User login

A Novel Approach to Physician Shortages

The demand for physician talent is intensifying as the US healthcare system confronts an unprecedented confluence of demographic pressures. Not only will 78 million retiring baby‐boomers require significant healthcare resources, but tens of thousands of practicing physicians will themselves reach retirement age within the next decade.1 At the same time, factors like the large increase in the percentage of female physicians (who are more likely to work part time), the growth of nonpractice opportunities for MDs, and generational demands for greater worklife balance are creating a major supply‐demand mismatch within the physician workforce.2 In this demographic atmosphere, the ability to recruit and retain physician leaders confers tremendous value to healthcare enterprisesboth public and private. Recruiting and retaining strategies already weigh heavily in the most palpable shortage areas, like primary care, but the system faces widespread unmet demand for a variety of specialist and generalist practitioners.36

This article does not address the public policy implications of the upcoming physician shortage, recognition of which will lead to the largest increase in new medical school slots in decades.7 Rather, we set out to illustrate how successful nonmedical businesses are embracing a thoughtful, systematic approach to retaining talent, based on the philosophy that keeping and engaging valued employees is more efficient than recruiting and orienting replacements. We posit that the innovations used by progressive companies could apply to recruitment and retention challenges confronting medicine.

How Industry Approaches the Talent Vacuum: Talent Facilitation

Leaders outside of medicine have long acknowledged that changing demographics and a global economy are driving unprecedented employee turnover.8 In confronting a talent vacuum, forward‐thinking managers have prioritized retaining key talent (rather than hiring anew) in planning for the future.9, 10 Doing so begins with attempts to understand the relationship between workers and the workplace, with a particular emphasis on appreciating workers' priorities. Indeed, new executive positions with titles like Chief Learning Officer and Chief Experience Officer are appearing as companies realize a need for focused expertise beyond traditional human resource departments. These companies understand that offering higher salaries is not the only retention strategyand often not even the most effective one.

The Four Actions of Talent Facilitation

The talent facilitation process centers on four actions: attract, engage, develop, and retain. None of these actions can stand alone, and all should be present, to some degree, at all stages of a worker's tenure. To attract or engage an employee or practice partner is not a 1‐time hook, but a constant and dynamic process.

Importantly, the concepts addressed here are not specific to 1 type of corporate system, size, or management level. Although the early business focus had been on upper‐level and executive talent within large corporate settings, there is an increasing recognition that a dedicated talent strategy is useful wherever recruiting and retaining talented people is important (and where is it not?).

The ideas presented here may seem most applicable to leaders of large physician corporations, hospital‐owned physician groups, or large integrated healthcare systems (such as Kaiser) that employ physicians. However, we also believe that the ideas apply across‐the‐board in medicine, including entities such as small, private, physician‐owned groups. We argue that regardless of the exact practice structure, a limited pool of resources must be dedicated to the attraction and retention of talented partners or employees, or to the cost of replacing those people if they pursue other opportunities (or the cost of inefficient and disengaged physicians). While an integrated health system may have the resources and scale to hire a Chief Experience Officer, we do not anticipate that a 5‐partner private practice would. Rather, we point to examples to illustrate the talent facilitation paradigm as a tool to systematically frame the allocation of those resources. Undoubtedly, the specific shape of a thoughtful talent facilitation effort will vary when applied in a large urban academic medical center vs. an integrated healthcare system vs. a small physician private practice, but the basic principles remain the same.

Attract

Increasingly, companies approach talented prospects with dedicated marketing campaigns to convey the value of a work environment.11 Silicon Valley employee lounges with free massages and foosball tables are the iconic example of attraction, but the concept runs deeper. Today's workers seek access to state‐of‐the‐art ideas and technology and often want to be part of a larger vision. Many seek opportunities to integrate their own professional and personal aspirations into a particular job description.

Hospital executives have long recognized the importance of attracting physicians to their facility (after all, the physicians draw patients and thus generate revenue). The traditional approach has surrounded perks, from comfortable doctor's lounges to the latest in surgical technology. But, the stakes seem greater now than before, and successful talent facilitation strategies are going beyond the tried and true.

Clearly, physicians seek financially stable practice settings with historical success. But they may also seek evidence of a defined strategic plan focused on more than mere profitability. Physicians may gravitate to practice environments that endorse progressive movements like the No One Dies Alone campaign.12 Similarly, recognition of movements beyond healthcarea commitment to Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) (Green Building Rating System; US Green Building Council [USGBC];

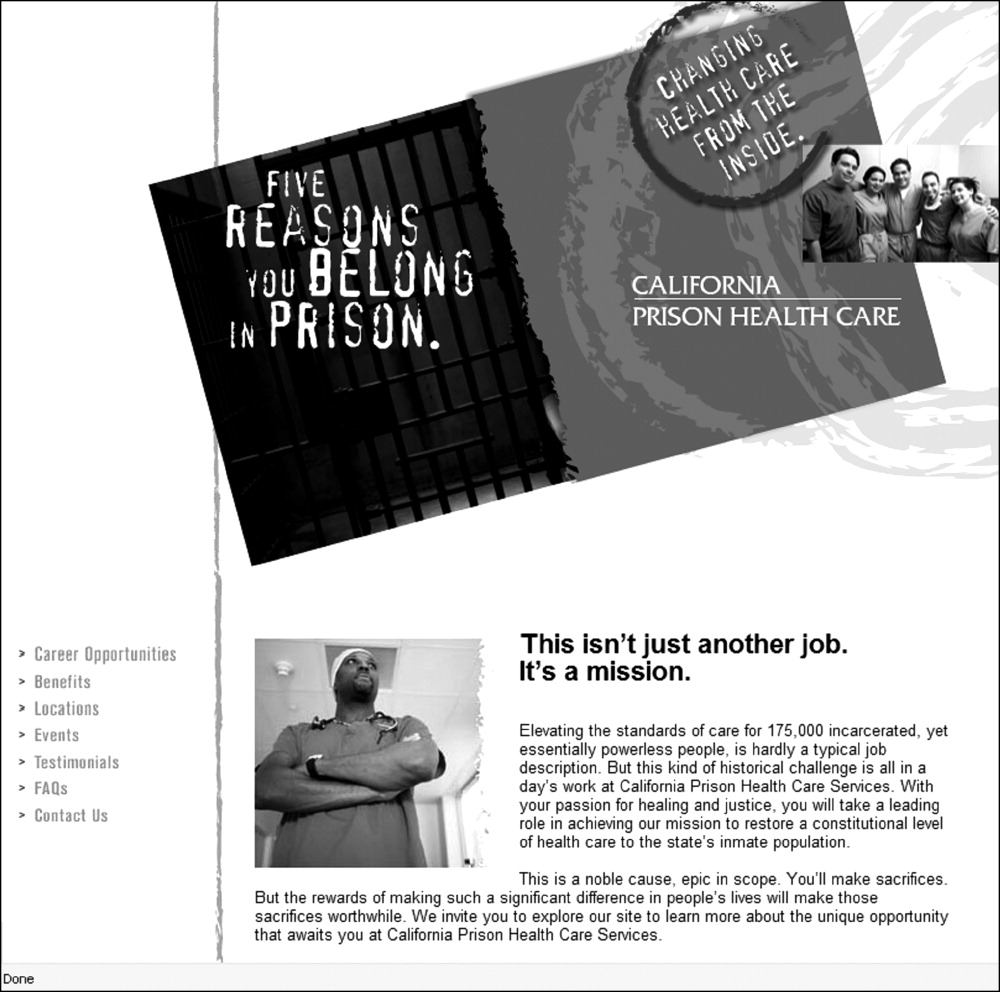

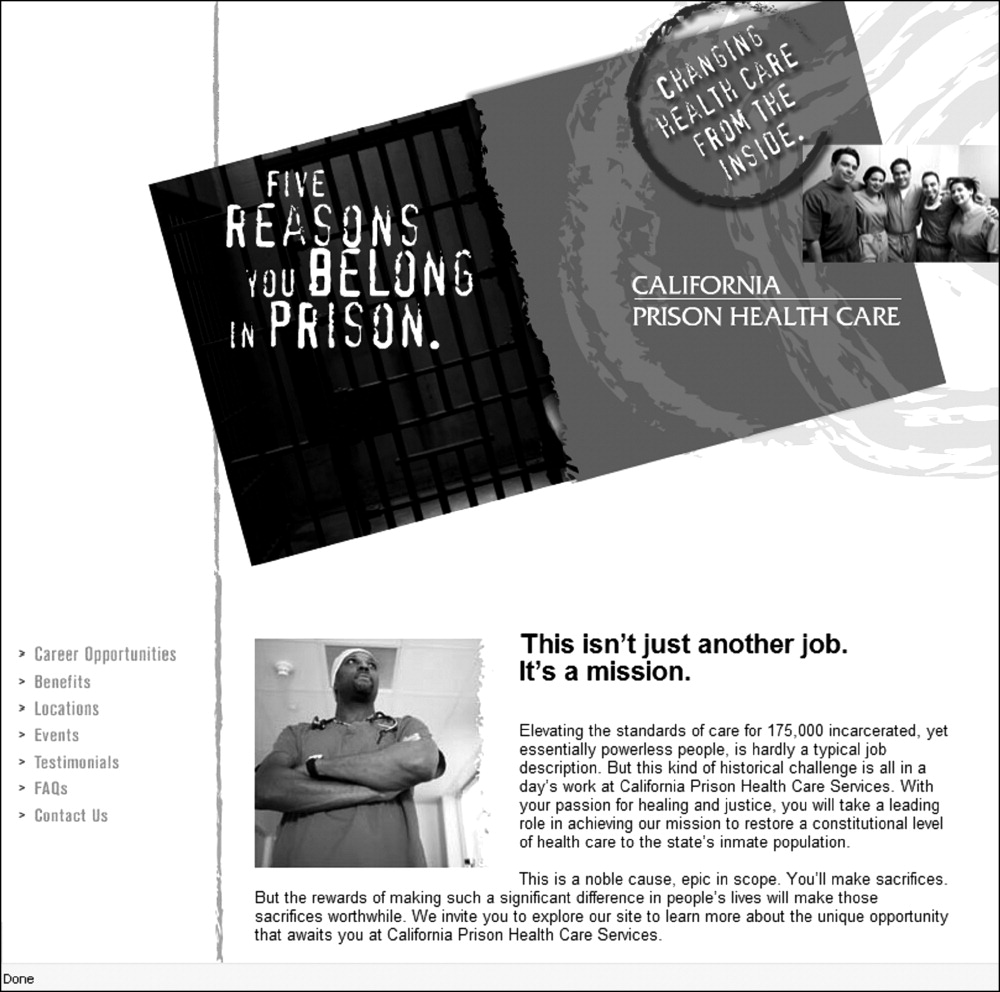

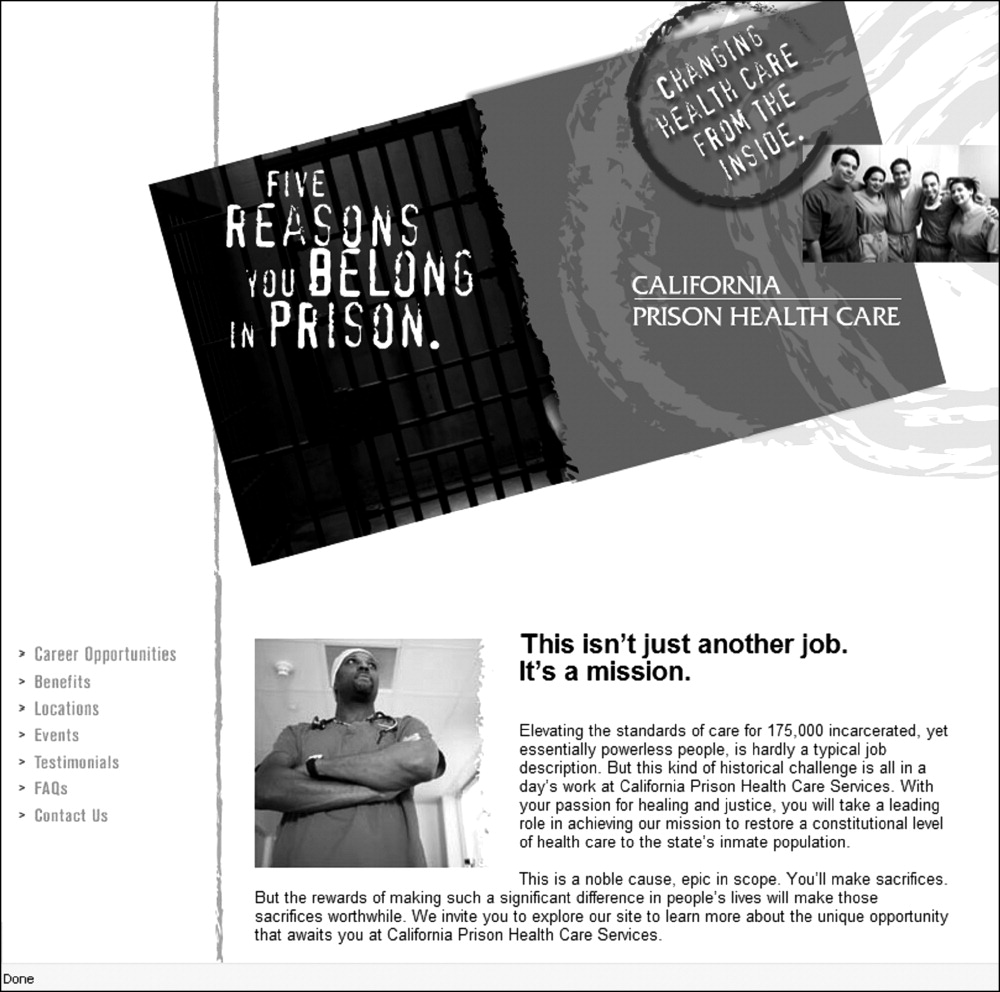

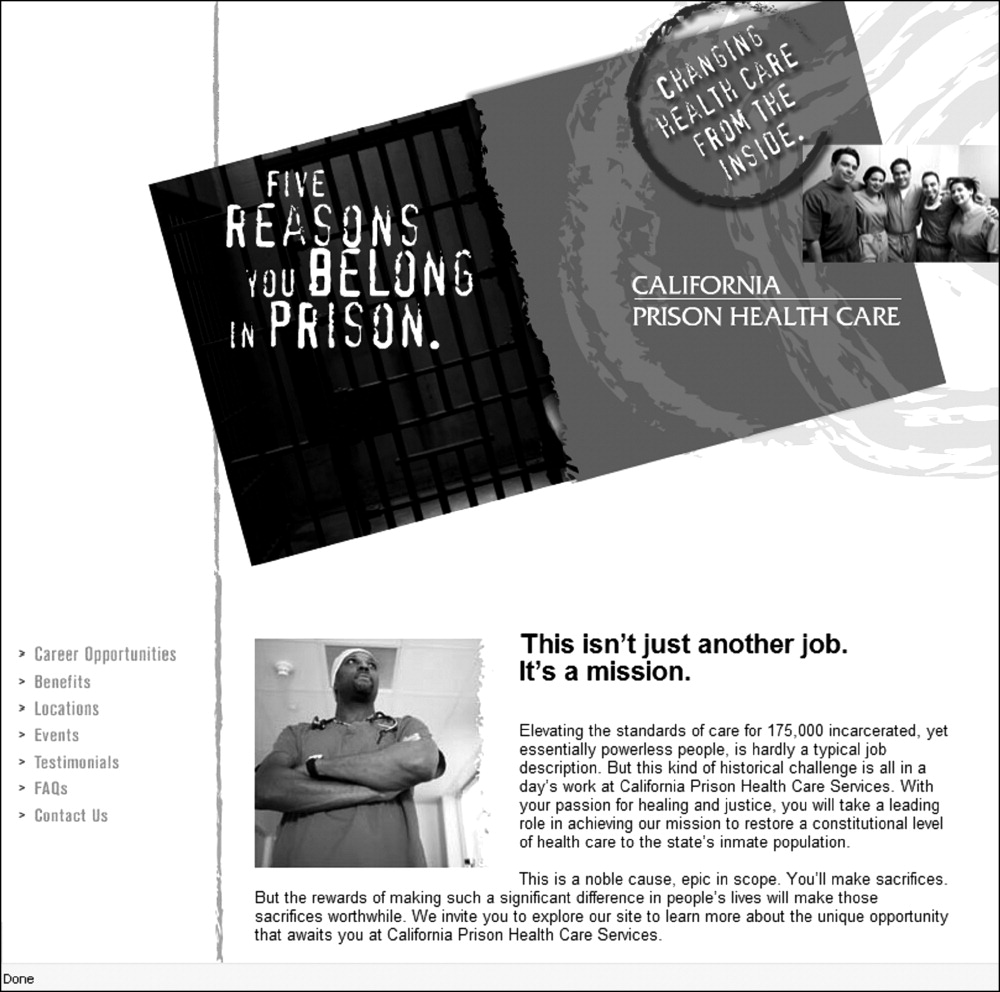

The current recruitment campaign of California's prison healthcare system offers an unlikely source of inspiration. The prison system was placed in receivership to address a shortage of competent physician staff and other inadequacies. A central feature of the campaign is an attractive starting salary and good benefits. But, the campaign does not rely on money alone. For example, the campaign's website (

Engage

The corporate tool being employed at this stage is a strategy called on‐boarding, which emphasizes a streamlined integration of newcomers with existing workers and culture, and prioritizes aligning organizational roles with a worker's specific skills and interests. On‐boarding also emphasizes the value of early and frequent provision of constructive feedback from same‐level peers or managers with advanced coaching skills.

Many companies use formal survey tools to measure employee engagement and regularly evaluate the proficiency of system leaders in the ability to engage their employees. An engineering firm executive recently told us (P.K., C.K.) that he performs detailed and frequent on‐the‐job interviews, even with company veterans. The primary goal of these interviews is to ensure that engineers spend at least 85% of their time on work that: (1) they find interesting and (2) allows for the application of their best skills. Wherever possible, traditional job descriptions are altered to achieve this. Inevitably, there is still work (15% in this particular corporate vision) that no one prefers but needs to get done, but this process of active recalibration minimizes this fraction to the degree possible.

Even within a small physician practice group, one can imagine how a strategic approach of inviting and acknowledging individual physician's professional goals and particular talents may challenge the long‐held belief that everyone within a group enjoys and must do the exact same job. Once these goals and talents are articulated, groups may find that allowing for more customized roles within the practice enhances professional satisfaction.

Social networking, collaboration, and sharing of best practices are staples of engaging companies. The Cisco and Qualcomm companies, for example, utilize elaborate e‐networks (rough corporate equivalents to Facebook) to foster collegial interaction within and across traditional hierarchical boundaries so that managers and executives directly engage the ideas of employees at every level.14 The premise is logical: engaged employees will be more likely to contribute innovative ideas which, when listened to, are more likely to engage employees.

Most physicians will recognize the traditional resident report as a model for engagement. Beyond its educational value, interaction with program leadership, social bonding, collaborative effort, and exploration of best practices add tremendous value. Many companies would jump at the chance to engrain a similar cultural staple. Enhancing this type of interaction in a postresidency setting may promote engagement in a given system, especially if it facilitates interactions between physicians and senior hospital leaders. Absent these types of interactions, ensuring regular provision of peer review and/or constructive feedback can help systematically enhance 2‐way communication and enhance engagement.

Develop

Talent development relies on mentorship reflecting a genuine interest in an individual's future. Development strategies include pairing formal annual talent reviews or (in the case of practice partners) formal peer review with strategic development plans. Effective development strategy may include transparent succession planning so that individuals are aware they are being groomed for future roles.

A well‐known adage suggests, People quit the manager or administrator, not the job. Development in this sense relies on presenting new opportunities and knowing that people flourish when allowed to explore multiple paths forward. In many companies, the role of Chief Experience or Chief Learning Officers is to enhance development planning. Consider how career coaching of young hospitalists could transform an infinitely portable and volatile commodity job, prone to burnout, into an engaged specialist of sorts with immense value to a hospital. Hospitalists have already demonstrated their potential as quality improvement leaders.15 Imagine if hospital leadership enlisted a young hospitalist in a relevant quality improvement task force, such as one working on preventing falls. With appropriate support, the physician could obtain skills for quality improvement evaluation that would not only enhance his or her engagement with the hospital system but also provide a valuable analysis for the hospital.

As an example of development strategy within a small practice setting, consider the following real‐life anecdote: a group of 4 physicians recently completed a long and expensive recruitment of a new partner. The new partner, intrigued by the local hospital's surgical robot technology, sought the support of her partners (who are not currently using the technology) to partake in an expensive robotics training program. The partners decided not to provide the financial support. The new partner subsequently left the group for a nearby practice opportunity that would provide for the training, and the group was faced with the loss of a partner (one‐fourth of the practice!) and the cost of repeating the recruiting process. A preemptive evaluation of the value of investing in the development of the new partner and enhancing that partner's professional development may have proven wise despite the significant up‐front costs. In this case the manager the new partner quit was the inflexibility of the practice trajectory.

Retain

The economic incentive to retain talented workers is not subtle. If it was, companies would not be funneling resources into Chief Experience Officers. Likewise, the estimated cost for a medical practice to replace an individual physician is as at least $250,000.16, 17

In retention, as in attraction, salary is only part of the equation.18 People want fair and competitive compensation, and may leave if they are not getting it, but they will not stay (and will not stay engaged) only for a salary bump. Retention is enhanced when workers can advance according to skills and talent, rather than mere tenure. An effective retention policy responds to people's desire to incorporate individual professional goals into their work and allows for people to customize their career rather than simply occupy a job class. Effective retention policy respects worklife balance and recognizes that this balance might look different for 2 people with the same job. It may take the form of positive reinforcement (rather than subtle disdain) for using vacation time or allowing for participation in international service projects. Many literally feel that they need to quit their job in order to take time off or explore other interests.

Worklife balance has been a longstanding issue in medicine, and innovative augmentation strategies may well help retain top talent. Today's successful medical school applicants not only show aptitude in the classroom, they often have many well‐developed nonmedical skills. No one can expect that medical training will somehow convince them to leave everything else behind. Moreover, today's residency graduates, already with Generation Y sensibilities, have completed their entire training under the auspices of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) duty hours regulations, which has made residents far more comfortable with shift work and defined hours.

At the other end of the generation spectrum, as large numbers of physicians ready for retirement, effective talent facilitation strategies may evaluate how to reoffer medicine as a valid option for senior physicians who still wish to work. Retaining these physicians will require an appreciation of their lifestyle goals, as they will likely find continuing a traditional practice role untenable. A recent survey of orthopedic surgeons 50 years of age or older found that having a part‐time option was a common reason they continued practicing, and that the option to work part‐time would have the most impact on keeping these surgeons working past age 65 years.19 Those working part‐time were doing so in a wide range of practice arrangements including private practice. However, one‐third of those surveyed said a part‐time option was not available to them. Clearly, in an environment of workforce shortages, physician‐leaders must begin to think about worklife balance not only for new doctors but for those considering retirement.

Critics will point out the financial drawbacks in the provision of worklife balance. But the cost may pale in comparison to the cost of replacing physician leaders. Moreover, engaged physicians are more likely to add value in the form of intangible capital such as patient satisfaction and practice innovation. As such, we argue that effective retention strategy in medicine is likely to be cost‐effective, even if it requires significant new up‐front resources.

Lessons From Industry

Doctors frequently assume that the challenges and obstacles confronted in healthcare are unique to medicine. But, for every phrase like When I started practice, I decided how long office visits were, not the insurance company, or Young doctors just don't want to work as hard, there is a parallel utterance in the greater business world. Luckily, there are now examples of the healthcare world learning lessons from business. For example, innovators in medical quality improvement found value in the experience of other industries.20 Airlines and automakers have long honed systems for error prevention and possess expertise that may curb errors in the hospital.2123

We suspect that the ideas and practice of talent facilitation have already made their way into some medical settings. A Google search reveals multiple opportunities for hospital‐based talent managers, and websites advertise the availability of talent consultants ready to lend their expertise to the medical world. In the arena of academic medicine, the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Division of Hospital Medicine put some of the ideas of talent facilitation into practice over the past year, in part in response to an increasingly competitive market for academic hospitalists.24 Leaders introduced a formal faculty development program that links junior faculty with mentors and facilitates early and frequent feedback across hierarchical boundaries.25 These more intentional mentoring efforts were accompanied by a seminar series aimed at the needs of new faculty members, a research incubator program, divisional grand rounds, and other web‐based and in‐person forums for sharing best practices and innovations. Less formal social events have also been promoted. Importantly, these sweeping strategies seek to encompass the needs of both teaching and nonteaching hospitalists within UCSF.26

Clearly, an academic hospitalist group with 45 faculty physicians has unique characteristics that inform the specifics of its talent facilitation strategy. The interventions discussed above are meant to represent examples of the types of strategies that may be utilized by physician groups once a decision is made to focus on talent management. Undoubtedly, the shape of such efforts will vary in diverse practice settings, but physician leaders have much to gain through further exploration of where these core principles already exist within medicine and where they may be more effectively deployed. By examining how multinational businesses are systematically applying the concepts of talent facilitation to address a global talent shortage, the doctoring profession might again take an outside hint to help inform its future.

- Long Term Care: Aging Baby Boom Generation Will Increase Demand and Burden on Federal and State Budgets. United States General Accounting Office Testimony before the Special Committee on Aging, US Senate. Hearing Before the Special Committee on Aging of the US Senate,2002. Available at:http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d02544t.pdf. Accessed July 2009.

- ,.Physician workforce shortages: implications and issues for academic health centers and policymakers.Acad Med.2006;81(9):782–787.

- .New York moves to tackle shortage of primary‐care doctors.Lancet.2008;371(9615):801–802.

- ,.The US dermatology workforce: a specialty remains in shortage.J Am Acad Dermatol.2008;59(5):741–745.

- ,.Challenges and opportunities for recruiting a new generation of neurosurgeons.Neurosurgery.2007;61(6):1314–1319.

- ,.The developing crisis in the national general surgery workforce.J Am Coll Surg.2008;206(5):790–795.

- Medical School Enrollment Plans: Analysis of the 2007 AAMC Survey. Publication of the Association of American Medical Colleges, Center for Workforce Studies, April2008. Available at:http://www.aamc.org/workforce. Accessed July 2009.

- It's 2008: Do You Know Where Your Talent Is? Why acquisition and retention strategies don't work. Part 1 of a Deloitte Research Series on Talent Management.2008. Available at: http://www.deloitte.com/dtt/cda/content/UKConsulting_TalentMgtResearchReport.pdf. Accessed August 2009.

- ,,.The race for talent: retaining and engaging workers in the 21st century.Hum Resour Plann.2004;27(3):12–25.

- Expecting sales growth, CEOs cite worker retention as critical to success. March 1,2004. Available at:http://www.barometersurveys.com/production/barsurv.nsf/89343582e94adb6185256b84006c8ffe/9672ab2f54cf99f885256e5500768232?OpenDocument. Accessed July 2009.

- Jet Blue announces aviation university gateway program for pilot candidates: airline partners with Embry‐Riddle Aeronautical University, University of North Dakota, and Cape Air to fill pilot pipeline. January 30, 2008. Available at:http://investor.jetblue.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=131045287(4):487–494.

- ,,.A review of physician turnover: rates, causes, and consequences.Am J Med Qual.2004;19(2):56–66.

- ,,.The impact on revenue of physician turnover: an assessment model and experience in a large healthcare center.J Med Pract Manage.2006;21(6):351–355.

- ,,.Employee motivation: a powerful new model.Harv Bus Rev.2008;86(7–8):78,84,160.

- ,,.Work satisfaction and retirement plans of orthopaedic surgeons 50 years of age or older.Clin Orthop Relat Res.2008;466(1):231–238.

- ,,,.The long road to patient safety: a status report on patient safety systems.JAMA.2005(22);294:2858–2865.

- .Error reduction through team leadership: what surgeons can learn from the airline industry.Clin Neurosurg.2007;54:195–199.

- ,.Applying the Toyota production system: using a patient safety alert system to reduce error.Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf.2007;33(7):376–386.

- ,,,.Improving Papanikolaou test quality and reducing medical errors by using Toyota production system methods.Am J Obstet Gynecol.2006;194(1):57–64.

- Society of Hospital Medicine Career Satisfaction Task Force. White Paper on Hospitalist Career Satisfaction.2006; 1–45. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org. Accessed July 2009.

- UCSF Department of Medicine, Division of Hospital Medicine, Faculty Development. Available at: http://hospsrvr.ucsf.edu/cme/fds.html. Accessed July 2009.

- ,,, et al. Non‐housestaff medicine services in academic centers: models and challenges.J Hosp Med.2008;3(3):247–245.

The demand for physician talent is intensifying as the US healthcare system confronts an unprecedented confluence of demographic pressures. Not only will 78 million retiring baby‐boomers require significant healthcare resources, but tens of thousands of practicing physicians will themselves reach retirement age within the next decade.1 At the same time, factors like the large increase in the percentage of female physicians (who are more likely to work part time), the growth of nonpractice opportunities for MDs, and generational demands for greater worklife balance are creating a major supply‐demand mismatch within the physician workforce.2 In this demographic atmosphere, the ability to recruit and retain physician leaders confers tremendous value to healthcare enterprisesboth public and private. Recruiting and retaining strategies already weigh heavily in the most palpable shortage areas, like primary care, but the system faces widespread unmet demand for a variety of specialist and generalist practitioners.36

This article does not address the public policy implications of the upcoming physician shortage, recognition of which will lead to the largest increase in new medical school slots in decades.7 Rather, we set out to illustrate how successful nonmedical businesses are embracing a thoughtful, systematic approach to retaining talent, based on the philosophy that keeping and engaging valued employees is more efficient than recruiting and orienting replacements. We posit that the innovations used by progressive companies could apply to recruitment and retention challenges confronting medicine.

How Industry Approaches the Talent Vacuum: Talent Facilitation

Leaders outside of medicine have long acknowledged that changing demographics and a global economy are driving unprecedented employee turnover.8 In confronting a talent vacuum, forward‐thinking managers have prioritized retaining key talent (rather than hiring anew) in planning for the future.9, 10 Doing so begins with attempts to understand the relationship between workers and the workplace, with a particular emphasis on appreciating workers' priorities. Indeed, new executive positions with titles like Chief Learning Officer and Chief Experience Officer are appearing as companies realize a need for focused expertise beyond traditional human resource departments. These companies understand that offering higher salaries is not the only retention strategyand often not even the most effective one.

The Four Actions of Talent Facilitation

The talent facilitation process centers on four actions: attract, engage, develop, and retain. None of these actions can stand alone, and all should be present, to some degree, at all stages of a worker's tenure. To attract or engage an employee or practice partner is not a 1‐time hook, but a constant and dynamic process.

Importantly, the concepts addressed here are not specific to 1 type of corporate system, size, or management level. Although the early business focus had been on upper‐level and executive talent within large corporate settings, there is an increasing recognition that a dedicated talent strategy is useful wherever recruiting and retaining talented people is important (and where is it not?).

The ideas presented here may seem most applicable to leaders of large physician corporations, hospital‐owned physician groups, or large integrated healthcare systems (such as Kaiser) that employ physicians. However, we also believe that the ideas apply across‐the‐board in medicine, including entities such as small, private, physician‐owned groups. We argue that regardless of the exact practice structure, a limited pool of resources must be dedicated to the attraction and retention of talented partners or employees, or to the cost of replacing those people if they pursue other opportunities (or the cost of inefficient and disengaged physicians). While an integrated health system may have the resources and scale to hire a Chief Experience Officer, we do not anticipate that a 5‐partner private practice would. Rather, we point to examples to illustrate the talent facilitation paradigm as a tool to systematically frame the allocation of those resources. Undoubtedly, the specific shape of a thoughtful talent facilitation effort will vary when applied in a large urban academic medical center vs. an integrated healthcare system vs. a small physician private practice, but the basic principles remain the same.

Attract

Increasingly, companies approach talented prospects with dedicated marketing campaigns to convey the value of a work environment.11 Silicon Valley employee lounges with free massages and foosball tables are the iconic example of attraction, but the concept runs deeper. Today's workers seek access to state‐of‐the‐art ideas and technology and often want to be part of a larger vision. Many seek opportunities to integrate their own professional and personal aspirations into a particular job description.

Hospital executives have long recognized the importance of attracting physicians to their facility (after all, the physicians draw patients and thus generate revenue). The traditional approach has surrounded perks, from comfortable doctor's lounges to the latest in surgical technology. But, the stakes seem greater now than before, and successful talent facilitation strategies are going beyond the tried and true.

Clearly, physicians seek financially stable practice settings with historical success. But they may also seek evidence of a defined strategic plan focused on more than mere profitability. Physicians may gravitate to practice environments that endorse progressive movements like the No One Dies Alone campaign.12 Similarly, recognition of movements beyond healthcarea commitment to Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) (Green Building Rating System; US Green Building Council [USGBC];

The current recruitment campaign of California's prison healthcare system offers an unlikely source of inspiration. The prison system was placed in receivership to address a shortage of competent physician staff and other inadequacies. A central feature of the campaign is an attractive starting salary and good benefits. But, the campaign does not rely on money alone. For example, the campaign's website (

Engage

The corporate tool being employed at this stage is a strategy called on‐boarding, which emphasizes a streamlined integration of newcomers with existing workers and culture, and prioritizes aligning organizational roles with a worker's specific skills and interests. On‐boarding also emphasizes the value of early and frequent provision of constructive feedback from same‐level peers or managers with advanced coaching skills.

Many companies use formal survey tools to measure employee engagement and regularly evaluate the proficiency of system leaders in the ability to engage their employees. An engineering firm executive recently told us (P.K., C.K.) that he performs detailed and frequent on‐the‐job interviews, even with company veterans. The primary goal of these interviews is to ensure that engineers spend at least 85% of their time on work that: (1) they find interesting and (2) allows for the application of their best skills. Wherever possible, traditional job descriptions are altered to achieve this. Inevitably, there is still work (15% in this particular corporate vision) that no one prefers but needs to get done, but this process of active recalibration minimizes this fraction to the degree possible.

Even within a small physician practice group, one can imagine how a strategic approach of inviting and acknowledging individual physician's professional goals and particular talents may challenge the long‐held belief that everyone within a group enjoys and must do the exact same job. Once these goals and talents are articulated, groups may find that allowing for more customized roles within the practice enhances professional satisfaction.

Social networking, collaboration, and sharing of best practices are staples of engaging companies. The Cisco and Qualcomm companies, for example, utilize elaborate e‐networks (rough corporate equivalents to Facebook) to foster collegial interaction within and across traditional hierarchical boundaries so that managers and executives directly engage the ideas of employees at every level.14 The premise is logical: engaged employees will be more likely to contribute innovative ideas which, when listened to, are more likely to engage employees.

Most physicians will recognize the traditional resident report as a model for engagement. Beyond its educational value, interaction with program leadership, social bonding, collaborative effort, and exploration of best practices add tremendous value. Many companies would jump at the chance to engrain a similar cultural staple. Enhancing this type of interaction in a postresidency setting may promote engagement in a given system, especially if it facilitates interactions between physicians and senior hospital leaders. Absent these types of interactions, ensuring regular provision of peer review and/or constructive feedback can help systematically enhance 2‐way communication and enhance engagement.

Develop

Talent development relies on mentorship reflecting a genuine interest in an individual's future. Development strategies include pairing formal annual talent reviews or (in the case of practice partners) formal peer review with strategic development plans. Effective development strategy may include transparent succession planning so that individuals are aware they are being groomed for future roles.

A well‐known adage suggests, People quit the manager or administrator, not the job. Development in this sense relies on presenting new opportunities and knowing that people flourish when allowed to explore multiple paths forward. In many companies, the role of Chief Experience or Chief Learning Officers is to enhance development planning. Consider how career coaching of young hospitalists could transform an infinitely portable and volatile commodity job, prone to burnout, into an engaged specialist of sorts with immense value to a hospital. Hospitalists have already demonstrated their potential as quality improvement leaders.15 Imagine if hospital leadership enlisted a young hospitalist in a relevant quality improvement task force, such as one working on preventing falls. With appropriate support, the physician could obtain skills for quality improvement evaluation that would not only enhance his or her engagement with the hospital system but also provide a valuable analysis for the hospital.

As an example of development strategy within a small practice setting, consider the following real‐life anecdote: a group of 4 physicians recently completed a long and expensive recruitment of a new partner. The new partner, intrigued by the local hospital's surgical robot technology, sought the support of her partners (who are not currently using the technology) to partake in an expensive robotics training program. The partners decided not to provide the financial support. The new partner subsequently left the group for a nearby practice opportunity that would provide for the training, and the group was faced with the loss of a partner (one‐fourth of the practice!) and the cost of repeating the recruiting process. A preemptive evaluation of the value of investing in the development of the new partner and enhancing that partner's professional development may have proven wise despite the significant up‐front costs. In this case the manager the new partner quit was the inflexibility of the practice trajectory.

Retain

The economic incentive to retain talented workers is not subtle. If it was, companies would not be funneling resources into Chief Experience Officers. Likewise, the estimated cost for a medical practice to replace an individual physician is as at least $250,000.16, 17

In retention, as in attraction, salary is only part of the equation.18 People want fair and competitive compensation, and may leave if they are not getting it, but they will not stay (and will not stay engaged) only for a salary bump. Retention is enhanced when workers can advance according to skills and talent, rather than mere tenure. An effective retention policy responds to people's desire to incorporate individual professional goals into their work and allows for people to customize their career rather than simply occupy a job class. Effective retention policy respects worklife balance and recognizes that this balance might look different for 2 people with the same job. It may take the form of positive reinforcement (rather than subtle disdain) for using vacation time or allowing for participation in international service projects. Many literally feel that they need to quit their job in order to take time off or explore other interests.

Worklife balance has been a longstanding issue in medicine, and innovative augmentation strategies may well help retain top talent. Today's successful medical school applicants not only show aptitude in the classroom, they often have many well‐developed nonmedical skills. No one can expect that medical training will somehow convince them to leave everything else behind. Moreover, today's residency graduates, already with Generation Y sensibilities, have completed their entire training under the auspices of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) duty hours regulations, which has made residents far more comfortable with shift work and defined hours.

At the other end of the generation spectrum, as large numbers of physicians ready for retirement, effective talent facilitation strategies may evaluate how to reoffer medicine as a valid option for senior physicians who still wish to work. Retaining these physicians will require an appreciation of their lifestyle goals, as they will likely find continuing a traditional practice role untenable. A recent survey of orthopedic surgeons 50 years of age or older found that having a part‐time option was a common reason they continued practicing, and that the option to work part‐time would have the most impact on keeping these surgeons working past age 65 years.19 Those working part‐time were doing so in a wide range of practice arrangements including private practice. However, one‐third of those surveyed said a part‐time option was not available to them. Clearly, in an environment of workforce shortages, physician‐leaders must begin to think about worklife balance not only for new doctors but for those considering retirement.

Critics will point out the financial drawbacks in the provision of worklife balance. But the cost may pale in comparison to the cost of replacing physician leaders. Moreover, engaged physicians are more likely to add value in the form of intangible capital such as patient satisfaction and practice innovation. As such, we argue that effective retention strategy in medicine is likely to be cost‐effective, even if it requires significant new up‐front resources.

Lessons From Industry

Doctors frequently assume that the challenges and obstacles confronted in healthcare are unique to medicine. But, for every phrase like When I started practice, I decided how long office visits were, not the insurance company, or Young doctors just don't want to work as hard, there is a parallel utterance in the greater business world. Luckily, there are now examples of the healthcare world learning lessons from business. For example, innovators in medical quality improvement found value in the experience of other industries.20 Airlines and automakers have long honed systems for error prevention and possess expertise that may curb errors in the hospital.2123

We suspect that the ideas and practice of talent facilitation have already made their way into some medical settings. A Google search reveals multiple opportunities for hospital‐based talent managers, and websites advertise the availability of talent consultants ready to lend their expertise to the medical world. In the arena of academic medicine, the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Division of Hospital Medicine put some of the ideas of talent facilitation into practice over the past year, in part in response to an increasingly competitive market for academic hospitalists.24 Leaders introduced a formal faculty development program that links junior faculty with mentors and facilitates early and frequent feedback across hierarchical boundaries.25 These more intentional mentoring efforts were accompanied by a seminar series aimed at the needs of new faculty members, a research incubator program, divisional grand rounds, and other web‐based and in‐person forums for sharing best practices and innovations. Less formal social events have also been promoted. Importantly, these sweeping strategies seek to encompass the needs of both teaching and nonteaching hospitalists within UCSF.26

Clearly, an academic hospitalist group with 45 faculty physicians has unique characteristics that inform the specifics of its talent facilitation strategy. The interventions discussed above are meant to represent examples of the types of strategies that may be utilized by physician groups once a decision is made to focus on talent management. Undoubtedly, the shape of such efforts will vary in diverse practice settings, but physician leaders have much to gain through further exploration of where these core principles already exist within medicine and where they may be more effectively deployed. By examining how multinational businesses are systematically applying the concepts of talent facilitation to address a global talent shortage, the doctoring profession might again take an outside hint to help inform its future.

The demand for physician talent is intensifying as the US healthcare system confronts an unprecedented confluence of demographic pressures. Not only will 78 million retiring baby‐boomers require significant healthcare resources, but tens of thousands of practicing physicians will themselves reach retirement age within the next decade.1 At the same time, factors like the large increase in the percentage of female physicians (who are more likely to work part time), the growth of nonpractice opportunities for MDs, and generational demands for greater worklife balance are creating a major supply‐demand mismatch within the physician workforce.2 In this demographic atmosphere, the ability to recruit and retain physician leaders confers tremendous value to healthcare enterprisesboth public and private. Recruiting and retaining strategies already weigh heavily in the most palpable shortage areas, like primary care, but the system faces widespread unmet demand for a variety of specialist and generalist practitioners.36

This article does not address the public policy implications of the upcoming physician shortage, recognition of which will lead to the largest increase in new medical school slots in decades.7 Rather, we set out to illustrate how successful nonmedical businesses are embracing a thoughtful, systematic approach to retaining talent, based on the philosophy that keeping and engaging valued employees is more efficient than recruiting and orienting replacements. We posit that the innovations used by progressive companies could apply to recruitment and retention challenges confronting medicine.

How Industry Approaches the Talent Vacuum: Talent Facilitation

Leaders outside of medicine have long acknowledged that changing demographics and a global economy are driving unprecedented employee turnover.8 In confronting a talent vacuum, forward‐thinking managers have prioritized retaining key talent (rather than hiring anew) in planning for the future.9, 10 Doing so begins with attempts to understand the relationship between workers and the workplace, with a particular emphasis on appreciating workers' priorities. Indeed, new executive positions with titles like Chief Learning Officer and Chief Experience Officer are appearing as companies realize a need for focused expertise beyond traditional human resource departments. These companies understand that offering higher salaries is not the only retention strategyand often not even the most effective one.

The Four Actions of Talent Facilitation

The talent facilitation process centers on four actions: attract, engage, develop, and retain. None of these actions can stand alone, and all should be present, to some degree, at all stages of a worker's tenure. To attract or engage an employee or practice partner is not a 1‐time hook, but a constant and dynamic process.

Importantly, the concepts addressed here are not specific to 1 type of corporate system, size, or management level. Although the early business focus had been on upper‐level and executive talent within large corporate settings, there is an increasing recognition that a dedicated talent strategy is useful wherever recruiting and retaining talented people is important (and where is it not?).

The ideas presented here may seem most applicable to leaders of large physician corporations, hospital‐owned physician groups, or large integrated healthcare systems (such as Kaiser) that employ physicians. However, we also believe that the ideas apply across‐the‐board in medicine, including entities such as small, private, physician‐owned groups. We argue that regardless of the exact practice structure, a limited pool of resources must be dedicated to the attraction and retention of talented partners or employees, or to the cost of replacing those people if they pursue other opportunities (or the cost of inefficient and disengaged physicians). While an integrated health system may have the resources and scale to hire a Chief Experience Officer, we do not anticipate that a 5‐partner private practice would. Rather, we point to examples to illustrate the talent facilitation paradigm as a tool to systematically frame the allocation of those resources. Undoubtedly, the specific shape of a thoughtful talent facilitation effort will vary when applied in a large urban academic medical center vs. an integrated healthcare system vs. a small physician private practice, but the basic principles remain the same.

Attract

Increasingly, companies approach talented prospects with dedicated marketing campaigns to convey the value of a work environment.11 Silicon Valley employee lounges with free massages and foosball tables are the iconic example of attraction, but the concept runs deeper. Today's workers seek access to state‐of‐the‐art ideas and technology and often want to be part of a larger vision. Many seek opportunities to integrate their own professional and personal aspirations into a particular job description.

Hospital executives have long recognized the importance of attracting physicians to their facility (after all, the physicians draw patients and thus generate revenue). The traditional approach has surrounded perks, from comfortable doctor's lounges to the latest in surgical technology. But, the stakes seem greater now than before, and successful talent facilitation strategies are going beyond the tried and true.

Clearly, physicians seek financially stable practice settings with historical success. But they may also seek evidence of a defined strategic plan focused on more than mere profitability. Physicians may gravitate to practice environments that endorse progressive movements like the No One Dies Alone campaign.12 Similarly, recognition of movements beyond healthcarea commitment to Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) (Green Building Rating System; US Green Building Council [USGBC];

The current recruitment campaign of California's prison healthcare system offers an unlikely source of inspiration. The prison system was placed in receivership to address a shortage of competent physician staff and other inadequacies. A central feature of the campaign is an attractive starting salary and good benefits. But, the campaign does not rely on money alone. For example, the campaign's website (

Engage

The corporate tool being employed at this stage is a strategy called on‐boarding, which emphasizes a streamlined integration of newcomers with existing workers and culture, and prioritizes aligning organizational roles with a worker's specific skills and interests. On‐boarding also emphasizes the value of early and frequent provision of constructive feedback from same‐level peers or managers with advanced coaching skills.

Many companies use formal survey tools to measure employee engagement and regularly evaluate the proficiency of system leaders in the ability to engage their employees. An engineering firm executive recently told us (P.K., C.K.) that he performs detailed and frequent on‐the‐job interviews, even with company veterans. The primary goal of these interviews is to ensure that engineers spend at least 85% of their time on work that: (1) they find interesting and (2) allows for the application of their best skills. Wherever possible, traditional job descriptions are altered to achieve this. Inevitably, there is still work (15% in this particular corporate vision) that no one prefers but needs to get done, but this process of active recalibration minimizes this fraction to the degree possible.

Even within a small physician practice group, one can imagine how a strategic approach of inviting and acknowledging individual physician's professional goals and particular talents may challenge the long‐held belief that everyone within a group enjoys and must do the exact same job. Once these goals and talents are articulated, groups may find that allowing for more customized roles within the practice enhances professional satisfaction.

Social networking, collaboration, and sharing of best practices are staples of engaging companies. The Cisco and Qualcomm companies, for example, utilize elaborate e‐networks (rough corporate equivalents to Facebook) to foster collegial interaction within and across traditional hierarchical boundaries so that managers and executives directly engage the ideas of employees at every level.14 The premise is logical: engaged employees will be more likely to contribute innovative ideas which, when listened to, are more likely to engage employees.

Most physicians will recognize the traditional resident report as a model for engagement. Beyond its educational value, interaction with program leadership, social bonding, collaborative effort, and exploration of best practices add tremendous value. Many companies would jump at the chance to engrain a similar cultural staple. Enhancing this type of interaction in a postresidency setting may promote engagement in a given system, especially if it facilitates interactions between physicians and senior hospital leaders. Absent these types of interactions, ensuring regular provision of peer review and/or constructive feedback can help systematically enhance 2‐way communication and enhance engagement.

Develop

Talent development relies on mentorship reflecting a genuine interest in an individual's future. Development strategies include pairing formal annual talent reviews or (in the case of practice partners) formal peer review with strategic development plans. Effective development strategy may include transparent succession planning so that individuals are aware they are being groomed for future roles.

A well‐known adage suggests, People quit the manager or administrator, not the job. Development in this sense relies on presenting new opportunities and knowing that people flourish when allowed to explore multiple paths forward. In many companies, the role of Chief Experience or Chief Learning Officers is to enhance development planning. Consider how career coaching of young hospitalists could transform an infinitely portable and volatile commodity job, prone to burnout, into an engaged specialist of sorts with immense value to a hospital. Hospitalists have already demonstrated their potential as quality improvement leaders.15 Imagine if hospital leadership enlisted a young hospitalist in a relevant quality improvement task force, such as one working on preventing falls. With appropriate support, the physician could obtain skills for quality improvement evaluation that would not only enhance his or her engagement with the hospital system but also provide a valuable analysis for the hospital.

As an example of development strategy within a small practice setting, consider the following real‐life anecdote: a group of 4 physicians recently completed a long and expensive recruitment of a new partner. The new partner, intrigued by the local hospital's surgical robot technology, sought the support of her partners (who are not currently using the technology) to partake in an expensive robotics training program. The partners decided not to provide the financial support. The new partner subsequently left the group for a nearby practice opportunity that would provide for the training, and the group was faced with the loss of a partner (one‐fourth of the practice!) and the cost of repeating the recruiting process. A preemptive evaluation of the value of investing in the development of the new partner and enhancing that partner's professional development may have proven wise despite the significant up‐front costs. In this case the manager the new partner quit was the inflexibility of the practice trajectory.

Retain

The economic incentive to retain talented workers is not subtle. If it was, companies would not be funneling resources into Chief Experience Officers. Likewise, the estimated cost for a medical practice to replace an individual physician is as at least $250,000.16, 17

In retention, as in attraction, salary is only part of the equation.18 People want fair and competitive compensation, and may leave if they are not getting it, but they will not stay (and will not stay engaged) only for a salary bump. Retention is enhanced when workers can advance according to skills and talent, rather than mere tenure. An effective retention policy responds to people's desire to incorporate individual professional goals into their work and allows for people to customize their career rather than simply occupy a job class. Effective retention policy respects worklife balance and recognizes that this balance might look different for 2 people with the same job. It may take the form of positive reinforcement (rather than subtle disdain) for using vacation time or allowing for participation in international service projects. Many literally feel that they need to quit their job in order to take time off or explore other interests.

Worklife balance has been a longstanding issue in medicine, and innovative augmentation strategies may well help retain top talent. Today's successful medical school applicants not only show aptitude in the classroom, they often have many well‐developed nonmedical skills. No one can expect that medical training will somehow convince them to leave everything else behind. Moreover, today's residency graduates, already with Generation Y sensibilities, have completed their entire training under the auspices of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) duty hours regulations, which has made residents far more comfortable with shift work and defined hours.

At the other end of the generation spectrum, as large numbers of physicians ready for retirement, effective talent facilitation strategies may evaluate how to reoffer medicine as a valid option for senior physicians who still wish to work. Retaining these physicians will require an appreciation of their lifestyle goals, as they will likely find continuing a traditional practice role untenable. A recent survey of orthopedic surgeons 50 years of age or older found that having a part‐time option was a common reason they continued practicing, and that the option to work part‐time would have the most impact on keeping these surgeons working past age 65 years.19 Those working part‐time were doing so in a wide range of practice arrangements including private practice. However, one‐third of those surveyed said a part‐time option was not available to them. Clearly, in an environment of workforce shortages, physician‐leaders must begin to think about worklife balance not only for new doctors but for those considering retirement.

Critics will point out the financial drawbacks in the provision of worklife balance. But the cost may pale in comparison to the cost of replacing physician leaders. Moreover, engaged physicians are more likely to add value in the form of intangible capital such as patient satisfaction and practice innovation. As such, we argue that effective retention strategy in medicine is likely to be cost‐effective, even if it requires significant new up‐front resources.

Lessons From Industry

Doctors frequently assume that the challenges and obstacles confronted in healthcare are unique to medicine. But, for every phrase like When I started practice, I decided how long office visits were, not the insurance company, or Young doctors just don't want to work as hard, there is a parallel utterance in the greater business world. Luckily, there are now examples of the healthcare world learning lessons from business. For example, innovators in medical quality improvement found value in the experience of other industries.20 Airlines and automakers have long honed systems for error prevention and possess expertise that may curb errors in the hospital.2123

We suspect that the ideas and practice of talent facilitation have already made their way into some medical settings. A Google search reveals multiple opportunities for hospital‐based talent managers, and websites advertise the availability of talent consultants ready to lend their expertise to the medical world. In the arena of academic medicine, the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Division of Hospital Medicine put some of the ideas of talent facilitation into practice over the past year, in part in response to an increasingly competitive market for academic hospitalists.24 Leaders introduced a formal faculty development program that links junior faculty with mentors and facilitates early and frequent feedback across hierarchical boundaries.25 These more intentional mentoring efforts were accompanied by a seminar series aimed at the needs of new faculty members, a research incubator program, divisional grand rounds, and other web‐based and in‐person forums for sharing best practices and innovations. Less formal social events have also been promoted. Importantly, these sweeping strategies seek to encompass the needs of both teaching and nonteaching hospitalists within UCSF.26

Clearly, an academic hospitalist group with 45 faculty physicians has unique characteristics that inform the specifics of its talent facilitation strategy. The interventions discussed above are meant to represent examples of the types of strategies that may be utilized by physician groups once a decision is made to focus on talent management. Undoubtedly, the shape of such efforts will vary in diverse practice settings, but physician leaders have much to gain through further exploration of where these core principles already exist within medicine and where they may be more effectively deployed. By examining how multinational businesses are systematically applying the concepts of talent facilitation to address a global talent shortage, the doctoring profession might again take an outside hint to help inform its future.

- Long Term Care: Aging Baby Boom Generation Will Increase Demand and Burden on Federal and State Budgets. United States General Accounting Office Testimony before the Special Committee on Aging, US Senate. Hearing Before the Special Committee on Aging of the US Senate,2002. Available at:http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d02544t.pdf. Accessed July 2009.

- ,.Physician workforce shortages: implications and issues for academic health centers and policymakers.Acad Med.2006;81(9):782–787.

- .New York moves to tackle shortage of primary‐care doctors.Lancet.2008;371(9615):801–802.

- ,.The US dermatology workforce: a specialty remains in shortage.J Am Acad Dermatol.2008;59(5):741–745.

- ,.Challenges and opportunities for recruiting a new generation of neurosurgeons.Neurosurgery.2007;61(6):1314–1319.

- ,.The developing crisis in the national general surgery workforce.J Am Coll Surg.2008;206(5):790–795.

- Medical School Enrollment Plans: Analysis of the 2007 AAMC Survey. Publication of the Association of American Medical Colleges, Center for Workforce Studies, April2008. Available at:http://www.aamc.org/workforce. Accessed July 2009.

- It's 2008: Do You Know Where Your Talent Is? Why acquisition and retention strategies don't work. Part 1 of a Deloitte Research Series on Talent Management.2008. Available at: http://www.deloitte.com/dtt/cda/content/UKConsulting_TalentMgtResearchReport.pdf. Accessed August 2009.

- ,,.The race for talent: retaining and engaging workers in the 21st century.Hum Resour Plann.2004;27(3):12–25.

- Expecting sales growth, CEOs cite worker retention as critical to success. March 1,2004. Available at:http://www.barometersurveys.com/production/barsurv.nsf/89343582e94adb6185256b84006c8ffe/9672ab2f54cf99f885256e5500768232?OpenDocument. Accessed July 2009.

- Jet Blue announces aviation university gateway program for pilot candidates: airline partners with Embry‐Riddle Aeronautical University, University of North Dakota, and Cape Air to fill pilot pipeline. January 30, 2008. Available at:http://investor.jetblue.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=131045287(4):487–494.

- ,,.A review of physician turnover: rates, causes, and consequences.Am J Med Qual.2004;19(2):56–66.

- ,,.The impact on revenue of physician turnover: an assessment model and experience in a large healthcare center.J Med Pract Manage.2006;21(6):351–355.

- ,,.Employee motivation: a powerful new model.Harv Bus Rev.2008;86(7–8):78,84,160.

- ,,.Work satisfaction and retirement plans of orthopaedic surgeons 50 years of age or older.Clin Orthop Relat Res.2008;466(1):231–238.

- ,,,.The long road to patient safety: a status report on patient safety systems.JAMA.2005(22);294:2858–2865.

- .Error reduction through team leadership: what surgeons can learn from the airline industry.Clin Neurosurg.2007;54:195–199.

- ,.Applying the Toyota production system: using a patient safety alert system to reduce error.Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf.2007;33(7):376–386.

- ,,,.Improving Papanikolaou test quality and reducing medical errors by using Toyota production system methods.Am J Obstet Gynecol.2006;194(1):57–64.

- Society of Hospital Medicine Career Satisfaction Task Force. White Paper on Hospitalist Career Satisfaction.2006; 1–45. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org. Accessed July 2009.

- UCSF Department of Medicine, Division of Hospital Medicine, Faculty Development. Available at: http://hospsrvr.ucsf.edu/cme/fds.html. Accessed July 2009.

- ,,, et al. Non‐housestaff medicine services in academic centers: models and challenges.J Hosp Med.2008;3(3):247–245.

- Long Term Care: Aging Baby Boom Generation Will Increase Demand and Burden on Federal and State Budgets. United States General Accounting Office Testimony before the Special Committee on Aging, US Senate. Hearing Before the Special Committee on Aging of the US Senate,2002. Available at:http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d02544t.pdf. Accessed July 2009.

- ,.Physician workforce shortages: implications and issues for academic health centers and policymakers.Acad Med.2006;81(9):782–787.

- .New York moves to tackle shortage of primary‐care doctors.Lancet.2008;371(9615):801–802.

- ,.The US dermatology workforce: a specialty remains in shortage.J Am Acad Dermatol.2008;59(5):741–745.

- ,.Challenges and opportunities for recruiting a new generation of neurosurgeons.Neurosurgery.2007;61(6):1314–1319.

- ,.The developing crisis in the national general surgery workforce.J Am Coll Surg.2008;206(5):790–795.

- Medical School Enrollment Plans: Analysis of the 2007 AAMC Survey. Publication of the Association of American Medical Colleges, Center for Workforce Studies, April2008. Available at:http://www.aamc.org/workforce. Accessed July 2009.

- It's 2008: Do You Know Where Your Talent Is? Why acquisition and retention strategies don't work. Part 1 of a Deloitte Research Series on Talent Management.2008. Available at: http://www.deloitte.com/dtt/cda/content/UKConsulting_TalentMgtResearchReport.pdf. Accessed August 2009.

- ,,.The race for talent: retaining and engaging workers in the 21st century.Hum Resour Plann.2004;27(3):12–25.

- Expecting sales growth, CEOs cite worker retention as critical to success. March 1,2004. Available at:http://www.barometersurveys.com/production/barsurv.nsf/89343582e94adb6185256b84006c8ffe/9672ab2f54cf99f885256e5500768232?OpenDocument. Accessed July 2009.

- Jet Blue announces aviation university gateway program for pilot candidates: airline partners with Embry‐Riddle Aeronautical University, University of North Dakota, and Cape Air to fill pilot pipeline. January 30, 2008. Available at:http://investor.jetblue.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=131045287(4):487–494.

- ,,.A review of physician turnover: rates, causes, and consequences.Am J Med Qual.2004;19(2):56–66.

- ,,.The impact on revenue of physician turnover: an assessment model and experience in a large healthcare center.J Med Pract Manage.2006;21(6):351–355.

- ,,.Employee motivation: a powerful new model.Harv Bus Rev.2008;86(7–8):78,84,160.

- ,,.Work satisfaction and retirement plans of orthopaedic surgeons 50 years of age or older.Clin Orthop Relat Res.2008;466(1):231–238.

- ,,,.The long road to patient safety: a status report on patient safety systems.JAMA.2005(22);294:2858–2865.

- .Error reduction through team leadership: what surgeons can learn from the airline industry.Clin Neurosurg.2007;54:195–199.

- ,.Applying the Toyota production system: using a patient safety alert system to reduce error.Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf.2007;33(7):376–386.

- ,,,.Improving Papanikolaou test quality and reducing medical errors by using Toyota production system methods.Am J Obstet Gynecol.2006;194(1):57–64.

- Society of Hospital Medicine Career Satisfaction Task Force. White Paper on Hospitalist Career Satisfaction.2006; 1–45. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org. Accessed July 2009.

- UCSF Department of Medicine, Division of Hospital Medicine, Faculty Development. Available at: http://hospsrvr.ucsf.edu/cme/fds.html. Accessed July 2009.

- ,,, et al. Non‐housestaff medicine services in academic centers: models and challenges.J Hosp Med.2008;3(3):247–245.