User login

Noise and Light Pollution in the Hospital: A Call for Action

“Unnecessary noise is the most cruel abuse of care which can be inflicted on either the sick or the well.”

–Florence Nightingale1

Motivated by the “unsustainable” rise in noise pollution and its “direct, as well as cumulative, adverse health effects,” an expert World Health Organization (WHO) task force composed the Guidelines for Community Noise, outlining specific noise recommendations for public settings, including hospitals.2 In ward settings, these guidelines mandate that background noise (which is defined as unwanted sound) levels average <35 decibels (dB; ie, a typical library) during the day, average <30 dB at night, and peak no higher than 40 dB (ie, a normal conversation), a level sufficient to awaken someone from sleep.

Since the publication of these guidelines in 1999, substantial new research has added to our understanding of hospital noise levels. Recent research has demonstrated that few, if any, hospitals comply with WHO noise recommendations.3 Moreover, since 1960, hospital sound levels have risen ~4 dB per decade; based on the logarithmic decibel scale, if this trend continues, this translates to a 528% increase in loudness by 2020.3

The overwhelming majority of research on hospital noise has focused on the intensive care unit (ICU), where beeping machines and busy staff often push peak nighttime noise levels over 80 dB (ie, a kitchen blender).4 When evaluated during sleep, noise in the ICU causes frequent arousals and awakenings. When noise is combined with other factors, such as bright light and patient care interactions, poor sleep quality invariably results.4

While it has been known for years that critically ill patients experience markedly fragmented and nonrestorative sleep,5 poor sleep has recently gained attention due to its potential role as a modifiable risk factor for delirium and its associated consequences, including prolonged length of stay and long-lasting neuropsychological and physical impairments.6 Due to this interest, numerous interventions have been attempted,7 including multicomponent bundles to promote sleep,8 which have been shown to reduce delirium in the ICU.9-12 Therefore, efforts to promote sleep in the ICU, including interventions to minimize nighttime noise, are recommended in Society of Critical Care Medicine clinical practice guidelines13 and are listed as a top 5 research priority by an expert panel of ICU delirium researchers.14

In contrast to the ICU, there has been little attention paid to noise in other patient care areas. Existing studies in non-ICU ward settings suggest that excessive noise is common,3 similar to the ICU, and that patients experience poor sleep, with noise being a significant disruptor of sleep.5,15,16 Such poor sleep is thought to contribute to uncontrolled pain, labile blood pressure, and dissatisfaction with care.16,17

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Jaiswal and colleagues18 report on an important study evaluating sound and light levels in both non-ICU and ICU settings within a busy tertiary-care hospital. In 8 general ward, 8 telemetry, and 8 ICU patient rooms, the investigators used meters to record sound and light levels for 24 to 72 hours. In each of these locations, they detected average hourly sound levels ranging from 45 to 54 dB, 47 to 55 dB, and 56 to 60 dB, respectively, with ICUs consistently registering the highest hourly sound levels. Notably, all locations exceeded WHO noise limits at all hours of the day. As a novel measure, the investigators evaluated sound level changes (SLCs), or the difference between peak and background sound levels, based on research suggesting that dramatic SLCs (≥17.5 dB) are more disruptive than constant loud noise.19 The authors observed that SLCs ≥17.5 dB occur predominantly during daytime hours and, interestingly, at a similar rate in the wards versus the ICU.

Importantly, the authors do not link their findings with patient sleep or other patient outcomes but instead focus on employing rigorous methods to gather continuous recordings. By measuring light levels, the authors bring attention to an issue often considered less disruptive to sleep than noise.6,10,20 Similar to prior research,21 Jaiswal and colleagues demonstrate low levels of light at night, with no substantial difference between non-ICU and ICU settings. As a key finding, the authors bring attention to low levels of light during daytime hours, particularly in the morning, when levels range from 22 to 101 lux in the wards and 16 to 39 lux in the ICU. While the optimal timing and brightness of light exposure remains unknown, it is well established that ambient light is the most potent cue for circadian rhythms, with levels >100 lux necessary to suppress melatonin, the key hormone involved in circadian entrainment. Hence, the levels of morning light observed in this study were likely insufficient to maintain healthy circadian rhythms. When exposed to abnormal light levels and factors such as noise, stress, and medications, hospitalized patients are at risk for circadian rhythm misalignment, which can disrupt sleep and trigger a complex molecular cascade, leading to end-organ dysfunction including depressed immunity, glucose dysregulation, arrhythmias, and delirium.22-24

What are the major takeaway messages from this study? First, it confirms that sound levels are not only high in the ICU but also in non-ICU wards. As hospital ratings and reimbursements now rely on favorable patient ratings, future noise-reduction efforts will surely expand more vigorously across patient care areas.25 Second, SLCs and daytime recordings must be included in efforts to understand and improve sleep and circadian rhythms in hospitalized patients. Finally, this study provides a sobering reminder of the challenge of meeting WHO guidelines and facilitating an optimal healing environment for patients. Sadly, hospital sound levels continue to rise, and quiet-time interventions consistently fail to lower noise to levels anywhere near WHO limits.26 Hence, to make any progress, hospitals of the future must entertain novel design modifications (eg, sound-absorbing walls and alternative room layouts), fix common sources of noise pollution (eg, ventilation systems and alarms), and critically evaluate and update interventions aimed at improving sleep and aligning circadian rhythms for hospitalized patients.27

Acknowledgments

B.B.K. is currently supported by a grant through the University of California, Los Angeles Clinical Translational Research Institute and the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000124).

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Nightingale F. Notes on Nursing: What It Is, and What It Is Not. Harrison; 1860. PubMed

2. Berglund B, Lindvall T, Schwela DH. Guidelines for Community Noise. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1999. http://www.who.int/docstore/peh/noise/guidelines2.html. Accessed on June 23, 2017.

3. Busch-Vishniac IJ, West JE, Barnhill C, Hunter T, Orellana D, Chivukula R. Noise levels in Johns Hopkins Hospital. J Acoust Soc Am. 2005;118(6):3629-3645. PubMed

4. Kamdar BB, Needham DM, Collop NA. Sleep deprivation in critical illness: its role in physical and psychological recovery. J Intensive Care Med. 2012;27(2):97-111. PubMed

5. Knauert MP, Malik V, Kamdar BB. Sleep and sleep disordered breathing in hospitalized patients. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;35(5):582-592. PubMed

6. Kamdar BB, Knauert MP, Jones SF, et al. Perceptions and practices regarding sleep in the intensive care unit. A survey of 1,223 critical care providers. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(8):1370-1377. PubMed

7. DuBose JR, Hadi K. Improving inpatient environments to support patient sleep. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(5):540-553. PubMed

8. Kamdar BB, Kamdar BB, Needham DM. Bundling sleep promotion with delirium prevention: ready for prime time? Anaesthesia. 2014;69(6):527-531. PubMed

9. Patel J, Baldwin J, Bunting P, Laha S. The effect of a multicomponent multidisciplinary bundle of interventions on sleep and delirium in medical and surgical intensive care patients. Anaesthesia. 2014;69(6):540-549. PubMed

10. Kamdar BB, King LM, Collop NA, et al. The effect of a quality improvement intervention on perceived sleep quality and cognition in a medical ICU. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(3):800-809. PubMed

11. van de Pol I, van Iterson M, Maaskant J. Effect of nocturnal sound reduction on the incidence of delirium in intensive care unit patients: An interrupted time series analysis. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2017;41:18-25. PubMed

12. Flannery AH, Oyler DR, Weinhouse GL. The impact of interventions to improve sleep on delirium in the ICU: a systematic review and research framework. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(12):2231-2240. PubMed

13. Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(1):263-306. PubMed

14. Pandharipande PP, Ely EW, Arora RC, et al. The intensive care delirium research agenda: a multinational, interprofessional perspective [published online ahead of print June 13, 2017]. Intensive Care Med. PubMed

15. Topf M, Thompson S. Interactive relationships between hospital patients’ noise-induced stress and other stress with sleep. Heart Lung. 2001;30(4):237-243. PubMed

16. Tamrat R, Huynh-Le MP, Goyal M. Non-pharmacologic interventions to improve the sleep of hospitalized patients: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(5):788-795. PubMed

17. Fillary J, Chaplin H, Jones G, Thompson A, Holme A, Wilson P. Noise at night in hospital general wards: a mapping of the literature. Br J Nurs. 2015;24(10):536-540. PubMed

18. Jaiswal SJ, Garcia S, Owens RL. Sound and light levels are similarly disruptive in ICU and non-ICU wards. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(10):798-804. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2826.

19. Stanchina ML, Abu-Hijleh M, Chaudhry BK, Carlisle CC, Millman RP. The influence of white noise on sleep in subjects exposed to ICU noise. Sleep Med. 2005;6(5):423-428. PubMed

20. Freedman NS, Kotzer N, Schwab RJ. Patient perception of sleep quality and etiology of sleep disruption in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(4, Pt 1):1155-1162. PubMed

21. Meyer TJ, Eveloff SE, Bauer MS, Schwartz WA, Hill NS, Millman RP. Adverse environmental conditions in the respiratory and medical ICU settings. Chest. 1994;105(4):1211-1216. PubMed

22. Castro R, Angus DC, Rosengart MR. The effect of light on critical illness. Crit Care. 2011;15(2):218. PubMed

23. Brainard J, Gobel M, Scott B, Koeppen M, Eckle T. Health implications of disrupted circadian rhythms and the potential for daylight as therapy. Anesthesiology. 2015;122(5):1170-1175. PubMed

24. Fitzgerald JM, Adamis D, Trzepacz PT, et al. Delirium: a disturbance of circadian integrity? Med Hypotheses. 2013;81(4):568-576. PubMed

25. Stafford A, Haverland A, Bridges E. Noise in the ICU. Am J Nurs. 2014;114(5):57-63. PubMed

26. Tainter CR, Levine AR, Quraishi SA, et al. Noise levels in surgical ICUs are consistently above recommended standards. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(1):147-152. PubMed

27. Ulrich RS, Zimring C, Zhu X, et al. A review of the research literature on evidence-based healthcare design. HERD. 2008;1(3):61-125. PubMed

“Unnecessary noise is the most cruel abuse of care which can be inflicted on either the sick or the well.”

–Florence Nightingale1

Motivated by the “unsustainable” rise in noise pollution and its “direct, as well as cumulative, adverse health effects,” an expert World Health Organization (WHO) task force composed the Guidelines for Community Noise, outlining specific noise recommendations for public settings, including hospitals.2 In ward settings, these guidelines mandate that background noise (which is defined as unwanted sound) levels average <35 decibels (dB; ie, a typical library) during the day, average <30 dB at night, and peak no higher than 40 dB (ie, a normal conversation), a level sufficient to awaken someone from sleep.

Since the publication of these guidelines in 1999, substantial new research has added to our understanding of hospital noise levels. Recent research has demonstrated that few, if any, hospitals comply with WHO noise recommendations.3 Moreover, since 1960, hospital sound levels have risen ~4 dB per decade; based on the logarithmic decibel scale, if this trend continues, this translates to a 528% increase in loudness by 2020.3

The overwhelming majority of research on hospital noise has focused on the intensive care unit (ICU), where beeping machines and busy staff often push peak nighttime noise levels over 80 dB (ie, a kitchen blender).4 When evaluated during sleep, noise in the ICU causes frequent arousals and awakenings. When noise is combined with other factors, such as bright light and patient care interactions, poor sleep quality invariably results.4

While it has been known for years that critically ill patients experience markedly fragmented and nonrestorative sleep,5 poor sleep has recently gained attention due to its potential role as a modifiable risk factor for delirium and its associated consequences, including prolonged length of stay and long-lasting neuropsychological and physical impairments.6 Due to this interest, numerous interventions have been attempted,7 including multicomponent bundles to promote sleep,8 which have been shown to reduce delirium in the ICU.9-12 Therefore, efforts to promote sleep in the ICU, including interventions to minimize nighttime noise, are recommended in Society of Critical Care Medicine clinical practice guidelines13 and are listed as a top 5 research priority by an expert panel of ICU delirium researchers.14

In contrast to the ICU, there has been little attention paid to noise in other patient care areas. Existing studies in non-ICU ward settings suggest that excessive noise is common,3 similar to the ICU, and that patients experience poor sleep, with noise being a significant disruptor of sleep.5,15,16 Such poor sleep is thought to contribute to uncontrolled pain, labile blood pressure, and dissatisfaction with care.16,17

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Jaiswal and colleagues18 report on an important study evaluating sound and light levels in both non-ICU and ICU settings within a busy tertiary-care hospital. In 8 general ward, 8 telemetry, and 8 ICU patient rooms, the investigators used meters to record sound and light levels for 24 to 72 hours. In each of these locations, they detected average hourly sound levels ranging from 45 to 54 dB, 47 to 55 dB, and 56 to 60 dB, respectively, with ICUs consistently registering the highest hourly sound levels. Notably, all locations exceeded WHO noise limits at all hours of the day. As a novel measure, the investigators evaluated sound level changes (SLCs), or the difference between peak and background sound levels, based on research suggesting that dramatic SLCs (≥17.5 dB) are more disruptive than constant loud noise.19 The authors observed that SLCs ≥17.5 dB occur predominantly during daytime hours and, interestingly, at a similar rate in the wards versus the ICU.

Importantly, the authors do not link their findings with patient sleep or other patient outcomes but instead focus on employing rigorous methods to gather continuous recordings. By measuring light levels, the authors bring attention to an issue often considered less disruptive to sleep than noise.6,10,20 Similar to prior research,21 Jaiswal and colleagues demonstrate low levels of light at night, with no substantial difference between non-ICU and ICU settings. As a key finding, the authors bring attention to low levels of light during daytime hours, particularly in the morning, when levels range from 22 to 101 lux in the wards and 16 to 39 lux in the ICU. While the optimal timing and brightness of light exposure remains unknown, it is well established that ambient light is the most potent cue for circadian rhythms, with levels >100 lux necessary to suppress melatonin, the key hormone involved in circadian entrainment. Hence, the levels of morning light observed in this study were likely insufficient to maintain healthy circadian rhythms. When exposed to abnormal light levels and factors such as noise, stress, and medications, hospitalized patients are at risk for circadian rhythm misalignment, which can disrupt sleep and trigger a complex molecular cascade, leading to end-organ dysfunction including depressed immunity, glucose dysregulation, arrhythmias, and delirium.22-24

What are the major takeaway messages from this study? First, it confirms that sound levels are not only high in the ICU but also in non-ICU wards. As hospital ratings and reimbursements now rely on favorable patient ratings, future noise-reduction efforts will surely expand more vigorously across patient care areas.25 Second, SLCs and daytime recordings must be included in efforts to understand and improve sleep and circadian rhythms in hospitalized patients. Finally, this study provides a sobering reminder of the challenge of meeting WHO guidelines and facilitating an optimal healing environment for patients. Sadly, hospital sound levels continue to rise, and quiet-time interventions consistently fail to lower noise to levels anywhere near WHO limits.26 Hence, to make any progress, hospitals of the future must entertain novel design modifications (eg, sound-absorbing walls and alternative room layouts), fix common sources of noise pollution (eg, ventilation systems and alarms), and critically evaluate and update interventions aimed at improving sleep and aligning circadian rhythms for hospitalized patients.27

Acknowledgments

B.B.K. is currently supported by a grant through the University of California, Los Angeles Clinical Translational Research Institute and the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000124).

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

“Unnecessary noise is the most cruel abuse of care which can be inflicted on either the sick or the well.”

–Florence Nightingale1

Motivated by the “unsustainable” rise in noise pollution and its “direct, as well as cumulative, adverse health effects,” an expert World Health Organization (WHO) task force composed the Guidelines for Community Noise, outlining specific noise recommendations for public settings, including hospitals.2 In ward settings, these guidelines mandate that background noise (which is defined as unwanted sound) levels average <35 decibels (dB; ie, a typical library) during the day, average <30 dB at night, and peak no higher than 40 dB (ie, a normal conversation), a level sufficient to awaken someone from sleep.

Since the publication of these guidelines in 1999, substantial new research has added to our understanding of hospital noise levels. Recent research has demonstrated that few, if any, hospitals comply with WHO noise recommendations.3 Moreover, since 1960, hospital sound levels have risen ~4 dB per decade; based on the logarithmic decibel scale, if this trend continues, this translates to a 528% increase in loudness by 2020.3

The overwhelming majority of research on hospital noise has focused on the intensive care unit (ICU), where beeping machines and busy staff often push peak nighttime noise levels over 80 dB (ie, a kitchen blender).4 When evaluated during sleep, noise in the ICU causes frequent arousals and awakenings. When noise is combined with other factors, such as bright light and patient care interactions, poor sleep quality invariably results.4

While it has been known for years that critically ill patients experience markedly fragmented and nonrestorative sleep,5 poor sleep has recently gained attention due to its potential role as a modifiable risk factor for delirium and its associated consequences, including prolonged length of stay and long-lasting neuropsychological and physical impairments.6 Due to this interest, numerous interventions have been attempted,7 including multicomponent bundles to promote sleep,8 which have been shown to reduce delirium in the ICU.9-12 Therefore, efforts to promote sleep in the ICU, including interventions to minimize nighttime noise, are recommended in Society of Critical Care Medicine clinical practice guidelines13 and are listed as a top 5 research priority by an expert panel of ICU delirium researchers.14

In contrast to the ICU, there has been little attention paid to noise in other patient care areas. Existing studies in non-ICU ward settings suggest that excessive noise is common,3 similar to the ICU, and that patients experience poor sleep, with noise being a significant disruptor of sleep.5,15,16 Such poor sleep is thought to contribute to uncontrolled pain, labile blood pressure, and dissatisfaction with care.16,17

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Jaiswal and colleagues18 report on an important study evaluating sound and light levels in both non-ICU and ICU settings within a busy tertiary-care hospital. In 8 general ward, 8 telemetry, and 8 ICU patient rooms, the investigators used meters to record sound and light levels for 24 to 72 hours. In each of these locations, they detected average hourly sound levels ranging from 45 to 54 dB, 47 to 55 dB, and 56 to 60 dB, respectively, with ICUs consistently registering the highest hourly sound levels. Notably, all locations exceeded WHO noise limits at all hours of the day. As a novel measure, the investigators evaluated sound level changes (SLCs), or the difference between peak and background sound levels, based on research suggesting that dramatic SLCs (≥17.5 dB) are more disruptive than constant loud noise.19 The authors observed that SLCs ≥17.5 dB occur predominantly during daytime hours and, interestingly, at a similar rate in the wards versus the ICU.

Importantly, the authors do not link their findings with patient sleep or other patient outcomes but instead focus on employing rigorous methods to gather continuous recordings. By measuring light levels, the authors bring attention to an issue often considered less disruptive to sleep than noise.6,10,20 Similar to prior research,21 Jaiswal and colleagues demonstrate low levels of light at night, with no substantial difference between non-ICU and ICU settings. As a key finding, the authors bring attention to low levels of light during daytime hours, particularly in the morning, when levels range from 22 to 101 lux in the wards and 16 to 39 lux in the ICU. While the optimal timing and brightness of light exposure remains unknown, it is well established that ambient light is the most potent cue for circadian rhythms, with levels >100 lux necessary to suppress melatonin, the key hormone involved in circadian entrainment. Hence, the levels of morning light observed in this study were likely insufficient to maintain healthy circadian rhythms. When exposed to abnormal light levels and factors such as noise, stress, and medications, hospitalized patients are at risk for circadian rhythm misalignment, which can disrupt sleep and trigger a complex molecular cascade, leading to end-organ dysfunction including depressed immunity, glucose dysregulation, arrhythmias, and delirium.22-24

What are the major takeaway messages from this study? First, it confirms that sound levels are not only high in the ICU but also in non-ICU wards. As hospital ratings and reimbursements now rely on favorable patient ratings, future noise-reduction efforts will surely expand more vigorously across patient care areas.25 Second, SLCs and daytime recordings must be included in efforts to understand and improve sleep and circadian rhythms in hospitalized patients. Finally, this study provides a sobering reminder of the challenge of meeting WHO guidelines and facilitating an optimal healing environment for patients. Sadly, hospital sound levels continue to rise, and quiet-time interventions consistently fail to lower noise to levels anywhere near WHO limits.26 Hence, to make any progress, hospitals of the future must entertain novel design modifications (eg, sound-absorbing walls and alternative room layouts), fix common sources of noise pollution (eg, ventilation systems and alarms), and critically evaluate and update interventions aimed at improving sleep and aligning circadian rhythms for hospitalized patients.27

Acknowledgments

B.B.K. is currently supported by a grant through the University of California, Los Angeles Clinical Translational Research Institute and the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000124).

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Nightingale F. Notes on Nursing: What It Is, and What It Is Not. Harrison; 1860. PubMed

2. Berglund B, Lindvall T, Schwela DH. Guidelines for Community Noise. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1999. http://www.who.int/docstore/peh/noise/guidelines2.html. Accessed on June 23, 2017.

3. Busch-Vishniac IJ, West JE, Barnhill C, Hunter T, Orellana D, Chivukula R. Noise levels in Johns Hopkins Hospital. J Acoust Soc Am. 2005;118(6):3629-3645. PubMed

4. Kamdar BB, Needham DM, Collop NA. Sleep deprivation in critical illness: its role in physical and psychological recovery. J Intensive Care Med. 2012;27(2):97-111. PubMed

5. Knauert MP, Malik V, Kamdar BB. Sleep and sleep disordered breathing in hospitalized patients. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;35(5):582-592. PubMed

6. Kamdar BB, Knauert MP, Jones SF, et al. Perceptions and practices regarding sleep in the intensive care unit. A survey of 1,223 critical care providers. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(8):1370-1377. PubMed

7. DuBose JR, Hadi K. Improving inpatient environments to support patient sleep. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(5):540-553. PubMed

8. Kamdar BB, Kamdar BB, Needham DM. Bundling sleep promotion with delirium prevention: ready for prime time? Anaesthesia. 2014;69(6):527-531. PubMed

9. Patel J, Baldwin J, Bunting P, Laha S. The effect of a multicomponent multidisciplinary bundle of interventions on sleep and delirium in medical and surgical intensive care patients. Anaesthesia. 2014;69(6):540-549. PubMed

10. Kamdar BB, King LM, Collop NA, et al. The effect of a quality improvement intervention on perceived sleep quality and cognition in a medical ICU. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(3):800-809. PubMed

11. van de Pol I, van Iterson M, Maaskant J. Effect of nocturnal sound reduction on the incidence of delirium in intensive care unit patients: An interrupted time series analysis. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2017;41:18-25. PubMed

12. Flannery AH, Oyler DR, Weinhouse GL. The impact of interventions to improve sleep on delirium in the ICU: a systematic review and research framework. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(12):2231-2240. PubMed

13. Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(1):263-306. PubMed

14. Pandharipande PP, Ely EW, Arora RC, et al. The intensive care delirium research agenda: a multinational, interprofessional perspective [published online ahead of print June 13, 2017]. Intensive Care Med. PubMed

15. Topf M, Thompson S. Interactive relationships between hospital patients’ noise-induced stress and other stress with sleep. Heart Lung. 2001;30(4):237-243. PubMed

16. Tamrat R, Huynh-Le MP, Goyal M. Non-pharmacologic interventions to improve the sleep of hospitalized patients: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(5):788-795. PubMed

17. Fillary J, Chaplin H, Jones G, Thompson A, Holme A, Wilson P. Noise at night in hospital general wards: a mapping of the literature. Br J Nurs. 2015;24(10):536-540. PubMed

18. Jaiswal SJ, Garcia S, Owens RL. Sound and light levels are similarly disruptive in ICU and non-ICU wards. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(10):798-804. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2826.

19. Stanchina ML, Abu-Hijleh M, Chaudhry BK, Carlisle CC, Millman RP. The influence of white noise on sleep in subjects exposed to ICU noise. Sleep Med. 2005;6(5):423-428. PubMed

20. Freedman NS, Kotzer N, Schwab RJ. Patient perception of sleep quality and etiology of sleep disruption in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(4, Pt 1):1155-1162. PubMed

21. Meyer TJ, Eveloff SE, Bauer MS, Schwartz WA, Hill NS, Millman RP. Adverse environmental conditions in the respiratory and medical ICU settings. Chest. 1994;105(4):1211-1216. PubMed

22. Castro R, Angus DC, Rosengart MR. The effect of light on critical illness. Crit Care. 2011;15(2):218. PubMed

23. Brainard J, Gobel M, Scott B, Koeppen M, Eckle T. Health implications of disrupted circadian rhythms and the potential for daylight as therapy. Anesthesiology. 2015;122(5):1170-1175. PubMed

24. Fitzgerald JM, Adamis D, Trzepacz PT, et al. Delirium: a disturbance of circadian integrity? Med Hypotheses. 2013;81(4):568-576. PubMed

25. Stafford A, Haverland A, Bridges E. Noise in the ICU. Am J Nurs. 2014;114(5):57-63. PubMed

26. Tainter CR, Levine AR, Quraishi SA, et al. Noise levels in surgical ICUs are consistently above recommended standards. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(1):147-152. PubMed

27. Ulrich RS, Zimring C, Zhu X, et al. A review of the research literature on evidence-based healthcare design. HERD. 2008;1(3):61-125. PubMed

1. Nightingale F. Notes on Nursing: What It Is, and What It Is Not. Harrison; 1860. PubMed

2. Berglund B, Lindvall T, Schwela DH. Guidelines for Community Noise. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1999. http://www.who.int/docstore/peh/noise/guidelines2.html. Accessed on June 23, 2017.

3. Busch-Vishniac IJ, West JE, Barnhill C, Hunter T, Orellana D, Chivukula R. Noise levels in Johns Hopkins Hospital. J Acoust Soc Am. 2005;118(6):3629-3645. PubMed

4. Kamdar BB, Needham DM, Collop NA. Sleep deprivation in critical illness: its role in physical and psychological recovery. J Intensive Care Med. 2012;27(2):97-111. PubMed

5. Knauert MP, Malik V, Kamdar BB. Sleep and sleep disordered breathing in hospitalized patients. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;35(5):582-592. PubMed

6. Kamdar BB, Knauert MP, Jones SF, et al. Perceptions and practices regarding sleep in the intensive care unit. A survey of 1,223 critical care providers. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(8):1370-1377. PubMed

7. DuBose JR, Hadi K. Improving inpatient environments to support patient sleep. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(5):540-553. PubMed

8. Kamdar BB, Kamdar BB, Needham DM. Bundling sleep promotion with delirium prevention: ready for prime time? Anaesthesia. 2014;69(6):527-531. PubMed

9. Patel J, Baldwin J, Bunting P, Laha S. The effect of a multicomponent multidisciplinary bundle of interventions on sleep and delirium in medical and surgical intensive care patients. Anaesthesia. 2014;69(6):540-549. PubMed

10. Kamdar BB, King LM, Collop NA, et al. The effect of a quality improvement intervention on perceived sleep quality and cognition in a medical ICU. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(3):800-809. PubMed

11. van de Pol I, van Iterson M, Maaskant J. Effect of nocturnal sound reduction on the incidence of delirium in intensive care unit patients: An interrupted time series analysis. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2017;41:18-25. PubMed

12. Flannery AH, Oyler DR, Weinhouse GL. The impact of interventions to improve sleep on delirium in the ICU: a systematic review and research framework. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(12):2231-2240. PubMed

13. Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(1):263-306. PubMed

14. Pandharipande PP, Ely EW, Arora RC, et al. The intensive care delirium research agenda: a multinational, interprofessional perspective [published online ahead of print June 13, 2017]. Intensive Care Med. PubMed

15. Topf M, Thompson S. Interactive relationships between hospital patients’ noise-induced stress and other stress with sleep. Heart Lung. 2001;30(4):237-243. PubMed

16. Tamrat R, Huynh-Le MP, Goyal M. Non-pharmacologic interventions to improve the sleep of hospitalized patients: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(5):788-795. PubMed

17. Fillary J, Chaplin H, Jones G, Thompson A, Holme A, Wilson P. Noise at night in hospital general wards: a mapping of the literature. Br J Nurs. 2015;24(10):536-540. PubMed

18. Jaiswal SJ, Garcia S, Owens RL. Sound and light levels are similarly disruptive in ICU and non-ICU wards. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(10):798-804. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2826.

19. Stanchina ML, Abu-Hijleh M, Chaudhry BK, Carlisle CC, Millman RP. The influence of white noise on sleep in subjects exposed to ICU noise. Sleep Med. 2005;6(5):423-428. PubMed

20. Freedman NS, Kotzer N, Schwab RJ. Patient perception of sleep quality and etiology of sleep disruption in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(4, Pt 1):1155-1162. PubMed

21. Meyer TJ, Eveloff SE, Bauer MS, Schwartz WA, Hill NS, Millman RP. Adverse environmental conditions in the respiratory and medical ICU settings. Chest. 1994;105(4):1211-1216. PubMed

22. Castro R, Angus DC, Rosengart MR. The effect of light on critical illness. Crit Care. 2011;15(2):218. PubMed

23. Brainard J, Gobel M, Scott B, Koeppen M, Eckle T. Health implications of disrupted circadian rhythms and the potential for daylight as therapy. Anesthesiology. 2015;122(5):1170-1175. PubMed

24. Fitzgerald JM, Adamis D, Trzepacz PT, et al. Delirium: a disturbance of circadian integrity? Med Hypotheses. 2013;81(4):568-576. PubMed

25. Stafford A, Haverland A, Bridges E. Noise in the ICU. Am J Nurs. 2014;114(5):57-63. PubMed

26. Tainter CR, Levine AR, Quraishi SA, et al. Noise levels in surgical ICUs are consistently above recommended standards. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(1):147-152. PubMed

27. Ulrich RS, Zimring C, Zhu X, et al. A review of the research literature on evidence-based healthcare design. HERD. 2008;1(3):61-125. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Promoting Mobility and Reducing LOS

Annually, more than 35 million patients are hospitalized in the United States, with many experiencing hospital‐acquired impairments in physical functioning during their in‐patient stay.[1, 2, 3, 4] Such impairments include difficulties performing basic activities of daily living, such as rising from a chair, toileting, or ambulating. This functional decline may result in increased length of stay (LOS), nursing home placement, and decreased mobility and participation in community activities even years after hospitalization.[1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7] Ameliorating this hospital‐acquired functional impairment is important to improving patient outcomes and reducing healthcare utilization. Even the sickest hospitalized patients (eg, those in the intensive care unit [ICU]), can safely and feasibly benefit from early mobilization.[6, 8, 9, 10, 11] In the non‐ICU setting there is also evidence that patient mobilization reduces LOS and hospital costs, while improving patient satisfaction and physical and psychological outcomes.[12, 13, 14, 15, 16] These studies are, however, difficult to replicate as part of routine clinical care, because they often do not present the details of how early mobility was incorporated into daily practice, require additional hospital resources (eg, specially trained providers or additional staff), or are focused only on a select patient population.

The Johns Hopkins medical ICU started early rehabilitation quality‐improvement (QI) work in 2007, which has demonstrated ongoing reductions in LOS and been transformative in terms of helping to foster a culture of mobility at our institution. Previous research suggests that ICU‐based rehabilitation interventions are often not carried over to the ward setting, even in post‐ICU patients.[17] Moreover, trends for sicker patients being admitted in our general medicine units,[18] growing reports of patients spending most of their time in bed,[2, 19, 20] and healthcare policies emphasizing the importance of improving inpatient outcomes motivated the need for QI to improve patient mobility in this setting. Experience from the medical ICU‐based early rehabilitation program helped drive multidisciplinary collaboration of stakeholders to develop this nurse‐driven, mobility promotion QI project on 2 general medicine hospital units. The main goals of the project were to see whether a QI framework can be used in a general medicine setting to increase patient mobility and reduce LOS.[21, 22]

METHODS

Overview of Project

Mobility, for this project, was defined as a patient getting out of bed (eg, sitting out of bed, toileting at bedside commode or bathroom, standing, and ambulating). We aimed to increase patient mobility using preexisting unit staffing ratios of clinicians and support staff. This project was reported in accordance with the SQUIRE (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence) guidelines and used a structured QI model that had been used to successfully promote early mobility in the intensive care unit.[21, 23, 24, 25] The planning phase of the QI project began in spring 2012, with initiation of the 12‐month project on March 1, 2013. During the 12‐month QI period, prospective collection of mobility status occurred for all patients, with no exclusions based on patient characteristics.

Setting

The QI project setting was 2, 24‐bed, general medicine units at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, a large academic medical center located in Baltimore, Maryland.

QI Process

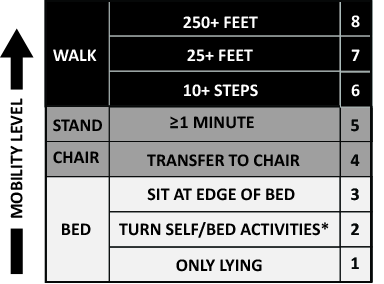

The primary goals of the QI project were to mobilize patients 3 times daily, quantify and document the mobility of the patients, set daily goals to increase mobility (eg, move up 1 step on the scale today), and standardize the description of patient mobility across all hospital staff. We used a structured QI model that that has been used to implement an early mobility program in a medical ICU at our institution[21, 22, 24] (see Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article). At a programmatic level, we involved key stakeholders (nurses, physicians, rehabilitation therapists, administrators) in the QI project team, we identified local barriers to implementation through team meetings as well as a survey tool to identify perceived barriers,[26] and we developed a scale (the Johns Hopkins Highest Level of Mobility [JH‐HLM]) to document mobility. The JH‐HLM is an 8‐point ordinal scale that captures mobility milestones, where 1 = only lying, 2 = bed activities, 3 = sit at edge of bed, 4 = transfer to chair/commode, 5 = standing for 1 minute, 6 = walking 10+ steps, 7 = walking 25+ feet, and 8 = walking 250+ feet (see Supporting Information, Appendix and Supporting Figure 1, in the online version of this article for additional information on the JH‐HLM scale).

The 12‐month QI project was characterized by several phases and milestones and involved a number of intervention components. During the first 4 months (ramp‐up phase), nurses received education in the form of unit‐based presentations, hands‐on‐training, and online education modules. On a 5‐times weekly basis, nurses met with rehabilitation therapists for unit‐based huddles to discuss baseline patient mobility, current patient mobility levels, barriers to mobilizing patients, and daily goals to progress mobility. Mobility levels were included on daily nursing report sheets to facilitate communication with subsequent shifts. Discussion of JH‐HLM scores also occurred during daily unit‐based care‐coordination meetings of the nurses, physicians, and social‐workers to address barriers to mobilizing patients, such as optimizing pain control, facilitating discharge location planning, and expediting physician consultation with physical and occupational therapy for appropriate patients. Audit and feedback from huddles and care‐coordination rounds resulted in improved nurse attendance and engagement during these meetings. Nurses were expected to document patient mobility scores using the JH‐HLM 3 times daily in the patient medical record. On the fourth month, reports on JH‐HLM scores and documentation compliance were available to nurse managers, champions, and unit staff. Via twice‐monthly meetings with the units and quarterly meetings with hospital leadership and administration, problems arising during the QI intervention were evaluated and resolved on a timely basis. Seven months after project execution started, educational sessions were repeated to all staff, and feedback was provided based on the data collected, such as documentation compliance rates and patient mobility levels, and nurse champions presented the project during an American Nurses Credentialing Center magnet recognition program visit. Lastly, mobility scores and documentation compliance were continually assessed for 4 months after the project completion to determine sustainability of the intervention. Additional details of the QI project implementation are provided in the Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article.

Data Sources and Covariates for Project Evaluation

The Sunrise Clinical Manager system (Allscripts Healthcare Solutions Inc., Chicago, IL) was used to document and extract nursing‐documented JH‐HLM scores. The Johns Hopkins Hospital Datamart financial database, used for mandatory reporting to the State of Maryland, provided data on LOS, age, sex, race (white, black, other), payer (Medicare, Medicaid, other), primary admission diagnosis, and comorbidity index using Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) methodology.[27] Expected LOS was calculated using the risk adjustment method developed by the University Health System Consortium (UHC).[28] This calculation uses a combination of the Diagnostic‐Related Group grouper and the Sachs Complication Profiler[29] in conjunction with data on specific patient characteristics (age, sex, urgency of admission, payer category) to construct risk‐adjustment regression models that assign expected values for LOS, and is not based on actual LOS.[28] The databases were linked at the patient level using the patient's medical record and unique admission record number.

Outcome Measures

Two functional outcome measures were based on daily JH‐HLM scores, which frequently occurred several times on each patient‐day: (1) the maximum daily JH‐HLM scores for each patient‐day during hospitalization, and (2) the intrapatient change in JH‐HLM scores between the maximum JH‐HLM score within 24 hours of hospital admission and 24 hours before discharge for all patients who were on the unit >48 hours. We also compared the mean LOS during the 12‐month QI project versus the 12‐months prior so we could more accurately address seasonal differences.[30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35] Lastly, because the perception of increased falls was an important barrier to address in the QI process, we compared the rate of injurious falls between the QI period and 12‐months prior.

Statistical Analysis

To evaluate changes in the percent of ambulatory patients (JH‐HLM 6), we compared the initial 4 months of the QI project (ramp‐up phase) with the same 4‐month period occurring immediately after project completion (post‐QI phase) using generalized estimating equations to account for clustering at the patient‐level. This test was also used to evaluate changes in documentation compliance rates between the 2 phases, with compliance defined as at least 1 instance of JH‐HLM documentation per day, excluding the day of admission and discharge. To evaluate if improved JH‐HLM results were driven by improved documentation compliance rates over time, we performed a sensitivity analysis by imputing a JH‐HLM score of 6 (ambulate 10+ steps) for any missing daily maximum JH‐HLM scores.

To assess unadjusted changes in LOS during the 12‐month QI project versus the same period 1 year earlier, we compared mean and median LOS using a t test and Wilcoxon rank sum test, respectively. We used a multivariable linear regression model to estimate the change (expressed in days) in adjusted median LOS comparing the project months (March 2013March 2014) with 12 months prior (March 2012March 2013). The model adjusted for age, gender, race, payer, admission diagnostic category, UHC expected LOS, and AHRQ comorbidity index. We confirmed a lack of multicollinearity in the multivariable regression model using variance inflation factors. We evaluated residual versus predicted value plots and residual versus fitted value plots with a locally weighted scatterplot smoothing line to confirm model fit. P values are reported from the test of the null hypothesis that the change in adjusted median LOS is the same comparing the QI project months versus 12 months prior. Separate models estimated and tested the change in adjusted median LOS by tertiles of expected LOS (<4, 47, and >7 days). Lastly, we compared the rate of injurious falls (the number of injurious falls by total patient‐days) between the QI period and 12 months prior using an exact Poisson method.[36] Statistical significance was defined as a 2‐sided P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 3.1.0; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria;

RESULTS

During the QI project period, 3352 patients were admitted to the 2 general medicine units. Twelve (0.4%) patients expired on the units, but their data were retained in the analysis. Mean (standard deviation [SD]) age of the patients was 54.4 (18.3) years, with 47% male, and 54% African American. A total of 1896 of 6654 (28%) patients on the QI units were 65 years old. Patient characteristics were similar during the QI period versus 12 months prior (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Comparison Period, March 2012March 2013, N = 3,302 | QI Period, March 2013March 2014, N = 3,352 |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Age, y | 53.3 (17.8) | 54.4 (18.3) |

| Male | 1467 (44%) | 1569 (47%) |

| Race | ||

| African American | 1883 (57%) | 1809 (54%) |

| Caucasian | 1269 (38%) | 1348 (40%) |

| Other | 150 (5%) | 195 (6%) |

| Payer | ||

| Medicare | 1310 (40%) | 1470 (44%) |

| Medicaid | 1015 (31%) | 925 (28%) |

| Other | 977 (30%) | 957 (29%) |

| Admission diagnostic category | ||

| Infectious disease | 579 (18%) | 629 (19%) |

| Pulmonary | 519 (16%) | 559 (17%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 535 (16%) | 494 (15%) |

| Cardiovascular | 410 (12%) | 405 (12%) |

| Hematologic | 199 (6%) | 195 (6%) |

| Renal | 220 (7%) | 205 (6%) |

| Other | 840 (25%) | 865 (26%) |

| UHC expected length of stay, d | 5.5 (3.3) | 5.3 (3.2) |

| AHRQ comorbidity index | 3.3 (1.7) | 3.5 (1.8) |

During the 12‐month QI project, there were a total of 13,815 patient‐days of documented mobility data and the median (interquartile range [IQR]) number of days of documentation for each hospital admission was 3 (25) days. Compliance with daily documentation of JH‐HLM was 85.0% over the entire 12‐month QI project. Documentation compliance started at 83% during the ramp‐up phase and increased to 89% during the last 4 months of the project (late‐QI phase, P < 0.001).

Comparing the ramp‐up phase versus post‐QI phase, the percentage of patient‐days in which patients ambulated (JH‐HLM 6) increased from 43% to 70% (P < 0.001), and the percentage of patients who experienced an improvement in their mobility scores between admission and discharge increased from 32% to 45% (P < 0.001), as shown in Table 2. In the sensitivity analysis imputing missing daily JH‐HLM scores and comparing the ramp‐up versus post‐QI phases, the results were similar to the primary analysis; the percent of patient‐days where patients ambulated increased from 60% to 78% (P < 0.001), and the percent of patients who experienced an improvement in their mobility scores increased from 26% to 48% (P < 0.001).

| JH‐HLM Category | Ramp‐up Phase, March 1, 2013 June 30, 2013, n = 4,649 | Late‐QI Phase, November 1, 2013February 28, 2013, n = 4,515 | Post‐QI Phase, March 1, 2014 June 30, 2014, n = 4,298 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Change in Mobility (Admission Versus Discharge) | Ramp‐up Phase, March 1, 2013June 30, 2013, n = 968 | Late‐QI Phase, November 1, 2013February 28, 2013, n = 893 | Post‐QI Phase, March 1, 2014 June 30, 2014, n = 834 |

| |||

| Walk (JH‐HLM = 6, 7, or 8) | 1,994 (43) | 3,430 (76) | 2,986 (70) |

| Stand/chair (JH‐HLM = 4 or 5) | 1,772 (38) | 488 (10) | 511 (12) |

| Bed (JH‐HLM = 1, 2, or 3) | 883 (19) | 597 (13) | 801 (19) |

| Improved | 305 (32) | 392 (44) | 379 (45) |

| No change | 512 (53) | 428 (48) | 386 (46) |

| Declined | 151 (16) | 73 (8) | 69 (8) |

LOS during the 12‐month QI project versus the 12‐months immediately prior was shorter (Table 3), with an unadjusted median (IQR) LOS of 3 (26) versus 4 (27) days (P < 0.001) and an unadjusted mean (SD) LOS of 5.1 (5.6) versus 6.0 (7.6) (P < 0.001).

Adjusted Median LOS, d | Absolute Change in Adjusted Median LOS (95% CI), d | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 Months Prior | QI Project Months | |||

| ||||

| All patients | 6.01 | 5.61 | 0.40 (0.57 to 0.21), N = 4,411 | <0.001 |

| Subgroups by ELOS | ||||

| ELOS <4 days | 4.68 | 4.77 | 0.09 (0.13 to 0.32), N = 1,357 | 0.42 |

| ELOS 47 days | 5.68 | 5.38 | 0.30 (0.57 to 0.01), N = 1,509 | 0.04 |

| ELOS >7 days | 8.07 | 6.96 | 1.11 (1.53 to 0.65), N = 1,545 | <0.001 |

Table 3 displays the change in adjusted median LOS for the project months versus the 12 months prior among the QI units. We found that for all patients, there was an overall reduction in adjusted median LOS of 0.40 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.57 to 0.21, P<0.001) days. When we divided patients into tertiles based on their UHC expected LOS (ELOS), we observed that patients with longer ELOS had greater reductions in adjusted median LOS. Patients on the QI units with ELOS <4 days (lowest tertile) did not show a significant reduction in adjusted median LOS (0.09 days, 95% CI: 0.13 to 0.32, P = 0.42); however, patients with UHC ELOS 4 to 7 days (middle tertile) and ELOS >7 days (highest tertile) had a significant reduction in adjusted median LOS by 0.30 (95% CI: 0.57 to 0.01, P = 0.04) and 1.11 (95% CI: 1.53 to 0.65, P < 0.001) days during the QI project versus 12 months prior, respectively.

Lastly, we found that there was no difference in the rate of injurious falls on the QI units during QI period compared to 12 months prior (QI: 0.34 per 1000 patient‐days versus 12 months prior: 0.48 per 1000 patient‐days, P = 0.73).

DISCUSSION

We conducted a nurse‐driven, multidisciplinary mobility promotion QI project on 2 general medicine units at a large teaching hospital. The 12‐month QI project, conducted between March 1, 2013 and February 28, 2014, was associated with patients ambulating more frequently, with improved mobility status between hospital admission and discharge. These improvements in mobility were not associated with increased rates of injurious falls, and were sustained for at least 4 months after project completion. The QI project was associated with overall significant reduction in LOS for more complex patients with longer expected LOS (4 days or longer). Hence, such QI efforts may be important for maintaining or improving patients' functional status during hospitalization in a safe and cost‐effective manner.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies showing that mobility promotion in the acute hospital setting is feasible, can reduce length of stay, and can be applied to a diverse population including vulnerable medical patients with multiple comorbidities and the elderly.[12, 16, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42] These studies provide valuable evidence of the benefits of mobility promotion; however, it is difficult to translate these prior results into routine clinical practice because they used specially trained staff to mobilize patients, focused on a select patient population, or did not specify how the mobility intervention was delivered within daily clinical workflows. Research in the medical ICU at our institution has previously described the use of a structured QI model to successfully implement an early rehabilitation program.[22, 24] Here, we successfully adapted the same QI framework to a general medicine setting. Hence, our study contributes to the literature with respect to (1) use of a structured QI framework to develop a successful patient mobility program in a general medicine patient population, and (2) sharing best practices from 1 clinical setting, such as the ICU, as a source of learning and knowledge translation for other care settings, with the addition of novel tools, such as the JH‐HLM scale.

There may have been several factors that contributed to shorter stays in the hospital we observed during the QI project. First, we increased the number of ambulatory patient‐days, which may have helped prevent physiological complications of bed rest, such as muscle weakness, atelectasis, insulin resistance, vascular dysfunction, contractures, and pressure ulcers.[43] As such, mobility promotion has been associated with reduced rates of other hospital‐acquired complications, such as deep venous thrombosis, pneumonia, and delirium.[44, 45, 46] In our study, we saw the greatest LOS reduction in more complex patients who were expected to spend a longer time in the hospital and are at greater risk of developing complications from bed rest. Second, our early mobility project may have had a direct impact on care‐coordination processes as reported in prior studies.[47, 48, 49] An important component of our intervention was incorporating functional status into multidisciplinary discussions, either through nurse‐to‐therapist huddles or care‐coordination rounds between nurses, therapists, physicians, social workers, and case managers. During care‐coordination rounds, JH‐HLM scores were reported to expedite appropriate physical and occupational therapy consultations and assist in determining appropriate discharge location. During the QI project, we transitioned from a unit‐based daily huddle between nursing and rehabilitation therapists to a system where mobility status was discussed primarily during care coordination rounds 5 times per week. We saw that mobility scores were maintained after QI project completion, suggesting that reporting on patient function in a multidisciplinary setting is a potentially sustainable mechanism to improve care‐coordination processes that are affected by functional status.

Our study has several potential limitations. First, this is a single‐site study in 2 general medicine units of a large academic hospital. Further research is needed to determine if this structured QI intervention and its benefits can be generalized to different settings and different patient populations. Second, because the documentation was initially an optional element in the electronic medical record system, we observed higher rates of missing documentation during the first 4 months of the project versus the comparison period at 4 months after project completion. However, a sensitivity analysis conducted of these missing data demonstrated similar results to our primary analysis. Third, our nonrandomized pre‐post study design does not allow us to conclude a direct cause‐and‐effect relationship between our intervention and increased mobility and reduced LOS. Although patient characteristics were similar between the 2 periods and adjusted for in our multivariable regression analysis, we cannot rule out the possibility of secular trends in LOS on the project units and that broader QI efforts at our institution also contributed to reduction in LOS. Fourth, we do not have data on 30‐day readmissions and discharge location. Future studies should explore the impact of hospital‐based mobility interventions on these outcomes.[50] Fifth, although nurses consistently documented the highest level of mobility on a daily basis, these data did not capture other potentially important information about patient mobility such as the daily frequency that patients were mobilized, the length of time a patient was engaged in a mobility event (ie, number of hours sitting in a chair), or the mobility that occurred during physical therapy or occupational therapy sessions. Hence, although we used JH‐HLM as a marker of improved mobility during our QI project it is likely that our data cannot fully describe the total mobility and activity that patients experienced during hospitalization. Lastly, although the front‐line staff and QI team found the JH‐HLM scale to be a useful tool to measure and advance patient mobility, further studies are needed to evaluate the reliability and validity of this scale.

CONCLUSION

A structured QI process can improve patient mobility and may contribute to reduction in LOS, particularly for more complex patients in this setting. Active prevention of decline in physical function that commonly occurs during hospitalization may prove valuable for improving patient outcomes and reducing healthcare resource utilization.

Disclosures

The authors certify that no party having a direct interest in the results of the research supporting this article has or will confer a benefit on us or on any organization with which we are associated. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):451–458.

- , , . Prevalence and outcomes of low mobility in hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(8):1263–1270.

- , , , , , . Trajectories of life‐space mobility after hospitalization. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(6):372–378.

- , , . Hospitalization‐associated disability: “She was probably able to ambulate, but I'm not sure”. JAMA. 2011;306(16):1782–1793.

- , , , , , . Physical fitness and all‐cause mortality. A prospective study of healthy men and women. JAMA. 1989;262(17):2395–2401.

- . Mobilizing patients in the intensive care unit: improving neuromuscular weakness and physical function. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1685–1690.

- , . Mobility limitation in the older patient: a clinical review. JAMA. 2013;310(11):1168–1177.

- , , , et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9678):1874–1882.

- , , . Technology to enhance physical rehabilitation of critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(10 suppl):S436–S441.

- , , , et al. Receiving early mobility during an intensive care unit admission is a predictor of improved outcomes in acute respiratory failure. Am J Med Sci. 2011;341(5):373–377.

- . Physiotherapy in intensive care: an updated systematic review. Chest. 2013;144(3):825–847.

- , , . Exercise for acutely hospitalised older medical patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD005955.

- , , . Extra physical therapy reduces patient length of stay and improves functional outcomes and quality of life in people with acute or subacute conditions: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(9):1490–1500.

- , . Impact of early mobilization protocol on the medical‐surgical inpatient population: an integrated review of literature. Clin Nurse Spec. 2012;26(2):87–94.

- , , . Outcomes of inpatient mobilization: a literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(11–12):1486–1501.

- , , , et al. The early mobility bundle: a simple enhancement of therapy which may reduce incidence of hospital‐acquired pneumonia and length of hospital stay. J Hosp Infect. 2014;88(1):34–39.

- , , , , . Physical therapy on the wards after early physical activity and mobility in the intensive care unit. Phys Ther. 2012;92(12):1518–1523.

- , , , . Impact of hospital variables on case mix index as a marker of disease severity. Popul Health Manag. 2014;17(1):28–34.

- , , , , . Frequency of hallway ambulation by hospitalized older adults on medical units of an academic hospital. Geriatr Nurs. 2004;25(4):212–217.

- , , . Activity level of hospital medical inpatients: an observational study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;55(2):417–421.

- , , . Translating evidence into practice: a model for large scale knowledge translation. BMJ. 2008;337:a1714.

- , , , et al. Early physical medicine and rehabilitation for patients with acute respiratory failure: a quality improvement project. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(4):536–542.

- , , , , ; SQUIRE development group. Publication guidelines for quality improvement studies in health care: evolution of the SQUIRE project. BMJ. 2009;338:a3152.

- , . Rehabilitation quality improvement in an intensive care unit setting: implementation of a quality improvement model. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2010;17(4):271–281.

- , , , . ICU early mobilization: from recommendation to implementation at three medical centers. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(9 suppl 1):S69–S80.

- , , , . Barriers to early mobility of hospitalized general medicine patients: survey development and results. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;94(4):304–312.

- , , , . Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27.

- UHC Clinical Information Management Risk Adjustment of the UHC Clinical Data Base. Chicago, IL: University HealthSystem Consortium; 1998.

- Sachs Complications Profiler, Version 1.0, User's Guide. Evanston, IL: Sachs Group; 1995.

- , , . Assessing hospital‐associated deaths from discharge data. The role of length of stay and comorbidities. JAMA. 1988;260(15):2240–2246.

- , , , et al. Annual rates of admission and seasonal variations in hospitalizations for heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2002;4(6):779–786.

- , , , . Regional and seasonal variation in the length of hospital stay for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Finland. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2002;61(2):131–135.

- , , , , , ; Canadian CABG Surgery Quality Indicator Consensus Panel. The identification and development of canadian coronary artery bypass graft surgery quality indicators. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130(5):1257.

- , , , . Quality of care and length of hospital stay among patients with stroke. Med Care. 2009;47(5):575–582.

- . A systematic review of outcomes and quality measures in adult patients cared for by hospitalists vs nonhospitalists. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(3):248–254.

- . Confidence intervals that match Fisher's exact or Blaker's exact tests. Biostatistics. 2010;11(2):373–374.

- , , , et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(9):669–676.

- , , , , . Early mobilization of patients hospitalized with community‐acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2003;124(3):883–889.

- , , , et al. Effects of a walking intervention on fatigue‐related experiences of hospitalized acute myelogenous leukemia patients undergoing chemotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35(5):524–534.

- , , , , . Early ambulation and length of stay in older adults hospitalized for acute illness. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(21):1942–1943.

- , , . Impact of a nurse‐driven mobility protocol on functional decline in hospitalized older adults. J Nurs Care Qual. 2009;24(4):325–331.

- , , . Exercising body and mind: an integrated approach to functional independence in hospitalized older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(4):630–635.

- . Consequences of bed rest. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(10 suppl):S422–S428.

- , , , , . Time to ambulation after hip fracture surgery: relation to hospitalization outcomes. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(11):M1042–M1045.

- , , , . Early mobilization after total knee replacement reduces the incidence of deep venous thrombosis. ANZ J Surg. 2009;79(7–8):526–529.

- , , , . Efficacy and safety of postoperative early mobilization for chronic subdural hematoma in elderly patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2010;152(7):1171–1174.

- , , , et al. Impact of relational coordination on quality of care, postoperative pain and functioning, and length of stay: a nine‐hospital study of surgical patients. Med Care. 2000;38(8):807–819.

- Care coordination cuts admissions, ED visits, LOS. Hosp Case Manag. 2013;21(5):67–68.

- , . A heart failure initiative to reduce the length of stay and readmission rates. Prof Case Manag. 2014;19(6):276–284.

- , , , , , . Association of impaired functional status at hospital discharge and subsequent rehospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(5):277–282.

Annually, more than 35 million patients are hospitalized in the United States, with many experiencing hospital‐acquired impairments in physical functioning during their in‐patient stay.[1, 2, 3, 4] Such impairments include difficulties performing basic activities of daily living, such as rising from a chair, toileting, or ambulating. This functional decline may result in increased length of stay (LOS), nursing home placement, and decreased mobility and participation in community activities even years after hospitalization.[1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7] Ameliorating this hospital‐acquired functional impairment is important to improving patient outcomes and reducing healthcare utilization. Even the sickest hospitalized patients (eg, those in the intensive care unit [ICU]), can safely and feasibly benefit from early mobilization.[6, 8, 9, 10, 11] In the non‐ICU setting there is also evidence that patient mobilization reduces LOS and hospital costs, while improving patient satisfaction and physical and psychological outcomes.[12, 13, 14, 15, 16] These studies are, however, difficult to replicate as part of routine clinical care, because they often do not present the details of how early mobility was incorporated into daily practice, require additional hospital resources (eg, specially trained providers or additional staff), or are focused only on a select patient population.

The Johns Hopkins medical ICU started early rehabilitation quality‐improvement (QI) work in 2007, which has demonstrated ongoing reductions in LOS and been transformative in terms of helping to foster a culture of mobility at our institution. Previous research suggests that ICU‐based rehabilitation interventions are often not carried over to the ward setting, even in post‐ICU patients.[17] Moreover, trends for sicker patients being admitted in our general medicine units,[18] growing reports of patients spending most of their time in bed,[2, 19, 20] and healthcare policies emphasizing the importance of improving inpatient outcomes motivated the need for QI to improve patient mobility in this setting. Experience from the medical ICU‐based early rehabilitation program helped drive multidisciplinary collaboration of stakeholders to develop this nurse‐driven, mobility promotion QI project on 2 general medicine hospital units. The main goals of the project were to see whether a QI framework can be used in a general medicine setting to increase patient mobility and reduce LOS.[21, 22]

METHODS

Overview of Project

Mobility, for this project, was defined as a patient getting out of bed (eg, sitting out of bed, toileting at bedside commode or bathroom, standing, and ambulating). We aimed to increase patient mobility using preexisting unit staffing ratios of clinicians and support staff. This project was reported in accordance with the SQUIRE (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence) guidelines and used a structured QI model that had been used to successfully promote early mobility in the intensive care unit.[21, 23, 24, 25] The planning phase of the QI project began in spring 2012, with initiation of the 12‐month project on March 1, 2013. During the 12‐month QI period, prospective collection of mobility status occurred for all patients, with no exclusions based on patient characteristics.

Setting

The QI project setting was 2, 24‐bed, general medicine units at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, a large academic medical center located in Baltimore, Maryland.

QI Process

The primary goals of the QI project were to mobilize patients 3 times daily, quantify and document the mobility of the patients, set daily goals to increase mobility (eg, move up 1 step on the scale today), and standardize the description of patient mobility across all hospital staff. We used a structured QI model that that has been used to implement an early mobility program in a medical ICU at our institution[21, 22, 24] (see Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article). At a programmatic level, we involved key stakeholders (nurses, physicians, rehabilitation therapists, administrators) in the QI project team, we identified local barriers to implementation through team meetings as well as a survey tool to identify perceived barriers,[26] and we developed a scale (the Johns Hopkins Highest Level of Mobility [JH‐HLM]) to document mobility. The JH‐HLM is an 8‐point ordinal scale that captures mobility milestones, where 1 = only lying, 2 = bed activities, 3 = sit at edge of bed, 4 = transfer to chair/commode, 5 = standing for 1 minute, 6 = walking 10+ steps, 7 = walking 25+ feet, and 8 = walking 250+ feet (see Supporting Information, Appendix and Supporting Figure 1, in the online version of this article for additional information on the JH‐HLM scale).

The 12‐month QI project was characterized by several phases and milestones and involved a number of intervention components. During the first 4 months (ramp‐up phase), nurses received education in the form of unit‐based presentations, hands‐on‐training, and online education modules. On a 5‐times weekly basis, nurses met with rehabilitation therapists for unit‐based huddles to discuss baseline patient mobility, current patient mobility levels, barriers to mobilizing patients, and daily goals to progress mobility. Mobility levels were included on daily nursing report sheets to facilitate communication with subsequent shifts. Discussion of JH‐HLM scores also occurred during daily unit‐based care‐coordination meetings of the nurses, physicians, and social‐workers to address barriers to mobilizing patients, such as optimizing pain control, facilitating discharge location planning, and expediting physician consultation with physical and occupational therapy for appropriate patients. Audit and feedback from huddles and care‐coordination rounds resulted in improved nurse attendance and engagement during these meetings. Nurses were expected to document patient mobility scores using the JH‐HLM 3 times daily in the patient medical record. On the fourth month, reports on JH‐HLM scores and documentation compliance were available to nurse managers, champions, and unit staff. Via twice‐monthly meetings with the units and quarterly meetings with hospital leadership and administration, problems arising during the QI intervention were evaluated and resolved on a timely basis. Seven months after project execution started, educational sessions were repeated to all staff, and feedback was provided based on the data collected, such as documentation compliance rates and patient mobility levels, and nurse champions presented the project during an American Nurses Credentialing Center magnet recognition program visit. Lastly, mobility scores and documentation compliance were continually assessed for 4 months after the project completion to determine sustainability of the intervention. Additional details of the QI project implementation are provided in the Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article.

Data Sources and Covariates for Project Evaluation

The Sunrise Clinical Manager system (Allscripts Healthcare Solutions Inc., Chicago, IL) was used to document and extract nursing‐documented JH‐HLM scores. The Johns Hopkins Hospital Datamart financial database, used for mandatory reporting to the State of Maryland, provided data on LOS, age, sex, race (white, black, other), payer (Medicare, Medicaid, other), primary admission diagnosis, and comorbidity index using Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) methodology.[27] Expected LOS was calculated using the risk adjustment method developed by the University Health System Consortium (UHC).[28] This calculation uses a combination of the Diagnostic‐Related Group grouper and the Sachs Complication Profiler[29] in conjunction with data on specific patient characteristics (age, sex, urgency of admission, payer category) to construct risk‐adjustment regression models that assign expected values for LOS, and is not based on actual LOS.[28] The databases were linked at the patient level using the patient's medical record and unique admission record number.

Outcome Measures

Two functional outcome measures were based on daily JH‐HLM scores, which frequently occurred several times on each patient‐day: (1) the maximum daily JH‐HLM scores for each patient‐day during hospitalization, and (2) the intrapatient change in JH‐HLM scores between the maximum JH‐HLM score within 24 hours of hospital admission and 24 hours before discharge for all patients who were on the unit >48 hours. We also compared the mean LOS during the 12‐month QI project versus the 12‐months prior so we could more accurately address seasonal differences.[30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35] Lastly, because the perception of increased falls was an important barrier to address in the QI process, we compared the rate of injurious falls between the QI period and 12‐months prior.

Statistical Analysis

To evaluate changes in the percent of ambulatory patients (JH‐HLM 6), we compared the initial 4 months of the QI project (ramp‐up phase) with the same 4‐month period occurring immediately after project completion (post‐QI phase) using generalized estimating equations to account for clustering at the patient‐level. This test was also used to evaluate changes in documentation compliance rates between the 2 phases, with compliance defined as at least 1 instance of JH‐HLM documentation per day, excluding the day of admission and discharge. To evaluate if improved JH‐HLM results were driven by improved documentation compliance rates over time, we performed a sensitivity analysis by imputing a JH‐HLM score of 6 (ambulate 10+ steps) for any missing daily maximum JH‐HLM scores.

To assess unadjusted changes in LOS during the 12‐month QI project versus the same period 1 year earlier, we compared mean and median LOS using a t test and Wilcoxon rank sum test, respectively. We used a multivariable linear regression model to estimate the change (expressed in days) in adjusted median LOS comparing the project months (March 2013March 2014) with 12 months prior (March 2012March 2013). The model adjusted for age, gender, race, payer, admission diagnostic category, UHC expected LOS, and AHRQ comorbidity index. We confirmed a lack of multicollinearity in the multivariable regression model using variance inflation factors. We evaluated residual versus predicted value plots and residual versus fitted value plots with a locally weighted scatterplot smoothing line to confirm model fit. P values are reported from the test of the null hypothesis that the change in adjusted median LOS is the same comparing the QI project months versus 12 months prior. Separate models estimated and tested the change in adjusted median LOS by tertiles of expected LOS (<4, 47, and >7 days). Lastly, we compared the rate of injurious falls (the number of injurious falls by total patient‐days) between the QI period and 12 months prior using an exact Poisson method.[36] Statistical significance was defined as a 2‐sided P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 3.1.0; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria;

RESULTS

During the QI project period, 3352 patients were admitted to the 2 general medicine units. Twelve (0.4%) patients expired on the units, but their data were retained in the analysis. Mean (standard deviation [SD]) age of the patients was 54.4 (18.3) years, with 47% male, and 54% African American. A total of 1896 of 6654 (28%) patients on the QI units were 65 years old. Patient characteristics were similar during the QI period versus 12 months prior (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Comparison Period, March 2012March 2013, N = 3,302 | QI Period, March 2013March 2014, N = 3,352 |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Age, y | 53.3 (17.8) | 54.4 (18.3) |

| Male | 1467 (44%) | 1569 (47%) |

| Race | ||

| African American | 1883 (57%) | 1809 (54%) |

| Caucasian | 1269 (38%) | 1348 (40%) |

| Other | 150 (5%) | 195 (6%) |

| Payer | ||

| Medicare | 1310 (40%) | 1470 (44%) |

| Medicaid | 1015 (31%) | 925 (28%) |

| Other | 977 (30%) | 957 (29%) |

| Admission diagnostic category | ||

| Infectious disease | 579 (18%) | 629 (19%) |

| Pulmonary | 519 (16%) | 559 (17%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 535 (16%) | 494 (15%) |

| Cardiovascular | 410 (12%) | 405 (12%) |

| Hematologic | 199 (6%) | 195 (6%) |

| Renal | 220 (7%) | 205 (6%) |

| Other | 840 (25%) | 865 (26%) |

| UHC expected length of stay, d | 5.5 (3.3) | 5.3 (3.2) |

| AHRQ comorbidity index | 3.3 (1.7) | 3.5 (1.8) |

During the 12‐month QI project, there were a total of 13,815 patient‐days of documented mobility data and the median (interquartile range [IQR]) number of days of documentation for each hospital admission was 3 (25) days. Compliance with daily documentation of JH‐HLM was 85.0% over the entire 12‐month QI project. Documentation compliance started at 83% during the ramp‐up phase and increased to 89% during the last 4 months of the project (late‐QI phase, P < 0.001).

Comparing the ramp‐up phase versus post‐QI phase, the percentage of patient‐days in which patients ambulated (JH‐HLM 6) increased from 43% to 70% (P < 0.001), and the percentage of patients who experienced an improvement in their mobility scores between admission and discharge increased from 32% to 45% (P < 0.001), as shown in Table 2. In the sensitivity analysis imputing missing daily JH‐HLM scores and comparing the ramp‐up versus post‐QI phases, the results were similar to the primary analysis; the percent of patient‐days where patients ambulated increased from 60% to 78% (P < 0.001), and the percent of patients who experienced an improvement in their mobility scores increased from 26% to 48% (P < 0.001).