User login

Evidence-based medicine: It’s not a cookbook!

The term evidence-based medicine (EBM) has been derided by some as “cookbook medicine.” To others, EBM conjures up the efforts of describing interventions in terms of comparative effectiveness, drowning us in a deluge of “evidence-based” publications. The moniker has also been hijacked by companies to name their Health Economics and Outcomes research divisions. The spirit behind EBM is getting lost. EBM is not just about the evidence; it is about how we use it.1

In this commentary, we describe the concept of EBM and discuss teaching EBM to medical students and residents, its role in continuing medical education, and how it may be applied to practice, using a case scenario as a guide.

What is evidence-based medicine?

Sackett et al2 summed it best in an editorial published in the BMJ in 1996, where he emphasized decision-making in the care of individual patients. When making clinical decisions, using the best evidence available makes sense, but so does integrating individual clinical expertise and considering the individual patient’s preferences. Sackett et al2 warns about practice becoming tyrannized by evidence: “even excellent external evidence may be inapplicable to or inappropriate for an individual patient.” Clearly, EBM is not cookbook medicine.

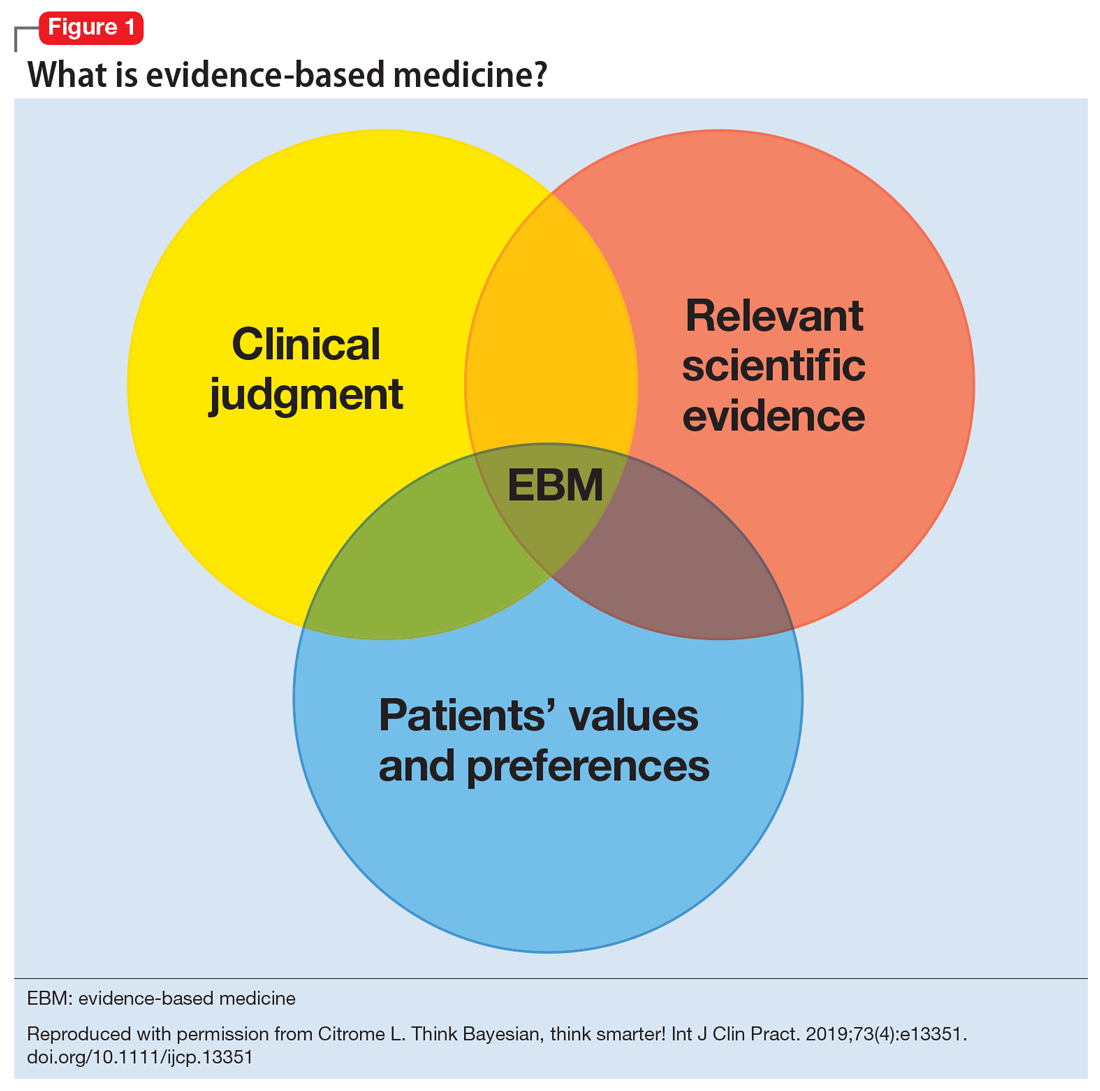

Figure 13 illustrates EBM as the confluence of clinical judgment, relevant scientific evidence, and patients’ values and preferences. The results from a clinical trial are only one part of the equation. As practitioners, we have the advantage of detailed knowledge about the patient, and our decisions are not “one size fits all.” Prior information about the patient dictates how we apply the evidence that supports potential interventions.

The concept of EBM was born out of necessity to bring scientific principles into the heart of medicine. As outlined by Sackett,4 the practice of EBM is a process of lifelong, self-directed learning in which caring for our own patients creates the need for clinically important information about diagnosis, prognosis, therapy, and other clinical and health care issues. Through EBM, we:

- convert these information needs into answerable questions

- track down, with maximum efficiency, the best evidence with which to answer questions (whether from clinical examination, diagnostic laboratory results, research evidence, or other sources)

- critically appraise that evidence for its validity (closeness to the truth) and usefulness (clinical applicability)

- integrate this appraisal with our clinical expertise and apply it in practice

- evaluate our performance.

Over the years, the original aim of EBM as a self-directed method for clinicians to practice high-quality medicine was morphed by some into a tool of enforced standardization and a boilerplate approach to managing costs across systems of care. As a result, the term EBM has been criticized because of:

- its reliance on empiricism

- a narrow definition of evidence

- a lack of evidence of efficacy

- its limited usefulness for individual patients

- threats to the autonomy of the doctor-patient relationship.

These 5 categories are associated with severe drawbacks when used for individual patient care.5 In addition to problems with applying standardized population research to a specific patient with a specific set of symptoms, medications, genetic variations, and unique environment, it can take years for clinicians to change their practices to incorporate new information.6

Continue to: Evidence that is too narrow...

Evidence that is too narrow in scope may not be useful. Single-molecule pharmaceutical clinical trials have erroneously become a synonym of EBM. Such studies do not reflect complex, real-life situations. Based on such studies, FDA product labeling can be inadequate in its guidance, particularly when faced with complex comorbidities. The standard comparison of active treatment to placebo is also seen as EBM, narrowing its scope and deflecting from clinical medicine when physicians measure one treatment’s success against another vs measuring real treatments against shams. Real-life treatment choice is frequently based on considering adverse effects as important to consider as therapeutic efficacy; however, this concept is outside of the common (mis)understanding of EBM.

Conflicting and ever-changing data and the push to replace clinical thinking with general dogmas trivializes medical practice and endangers treatment outcomes. This would not happen to the extent we see now if EBM was again seen as a guide and general direction rather than a blanket, distorted requirement to follow rigid recommendations for specific patients.

Insurance companies have driven a change in the understanding of EBM by using the FDA label as an excuse to deny, delay, and/or refuse to pay for treatments that are not explicitly and narrowly on-label. Dependence on on-label treatments is even more challenging in specialty medicine because primary care clinicians generally have tried the conventional approaches before referring patients to a specialist. However, insurance denials rarely differentiate between practice settings.

Medicolegal issues have cemented the present situation when clinically valid “off-label” treatments may be a reasonable consideration for patients but can place health care practitioners in jeopardy. The distorted EBM doctrine has become a justification for legal actions against clinicians who practice individualized medicine.

Concision bias (selectively focusing on information, losing nuance) and selection bias (patients in clinical trials who do not reflect real-life patients) have become an impediment to progress and EBM as originally intended.

Continue to: Training medical students and residents

Training medical students and residents

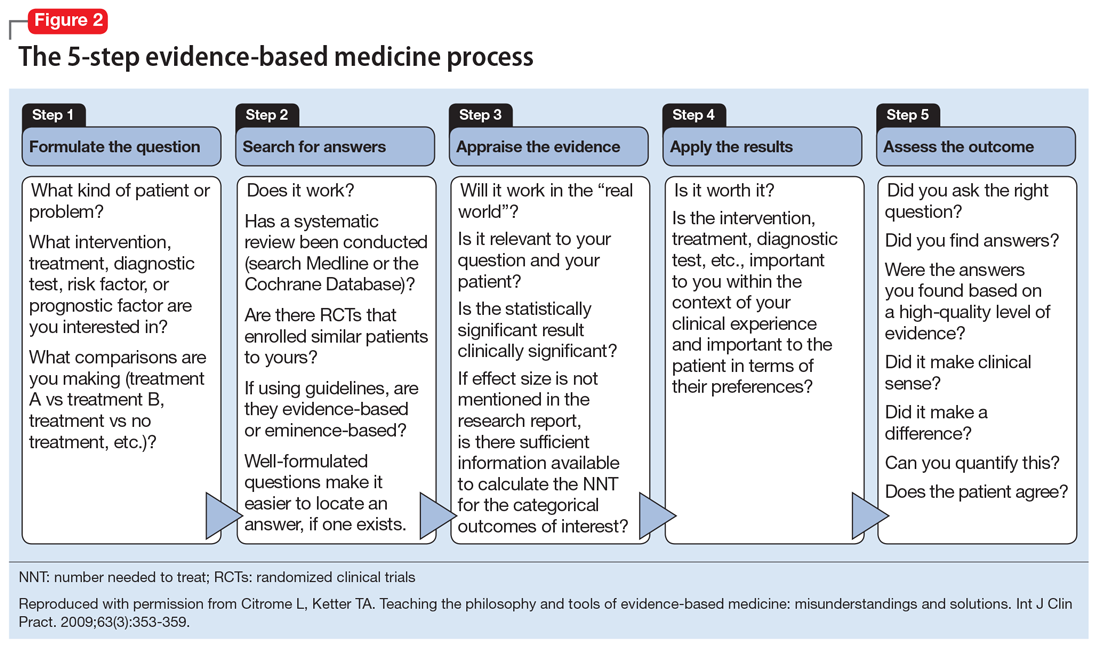

Although there is some variation in how EBM is taught to medical students and residents,7,8 the expectation is that such education occurs. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirements for a residency program state that “the program must advance residents’ knowledge and practice of the scholarly approach to evidence-based patient care.”9 The topic has been part of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology Model Psychopharmacology Curriculum, but only in an optional lecture.10 The formal teaching of EBM includes how to find relevant biomedical publications for the clinical issues at hand, understand the different hierarchies of evidence, interpret results in terms of effect size, and apply this knowledge in the care of patients. This 5-step process is illustrated in Figure 28. See Related Resources for 3 books that provide a scholarly yet clinically relevant approach to EBM.

Continuing medical education

Most

Practical applications

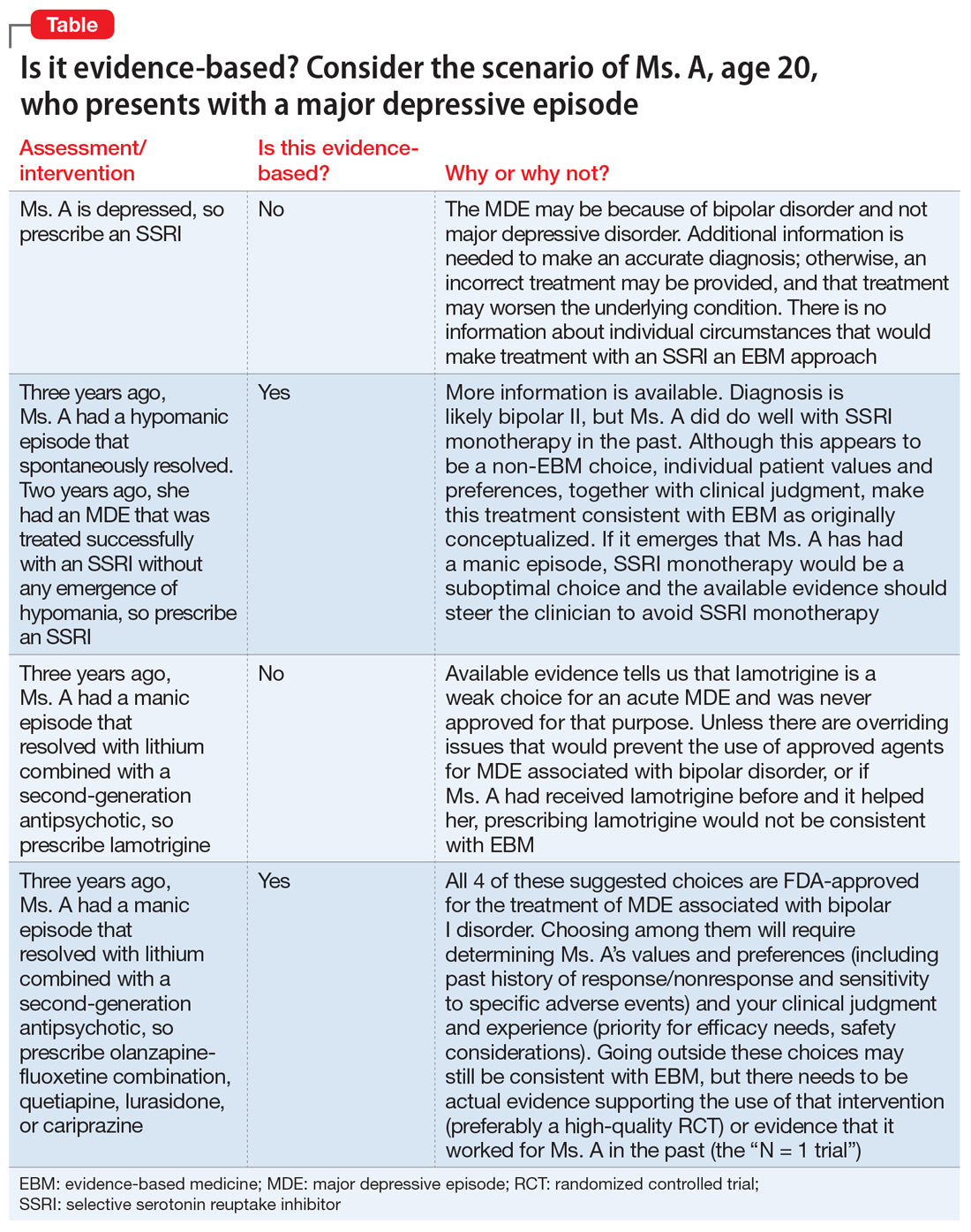

There are common clinical scenarios where evidence is ignored, or where it is overvalued. For example, the treatment of bipolar depression can be made worse with the use of antidepressants.14 Does this mean that antidepressants should never be used? What about patient history and preference? What if the approved agents fail to relieve symptoms or are not well tolerated? Available FDA-approved choices may not always be suitable.15 The Table illustrates some of these scenarios.

1. Citrome L. Evidence-based medicine: it’s not just about the evidence. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65(6):634-635.

2. Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312(7023):71.

3. Citrome L. Think Bayesian, think smarter! Int J Clin Pract. 2019;73(4):e13351. doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.13351

4. Sackett DL. Evidence-based medicine. Semin Perinatol. 1997;21(1):3-5.

5. Cohen AM, Stavri PZ, Hersh WR. A categorization and analysis of the criticisms of evidence-based medicine. Int J Med Inform. 2004;73(1):35-43.

6. Dutton DB. Worse than the disease: pitfalls of medical progress. Cambridge University Press; 1988.

7. Maggio LA. Educating physicians in evidence based medicine: current practices and curricular strategies. Perspect Med Educ. 2016;5(6):358-361.

8. Citrome L, Ketter TA. Teaching the philosophy and tools of evidence-based medicine: misunderstandings and solutions. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63(3):353-359.

9. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Common Program Requirements (Residency). Revised February 3, 2020. Accessed March 30, 2021. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRResidency2020.pdf

10. Citrome L, Ellison JM. Show me the evidence! Understanding the philosophy of evidence-based medicine and interpreting clinical trials. In: Glick ID, Macaluso M (Chair, Co-chair). ASCP model psychopharmacology curriculum for training directors and teachers of psychopharmacology in psychiatric residency programs, 10th ed. American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology; 2019.

11. Citrome L. Interpreting and applying the CATIE results: with CATIE, context is key, when sorting out Phases 1, 1A, 1B, 2E, and 2T. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2007;4(10):23-29.

12. Citrome L, Stroup TS. Schizophrenia, clinical antipsychotic trials of intervention effectiveness (CATIE) and number needed to treat: how can CATIE inform clinicians? Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60(8):933-940. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01044.x

13. Citrome L. Dissecting clinical trials with ‘number needed to treat’. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):66-71.

14. Goldberg JF, Freeman MP, Balon R, et al. The American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology survey of psychopharmacologists’ practice patterns for the treatment of mood disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(8):605-613.

15. Citrome L. Food and Drug Administration-approved treatments for acute bipolar depression: what we have and what we need. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;40(4):334-338.

The term evidence-based medicine (EBM) has been derided by some as “cookbook medicine.” To others, EBM conjures up the efforts of describing interventions in terms of comparative effectiveness, drowning us in a deluge of “evidence-based” publications. The moniker has also been hijacked by companies to name their Health Economics and Outcomes research divisions. The spirit behind EBM is getting lost. EBM is not just about the evidence; it is about how we use it.1

In this commentary, we describe the concept of EBM and discuss teaching EBM to medical students and residents, its role in continuing medical education, and how it may be applied to practice, using a case scenario as a guide.

What is evidence-based medicine?

Sackett et al2 summed it best in an editorial published in the BMJ in 1996, where he emphasized decision-making in the care of individual patients. When making clinical decisions, using the best evidence available makes sense, but so does integrating individual clinical expertise and considering the individual patient’s preferences. Sackett et al2 warns about practice becoming tyrannized by evidence: “even excellent external evidence may be inapplicable to or inappropriate for an individual patient.” Clearly, EBM is not cookbook medicine.

Figure 13 illustrates EBM as the confluence of clinical judgment, relevant scientific evidence, and patients’ values and preferences. The results from a clinical trial are only one part of the equation. As practitioners, we have the advantage of detailed knowledge about the patient, and our decisions are not “one size fits all.” Prior information about the patient dictates how we apply the evidence that supports potential interventions.

The concept of EBM was born out of necessity to bring scientific principles into the heart of medicine. As outlined by Sackett,4 the practice of EBM is a process of lifelong, self-directed learning in which caring for our own patients creates the need for clinically important information about diagnosis, prognosis, therapy, and other clinical and health care issues. Through EBM, we:

- convert these information needs into answerable questions

- track down, with maximum efficiency, the best evidence with which to answer questions (whether from clinical examination, diagnostic laboratory results, research evidence, or other sources)

- critically appraise that evidence for its validity (closeness to the truth) and usefulness (clinical applicability)

- integrate this appraisal with our clinical expertise and apply it in practice

- evaluate our performance.

Over the years, the original aim of EBM as a self-directed method for clinicians to practice high-quality medicine was morphed by some into a tool of enforced standardization and a boilerplate approach to managing costs across systems of care. As a result, the term EBM has been criticized because of:

- its reliance on empiricism

- a narrow definition of evidence

- a lack of evidence of efficacy

- its limited usefulness for individual patients

- threats to the autonomy of the doctor-patient relationship.

These 5 categories are associated with severe drawbacks when used for individual patient care.5 In addition to problems with applying standardized population research to a specific patient with a specific set of symptoms, medications, genetic variations, and unique environment, it can take years for clinicians to change their practices to incorporate new information.6

Continue to: Evidence that is too narrow...

Evidence that is too narrow in scope may not be useful. Single-molecule pharmaceutical clinical trials have erroneously become a synonym of EBM. Such studies do not reflect complex, real-life situations. Based on such studies, FDA product labeling can be inadequate in its guidance, particularly when faced with complex comorbidities. The standard comparison of active treatment to placebo is also seen as EBM, narrowing its scope and deflecting from clinical medicine when physicians measure one treatment’s success against another vs measuring real treatments against shams. Real-life treatment choice is frequently based on considering adverse effects as important to consider as therapeutic efficacy; however, this concept is outside of the common (mis)understanding of EBM.

Conflicting and ever-changing data and the push to replace clinical thinking with general dogmas trivializes medical practice and endangers treatment outcomes. This would not happen to the extent we see now if EBM was again seen as a guide and general direction rather than a blanket, distorted requirement to follow rigid recommendations for specific patients.

Insurance companies have driven a change in the understanding of EBM by using the FDA label as an excuse to deny, delay, and/or refuse to pay for treatments that are not explicitly and narrowly on-label. Dependence on on-label treatments is even more challenging in specialty medicine because primary care clinicians generally have tried the conventional approaches before referring patients to a specialist. However, insurance denials rarely differentiate between practice settings.

Medicolegal issues have cemented the present situation when clinically valid “off-label” treatments may be a reasonable consideration for patients but can place health care practitioners in jeopardy. The distorted EBM doctrine has become a justification for legal actions against clinicians who practice individualized medicine.

Concision bias (selectively focusing on information, losing nuance) and selection bias (patients in clinical trials who do not reflect real-life patients) have become an impediment to progress and EBM as originally intended.

Continue to: Training medical students and residents

Training medical students and residents

Although there is some variation in how EBM is taught to medical students and residents,7,8 the expectation is that such education occurs. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirements for a residency program state that “the program must advance residents’ knowledge and practice of the scholarly approach to evidence-based patient care.”9 The topic has been part of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology Model Psychopharmacology Curriculum, but only in an optional lecture.10 The formal teaching of EBM includes how to find relevant biomedical publications for the clinical issues at hand, understand the different hierarchies of evidence, interpret results in terms of effect size, and apply this knowledge in the care of patients. This 5-step process is illustrated in Figure 28. See Related Resources for 3 books that provide a scholarly yet clinically relevant approach to EBM.

Continuing medical education

Most

Practical applications

There are common clinical scenarios where evidence is ignored, or where it is overvalued. For example, the treatment of bipolar depression can be made worse with the use of antidepressants.14 Does this mean that antidepressants should never be used? What about patient history and preference? What if the approved agents fail to relieve symptoms or are not well tolerated? Available FDA-approved choices may not always be suitable.15 The Table illustrates some of these scenarios.

The term evidence-based medicine (EBM) has been derided by some as “cookbook medicine.” To others, EBM conjures up the efforts of describing interventions in terms of comparative effectiveness, drowning us in a deluge of “evidence-based” publications. The moniker has also been hijacked by companies to name their Health Economics and Outcomes research divisions. The spirit behind EBM is getting lost. EBM is not just about the evidence; it is about how we use it.1

In this commentary, we describe the concept of EBM and discuss teaching EBM to medical students and residents, its role in continuing medical education, and how it may be applied to practice, using a case scenario as a guide.

What is evidence-based medicine?

Sackett et al2 summed it best in an editorial published in the BMJ in 1996, where he emphasized decision-making in the care of individual patients. When making clinical decisions, using the best evidence available makes sense, but so does integrating individual clinical expertise and considering the individual patient’s preferences. Sackett et al2 warns about practice becoming tyrannized by evidence: “even excellent external evidence may be inapplicable to or inappropriate for an individual patient.” Clearly, EBM is not cookbook medicine.

Figure 13 illustrates EBM as the confluence of clinical judgment, relevant scientific evidence, and patients’ values and preferences. The results from a clinical trial are only one part of the equation. As practitioners, we have the advantage of detailed knowledge about the patient, and our decisions are not “one size fits all.” Prior information about the patient dictates how we apply the evidence that supports potential interventions.

The concept of EBM was born out of necessity to bring scientific principles into the heart of medicine. As outlined by Sackett,4 the practice of EBM is a process of lifelong, self-directed learning in which caring for our own patients creates the need for clinically important information about diagnosis, prognosis, therapy, and other clinical and health care issues. Through EBM, we:

- convert these information needs into answerable questions

- track down, with maximum efficiency, the best evidence with which to answer questions (whether from clinical examination, diagnostic laboratory results, research evidence, or other sources)

- critically appraise that evidence for its validity (closeness to the truth) and usefulness (clinical applicability)

- integrate this appraisal with our clinical expertise and apply it in practice

- evaluate our performance.

Over the years, the original aim of EBM as a self-directed method for clinicians to practice high-quality medicine was morphed by some into a tool of enforced standardization and a boilerplate approach to managing costs across systems of care. As a result, the term EBM has been criticized because of:

- its reliance on empiricism

- a narrow definition of evidence

- a lack of evidence of efficacy

- its limited usefulness for individual patients

- threats to the autonomy of the doctor-patient relationship.

These 5 categories are associated with severe drawbacks when used for individual patient care.5 In addition to problems with applying standardized population research to a specific patient with a specific set of symptoms, medications, genetic variations, and unique environment, it can take years for clinicians to change their practices to incorporate new information.6

Continue to: Evidence that is too narrow...

Evidence that is too narrow in scope may not be useful. Single-molecule pharmaceutical clinical trials have erroneously become a synonym of EBM. Such studies do not reflect complex, real-life situations. Based on such studies, FDA product labeling can be inadequate in its guidance, particularly when faced with complex comorbidities. The standard comparison of active treatment to placebo is also seen as EBM, narrowing its scope and deflecting from clinical medicine when physicians measure one treatment’s success against another vs measuring real treatments against shams. Real-life treatment choice is frequently based on considering adverse effects as important to consider as therapeutic efficacy; however, this concept is outside of the common (mis)understanding of EBM.

Conflicting and ever-changing data and the push to replace clinical thinking with general dogmas trivializes medical practice and endangers treatment outcomes. This would not happen to the extent we see now if EBM was again seen as a guide and general direction rather than a blanket, distorted requirement to follow rigid recommendations for specific patients.

Insurance companies have driven a change in the understanding of EBM by using the FDA label as an excuse to deny, delay, and/or refuse to pay for treatments that are not explicitly and narrowly on-label. Dependence on on-label treatments is even more challenging in specialty medicine because primary care clinicians generally have tried the conventional approaches before referring patients to a specialist. However, insurance denials rarely differentiate between practice settings.

Medicolegal issues have cemented the present situation when clinically valid “off-label” treatments may be a reasonable consideration for patients but can place health care practitioners in jeopardy. The distorted EBM doctrine has become a justification for legal actions against clinicians who practice individualized medicine.

Concision bias (selectively focusing on information, losing nuance) and selection bias (patients in clinical trials who do not reflect real-life patients) have become an impediment to progress and EBM as originally intended.

Continue to: Training medical students and residents

Training medical students and residents

Although there is some variation in how EBM is taught to medical students and residents,7,8 the expectation is that such education occurs. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirements for a residency program state that “the program must advance residents’ knowledge and practice of the scholarly approach to evidence-based patient care.”9 The topic has been part of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology Model Psychopharmacology Curriculum, but only in an optional lecture.10 The formal teaching of EBM includes how to find relevant biomedical publications for the clinical issues at hand, understand the different hierarchies of evidence, interpret results in terms of effect size, and apply this knowledge in the care of patients. This 5-step process is illustrated in Figure 28. See Related Resources for 3 books that provide a scholarly yet clinically relevant approach to EBM.

Continuing medical education

Most

Practical applications

There are common clinical scenarios where evidence is ignored, or where it is overvalued. For example, the treatment of bipolar depression can be made worse with the use of antidepressants.14 Does this mean that antidepressants should never be used? What about patient history and preference? What if the approved agents fail to relieve symptoms or are not well tolerated? Available FDA-approved choices may not always be suitable.15 The Table illustrates some of these scenarios.

1. Citrome L. Evidence-based medicine: it’s not just about the evidence. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65(6):634-635.

2. Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312(7023):71.

3. Citrome L. Think Bayesian, think smarter! Int J Clin Pract. 2019;73(4):e13351. doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.13351

4. Sackett DL. Evidence-based medicine. Semin Perinatol. 1997;21(1):3-5.

5. Cohen AM, Stavri PZ, Hersh WR. A categorization and analysis of the criticisms of evidence-based medicine. Int J Med Inform. 2004;73(1):35-43.

6. Dutton DB. Worse than the disease: pitfalls of medical progress. Cambridge University Press; 1988.

7. Maggio LA. Educating physicians in evidence based medicine: current practices and curricular strategies. Perspect Med Educ. 2016;5(6):358-361.

8. Citrome L, Ketter TA. Teaching the philosophy and tools of evidence-based medicine: misunderstandings and solutions. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63(3):353-359.

9. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Common Program Requirements (Residency). Revised February 3, 2020. Accessed March 30, 2021. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRResidency2020.pdf

10. Citrome L, Ellison JM. Show me the evidence! Understanding the philosophy of evidence-based medicine and interpreting clinical trials. In: Glick ID, Macaluso M (Chair, Co-chair). ASCP model psychopharmacology curriculum for training directors and teachers of psychopharmacology in psychiatric residency programs, 10th ed. American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology; 2019.

11. Citrome L. Interpreting and applying the CATIE results: with CATIE, context is key, when sorting out Phases 1, 1A, 1B, 2E, and 2T. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2007;4(10):23-29.

12. Citrome L, Stroup TS. Schizophrenia, clinical antipsychotic trials of intervention effectiveness (CATIE) and number needed to treat: how can CATIE inform clinicians? Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60(8):933-940. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01044.x

13. Citrome L. Dissecting clinical trials with ‘number needed to treat’. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):66-71.

14. Goldberg JF, Freeman MP, Balon R, et al. The American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology survey of psychopharmacologists’ practice patterns for the treatment of mood disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(8):605-613.

15. Citrome L. Food and Drug Administration-approved treatments for acute bipolar depression: what we have and what we need. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;40(4):334-338.

1. Citrome L. Evidence-based medicine: it’s not just about the evidence. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65(6):634-635.

2. Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312(7023):71.

3. Citrome L. Think Bayesian, think smarter! Int J Clin Pract. 2019;73(4):e13351. doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.13351

4. Sackett DL. Evidence-based medicine. Semin Perinatol. 1997;21(1):3-5.

5. Cohen AM, Stavri PZ, Hersh WR. A categorization and analysis of the criticisms of evidence-based medicine. Int J Med Inform. 2004;73(1):35-43.

6. Dutton DB. Worse than the disease: pitfalls of medical progress. Cambridge University Press; 1988.

7. Maggio LA. Educating physicians in evidence based medicine: current practices and curricular strategies. Perspect Med Educ. 2016;5(6):358-361.

8. Citrome L, Ketter TA. Teaching the philosophy and tools of evidence-based medicine: misunderstandings and solutions. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63(3):353-359.

9. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Common Program Requirements (Residency). Revised February 3, 2020. Accessed March 30, 2021. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRResidency2020.pdf

10. Citrome L, Ellison JM. Show me the evidence! Understanding the philosophy of evidence-based medicine and interpreting clinical trials. In: Glick ID, Macaluso M (Chair, Co-chair). ASCP model psychopharmacology curriculum for training directors and teachers of psychopharmacology in psychiatric residency programs, 10th ed. American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology; 2019.

11. Citrome L. Interpreting and applying the CATIE results: with CATIE, context is key, when sorting out Phases 1, 1A, 1B, 2E, and 2T. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2007;4(10):23-29.

12. Citrome L, Stroup TS. Schizophrenia, clinical antipsychotic trials of intervention effectiveness (CATIE) and number needed to treat: how can CATIE inform clinicians? Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60(8):933-940. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01044.x

13. Citrome L. Dissecting clinical trials with ‘number needed to treat’. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):66-71.

14. Goldberg JF, Freeman MP, Balon R, et al. The American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology survey of psychopharmacologists’ practice patterns for the treatment of mood disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(8):605-613.

15. Citrome L. Food and Drug Administration-approved treatments for acute bipolar depression: what we have and what we need. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;40(4):334-338.

Changes in patient behavior during COVID-19: What I’ve observed

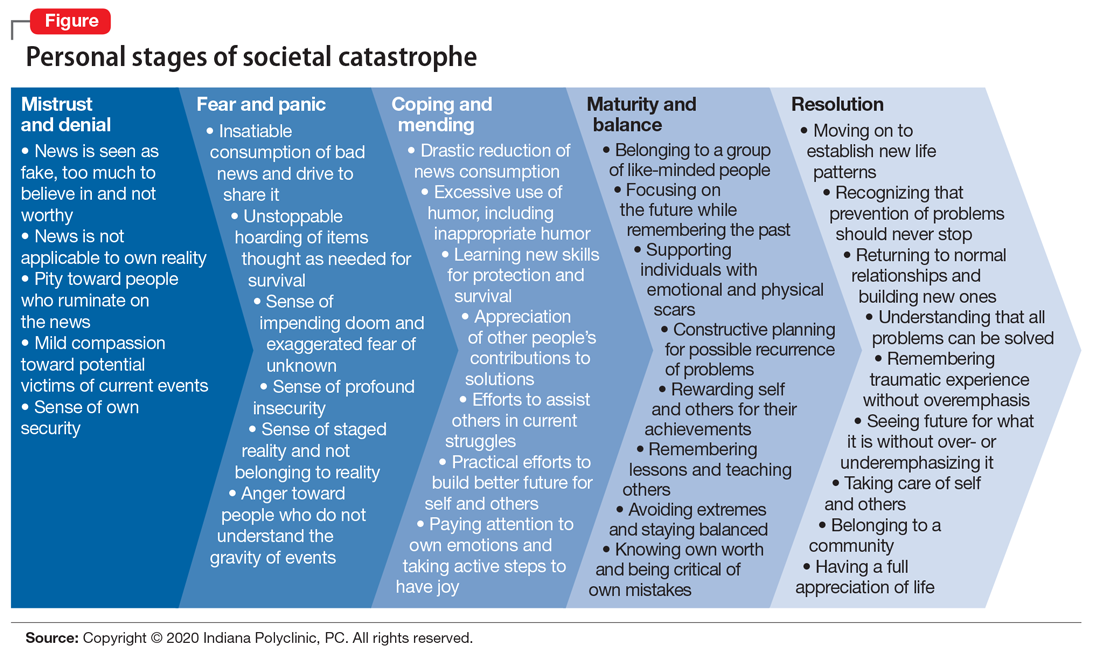

Unprecedented circumstances, extraordinary times, continental shift, life-altering experience—the descriptions of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic have been endless, and accurate. Every clinician who has cared for patients during these trying times has noticed new patterns in patient behavior. Psychiatrists are acutely aware of the emotional, behavioral, and cognitive methods that patients are using to protect themselves from the chaos around them, and the ways in which they process a societal catastrophe such as COVID-19 (Figure). Here are some new patterns I have noticed among my own patients.

Physical and emotional separation

I first noticed the changes in my patients’ behavior at the front desk, where they now spend less time talking with the staff. They bring their own pens for filling out the paperwork, avoid touching items around them, and try to keep social interactions brief and to the point. Patients have been more cooperative about scheduling and rescheduling their appointments. They have generally been nicer to the staff, frequently thanking us for the work we do, and verbalizing their support for health care professionals in general.

Patients have been more supportive of their family members and other patients in the clinic, with some noticeable exceptions, such as maintaining social distancing for their own comfort and safety. Some patients wear face masks not just for safety but also to separate themselves and hide their emotions from the world. This allows them to feel more emotionally secure when interacting with other people.

The use of telehealth has given many patients the security of not having to leave their home, and the decreased need for travel adds to their comfort.

Changes I didn’t expect

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in some unexpected changes in my patients. Only a minority of my patients have expressed increased anxiety, while most have become less anxious overall on issues other than the pandemic. Many of my patients who have stressful jobs, especially teachers, say they feel more comfortable working from home and have less anxiety and depression because they are removed from their daily stressors. There also has been an increase in patients’ use of humor, including inappropriate humor, to defend against their fear of COVID-19.

Our clinic is a multidisciplinary facility that specializes in integrating mental and physical health treatments for pain, and for some patients, increased anxiety is clearly associated with an increase in pain. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, patients have recognized this connection and verbalized their concerns. Some somatic patients have had a decrease in their physical symptoms, including chronic pain, because they see that the whole world is not well, which somehow helps to validate their concerns.

The changes in our patients’ psychological well-being will likely continue to morph as we enter a more stable period. The eventual resolution of the pandemic will bring further changes to our patients’ emotional lives. As we go through these times together, we will continue to uncover new ways that our patients will use to defend themselves against stress and adversities.

Unprecedented circumstances, extraordinary times, continental shift, life-altering experience—the descriptions of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic have been endless, and accurate. Every clinician who has cared for patients during these trying times has noticed new patterns in patient behavior. Psychiatrists are acutely aware of the emotional, behavioral, and cognitive methods that patients are using to protect themselves from the chaos around them, and the ways in which they process a societal catastrophe such as COVID-19 (Figure). Here are some new patterns I have noticed among my own patients.

Physical and emotional separation

I first noticed the changes in my patients’ behavior at the front desk, where they now spend less time talking with the staff. They bring their own pens for filling out the paperwork, avoid touching items around them, and try to keep social interactions brief and to the point. Patients have been more cooperative about scheduling and rescheduling their appointments. They have generally been nicer to the staff, frequently thanking us for the work we do, and verbalizing their support for health care professionals in general.

Patients have been more supportive of their family members and other patients in the clinic, with some noticeable exceptions, such as maintaining social distancing for their own comfort and safety. Some patients wear face masks not just for safety but also to separate themselves and hide their emotions from the world. This allows them to feel more emotionally secure when interacting with other people.

The use of telehealth has given many patients the security of not having to leave their home, and the decreased need for travel adds to their comfort.

Changes I didn’t expect

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in some unexpected changes in my patients. Only a minority of my patients have expressed increased anxiety, while most have become less anxious overall on issues other than the pandemic. Many of my patients who have stressful jobs, especially teachers, say they feel more comfortable working from home and have less anxiety and depression because they are removed from their daily stressors. There also has been an increase in patients’ use of humor, including inappropriate humor, to defend against their fear of COVID-19.

Our clinic is a multidisciplinary facility that specializes in integrating mental and physical health treatments for pain, and for some patients, increased anxiety is clearly associated with an increase in pain. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, patients have recognized this connection and verbalized their concerns. Some somatic patients have had a decrease in their physical symptoms, including chronic pain, because they see that the whole world is not well, which somehow helps to validate their concerns.

The changes in our patients’ psychological well-being will likely continue to morph as we enter a more stable period. The eventual resolution of the pandemic will bring further changes to our patients’ emotional lives. As we go through these times together, we will continue to uncover new ways that our patients will use to defend themselves against stress and adversities.

Unprecedented circumstances, extraordinary times, continental shift, life-altering experience—the descriptions of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic have been endless, and accurate. Every clinician who has cared for patients during these trying times has noticed new patterns in patient behavior. Psychiatrists are acutely aware of the emotional, behavioral, and cognitive methods that patients are using to protect themselves from the chaos around them, and the ways in which they process a societal catastrophe such as COVID-19 (Figure). Here are some new patterns I have noticed among my own patients.

Physical and emotional separation

I first noticed the changes in my patients’ behavior at the front desk, where they now spend less time talking with the staff. They bring their own pens for filling out the paperwork, avoid touching items around them, and try to keep social interactions brief and to the point. Patients have been more cooperative about scheduling and rescheduling their appointments. They have generally been nicer to the staff, frequently thanking us for the work we do, and verbalizing their support for health care professionals in general.

Patients have been more supportive of their family members and other patients in the clinic, with some noticeable exceptions, such as maintaining social distancing for their own comfort and safety. Some patients wear face masks not just for safety but also to separate themselves and hide their emotions from the world. This allows them to feel more emotionally secure when interacting with other people.

The use of telehealth has given many patients the security of not having to leave their home, and the decreased need for travel adds to their comfort.

Changes I didn’t expect

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in some unexpected changes in my patients. Only a minority of my patients have expressed increased anxiety, while most have become less anxious overall on issues other than the pandemic. Many of my patients who have stressful jobs, especially teachers, say they feel more comfortable working from home and have less anxiety and depression because they are removed from their daily stressors. There also has been an increase in patients’ use of humor, including inappropriate humor, to defend against their fear of COVID-19.

Our clinic is a multidisciplinary facility that specializes in integrating mental and physical health treatments for pain, and for some patients, increased anxiety is clearly associated with an increase in pain. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, patients have recognized this connection and verbalized their concerns. Some somatic patients have had a decrease in their physical symptoms, including chronic pain, because they see that the whole world is not well, which somehow helps to validate their concerns.

The changes in our patients’ psychological well-being will likely continue to morph as we enter a more stable period. The eventual resolution of the pandemic will bring further changes to our patients’ emotional lives. As we go through these times together, we will continue to uncover new ways that our patients will use to defend themselves against stress and adversities.