User login

Reply to “Increasing Inpatient Consultation: Hospitalist Perceptions and Objective Findings. In Reference to: ‘Hospitalist Perspective of Interactions with Medicine Subspecialty Consult Services’”

The finding by Kachman et al. that consultations have decreased at their institution is an interesting and important observation.1 In contrast, our study found that more than a third of hospitalists reported an increase in consultation requests.2 There may be several explanations for this discrepancy. First, as Kachman et al. suggest, there may be differences between hospitalist perception and actual consultation use. Second, a significant variability in consultation may exist between hospitals. Although our study examined four institutions, we were unable to examine the variability between them, which requires further study. Third, there may be considerable variability between individual hospitalist practices, which is consistent with the findings reported by Kachman et al. Finally, the fact that our study examined only nonteaching services may be another explanation as Kachman et al. found that hospitalists on nonteaching services ordered more consultations than those on teaching services. These findings are consistent with a recent study conducted by Perez et al., who found that hospitalists on teaching services utilized fewer consultations and had lower direct care costs and shorter lengths of stay compared with those on nonteaching services.3 This finding raises the question of whether consultations impact care costs and lengths of stay, a topic that should be explored in future studies.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

1. Kachman M, Carter K, Martin S. Increasing inpatient consultation: hospitalist perceptions and objective findings. In Reference to: “Hospitalist perspective of interactions with medicine subspecialty consult services”. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):802. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2992.

2. Adams TN, Bonsall J, Hunt D, et al. Hospitalist perspective of interactions with medicine subspecialty consult services. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(5):318-323. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2882. PubMed

3. Perez JA Jr, Awar M, Nezamabadi A, et al. Comparison of direct patient care costs and quality outcomes of the teaching and nonteaching hospitalist services at a large academic medical center. Acad Med. 2018;93(3):491-497. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002026. PubMed

The finding by Kachman et al. that consultations have decreased at their institution is an interesting and important observation.1 In contrast, our study found that more than a third of hospitalists reported an increase in consultation requests.2 There may be several explanations for this discrepancy. First, as Kachman et al. suggest, there may be differences between hospitalist perception and actual consultation use. Second, a significant variability in consultation may exist between hospitals. Although our study examined four institutions, we were unable to examine the variability between them, which requires further study. Third, there may be considerable variability between individual hospitalist practices, which is consistent with the findings reported by Kachman et al. Finally, the fact that our study examined only nonteaching services may be another explanation as Kachman et al. found that hospitalists on nonteaching services ordered more consultations than those on teaching services. These findings are consistent with a recent study conducted by Perez et al., who found that hospitalists on teaching services utilized fewer consultations and had lower direct care costs and shorter lengths of stay compared with those on nonteaching services.3 This finding raises the question of whether consultations impact care costs and lengths of stay, a topic that should be explored in future studies.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

The finding by Kachman et al. that consultations have decreased at their institution is an interesting and important observation.1 In contrast, our study found that more than a third of hospitalists reported an increase in consultation requests.2 There may be several explanations for this discrepancy. First, as Kachman et al. suggest, there may be differences between hospitalist perception and actual consultation use. Second, a significant variability in consultation may exist between hospitals. Although our study examined four institutions, we were unable to examine the variability between them, which requires further study. Third, there may be considerable variability between individual hospitalist practices, which is consistent with the findings reported by Kachman et al. Finally, the fact that our study examined only nonteaching services may be another explanation as Kachman et al. found that hospitalists on nonteaching services ordered more consultations than those on teaching services. These findings are consistent with a recent study conducted by Perez et al., who found that hospitalists on teaching services utilized fewer consultations and had lower direct care costs and shorter lengths of stay compared with those on nonteaching services.3 This finding raises the question of whether consultations impact care costs and lengths of stay, a topic that should be explored in future studies.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

1. Kachman M, Carter K, Martin S. Increasing inpatient consultation: hospitalist perceptions and objective findings. In Reference to: “Hospitalist perspective of interactions with medicine subspecialty consult services”. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):802. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2992.

2. Adams TN, Bonsall J, Hunt D, et al. Hospitalist perspective of interactions with medicine subspecialty consult services. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(5):318-323. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2882. PubMed

3. Perez JA Jr, Awar M, Nezamabadi A, et al. Comparison of direct patient care costs and quality outcomes of the teaching and nonteaching hospitalist services at a large academic medical center. Acad Med. 2018;93(3):491-497. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002026. PubMed

1. Kachman M, Carter K, Martin S. Increasing inpatient consultation: hospitalist perceptions and objective findings. In Reference to: “Hospitalist perspective of interactions with medicine subspecialty consult services”. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):802. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2992.

2. Adams TN, Bonsall J, Hunt D, et al. Hospitalist perspective of interactions with medicine subspecialty consult services. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(5):318-323. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2882. PubMed

3. Perez JA Jr, Awar M, Nezamabadi A, et al. Comparison of direct patient care costs and quality outcomes of the teaching and nonteaching hospitalist services at a large academic medical center. Acad Med. 2018;93(3):491-497. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002026. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Hospitalist Perspective of Interactions with Medicine Subspecialty Consult Services

Hospitalist physicians care for an increasing proportion of general medicine inpatients and request a significant share of all subspecialty consultations.1 Subspecialty consultation in inpatient care is increasing,2,3 and effective hospitalist–consulting service interactions may affect team communication, patient care, and hospitalist learning. Therefore, enhancing hospitalist–consulting service interactions may have a broad-reaching, positive impact. Researchers in previous studies have explored resident–fellow consult interactions in the inpatient and emergency department settings as well as attending-to-attending consultation in the outpatient setting.4-7 However, to our knowledge, hospitalist–consulting team interactions have not been previously described. In academic medical centers, hospitalists are attending physicians who interact with both fellows (supervised by attending consultants) and directly with subspecialty attendings. Therefore, the exploration of the hospitalist–consultant interaction requires an evaluation of hospitalist–fellow and hospitalist–subspecialty attending interactions. The hospitalist–fellow interaction in particular is unique because it represents an unusual dynamic, in which an attending physician is primarily communicating with a trainee when requesting assistance with patient care.8 In order to explore hospitalist–consultant interactions (herein, the term “consultant” includes both fellow and attending consultants), we conducted a survey study in which we examine hospitalist practices and attitudes regarding consultation, with a specific focus on hospitalist consultation with internal medicine subspecialty consult services. In addition, we compared fellow–hospitalist and attending–hospitalist interactions and explored barriers to and facilitating factors of an effective hospitalist–consultant relationship.

METHODS

Survey Development

The survey instrument was developed by the authors based on findings of prior studies in which researchers examined consultation.2-6,9-16 The survey contained 31 questions (supplementary Appendix A) and evaluated 4 domains of the use of medical subspecialty consultation in direct patient care: (1) current consultation practices, (2) preferences regarding consultants, (3) barriers to and facilitating factors of effective consultation (both with respect to hospitalist learning and patient care), and (4) a comparison between hospitalist–fellow and hospitalist–subspecialty attending interactions. An evaluation of current consultation practices included a focus on communication methods (eg, in person, over the phone, through paging, or notes) because these have been found to be important during consultation.5,6,9,15,16 In order to explore hospitalist preferences regarding consult interactions and investigate perceptions of barriers to and facilitating factors of effective consultation, questions were developed based on previous literature, including our qualitative work examining resident–fellow interactions during consultation.4-6,9,12 We compared hospitalist consultation experiences among attending and fellow consultants because the interaction in which an attending hospitalist physician is primarily communicating with a trainee may differ from a consultation between a hospitalist attending and a subspecialty attending.8 Participants were asked to exclude their experiences when working on teaching services, during which students or housestaff often interact with consultants. The survey was cognitively tested with both hospitalist and non-hospitalist attending physicians not participating in the study and was revised by the authors using an iterative approach.

Study Participants

Hospitalist attending physicians at University of Texas Southwestern (UTSW) Medical Center, Emory University School of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), and the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) were eligible to participate in the study. Consult team structures at each institution were composed of either a subspecialist-attending-only or a fellow-and-subspecialty-attending team. Fellows at all institutions are supervised by a subspecialty attending when performing consultations. Respondents who self-identified as nurse practitioners or physician assistants were excluded from the analysis. Hospitalists employed by the Veterans Affairs hospital system were also excluded. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of UTSW, Emory, MUSC, and MGH.

The survey was anonymous and administered to all hospitalists at participating institutions via a web-based survey tool (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). Participants were eligible to enter a raffle for a $500 gift card, and completion of the survey was not required for entry into the raffle.

Statistics

Results were summarized using the mean with standard deviation for continuous variables and the frequency with percentage for categorical variables after excluding missing values. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A 2-sided P value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Current Consultation Practices

Current consultation practices and descriptions of hospitalist–consultant communication are shown in Table 2. Forty percent of respondents requested 0-1 consults per day, while 51.7% requested 2-3 per day. The most common reasons for requesting a consultation were assistance with treatment (48.5%), assistance with diagnosis (25.7%), and request for a procedure (21.8%). When asked whether the frequency of consultation is changing, slightly more hospitalists felt that their personal use of consultation was increasing as compared to those who felt that it was decreasing (38.5% vs 30.3%, respectively).

Hospitalist Preferences

Eighty-six percent of respondents agreed that consultants should be required to communicate their recommendations either in person or over the phone. Eighty-three percent of hospitalists agreed that they would like to receive more teaching from the consulting services, and 74.0% agreed that consultants should attempt to teach hospitalists during consult interactions regardless of whether the hospitalist initiates the teaching–learning interaction.

Barriers to and Facilitating Factors of Effective Consultation

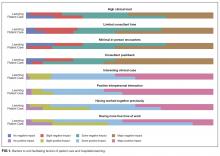

Participants reported that multiple factors affected patient care and their own learning during inpatient consultation (Figure 1). Consultant pushback, high hospitalist clinical workload, a perception that consultants had limited time, and minimal in-person interactions were all seen as factors that negatively affected the consult interaction. These generally affected both learning and patient care. Conversely, working on an interesting clinical case, more hospitalist free time, positive interaction with the consultant, and having previously worked with the consultant positively affected both learning and patient care (Figure 1).

Fellow Versus Attending Interactions

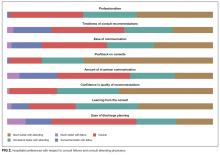

Respondents indicated that interacting directly with the consult attending was superior to hospitalist–fellow interactions in all aspects of care but particularly with respect to pushback, confidence in recommendations, professionalism, and hospitalist learning (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe hospitalist attending practices, attitudes, and perceptions of internal medicine subspecialty consultation. Our findings, which focus on the interaction between hospitalists and internal medicine subspecialty attendings and fellows, outline the hospitalist perspective on consultant interactions and identify a number of factors that are amenable to intervention. We found that hospitalists perceive the consult interaction to be important for patient care and a valuable opportunity for their own learning. In-person communication was seen as an important component of effective consultation but was reported to occur in a minority of consultations. We demonstrate that hospitalist–subspecialty attending consult interactions are perceived more positively than hospitalist–fellow interactions. Finally, we describe barriers and facilitating factors that may inform future interventions targeting this important interaction.

Effective communication between consultants and the primary team is critical for both patient care and teaching interactions.4-7 Pushback on consultation was reported to be the most significant barrier to hospitalist learning and had a major impact on patient care. Because hospitalists are attending physicians, we hypothesized that they may perceive pushback from fellows less frequently than residents.4 However, in our study, hospitalists reported pushback to be relatively frequent in their daily practice. Moreover, hospitalists reported a strong preference for in-person interactions with consultants, but our study demonstrated that such interactions are relatively infrequent. Researchers in studies of resident–fellow consult interactions have noted similar findings, suggesting that hospitalists and internal medicine residents face similar challenges during consultation.4-6 Hospitalists reported that positive interpersonal interactions and personal familiarity with the consultant positively affected the consult interaction. Most importantly, these effects were perceived to affect both hospitalist learning and patient care, suggesting the importance of interpersonal interactions in consultative medicine.

In an era of increasing clinical workload, the consult interaction represents an important workplace-based learning opportunity.4 Centered on a consult question, the hospitalist–consultant interaction embodies a teachable moment and can be an efficient opportunity to learn because both parties are familiar with the patient. Indeed, survey respondents reported that they frequently learned from consultation, and there was a strong preference for more teaching from consultants in this setting. However, the hospitalist–fellow consult interaction is unique because attending hospitalists are frequently communicating with fellow trainees, which could limit fellows’ confidence in their role as teachers and hospitalists’ perception of their role as learners. Our study identifies a number of barriers and facilitating factors (including communication, pushback, familiarity, and clinical workload) that affect the hospitalist–consultant teaching interaction and may be amenable to intervention.

Hospitalists expressed a consistent preference for interacting with attending subspecialists compared to clinical fellows during consultation. Preference for interaction with attendings was strongest in the areas of pushback, confidence in recommendations, professionalism, and learning from consultation. Some of the factors that relate to consult service structure and fellow experience, such as timeliness of consultation and confidence in recommendations, may not be amenable to intervention. For instance, fellows must first see and then staff the consult with their attending prior to leaving formal recommendations, which makes their communication less timely than that of attending physicians, when they are the primary consultant. However, aspects of the hospitalist–consultant interaction (such as professionalism, ease of communication, and pushback) should not be affected by the difference in experience between fellows and attending physicians. The reasons for such perceptions deserve further exploration; however, differences in incentive structures, workload, and communication skills between fellows and attending consultants may be potential explanations.

Our findings suggest that interventions aimed at enhancing hospitalist–consultant interactions focus on enhancing direct communication and teaching while limiting the perception of pushback. A number of interventions that are primarily focused on instituting a systematic approach to requesting consultation have shown an improvement in resident and medical student consult communication17,18 as well as resident–fellow teaching interactions.9 However, it is not clear whether these interventions would be effective given that hospitalists have more experience communicating with consultants than trainees. Given the unique nature of the hospitalist–consultant interaction, multiple barriers may need to be addressed in order to have a significant impact. Efforts to increase direct communication, such as a mechanism for hospitalists to make and request in-person or direct verbal communication about a particular consultation during the consult request, can help consultants prioritize direct communication with hospitalists for specific patients. Familiarizing fellows with hospitalist workflow and the locations of hospitalist workrooms also may promote in-person communication. Fellowship training can focus on enhancing fellow teaching and communication skills,19-22 particularly as they relate to hospitalists. Fellows in particular may benefit because the hospitalist–fellow teaching interaction may be bidirectional, with hospitalists having expertise in systems practice and quality efforts that can inform fellows’ practice. Furthermore, interacting with hospitalists is an opportunity for fellows to practice professional interactions, which will be critical to their careers. Increasing familiarity between fellows and hospitalists through joint events may also serve to enhance the interaction. Finally, enabling hospitalists to provide feedback to fellows stands to benefit both parties because multisource feedback is an important tool in assessing trainee competence and improving performance.23 However, we should note that because our study focused on hospitalist perceptions, an exploration of subspecialty fellows’ and attendings’ perceptions of the hospitalist–consultant interaction would provide additional, important data for shaping interventions.

