User login

How to screen for and treat teen alcohol use

THE CASE

Paul F* is a 16-year-old White boy who lives with his mother and spends some weekends with his father who has shared custody. He recently presented to the clinic for treatment due to an arrest for disorderly conduct at school. He and a friend were found drinking liquor outside the school building when they were scheduled to be in class. Paul reported that he and his friends often drink at school and at extracurricular functions. He has been using alcohol for the past 2 years, with escalating consumption (5 or more drinks per episode) in the past year. Paul has been drinking most days of the week and has even driven under the influence at times. He said, “I just feel happier when I am drinking.” An accomplished soccer player recruited by colleges, Paul recently was suspended from the team due to his poor grades. His response was, “It’s stupid anyway. What’s the point of playing?”

●

* The patient’s name and some personal details have been changed to protect his identity.

Alcohol is the number 1 substance of abuse for adolescents, used more than tobacco or drugs.1-3 In 2007 and again in 2016, the Surgeon General of the United States issued reports to highlight this important topic,1,2 noting that early and repeated exposure to alcohol during this crucial time of brain development increases the risk for future problems, including addiction.2

Adolescent alcohol use is often underestimated by parents and physicians, including misjudging how much, how often, and how young children are when they begin to drink.1 Boys and girls tend to start drinking at similar ages (13.9 and 14.4 years, respectively),3 but as girls age, they tend to drink more and binge more.4 In 2019, 1 in 4 adolescents reported drinking and more than 4 million reported at least 1 episode of binge drinking in the prior month.4 These numbers have further ramifications: early drinking is associated with alcohol dependence, relapse, use of other substances, risky sexual behaviors, injurious behaviors, suicide, motor vehicle accidents, and dating violence.4-6

Diagnosing alcohol use disorder

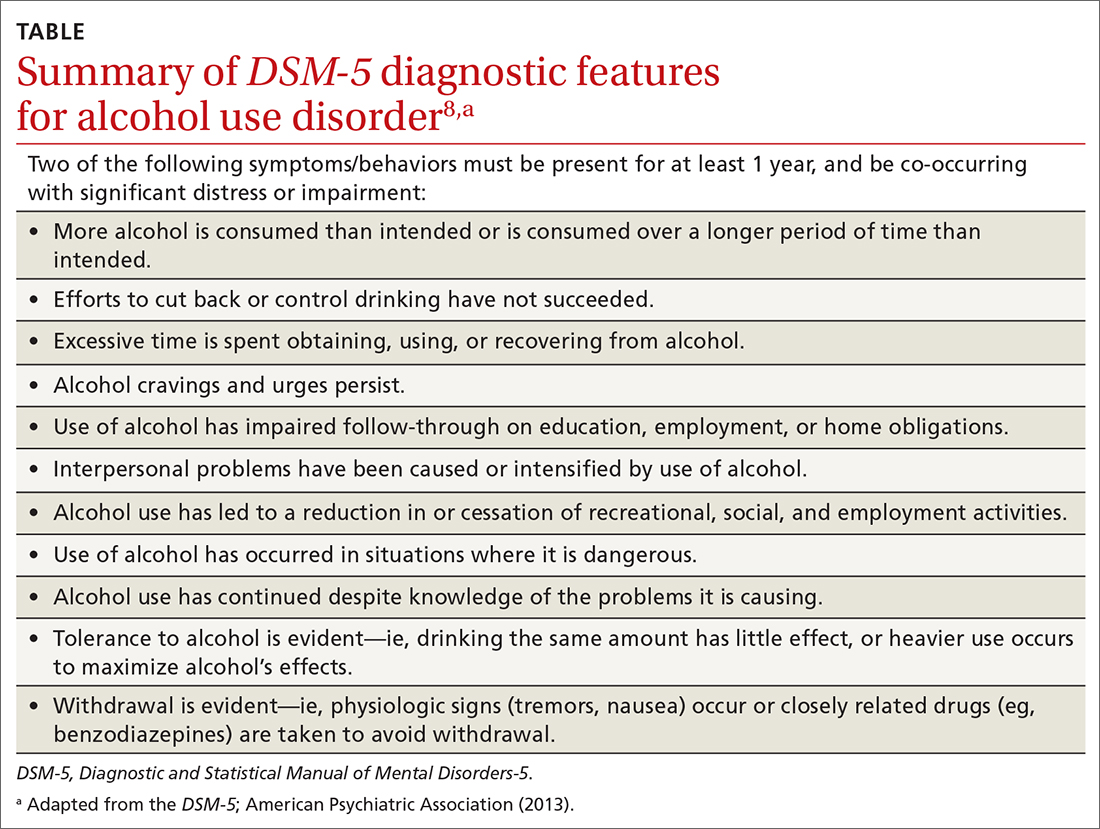

The range of alcohol use includes consumption, bingeing, abuse, and dependence.7,8 Consumption is defined as the drinking of alcoholic beverages. Bingeing is the consumption of more than 5 drinks for men or 4 drinks for women in 2 hours, according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.7 However, the criterion is slightly different for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, which broadens the timeframe to “on the same occasion.”9 While previously known as separate disorders, alcohol abuse (or misuse) and alcohol dependence are now diagnostically classified together as alcohol use disorders (AUDs), per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5).8 AUD is further stratified as mild, moderate, or severe, depending on the number of criteria that are met by the patient (TABLE).8,10

Alcohol screening

Currently, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) does not recommend screening adolescents ages 12 to 17 for AUD, and has instead issued an “I” statement (insufficient evidence).11 While the USPSTF recognizes the potential burdens of adolescent alcohol use, the potential harms of screening include “stigma, anxiety, labeling, discrimination, privacy concerns, and interference with the patient–clinician relationship.”11 The USPSTF also notes that it “did not find any evidence that specifically examined the harms of screening for alcohol use in adolescents.”11

This is at odds with recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), which in 2011 released a policy statement advocating screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for adolescent substance use.12 In the United States, even though 83% of adolescents see a physician at least once each year,12,13 alcohol misuse screening still varies, occurring in the range of 50% to 86% of office visits.12 When screening does occur, it is often based on clinical impression only.12 Studies have shown that when a screening tool is not used, up to two-thirds of substance use disorders may be missed.12-15

Continue to: A full and complete biopsychosocial interview

A full and complete biopsychosocial interview with adolescents is a necessity, and should include queries about alcohol, drugs, and other substances. Acknowledgment of use should trigger further investigation into the substance use areas. Interviews may start with open-ended questions about alcohol use at home or at school before moving to more personalized and detailed questioning and use of screening tools.16

While various screening instruments exist, for the sake of brevity we provide as an example the Screening to Brief Intervention (S2BI) tool. It is an efficient, single-page tool that can help clinicians in their routine care of adolescents to quickly stratify the patient risk of substance use disorder as none/low, moderate, or severe.12 It can be found here: www.mcpap.com/pdf/S2Bi%20Toolkit.pdf (see page 10).

For all patients, but particularly for adolescents, confidentiality is important, and many specialty societies have created language to address this issue.12 Discuss confidentiality with both the adolescent patient and the patient’s caregiver simultaneously, with dialogue that includes: (a) the need to speak with adolescents alone during the office visit, (b) the benefits of confidentiality in the physician–patient relationship, and (c) the need to disclose selected information to keep patients safe.12 Describing the process for required disclosures is essential. Benefits of disclosure include further support for the adolescent patient as well as appropriate parental participation and support for possible referrals.12

Treating AUD

Treatment for AUD should be multifaceted. Screen for comorbid mood disorders, such as generalized anxiety,17,18 social anxiety,18 and depression,19 as well as for insomnia.18 Studies have demonstrated a strong link between insomnia and anxiety, and again between anxiety and AUD.17-19 Finally, screen for adverse childhood events such as trauma, victimization, and abuse.20 Addressing issues discovered in screening allows for more targeted and personalized treatment of AUD.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse categorizes evidence-based treatment into 3 areas: behavioral therapies, family therapies, and medications.21

Continue to: Behavioral therapies

Behavioral therapies can include group therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational enhancement therapy, 12-Step facilitation, and contingency management, in which small rewards or incentives are given for participation in treatment to reinforce positive behaviors.21

Family-based therapies, such as brief strategic family therapy, functional family therapy, and multisystem therapy recognize that adolescents exist in systems of families in communities, and that the patient’s success in treatment may be supported by these relationships.21

Some medications may achieve modest benefit for treatment of adolescents with AUD. Naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram have all been used successfully to treat AUD in adults21; some physicians may choose to use these medications “off label” in adolescents. Bupropion has been used successfully in the treatment of nicotine use disorder,21 and a small study in 2005 showed some success with bupropion in treating adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, comorbid depression, and substance use disorder.22 Naltrexone has also been studied in adolescents with opioid use disorder, although these were not large studies.23

Adolescents with serious, sustained issues with AUD may require more in-depth treatments such as an intensive outpatient program, a partial hospitalization program, or a residential treatment program.15 The least-restrictive environment is preferable.15 Families are generally included as part of the treatment and recovery process in those settings.21 Some patients may require detoxification prior to referral to residential treatment settings; the American Society of Addiction Medicine has published a comprehensive guideline on alcohol withdrawal.24

Paul’s family physician diagnosed his condition as AUD and referred him for CBT with a psychologist, who treated him for both the AUD and an underlying depressive disorder that was later identified. CBT focused on cognitive restructuring of depressive thoughts as well as support for continued abstinence from alcohol. The patient, with family support, declined antidepressant medication.

After 6 months of treatment, Paul and his parents were pleased with his progress. His grades improved to the point that he was permitted to play soccer again, and he was seriously looking at his future college options.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott A. Fields, PhD, 3200 MacCorkle Avenue Southeast, 5th Floor, Robert C. Byrd Clinical Teaching Center, Department of Family Medicine, Charleston, WV 25304; sfields@hsc.wvu.edu

1. US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking. Washington, DC; US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. 2007.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, DC; US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. 2016.

3. Hingson R, White A. New research findings since the 2007 Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking: A review. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2014; 75:158-169.

4. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Underage drinking. National Institute of Health. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/underage-drinking.

