User login

Patient-Specific Implants in Severe Glenoid Bone Loss

ABSTRACT

Complex glenoid bone deformities present the treating surgeon with a complex reconstructive challenge. Although glenoid bone loss can be encountered in the primary setting (degenerative, congenital, post-traumatic), severe glenoid bone loss is encountered in most revision total shoulder arthroplasties. Severe glenoid bone loss is treated with various techniques including hemiarthroplasty, eccentric reaming, and glenoid reconstruction with bone autografts and allografts. Despite encouraging short- to mid-term results reported with these reconstruction techniques, the clinical and radiographic outcomes remain inconsistent and the high number of complications is a concern. To overcome this problem, more recently augmented components and patient specific implants were introduced. Using the computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing technology patient-specific implants have been created to reconstruct the glenoid vault in cases of severe glenoid bone loss.

In this article we describe a patient specific glenoid implant, its indication, technical aspects and surgical technique, based on the author's experience as well as a review of the current literature on custom glenoid implants.

Continue to: Total shoulder arthroplasty...

Total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) is an effective operation for providing pain relief and improving function in patients with end-stage degenerative shoulder disease that is nonresponsive to nonoperative treatments.1-4 With the increasing number of arthroplasties performed, and the expanding indication for shoulder arthroplasty, the number of revision shoulder arthroplasties is also increasing.5-14 Complex glenoid bone deformities present the treating surgeon with a complex reconstructive challenge. Although glenoid bone loss can be seen in the primary setting (degenerative, congenital, and post-traumatic), severe glenoid bone loss is encountered mostly in revision TSAs.

Historically, patients with severe glenoid bone loss were treated with a hemiarthroplasty.15-17 However, due to inferior outcomes associated with the use of shoulder hemiarthroplasties compared with TSA in these cases,18-20 various techniques were developed with the aim of realigning the glenoid axis and securing the implants into the deficient glenoid vault.21-25 Options have included eccentric reaming, glenoid reconstruction with bone autografts and allografts, and more recently augmented components and patient-specific implants. Studies with eccentric reaming and reconstruction with bone graft during complex shoulder arthroplasty have reported encouraging short- to mid-term results, but the clinical and radiographic outcomes remain inconsistent, and the high number of complications is a concern.25-28

Complications with these techniques include component loosening, graft resorption, nonunion, failure of graft incorporation, infection, and instability.25-28

Computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing (CAD/CAM) of patient-specific implants have been used successfully by hip arthroplasty surgeons to deal with complex acetabular reconstructions in the setting of severe bone loss. More recently, the same technology has been used to reconstruct the glenoid vault in cases of severe glenoid bone loss.

In this article, we describe a patient-specific glenoid implant, its indication, and both technical aspects and the surgical technique, based on the authors’ experience as well as a review of the current literature on custom glenoid implants.

Continue to: PATIENT-SPECIFIC GLENOID COMPONENT

PATIENT-SPECIFIC GLENOID COMPONENT

The Vault Reconstruction System ([VRS], Zimmer Biomet) is a patient-specific glenoid vault reconstruction system developed with the use of CAD/CAM to address severe glenoid bone loss encountered during shoulder arthroplasty. For several years, the VRS was available only as a custom implant according to the US Food and Drug Administration rules, and therefore its use was limited to a few cases per year. Recently, a 510(k) envelope clearance was granted to use the VRS in reverse TSA to address significant glenoid bone defects.

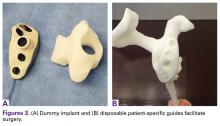

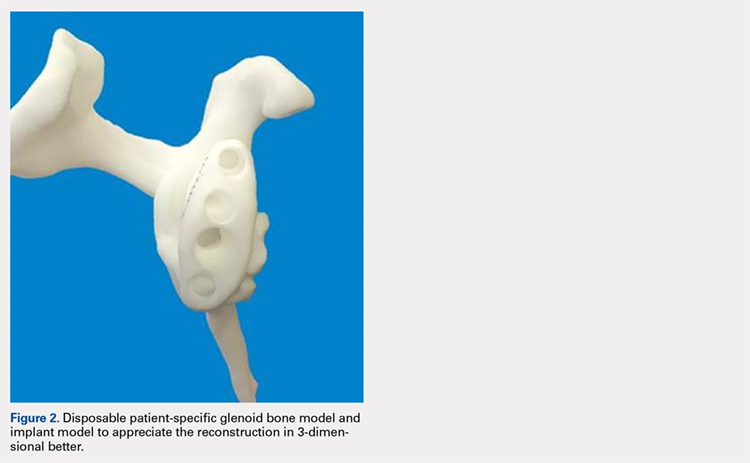

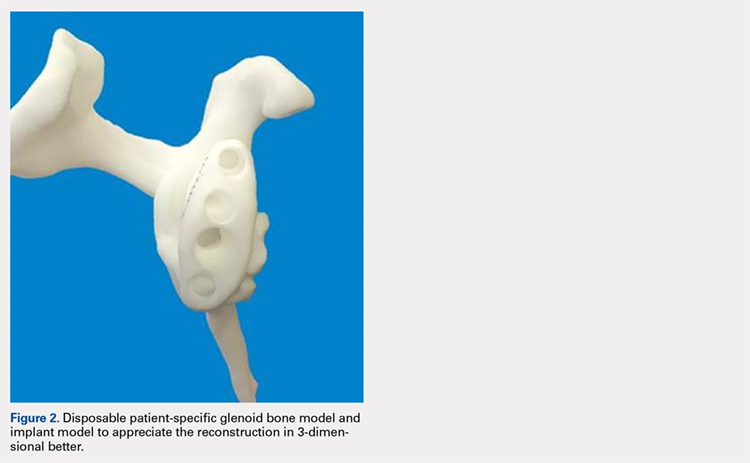

The VRS is made of porous plasma spray titanium to provide high strength and flexibility, and allows for biologic fixation. This system can accommodate a restricted bone loss envelope of about 50 mm × 50 mm × 35 mm according to the previous experience of the manufacturer in the custom scenario, covering 96% of defects previously addressed. One 6.5-mm nonlocking central screw and a minimum of four 4.75-mm nonlocking or locking peripheral screws are required for optimal fixation of the implant in the native scapula. A custom boss can be added in to enhance fixation in the native scapula when the bone is sufficient. To facilitate the surgical procedure, a trial implant, a bone model of the scapula, and a custom boss reaming guide are 3-dimensional (3-D) and printed in sterilizable material. These are all provided as single-use disposable instruments and can be available for surgeons during both the initial plan review and surgery.

