User login

Now Available: The 2017 JHM Core Competencies Compendium.

Want all 52 Core Competency articles in an easy-to-read compendium? Order your copy now from Amazon.com.

Want all 52 Core Competency articles in an easy-to-read compendium? Order your copy now from Amazon.com.

Want all 52 Core Competency articles in an easy-to-read compendium? Order your copy now from Amazon.com.

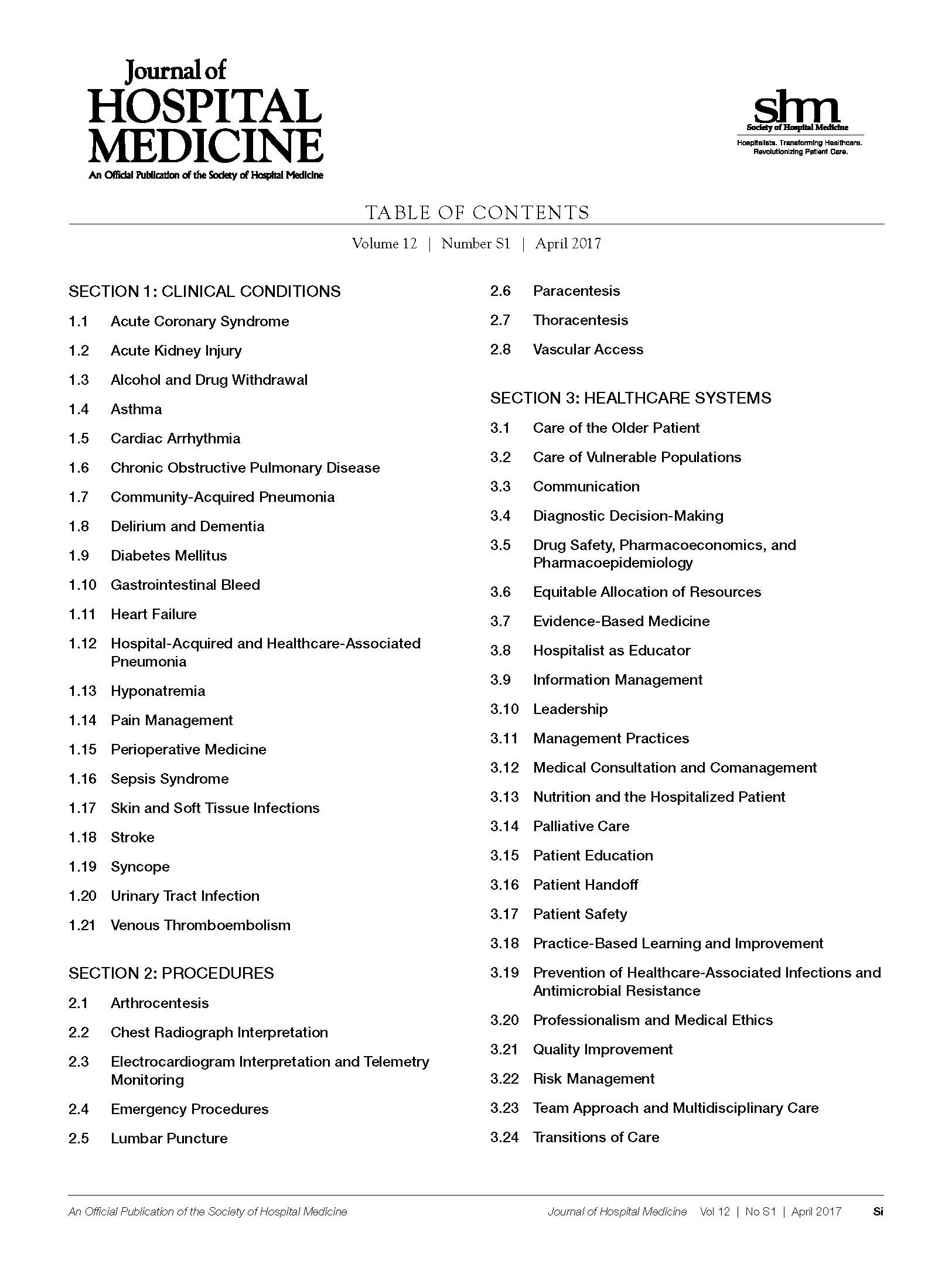

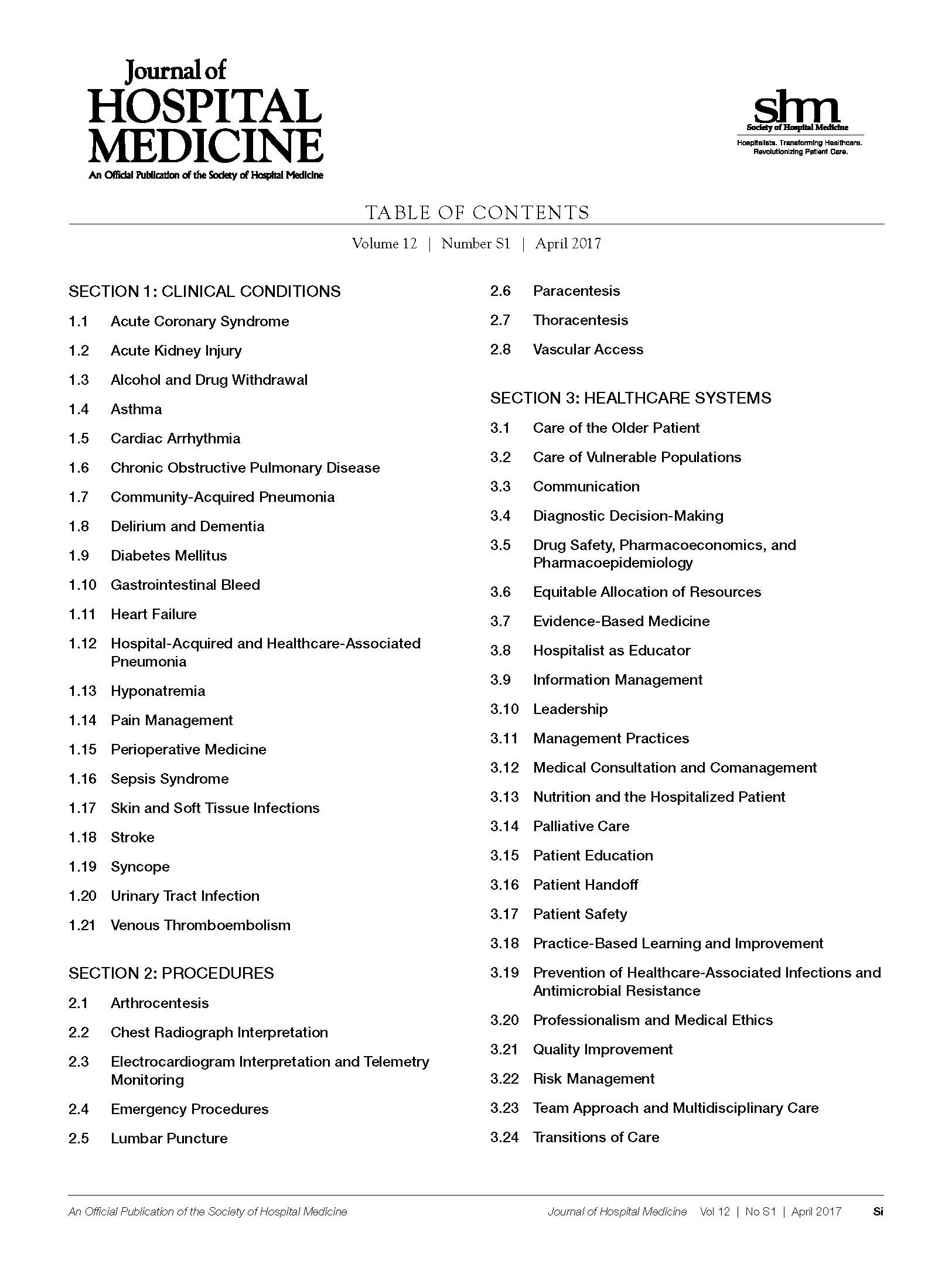

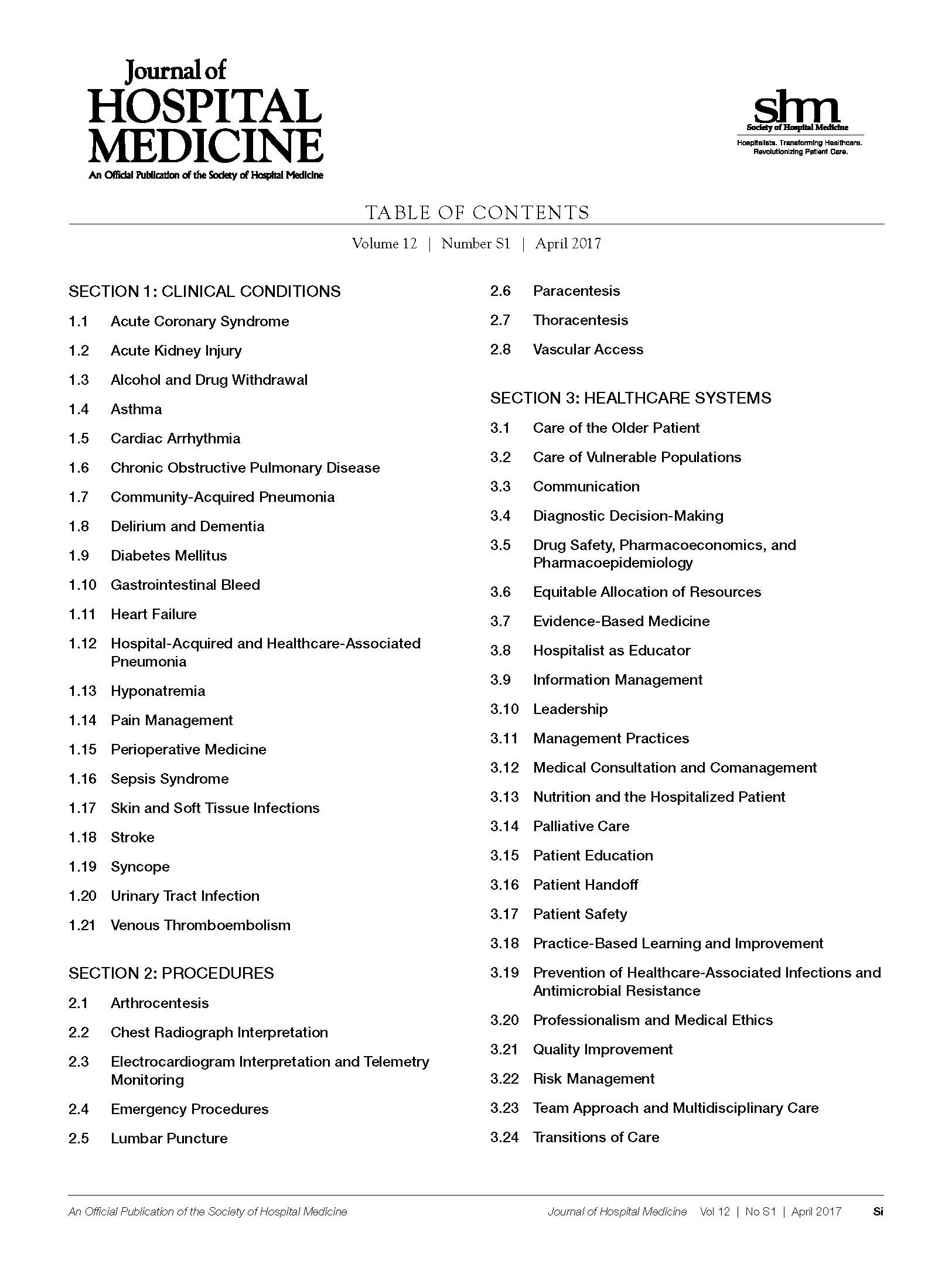

The 2017 JHM Core Competencies Table of Contents.

Want all 52 JHM Core Competency articles in an easy-to-read compendium? Order your copy now from Amazon.com.

Want all 52 JHM Core Competency articles in an easy-to-read compendium? Order your copy now from Amazon.com.

Want all 52 JHM Core Competency articles in an easy-to-read compendium? Order your copy now from Amazon.com.

Acute Kidney Injury. 2017 Hospital Medicine Revised Core Competencies

Acute kidney injury (AKI), also known as acute renal failure (ARF), is a decline in renal function over a period of hours or days that results in the accumulation of nitrogenous waste products and an impaired ability to maintain fluid/electrolyte/acid-base homeostasis. Epidemiologic studies of AKI are confounded by inconsistent definitions and underreporting. The average incidence is estimated to be 23.8 cases per 1000 hospital discharges.1Approximately 5% to 20% of critically ill patients experience AKI during the course of their illness.2 AKI may present in isolation, develop as a complication of other comorbid illness, or result as a deleterious adverse effect of treatment or diagnostic interventions. Uncomplicated AKI is associated with a mortality rate of up to 10%.3-6 Patients with AKI and multiorgan failure have mortality rates higher than 50%.3-6 AKI is associated with an increased length of hospital stay; a rise in serum creatinine of 0.5 mg/dL or greater while hospitalized confers a 3.5-day increase in length of stay.7 Hospitalists facilitate the expeditious evaluation and management of AKI to improve patient outcomes, optimize resource use, and reduce length of stay. Hospitalists can also advocate and initiate preventive strategies to reduce the incidence of secondary AKI.

KNOWLEDGE

Hospitalists should be able to:

Describe the symptoms and signs of AKI.

Describe and differentiate pathophysiologic causes of AKI including prerenal, intrinsic renal, and postrenal processes.

Differentiate among the causes of prerenal, intrinsic renal, and postrenal types of AKI.

Describe a logical sequence of indicated tests required to evaluate etiologies of AKI based on classification of AKI type.

List common potentially nephrotoxic agents that can cause or worsen AKI.

Explain the indications, contraindications, and mechanisms of action of the interventions used to treat AKI.

Explain the indications, contraindications, benefits, and risks of acute hemodialysis.

Recognize indications for specialty consultation for AKI and the role of nephrology and/or urology specialists.

Describe criteria, including specific measures of clinical stability, that must be met before discharging patients with AKI.

Explain the specific goals that should be met to ensure safe transitions of care for patients with AKI.

SKILLS

Hospitalists should be able to:

Assess patients with suspected AKI in a timely manner and manage or comanage the patient with the primary requesting service.

Elicit a thorough and relevant medical history with emphasis on factors predisposing or contributing to the development of AKI.

Review all drug use including prescription and over-the-counter medications, herbal remedies, nutritional supplements, and illicit drugs to identify common potential nephrotoxins.

Perform a physical examination to assess volume status and to identify underlying comorbid states that may predispose to the development of AKI.

Order and interpret results of indicated diagnostic studies that may include urinalysis and microscopic sediment analysis, urinary diagnostic indices, urinary protein excretion, serologic evaluation, and renal imaging.

Interpret common clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings used to evaluate and follow the severity of AKI.

Diagnose common complications, such as electrolyte abnormalities, that occur with AKI and institute corrective measures.

Calculate estimated creatinine clearance for medication dosage adjustments when indicated.

Identify patients at risk for developing AKI and institute appropriate preventive measures including avoidance of unnecessary radiographic contrast exposure and adherence to evidence-based interventions to reduce the risk of contrast-induced nephropathy.

Coordinate appropriate nutritional and metabolic interventions.

Formulate an AKI treatment plan tailored to the individual patient, which may include fluid management, pharmacologic agents, nutritional recommendations, and patient education.

Identify and treat factors that may complicate the management of AKI, including extreme blood pressure, underlying infections, and the sequelae of electrolyte abnormalities.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the cause and prognosis of AKI.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the rationale for the use of radiographic tests and procedures and the benefit and potential adverse effects of radiographic contrast agents.

Facilitate discharge planning early during hospitalization.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the goals of care, discharge instructions, and management after hospital discharge to ensure safe follow-up and transitions of care.

Document the treatment plan and provide clear discharge instructions for postdischarge clinicians.

ATTITUDES

Hospitalists should be able to:

Employ a multidisciplinary approach, which may include nursing, nutrition, and pharmacy services, in the care of patients with AKI that begins at admission and continues through all care transitions.

Follow evidence-based recommendations, protocols, and risk-stratification tools for the treatment of AKI.

SYSTEM ORGANIZATION AND IMPROVEMENT

To improve efficiency and quality within their organizations, hospitalists should:

Advocate for, establish, and support initiatives to reduce the incidence of iatrogenic AKI.

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in multidisciplinary teams (including nephrology, nursing, pharmacy, and nutrition services) to improve processes that facilitate early identification of AKI and improved patient outcomes.

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in multidisciplinary initiatives to promote patient safety and optimize management strategies for AKI.

1. Xue JL, Daniels F, Star RA, Kimmel PL, Eggers PW, Molitoris BA, et al. Incidence and mortality of acute renal failure in Medicare beneficiaries, 1992-2001. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(4):1135-1142.

2. Metnitz PG, Krenn CG, Steltzer H, Lang T, Ploder J, Lenz K, et al. Effect of acute renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy on outcome in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(9):2051-2058.

3. Cosentino F, Chaff C, Piedmonte M. Risk factors influencing survival in ICU acute renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1994;9(Suppl 4):179-182.

4. Hou SH, Bushinsky DA, Wish JB, Cohen JJ, Harrington JT. Hospital-acquired renal insufficiency: a prospective study. Am H Med. 1983;74(2):243-248.

5. Liano F, Junco E, Pascual J, Madero R, Verde E. The spectrum of acute renal failure in the intensive care unit compared with that seen in other settings. The Madrid Acute Renal Failure Study Group. Kidney Int Suppl. 1998;66:S16-S24.

6. Shusterman N, Strom BL, Murray TG, Morrison G, West SL, Maislin G. Risk factors and outcome of hospital-acquired acute renal failure. Clinical epidemiologic study. Am J Med. 1987;83(1):65-71.

7. Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, Bonventre JV, Bates DW. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(11):3365-3370.

Acute kidney injury (AKI), also known as acute renal failure (ARF), is a decline in renal function over a period of hours or days that results in the accumulation of nitrogenous waste products and an impaired ability to maintain fluid/electrolyte/acid-base homeostasis. Epidemiologic studies of AKI are confounded by inconsistent definitions and underreporting. The average incidence is estimated to be 23.8 cases per 1000 hospital discharges.1Approximately 5% to 20% of critically ill patients experience AKI during the course of their illness.2 AKI may present in isolation, develop as a complication of other comorbid illness, or result as a deleterious adverse effect of treatment or diagnostic interventions. Uncomplicated AKI is associated with a mortality rate of up to 10%.3-6 Patients with AKI and multiorgan failure have mortality rates higher than 50%.3-6 AKI is associated with an increased length of hospital stay; a rise in serum creatinine of 0.5 mg/dL or greater while hospitalized confers a 3.5-day increase in length of stay.7 Hospitalists facilitate the expeditious evaluation and management of AKI to improve patient outcomes, optimize resource use, and reduce length of stay. Hospitalists can also advocate and initiate preventive strategies to reduce the incidence of secondary AKI.

KNOWLEDGE

Hospitalists should be able to:

Describe the symptoms and signs of AKI.

Describe and differentiate pathophysiologic causes of AKI including prerenal, intrinsic renal, and postrenal processes.

Differentiate among the causes of prerenal, intrinsic renal, and postrenal types of AKI.

Describe a logical sequence of indicated tests required to evaluate etiologies of AKI based on classification of AKI type.

List common potentially nephrotoxic agents that can cause or worsen AKI.

Explain the indications, contraindications, and mechanisms of action of the interventions used to treat AKI.

Explain the indications, contraindications, benefits, and risks of acute hemodialysis.

Recognize indications for specialty consultation for AKI and the role of nephrology and/or urology specialists.

Describe criteria, including specific measures of clinical stability, that must be met before discharging patients with AKI.

Explain the specific goals that should be met to ensure safe transitions of care for patients with AKI.

SKILLS

Hospitalists should be able to:

Assess patients with suspected AKI in a timely manner and manage or comanage the patient with the primary requesting service.

Elicit a thorough and relevant medical history with emphasis on factors predisposing or contributing to the development of AKI.

Review all drug use including prescription and over-the-counter medications, herbal remedies, nutritional supplements, and illicit drugs to identify common potential nephrotoxins.

Perform a physical examination to assess volume status and to identify underlying comorbid states that may predispose to the development of AKI.

Order and interpret results of indicated diagnostic studies that may include urinalysis and microscopic sediment analysis, urinary diagnostic indices, urinary protein excretion, serologic evaluation, and renal imaging.

Interpret common clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings used to evaluate and follow the severity of AKI.

Diagnose common complications, such as electrolyte abnormalities, that occur with AKI and institute corrective measures.

Calculate estimated creatinine clearance for medication dosage adjustments when indicated.

Identify patients at risk for developing AKI and institute appropriate preventive measures including avoidance of unnecessary radiographic contrast exposure and adherence to evidence-based interventions to reduce the risk of contrast-induced nephropathy.

Coordinate appropriate nutritional and metabolic interventions.

Formulate an AKI treatment plan tailored to the individual patient, which may include fluid management, pharmacologic agents, nutritional recommendations, and patient education.

Identify and treat factors that may complicate the management of AKI, including extreme blood pressure, underlying infections, and the sequelae of electrolyte abnormalities.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the cause and prognosis of AKI.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the rationale for the use of radiographic tests and procedures and the benefit and potential adverse effects of radiographic contrast agents.

Facilitate discharge planning early during hospitalization.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the goals of care, discharge instructions, and management after hospital discharge to ensure safe follow-up and transitions of care.

Document the treatment plan and provide clear discharge instructions for postdischarge clinicians.

ATTITUDES

Hospitalists should be able to:

Employ a multidisciplinary approach, which may include nursing, nutrition, and pharmacy services, in the care of patients with AKI that begins at admission and continues through all care transitions.

Follow evidence-based recommendations, protocols, and risk-stratification tools for the treatment of AKI.

SYSTEM ORGANIZATION AND IMPROVEMENT

To improve efficiency and quality within their organizations, hospitalists should:

Advocate for, establish, and support initiatives to reduce the incidence of iatrogenic AKI.

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in multidisciplinary teams (including nephrology, nursing, pharmacy, and nutrition services) to improve processes that facilitate early identification of AKI and improved patient outcomes.

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in multidisciplinary initiatives to promote patient safety and optimize management strategies for AKI.

Acute kidney injury (AKI), also known as acute renal failure (ARF), is a decline in renal function over a period of hours or days that results in the accumulation of nitrogenous waste products and an impaired ability to maintain fluid/electrolyte/acid-base homeostasis. Epidemiologic studies of AKI are confounded by inconsistent definitions and underreporting. The average incidence is estimated to be 23.8 cases per 1000 hospital discharges.1Approximately 5% to 20% of critically ill patients experience AKI during the course of their illness.2 AKI may present in isolation, develop as a complication of other comorbid illness, or result as a deleterious adverse effect of treatment or diagnostic interventions. Uncomplicated AKI is associated with a mortality rate of up to 10%.3-6 Patients with AKI and multiorgan failure have mortality rates higher than 50%.3-6 AKI is associated with an increased length of hospital stay; a rise in serum creatinine of 0.5 mg/dL or greater while hospitalized confers a 3.5-day increase in length of stay.7 Hospitalists facilitate the expeditious evaluation and management of AKI to improve patient outcomes, optimize resource use, and reduce length of stay. Hospitalists can also advocate and initiate preventive strategies to reduce the incidence of secondary AKI.

KNOWLEDGE

Hospitalists should be able to:

Describe the symptoms and signs of AKI.

Describe and differentiate pathophysiologic causes of AKI including prerenal, intrinsic renal, and postrenal processes.

Differentiate among the causes of prerenal, intrinsic renal, and postrenal types of AKI.

Describe a logical sequence of indicated tests required to evaluate etiologies of AKI based on classification of AKI type.

List common potentially nephrotoxic agents that can cause or worsen AKI.

Explain the indications, contraindications, and mechanisms of action of the interventions used to treat AKI.

Explain the indications, contraindications, benefits, and risks of acute hemodialysis.

Recognize indications for specialty consultation for AKI and the role of nephrology and/or urology specialists.

Describe criteria, including specific measures of clinical stability, that must be met before discharging patients with AKI.

Explain the specific goals that should be met to ensure safe transitions of care for patients with AKI.

SKILLS

Hospitalists should be able to:

Assess patients with suspected AKI in a timely manner and manage or comanage the patient with the primary requesting service.

Elicit a thorough and relevant medical history with emphasis on factors predisposing or contributing to the development of AKI.

Review all drug use including prescription and over-the-counter medications, herbal remedies, nutritional supplements, and illicit drugs to identify common potential nephrotoxins.

Perform a physical examination to assess volume status and to identify underlying comorbid states that may predispose to the development of AKI.

Order and interpret results of indicated diagnostic studies that may include urinalysis and microscopic sediment analysis, urinary diagnostic indices, urinary protein excretion, serologic evaluation, and renal imaging.

Interpret common clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings used to evaluate and follow the severity of AKI.

Diagnose common complications, such as electrolyte abnormalities, that occur with AKI and institute corrective measures.

Calculate estimated creatinine clearance for medication dosage adjustments when indicated.

Identify patients at risk for developing AKI and institute appropriate preventive measures including avoidance of unnecessary radiographic contrast exposure and adherence to evidence-based interventions to reduce the risk of contrast-induced nephropathy.

Coordinate appropriate nutritional and metabolic interventions.

Formulate an AKI treatment plan tailored to the individual patient, which may include fluid management, pharmacologic agents, nutritional recommendations, and patient education.

Identify and treat factors that may complicate the management of AKI, including extreme blood pressure, underlying infections, and the sequelae of electrolyte abnormalities.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the cause and prognosis of AKI.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the rationale for the use of radiographic tests and procedures and the benefit and potential adverse effects of radiographic contrast agents.

Facilitate discharge planning early during hospitalization.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the goals of care, discharge instructions, and management after hospital discharge to ensure safe follow-up and transitions of care.

Document the treatment plan and provide clear discharge instructions for postdischarge clinicians.

ATTITUDES

Hospitalists should be able to:

Employ a multidisciplinary approach, which may include nursing, nutrition, and pharmacy services, in the care of patients with AKI that begins at admission and continues through all care transitions.

Follow evidence-based recommendations, protocols, and risk-stratification tools for the treatment of AKI.

SYSTEM ORGANIZATION AND IMPROVEMENT

To improve efficiency and quality within their organizations, hospitalists should:

Advocate for, establish, and support initiatives to reduce the incidence of iatrogenic AKI.

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in multidisciplinary teams (including nephrology, nursing, pharmacy, and nutrition services) to improve processes that facilitate early identification of AKI and improved patient outcomes.

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in multidisciplinary initiatives to promote patient safety and optimize management strategies for AKI.

1. Xue JL, Daniels F, Star RA, Kimmel PL, Eggers PW, Molitoris BA, et al. Incidence and mortality of acute renal failure in Medicare beneficiaries, 1992-2001. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(4):1135-1142.

2. Metnitz PG, Krenn CG, Steltzer H, Lang T, Ploder J, Lenz K, et al. Effect of acute renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy on outcome in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(9):2051-2058.

3. Cosentino F, Chaff C, Piedmonte M. Risk factors influencing survival in ICU acute renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1994;9(Suppl 4):179-182.

4. Hou SH, Bushinsky DA, Wish JB, Cohen JJ, Harrington JT. Hospital-acquired renal insufficiency: a prospective study. Am H Med. 1983;74(2):243-248.

5. Liano F, Junco E, Pascual J, Madero R, Verde E. The spectrum of acute renal failure in the intensive care unit compared with that seen in other settings. The Madrid Acute Renal Failure Study Group. Kidney Int Suppl. 1998;66:S16-S24.

6. Shusterman N, Strom BL, Murray TG, Morrison G, West SL, Maislin G. Risk factors and outcome of hospital-acquired acute renal failure. Clinical epidemiologic study. Am J Med. 1987;83(1):65-71.

7. Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, Bonventre JV, Bates DW. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(11):3365-3370.

1. Xue JL, Daniels F, Star RA, Kimmel PL, Eggers PW, Molitoris BA, et al. Incidence and mortality of acute renal failure in Medicare beneficiaries, 1992-2001. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(4):1135-1142.

2. Metnitz PG, Krenn CG, Steltzer H, Lang T, Ploder J, Lenz K, et al. Effect of acute renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy on outcome in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(9):2051-2058.

3. Cosentino F, Chaff C, Piedmonte M. Risk factors influencing survival in ICU acute renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1994;9(Suppl 4):179-182.

4. Hou SH, Bushinsky DA, Wish JB, Cohen JJ, Harrington JT. Hospital-acquired renal insufficiency: a prospective study. Am H Med. 1983;74(2):243-248.

5. Liano F, Junco E, Pascual J, Madero R, Verde E. The spectrum of acute renal failure in the intensive care unit compared with that seen in other settings. The Madrid Acute Renal Failure Study Group. Kidney Int Suppl. 1998;66:S16-S24.

6. Shusterman N, Strom BL, Murray TG, Morrison G, West SL, Maislin G. Risk factors and outcome of hospital-acquired acute renal failure. Clinical epidemiologic study. Am J Med. 1987;83(1):65-71.

7. Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, Bonventre JV, Bates DW. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(11):3365-3370.

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Alcohol and Drug Withdrawal. 2017 Hospital Medicine Revised Core Competencies

Alcohol and drug withdrawal is a set of signs and symptoms that develops in association with sudden cessation or reduction in the use of alcohol or a number of prescription (particularly opioids and benzodiazepines), over-the-counter (OTC), or illicit drugs. Withdrawal syndromes encompass a broad range of symptoms from mild anxiety and tremulousness to more serious manifestations such as delirium tremens, which occurs in up to 5% of alcohol-dependent persons who undergo withdrawal.1 Withdrawal may occur before hospitalization or during the course of hospitalization. Alcohol- and substance-related disorders account for more than 400,000 hospital discharges each year and are associated with a mean length of stay of approximately 4.6 days.2 Alcohol and drug dependence is often an end product of a combination of biopsychosocial influences, and in most cases, a multidisciplinary approach is necessary to successfully treat affected individuals. Hospitalists can lead their institutions in evidence-based treatment protocols that improve care, reduce costs and length of stay, and facilitate better overall outcomes in patients with substance-related withdrawal syndromes.

Want all 52 JHM Core Competency articles in an easy-to-read compendium? Order your copy now from Amazon.com.

KNOWLEDGE

Hospitalists should be able to:

Describe the effects of drug and alcohol withdrawal on medical illness and the effects of medical illness on substance withdrawal.

Recognize the symptoms and signs of alcohol and drug withdrawal, including withdrawal from prescription and OTC drugs.

Recognize the medical complications from substance use and dependence.

Determine when consultation with a medical toxicologist or expert is necessary.

Distinguish alcohol or drug withdrawal from other causes of delirium.

Differentiate delirium tremens from other alcohol withdrawal syndromes.

Differentiate the clinical manifestations of alcohol or drug intoxication from those of withdrawal.

Recognize different characteristic withdrawal syndromes, such as abstinence syndrome of opioid withdrawal and delirium tremens of alcohol withdrawal.

Describe the tests indicated to evaluate alcohol or drug withdrawal.

Identify patients at increased risk for drug and alcohol withdrawal according to current diagnostic criteria.

Explain indications, contraindications, and mechanisms of action of pharmacologic agents used to treat acute alcohol and drug withdrawal.

Identify local trends in illicit drug use.

Determine the best setting within the hospital to initiate, monitor, evaluate, and treat patients with drug or alcohol withdrawal.

Explain patient characteristics that portend a poor prognosis.

Explain patient characteristics that indicate a requirement for a higher level of care and/or monitoring.

Explain goals for hospital discharge, including specific measures of clinical stability for safe care transitions.

SKILLS

Hospitalists should be able to:

Elicit a thorough and relevant medical history, with emphasis on substance use.

Assess patients with suspected alcohol or drug withdrawal in a timely manner, identify the level of care required, and manage or comanage the patient with the primary requesting service.

Perform a rapid, efficient, and targeted physical examination to assess for alcohol or drug withdrawal and determine whether life-threatening comorbidities are present.

Assess for common comorbidities in patients with a history of alcohol and drug use.

Formulate a treatment plan tailored to the individual patient, which may include appropriate pharmacologic agents and dosing, route of administration, and nutritional supplementation.

Integrate existing literature and federal regulations into the management of patients with opioid withdrawal syndromes. For patients who are undergoing existing treatment for opioid dependency, communicate with outpatient treatment centers and integrate dosing regimens into care management.

Manage withdrawal syndromes in patients with concomitant medical or surgical issues.

Diagnose oversedation and other complications associated with withdrawal therapies.

Recommend the use of restraints and direct observation to ensure patient safety when appropriate.

Reassure, reorient, and frequently monitor patients in a calm environment.

Use the acute hospitalization as an opportunity to counsel patients about abstinence, recovery, and the medical risks of drug and alcohol use.

Initiate preventive measures before discharge, including alcohol and drug cessation measures.

Facilitate discharge planning early in the hospitalization, including communicating with the primary care provider and presenting the patient with contact information for follow-up care, support, and rehabilitation.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the goals of care, discharge instructions, and management after hospital discharge to ensure safe follow-up and transition of care.

ATTITUDES

Hospitalists should be able to:

Employ a multidisciplinary approach, which may include psychiatry, pharmacy, nursing, and social services, in the treatment of patients with substance use or dependency.

Follow evidence-based national recommendations to guide diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of withdrawal symptoms.

Act in a nonjudgmental manner when managing the hospitalized patient with substance use.

Establish and maintain an open dialogue with patients and families regarding care goals and limitations.

Appreciate and document the value of appropriate treatment in reducing mortality, duration of delirium, time required to control agitation, adequate control of delirium, treatment of complications, and cost.

SYSTEM ORGANIZATION AND IMPROVEMENT

To improve efficiency and quality within their organizations, hospitalists should:

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in multidisciplinary teams, which may include psychiatry and toxicology, to improve patient safety and management strategies for patients with substance abuse.

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in the development and promotion of guidelines and/or pathways that facilitate efficient and timely evaluation and treatment of patients with alcohol and drug withdrawal.

Promote the development and use of evidence-based guidelines and protocols for the treatment of withdrawal syndromes.

Advocate for hospital resources to improve the care of patients with substance withdrawal and the environment in which the care is delivered.

Establish relationships with and develop knowledge of community-based organizations that provide support to patients with substance use disorders.

Promote awareness of substance use disorders and screening for them.

Coordinate initiatives to address the increased risk of readmissions associated with substance and polysubstance abuse.

1. Mayo-Smith MF. Pharmacological management of alcohol withdrawal. A meta-analysis and evidence-based practice guideline. American Society of Addiction Medicine Working Group on Pharmacological Management of Alcohol Withdrawal. JAMA. 1997;278(2):144-151.

2. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Available at: http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/. Accessed May 2015.

Alcohol and drug withdrawal is a set of signs and symptoms that develops in association with sudden cessation or reduction in the use of alcohol or a number of prescription (particularly opioids and benzodiazepines), over-the-counter (OTC), or illicit drugs. Withdrawal syndromes encompass a broad range of symptoms from mild anxiety and tremulousness to more serious manifestations such as delirium tremens, which occurs in up to 5% of alcohol-dependent persons who undergo withdrawal.1 Withdrawal may occur before hospitalization or during the course of hospitalization. Alcohol- and substance-related disorders account for more than 400,000 hospital discharges each year and are associated with a mean length of stay of approximately 4.6 days.2 Alcohol and drug dependence is often an end product of a combination of biopsychosocial influences, and in most cases, a multidisciplinary approach is necessary to successfully treat affected individuals. Hospitalists can lead their institutions in evidence-based treatment protocols that improve care, reduce costs and length of stay, and facilitate better overall outcomes in patients with substance-related withdrawal syndromes.

Want all 52 JHM Core Competency articles in an easy-to-read compendium? Order your copy now from Amazon.com.

KNOWLEDGE

Hospitalists should be able to:

Describe the effects of drug and alcohol withdrawal on medical illness and the effects of medical illness on substance withdrawal.

Recognize the symptoms and signs of alcohol and drug withdrawal, including withdrawal from prescription and OTC drugs.

Recognize the medical complications from substance use and dependence.

Determine when consultation with a medical toxicologist or expert is necessary.

Distinguish alcohol or drug withdrawal from other causes of delirium.

Differentiate delirium tremens from other alcohol withdrawal syndromes.

Differentiate the clinical manifestations of alcohol or drug intoxication from those of withdrawal.

Recognize different characteristic withdrawal syndromes, such as abstinence syndrome of opioid withdrawal and delirium tremens of alcohol withdrawal.

Describe the tests indicated to evaluate alcohol or drug withdrawal.

Identify patients at increased risk for drug and alcohol withdrawal according to current diagnostic criteria.

Explain indications, contraindications, and mechanisms of action of pharmacologic agents used to treat acute alcohol and drug withdrawal.

Identify local trends in illicit drug use.

Determine the best setting within the hospital to initiate, monitor, evaluate, and treat patients with drug or alcohol withdrawal.

Explain patient characteristics that portend a poor prognosis.

Explain patient characteristics that indicate a requirement for a higher level of care and/or monitoring.

Explain goals for hospital discharge, including specific measures of clinical stability for safe care transitions.

SKILLS

Hospitalists should be able to:

Elicit a thorough and relevant medical history, with emphasis on substance use.

Assess patients with suspected alcohol or drug withdrawal in a timely manner, identify the level of care required, and manage or comanage the patient with the primary requesting service.

Perform a rapid, efficient, and targeted physical examination to assess for alcohol or drug withdrawal and determine whether life-threatening comorbidities are present.

Assess for common comorbidities in patients with a history of alcohol and drug use.

Formulate a treatment plan tailored to the individual patient, which may include appropriate pharmacologic agents and dosing, route of administration, and nutritional supplementation.

Integrate existing literature and federal regulations into the management of patients with opioid withdrawal syndromes. For patients who are undergoing existing treatment for opioid dependency, communicate with outpatient treatment centers and integrate dosing regimens into care management.

Manage withdrawal syndromes in patients with concomitant medical or surgical issues.

Diagnose oversedation and other complications associated with withdrawal therapies.

Recommend the use of restraints and direct observation to ensure patient safety when appropriate.

Reassure, reorient, and frequently monitor patients in a calm environment.

Use the acute hospitalization as an opportunity to counsel patients about abstinence, recovery, and the medical risks of drug and alcohol use.

Initiate preventive measures before discharge, including alcohol and drug cessation measures.

Facilitate discharge planning early in the hospitalization, including communicating with the primary care provider and presenting the patient with contact information for follow-up care, support, and rehabilitation.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the goals of care, discharge instructions, and management after hospital discharge to ensure safe follow-up and transition of care.

ATTITUDES

Hospitalists should be able to:

Employ a multidisciplinary approach, which may include psychiatry, pharmacy, nursing, and social services, in the treatment of patients with substance use or dependency.

Follow evidence-based national recommendations to guide diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of withdrawal symptoms.

Act in a nonjudgmental manner when managing the hospitalized patient with substance use.

Establish and maintain an open dialogue with patients and families regarding care goals and limitations.

Appreciate and document the value of appropriate treatment in reducing mortality, duration of delirium, time required to control agitation, adequate control of delirium, treatment of complications, and cost.

SYSTEM ORGANIZATION AND IMPROVEMENT

To improve efficiency and quality within their organizations, hospitalists should:

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in multidisciplinary teams, which may include psychiatry and toxicology, to improve patient safety and management strategies for patients with substance abuse.

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in the development and promotion of guidelines and/or pathways that facilitate efficient and timely evaluation and treatment of patients with alcohol and drug withdrawal.

Promote the development and use of evidence-based guidelines and protocols for the treatment of withdrawal syndromes.

Advocate for hospital resources to improve the care of patients with substance withdrawal and the environment in which the care is delivered.

Establish relationships with and develop knowledge of community-based organizations that provide support to patients with substance use disorders.

Promote awareness of substance use disorders and screening for them.

Coordinate initiatives to address the increased risk of readmissions associated with substance and polysubstance abuse.

Alcohol and drug withdrawal is a set of signs and symptoms that develops in association with sudden cessation or reduction in the use of alcohol or a number of prescription (particularly opioids and benzodiazepines), over-the-counter (OTC), or illicit drugs. Withdrawal syndromes encompass a broad range of symptoms from mild anxiety and tremulousness to more serious manifestations such as delirium tremens, which occurs in up to 5% of alcohol-dependent persons who undergo withdrawal.1 Withdrawal may occur before hospitalization or during the course of hospitalization. Alcohol- and substance-related disorders account for more than 400,000 hospital discharges each year and are associated with a mean length of stay of approximately 4.6 days.2 Alcohol and drug dependence is often an end product of a combination of biopsychosocial influences, and in most cases, a multidisciplinary approach is necessary to successfully treat affected individuals. Hospitalists can lead their institutions in evidence-based treatment protocols that improve care, reduce costs and length of stay, and facilitate better overall outcomes in patients with substance-related withdrawal syndromes.

Want all 52 JHM Core Competency articles in an easy-to-read compendium? Order your copy now from Amazon.com.

KNOWLEDGE

Hospitalists should be able to:

Describe the effects of drug and alcohol withdrawal on medical illness and the effects of medical illness on substance withdrawal.

Recognize the symptoms and signs of alcohol and drug withdrawal, including withdrawal from prescription and OTC drugs.

Recognize the medical complications from substance use and dependence.

Determine when consultation with a medical toxicologist or expert is necessary.

Distinguish alcohol or drug withdrawal from other causes of delirium.

Differentiate delirium tremens from other alcohol withdrawal syndromes.

Differentiate the clinical manifestations of alcohol or drug intoxication from those of withdrawal.

Recognize different characteristic withdrawal syndromes, such as abstinence syndrome of opioid withdrawal and delirium tremens of alcohol withdrawal.

Describe the tests indicated to evaluate alcohol or drug withdrawal.

Identify patients at increased risk for drug and alcohol withdrawal according to current diagnostic criteria.

Explain indications, contraindications, and mechanisms of action of pharmacologic agents used to treat acute alcohol and drug withdrawal.

Identify local trends in illicit drug use.

Determine the best setting within the hospital to initiate, monitor, evaluate, and treat patients with drug or alcohol withdrawal.

Explain patient characteristics that portend a poor prognosis.

Explain patient characteristics that indicate a requirement for a higher level of care and/or monitoring.

Explain goals for hospital discharge, including specific measures of clinical stability for safe care transitions.

SKILLS

Hospitalists should be able to:

Elicit a thorough and relevant medical history, with emphasis on substance use.

Assess patients with suspected alcohol or drug withdrawal in a timely manner, identify the level of care required, and manage or comanage the patient with the primary requesting service.

Perform a rapid, efficient, and targeted physical examination to assess for alcohol or drug withdrawal and determine whether life-threatening comorbidities are present.

Assess for common comorbidities in patients with a history of alcohol and drug use.

Formulate a treatment plan tailored to the individual patient, which may include appropriate pharmacologic agents and dosing, route of administration, and nutritional supplementation.

Integrate existing literature and federal regulations into the management of patients with opioid withdrawal syndromes. For patients who are undergoing existing treatment for opioid dependency, communicate with outpatient treatment centers and integrate dosing regimens into care management.

Manage withdrawal syndromes in patients with concomitant medical or surgical issues.

Diagnose oversedation and other complications associated with withdrawal therapies.

Recommend the use of restraints and direct observation to ensure patient safety when appropriate.

Reassure, reorient, and frequently monitor patients in a calm environment.

Use the acute hospitalization as an opportunity to counsel patients about abstinence, recovery, and the medical risks of drug and alcohol use.

Initiate preventive measures before discharge, including alcohol and drug cessation measures.

Facilitate discharge planning early in the hospitalization, including communicating with the primary care provider and presenting the patient with contact information for follow-up care, support, and rehabilitation.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the goals of care, discharge instructions, and management after hospital discharge to ensure safe follow-up and transition of care.

ATTITUDES

Hospitalists should be able to:

Employ a multidisciplinary approach, which may include psychiatry, pharmacy, nursing, and social services, in the treatment of patients with substance use or dependency.

Follow evidence-based national recommendations to guide diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of withdrawal symptoms.

Act in a nonjudgmental manner when managing the hospitalized patient with substance use.

Establish and maintain an open dialogue with patients and families regarding care goals and limitations.

Appreciate and document the value of appropriate treatment in reducing mortality, duration of delirium, time required to control agitation, adequate control of delirium, treatment of complications, and cost.

SYSTEM ORGANIZATION AND IMPROVEMENT

To improve efficiency and quality within their organizations, hospitalists should:

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in multidisciplinary teams, which may include psychiatry and toxicology, to improve patient safety and management strategies for patients with substance abuse.

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in the development and promotion of guidelines and/or pathways that facilitate efficient and timely evaluation and treatment of patients with alcohol and drug withdrawal.

Promote the development and use of evidence-based guidelines and protocols for the treatment of withdrawal syndromes.

Advocate for hospital resources to improve the care of patients with substance withdrawal and the environment in which the care is delivered.

Establish relationships with and develop knowledge of community-based organizations that provide support to patients with substance use disorders.

Promote awareness of substance use disorders and screening for them.

Coordinate initiatives to address the increased risk of readmissions associated with substance and polysubstance abuse.

1. Mayo-Smith MF. Pharmacological management of alcohol withdrawal. A meta-analysis and evidence-based practice guideline. American Society of Addiction Medicine Working Group on Pharmacological Management of Alcohol Withdrawal. JAMA. 1997;278(2):144-151.

2. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Available at: http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/. Accessed May 2015.

1. Mayo-Smith MF. Pharmacological management of alcohol withdrawal. A meta-analysis and evidence-based practice guideline. American Society of Addiction Medicine Working Group on Pharmacological Management of Alcohol Withdrawal. JAMA. 1997;278(2):144-151.

2. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Available at: http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/. Accessed May 2015.

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Asthma. 2017 Hospital Medicine Revised Core Competencies

Asthma is a chronic disease characterized by airway inflammation and reversible airflow limitation. It is one of the most common chronic conditions and it leads to marked morbidity and mortality in hospitalized patients. In the United States, 1 in 12 persons has asthma and nearly 50% of affected individuals experience an asthma exacerbation each year, accounting for 1.8 million emergency department visits.1,2 Annually, more than 400,000 hospital discharges occur with asthma as the primary diagnosis, with an average length of stay of 3.2 days.2Hospitalists are central to the provision of care for patients with asthma through the use of evidence-based approaches to manage acute exacerbations and to prevent their recurrence. Hospitalists should strive to lead multidisciplinary teams to develop institutional guidelines and/or care pathways to improve efficiency and quality of care and to reduce readmission rates and morbidity and mortality from asthma.

Want all 52 JHM Core Competency articles in an easy-to-read compendium? Order your copy now from Amazon.com.

KNOWLEDGE

Hospitalists should be able to:

Define asthma and describe the pathophysiologic processes that lead to reversible airway obstruction and inflammation.

Identify precipitants of asthma exacerbation, including environmental and occupational exposures.

Recognize the clinical presentation of asthma exacerbation and differentiate it from other acute respiratory and nonrespiratory syndromes.

Describe the role of diagnostic testing, including peak flow monitoring, used for evaluation of asthma exacerbation.

Recognize indications for specialty consultation, including pulmonary and allergy medicine.

Describe evidence-based therapies for the treatment of asthma exacerbations, which may include bronchodilators, systemic corticosteroids, and oxygen.

Explain indications, contraindications, and mechanisms of action of pharmacologic agents used to treat asthma.

Recognize signs and symptoms of impending respiratory failure.

Explain the indications for invasive and noninvasive ventilatory support.

List the risk factors for disease severity and death from asthma.

Explain goals for hospital discharge, including specific measures of clinical stability for safe care transition.

SKILLS

Hospitalists should be able to:

Elicit a thorough and relevant medical history to identify triggers of asthma and symptoms consistent with asthma exacerbation.

Perform a targeted physical examination to elicit signs consistent with asthma exacerbation, differentiate findings from those of other mimicking conditions, and assess illness severity.

Select appropriate diagnostic studies to evaluate severity of asthma exacerbation and interpret the results.

Recognize indications for transfer to the intensive care unit, including impending respiratory failure, and coordinate intubation or noninvasive mechanical ventilation when indicated.

Prescribe appropriate evidence-based pharmacologic therapies during asthma exacerbation, recommending the most appropriate route, dose, frequency, and duration of treatment.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the natural history and prognosis of asthma.

Facilitate discharge planning early during hospitalization.

Develop an asthma action plan in preparation for discharge.

Educate patients and families regarding the indications and appropriate use of daily use inhalers and rescue inhalers for asthmatic control.

Ensure that patients receive training of proper inhaler and peak flow techniques before hospital discharge.

Communicate with patients and families to explain symptoms and signs that should prompt emergent medical attention.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the goals of care, including clinical stability criteria, the importance of preventive measures (such as smoking cessation, avoidance of second-hand smoke, appropriate vaccinations, and modification of environmental exposures), and required follow-up care.

Communicate with patients and families to explain discharge medications, potential adverse effects, duration of therapy and dosing, and taper schedule.

Document the treatment plan and provide clear discharge instructions for postdischarge clinicians.

Provide and coordinate resources to ensure safe transition from the hospital to arranged follow-up care.

ATTITUDES

Hospitalists should be able to:

Work collaboratively with primary care physicians and emergency physicians in making admission decisions.

Employ a multidisciplinary approach, which may include pulmonary medicine, respiratory therapy, nursing, and social services, in the care of patients with asthma exacerbation.

Follow evidence-based recommendations for the treatment of patients with asthma exacerbations.

SYSTEM ORGANIZATION AND IMPROVEMENT

To improve efficiency and quality within their organizations, hospitalists should:

Contribute to and/or develop educational modules, order sets, and/or pathways that facilitate use of evidence-based strategies for asthma exacerbation in the emergency department and the hospital, with goals of improving outcomes, decreasing length of stay, and reducing rehospitalization rates.

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in efforts to educate staff on the importance of smoking cessation counseling and other preventive measures.

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in multidisciplinary initiatives, which may include collaborative efforts with pulmonologists and respiratory therapists, to promote patient safety and optimize cost-effective diagnostic and management strategies for patients with asthma.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Vital Signs: Asthma in the US. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/asthma/. Accessed June 2015.

2. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Available at: http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/. Accessed June 2015.

Asthma is a chronic disease characterized by airway inflammation and reversible airflow limitation. It is one of the most common chronic conditions and it leads to marked morbidity and mortality in hospitalized patients. In the United States, 1 in 12 persons has asthma and nearly 50% of affected individuals experience an asthma exacerbation each year, accounting for 1.8 million emergency department visits.1,2 Annually, more than 400,000 hospital discharges occur with asthma as the primary diagnosis, with an average length of stay of 3.2 days.2Hospitalists are central to the provision of care for patients with asthma through the use of evidence-based approaches to manage acute exacerbations and to prevent their recurrence. Hospitalists should strive to lead multidisciplinary teams to develop institutional guidelines and/or care pathways to improve efficiency and quality of care and to reduce readmission rates and morbidity and mortality from asthma.

Want all 52 JHM Core Competency articles in an easy-to-read compendium? Order your copy now from Amazon.com.

KNOWLEDGE

Hospitalists should be able to:

Define asthma and describe the pathophysiologic processes that lead to reversible airway obstruction and inflammation.

Identify precipitants of asthma exacerbation, including environmental and occupational exposures.

Recognize the clinical presentation of asthma exacerbation and differentiate it from other acute respiratory and nonrespiratory syndromes.

Describe the role of diagnostic testing, including peak flow monitoring, used for evaluation of asthma exacerbation.

Recognize indications for specialty consultation, including pulmonary and allergy medicine.

Describe evidence-based therapies for the treatment of asthma exacerbations, which may include bronchodilators, systemic corticosteroids, and oxygen.

Explain indications, contraindications, and mechanisms of action of pharmacologic agents used to treat asthma.

Recognize signs and symptoms of impending respiratory failure.

Explain the indications for invasive and noninvasive ventilatory support.

List the risk factors for disease severity and death from asthma.

Explain goals for hospital discharge, including specific measures of clinical stability for safe care transition.

SKILLS

Hospitalists should be able to:

Elicit a thorough and relevant medical history to identify triggers of asthma and symptoms consistent with asthma exacerbation.

Perform a targeted physical examination to elicit signs consistent with asthma exacerbation, differentiate findings from those of other mimicking conditions, and assess illness severity.

Select appropriate diagnostic studies to evaluate severity of asthma exacerbation and interpret the results.

Recognize indications for transfer to the intensive care unit, including impending respiratory failure, and coordinate intubation or noninvasive mechanical ventilation when indicated.

Prescribe appropriate evidence-based pharmacologic therapies during asthma exacerbation, recommending the most appropriate route, dose, frequency, and duration of treatment.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the natural history and prognosis of asthma.

Facilitate discharge planning early during hospitalization.

Develop an asthma action plan in preparation for discharge.

Educate patients and families regarding the indications and appropriate use of daily use inhalers and rescue inhalers for asthmatic control.

Ensure that patients receive training of proper inhaler and peak flow techniques before hospital discharge.

Communicate with patients and families to explain symptoms and signs that should prompt emergent medical attention.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the goals of care, including clinical stability criteria, the importance of preventive measures (such as smoking cessation, avoidance of second-hand smoke, appropriate vaccinations, and modification of environmental exposures), and required follow-up care.

Communicate with patients and families to explain discharge medications, potential adverse effects, duration of therapy and dosing, and taper schedule.

Document the treatment plan and provide clear discharge instructions for postdischarge clinicians.

Provide and coordinate resources to ensure safe transition from the hospital to arranged follow-up care.

ATTITUDES

Hospitalists should be able to:

Work collaboratively with primary care physicians and emergency physicians in making admission decisions.

Employ a multidisciplinary approach, which may include pulmonary medicine, respiratory therapy, nursing, and social services, in the care of patients with asthma exacerbation.

Follow evidence-based recommendations for the treatment of patients with asthma exacerbations.

SYSTEM ORGANIZATION AND IMPROVEMENT

To improve efficiency and quality within their organizations, hospitalists should:

Contribute to and/or develop educational modules, order sets, and/or pathways that facilitate use of evidence-based strategies for asthma exacerbation in the emergency department and the hospital, with goals of improving outcomes, decreasing length of stay, and reducing rehospitalization rates.

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in efforts to educate staff on the importance of smoking cessation counseling and other preventive measures.

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in multidisciplinary initiatives, which may include collaborative efforts with pulmonologists and respiratory therapists, to promote patient safety and optimize cost-effective diagnostic and management strategies for patients with asthma.

Asthma is a chronic disease characterized by airway inflammation and reversible airflow limitation. It is one of the most common chronic conditions and it leads to marked morbidity and mortality in hospitalized patients. In the United States, 1 in 12 persons has asthma and nearly 50% of affected individuals experience an asthma exacerbation each year, accounting for 1.8 million emergency department visits.1,2 Annually, more than 400,000 hospital discharges occur with asthma as the primary diagnosis, with an average length of stay of 3.2 days.2Hospitalists are central to the provision of care for patients with asthma through the use of evidence-based approaches to manage acute exacerbations and to prevent their recurrence. Hospitalists should strive to lead multidisciplinary teams to develop institutional guidelines and/or care pathways to improve efficiency and quality of care and to reduce readmission rates and morbidity and mortality from asthma.

Want all 52 JHM Core Competency articles in an easy-to-read compendium? Order your copy now from Amazon.com.

KNOWLEDGE

Hospitalists should be able to:

Define asthma and describe the pathophysiologic processes that lead to reversible airway obstruction and inflammation.

Identify precipitants of asthma exacerbation, including environmental and occupational exposures.

Recognize the clinical presentation of asthma exacerbation and differentiate it from other acute respiratory and nonrespiratory syndromes.

Describe the role of diagnostic testing, including peak flow monitoring, used for evaluation of asthma exacerbation.

Recognize indications for specialty consultation, including pulmonary and allergy medicine.

Describe evidence-based therapies for the treatment of asthma exacerbations, which may include bronchodilators, systemic corticosteroids, and oxygen.

Explain indications, contraindications, and mechanisms of action of pharmacologic agents used to treat asthma.

Recognize signs and symptoms of impending respiratory failure.

Explain the indications for invasive and noninvasive ventilatory support.

List the risk factors for disease severity and death from asthma.

Explain goals for hospital discharge, including specific measures of clinical stability for safe care transition.

SKILLS

Hospitalists should be able to:

Elicit a thorough and relevant medical history to identify triggers of asthma and symptoms consistent with asthma exacerbation.

Perform a targeted physical examination to elicit signs consistent with asthma exacerbation, differentiate findings from those of other mimicking conditions, and assess illness severity.

Select appropriate diagnostic studies to evaluate severity of asthma exacerbation and interpret the results.

Recognize indications for transfer to the intensive care unit, including impending respiratory failure, and coordinate intubation or noninvasive mechanical ventilation when indicated.

Prescribe appropriate evidence-based pharmacologic therapies during asthma exacerbation, recommending the most appropriate route, dose, frequency, and duration of treatment.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the natural history and prognosis of asthma.

Facilitate discharge planning early during hospitalization.

Develop an asthma action plan in preparation for discharge.

Educate patients and families regarding the indications and appropriate use of daily use inhalers and rescue inhalers for asthmatic control.

Ensure that patients receive training of proper inhaler and peak flow techniques before hospital discharge.

Communicate with patients and families to explain symptoms and signs that should prompt emergent medical attention.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the goals of care, including clinical stability criteria, the importance of preventive measures (such as smoking cessation, avoidance of second-hand smoke, appropriate vaccinations, and modification of environmental exposures), and required follow-up care.

Communicate with patients and families to explain discharge medications, potential adverse effects, duration of therapy and dosing, and taper schedule.

Document the treatment plan and provide clear discharge instructions for postdischarge clinicians.

Provide and coordinate resources to ensure safe transition from the hospital to arranged follow-up care.

ATTITUDES

Hospitalists should be able to:

Work collaboratively with primary care physicians and emergency physicians in making admission decisions.

Employ a multidisciplinary approach, which may include pulmonary medicine, respiratory therapy, nursing, and social services, in the care of patients with asthma exacerbation.

Follow evidence-based recommendations for the treatment of patients with asthma exacerbations.

SYSTEM ORGANIZATION AND IMPROVEMENT

To improve efficiency and quality within their organizations, hospitalists should:

Contribute to and/or develop educational modules, order sets, and/or pathways that facilitate use of evidence-based strategies for asthma exacerbation in the emergency department and the hospital, with goals of improving outcomes, decreasing length of stay, and reducing rehospitalization rates.

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in efforts to educate staff on the importance of smoking cessation counseling and other preventive measures.

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in multidisciplinary initiatives, which may include collaborative efforts with pulmonologists and respiratory therapists, to promote patient safety and optimize cost-effective diagnostic and management strategies for patients with asthma.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Vital Signs: Asthma in the US. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/asthma/. Accessed June 2015.

2. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Available at: http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/. Accessed June 2015.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Vital Signs: Asthma in the US. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/asthma/. Accessed June 2015.

2. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Available at: http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/. Accessed June 2015.

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Cardiac Arrhythmia. 2017 Hospital Medicine Revised Core Competencies

Cardiac arrhythmias are a group of conditions characterized by an abnormal heart rate or rhythm. These are common and affect approximately 5% of the population in the United States. More than 250,000 Americans die each year of sudden cardiac arrest, and most cases are thought to be due to ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia.1 Several cardiac arrhythmias can cause instability, prompting hospitalization, or they may result from complications during hospitalization. Annually, more than 740,000 hospital discharges are associated with a primary diagnosis of cardiac arrhythmia.2 Hospitalists identify and treat all types of arrhythmias, coordinate specialty and primary care resources, and transition patients safely and cost-effectively through the acute hospitalization and into the outpatient setting.

Want all 52 JHM Core Competency articles in an easy-to-read compendium? Order your copy now from Amazon.com.

KNOWLEDGE

Hospitalists should be able to:

Identify and differentiate the common clinical presentations of both benign and pathologic arrhythmias.

Explain the causes of atrial and ventricular arrhythmias.

Describe the indicated tests required to evaluate arrhythmias.

Explain how medications, metabolic abnormalities, and medical comorbidities may precipitate various arrhythmias.

Explain indications, contraindications, and mechanisms of action of pharmacologic agents used to treat cardiac arrhythmias. Discuss the management options and goals for patients hospitalized with arrhythmias.

Describe the patient characteristics and comorbid conditions that predict outcomes in patients with arrhythmias.

Recognize indications for specialty consultation, which may include cardiology and cardiac electrophysiology.

Explain goals for hospital discharge, including specific measures of clinical stability for safe care transitions.

Recall appropriate indications for both initiation and discontinuation of continuous telemetry monitoring in the hospitalized patient.

SKILLS

Hospitalists should be able to:

Elicit a thorough and relevant medical history, including medications, family history, and social history.

Perform a targeted physical examination with emphasis on identifying signs associated with hemodynamic instability, tissue perfusion, and occult cardiac and vascular disease.

Identify common benign and pathologic arrhythmias on electrocardiography, rhythm strips, and continuous telemetry monitoring.

Determine the appropriate level of care required based on risk stratification of patients with cardiac arrhythmias.

Identify and prioritize high-risk arrhythmias that require urgent intervention and implement emergency protocols as indicated.

Formulate patient-specific and evidence-based care plans incorporating diagnostic findings, prognosis, and patient characteristics.

Develop patient-specific care plans that may include rate-controlling interventions, cardioversion, defibrillation, or implantable medical devices.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the natural history and prognosis of cardiac arrhythmias.

Communicate with patients and families to explain tests and procedures and their indications and to obtain informed consent.

Communicate with patients and families to explain drug interactions for antiarrhythmic drugs and the importance of strict adherence to medication regimens and laboratory monitoring.

Facilitate discharge planning early during hospitalization.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the goals of care, discharge instructions, and management after hospital discharge to ensure safe follow-up and transitions of care.

Document the treatment plan and provide clear discharge instructions for postdischarge clinicians.

ATTITUDES

Hospitalists should be able to:

Employ a multidisciplinary approach, which may include primary care, cardiology, nursing, and social services, in the care of patients with cardiac arrhythmias that begins at admission and continues through all care transitions.

Follow evidence-based recommendations to guide diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of cardiac arrhythmias.

Acknowledge and ameliorate patient discomfort from uncontrolled arrhythmias and electrical cardioversion therapies.

SYSTEM ORGANIZATION AND IMPROVEMENT

To improve efficiency and quality within their organizations, hospitalists should:

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in multidisciplinary teams to develop patient care guidelines and/or pathways on the basis of peer-reviewed outcomes research, patient and physician satisfaction, and cost.

Implement systems to ensure hospital-wide adherence to national standards and document those measures as specified by recognized organizations (eg, The Joint Commission, American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality).

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in quality improvement initiatives to promote early identification of arrhythmias, reduce preventable complications, and promote appropriate use of telemetry resources.

Cardiac arrhythmias are a group of conditions characterized by an abnormal heart rate or rhythm. These are common and affect approximately 5% of the population in the United States. More than 250,000 Americans die each year of sudden cardiac arrest, and most cases are thought to be due to ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia.1 Several cardiac arrhythmias can cause instability, prompting hospitalization, or they may result from complications during hospitalization. Annually, more than 740,000 hospital discharges are associated with a primary diagnosis of cardiac arrhythmia.2 Hospitalists identify and treat all types of arrhythmias, coordinate specialty and primary care resources, and transition patients safely and cost-effectively through the acute hospitalization and into the outpatient setting.

Want all 52 JHM Core Competency articles in an easy-to-read compendium? Order your copy now from Amazon.com.

KNOWLEDGE

Hospitalists should be able to:

Identify and differentiate the common clinical presentations of both benign and pathologic arrhythmias.

Explain the causes of atrial and ventricular arrhythmias.

Describe the indicated tests required to evaluate arrhythmias.

Explain how medications, metabolic abnormalities, and medical comorbidities may precipitate various arrhythmias.

Explain indications, contraindications, and mechanisms of action of pharmacologic agents used to treat cardiac arrhythmias. Discuss the management options and goals for patients hospitalized with arrhythmias.

Describe the patient characteristics and comorbid conditions that predict outcomes in patients with arrhythmias.

Recognize indications for specialty consultation, which may include cardiology and cardiac electrophysiology.

Explain goals for hospital discharge, including specific measures of clinical stability for safe care transitions.

Recall appropriate indications for both initiation and discontinuation of continuous telemetry monitoring in the hospitalized patient.

SKILLS

Hospitalists should be able to:

Elicit a thorough and relevant medical history, including medications, family history, and social history.

Perform a targeted physical examination with emphasis on identifying signs associated with hemodynamic instability, tissue perfusion, and occult cardiac and vascular disease.

Identify common benign and pathologic arrhythmias on electrocardiography, rhythm strips, and continuous telemetry monitoring.

Determine the appropriate level of care required based on risk stratification of patients with cardiac arrhythmias.

Identify and prioritize high-risk arrhythmias that require urgent intervention and implement emergency protocols as indicated.

Formulate patient-specific and evidence-based care plans incorporating diagnostic findings, prognosis, and patient characteristics.

Develop patient-specific care plans that may include rate-controlling interventions, cardioversion, defibrillation, or implantable medical devices.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the natural history and prognosis of cardiac arrhythmias.

Communicate with patients and families to explain tests and procedures and their indications and to obtain informed consent.

Communicate with patients and families to explain drug interactions for antiarrhythmic drugs and the importance of strict adherence to medication regimens and laboratory monitoring.

Facilitate discharge planning early during hospitalization.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the goals of care, discharge instructions, and management after hospital discharge to ensure safe follow-up and transitions of care.

Document the treatment plan and provide clear discharge instructions for postdischarge clinicians.

ATTITUDES

Hospitalists should be able to:

Employ a multidisciplinary approach, which may include primary care, cardiology, nursing, and social services, in the care of patients with cardiac arrhythmias that begins at admission and continues through all care transitions.

Follow evidence-based recommendations to guide diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of cardiac arrhythmias.

Acknowledge and ameliorate patient discomfort from uncontrolled arrhythmias and electrical cardioversion therapies.

SYSTEM ORGANIZATION AND IMPROVEMENT

To improve efficiency and quality within their organizations, hospitalists should:

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in multidisciplinary teams to develop patient care guidelines and/or pathways on the basis of peer-reviewed outcomes research, patient and physician satisfaction, and cost.

Implement systems to ensure hospital-wide adherence to national standards and document those measures as specified by recognized organizations (eg, The Joint Commission, American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality).

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in quality improvement initiatives to promote early identification of arrhythmias, reduce preventable complications, and promote appropriate use of telemetry resources.

Cardiac arrhythmias are a group of conditions characterized by an abnormal heart rate or rhythm. These are common and affect approximately 5% of the population in the United States. More than 250,000 Americans die each year of sudden cardiac arrest, and most cases are thought to be due to ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia.1 Several cardiac arrhythmias can cause instability, prompting hospitalization, or they may result from complications during hospitalization. Annually, more than 740,000 hospital discharges are associated with a primary diagnosis of cardiac arrhythmia.2 Hospitalists identify and treat all types of arrhythmias, coordinate specialty and primary care resources, and transition patients safely and cost-effectively through the acute hospitalization and into the outpatient setting.

Want all 52 JHM Core Competency articles in an easy-to-read compendium? Order your copy now from Amazon.com.

KNOWLEDGE

Hospitalists should be able to:

Identify and differentiate the common clinical presentations of both benign and pathologic arrhythmias.

Explain the causes of atrial and ventricular arrhythmias.

Describe the indicated tests required to evaluate arrhythmias.

Explain how medications, metabolic abnormalities, and medical comorbidities may precipitate various arrhythmias.

Explain indications, contraindications, and mechanisms of action of pharmacologic agents used to treat cardiac arrhythmias. Discuss the management options and goals for patients hospitalized with arrhythmias.

Describe the patient characteristics and comorbid conditions that predict outcomes in patients with arrhythmias.

Recognize indications for specialty consultation, which may include cardiology and cardiac electrophysiology.

Explain goals for hospital discharge, including specific measures of clinical stability for safe care transitions.

Recall appropriate indications for both initiation and discontinuation of continuous telemetry monitoring in the hospitalized patient.

SKILLS

Hospitalists should be able to:

Elicit a thorough and relevant medical history, including medications, family history, and social history.

Perform a targeted physical examination with emphasis on identifying signs associated with hemodynamic instability, tissue perfusion, and occult cardiac and vascular disease.

Identify common benign and pathologic arrhythmias on electrocardiography, rhythm strips, and continuous telemetry monitoring.

Determine the appropriate level of care required based on risk stratification of patients with cardiac arrhythmias.

Identify and prioritize high-risk arrhythmias that require urgent intervention and implement emergency protocols as indicated.

Formulate patient-specific and evidence-based care plans incorporating diagnostic findings, prognosis, and patient characteristics.

Develop patient-specific care plans that may include rate-controlling interventions, cardioversion, defibrillation, or implantable medical devices.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the natural history and prognosis of cardiac arrhythmias.

Communicate with patients and families to explain tests and procedures and their indications and to obtain informed consent.

Communicate with patients and families to explain drug interactions for antiarrhythmic drugs and the importance of strict adherence to medication regimens and laboratory monitoring.

Facilitate discharge planning early during hospitalization.

Communicate with patients and families to explain the goals of care, discharge instructions, and management after hospital discharge to ensure safe follow-up and transitions of care.

Document the treatment plan and provide clear discharge instructions for postdischarge clinicians.

ATTITUDES

Hospitalists should be able to:

Employ a multidisciplinary approach, which may include primary care, cardiology, nursing, and social services, in the care of patients with cardiac arrhythmias that begins at admission and continues through all care transitions.

Follow evidence-based recommendations to guide diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of cardiac arrhythmias.

Acknowledge and ameliorate patient discomfort from uncontrolled arrhythmias and electrical cardioversion therapies.

SYSTEM ORGANIZATION AND IMPROVEMENT

To improve efficiency and quality within their organizations, hospitalists should:

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in multidisciplinary teams to develop patient care guidelines and/or pathways on the basis of peer-reviewed outcomes research, patient and physician satisfaction, and cost.

Implement systems to ensure hospital-wide adherence to national standards and document those measures as specified by recognized organizations (eg, The Joint Commission, American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality).

Lead, coordinate, and/or participate in quality improvement initiatives to promote early identification of arrhythmias, reduce preventable complications, and promote appropriate use of telemetry resources.