Strengths of our study include the inclusion of multiple study sites, which may increase generalizability; however, our study has several limitations. The incomplete response rate reduces both generalizability and statistical power and may have created selection or nonresponder bias. However, low response rates occur commonly when surveying medical professionals, and our results are consistent with many prior hospitalist survey studies.24-26 Further, we conducted our study at a single time point; therefore, we could not evaluate the effect of fellow experience on hospitalist perceptions. However, we conducted our study in the second half of the academic year, when fellows had already gained considerable experience in the consultation setting. We did not capture participants’ institutional affiliations; therefore, a subgroup analysis by institution could not be performed. Additionally, our study reflects hospitalist perception rather than objectively measured communication practices between hospitalists and consultants, and it does not include the perspective of subspecialists. The specific needs of nurse practitioners and physicians’ assistants, who were excluded from this study, should also be evaluated in future research. Lastly, this is a hypothesis-generating study and should be replicated in a national cohort.

CONCLUSION

The hospitalists represented in our sample population perceived the consult interaction to be important for patient care and a valuable opportunity for their own learning. Participants expressed that they would like to increase direct communication with consultants and enhance consultant–hospitalist teaching interactions. Multiple barriers to effective hospitalist–consultant interactions (including communication, pushback, and hospitalist–consultant familiarity) are amenable to intervention.

Disclosure

The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

1. Kravolec PD, Miller JA, Wellikson L, Huddleston JM. The status of hospital medicine groups in the United States. J Hosp Med.2006;1(2):75-80. PubMed

2. Cai Q, Bruno CJ, Hagedorn CH, Desbiens NA. Temporal trends over ten years in formal inpatient gastroenterology consultations at an inner-city hospital. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36(1):34-38. PubMed

3. Ta K, Gardner GC. Evaluation of the activity of an academic rheumatology consult service over 10 years: using data to shape curriculum. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(3):563-566. PubMed

4. Miloslavsky EM, McSparron JI, Richards JB, Puig A, Sullivan AM. Teaching during consultation: factors affecting the resident-fellow teaching interaction. Med Educ. 2015;49(7):717-730. PubMed

5. Chan T, Sabir K, Sanhan S, Sherbino J. Understanding the impact of residents’ interpersonal relationships during emergency department referrals and consultations. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(4):576-581. PubMed

6. Chan T, Bakewell F, Orlich D, Sherbino J. Conflict prevention, conflict mitigation, and manifestations of conflict during emergency department consultations. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(3):308-313. PubMed

7. Goldman L, Lee T, Rudd P. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143(9):1753-1755. PubMed

8. Adams T. Barriers to hospitalist fellow interactions. Med Educ. 2016;50(3):370. PubMed

9. Gupta S, Alladina J, Heaton K, Miloslavsky E. A randomized trial of an intervention to improve resident-fellow teaching interaction on the wards. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):276. PubMed

10. Day LW, Cello JP, Madden E, Segal M. Prospective assessment of inpatient gastrointestinal consultation requests in an academic teaching hospital. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(3):484-489. PubMed

11. Kessler C, Kutka BM, Badillo C. Consultation in the emergency department: a qualitative analysis and review. J Emerg Med. 2012;42(6):704-711. PubMed

12. Salerno SM, Hurst FP, Halvorson S, Mercado DL. Principles of effective consultation: an update for the 21st-century consultant. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(3):271-275. PubMed

13. Muzin LJ. Understanding the process of medical referral: part 1: critique of the literature. Can Fam Physician. 1991;37:2155-2161. PubMed

14. Muzin LJ. Understanding the process of medical referral: part 5: communication. Can Fam Physician. 1992;38:301-307. PubMed

15. Wadhwa A, Lingard L. A qualitative study examining tensions in interdoctor telephone consultations. Med Educ. 2006;40(8):759-767. PubMed

16. Grant IN, Dixon AS. “Thank you for seeing this patient”: studying the quality of communication between physicians. Can Fam Physician. 1987;33:605-611. PubMed

17. Kessler CS, Afshar Y, Sardar G, Yudkowsky R, Ankel F, Schwartz A. A prospective, randomized, controlled study demonstrating a novel, effective model of transfer of care between physicians: the 5 Cs of consultation. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(8):968-974. PubMed

18. Podolsky A, Stern DTP. The courteous consult: a CONSULT card and training to improve resident consults. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(1):113-117. PubMed

19. Tofil NM, Peterson DT, Harrington KF, et al. A novel iterative-learner simulation model: fellows as teachers. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2014;6(1):127-132. PubMed

20. Kempainen RR, Hallstrand TS, Culver BH, Tonelli MR. Fellows as teachers: the teacher-assistant experience during pulmonary subspecialty training. Chest. 2005;128(1):401-406. PubMed

21. Backes CH, Reber KM, Trittmann JK, et al. Fellows as teachers: a model to enhance pediatric resident education. Med. Educ. Online. 2011;16:7205. PubMed

22. Miloslavsky EM, Degnan K, McNeill J, McSparron JI. Use of Fellow as Clinical Teacher (FACT) Curriculum for Teaching During Consultation: Effect on Subspecialty Fellow Teaching Skills. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(3):345-350 PubMed

23. Donnon T, Al Ansari A, Al Alawi S, Violato C. The reliability, validity, and feasibility of multisource feedback physician assessment: a systematic review. Acad. Med. 2014;89(3):511-516. PubMed

24. Monash B, Najafi N, Mourad M, et al. Standardized attending rounds to improve the patient experience: A pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(3):143-149. PubMed

25. Allen-Dicker J, Auerbach A, Herzig SJ. Perceived safety and value of inpatient “very important person” services. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(3):177-179. PubMed

26. Do D, Munchhof AM, Terry C, Emmett T, Kara A. Research and publication trends in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):148-154. PubMed

Hospitalist physicians care for an increasing proportion of general medicine inpatients and request a significant share of all subspecialty consultations.1 Subspecialty consultation in inpatient care is increasing,2,3 and effective hospitalist–consulting service interactions may affect team communication, patient care, and hospitalist learning. Therefore, enhancing hospitalist–consulting service interactions may have a broad-reaching, positive impact. Researchers in previous studies have explored resident–fellow consult interactions in the inpatient and emergency department settings as well as attending-to-attending consultation in the outpatient setting.4-7 However, to our knowledge, hospitalist–consulting team interactions have not been previously described. In academic medical centers, hospitalists are attending physicians who interact with both fellows (supervised by attending consultants) and directly with subspecialty attendings. Therefore, the exploration of the hospitalist–consultant interaction requires an evaluation of hospitalist–fellow and hospitalist–subspecialty attending interactions. The hospitalist–fellow interaction in particular is unique because it represents an unusual dynamic, in which an attending physician is primarily communicating with a trainee when requesting assistance with patient care.8 In order to explore hospitalist–consultant interactions (herein, the term “consultant” includes both fellow and attending consultants), we conducted a survey study in which we examine hospitalist practices and attitudes regarding consultation, with a specific focus on hospitalist consultation with internal medicine subspecialty consult services. In addition, we compared fellow–hospitalist and attending–hospitalist interactions and explored barriers to and facilitating factors of an effective hospitalist–consultant relationship.

METHODS

Survey Development

The survey instrument was developed by the authors based on findings of prior studies in which researchers examined consultation.2-6,9-16 The survey contained 31 questions (supplementary Appendix A) and evaluated 4 domains of the use of medical subspecialty consultation in direct patient care: (1) current consultation practices, (2) preferences regarding consultants, (3) barriers to and facilitating factors of effective consultation (both with respect to hospitalist learning and patient care), and (4) a comparison between hospitalist–fellow and hospitalist–subspecialty attending interactions. An evaluation of current consultation practices included a focus on communication methods (eg, in person, over the phone, through paging, or notes) because these have been found to be important during consultation.5,6,9,15,16 In order to explore hospitalist preferences regarding consult interactions and investigate perceptions of barriers to and facilitating factors of effective consultation, questions were developed based on previous literature, including our qualitative work examining resident–fellow interactions during consultation.4-6,9,12 We compared hospitalist consultation experiences among attending and fellow consultants because the interaction in which an attending hospitalist physician is primarily communicating with a trainee may differ from a consultation between a hospitalist attending and a subspecialty attending.8 Participants were asked to exclude their experiences when working on teaching services, during which students or housestaff often interact with consultants. The survey was cognitively tested with both hospitalist and non-hospitalist attending physicians not participating in the study and was revised by the authors using an iterative approach.

Study Participants

Hospitalist attending physicians at University of Texas Southwestern (UTSW) Medical Center, Emory University School of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), and the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) were eligible to participate in the study. Consult team structures at each institution were composed of either a subspecialist-attending-only or a fellow-and-subspecialty-attending team. Fellows at all institutions are supervised by a subspecialty attending when performing consultations. Respondents who self-identified as nurse practitioners or physician assistants were excluded from the analysis. Hospitalists employed by the Veterans Affairs hospital system were also excluded. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of UTSW, Emory, MUSC, and MGH.

The survey was anonymous and administered to all hospitalists at participating institutions via a web-based survey tool (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). Participants were eligible to enter a raffle for a $500 gift card, and completion of the survey was not required for entry into the raffle.

Statistics

Results were summarized using the mean with standard deviation for continuous variables and the frequency with percentage for categorical variables after excluding missing values. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A 2-sided P value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Current Consultation Practices

Current consultation practices and descriptions of hospitalist–consultant communication are shown in Table 2. Forty percent of respondents requested 0-1 consults per day, while 51.7% requested 2-3 per day. The most common reasons for requesting a consultation were assistance with treatment (48.5%), assistance with diagnosis (25.7%), and request for a procedure (21.8%). When asked whether the frequency of consultation is changing, slightly more hospitalists felt that their personal use of consultation was increasing as compared to those who felt that it was decreasing (38.5% vs 30.3%, respectively).

Hospitalist Preferences

Eighty-six percent of respondents agreed that consultants should be required to communicate their recommendations either in person or over the phone. Eighty-three percent of hospitalists agreed that they would like to receive more teaching from the consulting services, and 74.0% agreed that consultants should attempt to teach hospitalists during consult interactions regardless of whether the hospitalist initiates the teaching–learning interaction.

Barriers to and Facilitating Factors of Effective Consultation

Participants reported that multiple factors affected patient care and their own learning during inpatient consultation (Figure 1). Consultant pushback, high hospitalist clinical workload, a perception that consultants had limited time, and minimal in-person interactions were all seen as factors that negatively affected the consult interaction. These generally affected both learning and patient care. Conversely, working on an interesting clinical case, more hospitalist free time, positive interaction with the consultant, and having previously worked with the consultant positively affected both learning and patient care (Figure 1).

Fellow Versus Attending Interactions

Respondents indicated that interacting directly with the consult attending was superior to hospitalist–fellow interactions in all aspects of care but particularly with respect to pushback, confidence in recommendations, professionalism, and hospitalist learning (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe hospitalist attending practices, attitudes, and perceptions of internal medicine subspecialty consultation. Our findings, which focus on the interaction between hospitalists and internal medicine subspecialty attendings and fellows, outline the hospitalist perspective on consultant interactions and identify a number of factors that are amenable to intervention. We found that hospitalists perceive the consult interaction to be important for patient care and a valuable opportunity for their own learning. In-person communication was seen as an important component of effective consultation but was reported to occur in a minority of consultations. We demonstrate that hospitalist–subspecialty attending consult interactions are perceived more positively than hospitalist–fellow interactions. Finally, we describe barriers and facilitating factors that may inform future interventions targeting this important interaction.

Effective communication between consultants and the primary team is critical for both patient care and teaching interactions.4-7 Pushback on consultation was reported to be the most significant barrier to hospitalist learning and had a major impact on patient care. Because hospitalists are attending physicians, we hypothesized that they may perceive pushback from fellows less frequently than residents.4 However, in our study, hospitalists reported pushback to be relatively frequent in their daily practice. Moreover, hospitalists reported a strong preference for in-person interactions with consultants, but our study demonstrated that such interactions are relatively infrequent. Researchers in studies of resident–fellow consult interactions have noted similar findings, suggesting that hospitalists and internal medicine residents face similar challenges during consultation.4-6 Hospitalists reported that positive interpersonal interactions and personal familiarity with the consultant positively affected the consult interaction. Most importantly, these effects were perceived to affect both hospitalist learning and patient care, suggesting the importance of interpersonal interactions in consultative medicine.

In an era of increasing clinical workload, the consult interaction represents an important workplace-based learning opportunity.4 Centered on a consult question, the hospitalist–consultant interaction embodies a teachable moment and can be an efficient opportunity to learn because both parties are familiar with the patient. Indeed, survey respondents reported that they frequently learned from consultation, and there was a strong preference for more teaching from consultants in this setting. However, the hospitalist–fellow consult interaction is unique because attending hospitalists are frequently communicating with fellow trainees, which could limit fellows’ confidence in their role as teachers and hospitalists’ perception of their role as learners. Our study identifies a number of barriers and facilitating factors (including communication, pushback, familiarity, and clinical workload) that affect the hospitalist–consultant teaching interaction and may be amenable to intervention.

Hospitalists expressed a consistent preference for interacting with attending subspecialists compared to clinical fellows during consultation. Preference for interaction with attendings was strongest in the areas of pushback, confidence in recommendations, professionalism, and learning from consultation. Some of the factors that relate to consult service structure and fellow experience, such as timeliness of consultation and confidence in recommendations, may not be amenable to intervention. For instance, fellows must first see and then staff the consult with their attending prior to leaving formal recommendations, which makes their communication less timely than that of attending physicians, when they are the primary consultant. However, aspects of the hospitalist–consultant interaction (such as professionalism, ease of communication, and pushback) should not be affected by the difference in experience between fellows and attending physicians. The reasons for such perceptions deserve further exploration; however, differences in incentive structures, workload, and communication skills between fellows and attending consultants may be potential explanations.

Our findings suggest that interventions aimed at enhancing hospitalist–consultant interactions focus on enhancing direct communication and teaching while limiting the perception of pushback. A number of interventions that are primarily focused on instituting a systematic approach to requesting consultation have shown an improvement in resident and medical student consult communication17,18 as well as resident–fellow teaching interactions.9 However, it is not clear whether these interventions would be effective given that hospitalists have more experience communicating with consultants than trainees. Given the unique nature of the hospitalist–consultant interaction, multiple barriers may need to be addressed in order to have a significant impact. Efforts to increase direct communication, such as a mechanism for hospitalists to make and request in-person or direct verbal communication about a particular consultation during the consult request, can help consultants prioritize direct communication with hospitalists for specific patients. Familiarizing fellows with hospitalist workflow and the locations of hospitalist workrooms also may promote in-person communication. Fellowship training can focus on enhancing fellow teaching and communication skills,19-22 particularly as they relate to hospitalists. Fellows in particular may benefit because the hospitalist–fellow teaching interaction may be bidirectional, with hospitalists having expertise in systems practice and quality efforts that can inform fellows’ practice. Furthermore, interacting with hospitalists is an opportunity for fellows to practice professional interactions, which will be critical to their careers. Increasing familiarity between fellows and hospitalists through joint events may also serve to enhance the interaction. Finally, enabling hospitalists to provide feedback to fellows stands to benefit both parties because multisource feedback is an important tool in assessing trainee competence and improving performance.23 However, we should note that because our study focused on hospitalist perceptions, an exploration of subspecialty fellows’ and attendings’ perceptions of the hospitalist–consultant interaction would provide additional, important data for shaping interventions.

Strengths of our study include the inclusion of multiple study sites, which may increase generalizability; however, our study has several limitations. The incomplete response rate reduces both generalizability and statistical power and may have created selection or nonresponder bias. However, low response rates occur commonly when surveying medical professionals, and our results are consistent with many prior hospitalist survey studies.24-26 Further, we conducted our study at a single time point; therefore, we could not evaluate the effect of fellow experience on hospitalist perceptions. However, we conducted our study in the second half of the academic year, when fellows had already gained considerable experience in the consultation setting. We did not capture participants’ institutional affiliations; therefore, a subgroup analysis by institution could not be performed. Additionally, our study reflects hospitalist perception rather than objectively measured communication practices between hospitalists and consultants, and it does not include the perspective of subspecialists. The specific needs of nurse practitioners and physicians’ assistants, who were excluded from this study, should also be evaluated in future research. Lastly, this is a hypothesis-generating study and should be replicated in a national cohort.

CONCLUSION

The hospitalists represented in our sample population perceived the consult interaction to be important for patient care and a valuable opportunity for their own learning. Participants expressed that they would like to increase direct communication with consultants and enhance consultant–hospitalist teaching interactions. Multiple barriers to effective hospitalist–consultant interactions (including communication, pushback, and hospitalist–consultant familiarity) are amenable to intervention.

Disclosure

The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Hospitalist physicians care for an increasing proportion of general medicine inpatients and request a significant share of all subspecialty consultations.1 Subspecialty consultation in inpatient care is increasing,2,3 and effective hospitalist–consulting service interactions may affect team communication, patient care, and hospitalist learning. Therefore, enhancing hospitalist–consulting service interactions may have a broad-reaching, positive impact. Researchers in previous studies have explored resident–fellow consult interactions in the inpatient and emergency department settings as well as attending-to-attending consultation in the outpatient setting.4-7 However, to our knowledge, hospitalist–consulting team interactions have not been previously described. In academic medical centers, hospitalists are attending physicians who interact with both fellows (supervised by attending consultants) and directly with subspecialty attendings. Therefore, the exploration of the hospitalist–consultant interaction requires an evaluation of hospitalist–fellow and hospitalist–subspecialty attending interactions. The hospitalist–fellow interaction in particular is unique because it represents an unusual dynamic, in which an attending physician is primarily communicating with a trainee when requesting assistance with patient care.8 In order to explore hospitalist–consultant interactions (herein, the term “consultant” includes both fellow and attending consultants), we conducted a survey study in which we examine hospitalist practices and attitudes regarding consultation, with a specific focus on hospitalist consultation with internal medicine subspecialty consult services. In addition, we compared fellow–hospitalist and attending–hospitalist interactions and explored barriers to and facilitating factors of an effective hospitalist–consultant relationship.

METHODS

Survey Development

The survey instrument was developed by the authors based on findings of prior studies in which researchers examined consultation.2-6,9-16 The survey contained 31 questions (supplementary Appendix A) and evaluated 4 domains of the use of medical subspecialty consultation in direct patient care: (1) current consultation practices, (2) preferences regarding consultants, (3) barriers to and facilitating factors of effective consultation (both with respect to hospitalist learning and patient care), and (4) a comparison between hospitalist–fellow and hospitalist–subspecialty attending interactions. An evaluation of current consultation practices included a focus on communication methods (eg, in person, over the phone, through paging, or notes) because these have been found to be important during consultation.5,6,9,15,16 In order to explore hospitalist preferences regarding consult interactions and investigate perceptions of barriers to and facilitating factors of effective consultation, questions were developed based on previous literature, including our qualitative work examining resident–fellow interactions during consultation.4-6,9,12 We compared hospitalist consultation experiences among attending and fellow consultants because the interaction in which an attending hospitalist physician is primarily communicating with a trainee may differ from a consultation between a hospitalist attending and a subspecialty attending.8 Participants were asked to exclude their experiences when working on teaching services, during which students or housestaff often interact with consultants. The survey was cognitively tested with both hospitalist and non-hospitalist attending physicians not participating in the study and was revised by the authors using an iterative approach.

Study Participants

Hospitalist attending physicians at University of Texas Southwestern (UTSW) Medical Center, Emory University School of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), and the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) were eligible to participate in the study. Consult team structures at each institution were composed of either a subspecialist-attending-only or a fellow-and-subspecialty-attending team. Fellows at all institutions are supervised by a subspecialty attending when performing consultations. Respondents who self-identified as nurse practitioners or physician assistants were excluded from the analysis. Hospitalists employed by the Veterans Affairs hospital system were also excluded. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of UTSW, Emory, MUSC, and MGH.

The survey was anonymous and administered to all hospitalists at participating institutions via a web-based survey tool (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). Participants were eligible to enter a raffle for a $500 gift card, and completion of the survey was not required for entry into the raffle.

Statistics

Results were summarized using the mean with standard deviation for continuous variables and the frequency with percentage for categorical variables after excluding missing values. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A 2-sided P value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Current Consultation Practices

Current consultation practices and descriptions of hospitalist–consultant communication are shown in Table 2. Forty percent of respondents requested 0-1 consults per day, while 51.7% requested 2-3 per day. The most common reasons for requesting a consultation were assistance with treatment (48.5%), assistance with diagnosis (25.7%), and request for a procedure (21.8%). When asked whether the frequency of consultation is changing, slightly more hospitalists felt that their personal use of consultation was increasing as compared to those who felt that it was decreasing (38.5% vs 30.3%, respectively).

Hospitalist Preferences

Eighty-six percent of respondents agreed that consultants should be required to communicate their recommendations either in person or over the phone. Eighty-three percent of hospitalists agreed that they would like to receive more teaching from the consulting services, and 74.0% agreed that consultants should attempt to teach hospitalists during consult interactions regardless of whether the hospitalist initiates the teaching–learning interaction.

Barriers to and Facilitating Factors of Effective Consultation

Participants reported that multiple factors affected patient care and their own learning during inpatient consultation (Figure 1). Consultant pushback, high hospitalist clinical workload, a perception that consultants had limited time, and minimal in-person interactions were all seen as factors that negatively affected the consult interaction. These generally affected both learning and patient care. Conversely, working on an interesting clinical case, more hospitalist free time, positive interaction with the consultant, and having previously worked with the consultant positively affected both learning and patient care (Figure 1).

Fellow Versus Attending Interactions

Respondents indicated that interacting directly with the consult attending was superior to hospitalist–fellow interactions in all aspects of care but particularly with respect to pushback, confidence in recommendations, professionalism, and hospitalist learning (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe hospitalist attending practices, attitudes, and perceptions of internal medicine subspecialty consultation. Our findings, which focus on the interaction between hospitalists and internal medicine subspecialty attendings and fellows, outline the hospitalist perspective on consultant interactions and identify a number of factors that are amenable to intervention. We found that hospitalists perceive the consult interaction to be important for patient care and a valuable opportunity for their own learning. In-person communication was seen as an important component of effective consultation but was reported to occur in a minority of consultations. We demonstrate that hospitalist–subspecialty attending consult interactions are perceived more positively than hospitalist–fellow interactions. Finally, we describe barriers and facilitating factors that may inform future interventions targeting this important interaction.

Effective communication between consultants and the primary team is critical for both patient care and teaching interactions.4-7 Pushback on consultation was reported to be the most significant barrier to hospitalist learning and had a major impact on patient care. Because hospitalists are attending physicians, we hypothesized that they may perceive pushback from fellows less frequently than residents.4 However, in our study, hospitalists reported pushback to be relatively frequent in their daily practice. Moreover, hospitalists reported a strong preference for in-person interactions with consultants, but our study demonstrated that such interactions are relatively infrequent. Researchers in studies of resident–fellow consult interactions have noted similar findings, suggesting that hospitalists and internal medicine residents face similar challenges during consultation.4-6 Hospitalists reported that positive interpersonal interactions and personal familiarity with the consultant positively affected the consult interaction. Most importantly, these effects were perceived to affect both hospitalist learning and patient care, suggesting the importance of interpersonal interactions in consultative medicine.

In an era of increasing clinical workload, the consult interaction represents an important workplace-based learning opportunity.4 Centered on a consult question, the hospitalist–consultant interaction embodies a teachable moment and can be an efficient opportunity to learn because both parties are familiar with the patient. Indeed, survey respondents reported that they frequently learned from consultation, and there was a strong preference for more teaching from consultants in this setting. However, the hospitalist–fellow consult interaction is unique because attending hospitalists are frequently communicating with fellow trainees, which could limit fellows’ confidence in their role as teachers and hospitalists’ perception of their role as learners. Our study identifies a number of barriers and facilitating factors (including communication, pushback, familiarity, and clinical workload) that affect the hospitalist–consultant teaching interaction and may be amenable to intervention.

Hospitalists expressed a consistent preference for interacting with attending subspecialists compared to clinical fellows during consultation. Preference for interaction with attendings was strongest in the areas of pushback, confidence in recommendations, professionalism, and learning from consultation. Some of the factors that relate to consult service structure and fellow experience, such as timeliness of consultation and confidence in recommendations, may not be amenable to intervention. For instance, fellows must first see and then staff the consult with their attending prior to leaving formal recommendations, which makes their communication less timely than that of attending physicians, when they are the primary consultant. However, aspects of the hospitalist–consultant interaction (such as professionalism, ease of communication, and pushback) should not be affected by the difference in experience between fellows and attending physicians. The reasons for such perceptions deserve further exploration; however, differences in incentive structures, workload, and communication skills between fellows and attending consultants may be potential explanations.

Our findings suggest that interventions aimed at enhancing hospitalist–consultant interactions focus on enhancing direct communication and teaching while limiting the perception of pushback. A number of interventions that are primarily focused on instituting a systematic approach to requesting consultation have shown an improvement in resident and medical student consult communication17,18 as well as resident–fellow teaching interactions.9 However, it is not clear whether these interventions would be effective given that hospitalists have more experience communicating with consultants than trainees. Given the unique nature of the hospitalist–consultant interaction, multiple barriers may need to be addressed in order to have a significant impact. Efforts to increase direct communication, such as a mechanism for hospitalists to make and request in-person or direct verbal communication about a particular consultation during the consult request, can help consultants prioritize direct communication with hospitalists for specific patients. Familiarizing fellows with hospitalist workflow and the locations of hospitalist workrooms also may promote in-person communication. Fellowship training can focus on enhancing fellow teaching and communication skills,19-22 particularly as they relate to hospitalists. Fellows in particular may benefit because the hospitalist–fellow teaching interaction may be bidirectional, with hospitalists having expertise in systems practice and quality efforts that can inform fellows’ practice. Furthermore, interacting with hospitalists is an opportunity for fellows to practice professional interactions, which will be critical to their careers. Increasing familiarity between fellows and hospitalists through joint events may also serve to enhance the interaction. Finally, enabling hospitalists to provide feedback to fellows stands to benefit both parties because multisource feedback is an important tool in assessing trainee competence and improving performance.23 However, we should note that because our study focused on hospitalist perceptions, an exploration of subspecialty fellows’ and attendings’ perceptions of the hospitalist–consultant interaction would provide additional, important data for shaping interventions.

Strengths of our study include the inclusion of multiple study sites, which may increase generalizability; however, our study has several limitations. The incomplete response rate reduces both generalizability and statistical power and may have created selection or nonresponder bias. However, low response rates occur commonly when surveying medical professionals, and our results are consistent with many prior hospitalist survey studies.24-26 Further, we conducted our study at a single time point; therefore, we could not evaluate the effect of fellow experience on hospitalist perceptions. However, we conducted our study in the second half of the academic year, when fellows had already gained considerable experience in the consultation setting. We did not capture participants’ institutional affiliations; therefore, a subgroup analysis by institution could not be performed. Additionally, our study reflects hospitalist perception rather than objectively measured communication practices between hospitalists and consultants, and it does not include the perspective of subspecialists. The specific needs of nurse practitioners and physicians’ assistants, who were excluded from this study, should also be evaluated in future research. Lastly, this is a hypothesis-generating study and should be replicated in a national cohort.

CONCLUSION

The hospitalists represented in our sample population perceived the consult interaction to be important for patient care and a valuable opportunity for their own learning. Participants expressed that they would like to increase direct communication with consultants and enhance consultant–hospitalist teaching interactions. Multiple barriers to effective hospitalist–consultant interactions (including communication, pushback, and hospitalist–consultant familiarity) are amenable to intervention.

Disclosure

The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

1. Kravolec PD, Miller JA, Wellikson L, Huddleston JM. The status of hospital medicine groups in the United States. J Hosp Med.2006;1(2):75-80. PubMed

2. Cai Q, Bruno CJ, Hagedorn CH, Desbiens NA. Temporal trends over ten years in formal inpatient gastroenterology consultations at an inner-city hospital. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36(1):34-38. PubMed

3. Ta K, Gardner GC. Evaluation of the activity of an academic rheumatology consult service over 10 years: using data to shape curriculum. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(3):563-566. PubMed

4. Miloslavsky EM, McSparron JI, Richards JB, Puig A, Sullivan AM. Teaching during consultation: factors affecting the resident-fellow teaching interaction. Med Educ. 2015;49(7):717-730. PubMed

5. Chan T, Sabir K, Sanhan S, Sherbino J. Understanding the impact of residents’ interpersonal relationships during emergency department referrals and consultations. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(4):576-581. PubMed

6. Chan T, Bakewell F, Orlich D, Sherbino J. Conflict prevention, conflict mitigation, and manifestations of conflict during emergency department consultations. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(3):308-313. PubMed

7. Goldman L, Lee T, Rudd P. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143(9):1753-1755. PubMed

8. Adams T. Barriers to hospitalist fellow interactions. Med Educ. 2016;50(3):370. PubMed

9. Gupta S, Alladina J, Heaton K, Miloslavsky E. A randomized trial of an intervention to improve resident-fellow teaching interaction on the wards. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):276. PubMed

10. Day LW, Cello JP, Madden E, Segal M. Prospective assessment of inpatient gastrointestinal consultation requests in an academic teaching hospital. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(3):484-489. PubMed

11. Kessler C, Kutka BM, Badillo C. Consultation in the emergency department: a qualitative analysis and review. J Emerg Med. 2012;42(6):704-711. PubMed

12. Salerno SM, Hurst FP, Halvorson S, Mercado DL. Principles of effective consultation: an update for the 21st-century consultant. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(3):271-275. PubMed

13. Muzin LJ. Understanding the process of medical referral: part 1: critique of the literature. Can Fam Physician. 1991;37:2155-2161. PubMed

14. Muzin LJ. Understanding the process of medical referral: part 5: communication. Can Fam Physician. 1992;38:301-307. PubMed

15. Wadhwa A, Lingard L. A qualitative study examining tensions in interdoctor telephone consultations. Med Educ. 2006;40(8):759-767. PubMed

16. Grant IN, Dixon AS. “Thank you for seeing this patient”: studying the quality of communication between physicians. Can Fam Physician. 1987;33:605-611. PubMed

17. Kessler CS, Afshar Y, Sardar G, Yudkowsky R, Ankel F, Schwartz A. A prospective, randomized, controlled study demonstrating a novel, effective model of transfer of care between physicians: the 5 Cs of consultation. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(8):968-974. PubMed

18. Podolsky A, Stern DTP. The courteous consult: a CONSULT card and training to improve resident consults. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(1):113-117. PubMed

19. Tofil NM, Peterson DT, Harrington KF, et al. A novel iterative-learner simulation model: fellows as teachers. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2014;6(1):127-132. PubMed

20. Kempainen RR, Hallstrand TS, Culver BH, Tonelli MR. Fellows as teachers: the teacher-assistant experience during pulmonary subspecialty training. Chest. 2005;128(1):401-406. PubMed

21. Backes CH, Reber KM, Trittmann JK, et al. Fellows as teachers: a model to enhance pediatric resident education. Med. Educ. Online. 2011;16:7205. PubMed

22. Miloslavsky EM, Degnan K, McNeill J, McSparron JI. Use of Fellow as Clinical Teacher (FACT) Curriculum for Teaching During Consultation: Effect on Subspecialty Fellow Teaching Skills. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(3):345-350 PubMed

23. Donnon T, Al Ansari A, Al Alawi S, Violato C. The reliability, validity, and feasibility of multisource feedback physician assessment: a systematic review. Acad. Med. 2014;89(3):511-516. PubMed

24. Monash B, Najafi N, Mourad M, et al. Standardized attending rounds to improve the patient experience: A pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(3):143-149. PubMed

25. Allen-Dicker J, Auerbach A, Herzig SJ. Perceived safety and value of inpatient “very important person” services. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(3):177-179. PubMed

26. Do D, Munchhof AM, Terry C, Emmett T, Kara A. Research and publication trends in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):148-154. PubMed

1. Kravolec PD, Miller JA, Wellikson L, Huddleston JM. The status of hospital medicine groups in the United States. J Hosp Med.2006;1(2):75-80. PubMed

2. Cai Q, Bruno CJ, Hagedorn CH, Desbiens NA. Temporal trends over ten years in formal inpatient gastroenterology consultations at an inner-city hospital. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36(1):34-38. PubMed

3. Ta K, Gardner GC. Evaluation of the activity of an academic rheumatology consult service over 10 years: using data to shape curriculum. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(3):563-566. PubMed

4. Miloslavsky EM, McSparron JI, Richards JB, Puig A, Sullivan AM. Teaching during consultation: factors affecting the resident-fellow teaching interaction. Med Educ. 2015;49(7):717-730. PubMed

5. Chan T, Sabir K, Sanhan S, Sherbino J. Understanding the impact of residents’ interpersonal relationships during emergency department referrals and consultations. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(4):576-581. PubMed

6. Chan T, Bakewell F, Orlich D, Sherbino J. Conflict prevention, conflict mitigation, and manifestations of conflict during emergency department consultations. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(3):308-313. PubMed

7. Goldman L, Lee T, Rudd P. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143(9):1753-1755. PubMed

8. Adams T. Barriers to hospitalist fellow interactions. Med Educ. 2016;50(3):370. PubMed

9. Gupta S, Alladina J, Heaton K, Miloslavsky E. A randomized trial of an intervention to improve resident-fellow teaching interaction on the wards. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):276. PubMed

10. Day LW, Cello JP, Madden E, Segal M. Prospective assessment of inpatient gastrointestinal consultation requests in an academic teaching hospital. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(3):484-489. PubMed

11. Kessler C, Kutka BM, Badillo C. Consultation in the emergency department: a qualitative analysis and review. J Emerg Med. 2012;42(6):704-711. PubMed

12. Salerno SM, Hurst FP, Halvorson S, Mercado DL. Principles of effective consultation: an update for the 21st-century consultant. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(3):271-275. PubMed

13. Muzin LJ. Understanding the process of medical referral: part 1: critique of the literature. Can Fam Physician. 1991;37:2155-2161. PubMed

14. Muzin LJ. Understanding the process of medical referral: part 5: communication. Can Fam Physician. 1992;38:301-307. PubMed

15. Wadhwa A, Lingard L. A qualitative study examining tensions in interdoctor telephone consultations. Med Educ. 2006;40(8):759-767. PubMed

16. Grant IN, Dixon AS. “Thank you for seeing this patient”: studying the quality of communication between physicians. Can Fam Physician. 1987;33:605-611. PubMed

17. Kessler CS, Afshar Y, Sardar G, Yudkowsky R, Ankel F, Schwartz A. A prospective, randomized, controlled study demonstrating a novel, effective model of transfer of care between physicians: the 5 Cs of consultation. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(8):968-974. PubMed

18. Podolsky A, Stern DTP. The courteous consult: a CONSULT card and training to improve resident consults. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(1):113-117. PubMed

19. Tofil NM, Peterson DT, Harrington KF, et al. A novel iterative-learner simulation model: fellows as teachers. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2014;6(1):127-132. PubMed

20. Kempainen RR, Hallstrand TS, Culver BH, Tonelli MR. Fellows as teachers: the teacher-assistant experience during pulmonary subspecialty training. Chest. 2005;128(1):401-406. PubMed

21. Backes CH, Reber KM, Trittmann JK, et al. Fellows as teachers: a model to enhance pediatric resident education. Med. Educ. Online. 2011;16:7205. PubMed

22. Miloslavsky EM, Degnan K, McNeill J, McSparron JI. Use of Fellow as Clinical Teacher (FACT) Curriculum for Teaching During Consultation: Effect on Subspecialty Fellow Teaching Skills. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(3):345-350 PubMed

23. Donnon T, Al Ansari A, Al Alawi S, Violato C. The reliability, validity, and feasibility of multisource feedback physician assessment: a systematic review. Acad. Med. 2014;89(3):511-516. PubMed

24. Monash B, Najafi N, Mourad M, et al. Standardized attending rounds to improve the patient experience: A pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(3):143-149. PubMed

25. Allen-Dicker J, Auerbach A, Herzig SJ. Perceived safety and value of inpatient “very important person” services. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(3):177-179. PubMed

26. Do D, Munchhof AM, Terry C, Emmett T, Kara A. Research and publication trends in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):148-154. PubMed

©2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Simulation Resident‐as‐Teacher Program

Residency training, in addition to developing clinical competence among trainees, is charged with improving resident teaching skills. The Liaison Committee on Medical Education and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education require that residents be provided with training or resources to develop their teaching skills.[1, 2] A variety of resident‐as‐teacher (RaT) programs have been described; however, the optimal format of such programs remains in question.[3] High‐fidelity medical simulation using mannequins has been shown to be an effective teaching tool in various medical specialties[4, 5, 6, 7] and may prove to be useful in teacher training.[8] Teaching in a simulation‐based environment can give participants the opportunity to apply their teaching skills in a clinical environment, as they would on the wards, but in a more controlled, predictable setting and without compromising patient safety. In addition, simulation offers the opportunity to engage in deliberate practice by allowing teachers to facilitate the same case on multiple occasions with different learners. Deliberate practice, which involves task repetition with feedback aimed at improving performance, has been shown to be important in developing expertise.[9]

We previously described the first use of a high‐fidelity simulation curriculum for internal medicine (IM) interns focused on clinical decision‐making skills, in which second‐ and third‐year residents served as facilitators.[10, 11] Herein, we describe a RaT program in which residents participated in a workshop, then served as facilitators in the intern curriculum and received feedback from faculty. We hypothesized that such a program would improve residents' teaching and feedback skills, both in the simulation environment and on the wards.

METHODS

We conducted a single‐group study evaluating teaching and feedback skills among upper‐level resident facilitators before and after participation in the RaT program. We measured residents' teaching skills using pre‐ and post‐program self‐assessments as well as evaluations completed by the intern learners after each session and at the completion of the curriculum.

Setting and Participants

We embedded the RaT program within a simulation curriculum administered July to October of 2013 for all IM interns at Massachusetts General Hospital (interns in the preliminary program who planned to pursue another field after the completion of the intern year were excluded) (n = 52). We invited postgraduate year (PGY) II and III residents (n = 102) to participate in the IM simulation program as facilitators via email. The curriculum consisted of 8 cases focusing on acute clinical scenarios encountered on the general medicine wards. The cases were administered during 1‐hour sessions 4 mornings per week from 7 AM to 8 AM prior to clinical duties. Interns completed the curriculum over 4 sessions during their outpatient rotation. The case topics were (1) hypertensive emergency, (2) post‐procedure bleed, (3) congestive heart failure, (4) atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response, (5) altered mental status/alcohol withdrawal, (6) nonsustained ventricular tachycardia heralding acute coronary syndrome, (7) cardiac tamponade, and (8) anaphylaxis. During each session, groups of 2 to 3 interns worked through 2 cases using a high‐fidelity mannequin (Laerdal 3G, Wappingers Falls, NY) with 2 resident facilitators. One facilitator operated the mannequin, while the other served as a nurse. Each case was followed by a structured debriefing led by 1 of the resident facilitators (facilitators switched roles for the second case). The number of sessions facilitated varied for each resident based on individual schedules and preferences.

Four senior residents who were appointed as simulation leaders (G.A.A., J.K.H., R.K., Z.S.) and 2 faculty advisors (P.F.C., E.M.M.) administered the program. Simulation resident leaders scheduled facilitators and interns and participated in a portion of simulation sessions as facilitators, but they were not analyzed as participants for the purposes of this study. The curriculum was administered without interfering with clinical duties, and no additional time was protected for interns or residents participating in the curriculum.

Resident‐as‐Teacher Program Structure

We invited participating resident facilitators to attend a 1‐hour interactive workshop prior to serving as facilitators. The workshop focused on building learner‐centered and small‐group teaching skills, as well as introducing residents to a 5‐stage debriefing framework developed by the authors and based on simulation debriefing best practices (Table 1).[12, 13, 14]

| Stage of Debriefing | Action | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Emotional response | Elicit learners' emotions about the case | It is important to acknowledge and address both positive and negative emotions that arise during the case before debriefing the specific medical and communications aspects of the case. Unaddressed emotional responses may hinder subsequent debriefing. |

| Objectives* | Elicit learners' objectives and combine them with the stated learning objectives of the case to determine debriefing objectives | The limited amount of time allocated for debriefing (1520 minutes) does not allow the facilitator to cover all aspects of medical management and communication skills in a particular case. Focusing on the most salient objectives, including those identified by the learners, allows the facilitator to engage in learner‐centered debriefing. |

| Analysis | Analyze the learners' approach to the case | Analyzing the learners' approach to the case using the advocacy‐inquiry method[11] seeks to uncover the learner's assumptions/frameworks behind the decision made during the case. This approach allows the facilitator to understand the learners' thought process and target teaching points to more precisely address the learners' needs. |

| Teaching | Address knowledge gaps and incorrect assumptions | Learner‐centered debriefing within a limited timeframe requires teaching to be brief and targeted toward the defined objectives. It should also address the knowledge gaps and incorrect assumptions uncovered during the analysis phase. |

| Summary | Summarize key takeaways | Summarizing highlights the key points of the debriefing and can be used to suggest further exploration of topics through self‐study (if necessary). |

Resident facilitators were observed by simulation faculty and simulation resident leaders throughout the intern curriculum and given structured feedback either in‐person immediately after completion of the simulation session or via a detailed same‐day e‐mail if the time allotted for feedback was not sufficient. Feedback was structured by the 5 stages of debriefing described in Table 1, and included soliciting residents' observations on the teaching experience and specific behaviors observed by faculty during the scenarios. E‐mail feedback (also structured by stages of debriefing and including observed behaviors) was typically followed by verbal feedback during the next simulation session.

The RaT program was composed of 3 elements: the workshop, case facilitation, and direct observation with feedback. Because we felt that the opportunity for directly observed teaching and feedback in a ward‐like controlled environment was a unique advantage offered by the simulation setting, we included all residents who served as facilitators in the analysis, regardless of whether or not they had attended the workshop.

Evaluation Instruments

Survey instruments were developed by the investigators, reviewed by several experts in simulation, pilot tested among residents not participating in the simulation program, and revised by the investigators.

Pre‐program Facilitator Survey

Prior to the RaT workshop, resident facilitators completed a baseline survey evaluating their preparedness to teach and give feedback on the wards and in a simulation‐based setting on a 5‐point scale (see Supporting Information, Appendix I, in the online version of this article).

Post‐program Facilitator Survey

Approximately 3 weeks after completion of the intern simulation curriculum, resident facilitators were asked to complete an online post‐program survey, which remained open for 1 month (residents completed this survey anywhere from 3 weeks to 4 months after their participation in the RaT program depending on the timing of their facilitation). The survey asked residents to evaluate their comfort with their current post‐program teaching skills as well as their pre‐program skills in retrospect, as previous research demonstrated that learners may overestimate their skills prior to training programs.[15] Resident facilitators could complete the surveys nonanonymously to allow for matched‐pairs analysis of the change in teaching skills over the course of the program (see Supporting Information, Appendix II, in the online version of this article).

Intern Evaluation of Facilitator Debriefing Skills

After each case, intern learners were asked to anonymously evaluate the teaching effectiveness of the lead resident facilitator using the adapted Debriefing Assessment for Simulation in Healthcare (DASH) instrument.[16] The DASH instrument evaluated the following domains: (1) instructor maintained an engaging context for learning, (2) instructor structured the debriefing in an organized way, (3) instructor provoked in‐depth discussions that led me to reflect on my performance, (4) instructor identified what I did well or poorly and why, (5) instructor helped me see how to improve or how to sustain good performance, (6) overall effectiveness of the simulation session (see Supporting Information, Appendix III, in the online version of this article).

Post‐program Intern Survey

Two months following the completion of the simulation curriculum, intern learners received an anonymous online post‐program evaluation assessing program efficacy and resident facilitator teaching (see Supporting Information, Appendix IV, in the online version of this article).

Statistical Analysis

Teaching skills and learners' DASH ratings were compared using the Student t test, Pearson 2 test, and Fisher exact test as appropriate. Pre‐ and post‐program rating of teaching skills was undertaken in aggregate and as a matched‐pairs analysis.

The study was approved by the Partners Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS