvic pain. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:2038.e1-3. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.07.1677.

- Tissot M, Petry S, Lecointre L, et al. Two surgical techniques for Essure device ablation: the hysteroscopic way and the laparoscopic way by salpingectomy with tubal interstitial resection. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26(4):603. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2018.07.017.

- Chene G, Cerruto E, Moret S, et al. Quality of life after laparoscopic removal of Essure sterilization devices. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X. 2019;3:100054. doi:10.1016/j.eurox.2019.100054.

- Thiel L, Rattray D, Thiel J. Laparoscopic cornuectomy as a technique for removal of Essure microinserts. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24(1):10. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2016.07.004.

- Charavil A, Agostini A, Rambeaud C, et al. Vaginal hysterectomy with salpingectomy for Essure insert removal. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;2:695-701. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2018.07.019.

- Howard DL, Christenson PJ, Strickland JL. Use of intraoperative fluoroscopy during laparotomy to identify fragments of retained Essure microinserts: case report. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19:667-670. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2012.04.007.

- Miquel L, Crochet P, Francini S, et al. Laparoscopic Essure device removal by en bloc salpingectomy-cornuectomy with intraoperative x-ray checking: a retrospective cohort study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:697-703. doi:10.1016/j. jmig.2019.06.006.

The evaluation and management of chronic pelvic pain in patients with a history of Essure device (Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc, Whippany, New Jersey) insertion have posed many challenges for both clinicians and patients. The availability of high-quality, evidence-based clinical guidance has been limited. We have reviewed the currently available published data, and here provide an overview of takeaways, as well as share our perspective and approach on evaluating and managing chronic pelvic pain in this unique patient population.

The device

The Essure microinsert is a hysteroscopically placed device that facilitates permanent sterilization by occluding the bilateral proximal fallopian tubes. The microinsert has an inner and outer nitinol coil that attaches the device to the proximal fallopian tube to ensure retention. The inner coil releases polyethylene terephthalate fibers that cause tubal fiber proliferation to occlude the lumen of the fallopian tube and achieve sterilization.

The device was first approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2002. In subsequent years, the device was well received and widely used, with approximately 750,000 women worldwide undergoing Essure placement.1,2 Shortly after approval, many adverse events (AEs), including pelvic pain and abnormal uterine bleeding, were reported, resulting in a public meeting of the FDA Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel in September 2015. A postmarket surveillance study on the device ensued to assess complication rates including unplanned pregnancy, pelvic pain, and surgery for removal. In February 2016, the FDA issued a black box warning and a patient decision checklist.3,4 In December 2018, Bayer stopped selling and distributing Essure in the United States.5 A 4-year follow-up surveillance study on Essure was submitted to the FDA in March 2020.

Adverse outcomes

Common AEs related to the Essure device include heavy uterine bleeding, pelvic pain, and other quality-of-life symptoms such as fatigue and weight gain.6-8 The main safety endpoints for the mandated FDA postmarket 522 surveillance studies were chronic lower abdominal and pelvic pain; abnormal uterine bleeding; hypersensitivity; allergic reaction, as well as autoimmune disorders incorporating inflammatory markers and human leukocyte antigen; and gynecologic surgery for device removal.9 Postmarket surveillence has shown that most AEs are related to placement complications or pelvic pain after Essure insertion. However, there have been several reports of autoimmune diseases categorized as serious AEs, such as new-onset systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and worsening ulcerative colitis, after Essure insertion.5

Evaluation of symptoms

Prevalence of pelvic pain following device placement

We conducted a PubMed and MEDLINE search from January 2000 to May 2020, which identified 43 studies citing AEs related to device placement, including pelvic or abdominal pain, abnormal uterine bleeding, hypersensitivity, and autoimmune disorders. A particularly debilitating and frequently cited AE was new-onset pelvic pain or worsening of preexisting pelvic pain. Perforation of the uterus or fallopian tube, resulting in displacement of the device into the peritoneal cavity, or fragmentation of the microinsert was reported as a serious AE that occurred after device placement. However, due to the complexity of chronic pelvic pain pathogenesis, the effect of the insert on patients with existing chronic pelvic pain remains unknown.

