User login

Mobile App Usage Among Dermatology Residents in America

Mobile applications (apps) have been a growing part of medicine for the last decade. In 2020, more than 15.5 million apps were available for download,1 and more than 325,000 apps were health related.2 Much of the peer-reviewed literature on health-related apps has focused on apps that target patients. Therefore, we studied apps for health care providers, specifically dermatology residents of different sexes throughout residency. We investigated the role of apps in their training, including how often residents consult apps, which apps they utilize, and why.

Methods

An original online survey regarding mobile apps was emailed to all 1587 dermatology residents in America by the American Academy of Dermatology from summer 2019 to summer 2020. Responses were anonymous, voluntary, unincentivized, and collected over 17 days. To protect respondent privacy, minimal data were collected regarding training programs; geography served as a proxy for how resource rich or resource poor those programs may be. Categorization of urban vs rural was based on the 2010 Census classification, such that Arizona; California; Colorado; Connecticut; Florida; Illinois; Maryland; Massachusetts; New Jersey; New York; Oregon; Puerto Rico; Rhode Island; Texas; Utah; and Washington, DC, were urban, and the remaining states were rural.3

We hypothesized that VisualDx would be 1 of 3 most prevalent apps; “diagnosis and workup” and “self-education” would be top reasons for using apps; “up-to-date and accurate information” would be a top 3 consideration when choosing apps; the most consulted resources for clinical experiences would be providers, followed by websites, apps, and lastly printed text; and the percentage of clinical experiences for which a provider was consulted would be higher for first-year residents than other years and for female residents than male residents.

Fisher exact 2-tailed and Kruskal-Wallis (KW) pairwise tests were used to compare groups. Statistical significance was set at P<.05.

Results

Respondents

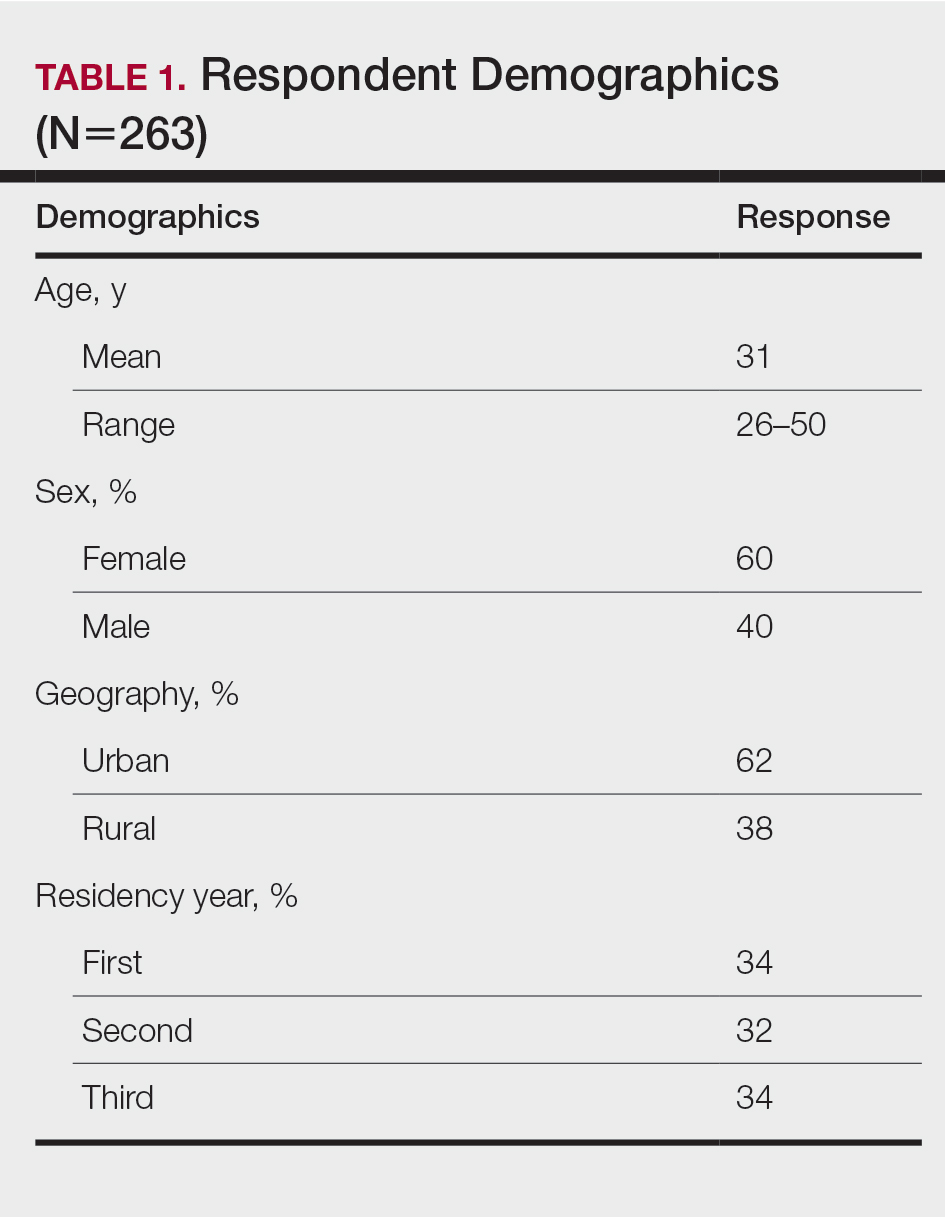

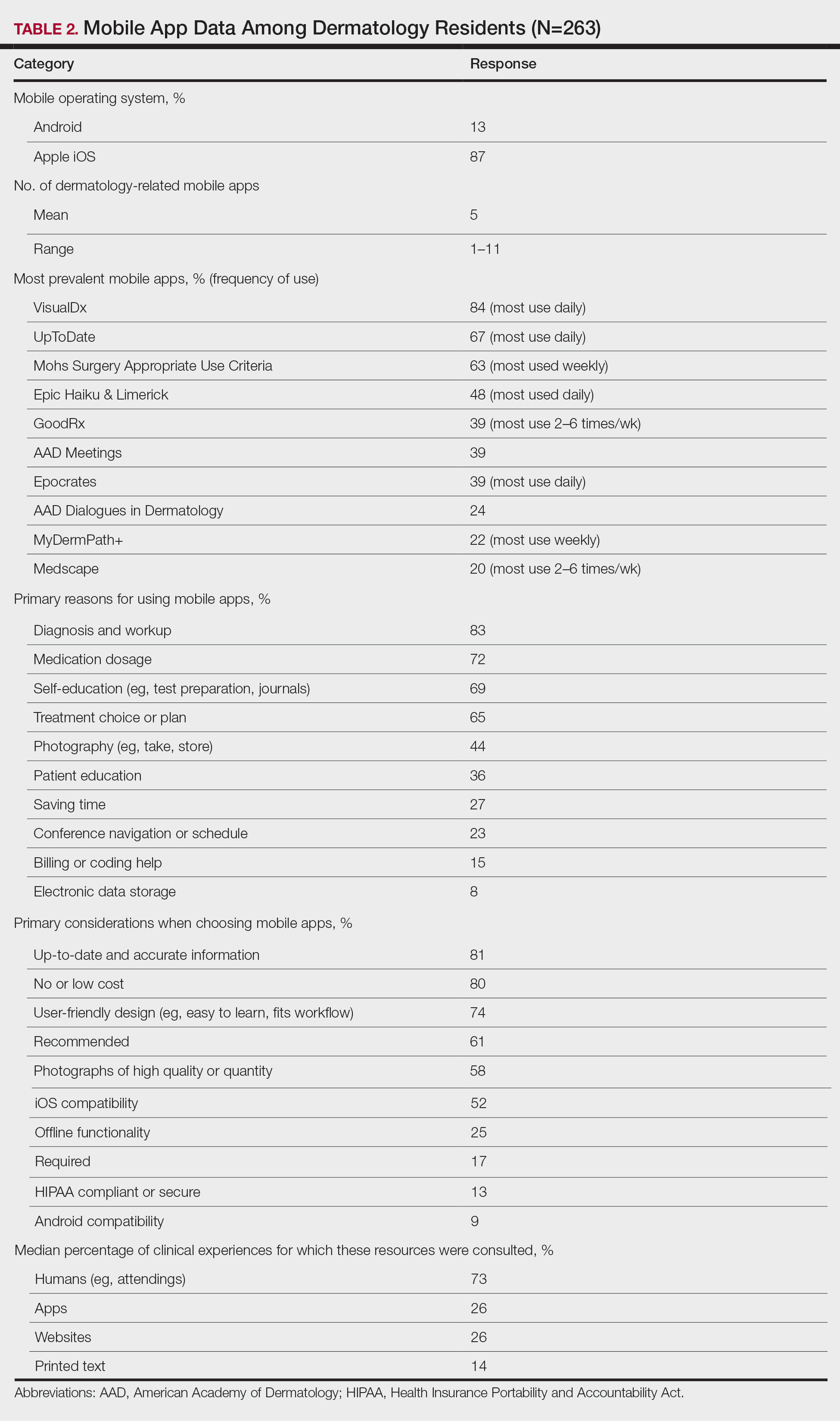

The response rate was 16.6% (n=263), which is similar to prior response rates for American Academy of Dermatology surveys. Table 1 contains respondent demographics. The mean age of respondents was 31 years. Sixty percent of respondents were female; 62% of respondents were training in urban states or territories. Regarding the dermatology residency year, 34% of respondents were in their first year, 32% were in their second, and 34% were in their third. Eighty-seven percent of respondents used Apple iOS. Every respondent used at least 1 dermatology-related app (mean, 5; range, 1–11)(Table 2).

Top Dermatology-Related Apps

The 10 most prevalent apps are listed in Table 2. The 3 most prevalent apps were VisualDx (84%, majority of respondents used daily), UpToDate (67%, majority of respondents used daily), and Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria (63%, majority of respondents used weekly). A higher percentage of third-year residents used GoodRx compared to first- and second-year residents (Fisher exact test: P=.014 and P=.041, respectively). A lower percentage of female respondents used GoodRx compared to male residents (Fisher exact test: P=.003). None of the apps were app versions of printed text, including textbooks or journals.

Reasons for Using Apps

The 10 primary reasons for using apps are listed in Table 2. The top 3 reasons were diagnosis and workup (83%), medication dosage (72%), and self-education (69%). Medication dosage and saving time were both selected by a higher percentage of third-year residents than first-year residents (Fisher exact test: P=.041 and P=.024, respectively). Self-education was selected by a lower percentage of third-year residents than second-year residents (Fisher exact test: P=.025).

Considerations When Choosing Apps

The 10 primary considerations when choosing apps are listed in Table 2. The top 3 considerations were up-to-date and accurate information (81%), no/low cost (80%), and user-friendly design (74%). Up-to-date and accurate information was selected by a lower percentage of third-year residents than first- and second-year residents (Fisher exact test: P=.02 and P=.03, respectively).

Consulted Resources

Apps were the second most consulted resource (26%) during clinical work, behind human guidance (73%). Female respondents consulted both resources more than male respondents (KW: P≤.005 and P≤.003, respectively). First-year residents consulted humans more than second-year and third-year residents (KW: P<.0001).

There were no significant differences by geography or mobile operating system.

Comment

The response rate and demographic results suggest that our study sample is representative of the target population of dermatology residents in America. Overall, the survey results support our hypotheses.

A survey conducted in 2008 before apps were readily available found that dermatology residents felt they learned more successfully when engaging in hands-on, direct experience; talking with experts/consultants; and studying printed materials than when using multimedia programs.4 Our study suggests that the usage of and preference for multimedia programs, including apps, in dermatology resident training has risen substantially, despite the continued availability of guidance from attendings and senior residents.

As residents progress through training, they increasingly turn to virtual resources. According to our survey, junior residents are more likely than third-year residents to use apps for self-education, and up-to-date and accurate information was a more important consideration when choosing apps. Third-year residents are more likely than junior residents to use apps for medication dosage and saving time. Perhaps related, GoodRx, an app that provides prescription discounts, was more prevalent among third-year residents. It is notable that most of the reported apps, including those used for diagnosis and treatment, did not need premarket government approval to ensure patient safety, are not required to contain up-to-date information, and do not reference primary sources. Additionally, only UpToDate has been shown in peer-reviewed literature to improve clinical outcomes.5

Our survey also revealed a few differences by sex. Female respondents consulted resources during clinical work more often than male residents. This finding is similar to the limited existing research on dermatologists’ utilization of information showing higher dermoscopy use among female attendings.6 Use of GoodRx was less prevalent among female vs male respondents. Perhaps related, a 2011 study found that female primary care physicians are less likely to prescribe medications than their male counterparts.7

Our study had several limitations. There may have been selection bias such that the residents who chose to participate were relatively more interested in mobile health. Certain demographic data, such as race, were not captured because prior studies do not suggest disparity by those demographics for mobile health utilization among residents, but those data could be incorporated into future studies. Our survey was intentionally limited in scope. For example, it did not capture the amount of time spent on each consult resource or the motivations for consulting an app instead of a provider.

Conclusion

A main objective of residency is to train new physicians to provide excellent patient care. Our survey highlights the increasing role of apps in dermatology residency, different priorities among years of residency, and different information utilization between sexes. This knowledge should encourage and help guide standardization and quality assurance of virtual residency education and integration of virtual resources into formal curricula. Residency administrators and residents should be aware of the apps used to learn and deliver care, consider the evidence for and regulation of those apps, and evaluate the accessibility and approachability of attendings to residents. Future research should examine the educational and clinical outcomes of app utilization among residents and the impact of residency programs’ unspoken cultures and expectations on relationships among residents of different demographics and their attendings.

- Statistica. Number of apps available in leading app stores 2020. Accessed September 21, 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/276623/number-of-apps-available-in-leading-app-stores/

- Research2Guidance. mHealth economics 2017—current status and future trends in mobile health. Accessed July 16, 2021. https://research2guidance.com/product/mhealth-economics-2017-current-status-and-future-trends-in-mobile-health/

- United States Census Bureau. 2010 Census Urban and Rural Classification and Urban Area Criteria. Accessed September 21, 2020. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/geography/guidance/geo-areas/urban-rural/2010-urban-rural.html

- Stratman EJ, Vogel CA, Reck SJ, et al. Analysis of dermatology resident self-reported successful learning styles and implications for core competency curriculum development. Med Teach. 2008;30:420-425.

- Wolters Kluwer. UpToDate is the only clinical decision support resource associated with improved outcomes. Accessed July 22, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/home/research

- Engasser HC, Warshaw EM. Dermatoscopy use by US dermatologists: a cross-sectional survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:412-419.

- Smith AW, Borowski LA, Liu B, et al. U.S. primary care physicians’ diet-, physical activity–, and weight-related care of adult patients. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41:33-42. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.03.017

Mobile applications (apps) have been a growing part of medicine for the last decade. In 2020, more than 15.5 million apps were available for download,1 and more than 325,000 apps were health related.2 Much of the peer-reviewed literature on health-related apps has focused on apps that target patients. Therefore, we studied apps for health care providers, specifically dermatology residents of different sexes throughout residency. We investigated the role of apps in their training, including how often residents consult apps, which apps they utilize, and why.

Methods

An original online survey regarding mobile apps was emailed to all 1587 dermatology residents in America by the American Academy of Dermatology from summer 2019 to summer 2020. Responses were anonymous, voluntary, unincentivized, and collected over 17 days. To protect respondent privacy, minimal data were collected regarding training programs; geography served as a proxy for how resource rich or resource poor those programs may be. Categorization of urban vs rural was based on the 2010 Census classification, such that Arizona; California; Colorado; Connecticut; Florida; Illinois; Maryland; Massachusetts; New Jersey; New York; Oregon; Puerto Rico; Rhode Island; Texas; Utah; and Washington, DC, were urban, and the remaining states were rural.3

We hypothesized that VisualDx would be 1 of 3 most prevalent apps; “diagnosis and workup” and “self-education” would be top reasons for using apps; “up-to-date and accurate information” would be a top 3 consideration when choosing apps; the most consulted resources for clinical experiences would be providers, followed by websites, apps, and lastly printed text; and the percentage of clinical experiences for which a provider was consulted would be higher for first-year residents than other years and for female residents than male residents.

Fisher exact 2-tailed and Kruskal-Wallis (KW) pairwise tests were used to compare groups. Statistical significance was set at P<.05.

Results

Respondents

The response rate was 16.6% (n=263), which is similar to prior response rates for American Academy of Dermatology surveys. Table 1 contains respondent demographics. The mean age of respondents was 31 years. Sixty percent of respondents were female; 62% of respondents were training in urban states or territories. Regarding the dermatology residency year, 34% of respondents were in their first year, 32% were in their second, and 34% were in their third. Eighty-seven percent of respondents used Apple iOS. Every respondent used at least 1 dermatology-related app (mean, 5; range, 1–11)(Table 2).

Top Dermatology-Related Apps

The 10 most prevalent apps are listed in Table 2. The 3 most prevalent apps were VisualDx (84%, majority of respondents used daily), UpToDate (67%, majority of respondents used daily), and Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria (63%, majority of respondents used weekly). A higher percentage of third-year residents used GoodRx compared to first- and second-year residents (Fisher exact test: P=.014 and P=.041, respectively). A lower percentage of female respondents used GoodRx compared to male residents (Fisher exact test: P=.003). None of the apps were app versions of printed text, including textbooks or journals.

Reasons for Using Apps

The 10 primary reasons for using apps are listed in Table 2. The top 3 reasons were diagnosis and workup (83%), medication dosage (72%), and self-education (69%). Medication dosage and saving time were both selected by a higher percentage of third-year residents than first-year residents (Fisher exact test: P=.041 and P=.024, respectively). Self-education was selected by a lower percentage of third-year residents than second-year residents (Fisher exact test: P=.025).

Considerations When Choosing Apps

The 10 primary considerations when choosing apps are listed in Table 2. The top 3 considerations were up-to-date and accurate information (81%), no/low cost (80%), and user-friendly design (74%). Up-to-date and accurate information was selected by a lower percentage of third-year residents than first- and second-year residents (Fisher exact test: P=.02 and P=.03, respectively).

Consulted Resources

Apps were the second most consulted resource (26%) during clinical work, behind human guidance (73%). Female respondents consulted both resources more than male respondents (KW: P≤.005 and P≤.003, respectively). First-year residents consulted humans more than second-year and third-year residents (KW: P<.0001).

There were no significant differences by geography or mobile operating system.

Comment

The response rate and demographic results suggest that our study sample is representative of the target population of dermatology residents in America. Overall, the survey results support our hypotheses.

A survey conducted in 2008 before apps were readily available found that dermatology residents felt they learned more successfully when engaging in hands-on, direct experience; talking with experts/consultants; and studying printed materials than when using multimedia programs.4 Our study suggests that the usage of and preference for multimedia programs, including apps, in dermatology resident training has risen substantially, despite the continued availability of guidance from attendings and senior residents.

As residents progress through training, they increasingly turn to virtual resources. According to our survey, junior residents are more likely than third-year residents to use apps for self-education, and up-to-date and accurate information was a more important consideration when choosing apps. Third-year residents are more likely than junior residents to use apps for medication dosage and saving time. Perhaps related, GoodRx, an app that provides prescription discounts, was more prevalent among third-year residents. It is notable that most of the reported apps, including those used for diagnosis and treatment, did not need premarket government approval to ensure patient safety, are not required to contain up-to-date information, and do not reference primary sources. Additionally, only UpToDate has been shown in peer-reviewed literature to improve clinical outcomes.5

Our survey also revealed a few differences by sex. Female respondents consulted resources during clinical work more often than male residents. This finding is similar to the limited existing research on dermatologists’ utilization of information showing higher dermoscopy use among female attendings.6 Use of GoodRx was less prevalent among female vs male respondents. Perhaps related, a 2011 study found that female primary care physicians are less likely to prescribe medications than their male counterparts.7

Our study had several limitations. There may have been selection bias such that the residents who chose to participate were relatively more interested in mobile health. Certain demographic data, such as race, were not captured because prior studies do not suggest disparity by those demographics for mobile health utilization among residents, but those data could be incorporated into future studies. Our survey was intentionally limited in scope. For example, it did not capture the amount of time spent on each consult resource or the motivations for consulting an app instead of a provider.

Conclusion

A main objective of residency is to train new physicians to provide excellent patient care. Our survey highlights the increasing role of apps in dermatology residency, different priorities among years of residency, and different information utilization between sexes. This knowledge should encourage and help guide standardization and quality assurance of virtual residency education and integration of virtual resources into formal curricula. Residency administrators and residents should be aware of the apps used to learn and deliver care, consider the evidence for and regulation of those apps, and evaluate the accessibility and approachability of attendings to residents. Future research should examine the educational and clinical outcomes of app utilization among residents and the impact of residency programs’ unspoken cultures and expectations on relationships among residents of different demographics and their attendings.

Mobile applications (apps) have been a growing part of medicine for the last decade. In 2020, more than 15.5 million apps were available for download,1 and more than 325,000 apps were health related.2 Much of the peer-reviewed literature on health-related apps has focused on apps that target patients. Therefore, we studied apps for health care providers, specifically dermatology residents of different sexes throughout residency. We investigated the role of apps in their training, including how often residents consult apps, which apps they utilize, and why.

Methods

An original online survey regarding mobile apps was emailed to all 1587 dermatology residents in America by the American Academy of Dermatology from summer 2019 to summer 2020. Responses were anonymous, voluntary, unincentivized, and collected over 17 days. To protect respondent privacy, minimal data were collected regarding training programs; geography served as a proxy for how resource rich or resource poor those programs may be. Categorization of urban vs rural was based on the 2010 Census classification, such that Arizona; California; Colorado; Connecticut; Florida; Illinois; Maryland; Massachusetts; New Jersey; New York; Oregon; Puerto Rico; Rhode Island; Texas; Utah; and Washington, DC, were urban, and the remaining states were rural.3

We hypothesized that VisualDx would be 1 of 3 most prevalent apps; “diagnosis and workup” and “self-education” would be top reasons for using apps; “up-to-date and accurate information” would be a top 3 consideration when choosing apps; the most consulted resources for clinical experiences would be providers, followed by websites, apps, and lastly printed text; and the percentage of clinical experiences for which a provider was consulted would be higher for first-year residents than other years and for female residents than male residents.

Fisher exact 2-tailed and Kruskal-Wallis (KW) pairwise tests were used to compare groups. Statistical significance was set at P<.05.

Results

Respondents

The response rate was 16.6% (n=263), which is similar to prior response rates for American Academy of Dermatology surveys. Table 1 contains respondent demographics. The mean age of respondents was 31 years. Sixty percent of respondents were female; 62% of respondents were training in urban states or territories. Regarding the dermatology residency year, 34% of respondents were in their first year, 32% were in their second, and 34% were in their third. Eighty-seven percent of respondents used Apple iOS. Every respondent used at least 1 dermatology-related app (mean, 5; range, 1–11)(Table 2).

Top Dermatology-Related Apps

The 10 most prevalent apps are listed in Table 2. The 3 most prevalent apps were VisualDx (84%, majority of respondents used daily), UpToDate (67%, majority of respondents used daily), and Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria (63%, majority of respondents used weekly). A higher percentage of third-year residents used GoodRx compared to first- and second-year residents (Fisher exact test: P=.014 and P=.041, respectively). A lower percentage of female respondents used GoodRx compared to male residents (Fisher exact test: P=.003). None of the apps were app versions of printed text, including textbooks or journals.

Reasons for Using Apps

The 10 primary reasons for using apps are listed in Table 2. The top 3 reasons were diagnosis and workup (83%), medication dosage (72%), and self-education (69%). Medication dosage and saving time were both selected by a higher percentage of third-year residents than first-year residents (Fisher exact test: P=.041 and P=.024, respectively). Self-education was selected by a lower percentage of third-year residents than second-year residents (Fisher exact test: P=.025).

Considerations When Choosing Apps

The 10 primary considerations when choosing apps are listed in Table 2. The top 3 considerations were up-to-date and accurate information (81%), no/low cost (80%), and user-friendly design (74%). Up-to-date and accurate information was selected by a lower percentage of third-year residents than first- and second-year residents (Fisher exact test: P=.02 and P=.03, respectively).

Consulted Resources

Apps were the second most consulted resource (26%) during clinical work, behind human guidance (73%). Female respondents consulted both resources more than male respondents (KW: P≤.005 and P≤.003, respectively). First-year residents consulted humans more than second-year and third-year residents (KW: P<.0001).

There were no significant differences by geography or mobile operating system.

Comment

The response rate and demographic results suggest that our study sample is representative of the target population of dermatology residents in America. Overall, the survey results support our hypotheses.

A survey conducted in 2008 before apps were readily available found that dermatology residents felt they learned more successfully when engaging in hands-on, direct experience; talking with experts/consultants; and studying printed materials than when using multimedia programs.4 Our study suggests that the usage of and preference for multimedia programs, including apps, in dermatology resident training has risen substantially, despite the continued availability of guidance from attendings and senior residents.

As residents progress through training, they increasingly turn to virtual resources. According to our survey, junior residents are more likely than third-year residents to use apps for self-education, and up-to-date and accurate information was a more important consideration when choosing apps. Third-year residents are more likely than junior residents to use apps for medication dosage and saving time. Perhaps related, GoodRx, an app that provides prescription discounts, was more prevalent among third-year residents. It is notable that most of the reported apps, including those used for diagnosis and treatment, did not need premarket government approval to ensure patient safety, are not required to contain up-to-date information, and do not reference primary sources. Additionally, only UpToDate has been shown in peer-reviewed literature to improve clinical outcomes.5

Our survey also revealed a few differences by sex. Female respondents consulted resources during clinical work more often than male residents. This finding is similar to the limited existing research on dermatologists’ utilization of information showing higher dermoscopy use among female attendings.6 Use of GoodRx was less prevalent among female vs male respondents. Perhaps related, a 2011 study found that female primary care physicians are less likely to prescribe medications than their male counterparts.7

Our study had several limitations. There may have been selection bias such that the residents who chose to participate were relatively more interested in mobile health. Certain demographic data, such as race, were not captured because prior studies do not suggest disparity by those demographics for mobile health utilization among residents, but those data could be incorporated into future studies. Our survey was intentionally limited in scope. For example, it did not capture the amount of time spent on each consult resource or the motivations for consulting an app instead of a provider.

Conclusion

A main objective of residency is to train new physicians to provide excellent patient care. Our survey highlights the increasing role of apps in dermatology residency, different priorities among years of residency, and different information utilization between sexes. This knowledge should encourage and help guide standardization and quality assurance of virtual residency education and integration of virtual resources into formal curricula. Residency administrators and residents should be aware of the apps used to learn and deliver care, consider the evidence for and regulation of those apps, and evaluate the accessibility and approachability of attendings to residents. Future research should examine the educational and clinical outcomes of app utilization among residents and the impact of residency programs’ unspoken cultures and expectations on relationships among residents of different demographics and their attendings.

- Statistica. Number of apps available in leading app stores 2020. Accessed September 21, 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/276623/number-of-apps-available-in-leading-app-stores/

- Research2Guidance. mHealth economics 2017—current status and future trends in mobile health. Accessed July 16, 2021. https://research2guidance.com/product/mhealth-economics-2017-current-status-and-future-trends-in-mobile-health/

- United States Census Bureau. 2010 Census Urban and Rural Classification and Urban Area Criteria. Accessed September 21, 2020. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/geography/guidance/geo-areas/urban-rural/2010-urban-rural.html

- Stratman EJ, Vogel CA, Reck SJ, et al. Analysis of dermatology resident self-reported successful learning styles and implications for core competency curriculum development. Med Teach. 2008;30:420-425.

- Wolters Kluwer. UpToDate is the only clinical decision support resource associated with improved outcomes. Accessed July 22, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/home/research

- Engasser HC, Warshaw EM. Dermatoscopy use by US dermatologists: a cross-sectional survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:412-419.

- Smith AW, Borowski LA, Liu B, et al. U.S. primary care physicians’ diet-, physical activity–, and weight-related care of adult patients. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41:33-42. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.03.017

- Statistica. Number of apps available in leading app stores 2020. Accessed September 21, 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/276623/number-of-apps-available-in-leading-app-stores/

- Research2Guidance. mHealth economics 2017—current status and future trends in mobile health. Accessed July 16, 2021. https://research2guidance.com/product/mhealth-economics-2017-current-status-and-future-trends-in-mobile-health/

- United States Census Bureau. 2010 Census Urban and Rural Classification and Urban Area Criteria. Accessed September 21, 2020. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/geography/guidance/geo-areas/urban-rural/2010-urban-rural.html

- Stratman EJ, Vogel CA, Reck SJ, et al. Analysis of dermatology resident self-reported successful learning styles and implications for core competency curriculum development. Med Teach. 2008;30:420-425.

- Wolters Kluwer. UpToDate is the only clinical decision support resource associated with improved outcomes. Accessed July 22, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/home/research

- Engasser HC, Warshaw EM. Dermatoscopy use by US dermatologists: a cross-sectional survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:412-419.

- Smith AW, Borowski LA, Liu B, et al. U.S. primary care physicians’ diet-, physical activity–, and weight-related care of adult patients. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41:33-42. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.03.017

Practice Points

- Virtual resources, including mobile apps, have become critical tools for learning and patient care during dermatology resident training for reasons that should be elucidated.

- Dermatology residents of different years and sexes utilize mobile apps in different amounts and for different purposes.