User login

Ascending Erythematous Nodules on the Arm

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Nocardiosis

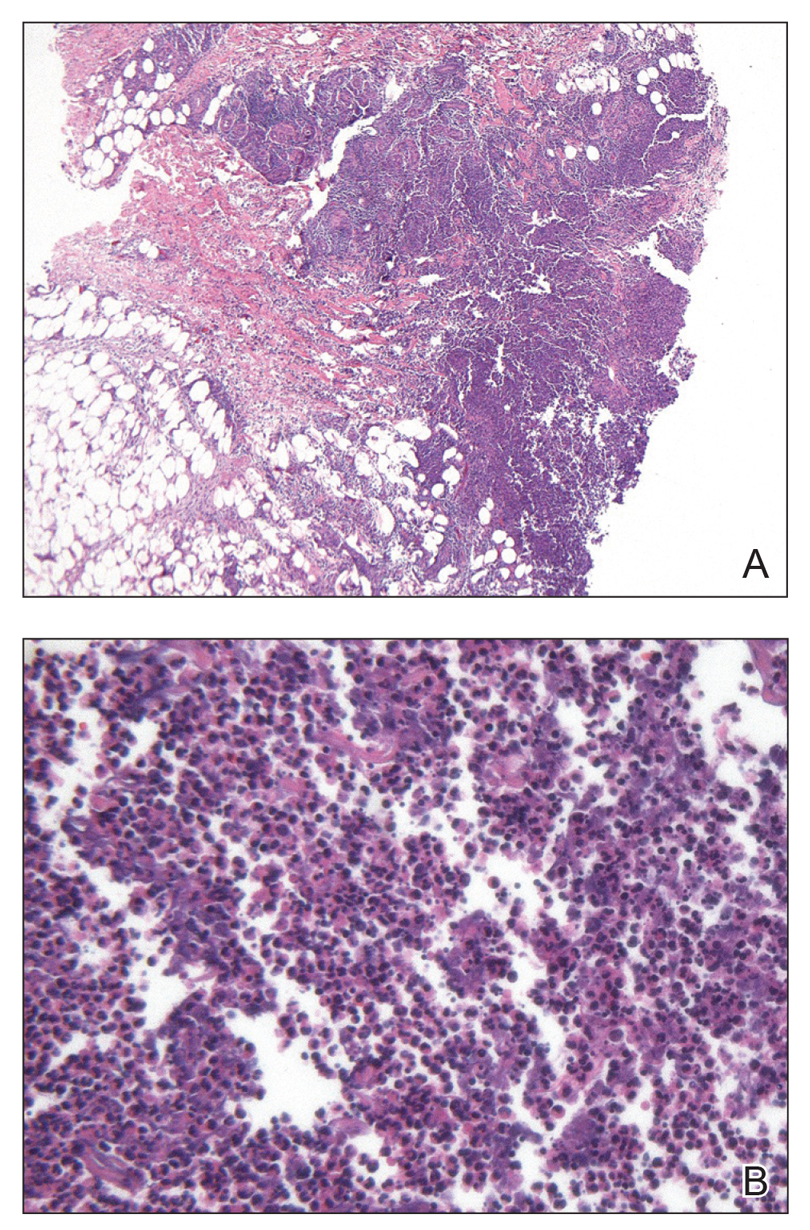

Comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood cell count were unremarkable; human immunodeficiency virus screening was nonreactive. Punch biopsies were obtained for histopathology, as well as bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures. Histopathologic examination of a 4-mm punch biopsy of the forearm nodule showed a dermal abscess with neutrophilic infiltration in the dermis (Figure 1). No organisms were seen on Gram, methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, or acid-fast bacteria stains. Given the clinical suspicion for lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis, the patient was started on itraconazole. She reported modest improvement but subsequently developed a morbilliform eruption necessitating medication discontinuation.