5. Hingson R, Zha W, Iannotti R, et al. Physician advice to adolescents about drinking and other health behaviors. Pediatrics. 2013;131:249-257.

6. Schaus JF, Sole ML, McCoy TP, et al. Screening for high-risk drinking in a college student health center: characterizing students based on quantity, frequency, and harms. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2009;16:34-44.

7. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Drinking levels defined. Accessed December 27, 2021. www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking

8. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Arlington, VA; American Psychiatric Association. 2013.

9. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Bringing down binge drinking. Accessed December 27, 2021. www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/programs_campaigns/nation_prevention_week/data-binge-drinking.pdf

10. Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757-766.

11. USPSTF. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;320:1899-1909.

12. Levy SJ, Williams JF, Committee on Substance Use and Prevention. Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20161211.

13. MacKay AP, Duran CP. Adolescent Health in the United States. National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007.

14. Haller DM, Meynard A, Lefebvre D, et al. Effectiveness of training family physicians to deliver a brief intervention to address excessive substance use among young patients: a cluster randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2014;186:E263-E272.

15. Borus J, Parhami I, Levy S. Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Child Adolesc Psychiatric Clin N Am. 2016;25:579-601.

16. Knight J, Roberts T, Gabrielli J, et al. Adolescent alcohol and substance use and abuse. Performing preventive services: A bright futures handbook. Accessed December 22, 2021. American Academy of Pediatrics. https://ocfcpacourts.us/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Adolescent_Alcohol_and_Substance_Abuse_001005.pdf

17. Dyer ML, Heron J, Hickman M, et al. Alcohol use in late adolescence and early adulthood: the role of generalized anxiety disorder and drinking to cope motives. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;204:107480.

18. Blumenthal H, Taylor DJ, Cloutier RM, et al. The links between social anxiety disorder, insomnia symptoms, and alcohol use disorders: findings from a large sample of adolescents in the United States. Behav Ther. 2019;50:50-59.

19. Pedrelli P, Shapero B, Archibald A, et al. Alcohol use and depression during adolescence and young adulthood: a summary and interpretation of mixed findings. Curr Addict Rep. 2016;3:91-97.

20. Davis JP, Dworkin ER, Helton J, et al. Extending poly-victimization theory: differential effects of adolescents’ experiences of victimization on substance use disorder diagnoses upon treatment entry. Child Abuse Negl. 2019; 89:165-177.

21. NIDA. Principles of adolescent substance use disorder treatment: a research-based guide. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.drugabuse.gov/publications/principles-adolescent-substance-use-disorder-treatment-research-based-guide

22. Solhkhah R, Wilens TE, Daly J, et al. Bupropion SR for the treatment of substance-abusing outpatient adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and mood disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005:15:777-786.

23. Camenga DR, Colon-Rivera HA, Muvvala SB. Medications for maintenance treatment of opioid use disorder in adolescents. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2019;80:393-402.

24. American Society of Addiction Medicine. The ASAM clinical practice guideline on alcohol withdrawal management. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.asam.org/quality-care/clinical-guidelines/alcohol-withdrawal-management-guideline

THE CASE

Paul F* is a 16-year-old White boy who lives with his mother and spends some weekends with his father who has shared custody. He recently presented to the clinic for treatment due to an arrest for disorderly conduct at school. He and a friend were found drinking liquor outside the school building when they were scheduled to be in class. Paul reported that he and his friends often drink at school and at extracurricular functions. He has been using alcohol for the past 2 years, with escalating consumption (5 or more drinks per episode) in the past year. Paul has been drinking most days of the week and has even driven under the influence at times. He said, “I just feel happier when I am drinking.” An accomplished soccer player recruited by colleges, Paul recently was suspended from the team due to his poor grades. His response was, “It’s stupid anyway. What’s the point of playing?”

●

* The patient’s name and some personal details have been changed to protect his identity.

Alcohol is the number 1 substance of abuse for adolescents, used more than tobacco or drugs.1-3 In 2007 and again in 2016, the Surgeon General of the United States issued reports to highlight this important topic,1,2 noting that early and repeated exposure to alcohol during this crucial time of brain development increases the risk for future problems, including addiction.2

Adolescent alcohol use is often underestimated by parents and physicians, including misjudging how much, how often, and how young children are when they begin to drink.1 Boys and girls tend to start drinking at similar ages (13.9 and 14.4 years, respectively),3 but as girls age, they tend to drink more and binge more.4 In 2019, 1 in 4 adolescents reported drinking and more than 4 million reported at least 1 episode of binge drinking in the prior month.4 These numbers have further ramifications: early drinking is associated with alcohol dependence, relapse, use of other substances, risky sexual behaviors, injurious behaviors, suicide, motor vehicle accidents, and dating violence.4-6

Diagnosing alcohol use disorder

The range of alcohol use includes consumption, bingeing, abuse, and dependence.7,8 Consumption is defined as the drinking of alcoholic beverages. Bingeing is the consumption of more than 5 drinks for men or 4 drinks for women in 2 hours, according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.7 However, the criterion is slightly different for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, which broadens the timeframe to “on the same occasion.”9 While previously known as separate disorders, alcohol abuse (or misuse) and alcohol dependence are now diagnostically classified together as alcohol use disorders (AUDs), per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5).8 AUD is further stratified as mild, moderate, or severe, depending on the number of criteria that are met by the patient (TABLE).8,10

Alcohol screening

Currently, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) does not recommend screening adolescents ages 12 to 17 for AUD, and has instead issued an “I” statement (insufficient evidence).11 While the USPSTF recognizes the potential burdens of adolescent alcohol use, the potential harms of screening include “stigma, anxiety, labeling, discrimination, privacy concerns, and interference with the patient–clinician relationship.”11 The USPSTF also notes that it “did not find any evidence that specifically examined the harms of screening for alcohol use in adolescents.”11

This is at odds with recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), which in 2011 released a policy statement advocating screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for adolescent substance use.12 In the United States, even though 83% of adolescents see a physician at least once each year,12,13 alcohol misuse screening still varies, occurring in the range of 50% to 86% of office visits.12 When screening does occur, it is often based on clinical impression only.12 Studies have shown that when a screening tool is not used, up to two-thirds of substance use disorders may be missed.12-15

Continue to: A full and complete biopsychosocial interview

A full and complete biopsychosocial interview with adolescents is a necessity, and should include queries about alcohol, drugs, and other substances. Acknowledgment of use should trigger further investigation into the substance use areas. Interviews may start with open-ended questions about alcohol use at home or at school before moving to more personalized and detailed questioning and use of screening tools.16

While various screening instruments exist, for the sake of brevity we provide as an example the Screening to Brief Intervention (S2BI) tool. It is an efficient, single-page tool that can help clinicians in their routine care of adolescents to quickly stratify the patient risk of substance use disorder as none/low, moderate, or severe.12 It can be found here: www.mcpap.com/pdf/S2Bi%20Toolkit.pdf (see page 10).

For all patients, but particularly for adolescents, confidentiality is important, and many specialty societies have created language to address this issue.12 Discuss confidentiality with both the adolescent patient and the patient’s caregiver simultaneously, with dialogue that includes: (a) the need to speak with adolescents alone during the office visit, (b) the benefits of confidentiality in the physician–patient relationship, and (c) the need to disclose selected information to keep patients safe.12 Describing the process for required disclosures is essential. Benefits of disclosure include further support for the adolescent patient as well as appropriate parental participation and support for possible referrals.12

Treating AUD

Treatment for AUD should be multifaceted. Screen for comorbid mood disorders, such as generalized anxiety,17,18 social anxiety,18 and depression,19 as well as for insomnia.18 Studies have demonstrated a strong link between insomnia and anxiety, and again between anxiety and AUD.17-19 Finally, screen for adverse childhood events such as trauma, victimization, and abuse.20 Addressing issues discovered in screening allows for more targeted and personalized treatment of AUD.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse categorizes evidence-based treatment into 3 areas: behavioral therapies, family therapies, and medications.21

Continue to: Behavioral therapies

Behavioral therapies can include group therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational enhancement therapy, 12-Step facilitation, and contingency management, in which small rewards or incentives are given for participation in treatment to reinforce positive behaviors.21

Family-based therapies, such as brief strategic family therapy, functional family therapy, and multisystem therapy recognize that adolescents exist in systems of families in communities, and that the patient’s success in treatment may be supported by these relationships.21

Some medications may achieve modest benefit for treatment of adolescents with AUD. Naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram have all been used successfully to treat AUD in adults21; some physicians may choose to use these medications “off label” in adolescents. Bupropion has been used successfully in the treatment of nicotine use disorder,21 and a small study in 2005 showed some success with bupropion in treating adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, comorbid depression, and substance use disorder.22 Naltrexone has also been studied in adolescents with opioid use disorder, although these were not large studies.23

Adolescents with serious, sustained issues with AUD may require more in-depth treatments such as an intensive outpatient program, a partial hospitalization program, or a residential treatment program.15 The least-restrictive environment is preferable.15 Families are generally included as part of the treatment and recovery process in those settings.21 Some patients may require detoxification prior to referral to residential treatment settings; the American Society of Addiction Medicine has published a comprehensive guideline on alcohol withdrawal.24

Paul’s family physician diagnosed his condition as AUD and referred him for CBT with a psychologist, who treated him for both the AUD and an underlying depressive disorder that was later identified. CBT focused on cognitive restructuring of depressive thoughts as well as support for continued abstinence from alcohol. The patient, with family support, declined antidepressant medication.

After 6 months of treatment, Paul and his parents were pleased with his progress. His grades improved to the point that he was permitted to play soccer again, and he was seriously looking at his future college options.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott A. Fields, PhD, 3200 MacCorkle Avenue Southeast, 5th Floor, Robert C. Byrd Clinical Teaching Center, Department of Family Medicine, Charleston, WV 25304; sfields@hsc.wvu.edu

THE CASE

Paul F* is a 16-year-old White boy who lives with his mother and spends some weekends with his father who has shared custody. He recently presented to the clinic for treatment due to an arrest for disorderly conduct at school. He and a friend were found drinking liquor outside the school building when they were scheduled to be in class. Paul reported that he and his friends often drink at school and at extracurricular functions. He has been using alcohol for the past 2 years, with escalating consumption (5 or more drinks per episode) in the past year. Paul has been drinking most days of the week and has even driven under the influence at times. He said, “I just feel happier when I am drinking.” An accomplished soccer player recruited by colleges, Paul recently was suspended from the team due to his poor grades. His response was, “It’s stupid anyway. What’s the point of playing?”

●

* The patient’s name and some personal details have been changed to protect his identity.

Alcohol is the number 1 substance of abuse for adolescents, used more than tobacco or drugs.1-3 In 2007 and again in 2016, the Surgeon General of the United States issued reports to highlight this important topic,1,2 noting that early and repeated exposure to alcohol during this crucial time of brain development increases the risk for future problems, including addiction.2

Adolescent alcohol use is often underestimated by parents and physicians, including misjudging how much, how often, and how young children are when they begin to drink.1 Boys and girls tend to start drinking at similar ages (13.9 and 14.4 years, respectively),3 but as girls age, they tend to drink more and binge more.4 In 2019, 1 in 4 adolescents reported drinking and more than 4 million reported at least 1 episode of binge drinking in the prior month.4 These numbers have further ramifications: early drinking is associated with alcohol dependence, relapse, use of other substances, risky sexual behaviors, injurious behaviors, suicide, motor vehicle accidents, and dating violence.4-6

Diagnosing alcohol use disorder

The range of alcohol use includes consumption, bingeing, abuse, and dependence.7,8 Consumption is defined as the drinking of alcoholic beverages. Bingeing is the consumption of more than 5 drinks for men or 4 drinks for women in 2 hours, according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.7 However, the criterion is slightly different for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, which broadens the timeframe to “on the same occasion.”9 While previously known as separate disorders, alcohol abuse (or misuse) and alcohol dependence are now diagnostically classified together as alcohol use disorders (AUDs), per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5).8 AUD is further stratified as mild, moderate, or severe, depending on the number of criteria that are met by the patient (TABLE).8,10

Alcohol screening

Currently, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) does not recommend screening adolescents ages 12 to 17 for AUD, and has instead issued an “I” statement (insufficient evidence).11 While the USPSTF recognizes the potential burdens of adolescent alcohol use, the potential harms of screening include “stigma, anxiety, labeling, discrimination, privacy concerns, and interference with the patient–clinician relationship.”11 The USPSTF also notes that it “did not find any evidence that specifically examined the harms of screening for alcohol use in adolescents.”11

This is at odds with recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), which in 2011 released a policy statement advocating screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for adolescent substance use.12 In the United States, even though 83% of adolescents see a physician at least once each year,12,13 alcohol misuse screening still varies, occurring in the range of 50% to 86% of office visits.12 When screening does occur, it is often based on clinical impression only.12 Studies have shown that when a screening tool is not used, up to two-thirds of substance use disorders may be missed.12-15

Continue to: A full and complete biopsychosocial interview

A full and complete biopsychosocial interview with adolescents is a necessity, and should include queries about alcohol, drugs, and other substances. Acknowledgment of use should trigger further investigation into the substance use areas. Interviews may start with open-ended questions about alcohol use at home or at school before moving to more personalized and detailed questioning and use of screening tools.16

While various screening instruments exist, for the sake of brevity we provide as an example the Screening to Brief Intervention (S2BI) tool. It is an efficient, single-page tool that can help clinicians in their routine care of adolescents to quickly stratify the patient risk of substance use disorder as none/low, moderate, or severe.12 It can be found here: www.mcpap.com/pdf/S2Bi%20Toolkit.pdf (see page 10).

For all patients, but particularly for adolescents, confidentiality is important, and many specialty societies have created language to address this issue.12 Discuss confidentiality with both the adolescent patient and the patient’s caregiver simultaneously, with dialogue that includes: (a) the need to speak with adolescents alone during the office visit, (b) the benefits of confidentiality in the physician–patient relationship, and (c) the need to disclose selected information to keep patients safe.12 Describing the process for required disclosures is essential. Benefits of disclosure include further support for the adolescent patient as well as appropriate parental participation and support for possible referrals.12

Treating AUD

Treatment for AUD should be multifaceted. Screen for comorbid mood disorders, such as generalized anxiety,17,18 social anxiety,18 and depression,19 as well as for insomnia.18 Studies have demonstrated a strong link between insomnia and anxiety, and again between anxiety and AUD.17-19 Finally, screen for adverse childhood events such as trauma, victimization, and abuse.20 Addressing issues discovered in screening allows for more targeted and personalized treatment of AUD.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse categorizes evidence-based treatment into 3 areas: behavioral therapies, family therapies, and medications.21

Continue to: Behavioral therapies

Behavioral therapies can include group therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational enhancement therapy, 12-Step facilitation, and contingency management, in which small rewards or incentives are given for participation in treatment to reinforce positive behaviors.21

Family-based therapies, such as brief strategic family therapy, functional family therapy, and multisystem therapy recognize that adolescents exist in systems of families in communities, and that the patient’s success in treatment may be supported by these relationships.21

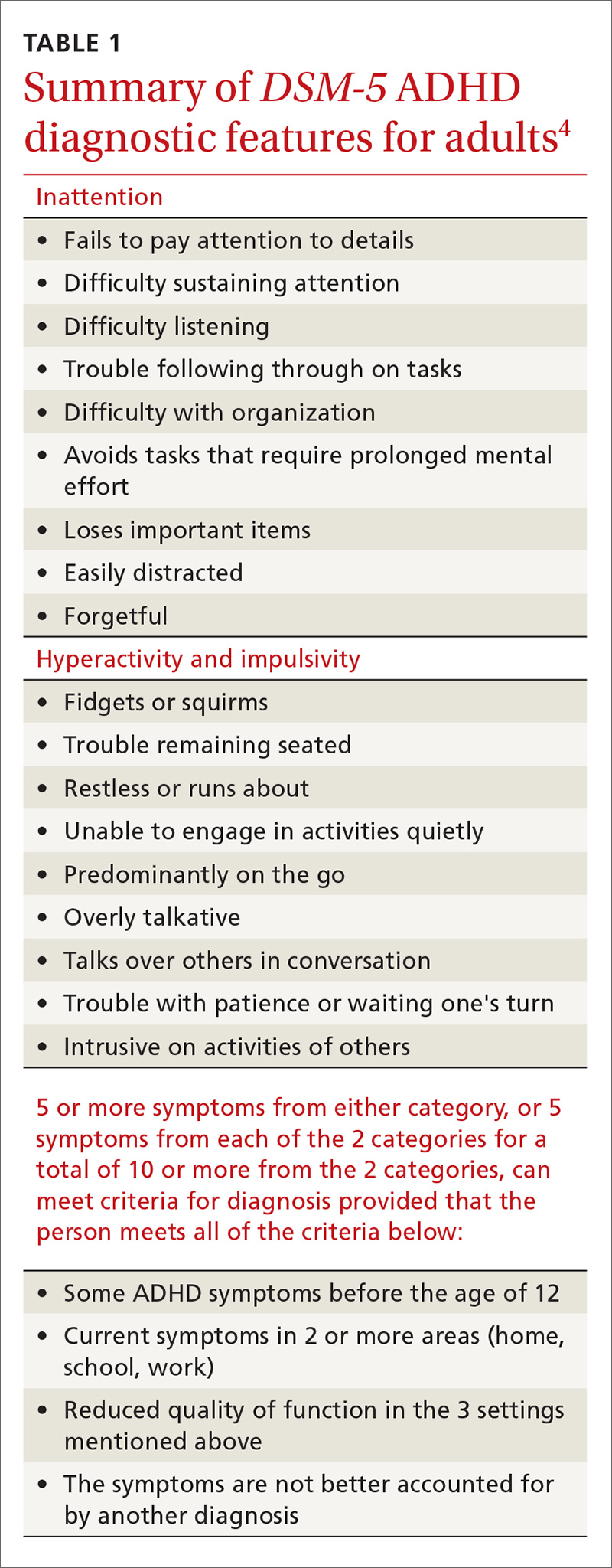

Some medications may achieve modest benefit for treatment of adolescents with AUD. Naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram have all been used successfully to treat AUD in adults21; some physicians may choose to use these medications “off label” in adolescents. Bupropion has been used successfully in the treatment of nicotine use disorder,21 and a small study in 2005 showed some success with bupropion in treating adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, comorbid depression, and substance use disorder.22 Naltrexone has also been studied in adolescents with opioid use disorder, although these were not large studies.23

Adolescents with serious, sustained issues with AUD may require more in-depth treatments such as an intensive outpatient program, a partial hospitalization program, or a residential treatment program.15 The least-restrictive environment is preferable.15 Families are generally included as part of the treatment and recovery process in those settings.21 Some patients may require detoxification prior to referral to residential treatment settings; the American Society of Addiction Medicine has published a comprehensive guideline on alcohol withdrawal.24

Paul’s family physician diagnosed his condition as AUD and referred him for CBT with a psychologist, who treated him for both the AUD and an underlying depressive disorder that was later identified. CBT focused on cognitive restructuring of depressive thoughts as well as support for continued abstinence from alcohol. The patient, with family support, declined antidepressant medication.

After 6 months of treatment, Paul and his parents were pleased with his progress. His grades improved to the point that he was permitted to play soccer again, and he was seriously looking at his future college options.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott A. Fields, PhD, 3200 MacCorkle Avenue Southeast, 5th Floor, Robert C. Byrd Clinical Teaching Center, Department of Family Medicine, Charleston, WV 25304; sfields@hsc.wvu.edu

1. US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking. Washington, DC; US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. 2007.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, DC; US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. 2016.

3. Hingson R, White A. New research findings since the 2007 Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking: A review. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2014; 75:158-169.

4. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Underage drinking. National Institute of Health. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/underage-drinking.

5. Hingson R, Zha W, Iannotti R, et al. Physician advice to adolescents about drinking and other health behaviors. Pediatrics. 2013;131:249-257.

6. Schaus JF, Sole ML, McCoy TP, et al. Screening for high-risk drinking in a college student health center: characterizing students based on quantity, frequency, and harms. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2009;16:34-44.

7. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Drinking levels defined. Accessed December 27, 2021. www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking

8. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Arlington, VA; American Psychiatric Association. 2013.

9. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Bringing down binge drinking. Accessed December 27, 2021. www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/programs_campaigns/nation_prevention_week/data-binge-drinking.pdf

10. Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757-766.

11. USPSTF. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;320:1899-1909.

12. Levy SJ, Williams JF, Committee on Substance Use and Prevention. Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20161211.

13. MacKay AP, Duran CP. Adolescent Health in the United States. National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007.

14. Haller DM, Meynard A, Lefebvre D, et al. Effectiveness of training family physicians to deliver a brief intervention to address excessive substance use among young patients: a cluster randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2014;186:E263-E272.

15. Borus J, Parhami I, Levy S. Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Child Adolesc Psychiatric Clin N Am. 2016;25:579-601.

16. Knight J, Roberts T, Gabrielli J, et al. Adolescent alcohol and substance use and abuse. Performing preventive services: A bright futures handbook. Accessed December 22, 2021. American Academy of Pediatrics. https://ocfcpacourts.us/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Adolescent_Alcohol_and_Substance_Abuse_001005.pdf

17. Dyer ML, Heron J, Hickman M, et al. Alcohol use in late adolescence and early adulthood: the role of generalized anxiety disorder and drinking to cope motives. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;204:107480.

18. Blumenthal H, Taylor DJ, Cloutier RM, et al. The links between social anxiety disorder, insomnia symptoms, and alcohol use disorders: findings from a large sample of adolescents in the United States. Behav Ther. 2019;50:50-59.

19. Pedrelli P, Shapero B, Archibald A, et al. Alcohol use and depression during adolescence and young adulthood: a summary and interpretation of mixed findings. Curr Addict Rep. 2016;3:91-97.

20. Davis JP, Dworkin ER, Helton J, et al. Extending poly-victimization theory: differential effects of adolescents’ experiences of victimization on substance use disorder diagnoses upon treatment entry. Child Abuse Negl. 2019; 89:165-177.

21. NIDA. Principles of adolescent substance use disorder treatment: a research-based guide. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.drugabuse.gov/publications/principles-adolescent-substance-use-disorder-treatment-research-based-guide

22. Solhkhah R, Wilens TE, Daly J, et al. Bupropion SR for the treatment of substance-abusing outpatient adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and mood disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005:15:777-786.

23. Camenga DR, Colon-Rivera HA, Muvvala SB. Medications for maintenance treatment of opioid use disorder in adolescents. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2019;80:393-402.

24. American Society of Addiction Medicine. The ASAM clinical practice guideline on alcohol withdrawal management. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.asam.org/quality-care/clinical-guidelines/alcohol-withdrawal-management-guideline

1. US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking. Washington, DC; US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. 2007.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, DC; US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. 2016.

3. Hingson R, White A. New research findings since the 2007 Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking: A review. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2014; 75:158-169.

4. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Underage drinking. National Institute of Health. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/underage-drinking.

5. Hingson R, Zha W, Iannotti R, et al. Physician advice to adolescents about drinking and other health behaviors. Pediatrics. 2013;131:249-257.

6. Schaus JF, Sole ML, McCoy TP, et al. Screening for high-risk drinking in a college student health center: characterizing students based on quantity, frequency, and harms. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2009;16:34-44.

7. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Drinking levels defined. Accessed December 27, 2021. www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking

8. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Arlington, VA; American Psychiatric Association. 2013.

9. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Bringing down binge drinking. Accessed December 27, 2021. www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/programs_campaigns/nation_prevention_week/data-binge-drinking.pdf

10. Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757-766.

11. USPSTF. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;320:1899-1909.

12. Levy SJ, Williams JF, Committee on Substance Use and Prevention. Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20161211.

13. MacKay AP, Duran CP. Adolescent Health in the United States. National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007.

14. Haller DM, Meynard A, Lefebvre D, et al. Effectiveness of training family physicians to deliver a brief intervention to address excessive substance use among young patients: a cluster randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2014;186:E263-E272.

15. Borus J, Parhami I, Levy S. Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Child Adolesc Psychiatric Clin N Am. 2016;25:579-601.

16. Knight J, Roberts T, Gabrielli J, et al. Adolescent alcohol and substance use and abuse. Performing preventive services: A bright futures handbook. Accessed December 22, 2021. American Academy of Pediatrics. https://ocfcpacourts.us/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Adolescent_Alcohol_and_Substance_Abuse_001005.pdf

17. Dyer ML, Heron J, Hickman M, et al. Alcohol use in late adolescence and early adulthood: the role of generalized anxiety disorder and drinking to cope motives. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;204:107480.

18. Blumenthal H, Taylor DJ, Cloutier RM, et al. The links between social anxiety disorder, insomnia symptoms, and alcohol use disorders: findings from a large sample of adolescents in the United States. Behav Ther. 2019;50:50-59.

19. Pedrelli P, Shapero B, Archibald A, et al. Alcohol use and depression during adolescence and young adulthood: a summary and interpretation of mixed findings. Curr Addict Rep. 2016;3:91-97.

20. Davis JP, Dworkin ER, Helton J, et al. Extending poly-victimization theory: differential effects of adolescents’ experiences of victimization on substance use disorder diagnoses upon treatment entry. Child Abuse Negl. 2019; 89:165-177.

21. NIDA. Principles of adolescent substance use disorder treatment: a research-based guide. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.drugabuse.gov/publications/principles-adolescent-substance-use-disorder-treatment-research-based-guide

22. Solhkhah R, Wilens TE, Daly J, et al. Bupropion SR for the treatment of substance-abusing outpatient adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and mood disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005:15:777-786.

23. Camenga DR, Colon-Rivera HA, Muvvala SB. Medications for maintenance treatment of opioid use disorder in adolescents. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2019;80:393-402.

24. American Society of Addiction Medicine. The ASAM clinical practice guideline on alcohol withdrawal management. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.asam.org/quality-care/clinical-guidelines/alcohol-withdrawal-management-guideline

A practical guide to the management of phobias

THE CASE

Joe S* is a 25-year-old white man who lives with his mother and has a 5-year history of worsening hypertension. He recently presented to the clinic with heart palpitations, shortness of breath, abdominal distress, and dizziness. He said that it was difficult for him to leave his home due to the intense fear he experiences. He said that these symptoms did not occur at home, nor when he visited specific “safe” locations, such as his girlfriend’s apartment. He reported that his fear had increased over the previous 2 years, and that he had progressively limited the distance he traveled from home. He also reported difficulty being in crowds and said, “The idea of going to the movies is torture.”

●

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

The most prevalent psychiatric maladies in primary care are anxiety and mood disorders.1,2 Anxiety disorders are patterns of maladaptive behaviors in conjunction with or response to excessive fear or anxiety.3 The most prevalent anxiety disorder in the United States is specific phobia, the fear of a particular object or situation, with a 12-month prevalence rate of 12.1%.2

Other phobias diagnosed separately in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), include social phobia and agoraphobia, which are, respectively, the fear of being negatively evaluated in social situations and the fear of being trapped in public/open spaces. Social phobia and agoraphobia have diagnostic criteria nearly identical to those of simple phobias regarding the fear response, with the primary differences being the specific phobic situations or stimuli.

Unfortunately, these phobias are likely to be undiagnosed and untreated in primary care partly because patients may not seek treatment.4-6 The ease of avoiding some phobic situations contributes to a lack of treatment seeking.5 Furthermore, commonly used brief measures for psychiatric conditions generally identify depression and anxiety but not phobias. However, family physicians do have resources not only to diagnose these disorders, but also to work with patients to ameliorate them. Collaboration with behavioral health providers is key, as patients with phobias generally benefit from cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), while those with comorbid psychiatric conditions may benefit from a combination of CBT and medication.

Phobic response vs adaptive fear and anxiety

The terms anxiety and fear often overlap when used to describe a negative emotional state of arousal. However, fear is a response to an actual (or perceived) imminent threat, whereas anxiety is the response to a perceived future threat.3 Fear, although unpleasant, serves an adaptive function in responding to immediate danger.7 Anxiety, in turn, may represent an adaptive function for future activities associated with fear. For example, a cave dweller having seen a bear enter a cave in the past (fear-evoking stimulus) may experience anxiety when exploring a different cave (anxiety that a bear may be present). In this situation, the cave dweller’s fear and anxiety responses are important for survival.

Continue to: With phobias...

With phobias, the fear and anxiety responses become maladaptive.3 Specifically, they involve inaccurate beliefs about a specific type of stimulus that could be an object (snake), environment (ocean), or situation (crowded room). Accompanying the maladaptive thoughts are correspondingly exaggerated emotions, physiologic effects, and behavioral responses in alignment with one another.8 The development of this response and the etiology of phobias is complex and is still being debated.7,9,10 Research points to 4 primary pathways: direct psychological conditioning, modeling (watching others), instruction/information, and nonassociative (innate) acquisition.7,10 While the first 3 pathways involve learned responses, the last results from biological predispositions.

DIAGNOSING PHOBIAS: WHAT TO ZERO IN ON

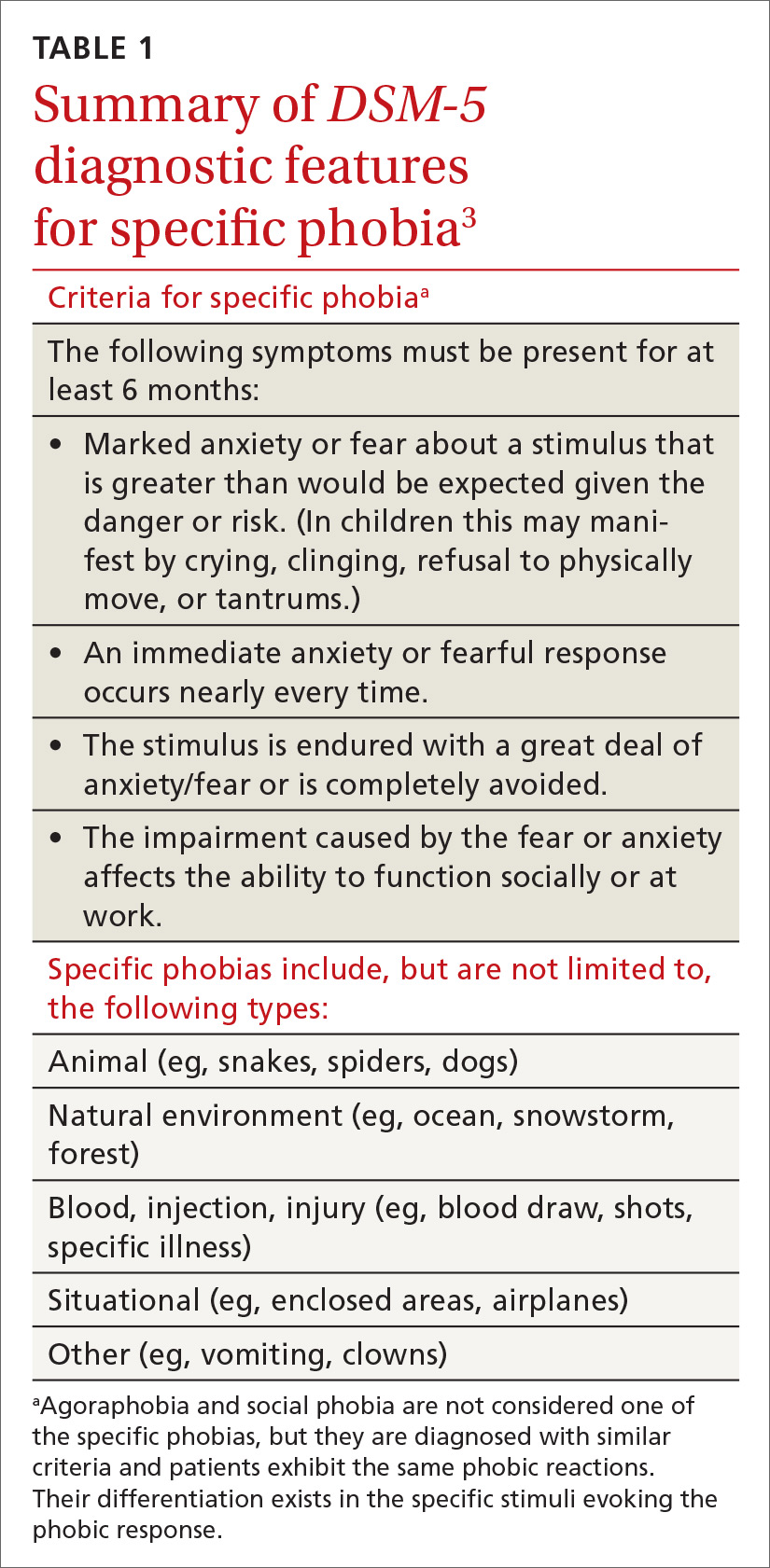

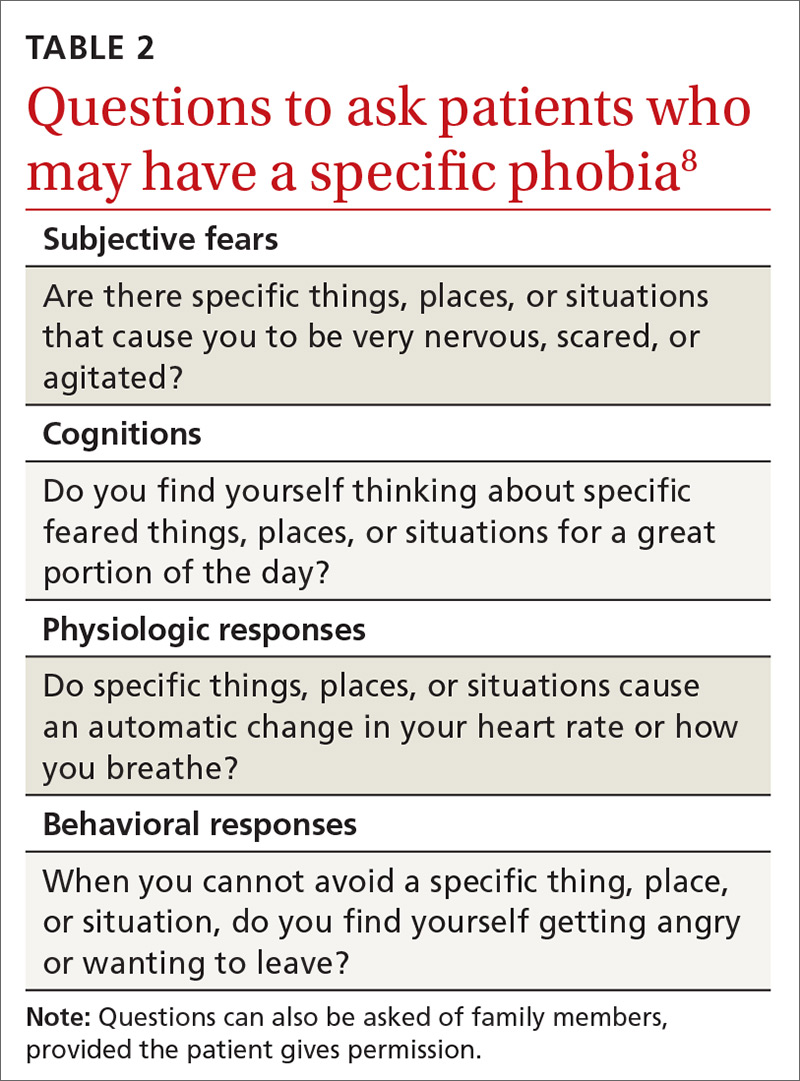

DSM-5 provides diagnostic criteria for specific phobia, agoraphobia, and social phobia, with each diagnosis requiring that symptoms be present for at least 6 months (TABLE 1).3 Diagnosis of phobias should include evaluation of 4 components of a patient’s functioning: subjective fears, cognitions, physiologic responses, and behaviors.8

- Subjective fears: the patient’s described level of distress/agitation to a specific stimulus.

- Cognitions: the patient’s thoughts/beliefs regarding the stimulus.

- Physiologic responses: changes in heart rate, respiration, blood pressure, and other sympathetic nervous system responses with exposure to stimuli.

- Behavioral responses: the most common response is avoidance, with displays of anger, irritability, or apprehension when avoidance of the stimulus is impossible.

Evaluating these 4 components can be accomplished with structured interviews, behavioral observations, or collateral reports from family members or the patient’s peers.8 Thorough questioning and evaluation (TABLE 28) can enable accurate differentiation between phobias unique to specific stimuli and other DSM-5 disorders that might cause similar symptoms. For example, a patient diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) might have a fear response even when triggering stimuli are not present. Identification of a clear, life-threatening incident could help with a differential between phobias and PTSD. However, a patient could be diagnosed with both disorders, as the 2 conditions are not mutually exclusive.

The physiologic and behavioral response symptoms of phobia can also mimic purely medical conditions. Hypertension or tachycardia observed during a medical visit could be due to the fear associated with agoraphobia or with a medically related specific phobia. Blood pressure elevated during testing at the medical appointment could be normal with at-home monitoring by the patient. Thus, blood pressure and heart rate screenings performed at home instead of in public places may help to rule out whether potentially elevated numbers are related to a fear response. Fear and avoidance-like symptoms can also be due to substance abuse, and appropriate drug screening can provide information for an accurate diagnosis.

HOW BEST TO TREAT PHOBIAS

Although research demonstrates that a variety of psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic treatments are efficacious for phobias, in some instances the true utility of an intervention to meaningfully improve a patient’s life is questionable. The issue is that the research evaluating treatment often evaluates only one component of a phobic response (eg,

Continue to: Psychotherapeutic interventions...

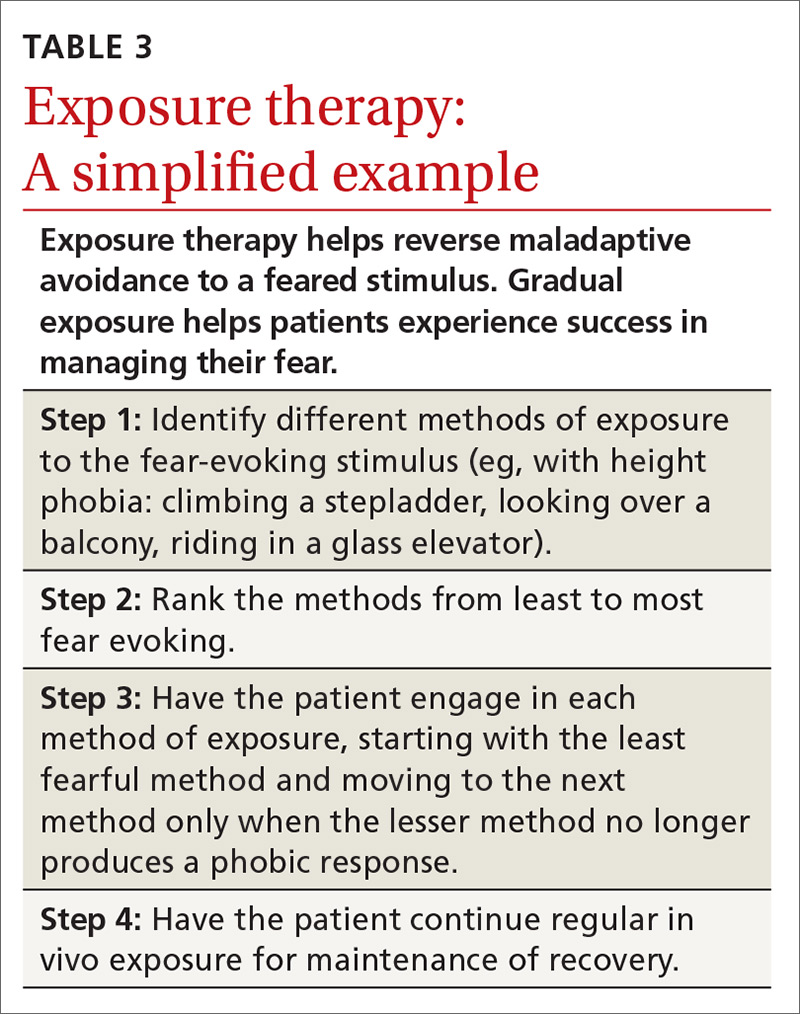

Psychotherapeutic interventions for phobias have shown substantial benefit. CBT is helpful, with the most efficacious technique being exposure therapy.5,6,8,11,12 CBT can begin during the initial primary care visit with the family physician educating the patient about phobias and available treatments.

With exposure therapy, patients are introduced to the source of anxiety over time, whereby they learn to manage the distress

Pharmacologic interventions—specifically selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)—have been effective in treating social phobia and agoraphobia.6 However, treatment of specific phobias via pharmacologic interventions is not supported due to limited efficacy and few studies for SSRIs and SNRIs.5,6

Benzodiazepines, although effective in alleviating some phobic symptoms, are not recommended per current guidelines due to adverse effects and potential exacerbation of the phobic response once discontinued.5,6 This poor result with benzodiazepines may be due to the absence of simultaneous emotional exposure to the feared stimuli. Unfortunately, little research has been done on the long-term effects of pharmacologic intervention once the treatment has been discontinued.11 So, for medication, the question of how long treatment effect lasts after discontinuation remains unanswered.

THE CASE

Mr. S’s family physician diagnosed his condition as agoraphobia with panic attacks. He was prescribed sertraline for his panic attacks and referred for CBT with a psychologist. CBT focused on cognitive restructuring as well as gradual exposure where he would travel with increasing distances to various locations. After 10 months of treatment, Mr. S was able to overcome the agoraphobia and took an “awesome” vacation. He also reported a significant decrease in panic symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott A. Fields, PhD, 3200 MacCorkle Avenue Southeast, 5th Floor, Robert C. Byrd Clinical Teaching Center, Department of Family Medicine, Charleston, WV 25304; sfields@hsc.wvu.edu.

1. Simon G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, et al. Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1995; 152:352-357.

2. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve‐month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012; 21:169-184.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:189-233.

4. Bandelow B, Michaelis S. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders in the 21st century. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2015; 17:327-335.

5. Choy Y, Fyer AJ, Lipsitz JD. Treatment of specific phobia in adults. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007; 27:266-286.

6. Bandelow B, Michaelis S, Wedekind D. Treatment of anxiety disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2017; 19:93-107.

7. Poulton R, Menzies RG. Non-associative fear acquisition: a review of the evidence from retrospective and longitudinal research. Behav Res Ther. 2002; 40:127-149.

8. Davis III TE, Ollendick TH. Empirically supported treatments for specific phobia in children: Do efficacious treatments address the components of a phobic response? Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2005; 12:144-160.

9. Field AP. Is conditioning a useful framework for understanding the development and treatment of phobias? Clin Psychol Rev. 2006; 26:857-875.

10. King NJ, Eleonora G, Ollendick TH. Etiology of childhood phobias: current status of Rachman’s three pathways theory. Behav Res Ther. 1998; 36:297-309.

11. Fedoroff IC, Taylor S. Psychological and pharmacological treatments of social phobia: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001; 21:311-324.

12. Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Horowitz JD, Powers MB, et al. Psychological approaches in the treatment of specific phobias: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008; 28:1021-1037.

13. Zlomke K, Davis III TE. One-session treatment of specific phobias: a detailed description and review of treatment efficacy. Behav Ther. 2008; 39:207-223.

THE CASE

Joe S* is a 25-year-old white man who lives with his mother and has a 5-year history of worsening hypertension. He recently presented to the clinic with heart palpitations, shortness of breath, abdominal distress, and dizziness. He said that it was difficult for him to leave his home due to the intense fear he experiences. He said that these symptoms did not occur at home, nor when he visited specific “safe” locations, such as his girlfriend’s apartment. He reported that his fear had increased over the previous 2 years, and that he had progressively limited the distance he traveled from home. He also reported difficulty being in crowds and said, “The idea of going to the movies is torture.”

●

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

The most prevalent psychiatric maladies in primary care are anxiety and mood disorders.1,2 Anxiety disorders are patterns of maladaptive behaviors in conjunction with or response to excessive fear or anxiety.3 The most prevalent anxiety disorder in the United States is specific phobia, the fear of a particular object or situation, with a 12-month prevalence rate of 12.1%.2

Other phobias diagnosed separately in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), include social phobia and agoraphobia, which are, respectively, the fear of being negatively evaluated in social situations and the fear of being trapped in public/open spaces. Social phobia and agoraphobia have diagnostic criteria nearly identical to those of simple phobias regarding the fear response, with the primary differences being the specific phobic situations or stimuli.

Unfortunately, these phobias are likely to be undiagnosed and untreated in primary care partly because patients may not seek treatment.4-6 The ease of avoiding some phobic situations contributes to a lack of treatment seeking.5 Furthermore, commonly used brief measures for psychiatric conditions generally identify depression and anxiety but not phobias. However, family physicians do have resources not only to diagnose these disorders, but also to work with patients to ameliorate them. Collaboration with behavioral health providers is key, as patients with phobias generally benefit from cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), while those with comorbid psychiatric conditions may benefit from a combination of CBT and medication.

Phobic response vs adaptive fear and anxiety

The terms anxiety and fear often overlap when used to describe a negative emotional state of arousal. However, fear is a response to an actual (or perceived) imminent threat, whereas anxiety is the response to a perceived future threat.3 Fear, although unpleasant, serves an adaptive function in responding to immediate danger.7 Anxiety, in turn, may represent an adaptive function for future activities associated with fear. For example, a cave dweller having seen a bear enter a cave in the past (fear-evoking stimulus) may experience anxiety when exploring a different cave (anxiety that a bear may be present). In this situation, the cave dweller’s fear and anxiety responses are important for survival.

Continue to: With phobias...

With phobias, the fear and anxiety responses become maladaptive.3 Specifically, they involve inaccurate beliefs about a specific type of stimulus that could be an object (snake), environment (ocean), or situation (crowded room). Accompanying the maladaptive thoughts are correspondingly exaggerated emotions, physiologic effects, and behavioral responses in alignment with one another.8 The development of this response and the etiology of phobias is complex and is still being debated.7,9,10 Research points to 4 primary pathways: direct psychological conditioning, modeling (watching others), instruction/information, and nonassociative (innate) acquisition.7,10 While the first 3 pathways involve learned responses, the last results from biological predispositions.

DIAGNOSING PHOBIAS: WHAT TO ZERO IN ON

DSM-5 provides diagnostic criteria for specific phobia, agoraphobia, and social phobia, with each diagnosis requiring that symptoms be present for at least 6 months (TABLE 1).3 Diagnosis of phobias should include evaluation of 4 components of a patient’s functioning: subjective fears, cognitions, physiologic responses, and behaviors.8

- Subjective fears: the patient’s described level of distress/agitation to a specific stimulus.

- Cognitions: the patient’s thoughts/beliefs regarding the stimulus.

- Physiologic responses: changes in heart rate, respiration, blood pressure, and other sympathetic nervous system responses with exposure to stimuli.

- Behavioral responses: the most common response is avoidance, with displays of anger, irritability, or apprehension when avoidance of the stimulus is impossible.

Evaluating these 4 components can be accomplished with structured interviews, behavioral observations, or collateral reports from family members or the patient’s peers.8 Thorough questioning and evaluation (TABLE 28) can enable accurate differentiation between phobias unique to specific stimuli and other DSM-5 disorders that might cause similar symptoms. For example, a patient diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) might have a fear response even when triggering stimuli are not present. Identification of a clear, life-threatening incident could help with a differential between phobias and PTSD. However, a patient could be diagnosed with both disorders, as the 2 conditions are not mutually exclusive.

The physiologic and behavioral response symptoms of phobia can also mimic purely medical conditions. Hypertension or tachycardia observed during a medical visit could be due to the fear associated with agoraphobia or with a medically related specific phobia. Blood pressure elevated during testing at the medical appointment could be normal with at-home monitoring by the patient. Thus, blood pressure and heart rate screenings performed at home instead of in public places may help to rule out whether potentially elevated numbers are related to a fear response. Fear and avoidance-like symptoms can also be due to substance abuse, and appropriate drug screening can provide information for an accurate diagnosis.

HOW BEST TO TREAT PHOBIAS

Although research demonstrates that a variety of psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic treatments are efficacious for phobias, in some instances the true utility of an intervention to meaningfully improve a patient’s life is questionable. The issue is that the research evaluating treatment often evaluates only one component of a phobic response (eg,

Continue to: Psychotherapeutic interventions...

Psychotherapeutic interventions for phobias have shown substantial benefit. CBT is helpful, with the most efficacious technique being exposure therapy.5,6,8,11,12 CBT can begin during the initial primary care visit with the family physician educating the patient about phobias and available treatments.

With exposure therapy, patients are introduced to the source of anxiety over time, whereby they learn to manage the distress

Pharmacologic interventions—specifically selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)—have been effective in treating social phobia and agoraphobia.6 However, treatment of specific phobias via pharmacologic interventions is not supported due to limited efficacy and few studies for SSRIs and SNRIs.5,6

Benzodiazepines, although effective in alleviating some phobic symptoms, are not recommended per current guidelines due to adverse effects and potential exacerbation of the phobic response once discontinued.5,6 This poor result with benzodiazepines may be due to the absence of simultaneous emotional exposure to the feared stimuli. Unfortunately, little research has been done on the long-term effects of pharmacologic intervention once the treatment has been discontinued.11 So, for medication, the question of how long treatment effect lasts after discontinuation remains unanswered.

THE CASE

Mr. S’s family physician diagnosed his condition as agoraphobia with panic attacks. He was prescribed sertraline for his panic attacks and referred for CBT with a psychologist. CBT focused on cognitive restructuring as well as gradual exposure where he would travel with increasing distances to various locations. After 10 months of treatment, Mr. S was able to overcome the agoraphobia and took an “awesome” vacation. He also reported a significant decrease in panic symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott A. Fields, PhD, 3200 MacCorkle Avenue Southeast, 5th Floor, Robert C. Byrd Clinical Teaching Center, Department of Family Medicine, Charleston, WV 25304; sfields@hsc.wvu.edu.

THE CASE

Joe S* is a 25-year-old white man who lives with his mother and has a 5-year history of worsening hypertension. He recently presented to the clinic with heart palpitations, shortness of breath, abdominal distress, and dizziness. He said that it was difficult for him to leave his home due to the intense fear he experiences. He said that these symptoms did not occur at home, nor when he visited specific “safe” locations, such as his girlfriend’s apartment. He reported that his fear had increased over the previous 2 years, and that he had progressively limited the distance he traveled from home. He also reported difficulty being in crowds and said, “The idea of going to the movies is torture.”

●

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

The most prevalent psychiatric maladies in primary care are anxiety and mood disorders.1,2 Anxiety disorders are patterns of maladaptive behaviors in conjunction with or response to excessive fear or anxiety.3 The most prevalent anxiety disorder in the United States is specific phobia, the fear of a particular object or situation, with a 12-month prevalence rate of 12.1%.2

Other phobias diagnosed separately in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), include social phobia and agoraphobia, which are, respectively, the fear of being negatively evaluated in social situations and the fear of being trapped in public/open spaces. Social phobia and agoraphobia have diagnostic criteria nearly identical to those of simple phobias regarding the fear response, with the primary differences being the specific phobic situations or stimuli.

Unfortunately, these phobias are likely to be undiagnosed and untreated in primary care partly because patients may not seek treatment.4-6 The ease of avoiding some phobic situations contributes to a lack of treatment seeking.5 Furthermore, commonly used brief measures for psychiatric conditions generally identify depression and anxiety but not phobias. However, family physicians do have resources not only to diagnose these disorders, but also to work with patients to ameliorate them. Collaboration with behavioral health providers is key, as patients with phobias generally benefit from cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), while those with comorbid psychiatric conditions may benefit from a combination of CBT and medication.

Phobic response vs adaptive fear and anxiety

The terms anxiety and fear often overlap when used to describe a negative emotional state of arousal. However, fear is a response to an actual (or perceived) imminent threat, whereas anxiety is the response to a perceived future threat.3 Fear, although unpleasant, serves an adaptive function in responding to immediate danger.7 Anxiety, in turn, may represent an adaptive function for future activities associated with fear. For example, a cave dweller having seen a bear enter a cave in the past (fear-evoking stimulus) may experience anxiety when exploring a different cave (anxiety that a bear may be present). In this situation, the cave dweller’s fear and anxiety responses are important for survival.

Continue to: With phobias...

With phobias, the fear and anxiety responses become maladaptive.3 Specifically, they involve inaccurate beliefs about a specific type of stimulus that could be an object (snake), environment (ocean), or situation (crowded room). Accompanying the maladaptive thoughts are correspondingly exaggerated emotions, physiologic effects, and behavioral responses in alignment with one another.8 The development of this response and the etiology of phobias is complex and is still being debated.7,9,10 Research points to 4 primary pathways: direct psychological conditioning, modeling (watching others), instruction/information, and nonassociative (innate) acquisition.7,10 While the first 3 pathways involve learned responses, the last results from biological predispositions.

DIAGNOSING PHOBIAS: WHAT TO ZERO IN ON

DSM-5 provides diagnostic criteria for specific phobia, agoraphobia, and social phobia, with each diagnosis requiring that symptoms be present for at least 6 months (TABLE 1).3 Diagnosis of phobias should include evaluation of 4 components of a patient’s functioning: subjective fears, cognitions, physiologic responses, and behaviors.8

- Subjective fears: the patient’s described level of distress/agitation to a specific stimulus.

- Cognitions: the patient’s thoughts/beliefs regarding the stimulus.

- Physiologic responses: changes in heart rate, respiration, blood pressure, and other sympathetic nervous system responses with exposure to stimuli.

- Behavioral responses: the most common response is avoidance, with displays of anger, irritability, or apprehension when avoidance of the stimulus is impossible.

Evaluating these 4 components can be accomplished with structured interviews, behavioral observations, or collateral reports from family members or the patient’s peers.8 Thorough questioning and evaluation (TABLE 28) can enable accurate differentiation between phobias unique to specific stimuli and other DSM-5 disorders that might cause similar symptoms. For example, a patient diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) might have a fear response even when triggering stimuli are not present. Identification of a clear, life-threatening incident could help with a differential between phobias and PTSD. However, a patient could be diagnosed with both disorders, as the 2 conditions are not mutually exclusive.

The physiologic and behavioral response symptoms of phobia can also mimic purely medical conditions. Hypertension or tachycardia observed during a medical visit could be due to the fear associated with agoraphobia or with a medically related specific phobia. Blood pressure elevated during testing at the medical appointment could be normal with at-home monitoring by the patient. Thus, blood pressure and heart rate screenings performed at home instead of in public places may help to rule out whether potentially elevated numbers are related to a fear response. Fear and avoidance-like symptoms can also be due to substance abuse, and appropriate drug screening can provide information for an accurate diagnosis.

HOW BEST TO TREAT PHOBIAS

Although research demonstrates that a variety of psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic treatments are efficacious for phobias, in some instances the true utility of an intervention to meaningfully improve a patient’s life is questionable. The issue is that the research evaluating treatment often evaluates only one component of a phobic response (eg,

Continue to: Psychotherapeutic interventions...

Psychotherapeutic interventions for phobias have shown substantial benefit. CBT is helpful, with the most efficacious technique being exposure therapy.5,6,8,11,12 CBT can begin during the initial primary care visit with the family physician educating the patient about phobias and available treatments.

With exposure therapy, patients are introduced to the source of anxiety over time, whereby they learn to manage the distress

Pharmacologic interventions—specifically selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)—have been effective in treating social phobia and agoraphobia.6 However, treatment of specific phobias via pharmacologic interventions is not supported due to limited efficacy and few studies for SSRIs and SNRIs.5,6

Benzodiazepines, although effective in alleviating some phobic symptoms, are not recommended per current guidelines due to adverse effects and potential exacerbation of the phobic response once discontinued.5,6 This poor result with benzodiazepines may be due to the absence of simultaneous emotional exposure to the feared stimuli. Unfortunately, little research has been done on the long-term effects of pharmacologic intervention once the treatment has been discontinued.11 So, for medication, the question of how long treatment effect lasts after discontinuation remains unanswered.

THE CASE

Mr. S’s family physician diagnosed his condition as agoraphobia with panic attacks. He was prescribed sertraline for his panic attacks and referred for CBT with a psychologist. CBT focused on cognitive restructuring as well as gradual exposure where he would travel with increasing distances to various locations. After 10 months of treatment, Mr. S was able to overcome the agoraphobia and took an “awesome” vacation. He also reported a significant decrease in panic symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott A. Fields, PhD, 3200 MacCorkle Avenue Southeast, 5th Floor, Robert C. Byrd Clinical Teaching Center, Department of Family Medicine, Charleston, WV 25304; sfields@hsc.wvu.edu.

1. Simon G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, et al. Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1995; 152:352-357.

2. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve‐month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012; 21:169-184.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:189-233.

4. Bandelow B, Michaelis S. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders in the 21st century. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2015; 17:327-335.

5. Choy Y, Fyer AJ, Lipsitz JD. Treatment of specific phobia in adults. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007; 27:266-286.

6. Bandelow B, Michaelis S, Wedekind D. Treatment of anxiety disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2017; 19:93-107.

7. Poulton R, Menzies RG. Non-associative fear acquisition: a review of the evidence from retrospective and longitudinal research. Behav Res Ther. 2002; 40:127-149.

8. Davis III TE, Ollendick TH. Empirically supported treatments for specific phobia in children: Do efficacious treatments address the components of a phobic response? Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2005; 12:144-160.

9. Field AP. Is conditioning a useful framework for understanding the development and treatment of phobias? Clin Psychol Rev. 2006; 26:857-875.

10. King NJ, Eleonora G, Ollendick TH. Etiology of childhood phobias: current status of Rachman’s three pathways theory. Behav Res Ther. 1998; 36:297-309.

11. Fedoroff IC, Taylor S. Psychological and pharmacological treatments of social phobia: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001; 21:311-324.

12. Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Horowitz JD, Powers MB, et al. Psychological approaches in the treatment of specific phobias: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008; 28:1021-1037.

13. Zlomke K, Davis III TE. One-session treatment of specific phobias: a detailed description and review of treatment efficacy. Behav Ther. 2008; 39:207-223.

1. Simon G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, et al. Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1995; 152:352-357.

2. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve‐month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012; 21:169-184.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:189-233.

4. Bandelow B, Michaelis S. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders in the 21st century. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2015; 17:327-335.

5. Choy Y, Fyer AJ, Lipsitz JD. Treatment of specific phobia in adults. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007; 27:266-286.

6. Bandelow B, Michaelis S, Wedekind D. Treatment of anxiety disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2017; 19:93-107.

7. Poulton R, Menzies RG. Non-associative fear acquisition: a review of the evidence from retrospective and longitudinal research. Behav Res Ther. 2002; 40:127-149.

8. Davis III TE, Ollendick TH. Empirically supported treatments for specific phobia in children: Do efficacious treatments address the components of a phobic response? Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2005; 12:144-160.

9. Field AP. Is conditioning a useful framework for understanding the development and treatment of phobias? Clin Psychol Rev. 2006; 26:857-875.

10. King NJ, Eleonora G, Ollendick TH. Etiology of childhood phobias: current status of Rachman’s three pathways theory. Behav Res Ther. 1998; 36:297-309.

11. Fedoroff IC, Taylor S. Psychological and pharmacological treatments of social phobia: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001; 21:311-324.

12. Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Horowitz JD, Powers MB, et al. Psychological approaches in the treatment of specific phobias: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008; 28:1021-1037.

13. Zlomke K, Davis III TE. One-session treatment of specific phobias: a detailed description and review of treatment efficacy. Behav Ther. 2008; 39:207-223.

How to treat complicated grief

THE CASE

Al* is a 48-year-old patient whose wife, Vera, died of complications from chronic illness 14 months ago. Al thinks about Vera constantly and says he still has difficulty accepting that she is gone. He does not leave the house much anymore and continues to set a place for her at the kitchen table on special occasions. He says, “Some nights in bed, I swear I can hear her in the living room.”

How would you proceed with this patient?

* The names of the patient and his spouse have been changed to protect their identities.

After the loss of a loved one, grief is a natural response to the separation and stress that go along with the death. Most people, after suffering a loss, experience distress that varies in intensity and gradually decreases over time. Thus, the grieving individual does not act as they would normally if they were not bereaved. However, gains are generally made month by month, and most people adjust to the grief and adapt their lives after some time dealing with the absence of the loved one.1

There’s grief, and then there’s complicated grief

For about 2% to 4% of the population who have experienced a significant loss, complicated grief is an issue.2 As its hallmark, complicated grief exceeds the typical amount of time (6-12 months) that people need to recover from a loss. Prevalence has been estimated at 10% to 20% among grieving individuals for whom the death being grieved was that of a romantic partner or child.2 At increased risk for this disorder are women older than 60 years, patients diagnosed with depression or substance abuse, individuals under financial strain, and those who have experienced a violent or sudden loss.3

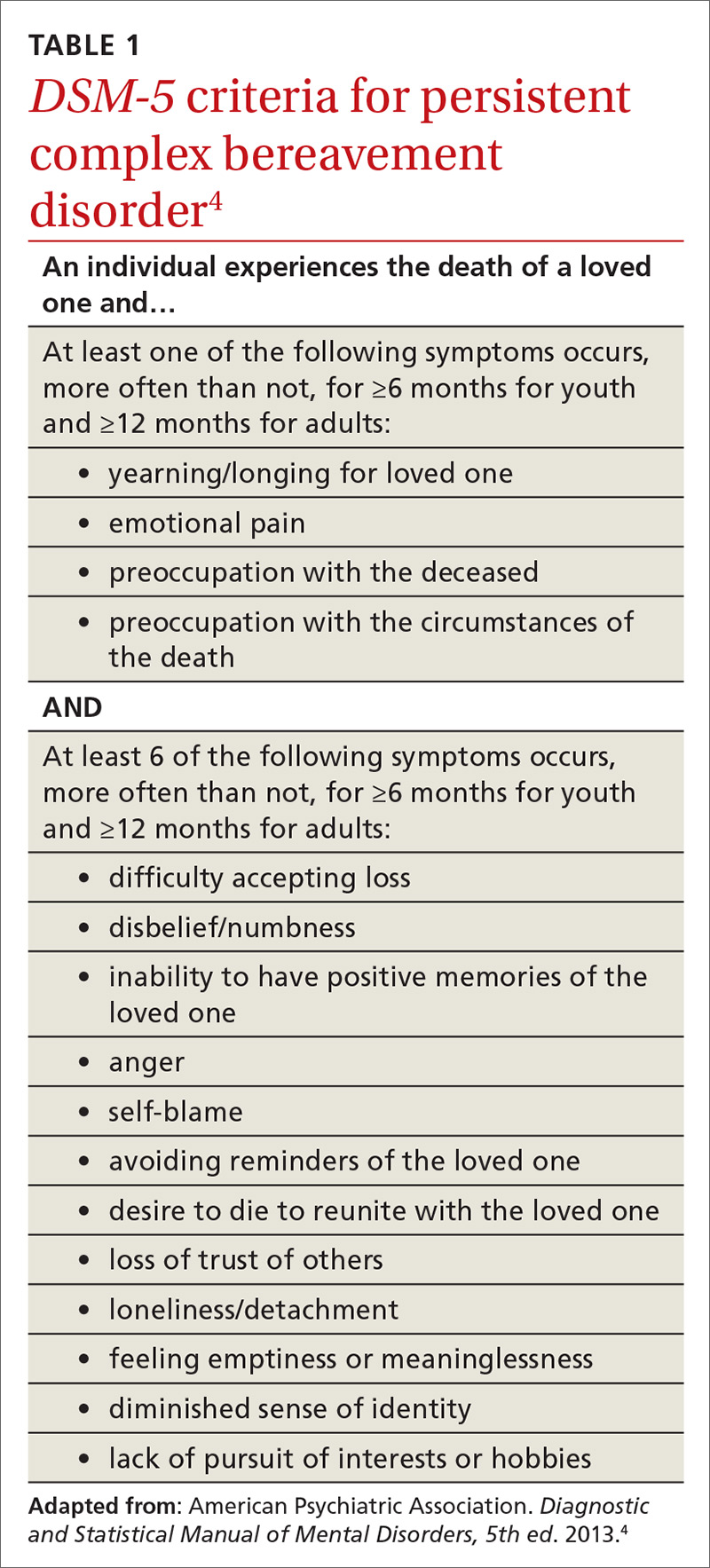

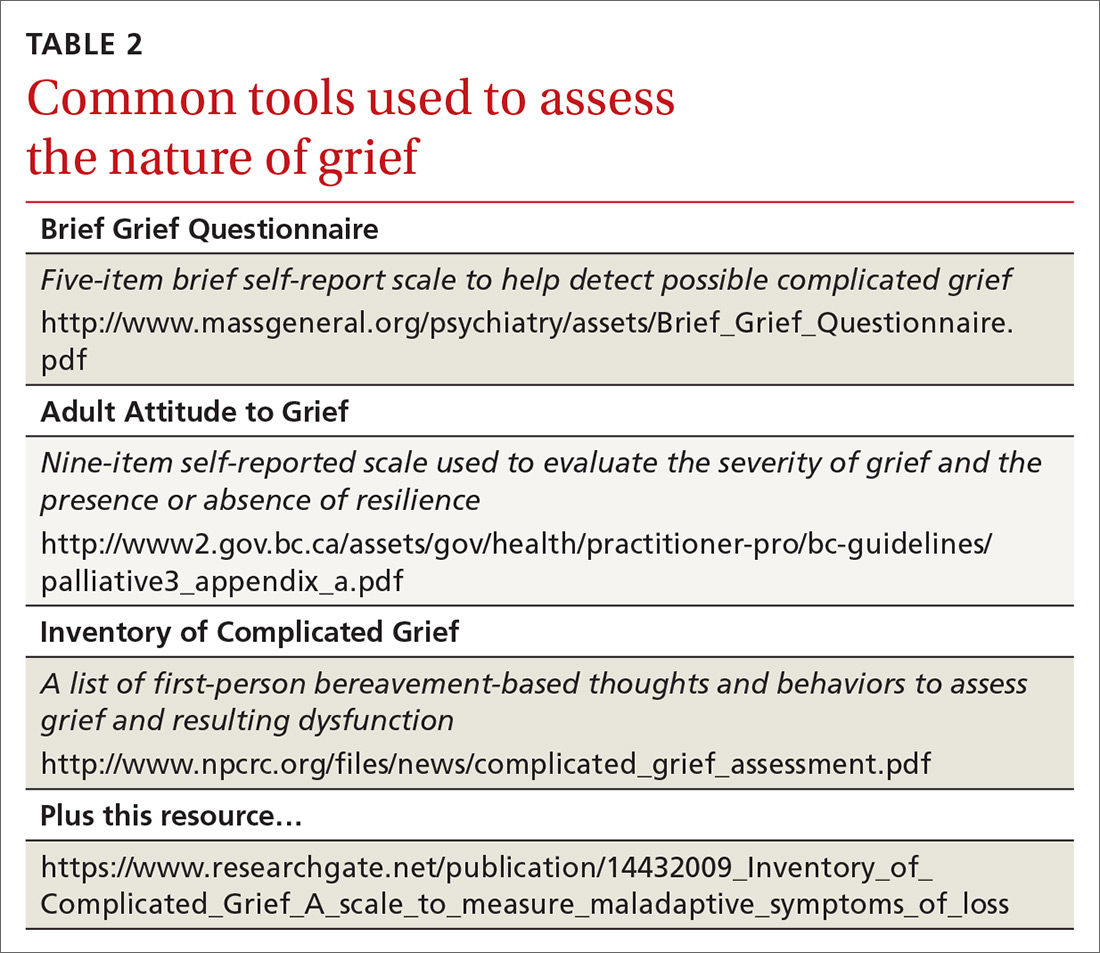

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) has conceptualized complicated grief with the name, persistent complex bereavement disorder (PCBD).4 While the guidelines for the definition are still in progress, several specified symptoms must have been present for at least 6 months to a year or more (TABLE 14). For instance, the patient has been ruminating about the death, has been unable to accept the death, or has felt shocked or numb. They may also experience anger, have difficulty trusting others, and be preoccupied with the deceased (eg, sense they can hear their lost loved one, feel the loved one’s pain for them). Symptoms of PCBD may also include experiencing vivid reminders of the loss and avoiding situations that bring up thoughts about the death.4 (Of note: A grief diagnosis in ICD-10 is captured by the code F43.21; however, there is no specific code for complicated grief or PCBD.)

PCBD is a “condition for further study” in DSM-5; it was omitted from DSM-IV only after much debate. One reason for its omission was concern that clinicians might “pathologize” grief more than it needs to be.5 Grief is regarded as a natural process that might be stymied by a formal diagnosis leading to medical treatment.

Shifting the grief diagnosis paradigm

One new development is that recently bereaved patients can be diagnosed with depression if they meet the criteria for that diagnosis. In the past, someone who met criteria for major depression would be excluded from that diagnosis if the depression ensued from grief. DSM-5 no longer makes that distinction.4 Given this diagnostic shift, one might wonder about the difference between PCBD and depression, particularly if the patient is a grieving individual with a current diagnosis of depression.5

Continue to: Differences between PCBD and major depression

Differences between PCBD and major depression. While antidepressant medication is helpful for patients with moderate-to-severe depression, it has thus far been less helpful for those solely experiencing complicated grief.6 The same holds true for traditional psychotherapy. While family physicians can confidently refer people to psychotherapy for depression, it is not as efficacious as focused therapy designed for those with PCBD.6