User login

When it’s time for ‘the talk’: Sexuality and your geriatric patient

Recent studies suggest that most older adults maintain sexual interest well into late life; many, however, experience sexual dysfunction. This article provides psychiatric practitioners with current information regarding sexuality and aging, as well as psychiatric and systemic medical comorbidities and sexual side effects of medications. Practice guidelines for assessing and managing sexual dysfunction have been developed for use in many medical specialties, and such guidance would be welcome in psychiatric practice.

This article addresses the myth of “geriatric asexuality” and its potential impact on clinical practice, the effects of age-related physiological changes on sexual activity, the importance of sexuality in the lives of older adults, and sensitive questions clinicians can pose about geriatric sexuality. We also will discuss:

• the importance of including a sexual assessment in the comprehensive psychiatric evaluation

• recognizing sexual dysfunction

• providing appropriate management within a multi-disciplinary, collaborative approach.

Sexuality after 65

Regardless of age, sexual activity can provide a sense of comfort and elicit a positive emotional and physical response.1 Hillman2 defined human sexuality as any combination of sexual behavior, emotional intimacy, and sense of sexual identity.

Sexuality in the aging population generally is an understudied area, obscured by the myth of “geriatric asexuality” and subject to numerous psychosocial variables.1 Previous research, focused on a biological perspective of sexuality, has largely overlooked psychological and social influences.3 It has been assumed that, with age, physical and hormonal changes or chronic illness ordinarily reduce or eliminate sexual desire and sexual behavior.3 However, the majority of older adults (defined as age ≥65) report a moderate-to-high level of sexual interest well into late life.1,3

Sexual function remains a subject often neglected in psychiatry. Sexual dysfunctions, as described in the DSM-5,4 do not include age-related changes in sexual function. In addition to physiological changes, sexual difficulties can result from relationship strain, systemic medical or psychiatric disorders, and sexual side effects of medications.

CASE REPORT

Mr. C, age 71 and married, is being treated for a major depressive episode that followed a course of shingles and persistent postherpetic neuralgia. Medications are: escitalopram, 20 mg/d; pregabalin, 150 mg/d; and ramipril, 5 mg/d. Mr. C is physically active and involved in social activities; he has no substance use history. He attends clinic visits with his wife.

Mr. C reports that despite significant improvement of his depressive and pain symptoms, he now experiences sexual difficulties, which he seems hesitant to discuss in detail. According to his wife, Mr. C appears to lack sexual desire and has difficulty initiating and maintaining an erection. She asks Mr. C’s psychiatrist whether she should stop her estrogen treatment, intended to enhance her sexual function, given that the couple is no longer engaging in sexual intercourse.

Mr. C admits to missing physical intimacy; however, he states, “If I have to make a choice between having sex with my wife and getting this depression out of my head, I’m going to pick getting rid of the depression.” Mrs. C says she is becoming dissatisfied with their marriage and the limited time she and her husband now spend together. Mr. C’s psychiatrist suggests that Mr. C and his wife undergo couples counseling.

Physiological changes with aging

In both women and men, the reproductive system undergoes age-related physiological changes.

Women. In women, the phase of decline in ovarian function and resulting decline in sex steroid production (estradiol and progesterone) is referred to as the climacteric, with menopause being determined retrospectively by the cessation of a menstrual period for 1 year.5

Menopausal symptoms typically occur between age 40 and 58; the average age of menopause is 51.6,7 Both estradiol and progesterone levels decline with menopause, and anovulation and ovarian failure ensue. A more gradual decline of female testosterone levels also occurs with aging, starting in the fourth decade of life.8

Clinical manifestations of menopause include vasomotor symptoms (ie, “hot flushes”), sleep disturbances, anxiety and depressive symptoms, decreased bone mineral density, and increased risk of cardiovascular disease.6,7 Loss of estrogen as well as continued loss of testosterone can result in dyspareunia because of atrophy and decreased vulvar and vaginal lubrication, with sexual excitement achieved less quickly, and a decreased intensity of orgasm.7

Men. Research has shown that testosterone levels are highest in men in the second and third decades, with a subsequent gradual decline.9 Older men with a low testosterone level are described as experiencing “late-onset hypogonadism,” also known by the popularized term “andropause.”10 This is attributed to decreased activity at the testicular and hypothalamic levels.10

Nonetheless, only a small fraction of older men with confirmed androgen deficiency are clinically symptomatic.11,12 Low testosterone is associated with decreased libido; it can hinder morning erections, contribute to erectile dysfunction, and result in erections that require physical stimulation.13

Notably, erectile dysfunction involves several other etiologic factors: psychiatric (eg, relationship difficulties, depression), neurogenic (eg, spinal cord injury), endocrine (eg, hyperprolactinemia), arteriogenic (eg, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus), and drug-induced (eg, antidepressants, antihypertensives).14 A low testosterone level also has been associated with potential cognitive changes, decreased bone mineral density, metabolic syndrome (eg, increased risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus), and cardiovascular mortality.10

Effects on sexual activity. How much age-related physiological changes impact sexual practices in the geriatric population is uncertain. A study following 3,302 women through menopause over 6 years found some decline in sexual activity; however, this decline was not associated with increased sexual pain, decreased desire, or lack of arousal.15 Men continue to find ways to remain sexually active despite physiological changes (eg, erectile difficulties), but the etiology of sexual dysfunction in later life remains multi-modal, involving physical, psychological, and relational factors.16,17

Sexual practices in older adults

Researchers for the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP) have examined sexual activities, behaviors, and problems in >3,000 older community-dwelling men and women across the United States, using information collected from in-home interviews.18 This study found that sexual activity, defined as any mutually voluntary sexual contact with another person, declines with age; however, even in the oldest age group (age 75 to 85), 39% of men and 17% of women reported being sexually active in the last 12 months. Among these persons, 54% reported sexual activity at least 2 times per month; 23% reported having sex at least once a week; and 32% reported engaging in oral sex. Partner availability predicted sexual activity.

Respondents with self-reported poor physical health were more likely to experience sexual problems (eg, difficulty with erection or lubrication, dyspareunia, and lack of pleasure). The most commonly reported reason for sexual inactivity in those with a spouse or other intimate partner was the male partner’s poor physical health.18

A longitudinal study, part of the Women’s Healthy Ageing Project, examined changes in sexual function at late menopause compared with early menopause. Although the researchers also found an age-related decrease in sexual activity, 50% of their late-menopause respondents (mean age, 70; range, 64 to 77) still reported sexual activity in the previous month, with 35% of this subgroup reporting sexual activity at least once a week; 83% reported sexual thoughts or fantasies.19 Availability of a partner, absence of a history of depression, moderate (compared with no) alcohol consumption, and better cognitive function were significantly associated with a higher level of sexual activity.19

In the Successful Aging Evaluation study, conducted in San Diego County, California, community-dwelling older partnered adults age 50 to 99 (mean age, 75) were surveyed about their sexual health after a cognitive screen by telephone20; rating scales for depression, anxiety, and physical function also were included. Results included 41% of men and 35% of women reporting sexual activity at least once a week, and only 21% of men and 24% of women reporting no sexual activity in the previous year. Depressive symptoms were most highly correlated with lack of sexual activity.20

Overall, these studies reveal that positive physical and mental health, access to a healthy partner, and a positive attitude toward sex are correlated with sexual activity in later life, whereas barriers to sexual activity include lack of a healthy sexual partner, depression, and chronic systemic medical illnesses, such as coronary artery disease or type 2 diabetes mellitus.13,17,21-24 Sexual activity and satisfaction have been positively associated with perceived general well-being and self-esteem.25,26 Conversely, sexual difficulties secondary to disease can be a source of distress for couples.27

Possibly overlooked? It is important to note that sexuality itself is a subjective area. Psychological intimacy is a universal phenomenon, and its physical expression may evolve as couples accommodate to age-related bodily changes. Means of achieving physical closeness, other than intercourse (eg, intimate touching, hand holding, kissing, or even acts of caretaking), may not be adequately captured in studies that look specifically at sexual activity.

Taking a sexual history in a geriatric patient

Because sexuality can be an uncomfortable topic for geriatric patients to discuss, sexual problems in this population often go unrecognized. It has been suggested that psychiatrists are more likely to inquire about sexual activity in middle-aged patients than geriatric patients with the same psychiatric presentation—perhaps illustrating a bias against taking a sexual history from a geriatric patient.28 However, because many older patients can experience depression or anxiety disorders in relation to normal sexual changes or sexual dysfunction within the context of their intimate relationships, it is essential to bring these issues to light.

Although a sexual history may not be the focus of a first clinical encounter, consider making such an assessment at a relatively early stage of patient care. The importance of such dialogue is 2-fold:

• It demonstrates to the patient that talking about sexuality in a respectful and empathic manner is appropriate and can encourage patients to communicate more effectively about sexuality with clinicians and with sexual partners.

• It helps elicit medical information needed to make an accurate diagnosis and provide adequate management.

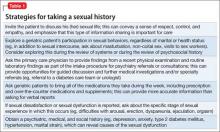

How to begin. As a starting point to taking a sexual history, an open-ended invitation for the geriatric patient to share information may be best, such as “What would you like to tell me about your sexual life?” See further suggestions (Table 1) and examples of more detailed questions to ask once a dialogue has been initiated (Table 2). Additional factors that may contribute to sexual dysfunction are presented in Table 3.1,27,29,30

CASE CONTINUED

In Mr. C’s case, an assessment of his sexual history, including risk factors for sexual dysfunction, is completed. Results from laboratory investigations, including a total testosterone level, are within normal limits.

Mr. C asks about using medications with fewer sexual side effects (he has been taking 3 medications that can contribute to sexual dysfunction). A gradual cross-taper of escitalopram, 20 mg/d, to mirtazapine, 45 mg/d, is implemented, along with tapering pregabalin to 50 mg/d.

Mr. C’s psychiatric and pain symptom improvement is maintained. He notices a boost in his sexual desire but has minimal improvement in erectile dysfunction. He is encouraged to speak with his primary care physician about an antihypertensive agent with less impact on sexual function, as well as therapeutic agents for erectile dysfunction; these, he declines.

At a subsequent visit, Mr. C reports feeling less apprehension about sexual performance. He is now willing to consider further medication options with his primary care physician, and agrees to a recommendation for couples psychotherapy.

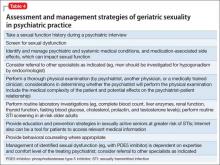

As illustrated in Mr. C’s case, the recommended sexual assessment and management strategies to consider at a minimum in psychiatric practice are listed in Table 4.

STI risk in geriatric patients

The risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), often is overlooked in sexually active older adults. Although STIs are more common among younger adults, there is recent evidence of increased incidence in the geriatric population31 (with the highest risk of incident HIV and some STIs in older men who have sex with men32). These increased rates can be explained, at least in part, by:

• older men being less likely to use a condom during sexual activity

• promotion of viral entry in older women through a drier, thinner vaginal wall

• increased longevity of HIV-positive persons.31

Routine STI screening is not warranted in all older adults, but education and prevention strategies in sexually active seniors who are at greater risk of STIs are recommended. Particularly, clinicians should seek opportunities to discuss risk factors and safe sex practices (eg, using condoms, limiting number of sexual partners, practicing good hygiene, engaging in preventive care), and provide behavioral counseling where appropriate.31,33

Additional considerations in geriatric sexuality

Because psychiatric and systemic medical conditions can hinder sexual function, it is essential to identify and manage these conditions. Several neuropsychiatric disorders, including mood and neurocognitive disorders, can not only cause sexual dysfunction, but also can raise ethical dilemmas for clinicians, such as reduced decisional capacity in cognitively impaired patients to consent to sexual activity.1,34

In some patients, psychological, environmental, and pharmacological treatment options may help. A phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor for erectile dysfunction can be prescribed by the primary care physician, a psychiatrist, or another specialist, depending on the physician’s expertise and comfort level.

Sequencing of sexual dysfunction. Notably, there is a common paradox in mood disorders. Decreased sexual interest or performance may represent an aspect of anhedonia associated with depression, whereas sexual dysfunction could also result from medication use (particularly that of serotonergic antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine inhibitors), even as other depressive symptoms improve. Therefore, it is critical to analyze sequencing of sexual dysfunction—as part of the presenting mood symptoms or dysfunction induced by antidepressant treatment.

Geriatric sexuality in the digital age. Because older adults represent a rapidly growing segment of digital device users,35 Internet use is likely to play a role in the future of sexuality and “digital intimacy,” in that older adults can engage in online sexual activities. The Internet also can be a tool to access medical education.

Related Resources

• Burghardt KJ, Gardner KN. Sildenafil for SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(4):29-32,A.

• Maciel M, Laganà L. Older women’s sexual desire problems: biopsychosocial factors impacting them and barriers to their clinical assessment [published online January 5, 2014]. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:107217. doi: 10.1155/2014/107217.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban Mirtazapine • Remeron

Carbamazepine • Tegretol Oxcarbazepine • Trileptal

Clonidine • Catapres Phenobarbital • Luminal

Donepezil • Aricept Phenytoin • Dilantin

Escitalopram • Lexapro Pregabalin • Lyrica

Gabapentin • Neurontin Ramipril • Altace

Lamotrigine • Lamictal Rivastigmine • Exelon

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid Trazodone • Desyrel

Memantine • Namenda Valproic acid • Depakote

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Jagus CE, Benbow SM. Sexuality in older men with mental health problems. Sex Relation Ther. 2002;17(3):271-279.

2. Hillman JL. Clinical perspectives on elderly sexuality. New York, NY: Springer; 2000.

3. DeLamater JD, Sill M. Sexual desire in later life. J Sex Res. 2005;42(2):138-149.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

5. Laufer LR, Gambone JC. Climacteric: menopause and peri-and postmenopause. In: Hacker NF, Gambone JC, Hobel CJ. Hacker and Moore’s essentials of obstetrics and gynecology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2010:379-385.

6. Wilson MM. Menopause. Clin Geriatr Med. 2003;19(3): 483-506.

7. Reid R, Abramson BL, Blake J, et al. Managing menopause. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2014;36(9):830-838.

8. Horstman AM, Dillon EL, Urban RJ, et al. The role of androgens and estrogens on healthy aging and longevity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(11):1140-1152.

9. Wu FC, Tajar A, Pye SR, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis disruptions in older men are differentially linked to age and modifiable risk factors: the European Male Aging Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(7):2737-2745.

10. Basaria S. Reproductive aging in men. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2013;42(2):255-270.

11. Wu FC, Tajar A, Beynon JM, et al. Identification of late-onset hypogonadism in middle-aged and elderly men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(2):123-135.

12. Araujo AB, Esche GR, Kupelian V, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic androgen deficiency in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(11):4241-4247.

13. Lochlainn MN, Kenny RA. Sexual activity and aging. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(8):565-572.

14. McMahon CG. Erectile dysfunction. Intern Med J. 2014;44(1):18-26.

15. Avis NE, Brockwell S, Randolph JF Jr, et al. Longitudinal changes in sexual functioning as women transition through menopause: results from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Menopause. 2009;16(3):442-452.

16. Perelman M, Shabsigh R, Seftel A, et al. Attitudes of men with erectile dysfunction: a cross-national survey. J Sex Med. 2005;2(3):397-406.

17. Corona G, Rastrelli G, Maseroli E, et al. Sexual function of the ageing male. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;27(4):581-601.

18. Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, et al. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(8):762-774.

19. Lonnèe-Hoffmann RA, Dennerstein L, Lehert P, et al. Sexual function in the late postmenopause: a decade of follow-up in a population-based cohort of Australian women. J Sex Med. 2014;11(8):2029-2038.

20. Wang V, Depp CA, Ceglowski J, et al. Sexual health and function in later life: a population-based study of 606 older adults with a partner. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23(3):227-233.

21. Garrett D. Psychosocial barriers to sexual intimacy for older people. Br J Nurs. 2014;23(6):327-331.

22. DeLamater J, Karraker A. Sexual functioning in older adults. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11(1):6-11.

23. DeLamater J. Sexual expression in later life: a review and synthesis. J Sex Res. 2012;49(2-3):125-141.

24. Inelmen EM, Sergi G, Girardi A, et al. The importance of sexual health in the elderly: breaking down barriers and taboos. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2012;24(suppl 3):31-34.

25. Choi KB, Jang SH, Lee MY, et al. Sexual life and self-esteem in married elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;53(1):e17-e20.

26. Davison SL, Bell RJ, LaChina M, et al. The relationship between self-reported sexual satisfaction and general well-being in women. J Sex Med. 2009;6(10):2690-2697.

27. Morley JE, Tariq SH. Sexuality and disease. Clin Geriatr Med. 2003;19(3):563-573.

28. Bouman WP, Arcelus J. Are psychiatrists guilty of “ageism” when it comes to taking a sexual history? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16(1):27-31.

29. La Torre A, Giupponi G, Duffy DM, et al. Sexual dysfunction related to psychotropic drugs: a critical review. Part III: mood stabilizers and anxiolytic drugs. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2014;47(1):1-6.

30. Tucker I. Management of inappropriate sexual behaviors in dementia: a literature review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010; 22(5):683-692.

31. Imparato T, Sanders D. STD prevalence demands clinical awareness. Aging Well. 2012;5(1):14.

32. Poynten IM, Grulich AE, Templeton DJ. Sexually transmitted infections in older populations. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2013;26(1):80-85.

33. Talashek ML, Tichy AM, Epping H. Sexually transmitted diseases in the elderly—issues and recommendations. J Gerontol Nurs. 1990;16(4):33-40.

34. Benbow SM, Jagus CE. Sexuality in older women with mental health problems. Sex Relation Ther. 2002;17(3):261-270.

35. Veenhof B, Timusk P. Online activities of Canadian boomers and seniors. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/ 11-008-x/2009002/article/10910-eng.htm#tphp. Accessed March 26, 2015.

Recent studies suggest that most older adults maintain sexual interest well into late life; many, however, experience sexual dysfunction. This article provides psychiatric practitioners with current information regarding sexuality and aging, as well as psychiatric and systemic medical comorbidities and sexual side effects of medications. Practice guidelines for assessing and managing sexual dysfunction have been developed for use in many medical specialties, and such guidance would be welcome in psychiatric practice.

This article addresses the myth of “geriatric asexuality” and its potential impact on clinical practice, the effects of age-related physiological changes on sexual activity, the importance of sexuality in the lives of older adults, and sensitive questions clinicians can pose about geriatric sexuality. We also will discuss:

• the importance of including a sexual assessment in the comprehensive psychiatric evaluation

• recognizing sexual dysfunction

• providing appropriate management within a multi-disciplinary, collaborative approach.

Sexuality after 65

Regardless of age, sexual activity can provide a sense of comfort and elicit a positive emotional and physical response.1 Hillman2 defined human sexuality as any combination of sexual behavior, emotional intimacy, and sense of sexual identity.

Sexuality in the aging population generally is an understudied area, obscured by the myth of “geriatric asexuality” and subject to numerous psychosocial variables.1 Previous research, focused on a biological perspective of sexuality, has largely overlooked psychological and social influences.3 It has been assumed that, with age, physical and hormonal changes or chronic illness ordinarily reduce or eliminate sexual desire and sexual behavior.3 However, the majority of older adults (defined as age ≥65) report a moderate-to-high level of sexual interest well into late life.1,3

Sexual function remains a subject often neglected in psychiatry. Sexual dysfunctions, as described in the DSM-5,4 do not include age-related changes in sexual function. In addition to physiological changes, sexual difficulties can result from relationship strain, systemic medical or psychiatric disorders, and sexual side effects of medications.

CASE REPORT

Mr. C, age 71 and married, is being treated for a major depressive episode that followed a course of shingles and persistent postherpetic neuralgia. Medications are: escitalopram, 20 mg/d; pregabalin, 150 mg/d; and ramipril, 5 mg/d. Mr. C is physically active and involved in social activities; he has no substance use history. He attends clinic visits with his wife.