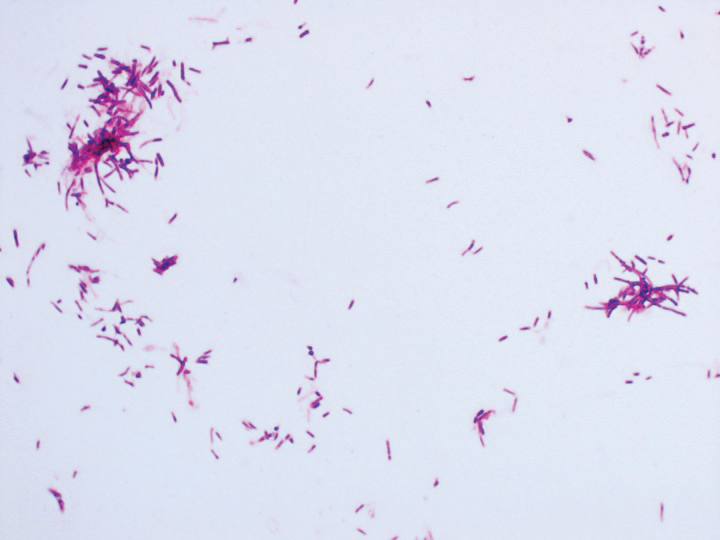

Eighteen days after obtaining the tissue culture, acid-fast organisms grew in culture. These organisms were subcultured on Middlebrook 7H11 agar (Sigma-Aldrich) with growth noted at 30°C and 37°C. Gram stain revealed filamentous gram-variable bacteria (Figure 2) that were identified as Nocardia brasiliensis by 16S ribosomal DNA analysis. Given the patient’s sulfonamide allergy, she started oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily. She responded to the therapy and subsequent testing confirmed susceptibility.

Nocardia brasiliensis, isolated from subculture on Gram stain (original

magnification ×1000).

The genus Nocardia consists of more than 50 species of gram-positive, weakly acid-fast, aerobic actinomycetes that can cause primary cutaneous infection via percutaneous inoculation. Nocardia brasiliensis is the leading cause (approximately 80% of cases) of primary cutaneous or subcutaneous nocardiosis and is found ubiquitously in soil and decaying vegetation.1 The clinical presentation varies, rendering definitive diagnosis a challenge without histopathologic and microbiologic testing.2 Patients presenting with nocardial cellulitis often are suspected to have Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus infections. The differential diagnosis for patients presenting with nocardial nodular lymphangitis, also known as lymphocutaneous syndrome, includes atypical mycobacterial infections, leishmaniasis, and lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis.2

Histologic examination of nocardial nodules typically shows granulomatous or neutrophilic inflammation, and organisms may appear in small collections resembling sulfur granules.2 The organism itself is weakly positive on acid-fast stain, and useful stains include acid-fast bacteria, methenamine silver, and periodic acid–Schiff.2 Tissue culture often provides the definitive diagnosis, as the histology is nonspecific and organisms may not be visualized.

Oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 2.5 to 10 mg/kg and 12.5 to 50 mg/kg, respectively, twice daily is the treatment of choice for primary cutaneous nocardiosis. Minocycline 100 to 200 mg twice daily is an accepted alternative in case of sulfonamide allergy, as in our patient. Antibiotics should be tailored according to the susceptibility profile of the isolated organism.3

This case highlights the importance of forming a broad differential diagnosis for patients presenting with lymphocutaneous syndrome. The incidence and prevalence of N brasiliensis infection is difficult to determine due to its nonspecific clinical presentation and a lack of recent epidemiologic studies. Although primary cutaneous nocardiosis in the United States often is diagnosed in the South or Southwest, cases have been reported in other regions.4-6 Traumatic inoculation of contaminated soil, plants, and other organic matter, a well-known method of Sporothrix schenckii transmission, also is a method of N brasiliensis transmission. Because this organism may not be detected on histologic examination, empiric treatment should be considered if the diagnosis is suspected.

1. Brown-Eliot BA, Brown JM, Conville PS, et al. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:259-282.

2. Smego RA Jr, Castiglia M, Asperilla MO. Lymphocutaneous syndrome: a review of non-sporothrix causes. Medicine. 1999;78:38-63.

3. Lerner P. Nocardiosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:891-903.

4. Smego RA Jr, Gallis HA. The clinical spectrum of Nocardia brasiliensis infection in the United States. Rev Infect Dis. 1984;6:164-180.

5. Fukuda H, Saotome A, Usami N, et al. Lymphocutaneous type of nocardiosis caused by Nocardia brasiliensis: a case report and review of primary cutaneous nocardiosis caused by N. brasiliensis reported in Japan. J Dermatol. 2008;35:346-353.

