User login

Pediatric Conditions Requiring Minimal Intervention or Observation After Interfacility Transfer

Regionalization of pediatric acute care is increasing across the United States, with rates of interfacility transfer for general medical conditions in children similar to those of high-risk conditions in adults.1 The inability for children to receive definitive care (ie, care provided to conclusively manage a patient’s condition without requiring an interfacility transfer) within their local community has implications on public health as well as family function and financial burden.1,2 Previous studies demonstrated that 30% to 80% of interfacility transfers are potentially unnecessary,3-6 as indicated by a high proportion of short lengths of stay after transfer.

To highlight conditions that referring hospitals may prioritize for pediatric capacity building, we aimed to identify the most common medical diagnoses among pediatric transfer patients that did not require advanced evaluation or intervention and that had high rates of discharge within 1 day of interfacility transfer.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional, descriptive study using the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database, which contains administrative data from 48 geographically diverse US children’s hospitals.

We included children <18 years old who were transferred to a participating PHIS hospital in 2019, including emergency department (ED), observation, and inpatient encounters. We identified patients through the source-of-admission code labeled as “transfer.”

For each diagnosis, we determined the number of transfers and frequency of rapid discharge, defined as either discharge from the ED without admission or admission and discharge within 1 day from a general inpatient unit. As discharge times are not reliably available in PHIS, all patients discharged on the day of transfer or the following calendar day were identified as rapid discharge. Medical complexity was determined through applying the Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm (PMCA).8

For descriptive statistics, we calculated means for normally distributed variables, medians for continuous variables with nonnormal distributions, and percentages for binary variables. Comparisons were made using t-tests and chi-square tests.

This study was approved by the Seattle Children’s Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

We identified 286,905 transfers into participating PHIS hospitals in 2019. Of these, 89,519 (31.2%) were excluded (Appendix Table 2), leaving 197,386 (68.6%) transfers. Patients discharged within 1 day were more likely to have public or unknown insurance (65.1% vs 61.5%, P < 0.01), to have no co-occurring chronic conditions (60.2% vs 28.5%, P < 0.01), and to reside within the Northeast (35.0% vs 11.0%, P < 0.01) (Appendix Table 3).

The most common medical diagnoses among these transfers included acute bronchiolitis (4.3% of all interfacility transfers, n = 8,425), chemotherapy (4.0%, n = 7,819), and asthma (3.3%, n = 6,430) (Appendix Table 4); 45.9% of bronchiolitis, 15.0% of chemotherapy, and 67.4% of asthma transfers were rapidly discharged.