Mr. C reports that despite significant improvement of his depressive and pain symptoms, he now experiences sexual difficulties, which he seems hesitant to discuss in detail. According to his wife, Mr. C appears to lack sexual desire and has difficulty initiating and maintaining an erection. She asks Mr. C’s psychiatrist whether she should stop her estrogen treatment, intended to enhance her sexual function, given that the couple is no longer engaging in sexual intercourse.

Mr. C admits to missing physical intimacy; however, he states, “If I have to make a choice between having sex with my wife and getting this depression out of my head, I’m going to pick getting rid of the depression.” Mrs. C says she is becoming dissatisfied with their marriage and the limited time she and her husband now spend together. Mr. C’s psychiatrist suggests that Mr. C and his wife undergo couples counseling.

Physiological changes with aging

In both women and men, the reproductive system undergoes age-related physiological changes.

Women. In women, the phase of decline in ovarian function and resulting decline in sex steroid production (estradiol and progesterone) is referred to as the climacteric, with menopause being determined retrospectively by the cessation of a menstrual period for 1 year.5

Menopausal symptoms typically occur between age 40 and 58; the average age of menopause is 51.6,7 Both estradiol and progesterone levels decline with menopause, and anovulation and ovarian failure ensue. A more gradual decline of female testosterone levels also occurs with aging, starting in the fourth decade of life.8

Clinical manifestations of menopause include vasomotor symptoms (ie, “hot flushes”), sleep disturbances, anxiety and depressive symptoms, decreased bone mineral density, and increased risk of cardiovascular disease.6,7 Loss of estrogen as well as continued loss of testosterone can result in dyspareunia because of atrophy and decreased vulvar and vaginal lubrication, with sexual excitement achieved less quickly, and a decreased intensity of orgasm.7

Men. Research has shown that testosterone levels are highest in men in the second and third decades, with a subsequent gradual decline.9 Older men with a low testosterone level are described as experiencing “late-onset hypogonadism,” also known by the popularized term “andropause.”10 This is attributed to decreased activity at the testicular and hypothalamic levels.10

Nonetheless, only a small fraction of older men with confirmed androgen deficiency are clinically symptomatic.11,12 Low testosterone is associated with decreased libido; it can hinder morning erections, contribute to erectile dysfunction, and result in erections that require physical stimulation.13

Notably, erectile dysfunction involves several other etiologic factors: psychiatric (eg, relationship difficulties, depression), neurogenic (eg, spinal cord injury), endocrine (eg, hyperprolactinemia), arteriogenic (eg, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus), and drug-induced (eg, antidepressants, antihypertensives).14 A low testosterone level also has been associated with potential cognitive changes, decreased bone mineral density, metabolic syndrome (eg, increased risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus), and cardiovascular mortality.10

Effects on sexual activity. How much age-related physiological changes impact sexual practices in the geriatric population is uncertain. A study following 3,302 women through menopause over 6 years found some decline in sexual activity; however, this decline was not associated with increased sexual pain, decreased desire, or lack of arousal.15 Men continue to find ways to remain sexually active despite physiological changes (eg, erectile difficulties), but the etiology of sexual dysfunction in later life remains multi-modal, involving physical, psychological, and relational factors.16,17

Sexual practices in older adults

Researchers for the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP) have examined sexual activities, behaviors, and problems in >3,000 older community-dwelling men and women across the United States, using information collected from in-home interviews.18 This study found that sexual activity, defined as any mutually voluntary sexual contact with another person, declines with age; however, even in the oldest age group (age 75 to 85), 39% of men and 17% of women reported being sexually active in the last 12 months. Among these persons, 54% reported sexual activity at least 2 times per month; 23% reported having sex at least once a week; and 32% reported engaging in oral sex. Partner availability predicted sexual activity.

Respondents with self-reported poor physical health were more likely to experience sexual problems (eg, difficulty with erection or lubrication, dyspareunia, and lack of pleasure). The most commonly reported reason for sexual inactivity in those with a spouse or other intimate partner was the male partner’s poor physical health.18

A longitudinal study, part of the Women’s Healthy Ageing Project, examined changes in sexual function at late menopause compared with early menopause. Although the researchers also found an age-related decrease in sexual activity, 50% of their late-menopause respondents (mean age, 70; range, 64 to 77) still reported sexual activity in the previous month, with 35% of this subgroup reporting sexual activity at least once a week; 83% reported sexual thoughts or fantasies.19 Availability of a partner, absence of a history of depression, moderate (compared with no) alcohol consumption, and better cognitive function were significantly associated with a higher level of sexual activity.19

In the Successful Aging Evaluation study, conducted in San Diego County, California, community-dwelling older partnered adults age 50 to 99 (mean age, 75) were surveyed about their sexual health after a cognitive screen by telephone20; rating scales for depression, anxiety, and physical function also were included. Results included 41% of men and 35% of women reporting sexual activity at least once a week, and only 21% of men and 24% of women reporting no sexual activity in the previous year. Depressive symptoms were most highly correlated with lack of sexual activity.20

Overall, these studies reveal that positive physical and mental health, access to a healthy partner, and a positive attitude toward sex are correlated with sexual activity in later life, whereas barriers to sexual activity include lack of a healthy sexual partner, depression, and chronic systemic medical illnesses, such as coronary artery disease or type 2 diabetes mellitus.13,17,21-24 Sexual activity and satisfaction have been positively associated with perceived general well-being and self-esteem.25,26 Conversely, sexual difficulties secondary to disease can be a source of distress for couples.27

Possibly overlooked? It is important to note that sexuality itself is a subjective area. Psychological intimacy is a universal phenomenon, and its physical expression may evolve as couples accommodate to age-related bodily changes. Means of achieving physical closeness, other than intercourse (eg, intimate touching, hand holding, kissing, or even acts of caretaking), may not be adequately captured in studies that look specifically at sexual activity.

Taking a sexual history in a geriatric patient

Because sexuality can be an uncomfortable topic for geriatric patients to discuss, sexual problems in this population often go unrecognized. It has been suggested that psychiatrists are more likely to inquire about sexual activity in middle-aged patients than geriatric patients with the same psychiatric presentation—perhaps illustrating a bias against taking a sexual history from a geriatric patient.28 However, because many older patients can experience depression or anxiety disorders in relation to normal sexual changes or sexual dysfunction within the context of their intimate relationships, it is essential to bring these issues to light.

Although a sexual history may not be the focus of a first clinical encounter, consider making such an assessment at a relatively early stage of patient care. The importance of such dialogue is 2-fold:

• It demonstrates to the patient that talking about sexuality in a respectful and empathic manner is appropriate and can encourage patients to communicate more effectively about sexuality with clinicians and with sexual partners.

• It helps elicit medical information needed to make an accurate diagnosis and provide adequate management.

How to begin. As a starting point to taking a sexual history, an open-ended invitation for the geriatric patient to share information may be best, such as “What would you like to tell me about your sexual life?” See further suggestions (Table 1) and examples of more detailed questions to ask once a dialogue has been initiated (Table 2). Additional factors that may contribute to sexual dysfunction are presented in Table 3.1,27,29,30

CASE CONTINUED

In Mr. C’s case, an assessment of his sexual history, including risk factors for sexual dysfunction, is completed. Results from laboratory investigations, including a total testosterone level, are within normal limits.

Mr. C asks about using medications with fewer sexual side effects (he has been taking 3 medications that can contribute to sexual dysfunction). A gradual cross-taper of escitalopram, 20 mg/d, to mirtazapine, 45 mg/d, is implemented, along with tapering pregabalin to 50 mg/d.

Mr. C’s psychiatric and pain symptom improvement is maintained. He notices a boost in his sexual desire but has minimal improvement in erectile dysfunction. He is encouraged to speak with his primary care physician about an antihypertensive agent with less impact on sexual function, as well as therapeutic agents for erectile dysfunction; these, he declines.

At a subsequent visit, Mr. C reports feeling less apprehension about sexual performance. He is now willing to consider further medication options with his primary care physician, and agrees to a recommendation for couples psychotherapy.

As illustrated in Mr. C’s case, the recommended sexual assessment and management strategies to consider at a minimum in psychiatric practice are listed in Table 4.

STI risk in geriatric patients

The risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), often is overlooked in sexually active older adults. Although STIs are more common among younger adults, there is recent evidence of increased incidence in the geriatric population31 (with the highest risk of incident HIV and some STIs in older men who have sex with men32). These increased rates can be explained, at least in part, by:

• older men being less likely to use a condom during sexual activity

• promotion of viral entry in older women through a drier, thinner vaginal wall

• increased longevity of HIV-positive persons.31

Routine STI screening is not warranted in all older adults, but education and prevention strategies in sexually active seniors who are at greater risk of STIs are recommended. Particularly, clinicians should seek opportunities to discuss risk factors and safe sex practices (eg, using condoms, limiting number of sexual partners, practicing good hygiene, engaging in preventive care), and provide behavioral counseling where appropriate.31,33

Additional considerations in geriatric sexuality

Because psychiatric and systemic medical conditions can hinder sexual function, it is essential to identify and manage these conditions. Several neuropsychiatric disorders, including mood and neurocognitive disorders, can not only cause sexual dysfunction, but also can raise ethical dilemmas for clinicians, such as reduced decisional capacity in cognitively impaired patients to consent to sexual activity.1,34

In some patients, psychological, environmental, and pharmacological treatment options may help. A phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor for erectile dysfunction can be prescribed by the primary care physician, a psychiatrist, or another specialist, depending on the physician’s expertise and comfort level.

Sequencing of sexual dysfunction. Notably, there is a common paradox in mood disorders. Decreased sexual interest or performance may represent an aspect of anhedonia associated with depression, whereas sexual dysfunction could also result from medication use (particularly that of serotonergic antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine inhibitors), even as other depressive symptoms improve. Therefore, it is critical to analyze sequencing of sexual dysfunction—as part of the presenting mood symptoms or dysfunction induced by antidepressant treatment.

Geriatric sexuality in the digital age. Because older adults represent a rapidly growing segment of digital device users,35 Internet use is likely to play a role in the future of sexuality and “digital intimacy,” in that older adults can engage in online sexual activities. The Internet also can be a tool to access medical education.

Related Resources

• Burghardt KJ, Gardner KN. Sildenafil for SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(4):29-32,A.

• Maciel M, Laganà L. Older women’s sexual desire problems: biopsychosocial factors impacting them and barriers to their clinical assessment [published online January 5, 2014]. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:107217. doi: 10.1155/2014/107217.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban Mirtazapine • Remeron

Carbamazepine • Tegretol Oxcarbazepine • Trileptal

Clonidine • Catapres Phenobarbital • Luminal

Donepezil • Aricept Phenytoin • Dilantin

Escitalopram • Lexapro Pregabalin • Lyrica

Gabapentin • Neurontin Ramipril • Altace

Lamotrigine • Lamictal Rivastigmine • Exelon

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid Trazodone • Desyrel

Memantine • Namenda Valproic acid • Depakote

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Recent studies suggest that most older adults maintain sexual interest well into late life; many, however, experience sexual dysfunction. This article provides psychiatric practitioners with current information regarding sexuality and aging, as well as psychiatric and systemic medical comorbidities and sexual side effects of medications. Practice guidelines for assessing and managing sexual dysfunction have been developed for use in many medical specialties, and such guidance would be welcome in psychiatric practice.

This article addresses the myth of “geriatric asexuality” and its potential impact on clinical practice, the effects of age-related physiological changes on sexual activity, the importance of sexuality in the lives of older adults, and sensitive questions clinicians can pose about geriatric sexuality. We also will discuss:

• the importance of including a sexual assessment in the comprehensive psychiatric evaluation

• recognizing sexual dysfunction

• providing appropriate management within a multi-disciplinary, collaborative approach.

Sexuality after 65

Regardless of age, sexual activity can provide a sense of comfort and elicit a positive emotional and physical response.1 Hillman2 defined human sexuality as any combination of sexual behavior, emotional intimacy, and sense of sexual identity.

Sexuality in the aging population generally is an understudied area, obscured by the myth of “geriatric asexuality” and subject to numerous psychosocial variables.1 Previous research, focused on a biological perspective of sexuality, has largely overlooked psychological and social influences.3 It has been assumed that, with age, physical and hormonal changes or chronic illness ordinarily reduce or eliminate sexual desire and sexual behavior.3 However, the majority of older adults (defined as age ≥65) report a moderate-to-high level of sexual interest well into late life.1,3

Sexual function remains a subject often neglected in psychiatry. Sexual dysfunctions, as described in the DSM-5,4 do not include age-related changes in sexual function. In addition to physiological changes, sexual difficulties can result from relationship strain, systemic medical or psychiatric disorders, and sexual side effects of medications.

CASE REPORT

Mr. C, age 71 and married, is being treated for a major depressive episode that followed a course of shingles and persistent postherpetic neuralgia. Medications are: escitalopram, 20 mg/d; pregabalin, 150 mg/d; and ramipril, 5 mg/d. Mr. C is physically active and involved in social activities; he has no substance use history. He attends clinic visits with his wife.

Mr. C reports that despite significant improvement of his depressive and pain symptoms, he now experiences sexual difficulties, which he seems hesitant to discuss in detail. According to his wife, Mr. C appears to lack sexual desire and has difficulty initiating and maintaining an erection. She asks Mr. C’s psychiatrist whether she should stop her estrogen treatment, intended to enhance her sexual function, given that the couple is no longer engaging in sexual intercourse.

Mr. C admits to missing physical intimacy; however, he states, “If I have to make a choice between having sex with my wife and getting this depression out of my head, I’m going to pick getting rid of the depression.” Mrs. C says she is becoming dissatisfied with their marriage and the limited time she and her husband now spend together. Mr. C’s psychiatrist suggests that Mr. C and his wife undergo couples counseling.

Physiological changes with aging

In both women and men, the reproductive system undergoes age-related physiological changes.

Women. In women, the phase of decline in ovarian function and resulting decline in sex steroid production (estradiol and progesterone) is referred to as the climacteric, with menopause being determined retrospectively by the cessation of a menstrual period for 1 year.5

Menopausal symptoms typically occur between age 40 and 58; the average age of menopause is 51.6,7 Both estradiol and progesterone levels decline with menopause, and anovulation and ovarian failure ensue. A more gradual decline of female testosterone levels also occurs with aging, starting in the fourth decade of life.8

Clinical manifestations of menopause include vasomotor symptoms (ie, “hot flushes”), sleep disturbances, anxiety and depressive symptoms, decreased bone mineral density, and increased risk of cardiovascular disease.6,7 Loss of estrogen as well as continued loss of testosterone can result in dyspareunia because of atrophy and decreased vulvar and vaginal lubrication, with sexual excitement achieved less quickly, and a decreased intensity of orgasm.7

Men. Research has shown that testosterone levels are highest in men in the second and third decades, with a subsequent gradual decline.9 Older men with a low testosterone level are described as experiencing “late-onset hypogonadism,” also known by the popularized term “andropause.”10 This is attributed to decreased activity at the testicular and hypothalamic levels.10

Nonetheless, only a small fraction of older men with confirmed androgen deficiency are clinically symptomatic.11,12 Low testosterone is associated with decreased libido; it can hinder morning erections, contribute to erectile dysfunction, and result in erections that require physical stimulation.13

Notably, erectile dysfunction involves several other etiologic factors: psychiatric (eg, relationship difficulties, depression), neurogenic (eg, spinal cord injury), endocrine (eg, hyperprolactinemia), arteriogenic (eg, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus), and drug-induced (eg, antidepressants, antihypertensives).14 A low testosterone level also has been associated with potential cognitive changes, decreased bone mineral density, metabolic syndrome (eg, increased risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus), and cardiovascular mortality.10

Effects on sexual activity. How much age-related physiological changes impact sexual practices in the geriatric population is uncertain. A study following 3,302 women through menopause over 6 years found some decline in sexual activity; however, this decline was not associated with increased sexual pain, decreased desire, or lack of arousal.15 Men continue to find ways to remain sexually active despite physiological changes (eg, erectile difficulties), but the etiology of sexual dysfunction in later life remains multi-modal, involving physical, psychological, and relational factors.16,17

Sexual practices in older adults

Researchers for the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP) have examined sexual activities, behaviors, and problems in >3,000 older community-dwelling men and women across the United States, using information collected from in-home interviews.18 This study found that sexual activity, defined as any mutually voluntary sexual contact with another person, declines with age; however, even in the oldest age group (age 75 to 85), 39% of men and 17% of women reported being sexually active in the last 12 months. Among these persons, 54% reported sexual activity at least 2 times per month; 23% reported having sex at least once a week; and 32% reported engaging in oral sex. Partner availability predicted sexual activity.

Respondents with self-reported poor physical health were more likely to experience sexual problems (eg, difficulty with erection or lubrication, dyspareunia, and lack of pleasure). The most commonly reported reason for sexual inactivity in those with a spouse or other intimate partner was the male partner’s poor physical health.18

A longitudinal study, part of the Women’s Healthy Ageing Project, examined changes in sexual function at late menopause compared with early menopause. Although the researchers also found an age-related decrease in sexual activity, 50% of their late-menopause respondents (mean age, 70; range, 64 to 77) still reported sexual activity in the previous month, with 35% of this subgroup reporting sexual activity at least once a week; 83% reported sexual thoughts or fantasies.19 Availability of a partner, absence of a history of depression, moderate (compared with no) alcohol consumption, and better cognitive function were significantly associated with a higher level of sexual activity.19

In the Successful Aging Evaluation study, conducted in San Diego County, California, community-dwelling older partnered adults age 50 to 99 (mean age, 75) were surveyed about their sexual health after a cognitive screen by telephone20; rating scales for depression, anxiety, and physical function also were included. Results included 41% of men and 35% of women reporting sexual activity at least once a week, and only 21% of men and 24% of women reporting no sexual activity in the previous year. Depressive symptoms were most highly correlated with lack of sexual activity.20

Overall, these studies reveal that positive physical and mental health, access to a healthy partner, and a positive attitude toward sex are correlated with sexual activity in later life, whereas barriers to sexual activity include lack of a healthy sexual partner, depression, and chronic systemic medical illnesses, such as coronary artery disease or type 2 diabetes mellitus.13,17,21-24 Sexual activity and satisfaction have been positively associated with perceived general well-being and self-esteem.25,26 Conversely, sexual difficulties secondary to disease can be a source of distress for couples.27

Possibly overlooked? It is important to note that sexuality itself is a subjective area. Psychological intimacy is a universal phenomenon, and its physical expression may evolve as couples accommodate to age-related bodily changes. Means of achieving physical closeness, other than intercourse (eg, intimate touching, hand holding, kissing, or even acts of caretaking), may not be adequately captured in studies that look specifically at sexual activity.

Taking a sexual history in a geriatric patient

Because sexuality can be an uncomfortable topic for geriatric patients to discuss, sexual problems in this population often go unrecognized. It has been suggested that psychiatrists are more likely to inquire about sexual activity in middle-aged patients than geriatric patients with the same psychiatric presentation—perhaps illustrating a bias against taking a sexual history from a geriatric patient.28 However, because many older patients can experience depression or anxiety disorders in relation to normal sexual changes or sexual dysfunction within the context of their intimate relationships, it is essential to bring these issues to light.

Although a sexual history may not be the focus of a first clinical encounter, consider making such an assessment at a relatively early stage of patient care. The importance of such dialogue is 2-fold:

• It demonstrates to the patient that talking about sexuality in a respectful and empathic manner is appropriate and can encourage patients to communicate more effectively about sexuality with clinicians and with sexual partners.

• It helps elicit medical information needed to make an accurate diagnosis and provide adequate management.

How to begin. As a starting point to taking a sexual history, an open-ended invitation for the geriatric patient to share information may be best, such as “What would you like to tell me about your sexual life?” See further suggestions (Table 1) and examples of more detailed questions to ask once a dialogue has been initiated (Table 2). Additional factors that may contribute to sexual dysfunction are presented in Table 3.1,27,29,30

CASE CONTINUED

In Mr. C’s case, an assessment of his sexual history, including risk factors for sexual dysfunction, is completed. Results from laboratory investigations, including a total testosterone level, are within normal limits.

Mr. C asks about using medications with fewer sexual side effects (he has been taking 3 medications that can contribute to sexual dysfunction). A gradual cross-taper of escitalopram, 20 mg/d, to mirtazapine, 45 mg/d, is implemented, along with tapering pregabalin to 50 mg/d.

Mr. C’s psychiatric and pain symptom improvement is maintained. He notices a boost in his sexual desire but has minimal improvement in erectile dysfunction. He is encouraged to speak with his primary care physician about an antihypertensive agent with less impact on sexual function, as well as therapeutic agents for erectile dysfunction; these, he declines.

At a subsequent visit, Mr. C reports feeling less apprehension about sexual performance. He is now willing to consider further medication options with his primary care physician, and agrees to a recommendation for couples psychotherapy.

As illustrated in Mr. C’s case, the recommended sexual assessment and management strategies to consider at a minimum in psychiatric practice are listed in Table 4.

STI risk in geriatric patients

The risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), often is overlooked in sexually active older adults. Although STIs are more common among younger adults, there is recent evidence of increased incidence in the geriatric population31 (with the highest risk of incident HIV and some STIs in older men who have sex with men32). These increased rates can be explained, at least in part, by:

• older men being less likely to use a condom during sexual activity

• promotion of viral entry in older women through a drier, thinner vaginal wall

• increased longevity of HIV-positive persons.31

Routine STI screening is not warranted in all older adults, but education and prevention strategies in sexually active seniors who are at greater risk of STIs are recommended. Particularly, clinicians should seek opportunities to discuss risk factors and safe sex practices (eg, using condoms, limiting number of sexual partners, practicing good hygiene, engaging in preventive care), and provide behavioral counseling where appropriate.31,33

Additional considerations in geriatric sexuality

Because psychiatric and systemic medical conditions can hinder sexual function, it is essential to identify and manage these conditions. Several neuropsychiatric disorders, including mood and neurocognitive disorders, can not only cause sexual dysfunction, but also can raise ethical dilemmas for clinicians, such as reduced decisional capacity in cognitively impaired patients to consent to sexual activity.1,34

In some patients, psychological, environmental, and pharmacological treatment options may help. A phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor for erectile dysfunction can be prescribed by the primary care physician, a psychiatrist, or another specialist, depending on the physician’s expertise and comfort level.

Sequencing of sexual dysfunction. Notably, there is a common paradox in mood disorders. Decreased sexual interest or performance may represent an aspect of anhedonia associated with depression, whereas sexual dysfunction could also result from medication use (particularly that of serotonergic antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine inhibitors), even as other depressive symptoms improve. Therefore, it is critical to analyze sequencing of sexual dysfunction—as part of the presenting mood symptoms or dysfunction induced by antidepressant treatment.

Geriatric sexuality in the digital age. Because older adults represent a rapidly growing segment of digital device users,35 Internet use is likely to play a role in the future of sexuality and “digital intimacy,” in that older adults can engage in online sexual activities. The Internet also can be a tool to access medical education.

Related Resources

• Burghardt KJ, Gardner KN. Sildenafil for SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(4):29-32,A.

• Maciel M, Laganà L. Older women’s sexual desire problems: biopsychosocial factors impacting them and barriers to their clinical assessment [published online January 5, 2014]. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:107217. doi: 10.1155/2014/107217.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban Mirtazapine • Remeron

Carbamazepine • Tegretol Oxcarbazepine • Trileptal

Clonidine • Catapres Phenobarbital • Luminal

Donepezil • Aricept Phenytoin • Dilantin

Escitalopram • Lexapro Pregabalin • Lyrica

Gabapentin • Neurontin Ramipril • Altace

Lamotrigine • Lamictal Rivastigmine • Exelon

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid Trazodone • Desyrel

Memantine • Namenda Valproic acid • Depakote

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Jagus CE, Benbow SM. Sexuality in older men with mental health problems. Sex Relation Ther. 2002;17(3):271-279.

2. Hillman JL. Clinical perspectives on elderly sexuality. New York, NY: Springer; 2000.

3. DeLamater JD, Sill M. Sexual desire in later life. J Sex Res. 2005;42(2):138-149.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

5. Laufer LR, Gambone JC. Climacteric: menopause and peri-and postmenopause. In: Hacker NF, Gambone JC, Hobel CJ. Hacker and Moore’s essentials of obstetrics and gynecology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2010:379-385.

6. Wilson MM. Menopause. Clin Geriatr Med. 2003;19(3): 483-506.

7. Reid R, Abramson BL, Blake J, et al. Managing menopause. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2014;36(9):830-838.

8. Horstman AM, Dillon EL, Urban RJ, et al. The role of androgens and estrogens on healthy aging and longevity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(11):1140-1152.

9. Wu FC, Tajar A, Pye SR, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis disruptions in older men are differentially linked to age and modifiable risk factors: the European Male Aging Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(7):2737-2745.

10. Basaria S. Reproductive aging in men. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2013;42(2):255-270.

11. Wu FC, Tajar A, Beynon JM, et al. Identification of late-onset hypogonadism in middle-aged and elderly men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(2):123-135.

12. Araujo AB, Esche GR, Kupelian V, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic androgen deficiency in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(11):4241-4247.

13. Lochlainn MN, Kenny RA. Sexual activity and aging. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(8):565-572.

14. McMahon CG. Erectile dysfunction. Intern Med J. 2014;44(1):18-26.

15. Avis NE, Brockwell S, Randolph JF Jr, et al. Longitudinal changes in sexual functioning as women transition through menopause: results from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Menopause. 2009;16(3):442-452.

16. Perelman M, Shabsigh R, Seftel A, et al. Attitudes of men with erectile dysfunction: a cross-national survey. J Sex Med. 2005;2(3):397-406.

17. Corona G, Rastrelli G, Maseroli E, et al. Sexual function of the ageing male. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;27(4):581-601.

18. Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, et al. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(8):762-774.

19. Lonnèe-Hoffmann RA, Dennerstein L, Lehert P, et al. Sexual function in the late postmenopause: a decade of follow-up in a population-based cohort of Australian women. J Sex Med. 2014;11(8):2029-2038.

20. Wang V, Depp CA, Ceglowski J, et al. Sexual health and function in later life: a population-based study of 606 older adults with a partner. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23(3):227-233.

21. Garrett D. Psychosocial barriers to sexual intimacy for older people. Br J Nurs. 2014;23(6):327-331.

22. DeLamater J, Karraker A. Sexual functioning in older adults. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11(1):6-11.

23. DeLamater J. Sexual expression in later life: a review and synthesis. J Sex Res. 2012;49(2-3):125-141.

24. Inelmen EM, Sergi G, Girardi A, et al. The importance of sexual health in the elderly: breaking down barriers and taboos. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2012;24(suppl 3):31-34.

25. Choi KB, Jang SH, Lee MY, et al. Sexual life and self-esteem in married elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;53(1):e17-e20.

26. Davison SL, Bell RJ, LaChina M, et al. The relationship between self-reported sexual satisfaction and general well-being in women. J Sex Med. 2009;6(10):2690-2697.

27. Morley JE, Tariq SH. Sexuality and disease. Clin Geriatr Med. 2003;19(3):563-573.

28. Bouman WP, Arcelus J. Are psychiatrists guilty of “ageism” when it comes to taking a sexual history? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16(1):27-31.

29. La Torre A, Giupponi G, Duffy DM, et al. Sexual dysfunction related to psychotropic drugs: a critical review. Part III: mood stabilizers and anxiolytic drugs. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2014;47(1):1-6.

30. Tucker I. Management of inappropriate sexual behaviors in dementia: a literature review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010; 22(5):683-692.

31. Imparato T, Sanders D. STD prevalence demands clinical awareness. Aging Well. 2012;5(1):14.

32. Poynten IM, Grulich AE, Templeton DJ. Sexually transmitted infections in older populations. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2013;26(1):80-85.

33. Talashek ML, Tichy AM, Epping H. Sexually transmitted diseases in the elderly—issues and recommendations. J Gerontol Nurs. 1990;16(4):33-40.

34. Benbow SM, Jagus CE. Sexuality in older women with mental health problems. Sex Relation Ther. 2002;17(3):261-270.

35. Veenhof B, Timusk P. Online activities of Canadian boomers and seniors. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/ 11-008-x/2009002/article/10910-eng.htm#tphp. Accessed March 26, 2015.

1. Jagus CE, Benbow SM. Sexuality in older men with mental health problems. Sex Relation Ther. 2002;17(3):271-279.

2. Hillman JL. Clinical perspectives on elderly sexuality. New York, NY: Springer; 2000.

3. DeLamater JD, Sill M. Sexual desire in later life. J Sex Res. 2005;42(2):138-149.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

5. Laufer LR, Gambone JC. Climacteric: menopause and peri-and postmenopause. In: Hacker NF, Gambone JC, Hobel CJ. Hacker and Moore’s essentials of obstetrics and gynecology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2010:379-385.

6. Wilson MM. Menopause. Clin Geriatr Med. 2003;19(3): 483-506.

7. Reid R, Abramson BL, Blake J, et al. Managing menopause. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2014;36(9):830-838.

8. Horstman AM, Dillon EL, Urban RJ, et al. The role of androgens and estrogens on healthy aging and longevity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(11):1140-1152.

9. Wu FC, Tajar A, Pye SR, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis disruptions in older men are differentially linked to age and modifiable risk factors: the European Male Aging Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(7):2737-2745.

10. Basaria S. Reproductive aging in men. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2013;42(2):255-270.

11. Wu FC, Tajar A, Beynon JM, et al. Identification of late-onset hypogonadism in middle-aged and elderly men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(2):123-135.

12. Araujo AB, Esche GR, Kupelian V, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic androgen deficiency in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(11):4241-4247.

13. Lochlainn MN, Kenny RA. Sexual activity and aging. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(8):565-572.

14. McMahon CG. Erectile dysfunction. Intern Med J. 2014;44(1):18-26.

15. Avis NE, Brockwell S, Randolph JF Jr, et al. Longitudinal changes in sexual functioning as women transition through menopause: results from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Menopause. 2009;16(3):442-452.

16. Perelman M, Shabsigh R, Seftel A, et al. Attitudes of men with erectile dysfunction: a cross-national survey. J Sex Med. 2005;2(3):397-406.

17. Corona G, Rastrelli G, Maseroli E, et al. Sexual function of the ageing male. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;27(4):581-601.

18. Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, et al. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(8):762-774.

19. Lonnèe-Hoffmann RA, Dennerstein L, Lehert P, et al. Sexual function in the late postmenopause: a decade of follow-up in a population-based cohort of Australian women. J Sex Med. 2014;11(8):2029-2038.

20. Wang V, Depp CA, Ceglowski J, et al. Sexual health and function in later life: a population-based study of 606 older adults with a partner. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23(3):227-233.

21. Garrett D. Psychosocial barriers to sexual intimacy for older people. Br J Nurs. 2014;23(6):327-331.

22. DeLamater J, Karraker A. Sexual functioning in older adults. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11(1):6-11.

23. DeLamater J. Sexual expression in later life: a review and synthesis. J Sex Res. 2012;49(2-3):125-141.

24. Inelmen EM, Sergi G, Girardi A, et al. The importance of sexual health in the elderly: breaking down barriers and taboos. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2012;24(suppl 3):31-34.

25. Choi KB, Jang SH, Lee MY, et al. Sexual life and self-esteem in married elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;53(1):e17-e20.

26. Davison SL, Bell RJ, LaChina M, et al. The relationship between self-reported sexual satisfaction and general well-being in women. J Sex Med. 2009;6(10):2690-2697.

27. Morley JE, Tariq SH. Sexuality and disease. Clin Geriatr Med. 2003;19(3):563-573.

28. Bouman WP, Arcelus J. Are psychiatrists guilty of “ageism” when it comes to taking a sexual history? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16(1):27-31.

29. La Torre A, Giupponi G, Duffy DM, et al. Sexual dysfunction related to psychotropic drugs: a critical review. Part III: mood stabilizers and anxiolytic drugs. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2014;47(1):1-6.

30. Tucker I. Management of inappropriate sexual behaviors in dementia: a literature review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010; 22(5):683-692.

31. Imparato T, Sanders D. STD prevalence demands clinical awareness. Aging Well. 2012;5(1):14.

32. Poynten IM, Grulich AE, Templeton DJ. Sexually transmitted infections in older populations. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2013;26(1):80-85.

33. Talashek ML, Tichy AM, Epping H. Sexually transmitted diseases in the elderly—issues and recommendations. J Gerontol Nurs. 1990;16(4):33-40.

34. Benbow SM, Jagus CE. Sexuality in older women with mental health problems. Sex Relation Ther. 2002;17(3):261-270.

35. Veenhof B, Timusk P. Online activities of Canadian boomers and seniors. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/ 11-008-x/2009002/article/10910-eng.htm#tphp. Accessed March 26, 2015.