User login

Poorer Arthroscopic Outcomes of Mild Dysplasia With Cam Femoroacetabular Impingement Versus Mixed Femoroacetabular Impingement in Absence of Capsular Repair

Take-Home Points

- Cam deformity often occurs with dysplasia.

- Borderline or mild dysplasia has been treated with isolated hip arthroscopy.

- Avoid rim trimming that can make mild dysplasia more severe.

- Labral preservation, cam decompression, and capsular repair or plication are currently suggested.

- Poorer outcomes occurred in borderline or mild dysplasia with cam impingement relative to controls following hip arthroscopy without capsular repair.

- Initial clinical improvement may be followed by clinical deterioration suggesting close long-term follow-up with prompt addition of reorientation acetabular osteotomy if indicated.

- It is unknown whether small capsulotomies may yield comparable outcomes with larger capsulotomies plus repair.

It is unknown whether small capsulotomies may yield comparable outcomes with larger capsulotomies plus repair. There is growing interest in hip preservation surgery in general and arthroscopic hip preservation in particular. Chondrolabral pathology leading to symptoms and degenerative progression typically is caused by structural abnormalities, mainly femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) and developmental dysplasia of the hip. Unlike the bony overcoverage of pincer FAI, developmental dysplasia of the hip typically exhibits insufficient anterolateral coverage of the femoral head.

The role of hip arthroscopy in the treatment of dysplasia remains undefined. Emerging evidence shows a high incidence of dysplasia with associated cam deformity,1,2 but there is a paucity of evidence-based information for this specific patient population. Clinical outcomes of hip arthroscopy in the setting of dysplasia are conflicting: some poor3-5 and others successful.1,6-9 Although reorientation periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) is considered a mainstay in the treatment of dysplasia—providing improvement in symptoms, deficient anterolateral acetabular coverage, and hip biomechanics—midterm failure rates approaching 24% have been reported.10-12 Many young patients with symptomatic dysplasia want a surgical option that is less invasive than open PAO.4 Intra-articular central compartment pathology and cam FAI commonly occur with dysplasia and are amenable to arthroscopic treatment.1,13,14 Moreover, staged PAO may be successful in cases in which arthroscopic intervention fails to provide clinical improvement.5,15

Emerging evidence suggests beneficial effects of arthroscopic capsular repair or plication in the setting of borderline or mild dysplasia.7,9 However, the literature provides little information on arthroscopic outcomes without capsular repair. One study found poor outcomes of arthroscopic surgery for dysplasia, but its patients underwent labral débridement, not repair.3 Two patients in a case report demonstrated rapidly progressive osteoarthritis after arthroscopic labral repairs and concurrent femoroplasties for cam FAI, but each had marked dysplasia with a lateral center-edge angle (LCEA) of <15°.4

Arthroscopy with capsular repair has been assumed to provide better outcomes than arthroscopy without repair, but to our knowledge there are no studies that have compared outcomes of mild dysplasia with cam FAI and outcomes of mixed FAI treated without capsular repair. Clinical equipoise makes it ethically challenging to perform a prospective study comparing dysplasia treated with and without capsular repair. We conducted a study to compare outcomes of mild dysplasia with cam FAI and outcomes of mixed FAI treated with arthroscopic surgery and to fill the knowledge gap regarding outcomes of mild dysplasia treated without capsular repair.

Methods

In this study, which received Institutional Review Board approval, we retrospectively reviewed radiographs and data from a prospective 3-center study of arthroscopic outcomes of FAI in 150 patients (159 hips) who underwent arthroscopic surgery by 1 of 3 surgeons between March 2009 and June 2010. In all cases, digital images of anteroposterior pelvic radiographs were used for radiographic measurements. On these images, the LCEA is formed by the intersection of the vertical line (corrected for obliquity using a horizontal reference line connecting the inferior extents of both radiographic teardrops) through the center of the femoral head (determined with a digital centering tool) with the line extending to the lateral edge of the sourcil (radiographic eyebrow of the weight-bearing region or roof of the acetabulum). Measurements were made in blinded fashion (by a nonsurgeon coauthor, Dr. Nikhil Gupta, who completed training modules) and were confirmed without alteration by the principal investigator Dr. Dean K. Matsuda. Inclusion criteria were mild acetabular dysplasia (LCEA, 15°-24°) and mixed FAI including focal pincer component (LCEA, 25°-39°), radiographic crossover sign, and successful completion of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures at minimum 2-year follow-up. Exclusion criteria were severe dysplasia (LCEA, <15°), hip subluxation, broken Shenton line, global pincer FAI (LCEA, ≥40°), Tönnis grade 3 osteoarthritis, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, osteonecrosis, prior hip surgery, and unsuccessful completion of PRO measures. Outcome measures included investigator-blinded preoperative and postoperative Nonarthritic Hip Score (NAHS) and 5-point Likert satisfaction score. Complications, revision surgeries, and conversion arthroplasties were recorded.

Statistical Analysis

We examined outcomes with descriptive statistics for each of the candidate covariates in the model classified by femoroacetabular subtype: focal pincer and cam (mixed FAI) and dysplasia with cam. We examined the variables of sex, age, weight, height, body mass index, preoperative NAHS, presence of dysplasia (yes/no), presence of osteoarthritis (yes/no), Tönnis osteoarthritis grade, Outerbridge class, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, months of pain, bilateral procedure (yes/no), and pincer involvement with cam FAI (yes/no). Before beginning linear regression modeling, we screened the candidate variables for strong correlations with other variables and looked for those variables with minimal missing data. For all these covariates, we then performed linear regression with a selection process—both a stepwise selection method and a backward elimination method—to verify we determined the same model for 24-month NAHS, or to understand why we could not. Finally, we ran the model we found from the linear regression as a linear mixed model of 24-month NAHS with the dichotomous variables taken as fixed effects and the other variables taken as random effects, using variance-components representation for the random effects. We then examined 3-month and 12-month NAHS with the same variables selected for the 24-month model.

To further examine and verify the effects of dysplasia on outcomes found in our linear mixed model, we performed a nested case–control analysis matching each member of cohort D (cases) with 2 members of cohort M (controls). We used an optimal-matching algorithm to match focal patients in the linear regression dataset with dysplasia patients in the linear regression dataset in such a way as to minimize the overall differences between the datasets. We matched cases and controls on preoperative NAHS, age, sex, presence of osteoarthritis, months of pain, ASA score, and body mass index. The differences between the matched cases and controls (control value minus case value) were compared using Wilcoxon rank sum tests for statistical significance of differences from 0 (with differences generated for each control group member, 2 differences per case) to examine the quality of the match. Finally, we examined the statistical significance of the difference of the outcome variables (3-, 12-, and 24-month NAHS) from 0, again using Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Statistical significance was set at P < .05 using SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute).

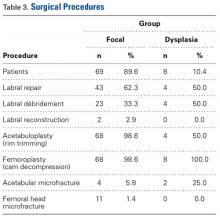

Surgical Procedure

In all cases, supine outpatient hip arthroscopy was performed under general anesthesia. Anterolateral and modified midanterior portals16 were used. T-capsulotomies were performed in both cohorts. Cohort M underwent anterosuperior acetabuloplasty with a motorized burr. Labral refixation or selective débridement was performed in cohort M, whereas labral repair (with limited freshening of acetabular rim attachment site) or selective débridement (but no segmental resection) was performed in cohort D. Arthroscopic femoroplasty was performed with similar endpoints of 120° minimum hip flexion and 30° minimum flexed hip internal rotation with retention of the labral fluid seal. Capsular repair or plication was not performed for either cohort during the study period.

The cohorts underwent similar postoperative protocols: 2 weeks of protected ambulation using 2 crutches, exercise cycling without resistance beginning postoperative day 1, swimming at 2 weeks, elliptical machine workouts at 6 weeks, jogging at 12 weeks, and return to unrestricted athletics at 5 months.

Results

In cohort D, which consisted of 8 patients (5 female), mean age was 49.6 years, and mean LCEA was 19° (range, 16°-24°).

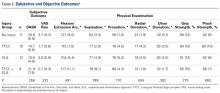

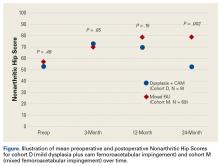

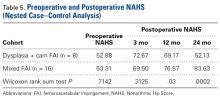

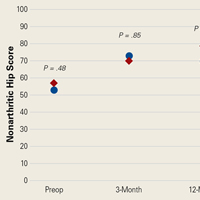

In cohort D, mean (SD) change in NAHS was +20.00 (6.24) (P = .25) at 3 months (n = 3), +14.33 (9.77) (P = .03) at 12 months (n = 6), and –0.75 (19.86) (P = .74) at 24 months (n = 8).

In cohort M, mean (SD) change in NAHS was +12.09 (18.98) (P < .0001) at 3 months (n = 45), +20.39 (16.49) (P < .0001) at 12 months (n = 57), and +21.99 (17.32) (P < .0001) at 24 months (n = 69).

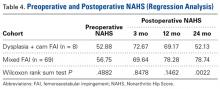

In a pairwise case–control comparison, the mean (SD) change-from-baseline difference between cohorts D and M was +8.2 (12.85) (P = .31) at 3 months (n = 5), –8.7 (11.52) (P = .03) at 12 months (n = 10), and –31.06 (23.55) (P = .0002) at 24 months (n = 16). Dysplasia had an impact of –23.4 points on 24-month NAHS (standard error = 5.35 points; P < .0001), which corresponds to a 95% confidence interval of –12.9 to –33.9 points on NAHS.

Compared with cohort M, cohort D had significantly less NAHS improvement (P = .002), less satisfaction (P = .15) and more hip arthroplasty conversions (P = .22, not statistically significant).

There were no statistically significant differences between cohorts in demographics, preoperative variables, intraoperative findings, or surgical procedures in the regression analysis. Of the investigated variables, only group membership (cohort D) was a statistically significant predictor of poorer outcomes in the model of change from preoperative to 24 months. However, older age was associated with cohort D (older patients with dysplasia, P = .07), and therefore in the nested case–control analysis we were able to match on all variables except age (8.74 years older in cohort D, P = .0013) to a level of statistical nonsignificance.

Discussion

The principal finding of this study is the significantly poorer outcomes of mild dysplasia and cam FAI relative to mixed FAI after hip arthroscopy without capsular repair. Study group (cohort D) and control group (cohort M) had associated cam deformities treated with femoroplasty with similar decompression endpoints and labral preservation in the form of selective débridement or labral repair (no labral resections in either cohort) with similar rehabilitation protocols.

Our study findings suggest short-term improvement may be followed by midterm worsening in patients with mild dysplasia and sustained improvement in patients with mixed FAI. These findings have practical clinical applications. Jackson and colleagues5 reported on a patient who, after undergoing “successful” arthroscopic surgery for mild dysplasia, clinically deteriorated after 13 months and eventually required PAO. Patients undergoing isolated hip arthroscopy for mild dysplasia with cam FAI should be informed of the possible need for secondary PAO or even hip arthroplasty, be followed up more often and longer than comparable patients with FAI, and have follow-up supplemented with interval radiographs.4 If even subtle subluxation or joint narrowing occurs, we suggest resumption of protected weight-bearing and prompt progression to PAO in younger patients with joint congruency or eventual conversion arthroplasty in older ones.

Although mean preoperative NAHS (52.88) and mean 24-month postoperative NAHS (52.13) suggest essentially no change in PROs for cohort D, all patients with dysplasia either worsened or improved, though those who improved did so at a lesser relative magnitude than those with mixed FAI (cohort M). This finding may help explain the divergent outcomes reported in the literature on dysplasia treated with hip arthroscopy.

Cohort D was older than cohort M, but the difference was not statistically significant. Age may still be a confounding variable, and it may have contributed in part to the poorer outcomes for the patients with dysplasia. However, emerging studies demonstrate select older patients with FAI and/or labral tears may have successful outcomes with arthroscopic intervention.17,18 Our findings support mild dysplasia as the main contributor to the poor outcomes observed in this study.

With identical postoperative rehabilitation protocols, patients in both cohorts typically were ambulating without crutches by the end of postoperative week 2. Delayed weight-bearing has been suggested as contributing to successful outcomes in the setting of dysplasia7,19,20 but has not been shown to adversely affect nondysplastic hips.21 Whether delayed weight-bearing contributed to the poor outcomes in our dysplasia cohort is unknown, but the early successful outcomes may discount its influence.

Our findings support successful outcomes of arthroscopic treatment of mixed FAI (specifically focal pincer plus cam FAI) without capsular repair. Perhaps more important, we found inferior outcomes of arthroscopic treatment of mild dysplasia plus cam FAI without capsular repair—filling the knowledge gap regarding the need for arthroscopic capsular repair for mild dysplasia. Although a recent study demonstrated no significant difference in outcomes between hip arthroscopy with and without capsular repair,22 2 studies specific to mild dysplasia demonstrated successful outcomes of capsular repair.7,9 One found that mild dysplasia treated with arthroscopy, including capsular plication, resulted in 77% good/excellent outcomes and LCEA as low as 18° at minimum 2-year follow-up.7 The other found clinical improvement in mild dysplasia (LCEA, 15°-19°) when capsular repair was performed as part of arthroscopic treatment.9 In the present study, we retrospectively reviewed outcomes from a prospective study performed in 2009 to 2010, before the era of common capsular repair. It appears that capsular repair9 or plication7 in the setting of mild dysplasia may yield improved outcomes approaching those of arthroscopic FAI surgery. Our study results showed that, despite labral preservation and cam decompression, mild dysplasia without the closure of T-capsulotomy had inferior outcomes at 2 years. However, we do not know if outcomes would have been better with capsular repair or plication and/or smaller capsulotomies, perhaps with minimal violation of the iliofemoral ligament in this specific subset of patients. Furthermore, we do not know if optimal outcomes can best be achieved with arthroscopic and/or open surgery, with or without acetabular reorientation, in patients with mild dysplasia and cam FAI.

Dysplasia with cam FAI is an emerging common condition for which patients may seek less invasive treatment in the form of hip arthroscopy. The findings of this study suggest caution in using hip arthroscopy without capsular repair in the treatment of mild dysplasia with cam FAI, even in the presence of cam decompression and labral and acetabular rim preservation.

Study Strengths and Limitations

One strength was the relative lack of surgeon bias. When the surgeries were performed (2009-2010), we recognized cam and pincer FAI but did not discriminate for mild dysplasia, because at that time it was not known to be a potential predictor of poorer outcomes. Another strength was the strict methodology, with blinding of all investigator surgeons to PROs and stringent retention of all PROs, including “failures” (eg, total hip arthroplasty conversions and complications), in both cohorts. Moreover, the crucial case-control analysis matched on multiple variables verified statistically significant results demonstrating poorer outcomes at minimum 2-year follow-up, despite more improvement in the dysplasia cohort at 3 months. The latter, we think, is also valuable new information; it emphasizes the need for close and prolonged follow-up of patients with mild dysplasia despite early improvement.

Limitations include the small number of study patients, the retrospective study design (using prospectively collected data), and the isolated use of LCEA to define dysplasia. Pereira and colleagues23 recommended using LCEA with Tönnis angle to define minor dysplasia. Although dysplasia cannot be precisely defined with only this radiographic measurement, LCEA has been shown to be a reliable, clinically relevant measure.24 In addition, LCEA has been used in most reports on arthroscopic management of dysplastic hips and thus allows for comparison. Furthermore, other studies have used LCEA of <15° as a threshold between mild and severe dysplasia, and we did as well. This broad inclusion criterion allowed for heterogeneity in our mild dysplasia cohort and was a study limitation. Interobserver reliability of measured LCEA was not assessed and is another limitation.

The initial prospective study (2009) did not record α angles to quantify cam FAI. This is a study limitation. However, the surgical range-of-motion endpoints considered sufficient for cam decompression were the same in both cohorts. In addition, femoral version was not assessed in the original database (2009-2010), as this aspect of hip anatomy was not thought significant during initial data collection. These areas of interest merit further investigation.

Use of a focal pincer cohort may be challenged as a suboptimal control group. However, there were very few completely normal acetabulae with pure cam FAI in the original prospective study, and the focal pincer cohort was used as a control cohort in previous studies.25

Conclusion

The common combination of mild dysplasia and cam FAI has poorer outcomes than mixed FAI after arthroscopic surgery without capsular repair.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):E47-E53. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Paliobeis CP, Villar RN. The prevalence of dysplasia in femoroacetabular impingement. Hip Int. 2011;21(2):141-145.

2. Clohisy JC, Nunley RM, Carlisle JC, Schoenecker PL. Incidence and characteristics of femoral deformities in the dysplastic hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(1):128-134.

3. Parvizi J, Bican O, Bender B, et al. Arthroscopy for labral tears in patients with developmental dysplasia of the hip: a cautionary note. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(6 suppl):110-113.

4. Matsuda DK, Khatod M. Rapidly progressive osteoarthritis after arthroscopic labral repair in patients with hip dysplasia. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(11):1738-1743.

5. Jackson TJ, Watson J, LaReau JM, Domb BG. Periacetabular osteotomy and arthroscopic labral repair after failed hip arthroscopy due to iatrogenic aggravation of hip dysplasia. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(4):911-914.

6. Byrd JW, Jones KS. Hip arthroscopy in the presence of dysplasia. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(10):1055-1060.

7. Domb BG, Stake CE, Lindner D, El-Bitar Y, Jackson TJ. Arthroscopic capsular plication and labral preservation in borderline hip dysplasia: two-year clinical outcomes of a surgical approach to a challenging problem. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(11):2591-2598.

8. Jayasekera N, Aprato A, Villar RN. Hip arthroscopy in the presence of acetabular dysplasia. Open Orthop J. 2015;9:185-187.

9. Fukui K, Briggs KK, Trindade CA, Philippon MJ. Outcomes after labral repair in patients with femoroacetabular impingement and borderline dysplasia. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(12):2371-2379.

10. Siebenrock KA, Leunig M, Ganz R. Periacetabular osteotomy: the Bernese experience. Instr Course Lect. 2001;50:239-245.

11. Garras DN, Crowder TT, Olson SA. Medium-term results of the Bernese periacetabular osteotomy in the treatment of symptomatic developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(6):721-724.

12. Biedermann R, Donnan L, Gabriel A, Wachter R, Krismer M, Behensky H. Complications and patient satisfaction after periacetabular pelvic osteotomy. Int Orthop. 2008;32(5):611-617.

13. Ross JR, Zaltz I, Nepple JJ, Schoenecker PL, Clohisy JC. Arthroscopic disease classification and interventions as an adjunct in the treatment of acetabular dysplasia. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(suppl):72S-78S.

14. Domb BG, LaReau JM, Baydoun H, Botser I, Millis MB, Yen YM. Is intraarticular pathology common in patients with hip dysplasia undergoing periacetabular osteotomy? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(2):674-680.

15. Kain MS, Novais EN, Vallim C, Millis MB, Kim YJ. Periacetabular osteotomy after failed hip arthroscopy for labral tears in patients with acetabular dysplasia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(suppl 2):57-61.

16. Matsuda DK, Villamor A. The modified mid-anterior portal for hip arthroscopy. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3(4):e469-e474.

17. Javed A, O’Donnell JM. Arthroscopic femoral osteochondroplasty for cam femoroacetabular impingement in patients over 60 years of age. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(3):326-331.

18. Redmond JM, Gupta A, Cregar WM, Hammarstedt JE, Gui C, Domb BG. Arthroscopic treatment of labral tears in patients aged 60 years or older. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(10):1921-1927.

19. Mei-Dan O, McConkey MO, Brick M. Catastrophic failure of hip arthroscopy due to iatrogenic instability: can partial division of the ligamentum teres and iliofemoral ligament cause subluxation? Arthroscopy. 2012;28(3):440-445.

20. Benali Y, Katthagen BD. Hip subluxation as a complication of arthroscopic debridement. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(4):405-407.

21. Jayasekera N, Aprato A, Villar RN. Are crutches required after hip arthroscopy? A case–control study. Hip Int. 2013;23(3):269-273.

22. Domb BG, Stake CE, Finley ZJ, Chen T, Giordano BD. Influence of capsular repair versus unrepaired capsulotomy on 2-year clinical outcomes after arthroscopic hip preservation surgery. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(4):643-650.

23. Pereira F, Giles A, Wood G, Board TN. Recognition of minor adult hip dysplasia: which anatomical indices are important? Hip Int. 2014;24(2):175-179.

24. Murphy SB, Ganz R, Müller ME. The prognosis in untreated dysplasia of the hip. A study of radiographic factors that predict the outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(7):985-989.

25. Matsuda DK, Gupta N, Burchette R, Sehgal B. Arthroscopic surgery for global versus focal pincer femoroacetabular impingement: are the outcomes different? J Hip Preserv Surg. 2015;2(1):42-50.

Take-Home Points

- Cam deformity often occurs with dysplasia.

- Borderline or mild dysplasia has been treated with isolated hip arthroscopy.

- Avoid rim trimming that can make mild dysplasia more severe.

- Labral preservation, cam decompression, and capsular repair or plication are currently suggested.

- Poorer outcomes occurred in borderline or mild dysplasia with cam impingement relative to controls following hip arthroscopy without capsular repair.

- Initial clinical improvement may be followed by clinical deterioration suggesting close long-term follow-up with prompt addition of reorientation acetabular osteotomy if indicated.

- It is unknown whether small capsulotomies may yield comparable outcomes with larger capsulotomies plus repair.

It is unknown whether small capsulotomies may yield comparable outcomes with larger capsulotomies plus repair. There is growing interest in hip preservation surgery in general and arthroscopic hip preservation in particular. Chondrolabral pathology leading to symptoms and degenerative progression typically is caused by structural abnormalities, mainly femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) and developmental dysplasia of the hip. Unlike the bony overcoverage of pincer FAI, developmental dysplasia of the hip typically exhibits insufficient anterolateral coverage of the femoral head.

The role of hip arthroscopy in the treatment of dysplasia remains undefined. Emerging evidence shows a high incidence of dysplasia with associated cam deformity,1,2 but there is a paucity of evidence-based information for this specific patient population. Clinical outcomes of hip arthroscopy in the setting of dysplasia are conflicting: some poor3-5 and others successful.1,6-9 Although reorientation periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) is considered a mainstay in the treatment of dysplasia—providing improvement in symptoms, deficient anterolateral acetabular coverage, and hip biomechanics—midterm failure rates approaching 24% have been reported.10-12 Many young patients with symptomatic dysplasia want a surgical option that is less invasive than open PAO.4 Intra-articular central compartment pathology and cam FAI commonly occur with dysplasia and are amenable to arthroscopic treatment.1,13,14 Moreover, staged PAO may be successful in cases in which arthroscopic intervention fails to provide clinical improvement.5,15

Emerging evidence suggests beneficial effects of arthroscopic capsular repair or plication in the setting of borderline or mild dysplasia.7,9 However, the literature provides little information on arthroscopic outcomes without capsular repair. One study found poor outcomes of arthroscopic surgery for dysplasia, but its patients underwent labral débridement, not repair.3 Two patients in a case report demonstrated rapidly progressive osteoarthritis after arthroscopic labral repairs and concurrent femoroplasties for cam FAI, but each had marked dysplasia with a lateral center-edge angle (LCEA) of <15°.4

Arthroscopy with capsular repair has been assumed to provide better outcomes than arthroscopy without repair, but to our knowledge there are no studies that have compared outcomes of mild dysplasia with cam FAI and outcomes of mixed FAI treated without capsular repair. Clinical equipoise makes it ethically challenging to perform a prospective study comparing dysplasia treated with and without capsular repair. We conducted a study to compare outcomes of mild dysplasia with cam FAI and outcomes of mixed FAI treated with arthroscopic surgery and to fill the knowledge gap regarding outcomes of mild dysplasia treated without capsular repair.

Methods

In this study, which received Institutional Review Board approval, we retrospectively reviewed radiographs and data from a prospective 3-center study of arthroscopic outcomes of FAI in 150 patients (159 hips) who underwent arthroscopic surgery by 1 of 3 surgeons between March 2009 and June 2010. In all cases, digital images of anteroposterior pelvic radiographs were used for radiographic measurements. On these images, the LCEA is formed by the intersection of the vertical line (corrected for obliquity using a horizontal reference line connecting the inferior extents of both radiographic teardrops) through the center of the femoral head (determined with a digital centering tool) with the line extending to the lateral edge of the sourcil (radiographic eyebrow of the weight-bearing region or roof of the acetabulum). Measurements were made in blinded fashion (by a nonsurgeon coauthor, Dr. Nikhil Gupta, who completed training modules) and were confirmed without alteration by the principal investigator Dr. Dean K. Matsuda. Inclusion criteria were mild acetabular dysplasia (LCEA, 15°-24°) and mixed FAI including focal pincer component (LCEA, 25°-39°), radiographic crossover sign, and successful completion of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures at minimum 2-year follow-up. Exclusion criteria were severe dysplasia (LCEA, <15°), hip subluxation, broken Shenton line, global pincer FAI (LCEA, ≥40°), Tönnis grade 3 osteoarthritis, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, osteonecrosis, prior hip surgery, and unsuccessful completion of PRO measures. Outcome measures included investigator-blinded preoperative and postoperative Nonarthritic Hip Score (NAHS) and 5-point Likert satisfaction score. Complications, revision surgeries, and conversion arthroplasties were recorded.

Statistical Analysis

We examined outcomes with descriptive statistics for each of the candidate covariates in the model classified by femoroacetabular subtype: focal pincer and cam (mixed FAI) and dysplasia with cam. We examined the variables of sex, age, weight, height, body mass index, preoperative NAHS, presence of dysplasia (yes/no), presence of osteoarthritis (yes/no), Tönnis osteoarthritis grade, Outerbridge class, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, months of pain, bilateral procedure (yes/no), and pincer involvement with cam FAI (yes/no). Before beginning linear regression modeling, we screened the candidate variables for strong correlations with other variables and looked for those variables with minimal missing data. For all these covariates, we then performed linear regression with a selection process—both a stepwise selection method and a backward elimination method—to verify we determined the same model for 24-month NAHS, or to understand why we could not. Finally, we ran the model we found from the linear regression as a linear mixed model of 24-month NAHS with the dichotomous variables taken as fixed effects and the other variables taken as random effects, using variance-components representation for the random effects. We then examined 3-month and 12-month NAHS with the same variables selected for the 24-month model.

To further examine and verify the effects of dysplasia on outcomes found in our linear mixed model, we performed a nested case–control analysis matching each member of cohort D (cases) with 2 members of cohort M (controls). We used an optimal-matching algorithm to match focal patients in the linear regression dataset with dysplasia patients in the linear regression dataset in such a way as to minimize the overall differences between the datasets. We matched cases and controls on preoperative NAHS, age, sex, presence of osteoarthritis, months of pain, ASA score, and body mass index. The differences between the matched cases and controls (control value minus case value) were compared using Wilcoxon rank sum tests for statistical significance of differences from 0 (with differences generated for each control group member, 2 differences per case) to examine the quality of the match. Finally, we examined the statistical significance of the difference of the outcome variables (3-, 12-, and 24-month NAHS) from 0, again using Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Statistical significance was set at P < .05 using SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute).

Surgical Procedure

In all cases, supine outpatient hip arthroscopy was performed under general anesthesia. Anterolateral and modified midanterior portals16 were used. T-capsulotomies were performed in both cohorts. Cohort M underwent anterosuperior acetabuloplasty with a motorized burr. Labral refixation or selective débridement was performed in cohort M, whereas labral repair (with limited freshening of acetabular rim attachment site) or selective débridement (but no segmental resection) was performed in cohort D. Arthroscopic femoroplasty was performed with similar endpoints of 120° minimum hip flexion and 30° minimum flexed hip internal rotation with retention of the labral fluid seal. Capsular repair or plication was not performed for either cohort during the study period.

The cohorts underwent similar postoperative protocols: 2 weeks of protected ambulation using 2 crutches, exercise cycling without resistance beginning postoperative day 1, swimming at 2 weeks, elliptical machine workouts at 6 weeks, jogging at 12 weeks, and return to unrestricted athletics at 5 months.

Results

In cohort D, which consisted of 8 patients (5 female), mean age was 49.6 years, and mean LCEA was 19° (range, 16°-24°).

In cohort D, mean (SD) change in NAHS was +20.00 (6.24) (P = .25) at 3 months (n = 3), +14.33 (9.77) (P = .03) at 12 months (n = 6), and –0.75 (19.86) (P = .74) at 24 months (n = 8).

In cohort M, mean (SD) change in NAHS was +12.09 (18.98) (P < .0001) at 3 months (n = 45), +20.39 (16.49) (P < .0001) at 12 months (n = 57), and +21.99 (17.32) (P < .0001) at 24 months (n = 69).

In a pairwise case–control comparison, the mean (SD) change-from-baseline difference between cohorts D and M was +8.2 (12.85) (P = .31) at 3 months (n = 5), –8.7 (11.52) (P = .03) at 12 months (n = 10), and –31.06 (23.55) (P = .0002) at 24 months (n = 16). Dysplasia had an impact of –23.4 points on 24-month NAHS (standard error = 5.35 points; P < .0001), which corresponds to a 95% confidence interval of –12.9 to –33.9 points on NAHS.

Compared with cohort M, cohort D had significantly less NAHS improvement (P = .002), less satisfaction (P = .15) and more hip arthroplasty conversions (P = .22, not statistically significant).

There were no statistically significant differences between cohorts in demographics, preoperative variables, intraoperative findings, or surgical procedures in the regression analysis. Of the investigated variables, only group membership (cohort D) was a statistically significant predictor of poorer outcomes in the model of change from preoperative to 24 months. However, older age was associated with cohort D (older patients with dysplasia, P = .07), and therefore in the nested case–control analysis we were able to match on all variables except age (8.74 years older in cohort D, P = .0013) to a level of statistical nonsignificance.

Discussion

The principal finding of this study is the significantly poorer outcomes of mild dysplasia and cam FAI relative to mixed FAI after hip arthroscopy without capsular repair. Study group (cohort D) and control group (cohort M) had associated cam deformities treated with femoroplasty with similar decompression endpoints and labral preservation in the form of selective débridement or labral repair (no labral resections in either cohort) with similar rehabilitation protocols.

Our study findings suggest short-term improvement may be followed by midterm worsening in patients with mild dysplasia and sustained improvement in patients with mixed FAI. These findings have practical clinical applications. Jackson and colleagues5 reported on a patient who, after undergoing “successful” arthroscopic surgery for mild dysplasia, clinically deteriorated after 13 months and eventually required PAO. Patients undergoing isolated hip arthroscopy for mild dysplasia with cam FAI should be informed of the possible need for secondary PAO or even hip arthroplasty, be followed up more often and longer than comparable patients with FAI, and have follow-up supplemented with interval radiographs.4 If even subtle subluxation or joint narrowing occurs, we suggest resumption of protected weight-bearing and prompt progression to PAO in younger patients with joint congruency or eventual conversion arthroplasty in older ones.

Although mean preoperative NAHS (52.88) and mean 24-month postoperative NAHS (52.13) suggest essentially no change in PROs for cohort D, all patients with dysplasia either worsened or improved, though those who improved did so at a lesser relative magnitude than those with mixed FAI (cohort M). This finding may help explain the divergent outcomes reported in the literature on dysplasia treated with hip arthroscopy.

Cohort D was older than cohort M, but the difference was not statistically significant. Age may still be a confounding variable, and it may have contributed in part to the poorer outcomes for the patients with dysplasia. However, emerging studies demonstrate select older patients with FAI and/or labral tears may have successful outcomes with arthroscopic intervention.17,18 Our findings support mild dysplasia as the main contributor to the poor outcomes observed in this study.

With identical postoperative rehabilitation protocols, patients in both cohorts typically were ambulating without crutches by the end of postoperative week 2. Delayed weight-bearing has been suggested as contributing to successful outcomes in the setting of dysplasia7,19,20 but has not been shown to adversely affect nondysplastic hips.21 Whether delayed weight-bearing contributed to the poor outcomes in our dysplasia cohort is unknown, but the early successful outcomes may discount its influence.

Our findings support successful outcomes of arthroscopic treatment of mixed FAI (specifically focal pincer plus cam FAI) without capsular repair. Perhaps more important, we found inferior outcomes of arthroscopic treatment of mild dysplasia plus cam FAI without capsular repair—filling the knowledge gap regarding the need for arthroscopic capsular repair for mild dysplasia. Although a recent study demonstrated no significant difference in outcomes between hip arthroscopy with and without capsular repair,22 2 studies specific to mild dysplasia demonstrated successful outcomes of capsular repair.7,9 One found that mild dysplasia treated with arthroscopy, including capsular plication, resulted in 77% good/excellent outcomes and LCEA as low as 18° at minimum 2-year follow-up.7 The other found clinical improvement in mild dysplasia (LCEA, 15°-19°) when capsular repair was performed as part of arthroscopic treatment.9 In the present study, we retrospectively reviewed outcomes from a prospective study performed in 2009 to 2010, before the era of common capsular repair. It appears that capsular repair9 or plication7 in the setting of mild dysplasia may yield improved outcomes approaching those of arthroscopic FAI surgery. Our study results showed that, despite labral preservation and cam decompression, mild dysplasia without the closure of T-capsulotomy had inferior outcomes at 2 years. However, we do not know if outcomes would have been better with capsular repair or plication and/or smaller capsulotomies, perhaps with minimal violation of the iliofemoral ligament in this specific subset of patients. Furthermore, we do not know if optimal outcomes can best be achieved with arthroscopic and/or open surgery, with or without acetabular reorientation, in patients with mild dysplasia and cam FAI.

Dysplasia with cam FAI is an emerging common condition for which patients may seek less invasive treatment in the form of hip arthroscopy. The findings of this study suggest caution in using hip arthroscopy without capsular repair in the treatment of mild dysplasia with cam FAI, even in the presence of cam decompression and labral and acetabular rim preservation.

Study Strengths and Limitations

One strength was the relative lack of surgeon bias. When the surgeries were performed (2009-2010), we recognized cam and pincer FAI but did not discriminate for mild dysplasia, because at that time it was not known to be a potential predictor of poorer outcomes. Another strength was the strict methodology, with blinding of all investigator surgeons to PROs and stringent retention of all PROs, including “failures” (eg, total hip arthroplasty conversions and complications), in both cohorts. Moreover, the crucial case-control analysis matched on multiple variables verified statistically significant results demonstrating poorer outcomes at minimum 2-year follow-up, despite more improvement in the dysplasia cohort at 3 months. The latter, we think, is also valuable new information; it emphasizes the need for close and prolonged follow-up of patients with mild dysplasia despite early improvement.

Limitations include the small number of study patients, the retrospective study design (using prospectively collected data), and the isolated use of LCEA to define dysplasia. Pereira and colleagues23 recommended using LCEA with Tönnis angle to define minor dysplasia. Although dysplasia cannot be precisely defined with only this radiographic measurement, LCEA has been shown to be a reliable, clinically relevant measure.24 In addition, LCEA has been used in most reports on arthroscopic management of dysplastic hips and thus allows for comparison. Furthermore, other studies have used LCEA of <15° as a threshold between mild and severe dysplasia, and we did as well. This broad inclusion criterion allowed for heterogeneity in our mild dysplasia cohort and was a study limitation. Interobserver reliability of measured LCEA was not assessed and is another limitation.

The initial prospective study (2009) did not record α angles to quantify cam FAI. This is a study limitation. However, the surgical range-of-motion endpoints considered sufficient for cam decompression were the same in both cohorts. In addition, femoral version was not assessed in the original database (2009-2010), as this aspect of hip anatomy was not thought significant during initial data collection. These areas of interest merit further investigation.

Use of a focal pincer cohort may be challenged as a suboptimal control group. However, there were very few completely normal acetabulae with pure cam FAI in the original prospective study, and the focal pincer cohort was used as a control cohort in previous studies.25

Conclusion

The common combination of mild dysplasia and cam FAI has poorer outcomes than mixed FAI after arthroscopic surgery without capsular repair.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):E47-E53. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

Take-Home Points

- Cam deformity often occurs with dysplasia.

- Borderline or mild dysplasia has been treated with isolated hip arthroscopy.

- Avoid rim trimming that can make mild dysplasia more severe.

- Labral preservation, cam decompression, and capsular repair or plication are currently suggested.

- Poorer outcomes occurred in borderline or mild dysplasia with cam impingement relative to controls following hip arthroscopy without capsular repair.

- Initial clinical improvement may be followed by clinical deterioration suggesting close long-term follow-up with prompt addition of reorientation acetabular osteotomy if indicated.

- It is unknown whether small capsulotomies may yield comparable outcomes with larger capsulotomies plus repair.

It is unknown whether small capsulotomies may yield comparable outcomes with larger capsulotomies plus repair. There is growing interest in hip preservation surgery in general and arthroscopic hip preservation in particular. Chondrolabral pathology leading to symptoms and degenerative progression typically is caused by structural abnormalities, mainly femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) and developmental dysplasia of the hip. Unlike the bony overcoverage of pincer FAI, developmental dysplasia of the hip typically exhibits insufficient anterolateral coverage of the femoral head.

The role of hip arthroscopy in the treatment of dysplasia remains undefined. Emerging evidence shows a high incidence of dysplasia with associated cam deformity,1,2 but there is a paucity of evidence-based information for this specific patient population. Clinical outcomes of hip arthroscopy in the setting of dysplasia are conflicting: some poor3-5 and others successful.1,6-9 Although reorientation periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) is considered a mainstay in the treatment of dysplasia—providing improvement in symptoms, deficient anterolateral acetabular coverage, and hip biomechanics—midterm failure rates approaching 24% have been reported.10-12 Many young patients with symptomatic dysplasia want a surgical option that is less invasive than open PAO.4 Intra-articular central compartment pathology and cam FAI commonly occur with dysplasia and are amenable to arthroscopic treatment.1,13,14 Moreover, staged PAO may be successful in cases in which arthroscopic intervention fails to provide clinical improvement.5,15

Emerging evidence suggests beneficial effects of arthroscopic capsular repair or plication in the setting of borderline or mild dysplasia.7,9 However, the literature provides little information on arthroscopic outcomes without capsular repair. One study found poor outcomes of arthroscopic surgery for dysplasia, but its patients underwent labral débridement, not repair.3 Two patients in a case report demonstrated rapidly progressive osteoarthritis after arthroscopic labral repairs and concurrent femoroplasties for cam FAI, but each had marked dysplasia with a lateral center-edge angle (LCEA) of <15°.4

Arthroscopy with capsular repair has been assumed to provide better outcomes than arthroscopy without repair, but to our knowledge there are no studies that have compared outcomes of mild dysplasia with cam FAI and outcomes of mixed FAI treated without capsular repair. Clinical equipoise makes it ethically challenging to perform a prospective study comparing dysplasia treated with and without capsular repair. We conducted a study to compare outcomes of mild dysplasia with cam FAI and outcomes of mixed FAI treated with arthroscopic surgery and to fill the knowledge gap regarding outcomes of mild dysplasia treated without capsular repair.

Methods

In this study, which received Institutional Review Board approval, we retrospectively reviewed radiographs and data from a prospective 3-center study of arthroscopic outcomes of FAI in 150 patients (159 hips) who underwent arthroscopic surgery by 1 of 3 surgeons between March 2009 and June 2010. In all cases, digital images of anteroposterior pelvic radiographs were used for radiographic measurements. On these images, the LCEA is formed by the intersection of the vertical line (corrected for obliquity using a horizontal reference line connecting the inferior extents of both radiographic teardrops) through the center of the femoral head (determined with a digital centering tool) with the line extending to the lateral edge of the sourcil (radiographic eyebrow of the weight-bearing region or roof of the acetabulum). Measurements were made in blinded fashion (by a nonsurgeon coauthor, Dr. Nikhil Gupta, who completed training modules) and were confirmed without alteration by the principal investigator Dr. Dean K. Matsuda. Inclusion criteria were mild acetabular dysplasia (LCEA, 15°-24°) and mixed FAI including focal pincer component (LCEA, 25°-39°), radiographic crossover sign, and successful completion of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures at minimum 2-year follow-up. Exclusion criteria were severe dysplasia (LCEA, <15°), hip subluxation, broken Shenton line, global pincer FAI (LCEA, ≥40°), Tönnis grade 3 osteoarthritis, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, osteonecrosis, prior hip surgery, and unsuccessful completion of PRO measures. Outcome measures included investigator-blinded preoperative and postoperative Nonarthritic Hip Score (NAHS) and 5-point Likert satisfaction score. Complications, revision surgeries, and conversion arthroplasties were recorded.

Statistical Analysis

We examined outcomes with descriptive statistics for each of the candidate covariates in the model classified by femoroacetabular subtype: focal pincer and cam (mixed FAI) and dysplasia with cam. We examined the variables of sex, age, weight, height, body mass index, preoperative NAHS, presence of dysplasia (yes/no), presence of osteoarthritis (yes/no), Tönnis osteoarthritis grade, Outerbridge class, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, months of pain, bilateral procedure (yes/no), and pincer involvement with cam FAI (yes/no). Before beginning linear regression modeling, we screened the candidate variables for strong correlations with other variables and looked for those variables with minimal missing data. For all these covariates, we then performed linear regression with a selection process—both a stepwise selection method and a backward elimination method—to verify we determined the same model for 24-month NAHS, or to understand why we could not. Finally, we ran the model we found from the linear regression as a linear mixed model of 24-month NAHS with the dichotomous variables taken as fixed effects and the other variables taken as random effects, using variance-components representation for the random effects. We then examined 3-month and 12-month NAHS with the same variables selected for the 24-month model.

To further examine and verify the effects of dysplasia on outcomes found in our linear mixed model, we performed a nested case–control analysis matching each member of cohort D (cases) with 2 members of cohort M (controls). We used an optimal-matching algorithm to match focal patients in the linear regression dataset with dysplasia patients in the linear regression dataset in such a way as to minimize the overall differences between the datasets. We matched cases and controls on preoperative NAHS, age, sex, presence of osteoarthritis, months of pain, ASA score, and body mass index. The differences between the matched cases and controls (control value minus case value) were compared using Wilcoxon rank sum tests for statistical significance of differences from 0 (with differences generated for each control group member, 2 differences per case) to examine the quality of the match. Finally, we examined the statistical significance of the difference of the outcome variables (3-, 12-, and 24-month NAHS) from 0, again using Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Statistical significance was set at P < .05 using SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute).

Surgical Procedure

In all cases, supine outpatient hip arthroscopy was performed under general anesthesia. Anterolateral and modified midanterior portals16 were used. T-capsulotomies were performed in both cohorts. Cohort M underwent anterosuperior acetabuloplasty with a motorized burr. Labral refixation or selective débridement was performed in cohort M, whereas labral repair (with limited freshening of acetabular rim attachment site) or selective débridement (but no segmental resection) was performed in cohort D. Arthroscopic femoroplasty was performed with similar endpoints of 120° minimum hip flexion and 30° minimum flexed hip internal rotation with retention of the labral fluid seal. Capsular repair or plication was not performed for either cohort during the study period.

The cohorts underwent similar postoperative protocols: 2 weeks of protected ambulation using 2 crutches, exercise cycling without resistance beginning postoperative day 1, swimming at 2 weeks, elliptical machine workouts at 6 weeks, jogging at 12 weeks, and return to unrestricted athletics at 5 months.

Results

In cohort D, which consisted of 8 patients (5 female), mean age was 49.6 years, and mean LCEA was 19° (range, 16°-24°).

In cohort D, mean (SD) change in NAHS was +20.00 (6.24) (P = .25) at 3 months (n = 3), +14.33 (9.77) (P = .03) at 12 months (n = 6), and –0.75 (19.86) (P = .74) at 24 months (n = 8).

In cohort M, mean (SD) change in NAHS was +12.09 (18.98) (P < .0001) at 3 months (n = 45), +20.39 (16.49) (P < .0001) at 12 months (n = 57), and +21.99 (17.32) (P < .0001) at 24 months (n = 69).

In a pairwise case–control comparison, the mean (SD) change-from-baseline difference between cohorts D and M was +8.2 (12.85) (P = .31) at 3 months (n = 5), –8.7 (11.52) (P = .03) at 12 months (n = 10), and –31.06 (23.55) (P = .0002) at 24 months (n = 16). Dysplasia had an impact of –23.4 points on 24-month NAHS (standard error = 5.35 points; P < .0001), which corresponds to a 95% confidence interval of –12.9 to –33.9 points on NAHS.

Compared with cohort M, cohort D had significantly less NAHS improvement (P = .002), less satisfaction (P = .15) and more hip arthroplasty conversions (P = .22, not statistically significant).

There were no statistically significant differences between cohorts in demographics, preoperative variables, intraoperative findings, or surgical procedures in the regression analysis. Of the investigated variables, only group membership (cohort D) was a statistically significant predictor of poorer outcomes in the model of change from preoperative to 24 months. However, older age was associated with cohort D (older patients with dysplasia, P = .07), and therefore in the nested case–control analysis we were able to match on all variables except age (8.74 years older in cohort D, P = .0013) to a level of statistical nonsignificance.

Discussion

The principal finding of this study is the significantly poorer outcomes of mild dysplasia and cam FAI relative to mixed FAI after hip arthroscopy without capsular repair. Study group (cohort D) and control group (cohort M) had associated cam deformities treated with femoroplasty with similar decompression endpoints and labral preservation in the form of selective débridement or labral repair (no labral resections in either cohort) with similar rehabilitation protocols.

Our study findings suggest short-term improvement may be followed by midterm worsening in patients with mild dysplasia and sustained improvement in patients with mixed FAI. These findings have practical clinical applications. Jackson and colleagues5 reported on a patient who, after undergoing “successful” arthroscopic surgery for mild dysplasia, clinically deteriorated after 13 months and eventually required PAO. Patients undergoing isolated hip arthroscopy for mild dysplasia with cam FAI should be informed of the possible need for secondary PAO or even hip arthroplasty, be followed up more often and longer than comparable patients with FAI, and have follow-up supplemented with interval radiographs.4 If even subtle subluxation or joint narrowing occurs, we suggest resumption of protected weight-bearing and prompt progression to PAO in younger patients with joint congruency or eventual conversion arthroplasty in older ones.

Although mean preoperative NAHS (52.88) and mean 24-month postoperative NAHS (52.13) suggest essentially no change in PROs for cohort D, all patients with dysplasia either worsened or improved, though those who improved did so at a lesser relative magnitude than those with mixed FAI (cohort M). This finding may help explain the divergent outcomes reported in the literature on dysplasia treated with hip arthroscopy.

Cohort D was older than cohort M, but the difference was not statistically significant. Age may still be a confounding variable, and it may have contributed in part to the poorer outcomes for the patients with dysplasia. However, emerging studies demonstrate select older patients with FAI and/or labral tears may have successful outcomes with arthroscopic intervention.17,18 Our findings support mild dysplasia as the main contributor to the poor outcomes observed in this study.

With identical postoperative rehabilitation protocols, patients in both cohorts typically were ambulating without crutches by the end of postoperative week 2. Delayed weight-bearing has been suggested as contributing to successful outcomes in the setting of dysplasia7,19,20 but has not been shown to adversely affect nondysplastic hips.21 Whether delayed weight-bearing contributed to the poor outcomes in our dysplasia cohort is unknown, but the early successful outcomes may discount its influence.

Our findings support successful outcomes of arthroscopic treatment of mixed FAI (specifically focal pincer plus cam FAI) without capsular repair. Perhaps more important, we found inferior outcomes of arthroscopic treatment of mild dysplasia plus cam FAI without capsular repair—filling the knowledge gap regarding the need for arthroscopic capsular repair for mild dysplasia. Although a recent study demonstrated no significant difference in outcomes between hip arthroscopy with and without capsular repair,22 2 studies specific to mild dysplasia demonstrated successful outcomes of capsular repair.7,9 One found that mild dysplasia treated with arthroscopy, including capsular plication, resulted in 77% good/excellent outcomes and LCEA as low as 18° at minimum 2-year follow-up.7 The other found clinical improvement in mild dysplasia (LCEA, 15°-19°) when capsular repair was performed as part of arthroscopic treatment.9 In the present study, we retrospectively reviewed outcomes from a prospective study performed in 2009 to 2010, before the era of common capsular repair. It appears that capsular repair9 or plication7 in the setting of mild dysplasia may yield improved outcomes approaching those of arthroscopic FAI surgery. Our study results showed that, despite labral preservation and cam decompression, mild dysplasia without the closure of T-capsulotomy had inferior outcomes at 2 years. However, we do not know if outcomes would have been better with capsular repair or plication and/or smaller capsulotomies, perhaps with minimal violation of the iliofemoral ligament in this specific subset of patients. Furthermore, we do not know if optimal outcomes can best be achieved with arthroscopic and/or open surgery, with or without acetabular reorientation, in patients with mild dysplasia and cam FAI.

Dysplasia with cam FAI is an emerging common condition for which patients may seek less invasive treatment in the form of hip arthroscopy. The findings of this study suggest caution in using hip arthroscopy without capsular repair in the treatment of mild dysplasia with cam FAI, even in the presence of cam decompression and labral and acetabular rim preservation.

Study Strengths and Limitations

One strength was the relative lack of surgeon bias. When the surgeries were performed (2009-2010), we recognized cam and pincer FAI but did not discriminate for mild dysplasia, because at that time it was not known to be a potential predictor of poorer outcomes. Another strength was the strict methodology, with blinding of all investigator surgeons to PROs and stringent retention of all PROs, including “failures” (eg, total hip arthroplasty conversions and complications), in both cohorts. Moreover, the crucial case-control analysis matched on multiple variables verified statistically significant results demonstrating poorer outcomes at minimum 2-year follow-up, despite more improvement in the dysplasia cohort at 3 months. The latter, we think, is also valuable new information; it emphasizes the need for close and prolonged follow-up of patients with mild dysplasia despite early improvement.

Limitations include the small number of study patients, the retrospective study design (using prospectively collected data), and the isolated use of LCEA to define dysplasia. Pereira and colleagues23 recommended using LCEA with Tönnis angle to define minor dysplasia. Although dysplasia cannot be precisely defined with only this radiographic measurement, LCEA has been shown to be a reliable, clinically relevant measure.24 In addition, LCEA has been used in most reports on arthroscopic management of dysplastic hips and thus allows for comparison. Furthermore, other studies have used LCEA of <15° as a threshold between mild and severe dysplasia, and we did as well. This broad inclusion criterion allowed for heterogeneity in our mild dysplasia cohort and was a study limitation. Interobserver reliability of measured LCEA was not assessed and is another limitation.

The initial prospective study (2009) did not record α angles to quantify cam FAI. This is a study limitation. However, the surgical range-of-motion endpoints considered sufficient for cam decompression were the same in both cohorts. In addition, femoral version was not assessed in the original database (2009-2010), as this aspect of hip anatomy was not thought significant during initial data collection. These areas of interest merit further investigation.

Use of a focal pincer cohort may be challenged as a suboptimal control group. However, there were very few completely normal acetabulae with pure cam FAI in the original prospective study, and the focal pincer cohort was used as a control cohort in previous studies.25

Conclusion

The common combination of mild dysplasia and cam FAI has poorer outcomes than mixed FAI after arthroscopic surgery without capsular repair.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):E47-E53. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Paliobeis CP, Villar RN. The prevalence of dysplasia in femoroacetabular impingement. Hip Int. 2011;21(2):141-145.

2. Clohisy JC, Nunley RM, Carlisle JC, Schoenecker PL. Incidence and characteristics of femoral deformities in the dysplastic hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(1):128-134.

3. Parvizi J, Bican O, Bender B, et al. Arthroscopy for labral tears in patients with developmental dysplasia of the hip: a cautionary note. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(6 suppl):110-113.

4. Matsuda DK, Khatod M. Rapidly progressive osteoarthritis after arthroscopic labral repair in patients with hip dysplasia. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(11):1738-1743.

5. Jackson TJ, Watson J, LaReau JM, Domb BG. Periacetabular osteotomy and arthroscopic labral repair after failed hip arthroscopy due to iatrogenic aggravation of hip dysplasia. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(4):911-914.

6. Byrd JW, Jones KS. Hip arthroscopy in the presence of dysplasia. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(10):1055-1060.

7. Domb BG, Stake CE, Lindner D, El-Bitar Y, Jackson TJ. Arthroscopic capsular plication and labral preservation in borderline hip dysplasia: two-year clinical outcomes of a surgical approach to a challenging problem. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(11):2591-2598.

8. Jayasekera N, Aprato A, Villar RN. Hip arthroscopy in the presence of acetabular dysplasia. Open Orthop J. 2015;9:185-187.

9. Fukui K, Briggs KK, Trindade CA, Philippon MJ. Outcomes after labral repair in patients with femoroacetabular impingement and borderline dysplasia. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(12):2371-2379.

10. Siebenrock KA, Leunig M, Ganz R. Periacetabular osteotomy: the Bernese experience. Instr Course Lect. 2001;50:239-245.

11. Garras DN, Crowder TT, Olson SA. Medium-term results of the Bernese periacetabular osteotomy in the treatment of symptomatic developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(6):721-724.

12. Biedermann R, Donnan L, Gabriel A, Wachter R, Krismer M, Behensky H. Complications and patient satisfaction after periacetabular pelvic osteotomy. Int Orthop. 2008;32(5):611-617.

13. Ross JR, Zaltz I, Nepple JJ, Schoenecker PL, Clohisy JC. Arthroscopic disease classification and interventions as an adjunct in the treatment of acetabular dysplasia. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(suppl):72S-78S.

14. Domb BG, LaReau JM, Baydoun H, Botser I, Millis MB, Yen YM. Is intraarticular pathology common in patients with hip dysplasia undergoing periacetabular osteotomy? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(2):674-680.

15. Kain MS, Novais EN, Vallim C, Millis MB, Kim YJ. Periacetabular osteotomy after failed hip arthroscopy for labral tears in patients with acetabular dysplasia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(suppl 2):57-61.

16. Matsuda DK, Villamor A. The modified mid-anterior portal for hip arthroscopy. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3(4):e469-e474.

17. Javed A, O’Donnell JM. Arthroscopic femoral osteochondroplasty for cam femoroacetabular impingement in patients over 60 years of age. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(3):326-331.

18. Redmond JM, Gupta A, Cregar WM, Hammarstedt JE, Gui C, Domb BG. Arthroscopic treatment of labral tears in patients aged 60 years or older. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(10):1921-1927.

19. Mei-Dan O, McConkey MO, Brick M. Catastrophic failure of hip arthroscopy due to iatrogenic instability: can partial division of the ligamentum teres and iliofemoral ligament cause subluxation? Arthroscopy. 2012;28(3):440-445.

20. Benali Y, Katthagen BD. Hip subluxation as a complication of arthroscopic debridement. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(4):405-407.

21. Jayasekera N, Aprato A, Villar RN. Are crutches required after hip arthroscopy? A case–control study. Hip Int. 2013;23(3):269-273.

22. Domb BG, Stake CE, Finley ZJ, Chen T, Giordano BD. Influence of capsular repair versus unrepaired capsulotomy on 2-year clinical outcomes after arthroscopic hip preservation surgery. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(4):643-650.

23. Pereira F, Giles A, Wood G, Board TN. Recognition of minor adult hip dysplasia: which anatomical indices are important? Hip Int. 2014;24(2):175-179.

24. Murphy SB, Ganz R, Müller ME. The prognosis in untreated dysplasia of the hip. A study of radiographic factors that predict the outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(7):985-989.

25. Matsuda DK, Gupta N, Burchette R, Sehgal B. Arthroscopic surgery for global versus focal pincer femoroacetabular impingement: are the outcomes different? J Hip Preserv Surg. 2015;2(1):42-50.

1. Paliobeis CP, Villar RN. The prevalence of dysplasia in femoroacetabular impingement. Hip Int. 2011;21(2):141-145.

2. Clohisy JC, Nunley RM, Carlisle JC, Schoenecker PL. Incidence and characteristics of femoral deformities in the dysplastic hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(1):128-134.

3. Parvizi J, Bican O, Bender B, et al. Arthroscopy for labral tears in patients with developmental dysplasia of the hip: a cautionary note. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(6 suppl):110-113.

4. Matsuda DK, Khatod M. Rapidly progressive osteoarthritis after arthroscopic labral repair in patients with hip dysplasia. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(11):1738-1743.

5. Jackson TJ, Watson J, LaReau JM, Domb BG. Periacetabular osteotomy and arthroscopic labral repair after failed hip arthroscopy due to iatrogenic aggravation of hip dysplasia. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(4):911-914.

6. Byrd JW, Jones KS. Hip arthroscopy in the presence of dysplasia. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(10):1055-1060.

7. Domb BG, Stake CE, Lindner D, El-Bitar Y, Jackson TJ. Arthroscopic capsular plication and labral preservation in borderline hip dysplasia: two-year clinical outcomes of a surgical approach to a challenging problem. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(11):2591-2598.

8. Jayasekera N, Aprato A, Villar RN. Hip arthroscopy in the presence of acetabular dysplasia. Open Orthop J. 2015;9:185-187.

9. Fukui K, Briggs KK, Trindade CA, Philippon MJ. Outcomes after labral repair in patients with femoroacetabular impingement and borderline dysplasia. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(12):2371-2379.

10. Siebenrock KA, Leunig M, Ganz R. Periacetabular osteotomy: the Bernese experience. Instr Course Lect. 2001;50:239-245.

11. Garras DN, Crowder TT, Olson SA. Medium-term results of the Bernese periacetabular osteotomy in the treatment of symptomatic developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(6):721-724.

12. Biedermann R, Donnan L, Gabriel A, Wachter R, Krismer M, Behensky H. Complications and patient satisfaction after periacetabular pelvic osteotomy. Int Orthop. 2008;32(5):611-617.

13. Ross JR, Zaltz I, Nepple JJ, Schoenecker PL, Clohisy JC. Arthroscopic disease classification and interventions as an adjunct in the treatment of acetabular dysplasia. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(suppl):72S-78S.

14. Domb BG, LaReau JM, Baydoun H, Botser I, Millis MB, Yen YM. Is intraarticular pathology common in patients with hip dysplasia undergoing periacetabular osteotomy? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(2):674-680.

15. Kain MS, Novais EN, Vallim C, Millis MB, Kim YJ. Periacetabular osteotomy after failed hip arthroscopy for labral tears in patients with acetabular dysplasia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(suppl 2):57-61.

16. Matsuda DK, Villamor A. The modified mid-anterior portal for hip arthroscopy. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3(4):e469-e474.

17. Javed A, O’Donnell JM. Arthroscopic femoral osteochondroplasty for cam femoroacetabular impingement in patients over 60 years of age. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(3):326-331.

18. Redmond JM, Gupta A, Cregar WM, Hammarstedt JE, Gui C, Domb BG. Arthroscopic treatment of labral tears in patients aged 60 years or older. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(10):1921-1927.

19. Mei-Dan O, McConkey MO, Brick M. Catastrophic failure of hip arthroscopy due to iatrogenic instability: can partial division of the ligamentum teres and iliofemoral ligament cause subluxation? Arthroscopy. 2012;28(3):440-445.

20. Benali Y, Katthagen BD. Hip subluxation as a complication of arthroscopic debridement. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(4):405-407.

21. Jayasekera N, Aprato A, Villar RN. Are crutches required after hip arthroscopy? A case–control study. Hip Int. 2013;23(3):269-273.

22. Domb BG, Stake CE, Finley ZJ, Chen T, Giordano BD. Influence of capsular repair versus unrepaired capsulotomy on 2-year clinical outcomes after arthroscopic hip preservation surgery. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(4):643-650.

23. Pereira F, Giles A, Wood G, Board TN. Recognition of minor adult hip dysplasia: which anatomical indices are important? Hip Int. 2014;24(2):175-179.

24. Murphy SB, Ganz R, Müller ME. The prognosis in untreated dysplasia of the hip. A study of radiographic factors that predict the outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(7):985-989.

25. Matsuda DK, Gupta N, Burchette R, Sehgal B. Arthroscopic surgery for global versus focal pincer femoroacetabular impingement: are the outcomes different? J Hip Preserv Surg. 2015;2(1):42-50.

Multicenter Outcomes After Hip Arthroscopy: Epidemiology (MASH Study Group). What Are We Seeing in the Office, and Who Are We Choosing to Treat?

Take-Home Points

- MASH is a multicenter arthroscopic study of the hip that features a large prospective database of 10 separate institutions in the United States.

- The mean patient demographic was age 34.6 years, BMI 25.9 kg/m2, 62.8% females, and 97% white.

- Most patients had anterior or groin pain, but 17.6% had lateral hip pain, 13.8% had posterior hip pain, and 2.9% had low back or sacral pain.

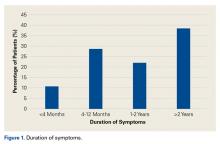

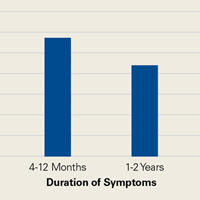

- Patients typically had pain for about 1 year that was worsened with athletic activity as well as sitting.

- The most common surgical procedures that were performed included labral surgery in 64.7%, femoroplasty in 49.9%, acetabuloplasty in 33.3%, and chondroplasty in 31.1%

Arthroscopic surgery of the hip has been growing over the past decade, with drastically increasing rates of arthroscopic hip procedures and increased education and interest in orthopedic trainees.1-3 The rise of this minimally invasive surgical technique may be attributed to expanding knowledge of surgical management of morphologic hip disorders as a means of hip preservation. Many arthroscopic techniques have been developed to treat intra-articular hip joint pathologies, including femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), labral tears, and cartilage damage.4-11 These hip pathologies are widely recognized as painful limitations to activities of daily living and sports as well as early indicators of hip osteoarthritis.12,13 Limited evidence suggests that arthroscopic treatment of these intra-articular hip joint pathologies preserves the hip from osteoarthritis and progression to total hip arthroplasty.13-15

FAI is the most common etiology of pathologies related to arthroscopic surgery of the hip, including both labral tears and cartilage damage.4,7,14 FAI is a morphologic bone disorder characterized by impingement of the femur and the acetabulum on flexion or rotation. The etiology of FAI is not completely understood, but evidence suggests that stress to the proximal femoral physis during skeletal growth increases the risk of developing femoral head and neck deformations leading to cam-type FAI.15-17 Understanding the characteristics of the patient population in which FAI occurs may shed light on the processes of intra-articular damage, such as labral tears and cartilage damage.

In the present study, we collected epidemiologic data, including demographics, pathologic entities treated, patient-reported measures of disease, and surgical treatment preferences, on a hip pathology population that elected to undergo arthroscopic surgery. These data are important in gaining a better understanding of the population and environment in which hip arthroscopy is performed across multiple centers throughout the United States and may help guide clinical practice and research to advance hip arthroscopy.

Methods

The Multicenter Arthroscopic Study of the Hip (MASH) Study Group conducts multicenter clinical studies in arthroscopic hip preservation surgery. Patients are enrolled in this large prospective longitudinal study at 10 sites nationwide by 10 fellowship-trained hip arthroscopists. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from all institutions before patient enrollment. After enrollment, we collected comprehensive patient data, including demographics, common symptoms and their duration, provocative activities, patient-reported outcome measures (modified Harris Hip Score, International Hip Outcome Tool, 12-item Short Form Health Survey, visual analog scale pain rating, Hip Outcome Score), physical examination findings, imaging findings, diagnoses, surgical findings, and surgical procedures.

All study participants were patients undergoing arthroscopic hip surgery by one of the members of the MASH Study Group. Patients with incomplete preoperative information (needed for data analysis) were excluded. Data analysis was performed with SPSS Statistics Version 21.0 (SPSS Inc.) to obtain descriptive statistics of the quantitative data and frequencies of the nominal data.

Results

Between January 2014 and November 2016, we enrolled 1738 patients (647 male, 1091 female) in the study. Table 1 lists the demographics of the population.

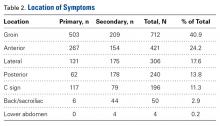

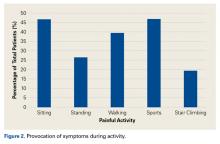

Regarding symptom location, 40.9% of patients described pain in the groin region, 24.2% in the anterior hip region, and 11.3% in a C-sign distribution (Table 2).

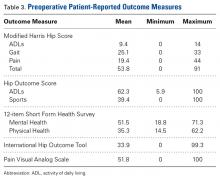

Table 3 lists the results of the patient-reported outcome measures.

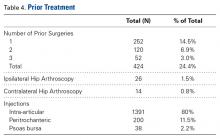

Of the 1738 patients enrolled, 424 (24.4%) had prior surgery related to current symptoms, 252 (14.5%) had 1 previous surgery, 120 (6.9%) had 2 previous surgeries, and 52 (3%) had 3 previous surgeries. Twenty-six patients (1.5%) had a previous revision hip arthroscopy on the ipsilateral side, and 14 (0.8%) had a previous hip arthroscopy on the contralateral side. Before surgery, 80% of patients received an intra-articular injection of corticosteroid and lidocaine. The peritrochanteric region was injected in 11.5% of patients and the psoas bursa in 2.2% (Table 4).

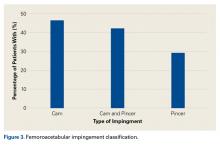

Of the 1011 patients who had magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed, 943 (93.3%) had abnormal acetabular labrum findings, and 163 (17.1%) had acetabular articular damage. According to radiographic evaluation, 953 patients had abnormal hip joint morphology consistent with FAI. Figure 3 shows the FAI classification percentages.

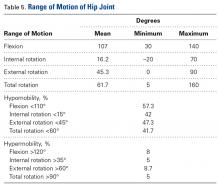

On clinical examination, 1079 patients (62.1%) had a positive anterior impingement sign. The subspine impingement sign was positive in 447 patients (25.7%), and the trochanteric pain sign was positive in 400 (23%). Table 5 lists range-of-motion values for flexion and hip rotation from 90° of flexion.

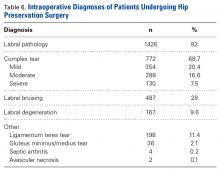

As seen in Table 6, labral pathology was the most common diagnosis (1426/1738 patients, 82%).

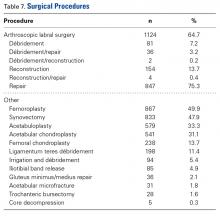

As seen in Table 7, the most common procedure was femoroplasty (867/1738, 49.9%).

Discussion

In this study, we collected epidemiologic data (demographics, pathologic entities treated, patient-reported measures of disease, surgical treatment preferences) from a large multicenter population of hip pathology patients who elected to undergo arthroscopic surgery. Our results showed these patients were most commonly younger to middle-aged white females with pain primarily in the groin region. Most had pain for at least 1 year, and it was commonly exacerbated by sitting and athletics. Patients reported clinically significant pain and functional limitation, which showed evidence of affecting general physical and mental health. It was not uncommon for patients to have undergone another, related surgery and nonoperative treatments, including intra-articular injection and/or physical therapy, before surgery. There was a high incidence of abnormal hip morphology suggestive of a cam lesion, but the incidence of arthritic changes on radiographs was relatively low. Labral tear was the most common diagnosis, and most often it was addressed with repair. Many patients underwent femoroplasty, acetabuloplasty, and chondroplasty in addition to labral repair.

According to patient-reported outcome measures administered before surgery, 40% to 65% of patients seeking hip preservation surgery reported functional deficits and pain—which falls within the range of results from other multicenter studies on the epidemiology of FAI.18,19 There was, however, a high amount of variability in individual scores on the functional and pain measures; some patients rated their functional ability very high. These findings were supported by the general health forms measuring global physical and mental health. Mean Physical Health and Mental Health scores on the 12-item Short Form Health Survey indicated that patients seeking hip preservation surgery thought their hip condition affected their general well-being. This finding is consistent with research on FAI,18 hip arthritis,20 and total hip arthroplasty.19Our results further showed that hip arthroscopists commonly prescribed alternative treatment measures ahead of surgery. Before elective surgery, 80% of patients received an intra-articular injection, underwent physical therapy, or both. This could suggest a high failure rate for patients who chose conservative treatment approaches for hip-related pathology. However, our study was limited in that it may have included patients who had improved significantly with conservative measures and decided to forgo arthroscopic hip surgery. Although conservative treatment often is recommended in an effort to potentially avoid surgery, there is a lack of research evaluating the efficacy of nonoperative care.21,22Analysis of diagnostic imaging and clinical examination findings revealed some unique characteristics of patients undergoing elective hip preservation surgery. MRI showed labral pathology in an overwhelming majority of these patients, but few had evidence of articular damage. Previous research has found a 67% rate of arthritic changes on diagnostic imaging, but our rate was much lower (17%).23 Radiograph evaluation confirmed the pattern: More than 90% of our patients had Tönnis grade 0 osteoarthritis. Tönnis grade 1 or 2 osteoarthritis is a predictor of acetabular cartilage degeneration,23 and long-term studies have related these osteoarthritic changes to poorer hip arthroscopy outcomes.24 Thus, the lower incidence of osteoarthritis in our study population may reflect current evidence-based practice and a contemporary approach to patient selection.