User login

Nondirected testing for inpatients with severe liver injury

The “Things We Do for No Reason” series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

CASE REPORT

A 68-year-old woman with ischemic cardiomyopathy was admitted with abdominal cramping, diarrhea, and nausea, which had left her unable to keep food and liquids down for 2 days. She had been taking diuretics and had a remote history of intravenous drug use. On admission, she was afebrile and had blood pressure of 100/60 mm Hg and a heart rate of 100 bpm. Her extremities were cool and clammy. Blood test results showed an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 1510 IU/L and an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level of 1643 IU/L. The patient’s clinician did not know her baseline ALT and AST levels and thought the best approach was to identify the cause of the transaminase elevation.

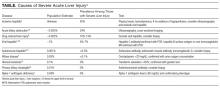

Severe acute liver injury (liver enzymes, >10 × upper limit of normal [ULN], usually 40 IU/L) is a common presentation among hospitalized patients. Between 1997 and 2015, 1.5% of patients admitted to our hospital had severe liver injury. In another large cohort of hospitalized patients,1 0.6% had an ALT level higher than 1000 IU/L (~20 × ULN). A precise diagnosis is often needed to direct appropriate therapy, and serologic tests are available for many conditions, both common and rare (Table). Given the relative ease of bundled blood testing, nondirected testing has emerged as a popular, if reflexive, strategy.2-5 In this approach, clinicians evaluate each patient for the set of testable diseases all at once—in contrast to taking a directed, stepwise testing approach guided by the patient’s history.

Use of nondirected testing is common in patients with severe acute liver injury. Of the 5795 such patients treated at our hospital between 2000 and 2015, within the same day of service 53% were tested for hepatitis C virus antibody, 38% for hemochromatosis (ferritin test), 28% for autoimmune hepatitis (antinuclear antibody test), and 15% for primary biliary cholangitis (antimitochondrial antibody test) by our clinical laboratory. Of the 5023 patients who had send-out tests performed for Wilson disease (ceruloplasmin), 81% were queried for hepatitis B virus infection, 76% for hepatitis C virus infection, 75% for autoimmune hepatitis, and 73.1% for hemochromatosis.2 Similar trends were found for patients with severe liver injury tested for α1-antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency.3 In sum, these data showed that each patient with severe liver injury was tested out of concern about diseases with markedly different epidemiology and clinical presentations (Table).

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK NONDIRECTED TESTING IS HELPFUL

Use of nondirected testing may reflect perceived urgency, convenience, and thoroughness.2-6 Alternatively, it may simply involve following a consultant’s recommendations.4 As severe acute liver injury is often associated with tremendous morbidity, clinicians seeking answers may perceive directed, stepwise testing as inappropriately slow given the urgency of the presentation; they may think that nondirected testing can reduce hospital length of stay.

WHY NONDIRECTED TESTING IS NOT HELPFUL

Nondirected testing is a problem for at least 4 reasons: limited benefit of reflexive testing for rare diseases, no meaningful impact on outcomes, false positives, and financial cost.

First, immediately testing for rare causes of liver disease is unlikely to benefit patients with severe liver injury. The underlying etiologies of severe liver injury are relatively well circumscribed (Table). Overall, 42% of patients with severe liver injury and 57% of those with an ALT level higher than 1000 IU/L have ischemic hepatitis.7 Accounting for a significant percentage of severe liver injury cases are acute biliary obstruction (24%), drug-induced injury (10%-13%), and viral hepatitis (4%-7%).1,8 Of the small subset of patients with severe liver injury that progresses to acute liver failure (ALF; encephalopathy, coagulopathy), 0.5% have autoimmune hepatitis and 0.1% have Wilson disease.9 Furthermore, many patients are tested for AAT deficiency, hemochromatosis, and primary biliary cholangitis, but these are never causes of severe acute liver injury (Table).

Second, diagnosing a rarer cause of acute liver injury modestly earlier has no meaningful impact on outcome. Work-up for more common etiologies can usually be completed within 2 or 3 days. This is true even for patients with ALF. Specific therapies generally are lacking for ALF, save for use of N-acetylcysteine for acetaminophen overdose and antiviral therapy for hepatitis B virus infection.9,10 Furthermore, although effective therapies are available for both autoimmune hepatitis and Wilson disease, the potential benefit stems from altering the longer term course of disease. Initial management, even for these rare conditions, is no different from that for other etiologies. Conversely, acute liver injury caused by ischemic hepatitis, biliary disease, or drug-induced liver injury requires swift corrective action. Even if normotensive, patients with ischemic hepatitis are often in cardiogenic shock and benefit from careful monitoring and critical care.7 Patients with acute biliary obstruction may need therapeutic endoscopy. Last, patients with drug-induced liver injury benefit from immediate discontinuation of the offending drug.

Third, in the testing of patients with low pretest probabilities, false positives are common. For example, at our institution and at an institution in Austria, severe liver injury patients with a low ceruloplasmin level have a 95.1% to 98.1% chance of a false-positive result (they have a low ceruloplasmin level but do not have Wilson disease).3,4 Furthermore, 91% of positive tests are never confirmed,3 indicating either that clinicians never valued the initial test or that other diagnoses were much more likely. Even worse, as was the case in 65% of patients with low AAT levels,2,3 genetic diagnoses were based on unconfirmed, potentially false-positive serologic tests.

Fourth, although the financial cost for each individual test is small, at the population level the cost of nondirected testing is significant. For example, although each reflects testing for conditions that do not cause acute liver injury, the costs of ferritin, AAT, and antimitochondrial antibody tests are $13, $16, and $37, respectively (Medicare/Medicaid reimbursements in 2016 $US).11 About 1.5% of admitted patients are found to have severe liver injury. If this proportion holds true for the roughly 40 million discharges from US hospitals each year, then there would be an annual cost of about $40 million if all 3 tests were performed for each patient with severe liver injury. In addition, although nondirected testing may seem clinically expedient, there are no data suggesting it reduces length of stay. In fact, ceruloplasmin, AAT, and many other tests are sent to external laboratories and are unlikely to be returned before discharge. If clinicians delay discharge for results, then nondirected testing would increase rather than decrease length of stay.

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

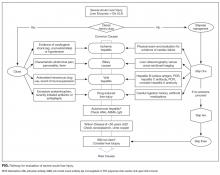

In this era of increasing cost-consciousness, nondirected testing has escaped relatively unscathed. Indeed, nondirected testing is prevalent, yet has pitfalls similar to those of serologic testing (eg, vasculitis or arthritis,6 acute renal injury, infectious disease12). The alternative is deliberate, empirical, patient-centered testing that is attentive to the patient’s presentation and the harms of false positives. The idea is to select tests for each patient with acute liver injury according to presentation and the most likely corresponding diagnoses (Table, Figure).

The “one-stop shopping” in providers’ electronic order entry systems makes it too easy to over-order tests. Fortunately, these systems’ simple and effective decision supports can force pauses in the ordering process, create barriers to waste, and provide education about test characteristics and costs.4,5,13 Our medical center’s volume of ceruloplasmin orders decreased by 80% after a change was made to its ordering system; the ordering of a ceruloplasmin test is now interrupted by a pop-up screen that displays test characteristics and an option to continue or cancel the order.4,5 Hospitals should consider implementing clinical decision supports in this area. Successful interventions provide electronic rather than paper-based support as part of the clinical workflow, during the ordering process, and recommendations rather than assessments.13

RECOMMENDATIONS

- For each patient with severe acute liver injury, select tests on the basis of the presentation (Figure). Testing for rare diseases should be performed only after common diseases have been excluded.

- Avoid testing for hemochromatosis (iron indices, genetic tests), AAT deficiency (AAT levels or phenotypes), and primary biliary cholangitis (antimitochondrial antibodies) in patients with severe acute liver injury.

- Consider implementing decision supports that can curb nondirected testing in areas in which it is common.

CONCLUSION

Nondirected testing is associated with false positives and increased costs in the evaluation and management of severe acute liver injury. The alternative is deliberate, epidemiologically and clinically driven directed testing. Electronic ordering system decision supports can be useful in curtailing nondirected testing.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason”? Let us know what you do in your practice and propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics. Please join in the conversation online at Twitter (#TWDFNR)/Facebook and don’t forget to “Like It” on Facebook or retweet it on Twitter.

1. Johnson RD, O’Connor ML, Kerr RM. Extreme serum elevations of aspartate aminotransferase. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90(8):1244-1245. PubMed

2. Tapper EB, Patwardhan VR, Curry M. Low yield and utilization of confirmatory testing in a cohort of patients with liver disease assessed for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(6):1589-1594. PubMed

3. Tapper EB, Rahni DO, Arnaout R, Lai M. The overuse of serum ceruloplasmin measurement. Am J Med. 2013;126(10):926.e1-e5. PubMed

4. Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Lai M, Horowitz G. Understanding and reducing ceruloplasmin overuse with a decision support intervention for liver disease evaluation. Am J Med. 2016;129(1):115.e17-e22. PubMed

5. Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Lai M, Horowitz G. A decision support tool to reduce overtesting for ceruloplasmin and improve adherence with clinical guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1561-1562. PubMed

6. Lichtenstein MJ, Pincus T. How useful are combinations of blood tests in “rheumatic panels” in diagnosis of rheumatic diseases? J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3(5):435-442. PubMed

7. Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Bonder A. The incidence and outcomes of ischemic hepatitis: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2015;128(12):1314-1321. PubMed

8. Whitehead MW, Hawkes ND, Hainsworth I, Kingham JG. A prospective study of the causes of notably raised aspartate aminotransferase of liver origin. Gut. 1999;45(1):129-133. PubMed

9. Fontana RJ. Acute liver failure including acetaminophen overdose. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92(4):761-794. PubMed

10. Lee WM, Larson AM, Stravitz RT. AASLD Position Paper: The Management of Acute Liver Failure: Update 2011. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases website. https://www.aasld.org/sites/default/files/guideline_documents/alfenhanced.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed January 26, 2017.

11. Green RM, Flamm S. AGA technical review on the evaluation of liver chemistry tests. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(4):1367-1384. PubMed

12. Aesif SW, Parenti DM, Lesky L, Keiser JF. A cost-effective interdisciplinary approach to microbiologic send-out test use. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139(2):194-198. PubMed

13. Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, Lobach DF. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ. 2005;330(7494):765. PubMed

14. Boberg KM. Prevalence and epidemiology of autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Liver Dis. 2002;6(3):635-647. PubMed

15. Bacon BR, Adams PC, Kowdley KV, Powell LW, Tavill AS; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis and management of hemochromatosis: 2011 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2011;54(1):328-343. PubMed

16. Boonstra K, Beuers U, Ponsioen CY. Epidemiology of primary sclerosing cholangitis and primary biliary cirrhosis: a systematic review. J Hepatol. 2012;56(5):1181-1188. PubMed

The “Things We Do for No Reason” series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

CASE REPORT

A 68-year-old woman with ischemic cardiomyopathy was admitted with abdominal cramping, diarrhea, and nausea, which had left her unable to keep food and liquids down for 2 days. She had been taking diuretics and had a remote history of intravenous drug use. On admission, she was afebrile and had blood pressure of 100/60 mm Hg and a heart rate of 100 bpm. Her extremities were cool and clammy. Blood test results showed an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 1510 IU/L and an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level of 1643 IU/L. The patient’s clinician did not know her baseline ALT and AST levels and thought the best approach was to identify the cause of the transaminase elevation.

Severe acute liver injury (liver enzymes, >10 × upper limit of normal [ULN], usually 40 IU/L) is a common presentation among hospitalized patients. Between 1997 and 2015, 1.5% of patients admitted to our hospital had severe liver injury. In another large cohort of hospitalized patients,1 0.6% had an ALT level higher than 1000 IU/L (~20 × ULN). A precise diagnosis is often needed to direct appropriate therapy, and serologic tests are available for many conditions, both common and rare (Table). Given the relative ease of bundled blood testing, nondirected testing has emerged as a popular, if reflexive, strategy.2-5 In this approach, clinicians evaluate each patient for the set of testable diseases all at once—in contrast to taking a directed, stepwise testing approach guided by the patient’s history.

Use of nondirected testing is common in patients with severe acute liver injury. Of the 5795 such patients treated at our hospital between 2000 and 2015, within the same day of service 53% were tested for hepatitis C virus antibody, 38% for hemochromatosis (ferritin test), 28% for autoimmune hepatitis (antinuclear antibody test), and 15% for primary biliary cholangitis (antimitochondrial antibody test) by our clinical laboratory. Of the 5023 patients who had send-out tests performed for Wilson disease (ceruloplasmin), 81% were queried for hepatitis B virus infection, 76% for hepatitis C virus infection, 75% for autoimmune hepatitis, and 73.1% for hemochromatosis.2 Similar trends were found for patients with severe liver injury tested for α1-antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency.3 In sum, these data showed that each patient with severe liver injury was tested out of concern about diseases with markedly different epidemiology and clinical presentations (Table).

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK NONDIRECTED TESTING IS HELPFUL

Use of nondirected testing may reflect perceived urgency, convenience, and thoroughness.2-6 Alternatively, it may simply involve following a consultant’s recommendations.4 As severe acute liver injury is often associated with tremendous morbidity, clinicians seeking answers may perceive directed, stepwise testing as inappropriately slow given the urgency of the presentation; they may think that nondirected testing can reduce hospital length of stay.

WHY NONDIRECTED TESTING IS NOT HELPFUL

Nondirected testing is a problem for at least 4 reasons: limited benefit of reflexive testing for rare diseases, no meaningful impact on outcomes, false positives, and financial cost.

First, immediately testing for rare causes of liver disease is unlikely to benefit patients with severe liver injury. The underlying etiologies of severe liver injury are relatively well circumscribed (Table). Overall, 42% of patients with severe liver injury and 57% of those with an ALT level higher than 1000 IU/L have ischemic hepatitis.7 Accounting for a significant percentage of severe liver injury cases are acute biliary obstruction (24%), drug-induced injury (10%-13%), and viral hepatitis (4%-7%).1,8 Of the small subset of patients with severe liver injury that progresses to acute liver failure (ALF; encephalopathy, coagulopathy), 0.5% have autoimmune hepatitis and 0.1% have Wilson disease.9 Furthermore, many patients are tested for AAT deficiency, hemochromatosis, and primary biliary cholangitis, but these are never causes of severe acute liver injury (Table).

Second, diagnosing a rarer cause of acute liver injury modestly earlier has no meaningful impact on outcome. Work-up for more common etiologies can usually be completed within 2 or 3 days. This is true even for patients with ALF. Specific therapies generally are lacking for ALF, save for use of N-acetylcysteine for acetaminophen overdose and antiviral therapy for hepatitis B virus infection.9,10 Furthermore, although effective therapies are available for both autoimmune hepatitis and Wilson disease, the potential benefit stems from altering the longer term course of disease. Initial management, even for these rare conditions, is no different from that for other etiologies. Conversely, acute liver injury caused by ischemic hepatitis, biliary disease, or drug-induced liver injury requires swift corrective action. Even if normotensive, patients with ischemic hepatitis are often in cardiogenic shock and benefit from careful monitoring and critical care.7 Patients with acute biliary obstruction may need therapeutic endoscopy. Last, patients with drug-induced liver injury benefit from immediate discontinuation of the offending drug.

Third, in the testing of patients with low pretest probabilities, false positives are common. For example, at our institution and at an institution in Austria, severe liver injury patients with a low ceruloplasmin level have a 95.1% to 98.1% chance of a false-positive result (they have a low ceruloplasmin level but do not have Wilson disease).3,4 Furthermore, 91% of positive tests are never confirmed,3 indicating either that clinicians never valued the initial test or that other diagnoses were much more likely. Even worse, as was the case in 65% of patients with low AAT levels,2,3 genetic diagnoses were based on unconfirmed, potentially false-positive serologic tests.

Fourth, although the financial cost for each individual test is small, at the population level the cost of nondirected testing is significant. For example, although each reflects testing for conditions that do not cause acute liver injury, the costs of ferritin, AAT, and antimitochondrial antibody tests are $13, $16, and $37, respectively (Medicare/Medicaid reimbursements in 2016 $US).11 About 1.5% of admitted patients are found to have severe liver injury. If this proportion holds true for the roughly 40 million discharges from US hospitals each year, then there would be an annual cost of about $40 million if all 3 tests were performed for each patient with severe liver injury. In addition, although nondirected testing may seem clinically expedient, there are no data suggesting it reduces length of stay. In fact, ceruloplasmin, AAT, and many other tests are sent to external laboratories and are unlikely to be returned before discharge. If clinicians delay discharge for results, then nondirected testing would increase rather than decrease length of stay.

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

In this era of increasing cost-consciousness, nondirected testing has escaped relatively unscathed. Indeed, nondirected testing is prevalent, yet has pitfalls similar to those of serologic testing (eg, vasculitis or arthritis,6 acute renal injury, infectious disease12). The alternative is deliberate, empirical, patient-centered testing that is attentive to the patient’s presentation and the harms of false positives. The idea is to select tests for each patient with acute liver injury according to presentation and the most likely corresponding diagnoses (Table, Figure).

The “one-stop shopping” in providers’ electronic order entry systems makes it too easy to over-order tests. Fortunately, these systems’ simple and effective decision supports can force pauses in the ordering process, create barriers to waste, and provide education about test characteristics and costs.4,5,13 Our medical center’s volume of ceruloplasmin orders decreased by 80% after a change was made to its ordering system; the ordering of a ceruloplasmin test is now interrupted by a pop-up screen that displays test characteristics and an option to continue or cancel the order.4,5 Hospitals should consider implementing clinical decision supports in this area. Successful interventions provide electronic rather than paper-based support as part of the clinical workflow, during the ordering process, and recommendations rather than assessments.13

RECOMMENDATIONS

- For each patient with severe acute liver injury, select tests on the basis of the presentation (Figure). Testing for rare diseases should be performed only after common diseases have been excluded.

- Avoid testing for hemochromatosis (iron indices, genetic tests), AAT deficiency (AAT levels or phenotypes), and primary biliary cholangitis (antimitochondrial antibodies) in patients with severe acute liver injury.

- Consider implementing decision supports that can curb nondirected testing in areas in which it is common.

CONCLUSION

Nondirected testing is associated with false positives and increased costs in the evaluation and management of severe acute liver injury. The alternative is deliberate, epidemiologically and clinically driven directed testing. Electronic ordering system decision supports can be useful in curtailing nondirected testing.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason”? Let us know what you do in your practice and propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics. Please join in the conversation online at Twitter (#TWDFNR)/Facebook and don’t forget to “Like It” on Facebook or retweet it on Twitter.

The “Things We Do for No Reason” series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

CASE REPORT

A 68-year-old woman with ischemic cardiomyopathy was admitted with abdominal cramping, diarrhea, and nausea, which had left her unable to keep food and liquids down for 2 days. She had been taking diuretics and had a remote history of intravenous drug use. On admission, she was afebrile and had blood pressure of 100/60 mm Hg and a heart rate of 100 bpm. Her extremities were cool and clammy. Blood test results showed an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 1510 IU/L and an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level of 1643 IU/L. The patient’s clinician did not know her baseline ALT and AST levels and thought the best approach was to identify the cause of the transaminase elevation.

Severe acute liver injury (liver enzymes, >10 × upper limit of normal [ULN], usually 40 IU/L) is a common presentation among hospitalized patients. Between 1997 and 2015, 1.5% of patients admitted to our hospital had severe liver injury. In another large cohort of hospitalized patients,1 0.6% had an ALT level higher than 1000 IU/L (~20 × ULN). A precise diagnosis is often needed to direct appropriate therapy, and serologic tests are available for many conditions, both common and rare (Table). Given the relative ease of bundled blood testing, nondirected testing has emerged as a popular, if reflexive, strategy.2-5 In this approach, clinicians evaluate each patient for the set of testable diseases all at once—in contrast to taking a directed, stepwise testing approach guided by the patient’s history.

Use of nondirected testing is common in patients with severe acute liver injury. Of the 5795 such patients treated at our hospital between 2000 and 2015, within the same day of service 53% were tested for hepatitis C virus antibody, 38% for hemochromatosis (ferritin test), 28% for autoimmune hepatitis (antinuclear antibody test), and 15% for primary biliary cholangitis (antimitochondrial antibody test) by our clinical laboratory. Of the 5023 patients who had send-out tests performed for Wilson disease (ceruloplasmin), 81% were queried for hepatitis B virus infection, 76% for hepatitis C virus infection, 75% for autoimmune hepatitis, and 73.1% for hemochromatosis.2 Similar trends were found for patients with severe liver injury tested for α1-antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency.3 In sum, these data showed that each patient with severe liver injury was tested out of concern about diseases with markedly different epidemiology and clinical presentations (Table).

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK NONDIRECTED TESTING IS HELPFUL

Use of nondirected testing may reflect perceived urgency, convenience, and thoroughness.2-6 Alternatively, it may simply involve following a consultant’s recommendations.4 As severe acute liver injury is often associated with tremendous morbidity, clinicians seeking answers may perceive directed, stepwise testing as inappropriately slow given the urgency of the presentation; they may think that nondirected testing can reduce hospital length of stay.

WHY NONDIRECTED TESTING IS NOT HELPFUL

Nondirected testing is a problem for at least 4 reasons: limited benefit of reflexive testing for rare diseases, no meaningful impact on outcomes, false positives, and financial cost.

First, immediately testing for rare causes of liver disease is unlikely to benefit patients with severe liver injury. The underlying etiologies of severe liver injury are relatively well circumscribed (Table). Overall, 42% of patients with severe liver injury and 57% of those with an ALT level higher than 1000 IU/L have ischemic hepatitis.7 Accounting for a significant percentage of severe liver injury cases are acute biliary obstruction (24%), drug-induced injury (10%-13%), and viral hepatitis (4%-7%).1,8 Of the small subset of patients with severe liver injury that progresses to acute liver failure (ALF; encephalopathy, coagulopathy), 0.5% have autoimmune hepatitis and 0.1% have Wilson disease.9 Furthermore, many patients are tested for AAT deficiency, hemochromatosis, and primary biliary cholangitis, but these are never causes of severe acute liver injury (Table).

Second, diagnosing a rarer cause of acute liver injury modestly earlier has no meaningful impact on outcome. Work-up for more common etiologies can usually be completed within 2 or 3 days. This is true even for patients with ALF. Specific therapies generally are lacking for ALF, save for use of N-acetylcysteine for acetaminophen overdose and antiviral therapy for hepatitis B virus infection.9,10 Furthermore, although effective therapies are available for both autoimmune hepatitis and Wilson disease, the potential benefit stems from altering the longer term course of disease. Initial management, even for these rare conditions, is no different from that for other etiologies. Conversely, acute liver injury caused by ischemic hepatitis, biliary disease, or drug-induced liver injury requires swift corrective action. Even if normotensive, patients with ischemic hepatitis are often in cardiogenic shock and benefit from careful monitoring and critical care.7 Patients with acute biliary obstruction may need therapeutic endoscopy. Last, patients with drug-induced liver injury benefit from immediate discontinuation of the offending drug.

Third, in the testing of patients with low pretest probabilities, false positives are common. For example, at our institution and at an institution in Austria, severe liver injury patients with a low ceruloplasmin level have a 95.1% to 98.1% chance of a false-positive result (they have a low ceruloplasmin level but do not have Wilson disease).3,4 Furthermore, 91% of positive tests are never confirmed,3 indicating either that clinicians never valued the initial test or that other diagnoses were much more likely. Even worse, as was the case in 65% of patients with low AAT levels,2,3 genetic diagnoses were based on unconfirmed, potentially false-positive serologic tests.

Fourth, although the financial cost for each individual test is small, at the population level the cost of nondirected testing is significant. For example, although each reflects testing for conditions that do not cause acute liver injury, the costs of ferritin, AAT, and antimitochondrial antibody tests are $13, $16, and $37, respectively (Medicare/Medicaid reimbursements in 2016 $US).11 About 1.5% of admitted patients are found to have severe liver injury. If this proportion holds true for the roughly 40 million discharges from US hospitals each year, then there would be an annual cost of about $40 million if all 3 tests were performed for each patient with severe liver injury. In addition, although nondirected testing may seem clinically expedient, there are no data suggesting it reduces length of stay. In fact, ceruloplasmin, AAT, and many other tests are sent to external laboratories and are unlikely to be returned before discharge. If clinicians delay discharge for results, then nondirected testing would increase rather than decrease length of stay.

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

In this era of increasing cost-consciousness, nondirected testing has escaped relatively unscathed. Indeed, nondirected testing is prevalent, yet has pitfalls similar to those of serologic testing (eg, vasculitis or arthritis,6 acute renal injury, infectious disease12). The alternative is deliberate, empirical, patient-centered testing that is attentive to the patient’s presentation and the harms of false positives. The idea is to select tests for each patient with acute liver injury according to presentation and the most likely corresponding diagnoses (Table, Figure).

The “one-stop shopping” in providers’ electronic order entry systems makes it too easy to over-order tests. Fortunately, these systems’ simple and effective decision supports can force pauses in the ordering process, create barriers to waste, and provide education about test characteristics and costs.4,5,13 Our medical center’s volume of ceruloplasmin orders decreased by 80% after a change was made to its ordering system; the ordering of a ceruloplasmin test is now interrupted by a pop-up screen that displays test characteristics and an option to continue or cancel the order.4,5 Hospitals should consider implementing clinical decision supports in this area. Successful interventions provide electronic rather than paper-based support as part of the clinical workflow, during the ordering process, and recommendations rather than assessments.13

RECOMMENDATIONS

- For each patient with severe acute liver injury, select tests on the basis of the presentation (Figure). Testing for rare diseases should be performed only after common diseases have been excluded.

- Avoid testing for hemochromatosis (iron indices, genetic tests), AAT deficiency (AAT levels or phenotypes), and primary biliary cholangitis (antimitochondrial antibodies) in patients with severe acute liver injury.

- Consider implementing decision supports that can curb nondirected testing in areas in which it is common.

CONCLUSION

Nondirected testing is associated with false positives and increased costs in the evaluation and management of severe acute liver injury. The alternative is deliberate, epidemiologically and clinically driven directed testing. Electronic ordering system decision supports can be useful in curtailing nondirected testing.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason”? Let us know what you do in your practice and propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics. Please join in the conversation online at Twitter (#TWDFNR)/Facebook and don’t forget to “Like It” on Facebook or retweet it on Twitter.

1. Johnson RD, O’Connor ML, Kerr RM. Extreme serum elevations of aspartate aminotransferase. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90(8):1244-1245. PubMed

2. Tapper EB, Patwardhan VR, Curry M. Low yield and utilization of confirmatory testing in a cohort of patients with liver disease assessed for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(6):1589-1594. PubMed

3. Tapper EB, Rahni DO, Arnaout R, Lai M. The overuse of serum ceruloplasmin measurement. Am J Med. 2013;126(10):926.e1-e5. PubMed

4. Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Lai M, Horowitz G. Understanding and reducing ceruloplasmin overuse with a decision support intervention for liver disease evaluation. Am J Med. 2016;129(1):115.e17-e22. PubMed

5. Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Lai M, Horowitz G. A decision support tool to reduce overtesting for ceruloplasmin and improve adherence with clinical guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1561-1562. PubMed

6. Lichtenstein MJ, Pincus T. How useful are combinations of blood tests in “rheumatic panels” in diagnosis of rheumatic diseases? J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3(5):435-442. PubMed

7. Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Bonder A. The incidence and outcomes of ischemic hepatitis: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2015;128(12):1314-1321. PubMed

8. Whitehead MW, Hawkes ND, Hainsworth I, Kingham JG. A prospective study of the causes of notably raised aspartate aminotransferase of liver origin. Gut. 1999;45(1):129-133. PubMed

9. Fontana RJ. Acute liver failure including acetaminophen overdose. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92(4):761-794. PubMed

10. Lee WM, Larson AM, Stravitz RT. AASLD Position Paper: The Management of Acute Liver Failure: Update 2011. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases website. https://www.aasld.org/sites/default/files/guideline_documents/alfenhanced.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed January 26, 2017.

11. Green RM, Flamm S. AGA technical review on the evaluation of liver chemistry tests. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(4):1367-1384. PubMed

12. Aesif SW, Parenti DM, Lesky L, Keiser JF. A cost-effective interdisciplinary approach to microbiologic send-out test use. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139(2):194-198. PubMed

13. Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, Lobach DF. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ. 2005;330(7494):765. PubMed

14. Boberg KM. Prevalence and epidemiology of autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Liver Dis. 2002;6(3):635-647. PubMed

15. Bacon BR, Adams PC, Kowdley KV, Powell LW, Tavill AS; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis and management of hemochromatosis: 2011 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2011;54(1):328-343. PubMed

16. Boonstra K, Beuers U, Ponsioen CY. Epidemiology of primary sclerosing cholangitis and primary biliary cirrhosis: a systematic review. J Hepatol. 2012;56(5):1181-1188. PubMed

1. Johnson RD, O’Connor ML, Kerr RM. Extreme serum elevations of aspartate aminotransferase. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90(8):1244-1245. PubMed

2. Tapper EB, Patwardhan VR, Curry M. Low yield and utilization of confirmatory testing in a cohort of patients with liver disease assessed for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(6):1589-1594. PubMed

3. Tapper EB, Rahni DO, Arnaout R, Lai M. The overuse of serum ceruloplasmin measurement. Am J Med. 2013;126(10):926.e1-e5. PubMed

4. Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Lai M, Horowitz G. Understanding and reducing ceruloplasmin overuse with a decision support intervention for liver disease evaluation. Am J Med. 2016;129(1):115.e17-e22. PubMed

5. Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Lai M, Horowitz G. A decision support tool to reduce overtesting for ceruloplasmin and improve adherence with clinical guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1561-1562. PubMed

6. Lichtenstein MJ, Pincus T. How useful are combinations of blood tests in “rheumatic panels” in diagnosis of rheumatic diseases? J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3(5):435-442. PubMed

7. Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Bonder A. The incidence and outcomes of ischemic hepatitis: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2015;128(12):1314-1321. PubMed

8. Whitehead MW, Hawkes ND, Hainsworth I, Kingham JG. A prospective study of the causes of notably raised aspartate aminotransferase of liver origin. Gut. 1999;45(1):129-133. PubMed

9. Fontana RJ. Acute liver failure including acetaminophen overdose. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92(4):761-794. PubMed

10. Lee WM, Larson AM, Stravitz RT. AASLD Position Paper: The Management of Acute Liver Failure: Update 2011. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases website. https://www.aasld.org/sites/default/files/guideline_documents/alfenhanced.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed January 26, 2017.

11. Green RM, Flamm S. AGA technical review on the evaluation of liver chemistry tests. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(4):1367-1384. PubMed

12. Aesif SW, Parenti DM, Lesky L, Keiser JF. A cost-effective interdisciplinary approach to microbiologic send-out test use. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139(2):194-198. PubMed

13. Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, Lobach DF. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ. 2005;330(7494):765. PubMed

14. Boberg KM. Prevalence and epidemiology of autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Liver Dis. 2002;6(3):635-647. PubMed

15. Bacon BR, Adams PC, Kowdley KV, Powell LW, Tavill AS; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis and management of hemochromatosis: 2011 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2011;54(1):328-343. PubMed

16. Boonstra K, Beuers U, Ponsioen CY. Epidemiology of primary sclerosing cholangitis and primary biliary cirrhosis: a systematic review. J Hepatol. 2012;56(5):1181-1188. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

ESIR and Peripheral Insulin Resistance

A 34‐year‐old man was admitted for evaluation of elevated blood glucose despite extremely high subcutaneous (SQ) insulin requirements. He had a 12‐year history of Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) without episodes of ketoacidosis, managed initially with oral medications (metformin with various sulfonylureas and thiazolidinediones). Three months prior to admission, he was transitioned to SQ insulin and thereafter his requirements escalated rapidly. By the time of his admission, his blood glucose measurements were consistently above 300 mg/dL despite injecting more than 4100 units of insulin daily. His regimen included 300 units of insulin glargine (Lantus) 2 times per day (BID) and 1.75 mL of Humilin U‐500 Insulin (875 units) 4 times per day (QID). Past medical history included metabolic syndrome, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and diabetic neuropathy. Physical exam was remarkable for centripetal obesity (body mass index [BMI] = 38.9 kg/m2), acanthosis nigricans, and necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum (NLD) (Figure 1).

We undertook an investigation to characterize this extreme insulin resistance. After 24 hours without insulin supplementation, and 12 hours of nothing by mouth (NPO), his blood glucose level was 280 mg/dL and his serum insulin was 133.5 IU/mL. We injected 12 units of insulin Aspart and subsequently measured his serum glucose and insulin once more. His blood glucose level had risen to 289 mg/dL and his serum insulin fell to 110.7 IU/mL. We then transitioned the patient to intravenous (IV) insulin. After a series of boluses totaling 400 units, his blood glucose normalized (90 mg/dL) and was maintained in normal range on a rate of 48 units per hour. Over 24 hours, we had infused over 1400 units.

During this time, we also drew several labs. Serum antiinsulin antibodies were undetectable (ARUP Laboratories, Salt Lake City, UT). A full rheumatologic workup was negative for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid factor, Sjgren's syndrome (SS)‐A and SS‐B. Androgen levels were normal, as were 24‐hour urine collections for cortisol and metanephrines. The patient was discharged on a regimen of U‐500 without glargine.

By 5 months after discharge, his blood glucose remained uncontrolled despite increasing doses of U‐500 (with or without metformin and thiazolidinediones). The patient was offered a gastric bypass operation. Now, 4 months postoperative, his blood glucose is controlled, no greater than 90 mg/dL in the morning and 125 mg/dL in the evening. He is off insulin, taking 30 mg pioglitazone (Actos) daily and 500 mg metformin 3 times per day (TID).

Discussion

Extreme insulin resistance (EIR), defined by daily insulin requirements in excess of 200 U, is a rare and frustrating condition.1 Rarer still is extreme subcutaneous insulin resistance (ESIR). A systematic Medline review revealed only 29 reported cases of ESIR, all of which involved patients that maintained IV sensitivity to insulin. Classic diagnostic criteria for ESIR include preserved sensitivity to IV insulin, failure to increase serum insulin with subcutaneous injection, and insulin degrading activity of subcutaneous tissue.2, 3 However, there are, at present, no laboratory tests that can test the final criterion. Indeed, very few of the published reports of ESIR satisfy it, with most studies considering as diagnostic of ESIR the constellation of EIR with failure to raise serum insulin after injection and preserved intravenous insulin sensitivity.

As was evident in the high doses of IV insulin required for blood glucose normalization, our patient also had a proven receptor‐level peripheral resistance. Beyond the common, multifactorial insulin resistance of T2DM, the published reports of patients with extreme peripheral resistance are of 2 types: (A) genetic (eg, Leprechaunism) and (B) acquired autoimmune (Table 1).4 This patient fits neither category. Patients with Type A are very sick, with a syndromic disease that sharply curtails their life expectancy. Patients with Type B acquire antibodies directed against their insulin receptors and are almost invariably elderly African‐American women with severe rheumatological disease, namely SLE. We could not test our patient for an insulin‐receptor antibody secondary to prohibitive cost. This is probably moot, given that his autoimmune workup was negative and, as above, patients with such antibodies are vastly different compared to our patients.

| Class of Insulin Resistance | Mechanism | Incidence | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | Multifactorial | 3% of total population | Many |

| Type A receptor‐level insulin resistance | Congenital receptor defect | 86 cases | U‐500, insulin‐like growth factor‐1 |

| Type B receptor‐level insulin resistance | Antiinsulin receptor antibody | 50 cases | U‐500, immune modulation |

| Subcutaneous insulin resistance | Unknown; SQ protease? | 30 cases | U‐500, intraperitoneal insulin delivery, other |

Based on SQ insulin requirements, our patient had EIR. As his insulin levels failed to rise following an insulin injection, his EIR is thus subcutaneous in nature. However, among patients with this condition his failure to respond to IV insulin is unique. He does not fit criteria for types A or B insulin resistance; his condition is likely also due to an extreme version of the more common, multifactorial peripheral insulin resistance. This is supported by his successful response to the gastric bypass operation.5

The standard treatments for ESIR include: (1) concentrated regular insulin (U‐500) and (2) implantable intraperitoneal delivery; our patient received the former.6 U‐500 use in EIR has been shown to be more cost‐effective.1 Several reports have suggested success with protease inhibitors (aprotinin, nafamostat ointment), plasmapheresis, and intravenous immunoglobulin for extreme SQ resistance. Our case also represents the first treated successfully with a gastric bypass operation.

CONCLUSIONS

EIR can present a significant challenge for both the patient and hospitalist. The approach to this condition should begin with the determination of 24‐hour IV insulin requirement utilizing an insulin drip; serum insulin antibody evaluation; and endocrinology consultation. Our case also highlights a few important points about the broader management of diabetes mellitus. First, there are dermatological manifestations of diabetes that serve as potential markers for disease (namely acanthosis nigricans and NLD). Second, for patients with extreme insulin requirements, an extensive workup should be initiated and the patient should be transitioned to a concentrated regular insulin or intraperitoneal delivery. Third, our experience suggests a role for other measures such as gastric bypass that ought to be studied further.

- ,,.The use of U‐500 in patients with extreme insulin resistance.Diabetes Care.2005;28:1240–1244.

- ,.Impaired absorption of insulin as a cause insulin resistance.Diabetes.1975;24:443.

- ,,.Insulin resistance caused by massive degradation of subcutaneous insulin.Diabetes.1979;28:640–645.

- ,,, et al.Clinical course of genetic diseases of the insulin receptor: a 30‐year prospective.Medicine.2004;83:209–222.

- ,,, et al.Who would have thought it? An operation proves to be the most effective therapy for adult‐onset diabetes mellitus.Ann Surg.1995;222:339–352.

- ,,,,,.Extreme subcutaneous insulin resistance: a misunderstood syndrome.Diabetes Metab.2003;29:539–546.

A 34‐year‐old man was admitted for evaluation of elevated blood glucose despite extremely high subcutaneous (SQ) insulin requirements. He had a 12‐year history of Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) without episodes of ketoacidosis, managed initially with oral medications (metformin with various sulfonylureas and thiazolidinediones). Three months prior to admission, he was transitioned to SQ insulin and thereafter his requirements escalated rapidly. By the time of his admission, his blood glucose measurements were consistently above 300 mg/dL despite injecting more than 4100 units of insulin daily. His regimen included 300 units of insulin glargine (Lantus) 2 times per day (BID) and 1.75 mL of Humilin U‐500 Insulin (875 units) 4 times per day (QID). Past medical history included metabolic syndrome, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and diabetic neuropathy. Physical exam was remarkable for centripetal obesity (body mass index [BMI] = 38.9 kg/m2), acanthosis nigricans, and necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum (NLD) (Figure 1).

We undertook an investigation to characterize this extreme insulin resistance. After 24 hours without insulin supplementation, and 12 hours of nothing by mouth (NPO), his blood glucose level was 280 mg/dL and his serum insulin was 133.5 IU/mL. We injected 12 units of insulin Aspart and subsequently measured his serum glucose and insulin once more. His blood glucose level had risen to 289 mg/dL and his serum insulin fell to 110.7 IU/mL. We then transitioned the patient to intravenous (IV) insulin. After a series of boluses totaling 400 units, his blood glucose normalized (90 mg/dL) and was maintained in normal range on a rate of 48 units per hour. Over 24 hours, we had infused over 1400 units.

During this time, we also drew several labs. Serum antiinsulin antibodies were undetectable (ARUP Laboratories, Salt Lake City, UT). A full rheumatologic workup was negative for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid factor, Sjgren's syndrome (SS)‐A and SS‐B. Androgen levels were normal, as were 24‐hour urine collections for cortisol and metanephrines. The patient was discharged on a regimen of U‐500 without glargine.

By 5 months after discharge, his blood glucose remained uncontrolled despite increasing doses of U‐500 (with or without metformin and thiazolidinediones). The patient was offered a gastric bypass operation. Now, 4 months postoperative, his blood glucose is controlled, no greater than 90 mg/dL in the morning and 125 mg/dL in the evening. He is off insulin, taking 30 mg pioglitazone (Actos) daily and 500 mg metformin 3 times per day (TID).

Discussion

Extreme insulin resistance (EIR), defined by daily insulin requirements in excess of 200 U, is a rare and frustrating condition.1 Rarer still is extreme subcutaneous insulin resistance (ESIR). A systematic Medline review revealed only 29 reported cases of ESIR, all of which involved patients that maintained IV sensitivity to insulin. Classic diagnostic criteria for ESIR include preserved sensitivity to IV insulin, failure to increase serum insulin with subcutaneous injection, and insulin degrading activity of subcutaneous tissue.2, 3 However, there are, at present, no laboratory tests that can test the final criterion. Indeed, very few of the published reports of ESIR satisfy it, with most studies considering as diagnostic of ESIR the constellation of EIR with failure to raise serum insulin after injection and preserved intravenous insulin sensitivity.

As was evident in the high doses of IV insulin required for blood glucose normalization, our patient also had a proven receptor‐level peripheral resistance. Beyond the common, multifactorial insulin resistance of T2DM, the published reports of patients with extreme peripheral resistance are of 2 types: (A) genetic (eg, Leprechaunism) and (B) acquired autoimmune (Table 1).4 This patient fits neither category. Patients with Type A are very sick, with a syndromic disease that sharply curtails their life expectancy. Patients with Type B acquire antibodies directed against their insulin receptors and are almost invariably elderly African‐American women with severe rheumatological disease, namely SLE. We could not test our patient for an insulin‐receptor antibody secondary to prohibitive cost. This is probably moot, given that his autoimmune workup was negative and, as above, patients with such antibodies are vastly different compared to our patients.

| Class of Insulin Resistance | Mechanism | Incidence | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | Multifactorial | 3% of total population | Many |

| Type A receptor‐level insulin resistance | Congenital receptor defect | 86 cases | U‐500, insulin‐like growth factor‐1 |

| Type B receptor‐level insulin resistance | Antiinsulin receptor antibody | 50 cases | U‐500, immune modulation |

| Subcutaneous insulin resistance | Unknown; SQ protease? | 30 cases | U‐500, intraperitoneal insulin delivery, other |

Based on SQ insulin requirements, our patient had EIR. As his insulin levels failed to rise following an insulin injection, his EIR is thus subcutaneous in nature. However, among patients with this condition his failure to respond to IV insulin is unique. He does not fit criteria for types A or B insulin resistance; his condition is likely also due to an extreme version of the more common, multifactorial peripheral insulin resistance. This is supported by his successful response to the gastric bypass operation.5

The standard treatments for ESIR include: (1) concentrated regular insulin (U‐500) and (2) implantable intraperitoneal delivery; our patient received the former.6 U‐500 use in EIR has been shown to be more cost‐effective.1 Several reports have suggested success with protease inhibitors (aprotinin, nafamostat ointment), plasmapheresis, and intravenous immunoglobulin for extreme SQ resistance. Our case also represents the first treated successfully with a gastric bypass operation.

CONCLUSIONS

EIR can present a significant challenge for both the patient and hospitalist. The approach to this condition should begin with the determination of 24‐hour IV insulin requirement utilizing an insulin drip; serum insulin antibody evaluation; and endocrinology consultation. Our case also highlights a few important points about the broader management of diabetes mellitus. First, there are dermatological manifestations of diabetes that serve as potential markers for disease (namely acanthosis nigricans and NLD). Second, for patients with extreme insulin requirements, an extensive workup should be initiated and the patient should be transitioned to a concentrated regular insulin or intraperitoneal delivery. Third, our experience suggests a role for other measures such as gastric bypass that ought to be studied further.

A 34‐year‐old man was admitted for evaluation of elevated blood glucose despite extremely high subcutaneous (SQ) insulin requirements. He had a 12‐year history of Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) without episodes of ketoacidosis, managed initially with oral medications (metformin with various sulfonylureas and thiazolidinediones). Three months prior to admission, he was transitioned to SQ insulin and thereafter his requirements escalated rapidly. By the time of his admission, his blood glucose measurements were consistently above 300 mg/dL despite injecting more than 4100 units of insulin daily. His regimen included 300 units of insulin glargine (Lantus) 2 times per day (BID) and 1.75 mL of Humilin U‐500 Insulin (875 units) 4 times per day (QID). Past medical history included metabolic syndrome, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and diabetic neuropathy. Physical exam was remarkable for centripetal obesity (body mass index [BMI] = 38.9 kg/m2), acanthosis nigricans, and necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum (NLD) (Figure 1).

We undertook an investigation to characterize this extreme insulin resistance. After 24 hours without insulin supplementation, and 12 hours of nothing by mouth (NPO), his blood glucose level was 280 mg/dL and his serum insulin was 133.5 IU/mL. We injected 12 units of insulin Aspart and subsequently measured his serum glucose and insulin once more. His blood glucose level had risen to 289 mg/dL and his serum insulin fell to 110.7 IU/mL. We then transitioned the patient to intravenous (IV) insulin. After a series of boluses totaling 400 units, his blood glucose normalized (90 mg/dL) and was maintained in normal range on a rate of 48 units per hour. Over 24 hours, we had infused over 1400 units.

During this time, we also drew several labs. Serum antiinsulin antibodies were undetectable (ARUP Laboratories, Salt Lake City, UT). A full rheumatologic workup was negative for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid factor, Sjgren's syndrome (SS)‐A and SS‐B. Androgen levels were normal, as were 24‐hour urine collections for cortisol and metanephrines. The patient was discharged on a regimen of U‐500 without glargine.

By 5 months after discharge, his blood glucose remained uncontrolled despite increasing doses of U‐500 (with or without metformin and thiazolidinediones). The patient was offered a gastric bypass operation. Now, 4 months postoperative, his blood glucose is controlled, no greater than 90 mg/dL in the morning and 125 mg/dL in the evening. He is off insulin, taking 30 mg pioglitazone (Actos) daily and 500 mg metformin 3 times per day (TID).

Discussion

Extreme insulin resistance (EIR), defined by daily insulin requirements in excess of 200 U, is a rare and frustrating condition.1 Rarer still is extreme subcutaneous insulin resistance (ESIR). A systematic Medline review revealed only 29 reported cases of ESIR, all of which involved patients that maintained IV sensitivity to insulin. Classic diagnostic criteria for ESIR include preserved sensitivity to IV insulin, failure to increase serum insulin with subcutaneous injection, and insulin degrading activity of subcutaneous tissue.2, 3 However, there are, at present, no laboratory tests that can test the final criterion. Indeed, very few of the published reports of ESIR satisfy it, with most studies considering as diagnostic of ESIR the constellation of EIR with failure to raise serum insulin after injection and preserved intravenous insulin sensitivity.

As was evident in the high doses of IV insulin required for blood glucose normalization, our patient also had a proven receptor‐level peripheral resistance. Beyond the common, multifactorial insulin resistance of T2DM, the published reports of patients with extreme peripheral resistance are of 2 types: (A) genetic (eg, Leprechaunism) and (B) acquired autoimmune (Table 1).4 This patient fits neither category. Patients with Type A are very sick, with a syndromic disease that sharply curtails their life expectancy. Patients with Type B acquire antibodies directed against their insulin receptors and are almost invariably elderly African‐American women with severe rheumatological disease, namely SLE. We could not test our patient for an insulin‐receptor antibody secondary to prohibitive cost. This is probably moot, given that his autoimmune workup was negative and, as above, patients with such antibodies are vastly different compared to our patients.

| Class of Insulin Resistance | Mechanism | Incidence | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | Multifactorial | 3% of total population | Many |

| Type A receptor‐level insulin resistance | Congenital receptor defect | 86 cases | U‐500, insulin‐like growth factor‐1 |

| Type B receptor‐level insulin resistance | Antiinsulin receptor antibody | 50 cases | U‐500, immune modulation |

| Subcutaneous insulin resistance | Unknown; SQ protease? | 30 cases | U‐500, intraperitoneal insulin delivery, other |

Based on SQ insulin requirements, our patient had EIR. As his insulin levels failed to rise following an insulin injection, his EIR is thus subcutaneous in nature. However, among patients with this condition his failure to respond to IV insulin is unique. He does not fit criteria for types A or B insulin resistance; his condition is likely also due to an extreme version of the more common, multifactorial peripheral insulin resistance. This is supported by his successful response to the gastric bypass operation.5

The standard treatments for ESIR include: (1) concentrated regular insulin (U‐500) and (2) implantable intraperitoneal delivery; our patient received the former.6 U‐500 use in EIR has been shown to be more cost‐effective.1 Several reports have suggested success with protease inhibitors (aprotinin, nafamostat ointment), plasmapheresis, and intravenous immunoglobulin for extreme SQ resistance. Our case also represents the first treated successfully with a gastric bypass operation.

CONCLUSIONS

EIR can present a significant challenge for both the patient and hospitalist. The approach to this condition should begin with the determination of 24‐hour IV insulin requirement utilizing an insulin drip; serum insulin antibody evaluation; and endocrinology consultation. Our case also highlights a few important points about the broader management of diabetes mellitus. First, there are dermatological manifestations of diabetes that serve as potential markers for disease (namely acanthosis nigricans and NLD). Second, for patients with extreme insulin requirements, an extensive workup should be initiated and the patient should be transitioned to a concentrated regular insulin or intraperitoneal delivery. Third, our experience suggests a role for other measures such as gastric bypass that ought to be studied further.

- ,,.The use of U‐500 in patients with extreme insulin resistance.Diabetes Care.2005;28:1240–1244.

- ,.Impaired absorption of insulin as a cause insulin resistance.Diabetes.1975;24:443.

- ,,.Insulin resistance caused by massive degradation of subcutaneous insulin.Diabetes.1979;28:640–645.

- ,,, et al.Clinical course of genetic diseases of the insulin receptor: a 30‐year prospective.Medicine.2004;83:209–222.

- ,,, et al.Who would have thought it? An operation proves to be the most effective therapy for adult‐onset diabetes mellitus.Ann Surg.1995;222:339–352.

- ,,,,,.Extreme subcutaneous insulin resistance: a misunderstood syndrome.Diabetes Metab.2003;29:539–546.

- ,,.The use of U‐500 in patients with extreme insulin resistance.Diabetes Care.2005;28:1240–1244.

- ,.Impaired absorption of insulin as a cause insulin resistance.Diabetes.1975;24:443.

- ,,.Insulin resistance caused by massive degradation of subcutaneous insulin.Diabetes.1979;28:640–645.

- ,,, et al.Clinical course of genetic diseases of the insulin receptor: a 30‐year prospective.Medicine.2004;83:209–222.

- ,,, et al.Who would have thought it? An operation proves to be the most effective therapy for adult‐onset diabetes mellitus.Ann Surg.1995;222:339–352.

- ,,,,,.Extreme subcutaneous insulin resistance: a misunderstood syndrome.Diabetes Metab.2003;29:539–546.