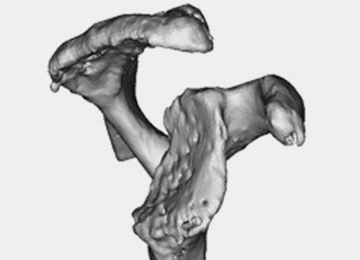

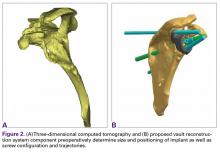

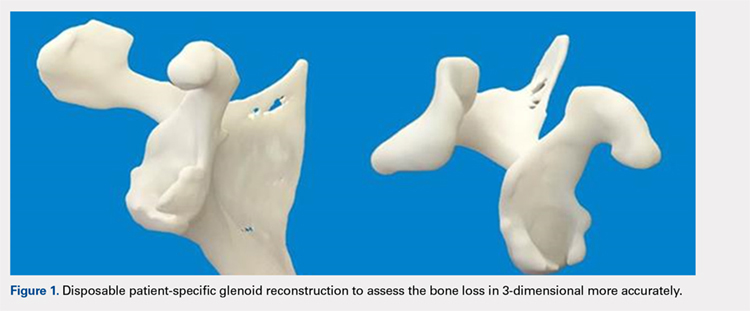

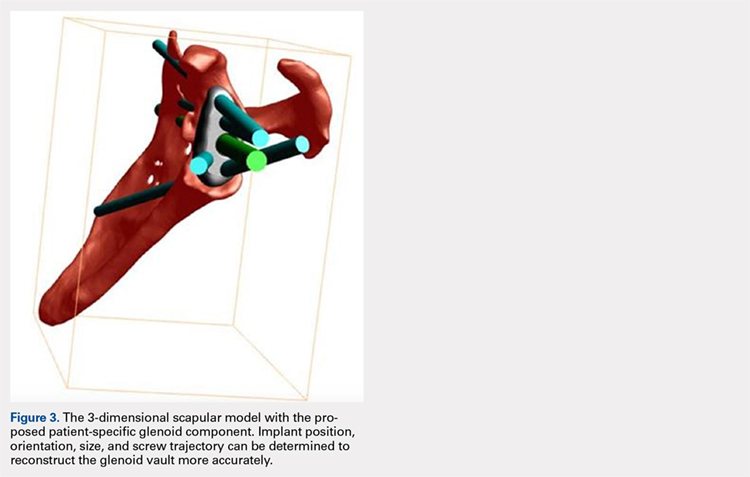

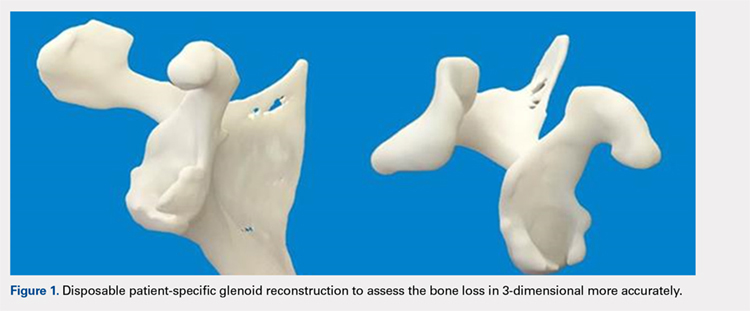

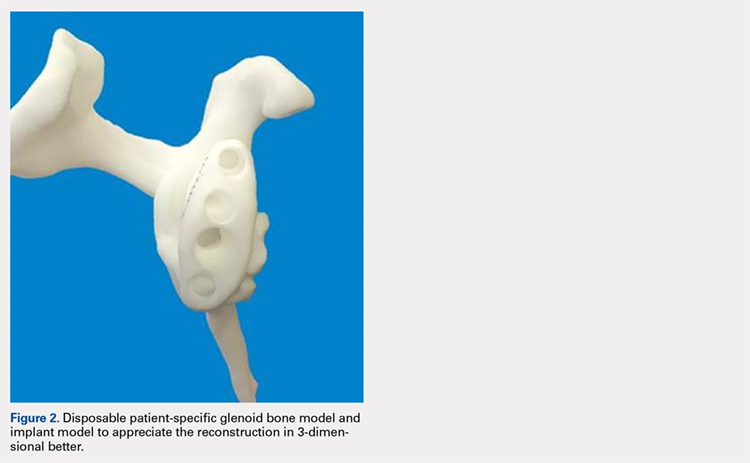

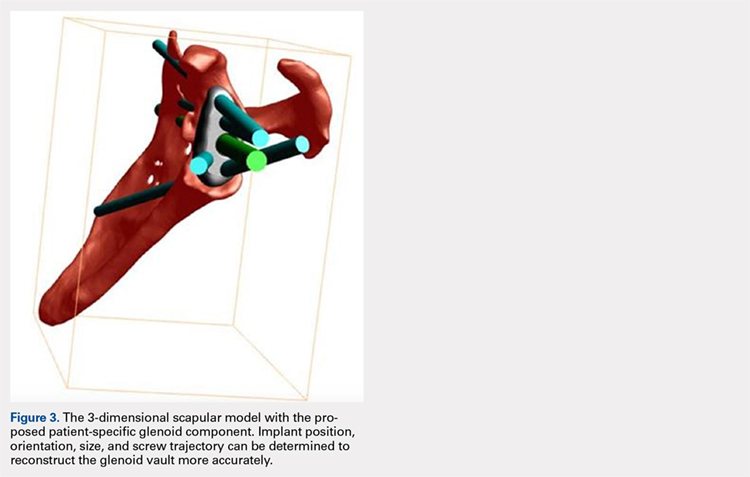

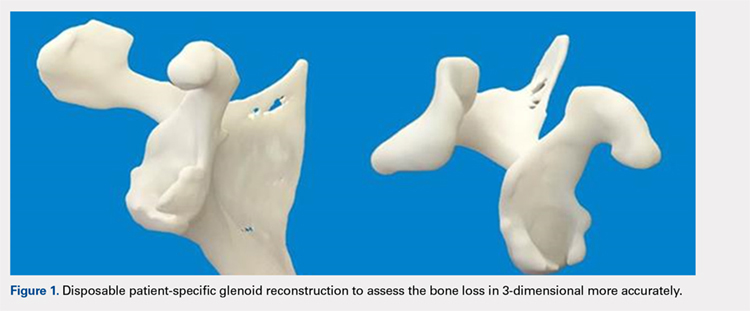

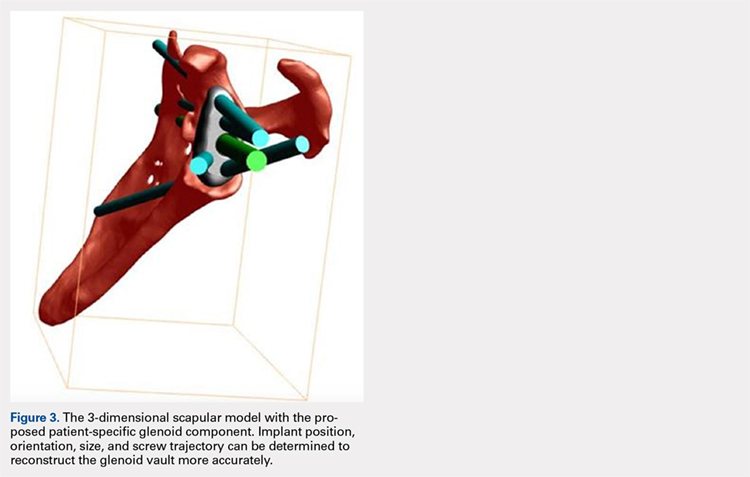

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Patients undergo a preoperative fine-cut 2-dimensional computed tomography scan of the scapula and adjacent humerus following a predefined protocol with a slice thickness of 2 mm to 3 mm. An accurate 3-D bone model of the scapula is obtained using a 3-D image processing software system (Figure 1). The 3-D scapular model is used to create a patient-specific glenoid implant proposal that is approved by the surgeon (Figure 2). Implant position, orientation, size, screw trajectory, and recommended bone removal, if necessary, are determined to create a more normal glenohumeral center of rotation and to secure a glenoid implant in severely deficient glenoid bone (Figure 3). Once the implant design is approved by the surgeon, the final patient-specific implant is manufactured.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

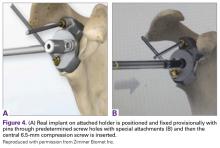

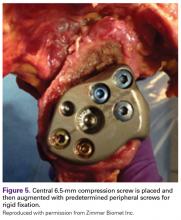

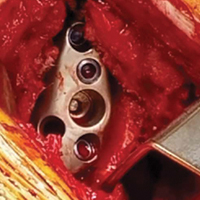

The exposure of the glenoid is a critical step for the successful implantation of the patient-specific glenoid implant. Soft tissue and scar tissue around the glenoid must be removed to allow for optimal fit of the custom-made reaming guide. Also, removal of the entire capsulolabral complex on the anteroinferior rim of the glenoid is essential to both enhance glenoid exposure and to allow a perfect fit of the guide to the pathologic bone stock. Attention should be paid during débridement and/or implant removal in case of revision, to make sure that no excessive bone is removed because the patient-specific guide is referenced to this anatomy. Excessive bone removal can change the orientation of the patient-specific guide and ultimately the fixation of the implant. Once the custom-made patient-specific guide is positioned, a 3.2-mm Steinmann pin is placed through the inserter for temporary fixation. The pin should engage or perforate the medial cortical wall to ensure that the subsequent reamer has a stable cannula over which to ream. After the glenoid is reamed, the final implant can be placed in the ideal position according to the preoperative planning. A central 6.5-mm nonlocking central screw and 4.75-mm nonlocking or locking peripheral screws are required to complete the fixation of the implant in the native scapula. Once the patient-specific glenoid component is positioned and strongly fixed to the bone, the glenosphere can be positioned according to the preoperative planning, and the reverse shoulder arthroplasty can be completed in the usual fashion.

CASE EXAMPLES

A 68-year-old woman underwent a TSA for end-stage osteoarthritis in 2000. The implant failed due to a cuff failure. The patient underwent several surgeries, including an open cuff repair, with no success. She had no active elevation preoperatively. Because of the significant glenoid bone loss, a patient-specific glenoid reconstruction was planned. Within 24 months after this surgery, the patient was able to get her hand to her head and elevate to 90º (Figures 4A-4F).

Continue to: In October 2013...

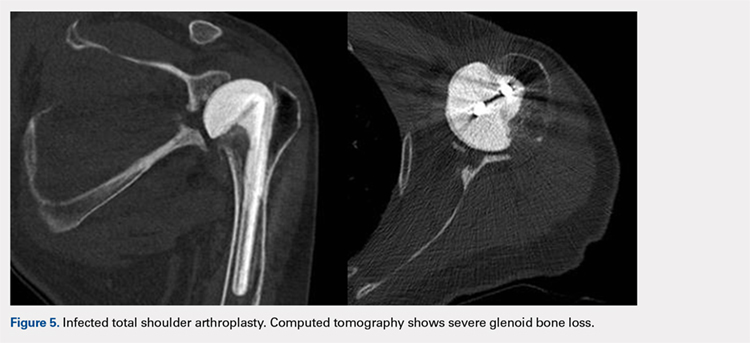

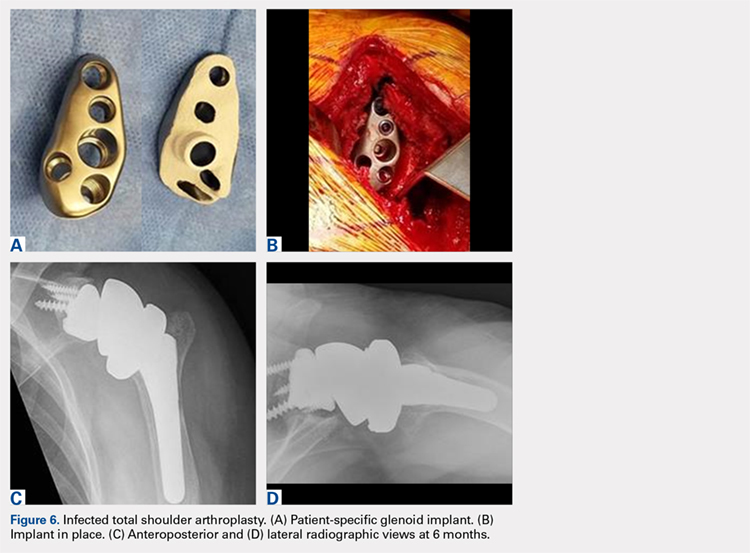

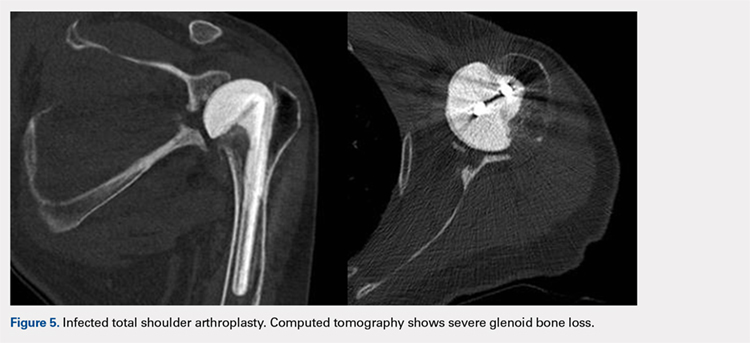

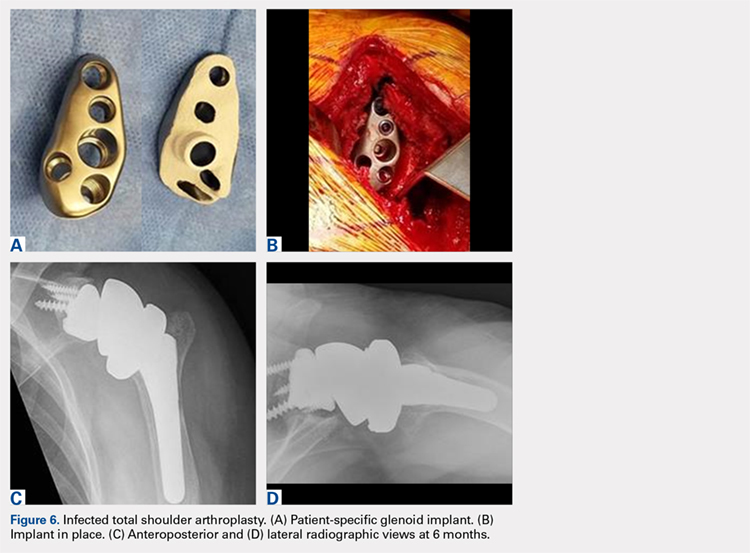

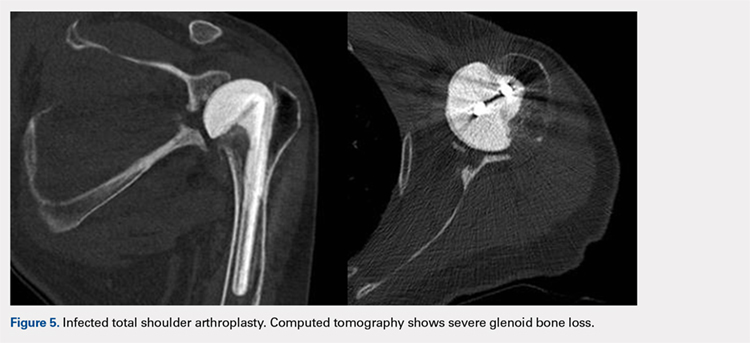

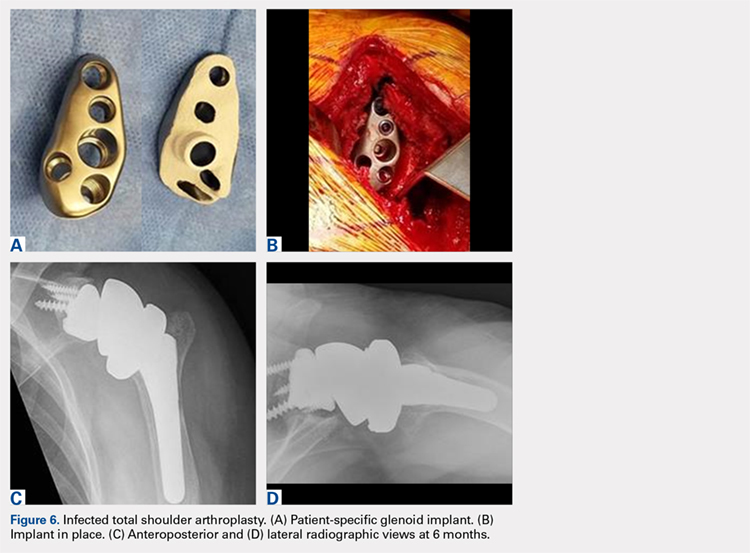

In October 2013, a 68-year-old man underwent a TSA for end-stage osteoarthritis. After 18 months, the implant failed due to active Propionibacterium acnes infection, which required excisional arthroplasty with insertion of an antibiotic spacer. Significant glenoid bone loss (Figure 5) and global soft-tissue deficiency caused substantial disability and led to an indication for a reverse TSA with a patient-specific glenoid vault reconstruction (Figures 6A-6D) after infection eradication. Within 20 months after this surgery, the patient had resumed a satisfactory range of motion (130º forward elevation, 20º external rotation) and outcome.

DISCUSSION

Although glenoid bone loss is often seen in the primary setting (degenerative, congenital, and post-traumatic), severe glenoid bone loss is encountered in most revision TSAs. The best treatment method for massive glenoid bone defects during complex shoulder arthroplasty remains uncertain. Options have included eccentric reaming, glenoid reconstruction with bone allograft and autograft, and more recently augmented components and patient-specific implants.21-25 The advent and availability of CAD/CAM technology have enabled shoulder surgeons to create patient-specific metal solutions to these challenging cases. Currently, only a few reports exist in the literature on patient-specific glenoid components in the setting of severe bone loss.29-32

Chammaa and colleagues29 reported the outcomes of 37 patients with a hip-inspired glenoid component (Total Shoulder Replacement, Stanmore Implants Worldwide). The 5-year results with this implant were promising, with a 16% revision rate and only 1 case of glenoid loosening.

Stoffelen and colleagues30 recently described the successful use of a patient-specific anatomic metal-backed glenoid component for the management of severe glenoid bone loss with excellent results at 2.5 years of follow-up. A different approach was pursued by Gunther and Lynch,31 who reported on 7 patients with a custom inset glenoid implant for deficient glenoid vaults. These circular anatomic, custom-made glenoid components were created with the intention of placing the implants partially inside the glenoid vault and relying partially on sclerotic cortical bone. Despite excellent results at 3 years of follow-up, their use is limited to specific defect geometries and cannot be used in cases of extreme bone loss.

CONCLUSION

We have described the use of a patient-specific glenoid component in 2 patients with severe glenoid bone loss. Despite the satisfactory clinical and short-term radiographic results, we acknowledge that longer-term follow-up is needed to confirm the efficacy of this type of reconstruction. We believe that patient-specific glenoid components represent a valuable addition to the armamentarium of shoulder surgeons who address complex glenoid bone deformities.

1. Chalmers PN, Gupta AK, Rahman Z, Bruce B, Romeo AA, Nicholson GP. Predictors of early complications of total shoulder arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(4):856-860. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2013.07.002.

2. Deshmukh AV, Koris M, Zurakowski D, Thornhill TS. Total shoulder arthroplasty: long-term survivorship, functional outcome, and quality of life. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(5):471-479. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2005.02.009.

3. Montoya F, Magosch P, Scheiderer B, Lichtenberg S, Melean P, Habermeyer P. Midterm results of a total shoulder prosthesis fixed with a cementless glenoid component. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(5):628-635. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2012.07.005.

4. Torchia ME, Cofield RH, Settergren CR. Total shoulder arthroplasty with the Neer prosthesis: long-term results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6(6):495-505.

5. Antuna SA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Rowland CM. Glenoid revision surgery after total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(3):217-224. doi:10.1067/mse.2001.113961.

6. Chalmers PN, Rahman Z, Romeo AA, Nicholson GP. Early dislocation after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(5):737-744. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.08.015.

7. Farng E, Zingmond D, Krenek L, Soohoo NF. Factors predicting complication rates after primary shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):557-563. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2010.11.005.

8. Farshad M, Grogli M, Catanzaro S, Gerber C. Revision of reversed total shoulder arthroplasty. Indications and outcome. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13(1):160. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-13-160.

9. Fevang BT, Lie SA, Havelin LI, Skredderstuen A, Furnes O. Risk factors for revision after shoulder arthroplasty: 1,825 shoulder arthroplasties from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop. 2009;80(1):83-91.

10. Fox TJ, Cil A, Sperling JW, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Schleck CD, Cofield RH. Survival of the glenoid component in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(6):859-863. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2008.11.020.

11. Rasmussen JV. Outcome and risk of revision following shoulder replacement in patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis. Acta Orthop Suppl. 2014;85(355 suppl):1-23. doi:10.3109/17453674.2014.922007.

12. Rasmussen JV, Polk A, Brorson S, Sorensen AK, Olsen BS. Patient-reported outcome and risk of revision after shoulder replacement for osteoarthritis. 1,209 cases from the Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry, 2006-2010. Acta Orthop. 2014;85(2):117-122. doi:10.3109/17453674.2014.893497.

13. Sajadi KR, Kwon YW, Zuckerman JD. Revision shoulder arthroplasty: an analysis of indications and outcomes. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(2):308-313. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2009.05.016.

14. Singh JA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Revision surgery following total shoulder arthroplasty: analysis of 2588 shoulders over three decades (1976 to 2008). J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(11):1513-1517. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.93B11.26938.

15. Levine WN, Djurasovic M, Glasson JM, Pollock RG, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU. Hemiarthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis: results correlated to degree of glenoid wear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6(5):449-454.

16. Levine WN, Fischer CR, Nguyen D, Flatow EL, Ahmad CS, Bigliani LU. Long-term follow-up of shoulder hemiarthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(22):e164. doi:10.2106/JBJS.K.00603.

17. Lynch JR, Franta AK, Montgomery WH, Lenters TR, Mounce D, Matsen FA. Self-assessed outcome at two to four years after shoulder hemiarthroplasty with concentric glenoid reaming. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(6):1284-1292. doi:10.2106/JBJS.E.00942.

18. Iannotti JP, Norris TR. Influence of preoperative factors on outcome of shoulder arthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(2):251-258.

19. Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Rowland CM. Neer hemiarthroplasty and Neer total shoulder arthroplasty in patients fifty years old or less. Long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(4):464-473.

20. Strauss EJ, Roche C, Flurin PH, Wright T, Zuckerman JD. The glenoid in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(5):819-833. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2009.05.008.

21. Cil A, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Nonstandard glenoid components for bone deficiencies in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(7):e149-e157. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.09.023.

22. Denard PJ, Walch G. Current concepts in the surgical management of primary glenohumeral arthritis with a biconcave glenoid. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(11):1589-1598. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.06.017.

23. Gunther SB, Lynch TL. Total shoulder replacement surgery with custom glenoid implants for severe bone deficiency. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(5):675-684. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.03.023.

24. Neer CS, Morrison DS. Glenoid bone-grafting in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70(8):1154-1162.

25. Steinmann SP, Cofield RH. Bone grafting for glenoid deficiency in total shoulder replacement. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(5):361-367. doi:10.1067/mse.2000.106921.

26. Iannotti JP, Frangiamore SJ. Fate of large structural allograft for treatment of severe uncontained glenoid bone deficiency. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012:21(6):765-771. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.08.069.

27. Hill JM, Norris TR. Long-term results of total shoulder arthroplasty following bone-grafting of the glenoid. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(6):877-883.

28. Hsu JE, Ricchetti ET, Huffman GR, Iannotti JP, Glaser DL. Addressing glenoid bone deficiency and asymptomatic posterior erosion in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(9):1298-1308.

29. Chammaa R, Uri O, Lambert S. Primary shoulder arthroplasty using a custom-made hip-inspired implant for the treatment of advanced glenohumeral arthritis in the presence of severe glenoid bone loss. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(1):101-107. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2016.05.027.

30. Stoffelen DV, Eraly K, Debeer P. The use of 3D printing technology in reconstruction of a severe glenoid defect: a case report with 2.5 years of follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(8):e218-e222. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2015.04.006.

31. Gunther SB, Lynch TL. Total shoulder replacement surgery with custom glenoid implants for severe bone deficiency. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(5):675-684. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.03.023.

32. Dines DM, Gulotta L, Craig EV, Dines JS. Novel solution for massive glenoid defects in shoulder arthroplasty: a patient-specific glenoid vault reconstruction system. Am J Orthop. 2017;46(2):104-108.

ABSTRACT

Complex glenoid bone deformities present the treating surgeon with a complex reconstructive challenge. Although glenoid bone loss can be encountered in the primary setting (degenerative, congenital, post-traumatic), severe glenoid bone loss is encountered in most revision total shoulder arthroplasties. Severe glenoid bone loss is treated with various techniques including hemiarthroplasty, eccentric reaming, and glenoid reconstruction with bone autografts and allografts. Despite encouraging short- to mid-term results reported with these reconstruction techniques, the clinical and radiographic outcomes remain inconsistent and the high number of complications is a concern. To overcome this problem, more recently augmented components and patient specific implants were introduced. Using the computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing technology patient-specific implants have been created to reconstruct the glenoid vault in cases of severe glenoid bone loss.

In this article we describe a patient specific glenoid implant, its indication, technical aspects and surgical technique, based on the author's experience as well as a review of the current literature on custom glenoid implants.

Continue to: Total shoulder arthroplasty...

Total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) is an effective operation for providing pain relief and improving function in patients with end-stage degenerative shoulder disease that is nonresponsive to nonoperative treatments.1-4 With the increasing number of arthroplasties performed, and the expanding indication for shoulder arthroplasty, the number of revision shoulder arthroplasties is also increasing.5-14 Complex glenoid bone deformities present the treating surgeon with a complex reconstructive challenge. Although glenoid bone loss can be seen in the primary setting (degenerative, congenital, and post-traumatic), severe glenoid bone loss is encountered mostly in revision TSAs.

Historically, patients with severe glenoid bone loss were treated with a hemiarthroplasty.15-17 However, due to inferior outcomes associated with the use of shoulder hemiarthroplasties compared with TSA in these cases,18-20 various techniques were developed with the aim of realigning the glenoid axis and securing the implants into the deficient glenoid vault.21-25 Options have included eccentric reaming, glenoid reconstruction with bone autografts and allografts, and more recently augmented components and patient-specific implants. Studies with eccentric reaming and reconstruction with bone graft during complex shoulder arthroplasty have reported encouraging short- to mid-term results, but the clinical and radiographic outcomes remain inconsistent, and the high number of complications is a concern.25-28

Complications with these techniques include component loosening, graft resorption, nonunion, failure of graft incorporation, infection, and instability.25-28

Computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing (CAD/CAM) of patient-specific implants have been used successfully by hip arthroplasty surgeons to deal with complex acetabular reconstructions in the setting of severe bone loss. More recently, the same technology has been used to reconstruct the glenoid vault in cases of severe glenoid bone loss.

In this article, we describe a patient-specific glenoid implant, its indication, and both technical aspects and the surgical technique, based on the authors’ experience as well as a review of the current literature on custom glenoid implants.

Continue to: PATIENT-SPECIFIC GLENOID COMPONENT

PATIENT-SPECIFIC GLENOID COMPONENT

The Vault Reconstruction System ([VRS], Zimmer Biomet) is a patient-specific glenoid vault reconstruction system developed with the use of CAD/CAM to address severe glenoid bone loss encountered during shoulder arthroplasty. For several years, the VRS was available only as a custom implant according to the US Food and Drug Administration rules, and therefore its use was limited to a few cases per year. Recently, a 510(k) envelope clearance was granted to use the VRS in reverse TSA to address significant glenoid bone defects.

The VRS is made of porous plasma spray titanium to provide high strength and flexibility, and allows for biologic fixation. This system can accommodate a restricted bone loss envelope of about 50 mm × 50 mm × 35 mm according to the previous experience of the manufacturer in the custom scenario, covering 96% of defects previously addressed. One 6.5-mm nonlocking central screw and a minimum of four 4.75-mm nonlocking or locking peripheral screws are required for optimal fixation of the implant in the native scapula. A custom boss can be added in to enhance fixation in the native scapula when the bone is sufficient. To facilitate the surgical procedure, a trial implant, a bone model of the scapula, and a custom boss reaming guide are 3-dimensional (3-D) and printed in sterilizable material. These are all provided as single-use disposable instruments and can be available for surgeons during both the initial plan review and surgery.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Patients undergo a preoperative fine-cut 2-dimensional computed tomography scan of the scapula and adjacent humerus following a predefined protocol with a slice thickness of 2 mm to 3 mm. An accurate 3-D bone model of the scapula is obtained using a 3-D image processing software system (Figure 1). The 3-D scapular model is used to create a patient-specific glenoid implant proposal that is approved by the surgeon (Figure 2). Implant position, orientation, size, screw trajectory, and recommended bone removal, if necessary, are determined to create a more normal glenohumeral center of rotation and to secure a glenoid implant in severely deficient glenoid bone (Figure 3). Once the implant design is approved by the surgeon, the final patient-specific implant is manufactured.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

The exposure of the glenoid is a critical step for the successful implantation of the patient-specific glenoid implant. Soft tissue and scar tissue around the glenoid must be removed to allow for optimal fit of the custom-made reaming guide. Also, removal of the entire capsulolabral complex on the anteroinferior rim of the glenoid is essential to both enhance glenoid exposure and to allow a perfect fit of the guide to the pathologic bone stock. Attention should be paid during débridement and/or implant removal in case of revision, to make sure that no excessive bone is removed because the patient-specific guide is referenced to this anatomy. Excessive bone removal can change the orientation of the patient-specific guide and ultimately the fixation of the implant. Once the custom-made patient-specific guide is positioned, a 3.2-mm Steinmann pin is placed through the inserter for temporary fixation. The pin should engage or perforate the medial cortical wall to ensure that the subsequent reamer has a stable cannula over which to ream. After the glenoid is reamed, the final implant can be placed in the ideal position according to the preoperative planning. A central 6.5-mm nonlocking central screw and 4.75-mm nonlocking or locking peripheral screws are required to complete the fixation of the implant in the native scapula. Once the patient-specific glenoid component is positioned and strongly fixed to the bone, the glenosphere can be positioned according to the preoperative planning, and the reverse shoulder arthroplasty can be completed in the usual fashion.

CASE EXAMPLES

A 68-year-old woman underwent a TSA for end-stage osteoarthritis in 2000. The implant failed due to a cuff failure. The patient underwent several surgeries, including an open cuff repair, with no success. She had no active elevation preoperatively. Because of the significant glenoid bone loss, a patient-specific glenoid reconstruction was planned. Within 24 months after this surgery, the patient was able to get her hand to her head and elevate to 90º (Figures 4A-4F).

Continue to: In October 2013...

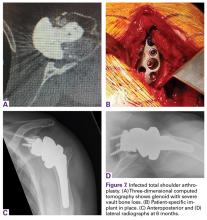

In October 2013, a 68-year-old man underwent a TSA for end-stage osteoarthritis. After 18 months, the implant failed due to active Propionibacterium acnes infection, which required excisional arthroplasty with insertion of an antibiotic spacer. Significant glenoid bone loss (Figure 5) and global soft-tissue deficiency caused substantial disability and led to an indication for a reverse TSA with a patient-specific glenoid vault reconstruction (Figures 6A-6D) after infection eradication. Within 20 months after this surgery, the patient had resumed a satisfactory range of motion (130º forward elevation, 20º external rotation) and outcome.

DISCUSSION

Although glenoid bone loss is often seen in the primary setting (degenerative, congenital, and post-traumatic), severe glenoid bone loss is encountered in most revision TSAs. The best treatment method for massive glenoid bone defects during complex shoulder arthroplasty remains uncertain. Options have included eccentric reaming, glenoid reconstruction with bone allograft and autograft, and more recently augmented components and patient-specific implants.21-25 The advent and availability of CAD/CAM technology have enabled shoulder surgeons to create patient-specific metal solutions to these challenging cases. Currently, only a few reports exist in the literature on patient-specific glenoid components in the setting of severe bone loss.29-32

Chammaa and colleagues29 reported the outcomes of 37 patients with a hip-inspired glenoid component (Total Shoulder Replacement, Stanmore Implants Worldwide). The 5-year results with this implant were promising, with a 16% revision rate and only 1 case of glenoid loosening.

Stoffelen and colleagues30 recently described the successful use of a patient-specific anatomic metal-backed glenoid component for the management of severe glenoid bone loss with excellent results at 2.5 years of follow-up. A different approach was pursued by Gunther and Lynch,31 who reported on 7 patients with a custom inset glenoid implant for deficient glenoid vaults. These circular anatomic, custom-made glenoid components were created with the intention of placing the implants partially inside the glenoid vault and relying partially on sclerotic cortical bone. Despite excellent results at 3 years of follow-up, their use is limited to specific defect geometries and cannot be used in cases of extreme bone loss.

CONCLUSION

We have described the use of a patient-specific glenoid component in 2 patients with severe glenoid bone loss. Despite the satisfactory clinical and short-term radiographic results, we acknowledge that longer-term follow-up is needed to confirm the efficacy of this type of reconstruction. We believe that patient-specific glenoid components represent a valuable addition to the armamentarium of shoulder surgeons who address complex glenoid bone deformities.

ABSTRACT

Complex glenoid bone deformities present the treating surgeon with a complex reconstructive challenge. Although glenoid bone loss can be encountered in the primary setting (degenerative, congenital, post-traumatic), severe glenoid bone loss is encountered in most revision total shoulder arthroplasties. Severe glenoid bone loss is treated with various techniques including hemiarthroplasty, eccentric reaming, and glenoid reconstruction with bone autografts and allografts. Despite encouraging short- to mid-term results reported with these reconstruction techniques, the clinical and radiographic outcomes remain inconsistent and the high number of complications is a concern. To overcome this problem, more recently augmented components and patient specific implants were introduced. Using the computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing technology patient-specific implants have been created to reconstruct the glenoid vault in cases of severe glenoid bone loss.

In this article we describe a patient specific glenoid implant, its indication, technical aspects and surgical technique, based on the author's experience as well as a review of the current literature on custom glenoid implants.

Continue to: Total shoulder arthroplasty...

Total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) is an effective operation for providing pain relief and improving function in patients with end-stage degenerative shoulder disease that is nonresponsive to nonoperative treatments.1-4 With the increasing number of arthroplasties performed, and the expanding indication for shoulder arthroplasty, the number of revision shoulder arthroplasties is also increasing.5-14 Complex glenoid bone deformities present the treating surgeon with a complex reconstructive challenge. Although glenoid bone loss can be seen in the primary setting (degenerative, congenital, and post-traumatic), severe glenoid bone loss is encountered mostly in revision TSAs.

Historically, patients with severe glenoid bone loss were treated with a hemiarthroplasty.15-17 However, due to inferior outcomes associated with the use of shoulder hemiarthroplasties compared with TSA in these cases,18-20 various techniques were developed with the aim of realigning the glenoid axis and securing the implants into the deficient glenoid vault.21-25 Options have included eccentric reaming, glenoid reconstruction with bone autografts and allografts, and more recently augmented components and patient-specific implants. Studies with eccentric reaming and reconstruction with bone graft during complex shoulder arthroplasty have reported encouraging short- to mid-term results, but the clinical and radiographic outcomes remain inconsistent, and the high number of complications is a concern.25-28

Complications with these techniques include component loosening, graft resorption, nonunion, failure of graft incorporation, infection, and instability.25-28

Computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing (CAD/CAM) of patient-specific implants have been used successfully by hip arthroplasty surgeons to deal with complex acetabular reconstructions in the setting of severe bone loss. More recently, the same technology has been used to reconstruct the glenoid vault in cases of severe glenoid bone loss.

In this article, we describe a patient-specific glenoid implant, its indication, and both technical aspects and the surgical technique, based on the authors’ experience as well as a review of the current literature on custom glenoid implants.

Continue to: PATIENT-SPECIFIC GLENOID COMPONENT

PATIENT-SPECIFIC GLENOID COMPONENT

The Vault Reconstruction System ([VRS], Zimmer Biomet) is a patient-specific glenoid vault reconstruction system developed with the use of CAD/CAM to address severe glenoid bone loss encountered during shoulder arthroplasty. For several years, the VRS was available only as a custom implant according to the US Food and Drug Administration rules, and therefore its use was limited to a few cases per year. Recently, a 510(k) envelope clearance was granted to use the VRS in reverse TSA to address significant glenoid bone defects.

The VRS is made of porous plasma spray titanium to provide high strength and flexibility, and allows for biologic fixation. This system can accommodate a restricted bone loss envelope of about 50 mm × 50 mm × 35 mm according to the previous experience of the manufacturer in the custom scenario, covering 96% of defects previously addressed. One 6.5-mm nonlocking central screw and a minimum of four 4.75-mm nonlocking or locking peripheral screws are required for optimal fixation of the implant in the native scapula. A custom boss can be added in to enhance fixation in the native scapula when the bone is sufficient. To facilitate the surgical procedure, a trial implant, a bone model of the scapula, and a custom boss reaming guide are 3-dimensional (3-D) and printed in sterilizable material. These are all provided as single-use disposable instruments and can be available for surgeons during both the initial plan review and surgery.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Patients undergo a preoperative fine-cut 2-dimensional computed tomography scan of the scapula and adjacent humerus following a predefined protocol with a slice thickness of 2 mm to 3 mm. An accurate 3-D bone model of the scapula is obtained using a 3-D image processing software system (Figure 1). The 3-D scapular model is used to create a patient-specific glenoid implant proposal that is approved by the surgeon (Figure 2). Implant position, orientation, size, screw trajectory, and recommended bone removal, if necessary, are determined to create a more normal glenohumeral center of rotation and to secure a glenoid implant in severely deficient glenoid bone (Figure 3). Once the implant design is approved by the surgeon, the final patient-specific implant is manufactured.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

The exposure of the glenoid is a critical step for the successful implantation of the patient-specific glenoid implant. Soft tissue and scar tissue around the glenoid must be removed to allow for optimal fit of the custom-made reaming guide. Also, removal of the entire capsulolabral complex on the anteroinferior rim of the glenoid is essential to both enhance glenoid exposure and to allow a perfect fit of the guide to the pathologic bone stock. Attention should be paid during débridement and/or implant removal in case of revision, to make sure that no excessive bone is removed because the patient-specific guide is referenced to this anatomy. Excessive bone removal can change the orientation of the patient-specific guide and ultimately the fixation of the implant. Once the custom-made patient-specific guide is positioned, a 3.2-mm Steinmann pin is placed through the inserter for temporary fixation. The pin should engage or perforate the medial cortical wall to ensure that the subsequent reamer has a stable cannula over which to ream. After the glenoid is reamed, the final implant can be placed in the ideal position according to the preoperative planning. A central 6.5-mm nonlocking central screw and 4.75-mm nonlocking or locking peripheral screws are required to complete the fixation of the implant in the native scapula. Once the patient-specific glenoid component is positioned and strongly fixed to the bone, the glenosphere can be positioned according to the preoperative planning, and the reverse shoulder arthroplasty can be completed in the usual fashion.

CASE EXAMPLES

A 68-year-old woman underwent a TSA for end-stage osteoarthritis in 2000. The implant failed due to a cuff failure. The patient underwent several surgeries, including an open cuff repair, with no success. She had no active elevation preoperatively. Because of the significant glenoid bone loss, a patient-specific glenoid reconstruction was planned. Within 24 months after this surgery, the patient was able to get her hand to her head and elevate to 90º (Figures 4A-4F).

Continue to: In October 2013...

In October 2013, a 68-year-old man underwent a TSA for end-stage osteoarthritis. After 18 months, the implant failed due to active Propionibacterium acnes infection, which required excisional arthroplasty with insertion of an antibiotic spacer. Significant glenoid bone loss (Figure 5) and global soft-tissue deficiency caused substantial disability and led to an indication for a reverse TSA with a patient-specific glenoid vault reconstruction (Figures 6A-6D) after infection eradication. Within 20 months after this surgery, the patient had resumed a satisfactory range of motion (130º forward elevation, 20º external rotation) and outcome.

DISCUSSION

Although glenoid bone loss is often seen in the primary setting (degenerative, congenital, and post-traumatic), severe glenoid bone loss is encountered in most revision TSAs. The best treatment method for massive glenoid bone defects during complex shoulder arthroplasty remains uncertain. Options have included eccentric reaming, glenoid reconstruction with bone allograft and autograft, and more recently augmented components and patient-specific implants.21-25 The advent and availability of CAD/CAM technology have enabled shoulder surgeons to create patient-specific metal solutions to these challenging cases. Currently, only a few reports exist in the literature on patient-specific glenoid components in the setting of severe bone loss.29-32

Chammaa and colleagues29 reported the outcomes of 37 patients with a hip-inspired glenoid component (Total Shoulder Replacement, Stanmore Implants Worldwide). The 5-year results with this implant were promising, with a 16% revision rate and only 1 case of glenoid loosening.

Stoffelen and colleagues30 recently described the successful use of a patient-specific anatomic metal-backed glenoid component for the management of severe glenoid bone loss with excellent results at 2.5 years of follow-up. A different approach was pursued by Gunther and Lynch,31 who reported on 7 patients with a custom inset glenoid implant for deficient glenoid vaults. These circular anatomic, custom-made glenoid components were created with the intention of placing the implants partially inside the glenoid vault and relying partially on sclerotic cortical bone. Despite excellent results at 3 years of follow-up, their use is limited to specific defect geometries and cannot be used in cases of extreme bone loss.

CONCLUSION

We have described the use of a patient-specific glenoid component in 2 patients with severe glenoid bone loss. Despite the satisfactory clinical and short-term radiographic results, we acknowledge that longer-term follow-up is needed to confirm the efficacy of this type of reconstruction. We believe that patient-specific glenoid components represent a valuable addition to the armamentarium of shoulder surgeons who address complex glenoid bone deformities.

1. Chalmers PN, Gupta AK, Rahman Z, Bruce B, Romeo AA, Nicholson GP. Predictors of early complications of total shoulder arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(4):856-860. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2013.07.002.

2. Deshmukh AV, Koris M, Zurakowski D, Thornhill TS. Total shoulder arthroplasty: long-term survivorship, functional outcome, and quality of life. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(5):471-479. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2005.02.009.

3. Montoya F, Magosch P, Scheiderer B, Lichtenberg S, Melean P, Habermeyer P. Midterm results of a total shoulder prosthesis fixed with a cementless glenoid component. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(5):628-635. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2012.07.005.

4. Torchia ME, Cofield RH, Settergren CR. Total shoulder arthroplasty with the Neer prosthesis: long-term results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6(6):495-505.

5. Antuna SA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Rowland CM. Glenoid revision surgery after total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(3):217-224. doi:10.1067/mse.2001.113961.

6. Chalmers PN, Rahman Z, Romeo AA, Nicholson GP. Early dislocation after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(5):737-744. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.08.015.

7. Farng E, Zingmond D, Krenek L, Soohoo NF. Factors predicting complication rates after primary shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):557-563. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2010.11.005.

8. Farshad M, Grogli M, Catanzaro S, Gerber C. Revision of reversed total shoulder arthroplasty. Indications and outcome. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13(1):160. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-13-160.

9. Fevang BT, Lie SA, Havelin LI, Skredderstuen A, Furnes O. Risk factors for revision after shoulder arthroplasty: 1,825 shoulder arthroplasties from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop. 2009;80(1):83-91.

10. Fox TJ, Cil A, Sperling JW, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Schleck CD, Cofield RH. Survival of the glenoid component in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(6):859-863. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2008.11.020.

11. Rasmussen JV. Outcome and risk of revision following shoulder replacement in patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis. Acta Orthop Suppl. 2014;85(355 suppl):1-23. doi:10.3109/17453674.2014.922007.

12. Rasmussen JV, Polk A, Brorson S, Sorensen AK, Olsen BS. Patient-reported outcome and risk of revision after shoulder replacement for osteoarthritis. 1,209 cases from the Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry, 2006-2010. Acta Orthop. 2014;85(2):117-122. doi:10.3109/17453674.2014.893497.

13. Sajadi KR, Kwon YW, Zuckerman JD. Revision shoulder arthroplasty: an analysis of indications and outcomes. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(2):308-313. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2009.05.016.

14. Singh JA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Revision surgery following total shoulder arthroplasty: analysis of 2588 shoulders over three decades (1976 to 2008). J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(11):1513-1517. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.93B11.26938.

15. Levine WN, Djurasovic M, Glasson JM, Pollock RG, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU. Hemiarthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis: results correlated to degree of glenoid wear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6(5):449-454.

16. Levine WN, Fischer CR, Nguyen D, Flatow EL, Ahmad CS, Bigliani LU. Long-term follow-up of shoulder hemiarthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(22):e164. doi:10.2106/JBJS.K.00603.

17. Lynch JR, Franta AK, Montgomery WH, Lenters TR, Mounce D, Matsen FA. Self-assessed outcome at two to four years after shoulder hemiarthroplasty with concentric glenoid reaming. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(6):1284-1292. doi:10.2106/JBJS.E.00942.

18. Iannotti JP, Norris TR. Influence of preoperative factors on outcome of shoulder arthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(2):251-258.

19. Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Rowland CM. Neer hemiarthroplasty and Neer total shoulder arthroplasty in patients fifty years old or less. Long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(4):464-473.

20. Strauss EJ, Roche C, Flurin PH, Wright T, Zuckerman JD. The glenoid in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(5):819-833. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2009.05.008.

21. Cil A, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Nonstandard glenoid components for bone deficiencies in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(7):e149-e157. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.09.023.

22. Denard PJ, Walch G. Current concepts in the surgical management of primary glenohumeral arthritis with a biconcave glenoid. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(11):1589-1598. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.06.017.

23. Gunther SB, Lynch TL. Total shoulder replacement surgery with custom glenoid implants for severe bone deficiency. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(5):675-684. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.03.023.

24. Neer CS, Morrison DS. Glenoid bone-grafting in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70(8):1154-1162.

25. Steinmann SP, Cofield RH. Bone grafting for glenoid deficiency in total shoulder replacement. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(5):361-367. doi:10.1067/mse.2000.106921.

26. Iannotti JP, Frangiamore SJ. Fate of large structural allograft for treatment of severe uncontained glenoid bone deficiency. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012:21(6):765-771. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.08.069.

27. Hill JM, Norris TR. Long-term results of total shoulder arthroplasty following bone-grafting of the glenoid. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(6):877-883.

28. Hsu JE, Ricchetti ET, Huffman GR, Iannotti JP, Glaser DL. Addressing glenoid bone deficiency and asymptomatic posterior erosion in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(9):1298-1308.

29. Chammaa R, Uri O, Lambert S. Primary shoulder arthroplasty using a custom-made hip-inspired implant for the treatment of advanced glenohumeral arthritis in the presence of severe glenoid bone loss. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(1):101-107. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2016.05.027.

30. Stoffelen DV, Eraly K, Debeer P. The use of 3D printing technology in reconstruction of a severe glenoid defect: a case report with 2.5 years of follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(8):e218-e222. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2015.04.006.

31. Gunther SB, Lynch TL. Total shoulder replacement surgery with custom glenoid implants for severe bone deficiency. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(5):675-684. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.03.023.

32. Dines DM, Gulotta L, Craig EV, Dines JS. Novel solution for massive glenoid defects in shoulder arthroplasty: a patient-specific glenoid vault reconstruction system. Am J Orthop. 2017;46(2):104-108.

1. Chalmers PN, Gupta AK, Rahman Z, Bruce B, Romeo AA, Nicholson GP. Predictors of early complications of total shoulder arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(4):856-860. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2013.07.002.

2. Deshmukh AV, Koris M, Zurakowski D, Thornhill TS. Total shoulder arthroplasty: long-term survivorship, functional outcome, and quality of life. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(5):471-479. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2005.02.009.

3. Montoya F, Magosch P, Scheiderer B, Lichtenberg S, Melean P, Habermeyer P. Midterm results of a total shoulder prosthesis fixed with a cementless glenoid component. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(5):628-635. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2012.07.005.

4. Torchia ME, Cofield RH, Settergren CR. Total shoulder arthroplasty with the Neer prosthesis: long-term results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6(6):495-505.

5. Antuna SA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Rowland CM. Glenoid revision surgery after total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(3):217-224. doi:10.1067/mse.2001.113961.

6. Chalmers PN, Rahman Z, Romeo AA, Nicholson GP. Early dislocation after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(5):737-744. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.08.015.

7. Farng E, Zingmond D, Krenek L, Soohoo NF. Factors predicting complication rates after primary shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):557-563. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2010.11.005.

8. Farshad M, Grogli M, Catanzaro S, Gerber C. Revision of reversed total shoulder arthroplasty. Indications and outcome. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13(1):160. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-13-160.

9. Fevang BT, Lie SA, Havelin LI, Skredderstuen A, Furnes O. Risk factors for revision after shoulder arthroplasty: 1,825 shoulder arthroplasties from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop. 2009;80(1):83-91.

10. Fox TJ, Cil A, Sperling JW, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Schleck CD, Cofield RH. Survival of the glenoid component in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(6):859-863. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2008.11.020.

11. Rasmussen JV. Outcome and risk of revision following shoulder replacement in patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis. Acta Orthop Suppl. 2014;85(355 suppl):1-23. doi:10.3109/17453674.2014.922007.

12. Rasmussen JV, Polk A, Brorson S, Sorensen AK, Olsen BS. Patient-reported outcome and risk of revision after shoulder replacement for osteoarthritis. 1,209 cases from the Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry, 2006-2010. Acta Orthop. 2014;85(2):117-122. doi:10.3109/17453674.2014.893497.

13. Sajadi KR, Kwon YW, Zuckerman JD. Revision shoulder arthroplasty: an analysis of indications and outcomes. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(2):308-313. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2009.05.016.

14. Singh JA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Revision surgery following total shoulder arthroplasty: analysis of 2588 shoulders over three decades (1976 to 2008). J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(11):1513-1517. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.93B11.26938.

15. Levine WN, Djurasovic M, Glasson JM, Pollock RG, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU. Hemiarthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis: results correlated to degree of glenoid wear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6(5):449-454.

16. Levine WN, Fischer CR, Nguyen D, Flatow EL, Ahmad CS, Bigliani LU. Long-term follow-up of shoulder hemiarthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(22):e164. doi:10.2106/JBJS.K.00603.

17. Lynch JR, Franta AK, Montgomery WH, Lenters TR, Mounce D, Matsen FA. Self-assessed outcome at two to four years after shoulder hemiarthroplasty with concentric glenoid reaming. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(6):1284-1292. doi:10.2106/JBJS.E.00942.

18. Iannotti JP, Norris TR. Influence of preoperative factors on outcome of shoulder arthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(2):251-258.

19. Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Rowland CM. Neer hemiarthroplasty and Neer total shoulder arthroplasty in patients fifty years old or less. Long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(4):464-473.

20. Strauss EJ, Roche C, Flurin PH, Wright T, Zuckerman JD. The glenoid in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(5):819-833. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2009.05.008.

21. Cil A, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Nonstandard glenoid components for bone deficiencies in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(7):e149-e157. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.09.023.

22. Denard PJ, Walch G. Current concepts in the surgical management of primary glenohumeral arthritis with a biconcave glenoid. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(11):1589-1598. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.06.017.

23. Gunther SB, Lynch TL. Total shoulder replacement surgery with custom glenoid implants for severe bone deficiency. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(5):675-684. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.03.023.

24. Neer CS, Morrison DS. Glenoid bone-grafting in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70(8):1154-1162.

25. Steinmann SP, Cofield RH. Bone grafting for glenoid deficiency in total shoulder replacement. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(5):361-367. doi:10.1067/mse.2000.106921.

26. Iannotti JP, Frangiamore SJ. Fate of large structural allograft for treatment of severe uncontained glenoid bone deficiency. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012:21(6):765-771. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.08.069.

27. Hill JM, Norris TR. Long-term results of total shoulder arthroplasty following bone-grafting of the glenoid. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(6):877-883.

28. Hsu JE, Ricchetti ET, Huffman GR, Iannotti JP, Glaser DL. Addressing glenoid bone deficiency and asymptomatic posterior erosion in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(9):1298-1308.

29. Chammaa R, Uri O, Lambert S. Primary shoulder arthroplasty using a custom-made hip-inspired implant for the treatment of advanced glenohumeral arthritis in the presence of severe glenoid bone loss. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(1):101-107. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2016.05.027.

30. Stoffelen DV, Eraly K, Debeer P. The use of 3D printing technology in reconstruction of a severe glenoid defect: a case report with 2.5 years of follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(8):e218-e222. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2015.04.006.

31. Gunther SB, Lynch TL. Total shoulder replacement surgery with custom glenoid implants for severe bone deficiency. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(5):675-684. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.03.023.

32. Dines DM, Gulotta L, Craig EV, Dines JS. Novel solution for massive glenoid defects in shoulder arthroplasty: a patient-specific glenoid vault reconstruction system. Am J Orthop. 2017;46(2):104-108.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- With the increasing number of arthroplasties performed, and the expanding indication for shoulder arthroplasty, the number of revision shoulder arthroplasties is also increasing.

- Complex glenoid bone defects are sometimes encountered in revision shoulder arthroplasties.

- Glenoid reconstructions with bone graft have reported encouraging short- to mid-term results, but the high number of complications is a concern.

- Using the CAD/CAM technology patient-specific glenoid components have been created to reconstruct the glenoid vault in cases of severe glenoid bone loss.

- Short-term clinical and radiographic results of patient-specific glenoid components are encouraging, however longer-term follow-up are needed to confirm the efficacy of this type of reconstruction.

Shoulder Arthroplasty in Cases of Significant Bone Loss: An Overview

Over the past few decades, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of shoulder arthroplasties performed around the world. This increase is the result of an aging and increasingly more active population, better implant technology, and the advent of reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) for rotator cuff arthropathy. Additionally, as the indications for RSA have expanded to include pathologies such as rotator cuff insufficiency, chronic instabilities, trauma, and tumors, the number of arthroplasties will continue to increase. Although the results of most arthroplasties are good and predictable, any glenoid and/or humeral bone deficiencies can have detrimental effects on the clinical outcomes of these procedures. Bone loss becomes more of a problem in revision cases, and, as the number of primary arthroplasties increases, it follows that the number of revision procedures will also increase.

Many of the disease- or procedure-specific processes indicated for shoulder arthroplasty have predictable patterns of bone loss, especially on the glenoid side. Walch and colleagues1 and Bercik and colleagues2 made us aware that many patients with primary osteoarthritis have significant glenoid bone deformity. Similarly, there have been a number of first- and second-generation classification systems for delineating glenoid deformity in rotator cuff tear arthropathy and in revision settings. In revision settings, both glenoid and humeral bone deficiencies can occur as a result of implant removal, iatrogenic fracture, and even infection. Each of these bone loss patterns must be recognized and treated appropriately for the best surgical outcome.

The articles in this month of The American Journal of Orthopedics address the most up-to-date concepts and solutions regarding both humeral and glenoid bone loss in shoulder arthroplasty of all types.

HUMERAL BONE LOSS

Humeral bone loss is typically encountered in proximal humerus fractures, in revision surgery necessitating humeral component removal, and, less commonly, in tumors and infection.

In many displaced proximal humeral fractures indicated for shoulder arthroplasty, the bone is comminuted with displacement of the lesser and greater tuberosities. In these situations, failure of tuberosity healing may result in loss of rotator cuff function with loss of elevation, rotation, and even instability. Humeral shortening can also occur as a result of bone loss and can compromise deltoid function by loss of proper muscle tension, leading to instability, dysfunction, or both. In addition to possible instability, humeral shortening with metaphyseal bone loss can adversely affect long-term fixation of the humeral component, leading to stem loosening or failure. Cuff and colleagues3 showed significantly more rotational micromotion in cases lacking metaphyseal support, leading to aseptic loosening of the humeral stem.

Humeral bone loss can also result from humeral stem component removal in revision shoulder arthroplasty for infection, component failure or loosening, and even periprosthetic fracture resulting from surgery or trauma.

For the surgeon, humeral bone loss can create a complex set of circumstances related to rotator cuff attachment failure, soft-tissue balancing effects, and component fixation issues. Any such issue must be recognized and addressed for best outcomes. Best results can be obtained with preoperative imaging, planning, use of bone graft techniques, proximal humeral allografts, and, more recently, modular and patient-specific implants. All of these issues are discussed comprehensively in the articles this month.

Continue to: GLENOID BONE LOSS

GLENOID BONE LOSS

Proper glenoid component placement with durable fixation is crucial for success in anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty and RSA. Glenoid bone deformity and loss can result from intrinsic deformity characteristics seen in primary osteoarthritis, cuff tear arthropathy, or glenoid component removal in revision situations and infection. These bone deformity complications can be extremely difficult to treat and in some cases lead to catastrophic failure of the index arthroplasty.

We are now aware that one key to success in the face of moderate to severe deformity is proper recognition. Newer imaging techniques, including 2-dimensional (2-D) computed tomography (CT) and 3-dimensional (3-D) modeling and surgical planning software tools, which are outlined in an upcoming article, have given surgeons important new instruments that can help in treating these difficult cases.

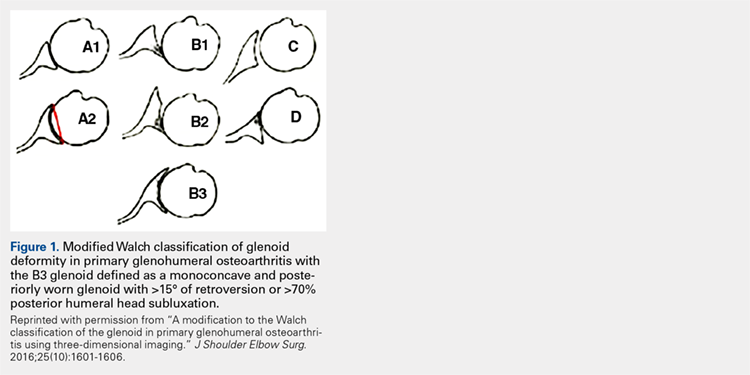

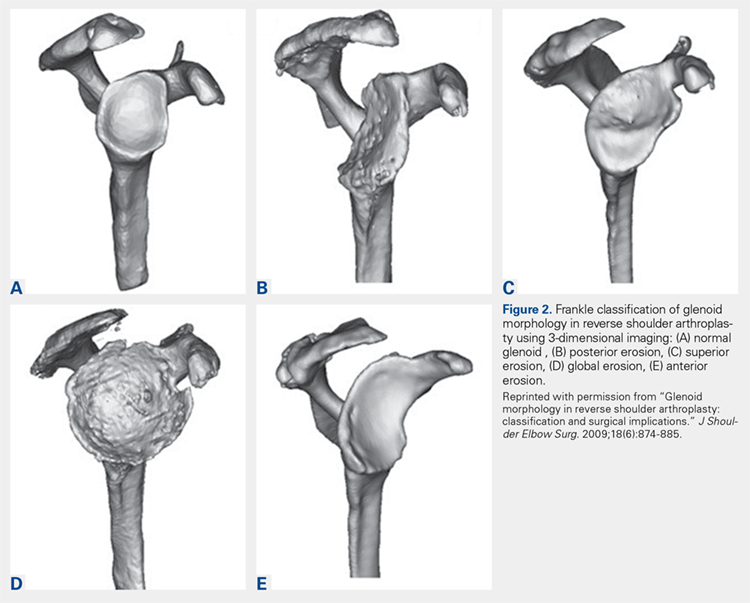

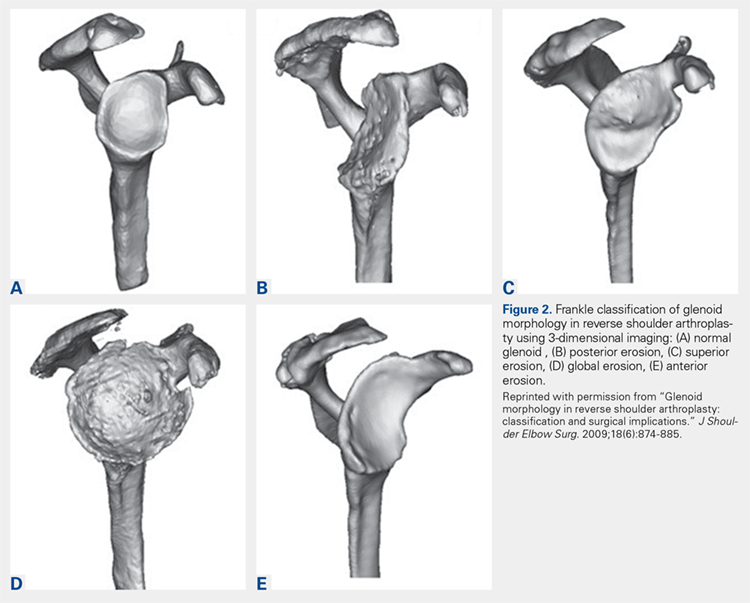

Glenoid bone deformity in primary osteoarthritis was well delineated in the 1999 seminal study of CT changes by Walch and colleagues.1 The Walch classification system, which characterized glenoid morphology based on 2-D CT findings, was recently upgraded, based on 3-D imaging technology, to include Walch B3 and D patterns (Figure 1).2 Recognition of certain primary deformities in osteoarthritis has led to increased use of RSA in some cases of Walch B2, B3, and C deformities with substantial glenoid retroversion and/or humeral head subluxation.4

In cases of rotator cuff tear arthropathy, glenoid bone deformities are well described with several classification systems based on degree and dimension of bone insufficiency. The Hamada classification system defines the degree of medial glenoid erosion and superior bone loss, as well as acetabularization of the acromion in 5 grades; 5 Rispoli and colleagues6 defined and graded the degree of medicalization of the glenohumeral joint based on degree of subchondral plate erosion; and Visotsky and colleagues7 based their classification system on wear patterns of bone loss, alignment, and concomitant soft-tissue insufficiencies leading to instability and rotation loss.

In severe glenoid bone deficiency after glenoid component removal, Antuna and colleagues8 described the classic findings related to medial bone loss, anterior and posterior wall failure, and combinations thereof.

Continue to: All these classification systems...

All these classification systems are based on the 2-D appearance of the glenoid and should be considered cautiously. The glenoid is a complex 3-D structure that can be affected by any number of disease processes, trauma, and surgical intervention. Using more modern CT techniques and 3-D imaging, we now know that many deformities previously classified as unidirectional are, instead, complex and multidirectional.

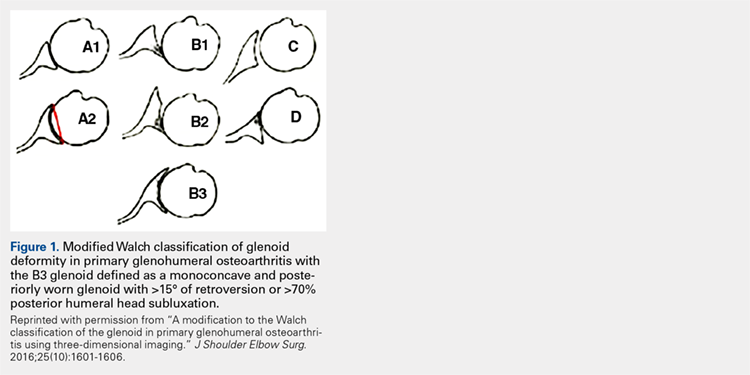

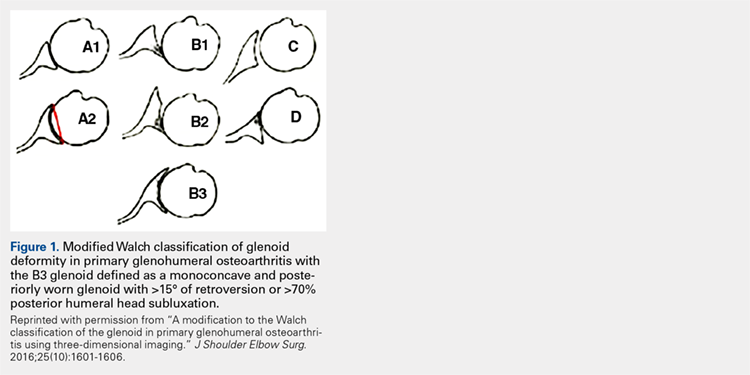

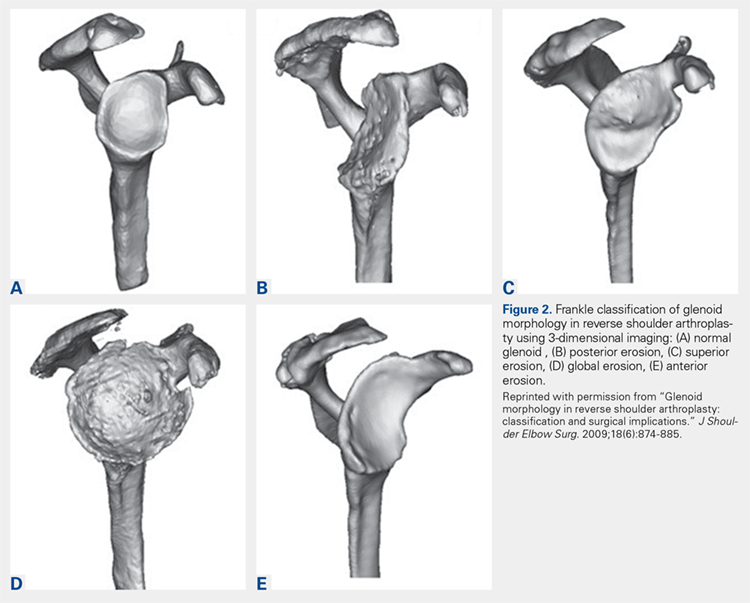

Frankle and colleagues9 developed a classification based more 3-D CT models which has further classified severe glenoid vault deformities in relation to direction and degree of bone loss (Figures 2A-2E). Using this system, they were better able to determine degree and direction of deformity than in previous 2-D evaluations, and they were able to determine the amount of glenoid vault bone available for baseplate fixation. Scalise and colleagues10 further defined the influence of such 3-D planning in total shoulder arthroplasty.

With knowledge of these classification systems and use of contemporary imaging systems, shoulder arthroplasty in cases of severe glenoid deficiency can be more successful. Potentially, we can improve outcomes even more in the more severe cases of bone loss with use of patient-specific planning tools, including the guides and patient-specific implants that are now readily available with many implant systems.11

Preoperative planning tools, bone-grafting techniques, augmented and specialized glenoid and humeral implants, and patient-specific implants are discussed this month to give our readers a comprehensive review of the latest concepts in shoulder arthroplasty in cases of significant bone loss or deformity.

This month of The American Journal of Orthopedics presents the most current and cutting-edge solutions for humeral and glenoid bone deformities and deficiencies in contemporary shoulder arthroplasties.

1. Walch G, Badet R, Boulahia A, Khoury A. Morphologic study of the glenoid in primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14(6):756-760.

2. Bercik MJ, Kruse K 2nd, Yalizis M, Gauci MO, Chaoui J, Walch G. A modification to the Walch classification of the glenoid in primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis using three-dimensional imaging. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(10):1601-1606.

3. Cuff D, Levy JC, Gutiérrez S, Frankle M. Torsional stability of modular and non-modular reverse shoulder humeral components in a proximal humeral bone loss model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):646-651.

4. Denard PJ, Walch G. Current concepts in the surgical management of primary glenohumeral arthritis with a biconcave glenoid. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(11):1589-1598.

5. Hamada K, Fukuda H, Mikasa M, Kobayashi Y. Roentgenographic findings in massive rotator cuff tears. A long-term observation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;(254):92-96.

6. Rispoli D, Sperling JW, Athwal GS, Schleck CD, Cofield RH. Humeral head replacement for the treatment of osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(12):2637-2644.

7. Visotsky JL, Basamania C, Seebauer L, Rockwood CA, Jensen KL. Cuff tear arthropathy: pathogenesis, classification, and algorithm for treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(suppl 2):35-40.

8. Antuna SA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Rowland CM. Glenoid revision surgery after total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(3):217-224.

9. Frankle MA, Teramoto A, Luo ZP, Levy JC, Pupello D. Glenoid morphology in reverse shoulder arthroplasty: classification and surgical implications. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(6):874-885.

10. Scalise JJ, Codsi MJ, Bryan J, Brems JJ, Iannotti JP. The influence of three-dimensional computed tomography images of the shoulder in preoperative planning for total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(11):2438-2445.

11. Dines DM, Gulotta L, Craig EV, Dines JS. Novel solution for massive glenoid defects in shoulder arthroplasty: a patient-specific glenoid vault reconstruction system. Am J Orthop. 2017;46(2):104-108.

Over the past few decades, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of shoulder arthroplasties performed around the world. This increase is the result of an aging and increasingly more active population, better implant technology, and the advent of reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) for rotator cuff arthropathy. Additionally, as the indications for RSA have expanded to include pathologies such as rotator cuff insufficiency, chronic instabilities, trauma, and tumors, the number of arthroplasties will continue to increase. Although the results of most arthroplasties are good and predictable, any glenoid and/or humeral bone deficiencies can have detrimental effects on the clinical outcomes of these procedures. Bone loss becomes more of a problem in revision cases, and, as the number of primary arthroplasties increases, it follows that the number of revision procedures will also increase.

Many of the disease- or procedure-specific processes indicated for shoulder arthroplasty have predictable patterns of bone loss, especially on the glenoid side. Walch and colleagues1 and Bercik and colleagues2 made us aware that many patients with primary osteoarthritis have significant glenoid bone deformity. Similarly, there have been a number of first- and second-generation classification systems for delineating glenoid deformity in rotator cuff tear arthropathy and in revision settings. In revision settings, both glenoid and humeral bone deficiencies can occur as a result of implant removal, iatrogenic fracture, and even infection. Each of these bone loss patterns must be recognized and treated appropriately for the best surgical outcome.

The articles in this month of The American Journal of Orthopedics address the most up-to-date concepts and solutions regarding both humeral and glenoid bone loss in shoulder arthroplasty of all types.

HUMERAL BONE LOSS

Humeral bone loss is typically encountered in proximal humerus fractures, in revision surgery necessitating humeral component removal, and, less commonly, in tumors and infection.

In many displaced proximal humeral fractures indicated for shoulder arthroplasty, the bone is comminuted with displacement of the lesser and greater tuberosities. In these situations, failure of tuberosity healing may result in loss of rotator cuff function with loss of elevation, rotation, and even instability. Humeral shortening can also occur as a result of bone loss and can compromise deltoid function by loss of proper muscle tension, leading to instability, dysfunction, or both. In addition to possible instability, humeral shortening with metaphyseal bone loss can adversely affect long-term fixation of the humeral component, leading to stem loosening or failure. Cuff and colleagues3 showed significantly more rotational micromotion in cases lacking metaphyseal support, leading to aseptic loosening of the humeral stem.

Humeral bone loss can also result from humeral stem component removal in revision shoulder arthroplasty for infection, component failure or loosening, and even periprosthetic fracture resulting from surgery or trauma.

For the surgeon, humeral bone loss can create a complex set of circumstances related to rotator cuff attachment failure, soft-tissue balancing effects, and component fixation issues. Any such issue must be recognized and addressed for best outcomes. Best results can be obtained with preoperative imaging, planning, use of bone graft techniques, proximal humeral allografts, and, more recently, modular and patient-specific implants. All of these issues are discussed comprehensively in the articles this month.

Continue to: GLENOID BONE LOSS

GLENOID BONE LOSS

Proper glenoid component placement with durable fixation is crucial for success in anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty and RSA. Glenoid bone deformity and loss can result from intrinsic deformity characteristics seen in primary osteoarthritis, cuff tear arthropathy, or glenoid component removal in revision situations and infection. These bone deformity complications can be extremely difficult to treat and in some cases lead to catastrophic failure of the index arthroplasty.

We are now aware that one key to success in the face of moderate to severe deformity is proper recognition. Newer imaging techniques, including 2-dimensional (2-D) computed tomography (CT) and 3-dimensional (3-D) modeling and surgical planning software tools, which are outlined in an upcoming article, have given surgeons important new instruments that can help in treating these difficult cases.

Glenoid bone deformity in primary osteoarthritis was well delineated in the 1999 seminal study of CT changes by Walch and colleagues.1 The Walch classification system, which characterized glenoid morphology based on 2-D CT findings, was recently upgraded, based on 3-D imaging technology, to include Walch B3 and D patterns (Figure 1).2 Recognition of certain primary deformities in osteoarthritis has led to increased use of RSA in some cases of Walch B2, B3, and C deformities with substantial glenoid retroversion and/or humeral head subluxation.4

In cases of rotator cuff tear arthropathy, glenoid bone deformities are well described with several classification systems based on degree and dimension of bone insufficiency. The Hamada classification system defines the degree of medial glenoid erosion and superior bone loss, as well as acetabularization of the acromion in 5 grades; 5 Rispoli and colleagues6 defined and graded the degree of medicalization of the glenohumeral joint based on degree of subchondral plate erosion; and Visotsky and colleagues7 based their classification system on wear patterns of bone loss, alignment, and concomitant soft-tissue insufficiencies leading to instability and rotation loss.

In severe glenoid bone deficiency after glenoid component removal, Antuna and colleagues8 described the classic findings related to medial bone loss, anterior and posterior wall failure, and combinations thereof.

Continue to: All these classification systems...

All these classification systems are based on the 2-D appearance of the glenoid and should be considered cautiously. The glenoid is a complex 3-D structure that can be affected by any number of disease processes, trauma, and surgical intervention. Using more modern CT techniques and 3-D imaging, we now know that many deformities previously classified as unidirectional are, instead, complex and multidirectional.

Frankle and colleagues9 developed a classification based more 3-D CT models which has further classified severe glenoid vault deformities in relation to direction and degree of bone loss (Figures 2A-2E). Using this system, they were better able to determine degree and direction of deformity than in previous 2-D evaluations, and they were able to determine the amount of glenoid vault bone available for baseplate fixation. Scalise and colleagues10 further defined the influence of such 3-D planning in total shoulder arthroplasty.

With knowledge of these classification systems and use of contemporary imaging systems, shoulder arthroplasty in cases of severe glenoid deficiency can be more successful. Potentially, we can improve outcomes even more in the more severe cases of bone loss with use of patient-specific planning tools, including the guides and patient-specific implants that are now readily available with many implant systems.11

Preoperative planning tools, bone-grafting techniques, augmented and specialized glenoid and humeral implants, and patient-specific implants are discussed this month to give our readers a comprehensive review of the latest concepts in shoulder arthroplasty in cases of significant bone loss or deformity.

This month of The American Journal of Orthopedics presents the most current and cutting-edge solutions for humeral and glenoid bone deformities and deficiencies in contemporary shoulder arthroplasties.

Over the past few decades, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of shoulder arthroplasties performed around the world. This increase is the result of an aging and increasingly more active population, better implant technology, and the advent of reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) for rotator cuff arthropathy. Additionally, as the indications for RSA have expanded to include pathologies such as rotator cuff insufficiency, chronic instabilities, trauma, and tumors, the number of arthroplasties will continue to increase. Although the results of most arthroplasties are good and predictable, any glenoid and/or humeral bone deficiencies can have detrimental effects on the clinical outcomes of these procedures. Bone loss becomes more of a problem in revision cases, and, as the number of primary arthroplasties increases, it follows that the number of revision procedures will also increase.

Many of the disease- or procedure-specific processes indicated for shoulder arthroplasty have predictable patterns of bone loss, especially on the glenoid side. Walch and colleagues1 and Bercik and colleagues2 made us aware that many patients with primary osteoarthritis have significant glenoid bone deformity. Similarly, there have been a number of first- and second-generation classification systems for delineating glenoid deformity in rotator cuff tear arthropathy and in revision settings. In revision settings, both glenoid and humeral bone deficiencies can occur as a result of implant removal, iatrogenic fracture, and even infection. Each of these bone loss patterns must be recognized and treated appropriately for the best surgical outcome.

The articles in this month of The American Journal of Orthopedics address the most up-to-date concepts and solutions regarding both humeral and glenoid bone loss in shoulder arthroplasty of all types.

HUMERAL BONE LOSS

Humeral bone loss is typically encountered in proximal humerus fractures, in revision surgery necessitating humeral component removal, and, less commonly, in tumors and infection.

In many displaced proximal humeral fractures indicated for shoulder arthroplasty, the bone is comminuted with displacement of the lesser and greater tuberosities. In these situations, failure of tuberosity healing may result in loss of rotator cuff function with loss of elevation, rotation, and even instability. Humeral shortening can also occur as a result of bone loss and can compromise deltoid function by loss of proper muscle tension, leading to instability, dysfunction, or both. In addition to possible instability, humeral shortening with metaphyseal bone loss can adversely affect long-term fixation of the humeral component, leading to stem loosening or failure. Cuff and colleagues3 showed significantly more rotational micromotion in cases lacking metaphyseal support, leading to aseptic loosening of the humeral stem.

Humeral bone loss can also result from humeral stem component removal in revision shoulder arthroplasty for infection, component failure or loosening, and even periprosthetic fracture resulting from surgery or trauma.

For the surgeon, humeral bone loss can create a complex set of circumstances related to rotator cuff attachment failure, soft-tissue balancing effects, and component fixation issues. Any such issue must be recognized and addressed for best outcomes. Best results can be obtained with preoperative imaging, planning, use of bone graft techniques, proximal humeral allografts, and, more recently, modular and patient-specific implants. All of these issues are discussed comprehensively in the articles this month.

Continue to: GLENOID BONE LOSS

GLENOID BONE LOSS

Proper glenoid component placement with durable fixation is crucial for success in anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty and RSA. Glenoid bone deformity and loss can result from intrinsic deformity characteristics seen in primary osteoarthritis, cuff tear arthropathy, or glenoid component removal in revision situations and infection. These bone deformity complications can be extremely difficult to treat and in some cases lead to catastrophic failure of the index arthroplasty.

We are now aware that one key to success in the face of moderate to severe deformity is proper recognition. Newer imaging techniques, including 2-dimensional (2-D) computed tomography (CT) and 3-dimensional (3-D) modeling and surgical planning software tools, which are outlined in an upcoming article, have given surgeons important new instruments that can help in treating these difficult cases.

Glenoid bone deformity in primary osteoarthritis was well delineated in the 1999 seminal study of CT changes by Walch and colleagues.1 The Walch classification system, which characterized glenoid morphology based on 2-D CT findings, was recently upgraded, based on 3-D imaging technology, to include Walch B3 and D patterns (Figure 1).2 Recognition of certain primary deformities in osteoarthritis has led to increased use of RSA in some cases of Walch B2, B3, and C deformities with substantial glenoid retroversion and/or humeral head subluxation.4

In cases of rotator cuff tear arthropathy, glenoid bone deformities are well described with several classification systems based on degree and dimension of bone insufficiency. The Hamada classification system defines the degree of medial glenoid erosion and superior bone loss, as well as acetabularization of the acromion in 5 grades; 5 Rispoli and colleagues6 defined and graded the degree of medicalization of the glenohumeral joint based on degree of subchondral plate erosion; and Visotsky and colleagues7 based their classification system on wear patterns of bone loss, alignment, and concomitant soft-tissue insufficiencies leading to instability and rotation loss.

In severe glenoid bone deficiency after glenoid component removal, Antuna and colleagues8 described the classic findings related to medial bone loss, anterior and posterior wall failure, and combinations thereof.

Continue to: All these classification systems...

All these classification systems are based on the 2-D appearance of the glenoid and should be considered cautiously. The glenoid is a complex 3-D structure that can be affected by any number of disease processes, trauma, and surgical intervention. Using more modern CT techniques and 3-D imaging, we now know that many deformities previously classified as unidirectional are, instead, complex and multidirectional.

Frankle and colleagues9 developed a classification based more 3-D CT models which has further classified severe glenoid vault deformities in relation to direction and degree of bone loss (Figures 2A-2E). Using this system, they were better able to determine degree and direction of deformity than in previous 2-D evaluations, and they were able to determine the amount of glenoid vault bone available for baseplate fixation. Scalise and colleagues10 further defined the influence of such 3-D planning in total shoulder arthroplasty.

With knowledge of these classification systems and use of contemporary imaging systems, shoulder arthroplasty in cases of severe glenoid deficiency can be more successful. Potentially, we can improve outcomes even more in the more severe cases of bone loss with use of patient-specific planning tools, including the guides and patient-specific implants that are now readily available with many implant systems.11