User login

Achieving Excellence in Hepatitis B Virus Care for Veterans in the VHA (FULL)

Hepatitis B is a viral infection caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV), which is transmitted through percutaneous (ie, puncture through the skin) or mucosal (ie, direct contact with mucous membranes) exposure to infectious blood or body fluids. Hepatitis B virus can cause chronic infection, resulting in cirrhosis of the liver, liver cancer, liver failure, and death. Persons with chronic infection also serve as the main reservoir for continued HBV transmission.1

Individuals at highest risk for infection include those born in geographic regions with a high prevalence of HBV, those with sexual partners or household contacts with chronic HBV infection, men who have sex with men (MSM), those with HIV, and individuals who inject drugs. Pregnant women also are a population of concern given the potential for perinatal transmission.2

About 850,000 to 2.2 million people in the US (about 0.3% of the civilian US population) are chronically infected with HBV.3 The prevalence of chronic HBV is much higher (10%-19%) among Asian Americans, those of Pacific Island descent, and other immigrant populations from highly endemic countries.4 In the US, HBV is responsible for 2,000 to 4,000 preventable deaths annually, primarily from cirrhosis, liver cancer, and hepatic failure.4 In the civilian US population, reported cases of acute HBV decreased 0.3% from 2011 to 2012, increased 5.4% in 2013 with an 8.5% decrease in 2014, and a 20.7% increase in 2015.4 Injection drug use is likely driving the most recent increase.5

Not all individuals exposed to HBV will develop chronic infection, and the risk of chronic HBV infection depends on an individual’s age at the time of exposure. For example, about 95% of infants exposed to HBV perinatally will develop a chronic infection compared with 5% of exposed adults.6 Of those with chronic HBV, a small proportion will develop cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with increasing risk as viral DNA concentrations increase. Additional risk factors for cirrhosis include being older, male, having a persistently elevated alanine transaminase, viral superinfections, HBV reversion/reactivation, genotype, and various markers of disease severity (HCC).6 Of note, chronic HBV infection may cause HCC even in the absence of cirrhosis.7 In addition, immunosuppression (eg, from cancer chemotherapy) may allow HBV reactivation, which may result in fulminant hepatic failure. In the Veterans Health Affairs (VHA) health care system, about 17% of those with known chronic HBV also carry a diagnosis of cirrhosis.

Vaccination is the mainstay of efforts to prevent HBV infection. The first commercially available HBV vaccine was approved by the FDA in 1981, with subsequent FDA approval in 1986 of a vaccine manufactured using recombinant DNA technology.8 In 1991, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended universal childhood vaccination for HBV, with subsequent recommendations for vaccination of adolescents and adults in high-risk groups in 1995, and in 1999 all remaining unvaccinated children aged ≤ 19 years.9 Military policy has been to provide hepatitis B immunization to personnel assigned to the Korean peninsula since 1986 and to all recruits since 2001.10

Following publication of an Institute of Medicine/National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) report, in 2011 the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) released the first National Viral Hepatitis Action Plan.11 The current HHS Action Plan, along with the NASEM National Strategy for the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C: Phase Two Report, commissioned by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), outlines a national strategy to prevent new viral hepatitis infections; reduce deaths and improve the health of people living with viral hepatitis; reduce viral hepatitis health disparities; and coordinate, monitor, and report on implementation of viral hepatitis activities.12 The VA is a critical partner in this federal collaborative effort to achieve excellence in viral hepatitis care.

In August 2016, the HIV, Hepatitis, and Related Conditions Programs in the VA Office of Specialty Care Services convened a National Hepatitis B Working Group consisting of VA subject matter experts (SMEs) and representatives from the VA Central Office stakeholder program offices, with a charge of developing a strategic plan to ensure excellence in HBV prevention, care, and management across the VHA. The task included addressing supportive processes and barriers at each level of the organization through a public health framework and using a population health management approach.

The VA National Strategic Plan for Excellence in HBV Care was focused on the following overarching aims:

- Characterizing the current state of care for veterans with HBV in VA care;

- Developing and disseminating clinical guidance on high-quality care for patients with HBV;

- Developing population data and informatics tools to streamline the identification and monitoring of patients with chronic HBV; and

- Evaluating VHA care for patients with HBV over time.

Care for Veterans With HBV at the VA

The VA health care system is America’s largest integrated health care system, providing care at 1,243 health care facilities, including 170 medical centers and 1,063 outpatient sites of care serving 9 million enrolled veterans each year.13 As of January 2018, there were 10,743 individuals with serologic evidence for chronic HBV infection in VA care, based on a definition of 2 or more detectable surface antigen (sAg) or hepatitis B DNA tests recorded at least 6 months apart.1 About 2,000 additional VA patients have a history of a single positive sAg test. These patients have unclear HBV status and require a second sAg test to determine whether they have a chronic infection.

The prevalence of HBV infection among veterans in VA care is slightly higher than that in the US civilian population at 0.4%.14 Studies of selected subpopulations of veterans have found high seropositivity of prior or chronic HBV infection among homeless veterans and veterans admitted to a psychiatric hospital.15,16 The data from 2015 suggest that homeless veterans have a chronic HBV infection rate of 1.0%.14 Of those with known chronic HBV infection, the plurality are white (40.4%) or African American (40.2%), male (92.4%), with a mean age of 59.9 (SD 12.0) years. According to National HIV, Hepatitis and Related Conditions Data and Analysis Group personal correspondence, the geographic territories with the largest chronic HBV caseload include the Southeast, Gulf Coast, and West Coast. As of January 2018, 1,210 veterans in care have HBV-related cirrhosis.

HBV Screening in VA

The current VA HBV screening guidelines follow those of the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).17 HBV screening is recommended for unvaccinated individuals in high-risk groups, such as patients with HIV or hepatitis C virus (HCV), those on hemodialysis, those with elevated alanine transaminase/aspartate transaminase of unknown etiology, those on immunosuppressive therapy, injection drug users, the MSM population, people with household contact with an HBV-infected person, people born to an HBV-infected mother, those with risk factors for HBV exposure prior to vaccination, pregnant women, and people born in highly endemic areas regardless of vaccination status.2 The VHA recommends against standardized risk assessment and laboratory screening for HBV infection in the asymptomatic general patient population. However, if risk factors become known during the course of providing usual clinical care, then laboratory screening should be considered.2

Of the 6.1 million VHA users

HBV Care and VA Antiviral Treatment

In a study of an HBV care cascade, Serper and colleagues reviewed a cohort of veterans in the VA with HBV. About 50% of the patients with known chronic HBV in the VA system from 1999 to 2013 had received infectious diseases or gastroenterology/hepatology specialty care in the previous 2 years.19 Follow-up data from the National HIV, Hepatitis and Related Conditions Data and Analysis Group indicated that this remains the case: 52.3% of patients with documented chronic HBV had received specialty care from VA sources in the prior 2 years. Serper and colleagues also reported that among veterans in VHA care with chronic HBV infection and cirrhosis from 1999 to 2013, annual imaging was < 50%, and initiation of antiviral treatment was only 39%. Antiviral therapy and liver imaging were both independently associated with lower mortality for patients with HBV and cirrhosis.19

A review of studies that evaluated the delivery of care for patients with HBV in U.S. civilian populations, including retrospective reviews of private payer claims databases and chart reviews, the Kaiser Permanente claims database, and community gastrointestinal (GI) practice chart reviews, revealed similar practice patterns with those in the VA.20 Across the US, rates of antiviral therapy and HCC surveillance for those with HBV cirrhosis were low, ranging from 14% to 50% and 19% to 60%, respectively. Several of these studies also found that being seen by an HBV specialist was associated with improved care.20

Antiviral treatment of individuals with cirrhosis and chronic HBV infection can reduce the risk of progression to decompensated cirrhosis and liver cancer. Among current VA patients with HBV cirrhosis, 62.4% received at least 1 month of HBV antiviral medication in the prior year. Additionally, biannual liver imaging is recommended in this population to screen for the development of HCC. According to National HIV, Hepatitis and Related Conditions Data and Analysis Group personal correspondence, nationally, 51.2% of individuals with HBV cirrhosis had received at least one instance of liver imaging within the past 6 months, and 71.2% received imaging within the past 12 months.

Prevention of HBV Infection and Sequelae

Vaccination rates in the US vary by age group, with higher immunization rates among those born after 1991 than the rates of those born earlier. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 1988 to 2012 reported 33% immunity among veterans aged < 50 years and 6% among those aged ≥ 50 years.21 In addition to individuals who received childhood vaccination in the 1990s, all new military recruits assigned to the Korean Peninsula were vaccinated for HBV as of 1986, and those joining the military after 2002 received mandatory vaccination.

The VA follows the ACIP/CDC hepatitis B immunization guidelines.22-24 The VA currently recommends HBV immunization among previously unvaccinated adults at increased risk of contracting HBV infection and for any other adult who is seeking protection from HBV infection. The VA also offers general recommendations for prevention of transmission between veterans with known chronic HBV to their household, sexual, or drug-using partners. Transmission prevention guidelines also provide recommendations for vaccination of pregnant women with HBV risk factors and women at risk for HBV infection during pregnancy.22

HBV Care Guidance

One of the core tasks of the VA National Hepatitis B Working Group, given its broad, multidisciplinary expertise in HBV, was developing general clinical guidelines for the provision of high-quality care for patients with HBV. The group reviewed current literature and scientific evidence on care for patients with HBV. The working group relied heavily on the VA’s national guidelines for HBV screening and immunization, which are based on recommendations from the USPSTF, ACIP, CDC, and professional societies. The professional society guidelines included the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease’s Guidelines for Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B, the America College of Gastroenterology’s Practice Guidelines: Evaluation of Abnormal Liver Chemistries, the American Gastroenterological Association Institute’s Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Hepatitis B Reactivation during Immunosuppressive Drug Therapy, and CDC’s Guidelines for Screening Pregnant Women for HBV.19,22-27

The working group identified areas for HBV quality improvement that were consistent with the VA and professional guidelines, specific and measurable using VA data, clinically relevant, feasible, and achievable in a defined time period. Areas for targeted improvement will include testing for HBV among high-risk patients, increasing antiviral treatment and HCC surveillance of veterans with HBV-related cirrhosis, decreasing progression of chronic HBV to cirrhosis, and expanding prevention measures, such as immunization among those at high risk for HBV and prevention of HBV reactivation.

At a national level, development of specific and measurable quality of care indicators for HBV will aid in assessing gaps in care and developing strategies to address these gaps. A broader discussion of care for patients with HBV quality with front-line health care providers (HCPs) will be paired with increased education and providing clinical support tools for those HCPs and facilities without access to specialty GI services.

Clinical pharmacists will be critical targets for the dissemination of guidance for HBV care paired with clinical informatics support tools and clinical educational opportunities. As of 2015, there were about 7,700 clinical pharmacists in the VHA and 3,200 had a scope of practice that included prescribing authority. As a result, 20% of HCV prescriptions in the VA in fiscal year 2015

Identification and Monitoring

The HBV working group and the VA Viral Hepatitis Technical Advisory Group are working with field HCPs to develop several informatics tools to promote HBV case identification and quality monitoring. These groups identified several barriers to HBV case identification and monitoring. The following informatics tools are either available or in development to reduce these barriers:

- A local clinical case registry of patients with HBV infection based on ICD codes, which allows users to create custom reports to identify, monitor, and track care;

- Because of the risk of HBV reactivation in patients with chronic HBV infection who receive anti-CD20 agents, such as rituximab, a medication order check to improve HBV screening among veterans receiving anti-CD20 medication;

- Validated patient reports based on laboratory diagnosis of HBV, drawn from all results across the VHA since 1999, made available to all facilities;

- Interactive reports summarizing quality of care for patients with HBV infection, based on facility-level indicators in development by the national HBV working group, will be distributed and enable geographic comparison;

- An HBV immunization clinical reminder that will prompt frontline HCPs to test and vaccinate; and

- An HBV clinical dashboard that will enable HCPs and facilities to identify all their HBV-positive veterans and track their care and outcomes over time.

Evaluating VA Care for Patients with HBV

As indicators of quality of HBV care are refined for VA patients and the health care delivery system, guidance will be made broadly available to frontline HCPs and administrators. The HBV quality of care recommendations will be paired with a suite of clinical informatics tools and virtual educational trainings to ensure that VA HCPs and facilities can streamline care for patients with HBV infection as much as possible. Quality improvement will be measured nationally each year, and strategies to address persistent variability and gaps in care will be developed in collaboration with the VA SME’s, facilities, and HCPs.

Conclusion

Hepatitis B virus is at least as prevalent among veterans who are cared for at VA facilities as it is in the US civilian population. Although care for patients with HBV infection in the VA is similar to care for patients with HBV infection in the community, the VA recognizes areas for improved HBV prevention, testing, care, and treatment. The VA has begun a continuous quality improvement strategic plan to enhance the level of care for patients with HBV infection in VA care. Centralized coordination and communication of VA data combined with veteran- and field-centered policies and operational planning and execution will allow clinically relevant improvements in HBV diagnosis, treatment, and prevention among veterans served by VA.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis B FAQs for health professionals: overview and statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hbv/hbvfaq .htm#overview. Updated January 11, 2018. Accessed on February 12, 2018.

2.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance for viral hepatitis—United States, 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2015surveillance/index.htm. Updated June 19, 2017. Accessed February 12, 2018.

4. Kim WR. Epidemiology of hepatitis B in the United States. Hepatology. 2009;49(suppl 5):S28-S34.

5. Harris AM, Iqbal K, Schillie S, et al. Increases in acute hepatitis B virus infections— Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia, 2006-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(3):47-50.

6. Liaw YF, Chu CM. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2009;373(9663):582-592.

7. El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1118-1127.

8. Weinbaum CM, Williams I, Mast EE, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Recommendations for identification and public health management of persons with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57(RR-8):1-20.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Achievements in public health: hepatitis B vaccination—United States, 1982-2002. MMWR. 2002;51(25):549-552, 563.

10. Grabenstein JD, Pittman PR, Greenwood JT, Engler RJ. Immunization to protect the US Armed Forces: heritage, current practice, and prospects. Epidemiol Rev. 2006;28:3-26.

11. Colvin HM, Mitchell AE, eds; Institute of Medicine. Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010.

12. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. A National Strategy for the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C: Phase Two Report. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2017.

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Providing health care for veterans. https://www.va.gov/health. Updated February 20, 2018. Accessed February 22, 2018.

14. Noska AJ, Belperio PS, Loomis TP, O’Toole TP, Backus LI. Prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C virus, and hepatitis B virus among homeless and nonhomeless United States veterans. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(2):252-258.

15. Gelberg L, Robertson MJ, Leake B, et al. Hepatitis B among homeless and other impoverished US military veterans in residential care in Los Angeles. Public Health. 2001;115(4):286-291.

16. Tabibian JH, Wirshing DA, Pierre JM, et al. Hepatitis B and C among veterans in a psychiatric ward. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53(6):1693-1698

17. US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: screening for hepatitis B virus infection in nonpregnant adolescents and adults. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/hepatitis-b-virus-infection-screening-2014. Published May 2014. Updated February 2018. Accessed February 22, 2018.

18. Backus LI, Belperio PS, Loomis TP, Han SH, Mole LA. Screening for and prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection among high-risk veterans under the care of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: a case report. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(12):926-928.

19. Serper M, Choi G, Forde KA, Kaplan DE. Care delivery and outcomes among US veterans with hepatitis B: a national cohort study. Hepatology. 2016;63(6):1774-1782.

20. Mellinger J, Fontana RJ. Quality of care metrics in chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63(6):1755-1758.

21. Roberts H, Kruszon-Moran D, Ly KN, et al. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in U.S. households: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 1988-2012. Hepatology. 2016;63(2):388-397.

22. US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Clinical Preventive Service Guidance Statements: Hepatitis B Immunization. http://vaww.prevention.va.gov/CPS/Hepatitis_B_Immunization.asp. Nonpublic document. Source not verified.

23. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Recommended immunization schedule for adults aged 19 years or older, United States, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/adult.html. Accessed February 12, 2018.

24. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of Hepatitis B Virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR. 2018;67(1):1-31.

25. Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang KM, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, Murad MH; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63(1):261-283.

26. Kwo PY, Cohen SM, Lim JK. ACG clinical guideline: evaluation of abnormal liver chemistries. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(1):18-35.

27. Reddy KR, Beavers KL, Hammond SP, Lim JK, Falck-Ytter YT; American Gastroenterological Association Institute. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(1):215-219, quiz e16-e17.

28. Ourth H, Groppi J, Morreale AP, Quicci-Roberts K. Clinical pharmacist prescribing activities in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(18):1406-1415.

Hepatitis B is a viral infection caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV), which is transmitted through percutaneous (ie, puncture through the skin) or mucosal (ie, direct contact with mucous membranes) exposure to infectious blood or body fluids. Hepatitis B virus can cause chronic infection, resulting in cirrhosis of the liver, liver cancer, liver failure, and death. Persons with chronic infection also serve as the main reservoir for continued HBV transmission.1

Individuals at highest risk for infection include those born in geographic regions with a high prevalence of HBV, those with sexual partners or household contacts with chronic HBV infection, men who have sex with men (MSM), those with HIV, and individuals who inject drugs. Pregnant women also are a population of concern given the potential for perinatal transmission.2

About 850,000 to 2.2 million people in the US (about 0.3% of the civilian US population) are chronically infected with HBV.3 The prevalence of chronic HBV is much higher (10%-19%) among Asian Americans, those of Pacific Island descent, and other immigrant populations from highly endemic countries.4 In the US, HBV is responsible for 2,000 to 4,000 preventable deaths annually, primarily from cirrhosis, liver cancer, and hepatic failure.4 In the civilian US population, reported cases of acute HBV decreased 0.3% from 2011 to 2012, increased 5.4% in 2013 with an 8.5% decrease in 2014, and a 20.7% increase in 2015.4 Injection drug use is likely driving the most recent increase.5

Not all individuals exposed to HBV will develop chronic infection, and the risk of chronic HBV infection depends on an individual’s age at the time of exposure. For example, about 95% of infants exposed to HBV perinatally will develop a chronic infection compared with 5% of exposed adults.6 Of those with chronic HBV, a small proportion will develop cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with increasing risk as viral DNA concentrations increase. Additional risk factors for cirrhosis include being older, male, having a persistently elevated alanine transaminase, viral superinfections, HBV reversion/reactivation, genotype, and various markers of disease severity (HCC).6 Of note, chronic HBV infection may cause HCC even in the absence of cirrhosis.7 In addition, immunosuppression (eg, from cancer chemotherapy) may allow HBV reactivation, which may result in fulminant hepatic failure. In the Veterans Health Affairs (VHA) health care system, about 17% of those with known chronic HBV also carry a diagnosis of cirrhosis.

Vaccination is the mainstay of efforts to prevent HBV infection. The first commercially available HBV vaccine was approved by the FDA in 1981, with subsequent FDA approval in 1986 of a vaccine manufactured using recombinant DNA technology.8 In 1991, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended universal childhood vaccination for HBV, with subsequent recommendations for vaccination of adolescents and adults in high-risk groups in 1995, and in 1999 all remaining unvaccinated children aged ≤ 19 years.9 Military policy has been to provide hepatitis B immunization to personnel assigned to the Korean peninsula since 1986 and to all recruits since 2001.10

Following publication of an Institute of Medicine/National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) report, in 2011 the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) released the first National Viral Hepatitis Action Plan.11 The current HHS Action Plan, along with the NASEM National Strategy for the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C: Phase Two Report, commissioned by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), outlines a national strategy to prevent new viral hepatitis infections; reduce deaths and improve the health of people living with viral hepatitis; reduce viral hepatitis health disparities; and coordinate, monitor, and report on implementation of viral hepatitis activities.12 The VA is a critical partner in this federal collaborative effort to achieve excellence in viral hepatitis care.

In August 2016, the HIV, Hepatitis, and Related Conditions Programs in the VA Office of Specialty Care Services convened a National Hepatitis B Working Group consisting of VA subject matter experts (SMEs) and representatives from the VA Central Office stakeholder program offices, with a charge of developing a strategic plan to ensure excellence in HBV prevention, care, and management across the VHA. The task included addressing supportive processes and barriers at each level of the organization through a public health framework and using a population health management approach.

The VA National Strategic Plan for Excellence in HBV Care was focused on the following overarching aims:

- Characterizing the current state of care for veterans with HBV in VA care;

- Developing and disseminating clinical guidance on high-quality care for patients with HBV;

- Developing population data and informatics tools to streamline the identification and monitoring of patients with chronic HBV; and

- Evaluating VHA care for patients with HBV over time.

Care for Veterans With HBV at the VA

The VA health care system is America’s largest integrated health care system, providing care at 1,243 health care facilities, including 170 medical centers and 1,063 outpatient sites of care serving 9 million enrolled veterans each year.13 As of January 2018, there were 10,743 individuals with serologic evidence for chronic HBV infection in VA care, based on a definition of 2 or more detectable surface antigen (sAg) or hepatitis B DNA tests recorded at least 6 months apart.1 About 2,000 additional VA patients have a history of a single positive sAg test. These patients have unclear HBV status and require a second sAg test to determine whether they have a chronic infection.

The prevalence of HBV infection among veterans in VA care is slightly higher than that in the US civilian population at 0.4%.14 Studies of selected subpopulations of veterans have found high seropositivity of prior or chronic HBV infection among homeless veterans and veterans admitted to a psychiatric hospital.15,16 The data from 2015 suggest that homeless veterans have a chronic HBV infection rate of 1.0%.14 Of those with known chronic HBV infection, the plurality are white (40.4%) or African American (40.2%), male (92.4%), with a mean age of 59.9 (SD 12.0) years. According to National HIV, Hepatitis and Related Conditions Data and Analysis Group personal correspondence, the geographic territories with the largest chronic HBV caseload include the Southeast, Gulf Coast, and West Coast. As of January 2018, 1,210 veterans in care have HBV-related cirrhosis.

HBV Screening in VA

The current VA HBV screening guidelines follow those of the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).17 HBV screening is recommended for unvaccinated individuals in high-risk groups, such as patients with HIV or hepatitis C virus (HCV), those on hemodialysis, those with elevated alanine transaminase/aspartate transaminase of unknown etiology, those on immunosuppressive therapy, injection drug users, the MSM population, people with household contact with an HBV-infected person, people born to an HBV-infected mother, those with risk factors for HBV exposure prior to vaccination, pregnant women, and people born in highly endemic areas regardless of vaccination status.2 The VHA recommends against standardized risk assessment and laboratory screening for HBV infection in the asymptomatic general patient population. However, if risk factors become known during the course of providing usual clinical care, then laboratory screening should be considered.2

Of the 6.1 million VHA users

HBV Care and VA Antiviral Treatment

In a study of an HBV care cascade, Serper and colleagues reviewed a cohort of veterans in the VA with HBV. About 50% of the patients with known chronic HBV in the VA system from 1999 to 2013 had received infectious diseases or gastroenterology/hepatology specialty care in the previous 2 years.19 Follow-up data from the National HIV, Hepatitis and Related Conditions Data and Analysis Group indicated that this remains the case: 52.3% of patients with documented chronic HBV had received specialty care from VA sources in the prior 2 years. Serper and colleagues also reported that among veterans in VHA care with chronic HBV infection and cirrhosis from 1999 to 2013, annual imaging was < 50%, and initiation of antiviral treatment was only 39%. Antiviral therapy and liver imaging were both independently associated with lower mortality for patients with HBV and cirrhosis.19

A review of studies that evaluated the delivery of care for patients with HBV in U.S. civilian populations, including retrospective reviews of private payer claims databases and chart reviews, the Kaiser Permanente claims database, and community gastrointestinal (GI) practice chart reviews, revealed similar practice patterns with those in the VA.20 Across the US, rates of antiviral therapy and HCC surveillance for those with HBV cirrhosis were low, ranging from 14% to 50% and 19% to 60%, respectively. Several of these studies also found that being seen by an HBV specialist was associated with improved care.20

Antiviral treatment of individuals with cirrhosis and chronic HBV infection can reduce the risk of progression to decompensated cirrhosis and liver cancer. Among current VA patients with HBV cirrhosis, 62.4% received at least 1 month of HBV antiviral medication in the prior year. Additionally, biannual liver imaging is recommended in this population to screen for the development of HCC. According to National HIV, Hepatitis and Related Conditions Data and Analysis Group personal correspondence, nationally, 51.2% of individuals with HBV cirrhosis had received at least one instance of liver imaging within the past 6 months, and 71.2% received imaging within the past 12 months.

Prevention of HBV Infection and Sequelae

Vaccination rates in the US vary by age group, with higher immunization rates among those born after 1991 than the rates of those born earlier. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 1988 to 2012 reported 33% immunity among veterans aged < 50 years and 6% among those aged ≥ 50 years.21 In addition to individuals who received childhood vaccination in the 1990s, all new military recruits assigned to the Korean Peninsula were vaccinated for HBV as of 1986, and those joining the military after 2002 received mandatory vaccination.

The VA follows the ACIP/CDC hepatitis B immunization guidelines.22-24 The VA currently recommends HBV immunization among previously unvaccinated adults at increased risk of contracting HBV infection and for any other adult who is seeking protection from HBV infection. The VA also offers general recommendations for prevention of transmission between veterans with known chronic HBV to their household, sexual, or drug-using partners. Transmission prevention guidelines also provide recommendations for vaccination of pregnant women with HBV risk factors and women at risk for HBV infection during pregnancy.22

HBV Care Guidance

One of the core tasks of the VA National Hepatitis B Working Group, given its broad, multidisciplinary expertise in HBV, was developing general clinical guidelines for the provision of high-quality care for patients with HBV. The group reviewed current literature and scientific evidence on care for patients with HBV. The working group relied heavily on the VA’s national guidelines for HBV screening and immunization, which are based on recommendations from the USPSTF, ACIP, CDC, and professional societies. The professional society guidelines included the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease’s Guidelines for Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B, the America College of Gastroenterology’s Practice Guidelines: Evaluation of Abnormal Liver Chemistries, the American Gastroenterological Association Institute’s Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Hepatitis B Reactivation during Immunosuppressive Drug Therapy, and CDC’s Guidelines for Screening Pregnant Women for HBV.19,22-27

The working group identified areas for HBV quality improvement that were consistent with the VA and professional guidelines, specific and measurable using VA data, clinically relevant, feasible, and achievable in a defined time period. Areas for targeted improvement will include testing for HBV among high-risk patients, increasing antiviral treatment and HCC surveillance of veterans with HBV-related cirrhosis, decreasing progression of chronic HBV to cirrhosis, and expanding prevention measures, such as immunization among those at high risk for HBV and prevention of HBV reactivation.

At a national level, development of specific and measurable quality of care indicators for HBV will aid in assessing gaps in care and developing strategies to address these gaps. A broader discussion of care for patients with HBV quality with front-line health care providers (HCPs) will be paired with increased education and providing clinical support tools for those HCPs and facilities without access to specialty GI services.

Clinical pharmacists will be critical targets for the dissemination of guidance for HBV care paired with clinical informatics support tools and clinical educational opportunities. As of 2015, there were about 7,700 clinical pharmacists in the VHA and 3,200 had a scope of practice that included prescribing authority. As a result, 20% of HCV prescriptions in the VA in fiscal year 2015

Identification and Monitoring

The HBV working group and the VA Viral Hepatitis Technical Advisory Group are working with field HCPs to develop several informatics tools to promote HBV case identification and quality monitoring. These groups identified several barriers to HBV case identification and monitoring. The following informatics tools are either available or in development to reduce these barriers:

- A local clinical case registry of patients with HBV infection based on ICD codes, which allows users to create custom reports to identify, monitor, and track care;

- Because of the risk of HBV reactivation in patients with chronic HBV infection who receive anti-CD20 agents, such as rituximab, a medication order check to improve HBV screening among veterans receiving anti-CD20 medication;

- Validated patient reports based on laboratory diagnosis of HBV, drawn from all results across the VHA since 1999, made available to all facilities;

- Interactive reports summarizing quality of care for patients with HBV infection, based on facility-level indicators in development by the national HBV working group, will be distributed and enable geographic comparison;

- An HBV immunization clinical reminder that will prompt frontline HCPs to test and vaccinate; and

- An HBV clinical dashboard that will enable HCPs and facilities to identify all their HBV-positive veterans and track their care and outcomes over time.

Evaluating VA Care for Patients with HBV

As indicators of quality of HBV care are refined for VA patients and the health care delivery system, guidance will be made broadly available to frontline HCPs and administrators. The HBV quality of care recommendations will be paired with a suite of clinical informatics tools and virtual educational trainings to ensure that VA HCPs and facilities can streamline care for patients with HBV infection as much as possible. Quality improvement will be measured nationally each year, and strategies to address persistent variability and gaps in care will be developed in collaboration with the VA SME’s, facilities, and HCPs.

Conclusion

Hepatitis B virus is at least as prevalent among veterans who are cared for at VA facilities as it is in the US civilian population. Although care for patients with HBV infection in the VA is similar to care for patients with HBV infection in the community, the VA recognizes areas for improved HBV prevention, testing, care, and treatment. The VA has begun a continuous quality improvement strategic plan to enhance the level of care for patients with HBV infection in VA care. Centralized coordination and communication of VA data combined with veteran- and field-centered policies and operational planning and execution will allow clinically relevant improvements in HBV diagnosis, treatment, and prevention among veterans served by VA.

Click here to read the digital edition.

Hepatitis B is a viral infection caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV), which is transmitted through percutaneous (ie, puncture through the skin) or mucosal (ie, direct contact with mucous membranes) exposure to infectious blood or body fluids. Hepatitis B virus can cause chronic infection, resulting in cirrhosis of the liver, liver cancer, liver failure, and death. Persons with chronic infection also serve as the main reservoir for continued HBV transmission.1

Individuals at highest risk for infection include those born in geographic regions with a high prevalence of HBV, those with sexual partners or household contacts with chronic HBV infection, men who have sex with men (MSM), those with HIV, and individuals who inject drugs. Pregnant women also are a population of concern given the potential for perinatal transmission.2

About 850,000 to 2.2 million people in the US (about 0.3% of the civilian US population) are chronically infected with HBV.3 The prevalence of chronic HBV is much higher (10%-19%) among Asian Americans, those of Pacific Island descent, and other immigrant populations from highly endemic countries.4 In the US, HBV is responsible for 2,000 to 4,000 preventable deaths annually, primarily from cirrhosis, liver cancer, and hepatic failure.4 In the civilian US population, reported cases of acute HBV decreased 0.3% from 2011 to 2012, increased 5.4% in 2013 with an 8.5% decrease in 2014, and a 20.7% increase in 2015.4 Injection drug use is likely driving the most recent increase.5

Not all individuals exposed to HBV will develop chronic infection, and the risk of chronic HBV infection depends on an individual’s age at the time of exposure. For example, about 95% of infants exposed to HBV perinatally will develop a chronic infection compared with 5% of exposed adults.6 Of those with chronic HBV, a small proportion will develop cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with increasing risk as viral DNA concentrations increase. Additional risk factors for cirrhosis include being older, male, having a persistently elevated alanine transaminase, viral superinfections, HBV reversion/reactivation, genotype, and various markers of disease severity (HCC).6 Of note, chronic HBV infection may cause HCC even in the absence of cirrhosis.7 In addition, immunosuppression (eg, from cancer chemotherapy) may allow HBV reactivation, which may result in fulminant hepatic failure. In the Veterans Health Affairs (VHA) health care system, about 17% of those with known chronic HBV also carry a diagnosis of cirrhosis.

Vaccination is the mainstay of efforts to prevent HBV infection. The first commercially available HBV vaccine was approved by the FDA in 1981, with subsequent FDA approval in 1986 of a vaccine manufactured using recombinant DNA technology.8 In 1991, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended universal childhood vaccination for HBV, with subsequent recommendations for vaccination of adolescents and adults in high-risk groups in 1995, and in 1999 all remaining unvaccinated children aged ≤ 19 years.9 Military policy has been to provide hepatitis B immunization to personnel assigned to the Korean peninsula since 1986 and to all recruits since 2001.10

Following publication of an Institute of Medicine/National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) report, in 2011 the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) released the first National Viral Hepatitis Action Plan.11 The current HHS Action Plan, along with the NASEM National Strategy for the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C: Phase Two Report, commissioned by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), outlines a national strategy to prevent new viral hepatitis infections; reduce deaths and improve the health of people living with viral hepatitis; reduce viral hepatitis health disparities; and coordinate, monitor, and report on implementation of viral hepatitis activities.12 The VA is a critical partner in this federal collaborative effort to achieve excellence in viral hepatitis care.

In August 2016, the HIV, Hepatitis, and Related Conditions Programs in the VA Office of Specialty Care Services convened a National Hepatitis B Working Group consisting of VA subject matter experts (SMEs) and representatives from the VA Central Office stakeholder program offices, with a charge of developing a strategic plan to ensure excellence in HBV prevention, care, and management across the VHA. The task included addressing supportive processes and barriers at each level of the organization through a public health framework and using a population health management approach.

The VA National Strategic Plan for Excellence in HBV Care was focused on the following overarching aims:

- Characterizing the current state of care for veterans with HBV in VA care;

- Developing and disseminating clinical guidance on high-quality care for patients with HBV;

- Developing population data and informatics tools to streamline the identification and monitoring of patients with chronic HBV; and

- Evaluating VHA care for patients with HBV over time.

Care for Veterans With HBV at the VA

The VA health care system is America’s largest integrated health care system, providing care at 1,243 health care facilities, including 170 medical centers and 1,063 outpatient sites of care serving 9 million enrolled veterans each year.13 As of January 2018, there were 10,743 individuals with serologic evidence for chronic HBV infection in VA care, based on a definition of 2 or more detectable surface antigen (sAg) or hepatitis B DNA tests recorded at least 6 months apart.1 About 2,000 additional VA patients have a history of a single positive sAg test. These patients have unclear HBV status and require a second sAg test to determine whether they have a chronic infection.

The prevalence of HBV infection among veterans in VA care is slightly higher than that in the US civilian population at 0.4%.14 Studies of selected subpopulations of veterans have found high seropositivity of prior or chronic HBV infection among homeless veterans and veterans admitted to a psychiatric hospital.15,16 The data from 2015 suggest that homeless veterans have a chronic HBV infection rate of 1.0%.14 Of those with known chronic HBV infection, the plurality are white (40.4%) or African American (40.2%), male (92.4%), with a mean age of 59.9 (SD 12.0) years. According to National HIV, Hepatitis and Related Conditions Data and Analysis Group personal correspondence, the geographic territories with the largest chronic HBV caseload include the Southeast, Gulf Coast, and West Coast. As of January 2018, 1,210 veterans in care have HBV-related cirrhosis.

HBV Screening in VA

The current VA HBV screening guidelines follow those of the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).17 HBV screening is recommended for unvaccinated individuals in high-risk groups, such as patients with HIV or hepatitis C virus (HCV), those on hemodialysis, those with elevated alanine transaminase/aspartate transaminase of unknown etiology, those on immunosuppressive therapy, injection drug users, the MSM population, people with household contact with an HBV-infected person, people born to an HBV-infected mother, those with risk factors for HBV exposure prior to vaccination, pregnant women, and people born in highly endemic areas regardless of vaccination status.2 The VHA recommends against standardized risk assessment and laboratory screening for HBV infection in the asymptomatic general patient population. However, if risk factors become known during the course of providing usual clinical care, then laboratory screening should be considered.2

Of the 6.1 million VHA users

HBV Care and VA Antiviral Treatment

In a study of an HBV care cascade, Serper and colleagues reviewed a cohort of veterans in the VA with HBV. About 50% of the patients with known chronic HBV in the VA system from 1999 to 2013 had received infectious diseases or gastroenterology/hepatology specialty care in the previous 2 years.19 Follow-up data from the National HIV, Hepatitis and Related Conditions Data and Analysis Group indicated that this remains the case: 52.3% of patients with documented chronic HBV had received specialty care from VA sources in the prior 2 years. Serper and colleagues also reported that among veterans in VHA care with chronic HBV infection and cirrhosis from 1999 to 2013, annual imaging was < 50%, and initiation of antiviral treatment was only 39%. Antiviral therapy and liver imaging were both independently associated with lower mortality for patients with HBV and cirrhosis.19

A review of studies that evaluated the delivery of care for patients with HBV in U.S. civilian populations, including retrospective reviews of private payer claims databases and chart reviews, the Kaiser Permanente claims database, and community gastrointestinal (GI) practice chart reviews, revealed similar practice patterns with those in the VA.20 Across the US, rates of antiviral therapy and HCC surveillance for those with HBV cirrhosis were low, ranging from 14% to 50% and 19% to 60%, respectively. Several of these studies also found that being seen by an HBV specialist was associated with improved care.20

Antiviral treatment of individuals with cirrhosis and chronic HBV infection can reduce the risk of progression to decompensated cirrhosis and liver cancer. Among current VA patients with HBV cirrhosis, 62.4% received at least 1 month of HBV antiviral medication in the prior year. Additionally, biannual liver imaging is recommended in this population to screen for the development of HCC. According to National HIV, Hepatitis and Related Conditions Data and Analysis Group personal correspondence, nationally, 51.2% of individuals with HBV cirrhosis had received at least one instance of liver imaging within the past 6 months, and 71.2% received imaging within the past 12 months.

Prevention of HBV Infection and Sequelae

Vaccination rates in the US vary by age group, with higher immunization rates among those born after 1991 than the rates of those born earlier. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 1988 to 2012 reported 33% immunity among veterans aged < 50 years and 6% among those aged ≥ 50 years.21 In addition to individuals who received childhood vaccination in the 1990s, all new military recruits assigned to the Korean Peninsula were vaccinated for HBV as of 1986, and those joining the military after 2002 received mandatory vaccination.

The VA follows the ACIP/CDC hepatitis B immunization guidelines.22-24 The VA currently recommends HBV immunization among previously unvaccinated adults at increased risk of contracting HBV infection and for any other adult who is seeking protection from HBV infection. The VA also offers general recommendations for prevention of transmission between veterans with known chronic HBV to their household, sexual, or drug-using partners. Transmission prevention guidelines also provide recommendations for vaccination of pregnant women with HBV risk factors and women at risk for HBV infection during pregnancy.22

HBV Care Guidance

One of the core tasks of the VA National Hepatitis B Working Group, given its broad, multidisciplinary expertise in HBV, was developing general clinical guidelines for the provision of high-quality care for patients with HBV. The group reviewed current literature and scientific evidence on care for patients with HBV. The working group relied heavily on the VA’s national guidelines for HBV screening and immunization, which are based on recommendations from the USPSTF, ACIP, CDC, and professional societies. The professional society guidelines included the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease’s Guidelines for Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B, the America College of Gastroenterology’s Practice Guidelines: Evaluation of Abnormal Liver Chemistries, the American Gastroenterological Association Institute’s Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Hepatitis B Reactivation during Immunosuppressive Drug Therapy, and CDC’s Guidelines for Screening Pregnant Women for HBV.19,22-27

The working group identified areas for HBV quality improvement that were consistent with the VA and professional guidelines, specific and measurable using VA data, clinically relevant, feasible, and achievable in a defined time period. Areas for targeted improvement will include testing for HBV among high-risk patients, increasing antiviral treatment and HCC surveillance of veterans with HBV-related cirrhosis, decreasing progression of chronic HBV to cirrhosis, and expanding prevention measures, such as immunization among those at high risk for HBV and prevention of HBV reactivation.

At a national level, development of specific and measurable quality of care indicators for HBV will aid in assessing gaps in care and developing strategies to address these gaps. A broader discussion of care for patients with HBV quality with front-line health care providers (HCPs) will be paired with increased education and providing clinical support tools for those HCPs and facilities without access to specialty GI services.

Clinical pharmacists will be critical targets for the dissemination of guidance for HBV care paired with clinical informatics support tools and clinical educational opportunities. As of 2015, there were about 7,700 clinical pharmacists in the VHA and 3,200 had a scope of practice that included prescribing authority. As a result, 20% of HCV prescriptions in the VA in fiscal year 2015

Identification and Monitoring

The HBV working group and the VA Viral Hepatitis Technical Advisory Group are working with field HCPs to develop several informatics tools to promote HBV case identification and quality monitoring. These groups identified several barriers to HBV case identification and monitoring. The following informatics tools are either available or in development to reduce these barriers:

- A local clinical case registry of patients with HBV infection based on ICD codes, which allows users to create custom reports to identify, monitor, and track care;

- Because of the risk of HBV reactivation in patients with chronic HBV infection who receive anti-CD20 agents, such as rituximab, a medication order check to improve HBV screening among veterans receiving anti-CD20 medication;

- Validated patient reports based on laboratory diagnosis of HBV, drawn from all results across the VHA since 1999, made available to all facilities;

- Interactive reports summarizing quality of care for patients with HBV infection, based on facility-level indicators in development by the national HBV working group, will be distributed and enable geographic comparison;

- An HBV immunization clinical reminder that will prompt frontline HCPs to test and vaccinate; and

- An HBV clinical dashboard that will enable HCPs and facilities to identify all their HBV-positive veterans and track their care and outcomes over time.

Evaluating VA Care for Patients with HBV

As indicators of quality of HBV care are refined for VA patients and the health care delivery system, guidance will be made broadly available to frontline HCPs and administrators. The HBV quality of care recommendations will be paired with a suite of clinical informatics tools and virtual educational trainings to ensure that VA HCPs and facilities can streamline care for patients with HBV infection as much as possible. Quality improvement will be measured nationally each year, and strategies to address persistent variability and gaps in care will be developed in collaboration with the VA SME’s, facilities, and HCPs.

Conclusion

Hepatitis B virus is at least as prevalent among veterans who are cared for at VA facilities as it is in the US civilian population. Although care for patients with HBV infection in the VA is similar to care for patients with HBV infection in the community, the VA recognizes areas for improved HBV prevention, testing, care, and treatment. The VA has begun a continuous quality improvement strategic plan to enhance the level of care for patients with HBV infection in VA care. Centralized coordination and communication of VA data combined with veteran- and field-centered policies and operational planning and execution will allow clinically relevant improvements in HBV diagnosis, treatment, and prevention among veterans served by VA.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis B FAQs for health professionals: overview and statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hbv/hbvfaq .htm#overview. Updated January 11, 2018. Accessed on February 12, 2018.

2.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance for viral hepatitis—United States, 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2015surveillance/index.htm. Updated June 19, 2017. Accessed February 12, 2018.

4. Kim WR. Epidemiology of hepatitis B in the United States. Hepatology. 2009;49(suppl 5):S28-S34.

5. Harris AM, Iqbal K, Schillie S, et al. Increases in acute hepatitis B virus infections— Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia, 2006-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(3):47-50.

6. Liaw YF, Chu CM. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2009;373(9663):582-592.

7. El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1118-1127.

8. Weinbaum CM, Williams I, Mast EE, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Recommendations for identification and public health management of persons with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57(RR-8):1-20.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Achievements in public health: hepatitis B vaccination—United States, 1982-2002. MMWR. 2002;51(25):549-552, 563.

10. Grabenstein JD, Pittman PR, Greenwood JT, Engler RJ. Immunization to protect the US Armed Forces: heritage, current practice, and prospects. Epidemiol Rev. 2006;28:3-26.

11. Colvin HM, Mitchell AE, eds; Institute of Medicine. Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010.

12. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. A National Strategy for the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C: Phase Two Report. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2017.

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Providing health care for veterans. https://www.va.gov/health. Updated February 20, 2018. Accessed February 22, 2018.

14. Noska AJ, Belperio PS, Loomis TP, O’Toole TP, Backus LI. Prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C virus, and hepatitis B virus among homeless and nonhomeless United States veterans. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(2):252-258.

15. Gelberg L, Robertson MJ, Leake B, et al. Hepatitis B among homeless and other impoverished US military veterans in residential care in Los Angeles. Public Health. 2001;115(4):286-291.

16. Tabibian JH, Wirshing DA, Pierre JM, et al. Hepatitis B and C among veterans in a psychiatric ward. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53(6):1693-1698

17. US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: screening for hepatitis B virus infection in nonpregnant adolescents and adults. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/hepatitis-b-virus-infection-screening-2014. Published May 2014. Updated February 2018. Accessed February 22, 2018.

18. Backus LI, Belperio PS, Loomis TP, Han SH, Mole LA. Screening for and prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection among high-risk veterans under the care of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: a case report. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(12):926-928.

19. Serper M, Choi G, Forde KA, Kaplan DE. Care delivery and outcomes among US veterans with hepatitis B: a national cohort study. Hepatology. 2016;63(6):1774-1782.

20. Mellinger J, Fontana RJ. Quality of care metrics in chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63(6):1755-1758.

21. Roberts H, Kruszon-Moran D, Ly KN, et al. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in U.S. households: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 1988-2012. Hepatology. 2016;63(2):388-397.

22. US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Clinical Preventive Service Guidance Statements: Hepatitis B Immunization. http://vaww.prevention.va.gov/CPS/Hepatitis_B_Immunization.asp. Nonpublic document. Source not verified.

23. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Recommended immunization schedule for adults aged 19 years or older, United States, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/adult.html. Accessed February 12, 2018.

24. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of Hepatitis B Virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR. 2018;67(1):1-31.

25. Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang KM, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, Murad MH; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63(1):261-283.

26. Kwo PY, Cohen SM, Lim JK. ACG clinical guideline: evaluation of abnormal liver chemistries. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(1):18-35.

27. Reddy KR, Beavers KL, Hammond SP, Lim JK, Falck-Ytter YT; American Gastroenterological Association Institute. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(1):215-219, quiz e16-e17.

28. Ourth H, Groppi J, Morreale AP, Quicci-Roberts K. Clinical pharmacist prescribing activities in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(18):1406-1415.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis B FAQs for health professionals: overview and statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hbv/hbvfaq .htm#overview. Updated January 11, 2018. Accessed on February 12, 2018.

2.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance for viral hepatitis—United States, 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2015surveillance/index.htm. Updated June 19, 2017. Accessed February 12, 2018.

4. Kim WR. Epidemiology of hepatitis B in the United States. Hepatology. 2009;49(suppl 5):S28-S34.

5. Harris AM, Iqbal K, Schillie S, et al. Increases in acute hepatitis B virus infections— Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia, 2006-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(3):47-50.

6. Liaw YF, Chu CM. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2009;373(9663):582-592.

7. El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1118-1127.

8. Weinbaum CM, Williams I, Mast EE, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Recommendations for identification and public health management of persons with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57(RR-8):1-20.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Achievements in public health: hepatitis B vaccination—United States, 1982-2002. MMWR. 2002;51(25):549-552, 563.

10. Grabenstein JD, Pittman PR, Greenwood JT, Engler RJ. Immunization to protect the US Armed Forces: heritage, current practice, and prospects. Epidemiol Rev. 2006;28:3-26.

11. Colvin HM, Mitchell AE, eds; Institute of Medicine. Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010.

12. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. A National Strategy for the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C: Phase Two Report. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2017.

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Providing health care for veterans. https://www.va.gov/health. Updated February 20, 2018. Accessed February 22, 2018.

14. Noska AJ, Belperio PS, Loomis TP, O’Toole TP, Backus LI. Prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C virus, and hepatitis B virus among homeless and nonhomeless United States veterans. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(2):252-258.

15. Gelberg L, Robertson MJ, Leake B, et al. Hepatitis B among homeless and other impoverished US military veterans in residential care in Los Angeles. Public Health. 2001;115(4):286-291.

16. Tabibian JH, Wirshing DA, Pierre JM, et al. Hepatitis B and C among veterans in a psychiatric ward. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53(6):1693-1698

17. US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: screening for hepatitis B virus infection in nonpregnant adolescents and adults. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/hepatitis-b-virus-infection-screening-2014. Published May 2014. Updated February 2018. Accessed February 22, 2018.

18. Backus LI, Belperio PS, Loomis TP, Han SH, Mole LA. Screening for and prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection among high-risk veterans under the care of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: a case report. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(12):926-928.

19. Serper M, Choi G, Forde KA, Kaplan DE. Care delivery and outcomes among US veterans with hepatitis B: a national cohort study. Hepatology. 2016;63(6):1774-1782.

20. Mellinger J, Fontana RJ. Quality of care metrics in chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63(6):1755-1758.

21. Roberts H, Kruszon-Moran D, Ly KN, et al. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in U.S. households: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 1988-2012. Hepatology. 2016;63(2):388-397.

22. US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Clinical Preventive Service Guidance Statements: Hepatitis B Immunization. http://vaww.prevention.va.gov/CPS/Hepatitis_B_Immunization.asp. Nonpublic document. Source not verified.

23. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Recommended immunization schedule for adults aged 19 years or older, United States, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/adult.html. Accessed February 12, 2018.

24. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of Hepatitis B Virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR. 2018;67(1):1-31.

25. Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang KM, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, Murad MH; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63(1):261-283.

26. Kwo PY, Cohen SM, Lim JK. ACG clinical guideline: evaluation of abnormal liver chemistries. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(1):18-35.

27. Reddy KR, Beavers KL, Hammond SP, Lim JK, Falck-Ytter YT; American Gastroenterological Association Institute. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(1):215-219, quiz e16-e17.

28. Ourth H, Groppi J, Morreale AP, Quicci-Roberts K. Clinical pharmacist prescribing activities in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(18):1406-1415.

Screening and Treating Hepatitis C in the VA: Achieving Excellence Using Lean and System Redesign

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a major public health problem in the US. Following the 2010 report of the Institute of Medicine/National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) on hepatitis and liver cancer, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) released the first National Viral Hepatitis Action Plan in 2011 with subsequent action plan updates for 2014-2016 and 2017-2020.1-3 A NASEM phase 2 report and the 2017-2020 HHS action plan outline a national strategy to prevent new viral hepatitis infections; reduce deaths and improve the health of people living with viral hepatitis; reduce viral hepatitis health disparities; and coordinate, monitor, and report on implementation of viral hepatitis activities.3,4 The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the single largest HCV care provider in the US with about 165,000 veterans in care diagnosed with HCV in the beginning of 2014 and is a national leader in the testing and treatment of HCV.5,6

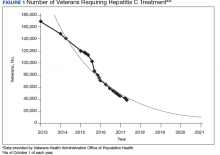

The VA’s recommendations for screening for HCV infection are in alignment with the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations to test all veterans born between 1945 and 1965 and anyone with risk factors such as injection drug use.7-9 As of January 1, 2018, the VA had screened more than 80% of veterans in care within this highest risk birth cohort. As of January 1, 2018, more than 100,000 veterans in VA care have initiated treatment for HCV with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) (Figure 1).

Several critical factors contributed to the VA success with HCV testing and treatment, including congressional appropriation of funding from fiscal year (FY) 2016 through FY 2018, unrestricted access to interferon-free DAA HCV treatments, and dedicated resources from the VA National Viral Hepatitis Program within the HIV, Hepatitis, and Related Conditions Programs (HHRC) in the Office of Specialty Care Services.5 In 2014, HHRC created and supported the Hepatitis Innovation Team (HIT) Collaborative, a VA process improvement initiative enabling

Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) -based, multidisciplinary teams to increase veterans’ access to HCV testing and treatment.

As the VA makes consistent progress toward eliminating HCV in veterans in VA care, it has become clear that achieving a cure is only a starting point in improving HCV care. Many patients with HCV infection also have advanced liver disease (ALD), or cirrhosis, which is a condition of permanent liver fibrosis that remains after the patient has been cured of HCV infection. In addition to hepatitis C, ALD also can be caused by excessive alcohol use, hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases, and several other inherited diseases. Advanced liver disease affects more than 80,000 veterans in VA care, and the HIT infrastructure provides an excellent framework to better understand and address facility-level and systemwide challenges in diagnosing, caring for, and treating veterans with ALD across the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system.

This report will describe the elements that contributed to the success of the HIT Collaborative in redesigning care for patients affected by HCV in the VA and how these elements can be applied to improve the system of care for VHA ALD care.

Hepatitis Innovation Teams Collaborative Leadership

After the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved new DAA medications to treat HCV, the VA recognized the need to mobilize the health care system quickly and allocate resources for these new, minimally toxic, and highly effective medications. Early in 2014, HHRC established the National Hepatitis C Resource Center (NHCRC), a successor program to the 4 regional hepatitis C resource centers that had addressed HCV care across the system.10 The NHCRC was charged with developing an operational strategy for VA to respond rapidly to the availability of DAAs. In collaboration with representatives from the Office of Strategic Integration | Veterans Engineering Resource Center (OSI|VERC), the NHCRC formed the HIT Collaborative Leadership Team (CLT).

The HIT CLT is responsible for executing the HIT Collaborative and uses a Lean process improvement framework focused on eliminating waste and maximizing value. Members of the CLT with expertise in facilitation, Lean process improvement, leadership, clinical knowledge, and population health management act as coaches for the VISN HITs. The CLT works to build and support the VISN HITs, identify opportunities for individual teams to improve and assist in finding the right local mix of “players” to be successful. The HIT CLT ensures all teams are functioning and working toward achieving their goals. The CLT obtains data from VA national databases, which are provided to the VISN HITs to inform and encourage continuous improvement of their strategies. Annual VA-wide aspirational goals are developed and disseminated to encourage a unified mission.

Catchment areas for each VISN include between 6 and 10 medical centers as well as outpatient and ambulatory care centers. Multidisciplinary HITs are composed of physicians, nurses, pharmacists, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, social workers, mental health and substance use providers, peer support specialists, administrators, information technology experts, and systems redesign professionals from medical centers within each VISN. Teams develop strong relationships across medical centers, implement context-specific strategies applicable to rural

and urban centers, and share expertise. In addition to intra-VISN process improvement, HITs collaborate monthly across VISNs via a virtual platform. They share strong practices, seek advice from one another, and compare outcomes on an established set of goals.

The HITs use process improvement tools to systematically assess the current steps involved in care. At the close of each year, the HITs analyze the current state of operations and set goals to improve over the following year guided by a target state map. Seed funding is provided to every VISN HIT annually to launch change initiatives. Many VISN HITs use these funds to support a VISN HIT coordinator, and HITs also use this financial support to conduct 2- to 3-day process improvement workshops and to purchase supplies, such as point-of-care testing kits. The HIT communication and work are predominantly executed virtually.

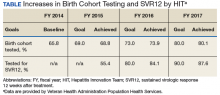

Each year, teams worked toward achieving goals set nationally. These included increasing HCV birth cohort testing and improving the percentage of patients who had SVR12 testing

(Table).

the percentage of patients who received SVR12 testing posttreatment completion was not included in the HIT Collaborative’s annual goals for the first year of the program. Recognizing this as a critical area for improvement, the HIT CLT set a goal to test 80% of all patients who completed treatment. The HITs applied Lean tools to identify and overcome gaps in the SVR12 testing process. By the end of the second year, 84% of all patients who completed treatment had been tested for SVR12.

The HITs also set specific local VISN and medical center goals, prioritizing projects that could have the greatest impact on local patient access and quality of care and build on existing strengths and address barriers. These projects encompass a wide range of areas that contribute to the overall national goals.

Focus on Lean

Lean process improvement is based on 2 key pillars: respect for people (those seeking service as customers and patients and those providing service as frontline staff and stakeholders) and continuous improvement. With Lean, personnel providing care should work to identify and eliminate waste in the system and to streamline care delivery to maximize process steps that are most valued by patients (eg, interaction with a clinical provider) and minimize those that are not valued (eg, time spent waiting to see a provider). With the knowledge that HHRC fully supports their work, HITs were encouraged to innovate based on local resources, context, and culture.

Teams receive basic training in Lean from the HIT CLT and local systems redesign specialists if available. The HITs apply the A3 structured approach to problem solving.11 The HITs follow prescribed problemsolving steps that help identify where to focus process improvement efforts, including analyzing the current state of care, outlining the target state, and prioritizing solution

approaches based on what will have the highest impact for patients.

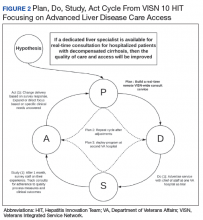

to accommodate the outcomes they observe (Figure 2).

Innovations

Over the course of the HIT Collaborative, numerous innovations have emerged to address and mitigate barriers to HCV screening and treatment. Examples of successful innovations include the following:

- To address transportation issues, several teams developed programs specific to patients with HCV in rural locations or with limited mobility. Mobile vans and units traditionally used as mobile cardiology clinics were transformed into HCV clinics, bringing testing and treatment services directly to veterans;

- Pharmacists and social workers developed outreach strategies to locate homeless veterans, provide point-of-care testing and utilize mobile technology to concurrently enroll and link veterans to care; and

- Many liver care teams partnered with inpatient and outpatient substance use treatment clinics to provide patient education and coordinate HCV treatment.

Inter-VISN working groups developed systemwide tools to address common needs. In the program’s first year, a few medical facilities across a handful of VISNs shared local population health management systems, programming, and best practices. Over time, this working group combined the virtual networking capacity of the HIT Collaborative with technical expertise to promote rapid dissemination and uptake of a population health management system. Providers at medical centers across VA use the tools to identify veterans who should be screened and treated for HCV with the ability to continuously update information, identifying patients who do not respond to treatment or patients overdue for SVR12 testing.

Providers with experience using telehepatology formed another inter-VISN working group. These subject matter experts provided guidance to care teams interested in implementing telehealth in areas where limited local resources or knowledge had prevented them from moving forward. The ability to build a strong coalition across content areas fostered a collaborative learning environment, adaptable to implementing new processes and technologies.

In 2017, the VA made significant efforts to reach out to veterans eligible for VA care who had not yet been screened or remained untreated. In May, Hepatitis Awareness Month, HITs held HCV testing and community outreach events and participated in veteran stand-downs and veteran service organization activities.

Evaluation

Since 2014, the VA has increased its HCV treatment and screening rates. To assess the components contributing to these achievements and the role of the HIT Collaborative in driving this success, a team of implementation scientists have been working with the CLT to conduct a HIT program evaluation. The goal of the evaluation is to establish the impact of the HIT Collaborative. The evaluation team catalogs the activities of the Collaborative and the HITs and assesses implementation strategies (use of specific techniques) to increase the uptake of evidence-based practices specifically related to HCV treatment.12

At the close of each FY, HCV providers and members of the HIT Collaborative are queried through an online survey to determine which strategies have been used to improve HCV care and how these strategies were associated with the HIT Collaborative. The use of more strategies was associated with more HCV treatment initiations.13 All utilized strategies were identified whether or not they were associated with treatment starts. These data are being used to understand which combinations of strategies are most effective at increasing treatment for HCV in the VA and to inform future initiatives.

Expanding the Scope