Authors of a large retrospective study found that approximately 2.7% of 1,430 patients developed new-onset or worsening pelvic pain after device placement. New-onset pelvic pain in 1% of patients was thought to be secondary to device placement, without a coexisting pathology or diagnosis.10

In a retrospective study by Clark and colleagues, 22 of 50 women (44%) with pelvic pain after microinsert placement were found to have at least one other cause of pelvic pain. The most common alternative diagnoses were endometriosis, adenomyosis, salpingitis, and adhesive disease. Nine of the 50 patients (18%) were found to have endometriosis upon surgical removal of the microinsert.7

Another case series examined outcomes in 29 patients undergoing laparoscopic device removal due to new-onset pelvic pain. Intraoperative findings included endometriosis in 5 patients (17.2%) and pelvic adhesions in 3 (10.3%).2 Chronic pelvic pain secondary to endometriosis may be exacerbated with Essure insertion due to discontinuation of hormonal birth control after device placement,7 and this diagnosis along with adenomyosis should be strongly considered in patients whose pelvic pain began when hormonal contraception was discontinued after placement of the device.

Continue to: Risk factors...

Risk factors

Authors of a retrospective cohort study found that patients with prior diagnosis of a chronic pain syndrome, low back pain, headaches, or fibromyalgia were 5 to 6 times more likely to report acute and chronic pain after hysteroscopic sterilization with Essure.11 Since chronic pain is often thought to be driven by a hyperalgesic state of the central nervous system, as previously shown in patients with conditions such as vulvodynia, interstitial cystitis, and fibromyalgia,12 a hyperalgesic state can potentially explain why some patients are more susceptible to developing worsening pain.

Van Limburg and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study with prospective follow-up on 284 women who underwent Essure sterilization. Among these patients, 48% reported negative AEs; risk factors included young age at placement, increasing gravidity, and no prior abdominal surgery.13

Onset of pain

The timing and onset of pelvic pain vary widely, suggesting there is no particular time frame for this AE after device placement.2,6,14-18 A case series by Arjona and colleagues analyzed the incidence of chronic pelvic pain in 4,274 patients after Essure sterilization. Seven patients (0.16%) reported chronic pelvic pain that necessitated device removal. In 6 of the women, the pelvic pain began within 1 week of device placement. In 3 of the 6 cases, the surgeon reported the removal procedures as “difficult.” In all 6 cases, the level of pelvic pain increased with time and was not alleviated with standard analgesic medications.6

In another case series of 26 patients, the authors evaluated patients undergoing laparoscopic removal of Essure secondary to pelvic pain and reported that the time range for symptom presentation was immediate to 85 months. Thirteen of 26 patients (50%) reported pain onset within less than 1 month of device placement, 5 of 26 patients (19.2%) reported pain between 1 and 12 months after device placement, and 8 of 26 patients (30.8%) reported pain onset more than 12 months after microinsert placement.2 In this study, 17.2% of operative reports indicated difficulty with device placement. It is unclear whether difficulty with placement was associated with development of subsequent abdominal or pelvic pain; however, the relevance of initial insertion difficulty diminished with longer follow-up.

Workup and evaluation

We found 5 studies that provided some framework for evaluating a patient with new-onset or worsening pelvic pain after microinsert placement. Overall, correct placement and functionality of the device should be confirmed by either hysterosalpingogram (HSG) or transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS). The gold standard to determine tubal occlusion is the HSG. However, TVUS may be a dependable alternative, and either test can accurately demonstrate Essure location.19 Patients often prefer TVUS over HSG due to the low cost, minimal discomfort, and short examination time.1 TVUS is a noninvasive and reasonable test to start the initial assessment. The Essure devices are highly echogenic on pelvic ultrasound and easily identifiable by the proximity of the device to the uterotubal junction and its relationship with the surrounding soft tissue. If the device perforates the peritoneal cavity, then the echogenic bowel can impede adequate visualization of the Essure microinsert. If the Essure insert is not visualized on TVUS, an HSG will not only confirm placement but also test insert functionality. After confirming correct placement of the device, the provider can proceed with standard workup for chronic pelvic pain.