6. Kil EH, Tsai CL, Kwark EH, et al. A case of nocardiosis with an uncharacteristically long incubation period. Cutis. 2005;76:33-36.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Nocardiosis

Comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood cell count were unremarkable; human immunodeficiency virus screening was nonreactive. Punch biopsies were obtained for histopathology, as well as bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures. Histopathologic examination of a 4-mm punch biopsy of the forearm nodule showed a dermal abscess with neutrophilic infiltration in the dermis (Figure 1). No organisms were seen on Gram, methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, or acid-fast bacteria stains. Given the clinical suspicion for lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis, the patient was started on itraconazole. She reported modest improvement but subsequently developed a morbilliform eruption necessitating medication discontinuation.

Eighteen days after obtaining the tissue culture, acid-fast organisms grew in culture. These organisms were subcultured on Middlebrook 7H11 agar (Sigma-Aldrich) with growth noted at 30°C and 37°C. Gram stain revealed filamentous gram-variable bacteria (Figure 2) that were identified as Nocardia brasiliensis by 16S ribosomal DNA analysis. Given the patient’s sulfonamide allergy, she started oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily. She responded to the therapy and subsequent testing confirmed susceptibility.

Nocardia brasiliensis, isolated from subculture on Gram stain (original

magnification ×1000).

The genus Nocardia consists of more than 50 species of gram-positive, weakly acid-fast, aerobic actinomycetes that can cause primary cutaneous infection via percutaneous inoculation. Nocardia brasiliensis is the leading cause (approximately 80% of cases) of primary cutaneous or subcutaneous nocardiosis and is found ubiquitously in soil and decaying vegetation.1 The clinical presentation varies, rendering definitive diagnosis a challenge without histopathologic and microbiologic testing.2 Patients presenting with nocardial cellulitis often are suspected to have Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus infections. The differential diagnosis for patients presenting with nocardial nodular lymphangitis, also known as lymphocutaneous syndrome, includes atypical mycobacterial infections, leishmaniasis, and lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis.2

Histologic examination of nocardial nodules typically shows granulomatous or neutrophilic inflammation, and organisms may appear in small collections resembling sulfur granules.2 The organism itself is weakly positive on acid-fast stain, and useful stains include acid-fast bacteria, methenamine silver, and periodic acid–Schiff.2 Tissue culture often provides the definitive diagnosis, as the histology is nonspecific and organisms may not be visualized.

Oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 2.5 to 10 mg/kg and 12.5 to 50 mg/kg, respectively, twice daily is the treatment of choice for primary cutaneous nocardiosis. Minocycline 100 to 200 mg twice daily is an accepted alternative in case of sulfonamide allergy, as in our patient. Antibiotics should be tailored according to the susceptibility profile of the isolated organism.3

This case highlights the importance of forming a broad differential diagnosis for patients presenting with lymphocutaneous syndrome. The incidence and prevalence of N brasiliensis infection is difficult to determine due to its nonspecific clinical presentation and a lack of recent epidemiologic studies. Although primary cutaneous nocardiosis in the United States often is diagnosed in the South or Southwest, cases have been reported in other regions.4-6 Traumatic inoculation of contaminated soil, plants, and other organic matter, a well-known method of Sporothrix schenckii transmission, also is a method of N brasiliensis transmission. Because this organism may not be detected on histologic examination, empiric treatment should be considered if the diagnosis is suspected.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Nocardiosis

Comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood cell count were unremarkable; human immunodeficiency virus screening was nonreactive. Punch biopsies were obtained for histopathology, as well as bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures. Histopathologic examination of a 4-mm punch biopsy of the forearm nodule showed a dermal abscess with neutrophilic infiltration in the dermis (Figure 1). No organisms were seen on Gram, methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, or acid-fast bacteria stains. Given the clinical suspicion for lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis, the patient was started on itraconazole. She reported modest improvement but subsequently developed a morbilliform eruption necessitating medication discontinuation.

Eighteen days after obtaining the tissue culture, acid-fast organisms grew in culture. These organisms were subcultured on Middlebrook 7H11 agar (Sigma-Aldrich) with growth noted at 30°C and 37°C. Gram stain revealed filamentous gram-variable bacteria (Figure 2) that were identified as Nocardia brasiliensis by 16S ribosomal DNA analysis. Given the patient’s sulfonamide allergy, she started oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily. She responded to the therapy and subsequent testing confirmed susceptibility.

Nocardia brasiliensis, isolated from subculture on Gram stain (original

magnification ×1000).

