User login

A practical guide to the management of phobias

THE CASE

Joe S* is a 25-year-old white man who lives with his mother and has a 5-year history of worsening hypertension. He recently presented to the clinic with heart palpitations, shortness of breath, abdominal distress, and dizziness. He said that it was difficult for him to leave his home due to the intense fear he experiences. He said that these symptoms did not occur at home, nor when he visited specific “safe” locations, such as his girlfriend’s apartment. He reported that his fear had increased over the previous 2 years, and that he had progressively limited the distance he traveled from home. He also reported difficulty being in crowds and said, “The idea of going to the movies is torture.”

●

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

The most prevalent psychiatric maladies in primary care are anxiety and mood disorders.1,2 Anxiety disorders are patterns of maladaptive behaviors in conjunction with or response to excessive fear or anxiety.3 The most prevalent anxiety disorder in the United States is specific phobia, the fear of a particular object or situation, with a 12-month prevalence rate of 12.1%.2

Other phobias diagnosed separately in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), include social phobia and agoraphobia, which are, respectively, the fear of being negatively evaluated in social situations and the fear of being trapped in public/open spaces. Social phobia and agoraphobia have diagnostic criteria nearly identical to those of simple phobias regarding the fear response, with the primary differences being the specific phobic situations or stimuli.

Unfortunately, these phobias are likely to be undiagnosed and untreated in primary care partly because patients may not seek treatment.4-6 The ease of avoiding some phobic situations contributes to a lack of treatment seeking.5 Furthermore, commonly used brief measures for psychiatric conditions generally identify depression and anxiety but not phobias. However, family physicians do have resources not only to diagnose these disorders, but also to work with patients to ameliorate them. Collaboration with behavioral health providers is key, as patients with phobias generally benefit from cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), while those with comorbid psychiatric conditions may benefit from a combination of CBT and medication.

Phobic response vs adaptive fear and anxiety

The terms anxiety and fear often overlap when used to describe a negative emotional state of arousal. However, fear is a response to an actual (or perceived) imminent threat, whereas anxiety is the response to a perceived future threat.3 Fear, although unpleasant, serves an adaptive function in responding to immediate danger.7 Anxiety, in turn, may represent an adaptive function for future activities associated with fear. For example, a cave dweller having seen a bear enter a cave in the past (fear-evoking stimulus) may experience anxiety when exploring a different cave (anxiety that a bear may be present). In this situation, the cave dweller’s fear and anxiety responses are important for survival.

Continue to: With phobias...

With phobias, the fear and anxiety responses become maladaptive.3 Specifically, they involve inaccurate beliefs about a specific type of stimulus that could be an object (snake), environment (ocean), or situation (crowded room). Accompanying the maladaptive thoughts are correspondingly exaggerated emotions, physiologic effects, and behavioral responses in alignment with one another.8 The development of this response and the etiology of phobias is complex and is still being debated.7,9,10 Research points to 4 primary pathways: direct psychological conditioning, modeling (watching others), instruction/information, and nonassociative (innate) acquisition.7,10 While the first 3 pathways involve learned responses, the last results from biological predispositions.