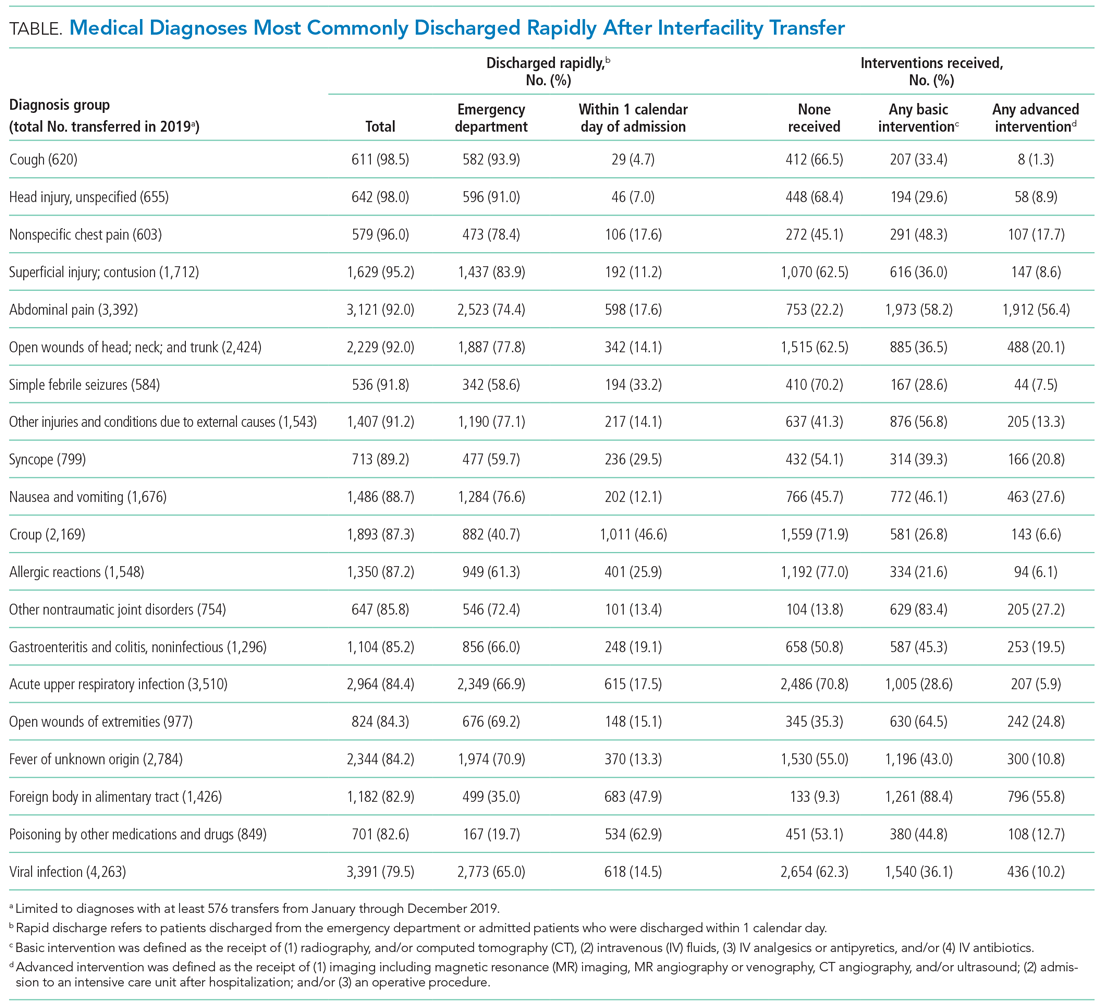

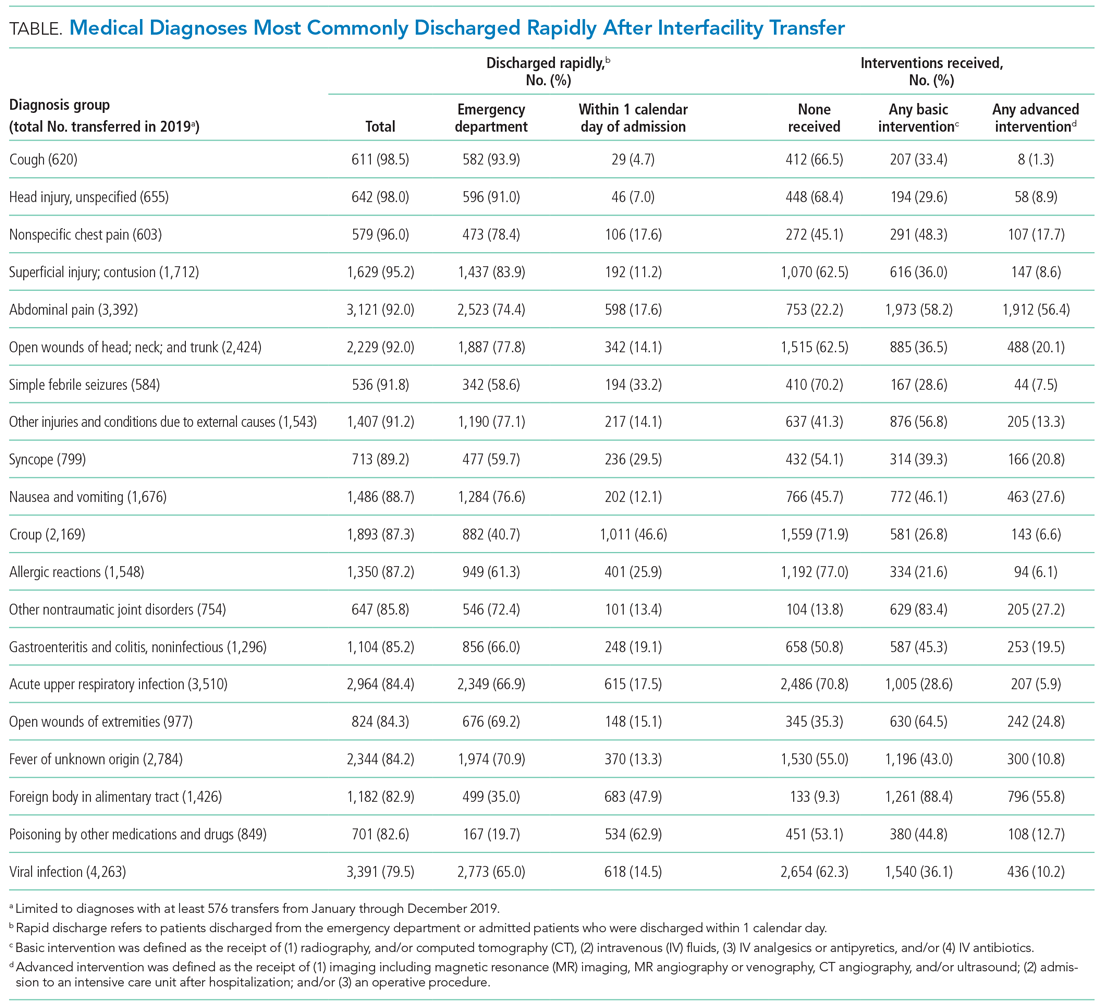

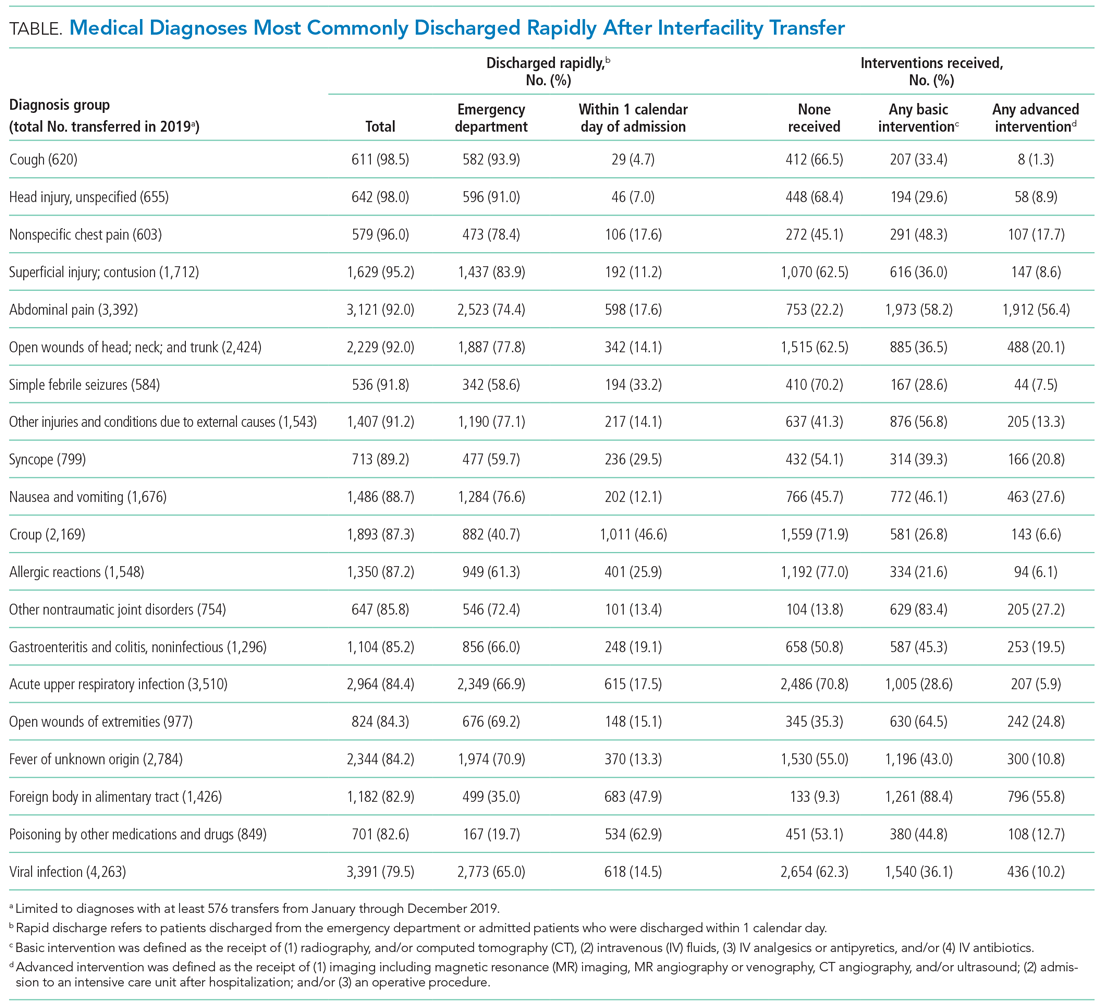

The Table shows the medical conditions among transfers that most frequently experienced rapid discharge (primary surgical diagnoses are presented in Appendix Table 5).

DISCUSSION

We have identified medical conditions that not only had high rates of rapid discharge after transfer, but also received minimal intervention from the accepting institution. Although bronchiolitis and chemotherapy were the most common conditions for which patients were transferred, the range of severity varied widely, with more than 50% of bronchiolitis and 85% of chemotherapy transfers requiring hospitalization for longer than 1 day

Identifying conditions as potential targets to reduce the number of interfacility transfers requires balancing a hospital’s capacity (or lack thereof) for pediatric admissions, perceived risk of decompensation, referring provider discomfort, and parental preference.9-11

The rapid upscale of telehealth may provide a unique opportunity to support the provision of pediatric care within local communities.12,13

Building infrastructure to prevent interfacility transfers may improve healthcare access for children in rural areas proportionately more than children in urban areas. Children in rural communities experience significantly higher rates of interfacility transfers than children in urban areas.14 This increases financial burden and causes additional distress and inconvenience for families.15 With constraints in staffing capacity, equipment, and finances, identifying a subset of medical conditions is a critical initial step to inform the design of targeted interventions to support pediatric healthcare delivery in local communities and avoid costly transfers, although it is not the wholesale solution. Additional utilization of tools such as informed shared decision-making resources and implementation of pediatric-specific protocols likely represent additional necessary steps.

Our study has several limitations. Because we used administrative data, there is a risk of misclassifying diagnoses. We attempted to mitigate this by using a standard ICD-10-based, pediatric-specific grouper.

CONCLUSION

Our exploration of pediatric interfacility transfers that experienced rapid discharge with minimal intervention provides a building block to support the provision of definitive pediatric care in non-pediatric hospitals and represents a step towards addressing limited access to care in general hospitals.

1. França UL, McManus ML. Availability of definitive hospital care for children. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(9):e171096. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1096

2. Mumford V, Baysari MT, Kalinin D, et al. Measuring the financial and productivity burden of paediatric hospitalisation on the wider family network. J Paediatr Child Health. 2018;54(9):987-996. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.13923

3. Richard KR, Glisson KL, Shah N, et al. Predictors of potentially unnecessary transfers to pediatric emergency departments. Hosp Pediatr. 2020;10(5):424-429. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2019-0307

4. Gattu RK, Teshome G, Cai L, Wright C, Lichenstein R. Interhospital pediatric patient transfers-factors influencing rapid disposition after transfer. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(1):26-30. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000000061

5. Li J, Monuteaux MC, Bachur RG. Interfacility transfers of noncritically ill children to academic pediatric emergency departments. Pediatrics. 2012;130(1):83-92. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1819

6. Rosenthal JL, Lieng MK, Marcin JP, Romano PS. Profiling pediatric potentially avoidable transfers using procedure and diagnosis codes. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019 Mar 19;10.1097/PEC.0000000000001777. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001777

7. Pediatric clinical classification system (PECCS) codes. Children’s Hospital Association. December 11, 2020. Accessed June 3, 2021. https://www.childrenshospitals.org/Research-and-Data/Pediatric-Data-and-Trends/2020/Pediatric-Clinical-Classification-System-PECCS

8. Simon TD, Haaland W, Hawley K, Lambka K, Mangione-Smith R. Development and validation of the pediatric medical complexity algorithm (PMCA) version 3.0. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(5):577-580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2018.02.010

9. Rosenthal JL, Okumura MJ, Hernandez L, Li ST, Rehm RS. Interfacility transfers to general pediatric floors: a qualitative study exploring the role of communication. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(7):692-699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.04.003

10. Rosenthal JL, Li ST, Hernandez L, Alvarez M, Rehm RS, Okumura MJ. Familial caregiver and physician perceptions of the family-physician interactions during interfacility transfers. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(6):344-351. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2017-0017

11. Peebles ER, Miller MR, Lynch TP, Tijssen JA. Factors associated with discharge home after transfer to a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34(9):650-655. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001098

12. Labarbera JM, Ellenby MS, Bouressa P, Burrell J, Flori HR, Marcin JP. The impact of telemedicine intensivist support and a pediatric hospitalist program on a community hospital. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19(10):760-766. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2012.0303

13. Haynes SC, Dharmar M, Hill BC, et al. The impact of telemedicine on transfer rates of newborns at rural community hospitals. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20(5):636-641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2020.02.013

14. Michelson KA, Hudgins JD, Lyons TW, Monuteaux MC, Bachur RG, Finkelstein JA. Trends in capability of hospitals to provide definitive acute care for children: 2008 to 2016. Pediatrics. 2020;145(1). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-2203

15. Mohr NM, Harland KK, Shane DM, Miller SL, Torner JC. Potentially avoidable pediatric interfacility transfer is a costly burden for rural families: a cohort study. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(8):885-894. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12972

Regionalization of pediatric acute care is increasing across the United States, with rates of interfacility transfer for general medical conditions in children similar to those of high-risk conditions in adults.1 The inability for children to receive definitive care (ie, care provided to conclusively manage a patient’s condition without requiring an interfacility transfer) within their local community has implications on public health as well as family function and financial burden.1,2 Previous studies demonstrated that 30% to 80% of interfacility transfers are potentially unnecessary,3-6 as indicated by a high proportion of short lengths of stay after transfer.

To highlight conditions that referring hospitals may prioritize for pediatric capacity building, we aimed to identify the most common medical diagnoses among pediatric transfer patients that did not require advanced evaluation or intervention and that had high rates of discharge within 1 day of interfacility transfer.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional, descriptive study using the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database, which contains administrative data from 48 geographically diverse US children’s hospitals.

We included children <18 years old who were transferred to a participating PHIS hospital in 2019, including emergency department (ED), observation, and inpatient encounters. We identified patients through the source-of-admission code labeled as “transfer.”

For each diagnosis, we determined the number of transfers and frequency of rapid discharge, defined as either discharge from the ED without admission or admission and discharge within 1 day from a general inpatient unit. As discharge times are not reliably available in PHIS, all patients discharged on the day of transfer or the following calendar day were identified as rapid discharge. Medical complexity was determined through applying the Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm (PMCA).8

For descriptive statistics, we calculated means for normally distributed variables, medians for continuous variables with nonnormal distributions, and percentages for binary variables. Comparisons were made using t-tests and chi-square tests.

This study was approved by the Seattle Children’s Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

We identified 286,905 transfers into participating PHIS hospitals in 2019. Of these, 89,519 (31.2%) were excluded (Appendix Table 2), leaving 197,386 (68.6%) transfers. Patients discharged within 1 day were more likely to have public or unknown insurance (65.1% vs 61.5%, P < 0.01), to have no co-occurring chronic conditions (60.2% vs 28.5%, P < 0.01), and to reside within the Northeast (35.0% vs 11.0%, P < 0.01) (Appendix Table 3).

The most common medical diagnoses among these transfers included acute bronchiolitis (4.3% of all interfacility transfers, n = 8,425), chemotherapy (4.0%, n = 7,819), and asthma (3.3%, n = 6,430) (Appendix Table 4); 45.9% of bronchiolitis, 15.0% of chemotherapy, and 67.4% of asthma transfers were rapidly discharged.

The Table shows the medical conditions among transfers that most frequently experienced rapid discharge (primary surgical diagnoses are presented in Appendix Table 5).

DISCUSSION

We have identified medical conditions that not only had high rates of rapid discharge after transfer, but also received minimal intervention from the accepting institution. Although bronchiolitis and chemotherapy were the most common conditions for which patients were transferred, the range of severity varied widely, with more than 50% of bronchiolitis and 85% of chemotherapy transfers requiring hospitalization for longer than 1 day

Identifying conditions as potential targets to reduce the number of interfacility transfers requires balancing a hospital’s capacity (or lack thereof) for pediatric admissions, perceived risk of decompensation, referring provider discomfort, and parental preference.9-11

The rapid upscale of telehealth may provide a unique opportunity to support the provision of pediatric care within local communities.12,13

Building infrastructure to prevent interfacility transfers may improve healthcare access for children in rural areas proportionately more than children in urban areas. Children in rural communities experience significantly higher rates of interfacility transfers than children in urban areas.14 This increases financial burden and causes additional distress and inconvenience for families.15 With constraints in staffing capacity, equipment, and finances, identifying a subset of medical conditions is a critical initial step to inform the design of targeted interventions to support pediatric healthcare delivery in local communities and avoid costly transfers, although it is not the wholesale solution. Additional utilization of tools such as informed shared decision-making resources and implementation of pediatric-specific protocols likely represent additional necessary steps.

Our study has several limitations. Because we used administrative data, there is a risk of misclassifying diagnoses. We attempted to mitigate this by using a standard ICD-10-based, pediatric-specific grouper.

CONCLUSION

Our exploration of pediatric interfacility transfers that experienced rapid discharge with minimal intervention provides a building block to support the provision of definitive pediatric care in non-pediatric hospitals and represents a step towards addressing limited access to care in general hospitals.

Regionalization of pediatric acute care is increasing across the United States, with rates of interfacility transfer for general medical conditions in children similar to those of high-risk conditions in adults.1 The inability for children to receive definitive care (ie, care provided to conclusively manage a patient’s condition without requiring an interfacility transfer) within their local community has implications on public health as well as family function and financial burden.1,2 Previous studies demonstrated that 30% to 80% of interfacility transfers are potentially unnecessary,3-6 as indicated by a high proportion of short lengths of stay after transfer.

To highlight conditions that referring hospitals may prioritize for pediatric capacity building, we aimed to identify the most common medical diagnoses among pediatric transfer patients that did not require advanced evaluation or intervention and that had high rates of discharge within 1 day of interfacility transfer.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional, descriptive study using the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database, which contains administrative data from 48 geographically diverse US children’s hospitals.

We included children <18 years old who were transferred to a participating PHIS hospital in 2019, including emergency department (ED), observation, and inpatient encounters. We identified patients through the source-of-admission code labeled as “transfer.”

For each diagnosis, we determined the number of transfers and frequency of rapid discharge, defined as either discharge from the ED without admission or admission and discharge within 1 day from a general inpatient unit. As discharge times are not reliably available in PHIS, all patients discharged on the day of transfer or the following calendar day were identified as rapid discharge. Medical complexity was determined through applying the Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm (PMCA).8

For descriptive statistics, we calculated means for normally distributed variables, medians for continuous variables with nonnormal distributions, and percentages for binary variables. Comparisons were made using t-tests and chi-square tests.

This study was approved by the Seattle Children’s Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

We identified 286,905 transfers into participating PHIS hospitals in 2019. Of these, 89,519 (31.2%) were excluded (Appendix Table 2), leaving 197,386 (68.6%) transfers. Patients discharged within 1 day were more likely to have public or unknown insurance (65.1% vs 61.5%, P < 0.01), to have no co-occurring chronic conditions (60.2% vs 28.5%, P < 0.01), and to reside within the Northeast (35.0% vs 11.0%, P < 0.01) (Appendix Table 3).

The most common medical diagnoses among these transfers included acute bronchiolitis (4.3% of all interfacility transfers, n = 8,425), chemotherapy (4.0%, n = 7,819), and asthma (3.3%, n = 6,430) (Appendix Table 4); 45.9% of bronchiolitis, 15.0% of chemotherapy, and 67.4% of asthma transfers were rapidly discharged.

The Table shows the medical conditions among transfers that most frequently experienced rapid discharge (primary surgical diagnoses are presented in Appendix Table 5).

DISCUSSION

We have identified medical conditions that not only had high rates of rapid discharge after transfer, but also received minimal intervention from the accepting institution. Although bronchiolitis and chemotherapy were the most common conditions for which patients were transferred, the range of severity varied widely, with more than 50% of bronchiolitis and 85% of chemotherapy transfers requiring hospitalization for longer than 1 day

Identifying conditions as potential targets to reduce the number of interfacility transfers requires balancing a hospital’s capacity (or lack thereof) for pediatric admissions, perceived risk of decompensation, referring provider discomfort, and parental preference.9-11

The rapid upscale of telehealth may provide a unique opportunity to support the provision of pediatric care within local communities.12,13

Building infrastructure to prevent interfacility transfers may improve healthcare access for children in rural areas proportionately more than children in urban areas. Children in rural communities experience significantly higher rates of interfacility transfers than children in urban areas.14 This increases financial burden and causes additional distress and inconvenience for families.15 With constraints in staffing capacity, equipment, and finances, identifying a subset of medical conditions is a critical initial step to inform the design of targeted interventions to support pediatric healthcare delivery in local communities and avoid costly transfers, although it is not the wholesale solution. Additional utilization of tools such as informed shared decision-making resources and implementation of pediatric-specific protocols likely represent additional necessary steps.

Our study has several limitations. Because we used administrative data, there is a risk of misclassifying diagnoses. We attempted to mitigate this by using a standard ICD-10-based, pediatric-specific grouper.

CONCLUSION

Our exploration of pediatric interfacility transfers that experienced rapid discharge with minimal intervention provides a building block to support the provision of definitive pediatric care in non-pediatric hospitals and represents a step towards addressing limited access to care in general hospitals.

1. França UL, McManus ML. Availability of definitive hospital care for children. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(9):e171096. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1096

2. Mumford V, Baysari MT, Kalinin D, et al. Measuring the financial and productivity burden of paediatric hospitalisation on the wider family network. J Paediatr Child Health. 2018;54(9):987-996. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.13923

3. Richard KR, Glisson KL, Shah N, et al. Predictors of potentially unnecessary transfers to pediatric emergency departments. Hosp Pediatr. 2020;10(5):424-429. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2019-0307

4. Gattu RK, Teshome G, Cai L, Wright C, Lichenstein R. Interhospital pediatric patient transfers-factors influencing rapid disposition after transfer. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(1):26-30. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000000061

5. Li J, Monuteaux MC, Bachur RG. Interfacility transfers of noncritically ill children to academic pediatric emergency departments. Pediatrics. 2012;130(1):83-92. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1819

6. Rosenthal JL, Lieng MK, Marcin JP, Romano PS. Profiling pediatric potentially avoidable transfers using procedure and diagnosis codes. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019 Mar 19;10.1097/PEC.0000000000001777. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001777

7. Pediatric clinical classification system (PECCS) codes. Children’s Hospital Association. December 11, 2020. Accessed June 3, 2021. https://www.childrenshospitals.org/Research-and-Data/Pediatric-Data-and-Trends/2020/Pediatric-Clinical-Classification-System-PECCS

8. Simon TD, Haaland W, Hawley K, Lambka K, Mangione-Smith R. Development and validation of the pediatric medical complexity algorithm (PMCA) version 3.0. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(5):577-580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2018.02.010

9. Rosenthal JL, Okumura MJ, Hernandez L, Li ST, Rehm RS. Interfacility transfers to general pediatric floors: a qualitative study exploring the role of communication. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(7):692-699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.04.003

10. Rosenthal JL, Li ST, Hernandez L, Alvarez M, Rehm RS, Okumura MJ. Familial caregiver and physician perceptions of the family-physician interactions during interfacility transfers. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(6):344-351. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2017-0017

11. Peebles ER, Miller MR, Lynch TP, Tijssen JA. Factors associated with discharge home after transfer to a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34(9):650-655. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001098

12. Labarbera JM, Ellenby MS, Bouressa P, Burrell J, Flori HR, Marcin JP. The impact of telemedicine intensivist support and a pediatric hospitalist program on a community hospital. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19(10):760-766. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2012.0303

13. Haynes SC, Dharmar M, Hill BC, et al. The impact of telemedicine on transfer rates of newborns at rural community hospitals. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20(5):636-641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2020.02.013

14. Michelson KA, Hudgins JD, Lyons TW, Monuteaux MC, Bachur RG, Finkelstein JA. Trends in capability of hospitals to provide definitive acute care for children: 2008 to 2016. Pediatrics. 2020;145(1). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-2203

15. Mohr NM, Harland KK, Shane DM, Miller SL, Torner JC. Potentially avoidable pediatric interfacility transfer is a costly burden for rural families: a cohort study. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(8):885-894. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12972

1. França UL, McManus ML. Availability of definitive hospital care for children. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(9):e171096. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1096

2. Mumford V, Baysari MT, Kalinin D, et al. Measuring the financial and productivity burden of paediatric hospitalisation on the wider family network. J Paediatr Child Health. 2018;54(9):987-996. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.13923

3. Richard KR, Glisson KL, Shah N, et al. Predictors of potentially unnecessary transfers to pediatric emergency departments. Hosp Pediatr. 2020;10(5):424-429. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2019-0307

4. Gattu RK, Teshome G, Cai L, Wright C, Lichenstein R. Interhospital pediatric patient transfers-factors influencing rapid disposition after transfer. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(1):26-30. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000000061

5. Li J, Monuteaux MC, Bachur RG. Interfacility transfers of noncritically ill children to academic pediatric emergency departments. Pediatrics. 2012;130(1):83-92. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1819

6. Rosenthal JL, Lieng MK, Marcin JP, Romano PS. Profiling pediatric potentially avoidable transfers using procedure and diagnosis codes. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019 Mar 19;10.1097/PEC.0000000000001777. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001777

7. Pediatric clinical classification system (PECCS) codes. Children’s Hospital Association. December 11, 2020. Accessed June 3, 2021. https://www.childrenshospitals.org/Research-and-Data/Pediatric-Data-and-Trends/2020/Pediatric-Clinical-Classification-System-PECCS

8. Simon TD, Haaland W, Hawley K, Lambka K, Mangione-Smith R. Development and validation of the pediatric medical complexity algorithm (PMCA) version 3.0. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(5):577-580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2018.02.010

9. Rosenthal JL, Okumura MJ, Hernandez L, Li ST, Rehm RS. Interfacility transfers to general pediatric floors: a qualitative study exploring the role of communication. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(7):692-699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.04.003

10. Rosenthal JL, Li ST, Hernandez L, Alvarez M, Rehm RS, Okumura MJ. Familial caregiver and physician perceptions of the family-physician interactions during interfacility transfers. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(6):344-351. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2017-0017

11. Peebles ER, Miller MR, Lynch TP, Tijssen JA. Factors associated with discharge home after transfer to a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34(9):650-655. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001098

12. Labarbera JM, Ellenby MS, Bouressa P, Burrell J, Flori HR, Marcin JP. The impact of telemedicine intensivist support and a pediatric hospitalist program on a community hospital. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19(10):760-766. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2012.0303

13. Haynes SC, Dharmar M, Hill BC, et al. The impact of telemedicine on transfer rates of newborns at rural community hospitals. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20(5):636-641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2020.02.013

14. Michelson KA, Hudgins JD, Lyons TW, Monuteaux MC, Bachur RG, Finkelstein JA. Trends in capability of hospitals to provide definitive acute care for children: 2008 to 2016. Pediatrics. 2020;145(1). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-2203

15. Mohr NM, Harland KK, Shane DM, Miller SL, Torner JC. Potentially avoidable pediatric interfacility transfer is a costly burden for rural families: a cohort study. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(8):885-894. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12972

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine