User login

Food Insecurity Among Veterans: Resources to Screen and Intervene

Nearly 1 in 8 households—and 1 in 6 households with children—experienced food insecurity in 2017, defined as limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods.1 Food insecurity is often even more pronounced among households with individuals with acute or chronic medical conditions.2-6 Moreover, food insecurity is independently associated with a range of adverse health outcomes, including poorer control of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, depression and other major psychiatric disorders, HIV, and chronic lung and kidney disease, as well as poorer overall health status.7-14 Food insecurity also has been associated with increased health care costs and acute care utilization as well as increased probability of delayed or missed care.15-19

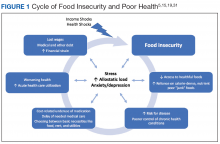

The relationship between food insecurity and poor health outcomes is a complex and often cyclic phenomenon (Figure 1). Poor nutritional status is fueled by limited access to healthful foods as well as increased reliance on calorie-dense and nutrient-poor “junk” foods, which are less expensive and often more readily available in low-income neighborhoods.5,20-24 These compensatory dietary patterns place individuals at higher risk for developing cardiometabolic conditions and for poor control of these conditions.5,8,9,12,25,26 Additionally, the physiological and psychological stressors of food insecurity may precipitate depression and anxiety or worsen existing mental health conditions, resulting in feelings of overwhelm and decreased self-management capacity.5,8,27-31 Food insecurity has further been associated with poor sleep, declines in cognitive function, and increased falls, particularly among the frail and elderly.32-34

Individuals experiencing food insecurity often report having to make trade-offs between food and other necessities, such as paying rent or utilities. Additional strategies to stretch limited resources include cost-related underuse of medication and delays in needed medical care.4,17,31,35 In a nationally representative survey among adults with at least 1 chronic medical condition, 1 in 3 reported having to choose between food and medicine; 11% were unable to afford either.3 Furthermore, the inability to reliably adhere to medication regimens that need to be taken with food can result in potentially life-threatening hypoglycemia (as can lack of food regardless of medication use).5,26,36 In addition to the more obvious risks of glucose-lowering medications, such as insulin and long-acting sulfonylureas in patients experiencing food insecurity, many drugs commonly used among nondiabetic adults such as ACE-inhibitors, β blockers, quinolones, and salicylates can also precipitate hypoglycemia, and food insecurity has been associated with experiences of hypoglycemia even among individuals without diabetes mellitus.32,37 In one study the risk for hospital admissions for hypoglycemia among low-income populations increased by 27% at the end of the month when food budgets were more likely to be exhausted.38 Worsening health status and increased emergency department visits and hospitalizations may then result in lost wages and mounting medical bills, contributing to further financial strain and worsening food insecurity.

Prevalence and Importance of Food Insecurity Among US Veterans

Nearly 1.5 million veterans in the US are living below the federal poverty level (FPL).39 An additional 2.4 million veterans are living paycheck to paycheck at < 200% of the FPL.40 Veterans living in poverty are at even higher risk than nonveterans for food insecurity, homelessness, and other material hardship.41

Estimates of food insecurity among veterans vary widely, ranging from 6% to 24%—nearly twice that of the general US population.8,42-45 Higher rates of food insecurity have been reported among certain high-risk subgroups, including veterans who served in Iraq and Afghanistan (27%), female veterans (28%), homeless and formerly homeless veterans (49%), and veterans with serious mental illness (35%).6,32,43,46 Additional risk factors for food insecurity specific to veteran populations include younger age, having recently left active-duty military service, and lower final military paygrade.42,45-47 As in the general population, veteran food insecurity is associated with a range of adverse health outcomes, including poorer overall health status as well as increased probability of delayed or missed care.6,8,32,42-44,46

Even among veterans enrolled in federal food assistance programs, many still struggle to afford nutritionally adequate foods. As one example, in a study of mostly male homeless and formerly homeless veterans, O’Toole and colleagues found that nearly half of those reporting food insecurity were already receiving federal food assistance benefits, and 22% relied on emergency food resources.32 Of households served by Feeding America food pantries and meal programs, 20% have a member who has served in the US military.48

Federal Programs To Address Food Insecurity

There are several important federal food assistance programs designed to help alleviate food insecurity. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly the Food Stamp program) is the largest federal food assistance program and provides low-income Americans with cash benefits to purchase food. SNAP has been shown to substantially reduce food insecurity.7,49 The program also is associated with significant decreases in cost-related medication nonadherence as well as reductions in health care costs and both acute care and nursing home utilization.16,50-54 Although nearly 1.4 million veterans live in SNAP-enrolled households, 59% of eligible veterans are not enrolled.43,55 Closing this SNAP eligibility-enrollment gap, has been a focus of recent efforts to improve long-term food security among veterans. There also are several federal food assistance programs for households with children, including the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) and school meals programs. Among federal nutrition programs for seniors, the Older American’s Act contains designated funding to support nutrition services for older adults, including congregate meal programs in community settings like senior centers, places of worship, and housing communities, and home-delivered meals through programs like Meals on Wheels.56

VHA Response to Food Insecurity

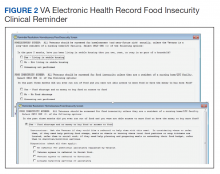

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the country’s largest integrated, federally funded health care system.57 In November 2015, congressional briefings on veteran food insecurity organized by the national non-profit organization MAZON: A Jewish Response to Hunger and hosted with bipartisan support were provided to the US House and Senate. As a result of these briefings, VHA chartered the national Ensuring Veteran Food Security Workgroup with a mandate to partner with governmental and nonprofit agencies to “focus on the issue of food insecurity, the identification of veterans at risk, the needed training of VHA staff and the coordination of resources and initiatives to support the veterans for whom we care.” Building off a pilot in US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Homeless Patient Aligned Care Teams (H-PACTs),32 VHA subsequently integrated a single-item food insecurity screening tool into the VA electronic health record (EHR) clinical reminder system (Figure 2). The clinical reminder, which was rolled out across VA medical centers nationally in October 2017, provides an alert to screen all noninstitutionalized veterans for food insecurity. To date, nearly 5 million veterans have been screened. When a veteran endorses food insecurity based on the initial screening question, a prompt appears to offer the veteran a referral to a social worker and/or dietitian. Positive screening results also should be communicated to the patient’s primary care provider. Depending on site-specific clinical flow, the reminders are typically completed in the outpatient setting either by nurses or medical assistants during intake or by providers as part of the clinical visit. However, any member of the health care team can complete the clinical reminder at any time. As of September 2019, approximately 74,000 veterans have been identified as food insecure.58

Addressing Food Insecurity

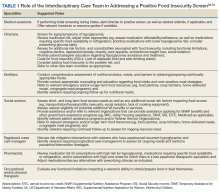

VHA has been a recognized leader in addressing homelessness and other social determinants of health through its integrated care and PACT delivery models.59-61 The food insecurity clinical reminder was designed to facilitate a tailored, interdisciplinary approach to identify and address food insecurity. Interdisciplinary care team members—including medical assistants, clinicians, social workers, registered dietitians, nurse care managers, occupational or physical therapists, and pharmacists—are uniquely positioned to identify veterans impacted by food insecurity, assess for associated clinical and/or social risk factors, and offer appropriate medical and nutrition interventions and resource referrals.

This interdisciplinary team-based model is essential given the range of potential drivers underlying veteran experiences of food insecurity and subsequent health outcomes. It is critically important for clinicians to review the medication list with veterans screening positive for food insecurity to assess for risk of hypoglycemia and/or cost-related nonadherence, make any necessary adjustments to therapeutic regimens, and assess for additional risk factors associated with food insecurity. Examples of tailored nutrition counseling that clinical dietitians may provide include meal preparation strategies for veterans who only have access to a microwave or hotplate, or recommendations for how veterans on medically restricted diets can best navigate food selection at soup kitchens or food pantries. Resource referrals provided by social workers or other care team members may include both emergency food resources to address immediate shortages (eg, food pantries, soup kitchens, or vouchers for free lunch) as well as resources focused on improving longer term food security (eg, federal food assistance programs or home delivered meal programs). Importantly, although providing a list of food resources may be helpful for some patients, such lists are often insufficient.62,63 Many patients require active assistance with program enrollment either onsite the day of their clinic visit or through connection with a partnering community-based organization that can, in turn, identify appropriate resources and facilitate program enrollment.63,64 Planned follow-up is also crucial to determine whether referrals are successful and to assess for ongoing need. Proposed roles for interdisciplinary care team members in addressing a positive food insecurity screen are outlined in Table 1.

VHA-Community Partnerships

In addition to services offered within VA, public and private sector partnerships can greatly enhance the range of resources available to food insecure veterans. Several VA facilities have developed formal community partnerships, such as the Veterans Pantry Pilot (VPP) program, a national partnership between Feeding America food banks and VA medical centers to establish onsite or mobile food pantries. There are currently 17 active Feeding America VPP sites, with a number of additional sites under development. Several of the VPP sites also include other “wraparound services,” such as SNAP application assistance.65,66

State Veterans Affairs offices67 and Veterans Service Organizations (VSOs)68 also can serve as valuable partners for connecting veterans with needed resources. VSOs offer a range of services, including assistancewith benefit claims, employment and housing assistance, emergency food assistance, and transportation to medical appointments. Some VSOs also have established local affiliations with Meals on Wheels focused on veteran outreach and providing hot meals for low-income, homebound, and disabled veterans.

Additional Resources

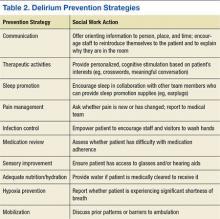

Although resources vary by regional setting, several key governmental and community-based food assistance programs are summarized in Table 2. Local community partners and online/phone-based directories, such as United Way’s 2-1-1 can help identify additional local resources. For older adults and individuals with disabilities, local Aging and Disability Resources Centers can provide information and assistance connecting to needed resources.69 Finally, there are a number of online resources available for clinicians interested in learning more about the impact of food insecurity on health and tools to use in the clinical setting (Table 3).

Conclusion

The VA has recognized food insecurity as a critical concern for the well-being of our nation’s veterans. Use of the EHR clinical reminder represents a crucial first step toward increasing provider awareness about veteran food insecurity and improving clinical efforts to address food insecurity once identified. Through the reminder, health care teams can connect veterans to needed resources and create both the individual and population-level data necessary to inform VHA and community efforts to address veteran food insecurity. Clinical reminder data are currently being used for local quality improvement efforts and have established the need nationally for formalized partnerships between VHA Social Work Services and Nutrition and Food Services to connect veterans with food and provide them with strategies to best use available food resources.

Moving forward, the Ensuring Veteran Food Security Workgroup continues to work with agencies and organizations across the country to improve food insecure veterans’ access to needed services. In addition to existing VA partnerships with Feeding America for the VPP, memorandums of understanding are currently underway to formalize partnerships with both the Food Research and Action Center (FRAC) and MAZON. Additional research is needed both to formally validate the current food insecurity clinical reminder screening question and to identify best practices and potential models for how to most effectively use VHA-community partnerships to address the unique needs of the veteran population.

Ensuring the food security of our nation’s veterans is essential to VA’s commitment to providing integrated, veteran-centered, whole person care. Toward that goal, VA health care teams are urged to use the clinical reminder and help connect food insecure veterans with relevant resources both within and outside of the VA health care system.

1. Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, Singh A. Household food security in the United States in 2017. http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=90022. Published September 2018. Accessed December 9, 2019.

2. Berkowitz SA, Meigs JB, DeWalt D, et al. Material need insecurities, control of diabetes mellitus, and use of health care resources: results of the Measuring Economic Insecurity in Diabetes study. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):257-265.

3. Berkowitz SA, Seligman HK, Choudhry NK. Treat or eat: food insecurity, cost-related medication underuse, and unmet needs. Am J Med. 2014;127(4):303-310.e3.

4. Lyles CR, Seligman HK, Parker MM, et al. Financial strain and medication adherence among diabetes patients in an integrated health care delivery system: The Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Health Serv Res. 2016;51(2):610-624.

5. Seligman HK, Schillinger D. Hunger and socioeconomic disparities in chronic disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):6-9.

6. Narain K, Bean-Mayberry B, Washington DL, Canelo IA, Darling JE, Yano EM. Access to care and health outcomes among women veterans using veterans administration health care: association with food insufficiency. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28(3):267-272.

7. Gundersen C, Ziliak JP. Food insecurity and health outcomes. Health Aff. 2015;34(11):1830-1839.

8. Wang EA, McGinnis KA, Goulet J, et al; Veterans Aging Cohort Study Project Team. Food insecurity and health: data from the Veterans Aging Cohort Study. Public Health Rep. 2015;130(3):261-268.

9. Berkowitz SA, Berkowitz TSZ, Meigs JB, Wexler DJ. Trends in food insecurity for adults with cardiometabolic disease in the United States: 2005-2012. PloS One. 2017;12(6):e0179172.

10. Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. 2010;140(2):304-310.

11. Berkowitz SA, Baggett TP, Wexler DJ, Huskey KW, Wee CC. Food insecurity and metabolic control among U.S. adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(10):3093-3099.

12. Seligman HK, Jacobs EA, López A, Tschann J, Fernandez A. Food insecurity and glycemic control among low-income patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(2):233-238.

13. Banerjee T, Crews DC, Wesson DE, et al; CDC CKD Surveillance Team. Food insecurity, CKD, and subsequent ESRD in US adults. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70(1):38-47.

14. Bruening M, Dinour LM, Chavez JBR. Food insecurity and emotional health in the USA: a systematic narrative review of longitudinal research. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(17):3200-3208.

15. Berkowitz SA, Basu S, Meigs JB, Seligman HK. Food insecurity and health care expenditures in the United States, 2011-2013. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(3):1600-1620.

16. Berkowitz SA, Seligman HK, Basu S. Impact of food insecurity and SNAP participation on healthcare utilization and expenditures. http://www.ukcpr.org/research/discussion-papers. Published 2017. Accessed December 9, 2019.

17. Kushel MB, Gupta R, Gee L, Haas JS. Housing instability and food insecurity as barriers to health care among low-income Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(1):71-77.

18. Garcia SP, Haddix A, Barnett K. Incremental health care costs associated with food insecurity and chronic conditions among older adults. Chronic Dis. 2018;15:180058.

19. Berkowitz SA, Seligman HK, Meigs JB, Basu S. Food insecurity, healthcare utilization, and high cost: a longitudinal cohort study. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(9):399-404.

20. Larson NI, Story MT, Nelson MC. Neighborhood environments: disparities in access to healthy foods in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(1):74-81.

21. Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: a systematic review and analysis. Nutr Rev. 2015;73(10):643-660.

22. Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Does social class predict diet quality? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(5):1107-1117.

23. Drewnowski A. The cost of US foods as related to their nutritive value. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(5):1181-1188.

24. Lucan SC, Maroko AR, Seitchik JL, Yoon DH, Sperry LE, Schechter CB. Unexpected neighborhood sources of food and drink: implications for research and community health. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(2):e29-e38.

25. Castillo DC, Ramsey NL, Yu SS, Ricks M, Courville AB, Sumner AE. Inconsistent access to food and cardiometabolic disease: the effect of food insecurity. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2012;6(3):245-250.

26. Seligman HK, Davis TC, Schillinger D, Wolf MS. Food insecurity is associated with hypoglycemia and poor diabetes self-management in a low-income sample with diabetes. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(4):1227-1233.

27. Siefert K, Heflin CM, Corcoran ME, Williams DR. Food insufficiency and physical and mental health in a longitudinal survey of welfare recipients. J Health Soc Behav. 2004;45(2):171-186.

28. Mangurian C, Sreshta N, Seligman H. Food insecurity among adults with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(9):931-932.

29. Melchior M, Caspi A, Howard LM, et al. Mental health context of food insecurity: a representative cohort of families with young children. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4):e564-e572.

30. Brostow DP, Gunzburger E, Abbate LM, Brenner LA, Thomas KS. Mental illness, not obesity status, is associated with food insecurity among the elderly in the health and retirement study. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;38(2):149-172.

31. Higashi RT, Craddock Lee SJ, Pezzia C, Quirk L, Leonard T, Pruitt SL. Family and social context contributes to the interplay of economic insecurity, food insecurity, and health. Ann Anthropol Pract. 2017;41(2):67-77.

32. O’Toole TP, Roberts CB, Johnson EE. Screening for food insecurity in six Veterans Administration clinics for the homeless, June-December 2015. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:160375.

33. Feil DG, Pogach LM. Cognitive impairment is a major risk factor for serious hypoglycaemia; public health intervention is warranted. Evid Based Med. 2014;19(2):77.

34. Frith E, Loprinzi PD. Food insecurity and cognitive function in older adults: Brief report. Clin Nutr. 2018;37(5):1765-1768.

35. Herman D, Afulani P, Coleman-Jensen A, Harrison GG. Food insecurity and cost-related medication underuse among nonelderly adults in a nationally representative sample. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10):e48-e59.

36. Tseng C-L, Soroka O, Maney M, Aron DC, Pogach LM. Assessing potential glycemic overtreatment in persons at hypoglycemic risk. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(2):259-268.

37. Vue MH, Setter SM. Drug-induced glucose alterations part 1: drug-induced hypoglycemia. Diabetes Spectr. 2011;24(3):171-177.

38. Seligman HK, Bolger AF, Guzman D, López A, Bibbins-Domingo K. Exhaustion of food budgets at month’s end and hospital admissions for hypoglycemia. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(1):116-123.

39. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Veteran poverty trends. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/specialreports/veteran_poverty_trends.pdf. Published May 2015. Accessed December 9, 2019.

40. Robbins KG, Ravi A. Veterans living paycheck to paycheck are under threat during budget debates. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/poverty/news/2017/09/19/439023/veterans-living-paycheck-paycheck-threat-budget-debates. Published September 19, 2017. Accessed December 9, 2019.

41. Wilmoth JM, London AS, Heflin CM. Economic well-being among older-adult households: variation by veteran and disability status. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2015;58(4):399-419.

42. Brostow DP, Gunzburger E, Thomas KS. Food insecurity among veterans: findings from the health and retirement study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21(10):1358-1364.

43. Pooler J, Mian P, Srinivasan M, Miller Z. Veterans and food insecurity. https://www.impaqint.com/sites/default/files/issue-briefs/VeteransFoodInsecurity_IssueBrief_V1.3.pdf. Published November 2018. Accessed December 9, 2019.

44. Schure MB, Katon JG, Wong E, Liu C-F. Food and housing insecurity and health status among U.S. adults with and without prior military service. SSM Popul Health. 2016;29(2):244-248.

45. Miller DP, Larson MJ, Byrne T, DeVoe E. Food insecurity in veteran households: findings from nationally representative data. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(10):1731-1740.

46. Widome R, Jensen A, Bangerter A, Fu SS. Food insecurity among veterans of the US wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(5):844-849.

47. London AS, Heflin CM. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) use among active-duty military personnel, veterans, and reservists. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2015;34(6):805-826.

48. Weinfield NS, Mills G, Borger C, et al. Hunger in America 2014. Natl rep prepared for Feeding America. https://www.feedingamerica.org/research/hunger-in-america. Published 2014. Accessed December 9, 2019.

49. Mabli J, Ohls J, Dragoset L, Castner L, Santos B. Measuring the Effect of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Participation on Food Security. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service; 2013.

50. Srinivasan M, Pooler JA. Cost-related medication nonadherence for older adults participating in SNAP, 2013–2015. Am J Public Health. 2017;108(2):224-230.

51. Heflin C, Hodges L, Mueser P. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Progam benefits and emergency room visits for hypoglycaemia. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(7):1314-1321.

52. Samuel LJ, Szanton SL, Cahill R, et al. Does the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program affect hospital utilization among older adults? The case of Maryland. Popul Health Manag. 2018;21(2):88-95.

53. Szanton SL, Samuel LJ, Cahill R, et al. Food assistance is associated with decreased nursing home admissions for Maryland’s dually eligible older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):162.

54. Carlson S, Keith-Jennings B. SNAP is linked with improved nutritional outcomes and lower health care costs. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/snap-is-linked-with-improved-nutritional-outcomes-and-lower-health-care. Published January 17, 2018. Accessed December 10, 2019.

55. Keith-Jennings B, Cai L. SNAP helps almost 1.4 million low-income veterans, including thousands in every state. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/snap-helps-almost-14-million-low-income-veterans-including-thousands-in. Updated November 8, 2018. Accessed December 10, 2019.

56. US Department of Health and Human Services. Older Americans Act nutrition programs. https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/news%202017-03/OAA-Nutrition_Programs_Fact_Sheet.pdf. Accessed December 10, 2019.

57. US Department of Veterans Affairs. About VHA. https://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp. Accessed December 10, 2019.

58. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA Corporate Data Warehouse.

59. Yano EM, Bair MJ, Carrasquillo O, Krein SL, Rubenstein LV. Patient aligned care teams (PACT): VA’s journey to implement patient-centered medical homes. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(suppl 2):S547-s549.

60. O’Toole TP, Pape L. Innovative efforts to address homelessness among veterans. N C Med J. 2015;76(5):311-314.

61. O’Toole TP, Johnson EE, Aiello R, Kane V, Pape L. Tailoring care to vulnerable populations by incorporating social determinants of health: the Veterans Health Administration’s “Homeless Patient Aligned Care Team” Program. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:150567.

62. Marpadga S, Fernandez A, Leung J, Tang A, Seligman H, Murphy EJ. Challenges and successes with food resource referrals for food-insecure patients with diabetes. Perm J. 2019;23.

63. Stenmark SH, Steiner JF, Marpadga S, Debor M, Underhill K, Seligman H. Lessons learned from implementation of the food insecurity screening and referral program at Kaiser Permanente Colorado. Perm J. 2018;22.

64. Martel ML, Klein LR, Hager KA, Cutts DB. Emergency department experience with novel electronic medical record order for referral to food resources. West J Emerg Med. 2018;19(2):232-237.

65. Going C, Cohen AJ, Bares M, Christensen M. Interdisciplinary approaches to addressing the food insecure veteran. Veterans Health Administration Employee Education System webinar; October 30, 2018.

66. Feeding America Announces New Partnership With U.S. Department Of Veterans Affairs. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/feeding-america-announces-new-partnership-with-us-department-of-veterans-affairs-300481891.html. Published June 29, 2017. Accessed December 10, 2019.

67. US Department of Veterans Affairs. State Veterans Affairs offices. https://www.va.gov/statedva.htm. Updated March 20, 2019. Accessed December 10, 2019.

68. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Directory of veterans service organizations. https://www.va.gov/vso. Updated December 24, 2013. Accessed December 10, 2019.

69. ACL Administration for Community Living. Aging and disability resource centers. https://acl.gov/programs/aging-and-disability-networks/aging-and-disability-resource-centers. Updated December 13, 2017. Accessed December 10, 2019.

70. Nutrition and Obesity Policy Research and Evaluation Network (NOPREN). Clinical screening algorithms. https://nopren.org/resource/download-food-insecurity-screening-and-referral-algorithms-for-adults-patients-living-with-diabetes-and-pediatric-patients. Accessed December 10, 2019.

Nearly 1 in 8 households—and 1 in 6 households with children—experienced food insecurity in 2017, defined as limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods.1 Food insecurity is often even more pronounced among households with individuals with acute or chronic medical conditions.2-6 Moreover, food insecurity is independently associated with a range of adverse health outcomes, including poorer control of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, depression and other major psychiatric disorders, HIV, and chronic lung and kidney disease, as well as poorer overall health status.7-14 Food insecurity also has been associated with increased health care costs and acute care utilization as well as increased probability of delayed or missed care.15-19

The relationship between food insecurity and poor health outcomes is a complex and often cyclic phenomenon (Figure 1). Poor nutritional status is fueled by limited access to healthful foods as well as increased reliance on calorie-dense and nutrient-poor “junk” foods, which are less expensive and often more readily available in low-income neighborhoods.5,20-24 These compensatory dietary patterns place individuals at higher risk for developing cardiometabolic conditions and for poor control of these conditions.5,8,9,12,25,26 Additionally, the physiological and psychological stressors of food insecurity may precipitate depression and anxiety or worsen existing mental health conditions, resulting in feelings of overwhelm and decreased self-management capacity.5,8,27-31 Food insecurity has further been associated with poor sleep, declines in cognitive function, and increased falls, particularly among the frail and elderly.32-34

Individuals experiencing food insecurity often report having to make trade-offs between food and other necessities, such as paying rent or utilities. Additional strategies to stretch limited resources include cost-related underuse of medication and delays in needed medical care.4,17,31,35 In a nationally representative survey among adults with at least 1 chronic medical condition, 1 in 3 reported having to choose between food and medicine; 11% were unable to afford either.3 Furthermore, the inability to reliably adhere to medication regimens that need to be taken with food can result in potentially life-threatening hypoglycemia (as can lack of food regardless of medication use).5,26,36 In addition to the more obvious risks of glucose-lowering medications, such as insulin and long-acting sulfonylureas in patients experiencing food insecurity, many drugs commonly used among nondiabetic adults such as ACE-inhibitors, β blockers, quinolones, and salicylates can also precipitate hypoglycemia, and food insecurity has been associated with experiences of hypoglycemia even among individuals without diabetes mellitus.32,37 In one study the risk for hospital admissions for hypoglycemia among low-income populations increased by 27% at the end of the month when food budgets were more likely to be exhausted.38 Worsening health status and increased emergency department visits and hospitalizations may then result in lost wages and mounting medical bills, contributing to further financial strain and worsening food insecurity.

Prevalence and Importance of Food Insecurity Among US Veterans

Nearly 1.5 million veterans in the US are living below the federal poverty level (FPL).39 An additional 2.4 million veterans are living paycheck to paycheck at < 200% of the FPL.40 Veterans living in poverty are at even higher risk than nonveterans for food insecurity, homelessness, and other material hardship.41

Estimates of food insecurity among veterans vary widely, ranging from 6% to 24%—nearly twice that of the general US population.8,42-45 Higher rates of food insecurity have been reported among certain high-risk subgroups, including veterans who served in Iraq and Afghanistan (27%), female veterans (28%), homeless and formerly homeless veterans (49%), and veterans with serious mental illness (35%).6,32,43,46 Additional risk factors for food insecurity specific to veteran populations include younger age, having recently left active-duty military service, and lower final military paygrade.42,45-47 As in the general population, veteran food insecurity is associated with a range of adverse health outcomes, including poorer overall health status as well as increased probability of delayed or missed care.6,8,32,42-44,46

Even among veterans enrolled in federal food assistance programs, many still struggle to afford nutritionally adequate foods. As one example, in a study of mostly male homeless and formerly homeless veterans, O’Toole and colleagues found that nearly half of those reporting food insecurity were already receiving federal food assistance benefits, and 22% relied on emergency food resources.32 Of households served by Feeding America food pantries and meal programs, 20% have a member who has served in the US military.48

Federal Programs To Address Food Insecurity

There are several important federal food assistance programs designed to help alleviate food insecurity. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly the Food Stamp program) is the largest federal food assistance program and provides low-income Americans with cash benefits to purchase food. SNAP has been shown to substantially reduce food insecurity.7,49 The program also is associated with significant decreases in cost-related medication nonadherence as well as reductions in health care costs and both acute care and nursing home utilization.16,50-54 Although nearly 1.4 million veterans live in SNAP-enrolled households, 59% of eligible veterans are not enrolled.43,55 Closing this SNAP eligibility-enrollment gap, has been a focus of recent efforts to improve long-term food security among veterans. There also are several federal food assistance programs for households with children, including the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) and school meals programs. Among federal nutrition programs for seniors, the Older American’s Act contains designated funding to support nutrition services for older adults, including congregate meal programs in community settings like senior centers, places of worship, and housing communities, and home-delivered meals through programs like Meals on Wheels.56

VHA Response to Food Insecurity

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the country’s largest integrated, federally funded health care system.57 In November 2015, congressional briefings on veteran food insecurity organized by the national non-profit organization MAZON: A Jewish Response to Hunger and hosted with bipartisan support were provided to the US House and Senate. As a result of these briefings, VHA chartered the national Ensuring Veteran Food Security Workgroup with a mandate to partner with governmental and nonprofit agencies to “focus on the issue of food insecurity, the identification of veterans at risk, the needed training of VHA staff and the coordination of resources and initiatives to support the veterans for whom we care.” Building off a pilot in US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Homeless Patient Aligned Care Teams (H-PACTs),32 VHA subsequently integrated a single-item food insecurity screening tool into the VA electronic health record (EHR) clinical reminder system (Figure 2). The clinical reminder, which was rolled out across VA medical centers nationally in October 2017, provides an alert to screen all noninstitutionalized veterans for food insecurity. To date, nearly 5 million veterans have been screened. When a veteran endorses food insecurity based on the initial screening question, a prompt appears to offer the veteran a referral to a social worker and/or dietitian. Positive screening results also should be communicated to the patient’s primary care provider. Depending on site-specific clinical flow, the reminders are typically completed in the outpatient setting either by nurses or medical assistants during intake or by providers as part of the clinical visit. However, any member of the health care team can complete the clinical reminder at any time. As of September 2019, approximately 74,000 veterans have been identified as food insecure.58

Addressing Food Insecurity

VHA has been a recognized leader in addressing homelessness and other social determinants of health through its integrated care and PACT delivery models.59-61 The food insecurity clinical reminder was designed to facilitate a tailored, interdisciplinary approach to identify and address food insecurity. Interdisciplinary care team members—including medical assistants, clinicians, social workers, registered dietitians, nurse care managers, occupational or physical therapists, and pharmacists—are uniquely positioned to identify veterans impacted by food insecurity, assess for associated clinical and/or social risk factors, and offer appropriate medical and nutrition interventions and resource referrals.

This interdisciplinary team-based model is essential given the range of potential drivers underlying veteran experiences of food insecurity and subsequent health outcomes. It is critically important for clinicians to review the medication list with veterans screening positive for food insecurity to assess for risk of hypoglycemia and/or cost-related nonadherence, make any necessary adjustments to therapeutic regimens, and assess for additional risk factors associated with food insecurity. Examples of tailored nutrition counseling that clinical dietitians may provide include meal preparation strategies for veterans who only have access to a microwave or hotplate, or recommendations for how veterans on medically restricted diets can best navigate food selection at soup kitchens or food pantries. Resource referrals provided by social workers or other care team members may include both emergency food resources to address immediate shortages (eg, food pantries, soup kitchens, or vouchers for free lunch) as well as resources focused on improving longer term food security (eg, federal food assistance programs or home delivered meal programs). Importantly, although providing a list of food resources may be helpful for some patients, such lists are often insufficient.62,63 Many patients require active assistance with program enrollment either onsite the day of their clinic visit or through connection with a partnering community-based organization that can, in turn, identify appropriate resources and facilitate program enrollment.63,64 Planned follow-up is also crucial to determine whether referrals are successful and to assess for ongoing need. Proposed roles for interdisciplinary care team members in addressing a positive food insecurity screen are outlined in Table 1.

VHA-Community Partnerships

In addition to services offered within VA, public and private sector partnerships can greatly enhance the range of resources available to food insecure veterans. Several VA facilities have developed formal community partnerships, such as the Veterans Pantry Pilot (VPP) program, a national partnership between Feeding America food banks and VA medical centers to establish onsite or mobile food pantries. There are currently 17 active Feeding America VPP sites, with a number of additional sites under development. Several of the VPP sites also include other “wraparound services,” such as SNAP application assistance.65,66

State Veterans Affairs offices67 and Veterans Service Organizations (VSOs)68 also can serve as valuable partners for connecting veterans with needed resources. VSOs offer a range of services, including assistancewith benefit claims, employment and housing assistance, emergency food assistance, and transportation to medical appointments. Some VSOs also have established local affiliations with Meals on Wheels focused on veteran outreach and providing hot meals for low-income, homebound, and disabled veterans.

Additional Resources

Although resources vary by regional setting, several key governmental and community-based food assistance programs are summarized in Table 2. Local community partners and online/phone-based directories, such as United Way’s 2-1-1 can help identify additional local resources. For older adults and individuals with disabilities, local Aging and Disability Resources Centers can provide information and assistance connecting to needed resources.69 Finally, there are a number of online resources available for clinicians interested in learning more about the impact of food insecurity on health and tools to use in the clinical setting (Table 3).

Conclusion

The VA has recognized food insecurity as a critical concern for the well-being of our nation’s veterans. Use of the EHR clinical reminder represents a crucial first step toward increasing provider awareness about veteran food insecurity and improving clinical efforts to address food insecurity once identified. Through the reminder, health care teams can connect veterans to needed resources and create both the individual and population-level data necessary to inform VHA and community efforts to address veteran food insecurity. Clinical reminder data are currently being used for local quality improvement efforts and have established the need nationally for formalized partnerships between VHA Social Work Services and Nutrition and Food Services to connect veterans with food and provide them with strategies to best use available food resources.

Moving forward, the Ensuring Veteran Food Security Workgroup continues to work with agencies and organizations across the country to improve food insecure veterans’ access to needed services. In addition to existing VA partnerships with Feeding America for the VPP, memorandums of understanding are currently underway to formalize partnerships with both the Food Research and Action Center (FRAC) and MAZON. Additional research is needed both to formally validate the current food insecurity clinical reminder screening question and to identify best practices and potential models for how to most effectively use VHA-community partnerships to address the unique needs of the veteran population.

Ensuring the food security of our nation’s veterans is essential to VA’s commitment to providing integrated, veteran-centered, whole person care. Toward that goal, VA health care teams are urged to use the clinical reminder and help connect food insecure veterans with relevant resources both within and outside of the VA health care system.

Nearly 1 in 8 households—and 1 in 6 households with children—experienced food insecurity in 2017, defined as limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods.1 Food insecurity is often even more pronounced among households with individuals with acute or chronic medical conditions.2-6 Moreover, food insecurity is independently associated with a range of adverse health outcomes, including poorer control of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, depression and other major psychiatric disorders, HIV, and chronic lung and kidney disease, as well as poorer overall health status.7-14 Food insecurity also has been associated with increased health care costs and acute care utilization as well as increased probability of delayed or missed care.15-19

The relationship between food insecurity and poor health outcomes is a complex and often cyclic phenomenon (Figure 1). Poor nutritional status is fueled by limited access to healthful foods as well as increased reliance on calorie-dense and nutrient-poor “junk” foods, which are less expensive and often more readily available in low-income neighborhoods.5,20-24 These compensatory dietary patterns place individuals at higher risk for developing cardiometabolic conditions and for poor control of these conditions.5,8,9,12,25,26 Additionally, the physiological and psychological stressors of food insecurity may precipitate depression and anxiety or worsen existing mental health conditions, resulting in feelings of overwhelm and decreased self-management capacity.5,8,27-31 Food insecurity has further been associated with poor sleep, declines in cognitive function, and increased falls, particularly among the frail and elderly.32-34

Individuals experiencing food insecurity often report having to make trade-offs between food and other necessities, such as paying rent or utilities. Additional strategies to stretch limited resources include cost-related underuse of medication and delays in needed medical care.4,17,31,35 In a nationally representative survey among adults with at least 1 chronic medical condition, 1 in 3 reported having to choose between food and medicine; 11% were unable to afford either.3 Furthermore, the inability to reliably adhere to medication regimens that need to be taken with food can result in potentially life-threatening hypoglycemia (as can lack of food regardless of medication use).5,26,36 In addition to the more obvious risks of glucose-lowering medications, such as insulin and long-acting sulfonylureas in patients experiencing food insecurity, many drugs commonly used among nondiabetic adults such as ACE-inhibitors, β blockers, quinolones, and salicylates can also precipitate hypoglycemia, and food insecurity has been associated with experiences of hypoglycemia even among individuals without diabetes mellitus.32,37 In one study the risk for hospital admissions for hypoglycemia among low-income populations increased by 27% at the end of the month when food budgets were more likely to be exhausted.38 Worsening health status and increased emergency department visits and hospitalizations may then result in lost wages and mounting medical bills, contributing to further financial strain and worsening food insecurity.

Prevalence and Importance of Food Insecurity Among US Veterans

Nearly 1.5 million veterans in the US are living below the federal poverty level (FPL).39 An additional 2.4 million veterans are living paycheck to paycheck at < 200% of the FPL.40 Veterans living in poverty are at even higher risk than nonveterans for food insecurity, homelessness, and other material hardship.41

Estimates of food insecurity among veterans vary widely, ranging from 6% to 24%—nearly twice that of the general US population.8,42-45 Higher rates of food insecurity have been reported among certain high-risk subgroups, including veterans who served in Iraq and Afghanistan (27%), female veterans (28%), homeless and formerly homeless veterans (49%), and veterans with serious mental illness (35%).6,32,43,46 Additional risk factors for food insecurity specific to veteran populations include younger age, having recently left active-duty military service, and lower final military paygrade.42,45-47 As in the general population, veteran food insecurity is associated with a range of adverse health outcomes, including poorer overall health status as well as increased probability of delayed or missed care.6,8,32,42-44,46

Even among veterans enrolled in federal food assistance programs, many still struggle to afford nutritionally adequate foods. As one example, in a study of mostly male homeless and formerly homeless veterans, O’Toole and colleagues found that nearly half of those reporting food insecurity were already receiving federal food assistance benefits, and 22% relied on emergency food resources.32 Of households served by Feeding America food pantries and meal programs, 20% have a member who has served in the US military.48

Federal Programs To Address Food Insecurity

There are several important federal food assistance programs designed to help alleviate food insecurity. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly the Food Stamp program) is the largest federal food assistance program and provides low-income Americans with cash benefits to purchase food. SNAP has been shown to substantially reduce food insecurity.7,49 The program also is associated with significant decreases in cost-related medication nonadherence as well as reductions in health care costs and both acute care and nursing home utilization.16,50-54 Although nearly 1.4 million veterans live in SNAP-enrolled households, 59% of eligible veterans are not enrolled.43,55 Closing this SNAP eligibility-enrollment gap, has been a focus of recent efforts to improve long-term food security among veterans. There also are several federal food assistance programs for households with children, including the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) and school meals programs. Among federal nutrition programs for seniors, the Older American’s Act contains designated funding to support nutrition services for older adults, including congregate meal programs in community settings like senior centers, places of worship, and housing communities, and home-delivered meals through programs like Meals on Wheels.56

VHA Response to Food Insecurity

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the country’s largest integrated, federally funded health care system.57 In November 2015, congressional briefings on veteran food insecurity organized by the national non-profit organization MAZON: A Jewish Response to Hunger and hosted with bipartisan support were provided to the US House and Senate. As a result of these briefings, VHA chartered the national Ensuring Veteran Food Security Workgroup with a mandate to partner with governmental and nonprofit agencies to “focus on the issue of food insecurity, the identification of veterans at risk, the needed training of VHA staff and the coordination of resources and initiatives to support the veterans for whom we care.” Building off a pilot in US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Homeless Patient Aligned Care Teams (H-PACTs),32 VHA subsequently integrated a single-item food insecurity screening tool into the VA electronic health record (EHR) clinical reminder system (Figure 2). The clinical reminder, which was rolled out across VA medical centers nationally in October 2017, provides an alert to screen all noninstitutionalized veterans for food insecurity. To date, nearly 5 million veterans have been screened. When a veteran endorses food insecurity based on the initial screening question, a prompt appears to offer the veteran a referral to a social worker and/or dietitian. Positive screening results also should be communicated to the patient’s primary care provider. Depending on site-specific clinical flow, the reminders are typically completed in the outpatient setting either by nurses or medical assistants during intake or by providers as part of the clinical visit. However, any member of the health care team can complete the clinical reminder at any time. As of September 2019, approximately 74,000 veterans have been identified as food insecure.58

Addressing Food Insecurity

VHA has been a recognized leader in addressing homelessness and other social determinants of health through its integrated care and PACT delivery models.59-61 The food insecurity clinical reminder was designed to facilitate a tailored, interdisciplinary approach to identify and address food insecurity. Interdisciplinary care team members—including medical assistants, clinicians, social workers, registered dietitians, nurse care managers, occupational or physical therapists, and pharmacists—are uniquely positioned to identify veterans impacted by food insecurity, assess for associated clinical and/or social risk factors, and offer appropriate medical and nutrition interventions and resource referrals.

This interdisciplinary team-based model is essential given the range of potential drivers underlying veteran experiences of food insecurity and subsequent health outcomes. It is critically important for clinicians to review the medication list with veterans screening positive for food insecurity to assess for risk of hypoglycemia and/or cost-related nonadherence, make any necessary adjustments to therapeutic regimens, and assess for additional risk factors associated with food insecurity. Examples of tailored nutrition counseling that clinical dietitians may provide include meal preparation strategies for veterans who only have access to a microwave or hotplate, or recommendations for how veterans on medically restricted diets can best navigate food selection at soup kitchens or food pantries. Resource referrals provided by social workers or other care team members may include both emergency food resources to address immediate shortages (eg, food pantries, soup kitchens, or vouchers for free lunch) as well as resources focused on improving longer term food security (eg, federal food assistance programs or home delivered meal programs). Importantly, although providing a list of food resources may be helpful for some patients, such lists are often insufficient.62,63 Many patients require active assistance with program enrollment either onsite the day of their clinic visit or through connection with a partnering community-based organization that can, in turn, identify appropriate resources and facilitate program enrollment.63,64 Planned follow-up is also crucial to determine whether referrals are successful and to assess for ongoing need. Proposed roles for interdisciplinary care team members in addressing a positive food insecurity screen are outlined in Table 1.

VHA-Community Partnerships

In addition to services offered within VA, public and private sector partnerships can greatly enhance the range of resources available to food insecure veterans. Several VA facilities have developed formal community partnerships, such as the Veterans Pantry Pilot (VPP) program, a national partnership between Feeding America food banks and VA medical centers to establish onsite or mobile food pantries. There are currently 17 active Feeding America VPP sites, with a number of additional sites under development. Several of the VPP sites also include other “wraparound services,” such as SNAP application assistance.65,66

State Veterans Affairs offices67 and Veterans Service Organizations (VSOs)68 also can serve as valuable partners for connecting veterans with needed resources. VSOs offer a range of services, including assistancewith benefit claims, employment and housing assistance, emergency food assistance, and transportation to medical appointments. Some VSOs also have established local affiliations with Meals on Wheels focused on veteran outreach and providing hot meals for low-income, homebound, and disabled veterans.

Additional Resources

Although resources vary by regional setting, several key governmental and community-based food assistance programs are summarized in Table 2. Local community partners and online/phone-based directories, such as United Way’s 2-1-1 can help identify additional local resources. For older adults and individuals with disabilities, local Aging and Disability Resources Centers can provide information and assistance connecting to needed resources.69 Finally, there are a number of online resources available for clinicians interested in learning more about the impact of food insecurity on health and tools to use in the clinical setting (Table 3).

Conclusion

The VA has recognized food insecurity as a critical concern for the well-being of our nation’s veterans. Use of the EHR clinical reminder represents a crucial first step toward increasing provider awareness about veteran food insecurity and improving clinical efforts to address food insecurity once identified. Through the reminder, health care teams can connect veterans to needed resources and create both the individual and population-level data necessary to inform VHA and community efforts to address veteran food insecurity. Clinical reminder data are currently being used for local quality improvement efforts and have established the need nationally for formalized partnerships between VHA Social Work Services and Nutrition and Food Services to connect veterans with food and provide them with strategies to best use available food resources.

Moving forward, the Ensuring Veteran Food Security Workgroup continues to work with agencies and organizations across the country to improve food insecure veterans’ access to needed services. In addition to existing VA partnerships with Feeding America for the VPP, memorandums of understanding are currently underway to formalize partnerships with both the Food Research and Action Center (FRAC) and MAZON. Additional research is needed both to formally validate the current food insecurity clinical reminder screening question and to identify best practices and potential models for how to most effectively use VHA-community partnerships to address the unique needs of the veteran population.

Ensuring the food security of our nation’s veterans is essential to VA’s commitment to providing integrated, veteran-centered, whole person care. Toward that goal, VA health care teams are urged to use the clinical reminder and help connect food insecure veterans with relevant resources both within and outside of the VA health care system.

1. Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, Singh A. Household food security in the United States in 2017. http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=90022. Published September 2018. Accessed December 9, 2019.

2. Berkowitz SA, Meigs JB, DeWalt D, et al. Material need insecurities, control of diabetes mellitus, and use of health care resources: results of the Measuring Economic Insecurity in Diabetes study. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):257-265.

3. Berkowitz SA, Seligman HK, Choudhry NK. Treat or eat: food insecurity, cost-related medication underuse, and unmet needs. Am J Med. 2014;127(4):303-310.e3.

4. Lyles CR, Seligman HK, Parker MM, et al. Financial strain and medication adherence among diabetes patients in an integrated health care delivery system: The Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Health Serv Res. 2016;51(2):610-624.

5. Seligman HK, Schillinger D. Hunger and socioeconomic disparities in chronic disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):6-9.

6. Narain K, Bean-Mayberry B, Washington DL, Canelo IA, Darling JE, Yano EM. Access to care and health outcomes among women veterans using veterans administration health care: association with food insufficiency. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28(3):267-272.

7. Gundersen C, Ziliak JP. Food insecurity and health outcomes. Health Aff. 2015;34(11):1830-1839.

8. Wang EA, McGinnis KA, Goulet J, et al; Veterans Aging Cohort Study Project Team. Food insecurity and health: data from the Veterans Aging Cohort Study. Public Health Rep. 2015;130(3):261-268.

9. Berkowitz SA, Berkowitz TSZ, Meigs JB, Wexler DJ. Trends in food insecurity for adults with cardiometabolic disease in the United States: 2005-2012. PloS One. 2017;12(6):e0179172.

10. Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. 2010;140(2):304-310.

11. Berkowitz SA, Baggett TP, Wexler DJ, Huskey KW, Wee CC. Food insecurity and metabolic control among U.S. adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(10):3093-3099.

12. Seligman HK, Jacobs EA, López A, Tschann J, Fernandez A. Food insecurity and glycemic control among low-income patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(2):233-238.

13. Banerjee T, Crews DC, Wesson DE, et al; CDC CKD Surveillance Team. Food insecurity, CKD, and subsequent ESRD in US adults. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70(1):38-47.

14. Bruening M, Dinour LM, Chavez JBR. Food insecurity and emotional health in the USA: a systematic narrative review of longitudinal research. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(17):3200-3208.

15. Berkowitz SA, Basu S, Meigs JB, Seligman HK. Food insecurity and health care expenditures in the United States, 2011-2013. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(3):1600-1620.

16. Berkowitz SA, Seligman HK, Basu S. Impact of food insecurity and SNAP participation on healthcare utilization and expenditures. http://www.ukcpr.org/research/discussion-papers. Published 2017. Accessed December 9, 2019.

17. Kushel MB, Gupta R, Gee L, Haas JS. Housing instability and food insecurity as barriers to health care among low-income Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(1):71-77.

18. Garcia SP, Haddix A, Barnett K. Incremental health care costs associated with food insecurity and chronic conditions among older adults. Chronic Dis. 2018;15:180058.

19. Berkowitz SA, Seligman HK, Meigs JB, Basu S. Food insecurity, healthcare utilization, and high cost: a longitudinal cohort study. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(9):399-404.

20. Larson NI, Story MT, Nelson MC. Neighborhood environments: disparities in access to healthy foods in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(1):74-81.

21. Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: a systematic review and analysis. Nutr Rev. 2015;73(10):643-660.

22. Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Does social class predict diet quality? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(5):1107-1117.

23. Drewnowski A. The cost of US foods as related to their nutritive value. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(5):1181-1188.

24. Lucan SC, Maroko AR, Seitchik JL, Yoon DH, Sperry LE, Schechter CB. Unexpected neighborhood sources of food and drink: implications for research and community health. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(2):e29-e38.

25. Castillo DC, Ramsey NL, Yu SS, Ricks M, Courville AB, Sumner AE. Inconsistent access to food and cardiometabolic disease: the effect of food insecurity. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2012;6(3):245-250.

26. Seligman HK, Davis TC, Schillinger D, Wolf MS. Food insecurity is associated with hypoglycemia and poor diabetes self-management in a low-income sample with diabetes. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(4):1227-1233.

27. Siefert K, Heflin CM, Corcoran ME, Williams DR. Food insufficiency and physical and mental health in a longitudinal survey of welfare recipients. J Health Soc Behav. 2004;45(2):171-186.

28. Mangurian C, Sreshta N, Seligman H. Food insecurity among adults with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(9):931-932.

29. Melchior M, Caspi A, Howard LM, et al. Mental health context of food insecurity: a representative cohort of families with young children. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4):e564-e572.

30. Brostow DP, Gunzburger E, Abbate LM, Brenner LA, Thomas KS. Mental illness, not obesity status, is associated with food insecurity among the elderly in the health and retirement study. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;38(2):149-172.

31. Higashi RT, Craddock Lee SJ, Pezzia C, Quirk L, Leonard T, Pruitt SL. Family and social context contributes to the interplay of economic insecurity, food insecurity, and health. Ann Anthropol Pract. 2017;41(2):67-77.

32. O’Toole TP, Roberts CB, Johnson EE. Screening for food insecurity in six Veterans Administration clinics for the homeless, June-December 2015. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:160375.

33. Feil DG, Pogach LM. Cognitive impairment is a major risk factor for serious hypoglycaemia; public health intervention is warranted. Evid Based Med. 2014;19(2):77.

34. Frith E, Loprinzi PD. Food insecurity and cognitive function in older adults: Brief report. Clin Nutr. 2018;37(5):1765-1768.

35. Herman D, Afulani P, Coleman-Jensen A, Harrison GG. Food insecurity and cost-related medication underuse among nonelderly adults in a nationally representative sample. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10):e48-e59.

36. Tseng C-L, Soroka O, Maney M, Aron DC, Pogach LM. Assessing potential glycemic overtreatment in persons at hypoglycemic risk. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(2):259-268.

37. Vue MH, Setter SM. Drug-induced glucose alterations part 1: drug-induced hypoglycemia. Diabetes Spectr. 2011;24(3):171-177.

38. Seligman HK, Bolger AF, Guzman D, López A, Bibbins-Domingo K. Exhaustion of food budgets at month’s end and hospital admissions for hypoglycemia. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(1):116-123.

39. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Veteran poverty trends. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/specialreports/veteran_poverty_trends.pdf. Published May 2015. Accessed December 9, 2019.

40. Robbins KG, Ravi A. Veterans living paycheck to paycheck are under threat during budget debates. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/poverty/news/2017/09/19/439023/veterans-living-paycheck-paycheck-threat-budget-debates. Published September 19, 2017. Accessed December 9, 2019.

41. Wilmoth JM, London AS, Heflin CM. Economic well-being among older-adult households: variation by veteran and disability status. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2015;58(4):399-419.

42. Brostow DP, Gunzburger E, Thomas KS. Food insecurity among veterans: findings from the health and retirement study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21(10):1358-1364.

43. Pooler J, Mian P, Srinivasan M, Miller Z. Veterans and food insecurity. https://www.impaqint.com/sites/default/files/issue-briefs/VeteransFoodInsecurity_IssueBrief_V1.3.pdf. Published November 2018. Accessed December 9, 2019.

44. Schure MB, Katon JG, Wong E, Liu C-F. Food and housing insecurity and health status among U.S. adults with and without prior military service. SSM Popul Health. 2016;29(2):244-248.

45. Miller DP, Larson MJ, Byrne T, DeVoe E. Food insecurity in veteran households: findings from nationally representative data. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(10):1731-1740.

46. Widome R, Jensen A, Bangerter A, Fu SS. Food insecurity among veterans of the US wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(5):844-849.

47. London AS, Heflin CM. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) use among active-duty military personnel, veterans, and reservists. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2015;34(6):805-826.

48. Weinfield NS, Mills G, Borger C, et al. Hunger in America 2014. Natl rep prepared for Feeding America. https://www.feedingamerica.org/research/hunger-in-america. Published 2014. Accessed December 9, 2019.

49. Mabli J, Ohls J, Dragoset L, Castner L, Santos B. Measuring the Effect of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Participation on Food Security. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service; 2013.

50. Srinivasan M, Pooler JA. Cost-related medication nonadherence for older adults participating in SNAP, 2013–2015. Am J Public Health. 2017;108(2):224-230.

51. Heflin C, Hodges L, Mueser P. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Progam benefits and emergency room visits for hypoglycaemia. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(7):1314-1321.

52. Samuel LJ, Szanton SL, Cahill R, et al. Does the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program affect hospital utilization among older adults? The case of Maryland. Popul Health Manag. 2018;21(2):88-95.

53. Szanton SL, Samuel LJ, Cahill R, et al. Food assistance is associated with decreased nursing home admissions for Maryland’s dually eligible older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):162.

54. Carlson S, Keith-Jennings B. SNAP is linked with improved nutritional outcomes and lower health care costs. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/snap-is-linked-with-improved-nutritional-outcomes-and-lower-health-care. Published January 17, 2018. Accessed December 10, 2019.

55. Keith-Jennings B, Cai L. SNAP helps almost 1.4 million low-income veterans, including thousands in every state. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/snap-helps-almost-14-million-low-income-veterans-including-thousands-in. Updated November 8, 2018. Accessed December 10, 2019.

56. US Department of Health and Human Services. Older Americans Act nutrition programs. https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/news%202017-03/OAA-Nutrition_Programs_Fact_Sheet.pdf. Accessed December 10, 2019.

57. US Department of Veterans Affairs. About VHA. https://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp. Accessed December 10, 2019.

58. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA Corporate Data Warehouse.

59. Yano EM, Bair MJ, Carrasquillo O, Krein SL, Rubenstein LV. Patient aligned care teams (PACT): VA’s journey to implement patient-centered medical homes. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(suppl 2):S547-s549.

60. O’Toole TP, Pape L. Innovative efforts to address homelessness among veterans. N C Med J. 2015;76(5):311-314.

61. O’Toole TP, Johnson EE, Aiello R, Kane V, Pape L. Tailoring care to vulnerable populations by incorporating social determinants of health: the Veterans Health Administration’s “Homeless Patient Aligned Care Team” Program. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:150567.

62. Marpadga S, Fernandez A, Leung J, Tang A, Seligman H, Murphy EJ. Challenges and successes with food resource referrals for food-insecure patients with diabetes. Perm J. 2019;23.

63. Stenmark SH, Steiner JF, Marpadga S, Debor M, Underhill K, Seligman H. Lessons learned from implementation of the food insecurity screening and referral program at Kaiser Permanente Colorado. Perm J. 2018;22.

64. Martel ML, Klein LR, Hager KA, Cutts DB. Emergency department experience with novel electronic medical record order for referral to food resources. West J Emerg Med. 2018;19(2):232-237.

65. Going C, Cohen AJ, Bares M, Christensen M. Interdisciplinary approaches to addressing the food insecure veteran. Veterans Health Administration Employee Education System webinar; October 30, 2018.

66. Feeding America Announces New Partnership With U.S. Department Of Veterans Affairs. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/feeding-america-announces-new-partnership-with-us-department-of-veterans-affairs-300481891.html. Published June 29, 2017. Accessed December 10, 2019.

67. US Department of Veterans Affairs. State Veterans Affairs offices. https://www.va.gov/statedva.htm. Updated March 20, 2019. Accessed December 10, 2019.

68. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Directory of veterans service organizations. https://www.va.gov/vso. Updated December 24, 2013. Accessed December 10, 2019.

69. ACL Administration for Community Living. Aging and disability resource centers. https://acl.gov/programs/aging-and-disability-networks/aging-and-disability-resource-centers. Updated December 13, 2017. Accessed December 10, 2019.

70. Nutrition and Obesity Policy Research and Evaluation Network (NOPREN). Clinical screening algorithms. https://nopren.org/resource/download-food-insecurity-screening-and-referral-algorithms-for-adults-patients-living-with-diabetes-and-pediatric-patients. Accessed December 10, 2019.

1. Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, Singh A. Household food security in the United States in 2017. http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=90022. Published September 2018. Accessed December 9, 2019.

2. Berkowitz SA, Meigs JB, DeWalt D, et al. Material need insecurities, control of diabetes mellitus, and use of health care resources: results of the Measuring Economic Insecurity in Diabetes study. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):257-265.

3. Berkowitz SA, Seligman HK, Choudhry NK. Treat or eat: food insecurity, cost-related medication underuse, and unmet needs. Am J Med. 2014;127(4):303-310.e3.

4. Lyles CR, Seligman HK, Parker MM, et al. Financial strain and medication adherence among diabetes patients in an integrated health care delivery system: The Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Health Serv Res. 2016;51(2):610-624.

5. Seligman HK, Schillinger D. Hunger and socioeconomic disparities in chronic disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):6-9.

6. Narain K, Bean-Mayberry B, Washington DL, Canelo IA, Darling JE, Yano EM. Access to care and health outcomes among women veterans using veterans administration health care: association with food insufficiency. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28(3):267-272.

7. Gundersen C, Ziliak JP. Food insecurity and health outcomes. Health Aff. 2015;34(11):1830-1839.

8. Wang EA, McGinnis KA, Goulet J, et al; Veterans Aging Cohort Study Project Team. Food insecurity and health: data from the Veterans Aging Cohort Study. Public Health Rep. 2015;130(3):261-268.

9. Berkowitz SA, Berkowitz TSZ, Meigs JB, Wexler DJ. Trends in food insecurity for adults with cardiometabolic disease in the United States: 2005-2012. PloS One. 2017;12(6):e0179172.

10. Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. 2010;140(2):304-310.

11. Berkowitz SA, Baggett TP, Wexler DJ, Huskey KW, Wee CC. Food insecurity and metabolic control among U.S. adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(10):3093-3099.

12. Seligman HK, Jacobs EA, López A, Tschann J, Fernandez A. Food insecurity and glycemic control among low-income patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(2):233-238.

13. Banerjee T, Crews DC, Wesson DE, et al; CDC CKD Surveillance Team. Food insecurity, CKD, and subsequent ESRD in US adults. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70(1):38-47.

14. Bruening M, Dinour LM, Chavez JBR. Food insecurity and emotional health in the USA: a systematic narrative review of longitudinal research. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(17):3200-3208.

15. Berkowitz SA, Basu S, Meigs JB, Seligman HK. Food insecurity and health care expenditures in the United States, 2011-2013. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(3):1600-1620.

16. Berkowitz SA, Seligman HK, Basu S. Impact of food insecurity and SNAP participation on healthcare utilization and expenditures. http://www.ukcpr.org/research/discussion-papers. Published 2017. Accessed December 9, 2019.

17. Kushel MB, Gupta R, Gee L, Haas JS. Housing instability and food insecurity as barriers to health care among low-income Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(1):71-77.

18. Garcia SP, Haddix A, Barnett K. Incremental health care costs associated with food insecurity and chronic conditions among older adults. Chronic Dis. 2018;15:180058.

19. Berkowitz SA, Seligman HK, Meigs JB, Basu S. Food insecurity, healthcare utilization, and high cost: a longitudinal cohort study. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(9):399-404.

20. Larson NI, Story MT, Nelson MC. Neighborhood environments: disparities in access to healthy foods in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(1):74-81.

21. Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: a systematic review and analysis. Nutr Rev. 2015;73(10):643-660.

22. Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Does social class predict diet quality? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(5):1107-1117.

23. Drewnowski A. The cost of US foods as related to their nutritive value. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(5):1181-1188.

24. Lucan SC, Maroko AR, Seitchik JL, Yoon DH, Sperry LE, Schechter CB. Unexpected neighborhood sources of food and drink: implications for research and community health. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(2):e29-e38.

25. Castillo DC, Ramsey NL, Yu SS, Ricks M, Courville AB, Sumner AE. Inconsistent access to food and cardiometabolic disease: the effect of food insecurity. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2012;6(3):245-250.

26. Seligman HK, Davis TC, Schillinger D, Wolf MS. Food insecurity is associated with hypoglycemia and poor diabetes self-management in a low-income sample with diabetes. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(4):1227-1233.

27. Siefert K, Heflin CM, Corcoran ME, Williams DR. Food insufficiency and physical and mental health in a longitudinal survey of welfare recipients. J Health Soc Behav. 2004;45(2):171-186.

28. Mangurian C, Sreshta N, Seligman H. Food insecurity among adults with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(9):931-932.

29. Melchior M, Caspi A, Howard LM, et al. Mental health context of food insecurity: a representative cohort of families with young children. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4):e564-e572.

30. Brostow DP, Gunzburger E, Abbate LM, Brenner LA, Thomas KS. Mental illness, not obesity status, is associated with food insecurity among the elderly in the health and retirement study. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;38(2):149-172.

31. Higashi RT, Craddock Lee SJ, Pezzia C, Quirk L, Leonard T, Pruitt SL. Family and social context contributes to the interplay of economic insecurity, food insecurity, and health. Ann Anthropol Pract. 2017;41(2):67-77.

32. O’Toole TP, Roberts CB, Johnson EE. Screening for food insecurity in six Veterans Administration clinics for the homeless, June-December 2015. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:160375.

33. Feil DG, Pogach LM. Cognitive impairment is a major risk factor for serious hypoglycaemia; public health intervention is warranted. Evid Based Med. 2014;19(2):77.

34. Frith E, Loprinzi PD. Food insecurity and cognitive function in older adults: Brief report. Clin Nutr. 2018;37(5):1765-1768.

35. Herman D, Afulani P, Coleman-Jensen A, Harrison GG. Food insecurity and cost-related medication underuse among nonelderly adults in a nationally representative sample. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10):e48-e59.

36. Tseng C-L, Soroka O, Maney M, Aron DC, Pogach LM. Assessing potential glycemic overtreatment in persons at hypoglycemic risk. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(2):259-268.

37. Vue MH, Setter SM. Drug-induced glucose alterations part 1: drug-induced hypoglycemia. Diabetes Spectr. 2011;24(3):171-177.

38. Seligman HK, Bolger AF, Guzman D, López A, Bibbins-Domingo K. Exhaustion of food budgets at month’s end and hospital admissions for hypoglycemia. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(1):116-123.

39. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Veteran poverty trends. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/specialreports/veteran_poverty_trends.pdf. Published May 2015. Accessed December 9, 2019.

40. Robbins KG, Ravi A. Veterans living paycheck to paycheck are under threat during budget debates. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/poverty/news/2017/09/19/439023/veterans-living-paycheck-paycheck-threat-budget-debates. Published September 19, 2017. Accessed December 9, 2019.

41. Wilmoth JM, London AS, Heflin CM. Economic well-being among older-adult households: variation by veteran and disability status. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2015;58(4):399-419.

42. Brostow DP, Gunzburger E, Thomas KS. Food insecurity among veterans: findings from the health and retirement study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21(10):1358-1364.

43. Pooler J, Mian P, Srinivasan M, Miller Z. Veterans and food insecurity. https://www.impaqint.com/sites/default/files/issue-briefs/VeteransFoodInsecurity_IssueBrief_V1.3.pdf. Published November 2018. Accessed December 9, 2019.

44. Schure MB, Katon JG, Wong E, Liu C-F. Food and housing insecurity and health status among U.S. adults with and without prior military service. SSM Popul Health. 2016;29(2):244-248.

45. Miller DP, Larson MJ, Byrne T, DeVoe E. Food insecurity in veteran households: findings from nationally representative data. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(10):1731-1740.

46. Widome R, Jensen A, Bangerter A, Fu SS. Food insecurity among veterans of the US wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(5):844-849.