User login

Do statins increase the risk of developing diabetes?

Yes. Statin therapy produces a small increase in the incidence of diabetes: one additional case per 255 patients taking statins over 4 years (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, meta-analysis). Intensive statin therapy, compared with moderate therapy, produces an additional 2 cases of diabetes per 1000 patient years (SOR: B, meta-analysis with significant heterogeneity among trials).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A meta-analysis of 13 randomized, placebo or standard of care-controlled statin trials (113,148 patients, 81% without diabetes at enrollment, mean ages 55-76 years) found that statin therapy increased the incidence of diabetes by 9% over 4 years (odds ratio [OR]=1.09; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02-1.17), or one additional case per 255 patients.1 The increased risk was similar for lipophilic (pravastatin, rosuvastatin) and hydrophilic (atorvastatin, simvastatin, lovastatin) statins, although the analysis wasn’t adjusted for doses used.

In a meta-regression analysis, baseline body mass index or percentage change in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol didn’t appear to confer additional risk. The risk of diabetes with statins was generally higher in studies with older patients (data given graphically).

Higher statin doses mean higher risk

A meta-analysis of 5 placebo and standard-of-care randomized controlled trials (39,612 patients, 83% without diabetes at enrollment, mean age 58-64 years) found that the risk of diabetes was higher with higher-dose statins.2 Therapy with atorvastatin 80 mg or simvastatin 40 to 80 mg was defined as intensive. Treatment with simvastatin 20 to 40 mg, atorvastatin 10 mg, or pravastatin 40 mg was defined as moderate.

At a mean follow-up of 4.9 years, intensive statin therapy was associated with a higher risk of developing diabetes than moderate therapy (OR=1.12; 95% CI, 1.04-1.22) with 2 additional cases of diabetes per 1000 patient-years in the intensive therapy group. The authors noted significant heterogeneity between trials with regard to major cardiovascular events.

Similar results were found in a subsequent population-based cohort study of 471,250 nondiabetic patients older than 66 years who were newly prescribed a statin.3 The study authors used the incidence of new diabetes in patients taking pravastatin as the baseline, since it had been associated with reduced rates of diabetes in a large cardiovascular prevention trial.4 Without adjusting for dose, patients were at significantly higher risk of diabetes if prescribed atorvastatin (hazard ratio [HR]=1.22; 95% CI, 1.15-1.29), rosuvastatin (HR=1.18; 95% CI, 1.10-1.26), or simvastatin (HR=1.10; 95% CI, 1.04-1.17) compared with pravastatin. The risk with fluvastatin and lovastatin was similar to pravastatin.

A subanalysis that compared moderate- and high-dose statin therapy with low-dose therapy (atorvastatin <20 mg, rosuvastatin <10 mg, simvastatin <80 mg, or any dose of fluvastatin, lovastatin, or pravastatin) found a 22% increased risk of diabetes (HR=1.22; 95% CI, 1.19-1.26) for moderate-dose therapy (atorvastatin 20-79 mg, rosuvastatin 10-39 mg, or simvastatin >80 mg) and a 30% increased risk (HR=1.3; 95% CI, 1.2-1.4) for high-dose therapy (atorvastatin ≥80 mg or rosuvastatin ≥40 mg).

A cohort trial also shows increased diabetes risk

A smaller subsequent cohort trial based on data from Taiwan National Health Insurance records compared 8412 nondiabetic adult patients (mean age 63 years) taking statins with 33,648 age- and risk-matched controls not taking statins over a mean duration of 7.2 years.5 Statin use was associated with a 15% higher risk of developing diabetes (HR=1.15; 95% CI, 1.08-1.22).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines for lipid-lowering therapy recommend that patients taking statins be screened for diabetes according to current screening recommendations.6 The guidelines advise encouraging patients who develop diabetes while on statin therapy to adhere to a heart-healthy dietary pattern, engage in physical activity, achieve and maintain a healthy body weight, cease tobacco use, and continue statin therapy to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events.

1. Sattar N, Preiss D, Murray HM, et al. Statins and risk of incident diabetes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomised statin trials. Lancet. 2010;375:735-742.

2. Preiss D, Seshasai SR, Welsh P, et al. Risk of incident diabetes with intensive-dose compared with moderatedose statin therapy: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305:2556-2564.

3. Carter AA, Gomes T, Camacho X, et al. Risk of incident diabetes among patients treated with statins: population-based study. BMJ. 2013;346:f2610.

4. Freeman DJ, Morrie J, Sattar N, et al. Pravastatin and the development of diabetes mellitus: evidence for a protective treatment effect in the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study. Circulation. 2001;103:357-362.

5. Wang KL, Liu CJ, Chao TF, et al. Statins, risk of diabetes and implications on outcomes in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1231-1238.

6. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129:S1-S45.

Yes. Statin therapy produces a small increase in the incidence of diabetes: one additional case per 255 patients taking statins over 4 years (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, meta-analysis). Intensive statin therapy, compared with moderate therapy, produces an additional 2 cases of diabetes per 1000 patient years (SOR: B, meta-analysis with significant heterogeneity among trials).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A meta-analysis of 13 randomized, placebo or standard of care-controlled statin trials (113,148 patients, 81% without diabetes at enrollment, mean ages 55-76 years) found that statin therapy increased the incidence of diabetes by 9% over 4 years (odds ratio [OR]=1.09; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02-1.17), or one additional case per 255 patients.1 The increased risk was similar for lipophilic (pravastatin, rosuvastatin) and hydrophilic (atorvastatin, simvastatin, lovastatin) statins, although the analysis wasn’t adjusted for doses used.

In a meta-regression analysis, baseline body mass index or percentage change in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol didn’t appear to confer additional risk. The risk of diabetes with statins was generally higher in studies with older patients (data given graphically).

Higher statin doses mean higher risk

A meta-analysis of 5 placebo and standard-of-care randomized controlled trials (39,612 patients, 83% without diabetes at enrollment, mean age 58-64 years) found that the risk of diabetes was higher with higher-dose statins.2 Therapy with atorvastatin 80 mg or simvastatin 40 to 80 mg was defined as intensive. Treatment with simvastatin 20 to 40 mg, atorvastatin 10 mg, or pravastatin 40 mg was defined as moderate.

At a mean follow-up of 4.9 years, intensive statin therapy was associated with a higher risk of developing diabetes than moderate therapy (OR=1.12; 95% CI, 1.04-1.22) with 2 additional cases of diabetes per 1000 patient-years in the intensive therapy group. The authors noted significant heterogeneity between trials with regard to major cardiovascular events.

Similar results were found in a subsequent population-based cohort study of 471,250 nondiabetic patients older than 66 years who were newly prescribed a statin.3 The study authors used the incidence of new diabetes in patients taking pravastatin as the baseline, since it had been associated with reduced rates of diabetes in a large cardiovascular prevention trial.4 Without adjusting for dose, patients were at significantly higher risk of diabetes if prescribed atorvastatin (hazard ratio [HR]=1.22; 95% CI, 1.15-1.29), rosuvastatin (HR=1.18; 95% CI, 1.10-1.26), or simvastatin (HR=1.10; 95% CI, 1.04-1.17) compared with pravastatin. The risk with fluvastatin and lovastatin was similar to pravastatin.

A subanalysis that compared moderate- and high-dose statin therapy with low-dose therapy (atorvastatin <20 mg, rosuvastatin <10 mg, simvastatin <80 mg, or any dose of fluvastatin, lovastatin, or pravastatin) found a 22% increased risk of diabetes (HR=1.22; 95% CI, 1.19-1.26) for moderate-dose therapy (atorvastatin 20-79 mg, rosuvastatin 10-39 mg, or simvastatin >80 mg) and a 30% increased risk (HR=1.3; 95% CI, 1.2-1.4) for high-dose therapy (atorvastatin ≥80 mg or rosuvastatin ≥40 mg).

A cohort trial also shows increased diabetes risk

A smaller subsequent cohort trial based on data from Taiwan National Health Insurance records compared 8412 nondiabetic adult patients (mean age 63 years) taking statins with 33,648 age- and risk-matched controls not taking statins over a mean duration of 7.2 years.5 Statin use was associated with a 15% higher risk of developing diabetes (HR=1.15; 95% CI, 1.08-1.22).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines for lipid-lowering therapy recommend that patients taking statins be screened for diabetes according to current screening recommendations.6 The guidelines advise encouraging patients who develop diabetes while on statin therapy to adhere to a heart-healthy dietary pattern, engage in physical activity, achieve and maintain a healthy body weight, cease tobacco use, and continue statin therapy to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events.

