User login

How safe and effective is ondansetron for nausea and vomiting in pregnancy?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Efficacy. A 2014 double-blind RCT compared ondansetron with pyridoxine plus doxylamine (standard care) for outpatient treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy.1 The 36 patients had an average gestational age of 8 weeks and received either 4 mg oral ondansetron plus placebo or 25 mg pyridoxine plus 12.5 mg doxylamine 3 times daily for 5 days. Nausea and vomiting severity was measured using 2 separate 10-cm visual analog scales (VAS) with scores ranging from 0 to 10 (worst nausea or vomiting imaginable). Researchers determined that a VAS score reduction of 2.5 cm was clinically significant.

Patients treated with ondansetron described greater improvements in nausea (mean VAS change −5.1 cm vs −2 cm; P = .019) and vomiting (mean VAS change −4.1 cm vs −1.7 cm; P = .049). No patient required hospitalization. The researchers didn’t report on adverse effects or birth outcomes. The study was limited by the small sample size and a high rate (17%) of patients with missing data or who were lost to follow-up.

IV ondansetron vs metoclopramide: Similar efficacy, fewer adverse effects

A 2014 double-blind RCT compared IV ondansetron with IV metoclopramide (standard care) for treating hyperemesis gravidarum.2 The 160 patients had an average gestational age of 9.5 weeks and intractable nausea and vomiting severe enough to cause dehydration, metabolic disturbance, and hospitalization. Patients received either 4 mg ondansetron or 10 mg metoclopramide IV every 8 hours for 24 hours. The primary outcomes were number of episodes of vomiting over 24 hours and self-reported sense of well-being rated on a 10-point scale.

No differences were found between the ondansetron- and metoclopramide-treated groups in terms of vomiting over 24 hours (median episodes 1 and 1; P = .38) or sense of well-being (mean scores 8.7 vs 8.3; P = .13). Patients treated with ondansetron were less likely to have persistent ketonuria at 24 hours (relative risk [RR] = 0.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.1-0.8; number needed to treat [NNT] = 6). They also were less likely to feel drowsy (RR = 0.3; 95% CI, 0.1–0.8; NNT = 6) or complain of dry mouth (RR = 0.4; 95% CI, 0.1-0.9; NNT = 8). The study didn’t report birth outcomes or adverse fetal effects.

Oral ondansetron outperforms oral metoclopramide in small study

A 2013 double-blind RCT compared ondansetron with metoclopramide (standard care) for controlling severe nausea and vomiting.3 The 83 patients, with an average gestational age of 8.7 weeks, had more than 3 vomiting episodes daily, weight loss, and ketonuria. They received either 4 mg oral ondansetron or 10 mg oral metoclopramide for 2 weeks as follows: 3 times daily for 1 week, then twice daily for 3 days, then once daily for 4 days. Patients rated nausea severity using a 10-cm VAS from 0 to 10 (severe nausea) and recorded the number of vomiting episodes.

Women treated with ondansetron had significantly lower VAS scores on Days 3 and 4 of treatment (5.4 vs 6, P = .024 on Day 3; 4.1 vs 5.7, P = .023 on Day 4). They also had fewer episodes of vomiting on Days 2, 3, and 4 (3.7 vs 6, P = .006 on Day 2; 3.2 vs 5.3, P = .006 on Day 3; and 3.3 vs 5, P = .013 on Day 4). The study was limited by the small sample size.

Safety. A 2016 systematic review examining the risk of birth defects associated with ondansetron exposure in pregnancy found 8 reports: 5 birth registries, 2 case-control studies, and 1 prospective cohort study.4 Investigators compared rates of major malformations—cleft lips, cleft palates, neural tube defects, cardiac defects, and hypospadias—in 5101 women exposed to ondansetron in the first trimester with birth defect rates in more than 3.1 million nonexposed women.

Continue to: No study demonstrated...

No study demonstrated an increased rate of major malformations associated with ondansetron exposure except for 2 disease registry studies with nearly 2.4 million patients that reported a slight increase in the risk of cardiac defects (odds ratio [OR] = 2; 95% CI, 1.3-3.1; OR = 1.6, 95% CI, 1-2.1). Comparisons of other birth defect rates associated with ondansetron exposure were inconsistent, with studies showing small increases, decreases, or no difference in rates between exposed and nonexposed women.

Exposure vs nonexposure: No difference in adverse outcomes

A 2013 retrospective cohort study looked at 608,385 pregnancies among women in Denmark, of whom 1970 (0.3%) had been exposed to ondansetron.5 The study found that exposure to ondansetron compared with nonexposure was associated with a lower risk for spontaneous abortion between 7 and 12 weeks’ gestation (1.1% vs 3.7%; hazard ratio [HR] = 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3-0.9).

No significant differences between ondansetron exposure and nonexposure were found for the following adverse outcomes: spontaneous abortion between 13 and 22 weeks’ gestation (1% vs 2.1%; HR = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.3-1.2); stillbirth (0.3% vs 0.4%; HR = 0.4; 95% CI, 0.1-1.7); any major birth defect (2.9% in both exposed and nonexposed women; OR = 1.12; 95% CI, 0.69-1.82); preterm delivery (6.2% vs 5.2%; OR = 0.9; 95% CI, 0.7-1.3), low birth weight infant (4.1% vs 3.7%; OR = 0.8; 95% CI, 0.5-1.1); and small-for-gestational-age infant (10.4% vs 9.2%; OR = 1.1; 95% CI, 0.9-1.4).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) states that insufficient data exist regarding the safety of ondansetron for the fetus.6 ACOG recommends individualizing the use of ondansetron before 10 weeks of pregnancy after weighing the risks and benefits. ACOG also recommends adding ondansetron as third-line treatment for nausea and vomiting unresponsive to first- and second-line treatments.

EDITOR'S TAKEAWAY

Higher-quality studies showed ondansetron to be an effective treatment for hyperemesis gravidarum. Lower-quality studies raised some concerns about adverse fetal effects. Although the adverse effects were rare and the quality of the evidence was lower, the cautionary principle suggests that ondansetron should be a second-line option.

1. Oliveira LG, Capp SM, You WB, et al. Ondansetron compared with doxylamine and pyridoxine for treatment of nausea in pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:735-742.

2. Abas MN, Tan PC, Azmi N, et al. Ondansetron compared with metoclopramide for hyperemesis gravidarum: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:1272-1279.

3. Kashifard M, Basirat Z, Kashifard M, et al. Ondansetrone or metoclopromide? Which is more effective in severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy? A randomized trial double-blind study. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2013;40:127-130.

4. Carstairs SD. Ondansetron use in pregnancy and birth defects: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:878-883.

5. Pasternak B, Svanström H, Hviid A. Ondansetron in pregnancy and risk of adverse fetal outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:814-823.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 189: Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e15-e30.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Efficacy. A 2014 double-blind RCT compared ondansetron with pyridoxine plus doxylamine (standard care) for outpatient treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy.1 The 36 patients had an average gestational age of 8 weeks and received either 4 mg oral ondansetron plus placebo or 25 mg pyridoxine plus 12.5 mg doxylamine 3 times daily for 5 days. Nausea and vomiting severity was measured using 2 separate 10-cm visual analog scales (VAS) with scores ranging from 0 to 10 (worst nausea or vomiting imaginable). Researchers determined that a VAS score reduction of 2.5 cm was clinically significant.

Patients treated with ondansetron described greater improvements in nausea (mean VAS change −5.1 cm vs −2 cm; P = .019) and vomiting (mean VAS change −4.1 cm vs −1.7 cm; P = .049). No patient required hospitalization. The researchers didn’t report on adverse effects or birth outcomes. The study was limited by the small sample size and a high rate (17%) of patients with missing data or who were lost to follow-up.

IV ondansetron vs metoclopramide: Similar efficacy, fewer adverse effects

A 2014 double-blind RCT compared IV ondansetron with IV metoclopramide (standard care) for treating hyperemesis gravidarum.2 The 160 patients had an average gestational age of 9.5 weeks and intractable nausea and vomiting severe enough to cause dehydration, metabolic disturbance, and hospitalization. Patients received either 4 mg ondansetron or 10 mg metoclopramide IV every 8 hours for 24 hours. The primary outcomes were number of episodes of vomiting over 24 hours and self-reported sense of well-being rated on a 10-point scale.

No differences were found between the ondansetron- and metoclopramide-treated groups in terms of vomiting over 24 hours (median episodes 1 and 1; P = .38) or sense of well-being (mean scores 8.7 vs 8.3; P = .13). Patients treated with ondansetron were less likely to have persistent ketonuria at 24 hours (relative risk [RR] = 0.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.1-0.8; number needed to treat [NNT] = 6). They also were less likely to feel drowsy (RR = 0.3; 95% CI, 0.1–0.8; NNT = 6) or complain of dry mouth (RR = 0.4; 95% CI, 0.1-0.9; NNT = 8). The study didn’t report birth outcomes or adverse fetal effects.

Oral ondansetron outperforms oral metoclopramide in small study

A 2013 double-blind RCT compared ondansetron with metoclopramide (standard care) for controlling severe nausea and vomiting.3 The 83 patients, with an average gestational age of 8.7 weeks, had more than 3 vomiting episodes daily, weight loss, and ketonuria. They received either 4 mg oral ondansetron or 10 mg oral metoclopramide for 2 weeks as follows: 3 times daily for 1 week, then twice daily for 3 days, then once daily for 4 days. Patients rated nausea severity using a 10-cm VAS from 0 to 10 (severe nausea) and recorded the number of vomiting episodes.

Women treated with ondansetron had significantly lower VAS scores on Days 3 and 4 of treatment (5.4 vs 6, P = .024 on Day 3; 4.1 vs 5.7, P = .023 on Day 4). They also had fewer episodes of vomiting on Days 2, 3, and 4 (3.7 vs 6, P = .006 on Day 2; 3.2 vs 5.3, P = .006 on Day 3; and 3.3 vs 5, P = .013 on Day 4). The study was limited by the small sample size.

Safety. A 2016 systematic review examining the risk of birth defects associated with ondansetron exposure in pregnancy found 8 reports: 5 birth registries, 2 case-control studies, and 1 prospective cohort study.4 Investigators compared rates of major malformations—cleft lips, cleft palates, neural tube defects, cardiac defects, and hypospadias—in 5101 women exposed to ondansetron in the first trimester with birth defect rates in more than 3.1 million nonexposed women.

Continue to: No study demonstrated...

No study demonstrated an increased rate of major malformations associated with ondansetron exposure except for 2 disease registry studies with nearly 2.4 million patients that reported a slight increase in the risk of cardiac defects (odds ratio [OR] = 2; 95% CI, 1.3-3.1; OR = 1.6, 95% CI, 1-2.1). Comparisons of other birth defect rates associated with ondansetron exposure were inconsistent, with studies showing small increases, decreases, or no difference in rates between exposed and nonexposed women.

Exposure vs nonexposure: No difference in adverse outcomes

A 2013 retrospective cohort study looked at 608,385 pregnancies among women in Denmark, of whom 1970 (0.3%) had been exposed to ondansetron.5 The study found that exposure to ondansetron compared with nonexposure was associated with a lower risk for spontaneous abortion between 7 and 12 weeks’ gestation (1.1% vs 3.7%; hazard ratio [HR] = 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3-0.9).

No significant differences between ondansetron exposure and nonexposure were found for the following adverse outcomes: spontaneous abortion between 13 and 22 weeks’ gestation (1% vs 2.1%; HR = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.3-1.2); stillbirth (0.3% vs 0.4%; HR = 0.4; 95% CI, 0.1-1.7); any major birth defect (2.9% in both exposed and nonexposed women; OR = 1.12; 95% CI, 0.69-1.82); preterm delivery (6.2% vs 5.2%; OR = 0.9; 95% CI, 0.7-1.3), low birth weight infant (4.1% vs 3.7%; OR = 0.8; 95% CI, 0.5-1.1); and small-for-gestational-age infant (10.4% vs 9.2%; OR = 1.1; 95% CI, 0.9-1.4).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) states that insufficient data exist regarding the safety of ondansetron for the fetus.6 ACOG recommends individualizing the use of ondansetron before 10 weeks of pregnancy after weighing the risks and benefits. ACOG also recommends adding ondansetron as third-line treatment for nausea and vomiting unresponsive to first- and second-line treatments.

EDITOR'S TAKEAWAY

Higher-quality studies showed ondansetron to be an effective treatment for hyperemesis gravidarum. Lower-quality studies raised some concerns about adverse fetal effects. Although the adverse effects were rare and the quality of the evidence was lower, the cautionary principle suggests that ondansetron should be a second-line option.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Efficacy. A 2014 double-blind RCT compared ondansetron with pyridoxine plus doxylamine (standard care) for outpatient treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy.1 The 36 patients had an average gestational age of 8 weeks and received either 4 mg oral ondansetron plus placebo or 25 mg pyridoxine plus 12.5 mg doxylamine 3 times daily for 5 days. Nausea and vomiting severity was measured using 2 separate 10-cm visual analog scales (VAS) with scores ranging from 0 to 10 (worst nausea or vomiting imaginable). Researchers determined that a VAS score reduction of 2.5 cm was clinically significant.

Patients treated with ondansetron described greater improvements in nausea (mean VAS change −5.1 cm vs −2 cm; P = .019) and vomiting (mean VAS change −4.1 cm vs −1.7 cm; P = .049). No patient required hospitalization. The researchers didn’t report on adverse effects or birth outcomes. The study was limited by the small sample size and a high rate (17%) of patients with missing data or who were lost to follow-up.

IV ondansetron vs metoclopramide: Similar efficacy, fewer adverse effects

A 2014 double-blind RCT compared IV ondansetron with IV metoclopramide (standard care) for treating hyperemesis gravidarum.2 The 160 patients had an average gestational age of 9.5 weeks and intractable nausea and vomiting severe enough to cause dehydration, metabolic disturbance, and hospitalization. Patients received either 4 mg ondansetron or 10 mg metoclopramide IV every 8 hours for 24 hours. The primary outcomes were number of episodes of vomiting over 24 hours and self-reported sense of well-being rated on a 10-point scale.

No differences were found between the ondansetron- and metoclopramide-treated groups in terms of vomiting over 24 hours (median episodes 1 and 1; P = .38) or sense of well-being (mean scores 8.7 vs 8.3; P = .13). Patients treated with ondansetron were less likely to have persistent ketonuria at 24 hours (relative risk [RR] = 0.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.1-0.8; number needed to treat [NNT] = 6). They also were less likely to feel drowsy (RR = 0.3; 95% CI, 0.1–0.8; NNT = 6) or complain of dry mouth (RR = 0.4; 95% CI, 0.1-0.9; NNT = 8). The study didn’t report birth outcomes or adverse fetal effects.

Oral ondansetron outperforms oral metoclopramide in small study

A 2013 double-blind RCT compared ondansetron with metoclopramide (standard care) for controlling severe nausea and vomiting.3 The 83 patients, with an average gestational age of 8.7 weeks, had more than 3 vomiting episodes daily, weight loss, and ketonuria. They received either 4 mg oral ondansetron or 10 mg oral metoclopramide for 2 weeks as follows: 3 times daily for 1 week, then twice daily for 3 days, then once daily for 4 days. Patients rated nausea severity using a 10-cm VAS from 0 to 10 (severe nausea) and recorded the number of vomiting episodes.

Women treated with ondansetron had significantly lower VAS scores on Days 3 and 4 of treatment (5.4 vs 6, P = .024 on Day 3; 4.1 vs 5.7, P = .023 on Day 4). They also had fewer episodes of vomiting on Days 2, 3, and 4 (3.7 vs 6, P = .006 on Day 2; 3.2 vs 5.3, P = .006 on Day 3; and 3.3 vs 5, P = .013 on Day 4). The study was limited by the small sample size.

Safety. A 2016 systematic review examining the risk of birth defects associated with ondansetron exposure in pregnancy found 8 reports: 5 birth registries, 2 case-control studies, and 1 prospective cohort study.4 Investigators compared rates of major malformations—cleft lips, cleft palates, neural tube defects, cardiac defects, and hypospadias—in 5101 women exposed to ondansetron in the first trimester with birth defect rates in more than 3.1 million nonexposed women.

Continue to: No study demonstrated...

No study demonstrated an increased rate of major malformations associated with ondansetron exposure except for 2 disease registry studies with nearly 2.4 million patients that reported a slight increase in the risk of cardiac defects (odds ratio [OR] = 2; 95% CI, 1.3-3.1; OR = 1.6, 95% CI, 1-2.1). Comparisons of other birth defect rates associated with ondansetron exposure were inconsistent, with studies showing small increases, decreases, or no difference in rates between exposed and nonexposed women.

Exposure vs nonexposure: No difference in adverse outcomes

A 2013 retrospective cohort study looked at 608,385 pregnancies among women in Denmark, of whom 1970 (0.3%) had been exposed to ondansetron.5 The study found that exposure to ondansetron compared with nonexposure was associated with a lower risk for spontaneous abortion between 7 and 12 weeks’ gestation (1.1% vs 3.7%; hazard ratio [HR] = 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3-0.9).

No significant differences between ondansetron exposure and nonexposure were found for the following adverse outcomes: spontaneous abortion between 13 and 22 weeks’ gestation (1% vs 2.1%; HR = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.3-1.2); stillbirth (0.3% vs 0.4%; HR = 0.4; 95% CI, 0.1-1.7); any major birth defect (2.9% in both exposed and nonexposed women; OR = 1.12; 95% CI, 0.69-1.82); preterm delivery (6.2% vs 5.2%; OR = 0.9; 95% CI, 0.7-1.3), low birth weight infant (4.1% vs 3.7%; OR = 0.8; 95% CI, 0.5-1.1); and small-for-gestational-age infant (10.4% vs 9.2%; OR = 1.1; 95% CI, 0.9-1.4).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) states that insufficient data exist regarding the safety of ondansetron for the fetus.6 ACOG recommends individualizing the use of ondansetron before 10 weeks of pregnancy after weighing the risks and benefits. ACOG also recommends adding ondansetron as third-line treatment for nausea and vomiting unresponsive to first- and second-line treatments.

EDITOR'S TAKEAWAY

Higher-quality studies showed ondansetron to be an effective treatment for hyperemesis gravidarum. Lower-quality studies raised some concerns about adverse fetal effects. Although the adverse effects were rare and the quality of the evidence was lower, the cautionary principle suggests that ondansetron should be a second-line option.

1. Oliveira LG, Capp SM, You WB, et al. Ondansetron compared with doxylamine and pyridoxine for treatment of nausea in pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:735-742.

2. Abas MN, Tan PC, Azmi N, et al. Ondansetron compared with metoclopramide for hyperemesis gravidarum: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:1272-1279.

3. Kashifard M, Basirat Z, Kashifard M, et al. Ondansetrone or metoclopromide? Which is more effective in severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy? A randomized trial double-blind study. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2013;40:127-130.

4. Carstairs SD. Ondansetron use in pregnancy and birth defects: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:878-883.

5. Pasternak B, Svanström H, Hviid A. Ondansetron in pregnancy and risk of adverse fetal outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:814-823.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 189: Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e15-e30.

1. Oliveira LG, Capp SM, You WB, et al. Ondansetron compared with doxylamine and pyridoxine for treatment of nausea in pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:735-742.

2. Abas MN, Tan PC, Azmi N, et al. Ondansetron compared with metoclopramide for hyperemesis gravidarum: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:1272-1279.

3. Kashifard M, Basirat Z, Kashifard M, et al. Ondansetrone or metoclopromide? Which is more effective in severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy? A randomized trial double-blind study. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2013;40:127-130.

4. Carstairs SD. Ondansetron use in pregnancy and birth defects: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:878-883.

5. Pasternak B, Svanström H, Hviid A. Ondansetron in pregnancy and risk of adverse fetal outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:814-823.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 189: Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e15-e30.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Oral ondansetron is more effective than a combination of pyridoxine and doxylamine for outpatient treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, randomized controlled trial [RCT]).

For moderate to severe nausea and vomiting, intravenous (IV) ondansetron is at least as effective as IV metoclopramide and may cause fewer adverse reactions (SOR: B, RCTs).

Disease registry, case-control, and cohort studies report a slight increase in the risk of cardiac defects with ondansetron use in first-trimester pregnancies, but no major or other birth defects are associated with ondansetron exposure (SOR: B, a systematic review of observational trials and a single retrospective cohort study).

A specialty society guideline recommends weighing the risks and benefits of ondansetron use before 10 weeks’ gestational age and suggests reserving ondansetron for patients who have persistent nausea and vomiting unresponsive to first- and second-line treatments (SOR: C, expert opinion).

Making a diagnostic checklist more useful

I read with interest Dr. Hickner’s editorial, “How to avoid diagnostic errors” (J Fam Pract. 2014;63:625), and was fascinated by the diagnostic checklists developed by John Ely, MD, which are available at www.improvediagnosis.org/resource/resmgr/docs/diffdx.doc.

On his checklists, Dr. Ely suggests the material could be adapted for use on a handheld device, so I decided to convert Dr. Ely’s checklists from Microsoft Word to a PDF with hyperlinks so they would be easy to view on most tablets and smartphones. I kept the content exactly the same, but formatted each diagnostic problem as a “header,” which became the table of contents. Each of these table of contents headers is hyperlinked, so a user can simply tap on the item in the table of contents and jump to the correct page (“card”) in the document.

After converting Dr. Ely’s checklists to a PDF, I found them easy to use on both an iPhone and Google tablet.

Thank you again, Drs. Ely and Hickner, for your work in this area.

E. Chris Vincent, MD

Seattle, Wash

Dr. Vincent is one of the assistant editors for Clinical Inquiries, a monthly column in The Journal of Family Practice.

Dr. Hickner’s list of 7 ways to avoid diagnostic errors was excellent. I would augment his sixth tip (“Follow up, follow up, follow up, and do so in a timely manner”) with something we tell all of our patients: “Keep me informed via our online portal.” When patients have such easy access to communication with their physician, the diagnostic process is greatly enhanced.

Joseph E. Scherger, MD, MPH

Rancho Mirage, Calif

I read with interest Dr. Hickner’s editorial, “How to avoid diagnostic errors” (J Fam Pract. 2014;63:625), and was fascinated by the diagnostic checklists developed by John Ely, MD, which are available at www.improvediagnosis.org/resource/resmgr/docs/diffdx.doc.

On his checklists, Dr. Ely suggests the material could be adapted for use on a handheld device, so I decided to convert Dr. Ely’s checklists from Microsoft Word to a PDF with hyperlinks so they would be easy to view on most tablets and smartphones. I kept the content exactly the same, but formatted each diagnostic problem as a “header,” which became the table of contents. Each of these table of contents headers is hyperlinked, so a user can simply tap on the item in the table of contents and jump to the correct page (“card”) in the document.

After converting Dr. Ely’s checklists to a PDF, I found them easy to use on both an iPhone and Google tablet.

Thank you again, Drs. Ely and Hickner, for your work in this area.

E. Chris Vincent, MD

Seattle, Wash

Dr. Vincent is one of the assistant editors for Clinical Inquiries, a monthly column in The Journal of Family Practice.

Dr. Hickner’s list of 7 ways to avoid diagnostic errors was excellent. I would augment his sixth tip (“Follow up, follow up, follow up, and do so in a timely manner”) with something we tell all of our patients: “Keep me informed via our online portal.” When patients have such easy access to communication with their physician, the diagnostic process is greatly enhanced.

Joseph E. Scherger, MD, MPH

Rancho Mirage, Calif

I read with interest Dr. Hickner’s editorial, “How to avoid diagnostic errors” (J Fam Pract. 2014;63:625), and was fascinated by the diagnostic checklists developed by John Ely, MD, which are available at www.improvediagnosis.org/resource/resmgr/docs/diffdx.doc.

On his checklists, Dr. Ely suggests the material could be adapted for use on a handheld device, so I decided to convert Dr. Ely’s checklists from Microsoft Word to a PDF with hyperlinks so they would be easy to view on most tablets and smartphones. I kept the content exactly the same, but formatted each diagnostic problem as a “header,” which became the table of contents. Each of these table of contents headers is hyperlinked, so a user can simply tap on the item in the table of contents and jump to the correct page (“card”) in the document.

After converting Dr. Ely’s checklists to a PDF, I found them easy to use on both an iPhone and Google tablet.

Thank you again, Drs. Ely and Hickner, for your work in this area.

E. Chris Vincent, MD

Seattle, Wash

Dr. Vincent is one of the assistant editors for Clinical Inquiries, a monthly column in The Journal of Family Practice.

Dr. Hickner’s list of 7 ways to avoid diagnostic errors was excellent. I would augment his sixth tip (“Follow up, follow up, follow up, and do so in a timely manner”) with something we tell all of our patients: “Keep me informed via our online portal.” When patients have such easy access to communication with their physician, the diagnostic process is greatly enhanced.

Joseph E. Scherger, MD, MPH

Rancho Mirage, Calif

What Are the Benefits and Risks of Inhaled Corticosteroids for COPD?

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), either alone or with a long-acting β agonist (LABA), reduce the frequency of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and statistically, but not clinically, improve quality of life (QOL) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analyses of heterogeneous studies).

However, ICS have no mortality benefit and don’t consistently improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes). They increase the risk of pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes).

Withdrawal of ICS doesn’t significantly increase the risk of COPD exacerbation (SOR: B, a meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane meta-analysis designed to determine the efficacy of ICS in patients with stable COPD found 55 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 16,154 participants that compared ICS with placebo for 2 weeks to 3 years duration.1 COPD varied from moderate to severe in most studies.

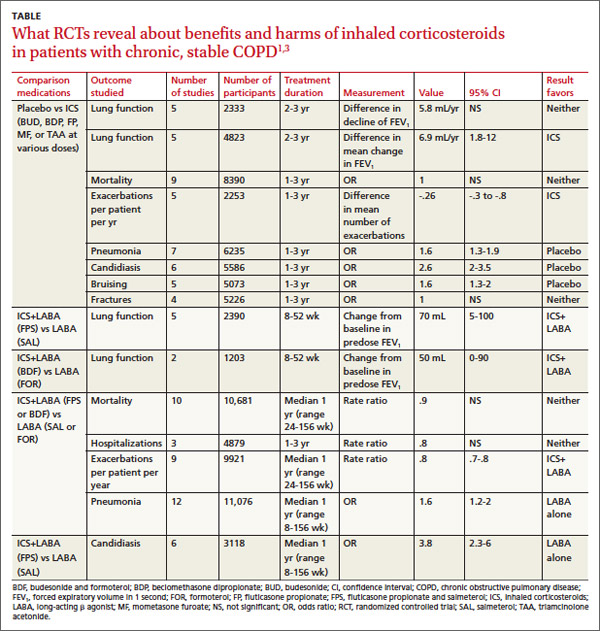

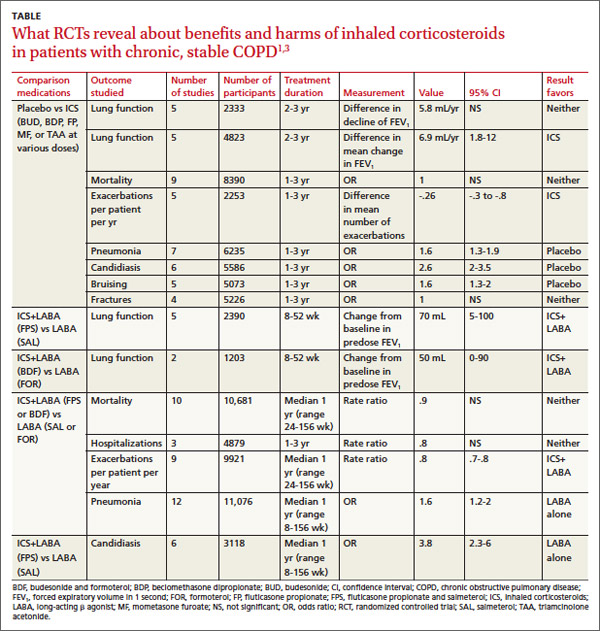

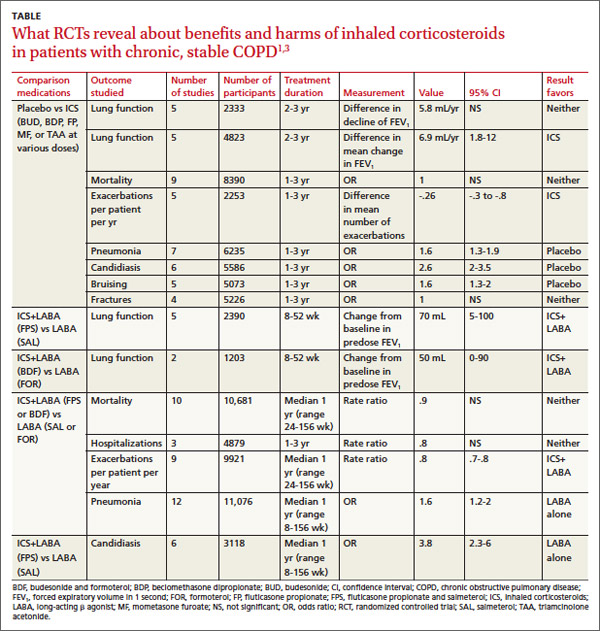

In pooled data, ICS for 2 or more years didn’t consistently improve lung function, the primary outcome (TABLE). However, the largest RCT (N=2617) of 3 years duration showed a small decrease in decline of FEV1 (55 mL compared with 42 mL, P value not provided). Regarding the secondary outcomes of mortality and exacerbations, ICS for a year or longer didn’t reduce mortality but decreased exacerbations by 19%.

Clinically significant adverse effects of ICS use included pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising; for ICS treatment longer than one year, the numbers needed to harm (NNH) compared with placebo were 30, 27, and 32, respectively. Bone fractures weren’t more common among ICS users. Investigators observed a statistical, but not clinical, QOL benefit as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) in 5 RCTs with a total of 2507 patients (mean difference, ‒1.22 units/year; 95% confidence interval, ‒1.83 to ‒.60). The minimum clinically important difference on the 76-item questionnaire was 4 units.2

Adding ICS to LABA increases risk of pneumonia and candidiasis

A Cochrane meta-analysis of 14 double-blind RCTs comprising a total of 11,794 participants with severe COPD compared LABA plus ICS with LABA alone over 8 weeks to 3 years.3 Primary outcomes were exacerbations, mortality, hospitalizations, and pneumonia. Secondary outcomes included oropharyngeal candidiasis and health-related QOL.

The LABA-plus-ICS group had lower rates of exacerbations than the LABA group, but the data were of low quality because of significant heterogeneity among studies and high rates of attrition. No significant difference in mortality or hospitalizations was found between the groups. The risk of pneumonia in the LABA-plus-ICS group was higher than in the LABA-alone group, with a NNH of 48.

Candidiasis occurred more often in patients on combination fluticasone and salmeterol than salmeterol alone, with a NNH of 22. QOL scores (measured by the SGRQ) in patients on combination therapy were statistically better, but clinically insignificant.

Discontinuing ICS doesn’t increase exacerbations

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs that enrolled a total of 877 patients with COPD compared the number of exacerbations in patients who continued fluticasone 500 mcg inhaled twice daily and patients who were withdrawn from the medication. All patients had been treated with ICS for at least 3 months, and had been on fluticasone for at least 2 weeks. Subjects had a baseline FEV1 between 25% and 80% predicted. No significant increase in exacerbations occurred after discontinuing ICS.4

Recommendations

The American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society, in a joint guideline, recommend against using ICS as monotherapy for patients with stable COPD. They acknowledge that these drugs are superior to placebo in reducing exacerbations, but note that concerns about their side-effect profile (thrush, potential for bone loss, and moderate to severe easy bruisability) make them less desirable than LABAs or long-acting inhaled anticholinergics.5

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease likewise discourages long-term use of ICS because of the risk of pneumonia and fractures.6 Both groups note that patients with severe COPD may benefit from a combination of ICS and a long-acting medication (usually a LABA).

1. Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD002991.

2. Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2:75-79.

3. Nannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD006829.

4. Nadeem NJ, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SM. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in individuals with COPD—a systemic review and comment on trial methodology. Respir Res. 2011;12:107.

5. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al; American College of Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

6. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2014. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report2014_Feb07.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2013.

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), either alone or with a long-acting β agonist (LABA), reduce the frequency of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and statistically, but not clinically, improve quality of life (QOL) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analyses of heterogeneous studies).

However, ICS have no mortality benefit and don’t consistently improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes). They increase the risk of pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes).

Withdrawal of ICS doesn’t significantly increase the risk of COPD exacerbation (SOR: B, a meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane meta-analysis designed to determine the efficacy of ICS in patients with stable COPD found 55 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 16,154 participants that compared ICS with placebo for 2 weeks to 3 years duration.1 COPD varied from moderate to severe in most studies.

In pooled data, ICS for 2 or more years didn’t consistently improve lung function, the primary outcome (TABLE). However, the largest RCT (N=2617) of 3 years duration showed a small decrease in decline of FEV1 (55 mL compared with 42 mL, P value not provided). Regarding the secondary outcomes of mortality and exacerbations, ICS for a year or longer didn’t reduce mortality but decreased exacerbations by 19%.

Clinically significant adverse effects of ICS use included pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising; for ICS treatment longer than one year, the numbers needed to harm (NNH) compared with placebo were 30, 27, and 32, respectively. Bone fractures weren’t more common among ICS users. Investigators observed a statistical, but not clinical, QOL benefit as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) in 5 RCTs with a total of 2507 patients (mean difference, ‒1.22 units/year; 95% confidence interval, ‒1.83 to ‒.60). The minimum clinically important difference on the 76-item questionnaire was 4 units.2

Adding ICS to LABA increases risk of pneumonia and candidiasis

A Cochrane meta-analysis of 14 double-blind RCTs comprising a total of 11,794 participants with severe COPD compared LABA plus ICS with LABA alone over 8 weeks to 3 years.3 Primary outcomes were exacerbations, mortality, hospitalizations, and pneumonia. Secondary outcomes included oropharyngeal candidiasis and health-related QOL.

The LABA-plus-ICS group had lower rates of exacerbations than the LABA group, but the data were of low quality because of significant heterogeneity among studies and high rates of attrition. No significant difference in mortality or hospitalizations was found between the groups. The risk of pneumonia in the LABA-plus-ICS group was higher than in the LABA-alone group, with a NNH of 48.

Candidiasis occurred more often in patients on combination fluticasone and salmeterol than salmeterol alone, with a NNH of 22. QOL scores (measured by the SGRQ) in patients on combination therapy were statistically better, but clinically insignificant.

Discontinuing ICS doesn’t increase exacerbations

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs that enrolled a total of 877 patients with COPD compared the number of exacerbations in patients who continued fluticasone 500 mcg inhaled twice daily and patients who were withdrawn from the medication. All patients had been treated with ICS for at least 3 months, and had been on fluticasone for at least 2 weeks. Subjects had a baseline FEV1 between 25% and 80% predicted. No significant increase in exacerbations occurred after discontinuing ICS.4

Recommendations

The American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society, in a joint guideline, recommend against using ICS as monotherapy for patients with stable COPD. They acknowledge that these drugs are superior to placebo in reducing exacerbations, but note that concerns about their side-effect profile (thrush, potential for bone loss, and moderate to severe easy bruisability) make them less desirable than LABAs or long-acting inhaled anticholinergics.5

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease likewise discourages long-term use of ICS because of the risk of pneumonia and fractures.6 Both groups note that patients with severe COPD may benefit from a combination of ICS and a long-acting medication (usually a LABA).

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), either alone or with a long-acting β agonist (LABA), reduce the frequency of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and statistically, but not clinically, improve quality of life (QOL) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analyses of heterogeneous studies).

However, ICS have no mortality benefit and don’t consistently improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes). They increase the risk of pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes).

Withdrawal of ICS doesn’t significantly increase the risk of COPD exacerbation (SOR: B, a meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane meta-analysis designed to determine the efficacy of ICS in patients with stable COPD found 55 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 16,154 participants that compared ICS with placebo for 2 weeks to 3 years duration.1 COPD varied from moderate to severe in most studies.

In pooled data, ICS for 2 or more years didn’t consistently improve lung function, the primary outcome (TABLE). However, the largest RCT (N=2617) of 3 years duration showed a small decrease in decline of FEV1 (55 mL compared with 42 mL, P value not provided). Regarding the secondary outcomes of mortality and exacerbations, ICS for a year or longer didn’t reduce mortality but decreased exacerbations by 19%.

Clinically significant adverse effects of ICS use included pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising; for ICS treatment longer than one year, the numbers needed to harm (NNH) compared with placebo were 30, 27, and 32, respectively. Bone fractures weren’t more common among ICS users. Investigators observed a statistical, but not clinical, QOL benefit as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) in 5 RCTs with a total of 2507 patients (mean difference, ‒1.22 units/year; 95% confidence interval, ‒1.83 to ‒.60). The minimum clinically important difference on the 76-item questionnaire was 4 units.2

Adding ICS to LABA increases risk of pneumonia and candidiasis

A Cochrane meta-analysis of 14 double-blind RCTs comprising a total of 11,794 participants with severe COPD compared LABA plus ICS with LABA alone over 8 weeks to 3 years.3 Primary outcomes were exacerbations, mortality, hospitalizations, and pneumonia. Secondary outcomes included oropharyngeal candidiasis and health-related QOL.

The LABA-plus-ICS group had lower rates of exacerbations than the LABA group, but the data were of low quality because of significant heterogeneity among studies and high rates of attrition. No significant difference in mortality or hospitalizations was found between the groups. The risk of pneumonia in the LABA-plus-ICS group was higher than in the LABA-alone group, with a NNH of 48.

Candidiasis occurred more often in patients on combination fluticasone and salmeterol than salmeterol alone, with a NNH of 22. QOL scores (measured by the SGRQ) in patients on combination therapy were statistically better, but clinically insignificant.

Discontinuing ICS doesn’t increase exacerbations

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs that enrolled a total of 877 patients with COPD compared the number of exacerbations in patients who continued fluticasone 500 mcg inhaled twice daily and patients who were withdrawn from the medication. All patients had been treated with ICS for at least 3 months, and had been on fluticasone for at least 2 weeks. Subjects had a baseline FEV1 between 25% and 80% predicted. No significant increase in exacerbations occurred after discontinuing ICS.4

Recommendations

The American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society, in a joint guideline, recommend against using ICS as monotherapy for patients with stable COPD. They acknowledge that these drugs are superior to placebo in reducing exacerbations, but note that concerns about their side-effect profile (thrush, potential for bone loss, and moderate to severe easy bruisability) make them less desirable than LABAs or long-acting inhaled anticholinergics.5

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease likewise discourages long-term use of ICS because of the risk of pneumonia and fractures.6 Both groups note that patients with severe COPD may benefit from a combination of ICS and a long-acting medication (usually a LABA).

1. Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD002991.

2. Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2:75-79.

3. Nannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD006829.

4. Nadeem NJ, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SM. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in individuals with COPD—a systemic review and comment on trial methodology. Respir Res. 2011;12:107.

5. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al; American College of Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

6. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2014. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report2014_Feb07.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2013.

1. Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD002991.

2. Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2:75-79.

3. Nannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD006829.

4. Nadeem NJ, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SM. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in individuals with COPD—a systemic review and comment on trial methodology. Respir Res. 2011;12:107.

5. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al; American College of Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

6. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2014. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report2014_Feb07.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2013.

What are the benefits and risks of inhaled corticosteroids for COPD?

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), either alone or with a long-acting β agonist (LABA), reduce the frequency of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and statistically, but not clinically, improve quality of life (QOL) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analyses of heterogeneous studies).

However, ICS have no mortality benefit and don’t consistently improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes). They increase the risk of pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes).

Withdrawal of ICS doesn’t significantly increase the risk of COPD exacerbation (SOR: B, a meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane meta-analysis designed to determine the efficacy of ICS in patients with stable COPD found 55 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 16,154 participants that compared ICS with placebo for 2 weeks to 3 years duration.1 COPD varied from moderate to severe in most studies.

In pooled data, ICS for 2 or more years didn’t consistently improve lung function, the primary outcome (TABLE). However, the largest RCT (N=2617) of 3 years duration showed a small decrease in decline of FEV1 (55 mL compared with 42 mL, P value not provided). Regarding the secondary outcomes of mortality and exacerbations, ICS for a year or longer didn’t reduce mortality but decreased exacerbations by 19%.

Clinically significant adverse effects of ICS use included pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising; for ICS treatment longer than one year, the numbers needed to harm (NNH) compared with placebo were 30, 27, and 32, respectively. Bone fractures weren’t more common among ICS users. Investigators observed a statistical, but not clinical, QOL benefit as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) in 5 RCTs with a total of 2507 patients (mean difference, ‒1.22 units/year; 95% confidence interval, ‒1.83 to ‒.60). The minimum clinically important difference on the 76-item questionnaire was 4 units.2

Adding ICS to LABA increases risk of pneumonia and candidiasis

A Cochrane meta-analysis of 14 double-blind RCTs comprising a total of 11,794 participants with severe COPD compared LABA plus ICS with LABA alone over 8 weeks to 3 years.3 Primary outcomes were exacerbations, mortality, hospitalizations, and pneumonia. Secondary outcomes included oropharyngeal candidiasis and health-related QOL.

The LABA-plus-ICS group had lower rates of exacerbations than the LABA group, but the data were of low quality because of significant heterogeneity among studies and high rates of attrition. No significant difference in mortality or hospitalizations was found between the groups. The risk of pneumonia in the LABA-plus-ICS group was higher than in the LABA-alone group, with a NNH of 48.

Candidiasis occurred more often in patients on combination fluticasone and salmeterol than salmeterol alone, with a NNH of 22. QOL scores (measured by the SGRQ) in patients on combination therapy were statistically better, but clinically insignificant.

Discontinuing ICS doesn’t increase exacerbations

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs that enrolled a total of 877 patients with COPD compared the number of exacerbations in patients who continued fluticasone 500 mcg inhaled twice daily and patients who were withdrawn from the medication. All patients had been treated with ICS for at least 3 months, and had been on fluticasone for at least 2 weeks. Subjects had a baseline FEV1 between 25% and 80% predicted. No significant increase in exacerbations occurred after discontinuing ICS.4

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society, in a joint guideline, recommend against using ICS as monotherapy for patients with stable COPD. They acknowledge that these drugs are superior to placebo in reducing exacerbations, but note that concerns about their side-effect profile (thrush, potential for bone loss, and moderate to severe easy bruisability) make them less desirable than LABAs or long-acting inhaled anticholinergics.5

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease likewise discourages long-term use of ICS because of the risk of pneumonia and fractures.6 Both groups note that patients with severe COPD may benefit from a combination of ICS and a long-acting medication (usually a LABA).

1. Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD002991.

2. Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2:75-79.

3. Nannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD006829.

4. Nadeem NJ, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SM. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in individuals with COPD—a systemic review and comment on trial methodology. Respir Res. 2011;12:107.

5. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al; American College of Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

6. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2014. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report2014_Feb07.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2013.

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), either alone or with a long-acting β agonist (LABA), reduce the frequency of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and statistically, but not clinically, improve quality of life (QOL) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analyses of heterogeneous studies).

However, ICS have no mortality benefit and don’t consistently improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes). They increase the risk of pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes).

Withdrawal of ICS doesn’t significantly increase the risk of COPD exacerbation (SOR: B, a meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane meta-analysis designed to determine the efficacy of ICS in patients with stable COPD found 55 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 16,154 participants that compared ICS with placebo for 2 weeks to 3 years duration.1 COPD varied from moderate to severe in most studies.

In pooled data, ICS for 2 or more years didn’t consistently improve lung function, the primary outcome (TABLE). However, the largest RCT (N=2617) of 3 years duration showed a small decrease in decline of FEV1 (55 mL compared with 42 mL, P value not provided). Regarding the secondary outcomes of mortality and exacerbations, ICS for a year or longer didn’t reduce mortality but decreased exacerbations by 19%.

Clinically significant adverse effects of ICS use included pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising; for ICS treatment longer than one year, the numbers needed to harm (NNH) compared with placebo were 30, 27, and 32, respectively. Bone fractures weren’t more common among ICS users. Investigators observed a statistical, but not clinical, QOL benefit as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) in 5 RCTs with a total of 2507 patients (mean difference, ‒1.22 units/year; 95% confidence interval, ‒1.83 to ‒.60). The minimum clinically important difference on the 76-item questionnaire was 4 units.2

Adding ICS to LABA increases risk of pneumonia and candidiasis

A Cochrane meta-analysis of 14 double-blind RCTs comprising a total of 11,794 participants with severe COPD compared LABA plus ICS with LABA alone over 8 weeks to 3 years.3 Primary outcomes were exacerbations, mortality, hospitalizations, and pneumonia. Secondary outcomes included oropharyngeal candidiasis and health-related QOL.

The LABA-plus-ICS group had lower rates of exacerbations than the LABA group, but the data were of low quality because of significant heterogeneity among studies and high rates of attrition. No significant difference in mortality or hospitalizations was found between the groups. The risk of pneumonia in the LABA-plus-ICS group was higher than in the LABA-alone group, with a NNH of 48.

Candidiasis occurred more often in patients on combination fluticasone and salmeterol than salmeterol alone, with a NNH of 22. QOL scores (measured by the SGRQ) in patients on combination therapy were statistically better, but clinically insignificant.

Discontinuing ICS doesn’t increase exacerbations

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs that enrolled a total of 877 patients with COPD compared the number of exacerbations in patients who continued fluticasone 500 mcg inhaled twice daily and patients who were withdrawn from the medication. All patients had been treated with ICS for at least 3 months, and had been on fluticasone for at least 2 weeks. Subjects had a baseline FEV1 between 25% and 80% predicted. No significant increase in exacerbations occurred after discontinuing ICS.4

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society, in a joint guideline, recommend against using ICS as monotherapy for patients with stable COPD. They acknowledge that these drugs are superior to placebo in reducing exacerbations, but note that concerns about their side-effect profile (thrush, potential for bone loss, and moderate to severe easy bruisability) make them less desirable than LABAs or long-acting inhaled anticholinergics.5

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease likewise discourages long-term use of ICS because of the risk of pneumonia and fractures.6 Both groups note that patients with severe COPD may benefit from a combination of ICS and a long-acting medication (usually a LABA).

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), either alone or with a long-acting β agonist (LABA), reduce the frequency of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and statistically, but not clinically, improve quality of life (QOL) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analyses of heterogeneous studies).

However, ICS have no mortality benefit and don’t consistently improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes). They increase the risk of pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes).

Withdrawal of ICS doesn’t significantly increase the risk of COPD exacerbation (SOR: B, a meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane meta-analysis designed to determine the efficacy of ICS in patients with stable COPD found 55 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 16,154 participants that compared ICS with placebo for 2 weeks to 3 years duration.1 COPD varied from moderate to severe in most studies.

In pooled data, ICS for 2 or more years didn’t consistently improve lung function, the primary outcome (TABLE). However, the largest RCT (N=2617) of 3 years duration showed a small decrease in decline of FEV1 (55 mL compared with 42 mL, P value not provided). Regarding the secondary outcomes of mortality and exacerbations, ICS for a year or longer didn’t reduce mortality but decreased exacerbations by 19%.

Clinically significant adverse effects of ICS use included pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising; for ICS treatment longer than one year, the numbers needed to harm (NNH) compared with placebo were 30, 27, and 32, respectively. Bone fractures weren’t more common among ICS users. Investigators observed a statistical, but not clinical, QOL benefit as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) in 5 RCTs with a total of 2507 patients (mean difference, ‒1.22 units/year; 95% confidence interval, ‒1.83 to ‒.60). The minimum clinically important difference on the 76-item questionnaire was 4 units.2

Adding ICS to LABA increases risk of pneumonia and candidiasis

A Cochrane meta-analysis of 14 double-blind RCTs comprising a total of 11,794 participants with severe COPD compared LABA plus ICS with LABA alone over 8 weeks to 3 years.3 Primary outcomes were exacerbations, mortality, hospitalizations, and pneumonia. Secondary outcomes included oropharyngeal candidiasis and health-related QOL.

The LABA-plus-ICS group had lower rates of exacerbations than the LABA group, but the data were of low quality because of significant heterogeneity among studies and high rates of attrition. No significant difference in mortality or hospitalizations was found between the groups. The risk of pneumonia in the LABA-plus-ICS group was higher than in the LABA-alone group, with a NNH of 48.

Candidiasis occurred more often in patients on combination fluticasone and salmeterol than salmeterol alone, with a NNH of 22. QOL scores (measured by the SGRQ) in patients on combination therapy were statistically better, but clinically insignificant.

Discontinuing ICS doesn’t increase exacerbations

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs that enrolled a total of 877 patients with COPD compared the number of exacerbations in patients who continued fluticasone 500 mcg inhaled twice daily and patients who were withdrawn from the medication. All patients had been treated with ICS for at least 3 months, and had been on fluticasone for at least 2 weeks. Subjects had a baseline FEV1 between 25% and 80% predicted. No significant increase in exacerbations occurred after discontinuing ICS.4

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society, in a joint guideline, recommend against using ICS as monotherapy for patients with stable COPD. They acknowledge that these drugs are superior to placebo in reducing exacerbations, but note that concerns about their side-effect profile (thrush, potential for bone loss, and moderate to severe easy bruisability) make them less desirable than LABAs or long-acting inhaled anticholinergics.5

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease likewise discourages long-term use of ICS because of the risk of pneumonia and fractures.6 Both groups note that patients with severe COPD may benefit from a combination of ICS and a long-acting medication (usually a LABA).

1. Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD002991.

2. Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2:75-79.

3. Nannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD006829.

4. Nadeem NJ, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SM. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in individuals with COPD—a systemic review and comment on trial methodology. Respir Res. 2011;12:107.

5. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al; American College of Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

6. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2014. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report2014_Feb07.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2013.

1. Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD002991.

2. Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2:75-79.

3. Nannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD006829.

4. Nadeem NJ, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SM. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in individuals with COPD—a systemic review and comment on trial methodology. Respir Res. 2011;12:107.

5. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al; American College of Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

6. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2014. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report2014_Feb07.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2013.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network