If one or more of the devices are malpositioned, the devices are generally presumed to be the etiology of the new pain. Multiple case reports demonstrate pain due to Essure misconfiguration or perforation with subsequent resolution of symptoms after device removal.18,20,21 A case study by Alcantara and colleagues described a patient with chronic pelvic pain and an Essure coil that was curved in an elliptical shape, not adhering to the anatomic course of the fallopian tube. The patient reported pain resolution after laparoscopic removal of the device.20 Another case report by Mahmoud et al described a subserosal malpositioned device that caused acute pelvic pain 4 months after sterilization. The patient reported resolution of pain after the microinsert was removed via laparoscopy.21 These reports highlight the importance of considering malpositioned devices as the etiology of new pelvic pain after Essure placement.

Continue to: Device removal and patient outcomes...

Device removal and patient outcomes

Removal

Several studies that we evaluated included a discussion on the methods for Essure removal. which are divided into 2 general categories: hysteroscopy and laparoscopy.

Hysteroscopic removal is generally used when the device was placed less than 12 weeks prior to removal.7,19 After 12 weeks, removal is more difficult due to fibrosis within the fallopian tubes. A risk with hysteroscopic removal is failure to remove all fibers, which allows inflammation and fibrosis to continue.7 This risk is mitigated via laparoscopic hysterectomy or mini-cornuectomy with bilateral salpingectomy, where the devices can be removed en bloc and without excessive traction.

Laparoscopic Essure removal procedures described in the literature include salpingostomy and traction on the device, salpingectomy, and salpingectomy with mini-cornuectomy. The incision and traction method is typically performed via a 2- to 3-cm incision on the antimesial edge of the fallopian tube along with a circumferential incision to surround the interstitial tubal area. The implant is carefully extracted from the fallopian tube and cornua, and a salpingectomy is then performed.22 The implant is removed prior to the salpingectomy to ensure that the Essure device is removed in its entirety prior to performing a salpingectomy.

A prospective observational study evaluated laparoscopic removal of Essure devices in 80 women with or without cornual excision. Results suggest that the incision and traction method poses more technical difficulties than the cornuectomy approach.23 Surgeons reported significant difficulty controlling the tensile pressure with traction, whereas use of the cornuectomy approach eliminated this risk and decreased the risk of fragmentation and incomplete removal.23,24

Charavil and colleagues demonstrated in a prospective observational study that a vaginal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy is a feasible approach to Essure removal. Twenty-six vaginal hysterectomies with bilateral salpingectomy and Essure removal were performed without conversion to laparoscopy or laparotomy. The surgeons performed an en bloc removal of each hemiuterus along with the ipsilateral tube, which ensured complete removal of the Essure device. Each case was confirmed with an x-ray of the surgical specimen.25

If device fragmentation occurs, there are different methods recommended for locating fragments. A case report of bilateral uterine perforation after uncomplicated Essure placement used a preoperative computed tomography (CT) scan to locate the Essure fragments, but no intraoperative imaging was performed to confirm complete fragment removal.26 The patient continued reporting chronic pelvic pain and ultimately underwent exploratory laparotomy with intraoperative fluoroscopy. Using fluoroscopy, investigators identified omental fragments that were missed on preoperative CT imaging. Fluoroscopy is not commonly used intraoperatively, but it may have added benefit for localizing retained fragments.

A retrospective cohort study reviewed the use of intraoperative x-ray of the removed specimen to confirm complete Essure removal.27 If an x-ray of the removed specimen showed incomplete removal, an intraoperative pelvic x-ray was performed to locate missing fragments. X-ray of the removed devices confirmed complete removal in 63 of 72 patients (87.5%). Six of 9 women with an unsatisfactory specimen x-ray had no residual fragments identified during pelvic x-ray, and the device removal was deemed adequate. The remaining 3 women had radiologic evidence of incomplete device removal and required additional dissection for complete removal. Overall, use of x-ray or fluoroscopy is a relatively safe and accessible way to ensure complete removal of the Essure device and is worth consideration, especially when retained device fragments are suspected.