The genus Nocardia consists of more than 50 species of gram-positive, weakly acid-fast, aerobic actinomycetes that can cause primary cutaneous infection via percutaneous inoculation. Nocardia brasiliensis is the leading cause (approximately 80% of cases) of primary cutaneous or subcutaneous nocardiosis and is found ubiquitously in soil and decaying vegetation.1 The clinical presentation varies, rendering definitive diagnosis a challenge without histopathologic and microbiologic testing.2 Patients presenting with nocardial cellulitis often are suspected to have Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus infections. The differential diagnosis for patients presenting with nocardial nodular lymphangitis, also known as lymphocutaneous syndrome, includes atypical mycobacterial infections, leishmaniasis, and lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis.2

Histologic examination of nocardial nodules typically shows granulomatous or neutrophilic inflammation, and organisms may appear in small collections resembling sulfur granules.2 The organism itself is weakly positive on acid-fast stain, and useful stains include acid-fast bacteria, methenamine silver, and periodic acid–Schiff.2 Tissue culture often provides the definitive diagnosis, as the histology is nonspecific and organisms may not be visualized.

Oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 2.5 to 10 mg/kg and 12.5 to 50 mg/kg, respectively, twice daily is the treatment of choice for primary cutaneous nocardiosis. Minocycline 100 to 200 mg twice daily is an accepted alternative in case of sulfonamide allergy, as in our patient. Antibiotics should be tailored according to the susceptibility profile of the isolated organism.3

This case highlights the importance of forming a broad differential diagnosis for patients presenting with lymphocutaneous syndrome. The incidence and prevalence of N brasiliensis infection is difficult to determine due to its nonspecific clinical presentation and a lack of recent epidemiologic studies. Although primary cutaneous nocardiosis in the United States often is diagnosed in the South or Southwest, cases have been reported in other regions.4-6 Traumatic inoculation of contaminated soil, plants, and other organic matter, a well-known method of Sporothrix schenckii transmission, also is a method of N brasiliensis transmission. Because this organism may not be detected on histologic examination, empiric treatment should be considered if the diagnosis is suspected.

1. Brown-Eliot BA, Brown JM, Conville PS, et al. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:259-282.

2. Smego RA Jr, Castiglia M, Asperilla MO. Lymphocutaneous syndrome: a review of non-sporothrix causes. Medicine. 1999;78:38-63.

3. Lerner P. Nocardiosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:891-903.

4. Smego RA Jr, Gallis HA. The clinical spectrum of Nocardia brasiliensis infection in the United States. Rev Infect Dis. 1984;6:164-180.

5. Fukuda H, Saotome A, Usami N, et al. Lymphocutaneous type of nocardiosis caused by Nocardia brasiliensis: a case report and review of primary cutaneous nocardiosis caused by N. brasiliensis reported in Japan. J Dermatol. 2008;35:346-353.

6. Kil EH, Tsai CL, Kwark EH, et al. A case of nocardiosis with an uncharacteristically long incubation period. Cutis. 2005;76:33-36.

1. Brown-Eliot BA, Brown JM, Conville PS, et al. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:259-282.

2. Smego RA Jr, Castiglia M, Asperilla MO. Lymphocutaneous syndrome: a review of non-sporothrix causes. Medicine. 1999;78:38-63.

3. Lerner P. Nocardiosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:891-903.

4. Smego RA Jr, Gallis HA. The clinical spectrum of Nocardia brasiliensis infection in the United States. Rev Infect Dis. 1984;6:164-180.

5. Fukuda H, Saotome A, Usami N, et al. Lymphocutaneous type of nocardiosis caused by Nocardia brasiliensis: a case report and review of primary cutaneous nocardiosis caused by N. brasiliensis reported in Japan. J Dermatol. 2008;35:346-353.

6. Kil EH, Tsai CL, Kwark EH, et al. A case of nocardiosis with an uncharacteristically long incubation period. Cutis. 2005;76:33-36.

A 54-year-old woman called her primary care provider to report a painful pink nodule on the left wrist 1 week after sustaining thorn injuries while weeding in her garden. She started cephalexin and noted a pink streak with additional nodules extending up the arm over the next 2 days. She

was admitted to an outside hospital for incision and drainage of the wrist nodule and a 3-day course of intravenous vancomycin. Bacterial culture was negative, and she was discharged on oral clindamycin and doxycycline. Two days later, she presented to our emergency department with pain in the left axilla. Physical examination revealed 3 tender erythematous nodules in a linear distribution on the left arm with crusting at the incision and drainage site and painful left axillary lymphadenopathy. The patient was afebrile and otherwise asymptomatic.

Solitary Nodular Lesion on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Pilomatricoma

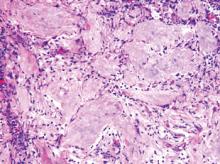

Pilomatricoma, first described by Malherbe and Chenantais1 in 1880, is a benign appendageal tumor derived from hair follicle matrix cells. It classically manifests as a solitary, asymptomatic, firm dermal nodule with a normal overlying epidermis. Less common morphologic variants include perforating, lymphagiectatic, keratoacanthomalike, pigmented, and anetodermalike surface changes.2 Inflammation and erosion through the skin surface are observed in the rare perforating variant, as seen in our patient. The average size is 1 cm, and it rarely exceeds 3 cm in diameter.3 The tumors predominantly occur on the head, neck, and upper extremities, with only 9.5% on the scalp.2 It may occur at any age, though it has a bimodal distribution with peaks in childhood and in adults older than 60 years. A slight preponderance in females has been observed with a female to male ratio of 1.5 to 1.2 Although our patient is black, most reported cases have occurred in individuals of European descent. Because cases of pilomatricoma are not systematically reported, it is uncertain if this finding represents a publication bias or if race is an actual risk factor. Multiple pilomatricomas and familial cases have been described in association with myotonic dystrophy, Turner syndrome, Gardner syndrome, Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, polyfactorial coagulopathy, trisomy 9, xeroderma pigmentosum, and basal cell nevus syndrome.2,4

It has been shown that the proliferating cells of pilomatricomas stain with antibodies directed against Lef1 (lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1), a marker from hair matrix cells, providing biochemical evidence for the morphologic appearance of these neoplasms.5 Pilomatricomas have been associated with B-cell/chronic lymphocytic leukemia lymphoma 2 gene, BCL2, expression, a proto-oncogene that suppresses apoptosis in benign and malignant neoplasms, which may contribute to the pathogenesis of these tumors.6 Pilomatricomas also have been associated with β-catenin mutation, expression of Bmp2 (bone morphogenetic protein 2), and human hair keratin basic 1.7-9

Definitive diagnosis is obtained through biopsy, looking for characteristic histopathologic findings. The lesion usually is found in the lower dermis and subcutaneous fat. However, in the perforating variant, the lesion is more superficial, located in the papillary and mid dermis, as seen in our patient.10

Pilomatricomas are sharply demarcated, often surrounded by a connective-tissue capsule. Histopathologic analysis reveals islands of epithelial cells comprised of 3 subtypes: basophilic cells with scant cytoplasm, shadow cells with a central pallor (Figure), and transitional cells between the former 2 cellular types.11 The number of basophilic and transitional cells is inversely related to the number of shadow cells. In older lesions, the shadow cells predominate, while the basophilic cells are few in number or absent. Calcium deposits are seen in 80% of lesions with von Kossa staining.12

Transformation into malignancy, known as pilomatrical carcinoma, is rare. These malignant neoplasms are characterized by aggressive biologic behavior such as recurrence, diffuse spread, or metastasis, or by cytologic abnormalities such as poor cellular organization, squamous differentiation, and conspicuous mitotic activity.13 The recent growth of the long-standing lesion in our patient might be interpreted as a sign of malignant transformation. However, this observation may be related to the intense inflammatory reaction supported by the histopathology.

Pilomatricomas are not associated with mortality. Pilomatrical carcinomas are uncommon but are locally invasive and can cause visceral metastases and death. Spontaneous regression has never been observed and medical treatment is ineffective. The treatment of choice is incision and curettage or surgical excision.14 Although recurrence has only been reported in 2.6% of cases from a large case series (N=228), patients should be monitored after surgical excision.12

1. Malherbe A, Chenantais J. Note sur l'epithelioma calcifie des glandes sebacees. Prog Med. 1880;8:826-828.

2. Julian CG, Bowers PW. A clinical review of 209 pilomatricomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2, pt 1):191-195.

3. Lozzi GP, Soyer HP, Fruehauf J, et al. Giant pilomatricoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:286-289.

4. Hubbard VG, Whittaker SJ. Multiple familial pilomatricomas: an unusual case. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:281-283.

5. Kizawa K, Toyoda M, Ito M, et al. Aberrantly differentiated cells in benign pilomatrixoma reflect the normal hair follicle: immunohistochemical analysis of Ca-binding S100A2, S100A3 and S100A6 proteins. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:314-320.

6. Farrier S, Morgan M. bcl-2 expression in pilomatricoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:254-257.

7. Park SW, Suh KS, Wang HY, et al. Beta-catenin expression in the transitional cell zone of pilomatricoma. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:624-629.

8. Kurokawa I, Kusumoto K, Bessho K, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of bone morphogenetic protein-2 in pilomatricoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:754-758.

9. Cribier B, Asch PH, Regnier C, et al. Expression of human hair keratin basic 1 in pilomatrixoma: a study of 128 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:600-604.

10. Bayle P, Bazex J, Lamant L, et al. Multiple perforating and non perforating pilomatricomas in a patient with Churg-Strauss syndrome and Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:607-610.

11. Elder D, Elenitsas R, Ragsdale BD. Pilomatricoma. In: Elder D, Elenitsas R, Jaworsky C, et al, eds. Histopathology of the Skin. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1997:757-759.

12. Forbis R Jr, Helwig EB. Pilomatrixoma (calcifying epithelioma). Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:606-618.

13. Wood MG, Parhizgar B, Beerman H. Malignant pilomatricoma. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:770-773.

14. Thomas RW, Perkins JA, Ruegemer JL, et al. Surgical excision of pilomatrixoma of the head and neck: a retrospective review of 26 cases. Ear Nose Throat J. 1999;78:541, 544-546, 548.

The Diagnosis: Pilomatricoma

Pilomatricoma, first described by Malherbe and Chenantais1 in 1880, is a benign appendageal tumor derived from hair follicle matrix cells. It classically manifests as a solitary, asymptomatic, firm dermal nodule with a normal overlying epidermis. Less common morphologic variants include perforating, lymphagiectatic, keratoacanthomalike, pigmented, and anetodermalike surface changes.2 Inflammation and erosion through the skin surface are observed in the rare perforating variant, as seen in our patient. The average size is 1 cm, and it rarely exceeds 3 cm in diameter.3 The tumors predominantly occur on the head, neck, and upper extremities, with only 9.5% on the scalp.2 It may occur at any age, though it has a bimodal distribution with peaks in childhood and in adults older than 60 years. A slight preponderance in females has been observed with a female to male ratio of 1.5 to 1.2 Although our patient is black, most reported cases have occurred in individuals of European descent. Because cases of pilomatricoma are not systematically reported, it is uncertain if this finding represents a publication bias or if race is an actual risk factor. Multiple pilomatricomas and familial cases have been described in association with myotonic dystrophy, Turner syndrome, Gardner syndrome, Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, polyfactorial coagulopathy, trisomy 9, xeroderma pigmentosum, and basal cell nevus syndrome.2,4

It has been shown that the proliferating cells of pilomatricomas stain with antibodies directed against Lef1 (lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1), a marker from hair matrix cells, providing biochemical evidence for the morphologic appearance of these neoplasms.5 Pilomatricomas have been associated with B-cell/chronic lymphocytic leukemia lymphoma 2 gene, BCL2, expression, a proto-oncogene that suppresses apoptosis in benign and malignant neoplasms, which may contribute to the pathogenesis of these tumors.6 Pilomatricomas also have been associated with β-catenin mutation, expression of Bmp2 (bone morphogenetic protein 2), and human hair keratin basic 1.7-9

Definitive diagnosis is obtained through biopsy, looking for characteristic histopathologic findings. The lesion usually is found in the lower dermis and subcutaneous fat. However, in the perforating variant, the lesion is more superficial, located in the papillary and mid dermis, as seen in our patient.10

Pilomatricomas are sharply demarcated, often surrounded by a connective-tissue capsule. Histopathologic analysis reveals islands of epithelial cells comprised of 3 subtypes: basophilic cells with scant cytoplasm, shadow cells with a central pallor (Figure), and transitional cells between the former 2 cellular types.11 The number of basophilic and transitional cells is inversely related to the number of shadow cells. In older lesions, the shadow cells predominate, while the basophilic cells are few in number or absent. Calcium deposits are seen in 80% of lesions with von Kossa staining.12

Transformation into malignancy, known as pilomatrical carcinoma, is rare. These malignant neoplasms are characterized by aggressive biologic behavior such as recurrence, diffuse spread, or metastasis, or by cytologic abnormalities such as poor cellular organization, squamous differentiation, and conspicuous mitotic activity.13 The recent growth of the long-standing lesion in our patient might be interpreted as a sign of malignant transformation. However, this observation may be related to the intense inflammatory reaction supported by the histopathology.

Pilomatricomas are not associated with mortality. Pilomatrical carcinomas are uncommon but are locally invasive and can cause visceral metastases and death. Spontaneous regression has never been observed and medical treatment is ineffective. The treatment of choice is incision and curettage or surgical excision.14 Although recurrence has only been reported in 2.6% of cases from a large case series (N=228), patients should be monitored after surgical excision.12

The Diagnosis: Pilomatricoma

Pilomatricoma, first described by Malherbe and Chenantais1 in 1880, is a benign appendageal tumor derived from hair follicle matrix cells. It classically manifests as a solitary, asymptomatic, firm dermal nodule with a normal overlying epidermis. Less common morphologic variants include perforating, lymphagiectatic, keratoacanthomalike, pigmented, and anetodermalike surface changes.2 Inflammation and erosion through the skin surface are observed in the rare perforating variant, as seen in our patient. The average size is 1 cm, and it rarely exceeds 3 cm in diameter.3 The tumors predominantly occur on the head, neck, and upper extremities, with only 9.5% on the scalp.2 It may occur at any age, though it has a bimodal distribution with peaks in childhood and in adults older than 60 years. A slight preponderance in females has been observed with a female to male ratio of 1.5 to 1.2 Although our patient is black, most reported cases have occurred in individuals of European descent. Because cases of pilomatricoma are not systematically reported, it is uncertain if this finding represents a publication bias or if race is an actual risk factor. Multiple pilomatricomas and familial cases have been described in association with myotonic dystrophy, Turner syndrome, Gardner syndrome, Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, polyfactorial coagulopathy, trisomy 9, xeroderma pigmentosum, and basal cell nevus syndrome.2,4

It has been shown that the proliferating cells of pilomatricomas stain with antibodies directed against Lef1 (lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1), a marker from hair matrix cells, providing biochemical evidence for the morphologic appearance of these neoplasms.5 Pilomatricomas have been associated with B-cell/chronic lymphocytic leukemia lymphoma 2 gene, BCL2, expression, a proto-oncogene that suppresses apoptosis in benign and malignant neoplasms, which may contribute to the pathogenesis of these tumors.6 Pilomatricomas also have been associated with β-catenin mutation, expression of Bmp2 (bone morphogenetic protein 2), and human hair keratin basic 1.7-9

Definitive diagnosis is obtained through biopsy, looking for characteristic histopathologic findings. The lesion usually is found in the lower dermis and subcutaneous fat. However, in the perforating variant, the lesion is more superficial, located in the papillary and mid dermis, as seen in our patient.10

Pilomatricomas are sharply demarcated, often surrounded by a connective-tissue capsule. Histopathologic analysis reveals islands of epithelial cells comprised of 3 subtypes: basophilic cells with scant cytoplasm, shadow cells with a central pallor (Figure), and transitional cells between the former 2 cellular types.11 The number of basophilic and transitional cells is inversely related to the number of shadow cells. In older lesions, the shadow cells predominate, while the basophilic cells are few in number or absent. Calcium deposits are seen in 80% of lesions with von Kossa staining.12

Transformation into malignancy, known as pilomatrical carcinoma, is rare. These malignant neoplasms are characterized by aggressive biologic behavior such as recurrence, diffuse spread, or metastasis, or by cytologic abnormalities such as poor cellular organization, squamous differentiation, and conspicuous mitotic activity.13 The recent growth of the long-standing lesion in our patient might be interpreted as a sign of malignant transformation. However, this observation may be related to the intense inflammatory reaction supported by the histopathology.

Pilomatricomas are not associated with mortality. Pilomatrical carcinomas are uncommon but are locally invasive and can cause visceral metastases and death. Spontaneous regression has never been observed and medical treatment is ineffective. The treatment of choice is incision and curettage or surgical excision.14 Although recurrence has only been reported in 2.6% of cases from a large case series (N=228), patients should be monitored after surgical excision.12

1. Malherbe A, Chenantais J. Note sur l'epithelioma calcifie des glandes sebacees. Prog Med. 1880;8:826-828.

2. Julian CG, Bowers PW. A clinical review of 209 pilomatricomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2, pt 1):191-195.

3. Lozzi GP, Soyer HP, Fruehauf J, et al. Giant pilomatricoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:286-289.

4. Hubbard VG, Whittaker SJ. Multiple familial pilomatricomas: an unusual case. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:281-283.

5. Kizawa K, Toyoda M, Ito M, et al. Aberrantly differentiated cells in benign pilomatrixoma reflect the normal hair follicle: immunohistochemical analysis of Ca-binding S100A2, S100A3 and S100A6 proteins. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:314-320.

6. Farrier S, Morgan M. bcl-2 expression in pilomatricoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:254-257.

7. Park SW, Suh KS, Wang HY, et al. Beta-catenin expression in the transitional cell zone of pilomatricoma. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:624-629.

8. Kurokawa I, Kusumoto K, Bessho K, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of bone morphogenetic protein-2 in pilomatricoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:754-758.

9. Cribier B, Asch PH, Regnier C, et al. Expression of human hair keratin basic 1 in pilomatrixoma: a study of 128 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:600-604.

10. Bayle P, Bazex J, Lamant L, et al. Multiple perforating and non perforating pilomatricomas in a patient with Churg-Strauss syndrome and Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:607-610.

11. Elder D, Elenitsas R, Ragsdale BD. Pilomatricoma. In: Elder D, Elenitsas R, Jaworsky C, et al, eds. Histopathology of the Skin. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1997:757-759.

12. Forbis R Jr, Helwig EB. Pilomatrixoma (calcifying epithelioma). Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:606-618.

13. Wood MG, Parhizgar B, Beerman H. Malignant pilomatricoma. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:770-773.

14. Thomas RW, Perkins JA, Ruegemer JL, et al. Surgical excision of pilomatrixoma of the head and neck: a retrospective review of 26 cases. Ear Nose Throat J. 1999;78:541, 544-546, 548.

1. Malherbe A, Chenantais J. Note sur l'epithelioma calcifie des glandes sebacees. Prog Med. 1880;8:826-828.

2. Julian CG, Bowers PW. A clinical review of 209 pilomatricomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2, pt 1):191-195.

3. Lozzi GP, Soyer HP, Fruehauf J, et al. Giant pilomatricoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:286-289.

4. Hubbard VG, Whittaker SJ. Multiple familial pilomatricomas: an unusual case. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:281-283.

5. Kizawa K, Toyoda M, Ito M, et al. Aberrantly differentiated cells in benign pilomatrixoma reflect the normal hair follicle: immunohistochemical analysis of Ca-binding S100A2, S100A3 and S100A6 proteins. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:314-320.

6. Farrier S, Morgan M. bcl-2 expression in pilomatricoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:254-257.

7. Park SW, Suh KS, Wang HY, et al. Beta-catenin expression in the transitional cell zone of pilomatricoma. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:624-629.

8. Kurokawa I, Kusumoto K, Bessho K, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of bone morphogenetic protein-2 in pilomatricoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:754-758.

9. Cribier B, Asch PH, Regnier C, et al. Expression of human hair keratin basic 1 in pilomatrixoma: a study of 128 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:600-604.

10. Bayle P, Bazex J, Lamant L, et al. Multiple perforating and non perforating pilomatricomas in a patient with Churg-Strauss syndrome and Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:607-610.

11. Elder D, Elenitsas R, Ragsdale BD. Pilomatricoma. In: Elder D, Elenitsas R, Jaworsky C, et al, eds. Histopathology of the Skin. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1997:757-759.

12. Forbis R Jr, Helwig EB. Pilomatrixoma (calcifying epithelioma). Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:606-618.

13. Wood MG, Parhizgar B, Beerman H. Malignant pilomatricoma. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:770-773.

14. Thomas RW, Perkins JA, Ruegemer JL, et al. Surgical excision of pilomatrixoma of the head and neck: a retrospective review of 26 cases. Ear Nose Throat J. 1999;78:541, 544-546, 548.

An otherwise healthy 40-year-old man presented for examination of a solitary nodular lesion on the frontal aspect of the scalp of 1 year’s duration. The lesion had rapidly increased in size in the 2 weeks prior to presentation. He presented to the emergency department after he noted pain and drainage from the lesion. Biopsy of the lesion revealed islands of pale eosinophilic shadow cells with an intense dermal infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils.