Quiz

Painful Purple Toes

- Author:

- Chika Ohata, MD, PhD

- Taichi Imamura, MD

Article

Brown Macule on the Waist

- Author:

- Chika Ohata, MD, PhD

Article

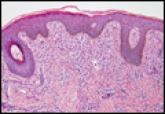

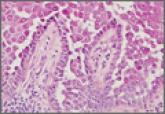

Hailey-Hailey Disease

- Author:

- Chika Ohata, MD, PhD

Hailey-Hailey disease typically presents as suprabasal blisters with a perivascular and interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate. The differential...