Symptom resolution

We reviewed 5 studies that examined pain outcomes after removal of the Essure devices. Casey et al found that 23 of 26 patients (88.5%) reported significant pain relief at the postoperative visit, while 3 of 26 (11.5%) reported persistent pelvic pain.2 Two of 3 case series examined other outcomes in addition to postoperative pelvic pain, including sexual function and activities of daily living.7,14 In the first case series by Brito and colleagues, 8 of 11 patients (72.7%) reported an improvement in pelvic pain, ability to perform daily activities, sexual life, and overall quality of life after Essure removal. For the remaining 3 patients with persistent pelvic pain after surgical removal of the device, 2 patients reported worsening pain symptoms and dyspareunia.14 In this study, 5 of 11 patients reported a history of chronic pelvic pain at baseline. In a retrospective case series by Clark et al, 28 of 32 women (87.5%) reported some improvement in all domains, with 24 of 32 patients (75%) reporting almost total or complete improvement in quality of life, sexual life, pelvic pain, and scores related to activities of daily living. Pain and quality-of-life scores were similar for women who underwent uterine-preserving surgery and for those who underwent hysterectomy. Ten of 32 women (31.3%) reported persistent or worsening symptoms after the Essure removal surgery. In these patients, the authors recommended consideration of other autoimmune and hypersensitivity etiologies.7

In a retrospective cohort study by Kamencic et al from 2002 to 2013 of 1,430 patients who underwent Essure placement with postplacement imaging, 62 patients (4.3%) required a second surgery after Essure placement due to pelvic pain.10 This study also found that 4 of 62 patients (0.3%) had no other obvious cause for the pelvic pain. All 4 of these women had complete resolution of their pain with removal of the Essure microinsert device. A prospective observational study by Chene e

Summary

Although Essure products were withdrawn from the market in the United States in 2018, many patients still experience significant AEs associated with the device. The goal of the perspectives and data presented here is to assist clinicians in addressing and managing the pain experienced by patients after device insertion. ●

The evaluation and management of chronic pelvic pain in patients with a history of Essure device (Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc, Whippany, New Jersey) insertion have posed many challenges for both clinicians and patients. The availability of high-quality, evidence-based clinical guidance has been limited. We have reviewed the currently available published data, and here provide an overview of takeaways, as well as share our perspective and approach on evaluating and managing chronic pelvic pain in this unique patient population.

The device

The Essure microinsert is a hysteroscopically placed device that facilitates permanent sterilization by occluding the bilateral proximal fallopian tubes. The microinsert has an inner and outer nitinol coil that attaches the device to the proximal fallopian tube to ensure retention. The inner coil releases polyethylene terephthalate fibers that cause tubal fiber proliferation to occlude the lumen of the fallopian tube and achieve sterilization.

The device was first approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2002. In subsequent years, the device was well received and widely used, with approximately 750,000 women worldwide undergoing Essure placement.1,2 Shortly after approval, many adverse events (AEs), including pelvic pain and abnormal uterine bleeding, were reported, resulting in a public meeting of the FDA Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel in September 2015. A postmarket surveillance study on the device ensued to assess complication rates including unplanned pregnancy, pelvic pain, and surgery for removal. In February 2016, the FDA issued a black box warning and a patient decision checklist.3,4 In December 2018, Bayer stopped selling and distributing Essure in the United States.5 A 4-year follow-up surveillance study on Essure was submitted to the FDA in March 2020.

Adverse outcomes

Common AEs related to the Essure device include heavy uterine bleeding, pelvic pain, and other quality-of-life symptoms such as fatigue and weight gain.6-8 The main safety endpoints for the mandated FDA postmarket 522 surveillance studies were chronic lower abdominal and pelvic pain; abnormal uterine bleeding; hypersensitivity; allergic reaction, as well as autoimmune disorders incorporating inflammatory markers and human leukocyte antigen; and gynecologic surgery for device removal.9 Postmarket surveillence has shown that most AEs are related to placement complications or pelvic pain after Essure insertion. However, there have been several reports of autoimmune diseases categorized as serious AEs, such as new-onset systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and worsening ulcerative colitis, after Essure insertion.5

Evaluation of symptoms

Prevalence of pelvic pain following device placement

We conducted a PubMed and MEDLINE search from January 2000 to May 2020, which identified 43 studies citing AEs related to device placement, including pelvic or abdominal pain, abnormal uterine bleeding, hypersensitivity, and autoimmune disorders. A particularly debilitating and frequently cited AE was new-onset pelvic pain or worsening of preexisting pelvic pain. Perforation of the uterus or fallopian tube, resulting in displacement of the device into the peritoneal cavity, or fragmentation of the microinsert was reported as a serious AE that occurred after device placement. However, due to the complexity of chronic pelvic pain pathogenesis, the effect of the insert on patients with existing chronic pelvic pain remains unknown.

Authors of a large retrospective study found that approximately 2.7% of 1,430 patients developed new-onset or worsening pelvic pain after device placement. New-onset pelvic pain in 1% of patients was thought to be secondary to device placement, without a coexisting pathology or diagnosis.10

In a retrospective study by Clark and colleagues, 22 of 50 women (44%) with pelvic pain after microinsert placement were found to have at least one other cause of pelvic pain. The most common alternative diagnoses were endometriosis, adenomyosis, salpingitis, and adhesive disease. Nine of the 50 patients (18%) were found to have endometriosis upon surgical removal of the microinsert.7

Another case series examined outcomes in 29 patients undergoing laparoscopic device removal due to new-onset pelvic pain. Intraoperative findings included endometriosis in 5 patients (17.2%) and pelvic adhesions in 3 (10.3%).2 Chronic pelvic pain secondary to endometriosis may be exacerbated with Essure insertion due to discontinuation of hormonal birth control after device placement,7 and this diagnosis along with adenomyosis should be strongly considered in patients whose pelvic pain began when hormonal contraception was discontinued after placement of the device.

Continue to: Risk factors...

Risk factors

Authors of a retrospective cohort study found that patients with prior diagnosis of a chronic pain syndrome, low back pain, headaches, or fibromyalgia were 5 to 6 times more likely to report acute and chronic pain after hysteroscopic sterilization with Essure.11 Since chronic pain is often thought to be driven by a hyperalgesic state of the central nervous system, as previously shown in patients with conditions such as vulvodynia, interstitial cystitis, and fibromyalgia,12 a hyperalgesic state can potentially explain why some patients are more susceptible to developing worsening pain.

Van Limburg and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study with prospective follow-up on 284 women who underwent Essure sterilization. Among these patients, 48% reported negative AEs; risk factors included young age at placement, increasing gravidity, and no prior abdominal surgery.13

Onset of pain

The timing and onset of pelvic pain vary widely, suggesting there is no particular time frame for this AE after device placement.2,6,14-18 A case series by Arjona and colleagues analyzed the incidence of chronic pelvic pain in 4,274 patients after Essure sterilization. Seven patients (0.16%) reported chronic pelvic pain that necessitated device removal. In 6 of the women, the pelvic pain began within 1 week of device placement. In 3 of the 6 cases, the surgeon reported the removal procedures as “difficult.” In all 6 cases, the level of pelvic pain increased with time and was not alleviated with standard analgesic medications.6

In another case series of 26 patients, the authors evaluated patients undergoing laparoscopic removal of Essure secondary to pelvic pain and reported that the time range for symptom presentation was immediate to 85 months. Thirteen of 26 patients (50%) reported pain onset within less than 1 month of device placement, 5 of 26 patients (19.2%) reported pain between 1 and 12 months after device placement, and 8 of 26 patients (30.8%) reported pain onset more than 12 months after microinsert placement.2 In this study, 17.2% of operative reports indicated difficulty with device placement. It is unclear whether difficulty with placement was associated with development of subsequent abdominal or pelvic pain; however, the relevance of initial insertion difficulty diminished with longer follow-up.

Workup and evaluation

We found 5 studies that provided some framework for evaluating a patient with new-onset or worsening pelvic pain after microinsert placement. Overall, correct placement and functionality of the device should be confirmed by either hysterosalpingogram (HSG) or transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS). The gold standard to determine tubal occlusion is the HSG. However, TVUS may be a dependable alternative, and either test can accurately demonstrate Essure location.19 Patients often prefer TVUS over HSG due to the low cost, minimal discomfort, and short examination time.1 TVUS is a noninvasive and reasonable test to start the initial assessment. The Essure devices are highly echogenic on pelvic ultrasound and easily identifiable by the proximity of the device to the uterotubal junction and its relationship with the surrounding soft tissue. If the device perforates the peritoneal cavity, then the echogenic bowel can impede adequate visualization of the Essure microinsert. If the Essure insert is not visualized on TVUS, an HSG will not only confirm placement but also test insert functionality. After confirming correct placement of the device, the provider can proceed with standard workup for chronic pelvic pain.

If one or more of the devices are malpositioned, the devices are generally presumed to be the etiology of the new pain. Multiple case reports demonstrate pain due to Essure misconfiguration or perforation with subsequent resolution of symptoms after device removal.18,20,21 A case study by Alcantara and colleagues described a patient with chronic pelvic pain and an Essure coil that was curved in an elliptical shape, not adhering to the anatomic course of the fallopian tube. The patient reported pain resolution after laparoscopic removal of the device.20 Another case report by Mahmoud et al described a subserosal malpositioned device that caused acute pelvic pain 4 months after sterilization. The patient reported resolution of pain after the microinsert was removed via laparoscopy.21 These reports highlight the importance of considering malpositioned devices as the etiology of new pelvic pain after Essure placement.

Continue to: Device removal and patient outcomes...

Device removal and patient outcomes

Removal

Several studies that we evaluated included a discussion on the methods for Essure removal. which are divided into 2 general categories: hysteroscopy and laparoscopy.

Hysteroscopic removal is generally used when the device was placed less than 12 weeks prior to removal.7,19 After 12 weeks, removal is more difficult due to fibrosis within the fallopian tubes. A risk with hysteroscopic removal is failure to remove all fibers, which allows inflammation and fibrosis to continue.7 This risk is mitigated via laparoscopic hysterectomy or mini-cornuectomy with bilateral salpingectomy, where the devices can be removed en bloc and without excessive traction.

Laparoscopic Essure removal procedures described in the literature include salpingostomy and traction on the device, salpingectomy, and salpingectomy with mini-cornuectomy. The incision and traction method is typically performed via a 2- to 3-cm incision on the antimesial edge of the fallopian tube along with a circumferential incision to surround the interstitial tubal area. The implant is carefully extracted from the fallopian tube and cornua, and a salpingectomy is then performed.22 The implant is removed prior to the salpingectomy to ensure that the Essure device is removed in its entirety prior to performing a salpingectomy.

A prospective observational study evaluated laparoscopic removal of Essure devices in 80 women with or without cornual excision. Results suggest that the incision and traction method poses more technical difficulties than the cornuectomy approach.23 Surgeons reported significant difficulty controlling the tensile pressure with traction, whereas use of the cornuectomy approach eliminated this risk and decreased the risk of fragmentation and incomplete removal.23,24

Charavil and colleagues demonstrated in a prospective observational study that a vaginal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy is a feasible approach to Essure removal. Twenty-six vaginal hysterectomies with bilateral salpingectomy and Essure removal were performed without conversion to laparoscopy or laparotomy. The surgeons performed an en bloc removal of each hemiuterus along with the ipsilateral tube, which ensured complete removal of the Essure device. Each case was confirmed with an x-ray of the surgical specimen.25

If device fragmentation occurs, there are different methods recommended for locating fragments. A case report of bilateral uterine perforation after uncomplicated Essure placement used a preoperative computed tomography (CT) scan to locate the Essure fragments, but no intraoperative imaging was performed to confirm complete fragment removal.26 The patient continued reporting chronic pelvic pain and ultimately underwent exploratory laparotomy with intraoperative fluoroscopy. Using fluoroscopy, investigators identified omental fragments that were missed on preoperative CT imaging. Fluoroscopy is not commonly used intraoperatively, but it may have added benefit for localizing retained fragments.

A retrospective cohort study reviewed the use of intraoperative x-ray of the removed specimen to confirm complete Essure removal.27 If an x-ray of the removed specimen showed incomplete removal, an intraoperative pelvic x-ray was performed to locate missing fragments. X-ray of the removed devices confirmed complete removal in 63 of 72 patients (87.5%). Six of 9 women with an unsatisfactory specimen x-ray had no residual fragments identified during pelvic x-ray, and the device removal was deemed adequate. The remaining 3 women had radiologic evidence of incomplete device removal and required additional dissection for complete removal. Overall, use of x-ray or fluoroscopy is a relatively safe and accessible way to ensure complete removal of the Essure device and is worth consideration, especially when retained device fragments are suspected.

Symptom resolution

We reviewed 5 studies that examined pain outcomes after removal of the Essure devices. Casey et al found that 23 of 26 patients (88.5%) reported significant pain relief at the postoperative visit, while 3 of 26 (11.5%) reported persistent pelvic pain.2 Two of 3 case series examined other outcomes in addition to postoperative pelvic pain, including sexual function and activities of daily living.7,14 In the first case series by Brito and colleagues, 8 of 11 patients (72.7%) reported an improvement in pelvic pain, ability to perform daily activities, sexual life, and overall quality of life after Essure removal. For the remaining 3 patients with persistent pelvic pain after surgical removal of the device, 2 patients reported worsening pain symptoms and dyspareunia.14 In this study, 5 of 11 patients reported a history of chronic pelvic pain at baseline. In a retrospective case series by Clark et al, 28 of 32 women (87.5%) reported some improvement in all domains, with 24 of 32 patients (75%) reporting almost total or complete improvement in quality of life, sexual life, pelvic pain, and scores related to activities of daily living. Pain and quality-of-life scores were similar for women who underwent uterine-preserving surgery and for those who underwent hysterectomy. Ten of 32 women (31.3%) reported persistent or worsening symptoms after the Essure removal surgery. In these patients, the authors recommended consideration of other autoimmune and hypersensitivity etiologies.7

In a retrospective cohort study by Kamencic et al from 2002 to 2013 of 1,430 patients who underwent Essure placement with postplacement imaging, 62 patients (4.3%) required a second surgery after Essure placement due to pelvic pain.10 This study also found that 4 of 62 patients (0.3%) had no other obvious cause for the pelvic pain. All 4 of these women had complete resolution of their pain with removal of the Essure microinsert device. A prospective observational study by Chene e

Summary

Although Essure products were withdrawn from the market in the United States in 2018, many patients still experience significant AEs associated with the device. The goal of the perspectives and data presented here is to assist clinicians in addressing and managing the pain experienced by patients after device insertion. ●

- Connor VF. Essure: a review six years later. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16:282-290. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2009.02.009.

- Casey J, Aguirre F, Yunker A. Outcomes of laparoscopic removal of the Essure sterilization device for pelvic pain: a case series. Contraception. 2016;94:190-192. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2016.03.017.

- Jackson I. Essure device removed entirely from market, with 99% of unused birth control implants retrieved: FDA. AboutLawsuits.com. January 13, 2020. https://www.aboutlawsuits.com/Essure-removal-update-166509. Accessed June 7, 2022.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Labeling for permanent hysteroscopically-placed tubal implants intended for sterilization. October 31, 2016. https://www.fda.gov/media/96315/download. Accessed June 7, 2022.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA activities related to Essure. March 14, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/essure-permanent-birth-control/fda-activities-related-essure. Accessed June 8, 2022.

- Arjona Berral JE, Rodríguez Jiménez B, Velasco Sánchez E, et al. Essure and chronic pelvic pain: a population-based cohort. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;34:712-713. doi:10.3109/01443615.2014.92075.

- Clark NV, Rademaker D, Mushinski AA, et al. Essure removal for the treatment of device-attributed symptoms: an expanded case series and follow-up survey. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:971-976. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2017.05.015.

- Sills ES, Rickers NS, Li X. Surgical management after hysteroscopic sterilization: minimally invasive approach incorporating intraoperative fluoroscopy for symptomatic patients with >2 Essure devices. Surg Technol Int. 2018;32:156-161.

- Administration USF and D. 522 Postmarket Surveillance Studies. Center for Devices and Radiological Health; 2020.

- Kamencic H, Thiel L, Karreman E, et al. Does Essure cause significant de novo pain? A retrospective review of indications for second surgeries after Essure placement. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:1158-1162. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2016.08.823.

- Yunker AC, Ritch JM, Robinson EF, et al. Incidence and risk factors for chronic pelvic pain after hysteroscopic sterilization. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:390-994. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2014.06.007.