User login

COVID-19 and the risk of homicide-suicide among older adults

On March 25, 2020, in Cambridge, United Kingdom, a 71-year-old man stabbed his 71-year-old wife before suffocating himself to death. The couple was reportedly anxious about the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic lockdown measures and were on the verge of running out of food and medicine.1

One week later, in Chicago, Illinois, a 54-year-old man shot and killed his female partner, age 54, before killing himself. The couple was tested for COVID-19 2 days earlier and the man believed they had contracted the virus; however, the test results for both of them had come back negative.2

Intimate partner homicide-suicide is the most dramatic domestic abuse outcome.3 Homicide-suicide is defined as “homicide committed by a person who subsequently commits suicide within one week of the homicide. In most cases the subsequent suicide occurs within a 24-hour period.”4 Approximately one-quarter of all homicide-suicides are committed by persons age ≥55 years.5,6 We believe that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the risk of homicide-suicide among older adults may be increased due to several factors, including:

- physical distancing and quarantine measures. Protocols established to slow the spread of the virus may be associated with increased rates of depression and anxiety7 and an increased risk of suicide among older adults8

- increased intimate partner violence9

- increased firearm ownership rates in the United States.10

In this article, we review studies that identified risk factors for homicide-suicide among older adults, discuss the impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had on these risks, and describe steps clinicians can take to intervene.

A review of the literature

To better characterize the perpetrators of older adult homicide-suicide, we conducted a literature search of relevant terms. We identified 9 original research publications that examined homicide-suicide in older adults.

Bourget et al11 (2010) reviewed coroners’ charts of individuals killed by an older (age ≥65) spouse or family member from 1992 through 2007 in Quebec, Canada. They identified 19 cases of homicide-suicide, 17 (90%) of which were perpetrated by men. Perpetrators and victims were married (63%), in common-law relationships (16%), or separated/divorced (16%). A history of domestic violence was documented in 4 (21%) cases. The authors found that 13 of 15 perpetrators (87%) had “major depression” and 2 perpetrators had a psychotic disorder. Substance use at the time of the event was confirmed in 6 (32%) cases. Firearms and strangulation were the top methods used to carry out the homicide-suicide.11

Cheung et al12 (2016) conducted a review of coroners’ records of homicide-suicide cases among individuals age ≥65 in New Zealand from 2007 through 2012. In all 4 cases, the perpetrators were men, and their victims were predominantly female, live-in family members. Two cases involved men with a history of domestic violence who were undergoing significant changes in their home and social lives. Both men had a history suggestive of depression and used a firearm to carry out the homicide-suicide.12

Continue to: Cohen et al

Cohen et al13 (1998) conducted a review of coroners’ records from 1988 through 1994 in 2 regions in Florida. They found 48 intimate partner homicide-suicide cases among “old couples” (age ≥55). All were perpetrated by men. The authors identified sociocultural differences in risk factors between the 2 regions. In west-central Florida, perpetrators and victims were predominantly white and in a spousal relationship. Domestic violence was documented in <4% of cases. Approximately 55% of the couples were reported to be ill, and a substantial proportion were documented to be declining in health. One-quarter of the perpetrators and one-third of the victims had “pain and suffering.” More than one-third of perpetrators were reported to have “depression,” 15% were reported to have talked about suicide, and 4% had a history of a suicide attempt. Only 11% of perpetrators were described as abusing substances.

The authors noted several differences in cases in southeastern Florida. Approximately two-thirds of the couples were Hispanic, and 14% had a history of domestic violence. A minority of the couples were in a live-in relationship. Less than 15% of the perpetrators and victims were described as having a decline in health. Additionally, only 19% of perpetrators were reported to have “depression,” and none of the perpetrators had a documented history of attempted suicide or substance abuse. No information was provided regarding the methods used to carry out the homicide-suicide in the southeastern region.13 Financial stress was not a factor in either region.

Malphurs et al14 (2001) used the same database described in the Cohen et al13 study to compare 27 perpetrators of homicide-suicide to 36 age-matched suicide decedents in west central Florida. They found that homicide-suicide perpetrators were significantly less likely to have health problems and were 3 times more likely to be caregivers to their spouses. Approximately 52% of perpetrators had at least 1 documented psychiatric symptom (“depression” and/or substance abuse or other), but only 5% were seeking mental health services at the time of death.14

De Koning and Piette15 (2014) conducted a retrospective medicolegal chart review from 1935 to 2010 to identify homicide-suicide cases in West and East Flanders, Belgium. They found 19 cases of intimate partner homicide-suicide committed by offenders age ≥55 years. Ninety-five percent of the perpetrators were men who killed their female partners. In one-quarter of the cases, either the perpetrator or the victim had a health issue; 21% of the perpetrators were documented as having depression and 27% had alcohol intoxication at the time of death. A motive was documented in 14 out of 19 cases; “mercy killing” was determined as the motive in 6 (43%) cases and “amorous jealousy” in 5 cases (36%).15 Starting in the 1970s, firearms were the most prevalent method used to kill a partner.

Logan et al16 (2019) used data from the National Violent Death Reporting System between 2003 and 2015 to identify characteristics that differentiated male suicide decedents from male perpetrators of intimate partner homicide-suicide. They found that men age 50 to 64 years were 3 times more likely than men age 18 to 34 years to commit intimate partner homicide-suicide, and that men age ≥65 years were approximately 5 times more likely than men age 18 to 34 years to commit intimate partner homicide-suicide. The authors found that approximately 22% of all perpetrators had a documented history of physical domestic violence, and close to 17% had a prior interaction with the criminal justice system. Furthermore, one-third of perpetrators had relationship difficulties and were in the process of a breakup. Health issues were prevalent in 34% of the victims and 26% of the perpetrators. Perpetrator-caregiver burden was reported as a contributing factor for homicide-suicide in 16% of cases. In 27% of cases, multiple health-related contributing factors were mentioned.16

Continue to: Malphurs and Cohen

Malphurs and Cohen5 (2002) reviewed American newspapers from 1997 through 1999 and identified 673 homicide-suicide events, of which 152 (27%) were committed by individuals age ≥55 years. The victims and perpetrators (95% of which were men) were intimate partners in three-quarters of cases. In nearly one-third of cases, caregiving was a contributing factor for the homicide-suicide. A history of or a pending divorce was reported in nearly 14% of cases. Substance use history was rarely recorded. Firearms were used in 88% of the homicide-suicide cases.5

Malphurs and Cohen17 (2005) reviewed coroner records between 1998 and 1999 in Florida and compared 20 cases of intimate partner homicide-suicide involving perpetrators age ≥55 years with matched suicide decedents. They found that 60% of homicide-suicide perpetrators had documented health issues. The authors reported that a “recent change in health status” was more prevalent among perpetrators compared with decedents. Perpetrators were also more likely to be caregivers to their spouses. The authors found that 65% of perpetrators were reported to have a “depressed mood” and 15% of perpetrators had reportedly threatened suicide prior to the incident. However, none of the perpetrators tested positive for antidepressants as documented on post-mortem toxicology reports. Firearms were used in 100% of homicide-suicide cases.17

Salari3 (2007) reviewed multiple American media sources and published police reports between 1999 and 2005 to retrieve data about intimate partner homicide-suicide events in the United States. There were 225 events identified where the perpetrator and/or the victim were age ≥60 years. Ninety-six percent of the perpetrators were men and most homicide-suicide events were committed at the home. A history of domestic violence was reported in 14% of homicide-suicide cases. Thirteen percent of couples were separated or divorced. The perpetrator and/or victim had health issues in 124 (55%) events. Dementia was reported in 7.5% of cases, but overwhelmingly among the victims. Substance abuse was rarely mentioned as a contributing factor. In three-quarters of cases where a motive was described, the perpetrator was “suicidal”; however, a “suicide pact” was mentioned in only 4% of cases. Firearms were used in 87% of cases.3

Focus on common risk factors

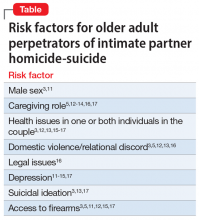

The scarcity and heterogeneity of research regarding older adult homicide-suicide were major limitations to our review. Because most of the studies we identified had a small sample size and limited information regarding the mental health of victims and perpetrators, it would be an overreach to claim to have identified a typical profile of an older perpetrator of homicide-suicide. However, the literature has repeatedly identified several common characteristics of such perpetrators. They are significantly more likely to be men who use firearms to murder their intimate partners and then die by suicide in their home (Table3,5,11-17). Health issues afflicting 1 or both individuals in the couple appear to be a contributing factor, particularly when the perpetrator is in a caregiving role. Relational discord, with or without a history of domestic violence, increases the risk of homicide-suicide. Finally, older perpetrators are highly likely to be depressed and have suicidal ideations.

How COVID-19 affects these risks

Although it is too early to determine if there is a causal relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and an increase in homicide-suicide, the pandemic is likely to promote risk factors for these events, especially among older adults. Confinement measures put into place during the pandemic context have already been shown to increase rates of domestic violence18 and depression and anxiety among older individuals.7 Furthermore,

Continue to: Late-life psychiatric disorders

Late-life psychiatric disorders

Early recognition and effective treatment of late-life psychiatric disorders is crucial. Unfortunately, depression in geriatric patients is often underdiagnosed and undertreated.20 Older adults have more frequent contact with their primary care physicians, and rarely consult mental health professionals.21,22 Several models of integrated depression care within primary care settings have shown the positive impact of this collaborative approach in treating late-life depression and preventing suicide in older individuals.23 Additionally, because alcohol abuse is also a risk factor for domestic violence and breaking the law in this population,24,25 older adults should be screened for alcohol use disorders, and referred to treatment when necessary.

Take steps to keep patients safe

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, there are several steps clinicians need to keep in mind when interacting with older patients:

- Screen for depressive symptoms, suicidality, and alcohol and substance use disorders. Individuals who have tested positive for COVID-19 or who have been in contact with a carrier are a particularly vulnerable population.

- Screen for domestic violence and access to weapons at home.4 Any older adult who has a psychiatric disorder and/or suicide ideation should receive immediate intervention through a social worker that includes providing gun-risk education to other family members or contacting law-enforcement officials.26

- Refer patients with a suspected psychiatric disorder to specialized mental health clinicians. Telemental health services can provide rapid access to subspecialists, allowing patients to be treated from their homes.27 These services need to be promoted among older adults during this critical period and reimbursed by public and private insurance systems to ensure accessibility and affordability.28

- Create psychiatric inpatient units specifically designed for suicidal and/or homicidal patients with COVID-19.

Additionally, informing the public about these major health issues is crucial. The media can raise awareness about domestic violence and depression among older adults; however, this should be done responsibly and with accuracy to prevent the spread of misinformation, confusion, fear, and panic.29

Bottom Line

The mental health burden of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic has significantly impacted individuals who are older and most vulnerable. Reducing the incidence of homicide-suicide among older adults requires timely screening and interventions by primary care providers, mental health specialists, social workers, media, and governmental agencies.

Related Resources

- Saeed SA, Hebishi K. The psychiatric consequences of COVID-19: 8 studies. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(11):22-24,28-30,32-35.

- Schwab-Reese LM, Murfree L, Coppola EC, et al. Homicidesuicide across the lifespan: a mixed methods examination of factors contributing to older adult perpetration. Aging Ment Health. 2020;20:1-9.

1. Christodoulou H. LOCKDOWN ‘MURDER-SUICIDE’ OAP, 71, ‘stabbed wife to death then killed himself as he worried about coping with coronavirus lockdown.’ The Sun. Updated April 4, 2020. Accessed December 22, 2020. https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/11327095/coronavirus-lockdown-murder-suicide-cambridge/

2. Farberov S. Illinois man, 54, shoots dead his wife then kills himself in murder-suicide because he feared they had coronavirus - but tests later show the couple were NOT ill. Updated April 6, 2020. Accessed December 22, 2020. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8191933/Man-kills-wife-feared-coronavirus.html

3. Salari S. Patterns of intimate partner homicide suicide in later life: strategies for prevention. Clin Interv Aging. 2007;2(3):441-452.

4. Kotzé C, Roos JL. Homicide–suicide: practical implications for risk reduction and support services at primary care level. South African Family Practice. 2019;61(4):165-169.

5. Malphurs JE, Cohen D. A newspaper surveillance study of homicide-suicide in the United States. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2002;23(2):142-148.

6. Eliason S. Murder-suicide: a review of the recent literature. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2009;37(3):371-376.

7. Armitage R, Nellums LB. COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):e256. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30061-X

8. Gunnell D, Appleby L, Arensman E, et al. Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7(6):468-471.

9. Gosangi B, Park H, Thomas R, et al. Exacerbation of physical intimate partner violence during COVID-19 pandemic. Radiology. 2021;298(1):E38-E45.

10. Mannix R, Lee LK, Fleegler EW. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and firearms in the United States: will an epidemic of suicide follow? Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(3):228-229.

11. Bourget D, Gagne P, Whitehurst L. Domestic homicide and homicide-suicide: the older offender. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2010;38(3):305-311.

12. Cheung G, Hatters Friedman S, Sundram F. Late-life homicide-suicide: a national case series in New Zealand. Psychogeriatrics. 2016;16(1):76-81.

13. Cohen D, Llorente M, Eisdorfer C. Homicide-suicide in older persons. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(3):390-396.

14. Malphurs JE, Eisdorfer C, Cohen D. A comparison of antecedents of homicide-suicide and suicide in older married men. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(1):49-57.

15. De Koning E, Piette MHA. A retrospective study of murder–suicide at the Forensic Institute of Ghent University, Belgium: 1935–2010. Med Sci Law. 2014;54(2):88-98.

16. Logan JE, Ertl A, Bossarte R. Correlates of intimate partner homicide among male suicide decedents with known intimate partner problems. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2019;49(6):1693-1706.

17. Malphurs JE, Cohen D. A statewide case-control study of spousal homicide-suicide in older persons. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(3):211-217.

18. Sanford A. ‘Horrifying surge in domestic violence’ against women amid coronavirus-lockdowns, UN chief warns. Euronews. Published June 4, 2020. Accessed December 22, 2020. https://www.euronews.com/2020/04/06/horrifying-surge-in-domestic-violence-against-women-amid-coronavirus-lockdowns-un-chief-w

19. Appel JM. Intimate partner homicide in elderly populations. In: Friedman SH, ed. Family murder: pathologies of love and hate. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019:131-142.

20. Hall CA, Reynolds-III CF. Late-life depression in the primary care setting: challenges, collaborative care, and prevention. Maturitas. 2014;79(2):147-152.

21. Unützer J. Diagnosis and treatment of older adults with depression in primary care. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52(3):285-292.

22. Byers AL, Arean PA, Yaffe K. Low use of mental health services among older Americans with mood and anxiety disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(1):66-72.

23. Bruce ML, Sirey JA. Integrated care for depression in older primary care patients. Can J Psychiatry. 2018;63(7):439-446.

24. Rao R, Roche A. Substance misuse in older people. BMJ. 2017;358:j3885. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3885

25. Ghossoub E, Khoury R. Prevalence and correlates of criminal behavior among the non-institutionalized elderly: results from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2018;31(4):211-222.

26. Slater MAG. Older adults at risk for suicide. In: Berkman B. Handbook of social work in health and aging. Oxford University Press; 2006:149-161.

27. Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1679-1681.

28. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. President Trump expands telehealth benefits for Medicare beneficiaries during COVID-19 outbreak. Published March 17, 2020. Accessed December 23, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/president-trump-expands-telehealth-benefits-medicare-beneficiaries-during-covid-19-outbreak

29. Mian A, Khan S. Coronavirus: the spread of misinformation. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):89.

On March 25, 2020, in Cambridge, United Kingdom, a 71-year-old man stabbed his 71-year-old wife before suffocating himself to death. The couple was reportedly anxious about the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic lockdown measures and were on the verge of running out of food and medicine.1

One week later, in Chicago, Illinois, a 54-year-old man shot and killed his female partner, age 54, before killing himself. The couple was tested for COVID-19 2 days earlier and the man believed they had contracted the virus; however, the test results for both of them had come back negative.2

Intimate partner homicide-suicide is the most dramatic domestic abuse outcome.3 Homicide-suicide is defined as “homicide committed by a person who subsequently commits suicide within one week of the homicide. In most cases the subsequent suicide occurs within a 24-hour period.”4 Approximately one-quarter of all homicide-suicides are committed by persons age ≥55 years.5,6 We believe that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the risk of homicide-suicide among older adults may be increased due to several factors, including:

- physical distancing and quarantine measures. Protocols established to slow the spread of the virus may be associated with increased rates of depression and anxiety7 and an increased risk of suicide among older adults8

- increased intimate partner violence9

- increased firearm ownership rates in the United States.10

In this article, we review studies that identified risk factors for homicide-suicide among older adults, discuss the impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had on these risks, and describe steps clinicians can take to intervene.

A review of the literature

To better characterize the perpetrators of older adult homicide-suicide, we conducted a literature search of relevant terms. We identified 9 original research publications that examined homicide-suicide in older adults.

Bourget et al11 (2010) reviewed coroners’ charts of individuals killed by an older (age ≥65) spouse or family member from 1992 through 2007 in Quebec, Canada. They identified 19 cases of homicide-suicide, 17 (90%) of which were perpetrated by men. Perpetrators and victims were married (63%), in common-law relationships (16%), or separated/divorced (16%). A history of domestic violence was documented in 4 (21%) cases. The authors found that 13 of 15 perpetrators (87%) had “major depression” and 2 perpetrators had a psychotic disorder. Substance use at the time of the event was confirmed in 6 (32%) cases. Firearms and strangulation were the top methods used to carry out the homicide-suicide.11

Cheung et al12 (2016) conducted a review of coroners’ records of homicide-suicide cases among individuals age ≥65 in New Zealand from 2007 through 2012. In all 4 cases, the perpetrators were men, and their victims were predominantly female, live-in family members. Two cases involved men with a history of domestic violence who were undergoing significant changes in their home and social lives. Both men had a history suggestive of depression and used a firearm to carry out the homicide-suicide.12

Continue to: Cohen et al

Cohen et al13 (1998) conducted a review of coroners’ records from 1988 through 1994 in 2 regions in Florida. They found 48 intimate partner homicide-suicide cases among “old couples” (age ≥55). All were perpetrated by men. The authors identified sociocultural differences in risk factors between the 2 regions. In west-central Florida, perpetrators and victims were predominantly white and in a spousal relationship. Domestic violence was documented in <4% of cases. Approximately 55% of the couples were reported to be ill, and a substantial proportion were documented to be declining in health. One-quarter of the perpetrators and one-third of the victims had “pain and suffering.” More than one-third of perpetrators were reported to have “depression,” 15% were reported to have talked about suicide, and 4% had a history of a suicide attempt. Only 11% of perpetrators were described as abusing substances.

The authors noted several differences in cases in southeastern Florida. Approximately two-thirds of the couples were Hispanic, and 14% had a history of domestic violence. A minority of the couples were in a live-in relationship. Less than 15% of the perpetrators and victims were described as having a decline in health. Additionally, only 19% of perpetrators were reported to have “depression,” and none of the perpetrators had a documented history of attempted suicide or substance abuse. No information was provided regarding the methods used to carry out the homicide-suicide in the southeastern region.13 Financial stress was not a factor in either region.

Malphurs et al14 (2001) used the same database described in the Cohen et al13 study to compare 27 perpetrators of homicide-suicide to 36 age-matched suicide decedents in west central Florida. They found that homicide-suicide perpetrators were significantly less likely to have health problems and were 3 times more likely to be caregivers to their spouses. Approximately 52% of perpetrators had at least 1 documented psychiatric symptom (“depression” and/or substance abuse or other), but only 5% were seeking mental health services at the time of death.14

De Koning and Piette15 (2014) conducted a retrospective medicolegal chart review from 1935 to 2010 to identify homicide-suicide cases in West and East Flanders, Belgium. They found 19 cases of intimate partner homicide-suicide committed by offenders age ≥55 years. Ninety-five percent of the perpetrators were men who killed their female partners. In one-quarter of the cases, either the perpetrator or the victim had a health issue; 21% of the perpetrators were documented as having depression and 27% had alcohol intoxication at the time of death. A motive was documented in 14 out of 19 cases; “mercy killing” was determined as the motive in 6 (43%) cases and “amorous jealousy” in 5 cases (36%).15 Starting in the 1970s, firearms were the most prevalent method used to kill a partner.

Logan et al16 (2019) used data from the National Violent Death Reporting System between 2003 and 2015 to identify characteristics that differentiated male suicide decedents from male perpetrators of intimate partner homicide-suicide. They found that men age 50 to 64 years were 3 times more likely than men age 18 to 34 years to commit intimate partner homicide-suicide, and that men age ≥65 years were approximately 5 times more likely than men age 18 to 34 years to commit intimate partner homicide-suicide. The authors found that approximately 22% of all perpetrators had a documented history of physical domestic violence, and close to 17% had a prior interaction with the criminal justice system. Furthermore, one-third of perpetrators had relationship difficulties and were in the process of a breakup. Health issues were prevalent in 34% of the victims and 26% of the perpetrators. Perpetrator-caregiver burden was reported as a contributing factor for homicide-suicide in 16% of cases. In 27% of cases, multiple health-related contributing factors were mentioned.16

Continue to: Malphurs and Cohen

Malphurs and Cohen5 (2002) reviewed American newspapers from 1997 through 1999 and identified 673 homicide-suicide events, of which 152 (27%) were committed by individuals age ≥55 years. The victims and perpetrators (95% of which were men) were intimate partners in three-quarters of cases. In nearly one-third of cases, caregiving was a contributing factor for the homicide-suicide. A history of or a pending divorce was reported in nearly 14% of cases. Substance use history was rarely recorded. Firearms were used in 88% of the homicide-suicide cases.5

Malphurs and Cohen17 (2005) reviewed coroner records between 1998 and 1999 in Florida and compared 20 cases of intimate partner homicide-suicide involving perpetrators age ≥55 years with matched suicide decedents. They found that 60% of homicide-suicide perpetrators had documented health issues. The authors reported that a “recent change in health status” was more prevalent among perpetrators compared with decedents. Perpetrators were also more likely to be caregivers to their spouses. The authors found that 65% of perpetrators were reported to have a “depressed mood” and 15% of perpetrators had reportedly threatened suicide prior to the incident. However, none of the perpetrators tested positive for antidepressants as documented on post-mortem toxicology reports. Firearms were used in 100% of homicide-suicide cases.17

Salari3 (2007) reviewed multiple American media sources and published police reports between 1999 and 2005 to retrieve data about intimate partner homicide-suicide events in the United States. There were 225 events identified where the perpetrator and/or the victim were age ≥60 years. Ninety-six percent of the perpetrators were men and most homicide-suicide events were committed at the home. A history of domestic violence was reported in 14% of homicide-suicide cases. Thirteen percent of couples were separated or divorced. The perpetrator and/or victim had health issues in 124 (55%) events. Dementia was reported in 7.5% of cases, but overwhelmingly among the victims. Substance abuse was rarely mentioned as a contributing factor. In three-quarters of cases where a motive was described, the perpetrator was “suicidal”; however, a “suicide pact” was mentioned in only 4% of cases. Firearms were used in 87% of cases.3

Focus on common risk factors

The scarcity and heterogeneity of research regarding older adult homicide-suicide were major limitations to our review. Because most of the studies we identified had a small sample size and limited information regarding the mental health of victims and perpetrators, it would be an overreach to claim to have identified a typical profile of an older perpetrator of homicide-suicide. However, the literature has repeatedly identified several common characteristics of such perpetrators. They are significantly more likely to be men who use firearms to murder their intimate partners and then die by suicide in their home (Table3,5,11-17). Health issues afflicting 1 or both individuals in the couple appear to be a contributing factor, particularly when the perpetrator is in a caregiving role. Relational discord, with or without a history of domestic violence, increases the risk of homicide-suicide. Finally, older perpetrators are highly likely to be depressed and have suicidal ideations.

How COVID-19 affects these risks

Although it is too early to determine if there is a causal relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and an increase in homicide-suicide, the pandemic is likely to promote risk factors for these events, especially among older adults. Confinement measures put into place during the pandemic context have already been shown to increase rates of domestic violence18 and depression and anxiety among older individuals.7 Furthermore,

Continue to: Late-life psychiatric disorders

Late-life psychiatric disorders

Early recognition and effective treatment of late-life psychiatric disorders is crucial. Unfortunately, depression in geriatric patients is often underdiagnosed and undertreated.20 Older adults have more frequent contact with their primary care physicians, and rarely consult mental health professionals.21,22 Several models of integrated depression care within primary care settings have shown the positive impact of this collaborative approach in treating late-life depression and preventing suicide in older individuals.23 Additionally, because alcohol abuse is also a risk factor for domestic violence and breaking the law in this population,24,25 older adults should be screened for alcohol use disorders, and referred to treatment when necessary.

Take steps to keep patients safe

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, there are several steps clinicians need to keep in mind when interacting with older patients:

- Screen for depressive symptoms, suicidality, and alcohol and substance use disorders. Individuals who have tested positive for COVID-19 or who have been in contact with a carrier are a particularly vulnerable population.

- Screen for domestic violence and access to weapons at home.4 Any older adult who has a psychiatric disorder and/or suicide ideation should receive immediate intervention through a social worker that includes providing gun-risk education to other family members or contacting law-enforcement officials.26

- Refer patients with a suspected psychiatric disorder to specialized mental health clinicians. Telemental health services can provide rapid access to subspecialists, allowing patients to be treated from their homes.27 These services need to be promoted among older adults during this critical period and reimbursed by public and private insurance systems to ensure accessibility and affordability.28

- Create psychiatric inpatient units specifically designed for suicidal and/or homicidal patients with COVID-19.

Additionally, informing the public about these major health issues is crucial. The media can raise awareness about domestic violence and depression among older adults; however, this should be done responsibly and with accuracy to prevent the spread of misinformation, confusion, fear, and panic.29

Bottom Line

The mental health burden of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic has significantly impacted individuals who are older and most vulnerable. Reducing the incidence of homicide-suicide among older adults requires timely screening and interventions by primary care providers, mental health specialists, social workers, media, and governmental agencies.

Related Resources

- Saeed SA, Hebishi K. The psychiatric consequences of COVID-19: 8 studies. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(11):22-24,28-30,32-35.

- Schwab-Reese LM, Murfree L, Coppola EC, et al. Homicidesuicide across the lifespan: a mixed methods examination of factors contributing to older adult perpetration. Aging Ment Health. 2020;20:1-9.

On March 25, 2020, in Cambridge, United Kingdom, a 71-year-old man stabbed his 71-year-old wife before suffocating himself to death. The couple was reportedly anxious about the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic lockdown measures and were on the verge of running out of food and medicine.1

One week later, in Chicago, Illinois, a 54-year-old man shot and killed his female partner, age 54, before killing himself. The couple was tested for COVID-19 2 days earlier and the man believed they had contracted the virus; however, the test results for both of them had come back negative.2

Intimate partner homicide-suicide is the most dramatic domestic abuse outcome.3 Homicide-suicide is defined as “homicide committed by a person who subsequently commits suicide within one week of the homicide. In most cases the subsequent suicide occurs within a 24-hour period.”4 Approximately one-quarter of all homicide-suicides are committed by persons age ≥55 years.5,6 We believe that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the risk of homicide-suicide among older adults may be increased due to several factors, including:

- physical distancing and quarantine measures. Protocols established to slow the spread of the virus may be associated with increased rates of depression and anxiety7 and an increased risk of suicide among older adults8

- increased intimate partner violence9

- increased firearm ownership rates in the United States.10

In this article, we review studies that identified risk factors for homicide-suicide among older adults, discuss the impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had on these risks, and describe steps clinicians can take to intervene.

A review of the literature

To better characterize the perpetrators of older adult homicide-suicide, we conducted a literature search of relevant terms. We identified 9 original research publications that examined homicide-suicide in older adults.

Bourget et al11 (2010) reviewed coroners’ charts of individuals killed by an older (age ≥65) spouse or family member from 1992 through 2007 in Quebec, Canada. They identified 19 cases of homicide-suicide, 17 (90%) of which were perpetrated by men. Perpetrators and victims were married (63%), in common-law relationships (16%), or separated/divorced (16%). A history of domestic violence was documented in 4 (21%) cases. The authors found that 13 of 15 perpetrators (87%) had “major depression” and 2 perpetrators had a psychotic disorder. Substance use at the time of the event was confirmed in 6 (32%) cases. Firearms and strangulation were the top methods used to carry out the homicide-suicide.11

Cheung et al12 (2016) conducted a review of coroners’ records of homicide-suicide cases among individuals age ≥65 in New Zealand from 2007 through 2012. In all 4 cases, the perpetrators were men, and their victims were predominantly female, live-in family members. Two cases involved men with a history of domestic violence who were undergoing significant changes in their home and social lives. Both men had a history suggestive of depression and used a firearm to carry out the homicide-suicide.12

Continue to: Cohen et al

Cohen et al13 (1998) conducted a review of coroners’ records from 1988 through 1994 in 2 regions in Florida. They found 48 intimate partner homicide-suicide cases among “old couples” (age ≥55). All were perpetrated by men. The authors identified sociocultural differences in risk factors between the 2 regions. In west-central Florida, perpetrators and victims were predominantly white and in a spousal relationship. Domestic violence was documented in <4% of cases. Approximately 55% of the couples were reported to be ill, and a substantial proportion were documented to be declining in health. One-quarter of the perpetrators and one-third of the victims had “pain and suffering.” More than one-third of perpetrators were reported to have “depression,” 15% were reported to have talked about suicide, and 4% had a history of a suicide attempt. Only 11% of perpetrators were described as abusing substances.

The authors noted several differences in cases in southeastern Florida. Approximately two-thirds of the couples were Hispanic, and 14% had a history of domestic violence. A minority of the couples were in a live-in relationship. Less than 15% of the perpetrators and victims were described as having a decline in health. Additionally, only 19% of perpetrators were reported to have “depression,” and none of the perpetrators had a documented history of attempted suicide or substance abuse. No information was provided regarding the methods used to carry out the homicide-suicide in the southeastern region.13 Financial stress was not a factor in either region.

Malphurs et al14 (2001) used the same database described in the Cohen et al13 study to compare 27 perpetrators of homicide-suicide to 36 age-matched suicide decedents in west central Florida. They found that homicide-suicide perpetrators were significantly less likely to have health problems and were 3 times more likely to be caregivers to their spouses. Approximately 52% of perpetrators had at least 1 documented psychiatric symptom (“depression” and/or substance abuse or other), but only 5% were seeking mental health services at the time of death.14

De Koning and Piette15 (2014) conducted a retrospective medicolegal chart review from 1935 to 2010 to identify homicide-suicide cases in West and East Flanders, Belgium. They found 19 cases of intimate partner homicide-suicide committed by offenders age ≥55 years. Ninety-five percent of the perpetrators were men who killed their female partners. In one-quarter of the cases, either the perpetrator or the victim had a health issue; 21% of the perpetrators were documented as having depression and 27% had alcohol intoxication at the time of death. A motive was documented in 14 out of 19 cases; “mercy killing” was determined as the motive in 6 (43%) cases and “amorous jealousy” in 5 cases (36%).15 Starting in the 1970s, firearms were the most prevalent method used to kill a partner.

Logan et al16 (2019) used data from the National Violent Death Reporting System between 2003 and 2015 to identify characteristics that differentiated male suicide decedents from male perpetrators of intimate partner homicide-suicide. They found that men age 50 to 64 years were 3 times more likely than men age 18 to 34 years to commit intimate partner homicide-suicide, and that men age ≥65 years were approximately 5 times more likely than men age 18 to 34 years to commit intimate partner homicide-suicide. The authors found that approximately 22% of all perpetrators had a documented history of physical domestic violence, and close to 17% had a prior interaction with the criminal justice system. Furthermore, one-third of perpetrators had relationship difficulties and were in the process of a breakup. Health issues were prevalent in 34% of the victims and 26% of the perpetrators. Perpetrator-caregiver burden was reported as a contributing factor for homicide-suicide in 16% of cases. In 27% of cases, multiple health-related contributing factors were mentioned.16

Continue to: Malphurs and Cohen

Malphurs and Cohen5 (2002) reviewed American newspapers from 1997 through 1999 and identified 673 homicide-suicide events, of which 152 (27%) were committed by individuals age ≥55 years. The victims and perpetrators (95% of which were men) were intimate partners in three-quarters of cases. In nearly one-third of cases, caregiving was a contributing factor for the homicide-suicide. A history of or a pending divorce was reported in nearly 14% of cases. Substance use history was rarely recorded. Firearms were used in 88% of the homicide-suicide cases.5

Malphurs and Cohen17 (2005) reviewed coroner records between 1998 and 1999 in Florida and compared 20 cases of intimate partner homicide-suicide involving perpetrators age ≥55 years with matched suicide decedents. They found that 60% of homicide-suicide perpetrators had documented health issues. The authors reported that a “recent change in health status” was more prevalent among perpetrators compared with decedents. Perpetrators were also more likely to be caregivers to their spouses. The authors found that 65% of perpetrators were reported to have a “depressed mood” and 15% of perpetrators had reportedly threatened suicide prior to the incident. However, none of the perpetrators tested positive for antidepressants as documented on post-mortem toxicology reports. Firearms were used in 100% of homicide-suicide cases.17

Salari3 (2007) reviewed multiple American media sources and published police reports between 1999 and 2005 to retrieve data about intimate partner homicide-suicide events in the United States. There were 225 events identified where the perpetrator and/or the victim were age ≥60 years. Ninety-six percent of the perpetrators were men and most homicide-suicide events were committed at the home. A history of domestic violence was reported in 14% of homicide-suicide cases. Thirteen percent of couples were separated or divorced. The perpetrator and/or victim had health issues in 124 (55%) events. Dementia was reported in 7.5% of cases, but overwhelmingly among the victims. Substance abuse was rarely mentioned as a contributing factor. In three-quarters of cases where a motive was described, the perpetrator was “suicidal”; however, a “suicide pact” was mentioned in only 4% of cases. Firearms were used in 87% of cases.3

Focus on common risk factors

The scarcity and heterogeneity of research regarding older adult homicide-suicide were major limitations to our review. Because most of the studies we identified had a small sample size and limited information regarding the mental health of victims and perpetrators, it would be an overreach to claim to have identified a typical profile of an older perpetrator of homicide-suicide. However, the literature has repeatedly identified several common characteristics of such perpetrators. They are significantly more likely to be men who use firearms to murder their intimate partners and then die by suicide in their home (Table3,5,11-17). Health issues afflicting 1 or both individuals in the couple appear to be a contributing factor, particularly when the perpetrator is in a caregiving role. Relational discord, with or without a history of domestic violence, increases the risk of homicide-suicide. Finally, older perpetrators are highly likely to be depressed and have suicidal ideations.

How COVID-19 affects these risks

Although it is too early to determine if there is a causal relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and an increase in homicide-suicide, the pandemic is likely to promote risk factors for these events, especially among older adults. Confinement measures put into place during the pandemic context have already been shown to increase rates of domestic violence18 and depression and anxiety among older individuals.7 Furthermore,

Continue to: Late-life psychiatric disorders

Late-life psychiatric disorders

Early recognition and effective treatment of late-life psychiatric disorders is crucial. Unfortunately, depression in geriatric patients is often underdiagnosed and undertreated.20 Older adults have more frequent contact with their primary care physicians, and rarely consult mental health professionals.21,22 Several models of integrated depression care within primary care settings have shown the positive impact of this collaborative approach in treating late-life depression and preventing suicide in older individuals.23 Additionally, because alcohol abuse is also a risk factor for domestic violence and breaking the law in this population,24,25 older adults should be screened for alcohol use disorders, and referred to treatment when necessary.

Take steps to keep patients safe

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, there are several steps clinicians need to keep in mind when interacting with older patients:

- Screen for depressive symptoms, suicidality, and alcohol and substance use disorders. Individuals who have tested positive for COVID-19 or who have been in contact with a carrier are a particularly vulnerable population.

- Screen for domestic violence and access to weapons at home.4 Any older adult who has a psychiatric disorder and/or suicide ideation should receive immediate intervention through a social worker that includes providing gun-risk education to other family members or contacting law-enforcement officials.26

- Refer patients with a suspected psychiatric disorder to specialized mental health clinicians. Telemental health services can provide rapid access to subspecialists, allowing patients to be treated from their homes.27 These services need to be promoted among older adults during this critical period and reimbursed by public and private insurance systems to ensure accessibility and affordability.28

- Create psychiatric inpatient units specifically designed for suicidal and/or homicidal patients with COVID-19.

Additionally, informing the public about these major health issues is crucial. The media can raise awareness about domestic violence and depression among older adults; however, this should be done responsibly and with accuracy to prevent the spread of misinformation, confusion, fear, and panic.29

Bottom Line

The mental health burden of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic has significantly impacted individuals who are older and most vulnerable. Reducing the incidence of homicide-suicide among older adults requires timely screening and interventions by primary care providers, mental health specialists, social workers, media, and governmental agencies.

Related Resources

- Saeed SA, Hebishi K. The psychiatric consequences of COVID-19: 8 studies. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(11):22-24,28-30,32-35.

- Schwab-Reese LM, Murfree L, Coppola EC, et al. Homicidesuicide across the lifespan: a mixed methods examination of factors contributing to older adult perpetration. Aging Ment Health. 2020;20:1-9.

1. Christodoulou H. LOCKDOWN ‘MURDER-SUICIDE’ OAP, 71, ‘stabbed wife to death then killed himself as he worried about coping with coronavirus lockdown.’ The Sun. Updated April 4, 2020. Accessed December 22, 2020. https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/11327095/coronavirus-lockdown-murder-suicide-cambridge/

2. Farberov S. Illinois man, 54, shoots dead his wife then kills himself in murder-suicide because he feared they had coronavirus - but tests later show the couple were NOT ill. Updated April 6, 2020. Accessed December 22, 2020. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8191933/Man-kills-wife-feared-coronavirus.html

3. Salari S. Patterns of intimate partner homicide suicide in later life: strategies for prevention. Clin Interv Aging. 2007;2(3):441-452.

4. Kotzé C, Roos JL. Homicide–suicide: practical implications for risk reduction and support services at primary care level. South African Family Practice. 2019;61(4):165-169.

5. Malphurs JE, Cohen D. A newspaper surveillance study of homicide-suicide in the United States. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2002;23(2):142-148.

6. Eliason S. Murder-suicide: a review of the recent literature. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2009;37(3):371-376.

7. Armitage R, Nellums LB. COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):e256. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30061-X

8. Gunnell D, Appleby L, Arensman E, et al. Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7(6):468-471.

9. Gosangi B, Park H, Thomas R, et al. Exacerbation of physical intimate partner violence during COVID-19 pandemic. Radiology. 2021;298(1):E38-E45.

10. Mannix R, Lee LK, Fleegler EW. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and firearms in the United States: will an epidemic of suicide follow? Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(3):228-229.

11. Bourget D, Gagne P, Whitehurst L. Domestic homicide and homicide-suicide: the older offender. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2010;38(3):305-311.

12. Cheung G, Hatters Friedman S, Sundram F. Late-life homicide-suicide: a national case series in New Zealand. Psychogeriatrics. 2016;16(1):76-81.

13. Cohen D, Llorente M, Eisdorfer C. Homicide-suicide in older persons. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(3):390-396.

14. Malphurs JE, Eisdorfer C, Cohen D. A comparison of antecedents of homicide-suicide and suicide in older married men. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(1):49-57.

15. De Koning E, Piette MHA. A retrospective study of murder–suicide at the Forensic Institute of Ghent University, Belgium: 1935–2010. Med Sci Law. 2014;54(2):88-98.

16. Logan JE, Ertl A, Bossarte R. Correlates of intimate partner homicide among male suicide decedents with known intimate partner problems. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2019;49(6):1693-1706.

17. Malphurs JE, Cohen D. A statewide case-control study of spousal homicide-suicide in older persons. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(3):211-217.

18. Sanford A. ‘Horrifying surge in domestic violence’ against women amid coronavirus-lockdowns, UN chief warns. Euronews. Published June 4, 2020. Accessed December 22, 2020. https://www.euronews.com/2020/04/06/horrifying-surge-in-domestic-violence-against-women-amid-coronavirus-lockdowns-un-chief-w

19. Appel JM. Intimate partner homicide in elderly populations. In: Friedman SH, ed. Family murder: pathologies of love and hate. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019:131-142.

20. Hall CA, Reynolds-III CF. Late-life depression in the primary care setting: challenges, collaborative care, and prevention. Maturitas. 2014;79(2):147-152.

21. Unützer J. Diagnosis and treatment of older adults with depression in primary care. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52(3):285-292.

22. Byers AL, Arean PA, Yaffe K. Low use of mental health services among older Americans with mood and anxiety disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(1):66-72.

23. Bruce ML, Sirey JA. Integrated care for depression in older primary care patients. Can J Psychiatry. 2018;63(7):439-446.

24. Rao R, Roche A. Substance misuse in older people. BMJ. 2017;358:j3885. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3885

25. Ghossoub E, Khoury R. Prevalence and correlates of criminal behavior among the non-institutionalized elderly: results from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2018;31(4):211-222.

26. Slater MAG. Older adults at risk for suicide. In: Berkman B. Handbook of social work in health and aging. Oxford University Press; 2006:149-161.

27. Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1679-1681.

28. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. President Trump expands telehealth benefits for Medicare beneficiaries during COVID-19 outbreak. Published March 17, 2020. Accessed December 23, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/president-trump-expands-telehealth-benefits-medicare-beneficiaries-during-covid-19-outbreak

29. Mian A, Khan S. Coronavirus: the spread of misinformation. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):89.

1. Christodoulou H. LOCKDOWN ‘MURDER-SUICIDE’ OAP, 71, ‘stabbed wife to death then killed himself as he worried about coping with coronavirus lockdown.’ The Sun. Updated April 4, 2020. Accessed December 22, 2020. https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/11327095/coronavirus-lockdown-murder-suicide-cambridge/

2. Farberov S. Illinois man, 54, shoots dead his wife then kills himself in murder-suicide because he feared they had coronavirus - but tests later show the couple were NOT ill. Updated April 6, 2020. Accessed December 22, 2020. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8191933/Man-kills-wife-feared-coronavirus.html

3. Salari S. Patterns of intimate partner homicide suicide in later life: strategies for prevention. Clin Interv Aging. 2007;2(3):441-452.

4. Kotzé C, Roos JL. Homicide–suicide: practical implications for risk reduction and support services at primary care level. South African Family Practice. 2019;61(4):165-169.

5. Malphurs JE, Cohen D. A newspaper surveillance study of homicide-suicide in the United States. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2002;23(2):142-148.

6. Eliason S. Murder-suicide: a review of the recent literature. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2009;37(3):371-376.

7. Armitage R, Nellums LB. COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):e256. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30061-X

8. Gunnell D, Appleby L, Arensman E, et al. Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7(6):468-471.

9. Gosangi B, Park H, Thomas R, et al. Exacerbation of physical intimate partner violence during COVID-19 pandemic. Radiology. 2021;298(1):E38-E45.

10. Mannix R, Lee LK, Fleegler EW. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and firearms in the United States: will an epidemic of suicide follow? Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(3):228-229.

11. Bourget D, Gagne P, Whitehurst L. Domestic homicide and homicide-suicide: the older offender. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2010;38(3):305-311.

12. Cheung G, Hatters Friedman S, Sundram F. Late-life homicide-suicide: a national case series in New Zealand. Psychogeriatrics. 2016;16(1):76-81.

13. Cohen D, Llorente M, Eisdorfer C. Homicide-suicide in older persons. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(3):390-396.

14. Malphurs JE, Eisdorfer C, Cohen D. A comparison of antecedents of homicide-suicide and suicide in older married men. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(1):49-57.

15. De Koning E, Piette MHA. A retrospective study of murder–suicide at the Forensic Institute of Ghent University, Belgium: 1935–2010. Med Sci Law. 2014;54(2):88-98.

16. Logan JE, Ertl A, Bossarte R. Correlates of intimate partner homicide among male suicide decedents with known intimate partner problems. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2019;49(6):1693-1706.

17. Malphurs JE, Cohen D. A statewide case-control study of spousal homicide-suicide in older persons. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(3):211-217.

18. Sanford A. ‘Horrifying surge in domestic violence’ against women amid coronavirus-lockdowns, UN chief warns. Euronews. Published June 4, 2020. Accessed December 22, 2020. https://www.euronews.com/2020/04/06/horrifying-surge-in-domestic-violence-against-women-amid-coronavirus-lockdowns-un-chief-w

19. Appel JM. Intimate partner homicide in elderly populations. In: Friedman SH, ed. Family murder: pathologies of love and hate. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019:131-142.

20. Hall CA, Reynolds-III CF. Late-life depression in the primary care setting: challenges, collaborative care, and prevention. Maturitas. 2014;79(2):147-152.

21. Unützer J. Diagnosis and treatment of older adults with depression in primary care. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52(3):285-292.

22. Byers AL, Arean PA, Yaffe K. Low use of mental health services among older Americans with mood and anxiety disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(1):66-72.

23. Bruce ML, Sirey JA. Integrated care for depression in older primary care patients. Can J Psychiatry. 2018;63(7):439-446.

24. Rao R, Roche A. Substance misuse in older people. BMJ. 2017;358:j3885. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3885

25. Ghossoub E, Khoury R. Prevalence and correlates of criminal behavior among the non-institutionalized elderly: results from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2018;31(4):211-222.

26. Slater MAG. Older adults at risk for suicide. In: Berkman B. Handbook of social work in health and aging. Oxford University Press; 2006:149-161.

27. Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1679-1681.

28. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. President Trump expands telehealth benefits for Medicare beneficiaries during COVID-19 outbreak. Published March 17, 2020. Accessed December 23, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/president-trump-expands-telehealth-benefits-medicare-beneficiaries-during-covid-19-outbreak

29. Mian A, Khan S. Coronavirus: the spread of misinformation. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):89.