Yes. Statin therapy produces a small increase in the incidence of diabetes: one additional case per 255 patients taking statins over 4 years (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, meta-analysis). Intensive statin therapy, compared with moderate therapy, produces an additional 2 cases of diabetes per 1000 patient years (SOR: B, meta-analysis with significant heterogeneity among trials).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A meta-analysis of 13 randomized, placebo or standard of care-controlled statin trials (113,148 patients, 81% without diabetes at enrollment, mean ages 55-76 years) found that statin therapy increased the incidence of diabetes by 9% over 4 years (odds ratio [OR]=1.09; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02-1.17), or one additional case per 255 patients.1 The increased risk was similar for lipophilic (pravastatin, rosuvastatin) and hydrophilic (atorvastatin, simvastatin, lovastatin) statins, although the analysis wasn’t adjusted for doses used.

In a meta-regression analysis, baseline body mass index or percentage change in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol didn’t appear to confer additional risk. The risk of diabetes with statins was generally higher in studies with older patients (data given graphically).

Higher statin doses mean higher risk

A meta-analysis of 5 placebo and standard-of-care randomized controlled trials (39,612 patients, 83% without diabetes at enrollment, mean age 58-64 years) found that the risk of diabetes was higher with higher-dose statins.2 Therapy with atorvastatin 80 mg or simvastatin 40 to 80 mg was defined as intensive. Treatment with simvastatin 20 to 40 mg, atorvastatin 10 mg, or pravastatin 40 mg was defined as moderate.

At a mean follow-up of 4.9 years, intensive statin therapy was associated with a higher risk of developing diabetes than moderate therapy (OR=1.12; 95% CI, 1.04-1.22) with 2 additional cases of diabetes per 1000 patient-years in the intensive therapy group. The authors noted significant heterogeneity between trials with regard to major cardiovascular events.

Similar results were found in a subsequent population-based cohort study of 471,250 nondiabetic patients older than 66 years who were newly prescribed a statin.3 The study authors used the incidence of new diabetes in patients taking pravastatin as the baseline, since it had been associated with reduced rates of diabetes in a large cardiovascular prevention trial.4 Without adjusting for dose, patients were at significantly higher risk of diabetes if prescribed atorvastatin (hazard ratio [HR]=1.22; 95% CI, 1.15-1.29), rosuvastatin (HR=1.18; 95% CI, 1.10-1.26), or simvastatin (HR=1.10; 95% CI, 1.04-1.17) compared with pravastatin. The risk with fluvastatin and lovastatin was similar to pravastatin.

A subanalysis that compared moderate- and high-dose statin therapy with low-dose therapy (atorvastatin <20 mg, rosuvastatin <10 mg, simvastatin <80 mg, or any dose of fluvastatin, lovastatin, or pravastatin) found a 22% increased risk of diabetes (HR=1.22; 95% CI, 1.19-1.26) for moderate-dose therapy (atorvastatin 20-79 mg, rosuvastatin 10-39 mg, or simvastatin >80 mg) and a 30% increased risk (HR=1.3; 95% CI, 1.2-1.4) for high-dose therapy (atorvastatin ≥80 mg or rosuvastatin ≥40 mg).

A cohort trial also shows increased diabetes risk

A smaller subsequent cohort trial based on data from Taiwan National Health Insurance records compared 8412 nondiabetic adult patients (mean age 63 years) taking statins with 33,648 age- and risk-matched controls not taking statins over a mean duration of 7.2 years.5 Statin use was associated with a 15% higher risk of developing diabetes (HR=1.15; 95% CI, 1.08-1.22).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines for lipid-lowering therapy recommend that patients taking statins be screened for diabetes according to current screening recommendations.6 The guidelines advise encouraging patients who develop diabetes while on statin therapy to adhere to a heart-healthy dietary pattern, engage in physical activity, achieve and maintain a healthy body weight, cease tobacco use, and continue statin therapy to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events.

1. Sattar N, Preiss D, Murray HM, et al. Statins and risk of incident diabetes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomised statin trials. Lancet. 2010;375:735-742.

2. Preiss D, Seshasai SR, Welsh P, et al. Risk of incident diabetes with intensive-dose compared with moderatedose statin therapy: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305:2556-2564.

3. Carter AA, Gomes T, Camacho X, et al. Risk of incident diabetes among patients treated with statins: population-based study. BMJ. 2013;346:f2610.

4. Freeman DJ, Morrie J, Sattar N, et al. Pravastatin and the development of diabetes mellitus: evidence for a protective treatment effect in the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study. Circulation. 2001;103:357-362.

5. Wang KL, Liu CJ, Chao TF, et al. Statins, risk of diabetes and implications on outcomes in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1231-1238.

6. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129:S1-S45.

1. Sattar N, Preiss D, Murray HM, et al. Statins and risk of incident diabetes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomised statin trials. Lancet. 2010;375:735-742.

2. Preiss D, Seshasai SR, Welsh P, et al. Risk of incident diabetes with intensive-dose compared with moderatedose statin therapy: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305:2556-2564.

3. Carter AA, Gomes T, Camacho X, et al. Risk of incident diabetes among patients treated with statins: population-based study. BMJ. 2013;346:f2610.

4. Freeman DJ, Morrie J, Sattar N, et al. Pravastatin and the development of diabetes mellitus: evidence for a protective treatment effect in the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study. Circulation. 2001;103:357-362.

5. Wang KL, Liu CJ, Chao TF, et al. Statins, risk of diabetes and implications on outcomes in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1231-1238.

6. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129:S1-S45.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Does frenotomy help infants with tongue-tie overcome breastfeeding difficulties?

Probably not. No evidence exists for improved latching after frenotomy, and evidence concerning improvements in maternal comfort is conflicting. At best, frenotomy improves maternal nipple pain by 10% and maternal subjective sense of improvement over the short term (0 to 2 weeks) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, randomized controlled trials [RCTs] with conflicting results for maternal nipple pain and overall feeding).

No studies have evaluated outcomes such as infant weight gain following frenotomy.

Experts don’t recommend frenotomy unless a clear association exists between ankyloglossia (tongue-tie) and breastfeeding problems. Frenotomy should be performed with anesthesia by an experienced clinician to minimize the risk of complications (SOR: C, a practice guideline.)

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Two RCTs found short-term (0-14 days) improvement in breastfeeding after frenotomy. One, which evaluated the effect of frenotomy on infants with significant ankyloglossia and breastfeeding difficulties, found short-term improvement in maternal nipple pain. Investigators randomized 58 infants (mean age 6 days) with ankyloglossia (rated 8 out of 10 on a standardized severity scale) to receive either frenotomy or no intervention.1 They used the 50-point Short Form McGill Pain Questionnaire to measure maternal nipple pain at baseline, immediately after, and at 2, 4, 8, and 52 weeks.

Mothers in the intervention group reported a 10% greater reduction in nipple pain after frenotomy compared with the control group (11 points vs 6 points; P=.001). The improvement persisted at 2 weeks (graphic representation in study, P value not supplied) but not at 4 weeks or beyond.

An earlier, unblinded RCT randomized 40 infants (mean age 14 days) with ankyloglossia and breastfeeding problems to frenotomy or lactation support.2 It found maternal subjective ratings of “improvement” (not quantified) by telephone interview at 24 hours (85% vs 3%; P<.01). Investigators performed frenotomy on all 19 of the unimproved control infants at 48 hours.

Frenotomy doesn’t improve breastfeeding overall

Two newer RCTs evaluating frenotomy and LATCH (Latch, Audible swallowing, nipple Type, Comfort, and Hold) scores, which include a component measuring maternal comfort, found no breastfeeding improvements. (LATCH is a validated 10-point score with moderate predictive value for identifying mothers at risk for early weaning because of sore nipples.3)

A double-blind RCT that assessed frenotomy in 57 infants (mean age 32 days) with ankyloglossia and breastfeeding problems (severity of both unspecified) found no improvement in breastfeeding overall or nipple pain.4 Investigators randomized infants to frenotomy or sham frenotomy and used independent observers to measure outcomes with the LATCH score and the Infant Breastfeeding Assessment Tool (IBFAT), a standardized method of assessing overall feeding.

They observed no significant differences in LATCH or IBFAT scores between groups. More mothers in the frenotomy group reported improved breastfeeding, but most were able to determine whether their baby had undergone frenotomy.

A single-blinded, RCT of early frenotomy in 107 younger infants with breastfeeding difficulties and mild to moderate ankyloglossia also found no improvement in LATCH scores.5 Researchers randomized infants younger than 2 weeks (blinded to researchers and unblinded to mothers) to either immediate frenotomy or standard care. They measured LATCH scores at baseline and after 5 days (by intention to treat).

Investigators found no difference in LATCH scores at 5 days postfrenotomy (pretreatment score 6.4 ± 2.3, posttreatment 6.8 ± 2.0; not significant).

RECOMMENDATIONS

A 2011 position statement from the Community Paediatrics Committee of the Canadian Paediatric Society notes that ankyloglossia is a relatively uncommon congenital anomaly, and associations between ankyloglossia and breastfeeding problems in infants have been inconsistent.6 For these reasons, the Committee doesn’t recommend frenotomy.

However, if the clinician deems surgical intervention necessary based on a clear association between significant tongue-tie and major breastfeeding problems, then frenotomy should be performed by a clinician experienced in the procedure and with appropriate analgesia. The Committee states that although ankyloglossia release appears to be a minor procedure, it may cause complications such as bleeding, infection, or injury to the Wharton’s duct.

The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine, a worldwide organization of physicians dedicated to the promotion, protection, and support of breastfeeding and human lactation, is currently revising its guidelines on neonatal ankyloglossia.7

1. Buryk M, Bloom D, Shope T. Efficacy of neonatal release of ankyloglossia: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2011;128:280-288.

2. Hogan M, Westcott C, Griffiths M. Randomized, controlled trial of division of tongue-tie in infants with feeding problems. Paediatr Child Health. 2005;41:246-250.

3. Emond A, Ingram J, Johnson D, et al. Randomised controlled trial of early frenotomy in breastfed infants with mild-moderate tongue-tie. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2014;99:F189-F195.

4. Berry J, Griffiths M, Westcott C. A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial of tongue-tie division and its immediate effect on breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7:189-193.

5. Riordan J, Bibb D, Miller M, et al. Predicting breastfeeding duration using the LATCH breastfeeding assessment tool. J Hum Lact. 2001;17:20-23.

6. Rowan-Legg A. Ankyloglossia and breastfeeding. Paediatr Child Health. 2011;16:222.

7. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. Statements. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Web site. Available at: www.bfmed.org/Resources/Protocols.aspx. Accessed January 10, 2015.

Probably not. No evidence exists for improved latching after frenotomy, and evidence concerning improvements in maternal comfort is conflicting. At best, frenotomy improves maternal nipple pain by 10% and maternal subjective sense of improvement over the short term (0 to 2 weeks) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, randomized controlled trials [RCTs] with conflicting results for maternal nipple pain and overall feeding).

No studies have evaluated outcomes such as infant weight gain following frenotomy.

Experts don’t recommend frenotomy unless a clear association exists between ankyloglossia (tongue-tie) and breastfeeding problems. Frenotomy should be performed with anesthesia by an experienced clinician to minimize the risk of complications (SOR: C, a practice guideline.)

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Two RCTs found short-term (0-14 days) improvement in breastfeeding after frenotomy. One, which evaluated the effect of frenotomy on infants with significant ankyloglossia and breastfeeding difficulties, found short-term improvement in maternal nipple pain. Investigators randomized 58 infants (mean age 6 days) with ankyloglossia (rated 8 out of 10 on a standardized severity scale) to receive either frenotomy or no intervention.1 They used the 50-point Short Form McGill Pain Questionnaire to measure maternal nipple pain at baseline, immediately after, and at 2, 4, 8, and 52 weeks.

Mothers in the intervention group reported a 10% greater reduction in nipple pain after frenotomy compared with the control group (11 points vs 6 points; P=.001). The improvement persisted at 2 weeks (graphic representation in study, P value not supplied) but not at 4 weeks or beyond.

An earlier, unblinded RCT randomized 40 infants (mean age 14 days) with ankyloglossia and breastfeeding problems to frenotomy or lactation support.2 It found maternal subjective ratings of “improvement” (not quantified) by telephone interview at 24 hours (85% vs 3%; P<.01). Investigators performed frenotomy on all 19 of the unimproved control infants at 48 hours.

Frenotomy doesn’t improve breastfeeding overall

Two newer RCTs evaluating frenotomy and LATCH (Latch, Audible swallowing, nipple Type, Comfort, and Hold) scores, which include a component measuring maternal comfort, found no breastfeeding improvements. (LATCH is a validated 10-point score with moderate predictive value for identifying mothers at risk for early weaning because of sore nipples.3)

A double-blind RCT that assessed frenotomy in 57 infants (mean age 32 days) with ankyloglossia and breastfeeding problems (severity of both unspecified) found no improvement in breastfeeding overall or nipple pain.4 Investigators randomized infants to frenotomy or sham frenotomy and used independent observers to measure outcomes with the LATCH score and the Infant Breastfeeding Assessment Tool (IBFAT), a standardized method of assessing overall feeding.

They observed no significant differences in LATCH or IBFAT scores between groups. More mothers in the frenotomy group reported improved breastfeeding, but most were able to determine whether their baby had undergone frenotomy.

A single-blinded, RCT of early frenotomy in 107 younger infants with breastfeeding difficulties and mild to moderate ankyloglossia also found no improvement in LATCH scores.5 Researchers randomized infants younger than 2 weeks (blinded to researchers and unblinded to mothers) to either immediate frenotomy or standard care. They measured LATCH scores at baseline and after 5 days (by intention to treat).

Investigators found no difference in LATCH scores at 5 days postfrenotomy (pretreatment score 6.4 ± 2.3, posttreatment 6.8 ± 2.0; not significant).

RECOMMENDATIONS

A 2011 position statement from the Community Paediatrics Committee of the Canadian Paediatric Society notes that ankyloglossia is a relatively uncommon congenital anomaly, and associations between ankyloglossia and breastfeeding problems in infants have been inconsistent.6 For these reasons, the Committee doesn’t recommend frenotomy.

However, if the clinician deems surgical intervention necessary based on a clear association between significant tongue-tie and major breastfeeding problems, then frenotomy should be performed by a clinician experienced in the procedure and with appropriate analgesia. The Committee states that although ankyloglossia release appears to be a minor procedure, it may cause complications such as bleeding, infection, or injury to the Wharton’s duct.

The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine, a worldwide organization of physicians dedicated to the promotion, protection, and support of breastfeeding and human lactation, is currently revising its guidelines on neonatal ankyloglossia.7

Probably not. No evidence exists for improved latching after frenotomy, and evidence concerning improvements in maternal comfort is conflicting. At best, frenotomy improves maternal nipple pain by 10% and maternal subjective sense of improvement over the short term (0 to 2 weeks) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, randomized controlled trials [RCTs] with conflicting results for maternal nipple pain and overall feeding).

No studies have evaluated outcomes such as infant weight gain following frenotomy.

Experts don’t recommend frenotomy unless a clear association exists between ankyloglossia (tongue-tie) and breastfeeding problems. Frenotomy should be performed with anesthesia by an experienced clinician to minimize the risk of complications (SOR: C, a practice guideline.)

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Two RCTs found short-term (0-14 days) improvement in breastfeeding after frenotomy. One, which evaluated the effect of frenotomy on infants with significant ankyloglossia and breastfeeding difficulties, found short-term improvement in maternal nipple pain. Investigators randomized 58 infants (mean age 6 days) with ankyloglossia (rated 8 out of 10 on a standardized severity scale) to receive either frenotomy or no intervention.1 They used the 50-point Short Form McGill Pain Questionnaire to measure maternal nipple pain at baseline, immediately after, and at 2, 4, 8, and 52 weeks.

Mothers in the intervention group reported a 10% greater reduction in nipple pain after frenotomy compared with the control group (11 points vs 6 points; P=.001). The improvement persisted at 2 weeks (graphic representation in study, P value not supplied) but not at 4 weeks or beyond.

An earlier, unblinded RCT randomized 40 infants (mean age 14 days) with ankyloglossia and breastfeeding problems to frenotomy or lactation support.2 It found maternal subjective ratings of “improvement” (not quantified) by telephone interview at 24 hours (85% vs 3%; P<.01). Investigators performed frenotomy on all 19 of the unimproved control infants at 48 hours.

Frenotomy doesn’t improve breastfeeding overall

Two newer RCTs evaluating frenotomy and LATCH (Latch, Audible swallowing, nipple Type, Comfort, and Hold) scores, which include a component measuring maternal comfort, found no breastfeeding improvements. (LATCH is a validated 10-point score with moderate predictive value for identifying mothers at risk for early weaning because of sore nipples.3)

A double-blind RCT that assessed frenotomy in 57 infants (mean age 32 days) with ankyloglossia and breastfeeding problems (severity of both unspecified) found no improvement in breastfeeding overall or nipple pain.4 Investigators randomized infants to frenotomy or sham frenotomy and used independent observers to measure outcomes with the LATCH score and the Infant Breastfeeding Assessment Tool (IBFAT), a standardized method of assessing overall feeding.

They observed no significant differences in LATCH or IBFAT scores between groups. More mothers in the frenotomy group reported improved breastfeeding, but most were able to determine whether their baby had undergone frenotomy.

A single-blinded, RCT of early frenotomy in 107 younger infants with breastfeeding difficulties and mild to moderate ankyloglossia also found no improvement in LATCH scores.5 Researchers randomized infants younger than 2 weeks (blinded to researchers and unblinded to mothers) to either immediate frenotomy or standard care. They measured LATCH scores at baseline and after 5 days (by intention to treat).

Investigators found no difference in LATCH scores at 5 days postfrenotomy (pretreatment score 6.4 ± 2.3, posttreatment 6.8 ± 2.0; not significant).

RECOMMENDATIONS

A 2011 position statement from the Community Paediatrics Committee of the Canadian Paediatric Society notes that ankyloglossia is a relatively uncommon congenital anomaly, and associations between ankyloglossia and breastfeeding problems in infants have been inconsistent.6 For these reasons, the Committee doesn’t recommend frenotomy.

However, if the clinician deems surgical intervention necessary based on a clear association between significant tongue-tie and major breastfeeding problems, then frenotomy should be performed by a clinician experienced in the procedure and with appropriate analgesia. The Committee states that although ankyloglossia release appears to be a minor procedure, it may cause complications such as bleeding, infection, or injury to the Wharton’s duct.

The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine, a worldwide organization of physicians dedicated to the promotion, protection, and support of breastfeeding and human lactation, is currently revising its guidelines on neonatal ankyloglossia.7

1. Buryk M, Bloom D, Shope T. Efficacy of neonatal release of ankyloglossia: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2011;128:280-288.

2. Hogan M, Westcott C, Griffiths M. Randomized, controlled trial of division of tongue-tie in infants with feeding problems. Paediatr Child Health. 2005;41:246-250.

3. Emond A, Ingram J, Johnson D, et al. Randomised controlled trial of early frenotomy in breastfed infants with mild-moderate tongue-tie. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2014;99:F189-F195.

4. Berry J, Griffiths M, Westcott C. A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial of tongue-tie division and its immediate effect on breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7:189-193.

5. Riordan J, Bibb D, Miller M, et al. Predicting breastfeeding duration using the LATCH breastfeeding assessment tool. J Hum Lact. 2001;17:20-23.

6. Rowan-Legg A. Ankyloglossia and breastfeeding. Paediatr Child Health. 2011;16:222.

7. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. Statements. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Web site. Available at: www.bfmed.org/Resources/Protocols.aspx. Accessed January 10, 2015.

1. Buryk M, Bloom D, Shope T. Efficacy of neonatal release of ankyloglossia: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2011;128:280-288.

2. Hogan M, Westcott C, Griffiths M. Randomized, controlled trial of division of tongue-tie in infants with feeding problems. Paediatr Child Health. 2005;41:246-250.

3. Emond A, Ingram J, Johnson D, et al. Randomised controlled trial of early frenotomy in breastfed infants with mild-moderate tongue-tie. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2014;99:F189-F195.

4. Berry J, Griffiths M, Westcott C. A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial of tongue-tie division and its immediate effect on breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7:189-193.

5. Riordan J, Bibb D, Miller M, et al. Predicting breastfeeding duration using the LATCH breastfeeding assessment tool. J Hum Lact. 2001;17:20-23.

6. Rowan-Legg A. Ankyloglossia and breastfeeding. Paediatr Child Health. 2011;16:222.

7. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. Statements. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Web site. Available at: www.bfmed.org/Resources/Protocols.aspx. Accessed January 10, 2015.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

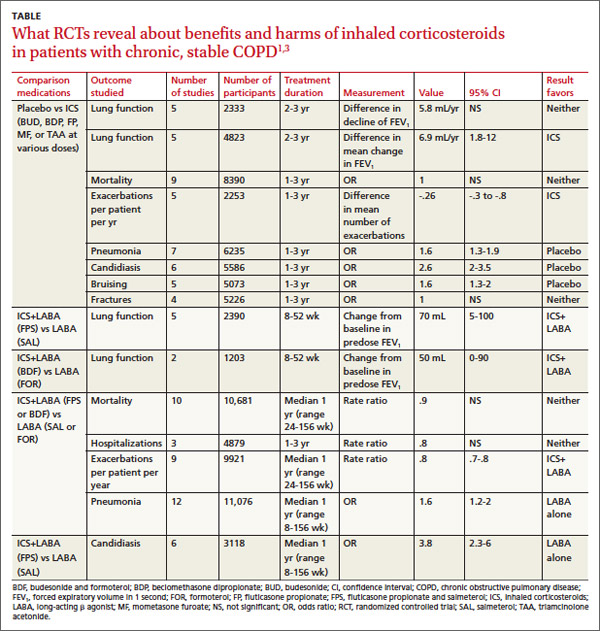

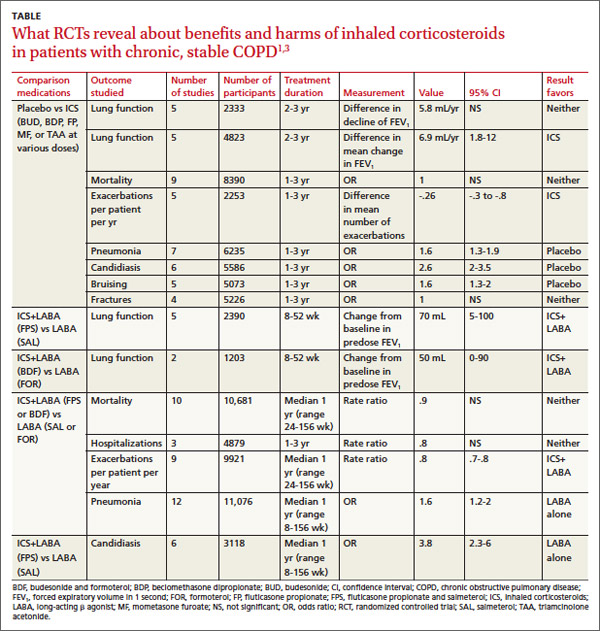

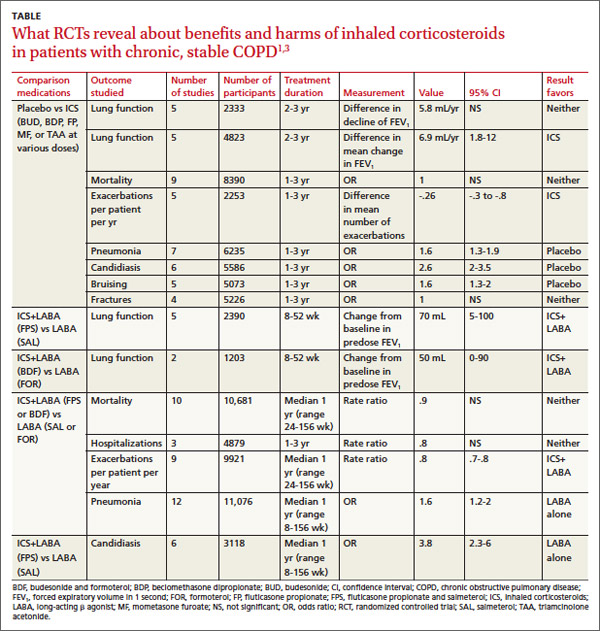

What are the benefits and risks of inhaled corticosteroids for COPD?

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), either alone or with a long-acting β agonist (LABA), reduce the frequency of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and statistically, but not clinically, improve quality of life (QOL) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analyses of heterogeneous studies).

However, ICS have no mortality benefit and don’t consistently improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes). They increase the risk of pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes).

Withdrawal of ICS doesn’t significantly increase the risk of COPD exacerbation (SOR: B, a meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane meta-analysis designed to determine the efficacy of ICS in patients with stable COPD found 55 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 16,154 participants that compared ICS with placebo for 2 weeks to 3 years duration.1 COPD varied from moderate to severe in most studies.

In pooled data, ICS for 2 or more years didn’t consistently improve lung function, the primary outcome (TABLE). However, the largest RCT (N=2617) of 3 years duration showed a small decrease in decline of FEV1 (55 mL compared with 42 mL, P value not provided). Regarding the secondary outcomes of mortality and exacerbations, ICS for a year or longer didn’t reduce mortality but decreased exacerbations by 19%.

Clinically significant adverse effects of ICS use included pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising; for ICS treatment longer than one year, the numbers needed to harm (NNH) compared with placebo were 30, 27, and 32, respectively. Bone fractures weren’t more common among ICS users. Investigators observed a statistical, but not clinical, QOL benefit as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) in 5 RCTs with a total of 2507 patients (mean difference, ‒1.22 units/year; 95% confidence interval, ‒1.83 to ‒.60). The minimum clinically important difference on the 76-item questionnaire was 4 units.2

Adding ICS to LABA increases risk of pneumonia and candidiasis

A Cochrane meta-analysis of 14 double-blind RCTs comprising a total of 11,794 participants with severe COPD compared LABA plus ICS with LABA alone over 8 weeks to 3 years.3 Primary outcomes were exacerbations, mortality, hospitalizations, and pneumonia. Secondary outcomes included oropharyngeal candidiasis and health-related QOL.

The LABA-plus-ICS group had lower rates of exacerbations than the LABA group, but the data were of low quality because of significant heterogeneity among studies and high rates of attrition. No significant difference in mortality or hospitalizations was found between the groups. The risk of pneumonia in the LABA-plus-ICS group was higher than in the LABA-alone group, with a NNH of 48.

Candidiasis occurred more often in patients on combination fluticasone and salmeterol than salmeterol alone, with a NNH of 22. QOL scores (measured by the SGRQ) in patients on combination therapy were statistically better, but clinically insignificant.

Discontinuing ICS doesn’t increase exacerbations

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs that enrolled a total of 877 patients with COPD compared the number of exacerbations in patients who continued fluticasone 500 mcg inhaled twice daily and patients who were withdrawn from the medication. All patients had been treated with ICS for at least 3 months, and had been on fluticasone for at least 2 weeks. Subjects had a baseline FEV1 between 25% and 80% predicted. No significant increase in exacerbations occurred after discontinuing ICS.4

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society, in a joint guideline, recommend against using ICS as monotherapy for patients with stable COPD. They acknowledge that these drugs are superior to placebo in reducing exacerbations, but note that concerns about their side-effect profile (thrush, potential for bone loss, and moderate to severe easy bruisability) make them less desirable than LABAs or long-acting inhaled anticholinergics.5

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease likewise discourages long-term use of ICS because of the risk of pneumonia and fractures.6 Both groups note that patients with severe COPD may benefit from a combination of ICS and a long-acting medication (usually a LABA).

1. Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD002991.

2. Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2:75-79.

3. Nannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD006829.

4. Nadeem NJ, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SM. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in individuals with COPD—a systemic review and comment on trial methodology. Respir Res. 2011;12:107.

5. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al; American College of Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

6. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2014. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report2014_Feb07.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2013.

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), either alone or with a long-acting β agonist (LABA), reduce the frequency of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and statistically, but not clinically, improve quality of life (QOL) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analyses of heterogeneous studies).

However, ICS have no mortality benefit and don’t consistently improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes). They increase the risk of pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes).

Withdrawal of ICS doesn’t significantly increase the risk of COPD exacerbation (SOR: B, a meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane meta-analysis designed to determine the efficacy of ICS in patients with stable COPD found 55 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 16,154 participants that compared ICS with placebo for 2 weeks to 3 years duration.1 COPD varied from moderate to severe in most studies.

In pooled data, ICS for 2 or more years didn’t consistently improve lung function, the primary outcome (TABLE). However, the largest RCT (N=2617) of 3 years duration showed a small decrease in decline of FEV1 (55 mL compared with 42 mL, P value not provided). Regarding the secondary outcomes of mortality and exacerbations, ICS for a year or longer didn’t reduce mortality but decreased exacerbations by 19%.

Clinically significant adverse effects of ICS use included pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising; for ICS treatment longer than one year, the numbers needed to harm (NNH) compared with placebo were 30, 27, and 32, respectively. Bone fractures weren’t more common among ICS users. Investigators observed a statistical, but not clinical, QOL benefit as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) in 5 RCTs with a total of 2507 patients (mean difference, ‒1.22 units/year; 95% confidence interval, ‒1.83 to ‒.60). The minimum clinically important difference on the 76-item questionnaire was 4 units.2

Adding ICS to LABA increases risk of pneumonia and candidiasis

A Cochrane meta-analysis of 14 double-blind RCTs comprising a total of 11,794 participants with severe COPD compared LABA plus ICS with LABA alone over 8 weeks to 3 years.3 Primary outcomes were exacerbations, mortality, hospitalizations, and pneumonia. Secondary outcomes included oropharyngeal candidiasis and health-related QOL.

The LABA-plus-ICS group had lower rates of exacerbations than the LABA group, but the data were of low quality because of significant heterogeneity among studies and high rates of attrition. No significant difference in mortality or hospitalizations was found between the groups. The risk of pneumonia in the LABA-plus-ICS group was higher than in the LABA-alone group, with a NNH of 48.

Candidiasis occurred more often in patients on combination fluticasone and salmeterol than salmeterol alone, with a NNH of 22. QOL scores (measured by the SGRQ) in patients on combination therapy were statistically better, but clinically insignificant.

Discontinuing ICS doesn’t increase exacerbations

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs that enrolled a total of 877 patients with COPD compared the number of exacerbations in patients who continued fluticasone 500 mcg inhaled twice daily and patients who were withdrawn from the medication. All patients had been treated with ICS for at least 3 months, and had been on fluticasone for at least 2 weeks. Subjects had a baseline FEV1 between 25% and 80% predicted. No significant increase in exacerbations occurred after discontinuing ICS.4

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society, in a joint guideline, recommend against using ICS as monotherapy for patients with stable COPD. They acknowledge that these drugs are superior to placebo in reducing exacerbations, but note that concerns about their side-effect profile (thrush, potential for bone loss, and moderate to severe easy bruisability) make them less desirable than LABAs or long-acting inhaled anticholinergics.5

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease likewise discourages long-term use of ICS because of the risk of pneumonia and fractures.6 Both groups note that patients with severe COPD may benefit from a combination of ICS and a long-acting medication (usually a LABA).

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), either alone or with a long-acting β agonist (LABA), reduce the frequency of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and statistically, but not clinically, improve quality of life (QOL) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analyses of heterogeneous studies).

However, ICS have no mortality benefit and don’t consistently improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes). They increase the risk of pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes).

Withdrawal of ICS doesn’t significantly increase the risk of COPD exacerbation (SOR: B, a meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane meta-analysis designed to determine the efficacy of ICS in patients with stable COPD found 55 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 16,154 participants that compared ICS with placebo for 2 weeks to 3 years duration.1 COPD varied from moderate to severe in most studies.

In pooled data, ICS for 2 or more years didn’t consistently improve lung function, the primary outcome (TABLE). However, the largest RCT (N=2617) of 3 years duration showed a small decrease in decline of FEV1 (55 mL compared with 42 mL, P value not provided). Regarding the secondary outcomes of mortality and exacerbations, ICS for a year or longer didn’t reduce mortality but decreased exacerbations by 19%.

Clinically significant adverse effects of ICS use included pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising; for ICS treatment longer than one year, the numbers needed to harm (NNH) compared with placebo were 30, 27, and 32, respectively. Bone fractures weren’t more common among ICS users. Investigators observed a statistical, but not clinical, QOL benefit as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) in 5 RCTs with a total of 2507 patients (mean difference, ‒1.22 units/year; 95% confidence interval, ‒1.83 to ‒.60). The minimum clinically important difference on the 76-item questionnaire was 4 units.2

Adding ICS to LABA increases risk of pneumonia and candidiasis

A Cochrane meta-analysis of 14 double-blind RCTs comprising a total of 11,794 participants with severe COPD compared LABA plus ICS with LABA alone over 8 weeks to 3 years.3 Primary outcomes were exacerbations, mortality, hospitalizations, and pneumonia. Secondary outcomes included oropharyngeal candidiasis and health-related QOL.

The LABA-plus-ICS group had lower rates of exacerbations than the LABA group, but the data were of low quality because of significant heterogeneity among studies and high rates of attrition. No significant difference in mortality or hospitalizations was found between the groups. The risk of pneumonia in the LABA-plus-ICS group was higher than in the LABA-alone group, with a NNH of 48.

Candidiasis occurred more often in patients on combination fluticasone and salmeterol than salmeterol alone, with a NNH of 22. QOL scores (measured by the SGRQ) in patients on combination therapy were statistically better, but clinically insignificant.

Discontinuing ICS doesn’t increase exacerbations

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs that enrolled a total of 877 patients with COPD compared the number of exacerbations in patients who continued fluticasone 500 mcg inhaled twice daily and patients who were withdrawn from the medication. All patients had been treated with ICS for at least 3 months, and had been on fluticasone for at least 2 weeks. Subjects had a baseline FEV1 between 25% and 80% predicted. No significant increase in exacerbations occurred after discontinuing ICS.4

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society, in a joint guideline, recommend against using ICS as monotherapy for patients with stable COPD. They acknowledge that these drugs are superior to placebo in reducing exacerbations, but note that concerns about their side-effect profile (thrush, potential for bone loss, and moderate to severe easy bruisability) make them less desirable than LABAs or long-acting inhaled anticholinergics.5

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease likewise discourages long-term use of ICS because of the risk of pneumonia and fractures.6 Both groups note that patients with severe COPD may benefit from a combination of ICS and a long-acting medication (usually a LABA).

1. Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD002991.

2. Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2:75-79.

3. Nannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD006829.

4. Nadeem NJ, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SM. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in individuals with COPD—a systemic review and comment on trial methodology. Respir Res. 2011;12:107.

5. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al; American College of Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

6. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2014. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report2014_Feb07.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2013.

1. Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD002991.

2. Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2:75-79.

3. Nannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD006829.

4. Nadeem NJ, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SM. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in individuals with COPD—a systemic review and comment on trial methodology. Respir Res. 2011;12:107.

5. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al; American College of Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

6. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2014. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report2014_Feb07.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2013.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

How do hydrochlorothiazide and chlorthalidone compare for treating hypertension?

Both medications reduce theincidence of cardiovascular events in patients with hypertension, but chlorthalidone may confer additional cardiovascular risk reduction (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, conflicting network meta-analysis and cohort studies). (No head-to-head studies of hydrochlorothiazide [HCTZ] and chlorthalidone have been done.)

Serious hypokalemia and hyponatremia can occur with either medication; it is unclear if the rates of these adverse effects are the same at equivalent doses. Patients taking chlorthalidone are less likely to need a second antihypertensive medication but more likely to be nonadherent than patients taking HCTZ (SOR: B, cohort studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A network meta-analysis—designed to compare 2 interventions that haven’t been studied head-to-head—examined 9 trials that evaluated cardiovascular outcomes in 18,000 patients taking HCTZ and 60,000 patients taking chlorthalidone against outcomes for placebo or other antihypertensive agents.1 Daily doses ranged from 12.5 to 25 mg for HCTZ and 12.5 to 100 mg for chlorthalidone (although most patients taking chlorthalidone were on 12.5-25 mg).

In a drug-adjusted analysis using shared comparator medications, chlorthalidone proved superior to HCTZ in reducing the risk of both heart failure (relative risk [RR]=0.77; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.61-0.98) and combined cardiovascular events—myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, a new diagnosis of coronary artery disease, and new-onset congestive heart failure (RR=0.79; 95% CI, 0.72-0.88).

After adjusting for achieved blood pressure, chlorthalidone was still associated with lower rates of cardiovascular events than HCTZ (RR=0.82; 95% CI, 0.70-0.97). Relative to HCTZ, the number needed to treat with chlorthalidone to prevent 1 additional cardiovascular event over 5 years was 27. Because network meta-analyses draw from a wider body of research than standard meta-analyses, they may be weakened by increased variability in study design and patient demographics.

But another study shows no significant difference in cardiovascular outcomes

A subsequent retrospective cohort study didn’t find a significant difference in cardiovascular outcomes between HCTZ and chlorthalidone. The study compared pooled cardiovascular outcomes (MI, heart failure, and stroke) in 10,400 patients recently started on chlorthalidone and 19,500 started on HCTZ.2 Initial doses were typically either 25 mg chlorthalidone (70% of patients on chlorthalidone) or 12.5 mg HCTZ (67% of patients on HCTZ). The median follow-up was about a year, but lasted as long as 5 years in some cases.

The 2 groups showed no significant difference in cardiovascular events (3.2 events per 100 person-years for chlorthalidone compared with 3.4 for HCTZ; adjusted hazard ratio [aHR]=0.93; 95% CI, 0.81-1.06).

Serious hypokalemia and hyponatremia are risks

Patients taking chlorthalidone were more likely to be hospitalized for hypokalemia (0.69 per 100 person-years vs 0.27 for HCTZ; aHR=3.1; 95% CI, 2.0-4.6; number needed to harm [NNH]=238 in 1 year) or hyponatremia (0.69 per 100 person-years vs 0.49 for HCTZ; aHR=1.7; 95% CI, 1.2-2.3; NNH=434 in 1 year).2 However, the all-cause hospitalization rates for the 2 drugs were the same (aHR=1.0; 95% CI, 0.93-1.07).

Lower systolic BP and serum potassium found with chlorthalidone

A smaller retrospective cohort analysis (6441 participants who received either chlorthalidone or HCTZ starting at 50 mg and stepped once to 100 mg) also assessed the difference in cardiovascular events between patients taking the 2 drugs.3 (Cardiovascular events were defined as pooled MIs, onset of angina or peripheral artery occlusive disease, or need for coronary artery bypass.) Although significant reductions in pooled events occurred in both groups over the 7-year study, these reductions were significantly lower in the chlorthalidone group than in the HCTZ group (aHR=0.79; 95% CI, 0.68-0.92).

Systolic blood pressures were statistically lower in the chlorthalidone group during Years 1 through 5 but not in Years 6 and 7 (difference 2-4 mm Hg). Serum potassium was also lower in patients taking chlorthalidone (3.8 mEq/L on chlorthalidone vs 4.0 mEq/L on HCTZ after 7 years; P<.05).

Chlorthalidone users more responsive, but less adherent than HCTZ users

A retrospective cohort study investigated medication tolerance in veterans who had recently started either HCTZ (120,000 patients) or chlorthalidone (2200 patients) and were followed for a year.4 Most received doses between 12.5 and 25 mg of active drug.

One primary outcome was “nonpersistence,” defined as failure to refill the medication after double the number of days as the initial prescription. The other was “insufficient response,” defined as the need to start another antihypertensive medication. Chlorthalidone users were less likely than HCTZ users to have an insufficient response (odds ratio [OR]=0.71; 95% CI, 0.63-0.80) but more likely to exhibit nonpersistence (OR=1.6; 95% CI, 1.5-1.8).

RECOMMENDATIONS

For primary hypertension, the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends diuretic monotherapy in patients older than 55 years who are poor candidates for calcium channel blockers.5 If a diuretic is to be initiated or changed, NICE recommends chlorthalidone (12.5-25 mg daily) or indapamide (1.5-2.5 mg daily) in preference to HCTZ. The guideline set forth in the eighth annual report of the United States Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure makes no distinction between chlorthalidone and HCTZ; it refers only to “thiazidetype diuretics.” Thiazide-type diuretics are listed as one option (along with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and calcium channel blockers) for initial monotherapy in nonblack patients.6

1. Roush GC, Holford TR, Guddati AK. Chlorthalidone compared with hydrochlorothiazide in reducing cardiovascular events: systematic review and network meta-analyses. Hypertension. 2012;59:1110–1117.

2. Dhalla IA, Gomes T, Yao Z, et al. Chlorthalidone versus hydrochlorothiazide for the treatment of hypertension in older adults: a population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:447–455.

3. Dorsh MP, Gillespie BW, Erickson SR, et al. Chlorthalidone reduces cardiovascular events compared with hydrochlorothiazide: a retrospective cohort analysis. Hypertension. 2011;57:689–694.

4. Lund BC, Ernst ME. The comparative effectiveness of hydrochlorothiazide and chlorthalidone in an observational cohort of veterans. J Clin Hypertension. 2012;14:623–629.

5. Hypertension: clinical management of primary hypertension in adults. (NICE Clinical Guideline 127). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Web site. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2011. Available at: www.nice.org.UK/guidance/CG127. Accessed December 16, 2013.

6. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC8). JAMA. 2014;311:507-520.

Both medications reduce theincidence of cardiovascular events in patients with hypertension, but chlorthalidone may confer additional cardiovascular risk reduction (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, conflicting network meta-analysis and cohort studies). (No head-to-head studies of hydrochlorothiazide [HCTZ] and chlorthalidone have been done.)

Serious hypokalemia and hyponatremia can occur with either medication; it is unclear if the rates of these adverse effects are the same at equivalent doses. Patients taking chlorthalidone are less likely to need a second antihypertensive medication but more likely to be nonadherent than patients taking HCTZ (SOR: B, cohort studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A network meta-analysis—designed to compare 2 interventions that haven’t been studied head-to-head—examined 9 trials that evaluated cardiovascular outcomes in 18,000 patients taking HCTZ and 60,000 patients taking chlorthalidone against outcomes for placebo or other antihypertensive agents.1 Daily doses ranged from 12.5 to 25 mg for HCTZ and 12.5 to 100 mg for chlorthalidone (although most patients taking chlorthalidone were on 12.5-25 mg).

In a drug-adjusted analysis using shared comparator medications, chlorthalidone proved superior to HCTZ in reducing the risk of both heart failure (relative risk [RR]=0.77; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.61-0.98) and combined cardiovascular events—myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, a new diagnosis of coronary artery disease, and new-onset congestive heart failure (RR=0.79; 95% CI, 0.72-0.88).

After adjusting for achieved blood pressure, chlorthalidone was still associated with lower rates of cardiovascular events than HCTZ (RR=0.82; 95% CI, 0.70-0.97). Relative to HCTZ, the number needed to treat with chlorthalidone to prevent 1 additional cardiovascular event over 5 years was 27. Because network meta-analyses draw from a wider body of research than standard meta-analyses, they may be weakened by increased variability in study design and patient demographics.

But another study shows no significant difference in cardiovascular outcomes

A subsequent retrospective cohort study didn’t find a significant difference in cardiovascular outcomes between HCTZ and chlorthalidone. The study compared pooled cardiovascular outcomes (MI, heart failure, and stroke) in 10,400 patients recently started on chlorthalidone and 19,500 started on HCTZ.2 Initial doses were typically either 25 mg chlorthalidone (70% of patients on chlorthalidone) or 12.5 mg HCTZ (67% of patients on HCTZ). The median follow-up was about a year, but lasted as long as 5 years in some cases.

The 2 groups showed no significant difference in cardiovascular events (3.2 events per 100 person-years for chlorthalidone compared with 3.4 for HCTZ; adjusted hazard ratio [aHR]=0.93; 95% CI, 0.81-1.06).

Serious hypokalemia and hyponatremia are risks

Patients taking chlorthalidone were more likely to be hospitalized for hypokalemia (0.69 per 100 person-years vs 0.27 for HCTZ; aHR=3.1; 95% CI, 2.0-4.6; number needed to harm [NNH]=238 in 1 year) or hyponatremia (0.69 per 100 person-years vs 0.49 for HCTZ; aHR=1.7; 95% CI, 1.2-2.3; NNH=434 in 1 year).2 However, the all-cause hospitalization rates for the 2 drugs were the same (aHR=1.0; 95% CI, 0.93-1.07).

Lower systolic BP and serum potassium found with chlorthalidone

A smaller retrospective cohort analysis (6441 participants who received either chlorthalidone or HCTZ starting at 50 mg and stepped once to 100 mg) also assessed the difference in cardiovascular events between patients taking the 2 drugs.3 (Cardiovascular events were defined as pooled MIs, onset of angina or peripheral artery occlusive disease, or need for coronary artery bypass.) Although significant reductions in pooled events occurred in both groups over the 7-year study, these reductions were significantly lower in the chlorthalidone group than in the HCTZ group (aHR=0.79; 95% CI, 0.68-0.92).

Systolic blood pressures were statistically lower in the chlorthalidone group during Years 1 through 5 but not in Years 6 and 7 (difference 2-4 mm Hg). Serum potassium was also lower in patients taking chlorthalidone (3.8 mEq/L on chlorthalidone vs 4.0 mEq/L on HCTZ after 7 years; P<.05).

Chlorthalidone users more responsive, but less adherent than HCTZ users

A retrospective cohort study investigated medication tolerance in veterans who had recently started either HCTZ (120,000 patients) or chlorthalidone (2200 patients) and were followed for a year.4 Most received doses between 12.5 and 25 mg of active drug.

One primary outcome was “nonpersistence,” defined as failure to refill the medication after double the number of days as the initial prescription. The other was “insufficient response,” defined as the need to start another antihypertensive medication. Chlorthalidone users were less likely than HCTZ users to have an insufficient response (odds ratio [OR]=0.71; 95% CI, 0.63-0.80) but more likely to exhibit nonpersistence (OR=1.6; 95% CI, 1.5-1.8).

RECOMMENDATIONS

For primary hypertension, the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends diuretic monotherapy in patients older than 55 years who are poor candidates for calcium channel blockers.5 If a diuretic is to be initiated or changed, NICE recommends chlorthalidone (12.5-25 mg daily) or indapamide (1.5-2.5 mg daily) in preference to HCTZ. The guideline set forth in the eighth annual report of the United States Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure makes no distinction between chlorthalidone and HCTZ; it refers only to “thiazidetype diuretics.” Thiazide-type diuretics are listed as one option (along with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and calcium channel blockers) for initial monotherapy in nonblack patients.6

Both medications reduce theincidence of cardiovascular events in patients with hypertension, but chlorthalidone may confer additional cardiovascular risk reduction (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, conflicting network meta-analysis and cohort studies). (No head-to-head studies of hydrochlorothiazide [HCTZ] and chlorthalidone have been done.)

Serious hypokalemia and hyponatremia can occur with either medication; it is unclear if the rates of these adverse effects are the same at equivalent doses. Patients taking chlorthalidone are less likely to need a second antihypertensive medication but more likely to be nonadherent than patients taking HCTZ (SOR: B, cohort studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A network meta-analysis—designed to compare 2 interventions that haven’t been studied head-to-head—examined 9 trials that evaluated cardiovascular outcomes in 18,000 patients taking HCTZ and 60,000 patients taking chlorthalidone against outcomes for placebo or other antihypertensive agents.1 Daily doses ranged from 12.5 to 25 mg for HCTZ and 12.5 to 100 mg for chlorthalidone (although most patients taking chlorthalidone were on 12.5-25 mg).

In a drug-adjusted analysis using shared comparator medications, chlorthalidone proved superior to HCTZ in reducing the risk of both heart failure (relative risk [RR]=0.77; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.61-0.98) and combined cardiovascular events—myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, a new diagnosis of coronary artery disease, and new-onset congestive heart failure (RR=0.79; 95% CI, 0.72-0.88).

After adjusting for achieved blood pressure, chlorthalidone was still associated with lower rates of cardiovascular events than HCTZ (RR=0.82; 95% CI, 0.70-0.97). Relative to HCTZ, the number needed to treat with chlorthalidone to prevent 1 additional cardiovascular event over 5 years was 27. Because network meta-analyses draw from a wider body of research than standard meta-analyses, they may be weakened by increased variability in study design and patient demographics.

But another study shows no significant difference in cardiovascular outcomes

A subsequent retrospective cohort study didn’t find a significant difference in cardiovascular outcomes between HCTZ and chlorthalidone. The study compared pooled cardiovascular outcomes (MI, heart failure, and stroke) in 10,400 patients recently started on chlorthalidone and 19,500 started on HCTZ.2 Initial doses were typically either 25 mg chlorthalidone (70% of patients on chlorthalidone) or 12.5 mg HCTZ (67% of patients on HCTZ). The median follow-up was about a year, but lasted as long as 5 years in some cases.

The 2 groups showed no significant difference in cardiovascular events (3.2 events per 100 person-years for chlorthalidone compared with 3.4 for HCTZ; adjusted hazard ratio [aHR]=0.93; 95% CI, 0.81-1.06).

Serious hypokalemia and hyponatremia are risks

Patients taking chlorthalidone were more likely to be hospitalized for hypokalemia (0.69 per 100 person-years vs 0.27 for HCTZ; aHR=3.1; 95% CI, 2.0-4.6; number needed to harm [NNH]=238 in 1 year) or hyponatremia (0.69 per 100 person-years vs 0.49 for HCTZ; aHR=1.7; 95% CI, 1.2-2.3; NNH=434 in 1 year).2 However, the all-cause hospitalization rates for the 2 drugs were the same (aHR=1.0; 95% CI, 0.93-1.07).

Lower systolic BP and serum potassium found with chlorthalidone

A smaller retrospective cohort analysis (6441 participants who received either chlorthalidone or HCTZ starting at 50 mg and stepped once to 100 mg) also assessed the difference in cardiovascular events between patients taking the 2 drugs.3 (Cardiovascular events were defined as pooled MIs, onset of angina or peripheral artery occlusive disease, or need for coronary artery bypass.) Although significant reductions in pooled events occurred in both groups over the 7-year study, these reductions were significantly lower in the chlorthalidone group than in the HCTZ group (aHR=0.79; 95% CI, 0.68-0.92).

Systolic blood pressures were statistically lower in the chlorthalidone group during Years 1 through 5 but not in Years 6 and 7 (difference 2-4 mm Hg). Serum potassium was also lower in patients taking chlorthalidone (3.8 mEq/L on chlorthalidone vs 4.0 mEq/L on HCTZ after 7 years; P<.05).

Chlorthalidone users more responsive, but less adherent than HCTZ users

A retrospective cohort study investigated medication tolerance in veterans who had recently started either HCTZ (120,000 patients) or chlorthalidone (2200 patients) and were followed for a year.4 Most received doses between 12.5 and 25 mg of active drug.

One primary outcome was “nonpersistence,” defined as failure to refill the medication after double the number of days as the initial prescription. The other was “insufficient response,” defined as the need to start another antihypertensive medication. Chlorthalidone users were less likely than HCTZ users to have an insufficient response (odds ratio [OR]=0.71; 95% CI, 0.63-0.80) but more likely to exhibit nonpersistence (OR=1.6; 95% CI, 1.5-1.8).

RECOMMENDATIONS

For primary hypertension, the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends diuretic monotherapy in patients older than 55 years who are poor candidates for calcium channel blockers.5 If a diuretic is to be initiated or changed, NICE recommends chlorthalidone (12.5-25 mg daily) or indapamide (1.5-2.5 mg daily) in preference to HCTZ. The guideline set forth in the eighth annual report of the United States Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure makes no distinction between chlorthalidone and HCTZ; it refers only to “thiazidetype diuretics.” Thiazide-type diuretics are listed as one option (along with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and calcium channel blockers) for initial monotherapy in nonblack patients.6

1. Roush GC, Holford TR, Guddati AK. Chlorthalidone compared with hydrochlorothiazide in reducing cardiovascular events: systematic review and network meta-analyses. Hypertension. 2012;59:1110–1117.

2. Dhalla IA, Gomes T, Yao Z, et al. Chlorthalidone versus hydrochlorothiazide for the treatment of hypertension in older adults: a population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:447–455.

3. Dorsh MP, Gillespie BW, Erickson SR, et al. Chlorthalidone reduces cardiovascular events compared with hydrochlorothiazide: a retrospective cohort analysis. Hypertension. 2011;57:689–694.

4. Lund BC, Ernst ME. The comparative effectiveness of hydrochlorothiazide and chlorthalidone in an observational cohort of veterans. J Clin Hypertension. 2012;14:623–629.

5. Hypertension: clinical management of primary hypertension in adults. (NICE Clinical Guideline 127). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Web site. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2011. Available at: www.nice.org.UK/guidance/CG127. Accessed December 16, 2013.

6. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC8). JAMA. 2014;311:507-520.

1. Roush GC, Holford TR, Guddati AK. Chlorthalidone compared with hydrochlorothiazide in reducing cardiovascular events: systematic review and network meta-analyses. Hypertension. 2012;59:1110–1117.

2. Dhalla IA, Gomes T, Yao Z, et al. Chlorthalidone versus hydrochlorothiazide for the treatment of hypertension in older adults: a population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:447–455.

3. Dorsh MP, Gillespie BW, Erickson SR, et al. Chlorthalidone reduces cardiovascular events compared with hydrochlorothiazide: a retrospective cohort analysis. Hypertension. 2011;57:689–694.

4. Lund BC, Ernst ME. The comparative effectiveness of hydrochlorothiazide and chlorthalidone in an observational cohort of veterans. J Clin Hypertension. 2012;14:623–629.

5. Hypertension: clinical management of primary hypertension in adults. (NICE Clinical Guideline 127). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Web site. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2011. Available at: www.nice.org.UK/guidance/CG127. Accessed December 16, 2013.

6. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC8). JAMA. 2014;311:507-520.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Do dietary choices alone alter the risk of developing metabolic syndrome?

YES, but not in the short term. In studies of patient populations controlled for differences in dietary content alone, independent of weight loss or exercise changes, diets with high glycemic index foods, low whole grain and fiber content, and low fruit and vegetable content are associated with an increased incidence of metabolic syndrome (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, multiple large cohort studies).

In the short term, however, switching patients at high risk for metabolic syndrome from a high- to low-glycemic index diet doesn’t improve serum markers of metabolic syndrome (SOR: C, a small randomized controlled trial).

Evidence summary

Six studies (5 cohort studies and one randomized crossover study) attempted to isolate specific dietary components as risk factors for metabolic syndrome, by performing multivariate analyses to control for weight and exercise habits. The cohort studies all used the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III definition of metabolic syndrome. Overall, consumption of foods with a high glycemic index was associated with an increased risk of metabolic syndrome.

A cohort study that evaluated the diet, body habitus, and serum metabolic parameters of 2834 US adults using a validated, interviewer-administered food frequency questionnaire found that the rate of metabolic syndrome was significantly higher in patients with the highest glycemic index diets (highest vs lowest quintile adjusted odds ratio [aOR]=1.4; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.04-1.9).1 Conversely, metabolic syndrome was less common in subjects who ate diets rich in whole grains (aOR=0.67; 95% CI, 0.48-0.91) and cereal fiber (aOR=0.62; 95% CI, 0.45-0.86).

A second cohort study evaluated the diet, body habitus, and metabolic parameters in 2043 Asian women using the same food frequency questionnaire to obtain dietary history.2 Metabolic syndrome was significantly more common among the women with a high refined carbohydrate intake (highest vs lowest quartile aOR=7.8; 95% CI, 4.7-13).

“Western” diet, lack of diversity associated with metabolic syndrome

Two studies from Iran evaluated the rates of metabolic syndrome according to different dietary patterns. The first evaluated a cohort of 486 female teachers 40 to 60 years of age.3 Investigators characterized dietary patterns as “healthy” (rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains) or “Western” (more meat and refined grains). The more “Western” the dietary pattern became, the more often metabolic syndrome was diagnosed (highest vs lowest quintile aOR=1.7; 95% CI, 1.1-1.9).

In the second study, 581 healthy adults received dietary surveys and were tested for metabolic syndrome.4 Diets were assessed and scored for their diversity. High levels of dietary diversity were inversely associated with metabolic syndrome (highest vs lowest quartile aOR=0.77; 95% CI, 0.59-0.93).

No short-term gain in switching to foods with low glycemic index

Switching to foods with a low glycemic index, however, may not provide much benefit, at least in the short term. An 11-week prospective, double-blind, crossover trial in which 15 overweight patients at risk of developing metabolic syndrome alternated eating foods with high and low glycemic indexes found no significant difference in the serum markers associated with metabolic syndrome (fasting glucose, insulin, and triglyceride levels).5

Recommendations

The 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, jointly issued by the US Department of Agriculture and Health and Human Services, recommend increasing fruit and vegetable intake, eating a variety of vegetables, and consuming at least half of all grains as whole grains.6 The guidelines further recommend limiting consumption of foods that contain refined grains, “especially refined grain foods that contain solid fats, added sugars, and sodium.”

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) encourages consumption of low-glycemic index foods, especially foods rich in fiber and other nutrients. However, the ADA also states that there are “not sufficient, consistent” data to conclude that low-glycemic index diets reduce the risk of diabetes.7

1. McKown NM, Meigs JB, Liu S, et al. Carbohydrate nutrition, insulin resistance, and the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in the Framingham offspring cohort. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:538-546.

2. Radhika G, Van Dam RM, Sudha V, et al. Refined grain consumption and the metabolic syndrome in urban Asian Indians (Chennai urban rural epidemiology study 57). Metabolism. 2009;58:675-681.

3. Esmaillzadeh A, Kimiagar M, Mehrabi Y, et al. Dietary patterns, insulin resistance, and prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:910-918.

4. Azadbakht L, Mirmiran P, Azizi F. Dietary diversity score is favorably associated with the metabolic syndrome in Tehranian adults. Int J Obes (Lond). 2005;29:1361-1367.

5. Vrolix R, Mensink RP. Effects of glycemic load on metabolic risk markers in subjects at increased risk of developing metabolic syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:366-374.