DIAGNOSING PHOBIAS: WHAT TO ZERO IN ON

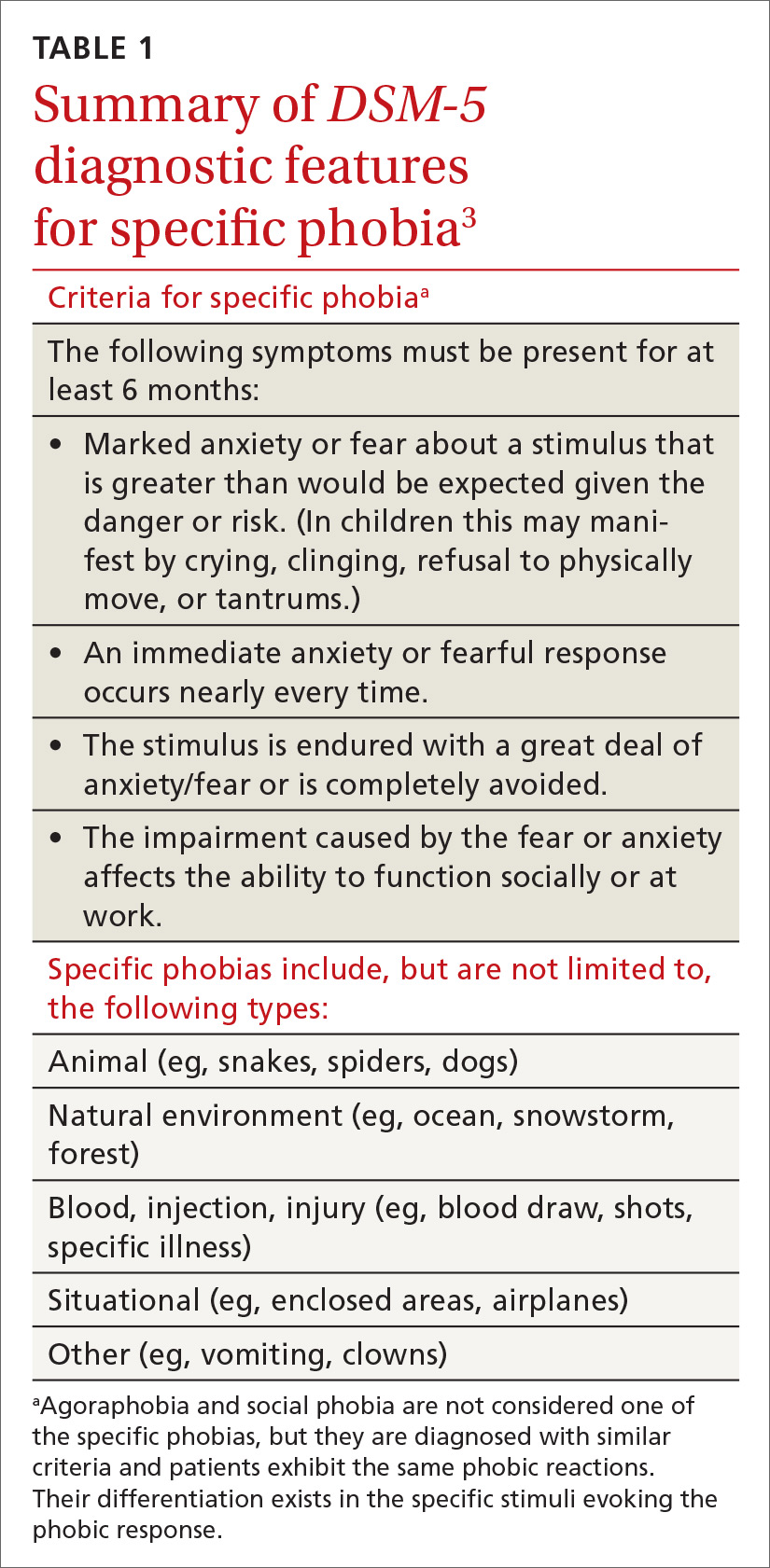

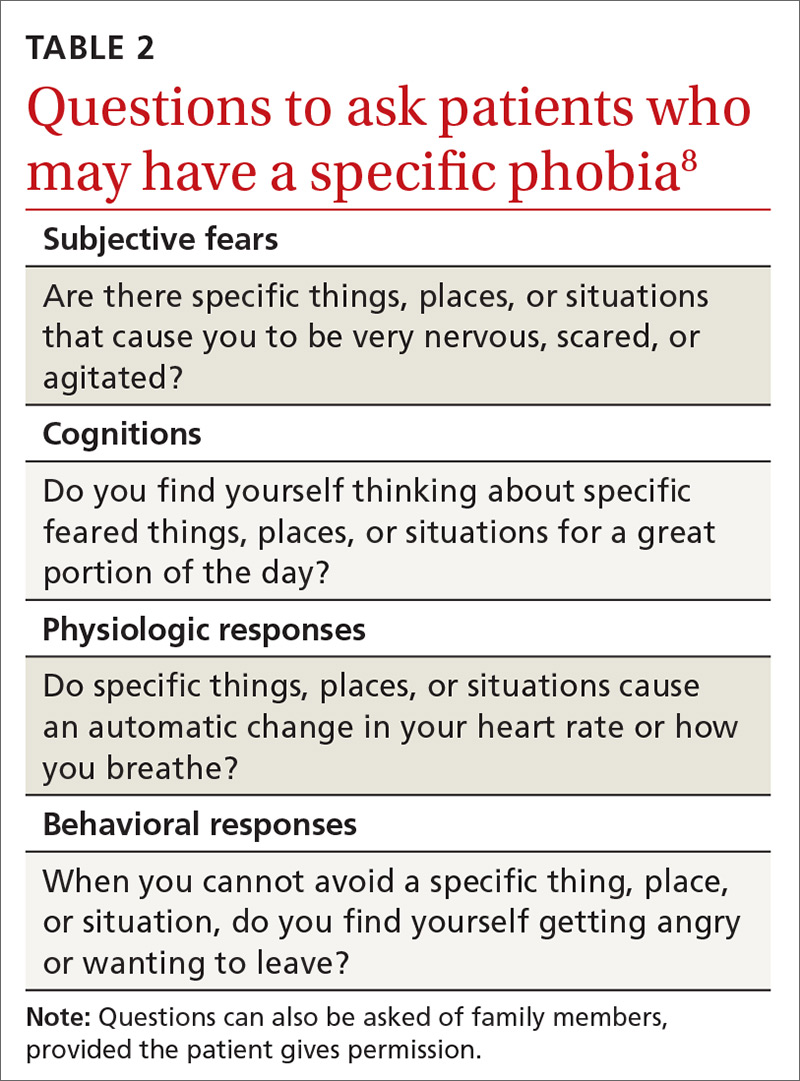

DSM-5 provides diagnostic criteria for specific phobia, agoraphobia, and social phobia, with each diagnosis requiring that symptoms be present for at least 6 months (TABLE 1).3 Diagnosis of phobias should include evaluation of 4 components of a patient’s functioning: subjective fears, cognitions, physiologic responses, and behaviors.8

- Subjective fears: the patient’s described level of distress/agitation to a specific stimulus.

- Cognitions: the patient’s thoughts/beliefs regarding the stimulus.

- Physiologic responses: changes in heart rate, respiration, blood pressure, and other sympathetic nervous system responses with exposure to stimuli.

- Behavioral responses: the most common response is avoidance, with displays of anger, irritability, or apprehension when avoidance of the stimulus is impossible.

Evaluating these 4 components can be accomplished with structured interviews, behavioral observations, or collateral reports from family members or the patient’s peers.8 Thorough questioning and evaluation (TABLE 28) can enable accurate differentiation between phobias unique to specific stimuli and other DSM-5 disorders that might cause similar symptoms. For example, a patient diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) might have a fear response even when triggering stimuli are not present. Identification of a clear, life-threatening incident could help with a differential between phobias and PTSD. However, a patient could be diagnosed with both disorders, as the 2 conditions are not mutually exclusive.

The physiologic and behavioral response symptoms of phobia can also mimic purely medical conditions. Hypertension or tachycardia observed during a medical visit could be due to the fear associated with agoraphobia or with a medically related specific phobia. Blood pressure elevated during testing at the medical appointment could be normal with at-home monitoring by the patient. Thus, blood pressure and heart rate screenings performed at home instead of in public places may help to rule out whether potentially elevated numbers are related to a fear response. Fear and avoidance-like symptoms can also be due to substance abuse, and appropriate drug screening can provide information for an accurate diagnosis.

HOW BEST TO TREAT PHOBIAS

Although research demonstrates that a variety of psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic treatments are efficacious for phobias, in some instances the true utility of an intervention to meaningfully improve a patient’s life is questionable. The issue is that the research evaluating treatment often evaluates only one component of a phobic response (eg,

Continue to: Psychotherapeutic interventions...

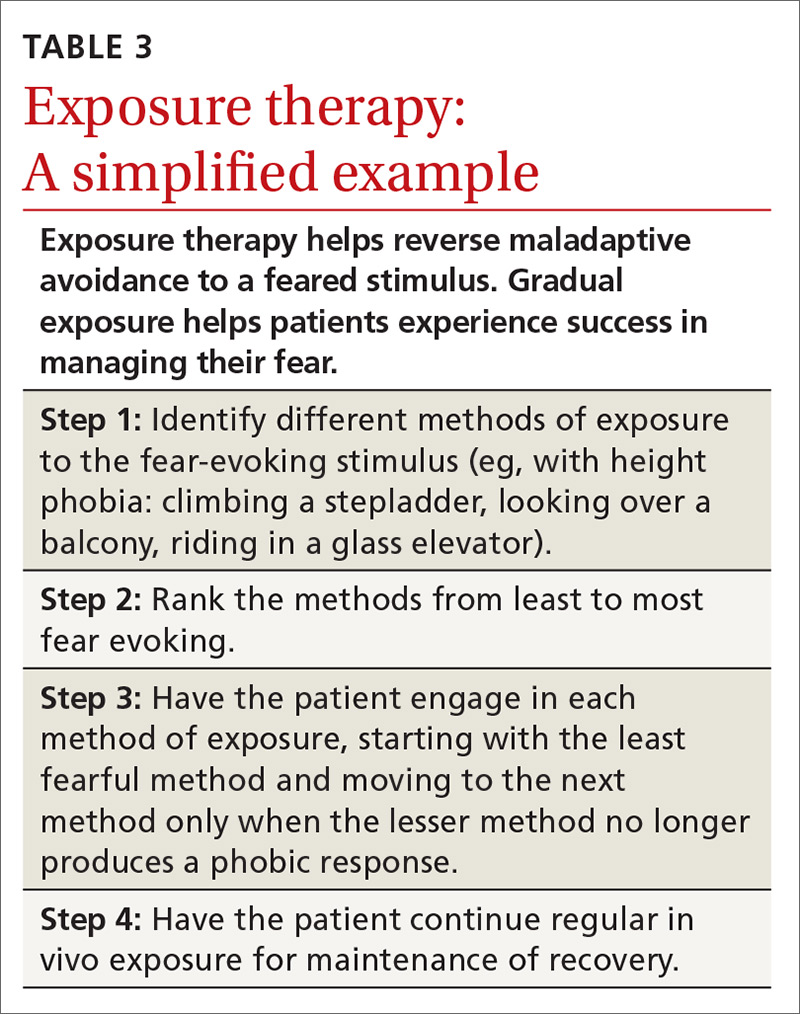

Psychotherapeutic interventions for phobias have shown substantial benefit. CBT is helpful, with the most efficacious technique being exposure therapy.5,6,8,11,12 CBT can begin during the initial primary care visit with the family physician educating the patient about phobias and available treatments.

With exposure therapy, patients are introduced to the source of anxiety over time, whereby they learn to manage the distress

Pharmacologic interventions—specifically selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)—have been effective in treating social phobia and agoraphobia.6 However, treatment of specific phobias via pharmacologic interventions is not supported due to limited efficacy and few studies for SSRIs and SNRIs.5,6

Benzodiazepines, although effective in alleviating some phobic symptoms, are not recommended per current guidelines due to adverse effects and potential exacerbation of the phobic response once discontinued.5,6 This poor result with benzodiazepines may be due to the absence of simultaneous emotional exposure to the feared stimuli. Unfortunately, little research has been done on the long-term effects of pharmacologic intervention once the treatment has been discontinued.11 So, for medication, the question of how long treatment effect lasts after discontinuation remains unanswered.

THE CASE

Mr. S’s family physician diagnosed his condition as agoraphobia with panic attacks. He was prescribed sertraline for his panic attacks and referred for CBT with a psychologist. CBT focused on cognitive restructuring as well as gradual exposure where he would travel with increasing distances to various locations. After 10 months of treatment, Mr. S was able to overcome the agoraphobia and took an “awesome” vacation. He also reported a significant decrease in panic symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott A. Fields, PhD, 3200 MacCorkle Avenue Southeast, 5th Floor, Robert C. Byrd Clinical Teaching Center, Department of Family Medicine, Charleston, WV 25304; sfields@hsc.wvu.edu.

1. Simon G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, et al. Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1995; 152:352-357.

2. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve‐month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012; 21:169-184.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:189-233.

4. Bandelow B, Michaelis S. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders in the 21st century. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2015; 17:327-335.

5. Choy Y, Fyer AJ, Lipsitz JD. Treatment of specific phobia in adults. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007; 27:266-286.

6. Bandelow B, Michaelis S, Wedekind D. Treatment of anxiety disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2017; 19:93-107.

7. Poulton R, Menzies RG. Non-associative fear acquisition: a review of the evidence from retrospective and longitudinal research. Behav Res Ther. 2002; 40:127-149.

8. Davis III TE, Ollendick TH. Empirically supported treatments for specific phobia in children: Do efficacious treatments address the components of a phobic response? Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2005; 12:144-160.

9. Field AP. Is conditioning a useful framework for understanding the development and treatment of phobias? Clin Psychol Rev. 2006; 26:857-875.

10. King NJ, Eleonora G, Ollendick TH. Etiology of childhood phobias: current status of Rachman’s three pathways theory. Behav Res Ther. 1998; 36:297-309.

11. Fedoroff IC, Taylor S. Psychological and pharmacological treatments of social phobia: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001; 21:311-324.

12. Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Horowitz JD, Powers MB, et al. Psychological approaches in the treatment of specific phobias: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008; 28:1021-1037.

13. Zlomke K, Davis III TE. One-session treatment of specific phobias: a detailed description and review of treatment efficacy. Behav Ther. 2008; 39:207-223.

THE CASE

Joe S* is a 25-year-old white man who lives with his mother and has a 5-year history of worsening hypertension. He recently presented to the clinic with heart palpitations, shortness of breath, abdominal distress, and dizziness. He said that it was difficult for him to leave his home due to the intense fear he experiences. He said that these symptoms did not occur at home, nor when he visited specific “safe” locations, such as his girlfriend’s apartment. He reported that his fear had increased over the previous 2 years, and that he had progressively limited the distance he traveled from home. He also reported difficulty being in crowds and said, “The idea of going to the movies is torture.”

●

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

The most prevalent psychiatric maladies in primary care are anxiety and mood disorders.1,2 Anxiety disorders are patterns of maladaptive behaviors in conjunction with or response to excessive fear or anxiety.3 The most prevalent anxiety disorder in the United States is specific phobia, the fear of a particular object or situation, with a 12-month prevalence rate of 12.1%.2

Other phobias diagnosed separately in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), include social phobia and agoraphobia, which are, respectively, the fear of being negatively evaluated in social situations and the fear of being trapped in public/open spaces. Social phobia and agoraphobia have diagnostic criteria nearly identical to those of simple phobias regarding the fear response, with the primary differences being the specific phobic situations or stimuli.

Unfortunately, these phobias are likely to be undiagnosed and untreated in primary care partly because patients may not seek treatment.4-6 The ease of avoiding some phobic situations contributes to a lack of treatment seeking.5 Furthermore, commonly used brief measures for psychiatric conditions generally identify depression and anxiety but not phobias. However, family physicians do have resources not only to diagnose these disorders, but also to work with patients to ameliorate them. Collaboration with behavioral health providers is key, as patients with phobias generally benefit from cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), while those with comorbid psychiatric conditions may benefit from a combination of CBT and medication.

Phobic response vs adaptive fear and anxiety

The terms anxiety and fear often overlap when used to describe a negative emotional state of arousal. However, fear is a response to an actual (or perceived) imminent threat, whereas anxiety is the response to a perceived future threat.3 Fear, although unpleasant, serves an adaptive function in responding to immediate danger.7 Anxiety, in turn, may represent an adaptive function for future activities associated with fear. For example, a cave dweller having seen a bear enter a cave in the past (fear-evoking stimulus) may experience anxiety when exploring a different cave (anxiety that a bear may be present). In this situation, the cave dweller’s fear and anxiety responses are important for survival.

Continue to: With phobias...

With phobias, the fear and anxiety responses become maladaptive.3 Specifically, they involve inaccurate beliefs about a specific type of stimulus that could be an object (snake), environment (ocean), or situation (crowded room). Accompanying the maladaptive thoughts are correspondingly exaggerated emotions, physiologic effects, and behavioral responses in alignment with one another.8 The development of this response and the etiology of phobias is complex and is still being debated.7,9,10 Research points to 4 primary pathways: direct psychological conditioning, modeling (watching others), instruction/information, and nonassociative (innate) acquisition.7,10 While the first 3 pathways involve learned responses, the last results from biological predispositions.

DIAGNOSING PHOBIAS: WHAT TO ZERO IN ON

DSM-5 provides diagnostic criteria for specific phobia, agoraphobia, and social phobia, with each diagnosis requiring that symptoms be present for at least 6 months (TABLE 1).3 Diagnosis of phobias should include evaluation of 4 components of a patient’s functioning: subjective fears, cognitions, physiologic responses, and behaviors.8

- Subjective fears: the patient’s described level of distress/agitation to a specific stimulus.

- Cognitions: the patient’s thoughts/beliefs regarding the stimulus.

- Physiologic responses: changes in heart rate, respiration, blood pressure, and other sympathetic nervous system responses with exposure to stimuli.

- Behavioral responses: the most common response is avoidance, with displays of anger, irritability, or apprehension when avoidance of the stimulus is impossible.

Evaluating these 4 components can be accomplished with structured interviews, behavioral observations, or collateral reports from family members or the patient’s peers.8 Thorough questioning and evaluation (TABLE 28) can enable accurate differentiation between phobias unique to specific stimuli and other DSM-5 disorders that might cause similar symptoms. For example, a patient diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) might have a fear response even when triggering stimuli are not present. Identification of a clear, life-threatening incident could help with a differential between phobias and PTSD. However, a patient could be diagnosed with both disorders, as the 2 conditions are not mutually exclusive.

The physiologic and behavioral response symptoms of phobia can also mimic purely medical conditions. Hypertension or tachycardia observed during a medical visit could be due to the fear associated with agoraphobia or with a medically related specific phobia. Blood pressure elevated during testing at the medical appointment could be normal with at-home monitoring by the patient. Thus, blood pressure and heart rate screenings performed at home instead of in public places may help to rule out whether potentially elevated numbers are related to a fear response. Fear and avoidance-like symptoms can also be due to substance abuse, and appropriate drug screening can provide information for an accurate diagnosis.

HOW BEST TO TREAT PHOBIAS

Although research demonstrates that a variety of psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic treatments are efficacious for phobias, in some instances the true utility of an intervention to meaningfully improve a patient’s life is questionable. The issue is that the research evaluating treatment often evaluates only one component of a phobic response (eg,

Continue to: Psychotherapeutic interventions...

Psychotherapeutic interventions for phobias have shown substantial benefit. CBT is helpful, with the most efficacious technique being exposure therapy.5,6,8,11,12 CBT can begin during the initial primary care visit with the family physician educating the patient about phobias and available treatments.

With exposure therapy, patients are introduced to the source of anxiety over time, whereby they learn to manage the distress

Pharmacologic interventions—specifically selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)—have been effective in treating social phobia and agoraphobia.6 However, treatment of specific phobias via pharmacologic interventions is not supported due to limited efficacy and few studies for SSRIs and SNRIs.5,6

Benzodiazepines, although effective in alleviating some phobic symptoms, are not recommended per current guidelines due to adverse effects and potential exacerbation of the phobic response once discontinued.5,6 This poor result with benzodiazepines may be due to the absence of simultaneous emotional exposure to the feared stimuli. Unfortunately, little research has been done on the long-term effects of pharmacologic intervention once the treatment has been discontinued.11 So, for medication, the question of how long treatment effect lasts after discontinuation remains unanswered.

THE CASE

Mr. S’s family physician diagnosed his condition as agoraphobia with panic attacks. He was prescribed sertraline for his panic attacks and referred for CBT with a psychologist. CBT focused on cognitive restructuring as well as gradual exposure where he would travel with increasing distances to various locations. After 10 months of treatment, Mr. S was able to overcome the agoraphobia and took an “awesome” vacation. He also reported a significant decrease in panic symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott A. Fields, PhD, 3200 MacCorkle Avenue Southeast, 5th Floor, Robert C. Byrd Clinical Teaching Center, Department of Family Medicine, Charleston, WV 25304; sfields@hsc.wvu.edu.

THE CASE

Joe S* is a 25-year-old white man who lives with his mother and has a 5-year history of worsening hypertension. He recently presented to the clinic with heart palpitations, shortness of breath, abdominal distress, and dizziness. He said that it was difficult for him to leave his home due to the intense fear he experiences. He said that these symptoms did not occur at home, nor when he visited specific “safe” locations, such as his girlfriend’s apartment. He reported that his fear had increased over the previous 2 years, and that he had progressively limited the distance he traveled from home. He also reported difficulty being in crowds and said, “The idea of going to the movies is torture.”

●

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

The most prevalent psychiatric maladies in primary care are anxiety and mood disorders.1,2 Anxiety disorders are patterns of maladaptive behaviors in conjunction with or response to excessive fear or anxiety.3 The most prevalent anxiety disorder in the United States is specific phobia, the fear of a particular object or situation, with a 12-month prevalence rate of 12.1%.2

Other phobias diagnosed separately in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), include social phobia and agoraphobia, which are, respectively, the fear of being negatively evaluated in social situations and the fear of being trapped in public/open spaces. Social phobia and agoraphobia have diagnostic criteria nearly identical to those of simple phobias regarding the fear response, with the primary differences being the specific phobic situations or stimuli.

Unfortunately, these phobias are likely to be undiagnosed and untreated in primary care partly because patients may not seek treatment.4-6 The ease of avoiding some phobic situations contributes to a lack of treatment seeking.5 Furthermore, commonly used brief measures for psychiatric conditions generally identify depression and anxiety but not phobias. However, family physicians do have resources not only to diagnose these disorders, but also to work with patients to ameliorate them. Collaboration with behavioral health providers is key, as patients with phobias generally benefit from cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), while those with comorbid psychiatric conditions may benefit from a combination of CBT and medication.

Phobic response vs adaptive fear and anxiety

The terms anxiety and fear often overlap when used to describe a negative emotional state of arousal. However, fear is a response to an actual (or perceived) imminent threat, whereas anxiety is the response to a perceived future threat.3 Fear, although unpleasant, serves an adaptive function in responding to immediate danger.7 Anxiety, in turn, may represent an adaptive function for future activities associated with fear. For example, a cave dweller having seen a bear enter a cave in the past (fear-evoking stimulus) may experience anxiety when exploring a different cave (anxiety that a bear may be present). In this situation, the cave dweller’s fear and anxiety responses are important for survival.

Continue to: With phobias...

With phobias, the fear and anxiety responses become maladaptive.3 Specifically, they involve inaccurate beliefs about a specific type of stimulus that could be an object (snake), environment (ocean), or situation (crowded room). Accompanying the maladaptive thoughts are correspondingly exaggerated emotions, physiologic effects, and behavioral responses in alignment with one another.8 The development of this response and the etiology of phobias is complex and is still being debated.7,9,10 Research points to 4 primary pathways: direct psychological conditioning, modeling (watching others), instruction/information, and nonassociative (innate) acquisition.7,10 While the first 3 pathways involve learned responses, the last results from biological predispositions.

DIAGNOSING PHOBIAS: WHAT TO ZERO IN ON

DSM-5 provides diagnostic criteria for specific phobia, agoraphobia, and social phobia, with each diagnosis requiring that symptoms be present for at least 6 months (TABLE 1).3 Diagnosis of phobias should include evaluation of 4 components of a patient’s functioning: subjective fears, cognitions, physiologic responses, and behaviors.8

- Subjective fears: the patient’s described level of distress/agitation to a specific stimulus.

- Cognitions: the patient’s thoughts/beliefs regarding the stimulus.

- Physiologic responses: changes in heart rate, respiration, blood pressure, and other sympathetic nervous system responses with exposure to stimuli.

- Behavioral responses: the most common response is avoidance, with displays of anger, irritability, or apprehension when avoidance of the stimulus is impossible.

Evaluating these 4 components can be accomplished with structured interviews, behavioral observations, or collateral reports from family members or the patient’s peers.8 Thorough questioning and evaluation (TABLE 28) can enable accurate differentiation between phobias unique to specific stimuli and other DSM-5 disorders that might cause similar symptoms. For example, a patient diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) might have a fear response even when triggering stimuli are not present. Identification of a clear, life-threatening incident could help with a differential between phobias and PTSD. However, a patient could be diagnosed with both disorders, as the 2 conditions are not mutually exclusive.

The physiologic and behavioral response symptoms of phobia can also mimic purely medical conditions. Hypertension or tachycardia observed during a medical visit could be due to the fear associated with agoraphobia or with a medically related specific phobia. Blood pressure elevated during testing at the medical appointment could be normal with at-home monitoring by the patient. Thus, blood pressure and heart rate screenings performed at home instead of in public places may help to rule out whether potentially elevated numbers are related to a fear response. Fear and avoidance-like symptoms can also be due to substance abuse, and appropriate drug screening can provide information for an accurate diagnosis.

HOW BEST TO TREAT PHOBIAS

Although research demonstrates that a variety of psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic treatments are efficacious for phobias, in some instances the true utility of an intervention to meaningfully improve a patient’s life is questionable. The issue is that the research evaluating treatment often evaluates only one component of a phobic response (eg,

Continue to: Psychotherapeutic interventions...

Psychotherapeutic interventions for phobias have shown substantial benefit. CBT is helpful, with the most efficacious technique being exposure therapy.5,6,8,11,12 CBT can begin during the initial primary care visit with the family physician educating the patient about phobias and available treatments.

With exposure therapy, patients are introduced to the source of anxiety over time, whereby they learn to manage the distress

Pharmacologic interventions—specifically selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)—have been effective in treating social phobia and agoraphobia.6 However, treatment of specific phobias via pharmacologic interventions is not supported due to limited efficacy and few studies for SSRIs and SNRIs.5,6

Benzodiazepines, although effective in alleviating some phobic symptoms, are not recommended per current guidelines due to adverse effects and potential exacerbation of the phobic response once discontinued.5,6 This poor result with benzodiazepines may be due to the absence of simultaneous emotional exposure to the feared stimuli. Unfortunately, little research has been done on the long-term effects of pharmacologic intervention once the treatment has been discontinued.11 So, for medication, the question of how long treatment effect lasts after discontinuation remains unanswered.

THE CASE

Mr. S’s family physician diagnosed his condition as agoraphobia with panic attacks. He was prescribed sertraline for his panic attacks and referred for CBT with a psychologist. CBT focused on cognitive restructuring as well as gradual exposure where he would travel with increasing distances to various locations. After 10 months of treatment, Mr. S was able to overcome the agoraphobia and took an “awesome” vacation. He also reported a significant decrease in panic symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott A. Fields, PhD, 3200 MacCorkle Avenue Southeast, 5th Floor, Robert C. Byrd Clinical Teaching Center, Department of Family Medicine, Charleston, WV 25304; sfields@hsc.wvu.edu.

1. Simon G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, et al. Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1995; 152:352-357.

2. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve‐month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012; 21:169-184.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:189-233.

4. Bandelow B, Michaelis S. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders in the 21st century. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2015; 17:327-335.

5. Choy Y, Fyer AJ, Lipsitz JD. Treatment of specific phobia in adults. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007; 27:266-286.

6. Bandelow B, Michaelis S, Wedekind D. Treatment of anxiety disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2017; 19:93-107.

7. Poulton R, Menzies RG. Non-associative fear acquisition: a review of the evidence from retrospective and longitudinal research. Behav Res Ther. 2002; 40:127-149.

8. Davis III TE, Ollendick TH. Empirically supported treatments for specific phobia in children: Do efficacious treatments address the components of a phobic response? Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2005; 12:144-160.

9. Field AP. Is conditioning a useful framework for understanding the development and treatment of phobias? Clin Psychol Rev. 2006; 26:857-875.

10. King NJ, Eleonora G, Ollendick TH. Etiology of childhood phobias: current status of Rachman’s three pathways theory. Behav Res Ther. 1998; 36:297-309.

11. Fedoroff IC, Taylor S. Psychological and pharmacological treatments of social phobia: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001; 21:311-324.

12. Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Horowitz JD, Powers MB, et al. Psychological approaches in the treatment of specific phobias: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008; 28:1021-1037.

13. Zlomke K, Davis III TE. One-session treatment of specific phobias: a detailed description and review of treatment efficacy. Behav Ther. 2008; 39:207-223.

1. Simon G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, et al. Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1995; 152:352-357.

2. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve‐month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012; 21:169-184.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:189-233.

4. Bandelow B, Michaelis S. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders in the 21st century. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2015; 17:327-335.

5. Choy Y, Fyer AJ, Lipsitz JD. Treatment of specific phobia in adults. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007; 27:266-286.

6. Bandelow B, Michaelis S, Wedekind D. Treatment of anxiety disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2017; 19:93-107.

7. Poulton R, Menzies RG. Non-associative fear acquisition: a review of the evidence from retrospective and longitudinal research. Behav Res Ther. 2002; 40:127-149.

8. Davis III TE, Ollendick TH. Empirically supported treatments for specific phobia in children: Do efficacious treatments address the components of a phobic response? Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2005; 12:144-160.

9. Field AP. Is conditioning a useful framework for understanding the development and treatment of phobias? Clin Psychol Rev. 2006; 26:857-875.

10. King NJ, Eleonora G, Ollendick TH. Etiology of childhood phobias: current status of Rachman’s three pathways theory. Behav Res Ther. 1998; 36:297-309.

11. Fedoroff IC, Taylor S. Psychological and pharmacological treatments of social phobia: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001; 21:311-324.

12. Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Horowitz JD, Powers MB, et al. Psychological approaches in the treatment of specific phobias: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008; 28:1021-1037.

13. Zlomke K, Davis III TE. One-session treatment of specific phobias: a detailed description and review of treatment efficacy. Behav Ther. 2008; 39:207-223.